Abstract

Increased production of penicillin-binding protein PBP 4 is known to increase peptidoglycan cross-linking and contributes to methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. The pbp4 gene shares a 400-nucleotide intercistronic region with the divergently transcribed abcA gene, encoding an ATP-binding cassette transporter of unknown function. Our study revealed that methicillin stimulated abcA transcription but had no effects on pbp4 transcription. Analysis of abcA expression in mutants defective for global regulators showed that abcA is under the control of agr. Insertional inactivation of abcA by an erythromycin resistance determinant did not influence pbp4 transcription, nor did it alter resistance to methicillin and other cell wall-directed antibiotics. However, abcA mutants showed spontaneous partial lysis on plates containing subinhibitory concentrations of methicillin due to increased spontaneous autolysis. Since the autolytic zymograms of cell extracts were identical in mutants and parental strains, we postulate an indirect role of AbcA in control of autolytic activities and in protection of the cells against methicillin.

Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus primarily involves penicillin-interactive proteins, such as β-lactamases and penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), the latter being integral membrane proteins involved in the last stages of peptidoglycan biosynthesis. S. aureus possesses three high-molecular-mass PBPs (PBPs 1, 2, and 3) and one low-molecular-mass PBP, PBP 4 (15). While the high-molecular-mass PBPs are postulated to have solely transpeptidase activity (36), PBP 4 is involved in secondary cross-linking of the peptidoglycan layer and possesses transpeptidase and dd-alanine carboxypeptidase activities (21, 26, 42). Overproduction of PBP 4 and/or of PBP 2, as well as changes in their affinities to β-lactams, increases intrinsic resistance to β-lactams in susceptible strains (3, 4, 14, 18, 19, 20, 39).

Little is known about the regulation of PBP production and activity. Besides the PBP genes, other, non PBP-associated genes are postulated to contribute to intrinsic β-lactam resistance (2). The pbp4 structural gene is separated by only 400 nucleotides from a divergently transcribed gene, abcA, which codes for an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-like protein (8, 19). The ABC transporters constitute a large family of membrane transporter systems found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. They contribute to the import or export of a wide range of substances such as proteins, peptides, polysaccharides, vitamins, and drugs, utilizing ATP as the source of energy (22). The possible roles of the AbcA transporter in S. aureus are still controversial. An increase in β-lactam resistance in a PBP 4 overproducer was shown to correlate with a 90-bp deletion close to abcA in this intercistronic region. The elevated level of pbp4 transcription was paired with only an insignificantly higher level of abcA expression (19). In contrast, Domanski et al. (8, 9) showed increased levels of pbp4 transcripts in an abcA knockout mutant, suggesting that S. aureus abcA regulates PBP4 production.

To further investigate the interaction between abcA and pbp4 and their possible contribution to intrinsic β-lactam resistance in S. aureus, we studied abcA regulation and generated abcA mutants by insertional inactivation of the gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. When not mentioned otherwise, strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). Escherichia coli strain DH10B (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) and S. aureus strain RN4220 were transformed by electroporation, and transformants were selected on LB plates containing either 100 μg of ampicillin per ml or 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. S. aureus was transduced with bacteriophage 80α, and transductants were selected on LB plates containing 2.5 μg of erythromycin per ml. For S. aureus, the growth temperature was 30°C for propagating temperature-sensitive plasmids or making phage lysates and 43°C for inducing integration of the temperature-sensitive plasmids into the chromosome.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| S. aureus strain or plasmid | Genotype or descriptiona | Origin or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| RN4220 | NCTC8325-4 r− m+ restriction mutant | 27 |

| BB255 | NCTC8325, wild type | 1 |

| BB270 | NCTC8325, mec | 1 |

| GS186 | BB255 abcA::ermB, AvaI fragment of Tn551 in same transcriptional direction as abcA | This study |

| GS279 | BB255 abcA::ermB, AvaI fragment of Tn551 in opposite transcriptional direction as abcA | This study |

| GS190 | BB270 abcA::ermB, AvaI fragment of Tn551 in same transcriptional direction as abcA | This study |

| GS289 | BB270 abcA::ermB, AvaI fragment of Tn551 in opposite transcriptional direction as abcA | This study |

