Abstract

The emergence of resistant enteropathogens has been reported worldwide. Few data are available on the contemporary in vitro activities of commonly used antimicrobial agents against enteropathogens causing traveler's diarrhea (TD). The susceptibility patterns of antimicrobial agents currently available or under evaluation against pathogens causing TD in four different areas of the world were evaluated. Pathogens were identified in stool samples from U.S., Canadian, or European adults (18 years of age or older) with TD during 1997, visiting India, Mexico, Jamaica, or Kenya. MICs of 11different antimicrobials were determined against 284 bacterial enteropathogens by the agar dilution method. Ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ceftriaxone, and azithromycin were highly active in vitro against the enteropathogens, while traditional antimicrobials such as ampicillin, trimethoprim, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole showed high levels and high frequencies of resistance. Rifaximin, a promising and poorly absorbable drug, had an MIC at which 90% of the strains tested were inhibited of 32 μg/ml, 250 times lower than the concentration of this drug in the stools. Amdinocillin, nalidixic acid, and doxycycline showed moderate activity. Fluoroquinolones are still the drugs of choice for TD in most regions of the world, although our study has a limitation due to the lack of Escherichia coli samples from Kenya and possible bias in selection of the patients for evaluation. Azithromycin and rifaximin should be considered as promising new agents. The widespread in vitro resistance of the traditional antimicrobial agents reported since the 1980s and the new finding of resistance to fluoroquinolones in Southeast Asia are the main reasons for monitoring carefully the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns worldwide and for developing and evaluating new antimicrobial agents for the treatment of TD.

Traveler's diarrhea is a syndrome that occurs when people cross international borders from the developed to tropical or semitropical developing countries. Traveler's diarrhea is usually defined as the passage of three or more loose stools within 24 h associated with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or cramps, fecal urgency (tenesmus), or dysentery (bloody diarrhea) (5). Approximately 80% of traveler's diarrhea cases with an identified pathogen are caused by bacteria, including enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), recently identified enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) (13, 14), Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Plesiomonas shigelloides, Aeromonas spp., and non-cholera-causing vibrios (3, 5, 27, 31).

Antimicrobial therapy is indicated for moderate to severe disease to reduce the duration of illness (5, 7, 25). Traditionally, ampicillin, trimethoprim, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and doxycycline have been used for the treatment of traveler's diarrhea, while more recently fluoroquinolones have been recommended as the drugs of choice (5, 7, 25). Resistance to commonly used antimicrobial agents among enteric bacterial pathogens has been reported worldwide (2, 11, 13, 15, 18, 20, 22, 23, 28, 29), although data for resistance among pathogens causing traveler's diarrhea are limited. The in vitro activities of currently available and new antimicrobial agents were evaluated against pathogens causing traveler's diarrhea isolated in four different areas of the world during 1997.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

Stool samples were collected from U.S., Canadian, or European adults 18 years of age or older with traveler's diarrhea who were enrolled in treatment clinical trials in Guadalajara (Mexico), Ocho Rios (Jamaica), Goa (India), and Mombasa (Kenya) during 1997.

Bacterial pathogens.

A total of 284 bacterial isolates were evaluated in this study including ETEC, EAEC, Salmonella. spp., Shigella spp., non-Vibrio cholerae vibrios, Aeromonas spp., P. shigelloides, and Campylobacter spp. All bacterial enteropathogens were identified by previously described microbiological methods (14), including DNA hybridization for ETEC (16) and HEp-2 adherence assay for EAEC (9, 14). The distribution by geographic site of the enteropathogens is shown in Table 1. E. coli samples from Kenya were not available to be tested for ETEC or EAEC.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of pathogens tested from four geographic regionsa

| Pathogens | No. (%) tested

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Jamaica | Mexico | Kenya | Total | |

| ETEC | 61 | 18 | 18 | NAb | 97 (34) |

| EAEC | 44 | 19 | 12 | NA | 75 (26) |

| Salmonella spp. | 24 | 1 | 3 | 18 | 46 (16) |

| Shigella spp. | 23 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 36 (13) |

| Non-V. cholerae vibrios | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 (2) |

| Plesiomonas spp. | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10 (4) |

| Aeromonas spp. | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 (1) |

| Campylobacter spp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 (3) |

| Total | 168 | 41 | 38 | 37 | 284 (100) |

The organisms were obtained from a collaborative study that has been described in other publications (27, 31).

