Abstract

The multi-system of electro-phytotechnology using a woody ornamental cadmium (Cd) hyperaccumulator (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) is a new departure for environmental remediation. The effects of four electric field conditions on Cd accumulation, growth, and photosynthesis of L. japonica under four Cd treatments were investigated. Under 25 and 50 mg L−1 Cd treatments, Cd accumulation in L. japonica was enhanced significantly compared to the control and reached 1110.79 mg kg−1 in root and 428.67 mg kg−1 in shoots influenced by the electric field, especially at 2 V cm−1, and with higher bioaccumulation coefficient (BC), translocation factor (TF), removal efficiency (RE), and the maximum Cd uptake, indicating that 2 V cm−1 voltage may be the most suitable electric field for consolidating Cd-hyperaccumulator ability. It is accompanied by increased root and shoots biomass and photosynthetic parameters through the electric field effect. These results show that a suitable electric field may improve the growth, hyperaccumulation, and photosynthetic ability of L. japonica. Meanwhile, low Cd supply (5 mg L−1) and medium voltage (2 V cm−1) improved plant growth and photosynthetic capacity, conducive to the practical application to a plant facing low concentration Cd contamination in the real environment.

Keywords: electric fields, cadmium, Lonicera japonica Thunb., hyperaccumulator, phytoremediation

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of industrialization and urbanization in the past few decades, a growing number of heavy metals are deposited in soil, mainly derived from mining activities, vehicle emissions, and industrial dust, have caused severe harm to human health and the environment [1,2,3,4,5]. Among those heavy metals, cadmium (Cd), one of the most toxic pollutants, has become a global concern due to its high persistency, strong water-solubility, and potential carcinogenicity [6,7,8,9,10]. Soil Cd exceeding the environmental standard not only poses great harm to plants, including leaf chlorosis, growth inhibition, stomatal closure, and photosynthesis inhibition but threatens human health through the food chains [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. It is consequently urgent to develop a more efficient technique for removing Cd from contaminated soils [18].

Phytoremediation—hyperaccumulator or accumulator absorption of toxic heavy metals from soils to plant organs—has become a promising technique that is inexpensive, easily applied, and eco-friendly [19,20,21]. The hyperaccumulators have been considered to extract and accumulate Cd above 0.01% dry tissue (100 μg g−1) [22,23,24]. However, phytoremediation also shows such typical limitations in practice as deep treatment zone, long-time consumption, and low bioavailability of soil pollutants [25,26]. Recently, the combination of phytoremediation and electrokinetic remediation has increasingly been used to overcome the limitations of phytoremediation and enhance remediation efficiency [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Some studies have reported that the application of electric fields could improve the bioavailability of pollutants in soils and heavy metal accumulation in plants [28,33,34,35], and other studies investigated electric field-assisted enhancements in seed germination, plant growth, and self-organization ability under different environmental stress [36,37,38,39,40]. Nevertheless, these studies were mainly focused on crops, herbs, and aquatic plants, including lettuce, maize, tomato, ryegrass, and Canadian waterweed [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Early researchers indicated Cd-induced changes in photosynthesis, such as net photosynthesis (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), and transpiration rate (Tr) [49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. However, little information is available on the electric field-assisted effects on the characteristics of cadmium accumulation and photosynthesis in woody ornamental hyperaccumulators.

Nowadays, more and more ornamental plants are widely used for gardening and greening across the human living environment [57,58,59]. Ornamental plants not only clean up the soil contaminated by heavy metals but also contribute to the beautification and decoration of the living environment [60,61]. Lonicera japonica Thunb.—a popular woody ornamental plant—has become established in temperate and tropical regions worldwide in the past 150 years [62]. The plant has the characteristics of easy cultivation, high biomass, wide geographic distribution, and strong resistance to environmental stress [63]. L. japonica was chosen in the study based on our previous findings, which showed that it is a new-found woody Cd-hyperaccumulator [53,64,65]. Therefore, in the present study, we selected L. japonica as a model plant to show the effect of different electric fields on Cd accumulation and transport, and investigate the responses of plant growth and photosynthesis under different Cd concentrations. The specific objectives are to confirm the phytoremediation potential of a woody ornamental Cd-hyperaccumulator assisted by electric fields and develop a practical multi-system of electro-phytotechnology used to prevent contaminated soils.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Cultivation and Treatments

Seedlings of L. japonica were collected from the non-contaminated experimental field of Shenyang Agricultural University and propagated in sterilized sand with a nutrient medium. The nutrient medium was Hoagland solution modified by the following composition (mmol L−1): Ca(NO3)2 × 4 H2O 5.00, MgSO4 × 7 H2O 2.00, KNO3 5.00, KH2PO4 1.00, H3BO3 0.05, ZnSO4 × 7 H2O 0.80 × 10−3, MnCl2 × 4 H2O 9.00 × 10−3, CuSO4 × 5 H2O 0.30 × 10−3, (NH4)6Mo7O24 × 4 H2O 0.02 × 10−3, Fe-EDTA 0.10 [64,66]. The pH was adjusted daily to 5.8 ± 0.1 with HCl or NaOH. The plants were grown in a greenhouse of Shenyang Agricultural University at 23 ± 2 °C (800–1000 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD, 16/8 h light/dark, 70–80% relative humidity).

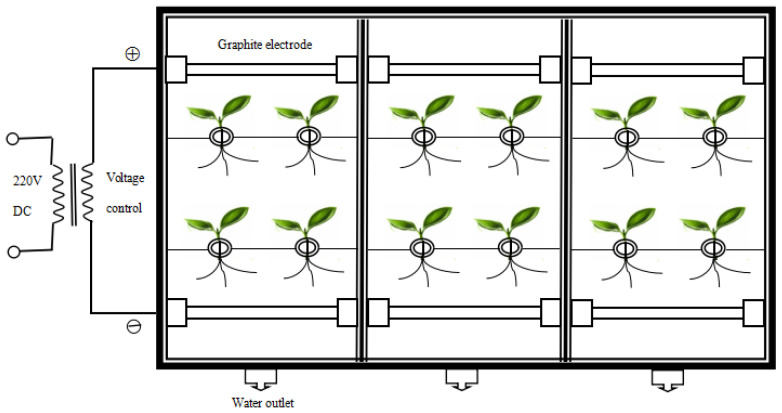

After 8 weeks of cultivation, L. japonica were transferred into adumbral containers (45 × 22 × 15 cm3) with 6 L Hoagland nutrient medium, 4 plants for each. The nutrient medium was renewed once every 3 days. Subsequently, Cd2+ (CdCl2 × 2.5 H2O, Kermel Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China, >99%) was added into the nutrient medium to get: 0, 5, 25 and 50 (mg L−1), respectively. Additionally, a homogeneous electric field with a pair of graphite electrodes (10.0 cm length, R = 3 mm) connected to a DC power supply (220 V, 50 Hz) was applied for 6 h per day, and the electrical setting of the experiment is shown in Figure 1. The voltage gradients of 0, 1, 2, and 3 (V cm−1) are shown in Table 1. The experiment was repeated 3 times, and the plants were harvested 1 week later for analysis.

