Glycopeptide antibiotics vancomycin and teicoplanin inhibit cell wall synthesis by forming complexes with the peptidyl-d-alanyl–d-alanine (d-Ala–d-Ala) termini of peptidoglycan precursors at the cell surface (33). Acquired resistance to these antibiotics is mostly due to two types of gene clusters, designated vanA and vanB, that confer resistance by the same mechanism and encode related enzymes (Fig. 1) (10). In both cases, resistance is due to synthesis of peptidoglycan precursors ending in the depsipeptide d-alanyl–d-lactate (d-Ala–d-Lac) that bind to glycopeptides with reduced affinity (15, 17). The vanA and vanB clusters comprise three genes (vanHAX and vanHBBXB) that are necessary and sufficient for resistance (9) and appear to originate from glycopeptide-producing bacteria (32). These genes encode a dehydrogenase (VanH or VanHB) that reduces pyruvate into d-Lac, a ligase (VanA or VanB) that synthesizes d-Ala–d-Lac, and a d,d-dipeptidase (VanX or VanXB) that hydrolyzes d-Ala–d-Ala. The combined action of these three enzymes results in incorporation of d-Ala–d-Lac instead of d-Ala–d-Ala into peptidoglycan precursors (8). In addition, the vanA and vanB clusters encode a d,d-carboxypeptidase (VanY or VanYB) that contributes to glycopeptide resistance by cleaving the C-terminal d-Ala of late membrane-bound peptidoglycan precursors (3). The latter precursors originate from incomplete hydrolysis of d-Ala–d-Ala by the VanX or VanXB d,d-dipeptidases (34). Finally, the vanA and vanB clusters also contain two genes of unknown function (vanZ and vanW, respectively) that do not have significant sequence similarity to previously sequenced genes or to each other (17). The VanZ protein was found to confer low-level resistance to teicoplanin only (6), whereas the role of VanW in resistance has not been investigated.

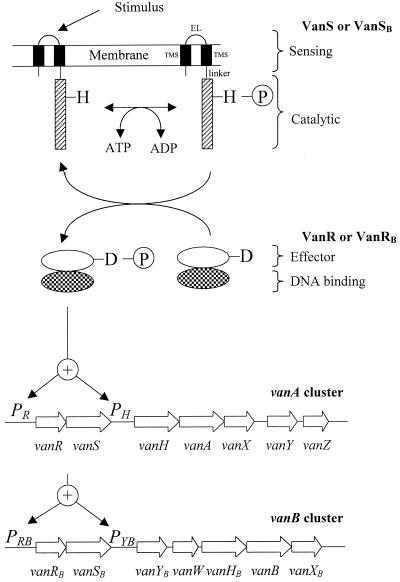

FIG. 1.

Events leading to transcriptional activation of the vanA and vanB gene clusters. The Van sensors contain two trans-membrane segments (TMS) that delineate an external loop (EL). The sequence of these regions of VanS and VanSB are not related, as is found for sensors that recognize different signals (25). A linker connects the membrane-associated domain to the catalytic cytoplasmic domain (hatched). The catalytic domain is conserved in all sensors and contains a conserved histidine residue (H) which is autophosphorylated. The phosphoryl group (P) is then transferred to an aspartate residue (D) of the effector domain of VanR or VanRB. The effector domain is also conserved in all response regulators (25). Phosphorylation of the effector domain activates the DNA binding domain leading to increased affinity for the regulatory regions of the target promoters. The DNA binding domains of VanR and VanRB are related to those of response regulators belonging to the OmpR subfamily (25).

Expression of the resistance genes of the vanA and vanB clusters is regulated by the VanRS and VanRBSB two-component regulatory systems, each composed of a membrane-associated sensor kinase (VanS or VanSB) and a cytoplasmic response regulator (VanR or VanRB) that acts as a transcriptional activator (Fig. 1) (9, 17). The regulatory and resistance genes are transcribed from distinct promoters that appear to be coordinately regulated. Namely, the VanRS regulatory system controls transcription of the vanRS and vanHAXYZ operons at the PR and PH promoters (5). Likewise, the VanRBSB system controls transcription of the vanRBSB and vanYBWHBBXB operons at the PRB and PYB promoters (17, 35). The present review is focused on how the regulation of these promoters determines inducible expression of VanA- and VanB-type glycopeptide resistance. Background information on regulation of bacterial genes by two-component regulatory systems can be found elsewhere (25).