NA, not available.

Antimicrobial agents.

The following antimicrobial agents were evaluated: ampicillin (AMP; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), trimethoprim (TMP; Sigma), TMP/sulfamethoxazole (SXT; Sigma), doxycycline (DOX; Sigma), nalidixic acid (NAL; Sigma), amdinocillin (MEC; Leo Pharmaceutical Products, Copenhagen, Denmark), ceftriaxone (CRO; Sigma), ciprofloxacin (CIP; Medlatech Inc., Herndon, Va.), levofloxacin (LVX; Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Spring House, Pa.), azithromycin (AZM; Pfizer Inc., Brooklyn, N.Y.), and rifaximin (RFX; Alfa Wassermann, Bologna, Italy), a new poorly absorbable rifamycin (8).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

MICs of the 11 antimicrobial agents were determined by the agar dilution method following the recommendations of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) (17). Non-Campylobacter organisms were incubated on Mueller-Hinton agar plates at 35oC for 16 to 20 h, while Campylobacter sp. strains were incubated on Mueller-Hinton agar with 5% lysed sheep blood at 42oC for 48 h under a microaerobic atmosphere including CO2. Sixteen strains of vibrios, P. shigelloides, and Aeromonas spp. from India were not available for testing of CRO and AZM. Control strains of E. coli (ATCC 25922), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29212) were used for quality control. SXT was used with a TMP/sulfamethoxazole ratio of 1 to 19, as recommended by the NCCLS (17).