| BB1163 | BB255 Δagr::tet | 10 |

| BB1038 | BB255 sar::Tn917LTV | 10 |

| BB1164 | BB255 Δagr::tet sar::Tn917LTV | 10 |

| BB1165 | BB270 Δagr::tet | 10 |

| BB1030 | BB270 sar::Tn917LTV | 10 |

| BB1166 | BB270 Δagr::tet sar::Tn917LTV | 10 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTS1 | Shuttle vector; E. coli, Ampr; S. aureus, Cmr; temperature sensitive for replication | 35 |

| pGS2 | 730-bp abcA fragment and 1.8-kb AvaI fragment of Tn551 (same transcriptional direction as abcA) in pTS1 | This study |

| pGS3 | 730-bp abcA fragment and 1.8-kb AvaI fragment of Tn551 (opposite transcriptional direction as abcA) in pTS1 | This study |

Ampr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant.

DNA techniques.

Standard techniques for DNA isolation, gel electrophoresis, cloning, Southern hybridization procedures, and DNA sequencing were used (31). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany). PCR was carried out with primers synthesized by Microsynth (Balgach, Switzerland) with AmpliTaq Gold polymerase from Perkin-Elmer (Rotkreuz, Switzerland). For DNA sequencing, PCR fragments were amplified from chromosomal DNA with the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Boehringer) and sequenced with the BigDyeTerminator Ready Reaction Kit on a Perkin-Elmer 310 sequencer.

Construction of pGS2 and pGS3.

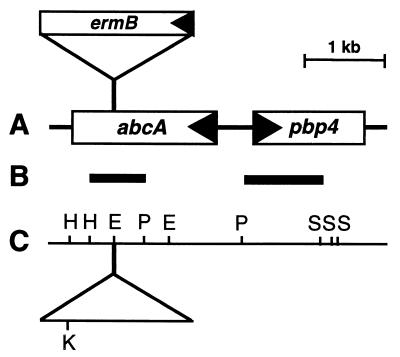

The 730-bp HindIII/PstI internal abcA fragment obtained by amplification of BB255 chromosomal DNA (Fig. 1) was cloned into pTS1 (HindIII/PstI). The ends of the 1,726-bp AvaI fragment of Tn551 (41) containing the erythromycin resistance determinant (ermB) were filled, and the fragment was blunt-end ligated into the EcoRV site of the insert. Plasmid pGS2 carries the ermB resistance determinant in the same transcriptional direction as the abcA gene (Fig. 1); plasmid pGS3 carries the determinant in the opposite direction. Both plasmids are temperature sensitive for replication in S. aureus.

FIG. 1.

(A) Physical map of the locus containing abcA and pbp4 and interruption of the abcA gene by insertion of ermB. Arrows indicate the directions of transcription. ermB, erythromycin resistance determinant. (B) Localization of hybridization probes used for Northern blots. Used were the HindIII/PstI internal abcA fragment and the PstI/Sau3A pbp4 fragment. (C) Map of restriction sites. E, EcoRV; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; P, PstI; S, Sau3A. In panels A and C the localization and transcriptional direction of ermB are shown for the mutants whose resistance determinant was inserted in the same transcriptional direction as the abcA gene.

Plasmid-mediated insertional inactivation.

S. aureus strain RN4220 was transformed with pGS2 or pGS3 and subsequently used as a donor for transduction of BB255 and BB270. Transductants were selected on LB broth containing 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml at 30°C. For plasmid-mediated insertional inactivation, transductants were grown overnight in LB broth containing 2.5 μg of erythromycin per ml at 30°C, diluted 100-fold, and incubated until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the cells was 0.1. Aliquots were then plated on 2.5 μg of erythromycin per ml and incubated at 43°C for 48 h. Colonies were tested for growth on 5 μg of chloramphenicol per ml and 2.5 μg of erythromycin per ml. Clones which were sensitive to chloramphenicol and resistant to erythromycin were assumed to have been subject to a double crossover with subsequent loss of the plasmid. They were tested for insertional inactivation of the abcA gene by PCR and Southern hybridization, and positive clones were verified by DNA sequencing.

Antibiotic susceptibility tests.

Antibiotic susceptibility was determined by the E-test (AB BIODISK, Solna, Sweden) on Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco) after 24 h of incubation at 35°C. Population analysis profiles were established by plating aliquots of an overnight culture on increasing concentrations of methicillin and determining the CFU after 48 h of incubation at 37°C. Susceptibilities to lysostaphin (AMBI, Trowbridge, United Kingdom) and to daptomycin in the presence of 50 mg of Ca2+ per liter (a gift from J. Silverman, Cubist Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cambridge, Mass.) were tested by broth microdilution.