OVERVIEW OF EVENTS THAT LEAD TO INDUCTION OF RESISTANCE

The membrane-associated domains of VanS and VanSB are thought to sense the presence of glycopeptides in the culture medium by an unknown mechanism (Fig. 1). The signal is transduced to the cytoplasmic catalytic domain of the sensors, leading to kinase stimulation, autophosphorylation of a specific histidine residue, and transfer of the phosphoryl group to a specific aspartate residue of the partner response regulators. The phosphorylated regulators bind to the regulatory region of the target promoters, resulting in transcriptional activation of the regulatory and resistance genes. Ultimately, induction brings about a switch from synthesis of precursors ending in d-Ala–d-Ala to precursors ending in d-Ala–d-Lac.

INDIVIDUAL COMPONENTS OF SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION PATHWAY IN VANA-TYPE ENTEROCOCCI

Phosphotransfer reactions catalyzed by VanS and VanR in vitro.

VanR and the cytoplasmic kinase domain of VanS fused to the maltose binding protein have been overerproduced in Escherichia coli, purified, and assayed for phosphotransfer reactions (40). VanS was found to catalyze ATP-dependent autophosphorylation of a histidine residue. Upon addition of VanR, the phosphoryl group was transferred from the phosphohistidine residue of VanS to an aspartate residue of the response regulator. In the absence of VanS, dephosphorylation of the phosphorylated form of VanR (phospho-VanR) was extremely slow compared to that of related response regulators, with a half-life of 10 h. VanS stimulated this reaction, indicating that the sensor has a so-called phosphatase activity.

Phospho-VanS was also shown to transfer its phosphoryl group to the PhoB response regulator of the E. coli Pho regulon (phosphorus assimilation) (18). Kinetic comparison revealed a 104-fold preference for phosphotransfer to VanR compared to PhoB (19). Nonetheless, VanS was able to activate PhoB in vivo, leading to a 500-fold increase in transcription from a PhoB-activated promoter (18). Finally, VanR catalyzes its own phosphorylation in the absence of any kinase by using acetyl-phosphate as a substrate (26).

In vitro binding of VanR to the regulatory region of PR and PH promoters.

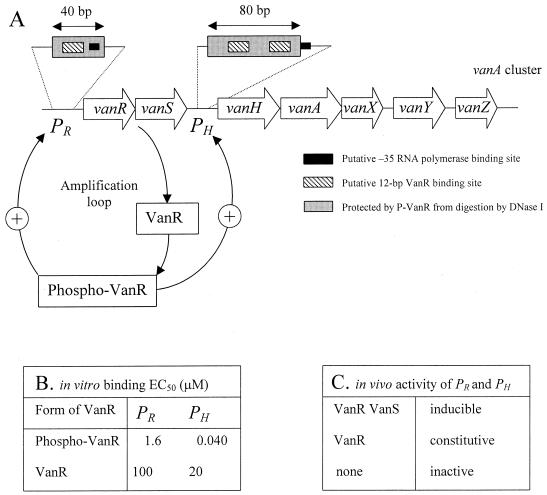

VanR and phospho-VanR bind to a similar 80-bp region of the regulatory region of the PH promoter that contains two putative 12-bp VanR-binding sites (26) (Fig. 2A). The PR promoter contains a single 12-bp binding site, and phosphorylation of VanR increases the size of the protected region from 20 to 40 bp. Phosphorylation of VanR increases the affinity of the response regulator for both promoters (Fig. 2B). The affinity is higher for PH than for PR, and the difference is more important for phospho-VanR than for VanR. These observations suggest that phospho-VanR may cooperatively bind to the PH promoter.

FIG. 2.

Regulation of the PR and PH promoters. (A) Schematic representation of the vanA gene cluster showing details of the regulatory region of PR and PH. An amplification loop results from binding of phospho-VanR to PR, increased transcription of vanR, and accumulation of phospho-VanR following phosphorylation (4). (B) Determination of the effective concentrations of phospho-VanR and VanR required to saturate at 50% (EC50) DNA fragments carrying the PR and PH promoters based on gel shift experiments indicated that phosphorylation increases the affinity of the response regulator for DNA at both promoters and that the affinity is higher for PH than for PR (26). In spite of these differences, the PR and PH promoters were found to be coordinately regulated in vivo (C) and to have a similar strength (5).

In vivo activation of the PR and PH promoters in Enterococcus faecalis.