RESULTS

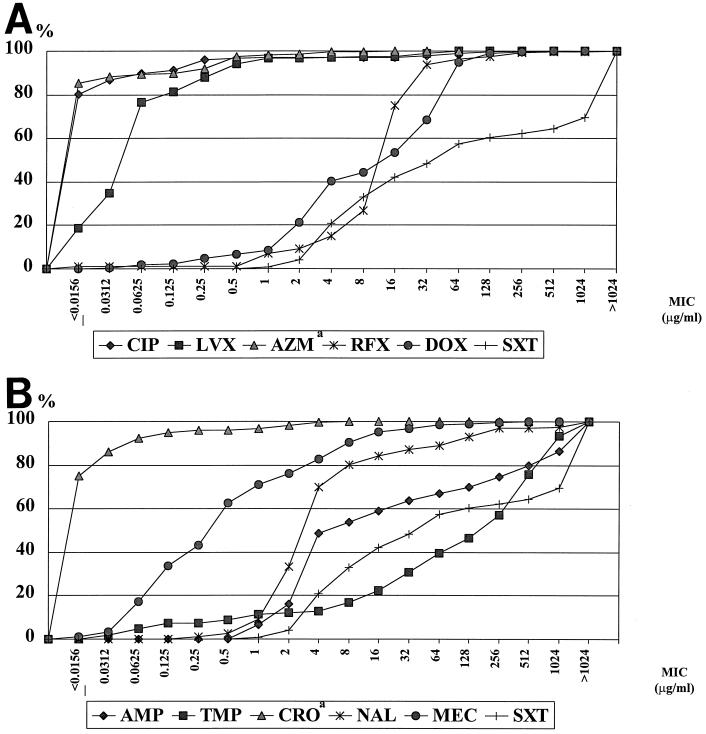

Table 2 shows the range of MICs of each antimicrobial for the study pathogens, MIC50 (concentration required to inhibit the growth of 50% of the strains), and MIC90 (concentration required to inhibit the growth of 90% of the strains). CIP and LVX were highly active against all pathogens (unfortunately, ETEC and EAEC samples from Kenya were not available, as mentioned above.), with MIC90s of 0.125 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively. AZM and CRO showed high in vitro activity against the pathogens including Campylobacter spp. MIC90 = 0.0625 μg/ml for both), although 16 isolates of non-cholera-causing vibrios, P. shigelloides, and Aeromonas spp. from India were not available for testing for these agents. Traditional antimicrobials, including AMP, TMP, and SXT, showed low activity against all enteropathogens (MIC90 = 1,024 to >1,024 μg/ml). MEC and DOX showed moderate activity (MIC90 = 8 and 64 μg/ml, respectively), still more active than traditional agents but less active than the fluoroquinolones tested. RFX also showed intermediate activity with an MIC50 of 16 and an MIC90 of 32 μg/ml. Cumulative percentages for the 284 bacterial enteropathogens for each antimicrobial are presented in Fig. 1. Although the clinical relevance of using the NCCLS breakpoints (17) for treatment of TD is controversial, the percentages of resistant strains among the 284 pathogens were analyzed: 40.9% were resistant to AMP (the NCCLS breakpoint MIC is ≥32 μg/ml), 83.1% were resistant to TMP (MIC ≥ 16 μg/ml), 79.2% were resistant to SXT (MIC ≥ 8/152 μg/ml), 59.7% were resistant to DOX (MIC ≥ 6 μg/ml), 15.8% were resistant to NAL (MIC ≥ 32 μg/ml), 9.4% were resistant to MEC (MIC ≥ 16 μg/ml for urinary pathogens according to the Swedish Reference Group; the NCCLS breakpoint is not available), 2.9% were resistant to CIP (MIC ≥ 4 μg/ml), 2.8% were resistant to LVX (MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml), and 0% were resistant to CRO (MIC ≥ 32 μg/ml). The breakpoints of RFX and AZM for enteropathogens are not available from NCCLS.

TABLE 2.

MICs of 11 antimicrobial agents for 284 enteropathogens

| Antimicrobial | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 90% | Range | |

| AMP | 8 | >1,024 | 1–>1,024 |

| DOX | 16 | 64 | 0.0312–512 |

| NAL | 4 | 128 | 0.25–>1,024 |

| TMP | 256 | 1,024 | 0.0312–>1,024 |

| SXT | 64 | >1,024 | 1–>1,024 |

| CROb | ≤0.0156 | 0.0625 | ≤0.0156–8 |

| MEC | 0.5 | 8 | ≤0.0156–512 |

| CIP | ≤0.0156 | 0.125 | ≤0.0156–256 |

| LVX | 0.0625 | 0.5 | ≤0.0156–64 |

| AZMb | ≤0.0156 | 0.0625 | ≤0.0156–16 |

| RFX | 16 | 32 | ≤0.0156–>1,024 |

50% and 90%, MICs required to inhibit the growth of 50 and 90% of the strains tested, respectively.

Data for CRO and AZM are based on 268 pathogens. Sixteen isolates (non-V. cholerae, P. shigelloides, and Aeromonas spp.) from India were not included in this part of the study.

FIG. 1.

(A) Cumulative percentages for 284 enteropathogens of MICs of CIP, LVX, AZM, RFX, DOX, and SXT. The data for AZM are based on 268 isolates; 16 isolates from India were not available. (B) Cumulative percentages for 284 enteropathogens of MICs of AMP, TMP, CRO, NAL, MEC, and SXT. The data for CRO are based on 268 isolates; 16 isolates from India were not available. The data for SXT are presented twice for comparison with other agents.

In Table 3, the distributions of the MICs of 11 antimicrobial agents are given by region. Differences were seen for individual antimicrobials, but no overall pattern of increased or decreased susceptibility was seen by area of study.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of MICs (μg/ml) of 11 antimicrobial agents by geographic area

| Antimicrobial | India (n = 168)

|

Jamaica (n = 41)

|

Mexico (n = 38)

|

Kenya (n = 37)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC50a | MIC90b | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | MIC50 | MIC90 | |

| AMP | 8 | >1,024 | 4 | 1,024 | 4 | >1,024 | 4 | 32 |

| DOX | 16 | 64 | 4 | 16 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 128 |

| NAL | 4 | 256 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| TMP | 256 | 1,024 | 16 | 1,024 | 256 | 512 | 128 | 1,024 |

