Abstract

The dynamic of soil-borne disease is closely related to the rhizosphere microbial communities. Maize–soybean relay strip intercropping has been shown to significantly control the type of soybean root rot that tends to occur in monoculture. However, it is still unknown whether the rhizosphere microbial community participates in the regulation of intercropped soybean root rot. In this study, rhizosphere Fusarium and Trichoderma communities were compared in either healthy or root-rotted rhizosphere soil from monocultured and intercropped soybean, and our results showed the abundance of rhizosphere Fusarium in intercropping was remarkably different from monoculture. Of four species identified, F. oxysporum was the most aggressive and more frequently isolated in diseased soil of monoculture. In contrast, Trichoderma was largely accumulated in healthy rhizosphere soil of intercropping rather than monoculture. T. harzianum dramatically increased in the rhizosphere of intercropping, while T. virens and T. afroharzianum also exhibited distinct isolation frequency. For the antagonism test in vitro, Trichoderma strains had antagonistic effects on F. oxysporum with the percentage of mycelial inhibition ranging from 50.59–92.94%, and they displayed good mycoparasitic abilities against F. oxysporum through coiling around and entering into the hyphae, expanding along the cell–cell lumen and even dissolving cell walls of the target fungus. These results indicate maize–soybean relay strip intercropping significantly increases the density and composition proportion of beneficial Trichoderma to antagonize the pathogenic Fusarium species in rhizosphere, thus potentially contributing to the suppression of soybean root rot under the intercropping.

Keywords: maize–soybean relay strip intercropping, Fusarium root rot, Trichoderm spp., Fusarium spp., antagonism

1. Introduction

Soybean root rot is one of the detrimental soil-borne fungal diseases in soybean production worldwide. A variety of pathogens, including Fusarium, cause soybean root rot, leading to 10–60% loss of soybean yield [1,2,3]. This disease is remarkably affected by cropping pattern [4,5,6,7]. In Northeast China, Fusarium root rot is very popular because of long-term continuous soybean monoculture and has been recognized as one important limited factor of soybean production [6]. With the increasing of soybean planting area in Southwest China, this disease has potentially threatened local soybean production [7,8]. Currently, the control of soybean root rot is mainly dependent on agricultural practices such as crop rotation or intercropping, soil tilling, varieties with effective and durable resistance as well as seed treatment [5,9,10]. Although resistance breeding of soybean has largely developed with modern molecular techniques, cost-effective and durable resistant varieties are still lacking for application [4,5,11,12]. Chemicals are very helpful to prevent pathogen infection, but often fail to cure a plant once infection occurs, and otherwise sometimes affect beneficial soil microbes due to excessive accumulation in the soil environment [13,14]. Biological control has always attracted considerable attention to the sustainable management of soybean root rot because of its advantages on the balance of crop production and agricultural environment protection [15,16,17].

Trichoderma is one genus of fungi in the family Hypocreaceae, which is commonly existing in soil, root and foliar ecosystem [18]. T. lignorum was firstly reported in 1983 to have an antagonistic effect on Rhizoctonia solani [19]. Many Trichoderma species, such as T. harzianum, T. virens, T. asperellum, T. hamatum, T. longibrachiatum and T. koningii, have successively been identified as antagonistic fungi against plant pathogens so far [20,21], especially soil-borne pathogenic fungi [22,23,24,25]. For example, T. harzianum and T. asperellum are commercially effective biological control agents against F. oxysporum causing watermelon wilt [26], and T. asperellum isolates significantly suppress Fusarium wilt of tomato [27]. Some Trichoderma strains can confer biocontrol either directly by interacting with pathogens via mycoparasitism, or by competition for nutrients or root niches, while other strains establish robust and durable colonization of root surfaces and penetrate into the epidermal cells to indirectly induce the host resistance and enhance root growth [20,28]. Accordingly, Trichoderma has become one of the most extensively studied beneficial fungi for agricultural crop improvement [29], and a few species have already been explored as fungal biocontrol agents (BCA) or bio-pesticides for the biocontrol of the soil-borne fungal diseases [30].

Research increasingly indicates that the cropping pattern can affect the soil microbial community, change the composition of beneficial and pathogenic microbes and regulate the occurrence of soil-borne disease [31]. In the Radix pseudostellariae rhizosphere, the consecutive monoculture increases the abundance of the pathogenic F. oxysporum but decreases Trichoderma spp. [32]. Recently, a maize–soybean relay strip intercropping has been widely practiced in Southwest China, and this cropping pattern is characterized by two-row maize plant strips intercropped with two to four rows of soybean which have positive effects on increasing the land equivalent ratio [33], improving the soil nutrients and microbe structure [34,35,36], reducing weeds and diseases in the field [7,37] and increasing crop yield [38,39] as compared to soybean monoculture. This intercropping can also reduce the disease severity of Fusarium root rot and change the population diversity of the pathogenic Fusarium species in diseased soybean roots [7]. However, the underlying mechanism of regulating soybean root rot by this intercropping is largely unclear.

