Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been suggested to increase the risk of depression and anxiety disorders. This study expanded upon previous findings by estimating the changes in medical visits for various psychological disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before COVID-19. The entire Korean population ≥ 20 years old (~42.3 million) was included. The first COVID-19 case in Korea was reported on 20 January 2020. Thus, the period from January 2018 through to February 2020 was classified as “before COVID-19”, and the period from March 2020 through to May 2021 was classified as “during COVID-19”. Monthly medical visits due to the following 13 psychological disorders were evaluated: depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, primary insomnia, schizophrenia, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, addephagia, alcoholism, nicotine dependency, and gambling addiction were evaluated. The differences in the number of medical visits and the variance of diseases before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and Levene’s test. Subgroup analyses were conducted according to age and sex. The frequencies of medical visits for depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, primary insomnia, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, PTSD, anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, addephagia, and gambling addiction were higher during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (all p < 0.001). However, the frequencies of medical visits for schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency were lower during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic (all p < 0.001). The psychological disorders with a higher frequency of medical visits during COVID-19 were consistent in all age and sex subgroups. In the old age group, the number of medical visits due to schizophrenia was also higher during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (p < 0.001). Many psychological disorders, including depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, primary insomnia, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, PTSD, anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, addephagia, and gambling addiction, had a higher number of related medical visits, while disorders such as schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency had a lower number of related medical visits during COVID-19 among Korean adults.

Keywords: COVID-19, depression, anxiety, panic disorder, schizophrenia

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has exposed the worldwide population to both physical and mental health concerns [1,2]. In addition to the physical illness related to the disease, there have been several factors, such as domestic violence, that can induce psychological distress and insomnia during the COVID-19 pandemic [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The latent period, infectivity, and prognosis of COVID-19 cannot be predicted. Thus, quarantine rules have been shifted several times in many countries, which could induce anxiety due to uncertainty. The lack of therapeutics for COVID-19 was another fear during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the emergence of novel variants that evade vaccination-induced immunity discourages the public from receiving vaccines. The long-lasting COVID-19 pandemic impaired social activities and economic status due to social distancing measures and the lockdown of industries, respectively [9]. Thus, it can be suggested that the frequency of psychological disorders increased during the COVID-19 pandemic [10].

A number of recent studies have examined the hazardous impacts of COVID-19 on psychological disorders [8,11,12]. A meta-analysis reported that the pooled prevalence of anxiety and depression was high during the COVID-19 pandemic (33% [95% confidence intervals (CI) = 28–38%] for anxiety and 28% [95% CI = 23–32%] for depression) in the general population [12]. In a global burden of disease study in 204 countries, SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and decreased mobility in humans were related to the increased prevalence of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder [13]. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological distress were different according to age and sex. For instance, women and younger populations (≤20 years old) showed an increased risk of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic [14]. Our previous questionnaire-based study estimated that there was no significant increase in the rate of depression during the early COVID-19 pandemic period (from 16 August 2020 to 31 October 2020) [15]. However, the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic could increase the rates of depression and other psychological disorders, such as anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [16]. Thus, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on a wide range of psychological disorders need to be evaluated in a large population cohort.

We hypothesized that the COVID-19 pandemic has an impact on various psychological disorders as well as depression and anxiety disorders. To test this hypothesis, the nationwide population data for medical visits due to various psychological disorders, including depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, primary insomnia, schizophrenia, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, PTSD, anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, addephagia, nicotine dependency, and gambling addiction, were compared before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

The ethics committee of Hallym University (2021-11-004) approved the use of these data. The study was exempted from the need for written informed consent by the institutional review board.

2.2. Participants and Measurement

This study included the entire Korean adult population (~42.3 million, ≥20 years old) without an exception, as a single health insurance system covers the whole country and the entire Korean adult population legally registered to the national health insurance system. Thus, we were able to obtain the data of all Koreans in primary clinics and tertiary hospitals. In this study, we evaluated the frequency of medical visits due to psychological disorders from January 2018 through to May 2021. As the first COVID-19 cases were discovered in Korea on 20 January 2020, and disease prevention and control started on March 2020, we defined the periods of ‘before COVID-19’ and ‘during COVID-19’ as before February 2020 and after March 2020, respectively.