Measurement of autolysis.

Unstimulated and Triton X-100-stimulated autolysis was measured as described by Gustafson et al. (16). Cells were grown in PYK medium (5.0 g of Bacto Peptone, 5.0 g of yeast extract, and 3.0 g of K2HPO4 per liter at pH 7.2) to mid-exponential phase at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm). After centrifugation, cells were washed with cold double-distilled water, resuspended in 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer (unstimulated) or 0.05 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer containing 0.05% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 (stimulated) in spectrophotometer vials, and incubated with shaking (200 rpm) at 30°C. The decrease in OD580 was measured every 30 min.

Autolytic activities in cell extracts were analyzed in a zymogram using BB255 cell walls as described by Berger-Bächi et al. (2).

Northern blot analysis.

A 1% (vol/vol) inoculum of an overnight culture was used to initiate growth of bacterial cells in LB broth at 37°C. Methicillin was added to the medium at time of inoculation, and cells were harvested in the exponential growth phase. RNA was isolated as described by Kullik and Giachino (28). Northern hybridization procedures were performed as described by Münch (33). The hybridization probe was either the HindIII/PstI internal abcA fragment or the PstI/Sau3A pbp4 fragment (Fig. 1) of BB255 which was cloned into pBLSK(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and transcribed in vitro with the T3 and T7 RNA polymerases and the DIG RNA Labeling Mix (Boehringer) according to the suppliers protocol.

RESULTS

Analysis of abcA and pbp4 expression in parental strains.

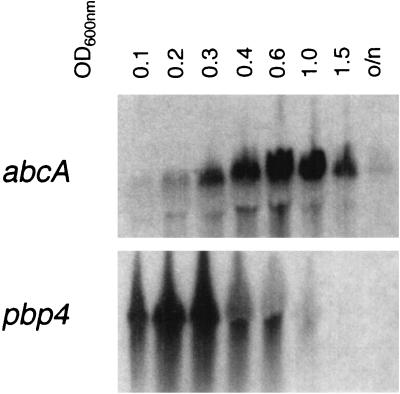

The function of the AbcA transporter in S. aureus is still unknown. Because of the proximity of abcA to pbp4, which has been shown to be involved in methicillin resistance (20), abcA may also contribute to antibiotic resistance. Domanski et al. (9) showed that the regions of the transcriptional starts of both genes overlap, suggesting a common regulatory mechanism. Therefore, we wanted to get more information about the regulation of abcA and pbp4. Analysis of abcA- and pbp4-specific RNAs during the growth cycle of BB255 revealed different expression patterns for the two genes (Fig. 2). While abcA expression reached its maximum at an OD600 of 0.6, pbp4 expression was already at its maximum in the early exponential phase at an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.3. The same expression maximum for pbp4 during the growth cycle was also observed in the abcA mutants GS186 and GS190 (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from BB255 cells at different OD600s during the growth cycle. Blots were hybridized with probes specific for abcA or pbp4 (Fig. 1B). o/n, overnight culture.

Expression of abcA in agr and sar mutants.

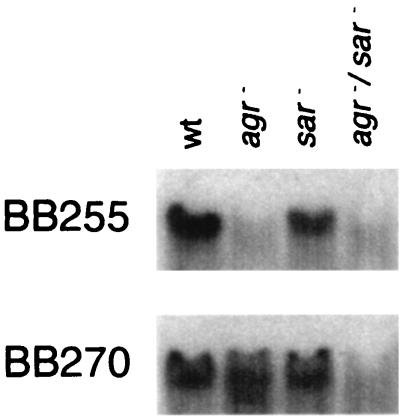

The global regulatory systems agr and sar are involved in regulation of virulence determinants in S. aureus (5, 34, 38). While the polycistronic locus agr is known to control toxin and exoprotein production (34), the locus sar was shown to be necessary for the optimal expression of agr (6). RNAs of agr deletion, sar, and agr sar double mutants derived from BB255 (BB1163, BB1038, and BB1164, respectively) and from BB270 (BB1165, BB1030, and BB1166, respectively) were isolated and analyzed in a Northern blot in regard to the expression of abcA. abcA-specific transcripts were reduced in agr and agr sar double mutants and to a lesser extent in the corresponding sar mutants (Fig. 3). The effect of agr on abcA transcription could be confirmed in other, nonrelated agr mutants (data not shown). Therefore, we deduced that the abcA transcription is under the control of the global regulator agr. In contrast, agr and sar had neither an effect on pbp4 transcription (data not shown) nor an effect on the PBP 4 protein level (37).