Figure 1.

The electrical setting of the experiment.

Table 1.

Various experimental treatments.

| Treatment | Test Number | Voltage Gradient (V cm−1) | Cd Concentration in the Medium (mg L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | V0-Cd0 | 0 | 0 |

| T2 | V0-Cd5 | 0 | 5 |

| T3 | V0-Cd25 | 0 | 25 |

| T4 | V0-Cd50 | 0 | 50 |

| T5 | V1-Cd0 | 1 | 0 |

| T6 | V1-Cd5 | 1 | 5 |

| T7 | V1-Cd25 | 1 | 25 |

| T8 | V1-Cd50 | 1 | 50 |

| T9 | V2-Cd0 | 2 | 0 |

| T10 | V2-Cd5 | 2 | 5 |

| T11 | V2-Cd25 | 2 | 25 |

| T12 | V2-Cd50 | 2 | 50 |

| T13 | V3-Cd0 | 3 | 0 |

| T14 | V3-Cd5 | 3 | 5 |

| T15 | V3-Cd25 | 3 | 25 |

| T16 | V3-Cd50 | 3 | 50 |

2.2. Measurements of Photosynthetic Parameters

Photosynthetic parameters were measured in fully expanded leaves under the electric field using a portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400, Li-Cor Inc. Lincoln, NE, USA). The photosynthetic parameters contained net photosynthetic rate (Pn, μmol m−2 s−1), stomatal conductance (Gs, mol m−2 s−1), transpiration rate (Tr, mmol m−2 s−1), and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci, µL L−1). Light level, CO2 concentration, and leaf temperature inside the leaf chamber were kept constant at 1000 μmol m−2 s−1 PPFD, 25 ± 0.3 °C, and 380 ± 5 μmol CO2 mol−1, respectively. Eight leaves per treatment were used for the determination.

2.3. Assays of Plant Biomass and Cd Content

After harvesting, L. japonica were washed with tap water, and the plant roots were immersed in 20 mM Na2-EDTA for 15 min and then rinsed with tap and de-ionized water to remove Cd adhering to the root surface. The plants were separated into shoots and roots. These portions were then dried at 105 °C for 20 min, then at 70 °C until a constant weight was reached. Afterward, root and shoots biomass dry weight was obtained.

Dried plant materials were ground to a fine powder. The powders were digested with a concentrated acid mixture of HNO3/HClO4 (3:1, v/v). The Cd concentration in plant tissues was determined using an atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS 3110 Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.4. Data Analysis

The bioaccumulation coefficient (BC) indicated the ability of plants to accumulate cadmium in the medium. It was shown as:

| (1) |

The translocation factor (TF) reflected the different abilities of plants to translocate cadmium from a different portion of plants. It was described as:

| (2) |

To assess the effects of cadmium on phytoextraction by plants, the removal efficiency (RE) was described as [19,67].

| (3) |

where Metalshoot is the contents (mg kg−1) of cadmium in the harvested shoots of plants; Metalmedium is the initial cadmium content (mg kg−1) of the medium; Massshoot and Massmedium are the masses (g) of the shoots and medium of the harvested plants, respectively.

The cadmium uptake was measured as [65].

| (4) |

where M1 and M2 are the cadmium concentrations in the plant tissue, and W1 and W2 are the plant biomass at time T1 (initial sampling) and T2 (final sampling).

2.5. Statistical Analyses

All experimental measurements were set for three replicates. Average values and standard deviations (SD) were calculated by Microsoft Office Excel 2016 for all the data in the present study. The experimental data were presented as the means ± SD. The statistical analysis of variance was carried out with the SPSS 22.0 software tool. The significant difference was performed between treatments at p < 0.05. Multiple comparison was also determined using the least significant difference (LSD) test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Effect of Electric Field on Cd Accumulation in Plants

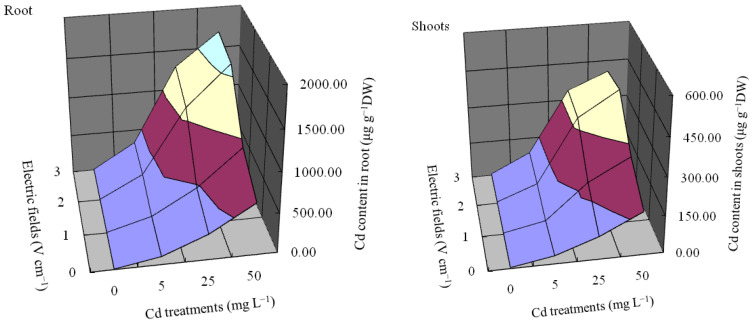

Under different treatments, Cd accumulation in roots and shoots of L. japonica was shown in Figure 2. Under T1–T4 treatments (under Cd stress without electric field), Cd concentration in roots had a slightly increasing trend which ranged from 103.72 to 657.58 mg kg−1. Under T5–T16 treatments, the electric field significantly enhanced the concentrations of Cd in roots compared with the control, especially exposed to high concentrations (25 and 50 mg L−1) Cd. The Cd concentrations in roots were enhanced significantly by 2 and 3 V cm−1 voltages, which reached 1110.79 and 1608.24 mg kg−1 (T11 and T12), 1291.95 and 1692.37 mg kg−1 (T15 and T16), respectively. Despite that, Cd concentrations in shoots were enhanced significantly in the electric field. The different voltages promoted Cd concentrations in shoots above 180 mg kg−1 under 25 and 50 mg L−1 Cd stress. The maximum Cd concentrations in shoots increased by 2 V cm−1 voltage (exposed to 50 mg L−1 Cd) were added to 428.67 mg kg−1, 2.44 times of T4 treatment (V0-Cd50). Other studies also reported that heavy metal (Cd, Cu, Zn, and Pb) concentrations in plants increased with the application of an electric field [29,68]. The beneficial effect of the electric field may be associated with the changes in cell membrane properties and metal ions polarity inside plants [42,45]. Our present study is in agreement with the observation of [35,46], which showed that electric fields could enhance the rate of membrane polarization and cell metabolism, which accelerate heavy metal transport by activating ion channels such as Ca2+ into cytosol and enzyme cascades.

Figure 2.

The relationship of different treatments and Cd contents in roots and shoots of L. japonica. Values represent the mean.

