Abstract

Agrochemicals, which are crucial to meet the world food qualitative and quantitative demand, are compounds used to kill pests (insects, fungi, rodents, or unwanted plants). Regrettably, there are some important issues associated with their widespread and extensive use (e.g., contamination, bioaccumulation, and development of pest resistance); thus, a reduced and more controlled use of agrochemicals and thorough detection in food, water, soil, and fields are necessary. In this regard, the development of new functional materials for the efficient application, detection, and removal of agrochemicals is a priority. Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) with exceptional sorptive, recognition capabilities, and catalytical properties have very recently shown their potential in agriculture. This Review emphasizes the recent advances in the use of MOFs in agriculture through three main views: environmental remediation, controlled agrochemical release, and detection of agrochemicals.

Keywords: metal−organic frameworks, agrochemicals, controlled release, selective adsorption and degradation, sensing

1. Current Challenges of Agriculture

Agrochemicals or agrichemicals (primarily fertilizers and pesticides) have become a fundamental part of today’s agricultural systems in order to fulfill the huge requirement of food. Agrochemicals can be classified on the basis of various principles, such as toxicity, target, chemical composition and formula, mode of entry or action, and source. Here, we will classify them according to their mode of action, although their toxicity, target, and origin will also be discussed. Thus, agrochemicals can be divided into pesticides (insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, rodenticides, algaecides, molluscicides, and nematicides), fertilizers (mainly supplying macronutrients: N, P, and K), soil conditioners (improving the soil’s physical and mechanical qualities), liming (Ca and Mg) and acidifying agents, and plant growth regulators (also known as phytohormones).

With a dramatic increase after the second World War,1 the intensive use of agrochemicals has deteriorated the quality of ecosystems (living beings, groundwaters, soils) by impacting human health and, in recent years, leading to the development of pesticide-resistant strains.2−4 Over the period of 2011–2018, pesticide sales were around 360,000 tons per year only in the European Union (EU) with the major groups sold being fungicides, herbicides, and bactericides. This is particularly crucial since, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, agriculture occupies about 38% of Earth’s terrestrial surface.5 High and repeated doses of hazardous agrochemicals are routinely used to protect crops against pests (insects, fungi, unwanted plants, and others) and boost food productivity (e.g., increasing the number of times per year a crop can be grown on the same territory). With a global population projected to rise above 9.7 billion by 2050, food security is of increasing importance. Herbicides are the most widely used pesticides, comprising >40% of total use, while insecticides and fungicides constitute approximately 30% and 20%, respectively. Pesticide/fertilizer pollution patterns are well-established with a major pollution peak taking place a few days or weeks after agrochemical application.6 Ideally, their toxic effect should be limited to both the target area and organisms. However, the lack of specificity of agrochemicals and their widespread use (i.e., in 2018 almost 400,000 tons of pesticides were sold in Europe)7 allow them to leach out of the soil and enter surface water and groundwater; therefore, they are even present in drinking water.8

On the basis of their application methods, between 10% and 75% of the pesticides do not reach their targets,9,10 resulting in frequent contamination of terrestrial and aquatic environments.9−11 The EU Drinking Water Directive sets the general drinking water quality standard for added concentrations of pesticides and their metabolites to be less than 0.5 μg·L–1. Remarkably, most of the studies in this field report that ∼80% of the studied pesticides are found in concentrations much higher than the EU water quality standard (e.g., 3-fold higher concentrations of tebufenpyrad and pendimethalin in the Louros River in Greece,12 21- and 26-fold higher concentrations of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA) in the area of Zurich, Switzerland,13 40-, 25-, and 20-fold higher concentrations of amitrole, diuron, and terbuthylazine in the Arc River in France, respectively,14 and 8-, 12-, 16-, and 25-fold higher concentrations of oxadiazon, pretilachlor, bentazone, and 2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid (MCPA) in the Rhône River in France, respectively,15 among others).

Despite the strict EU regulation, pesticides continue enter the food chain through water and food. Regarding other regions, the problem is magnified. For example, it is predicted that in 2050 the major part of global chemical sales will take place in Asia. During the last two decades, South-East Asian countries have shown a strong industrial growth in agriculture.16 However, the vast majority of these countries lack the capacity to handle chemical management issues and, furthermore, they still need to develop legislation, institutions, and general awareness. Therefore, this should be considered a global environmental problem. In terms of acute toxicity to humans, many agrochemicals manifest their toxicity through biochemical and functional actions in the central and peripheral nervous system. Also, although not always easy to identify, there is evidence that links long-term exposure to some pesticides with chronic illnesses, including dermal, respiratory, liver, and kidney disorders,17 fertility difficulties,18,19 postponed neuropathy,20 and cancer (e.g., sarcoma, lung, brain, gonads, liver, digestive system, and urinary tract).20,21 In this sense, it is likely that the scale and outcome of pesticide-associated chronic effects are underestimated as the symptoms of such poisonings may be incorrectly attributed to other affects. Aside from toxicity to humans, in terms of environmental costs, the unsystematic use of agrochemicals increases pest and disease resistance, diminishes nitrogen fixation and soil biodiversity, and increases the bioaccumulation of pesticides.22 Finally, the loss of livestock to resistant bacterial diseases also represents a considerable waste of water and energy investment as well as capital.

Apart from pesticides, fertilizers are among the major contributors to raise crop yield, and therefore, their use has been exponentially enhanced over the past decades (annually >3 million tons have been imported into the EU since 2015).23 However, as for pesticides, the use of chemical fertilizers is limited by their poor specificity, increasing both the environmental and production costs (between 50% and 70% of total applied nitrogen is lost by volatilization24,25 and 5–10% is lost by leaching).26 Further, inefficiencies in the production of food are further intensified by food waste (i.e., ∼33–50% of global manufactured food spoils as consequence of microbial contamination).27 The actual scenario of the inefficient use of fertilizers and intensive irrigation, biocides, and processed food is stressing ecosystems and leading to significant environmental collateral injuries (e.g., increasing soil erosion and degradation, loss of biodiversity, rising water withdrawals, reducing water quality, eutrophication, disruption of global nutrient cycles, and increasing the energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions).5 All the above suggests that water, food, nature, and animal and human health are inextricably linked to the agri-food systems.

2. Nanotechnology as a Novel Approach in Agrochemical Development

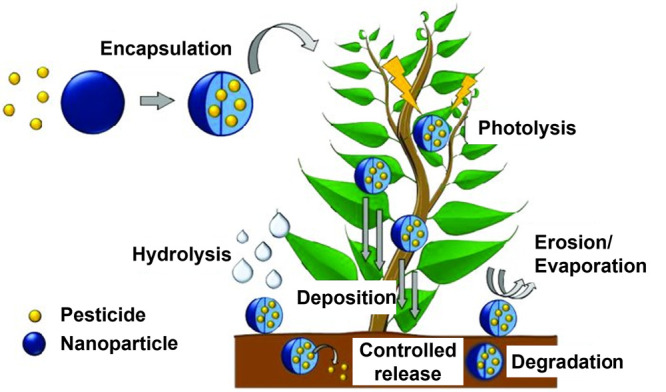

The increase of society’s concern regarding the potential damage of agrochemical application in agricultural production has challenged industry and researchers to search for new efficient and safer methods against insect pests, infections, and unwanted plants or weeds. In this sense, nanotechnology research has recently received an increasing attention in agriculture. With the general aim of developing delivery nanosystems for agrochemicals,28,29 nanopesticides and nanofertilizers have been proposed as a novel class of plant protection and growth products that promise a number of benefits to agriculture, the environment and, finally, human health. One of their key drivers is the important reduction in the quantity of agrochemicals necessary to guarantee crop protection and growth, which may be achieved by different ways, such as (i) improved apparent solubility and stability of photo- and thermolabile agrochemicals or active ingredients (AIs), (ii) controlled release and targeted delivery of AIs, and (iii) enhanced bioavailability and adhesion (Figure 1). Nanocarriers of agrochemicals of different natures have been described, including the known “soft” nanoparticles (NPs) (e.g., polymers, lipid, and nanoemulsions) as well as “hard” nanomaterials, such as silica NPs,30−34 nanoclays,35 TiO2,36 carbon nanotubes,37 or graphene oxides.38 Nanocarriers are mainly applied in plant nutrition with the final objective of an increased efficiency of the actually used fertilizers either by enhancing the administration of elements that are poorly bioavailable (P, Zn) or by reducing losses of mobile nutrients to other natural environments (nitrate). However, long-term instability, subsequent burst agrochemical release, and associated toxicity are some of the major drawbacks that need to be addressed.

Figure 1.

Application of nanotechnology in agriculture. Adapted from ref (39). Copyright 2017 MDPI.

3. Metal–Organic Frameworks as Promising Materials in Agriculture

Among the novel technologies proposed in agriculture, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have gained a significant role in the fields of the elimination of agrochemicals (adsorption and/or photodegradation) and sensing. MOFs are considered to be a remarkable class of highly porous coordination polymers, containing inorganic nodes (e.g., atoms, clusters, or chains) and organic linkers (e.g., carboxylates, nitrogenated, or phosphonates), that assemble into multidimensional periodic lattices.40 MOFs have been proposed for many societal and industrially relevant applications, such as adsorption,41 separation,42 magnetism,43 luminescence,44 conductivity,45 sensing,43 catalysis,46 energy,47 drug delivery,48 etc. In particular, MOFs are promising materials in agriculture due to their interesting properties: (i) versatile hybrid compositions, which allow a huge variety of combinations, (ii) large specific surface areas and pore volumes, related to exceptional sorption capacities, (iii) simply functionalizable cavities, where specific host–guest interactions may occur, (iv) synthesis at large scale (some of them are already commercialized), and (v) an adequate stability profile, so they are stable enough to accomplish their function and, after being degraded, prevent associated toxicity in animals/plants due to their accumulation.

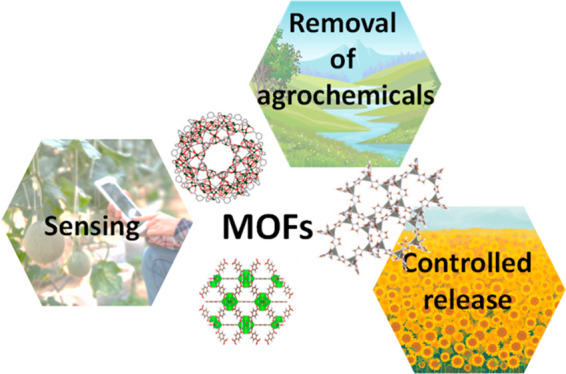

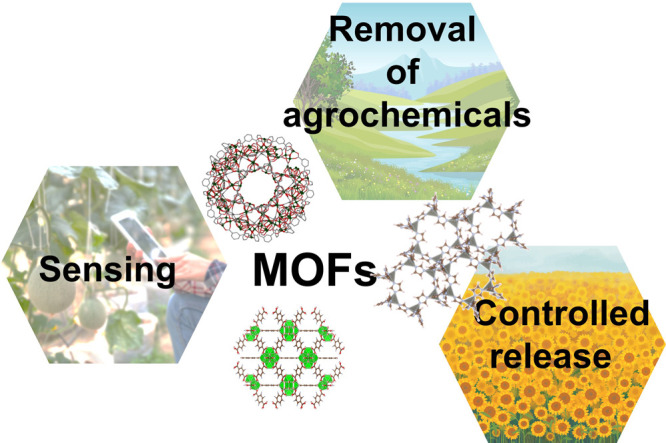

Different strategies have been reported in the use of MOF-type materials in agriculture. In particular, related to agrochemicals, MOFs have been proposed (i) in water remediation through the elimination (adsorption/degradation) of agrochemicals or derived products, (ii) as carriers for the controlled release of agrochemicals, and (iii) as sensors for the determination of these molecules in water or food (Figure 2). While not many reviews have detailed the use of MOFs in the elimination of agrochemicals as contaminants in water49−53 or their potential in the detection and quantification of these potentially toxic molecules,51,54,55 the use of MOFs as agrochemical delivery systems is a very recent research field, initiated in 2015.56 Grouped by their function, this Review will discuss the MOFs and MOF-based composites that have been investigated to date in the agricultural domain. In order to give a broad spectrum of benefits and drawbacks of the use of each material, particular features of each structure and its properties are also included. In the text, the most original, interesting, and promising MOFs in agriculture will be highlighted, although all the reports currently found in the literature are summarized in Tables 1 to 3.