We evaluated the monthly number of medical visits for 13 psychological diseases that are common in primary clinics. The patients were diagnosed with each disease using ICD-10 codes: depressive disorder (F32, F33), bipolar disorder (F31), primary insomnia (F510, G470), schizophrenia (F20, F21, F231, F232, F25), panic disorder (F400, F410), hypochondriasis (F452), PTSD (F431), anxiety disorder (F40, F41), anorexia nervosa (F500, F501, F508), addephagia (F502, F503, F504, F505), alcoholism (F100, F100, F103), nicotine dependency (T652, F170, F171, F172), and gambling addiction (F630, Z726). The medical visits were calculated without duplicate visits, as we had the medical records of the entire hospital or clinics, and patients were identified by unique resident registration numbers.

2.3. Statistics

The differences in the mean number of medical visits due to psychological disorders before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for nonparametric values. The differences in the variances of diseases before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were compared using Levene’s test for nonparametric values [17]. For the subgroup analyses, we divided the participants by age (0–19 years old, 20–59 years old, and 60+ years old) and sex.

All analyses were two-tailed, and p values < 0.05 were considered to indicate significance. The results were analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

For all examined psychological diseases, there were different frequencies of related medical visits before and during COVID-19 (all p < 0.001, Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviation of incidence of diseases before and during COVID-19, and their difference.

| Diseases | Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | p-Values of Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | Variance | |

| Depressive disorder | 292,620.1 | 13,403.1 | 331,656.6 | 15,192.2 | <0.001 * | 0.065 |

| Bipolar disorder | 47,067.7 | 2728.7 | 52,970.3 | 1708.0 | <0.001 * | 0.046 † |

| Primary insomnia | 157,690.5 | 9721.9 | 178,290.8 | 7332.3 | <0.001 * | 0.100 |

| Schizophrenia | 79,229.4 | 1583.9 | 77,719.1 | 1073.1 | <0.001 * | 0.113 |

| Panic disorder | 68,631.9 | 4846.0 | 81,340.6 | 3953.8 | <0.001 * | 0.046 † |

| Hypochondriasis | 704.7 | 35.5 | 895.8 | 120.0 | <0.001 * | 0.224 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 2606.5 | 228.9 | 3211.4 | 279.5 | <0.001 * | 0.140 |

| Anxiety disorder | 215,058.6 | 10,457.6 | 244,046.6 | 11,009.8 | <0.001 * | 0.052 |

| Anorexia nervosa | 605.0 | 95.3 | 729.1 | 53.1 | <0.001 * | 0.080 |

| Addephagia | 690.5 | 43.7 | 832.1 | 65.2 | <0.001 * | 0.108 |

| Alcoholism | 19,248.2 | 482.0 | 18,489.0 | 535.9 | <0.001 * | 0.115 |

| Nicotine dependency | 380.4 | 47.4 | 308.5 | 33.6 | <0.001 * | 0.279 |

| Gambling addiction | 297.5 | 32.3 | 414.1 | 69.0 | <0.001 * | 0.014 † |

* Mann–Whitney U test, significance at <0.05. † Levene’s test in non-parametric data, significance at <0.05.