3.2. The Effect of Electric Field on Hyperaccumulation Characteristics

The measured results of the bioaccumulation coefficient (BC), translocation factor (TF), removal efficiency (RE), and heavy metal uptake are shown in Table 2. The values of BC, TF, RE, and heavy metal uptake refer to the plant’s characteristic to absorb metal elements from the soil, then transfer, mobilize and store these elements in plant tissues [38,47,69,70,71,72]. Therefore, these results, including BC, TF, RE, and Cd uptake, are very important to understanding the action of ion exchange in the soil environment and hyperaccumulation characteristics in the tissues of L. japonica. The electric fields enhanced root BC significantly and shoots BC of L. japonica exposed to different concentrations of Cd compared with T1–T4 treatments (under Cd stress without electric fields). Under different concentrations of Cd stress, root BC and shoots BC were promoted significantly by 2 V cm−1 voltage and 3 V cm−1 voltage, which reached above 32.16 (T12) and 8.11 (T16). When exposed to higher concentrations of Cd, the TF of the plants was enhanced significantly by 1 V cm−1 voltage and 2 V cm−1 voltage. Exposed to 5 mg L−1 Cd stress, the RE of the plants was increased from 14.02 under no voltage (T2) treatment to 36.78 under 3 V cm−1 voltage treatment (T14). With the increase of Cd concentration in the medium, the maximum RE in the plants was 4.00 and 2.61 times of T3 (V0-Cd25) and T4 treatment (V0-Cd50). Compared with the treatments (under Cd stress without electric field), different voltages enhanced the uptake of Cd in the plants exposed to different concentrations of Cd. The maximum Cd uptake of the plants reached 53.02 μg plant−1 day−1 promoted by 2 V cm−1 voltage (T11).

Table 2.

The effect of electric field on Cd hyperaccumulation characteristics of L. japonica.

| Treatment | Test Number | Root BC | Shoots BC | TF | RE | Uptake (μg plant−1 day−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | V0-Cd0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| T2 | V0-Cd5 | 20.74 a | 6.74 ab | 0.33 a | 14.02 ab | 5.43 abc ± 0.04 |

| T3 | V0-Cd25 | 13.04 b | 3.72 c | 0.29 bc | 7.39 c | 10.68 d ± 0.08 |

| T4 | V0-Cd50 | 13.15 b | 3.51 d | 0.27 d | 6.87 d | 14.68 ef ± 0.06 |

| T5 | V1-Cd0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| T6 | V1-Cd5 | 31.85 cd | 7.94 cde | 0.25 b | 18.18 ef | 8.95 de ± 0.05 |

| T7 | V1-Cd25 | 18.92 e | 7.27 ab | 0.38 a | 15.37 ab | 20.86 g ± 0.12 |

| T8 | V1-Cd50 | 18.61 e | 5.40 e | 0.29 bc | 10.77 g | 19.18 gh ± 0.23 |

| T9 | V2-Cd0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| T10 | V2-Cd5 | 57.93 ef | 13.73 cdef | 0.24 b | 33.36 h | 18.46 ghi ± 0.11 |

| T11 | V2-Cd25 | 44.43 g | 13.17 de | 0.30 a | 29.56 i | 53.02 j ± 0.38 |

| T12 | V2-Cd50 | 32.16 cd | 8.57 abc | 0.27 cd | 17.92 efgh | 16.36 abcd ± 0.15 |

| T13 | V3-Cd0 | — | — | — | — | — |

| T14 | V3-Cd5 | 65.81 h | 17.10 g | 0.26 b | 36.78 jk | 17.80 fg ± 0.09 |

| T15 | V3-Cd25 | 51.68 efg | 13.56 def | 0.26 b | 27.92 hi | 50.27 ijk ± 0.40 |

| T16 | V3-Cd50 | 33.85 cd | 8.11 ab | 0.24 bcd | 16.02 abc | 14.55 cdef ± 0.07 |

Data are means ± SD. BC: the bioaccumulation coefficient; TF: the translocation factor; RE: the removal efficiency. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level according to the LSD test. “—” Unavailable under the tested concentrations.

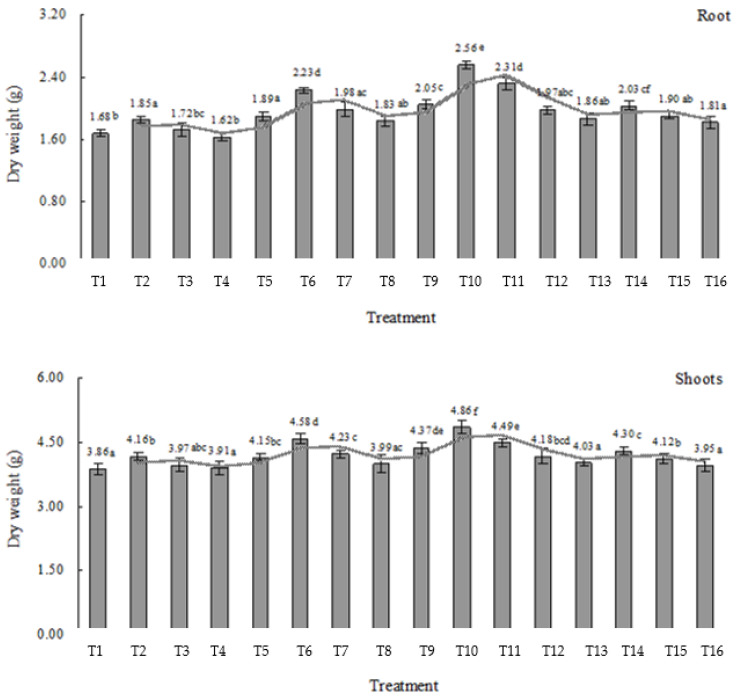

3.3. The Effect of Electric Field on Root and Shoots Dry Weight

The root and shoots biomass of the plant are considered highly sensitive indicators in their response to heavy metal and other environmental stress [37,73,74,75]. The growth responses of L. japonica in terms of root and shoots biomass dry weight under different treatments are shown in Figure 3. Under T1–T4 treatments (under Cd stress without electric field), the dry weight of root biomass increased exposed to 5 and 25 mg L−1 Cd, and decreased slightly exposed to 50 mg L−1 Cd, indicating that the plants had a good tolerance to Cd stress. Under T5, T9, and T13 treatments (under electric field without Cd stress), the dry weight of root biomass significantly increased, especially under 2 V cm−1 voltage (T9), 22.02% higher than the control. Under T6–8, T10–12, and T14–16 treatments (under electric field and Cd stress), different voltages enhanced the dry weight of root biomass exposed to different concentrations of Cd compared to the control. Furthermore, under 2 V cm−1 voltage, the dry weight of root biomass exposed to 5 (T10) and 25 mg L−1 Cd (T11) were enhanced significantly by 52.38% and 37.50% higher than the control. A similar phenomenon [43] also shows that the application of a pulsed electric field increased the root dry weight of maize under drought stress, and the enhancement could result from the improved respiration metabolism under the influence of the pulsed electric field to affect the synthesis and substance transformation. When the plants were exposed to 50 mg L−1 Cd stress, different voltages promoted the dry weight of root biomass compared with T4 treatment (V0-Cd50).