Activation of the PH and PR promoters has been studied using various types of transcriptional fusions with reporter genes. Parallel determinations of d,d-dipeptidase activity and of the cytoplasmic pool of peptidoglycan precursors showed that expression of glycopeptide resistance is mainly, if not exclusively, regulated at the level of transcriptional initiation at these promoters (8). The PH and PR promoters were found to have a similar strength and to be similarly regulated (Fig. 2C) (5). The promoters are inactive in the absence of VanR and VanS, constitutively activated by VanR in the absence of VanS, and inducible by glycopeptides if the host produces both VanR and VanS. These results indicate that VanR is a transcriptional activator required for initiation at both promoters. VanS is not necessary for full activation of the promoters, because VanR can be activated (phosphorylated) independently from its partner sensor, presumably by a heterologous kinase encoded by the host chromosome. In contrast, VanS is required for negative control of the promoters in the absence of glycopeptides. The sensor is therefore thought to act as a phosphatase under noninducing conditions, preventing accumulation of phospho-VanR.

In vivo evidence for phosphatase activity of VanS.

Sensor kinases of two-component regulatory systems display a highly conserved amino acid motif, called the H box, that contains the phosphorylated histidine residue (Fig. 1) (25). Replacement of this histidine by glutamine abolishes autophosphorylation of the sensors and, consequently, transfer of phosphoryl groups to the response regulators (27). However, the modified sensors retain phosphatase activity. Production of VanSH164Q, i.e., VanS which carries a histidine (H)-to-glutamine (Q) substitution at the putative autophosphorylation site (position 164), prevented transcriptional activation in the absence of glycopeptides, indicating that the protein was acting as a phosphatase (Table 1) (4). VanSH164Q also prevented transcription of the resistance genes in the presence of glycopeptides, suggesting that the phosphatase activity of this protein was not negatively modulated by the antibiotics. Negative control of VanR by VanS164Q confirmed that the phosphorylated form of the response regulator is responsible for transcriptional activation.

TABLE 1.

Phenotype associated with alterations of VanS and VanSB functions in E. faecalis

| Function alteration and allele (cluster) | Expression of resistance genes |

|---|---|

| None | |

| Wild-type vanS (vanA) | Inducible by VAN, TEC, and MOEa |

| Wild-type vanSB (vanB) | Inducible by VAN |

| Loss of all functions | |

| Null allele of vanS (vanA) | Constitutive (inducible by VAN, TEC, and MOE if PH titrates phospho-VanR) |

| Null allele of vanSB (vanB) | Clonal variation, inducible by VAN, TEC, and MOE |

| Loss of kinase activity due to substitutions at autophosphorylation site | |

| vanS H164Q (vanA) | Repressed under all conditions |

| vanSB H233Q (vanB) | Inducible by VAN |

| Alteration of signal recognition or transduction due to substitution in sensing domainb | |

| vanSB A30G (vanB) | Inducible by VAN and TEC |

| vanSB D168Y (vanB) | Inducible by VAN and TEC |

| Impaired phosphatase activity due to substitutions in H box | |

| vanSB S232Y (vanB) | Constitutive |

| vanSB Y237M or K (vanB) | Constitutive |

MOE, moenomycin; TEC, teicoplanin; VAN, vancomycin.

The substitutions were located in the external loop (e.g., A30G) or in the linker (e.g., D168Y) of VanSB.

Amplification of signal.

As indicated above, phospho-VanR binds to the PR promoter and activates transcription of the vanR and vanS genes. Thus, regulation of the vanA gene cluster involves not only a modulation of the relative concentration of VanR and phospho-VanR by the kinase and phosphatase activities of VanS but also a modulation of the absolute concentration of the response regulator (4, 5). An amplification loop results from binding of phospho-VanR to the PR promoter, increased expression of vanR, and accumulation of phospho-VanR following phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). This may account for the high-level transcription of the resistance genes observed in vanS null mutants, since the amplification loop, in combination with the long half-life of phospho-VanR, may compensate for inefficient phosphorylation of the response regulator by the putative host kinase (5).

Disruption of the amplification loop was obtained in a vanS null mutant by introducing a multicopy plasmid carrying the PH promoter (4). Introduction of the plasmid prevented transcription of the resistance genes in the absence of glycopeptides, indicating that the high-affinity VanR binding sites of PH titrated phospho-VanR, thereby preventing the activation of PR. Expression of the resistance genes was inducible by glycopeptides, suggesting that stimulation of a putative host kinase by these antibiotics can compensate for titration of phospho-VanR (4). This surprising result implies that the chromosome of susceptible E. faecalis encodes a glycopeptide sensor.

ACQUISITION OF TEICOPLANIN RESISTANCE BY VANB-TYPE ENTEROCOCCI

Enterococci harboring clusters of the vanB class remain susceptible to teicoplanin, since this antibiotic does not trigger induction of the resistance genes (8, 17). However, teicoplanin selects mutants resistant to this antibiotic that belong to one of three phenotypic classes (11, 12) due to three distinct alterations of VanSB functions (13, 14) (Table 1). Mutations leading to teicoplanin resistance also confer low-level resistance to the investigational glycopeptide LY333328 (7).