| SXT | 512 | >1,024 | 8 | 32 | 8 | >1,024 | 64 | 256 |

| CROc | ≤0.0156 | 0.0625 | ≤0.0156 | 0.0625 | ≤0.0156 | 0.0625 | ≤0.0156 | 4 |

| MEC | 0.5 | 16 | 0.125 | 8 | 0.125 | 8 | 0.5 | 4 |

| CIP | ≤0.0156 | 0.25 | ≤0.0156 | 0.0312 | ≤0.0156 | ≤0.0156 | ≤0.0156 | 0.0312 |

| LVX | 0.0625 | 1 | 0.0625 | 0.25 | 0.0625 | 0.0625 | ≤0.0156 | 0.25 |

| AZMc | ≤0.0156 | ≤0.0156 | ≤0.0156 | ≤0.0156 | ≤0.0156 | ≤0.0156 | 0.5 | 2 |

| RFX | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 256 |

MIC50, MIC required to inhibit the growth of 50% of the strains tested.

MIC90, MIC required to inhibit the growth of 90% of the strains tested.

Data for CRO and AZM are based on 268 pathogens. Sixteen isolates (non-cholera causing vibrios, P. shigelloides, and Aeromonas spp.) from India were not included in this part of the study.

Susceptibilities of specific enteric bacterial pathogens to antimicrobial agents are given in Table 4. AMP showed moderate activity against Salmonella isolates (MIC90 = 4 μg/ml). Both TMP and SXT had low activity against ETEC, EAEC, Salmonella spp., and Shigella spp. but had moderate activity against the remaining pathogens. DOX showed lower activity against ETEC, EAEC, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., and Campylobacter spp. (MIC90 = 64 μg/ml) than against vibrios, P. shigelloides, and Aeromonas spp. (MIC90 = 0.25 to 32 μg/ml). NAL was less active against ETEC, EAEC, and non-cholera-causing vibrios (MIC90 = 128 to 256 μg/ml) but was moderately active against Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Aeromonas spp., P. shigelloides, and Campylobacter spp. (MIC90 = 1 to 16 μg/ml). Of note, for fluoroquinolone resistance, for seven strains from India (three ETEC and four EAEC), the MICs of CIP and LVX were ≥32 μg/ml.

TABLE 4.

Distribution of MICs of 11 antimicrobial agents by enteropathogen

| Antimicrobial | MIC90 (μg/ml)a (no. of strains)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETEC (97) | EAEC (75) | Salmonella (46) | Shigella (36) | Campylobacter (9) | Othersc (21) | |

| AMP | >1,024 | >1,024 | 4 | 512 | 64 | 512 |

| DOX | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 4 |

| NAL | 256 | 128 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 32 |

| TMP | 1,024 | >1,024 | 1,024 | 1,024 | 64 | 128 |

| SXT | >1,024 | >1,024 | 512 | >1,024 | 128 | 4 |

| CROb | ≤0.0156 | 0.0312 | 0.125 | 0.0312 | 2 | NA |

| MEC | 8 | 16 | 2 | 16 | 4 | 1 |

| CIP | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.0312 | 0.0312 | 0.0625 | ≤0.0156 |

| LVX | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.0625 |

| AZMb | ≤0.0156 | ≤0.0156 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | NA |

| RFX | 32 | 32 | 64 | 64 | 32 | 4 |

MIC90, MIC required to inhibit the growth of 90% of the strains tested.

Data for CRO and AZM are based on 268 pathogens. Sixteen isolates (non-cholera-causing vibrios, P. shigelloides, and Aeromonas spp.) from India were not included in this part of the study.

Others include non-cholera-causing vibrios, P. shigelloides, and Aeromonas sp. isolates.