Figure 2.

Proposed application related to agrochemicals and MOFs: environmental remediation, controlled release, and detection/quantification of agrochemicals.

Table 1. Reported MOFs and MOF Composites Related to the Adsorption and/or Degradation of Agrochemicalsa.

| agrochemical | MOF/MOF composite | elimination (% or mg·g–1) | conditions | reusability (cycles) | ref, year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acetamiprid | {SrIICuII6[(S,S)-methox]1.5[(S,S)-Mecysmox]1.50(OH)2(H2O)}·36H2O | 100% | adsorption, 30 s, 100 ppm, aqueous solution | 10 | (67), 2021 |

| thiacloprid | |||||

| alachlor | Cr-MIL-101-C5 (among others) | 186.4 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 24 h, 30 °C, pH = 3–5, 30 ppm, aqueous solutions | (58), 2019 | |

| DUR | 150.2 mg·g–1 | ||||

| tebuthiuron | 95.2 mg·g–1 | ||||

| gramoxone | ca. 60 mg·g–1 | ||||

| ATZ | NU-1000 | 93% | adsorption, <5 min, 10 ppm, RT, aqueous solutions | 3 | (61), 2019 |

| ATZ | M.MIL-100(Fe)@ZnO | ∼78% | photodegradation, 1 h, 5 ppm, pH = 2, +H2O2, 500 W Xe, aqueous solutions | 5 | (68), 2019 |

| ATZ | UiO-67 | 6.78 mg·g–1 | adsorption, pH = 6.9, 25 ppm, 2 and 40 min, aqueous solutions | (69), 2018 | |

| ZIF-8 | 10.96 mg·g–1 | 3 | |||

| bentazon | MOF-235 | 7.15 mg·g–1 | adsorption in aqueous solutions | (70), 2015 | |

| clopyralid | 9.76 mg·g–1 | ||||

| IPU | 10.00 mg·g–1 | ||||

| chipton | UiO-66-NH2@MPCA | 227.3 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 12 h, 10–100 ppm, 30 °C, aqueous solutions | 5 | (59), 2021 |

| chlorantraniliprole | Al-TCPP | 371.91 mg g–1 | adsorption, 7.5 h, 50 ppm, 25 °C, aqueous solution | (71), 2021 | |

| chlorpyrifos | MIL-53(Fe)@AgIO3 | 93–97% (Ad) | adsorption, photodegradation, 1 h, solar light, tap water | (63), 2018 | |

| 70% (Photo) | |||||

| chlorpyrifos | MIL-53(Fe)@CA | 356.34 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 8 h, 20 ppm, 30 °C, aqueous solution | 5 | (72), 2021 |

| chlorpyrifos | MIL-53(Fe)@AgIO3 | 78–90% | catalysis, 1 h, solar light, tap water and distilled water | (63), 2018 | |

| malathion methyl | |||||

| cyhalothrin | ZrO2@HKUST-1 | 99.6% | photodegradation, 6 h, 60 mg·L–1, 14 W, 25 °C, aqueous solutions | 4 | (73), 2019 |

| 2,4-D | MIL-53(Cr) | 556 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 1 h, 100 ppm, RT, aqueous solutions | 3 | (57), 2013 |

| 2,4-D | ZIF-8@ionic liquid | 448 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 12 h, 50–200 ppm, pH = 3.5, aqueous solutions | (74), 2017 | |

| 2,4-DP | [Zn(BDC-NH2)(bpd)] | 91% | adsorption, 90 min, 60 ppm, water solutions | (75), 2018 | |

| 2,4-DP | HRP@H-MOF(Zr) | 100% | catalysis, 15 min, 6 mM, 25 °C, valley water | (65), 2019 | |

| 2,4-DP | UiO-66-NMe3+ | 279 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 2 h, 20 ppm, 25 °C, aqueous solutions | 7 | (76), 2020 |

| 2,4-DP | ILCS/U-10 | 262.45 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 1 h, pH = 2–4, 25–30 °C, aqueous solutions | 4 | (77), 2020 |

| diazinon | MIL-101(Cr) | 260.4 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 3 min, 150 ppm, pH = 7, aqueous solution in continuous flow | 4 | (78), 2018 |

| 92.5% | |||||

| diazinon | MIP-202/chitosan–alginate beads | 17.77 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 40 min, 50 ppm, pH = 7, 22 °C, aqueous solution | 5 | (79), 2021 |

| diazinon | Bp@MIL-125 | 96% | photocatalysis, 30 min, 20 ppm, pH = 7, UV lamp, aqueous solution | (80), 2021 | |

| diazinon | BSA/PCN-222(Fe) | 400 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 3 min, 800 ppm, pH = 7, aqueous solution | 12 | (81), 2021 |

| parathion methyl | 370.4 mg·g–1 | ||||

| dichlorvos | UiO-67 | 571.43 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 200 min, 25 °C, 200 ppm, pH = 4, aqueous solutions | (82), 2019 | |

| metrifonate | 378.78 mg·g–1 | ||||

| 97.8% and 99% | |||||

| dimethoate | Cu-BTC@CA | 282.3–321.9 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 6 h, 30 °C, pH = 7, 20 ppm, aqueous solutions | 5 | (83), 2021 |

| dimethoate | Al-(BDC)0.5(BDC-NH2)0.5 | 344.7 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 8 h, 30 °C, 20 ppm, aqueous solutions | (84), 2021 | |

| DUR | ZIF-8@ionic liquid | 284 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 12 h, 10–20 ppm, pH = 6.6, aqueous solutions | 4 | (74), 2017 |

| ethion | CuBTC@Cotton | 182 m·g–1 | adsorption, 2 h, aqueous solutions | 5 | (85), 2016 |

| 97% | |||||

| ethion | ZIF-8 | 279.3 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 8 h, 25 °C, 50 ppm, aqueous solutions | 4 | (86), 2019 |

| ZIF-67 | 210.8 mg·g–1 | ||||

| fenamiphos | NU-1000 | ca. 6400 mg·g–1 (0.89 mol/mol) | adsorption, 2 h, 108.8 ppm, aqueous solution, dynamic conditions | 3 | (87), 2021 |

| fenitrothion | active-extruded-UiO-66 | 90.2–95.9% | adsorption, 28 ppm, pH = 7, tap and river water | (88), 2021 | |

| fipronil and its metabolites | M-ZIF-8@ZIF-67 | 95% | adsorption, 1 h, 100 ppm, pH = 6, aqueous solutions and cucumber | (89), 2020 | |

| GLU | NU-1000 | 186 mg·g–1 | aqueous solutions | (90), 2020 | |

| GLY | 168 mg·g–1 | ||||

| GLU | UiO-67 | 360 mg·g–1 | Adsorption, 300 min, 0.01 mM, 25 °C, pH = 4, aqueous solutions | (91), 2015 | |

| GLY | NU-1000 | 1516.02 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 20 min, 1.69 ppm, aqueous solutions | (60), 2018 | |

| 100% | |||||

| GLY | UiO-67 | 537 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 300 min, 0.01 mM, 25 °C, pH = 4, aqueous solutions | (91), 2015 | |

| GLY | UiO-67@GO | 483.0 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 300 min, pH = 4, 40 ppm, aqueous solutions | (92), 2017 | |

| GLY | MIL-101(Cr)-NH2 | 64.25 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 12 h, 25 °C, pH = 2–4, 100 ppm, aqueous solutions | (93), 2018 | |

| GLY | Fe3O4@SiO2@UiO-67 | 256.54 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 2 h, RT, 20–70 ppm | 4 | (94), 2018 |

| imidacloprid | Bi2WO6/MIL-88B(Fe)-NH2 | 84% | photocatalysis, 3 h, 10 ppm, pH = 9, Xe lamp | 5 | (95), 2021 |

| IPU | CPO@H-MOF(Zr) | 100% | catalysis, 15 min, 20 μM, 25 °C, valley water | (65), 2019 | |

| mecoprop | UiO-66 | 51 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 6 h, 20–170 ppm, 25 °C, pH = 2–5, aqueous solutions | 3 | (96), 2015 |

| mecoprop | Basolite Z1200 | adsorption, aqueous solutions | (97), 2013 | ||

| NIT | PCN-224 | 95% | photodegradation, 20 min, aqueous solution | (62), 2020 | |

| paraquat | MIL-101(Cr)@α-Fe2O3@TiO2 | 87.5% | catalysis, 45 min, 20 ppm, pH = 7, 25 °C, aqueous solutions | (64), 2018 | |

| paraoxon | UiO-66 | 100% | catalysis, 30 min, RT, 1 mM, pH = 7.8, aqueous solutions | (98), 2018 | |

| parathion methyl | CuBTC@PAN | 90% | adsorption, 2 h, aqueous solutions | (99), 2014 | |

| propiconazole | MIL-101(Cr) | 89.3% | adsorption, 100 min, pH = 3, aqueous solutions | 5 | (100), 2021 |

| prothiofos | ZIF-8 | 366.7 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 8 h, 25 °C, 50 ppm, aqueous solutions | 4 | (86), 2019 |

| ZIF-67 | 261.1 mg·g–1 | ||||

| QPE | QpeH@ZIF-10 | 88% | enzymatic degradation, 14 days, pH = 6.7, watermelon field | 10 | (66), 2021 |

| thiamethoxam | MIL-100(Fe)@Fe-SPC | 95.4% | catalysis, 180 min, 60 ppm, pH = 7.5, 25 °C, +H2O2, us | 5 | (101), 2018 |

| NND | M-MOF | 1.8–3.0 mg·g–1 | adsorption, 1 h, 100 ppm, aqueous mixture of contaminants | (102), 2017 | |

| OP | ZIF-8@M-M | 96% | adsorption, 15 min, 0.2–8 ppm, pH = 2–10, aqueous mixture of contaminants | 5 | (103), 2018 |

The table is sorted according to the studied agrochemical, followed by the MOF-based material name (or chemical formula), elimination capacity (% or mg·g–1), optimal conditions for the elimination (mechanism, time to reach the equilibrium, concentration of the agrochemical, temperature, pH, type of light, and other species involved during the catalytic process), and cycles of reuse. Bp: black phosphorus; bpd: 1,4-bis(4-pyridyl)-2,3-diaza-1,3-butadiene; BSA: bovine serum albumin; CA: cellulose acetate; Fe-SPC: Fe-doped nanospongy porous biocarbon; GO: graphene oxide; H2BDC-NH2: 2-aminoterephthalic acid; HRP: horseradish peroxidase; H3BTC: 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid; ILCS: ionic liquid modified chitosan; M-M: magnetic multiwalled carbon nanotubes; MPCAs: carbon nanotube aerogels; PAN: polyacrylonitrine; QpeH: quizolafop-P-ethyl hydrolase esterase; RT: room temperature; us: ultrasound.