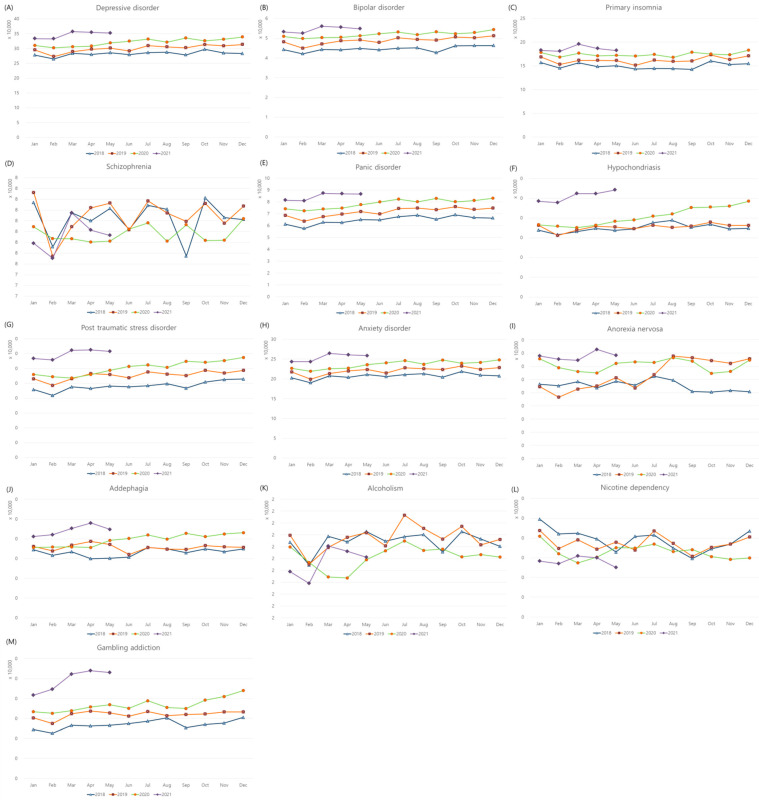

Medical visits due to depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, primary insomnia, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, PTSD, anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, addephagia, and gambling addiction were more common during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (Figure 1A–C,E–J,M). On the other hand, medical visits due to schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency were less common during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (Figure 1D,K,L). The variance in bipolar disorder and panic disorder was lower during COVID-19 than before COVID-19, while that in gambling addiction was higher during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (all p < 0.05). Other psychological disorders did not show a difference in variance between the two time periods.

Figure 1.

Monthly medical visits for psychological diseases in 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021. The incidences of (A) depressive disorder, (B) bipolar disorder, (C) primary insomnia, (D) schizophrenia, (E) panic disorder, (F) hypochondriasis, (G) posttraumatic stress disorder, (H) anxiety disorder, (I) anorexia nervosa, (J) addephagia, (K) alcoholism, (L) nicotine dependency, and (M) gambling addiction.

Regarding sex, males had a higher frequency of medical visits due to all examined psychological disorders except schizophrenia, addephagia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency during the COVID-19 pandemic (all p < 0.001, Table 2). Medical visits for schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency were less common among males during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (all p < 0.05). Among females, there was a higher frequency of medical visits due to all examined psychological disorders except schizophrenia and nicotine addiction during COVID-19 (all p < 0.05). Medical visits due to schizophrenia were less common during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (p = 0.036), and there was no difference in the frequency of medical visits due to nicotine dependency between the two time periods.

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation of incidence of diseases before and during COVID-19, and their difference in the subgroup by sex.

| Diseases | Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | p-Values of Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | Variance | |

| Men | ||||||

| Depressive disorder | 93,001.0 | 4416.1 | 103,448.4 | 3957.7 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Bipolar disorder | 18,939.4 | 999.0 | 20,628.0 | 537.7 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Primary insomnia | 62,275.8 | 4002.0 | 70,463.9 | 2474.7 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Schizophrenia | 36,100.1 | 741.9 | 35,035.8 | 446.3 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Panic disorder | 32,491.6 | 2103.5 | 37,652.8 | 1529.4 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Hypochondriasis | 367.3 | 18.9 | 487.4 | 88.1 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1016.6 | 84.1 | 1209.3 | 97.0 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anxiety disorder | 88,061.0 | 4359.1 | 98,208.9 | 3824.1 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anorexia nervosa | 125.0 | 21.6 | 147.8 | 18.1 | 0.004 * | 0.001 † |

