Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolate BM4455 was resistant to 16-membered macrolides and to streptogramins. This unusual resistance phenotype was due to an A2062C (Escherichia coli numbering) mutation in domain V of the four copies of 23S rRNA.

Macrolide and lincosamide antibiotics exhibit high activity against streptococci and are among the drugs that can be used for the treatment of infections due to Streptococcus pneumoniae (10). The macrolides are largely prescribed for empiric therapy of community-acquired respiratory tract infections and may be useful in case of intolerance or resistance to β-lactams. In France, oral streptogramins are the second line treatment in the macrolide, lincosamide, streptogramin (MLS) group of antibiotics, in which they replace erythromycin and related macrolides in case of resistance of S. pneumoniae to macrolides (11). The streptogramin antibiotics produced by Streptomyces pristinaespiralis contain two active components, A and B (II and I in pristinamycin, M and S in virginiamycin, and the semisynthetic derivatives dalfopristin and quinupristin in Synercid), that inhibit peptide elongation synergistically; individually they are bacteriostatic, whereas together they can be bacteriocidal. The presence of the A component strongly enhances ribosomal binding of the B component (19). The prevalence of macrolide-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae has increased during the last 10 years (17, 22). There is, thus, a need for alternative drugs. The ketolides, such as telithromycin, constitute a new semisynthetic 14-membered macrolide class of antimicrobial agents (8). Telithromycin is a 3-keto derivative of clarithromycin. The ketolides have the same antibacterial spectrum as macrolides but also display good activity against erythromycin-resistant isolates of gram-positive cocci (8).

The macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin B antibiotics (MLSB) are three chemically distinct but functionally related drug classes. They act by binding to the 50S subunit of bacterial ribosomes and inhibit protein synthesis by blocking elongation of the nascent peptide chain (2, 10).

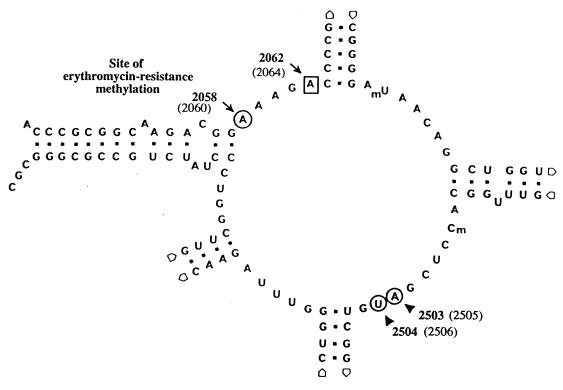

Resistance to macrolides in S. pneumoniae is due to two mechanisms: target site modification or active efflux. Target modification is secondary to acquisition of an erm gene which encodes an enzyme that methylates a specific adenine residue (A2058) in 23S rRNA (Fig. 1) (10). This alteration induces a conformational change in the 50S ribosomal subunit that blocks binding of the MLSB to the ribosome (10). Expression of resistance can be inducible or constitutive. Streptococci, as opposed to staphylococci, are cross-resistant to 14-, 15-, and 16-membered MLSB whether resistance is inducible or constitutive. Streptogramins A are not affected, and synergy between the two components of streptogramins against MLSB-resistant strains is maintained. Thus, in streptococci, constitutive resistance cannot be distinguished from inducible resistance on the sole basis of elevated MICs of erythromycin and lincomycin (21). The high prevalence of the MLSB-inducible phenotype in S. pneumoniae explains why weak inducers like the ketolides are active against most of the isolates of this species.

FIG. 1.

Secondary structure of the peptidyl transferase loop in domain V of 23S rRNA. The mutated position in S. pneumoniae BM4455 is indicated by a square. The positions of the other binding sites of streptogramins (m2A2503-U2504) are indicated by a circle. Nucleotide sequence and numbering are those of E. coli 23S rRNA, and the corresponding S. pneumoniae numbering is given in parentheses.