Table 3. Reported MOFs and MOF Composites Related to the Detection of Agrochemicalsa.

| agrochemical | MOF/MOF composite | recovery (%) | applicability | detection limit | ref, year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aldrin | MOF-199/GO fiber | 90.6–104.4 | river water | 2.3–6.9 × 10–3 ppm | (130), 2013 |

| chlordane | 82.7–96.8 | soil | |||

| p,p′-DDE | 72.2–107.7 | water convolvulus | |||

| p,p′-DDD | 82.8–94.3 | longan | |||

| dieldrin | |||||

| endosulfan | |||||

| heptachlor epoxide | |||||

| hexachlorobenzene | |||||

| aldrin | needle trap device packed with the MIL-100(Fe) | air environment | 0.04–0.41 μg·m–3 | (131), 2021 | |

| chlordane | |||||

| dieldrin | |||||

| o,p′-DDT | |||||

| p,p′-DDT | |||||

| hexachlorobenzene | |||||

| 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(4chlorophenyl)ethane | |||||

| ametryn | MIL-101(Cr) | 73.37–107.7 ± 0.10–14.58 | corn | 0.01–0.12 ng·g–1 | (132), 2018 |

| atraton | |||||

| desmetryn | |||||

| dipropetryn | |||||

| prometon | |||||

| prometryn | |||||

| ametryn | MIL-101(Cr) | 91.1–106.7 | soybean | 1.56–2.00 μg·kg–1 | (133), 2015 |

| atraton | |||||

| atz | |||||

| chlorotoluron | |||||

| fenuron | |||||

| monuron | |||||

| terbuthylazine | |||||

| ametryn | MIL-101(Cr) | 89.5–102.7 | peanuts | 0.98–1.9 μg·kg–1 | (134), 2014 |

| atraton | |||||

| ATZ | |||||

| chlortoluron | |||||

| monuron | |||||

| terbumeton | |||||

| terbuthylazine | |||||

| ametryn | Fe3O4@MIL-100(Fe) | 97.6–101.5 | environmental water and vegetable samples | 2.0–5.3 ppb | (135), 2018 |

| ATZ | |||||

| prometon | |||||

| simazine | |||||

| amidosulfuron | UiO-66-NH2 | 75.7–94.2 | spiked soil | 0.19–1.79 ppb | (136), 2017 |

| metsulfuron methyl | 82.2–95.3 | water | |||

| sulfosulfuron | |||||

| thifensulfuron methyl | |||||

| amidosulfuron | UiO-66-NH2 magnetic stir bar | 68.8–98.1 | water and soil | 0.04–0.84 ppb | (137), 2018 |

| metsulfuron methyl | |||||

| sulfosulfuron | |||||

| tribenuron methyl | |||||

| thifensulfuron methyl | |||||

| ATZ | magG@PDA@Zr-MOF | 29–95 | tobacco | 10.78–45.45 ng·g–1 | (138), 2018 |

| bifenthrin | |||||

| cyhalothrin | |||||

| parathion methyl | |||||

| penconazole | |||||

| pirimiphos | |||||

| procymidone | |||||

| trifluralin | |||||

| atraton | Fe3O4@SiO2-GO/MIL-101(Cr) | 83.9–103.5 | rice | 0.010–0.080 μg kg–1 | (139), 2018 |

| ATZ | |||||

| prometon | |||||

| secbumeton, terbuthylazine | |||||

| terbumeton | |||||

| trietazine | |||||

| ATZ | ZIF-8/SiO2@Fe3O4 | 88.0–101.9 | fruit, vegetables, and water | 0.18–0.72 ppb | (140), 2017 |

| prometryn | |||||

| ATZ | [Mg2(APDA)2(H2O)3] | DMF solutions | 150 ppb | (141), 2018 | |

| carbaryl | |||||

| chlorpyrifos | |||||

| 2,4-dichlorophenol | |||||

| 2,6-DN | |||||

| ATZ | [(La0.9Sm0.1)2(DPA)3(H2O)3] | 52.7–135.0 | peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) | 16.0–67.0 μg·kg–1 | (142), 2018 |

| bifenthrin | |||||

| bromuconazole | |||||

| clofentezine | |||||

| fenbuconazole | |||||

| flumetralin | |||||

| pirimicarb | |||||

| procymidone | |||||

| avermectin | Zn-BTC | 78.6–116.1 for industrial wastewater | wastewater | 0.20–1.60 ppb | (143), 2017 |

| carbofuran | 87.5–107.9 for domestic sewage | ||||

| clorpirifos | 97.5–101.1 for tap water | ||||

| fenvalerate | |||||

| pyridaben | |||||

| triadimefon | |||||

| azinphos methyl | [Y1.8Eu0.1Tb0.1(1,4-PDA)3(H2O)1] | aqueous media | 212 ppb | (144), 2019 | |

| azinphos-methyl | [Cd2.5(1,4-PDA)(tz)3] | aqueous media | 16 ppb | (145), 2017 | |

| azinphos-methyl | [Cd3(1,4-PDA)1(tz)3Cl(H2O)4] | apple and tomato | 8 ppb | (146), 2018 | |

| chlorpyrifos | |||||

| parathion | |||||

| bensulfuron methyl | MIL-53-PVDF MMM | 77.20–111.00 | tap, surface, and seawater | 3.75–10.30 × 10–3 ppm | (147), 2019 |

| chlorimuron ethyl nicosulfuron | |||||

| metsulfuron methyl | |||||

| pyrazosulfuron ethyl | |||||

| thifensulfuron methyl | |||||

| bensulfuron methyl | MIL-101(Fe)@PDA@Fe3O4 | 87.1–108.9 | real water samples (lake, river, irrigation, and reservoir water) and vegetables (pak choi, spinach, and celery) | 0.12–0.34 ppb | (148), 2018 |

| chlorimuron ethyl | |||||

| pyrazosulfuron ethyl | |||||

| sulfometuron methyl | |||||

| 6-benzylaminopurin | ZIF-8@SiO2 | 70–120 | oranges | 3.0–59.4 ppb | (149), 2018 |

| indole-3-acetic acid | |||||

| indolepropionic acid | |||||

| 3-indolebutyric acid | |||||

| bifenthrin | UiO-66 | 60.9–117.5 | vegetables | 0.4–2.0 ng·g–1 | (150), 2021 |

| fenvalerate | |||||

| isocarbophos | |||||

| parathion | |||||

| permethrin | |||||

| triazophos | |||||

| bifenthrin | MIL-101(Cr)-based composite | 78.3–103.6 | environmental water and tea samples | 0.008–0.015 ppb | (151), 2018 |

| deltamethrin | |||||

| fenpropathrin | |||||

| permethrin | |||||

| bifenthrin | [(Nd0.9Eu0.1)2(DPA)3(H2O)3] | 78–88 | soursop exotic fruit (Annona muricata) | 0.03–0.05 mg·kg–1 | (152), 2015 |

| teflubenzuron | |||||

| thiacloprid | |||||

| thiamethoxam, thiophanate methyl | |||||

| bromopropylate | [Zn(BDC)x(NH2-BDC)1–x(H2O)2]n | 47–76 | coconut palm | 0.01–0.05 μg·g–1 | (153), 2017 |

| clofentezine | |||||

| coumaphos | |||||

| difenoxuron | |||||

| diniconazole | |||||

| flumetralin | |||||

| fluometuron | |||||

| teflubenzuron | |||||

| butachlor | MIL-101(Zn) | 86.9–119.0 | black, red, and kidney beans | 1.18 μg·kg–1 | (154), 2019 |

| metazachlor | 0.58 μg·kg–1 | ||||

| pretilachlor | 1.78 μg·kg–1 | ||||

| propanil | 0.90 μg·kg–1 | ||||

| butralin | Fe3O4@NH2-MIL-101 | 70.5–119.8 | aqueous solutions | 0.13–0.86 ppb | (155), 2020 |

| chlorothalonil | |||||

| chlorpyrifos | |||||

| deltamethrin | |||||

| pyridaben | |||||

| tebuconazole | |||||

| carbendazim | MXene/CNHs/β-CD-MOFs | 97.77–102.01 | aqueous solution with coexisting substrates and tomato | 1.0 nM | (129), 2020 |

| carbendazim | UiO-67 | 90.82–103.45 | apple, cucumber, and cabbage | 3.0 × 10–3 μM | (156), 2021 |

| carbaryl | MIL-101(Fe)@GO | 98.8–104.7 | fruit and vegetables | 1.2 and 0.5 nM | (157), 2019 |

| carbofuran | |||||

| carbaryl | F1, F2, F3, and F4 | aqueous solution | –, 108, 106, and 30 ppb | (158), 2021 | |

| matrine | |||||

| triadimefon | |||||

| chloramphenicol | MIP/Zr-LMOF | 95–105 | milk and honey | 13 ppb | (159), 2021 |

| chlorfluazuron | ATP@Fe3O4@ZIF-8 | 78.8–114.3 | tea infusions | 0.7–3.2 ppb | (127), 2020 |

| flufenoxuron | |||||

| hexaflumuron | |||||

| lufenuron | |||||

| teflubenzuron | |||||

| triflumuron | |||||

| chlorothalonil | (H3O)[Zn2L1(H2O)] | aqueous solutions | 2.93 ppm | (160), 2019 | |

| 2,6-DN | |||||

| nitrofen | |||||

| trifluralin | |||||

| chlorpyrifos | AChE@Basolite Z1200 | tomato | 3 ng·L–1 | (161), 2021 | |

| chlorpyrifos | Tb-MOF | 82.17–93.6 | tap water, cucumber, cabbage, kiwifruit, and apple | 3.8 nM | (162), 2019 |

| chlorpyrifos | [Ln(tftpa)1.5(2,2′-bpy) (H2O)] | ethanolic solutions, 5 cycles | 0.14 ppb | (163), 2018 | |

| chlorpyrifos | UiO-66-NH2/Glycine/GO | aqueous solution | 0.15 ppb | (164), 2021 | |

| chlorpyrifos | CBZ-BOD@ZIF-8 | aqueous solution | 1.15 ng·mL–1 | (165), 2021 | |

| chlorpyrifos | TMU-4/PES | 88–108 | water and soil samples | 5–8 ppb | (166), 2018 |

| diazinon | |||||

| fenitrothion | |||||

| malathion | |||||

| chlorpyrifos | Cu/CuFe2O4@MIL-88A(Fe) | 88.3–100.4 | water samples (farm water, water of rice field, and river water) and fruit juice and vegetable samples (pomegranate, kiwi, orange, tomato, and cucumber) | 0.2 and 0.5 ng mL–1 | (167), 2021 |

| phosalone | |||||

| chlorfluazuron | Fe3O4@MOF-808 | 84.6–98.3 | tea beverages and juice samples | 0.04–0.15 ppb | (168), 2020 |

| clofentezine diflubenzuron | |||||

| forchlorfenuron | |||||

| hexaflumuron | |||||

| lufenuron | |||||

| penfluoron | |||||

| clethodim | MIL-125(Ti)-NH2@TiO2 | 96.8–103.5 | aqueous solutions | 10 nM | (169), 2015 |

| cyhalothrin | MOFs-MIPs-MSPD | >93 | wheat | 1.8–2.8 ng g–1 | (170), 2019 |

| β-cyfluthrin | |||||

| cyphenothrin | |||||

| 2,4-D | MOF-808 | 77.1–109.3 | mixed juice, orange juice, and tap water | 0.1–0.5 ppb | (171), 2019 |

