Abstract

Intranasal immunotherapy for Streptococcus pneumoniae invasive pneumonia with polyvalent immunoglobulins (IVIG) was effective in mice against pneumonia but failed to prevent bacteremia. The combination of subcurative doses of IVIG and of ampicillin was fully protective. Such an approach, successfully applied in the preantibiotic era, offers new perspectives for modern therapies.

New therapeutic strategies against pneumococcal diseases are needed due to the multiple resistance to antibiotics of certain strains (8, 15). In the preantibiotic era, antibody-based immunotherapy was effectively used, when pneumococcal infections were treated by serotherapy or combined serum plus chemotherapy (6). Polyvalent human immunoglobulins (IVIG) contain a variety of antimicrobial immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies (3, 9, 14, 18), including antibodies to Streptococcus pneumoniae (12). Experimental pneumonia in leukopenic mice, induced by a serotype 14 S. pneumoniae strain which was avirulent for immunocompetent mice, can be cured by the intranasal administration of IVIG (23). However, the virulence of S. pneumoniae depends not only on the immune status of the host (5, 7, 13) but also on the capsular type of the strain (4). In this study, we evaluated the efficacy of IVIG and a combination therapy with IVIG and ampicillin against a serotype 3 S. pneumoniae strain that is virulent for immunocompetent mice.

Female, 6-week-old BALB/c mice (Charles River Laboratories, Saint Aubin-les-Elbeuf, France) were challenged intranasally, as previously described (23), with S. pneumoniae Pn4241 (2). Inocula were prepared from a 6-h subculture in brain heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C, reaching 109 CFU/ml and diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma, Saint Quentin-Fallavier, France) to a desired density according to the A650 and CFU counts on blood-agar (Biomérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). Statistical analysis of CFU counts in blood and lung homogenates in groups of five mice were performed by using the Student Fisher t test. Lethality for mice was scored each day for 15 days. The mean 50% lethal dose (LD50) of S. pneumoniae Pn4241 for intranasally infected mice was 5 × 103. IVIG (Tégéline [lot 50060432] from the Laboratoire du Fractionnement et des Biotechnologies, Les Ulis, France) was used at the dose of 50 mg/kg throughout the study because this was the highest protective dose tolerated intranasally by the mice. Antibodies to S. pneumoniae in IVIG, either preabsorbed on S. pneumoniae Pn4241 or on the noncapsulated mutant R6 (ATCC 39937) or not, were titrated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously (17, 23). Twofold dilutions (100 to 1 μg/well) in PBS–Tween 20–5% skim milk were added to microtiter plates (Maxisorp Immunoplates; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) coated with 106 heat-killed bacteria. Rabbit anti-human IgG-peroxidase conjugate (Immunotech, Marseille, France) was added and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma) was used for detection. The absorbance (A450) was read with an ELISA reader (Titertek Multiscan; Bioblock, Illkirch, France). Cross-standardization of parallel total IgG and S. pneumoniae antibody titration curves was used to determine the specific antibody titers in each assay (19). Specific S. pneumoniae Pn4241 antibodies accounted for <1% of the total IgG, including 60% ± 6% noncapsular antibodies.

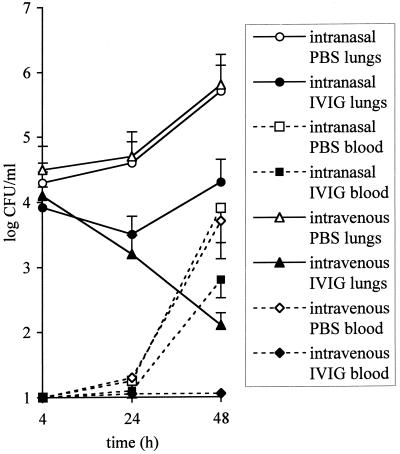

We compared the effects of an intranasal or an intravenous administration of IVIG at 3 h after a challenge with 5 × 104 CFU on bacterial loads in the lungs and the blood. Intravenous injection of IVIG gave effective bacterial clearance from the lungs and prevented bacteremia. Intranasal treatment was transiently effective against pneumonia (P < 0.05), but had no significant effects on bacteremia (P > 0.1), suggesting a short efficacy of locally delivered antibodies (Fig. 1). Intranasal immunotherapy administered 24 h before challenge with 5 × 105 CFU was about 100 times more effective against pneumonia than when given at 3 h after challenge by reducing CFU counts at 48 h from (1.1 ± 0.8) × 104 to (2.1 ± 0.55) × 102 in the lungs (P < 0.01) and from (8.9 ± 4.9) × 101 to (1.3 ± 0.16) × 101 in the blood (P < 0.01). Human IgG in lung or serum samples, collected at 2 h and after 1, 2, 4, and 7 days from intranasally or intravenously treated mice, were titrated by ELISA, as described above. Standard curves were obtained by mixing 1 mg of IVIG with 1 ml of lung cell-free homogenate or with mouse serum. Half of the initial intranasal dose of IgG was cleared from the lungs within 48 h, and no human IgG was detectable in the serum, but half of the intravenous dose was detected in serum after 7 days (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Efficacy of IVIG administered intranasally or intravenously to mice 3 h after intranasal challenge with 5 × 104 CFU of S. pneumoniae Pn4241. The bacterial counts in the lungs and blood are the means ± the standard errors of the mean (vertical bars) for five mice per point treated with PBS or IVIG intranasally or intravenously.