The second resistance mechanism, macrolide-specific efflux from the cells, is effected by a membrane protein encoded by the mef gene (25). This leads to the M phenotype, which is resistance to 14- and 15-membered macrolides and susceptibility to 16-membered macrolides, ketolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins. The mef gene is the most common macrolide resistance determinant among S. pneumoniae isolates in the United States, whereas erm is more prevalent in Europe (17, 22).

Recently, two other mechanisms associated with unusual resistance phenotypes to MLS antibiotics have been identified in clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae. Macrolide-streptogramin resistance is due to a 3-amino-acid substitution, whereas further resistance to ketolides is due to a 6-amino-acid insertion in a highly conserved region of ribosomal protein L4 (63KPWRQKGTGRAR74 [S. pneumoniae numbering]) (A. Tait-Kamradt, T. Davies, L. Brennan, F. Depardieu, P. Courvalin, J. Duignan, J. Petitpas, L. Wondrack, M. Jacobs, P. Appelbaum, and J. Sutcliffe, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. LB-8, 1999). The macrolide-lincosamide resistance phenotype observed in clinical isolates from the United States or in laboratory mutants is due to an A2059G (Escherichia coli numbering) change in two, three, or four copies of 23S rRNA (26). A gene dosage effect on the level of macrolide and lincosamide resistance was observed in isogenic strains depending upon the number of mutated rrl alleles.

S. pneumoniae BM4455, of capsular serovar 18F, was isolated in 1988 in France from a blood culture (6) and had a new resistance phenotype (Table 1). There was a dissociation between resistance to 16-membered macrolides and susceptibility to 14- and 15-membered macrolides associated with resistance to the two components of streptogramins. The MICs of certain MLS antibiotics for S. pneumoniae BM4455 and susceptible S. pneumoniae BM4203 and CP1000 (Table 1) were determined by agar dilution in Mueller-Hinton medium supplemented with 5% horse blood with an inoculum of 104 CFU per spot (Table 2) (3). Strain BM4455 was resistant to high levels of 16-membered macrolides and to intermediate levels of streptogramins A and B, but synergy between the two components was retained. The strain remained susceptible to the 14- and 15-membered macrolides, the ketolides, and the lincosamides.

TABLE 1.

Strains of S. pneumoniae studied

| Strain | Resistance phenotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| BM4203 | Susceptible | 27 |

| CP1000 | Smr | 15 |

| BM4455 | M16r SAr SBr Sr | 6 |

| BM4456 | Smr M16r SAr SBr Sr | Transformation of BM4455 total DNA into CP1000 |

| BM4457 | Smr M16r SAr SBr Sr | Transformation of BM4455 rrl gene into CP1000 |

Abbreviations: M16, 16-membered macrolides; SA, pristinamycin II; SB, pristinamycin I; S, pristinamycin I and II; Sm, streptomycin.

TABLE 2.

MICs of antibiotics against S. pneumoniae strainsa

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml) ofb:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrolidesc

|

Lincosamides

|

Streptogramins

|

||||||||||

| ERY (14) | AZI (15) | SPI (16) | JOS (16) | TYL (16) | TEL (14) | LIN | CLI | SB | SA | S | QUI + DAL | |

| BM4203 | <0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | <0.0075 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 2 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| CP1000 | <0.25 | <0.125 | <0.125 | 0.125 | <0.25 | <0.0075 | 0.5 | 0.03 | 1 | <2 | <0.0625 | 0.25 |

| BM4455 | <0.25 | 0.5 | 512 | 64 | 64 | <0.0075 | 0.5 | <0.015 | 32 | 16 | 2 | 2 |

| BM4456 | <0.25 | 0.5 | 512 | 32 | 32 | <0.0075 | 0.5 | <0.015 | 64 | 32 | 4 | 2 |

| BM4457 | <0.25 | 0.5 | 512 | 32 | 32 | <0.0075 | 0.5 | <0.015 | 64 | 32 | 4 | 2 |

The MICs were determined by the agar dilution method after 24 h at 37°C in an atmosphere enriched with 5% CO2.