In the current study, we will focus on rhizosphere microbial communities and their participation in the regulation of soybean root rot in maize–soybean relay stripping intercropping as compared to soybean monoculture. For this, the aims were: 1—the density of Fusarium and Trichoderma communities was identified and compared from diseased soybean rhizosphere soil and healthy soybean rhizosphere soil of intercropping and monoculture; 2—the antagonistic effects of Trichoderma species on the pathogenic F. oxysporum of soybean root rot were examined in vitro. This study will be meaningful for uncovering the rhizosphere microbial regulation of maize–soybean relay strip intercropping on Fusarium root rot and exploring the beneficial Trichoderma strains for the biocontrol of soil-borne diseases.

2. Results

2.1. Population Density of Rhizosphere Fusarium and Trichoderma in Response to Intercropping and Monoculture

To uncover the influence of cropping patterns on the density of rhizosphere Fusarium and Trichoderma communities associated with soybean root rot, the richness of these two fungi was compared between diseased rhizosphere soil and healthy rhizosphere soil, as well as between intercropping and monoculture. As shown in Table 1, Fusarium was the richest with 1046.51 cfu·g−1 in diseased rhizosphere soil of intercropping (IDR), whereas it had no significant difference in two soil types of soybean monoculture. In contrast, Trichoderma richness in two soil types of intercropping (IDR and IHR) was much higher than that of monoculture (MDR and MHR). Meanwhile, Trichderma was also much richer in healthy rhizosphere soil (IHR) than diseased rhizosphere soil (IDR) of maize–soybean relay strip intercropping, but it had almost no difference between two soil samples of soybean monoculture. Thus, it is clear that Fusarium richness was significantly declined in healthy rhizosphere soil in two cropping patterns followed by the increasing of Trichoderma, and rhizosphere Trichoderma richness is more dramatically affected by cropping pattern while Fusarium richness is also remarkably distinct with respect to the occurrence of root rot under the intercropping.

Table 1.

Population richness of Fusarium and Trichoderma communities in different soil samples from intercropping and soybean monoculture.

| Cropping Patterns | Soil Samples | Sample Code |

Trichoderma Richness (cfu·g−1) |

Fusarium Richness (cfu·g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercropping | Diseased rhizosphere soil | IDR | 2560.98 ± 2414.51 ab | 1046.51 ± 164.44 a |

| Healthy rhizosphere soil | IHR | 4404.76 ± 168.36 a | 329.67 ± 186.49 b | |

| Monoculture | Diseased rhizosphere soil | MDR | 523.26 ± 82.22 b | 391.62 ± 12.88 b |

| Healthy rhizosphere soil | MHR | 523.26 ± 82.22 b | 458.09 ± 151.62 b |

Notes: Different lowercase indicate the significant difference at the level of p = 0.05 using SPSS ANOVN.