Inducible phenotype.

Mutations leading to inducible expression of vancomycin and teicoplanin resistance introduced amino acid substitutions in the sensor domain of VanSB (13). A minority of the substitutions were located between the two putative trans-membrane segments of VanSB (Fig. 1). This portion of the sensor is located at the outer surface of the membrane and may therefore interact directly with ligands, such as glycopeptides, which do not penetrate into the cytoplasm. The majority of the substitutions were located in the linker that connects the membrane-associated domain to the cytoplasmic catalytic domain. Based on analogies with related sensor kinases, these substitutions may affect signal transduction (13). The analysis of the inducible mutants provides experimental evidence that the N-terminal domain of VanSB is involved in signal recognition and also provides one of the rare examples of modification of specificity of a sensor kinase.

Constitutive phenotype.

Mutations responsible for constitutive expression of the vanB cluster led to amino acid substitutions at two specific positions located on either side of the histidine at position 233, which corresponds to the putative autophosphorylation site of VanSB (13) (Table 1). Constitutive expression of glycopeptide resistance is most probably due to impaired dephosphorylation of VanRB by VanSB, as similar substitutions affecting homologous residues of related sensor kinases impair the phosphatase but not the kinase activity of the proteins (13).

Expression of the vanB cluster was inducible by vancomycin in a mutant in which site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce glutamine instead of histidine at the phosphorylation site at position 233 (Table 1) (4). Taken together, these observations confirmed that dephosphorylation of VanRB is required to prevent transcription of the resistance genes and indicated that the phosphatase activity of VanSB is negatively regulated by vancomycin independently from autophosphorylation at H233 (4, 13).

Heterogeneous phenotype.

The heterogeneous mutants most probably harbor null alleles of vanSB since the mutations introduced translation termination codons at various positions of the gene (Table 1). The antibiotic disk diffusion assay revealed the presence of inhibition zones containing scattered colonies that grew predominantly in 48 h (11). Since this phenotype suggested the presence of a mixture of susceptible and resistant bacteria, the PYB promoter (Fig. 1) was fused to a green fluorescent protein reporter gene in order to analyze gene expression in single cells based on fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry (14). Use of this reporter system revealed that cultures of heterogeneous mutants grown in the absence of glycopeptides contain a major nonfluorescent subpopulation and a smaller sub population with various fluorescence intensities. Thus, VanRB was activating transcription of the resistance genes only in a minority of the bacteria. Attempts to grow fluorescent and nonfluorescent bacteria as pure cultures were unsuccessful, indicating that expression of the resistance genes was reversibly turned on and off under noninducing conditions, a phenomenon referred to as clonal variation (39). Vancomycin and teicoplanin induced expression of the reporter gene in bacteria of the major nonfluorescent subpopulation (14). These observations imply that clonal variation and induction both result from activation of VanRB by a host kinase which is stimulated by glycopeptides.

The amplification loop that results from binding of phospho-VanRB to the PRB promoter and activation of vanRB transcription may be critical for clonal variation (14, 39). If the total concentration of VanRB is low in a bacterium, inefficient phosphorylation of the protein by the putative host kinase may not be adequate to provide sufficient phospho-VanRB for activation of PRB and production of VanRB. Expression of the resistance genes may tend to remain turned off in the progeny of this susceptible bacterium since the concentration of VanRB is expected to remain low following cell division. In contrast, if the concentration of VanRB is high in a bacterium, enough phospho-VanRB may be produced by inefficient phosphorylation by the host kinase so that auto-activation of vanRB transcription occurs and persists over several generations. According to this model, stimulation of the host kinase by glycopeptides results in induction, since this would result in efficient phosphorylation of VanRB in all bacteria. It is worth nothing that the phenomenon of clonal variation observed in vanSB null mutants may be a particular type of adaptative response that enables genetically identical bacteria to express different sets of genes.

In vivo emergence of teicoplanin resistance.

Teicoplanin-resistant mutants have been observed in a patient (24) and in rabbits with experimental endocarditis treated with vancomycin or teicoplanin (11). In the animal model, the combination of gentamicin and teicoplanin was effective in reducing the number of surviving VanB-type E. faecalis organisms in cardiac vegetations and prevented the emergence of resistant mutants (11). Subsequent work revealed that two mutations were required to abolish the synergistic activity of teicoplanin and gentamicin against wild VanB-type strains: an initial mutation that allows expression of teicoplanin resistance by one of the three mechanisms discussed above and a second mutation conferring a moderate (two to fivefold) increase in the intrinsic level of gentamicin resistance (30). Simultaneous acquisition of the two types of mutations is probably a rare event that was not observed in the animal or in vitro (30). These laboratory investigations suggest that emergence of teicoplanin resistance may be responsible for therapeutic failure, although the use of drug combinations may prevent the selection of resistant mutants (11, 30).