FIG. 3.

Northern blot analysis of different agr and sar mutants derived from BB255 (wild type [wt], BB255; agr−, BB1163; sar−, BB1038; agr−/sar−, BB1164) and BB270 (wt, BB270; agr−, BB1165; sar−, BB1030; agr−/sar−, BB1166). RNA was isolated from exponentially growing cells harvested at an OD600 of 0.4 and hybridized with an abcA-specific probe (Fig. 1B).

Insertional inactivation of abcA.

To study the role of the AbcA transporter in methicillin resistance, we created an abcA insertion mutant by introducing the erythromycin resistance determinant of Tn551 (ermB) in both transcriptional directions into the abcA genes of the methicillin-sensitive strain BB255 and the methicillin-resistant strain BB270 (Fig. 1A). To test the stability of the insertion and to cure the strains of any remaining plasmid molecules, backcrossings into parental strains were performed. The insertion and orientation of the erythromycin determinant within the abcA gene were verified by PCR, Southern hybridization, and DNA sequencing (data not shown). DNA sequencing of the mutants thus obtained revealed no relevant changes, either in the intercistronic region, in the region of the junctions, or in the parts of the abcA gene surrounding the ermB resistance determinant, compared to the parental strains.

Analysis of abcA and pbp4 expression in abcA mutants.

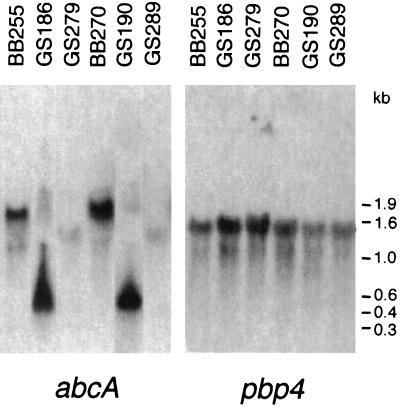

Interruption of the abcA gene was performed primarily by insertion of the erythromycin resistance determinant in the same transcriptional direction as the abcA gene, resulting in mutant strains GS186 and GS190. This was to exclude any effects on the neighboring pbp4 gene. Northern blot analysis of the RNAs isolated from those mutants using an internal abcA probe revealed a transcription product of approximately 600 nucleotides (Fig. 4). Because the intact abcA gene has a length of approximately 1,700 nucleotides, this shorter product cannot lead to a functionally active AbcA transporter protein. DNA sequencing analysis revealed that this shorter fragment was probably due to an abcA-specific transcription product originating from a start codon within the abcA sequence and driven by the promoter for ORF4 of Tn551 (41). When ermB was inserted in the opposite direction, in strains GS279 and GS289, no abcA gene products were observed (Fig. 4). Independent of the transcriptional direction of the ermB insert, the abcA inactivation had essentially no effects on pbp4 transcription (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Northern blot analysis. RNAs were isolated from exponentially growing parental strains (BB255 and BB270) and their corresponding abcA mutants (GS186, GS279, GS190, and GS289) harvested at an OD600 of 0.4 and hybridized with abcA- or pbp4-specific probes (Fig. 1B).

Susceptibility to methicillin and other antibiotics.