| Addephagia | 56.7 | 7.1 | 54.6 | 5.9 | 0.283 | 0.352 |

| Alcoholism | 15,908.8 | 388.4 | 14,929.1 | 422.6 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Nicotine dependency | 338.4 | 42.9 | 267.1 | 30.0 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Gambling addiction | 284.1 | 30.6 | 397.7 | 68.6 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Women | ||||||

| Depressive disorder | 199,619.1 | 9033.8 | 228,208.2 | 11,259.4 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Bipolar disorder | 28,128.2 | 1735.0 | 32,342.3 | 1176.9 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Primary insomnia | 95,414.7 | 5747.8 | 107,826.9 | 4878.0 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Schizophrenia | 43,129.3 | 895.2 | 42,683.3 | 647.1 | 0.036 * | 0.099 |

| Panic disorder | 36,140.3 | 2746.4 | 43,687.8 | 2437.3 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Hypochondriasis | 337.5 | 24.0 | 408.4 | 35.6 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1589.9 | 148.0 | 2002.1 | 184.8 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anxiety disorder | 126,997.6 | 6125.2 | 145,837.7 | 7225.4 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anorexia nervosa | 479.9 | 75.5 | 581.3 | 41.3 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Addephagia | 633.9 | 41.3 | 777.5 | 64.9 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Alcoholism | 3339.4 | 115.7 | 3559.9 | 147.5 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Nicotine dependency | 42.0 | 10.4 | 41.5 | 7.4 | 0.947 | 0.863 |

| Gambling addiction | 13.5 | 3.8 | 16.4 | 3.2 | 0.018 * | 0.016 † |

* Mann–Whitney U test, significance at <0.05. † Levene’s test in non-parametric data, significance at <0.05.

Regarding age groups, the 20–39-year-old group demonstrated a higher frequency of medical visits due to all of the examined psychological disorders except for schizophrenia and nicotine dependency (all p < 0.05, Table 3). The frequencies of medical visits for schizophrenia and nicotine dependency were lower during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (both p < 0.05). In the 40- to 59-year-old group, there was a higher frequency of medical visits due to all of the examined psychological disorders except schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency during COVID-19; however, there was a lower frequency of medical visits due to schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency during COVID-19 (all p < 0.05). In the ≥60-year-old group, there was a higher frequency of medical visits due to all examined psychological disorders except alcoholism and nicotine dependency during COVID-19 than before COVID-19 (all p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Mean, standard deviation of incidence of diseases before and during COVID-19, and their difference in the subgroup by age.

| Diseases | Before COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | p-Values of Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | Variance | |

| Age 20–39 years old | ||||||

| Depressive disorder | 71,186.6 | 8426.6 | 98,224.07 | 8281.236 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Bipolar disorder | 16,655.5 | 1345.4 | 20,394.40 | 1039.450 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Primary insomnia | 23,920.1 | 1123.4 | 26,040.13 | 657.012 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Schizophrenia | 25,253.5 | 535.2 | 24,169.13 | 364.634 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Panic disorder | 21,229.2 | 1928.8 | 25,956.20 | 1309.550 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Hypochondriasis | 147.6 | 13.5 | 192.33 | 32.797 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1157.4 | 107.9 | 1538.40 | 158.457 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anxiety disorder | 49,638.9 | 4329.4 | 61,145.00 | 3890.384 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anorexia nervosa | 151.7 | 13.4 | 177.80 | 17.729 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Addephagia | 507.9 | 34.0 | 631.20 | 51.985 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Alcoholism | 2800.4 | 142.0 | 2944.40 | 124.962 | 0.003 * | 0.002 † |

| Nicotine dependency | 80.0 | 15.7 | 67.47 | 14.918 | 0.014 * | 0.017 † |

| Gambling addiction | 209.5 | 29.3 | 304.93 | 54.928 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Age 40–59 years old | ||||||