| 2-DPP | |||||

| 4-CPA | |||||

| dicamba | |||||

| 2,4-D | UiO-66@cotton | 83.3–106.8 | cucumber and tap water | 0.1–0.3 ppb | (172), 2020 |

| 2-DPP | |||||

| 4-CPA | |||||

| dicamba | |||||

| 2,4-D | UiO-67 | 86.12–103.44 | tomato, cucumber, and white gourd | 0.1–0.5 ppb | (173), 2018 |

| 2-DPP | |||||

| 4-CPA | |||||

| dicamba | |||||

| 2,4-D | UiO-66-NH2 | 82.3–102 | tomato, Chinese cabbage, and rape | 0.16–0.37 ng·g–1 | (174), 2017 |

| MCPA | |||||

| MCPB | |||||

| MCPP | |||||

| p,p′-DDD | M-M-ZIF-67 | 75.1–112.7 | tap, river, and agricultural irrigation water samples | 0.07–1.03 ppb | (175), 2018 |

| o,p′- and p,p′-DDE | |||||

| o,p′- and p,p′-DDT | |||||

| α-, β-, γ-, and δ-HCH | |||||

| diazininon | UiO-66 | 85.7–97.8 | tap and river water and tomato, apple, and tomato juice | 2.5 ng·mL–1 | (176), 2021 |

| diazinon | MIL-101@GO-HF-SPME | 88–104 | tomato, cucumber, and agricultural water | 0.21 ppm | (177), 2020 |

| chlorpyrifos | 0.27 ppm | ||||

| diazinon | ZIF-8 | 91.9–99.5 | tap, waste, and river waters and apple, peach, and grape juices | 0.03–0.21 ppb | (178), 2019 |

| fenthion | Zn-based MOFs | ||||

| fenitrothion | |||||

| profenofos | |||||

| phosalone | |||||

| diniconazole | Fe3O4-MWCNT@MOF-199 | 62.80–94.20 | eabbage, spinach, and orange and apple juices | 520–1830 ppb | (179), 2021 |

| fenbuconazole | |||||

| flusilazole | |||||

| hexaconazole | |||||

| penconazole | |||||

| propiconazole | |||||

| tebuconazole | |||||

| 2,6-DN | [Zn2(L)2(TPA)] | recyclable (5 cycles), detection in methanol or chloroform solutions | 0.39 ppm | (180), 2019 | |

| 2,6-DN | [Zn2(bpdc)2(BPyTPE)] | dichloromethane | 0.13–0.8 ppm | (124), 2017 | |

| 2,6-DN | [Cd(tptc)0.5(bpz)(H2O)] | aqueous media | 638 ppb | (181), 2020 | |

| 2,6-DN | Cd-CBCD | aqueous media; recyclability (5 cycles) | 145 ppb | (182), 2019 | |

| 2,6-DN | [Ag(CIP–)] | DMF | 1.7 × 10–7 M | (183), 2019 | |

| 2,6-DN | [Ln3(HDDB)(DDB)(H2O)6] | 98–103.1 | aqueous solution, nectarines, carrots, and grapes | 86 ppb | (184), 2021 |

| (Ln = Eu, Tb, Dy, Gd) | |||||

| 2,6-DN | [Eu2(dtztp)(OH)2(DMF)(H2O)2.5] | lake water, 5 cycles | 5.28 ppm | (185), 2021 | |

| dichlorvos | Fe3O4/MIL-101 | 76.8–94.5 | hair | 0.21–2.28 ppb | (126), 2014 |

| methamidophos | 74.9–92.1 | urine | |||

| dimethoate | |||||

| malathion | |||||

| parathion | |||||

| parathion methyl | |||||

| difenoconazole | M-IRMOF | 74.82–99.52 | vegetable | 0.25 ppb | (186), 2019 |

| epoxiconazole | 0.25 ppb | ||||

| fenbuconazole | 1.0 ppb | ||||

| pyraclostrobin thiabendazole | 0.25 ppb | ||||

| 0.25 ppb | |||||

| diniconazole | UiO-66@polymer | 90.4–97.5 | water | 1.34–14.8 × 10–3 ppm | (187), 2019 |

| flutriafol | 84.0–95.3 | soil | |||

| hexaconazole | |||||

| pyrimethanil | |||||

| tebuconazole | |||||

| diniconazole | MOF-5@GO | 85.6–105.8 | grape, apple, cucumber, celery, cabbage, and tomato | 0.05–1.58 ng·g–1 | (188), 2016 |

| hexaconazole | |||||

| myclobutanil | |||||

| propiconazole | |||||

| triadimefon | |||||

| diniconazole | defective UiO-66 | 82.6–92.2, 82.8–98.2, and 80.2–88.2 for pond, river, and lotus pond waters | environmental water samples | 4–36 ppb | (189), 2021 |

| pyrimethanil | |||||

| tebuconazole | |||||

| dinotefuran | [(CH3)2NH2]2[Cd3(BCP)2] | water | 2.09 ppm | (190), 2021 | |

| α- and β-endosulfan | [(La0.9Eu0.1)2(DPA)3(H2O)3] | 70–107 | lettuce | 0.02 mg·kg–1 | (123), 2010 |

| malathion | |||||

| parathion methyl | |||||

| procymidone | |||||

| pyrimicarb | |||||

| epoxiconazole | Fe3O4@APTES-GO/ZIF-8 | 71.2–110.9 | tap water, honey samples, and mango, grape, and orange juices; recyclability (5 cycles) | 0.014–0.109 ppb | (128), 2020 |

| flusilazole | |||||

| tebuconazole | |||||

| triadimefon | |||||

| fenitrothion | [Cd(BDC-NH2)(H2O)2]n | ethanolic solutions | 1 ppb | (191), 2014 | |

| parathion methyl | |||||

| paraoxon | |||||

| parathion | |||||

| fenitrothion | MOF-5 | aqueous solutions | 5 ppb | (192), 2014 | |

| parathion methyl | |||||

| paraoxon | |||||

| parathion | |||||

| fenitrothion | SPP@Au@MOF-5 | 97.5 | soil | 10–12 M | (193), 2019 |

| paraoxon ethyl | |||||

| GLY | MOF-Calix | aqueous solutions | 0.38 ppm | (194), 2020 | |

| GLY | [Tb(L)2NO3]n (HL) | aqueous solutions | 0.0144 μM | (195), 2021 | |

| glufosinate | MOF-545 | aqueous solutions | 0.0009 ppb | (196), 2021 | |

| GLY | |||||

| imidacloprid | UiO-66-NH2 | 92.39 | fruit samples | 40–60 ppb | (197), 2021 |

| thiamethoxam | 94.37 | ||||

| iprodione | MIL-101-NH2@Fe3O4-COOH | 71.1–99.1 | real water samples | 0.04–0.4 ppb | (198), 2018 |

| myclobutanil | |||||

| prochloraz | |||||

| tebuconazole | |||||

| malathion | BTCA-P-Cu-CP | 91.0–104.4 | vegetable extracts (spinach, celery, lettuce, red capsicum, eggplant, and cherry tomato) | 0.17–0.59 nM | (199), 2019 |

| malathion | Basolite C300 | >92% | water, fruits, and vegetables | 4.0 ppb | (200), 2020 |

| malathion | Pt@UiO-66-NH2 | 93.34–97.80 | aqueous solutions | 4.9 × 10–15 M | (201), 2019 |

| MCPA | HKUST-1 | 57–100 | water, soil, rice, and tomato | 10 × 10–3 ppm | (202), 2018 |

| monocrotophos, trichlorfon | MIL-101(Cr)@MIP | 86.5–91.7 | apple and pear | 0.011 mg·kg–1 | (203), 2017 |

| 0.015 mg·kg–1 | |||||

| molinate | ZIF-67@MgAl2O4 | aqueous solutions | 3 ppm | (204), 2021 | |

| nicosulfuron | Tb-BDOA | aqueous solutions | 1.61 | (205), 2021 | |

| thiamethoxam | 1.04 μM | ||||

| nitrofen | PVP/Glu/CRL@ZIF-8 | 92.15–107.58 | aqueous solutions | 0,14 μM | (206), 2021 |

| p-nitrophenyl phosphate | [Co(OBA)(2,2′-BPY)] | 93.6–131.6 | fruits (watermelon, orange, tomato, and apple) | 352 nM (0.07 mg kg–1) | (207), 2021 |

| bis(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate | real water samples | ||||

| parathion methyl | [Cd(2,2′,4,4′-bptcH2)]n | aqueous solutions | 0.006 ppb | (122), 2010 | |

| parathion methyl | ZnPO-MOFs | 93.0–104.6 | irrigation water | 0.12 μg kg–1 (0.456 nM) | (208), 2018 |

| parathion methyl | Au/Cys-Fe3O4/MIL-101 | juice samples | 5 ppb | (209), 2021 | |

| parathion methyl | Zr-BDC-rGO | 95.3–103.4 | aqueous solutions | 0.5 ng mL–1 | (210), 2021 |

| parathion methyl | Ru(bpy)32+-ZIF-90 | 93.3–103.6 | aqueous solutions | 0.037 ng mL–1 | (211), 2021 |

| paraquat | [Zn2(cptpy)(BTC)(H2O)]n | aqueous solutions | 9.73 × 10–6 M | (212), 2019 | |

| parathion methyl | Zr-LMOF | 78–107 | cowpea and lettuce | 0.115 μg·kg–1 | (125), 2019 |

| parathion | |||||

| parathion | [Cd(BDC-NH2)(H2O)2]n | rice | 0.1 ppb | (213), 2015 | |

| quinalphos | CD@UiO-66-NH2 | 98–105 | tomato and rice | 0.3 nM | (214), 2021 |

| NIT | PCN-224 | 97.76–104.02 | paddy water | 0.03 × 10–3 ppb | (62), 2020 |

| 88.1–100.30 | soil | ||||

| NIT | Rho B@1 | 95.2–102.0 | river water | 0.27 μg·kg–1 | (215), 2020 |

| Rho 6G@1 | 93.4–103.5 | 0.86 μg·kg–1 | |||

| thiabendazole | Tb3+@UiO-66-(COOH)2 | 98.41–104.48 | orange and aqueous solutions | 0.271 μM | (216), 2021 |

| thiabendazole | Ag-Au-IP6-MIL-101(Fe) | 84.4–112.8 | juice | 50 ppb | (217), 2019 |

The table is organized according to the agrochemical studied, followed by the MOF-based material name (or chemical formula), recovery (%), applicability, and detection limit. 2,2′-BPY: 2,2′-bipyridyl; 2,2′,4,4′-bptcH2: 2,2′,4,4′-biphenyltetracarboxylic acid; AChE: acetylcholinesterase; APTES: (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane; ATP: attapulgite; BPyTPE: (E)-1,2-diphenyl-1,2-bis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene; bpz: 2-(1H-pyrazol-3-yl)pyridine; CD: carbon dots; CNHs: carbon nanohorns; CP: coordination polymer; CRL: Candida rugosa lipase; DMF: N,N′-dimethylformamide; GO: graphene oxide; H2BDC: bezene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid; H2BDC-NH2: 2-aminoterephthalic acid; H2bpdc: biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid; H2DPA: pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid; H3BTC: 1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid; H4BTCA: benzene-1,2,4,5 tetracarboxylic acid; HCIP: 4-(4-carboxylphenyl)-2,6-di(4-imidazol-1-yl)phenyl pyridine; H3CBCD: 4,4′-(9-(4′-carboxy-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)-9H-carbazole-3,6-diyl)dibenzoic acid; H4dtztp: 2,5-bis(2H-tetrazol-5-yl) terephthalic acid; Hcptpy: 4-(4-carboxyphenyl)-2,2′:4′,4″-terpyridine; H5DDB: 3,5-di(2′,4′-dicarboxylphenyl) benzoic acid; HL: 3.5-bis(triazol-1-yl) benzoic acid; H2tftpa: tetrafluoroterephthalic acid; H4tptc: p-terphenyl-2,2′,5″,5‴-tetracarboxylate acid; H2APDA: 4,4′-(4-aminopyridine-3,5-diyl)dibenzoic acid; H4BCP: 5-(2,6-bis(4-carboxyphenyl)pyridin-4-yl)-isophthalic acid; HF: hollow fiber; IP6: inositol hexaphosphate; L1H5: 2,5-(6-(4-carboxyphenylamino)-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diyldiimino)diterephthalic acid; L: 4-(tetrazol-5-yl)phenyl-4,2′:6′,4″-terpyridine; polymer: poly(N-vinylcarbazole-co-divinylbenzene); magG: magnetic graphene; MIP: molecularly imprinted polymer; MMM: mixed-matrix membranes; MSPD: matrix solid-phase dispersion; OBA: 4,4′-oxybis(benzoic acid); PBS: phosphate buffer saline; PDA: polydopamine; 1,4-PDA: 1,4-phenylenediacetate; PES: poly(ether sulfone); PVDF: poly(vinylidene fluoride); Rho: rhodamine; SPME: solid-phase microextraction; SPP: surface plasmon polariton; TPA: terephthalic acid; tz: 1,2,4-triazolate.