Abbreviations: AZI, azithromycin; ERY, erythromycin; CLI, clindamycin; JOS, josamycin; LIN, lincomycin; QUI + DAL, 30% quinupristin–70% dalfopristin; SA, pristinamycin II; SB, pristinamycin I; S, pristinamycin I and II; SPI, spiramycin; TEL, telithromycin; TYL, tylosin.

Numbers in parentheses are numbers of ring members.

S. pneumoniae BM4455 was tested for the presence of known MLS resistance determinants. Attempts to amplify genomic DNA using primers specific for ermA, ermB, and ermC genes encoding an rRNA methylase; ereA and ereB specifying a macrolide esterase; mphA and mphB macrolide phosphotransferases; msrA, an ATP binding cassette-type transporter; and mefA, a proton-motive force macrolide transporter (24), were unsuccessful (data not shown).

The possibility that strain BM4455 carried mutations in ribosomal proteins L4, L16, or L22 or in 23S rRNA was explored. Ribosomal proteins L4 and L22 are involved in the binding of spiramycin to the 50S subunit of the ribosome (1, 7, 31). Proteins L16 and L22 interact with the streptogramins (4, 5). L4 and L22 bind primarily to domain I of 23S rRNA, but erythromycin resistance mutations in these proteins perturb the conformation of residues in domains II, III, and V and thereby affect the action of antibiotics known to interact with nucleotide residues in the peptidyl transferase center of domain V (7). Mutations conferring resistance to macrolides were first identified in proteins L4 and L22 of E. coli (18, 31) and subsequently in 23S rRNA (30). There is compelling evidence that the peptidyltransferase loop in domain V of 23S rRNA may contain at least part of the site at which the MLS antibiotics physically bind to the ribosome (14, 19, 30). Mutants selected for resistance to individual MLS antibiotics show changes in A2058 (E. coli numbering) and neighboring nucleotides, suggesting their involvement in the binding of these antibiotics (30).

The primers used to amplify the entire structural genes rplD, rplP, and rplV for ribosomal proteins L4, L16, and L22, respectively, and of part of rrl for domains II and V of 23S rRNA were designed complementary to conserved regions (Table 3). Amplifications were performed with total DNA of strain BM4455 as a template using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) in a DNA Thermal Cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) for 30 cycles. The conditions were 1 min at 95°C for denaturation, 1 min at 50°C (rplD, rplP, rplV, and rrl for domain II) or at 54°C (four alleles of rrl corresponding to domain V) for annealing, and 2 min at 72°C for elongation. The amplification products were purified, cloned into pCR-Blunt vector (Invitrogen), and sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method using T7 DNA polymerase (T7 Sequencing kit; Pharmacia) and [α-35S]-dATP (Amersham Radiochemical Centre). The sequences obtained were compared with those of S. pneumoniae obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR)'s Website (http://www.tigr.org.). No mutations were observed in the rplP and rplV genes, whereas the sequence of rplD for L4 differed by a point mutation in codon 20, leading to a Ser-to-Asn substitution (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Oligodeoxynucleotides used and mutations in S. pneumoniae strains

| Gene (ribosomal protein) template for amplification | Primer

|

Positionb | Product size (bp) | Reference or source | Mutation (amino acid substitution) in strain:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a | CP1000 | BM4455 | BM4456 | BM4457 | ||||

| rplD (L4) | L4 NH2 | + GTGCACGAGTGTCAACT | 1337–1353 | 855 | This study | None | AGC→AAC | None | None |

| L4 COOH | − GTTGTACAAGTTGTTCC | 499–515 | (Ser20-Asn) | ||||||

| rplP (L16) | L16 NH2 | + AGTATGGATCTACCGTG | 2177–2193 | 551 | This study | None | None | None | None |

| L16 COOH | − CGCGAGTTCTTCTTGAG | 2713–2729 | |||||||

| rplV (L22) | L22 NH2 | + TGCACCAACTCGTACTT | 1155–1171 | 479 | This study | None | None | None | None |