There were a few differences in MICs among the four study areas by pathogen (data not given in tables). For Shigella isolates from Jamaica (three strains) the SXT MIC50 was 8 and the MIC90 was 32 μg/ml (range, 8 to 32 μg/ml), while the values for those from Kenya were 128 and 512 μg/ml, respectively; for the Shigella isolates from India and Mexico, the MIC50s and MIC90s were both higher than 1,024 μg/ml. For Salmonella spp. (18 strains) and Shigella spp. (5 strains) from Kenya, the AZM MIC50s and MIC90s were 0.5 and 4 and 0.5 and 16 μg/ml, respectively, while the MIC50 and MIC90 values for the same pathogens isolated in the remaining three sites were both ≤0.0156 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

ETEC, EAEC, Salmonella spp., and Shigella spp. isolated from four regions of the world during 1997 (ETEC and EAEC from Kenya were not available for testing) showed high-level resistance to TMP and SXT (MIC90 = 512 to >1,024 μg/ml). Resistance to SXT among enteric bacterial pathogens has increased dramatically over the last 14 years (2). Interestingly, the same level of resistance to these antimicrobial agents was not found among non-V. cholerae vibrios, Aeromonas spp., P. shigelloides, and Campylobacter spp. (MIC90 = 4 to 128 μg/ml), probably due to a small number of isolates. TMP or SXT should not be considered active against enteropathogens causing traveler's diarrhea and should not currently be recommended for empirical treatment of traveler's diarrhea regardless of the region of the world.

While AMP showed a pattern of activity similar to that of the drugs mentioned above, DOX, another traditional antimicrobial agent, remained moderately active, with MICs similar to those published in 1983 (2). The MIC50 and MIC90 of DOX for ETEC in 1983 were 2 and 32 μg/ml, respectively, and in the current study they were found to be 4 and 64 μg/ml. Because of the high concentration of DOX in stool (10), this drug may be useful in the treatment of traveler's diarrhea and may also play a role as a prophylactic drug for traveler's diarrhea when it is taken daily for malaria prevention.

In the present study, MEC also showed moderate activity against enteric bacterial pathogens, with an MIC90 of 8 μg/ml. MEC, a beta-lactam antibiotic, has been used to successfully treat shigellosis in children in studies carried out in Bangladesh (1, 24). It is a promising drug for therapy of traveler's diarrhea.

NAL was specifically tested in our study as it is still used for dysenteric illness in developing countries (1, 4, 21, 30), and it has been used in a screening test for prediction of fluoroquinolone resistance (26). Among the strains resistant to NAL, seven aforementioned strains (three ETEC and four EAEC) also showed resistance to fluoroquinolones as judged by the NCCLS breakpoint. The cross-resistance between these drugs raises concern about the emergence of future fluoroquinolone resistance (26).

Although resistance to both NAL and fluoroquinolones among ETEC isolates from travelers to India (29) and resistance to fluoroquinolones among Campylobacter sp. isolates in Thailand and Spain have recently been reported (11, 13, 18, 20), CIP and LVX remained active in vitro against bacterial enteropathogens causing traveler's diarrhea in this study. Both drugs showed excellent activity against all nine Campylobacter sp. strains tested from Mombasa, Kenya. There is unfortunately a limitation in our study, namely that ETEC and EAEC from Kenya were not available and that only a low number of Campylobacter isolates were available for this susceptibility testing. Additional studies with ETEC, EAEC, and Campylobacter isolates from various regions of the world are needed to reduce possible bias in the selection of stool specimens and to be certain that fluoroquinolones remain active.

In this study, CRO was active against the 268 enteropathogens studied (excluding the 16 isolates mentioned above). Although CRO has been used parenterally, especially for pediatric diarrheal diseases in developing countries, unfortunately there is no oral formulation of this drug, creating a limitation for its clinical use in the treatment of traveler's diarrhea. Orally administered broad-spectrum cephalosporins should be evaluated for therapy of traveler's diarrhea, based on the high CRO susceptibility pattern of the enteropathogens tested in this study.