| Depressive disorder | 93,126.1 | 2946.4 | 98,709.6 | 3436.8 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Bipolar disorder | 17,747.2 | 650.9 | 18,579.3 | 403.8 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Primary insomnia | 53,514.6 | 2709.5 | 58,857.4 | 1673.9 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Schizophrenia | 39,003.7 | 913.6 | 37,193.2 | 574.2 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Panic disorder | 33,226.0 | 2009.9 | 37,970.7 | 1675.0 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Hypochondriasis | 286.6 | 16.8 | 374.6 | 55.5 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 949.5 | 80.0 | 1072.3 | 78.5 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anxiety disorder | 83,498.2 | 3552.9 | 90,802.9 | 3552.5 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anorexia nervosa | 75.3 | 11.4 | 82.5 | 5.4 | 0.024 * | 0.029 † |

| Addephagia | 136.4 | 11.7 | 153.3 | 16.2 | 0.002 * | <0.001 † |

| Alcoholism | 9555.7 | 286.1 | 8812.7 | 284.2 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Nicotine dependency | 203.0 | 32.1 | 160.9 | 19.2 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Gambling addiction | 69.5 | 7.9 | 87.6 | 11.9 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Age 60+ years old | ||||||

| Depressive disorder | 128,307.4 | 3547.4 | 134,722.9 | 3962.8 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Bipolar disorder | 12,665.0 | 770.7 | 13,996.6 | 345.2 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Primary insomnia | 80,255.8 | 6311.4 | 93,393.3 | 5484.8 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Schizophrenia | 14,972.2 | 636.7 | 16,356.7 | 485.1 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Panic disorder | 14,176.7 | 975.5 | 17,413.7 | 1064.2 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Hypochondriasis | 270.5 | 16.0 | 328.9 | 36.1 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 499.5 | 50.3 | 600.7 | 48.3 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anxiety disorder | 81,921.5 | 3288.4 | 92,098.7 | 3965.8 | <0.001 * | <0.001 † |

| Anorexia nervosa | 377.9 | 83.8 | 468.9 | 41.1 | 0.002 * | <0.001 † |

| Addephagia | 46.2 | 6.0 | 47.6 | 9.0 | 0.569 | <0.001 † |

| Alcoholism | 6892.1 | 148.7 | 6731.9 | 173.4 | 0.007 * | 0.003 † |

| Nicotine dependency | 97.5 | 14.8 | 80.1 | 13.4 | 0.001 * | 0.001 † |

| Gambling addiction | 18.5 | 3.5 | 21.5 | 4.3 | 0.023 * | 0.020 † |

* Mann–Whitney U test, significance at <0.05. † Levene’s test in non-parametric data, significance at <0.05.

4. Discussion

Various psychological disorders, including depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, primary insomnia, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, PTSD, anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, addephagia, and gambling addiction, were more common during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic in Korean adults. On the other hand, the frequencies of medical visits due to schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency were lower during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic in Korean adults. Both males and females demonstrated similar trends. In the elderly population, in addition to other psychological disorders, medical visits due to schizophrenia were also more common during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic. The current results extended previous knowledge on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological disorders by addressing the changes in the frequency of medical visits for a wide range of psychological disorders in a nationwide, population-based study.

In the present study, there was an increase in the frequency of medical visits due to depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, primary insomnia, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, PTSD, anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, addephagia, and gambling addiction during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic. In line with the current results, many recent studies have demonstrated an increase in the frequency of medical visits due to major psychological disorders, such as depressive disorder and anxiety disorder [18,19,20]. An online survey found that 17.6% of general citizens in 11 countries reported the novel occurrence of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and panic disorder (11.4% reported PTSD, 8.4% reported anxiety, 9.3% reported depression, and 3% reported panic disorder) [20]. The environmental changes during the COVID-19 pandemic and the direct effects of COVID-19 on physical health may have contributed to the increased frequency of medical visits due to these psychological diseases. Quarantine strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic restricted social activities, which could induce social isolation. In addition, nationwide campaigns and information on the COVID-19 pandemic could evoke COVID-19-related fear [21]. Moreover, suffering from COVID-19 could cause physical and mental illness [22]. Among patients with COVID-19, approximately 45% (95% CI = 37–54%) and 47% (95% CI = 37–57%) of patients suffered from depression and anxiety, respectively [15]. It was also suggested that COVID-19 can directly affect the central nervous system, although its predominant target organ is the respiratory tract [23,24,25].