Acquisition of teicoplanin resistance in two steps.

VanB-type enterococci requiring vancomycin for growth (vancomycin-dependent phenotype) are readily selected by vancomycin in vitro (13), in a rabbit model of aortic endocarditis (11), and in patients (20, 37). These mutants harbor mutations in the host d-Ala–d-Ala ligase gene and depend entirely on the VanB ligase for peptidoglycan synthesis (13). Impaired d-Ala–d-Ala ligase activity accounts for vancomycin dependence, since the VanB protein is only produced under conditions of induction by this antibiotic. Impaired d-Ala–d-Ala ligase also results in increased resistance to vancomycin, since incorporation of d-Ala–d-Ala into peptidoglycan precursors is abolished (13). Mutations in vanSB that lead to constitutive expression of the resistance genes are readily selected in vancomycin-dependent bacteria, not only on teicoplanin, but also on media devoid of antibiotics, since such mutations allow growth in the absence of the inducer (13, 37). Thus, vancomycin may indirectly select for constitutive teicoplanin resistance in two steps. This may account for the emergence of teicoplanin resistance in a patient treated with vancomycin (24) and may also account for constitutive expression of vanB-related gene clusters in clinical isolates of E. faecalis that harbor null mutations in the ddl d-Ala–d-Ala ligase gene (16).

CROSS TALK AND REGULATION IN HETEROLOGOUS HOSTS

The chromosome of most bacteria encodes several related two-component regulatory systems, and analysis of the unfinished E. faecalis genome sequence available from The Institute for Genomic Research reveals the presence of at least 20 pairs of sensor kinases and response regulators. Sequence conservation in the kinase domain of the sensors and in the effector domain of response regulators can allow inefficient phospho-transfer reactions between nonpartner sensors and response regulators (25, 38). In vivo, such cross-reactivities (cross talk) usually lead to activation of response regulators by heterologous kinases in mutants that do not produce the partner sensor kinase. We shall compare activation of VanR and VanRB by partner and nonpartner sensors in E. faecalis, E. coli, and Bacillus subtilis.

E. faecalis.

Expression of the resistance genes in E. faecalis is inducible by glycopeptides in vanSB and vanS null mutants if the latter harbor PH on a multicopy plasmid (see above and Table 1) (4, 14). Induction occurs with the same set of antibiotics, indicating that the response regulators may be activated by the same kinase (Table 1) (4). These observations raise the possibility that E. faecalis harbors, as of yet, unidentified genes expressed under the control of this putative kinase in response to inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis (4).

E. coli.

The PH and PR promoters of the vanA gene cluster are specifically activated by VanR in E. coli (35). Likewise, the PYB and PRB promoters are specifically activated by VanRB (35). Phosphorylation is required for promoter activation by both response regulators (22, 35). VanR and VanRB belong to the OmpR subfamily of response regulators based on sequence similarity in the DNA binding domains of the proteins (9). Response regulators of this subfamily activate promoters that are recognized by the major form of RNA polymerase corresponding to Eς70 in E. coli (25). Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that there are the same requirements for promoter activation in distantly related bacteria such as E. coli and E. faecalis.

In the absence of VanS, VanR was activated by several mechanisms involving the PhoB and CreB kinases of the Pho regulon and acetyl-phosphate synthesis by the AckA-Pta pathway (22, 35). VanR catalyzes in vitro its own phosphorylation, using acetyl phosphate as a substrate (26), and this reaction may also occur in vivo (22). Deletion of phoR, creB, ackA, and pta prevented activation of the PR and PH promoters by cross talk and allowed investigators to establish that VanS can activate VanR in E. coli (22, 35). Stimulation of VanS by glycopeptides could not be tested in this expression system since the antibiotics do not penetrate the E. coli outer membrane. Thus, in the absence of the known stimulus, VanS appears to act as a kinase in E. coli (35) but as a phosphatase in E. faecalis (5).

The PRB and PYB promoters of the vanB cluster were also activated by VanRB in the absence of VanSB in E. coli (35). Activation by cross talk was observed in the absence of the phoB, creB, ackA, and pta genes, indicating that VanR and VanRB are activated by different pathways. VanSB prevented activation of VanRB by cross talk, revealing that the sensor acts as a phosphatase in the absence of the stimulus, as was shown in E. faecalis.