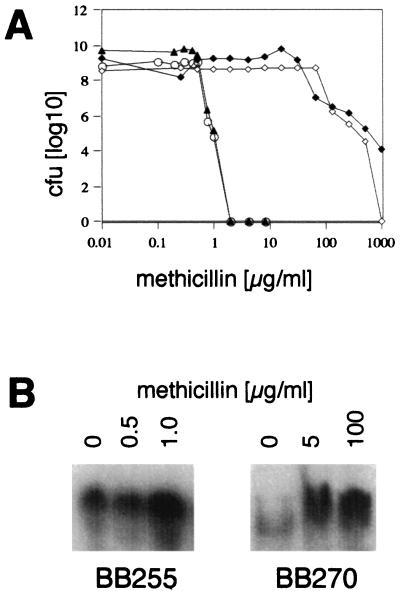

To test the role of the AbcA transporter in antibiotic resistance, the susceptibilities of the abcA mutant strains GS186 and GS190 and their parental strains BB255 and BB270 to different commonly used cell wall- and membrane-directed antibiotics, like oxacillin, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, imipenem, vancomycin, teicoplanin, lysostaphin, and daptomycin, were tested, and these were shown to be identical in mutant and parental strains (Table 2). In addition, in a lysostaphin sensitivity assay performed as described by Domanski et al. (9), no differences between the mutant and parental strains were observed (data not shown). MICs of methicillin as well as exposure to increasing concentrations of methicillin in the population analysis did not reveal any differences, suggesting no direct involvement of the AbcA transporter in methicillin resistance (Fig. 5A). However, although the population analysis showed identical numbers of parental and mutant cells at different concentrations of methicillin, major portions of the colonies of mutants GS186 and GS190 were subject to cell lysis. Lysis in GS186 and GS190 started in presence of 0.3 and 16 μg of methicillin per ml, respectively, whereas in BB255 and BB270 slight lysis was observed only at the highest concentrations of 1 and 1,000 μg of methicillin per ml, respectively.

TABLE 2.

MICs of cell wall-directed antibiotics

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) for strain:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BB255 | GS186 | BB270 | GS190 | |

| Methicillina | 0.5 | 0.5 | >256 | >256 |

| Oxacillina | 0.125 | 0.094 | >256 | >256 |

| Cefoxitina | 1 | 1 | >256 | >256 |

| Cefotaximea | 0.5 | 0.5 | >256 | >256 |

| Imipenema | 0.012 | 0.006 | 32 | 32 |

| Vancomycina | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Teicoplanina | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Daptomycinb | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Lysostaphinb | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

MICs were determined by the E-test.

MICs were determined by a broth microdilution test.

FIG. 5.

Treatment with methicillin. (A) Population analysis profiles of parental strains BB255 and BB270 and the corresponding abcA mutants GS186 and GS190 on increasing concentrations of methicillin. The CFU were determined after 48 h of incubation at 37°C. Symbols: ⧫, BB270; ◊, GS190; ▴, BB255; ○, GS186. (B) Analysis of RNAs isolated from BB255 and BB270 growing in the presence of different concentrations of methicillin and harvested in the exponential phase at an OD600 of 0.6. Growing cells of BB255 reached an OD600 of 0.6 after 2.5 h (control, 0.5 μg of methicillin per ml) and 3.5 h (1.0 μg of methicillin per ml); those of BB270 reached this OD600 after 3 h (control, 5 μg of methicillin per ml) and 4 h (100 μg of methicillin per ml). Northern blots were hybridized with an abcA-specific probe (Fig. 1B).

To further investigate the effects of methicillin, we exposed the methicillin-sensitive strain BB255 and the resistant strain BB270 to different concentrations of methicillin and analyzed abcA expression by Northern blotting. In BB255, as well as in BB270, abcA expression was induced by increasing concentrations of methicillin (Fig. 5B), while pbp4 expression remained unaffected (data not shown). Induction was obtained only after 3 h of exposure of the culture to methicillin. Treatment with the drug for only 30 min produced no differences in abcA expression levels compared to the untreated cells (data not shown). Exposure of growing cells of the parental strains to lysostaphin, vancomycin, or daptomycin, whose target is the cell wall, did not show any effects on abcA transcription (data not shown).

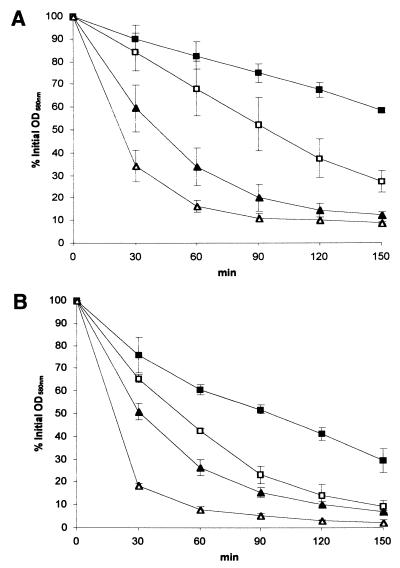

Autolysis experiments.