| L22 COOH | − TCACGGATGATGCCGAC | 1617–1633 | |||||||

| rrl (23S rRNA) | |||||||||

| Domain II | 23S rRNA-II+ | + CTCCCTAGTGACCGATA | 465–481 | 865 | This study | None | None | None | None |

| 23S rRNA-II− | − TACGGTGGACAGGATTC | 1312–1328 | |||||||

| Domain V | 23S rRNA-V+ | + TCAGCCGCAGTGAATAG | 1749–1765 | This study | |||||

| DS18 | − GCCAGCTGAGCTACACCGCC | 2,002 | 26 | None | A2062C | A2062C | A2062C | ||

| DS23 | − TACACACTCACATATCTCTG | 2,004 | 26 | None | A2062C | A2062C | A2062C | ||

| DS30 | − TTTTACCACTAAACTACACC | 1,296 | 26 | None | A2062C | A2062C | A2062C | ||

| DS91 | − TACCAACTGAGCTATGGCGG | 1,217 | 26 | None | A2062C | A2062C | A2062C | ||

+, sense primer; −, antisense primer.

For the rplD gene, positions were determined from the sp19 contig as found on TIGR's Website (http://www.tigr.org); for the rplP and rplV genes, positions are according to the sequence of S. pneumoniae R6 (accession number AF126059); for domains II and V of the rrl gene, positions are according to the S. pneumoniae numbering obtained from the sp23 contig in TIGR's Website and aligned on the E. coli rrl gene sequence.

Four copies of the 23S rRNA rrl gene are present in S. pneumoniae, and a strategy has been developed to amplify these copies individually for domain V (26). It consists in using primers complementary to unique sequences downstream from each rrl gene and a primer (23S rRNA-V+) common to the four alleles and complementary to a region upstream from the peptidyl transferase region in domain V (Table 3). The four rrl genes were amplified separately, the region encoding domain V was sequenced, and each copy was found to contain an A2062C (E. coli numbering) substitution. No mutations were observed in the rrl portion corresponding to domain II.

To determine if the mutations in the rplD gene for ribosomal protein L4 and in the portion of rrl corresponding to domain V of 23S rRNA were necessary and sufficient to confer the 16-membered macrolide–streptogramin (M16-S) resistance phenotype to the host, total DNA from strain BM4455 or the PCR products corresponding to the rplD gene and domain V of the rrl gene were introduced into S. pneumoniae CP1000 by transformation (Table 1). Chromosomal or amplified DNA was added to competent cells of CP1000, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C until the optical density at 550 nm reached 0.2. The bacteria were then plated onto horse blood agar and incubated at 37°C for 2 h without antibiotic. Transformants were selected with spiramycin at 10 μg/ml and 60 μg/ml or pristinamycin at 1 μg/ml by the overlay procedure and incubated 24 to 48 h at 37°C in an atmosphere enriched with 5% CO2. Transformants were obtained only with chromosomal DNA or with the 1,013-bp rrl PCR fragment of domain V containing the A2062C mutation and on spiramycin (10 μg/ml). Their phenotype was indistinguishable from that of the donor strain BM4455 (Table 1). Experiments performed with the 855-bp rplD PCR product containing the G-to-A substitution at position 59 (Table 3) did not yield any transformant. The four rrl alleles corresponding to domain V and the rplD gene of transformants BM4456 and BM4457 obtained with total DNA or the rrl PCR product of domain V (Table 1), respectively, were amplified and sequenced as described above. The two transformants were found to harbor the same A2062C mutation in the four rrl copies as in the donor but not the substitution in the rplD gene for ribosomal protein L4 (Table 3). The MICs of various MLS antibiotics against the transformants were determined and found to be similar to those against the wild strain (Table 2). Taken together these data indicate that the mutation in the four rrl genes corresponding to domain V is solely responsible for resistance to 16-membered macrolides and to streptogramins. Gene conversion could be responsible for the presence of the A2062C mutation in the four rrl copies (9).