4. MOFs in Environmental Remediation: Agrochemicals Elimination

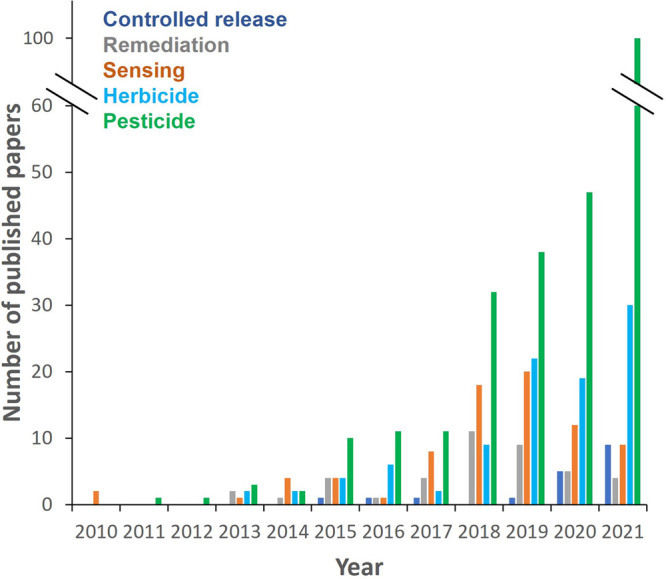

In recent years, MOFs have exponentially been investigated for the removal (mainly adsorption or degradation processes) of different contaminants from water. Originally, this field was focused on the removal of organic dyes, although recently, agrochemicals have also been included as target contaminants due to their increasing presence in natural waters and their severe toxicity to living beings. Thus, an increase in the number of reports dealing with the elimination of different agrochemicals using MOFs has been reported (Figure 3), including (i) herbicides: alachlor, atrazine (ATZ), bentazon, chipton, clopyralid, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), diuron (DUR), glufosinate (GLU), glyphosate (GLY), gramoxone, isoproturon (IPU), mecoprop, paraquat, quizalofop-P-ethyl (QPE), and tebuthiuron; (ii) fungicides: propiconazole and thifluzamide (THI); (iii) insecticides: chlorantraniliprole, chlorpyrifos, cyhalothrin, diazinon, dichlorvos, dimethoate, ethion, fenamiphos, fenitrothion, malathion methyl, metrifonate, nitenpyram (NIT), paraoxon, parathion methyl, prothiofos, thiamethoxam, several neonicotinoids (NND, acetamiprid, clothianidin, dinotefuran, imidacloprid, NIT, thiacloprid, and thiamethoxam), and organophosphorus pesticides (OP, diazinon, ethoprop, isazofos, methidathion, phosalone, profenofos, sulfotep, and triazophos). Table 1 summarizes the reported studies regarding agrochemical removal using MOFs and MOF-based composites with a summary of the conditions and results of each study (on the basis of the reported data presented by the authors).

Figure 3.

Number of published papers having keywords MOF and agriculture in their titles and abstracts, separated by areas (i.e., controlled release, remediation, and sensing) and important related words (herbicide and pesticide). Retrieved from the Web of Science on March 10, 2022.

4.1. Adsorption Processes

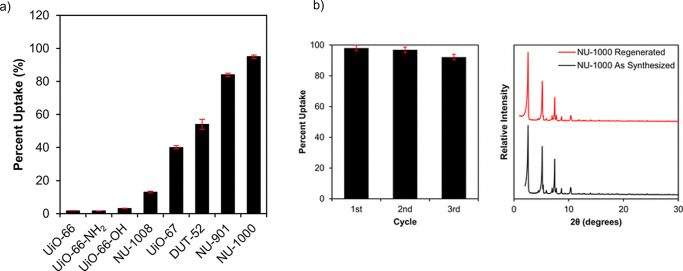

Regarding the adsorption of herbicides, the first study was published by Jung et al. in 2013 for the removal of 2,4-D using the MIL-53(Cr) material ([Cr(OH)(BDC)]; H2BDC: benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid, pore size of ∼8 Å).57 MIL-53(Cr) exhibited an efficient and fast adsorption (556 mg·g–1 in 1 h) with an adsorption capacity much higher than that of activated carbon (286 mg·g–1) or zeolite (256 mg·g–1). Importantly, the adsorption of 2,4-D at a very low concentration is 5-fold greater that of activated carbon at a plateau concentration, demonstrating the utility of MIL-53(Cr) in commercial uses for consumed water with low 2,4-D levels. Finally, the recyclability of MIL-53(Cr), after washing the MOF with a mixture of water/ethanol, was also noticeable after 3 cycles, suggesting the potential application of this MOF on the herbicide’s removal. In a more recent work, a series of furan-thiophene derived from Cr-MOF MIL-101(Cr) ([Cr3(O)X-(BDC)3(H2O)2], X = OH or F; Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area (SBET) ∼ 4100 m2 g–1; pore volume (Vp) = 2.02 cm3 g–1; pore size of 11.7 and 16 Å) was achieved via visible-light-mediated C–C bond-forming catalysis within photosensitizing porous materials.58 The process of trapping the guest molecule was accomplished under metal-free and very mild conditions, leading to novel functionalized MOFs with more π–π stacking, H bonding properties, and outstanding adsorption capacity to eliminate herbicides from the aqueous solutions. The synthesized MOFs removed up to 96.9% of the tested herbicides from the aqueous solutions even at initially very low herbicide concentrations (30 ppm). Particularly, the Br derivative MIL-101(Cr)-C5 inhibited the maximum adsorbed capacities for DUR, alachlor, and tebuthiuron with adsorption capacities of 186.4, 150.2, and 95.2 mg·g–1, respectively. Very recently, a composite based on Zr-MOF UiO-66-NH2 ([Zr6O4(OH)4(BDC-NH2)6]·nH2O; SBET ∼ 950 m2 g–1; pore size of ∼11 and 8 Å; H2BDC-NH2: 2-aminoterephthalic acid) was described for the removal of herbicides in water.59 UiO-66-NH2 was loaded on the carbon nanotube aerogels (MPCAs) by the in situ nucleation and growth of the UiO-66-NH2 NPs onto the carbon nanotubes (UiO-66-NH2@MPCA). The study on the adsorption of chipton and alachlor demonstrated that the adsorption capacity of UiO-66-NH2@MPCA was improved with respect the single MOF NPs, which is indicative of a synergistic effect between the MOF and MPCA (i.e., the chipton adsorption capacity is improved from 98.4 to 227.3 mg·g–1 for UiO-66-NH2 and UiO-66-NH2@MPCA, respectively). Further, rice was used to assess the biosecurity of the composite. Remarkably, UiO-66-NH2@MPCA could reduce the accumulation of Zr4+ in the roots and leaves of rice in comparison with the UiO-66-NH2 NPs, demonstrating that MPCA can diminish the potential environmental risk of the MOF materials. Lastly, the authors demonstrated the reusability of the composite up to 5 times without decreasing its adsorption capacity. Finally, we want to highlight two reports utilizing the water stable Zr-based MOF NU-1000 ([Zr6(μ3-O)4(μ3–OH)4(−OH)4(−OH2)4(PyTBA)2]; PyTBA: 4,4′,4″,4‴-(pyrene-1,3,6,8-tetrayl)tetrabenzoate; SBET ∼ 2100 m2·g–1; pore size of ∼12 and 30 Å). In the first study, reported by Pankajakshan et al.,60 NU-1000 was described for the efficient elimination of GLY from aqueous media. NU-1000 comprises [Zr6(μ3-O)4(μ3-OH)4(H2O)4(OH)4] as secondary building units, acting as Lewis acid nodes that can react with the Lewis base phosphate group of GLY. Theoretical calculations demonstrated that the interaction energy of GLY with the NU-1000 nodes was −37.63 KJ·mol–1. NU-1000 was synthesized in different particle size scales (100–2000 nm), reducing the equilibrium times with smaller MOF sizes and achieving a total GLY loading of 1516.02 mg·g–1 (or 8.97 mg·g–1) in only 20 min. In the second work, the same authors thoroughly investigated the mechanism governing ATZ adsorption on Zr6-based MOFs (UiO-66-X, where X = H, OH, NH2; DUT-52; UiO-67; NU-901; NU-1000; and NU-1008) by investigating the impact of MOF used linkers and topology on ATZ uptake capacity and kinetics.61 Among all the tested Zr-MOFs, it was found that the mesopores of NU-1000 facilitate the rapid ATZ uptake, saturating in less than 5 min. Excluding the pyrene-based linker, NU-1008 ([Zr6(μ-O)4(μ-OH)4(HCOO)(H2O)3(OH)3(TCPB)2]; TCPB: 1,2,4,5-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)benzene; SBET ∼ 1400 m2·g–1; pore size of ∼14 and 30 Å) removed <20% of the exposed ATZ. The pyrene-based linker seems to offer enough sites for π–π interactions with ATZ as revealed by the near 100% uptake (Figure 4). These results indicate that the ATZ uptake in NU-1000 stems from the existence of a pyrene core in the linker of the MOF, which confirms that the π–π stacking is the main force of the ATZ adsorption. Finally, the cyclability of the MOF was demonstrated through 3 adsorption–desorption cycles.

Figure 4.