AZM is an azole antibiotic related to macrolides which has good intracellular activity (19). In previous studies, it was found to be more active than erythromycin against ETEC, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Vibrio cholerae, and Campylobacter jejuni (19). Our study demonstrated that AZM was active against the 268 enteropathogens discussed above, including Campylobacter spp. However, the emergence of resistance to AZM among Campylobacter spp. in U.S. troops in Thailand has been reported (20). Due to the emergence of fluoroquinolone resistance among Campylobacter spp. (11, 13, 18, 20) and Salmonella typhi (22, 28), AZM could be an alternative antimicrobial agent for the therapy of traveler's diarrhea and typhoid fever. Preliminary data from one of our current clinical trials in Guadalajara, Mexico, showed promising results (J. A. Adachi and C. D. Ericsson, unpublished data). AZM would be the agent of choice for traveler's diarrhea in children, but further studies are needed to verify the effectiveness of the drug in treating the illness in children.

RFX has been evaluated for clinical use for traveler's diarrhea. In previous studies, this antimicrobial agent was more effective than SXT (6) and as effective as CIP in the therapy of traveler's diarrhea (H. L. DuPont, Z-D. Jiang, C. D. Ericsson, et al., submitted for publication). The MIC90 for the bacterial isolates tested in the present study was 32 μg/ml, which could easily be achieved in the intestinal lumen due to high fecal concentrations. RFX has been found to achieve a fecal concentration of up to 8,000 μg/g after 3 days of therapy (12).

Despite the limitation of our study, fluoroquinolones (CIP and LVX) should still be considered the drugs of choice for treatment of traveler's diarrhea in adults in most regions of the world and AZM and RFX should be considered as promising new agents. Future studies should monitor carefully the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of the enteropathogens isolated from traveler's diarrhea cases from around the world to detect the development of resistant strains early on.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Wei Li, John J. Mathewson, Barbara E. Murray, and Kavindra V. Singh for their support during the development of this study. We also thank Hideyasu Aoyama for his fine advice.