Since population analysis showed that a major portion of abcA mutant colonies started to lyse at subinhibitory concentrations of methicillin, we investigated whether inactivation of abcA leads to changes in autolytic properties. Unstimulated as well as Triton X-100-stimulated spontaneous whole-cell autolysis was faster in GS186 and GS190 than in the corresponding parental strains BB255 and BB270 (Fig. 6). Increased autolysis was independent of the orientation of the ermB insertion (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Unstimulated and Triton X-100-stimulated spontaneous autolysis of the mutant GS186 and its parental methicillin-sensitive strain BB255 (A) as well as of the mutant GS190 and its parental methicillin-resistant strain BB270 (B). Each value represents the mean from three independent experiments; the standard deviations are indicated by error bars. Squares, BB255 (A) or BB270 (B); triangles, GS186 (A) or GS190 (B). Unstimulated autolysis is represented by closed symbols, and Triton X-100-stimulated autolysis is represented by open symbols.

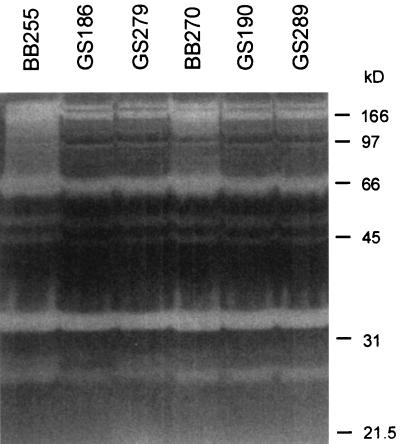

Although spontaneous autolysis differed, zymograms showed no apparent differences in autolytic enzyme patterns in all strains tested (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Autolysin zymograms in a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel containing BB255 cell walls. The autolytic banding patterns of BB255 and BB270 and their corresponding abcA mutants were compared. Samples were prepared from cells grown to an OD600 of 1.0. Protein was added to each lane at a final amount of 10 μg.

DISCUSSION

Overproduction of PBP 4 leads to increased peptidoglycan cross-linking and methicillin resistance in S. aureus (9, 14, 19, 21, 42). The postulated regulatory link between transcription of pbp4 and abcA (8, 9), resulting in pbp4 overexpression upon abcA inactivation, could not be confirmed in this study. Inactivation of abcA by ermB inserted either in the same or the opposite direction with respect to abcA transcription had no effect on pbp4 transcription and resistance and no effect on peptidoglycan cross-linking (K. Ehlert, personal communication). The overexpression of pbp4 transcription in the abcA knockout mutant of Domanski et al. (8, 9) may therefore have been due to a cloning artifact introduced by the inserted plasmid.

The different expression patterns of abcA and pbp4 observed during growth suggest them to be regulated independently. pbp4 transcription peaked in the early growth phase, whereas transcription of abcA reached its maximum later in the exponential growth phase. Moreover, transcription of abcA was reduced in agr mutants and to a lesser extent in sar mutants, whereas pbp4 seemed not to be affected. The global regulators agr and sar have formerly been reported to affect penicillin-induced killing (13). The MICs and sensitivity tests against methicillin revealed no measurable quantitative effects of abcA inactivation on methicillin resistance. However, the lysis of a large portion of abcA mutant colonies on plates at subinhibitory concentrations of methicillin indicate that AbcA transporter mutants respond differently, with delayed lysis, to methicillin stress. Interesting in this context was the elevated abcA transcription triggered by exposure to methicillin, suggesting a protective role of AbcA against methicillin.

The observation that abcA mutants clearly showed higher rates of spontaneous cell autolysis despite identical autolytic enzyme patterns hints at an indirect role of AbcA on autolytic activities. The mechanisms which regulate endogenous and β-lactam-induced lysis are not yet known. Lipoteichoic acids and wall teichoic acids have been proposed to modify the cell wall autolytic enzymes through the degree of d-alanine ester substitution (7, 12, 17, 23, 24, 25, 29, 30). In preliminary experiments, decreased d-alanine contents of lipoteichoic acids, as well as of wall teichoic acids, in the abcA mutant of BB255 but not in that of BB270 were observed (K. Schubert, personal communication). Increased spontaneous autolysis in abcA mutants may therefore not directly be due to a change in d-alanine ester substitution. However, support for a possible interaction between the AbcA transporter and wall teichoic acids comes from database searches (The Institute for Genomic Research, Sanger Centre) that reveal the genes tagD, tagX, tagB, tag permease, tagH, and tagA located downstream of pbp4; these are genes involved in teichoic acid biosynthesis. Additionally, 360 bp downstream of abcA is a gene for a putative transporter protein showing 44.8% similarity with a hypothetical nucleoside uptake protein of Bacillus subtilis, followed by, among others, genes for a ferrichrome transport protein and a d-alanine glycine transporter.