B. subtilis.

Regulation of the PH promoter was analyzed in B. subtilis hosts producing VanR, VanR and VanS, or neither (36). As expected, VanR was required for promoter activation. Glycopeptides induced PH both in the presence and absence of VanS, although induction required higher drug concentrations in the absence of this sensor. Thus, activation of VanR by cross talk is regulated by glycopeptides in B. subtilis, indicating that this host produces a glycopeptide sensor as does E. faecalis. Of note, a glycopeptide-inducible transcriptional fusion was obtained by screening random insertions of a Tn917 derivative carrying a promoterless lac reporter gene in B. subtilis (28). Expression of the transcriptional fusion might be controlled by the kinase responsible for activation of VanRB in the absence of VanSB.

Cross talk between VanRS and VanRBSB regulatory systems.

Production of the VanS sensor restored homogeneous high-level glycopeptide resistance of a heterogenous vanSB null mutant and significantly increased synthesis of the VanXB d, d-dipeptidase (4). These observations suggest that VanS can phosphorylate VanRB. Activation of VanRB by VanS could not be tested in E. coli since cross talk led to high-level activation of this response regulator (35).

Activation of VanR by VanSB could not be tested in either E. faecalis, since cross talk led to high-level activation of the PH and PR promoters (4), or E. coli, since VanSB a phosphatase in this host, and stimulation by glycopeptides could not be tested (35). Finally, VanS, VanSH164Q, VanSB, and VanSBH233Q did not prevent promoter activation by cross talk in E. coli or E. faecalis, suggesting that the Van sensors cannot dephosphorylate nonpartner Van response regulators (4, 35).

NATURE OF THE STIMULUS

The nature of the signal recognized by the VanS and VanSB sensors is unknown. In fact, it has never been established that signal recognition involves a direct interaction between the sensors and a specific ligand such as glycopeptides or peptidoglycan precursors. Such specific interactions may not exist if signal recognition depends upon a physical constraint imposed on the membrane by the inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis (36). The issue was addressed indirectly by determining which compounds, mostly antibiotics, trigger induction. There are discrepancies between the conclusions of different groups that used different reporter systems in different hosts, although there is a consensus that the vanA gene cluster is inducible by subinhibitory concentrations of all antibiotics that inhibit the transglycosylation reaction, i.e., the transfer of disaccharide-pentapeptide subunits from lipid intermediate II to the nascent peptidoglycan at the outer surface of the membrane. These antibiotics include glycopeptides and moenomycin, which are structurally unrelated and inhibit the transglycosylases by different mechanisms (12, 23).

Three groups found that VanA-type resistance is inducible by glycopeptides and moenomycin but not by drugs that inhibit the reactions preceding (e.g., ramoplanin) or following (e.g., bacitracin and penicillin) transglycosylation (12, 23, 31). This narrow specificity suggests that accumulation of lipid intermediate II, resulting from inhibition of transglycosylation, may be the signal recognized by the VanS sensor. This would account for induction by antibiotics that inhibit the same step of peptidoglycan synthesis but have different structures (12, 23). In contrast, the VanSB sensor may interact directly with vancomycin since teicoplanin is not an inducer (12). Amino acid substitutions in the sensor domain of VanSB allowed induction by teicoplanin but not by moenomycin (see above and Table 1) (12, 13). The primary amino acid sequence of the sensor domains of VanS and VanSB are unrelated (17). These observations indicate that VanS and VanSB may sense the presence of glycopeptides by different mechanisms (13).

Two groups reported induction of VanA-type resistance by inhibitors of late (e.g., glycopeptides, moenomycin, bacitracin, and ramoplanin) but not of early (e.g., fosfomycin and d-cycloserine) stages of peptidoglycan synthesis (1, 21). The broader specificity observed by these authors supports the concept that inhibition of peptidoglycan polymerization is critical for induction but does not imply that accumulation of a specific precursor is involved.

Lastly, one group analyzed regulation of the PH promoter in B. subtilis instead of in enterococcal hosts and reported induction by bacitracin, penicillin, fosfomycin, and d-cycloserine as well as by treatment with lysosyme, mutanolysin, and lysostaphin (36). The authors concluded that it is unlikely that VanS is stimulated by the accumulation of peptidoglycan precursors.

Attempts to correlate antibacterial activity and induction using a large number of glycopeptide antibiotics indicated that binding to the peptidyl-d-Ala–d-Ala target and structural features of the antibiotic may both be important for induction (21). This observation may imply that regulation involves recognition of more than one signal (21) but is also compatible with the possibility that VanS interacts with a lipid intermediate II-glycopeptide complex at the outer surface of the membrane. Of note, two large-scale screenings identified 0.1% (29) and 1% (31) of inducers among 6,800 and 8,000 compounds, respectively, revealing induction of VanA-type resistance by a few additional compounds, including some membrane-active agents such as polymyxin B.