Figure 3.

The effect of electric field on root and shoots biomass dry weight (g) of L. japonica. Values represent mean ± SD. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level according to the LSD test.

By comparison, under T1–T4 treatments (under Cd stress without electric field), the dry weight of shoots biomass increased when exposed to different concentrations of Cd. The earlier study [42] showed that the stronger electric field had a limited influence on the growth of hydroponically cultivated tomatoes. However, our results divulged that under T5, T9, and T13 treatments (under electric field without Cd stress), the dry weight of shoots biomass increased significantly, especially under 2 V cm−1 voltage (T9), 13.21% higher than the control. It agrees with the study [30], which reported that Brassica rapa L. showed fast growth and biomass production with a low or moderate voltage gradient. Under T6–8, T10–12, and T14–16 treatments (under electric field and Cd stress), there is a similarly increased trend regarding the dry weight of root biomass. Furthermore, under 2 V cm−1 voltage, the dry weight of shoots biomass exposed to 5 mg L−1 Cd (T10) was enhanced significantly by 25.91% higher than the control. When the plants were exposed to 50 mg L−1 Cd stress, the dry weight of shoots biomass was enhanced by different voltages compared with T4 treatment (V0-Cd50), which showed the electric field could promote the tolerance responses of the plants to high concentrations of Cd.

Above all, applying a medium-strength electric field enhanced the root and shoots growth of L. japonica. In the present study, under 2 V cm−1 voltage, the dry weight of root and shoots biomass was significantly enhanced to 5 mg L−1 Cd compared with the control. Our present results agree with previous reports proving that the electric field stimulated plant biomass production and growth by regulating the transport and distribution of plant growth hormones [27,28,33,42,46].