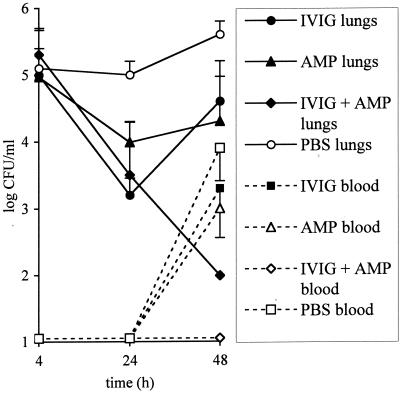

We compared the efficacy of combined therapy with that of single therapy with IVIG or with ampicillin (Sigma) against the ampicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae strain Pn4241 (MIC of 0.016 mg/liter as determined by E-test [AB-Biodisk, Solna, Sweden]). Subcurative doses of ampicillin (200 μg/kg) and of IVIG (10 mg/kg) were selected from preliminary experiments in which mice challenged with 105 or 106 CFU were treated either with ampicillin at 0, 100, 200, or 1,000 μg/kg subcutaneously in a volume of 200 μl at 3 h after infection or intranasally with IVIG at 0, 5, 10, or 50 mg/kg given 24 h before infection because these were the highest doses inducing >10-fold transient reduction in CFU pulmonary counts at 24 h, followed by a regrowth at 48 h, thus mimicking a treatment failure. The efficacy of combined therapy was compared to that of single therapy with ampicillin given at 3 h after challenge (in mice treated intranasally with PBS 24 h before) or with IVIG given 24 h before (and PBS given subcutaneously 3 h after) the challenge. Controls received 50 μl of PBS intranasally 24 h before the challenge and 200 μl subcutaneously at 3 h after the challenge. CFU counts at 48 h in the groups given single treatments were lower but not significantly different from those of the controls (P > 0.1), whereas in the group given both treatments the CFU counts in the lungs and blood were below the threshold of detection (Fig. 2). The survival data were consistent with these results: 9 of 10 mice given the combined treatment survived versus 2 and 3 of the 10 mice in the ampicillin and IVIG single-treatment groups, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Efficacy of combination therapy with ampicillin and intranasal IVIG for treating S. pneumoniae Pn4241 invasive pneumonia. The CFU counts in the lungs and blood are the means ± the standard errors of the mean (vertical bars) for five mice per point (in two independent challenges with 3.2 × 105 and 6.3 × 105 CFU, respectively) treated with PBS, IVIG, or ampicillin plus IVIG. Values below the detection threshold for CFU counts (102 and 101 CFU/ml for the lungs and the blood, respectively) were counted at the threshold value.

Recent advances in immunology have led to renewed interest in passive immunotherapy against infectious agents for which there is no effective treatment, such as with most viruses and multiple-antibiotic-resistant bacteria (6, 18, 27, 28, 29). Topical immunotherapy is a promising approach for epithelial infections (27, 29), particularly for pulmonary infections (22, 23, 24). In this study, intranasal administration of IVIG was effective against pneumonia induced by various lethal pneumococcal inocula of 10 to 1,000 times the LD50 but did not significantly neutralize bacteremia, which is the major threat in pneumococcal infections (13, 20), probably due to the short lifetime of IVIG in the lungs after intranasal administration. Indeed, S. pneumoniae Pn4241 antibody titer in IVIG was low, but an ELISA does not assess antibacterial efficacy which involves not only antibody binding to surface epitopes but also complement activation and opsonophagocytosis (16, 25). Specific S. pneumoniae capsule-type antibody would have been more effective, but the variety of capsular types of S. pneumoniae (>85) requires a polyvalent immunotherapeutic approach such as that developed for vaccines. The development of combinatorial antibody library technology may be the way forward for polyvalent passive immunotherapy against pathogens with antigenic diversity (28).

The combination therapy with IVIG and ampicillin which we tested in a way similar to that applied 60 years ago with immune serum and sulfapyridine (21) and utilized by other investigators more recently (11) was effective for curing invasive pneumonia. Combining antibody-based immunotherapy with chemotherapy may make it possible to achieve effective antibacterial therapy with standard doses of antibiotics for strains with diminished susceptibility, thereby reducing the risk of selection of more resistant variants (8, 15).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the French Ministry of Defense (grant 25149/ETCA/CEB, Department of Biology).