SmithKline Beecham Biologicals provided funding for the clinical trials in Goa and Kenya.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alan A N, Islam M R, Hossain M S, Mahalanabis D, Hye H K. Comparison of pivmecillinam and nalidixic acid in the treatment of acute shigellosis in children. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:313–317. doi: 10.3109/00365529409094842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson J R, Thornton S A, DuPont H L, West A H, Mathewson J J. Comparative in vitro activities of ten antimicrobial agents against bacterial enteropathogens. Antimicob Agents Chemother. 1983;24:509–513. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castelli F, Carosi G. Epidemiology of travelers' diarrhea. Chemotherapy. 1995;41(Suppl. 1):20–32. doi: 10.1159/000239394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Mol P, Met T, Lagasse R, Vandepitte J, Mutwewingabo A, Butzler J P. Treatment of bacillary dysentery: a comparison between enoxacin and nalidixic acid. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;19:695–698. doi: 10.1093/jac/19.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DuPont H L, Ericsson C D. Prevention and treatment of travelers' diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1821–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306243282507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuPont H L, Ericsson C D, Mathewson J J, Palazzini E, DuPont M W, Jiang Z D, Mosavi A, de la Cabada F J. Rifaximin: a nonabsorbed antimicrobial in the therapy of travelers' diarrhea. Digestion. 1998;59:708–714. doi: 10.1159/000007580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ericsson C D, DuPont H L. Travelers' diarrhea: approach to prevention and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:616–626. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillis J C, Brogden R N. Rifaximin, a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in conditions mediated by gastrointestinal bacteria. Drugs. 1995;49:467–484. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199549030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glandt M, Adachi J A, Mathewson J J, Jiang Z D, DiCesare D, Ashley D, Ericsson C D, DuPont H L. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli as a cause of travelers' diarrhea: clinical response to ciprofloxacin. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:335–338. doi: 10.1086/520211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heimdahl A, Kager L, Nord C E. Changes in the oropharyngeal and colon microflora in relation to antimicrobial concentrations in saliva and faeces. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1985;44:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoge C W, Gambel J M, Srijan A, Pitarangsi C, Echeverria P. Trends in antibiotic resistance among diarrheal pathogens isolated in Thailand over 15 years. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:341–345. doi: 10.1086/516303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Z-D, Ke S, Palazzini E, Riopel L, DuPont H L. In vitro activity and fecal concentration of rifaximin after oral administration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2205–2206. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2205-2206.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuschner R A, Trofa A F, Thomas R J, Hoge C W, Pitarangsi C, Amato S, Olafson R P, Echeverria P, Sadoff J C, Taylor D N. Use of azithromycin for the treatment of Campylobacter enteritis in travelers to Thailand, an area where ciprofloxacin resistance is prevalent. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:536–541. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathewson J J, Johnson P C, DuPont H L, Morgan D R, Thornton S A, Wood L V, Ericsson C D. A newly recognized cause of travelers' diarrhea: enteroadherent Eschrichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:471–475. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray B E. Resistance of Shigella, Salmonella, and other selected enteric pathogens to antimicrobial agents. Rev Infect Dis. 1986;8(Suppl. 2):S172–S181. doi: 10.1093/clinids/8.supplement_2.s172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray B E, Mathewson J J, DuPont H L. Utility of oligodeoxyribonucleotide probes for detecting enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:809–811. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.4.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 2nd ed. Approved standard M7–A2. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prats G, Mirelis B, Llovet T, Munoz C, Miro E, Navarro F. Antibiotic resistance trends in enteropathogenic bacteria isolated in 1985–1987 and 1995–1998 in Barcelona. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1140–1145. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.5.1140-1145.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rakita R M, Jacques-Palaz K, Murray B E. Intracellular activity of azithromycin against bacterial enteric pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1915–1921. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riley P A, Parasakthi N, Liam C K. Ciprofloxacin- and azithromycin-resistant Campylobacter causing travelers' diarrhea in U.S. troops deployed to Thailand in 1994. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;22:868–869. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.5.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogerie F, Otto D, Vandepitte J, Verbist L, Lemmens P, Habiyaremye I. Comparison of norfloxacin and nalidixic acid for treatment of dysentery caused by Shigella dysenteriae type 1 in adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:883–886. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.5.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe B, Ward L R, Threlfall E J. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhi: a worldwide epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(Suppl. 1):S106–S109. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sack R B, Rhaman M, Yunus M, Khan E H. Antimicrobial resistance in organisms causing diarrheal diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(Suppl. 1):S102–S105. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salam A M, Dhar U, Khan W A, Bennish M L. Randomised comparison of ciprofloxacin suspension and pivmecillinam for childhood shigellosis. Lancet. 1998;15:522–527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11457-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scarpignato C, Rampal P. Prevention and treatment of travelers' diarrhea: a clinical pharmacological approach. Chemotherapy. 1995;41(Suppl. 1):48–81. doi: 10.1159/000239397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith K E, Besser J M, Hedberg C W, Leano F T, Bender J B, Wicklund J H, Johnson B P, Moore K A, Osterholm M T the Investigation Team. Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter jejuni infections in Minnesota, 1992–1998. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1525–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905203402001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steffen R, Collard F, Tornieporth N, Campbell-Forrester S, Ashley D, Thompson S, Mathewson J J, Maes E, Stephenson B, DuPont H L, von Sonnenburg F. Epidemiology, etiology and impact of traveler's diarrhea in Jamaica. JAMA. 1999;281:811–817. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.9.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Threlfall E J, Ward L R, Skinner J A, Smith H R, Lacey S. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella typhi and treatment failure. Lancet. 1999;353:1590–1591. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vila J, Vargas M, Ruiz J, Corachan M, De Anta M T J, Gascon J. Quinolone resistance in enterotoxigenic Esherichia coli causing diarrhea in travelers to India in comparison with other geographical areas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1731–1733. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.6.1731-1733.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vinh H, Wain J, Chinh M T, Tam C T, Tranger P T, Nga D, Echeverria P, Diep T S, White N J, Parry C M. Treatment of bacillary dysentery in Vietnamese children: two doses of ofloxacin versus 5-days nalidixic acid. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94:323–326. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Sonnenburg F, Tornieporth N, Collard F, Waiyaki P, Lowe B, Peruski L F, Jr, Chatterjee S, Costa-Clemens S, Cavalcanti A-M, DuPont H L, Mathewson J J, Steffen R. Risk and etiology of diarrhoea at various tourist destinations. Lancet. 2000;356:133–134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02451-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]