ABC transporters can be divided into two groups. Transporters appear to function only in export when the membrane-spanning and ATP-binding domains are located on a single polypeptide, whereas they can facilitate import or export when the two domains are located on separate polypeptides (11). The AbcA transporter would therefore belong to the first group, probably being an exporter. Support for the function of AbcA as an exporter comes from the comparison with other known transporter proteins. The AbcA protein shows 77% similarity and 56% identity to PepT of Staphylococcus epidermidis, a transporter involved in Pep5 lantibiotic export (32), and 65% similarity, 39% identity to LmrA of Lactobacillus lactis, which is responsible for drug efflux (40). Many of the ABC exporters require additional proteins to form a functional complex. The genes for these additional factors, which have been identified in several gram-negative systems, are usually found linked to the gene encoding the ABC protein (11), which in this case would be the putative nucleoside uptake protein.

Although our study gave new hints about the possible function of the AbcA transporter in S. aureus, its exact role in cell metabolism remains unknown. The interesting finding that abcA transcription is dependent on the agr system calls for further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grant 3-52059.97.

We thank Sibylle Burger for DNA sequencing, Kerstin Ehlert (Bayer AG, Wuppertal, Germany) for analyzing peptidoglycan cross-linking, and Karin Schubert (University of München, Munich Germany) for determination the d-alanine ester substitution of wall teichoic acids and lipoteichoic acids.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger-Bächi B, Kohler M L. A novel site on the chromosome of Staphylococcus aureus influencing the level of methicillin resistance: genetic mapping. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;20:305–309. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger-Bächi B, Strässle A, Gustafson J E, Kayser F H. Mapping and characterization of multiple chromosomal factors involved in methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1367–1373. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger-Bächi B, Strässle A, Kayser F H. Characterization of an isogenic set of methicillin-resistant and susceptible mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1986;5:697–701. doi: 10.1007/BF02013308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers H F, Sachdeva M J, Hackbarth C J. Kinetics of penicillin binding to penicillin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem J. 1994;301:139–144. doi: 10.1042/bj3010139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung A L, Koomey J M, Butler C A, Projan S J, Fischetti V A. Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus (sar) distinct from agr. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6462–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung A L, Projan S J. Cloning and sequencing of sarA of Staphylococcus aureus, a gene required for the expression of agr. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4168–4172. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.13.4168-4172.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleveland R F, Daneo-Moore L, Wicken A J, Shockman G D. Effect of lipoteichoic acid and lipids on lysis of intact cells of Streptococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:1582–1584. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1582-1584.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domanski T L, Bayles K W. Analysis of Staphylococcus aureus genes encoding penicillin-binding protein 4 and an ABC-type transporter. Gene. 1995;167:111–113. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)82965-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domanski T L, De Jonge B L M, Bayles K W. Transcription analysis of the Staphylococcus aureus gene encoding penicillin-binding protein 4. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2651–2657. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2651-2657.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duran S P, Kayser F H, Berger-Bächi B. Impact of sar and agr on methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;141:255–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fath M J, Kolter R. ABC transporters: bacterial exporters. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:995–1017. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.995-1017.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer W, Rösel P, Koch H U. Effect of alanine ester substitution and other structural features of lipoteichoic acids on their inhibitory activity against autolysins of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:467–475. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.2.467-475.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimoto D F, Bayles K W. Opposing roles of the Staphylococcus aureus virulence regulators, agr and sar, in Triton X-100- and penicillin-induced autolysis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3724–3726. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.14.3724-3726.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georgopapadakou N H, Cummings L M, La Sala E R, Unowsky J, Pruess D L. Overproduction of penicillin-binding protein 4 in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with methicillin resistance. In: Actor P, Daneo-Moore L, Higgins M L, Salton M-R J, Shockman G D, editors. Antibiotic inhibition of bacterial cell surface assembly and function. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1988. pp. 597–602. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgopapadakou N H, Liu F Y. Binding of β-lactam antibiotics of penicillin-binding proteins of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus faecalis: relation to antibacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;18:834–836. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.5.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gustafson J E, Berger-Bächi B, Strässle A, Wilkinson B J. Autolysis of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:566–572. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.3.