(a) ATZ uptake as a percentage of the total amount of ATZ exposed to Zr-MOFs for 24 h and (b) through 3 cycles of ATZ adsorption and regeneration with acetone using NU-1000 while maintaining its crystallinity. Reprinted from ref (61). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

4.2. Catalytic Processes

The number of studies related to the catalytic degradation of agrochemicals using MOFs or MOF composites are very limited. The literature mainly focuses on the use of MOF composites with only one work based on a simple MOF. This study describes the bifunctional nanoscale porphyrinic MOF PCN-224 (or [Zr6(TCPP)1.5]; H2TCPP: tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyric; SBET = 2600 m2·g–1; Vp = 0.95 cm3·g–1; pore size = 1.9 nm) as both the sensor for the recognition of trace NIT and the photocatalyst to enable the pesticide degradation.62 The intense fluorescence of the probe was quenched by NIT, leading to a sensing range from 0.05 to 10.0 μg·mL–1. The potentiality of PCN-224 in the degradation of NIT was further identified. The photodegradative effectiveness was up to 95% after only 20 min of laser irradiation, whereas no significant NIT degradation was detected under darkness, regardless of the PCN-224 presence. Therefore, this material could be established as an all-in-one nanoplatform for pesticide sensing, detection, and posterior photodegradation in agricultural farmland and other environments. Among other MOF-based composites, metallic NP composites are the most employed. The MIL-53(Fe)@AgIO3 composite was successfully applied in the decomposition of two organophosphate pesticides (OPs; malathion methyl and chlorpyrifos) under sunlight irradiation.63 After 1 h of solar light irradiation, 78–90% of both pesticides was individually degraded in tap and distilled water. In binary mixtures (both composites), 70% of mineralization is achieved after 3 h. Another example of metallic NPs@MOF composites is magnetic α-Fe2O3@MIL-101(Cr)@TiO2 for the degradation of paraquat herbicide from aqueous solution.64 A maximum photocatalytic degradation was achieved at optimal conditions (see Table 1; 87.5% after 45 min), demonstrating the utility of these systems in the photocatalytic degradation of agrochemicals in water.

MOFs have also been used as support for the stabilization of enzymes able to degrade agrochemicals in wastewater and soil. Gao et al. described the preparation of a hierarchically porous MOF (H-MOF(Zr)) as support of the chloroperoxidase (CPO) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) enzymes, leading to the CPO/HRP@H-MOF(Zr) composite.63 CPO@H-MOF(Zr) and HRP@H-MOF(Zr) composites were applied in the treatment of wastewater containing IPU and 2,4-D, achieving a complete and very fast (15 min) degradation. Finally, we want to highlight the fabrication of purified esterase embedded in zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) for the degradation of pesticides.66 Particularly, in this work, aryloxyphenoxypropionate herbicide-hydrolyzing enzyme, QpeH, was embedded into ZIF-10 ([Zn(Im)2]; Im: imidazonate) and ZIF-8 ([Zn(Hmim)2]; Hmim: 2-methylimidazole; SBET ∼ 1260 m2 g–1, Vp ∼ 0.6 cm3 g–1, pore size of ∼3.4 and 11.4 Å) and tested in the degradation of quizalofop-P-ethyl in a watermelon field. Remarkably, the QpeH@ZIF-10 composite showed a slightly improved degradation efficiency compared to QpeH@ZIF-8 (88% vs 84%). Unfortunately, no ZIF degradation studies were performed in this research in an attempt to rationalize the different behaviors of both ZIF composites and their potential application in real water treatments. It should be noted that the QpeH@ZIF composites were demonstrated to affect the recovery of the bacterial community in soil.

5. MOFs as Agrochemical Delivery Agents

The recent enthusiasm around the use of MOFs as agrochemical delivery agents is highlighted in Figure 3 with a significant increase in the number of papers published on the topic in the last two years. All the studies reported so far on the controlled release of agrochemicals from MOFs are summarized in Table 2, again sorted by the different types of released agrochemical: (i) herbicides, cis-1,3-dichloropropene (1,3-DCPP) and ortho-disulfides; (ii) fungicides, diniconazole, prochloraz, tebuconazole, and zoxystrobin; (iii) insecticides, chlorantraniliprole, λ-cyhalothrin, dinotefuran, imidacloprid, and thiamethoxam; (iv) fertilizers: urea; (v) plant grow regulators: gibberellin. The first MOF described as a delivery agent of agrochemicals was OPA-MOF (OPA: oxalate–phosphate–amine). In 2015, Anstoetz et al. described the use of an OPA-MOF as a microbially induced slow-release N and P fertilizer.56 In this research, the capacity of the urea-templated OPA-MOF as a new fertilizer with a slow release was investigated and compared with a standard P (triple superphosphate) and N (urea) fertilizer (ferralsol). The authors hypothesize that the OPA-MOF is a gradual-release fertilizer for crops grown on acidic soils, where microbial consumption of the oxalate linker gives rise to the degradation of the framework structure, thereby releasing Fe phosphate. While in the OPA-MOF treatment the hydrolysis of urea was fast, the conversion of the ammonium to nitrate was significantly diminished in comparison with the urea treatment (ferralsol). However, P uptake and yield in OPA-MOF was considerably lower than in conventionally fertilized plants. OPA-MOF was proven to have potential as an enhanced efficiency N fertilizer but not in P bioavailability. A year later, two novel OPA-MOFs were hydrothermally synthesized and fully characterized to be used again as slow-release fertilizers.104 The framework backbone is robust and based on FeO6 units with bidentate oxalate bridges joining adjacent Fe centers. PO4 units have corner-sharing for all of their oxygens with the FeO6 units. The authors studied the release of oxalate, setting it high enough to permit oxalate concentrations in the soil solution to achieve 1 mg·L–1 but also low enough to avoid fast and purely chemically driven compound degradation. The results show that, from the two synthesized materials, OPA-MOF-I has a slow solubility with an oxalate concentration of ca. 5 mg·L–1 at high loading and seems to be compatible with trials as a fertilizer in future works.

Table 2. Previously Reported MOF-Based Materials Associated with the Controlled Release of Agrochemicalsa.

| agrochemical | MOF/MOF composite | loading (wt % or mmol·g–1) | release conditions | activity studies | ref, year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| azoxystrobin | MIL-100(Fe) | 16.2 wt % | 80% (pH = 5.0), 85% (pH = 7.2), 86% (pH = 8.5) with PBS, ethanol, and Tween-80 emulsifier | fungicidal activity against (Fusarium graminearum and Phytophthora infestans) 5 and 15 ppm, 56% and 62% of inhibition in 7 days, nutritional function of Fe | (109), 2020 |

| azoxystrobin; diniconazole | MIL-101(Al)-NH2 | 6.71%; 29.72% | 90% in 46 and 136 h | germicidal efficacy against rice sheath blight (Rhizoctonia solani), EC50 = 0.065 mg·mL–1 | (110), 2021 |

| λ-cyhalothrin | UiO-66 | 87.71 wt % | 70% in 12 h in DMF or 60% DMF aqueous solution | insecticide activity assay (Musca domestica) KT50 = 3.64, 5.12, and 6.91 min after being treated 1, 15, and 30 days; bioactivity (Aphis craccivora) LC50 = 3.20, 0.70, and 0.36 ppm at 24, 48, and 72 h | (111), 2020 |

| 1,3-DCPP | MOF-1201; MOF-1203 | 1.4 mmol·g–1; 13 wt % | 80% in 100 000 min·g–1 under air flow 1.0 cm3·min–1 | (105), 2017 | |

| chlorantraniliprole | MIL-101(Fe)@silica | 23% | dialysis method, water, sink conditions | photostability improvement (16.5 times more stable), insecticidal activity against Plutella xylostella (LC50 = 0.389 mg·L–1) | (112), 2021 |

| diniconazole | PDA@NH2-Fe-MIL-101 | 28.1 wt % | PBS/ethanol/Tween-80 emulsifier | fungicidal activity against Fusarium graminearum 1 and 5 ppm for 4 days of inhibition of 44% and 86% | (113), 2020 |

| dinotefuran | MIL-101(Fe)@CMCS | 24.5% | 83.1% aqueous solution stimulated by citric acid in ca. 18 h | photostable (70%) after 48 h of irradiation, insecticidal activity in soil | (114), 2020 |

| dinotefuran, Zn2+ | PFAC | 13.60% | photothermal triggered release (49% at 40 °C), pH response release (pH = 4.0 and 7.0 is 52.63% and 31.87%) | stem length (39.2 vs 33.9 cm) and root length (19.7 vs 13.5 cm) of the corn were clearly improved after 25 days of cultivation | (115), 2021 |

| gibberellin | CLT6@PCN-Q | 0.78 mmol g–1 | release under stimuli (pH, temperature, and competitive agent) | germination of Chinese cabbages and monocotyledonous wheat | (116), 2021 |

| imidacloprid | Fe3O4@PDA@UiO-66 | 15.87% | dialysis method in water (50% in 48 h) | insecticidal activity against Aphis craccivora Koch (LC50 = 2.15 mg·L–1, comparable to the commercialized formulation) | (117), 2021 |

| NH4+ | MOF(Fe)@NaAlg(2:10) | 1.63 mmol·g–1 | release in water (80%) and soil (69%) in 28 days | water retention of soil | (118), 2020 |

| ortho-disulfides (DiS-NH2 and DiS-O-acetyl) | ZIF-8 | 42.8 and 16.71 wt % | ca. 85% in 2 h of PBS (pH = 5.5) | IC50 = 5.413 and 3.892 μM, phytotoxicity bioassay against Echinochloa crusgalli, Amaranthus viridis, and Lollium rigidum | (119), 2021 |

| oxalate; urea | OPA-MOF | 3.1% of N; 12.5% of P, 14.5% of oxalate | soil incubation and crop growth (wheat) | (56), 2015 | |

| oxalate; urea | OPA-MOF I and II | 3.2% and 5.8% of N; 11.3% and 15.6% of P | (104), 2016 | ||

| prochloraz | PD@ZIF-8 | pH and light response, release in dark (13.7%) vs light (63.4%) | cytotoxicity under light EC50 = 0.122 μg·mL–1, fungal activity (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum), updated in plants (oilseed rape) | (120), 2021 | |

| tebuconazole | MIL-101(Fe)-TA | 24.1 wt % | stimuli response (pH, sunlight, H2O2, GSH, PO43–, and EDTA) | cytotoxicity (HLF-1), safety (wheat seedlings), and fungicidal activity (Rhizoctonia solani and Fusarium graminearum) | (107), 2021 |

| tebuconazole | PCN-224@P@C | 30 wt % | 174 h in PBS solution (pH = 5) 17.2%, stimuli response to pectinase in PBS (pH = 5) 86.9% in 174 h | fungicidal activity (Xanthomonas campestris pv campestris, Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato, and Alternaria alternate) and safety (Chinese cabbage) | (106), 2019 |

| thiamethoxam | UiO-66-NH2/SL | 33.56 wt % | PBS solution at 37 °C (ca. 80% in 60 h), soil column (76.8% in 48 days) | biosafety (100% rice seed germination) | (121), 2021 |

| TMPyP | HKUST-1 | light irradiation (day/night temperature was 25/18 °C, photoperiod was 15/9 h, and the humidity was at 60–80% (irradiance of 9 mW cm–2 and energy of 3.18 kJ cm–2) | photodynamic fungicidal activity (P. syringae pv lachrymans and C. michiganense subsp. Michiganense), efficacy (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum), and safety to plants (cucumber and Chinese cabbage) | (108), 2021 |

The table is organized according to the agrochemical, followed by the MOF-based material name (or chemical formula), loading capacity (wt % or mmol·g–1), release conditions, and activity tests. C: chitosan; CMCS: carboxymethyl chitosan; DMF: N,N′-dimethylformamide; EDTA: ethylenediaminetetraacetate; GSH: glutathione; HLF-1: human lung fibroblast; IC50: half maximal inhibitory concentration; KT50: 50% knockdown time; LC50: median lethal concentration; OPA: oxalate-phosphate-amine; P: pectin; PBS: phosphate buffer saline; PD: prochloraz (P) and 2,4-dinitrobenzaldehyde (D); PDA: polydopamine; SL: sodium lignosulfonate; TA: tannic acid; TMPyP: 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridinio)porphyrin tetra(p-toluenesulfonate).