To the best of our knowledge, a single example of mutation at position 2062 of 23S rRNA has been reported. A chloramphenicol-resistant mutant was isolated in Halobacterium halobium, which possesses a single copy of 23S rRNA, that contained an A-to-C substitution at position 2062 (E. coli numbering) in domain V (13). The target site for macrolides lies within 23S rRNA at the peptidyltransferase center of the 50S subunit (Fig. 1). The peptidyltransferase activity is associated with the central loop of domain V, where macrolides make several contacts with the rRNA (14). Recently, the binding sites of streptogramins B in E. coli were localized by UV-induced modifications at positions A2503-U2504 and G2061-A2062 in the peptidyltransferase loop (Fig. 1) (19, 20). Mutation at position 2062 of 23S rRNA may therefore prevent binding of pristinamycin I and account for resistance in strain BM4455 (Fig. 1).

Mutations at A2058 presumably perturb the site were the MLS drugs interact with the ribosome and thereby affect their binding in a manner similar to methylation at this position (23). In Helicobacter pylori, clarithromycin resistance is due to mutations at position 2058 or 2059 in the 23S rRNA (28). Mutations at position 2058 confer an MLSB phenotype with high-level clarithromycin resistance, an A-to-G substitution being the most common in clinical isolates (29). Mutations at position 2059 confer a lower level of resistance to clarithromycin and no resistance to the streptogramins (16). Mycoplasma pneumoniae displays phenotypes similar to those of H. pylori following A2058G and A2059G mutations, and it has been shown that the G2059 mutant is more resistant to 16-membered macrolides such as tylosin and spiramycin (12). These results could reflect subtle differences in the mode of interaction of 14- and 16-membered macrolides in the 2058 region of 23S rRNA (14). Erythromycin-resistant mutants that remain susceptible to spiramycin also support the notion that the ribosome binding sites for the two groups of macrolides are not identical (1). In addition, the drugs with 16 atoms are much larger than those with 14 atoms, and the number of sugar residues also differs. Together these observations could explain the dissociated resistance between 16- or 14- and 15-membered macrolides.

In conclusion, we have shown that an A2062C mutation in 23S rRNA confers M16-S resistance in S. pneumoniae. With the emergence of new resistance mechanisms, it seems advisable to test in vitro the activity of one member each of the 14-, 15-, and 16-membered macrolide, ketolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin class of drugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Bristol-Myers Squibb Unrestricted Biomedical Research Grant in Infectious Diseases.