On the other hand, the frequencies of medical visits for schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency were lower during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic in this study. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical visits due to schizophrenia has not been well defined. The inaccessibility to medical care could impact the lower number of medical visits for schizophrenia during COVID-19 in this study. Due to the redistribution of medical resources to cope with COVID-19, the shortage of medical access could limit the treatment of schizophrenia during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the deficiency of information and concerns about COVID-19 in patients with schizophrenia could reduce the impact of COVID-19 on psychological symptoms [26]. Patients with schizophrenia have been reported to show less awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic due to poor physical health, poor socioeconomic status, social isolation, and social stigma or discrimination [26,27]. For alcoholism and nicotine dependency, there have been concerns about the increased risk of addiction and dependency on alcohol and nicotine use [28]. However, a cross-sectional survey in an adult population in England demonstrated no significant change in the prevalence of smoking, while attempts to quit smoking increased (adjusted odds ratio = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.22–3.33) [29]. The increased awareness of health care issues and nationwide health care strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic could motivate the cessation of alcohol, smoking, or drug abuse. Additionally, social attention for the cessation of these additions might be decreased while coping with COVID-19; thus, the detection of these addictive behaviors might have been due to the increase in attention.

Among women, in addition to other psychological disorders, the number of medical visits due to alcoholism was higher during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic in this study. Women have been predicted to be more susceptible to the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological disorders, such as depression and anxiety [12]. According to age, in the older population, the medical visits due to psychological disorders were higher during the COVID-19 pandemic, even visits due to schizophrenia. The higher prevalence of comorbidities could impose additional vulnerability to various psychological disorders among the elderly population. Social isolation and loneliness might be more common in the elderly population during the COVID-19 pandemic [30], which could result in insufficient socioeconomic support to prevent psychological disorders [31]. It has been previously reported that people who were not supported by sufficient supplies and had low levels of family coherence had a higher incidence of stress, anxiety, and depression [32].

This nationwide population-based study revealed higher incidences of various psychological disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic than before the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the current study revealed the unique finding that during the pandemic, the frequencies of medical visits due to some psychological disorders, such as schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine addiction, were lower or not significantly different than before the COVID-19 pandemic. These trends of psychological disorder-related medical visits during the COVID-19 pandemic could be valuable for establishing psychological health policies and managing patients with psychological disorders. However, a few limitations need to be addressed. Because the present study examined the national health claim codes, the population who did not visit the clinic can be missed in this study. In addition, some sensitive or susceptible population could already feel uncomfortable and need mental health care just before COVID-19. Although this study compared the frequency of medical visits due to psychological disorders before and during the COVID-19 pandemic period, the follow-up data for each participant could not be accessed. Thus, causality between the COVID-19 pandemic and psychological disorder-related medical visits was lacking. In addition, comorbid conditions and socioeconomic status could not be considered in this study. Because the COVID-19 pandemic has had an impact on various comorbidities, including cardiovascular diseases, neurologic disorders, and socioeconomic status, changes in these comorbidities and socioeconomic status could mediate the differences in the frequency of psychological disorder-related medical visits. Lastly, this study only analyzed one ethnic population, i.e., Koreans. The severity of the COVID-19 pandemic, the quarantine strategies imposed by a government, and the effects of ethnicity on psychological disorders can influence the frequency of psychological disorder-related medical visits. In Korea, the infection rate of SARS-CoV-2 was lower (less than <1% of the total population) than that in the US or European countries during the study period (until May 2021), and the Korean government maintained stratified social distancing policies, which prevented a lockdown crisis during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Although medical resources were concentrated on COVID-19, medical accessibility was not impaired during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Thus, the trends of medical visits for psychological disorders could be different in other countries.