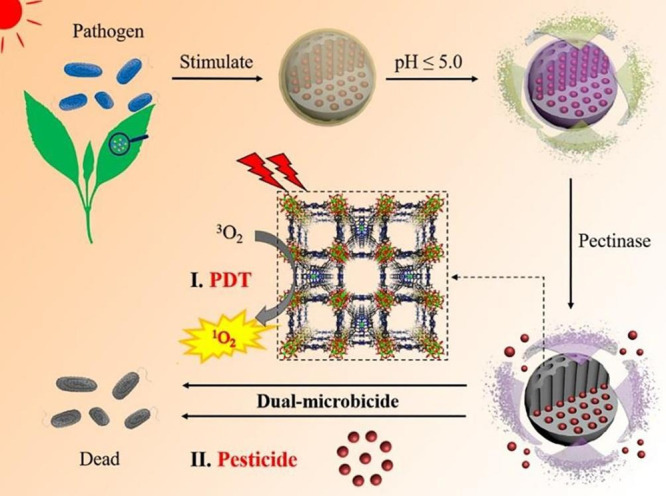

In 2017, Yaghi and co-workers described a naturally degradable MOF as a carrier of the important fumigant cis-1,3-dichlorophropene (1,3-DCPP).105 The MOF [Ca14(l-lactate)20(acetate)8X] (X: C2H5OH, H2O, or MOF-1201), constructed from Ca2+ ions and l-lactate, presents apertures and an internal diameter of 7.8 and 9.6 Å, respectively, and a permanent porosity of 430 m2·g–1. MOF-1201 can efficiently encapsulate the 1,3-DCPP agrochemical with a total pesticide loading of 1.4 mmol·g–1 (13 wt %). Originally, the fumigant release study was performed using an air flow, demonstrating a slow release when purging samples of the 1,3-DCPP loaded MOF (1,3-DCPP@MOF-1201) in an air flow of 1.0 cm3·min–1. The loaded 1,3-DCPP@MOF-1201 showed a 100 times slower release compared to that of the liquid 1,3-DCPP, achieving 80% of the total release in 100 000 min·g–1. Porphyrinic MOFs have also been described as promising carriers of fungicides.106 Particularly, PCN-224 was loaded (30 wt %) with tebuconazole and constructed layer by layer with chitosan and pectin to get tebuconazole microcapsules. The synthesized microcapsules (Tebuc@PCN@P@C) had a dual-microbial effect on plant bacterial and fungal diseases (Figure 5). First, the tebuconazole previously loaded in the microcapsules was gradually released (87% in 7.25 days) after the pectin layer was decomposed by the pectinase released by the invading pathogen. Second, the singlet oxygen (1O2) was released from the organic linker porphyrin when the MOF NPs were exposed to light after the formation of pectin to inhibit the pathogens. The synthesized compound displayed excellent double activities of having photodynamic therapy and being microbicidal against the bacteria X. campestris pv campestris (82.4% and 18.4% under light and dark, respectively) and P. syringae pv tomato (56.3% and 9.5% under light and dark, respectively) and the fungi A. alternate (68.0%). Finally, the authors studied the safety of this compound against Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa pekinensis) in a greenhouse environment. The results demonstrated that the synthesized microcapsules do not have a major effect on both the fresh weight and the soil plant analysis development (SPAD) value of the tested plant leaf, so the Tebuc@PCN@P@C microcapsules can be considered safe.

Figure 5.

Mechanism of triggered tebuconazole release and the illustration of the dual-microbicidal effect of the Tebuc@PCN@P@C microcapsules. Reprinted from ref (106). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

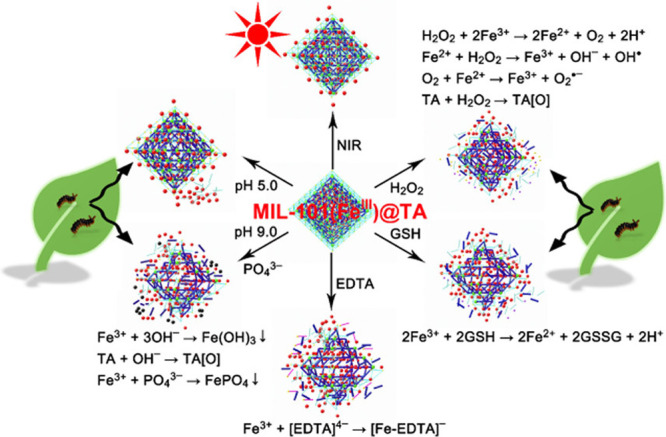

A very recent and complete study described a further example of a tebuconazole loaded MOF, the MIL-101(Fe) gated with FeIII-tannic acid (TA) networks.107 The FeIII-TA complexes are able to absorb UV–vis near-infrared (NIR) lights. The design of MIL-101(Fe)-TA NPs enables the release of the tebuconazole cargo (24.1 wt %) in response to 7 stimuli (i.e., acidic pH, alkaline pH, H2O2, glutathione (GSH), phosphate, ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA), and sunlight) to meet the diverse controlled release of the encapsulated cargo (Figure 6). Tebuconazole is gradually released from the gated MIL-101(Fe) when the pH decreases to 5.0 as a result of the partial disassembly of FeIII-TA networks, and a significant delivery of the pesticide occurred when the pH increases to 9.0 owing to both the disassembly of the FeIII-TA networks and the degradation of the MIL-101(Fe). This is important since, in various parts of the plants themselves or caused by pest and pathogens, there are different pH values. Further, when crop plants suffer from biotic or abiotic stress, H2O2 is rapidly produced in cells. On the basis of the Fenton reaction between H2O2 and FeII/FeIII, the release of the cargo will be induced by the degradation of MIL-101(Fe). GSH, normally found in plants and animals, is able to reduce FeIII to FeII, causing the degradation of MIL-101(Fe) and, then, promoting the release of the encapsulated pesticide. Additionally, phosphates can induce MIL-101(Fe) degradation by competitive coordination with FeIII, and finally, the FeIII-TA networks on MIL-101(Fe) will stimulate the controlled release of the pesticide via the photothermal effect of the NIR light of sunlight. Lastly, this system demonstrated high fungicidal activities against R. solani (rice sheath blight; concentration for 50% of the maximal effect, ED50: 0.4960 mg·L–1 after 48 h) and F. gaminearum (wheat head blight; ED50: 0.5658 mg·L–1 after 48 h); good safety in seed germination, seedling emergence, and plant height of wheat by seed dressing; satisfactory control efficacies on wheat powdery mildew caused by B. graminis.

Figure 6.

Stimuli-responsive controlled release in MIL-101(FeIII) nanopesticides gated with FeIII-TA networks related to the biological and natural environments of crops and stimuli-responsive mechanisms. TA[O] represents the oxidation product of TA. Reprinted with permission from ref (107). Copyright 2020 Elsevier Inc.

Finally, we want to mention a report on the construction of a porphyrin MOF nanocomposite constructed by incorporating 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(1-methyl-4-pyridinio)porphyrin tetra(p-toluenesulfonate) (TMPyP) as a photosensitizer (PS) in the cage of HKUST-1 (or CuBTC, [Cu3(btc)2(H2O)3]) (HKUST: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, SBET ∼ 1300–1600, Vp ∼ 0.71 cm3·g–1) to efficiently produce singlet oxygen to inactivate plant pathogens under light irradiation.108 The prepared PS@HKUST-1 loaded about 12 wt % of PS, exhibiting an excellent and broad-spectrum photodynamic antimicrobial activity in vitro against three plant pathogenic fungi (S. sclerotiorum, P. aphanidermatum, and B. cinerea with >80%, 60%, and 80% efficiency at concentrations of 200, 50, and 200 mg·L–1, respectively) and two pathogenic bacteria (P. syringae pv lachrymans and C. michiganense subsp. Michiganense). Besides, Allium cepa chromosome aberration assays confirmed that PS@HKUST-1 showed no genotoxicity and safety to the growth of cucumber and Chinese cabbage.

Thus, considering all the mentioned examples, the controlled release of agrochemicals from MOFs and MOF composites is an emerging research field that has demonstrated a great potential as an alternative and efficient new strategy to release plant nutrients but also control pests in agricultural applications.

6. MOFs as Sensors of Agrochemicals

Considering the important detrimental effect of pesticides on human health, researchers have extensively studied and discussed the pretreatment, extraction, detection, and determination of agrochemical residues in water, fruits, and vegetables. These data have been valuable to food analysts and regulatory authorities for monitoring the quality and safety of fresh food products, among others. As would be expected, MOFs and MOF composites have been extensively proposed for the extraction and determination of these dangerous substances in food and water. Many different agrochemicals have been analyzed using MOFs: (i) herbicides, ametryn, amidosulfuron, ATZ, atraton, bensulfuron methyl, bis(p-nitrophenyl) phosphate, butachlor, carbaryl, chlorimuron ethyl, 2,4-dichlorophenol, 4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid (4-CPA), chlortoluron, 2,4-D, dicamba, desmetryn,2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy)propionic acid (2-DPP), chlorotoluron, dipropetryn, epoxide, fenuron, fluometuron, glufosinate, GLY, heptachlor prometryn, MCPA, (2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxy) butyric acid (MCPB), (2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxy) propionic acid (MCPP), metsulfuron methyl, monuron, nicosulfuron, metazachlor, molinate, nitrofen, paraquat, pretilachlor, prometon, propanil, pyrazosulfuron ethyl, secbumeton, simazine, sulfometuron methyl, sulfosulfuron, terbumeton, terbuthylazine, thifensulfuron methyl, trietazine, and trifluralin; (ii) fungicides: bromuconazole, carbendazim, chlorothalonil, 2,6-dichloro-4-nitroaniline (2,6-DN), difenoconazole, diniconazole, epoxiconazole, fenbuconazole, flusilazole, flutriafol, hexachlorobenzene, hexaconazole, iprodione, myclobutanil, penconazole, prochloraz, propiconazole, pyraclostrobin, pyrimethanil, tebuconazole, thiabendazole, thiophanate methyl, and triadimefon; (iii) insecticides: aldrin, avermectin, azinphos methyl, bifenthrin, bromopropylate, carbofuran, chlordane, chlorfluazuron, chlorpyrifos, clethodim, clofentezine, coumaphos, β-cyfluthrin, cyhalothrin, cyphenothrin, deltamethrin, diazinon, o,p′- and p,p′-1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethylene (DDE), p,p′-1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethylene (p,p′-DDD), dichlorvos, dieldrin, difenoxuron, diflubenzuron, dimethoate, diniconazole, dinotefuran, α- and β-endosulfan, fenitrothion, fenpropathrin, fenthion, fenvalerate, flufenoxuron flumetralin, α-, β-, γ-, and δ-hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), hexaflumuron, imidacloprid, isocarbophos, lufenuron, malathion (also named carbophos), monocrotophos, NIT, nitenpyram, p-nitrophenyl phosphate, matrine, methamidophos, paraoxon, paraoxon ethyl, parathion, parathion methyl, penfluoron, permethrin, phosalone, pirimiphos, procymidone, profenofos, pyridaben, pyrimicarb, quinalphos, teflubenzuron, triazophos, thiamethoxam, tribenuron methyl, trichlorfon, o,p′- and p,p′-1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethylene (DDT), 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(4chlorophenyl)ethane, triflumuron, and thiacloprid; (iv) plant growth hormones: forchlorfenuron, 6-benzylaminopurin, indole-3-acetic acid, 3-indolebutyric acid, and indolepropionic acid.