In vivo analysis is clearly not sufficient to associate an inducing signal with a specific kinase, since response regulators may be stimulated by cross talk. For example, it is possible that activation of VanR in response to moenomycin in wild VanA-type strains depends not upon a modification of the signaling status of VanS but upon stimulation of the putative heterologous kinase that was revealed by the analysis of vanS null mutants (Table 1). Cross talk is expected to vary in different hosts, and this may account for some of the discrepancies concerning the induction specificity of the VanS sensor.

CONCLUSIONS

Several aspects of regulation of the vanA and vanB gene cluster, including the phosphotransfer reactions (Fig. 1) and promoter activation (Fig. 2), are well characterized based on in vivo analysis of the impact of mutations in the regulatory genes (Table 1) and in vitro analysis of protein functions. In contrast, our understanding of signal recognition remains limited. Likewise, the importance of cross talk in regulation of glycopeptide resistance has been revealed by numerous analyses, although host factors involved in this process remain to be identified. Detection of inducible expression of glycopeptide resistance genes in the absence of the VanS or VanSB sensors suggests that regulation of the vanA and vanB cluster may be more integrated in host regulation than was initially anticipated. This observation also suggests that specific host genes may be turned on in response to glycopeptides in susceptible bacteria.

Acquisition of teicoplanin resistance by VanB-type strains, in particular constitutive expression of the resistance genes associated with impaired host d-Ala–d-Ala ligase activity, appears to be a potential trend in the evolution of VanB-type resistance. This may ultimately lead to exclusive production of d-Lac-ending precursors in enterococci. However, production of such precursors is associated with hypersusceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics in some enterococci, presumably because certain low-affinity penicillin binding proteins are unable to efficiently function with d-Lac-ending precursors (2, 13). This could contribute to counterselection of bacteria expressing glycopeptide resistance constitutively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen N E, Hobbs J N., Jr Induction of vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium by non-glycopeptide antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;132:107–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Obeid S, Billot-Klein D, Van Heijenoort J, Collatz E, Gutmann L. Replacement of the essential penicillin-binding protein 5 by high-molecular mass PBPs may explain vancomycin-β-lactam synergy in low-level vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium D366. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;91:79–84. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90566-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Cabanie L, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. Requirement of the VanY and VanX d, d-peptidases for glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:819–830. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Courvalin P. Regulated interactions between partner and non-partner sensors and response regulators that control glycopeptide resistance gene expression in enterococci. Microbiology. 1999;145:1849–1858. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-8-1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Gerbaud G, Galimand M, Leclereq R, Courvalin P. The VanS sensor negatively controls VanR-mediated transcriptional activation of glycopeptide resistance genes of Tn1546 and related elements in the absence of induction. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:97–106. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.97-106.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Molinas C, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. The vanZ gene of Tn1546 from Enterococcus faecium BM 4147 confers resistance to teicoplanin. Gene. 1995;154:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00851-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. Moderate-level resistance to glycopeptide LY333328 mediated by genes of the vanA and vanB clusters in enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1875–1880. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arthur M, Depardieu F, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. Quantitative analysis of the metabolism of soluble cytoplasmic peptidoglycan precursors of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:33–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arthur M, Molinas C, Courvalin P. The VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system controls synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2582–2591. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2582-2591.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arthur M, Reynolds P, Courvalin P. Glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(96)10063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aslangul E, Baptista M, Fantin B, Depardieu F, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Carbon C. Selection of glycopeptide-resistant mutants of VanB-type Enterococcus faecalis BM4281 in vitro and in experimental endocarditis. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:598–605. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.3.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baptista M, Depardieu F, Courvalin P, Arthur M. Specificity of induction of glycopeptide resistance genes in Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2291–2295. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baptista M, Depardieu F, Reynolds P, Courvalin P, Arthur M. Mutations leading to increased levels of resistance to glycopeptide and antibiotics in VanB-type enterococci. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:93–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4401812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baptista M, Rodrigues P, Depardieu F, Courvalin P, Arthur M. Single cell analysis of glycopeptide resistance gene expression in teicoplanin-resistant mutants of VanB-type Enterococcus faecalis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:17–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bugg T D H, Wright G D, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Walsh C T. Molecular basis for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium BM4147: biosynthesis of a depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursor by vancomycin resistance proteins VanH and VanA. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10408–10415. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casadewall B, Courvalin P. Characterization of the vanD glycopeptide resistance gene cluster from Enterococcus faecium BM4339. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3644–3648. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3644-3648.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evers S, Courvalin P. Regulation of VanB-type vancomycin resistance gene expression by the VanSB-VanRB two-component regulatory system in Enterococcus faecalis V583. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1302–1309. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1302-1309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher S L, Jiang W, Wanner B L, Walsh C T. Cross-talk between the histidine protein kinase VanS and the response regulator PhoB. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23143–23149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.23143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher S L, Kim S-K, Wanner B L, Walsh C T. Kinetic comparison of the specificity of the vancomycin resistance kinase VanS for two response regulators, VanR and PhoB. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4732–4740. doi: 10.1021/bi9525435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraimow H S, Jungkind D L, Lander D W, Delso D R, Dean J L. Urinary tract infection with an Enterococcus faecalis isolate that requires vancomycin for growth. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:22–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-1-199407010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grissom-Arnold J, Alborn W E, Jr, Nicas T I, Jaskunas S R. Induction of VanA vancomycin resistance genes in Enterococcus faecalis: use of a promoter fusion to evaluate glycopeptide and nonglycopeptide induction signals. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:53–64. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haldimann A, Fisher S L, Daniels L L, Walsh C T, Wanner B L. Transcriptional regulation of the Enterococcus faecium BM4147 vancomycin resistance gene cluster by the VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5903–5913. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5903-5913.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handwerger S, Kolokathis A. Induction of vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium by inhibition of transglycosylation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;70:167–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb13972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayden M K, Trenholme G M, Schultz J E, Sahm D F. In vivo development of teicoplanin resistance in a VanB Enterococcus faecium isolate. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:1224–1227. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.5.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoch J A, Silhavy T J. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holman T R, Wu Z, Wanner B L, Walsh C T. Identification of the DNA-binding site for the phosphorylated VanR protein required for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4625–4631. doi: 10.1021/bi00181a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsing W, Silhavy T J. Function of conserved histidine-243 in phosphatase activity of EnvZ, the sensor for porin osmoregulation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3729–3735. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3729-3735.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirsch D R, Lai M H, McCullough J, Gillum A. The use of β-galactosidase gene fusions to screen for antibacterial antibiotics. J Antibiot. 1991;44:210–217. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai M H, Kirsch D R. Induction signals for vancomycin resistance encoded by the vanA gene cluster in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1645–1648. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.7.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lefort A, Baptista M, Fantin B, Depardieu F, Arthur M, Carbon C, Courvalin P. Two-step acquisition of resistance to the teicoplanin-gentamicin combination by VanB-type Enterococcus faecalis in vitro and in experimental endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:476–482. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mani N, Sancheti P, Jiang Z D, McNaney C, DeCenzo M, Knight B, Stankis M, Kuranda M, Rothstein D M, Sanchet P, Knighti B. Screening systems for detecting inhibitors of cell wall transglycosylation in Enterococcus. J Antibiot. 1998;51:471–479. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.51.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall C G, Lessard I A, Park I, Wright G D. Glycopeptide antibiotic resistance genes in glycopeptide-producing organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2215–2220. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds P E. Structure, biochemistry and mechanism of action of glycopeptide antibiotics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:943–950. doi: 10.1007/BF01967563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds P E, Depardieu F, Dutka-Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P. Glycopeptide resistance mediated by enterococcal transposon Tn1546 requires production of VanX for hydrolysis of d-alanyl-d-alanine. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1065–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva J C, Haldimann A, Prahalad M K, Walsh C T, Wanner B L. In vivo characterization of the type A and B vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) VanRS two-component systems in Escherichia coli: a nonpathogenic model for studying the VRE signal transduction pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11951–11956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ulijasz A T, Grenader A, Weisblum B. A vancomycin-inducible LacZ reporter system in Bacillus subtilis: induction by antibiotics that inhibit cell wall synthesis and lysozyme. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6305–6309. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.21.6305-6309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Bambeke F, Chauvel M, Reynolds P E, Fraimow H S, Courvalin P. Vancomycin-dependent Enterococcus faecalis clinical isolates and revertant mutants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:41–47. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wanner B L. Is cross regulation by phosphorylation of two-component response regulator proteins important in bacteria? J Bacteriol. 1992;174:2053–2058. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2053-2058.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wanner B L. Phosphorous assimilation and control of the phosphate regulon. In: Neidhardt F C, CurtissIII R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 1357–1381. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright G D, Holman T R, Walsh C T. Purification and characterization of VanR and the cytosolic domain of VanS: a two-component regulatory system required for vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5057–5063. doi: 10.1021/bi00070a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]