We thank Patrice Courvalin for fruitful discussions and comments on this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso De Velasco E, Verheul A F, Verhoef J, Snippe H. Streptococcus pneumoniae: virulence factors, pathogenesis and vaccines. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:591–603. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.4.591-603.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay-Dupuis E, Bedos J P, Vallée E, Hardy D, Swanson R, Pocidalo J J. Antipneumococcal activity of ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and temafloxacin, in an experimental mouse pneumonia model at various stages of the disease. J Infect Dis. 1990;163:319–324. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkman S A, Lee M L, Gale R P. Clinical use of intravenous immunoglobulins. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:278–292. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-4-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briles D E, Crain M J, Gray B M, Forman C, Yother J. Strong association between capsular type and virulence for mice among human isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1992;60:111–116. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.111-116.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruyn G A, Segers B J, Van Furth R. Mechanisms of host defense against infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:251–262. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casadevall A, Scharff M. Return to the past: the case for antibody-based therapy in infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:150–161. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.1.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crewe-Brown H, Karstaedt A, Saunders G, Khoosal M, Jones N, Klugman A W K. Streptococcus pneumoniae blood culture isolates from patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection: alterations in penicillin susceptibilities and in serogroups or serotypes. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1165–1172. doi: 10.1086/516104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crook D W, Spratt B G. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:595–610. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross A. Intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs) to prevent and treat infectious diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;383:123–130. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1891-4_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.File T, Tan J. Incidence, etiologic pathogens, and diagnostic testing of community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Opin Pulmon Med. 1997;3:89–97. doi: 10.1097/00063198-199703000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer G W, Weisman L E. Therapeutic intervention of clinical sepsis with intravenous immunoglobulin, white blood cells and antibiotics. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1990;73:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamill R J, Musher D, Groover J E, Zavell P J, Watson D A. IgG antibody reactive with five serotypes of S. pneumoniae in commercial intravenous immunoglobulins preparations. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:38–42. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedlund J, Kalin M, Ortqvist A. Recurrence of pneumonia in middle-aged and elderly adults after hospital-treated pneumonia: aetiology and predisposing conditions. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:387–392. doi: 10.3109/00365549709011836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiemstra P S, Brands-Tajouiti J, Van Furth R. Comparison of antibody activity against various microorganisms in intravenous immunoglobulin preparations determined by ELISA and opsonic assay. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;123:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs M R. Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: rational antibiotic choices. Am J Med. 1999;106:19S–25S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson S E, Rubin L, Romero-Stainer S, Dykes J K, Pais L B, Rizvi A, Ades E, Carlone G M. Correlation of opsonophagocytosis and passive protection assays using human anticapsular antibodies in an infant mouse model of bacteremia for Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:133–140. doi: 10.1086/314845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musher D M, Luchi M J, Watson D A, Hamilton R, Baughn R E. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in young adults and older bronchitics: determination of IgG responses by ELISA and the effect of adsorption of serum with non type-specific cell wall polysaccharide. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:728–735. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennington J E. Newer uses of intravenous immunoglobulins as anti-infective agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1463–1466. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.8.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plikaytis B D, Holder P F, Pais L B, Maslanka S E, Gheesling L L, Carlone G M. Determination of parallelism and nonparallelism in bioassay dilution curves. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2441–2477. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.10.2441-2447.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plouffe J F, Breiman R F, Facklam R R. Bacteremia with Streptococcus pneumoniae. JAMA. 1996;275:194–198. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.3.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell H, Jamieson W. Combined therapy of pneumococci rat infections with rabbit antipneumococcic serum and sulfapyridine (2-sulfanil aminopyridine) J Immunol. 1939;36:459–465. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramisse F, Szatanik M, Binder P, Alonso J M. Passive local immunotherapy of experimental staphylococcal pneumonia with human intravenous immunoglobulins. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1030–1033. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramisse F, Binder P, Szatanik M, Alonso J M. Passive and active immunotherapy of experimental pneumococcal pneumonia by polyvalent human immunoglobulins or F(ab′)2 fragments administered intranasally. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1123–1128. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramisse F, Deramoudt F X, Szatanik M, Bianchi A, Binder P, Hannoun C, Alonso J M. Effective prophylaxis of influenza A virus pneumonia in mice by topical passive immunotherapy with polyvalent human immunoglobulins or F(ab′)2 fragments. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:583–587. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00538.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stack A M, Malley R, Thompson C M, Kobzik L, Siber G R, Saladino R A. Minimum protective serum concentrations of pneumococcal anti-capsular antibodies in infant rats. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:986–990. doi: 10.1086/515259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuomanen E I, Masure H R. Molecular and cellular biology of pneumococcal infection. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:297–308. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weltzin R, Monath T P. Intranasal antibody prophylaxis for protection against viral disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:383–393. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.3.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winter G, Griffiths A, Hawkins R, Hoogenboom H. Making antibodies by phage display technology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:433–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeitlin L, Cone R A, Whaley J K. Using monoclonal antibodies to prevent mucosal transmission of epidemic infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:54–64. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]