5. Conclusions

The frequencies of medical visits due to many psychological diseases, including depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, primary insomnia, panic disorder, hypochondriasis, PTSD, anxiety disorder, anorexia nervosa, addephagia, and gambling addiction were higher during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Korean adult population. On the other hand, the frequencies of medical visits due to certain psychological diseases, such as schizophrenia, alcoholism, and nicotine dependency were lower during COVID-19 than before COVID-19. The women and old population showed higher susceptibility to the increased psychological diseases during COVID-19 than other populations.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript was edited for proper English language, grammar, punctuation, spelling, and overall style by highly qualified native English-speaking editors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.G.C.; methodology, H.G.C.; software, D.M.Y.; validation, M.-J.K. and J.-H.K. (Ji-Hee Kim); formal analysis, D.M.Y.; investigation, H.G.C. and S.Y.K.; data curation, D.M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.K.; writing—review and editing, J.-H.K. (Joo-Hee Kim), W.-J.B. and H.G.C.; visualization, H.G.C.; supervision, H.G.C.; project administration, H.G.C.; funding acquisition, W.-J.B. and H.G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Hallym University Research Fund (HURF) and in part by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea, grant numbers “NRF-2021-R1C1C1004986” and “NRF-2022R1C1C1003077”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Hallym University (2021-11-004) following the guidelines of the IRB.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the fact that the study utilized secondary data.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from the Korean National Health Insurance Sharing Service (NHISS) and are available at https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr (accessed on 25 January 2022) with the permission of the NHIS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Park J.-H., Jang W., Kim S.-W., Lee J., Lim Y.-S., Cho C.-G., Park S.-W., Kim B.H. The Clinical Manifestations and Chest Computed Tomography Findings of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Patients in China: A Proportion Meta-Analysis. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;13:95–105. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.00570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S.Y., Kim D.W. Does the Clinical Spectrum of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Show Regional Differences? Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;13:83–84. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.00612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashraf A., AIi I., Ullah F. Domestic and gender-Based violence: Pakistan scenario amidst COVID-19. Asian J. Soc. Health Behav. 2021;4:47–50. doi: 10.4103/shb.shb_45_20. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alimoradi Z., Gozal D., Tsang H.W.H., Lin C., Broström A., Ohayon M.M., Pakpour A.H. Gender-specific estimates of sleep problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 2022;31:e13432. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alimoradi Z., Broström A., Tsang H.W., Griffiths M.D., Haghayegh S., Ohayon M.M., Lin C.-Y., Pakpour A.H. Sleep problems during COVID-19 pandemic and its’ association to psychological distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;36:100916. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olashore A.A., Akanni O.O., Fela-Thomas A.L., Khutsafalo K. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on health-care workers in African Countries: A systematic review. Asian J. Soc. Health Behav. 2021;4:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajabimajd N., Alimoradi Z., Griffiths M.D. Impact of COVID-19-related fear and anxiety on job attributes: A systematic review. Asian J. Soc. Health Behav. 2021;4:51–55. doi: 10.4103/shb.shb_24_21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong L., Bouey J. Public Mental Health Crisis during COVID-19 Pandemic, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1616–1618. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrante G., Camussi E., Piccinelli C., Senore C., Armaroli P., Ortale A., Garena F., Giordano L. Did social isolation during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic have an impact on the lifestyles of citizens? Epidemiol. Prev. 2020;44:353–362. doi: 10.19191/EP20.5-6.S2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hossain M., Tasnim S., Sultana A., Faizah F., Mazumder H., Zou L., McKyer E.L.J., Ahmed H.U., Ma P. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: A review. F1000Research. 2020;9:636. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24457.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michail D., Anastasiou D., Palaiologou N., Avlogiaris G. Social Climate and Psychological Response in the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in a Greek Academic Community. Sustainability. 2022;14:1576. doi: 10.3390/su14031576. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo M., Guo L., Yu M., Jiang W., Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113190. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., Chen-Li D., Iacobucci M., Ho R., Majeed A., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S.Y., Yoo D.M., Min C., Choi H.G. Assessment of the difference in depressive symptoms of the Korean adult population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic using a community health survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2022;300:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu M.-Y., Ahorsu D.K., Kukreti S., Strong C., Lin Y.-H., Kuo Y.-J., Chen Y.-P., Lin C.-Y., Chen P.-L., Ko N.-Y., et al. The Prevalence of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms, Sleep Problems, and Psychological Distress Among COVID-19 Frontline Healthcare Workers in Taiwan. Front. Psychiatry. 2021;12:705657. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.705657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordstokke D.W., Zumbo B.D. A New Nonparametric Levene Test for Equal Variances. Psicológica. 2010;31:401–430. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lebel C., MacKinnon A., Bagshawe M., Tomfohr-Madsen L., Giesbrecht G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;277:5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serafini G., Parmigiani B., Amerio A., Aguglia A., Sher L., Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM Int. J. Med. 2020;113:531–537. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgieva I., Lepping P., Bozev V., Lickiewicz J., Pekara J., Wikman S., Loseviča M., Raveesh B., Mihai A., Lantta T. Prevalence, New Incidence, Course, and Risk Factors of PTSD, Depression, Anxiety, and Panic Disorder during the COVID-19 Pandemic in 11 Countries. Healthcare. 2021;9:664. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9060664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bäuerle A., Teufel M., Musche V., Weismüller B., Kohler H., Hetkamp M., Dörrie N., Schweda A., Skoda E.-M. Increased generalized anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Germany. J. Public Health. 2020;42:672–678. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng J., Zhou F., Hou W., Silver Z., Wong C.Y., Chang O., Huang E., Zuo Q.K. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021;1486:90–111. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pantelis C., Jayaram M., Hannan A.J., Wesselingh R., Nithianantharajah J., Wannan C.M., Syeda W.T., Choy K.C., Zantomio D., Christopoulos A., et al. Neurological, neuropsychiatric and neurodevelopmental complications of COVID-19. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2021;55:750–762. doi: 10.1177/0004867420961472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn E.-J., Min H.J. Prevalence of Olfactory or Gustatory Dysfunction in COVID-19 Patients: An Analysis Based on Korean Nationwide Claims Data. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;14:427–430. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.02215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim D.H., Kim S.W., Stybayeva G., Lim S.Y., Hwang S.H. Predictive Value of Olfactory and Taste Symptoms in the Diagnosis of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;14:312–320. doi: 10.21053/ceo.2020.02369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barlati S., Nibbio G., Vita A. Schizophrenia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2021;34:203–210. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozloff N., Mulsant B.H., Stergiopoulos V., Voineskos A.N. The COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Implications for People With Schizophrenia and Related Disorders. Schizophr. Bull. 2020;46:752–757. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallet J., Dubertret C., Le Strat Y. Addictions in the COVID-19 era: Current evidence, future perspectives a comprehensive review. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2021;106:110070. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson S.E., Garnett C., Shahab L., Oldham M., Brown J. Association of the COVID-19 lockdown with smoking, drinking and attempts to quit in England: An analysis of 2019–20 data. Addiction. 2021;116:1233–1244. doi: 10.1111/add.15295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armitage R., Nellums L.B. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e256. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30061-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santini Z.I., Jose P.E., Cornwell E.Y., Koyanagi A., Nielsen L., Hinrichsen C., Meilstrup C., Madsen K.R., Koushede V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e62–e70. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehman U., Shahnawaz M.G., Khan N.H., Kharshiing K.D., Khursheed M., Gupta K., Kashyap D., Uniyal R. Depression, Anxiety and Stress Among Indians in Times of COVID-19 Lockdown. Community Ment. Health J. 2021;57:42–48. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00664-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from the Korean National Health Insurance Sharing Service (NHISS) and are available at https://nhiss.nhis.or.kr (accessed on 25 January 2022) with the permission of the NHIS.