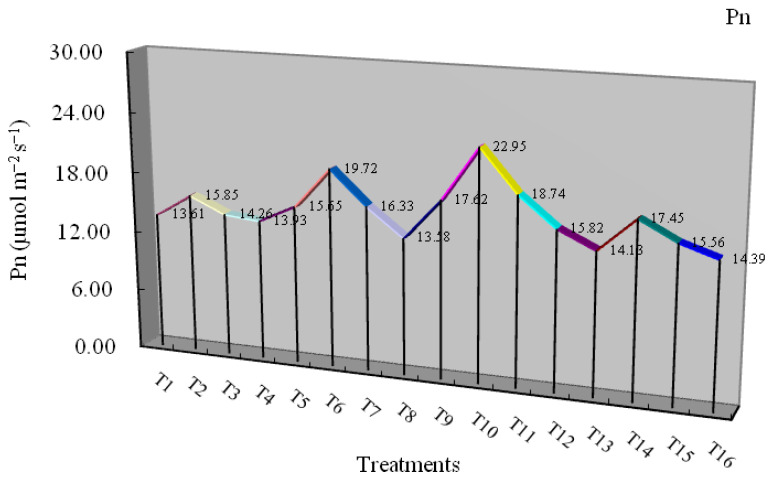

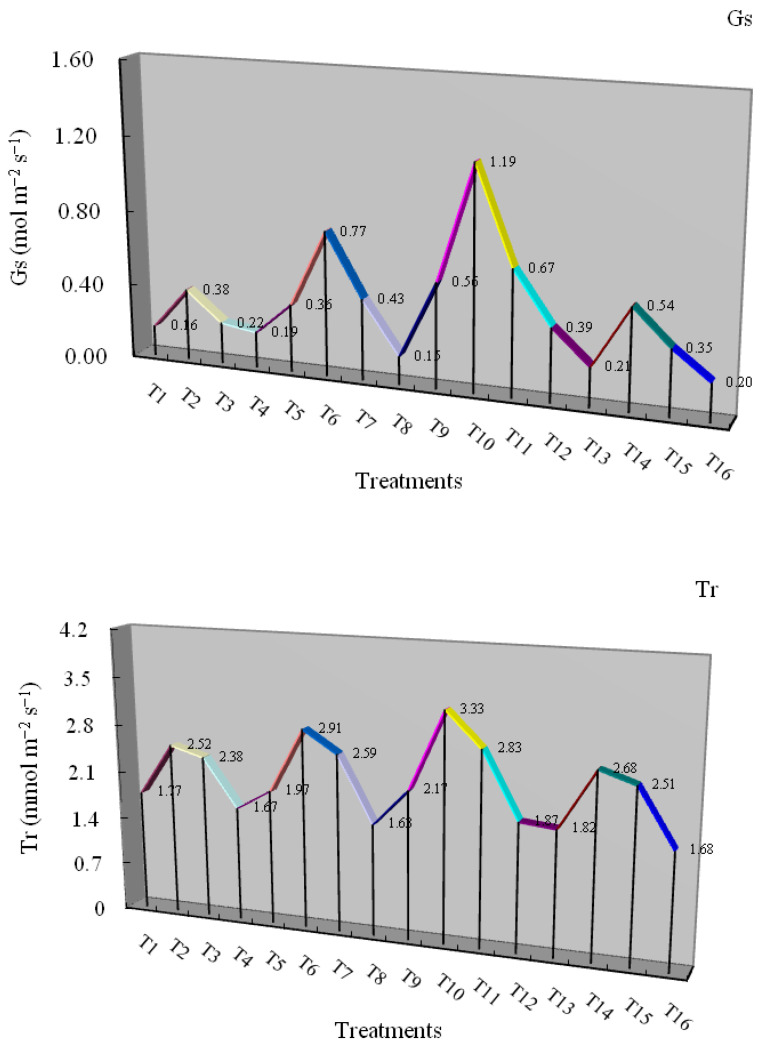

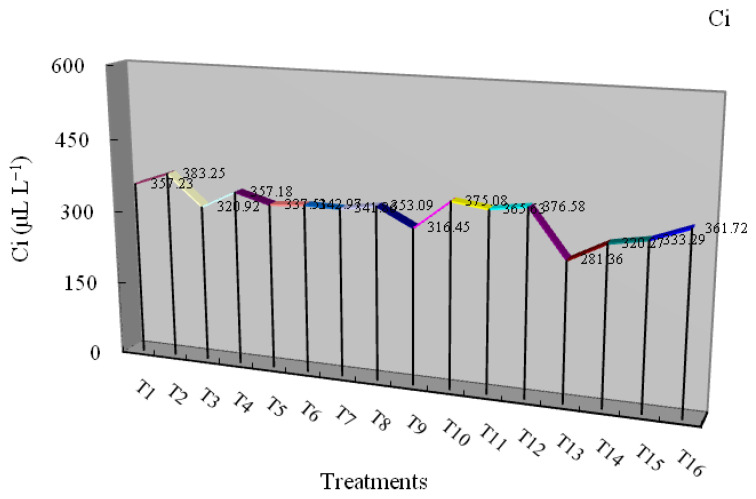

3.4. The Effect of Electric Field on Photosynthetic Parameters

Photosynthesis, one of the most important biological processes for plant growth and food production, is especially sensitive to Cd stress [76,77,78,79]. As shown in Figure 4, the net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), transpiration rate (Tr), and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) in the leaves of L. japonica under different treatments were evaluated. The significant stimulating effect of Pn exposed to low concentrations of Cd resulted in the improvement of gas exchange and transpiration in terms of the increase in Gs, Tr, and Ci, indicating the positive effect of low Cd concentrations on the contents of Rubisco [22]. A similar phenomenon was also found in maize plants [49]. The Pn, Gs, and Tr of the plants exposed to Cd stress concentrations had a similar response visualized as an inverted U-shaped curve under different voltages. Under different concentrations of Cd stress, the maximum Pn, Gs, and Tr of the plants reached 22.95 μmol m−2 s−1, 1.19 mol m−2 s−1, and 3.33 mmol m−2 s−1, and all were enhanced significantly by 2 V cm−1 voltage (T10, V2-Cd5). It is coincident with root and shoots biomass dry weight, indicating the combination of the low Cd supply (5 mg L−1) and medium voltage (2 V cm−1) was beneficial to elevate the photosynthetic capacity and growth of the plants. A similar phenomenon is also described as the hormesis effect [53]. When the plants were exposed to higher concentrations (25 mg L−1), different voltages significantly enhanced the Pn, Gs, Tr, and Ci of the plants. However, with the increase of Cd concentration in the medium, the effects were not obvious compared with T3 treatment (V0-Cd25; p < 0.05). Some studies reported that Cd negatively affected photosynthesis [80,81,82], which may be attributed to the inhibition of chlorophyll biosynthesis, pigment-protein complexes, thylakoids, or reduction in growth [80,83,84]. However, in our present study, increased or unimpacted photosynthesis showed that L. japonica did not suffer metal toxicity and produced metabolites for absorption, defense, growth, and development, which may be related to good tolerance and hyperaccumulation characteristics of the plant to stress [85]. Under T13-T16 treatments, the increased Ci with the increase of Cd concentration in the medium may result from inhibiting chloroplast metabolism via hampering light and dark reactions of photosynthesis or Calvin cycle enzymes and the photosynthetic electron transport chain [86].

Figure 4.

The effect of electric field on net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), transpiration rate (Tr), and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci). Values represent the mean.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, the electric field significantly enhanced the concentrations of Cd in roots and shoots compared with the control, especially exposed to high concentrations (25 and 50 mg L−1) Cd. The Cd concentrations in roots were enhanced significantly by 2 and 3 V cm−1 voltages, which reached above 1110.79 mg kg−1 (T11 and T12) and nearly 1700.00 mg kg−1 (T15 and T16), respectively. By comparison, the different voltages promoted Cd concentrations in shoots above 180 mg kg−1 under 25 and 50 mg L−1 Cd stress. The maximum Cd concentrations in shoots increased by 2 V cm−1 voltage (exposed to 50 mg L−1 Cd) were added to 428.67 mg kg−1, which was 2.44 times higher than T4 treatment (V0-Cd50). Root BC, shoots BC, TF, and the maximum Cd uptake of the plant were also promoted significantly by 2 V cm−1 voltage. The above results showed that 2 V cm−1 voltage might be the most suitable electric field for improving the hyperaccumulation ability of the plant.

At the same time, under 2 V cm−1 voltage, the root and shoots biomass dry weight of L. japonica exposed to 5 mg L−1 Cd increased significantly compared to the control. The maximum Pn, Gs, and Tr of the plants exposed to different concentrations of Cd were also enhanced significantly by 2 V cm−1 voltage (T10, V2-Cd5), which indicated that the synergistic benefits of low Cd supply (5 mg L−1) and medium voltage (2 V cm−1) contributed to the elevated plant growth and photosynthetic capacity. This characteristic is conducive to the practical application of the plant facing low concentration Cd-contamination in the real environment. Under T1-T4 treatments (under Cd stress without electric field), the dry weight of root biomass decreased slightly exposed to 50 mg L−1 Cd, indicating the good tolerance of the plant to Cd. However, under T6–8, T10–12, and T14–16 treatments (under electric field and Cd stress), different voltages promoted the dry weight of root biomass compared with T4 treatment (V0-Cd50), indicating the electric field could promote the tolerant ability of the plant to higher concentration Cd.

Moreover, different voltages significantly enhanced the Pn, Gs, Tr, and Ci of the plants exposed to 25 mg L−1 Cd. With the increase of Cd concentration in the medium, the effects were not obvious compared with T3 treatment (V0-Cd25). Increased or unimpacted photosynthesis showed that L. japonica did not suffer metal toxicity and produced metabolites for absorption, defense, growth, and development, along with the improved growth tolerance and hyperaccumulation ability of the plant in the electric field under external Cd stress.