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haas R, Koch H U, Fischer W. Alanyl turnover from lipoteichoic acid to teichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1984;21:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hackbarth C J, Kocagoz T, Kocagoz S, Chambers H F. Point mutations in Staphylococcus aureus PBP 2 gene affect penicillin-binding kinetics and are associated with resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:103–106. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henze U U, Berger-Bächi B. Penicillin-binding protein 4 overproduction increases beta-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2121–2125. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henze U U, Berger-Bächi B. Staphylococcus aureus penicillin-binding protein 4 and intrinsic beta-lactam resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2415–2422. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henze U U, Roos M, Berger-Bächi B. Effects of penicillin-binding protein 4 overproduction in Staphylococcus aureus. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:193–199. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins C F. ABC transporters: from microorganism to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Höltje J-V, Tomasz A. Lipoteichoic acid: a specific inhibitor of autolysin activity in Pneumococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1690–1694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes A H, Hancock I C, Baddiley J. The function of teichoic acids in cation control in bacterial membranes. Biochem J. 1973;132:83–93. doi: 10.1042/bj1320083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koch H U, Doker R, Fischer W. Maintenance of d-alanine ester substitution of lipoteichoic acid by reesterification in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:1211–1217. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.3.1211-1217.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozarich J W, Strominger J L. A membrane enzyme from Staphylococcus aureus which catalyses transpeptidase, carboxypeptidase and penicillase activities. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:1272–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreiswirth B N, Löfdahl S, Bentley M J, O'Reilly M, Schlievert P M, Bergdoll M S, Novick R P. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:680–685. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kullik I, Giachino P. The alternative sigma factor sigmaB in Staphylococcus aureus: regulation of the sigB operon in response to growth phase and heat shock. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:151–159. doi: 10.1007/s002030050428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kullik I, Jenni R, Berger-Bächi B. Sequence of the putative alanine racemase operon in Staphylococcus aureus: insertional interruption of this operon reduces d-alanine substitution of lipoteichoic acid and autolysis. Gene. 1998;219:9–17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00404-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert P A, Hancock I C, Baddiley J. Influence of alanyl ester residues on the binding of magnesium ions to teichoic acids. Biochem Z. 1975;51:671–676. doi: 10.1042/bj1510671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J E. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyer C, Bierbaum G, Heidrich C, Reis M, Suling J, Iglesias-Wind M, Kempter C, Molitor E, Sahl H. Nucleotide sequence of the lantibiotic Pep5 biosynthetic gene cluster and functional analysis for a role of PepC in thioether formation. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232:478–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Münch S. Nonradioactive Northern blots in 1.5 days and with substantially increased sensitivity through “alkaline blotting.”. Biochemica. 1994;3:30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Novick R P, Ross H F, Projan S J, Kornblum J, Kreiswirth B, Moghazeh S. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 1993;12:3967–3975. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Connell C, Pattee P A, Foster T J. Sequence and mapping of the aroA gene of Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1449–1460. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-7-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park W, Matsuhashi M. Staphylococcus aureus and Micrococcus luteus peptidoglycan transglycosylases that are not penicillin-binding proteins. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:538–544. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.538-544.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piriz-Duran, S., F. H. Kayser, and B. Berger-Bächi. Impact of sar and agr on methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 141:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Tegmark K, Morfeldt E, Arvidson S. Regulation of agr-dependent virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus by RNAIII from coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3181–3186. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3181-3186.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomasz A, Drugeon H B, de Lencastre H M, Jabes D, McDougall L. New mechanism for methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: clinical isolates that lack the PBP 2a gene and contain normal penicillin-binding proteins with modified penicillin-binding capacity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1869–1874. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Veen H W, Venema K, Bolhuis H, Oussenko I, Kok J, Poolman B, Driessen A J M, Konings W N. Multidrug resistance mediated by a bacterial homolog of the human multidrug transporter MDR1. Biochemistry. 1996;93:10668–10672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu S W, De Lencastre H, Tomasz A. The Staphylococcus aureus transposon Tn551: complete nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the expression of the erythromycin resistance gene. Microb Drug Resist. 1999;5:1–7. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1999.5.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wyke A W, Ward J B, Hayes M V, Curtis C A M. A role in vivo for penicillin-binding protein-4 of Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Biochem. 1981;119:389–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1981.tb05620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]