In 2010, Wen et al. reported one of the first works about the application of MOFs in the efficient detection of agrochemicals. In this study, a new MOF, named [Cd(2,2′,4,4′-bptcH2)]n (2,2′,4,4′-bptcH4: 2,2′,4,4′-biphenyltetracarboxylic acid), that was thermally stable and luminescent was prepared via a hydrothermal reaction.122 This material was tested as a solid-phase extraction (SPE) material for the detection of trace levels of organophosphate pesticide (OP) via stripping voltametric analysis. The determination of parathion methyl as a model included two main steps: parathion methyl adsorption and electrochemical stripping detection of adsorbed pesticide. The MOF modified glass carbon electrode was immersed into a sample solution containing the desired parathion methyl concentration, and the peak currents increased rapidly with the immersion time, up to 12 min, which indicated the saturation. The calculated limit of detection (LOD: 0.0006 μg·mL–1) is comparable with that of 0.0048 μg·mL–1 at a hanging mercury drop electrode, suggesting that the reported MOF is reliable for the determination of OPs in water. The same year, Barreto et al. reported the evaluation a new adsorbent 3D MOF [(La0.9Eu0.1)2(DPA)3(H2O)3] (H2DPA: pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid) for the determination of pesticides from four chemical classes, namely, organochlorine (endosulfan), organophosphate (malathion and parathion methyl), dicarboximide (procymidone), and carbamate (pirimicarb) in fresh lettuce (Lactuca sativa) by matrix solid-phase dispersion (MSPD) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/MS).123 The recoveries obtained ranged from 78% to 107% with relative standard deviation (RSD) values between 1.6% and 8.0%. The LOD and limit of quantification (LOQ) ranged from 0.02 to 0.05 mg·kg–1 and from 0.05 to 0.1 mg·kg–1, respectively, for the different pesticides studied. Importantly, the comparison with a conventional sorbent (silica gel) showed better performance of the MOF sorbent for all tested pesticides. However, the reasons of this improvement are not investigated or discussed by authors. Later on, in 2017, Tao et al.124 originally synthesized a tetraphenylethene-based ligand (BPyTPE: (E)-1,2-diphenyl-1,2-bis(4-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)ethene) with a trans conformation and prominent AIE properties. On the basis of BPyTPE, a novel 2D pillared-layered LMOF [Zn2(bpdc)2(BPyTPE)] (H2bpdc: biphenyl-4,40-dicarboxylic acid) was developed showing a 3-fold interpenetration structure. The activated material (without solve) exhibits a strong blue-green emission at 498 nm with an important φF of 99%. The emission of the MOF without solvent can be quenched selectively and effectively by 2,6-DN. Thus, the authors established a method to quantitatively and sensitivity detect trace 2,6-DN with a linear range of 0.94–16.92 ppm and a low detection limit of 0.13 ppm.

When one considers these outstanding original works, MOFs have opened a new opportunity for the development of efficient techniques to detect agrochemicals. However, most of these materials are more or less sensitive to moisture or water and can be degraded through hydrolysis. Only few MOFs can maintain their stability in water or a moist environment. One example is the previously reported luminescent Zr-MOF CAU-24, based on the C-centered orthorhombic arrangement cluster [Zr6(μ3-O)4(μ3-OH)412+] bridged by TCPB4– linkers in a scu topology (H4TCPB: 1,2,4,5-tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl)benzene; SBET: 1450 m2·g–1; rhombic channels of ∼10 × 5.3 and ∼3.5 × 2.4 Å2, Figure 7). This material demonstrated a rapid, sensitive, and in situ detection of OP pesticides.125 Along the 22 pesticides tested, the synthesized CAU-24 quickly absorbs trace amounts of OP parathion methyl and indicates its presence. It has a low LOD of 0.115 μg·kg–1 (0.438 nM) with a wide linear range from 70 μg·kg–1 to 5.0 mg·kg–1. The water stability of this Zr-MOF was investigated by suspending it in water for 24 h and monitoring by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), adsorption/desorption isotherms, and pore distribution. The crystalline structure and porosity of the Zr-MOF was kept in water after 24 h. Finally, the Zr-MOF was used to mimic rapid in situ imaging detection of pesticide residues on surface vegetables (lettuce and cowpea); visual signals appeared under UV light within 5 min. Therefore, this MOF has the possibility for low-cost, rapid, and in situ imaging detection of OP contamination via easy-to-read visual signals.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the synthesis of CAU-24 and its application for OP pesticide sensing. Insets show the blue fluorescence of the aqueous solution of this Zr-MOF before and after quenching by target parathion methyl in an aqueous solution and directly applied on the surface of vegetable surfaces. Reprinted with permission from ref (125). Copyright 2014 Elsevier B.V.

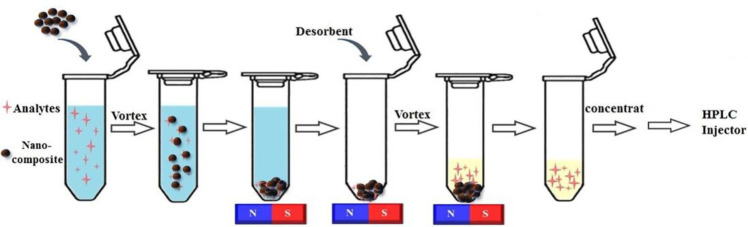

MOF composites have also been used in the determination of agrochemicals. In 2014, a MOF with an iron oxide enclosure was reported for the determination of OPs in biological samples.126 In this work, MIL-101(Fe) was modified as a model with superparamagnetic qualities using Fe3O4 to form a homogeneous magnetic product (Fe3O4/MIL-101 composite). The Fe3O4/MIL-101 composite was investigated for the magnetic solid-phase extraction of six OPs from human hair and urine samples followed by gas chromatography analysis. Under optimized conditions (desorption solvent, extraction time, desorption time, etc.), this method showed low LOD (0.21–228 ng·mL–1), wide linearity, and good precision (1.8–8.7% for intraday, 2.9–9.4% for interday). The adequate recoveries of the spiked samples were 76.8–94.5% and 74.9–92.1% for hair and urine, respectively, suggesting that the Fe3O4/MIL-101 sorbent is feasible for the analysis of trace OPs in biological samples. Other Fe3O4-MOF-based composites have recently been reported for the efficient determination of different agrochemicals, for example, the magnetic solid-phase extraction method based on the attapulgite-modified MOF (ATP@Fe3O4@ZIF-8) in the determination of bezoylureas (insecticides; see Table 3).127 ATP, an eco-friendly nature and low-cost clay, is added here to improve the hydrolytic stability of ZIF-8 as the −OH groups of ATP can selectively coordinate with the metal ions in ZIF-8. The ATP@Fe3O4@ZIF-8 nanocomposite was applied as a sorbent for the magnetic solid-phase extraction (MSPE) of benzoylureas prior to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) determination (Figure 8). The established method was validated in terms of linearity (2.5–500 μg L–1 with satisfactory recovery of 88.29–95.99%) and precision (relative standard deviation, RSD, of <8%). Moreover, after 5 cycles, there was hardly any noticeable loss of the extraction efficiency. Finally, this method was effectively used in the determination of 6 benzoylureas in different tea infusions; the determined relative recoveries ranged from 78.8% to 114.3%.

Figure 8.

Schematic view of the MSPE procedure when using ATP@Fe3O4@@ZIF-8 in benzoylureas determination (N: North; S: South). Reprinted with permission from ref (127). Copyright 2020 Elsevier Ltd.

Another example of magnetic solid-phase extraction using Fe3O4@ZIF-8-based composites is the work reported by Senosy et al. on the basis of the synthesis of Fe3O4@APTES-GO/ZIF-8 (APTES: (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane; GO: graphene oxide) and its evaluation as an adsorbent for the determination of triazole fungicides in water, honey, and fruit juices.128 Here, GO sheets were used to improve the dispersion of the adsorbent in aqueous solutions and, again, ZIF-8 to ensure enough surface area and active sites. Under the optimum conditions (extraction time, pH value of the sample, etc.), the obtained linearity of this method ranged from 1 to 1000 μg·L–1 for all analytes. The LODs and LOQs of four triazole fungicides ranged from 0.014 to 0.109 μg L–1 and from 0.047 to 0.365 μg L–1, respectively. Moreover, this adsorbent could be reused without significant loss of its extraction recoveries. When compared with the outcomes from other studies, Fe3O4@APTES-GO/ZIF-8-MSPE could provide a higher performance and achieve satisfactory results for the analysis of trace triazole fungicides in complex matrices. Another composite, based on a nanoarchitecture of Mxene/carbon nanohorns/β-cyclodextrin-MOF (MXene/CNHs/β-CD-MOFs), was utilized as an electrochemical sensing platform for the determination of carbendazim pesticide.129 β-CD-MOFs combined the properties of the host–guest recognition of β-CD and porous structure, high porosity, and pore volume of MOFs, which are fundamental in achieving a high adsorption capacity of carbendazim. MXene/CNHs possess a large specific surface area, accessible active sites, and high conductivity, which allowed more mass transport channels and enhanced the mass transfer capacity and catalysis of carbendazim.123,126,128 With the collaborative effect of both (β-CD-MOFs and MXene/CNHs), the electrode extended a wide linear range from 3.0 nM to 10.0 μM and a low LOD of 1.0 nM. Additionally, this sensor also showed high selectivity, reproducibility, and long-term stability as well as satisfactory application in tomato samples.

7. Perspectives in Using MOFs in Agriculture

As a novel class of materials, MOFs exhibit a great potential in agroindustry, either to detect or eliminate agrochemicals or to achieve their sustained and controlled release. In all these scenarios, the aim is to reach the rational and environmentally friendly use of agrochemicals. Despite the novelty of MOFs in agriculture, the experience acquired in other areas (particularly biomedical and environmental ones) allow us to identify precise challenges related to their use in agriculture.

First, MOF stability under the working conditions is of crucial relevance. However, from the wide number of MOFs and MOF-based composites reported in environmental remediation (water and soil), only few discuss this critical point and mostly under conditions far from real water streams or fields. In this sense, many of these materials are built up from toxic metals (e.g., Cr, Ag) and/or harmful organic moieties (e.g., porphyrins), which can be released upon the MOF degradation. The selection of safe and stable MOFs is therefore mandatory for their use in agroindustry (mainly for environmental remediation and agrochemical controlled release). Further, it is essential to investigate the performance of MOFs under real conditions using complex water and soil compositions and/or vegetables or plants (e.g., river water, real fields or greenhouses, vegetables, products, etc.), considering concentration ranges found in nature, different temperatures, humidity, sunlight hours, soil composition, or pH in different parts of plants, among others.

Second, the cost of MOFs is of particular importance for agroindustry applications. When one takes into account that vegetables and fruits are normally popular and affordable, it is necessary to use a low-cost and long-lifetime material. Nontoxic and abundant safe precursors together with simple synthetic routes with a high space time yield (STY; kilogram of MOF produced per cubic meter of reaction per day) (toxic solvents, expensive ligands, etc.) need to be put in place for the most promising candidates. Note here that few MOFs have been produced so far at the ton scale by different companies, and thus, they are not currently commercially available.218 To further progress through the application, specific manufacturing and devices should be considered (pellets, columns, membranes, etc.), and one needs to take into account the potential decrease in the MOF performance.

Finally, understanding the interaction of the agrochemicals and MOFs might help one further improve the resulting performances at the detection, removal, or progressive release stages. Also, research could be focused on multifunctional MOFs and MOF composites that combine, for instance, the extraction with the detection of pesticides in food matrices or the simultaneous elimination of different agrochemicals.

Although there are challenges to the use of MOFs in agriculture, this new domain in the application of MOFs will continue, and it is expected that novel knowledge and development will soon be the outcome. This Review opens fascinating perspectives for the safe and efficient MOF application in agriculture.

Acknowledgments