We thank R. Carnahan for having initiated this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arevalo M A, Tejedor F, Polo F, Ballesta J P. Protein components of the erythromycin binding site in bacterial ribosomes. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brisson-Noel A, Trieu-Cuot P, Courvalin P. Mechanism of action of spiramycin and other macrolides. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;22(Suppl. B):13–23. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comité de l'Antibiogramme de la Société Française de Microbiologie. Zone sizes and breakpoints for non-fastidious organisms. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;2(Suppl.):1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bethune M P, Nierhaus K H. Characterisation of the binding of virginiamycin S to Escherichia coli ribosomes. Eur J Biochem. 1978;86:187–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Giambattista M, Chinali G, Cocito C. The molecular basis of the inhibitory activities of type A and type B synergimycins and related antibiotics on ribosomes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;24:485–507. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emond J P, Fremaux A, Dublanchet A, Sissia G, Geslin P, Sedalian A, Lionsquy G. Resistance of two strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae to pristinamycin associated with 16-membered macrolides. Pathol Biol. 1989;37:791–792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gregory S T, Dahlberg A E. Erythromycin resistance mutations in ribosomal proteins L22 and L4 perturb the higher order structure of 23 S ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:827–834. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones R N, Biedenbach D J. Antimicrobial activity of RU-66647, a new ketolide. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;27:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(96)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi I. Mechanisms for gene conversion and homologous recombination: the double-strand break repair model and the successive half crossing-over model. Adv Biophys. 1992;28:81–133. doi: 10.1016/0065-227x(92)90023-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1267–1272. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.7.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leclercq R, Courvalin P. Streptogramins: an answer to antibiotic resistance in gram-positive bacteria. Lancet. 1998;352:591–592. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucier T S, Heitzman K, Liu S K, Hu P C. Transition mutations in the 23S rRNA of erythromycin-resistant isolates of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2770–2773. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mankin A S, Garrett R A. Chloramphenicol resistance mutations in the single 23S rRNA gene of the archaeon Halobacterium halobium. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3559–3563. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.11.3559-3563.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moazed D, Noller H F. Chloramphenicol, erythromycin, carbomycin and vernamycin B protect overlapping sites in the peptidyl transferase region of 23S ribosomal RNA. Biochimie. 1987;69:879–884. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(87)90215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison D A, Trombe M C, Hayden M K, Waszak G A, Chen J D. Isolation of transformation-deficient Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants defective in control of competence, using insertion-duplication mutagenesis with the erythromycin resistance determinant of pAMb1. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:870–876. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.3.870-876.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Occhialini A, Urdaci M, Doucet-Populaire F, Bebear C M, Lamouliatte H, Megraud F. Macrolide resistance in Helicobacter pylori: rapid detection of point mutations and assays of macrolide binding to ribosomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2724–2728. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.12.2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oster P, Zanchi A, Cresti S, Lattanzi M, Montagnani F, Cellesi C, Rossolini G M. Patterns of macrolide resistance determinants among community-acquired Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates over a 5-year period of decreased macrolide susceptibility rates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2510–2512. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.10.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pardo D, Rosset R. Properties of ribosomes from erythromycin resistant mutants of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;156:267–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00267181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porse B T, Garrett R A. Sites of interaction of streptogramin A and B antibiotics in the peptidyl transferase loop of 23 S rRNA and the synergism of their inhibitory mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 1999;286:375–387. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porse B T, Kirillov S V, Awayez M J, Garrett R A. UV-induced modifications in the peptidyl transferase loop of 23S rRNA dependent on binding of the streptogramin B antibiotic, pristinamycin IA. RNA. 1999;5:585–595. doi: 10.1017/s135583829998202x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosato A, Vicarini H, Leclercq R. Inducible or constitutive expression of resistance in clinical isolates of streptococci and enterococci cross-resistant to erythromycin and lincomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:559–562. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shortridge V D, Doern G V, Brueggemann A B, Beyer J M, Flamm R K. Prevalence of macrolide resistance mechanisms in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates from a multicenter antibiotic resistance surveillance study conducted in the United States in 1994–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1186–1188. doi: 10.1086/313452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigmund C D, Ettayebi M, Morgan E A. Antibiotic resistance mutations in 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA genes of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:4653–4663. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.11.4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tait-Kamradt A, Clancy J, Cronan M, Dib-Hajj F, Wondrack L, Yuan W, Sutcliffe J. mefE is necessary for the erythromycin-resistant M phenotype in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2251–2255. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tait-Kamradt A, Davies T, Cronan M, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C, Sutcliffe J. Mutations in 23S rRNA and ribosomal protein L4 account for resistance in pneumococcal strains selected in vitro by macrolide passage. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2118–2125. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2118-2125.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tankovic J, Perichon B, Duval J, Courvalin P. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2505–2510. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Versalovic J, Shortridge D, Kibler K, Griffy M V, Beyer J, Flamm R K, Tanaka S K, Graham D Y, Go M F. Mutations in 23S rRNA are associated with clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:477–480. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang G, Taylor D E. Site-specific mutations in the 23S rRNA gene of Helicobacter pylori confer two types of resistance to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1952–1958. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisblum B. Erythromycin resistance by ribosome modification. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:577–585. doi: 10.1128/AAC.39.3.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittmann H G, Stoffler G, Apirion D, Rosen L, Tanaka K, Tamaki M, Takata R, Dekio S, Otaka E. Biochemical and genetic studies on two different types of erythromycin resistant mutants of Escherichia coli with altered ribosomal proteins. Mol Gen Genet. 1973;127:175–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00333665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]