According to the results above, on the one hand, it is feasible to develop a multi-system of electro-phytotechnology using a woody Cd-hyperaccumulator (L. japonica) to remediate Cd contamination. On the other hand, L. japonica, as a popular ornamental, had dual merits of phytoremediation and decoration, which will bring social and environmental benefits. The present study would provide a reference for promoting large-scale soil remediation by electric field-assisted phytoremediation, and future researchers need to consider the economic feasibility.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L., Q.L. and M.L.; data curation, Z.L. and Q.C.; formal analysis, Z.L. and M.L.; funding acquisition, M.L.; methodology, Z.L. and M.C.; software, Z.L., C.Z. and X.M.; writing-original draft, Z.L.; writing-review & editing, Z.L., Q.L. and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41807172).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the restriction policy of the co-authors’ affiliations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Feller U., Anders I., Wei S. Distribution and Redistribution of 109Cd and 65Zn in the heavy metal hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum L.: Influence of cadmium and zinc concentrations in the root medium. Plants. 2019;8:340. doi: 10.3390/plants8090340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He J.L., Zhuang X.L., Zhou J.T., Sun L.Y., Wan H.X., Li H.F., Lyu D.G. Exogenous melatonin alleviates cadmium uptake and toxicity in apple rootstocks. Tree Physiol. 2020;40:746–761. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpaa024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irshad M.A., Rehman M.Z.U., Anwar-ul-Haq M., Rizwan M., Nawaz R., Shakoor M.B., Wijaya L., Alyemeni M.N., Ahmad P., Ali S. Effect of green and chemically synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles on cadmium accumulation in wheat grains and potential dietary health risk: A field investigation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;415:125585. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durante-Yánez E.V., Martínez-Macea M.A., Enamorado-Montes G., Combatt Caballero E., Marrugo-Negrete J. Phytoremediation of soils contaminated with heavy metals from gold mining activities using Clidemia sericea D. Don. Plants. 2022;11:597. doi: 10.3390/plants11050597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zulkafflee N.S., Redzuan N.A.M., Nematbakhsh S., Selamat J., Ismail M.R., Praveena S.M., Lee S.Y., Razis A.F.A. Heavy metal contamination in Oryza sativa L. at the eastern region of Malaysia and its risk assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health. 2022;19:739. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andresen E., Kappel S., Stark H.J., Riegger U., Borovec J., Mattusch J., Heinz A., Schmelzer C.E.H., Matouskova S., Dickinson B. Cadmium toxicity investigated at the physiological and biophysical levels under environmentally relevant conditions using the aquatic model plant Ceratophyllum demersum. New Phytol. 2016;210:1244–1258. doi: 10.1111/nph.13840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borges K.L.R., Salvato F., Alcântara B.K., Nalin R.S., Piotto F.Â., Azevedo R.A. Temporal dynamic responses of roots in contrasting tomato genotypes to cadmium tolerance. Ecotoxicology. 2018;27:245–258. doi: 10.1007/s10646-017-1889-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapoor D., Singh M.P., Kaur S., Bhardwaj R., Zheng B.S., Sharma A. Modulation of the functional components of growth, photosynthesis, and anti-oxidant stress markers in cadmium exposed Brassica juncea L. Plants. 2019;8:260. doi: 10.3390/plants8080260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Z.W., Dong Y.Y., Feng L.Y., Deng Z.L., Xu Q., Tao Q., Wang C.Q., Chen Y.E., Yuan M., Yuan S. Selenium enhances cadmium accumulation capability in two mustard family species—Brassica napus and B. juncea. Plants. 2020;9:904. doi: 10.3390/plants9070904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dobrikova A.G., Apostolova E.L., Hanc A., Yotsova E., Borisova P., Sperdouli I., Adamakis I.D.S., Moustakas M. Cadmium toxicity in Salvia sclarea L.: An integrative response of element uptake, oxidative stress markers, leaf structure and photosynthesis. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2021;209:111851. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S., Prasad S. IAA alleviates Cd toxicity on growth, photosynthesis and oxidative damages in eggplant seedlings. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015;77:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s11738-015-1834-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zouari M., Ben Ahmed C., Zorrig W., Elloumi N., Rabhi M., Delmail D., Ben Rouina B., Labrousse P., Ben Abdallah F. Exogenous proline mediates alleviation of cadmium stress by promoting photosynthetic activity, water status and antioxidative enzymes activities of young date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2016;128:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rizwan M., Noureen S., Ali S., Anwar S., Rehman M.Z.U., Qayyum M.F., Hussain A. Influence of biochar amendment and foliar application of iron oxide nanoparticles on growth, photosynthesis, and cadmium accumulation in rice biomass. J. Soils Sediments. 2019;19:3749–3759. doi: 10.1007/s11368-019-02327-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y.Q., Wang H.J., Lv X., Zhang Y.T., Wang W.J. Effects of biochar and biofertilizer on cadmium-contaminated cotton growth and the antioxidative defense system. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:20112. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77142-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han Y., Zveushe O.K., Dong F.Q., Ling Q., Chen Y., Sajid S., Zhou L., de Dios V.R. Unraveling the effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on cadmium uptake and detoxification mechanisms in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) Sci. Total Environ. 2021;798:149222. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang F.W., Zhang H.B., Wang Y., He G.Q., Wang J.C., Guo D.N., Li T., Sun G.Y., Zhang H.H. The role of antioxidant mechanism in photosynthesis under heavy metals Cd or Zn exposure in tobacco leaves. J. Plant Interact. 2021;16:354–366. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2021.1961886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An T.T., Wu Y.J., Xu B.C., Zhang S.Q., Deng X.P., Zhang Y., Siddique K.H.M., Chen Y.L. Nitrogen supply improved plant growth and Cd translocation in maize at the silking and physiological maturity under moderate Cd stress. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2022;230:113137. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.113137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gieron Z.Z., Sitko K., Zieleznik-Rusinowska P., Szopinski M., Rojek-Jelonek M., Rostanski A., Rudnicka M., Malkowski E. Ecophysiology of Arabidopsis arenosa, a new hyperaccumulator of Cd and Zn. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;412:125052. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah V., Daverey A. Phytoremediation: A multidisciplinary approach to clean up heavy metal contaminated soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020;18:100774. doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2020.100774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esringu A., Turan M., Cangonul A. Remediation of Pb and Cd polluted soils with fulvic acid. Forests. 2021;12:1608. doi: 10.3390/f12111608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Placido D.F., Lee C.C. Potential of industrial hemp for phytoremediation of heavy metals. Plants. 2022;11:595. doi: 10.3390/plants11050595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying R.R., Qiu R.L., Tang Y.T., Hu P.J., Qiu H., Chen H.R., Shi T.H., Morel J.L. Cadmium tolerance of carbon assimilation enzymes and chloroplast in Zn/Cd hyperaccumulator Picris divaricata. J. Plant Physiol. 2010;167:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morina F., Kupper H. Direct inhibition of photosynthesis by Cd dominates over inhibition caused by micronutrient deficiency in the Cd/Zn hyperaccumulator Arabidopsis halleri. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020;155:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou C., Xiao X.Y., Guo Z.H., Peng C., Zeng P., Bridget A.F. Physiological responses, tolerance efficiency, and phytoextraction potential of Hylotelephium spectabile (Boreau) H. Ohba under Cd stress in hydroponic condition. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2021;23:80–88. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2020.1797628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamran M., Malik Z., Parveen A., Zong Y.T., Abbasi G.H., Rafiq M.T., Shaaban M., Mustafa A., Bashir S., Rafay M. Biochar alleviates Cd phytotoxicity by minimizing bioavailability and oxidative stress in pak choi (Brassica chinensis L.) cultivated in Cd-polluted soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2019;250:109500. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arsenov D., Zupunski M., Borisev M., Nikolic N., Pilipovic A., Orlovic S., Kebert M., Pajevic S. Citric acid as soil amendment in cadmium removal by Salix viminalis L., alterations on biometric attributes and photosynthesis. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2020;22:29–39. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2019.1633999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chirakkara R.A., Reddy K.R., Cameselle C. Electrokinetic amendment in phytoremediation of mixed contaminated soil. Electrochim. Acta. 2015;181:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2015.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harikumar P.S.P., Megha T. Treatment of heavy metals from water by electro-phytoremediation technique. J. Ecol. Eng. 2017;18:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo J., Cai L., Qi S., Wu J., Gu X.S. Influence of direct and alternating current electric fields on efficiency promotion and leaching risk alleviation of chelator assisted phytoremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;149:241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cameselle C., Gouveia S. Phytoremediation of mixed contaminated soil enhanced with electric current. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019;361:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang J.H., Dong C.D., Shen S.Y. The lead contaminated land treated by the circulation-enhanced electrokinetics and phytoremediation in field scale. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019;368:894–898. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cao Y.B., Wang X., Zhang X.Y., Misselbrook T., Bai Z.H., Ma L. An electric field immobilizes heavy metals through promoting combination with humic substances during composting. Bioresour. Technol. 2021;330:124996. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.124996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmiedchen K., Petr A.K., Driessen S., Bailey W.H. Systematic review of biological effects of exposure to static electric fields. Part II: Invertebrates and plants. Environ. Res. 2018;160:60–76. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cameselle C., Gouveia S., Urrejola S. Benefits of phytoremediation amended with DC electric field. Application to soils contaminated with heavy metals. Chemosphere. 2019;229:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan L.Z., Guo P.H., Guo S.H., Wang J.N., Huang Y.J. Influence of electrical fields enhanced phytoremediation of multi-metal contaminated soil on soil parameters and plants uptake in different soil sections. Environ. Res. 2021;198:111290. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang B., Chi G.Y., Chen X., Shi Y. Mild electrokinetic treatment of cadmium-polluted manure for improved applicability in greenhouse soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017;24:24011–24018. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-0058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Acosta-Santoyo G., Herrada R.A., De Folter S., Bustos E. Stimulation of the germination and growth of different plant species using an electric field treatment with IrO2-Ta2O5 vertical bar Ti electrodes. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 2018;93:1488–1494. doi: 10.1002/jctb.5517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anning A.K., Akoto R. Assisted phytoremediation of heavy metal contaminated soil from a mined site with Typha latifolia and Chrysopogon zizanioides. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2018;148:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Z.C., Wu B., Guo P.H., Wang S., Guo S.H. Enhanced electrokinetic remediation and simulation of cadmium-contaminated soil by superimposed electric field. Chemosphere. 2019;233:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu L., Dai H.P., Skuza L., Wei S.H. Optimal voltage and treatment time of electric field with assistant Solanum nigrum L. cadmium hyperaccumulation in soil. Chemosphere. 2020;253:126575. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bi R., Schlaak M., Siefert E., Lord R., Connolly H. Alternating current electrical field effects on lettuce (Lactuca sativa) growing in hydroponic culture with and without cadmium contamination. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2010;40:1217–1223. doi: 10.1007/s10800-010-0094-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiewiórka Z. The effects of electromagnetic and electrostatic fields on the development and yield of greenhouse tomato plants. Acta Agrobot. 2013;43:25–36. doi: 10.5586/aa.1990.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He R.R., Xi G., Liu K. Alleviating effect of extremely low frequency pulsed electric field on drought damage of maize seedling roots. J. Lumin. 2017;188:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2017.04.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.González-Casado S., Martín-Belloso O., Elez-Martínez P., Soliva-Fortuny R. Enhancing the carotenoid content of tomato fruit with pulsed electric field treatments: Effects on respiratory activity and quality attributes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018;137:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2017.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sánchez V., Francisco, López-Bellido J., Rodrigo M.A., Rodríguez L. Enhancing the removal of atrazine from soils by electrokinetic-assisted phytoremediation using ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) Chemosphere. 2019;232:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klink A., Polechonska L., Dambiec M., Bienkowski P., Klink J., Salamacha Z. The influence of an electric field on growth and trace metal content in aquatic plants. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2019;21:246–250. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2018.1524838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Y., Wang S., Cheng F.L., Guo P.H., Guo S.H. Enhancement of electrokinetic-bioremediation by ryegrass: Sustainability of electrokinetic effect and improvement of n-hexadecane degradation. Environ. Res. 2020;188:109717. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cai Z.P., Sun Y., Deng Y.H., Zheng X.J., Sun S.Y., Romantschuk M., Sinkkonen A. In situ electrokinetic (EK) remediation of the total and plant available cadmium (Cd) in paddy agricultural soil using low voltage gradients at pilot and full scales. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;785:147277. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chaneva G., Parvanova P., Tzvetkova N., Uzunova A. Photosynthetic response of maize plants against cadmium and paraquat impact. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2010;208:287–293. doi: 10.1007/s11270-009-0166-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y.E., Mao H.T., Wu N., Khan A., Din A.M.U., Ding C.B., Zhang Z.W., Yuan S., Yuan M. Different tolerance of photosynthetic apparatus to Cd stress in two rice cultivars with the same leaf Cd accumulation. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2019;41:191. doi: 10.1007/s11738-019-2981-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao Q.Y., Gu C.X., Wang Y., Li G.Z., Hao L. Ethylene insensitive mutation alleviates cadmium-induced photosynthesis impairment in Arabidopsis plants. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2022;44:16. doi: 10.1007/s11738-021-03352-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.López-Millán A.F., Sagardoy R., Solanas M., Abadía A., Abadía J. Cadmium toxicity in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) plants grown in hydroponics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2009;65:376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Z.L., Chen W., He X.Y. Influence of Cd2+ on Growth and Chlorophyll Fluorescence in a Hyperaccumulator: Lonicera japonica Thunb. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015;34:672–676. doi: 10.1007/s00344-015-9483-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.An M.J., Wang H.J., Fan H., Ippolito J.A., Meng C.M., Yu E., Li Y.B., Wang K.Y., Wei C.Z. Effects of modifiers on the growth, photosynthesis, and antioxidant enzymes of cotton under cadmium toxicity. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019;38:1196–1205. doi: 10.1007/s00344-019-09924-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen H.C., Zhang S.L., Wu K.J., Li R., He X.R., He D.N., Huang C., Wei H. The effects of exogenous organic acids on the growth, photosynthesis and cellular ultrastructure of Salix variegata Franch. Under Cd stress. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2020;187:109790. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haque A.M., Tasnim J., El-Shehawi A.M., Rahman M.A., Parvez M.S., Ahmed M.B., Kabir A.H. The Cd-induced morphological and photosynthetic disruption is related to the reduced Fe status and increased oxidative injuries in sugar beet. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2021;166:448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scholz T., Hof A., Schmitt T. Cooling effects and regulating ecosystem services provided by urban trees novel analysis approaches using urban tree cadastre data. Sustainability. 2018;10:712. doi: 10.3390/su10030712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Z., Liu Y., Hu S., Wang J., Qian J. A new type of ecological floating bed based on ornamental plants experimented in an artificially made eutrophic water body in the laboratory for nutrient removal. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021;106:2–9. doi: 10.1007/s00128-020-03086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng L., Wang Y., Cai Z., Liu J., Yu B., Zhou Q. Phytoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbon-contaminated saline-alkali soil by wild ornamental Iridaceae species. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2017;19:300–308. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2016.1225282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chandanshive V.V., Kadam S.K., Khandare R.V., Kurade M.B., Jeon B.H., Jadhav J.P., Govindwar S.P. In situ phytoremediation of dyes from textile wastewater using garden ornamental plants, effect on soil quality and plant growth. Chemosphere. 2018;210:968–976. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ciftcioglu G.C., Ebedi S., Abak K. Evaluation of the relationship between ornamental plants-based ecosystem services and human wellbeing: A case study from Lefke Region of North Cyprus. Ecol. Indic. 2019;102:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.02.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larson B.M.H., Catling P.M., Waldron G.E. The biology of Canadian weeds. 135. Lonicera japonica Thunb. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2007;87:423–438. doi: 10.4141/P06-063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thanabhorn S., Jaijoy K., Thamaree S., Ingkaninan K., Panthong A. Acute and subacute toxicity study of the ethanol extract from Lonicera japonica Thunb. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Z.L., He X.Y., Chen W., Yuan F.H., Yan K., Tao D.L. Accumulation and tolerance characteristics of cadmium in a potential hyperaccumulator—Lonicera japonica Thunb. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;169:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Z.L., He X.Y., Chen W. Effects of cadmium hyperaccumulation on the concentrations of four trace elements in Lonicera japonica Thunb. Ecotoxicology. 2011;20:698–705. doi: 10.1007/s10646-011-0609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hoagland D.R., Arnon D.I. The water-culture for growing plants without soil. Calif. Agric. Exp. Stat. Circ. 1950;347:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen L., Zhu Y., Luo H., Yang J. Characteristic of adsorption, desorption, and co-transport of vanadium on humic acid colloid. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020;190:110087. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.110087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bi R., Schlaak M., Siefert E., Lord R., Connolly H. Influence of electrical fields (AC and DC) on phytoremediation of metal polluted soils with rapeseed (Brassica napus) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) Chemosphere. 2011;83:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taamalli M., Ghabriche R., Amari T., Mnasri M., Zolla L., Lutts S., Abdely C., Ghnaya T. Comparative study of Cd tolerance and accumulation potential between Cakile maritima L. (halophyte) and Brassica juncea L. Ecol. Eng. 2014;71:623–627. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rezapour S., Atashpaz B., Moghaddam S.S., Kalavrouziotis I.K., Damalas C.A. Cadmium accumulation, translocation factor, and health risk potential in a wastewater-irrigated soil-wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) system. Chemosphere. 2019;231:579–587. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zeng P., Guo G., Xiao X., Peng C., Feng W. Phytoextraction potential of Pteris vittata L. co-planted with woody species for As, Cd, Pb and Zn in contaminated soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;650:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang Y.F., Chen J.H., Sun Y.M., Wang H.X., Zhan J.Y., Huang Y.N., Zou J.W., Wang L., Su N.N., Cui J. Mechanisms of calcium sulfate in alleviating cadmium toxicity and accumulation in pak choi seedlings. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;805:150115. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Prabakaran K., Li J., Anandkumar A., Leng Z., Zou C.B., Du D. Managing environmental contamination through phytoremediation by invasive plants: A review. Ecol. Eng. 2019;138:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2019.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Szopinski M., Sitko K., Rusinowski S., Zieleznik-Rusinowska P., Corso M., Rostanski A., Rojek-Jelonek M., Verbruggen N., Malkowski E. Different strategies of Cd tolerance and accumulation in Arabidopsis halleri and Arabidopsis arenosa. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43:3002–3019. doi: 10.1111/pce.13883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen L., Hu W.F., Long C., Wang D. Exogenous plant growth regulator alleviate the adverse effects of U and Cd stress in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) and improve the efficacy of U and Cd remediation. Chemosphere. 2021;262:127809. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li S.L., Yang W.H., Yang T.T., Chen Y., Ni W.Z. Effects of cadmium stress on leaf chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis of Elsholtzia argyi—A cadmium accumulating plant. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2015;17:85–92. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2013.828020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ooms M.D., Dinh C.T., Sargent E.H., Sinton D. Photon management for augmented photosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12699. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu L., Shang Y.K., Li L., Chen Y.H., Qin Z.Z., Zhou L.J., Yuan M., Ding C.B., Liu J., Huang Y. Cadmium stress in Dongying wild soybean seedlings: Growth, Cd accumulation, and photosynthesis. Photosynthetica. 2018;56:1346–1352. doi: 10.1007/s11099-018-0844-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Han T.W., Tseng C.C., Cai M.G., Chen K., Cheng S.Y., Wang J. Effects of cadmium on bioaccumulation, bioabsorption, and photosynthesis in Sarcodia suiae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pubic Health. 2020;17:1294. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khan N.A., Samiullah S.S., Nazar R. Activities of antioxidative enzymes, sulphur assimilation, photosynthetic activity and growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivars differing in yield potential under cadmium stress. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2007;193:435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.2007.00272.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mobin M., Khan N.A. Photosynthetic activity, pigment composition and antioxidative response of two mustard (Brassica juncea) cultivars differing in photosynthetic capacity subjected to cadmium stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2007;164:601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dai H.P., Wei Y., Zhang Y.Z., Gao P.X., Chen J.W., Jia G.L., Yang T.X., Feng S.J., Wang C.F., Wang Y., et al. Influence of photosynthesis and chlorophyll synthesis on Cd accumulation in Populusxcanescens. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012;10:1020–1023. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pietrini F., Iannelli M.A., Pasqualini S., Massacci A. Interaction of cadmium with glutathione and photosynthesis in developing leaves and chloroplasts of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex strudel. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:829–837. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ekmekci Y., Tanydoc D., Ayhan B. Effect of cadmium on antioxidant enzyme and photosynthetic activities in leaves of two maize cultivars. J. Plant Physiol. 2008;165:600–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pietrini F., Zacchini M., Iori V., Pietrosanti L., Bianconi D., Massacci A. Screening of poplar clones for cadmium phytoremediation using photosynthesis, biomass and cadmium content analyses. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2009;12:105–120. doi: 10.1080/15226510902767163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nwugo C.C., Huerta A.J. Silicon-induced cadmium resistance in rice (Oryza sativa) J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2008;171:841–848. doi: 10.1002/jpln.200800082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the restriction policy of the co-authors’ affiliations.