2.2. Species Identification of Rhizosphere Trichoderma and Fusarium in Response to Intercropping and Monoculture

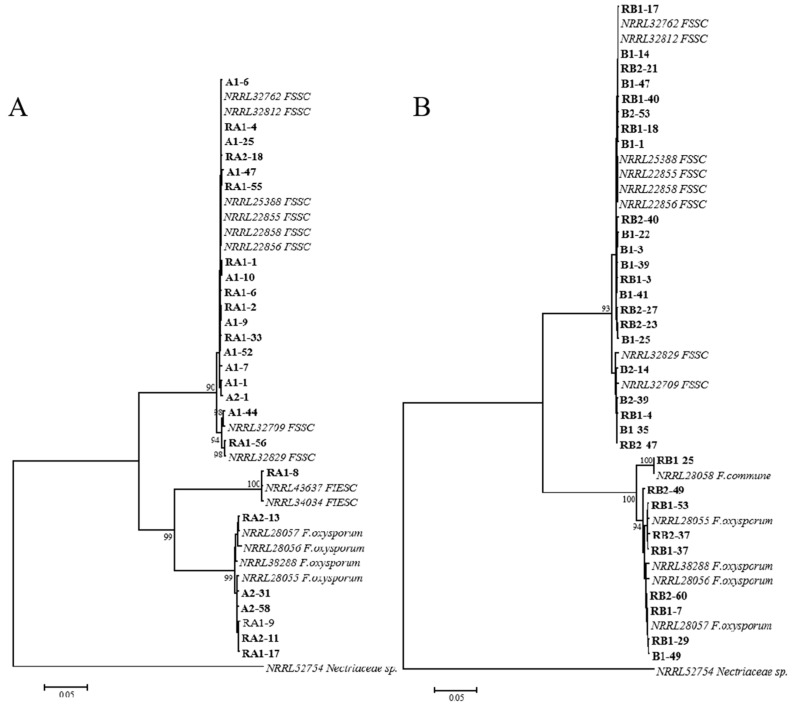

In this study, a total of 165 Fusarium isolates were obtained from four soil types of intercropping and monoculture. Sequences of EF-1α and RPB2 genes were amplified using primer pairs (Supplementary Materials Table S1) and analyzed by blasting on the Fusarium MLST database, which showed that these isolates shared more than 98% sequence identities with those reference isolates of F.solani species complex (FSSC), F.oxysporum, F.incarnatum-equiseti species complex (FIESC) and F.commune (Supplementary Material Table S2), respectively. A phylogenetic tree based on EF-1α and RPB2 was constructed with the representative isolates, reference isolates from NCBI, and the outgroup isolate Nectriaceae sp. (NRRL52754) (Supplementary Material Table S2 and Table S3), and the representative isolates from intercropping were absolutely classified into three clades including FSSC, FIESC and F. oxysporum in this tree (Figure 1A), while those isolates from monoculture were claded into FSSC, F. oxysporum and F. commune, respectively (Figure 1B), thus displaying a distinct species composition of Fusarium between intercropping and monoculture.

Figure 1.

The phylogenetic tree based of EF-1α and RPB2 genes was constructed using a neighbor-joining method for rhizosphere Fusarium isolates from intercropping and monoculture, respectively. (A) the phylogenetic tree constructed using Fusarium isolates from maize soybean relay strip intercropping. (B) the phylogenetic tree constructed using Fusarium isolates from soybean monoculture. Bootstrap support values were more than 90 % in both trees and obtained from 1000 replications. The Nectriaceae sp. (accession no. NRRL52754) was used as the outgroup isolate.

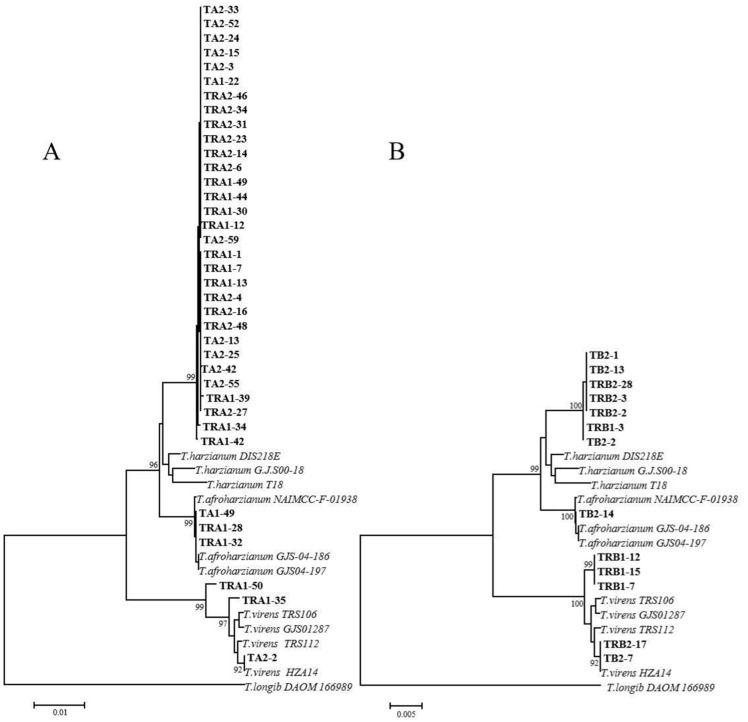

Trichoderma isolates were recovered from rhizosphere soil of diseased and healthy soybean plants in two cropping patterns. Blastn analysis of partial ITS, EF-1α or RPB2 genes on the NCBI database showed that these isolates had more than 95% sequence identities with T. harzianum, T. virens and T. afroharzianum (Supplementary Material Table S3 and Table S4). For phylogenetic analysis (Figure 2), all representative isolates from either intercropping or monoculture were clearly claded intro T. harzianum, T. virens and T. afroharzianum, respectively, in the ITS/RPB2-based MP trees, whereas T. harzianum and T. afroharzianum were not totally discriminated in the ITS/EF-1α-based phylogenetic trees in both cropping patterns (Supplementary Material Figure S1). Thus, Trichoderma isolates from rhizosphere soil were identified as T. virens, T. afroharzianum and T. harzianum, and there was no difference in species diversity between intercropping and monoculture.

Figure 2.

A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree based on ITS and RPB2 genes was constructed for intercropping and monoculture, respectively. (A) the phylogenetic tree constructed using Fusarium isolates from maize soybean relay strip intercropping. (B) the phylogenetic tree constructed using Fusarium isolates from soybean monoculture. Bootstrap support values were more than 92% in both trees and obtained from 1000 replications. The Trichoderma longib (DAOM 166989) was used as the outgroup isolate.

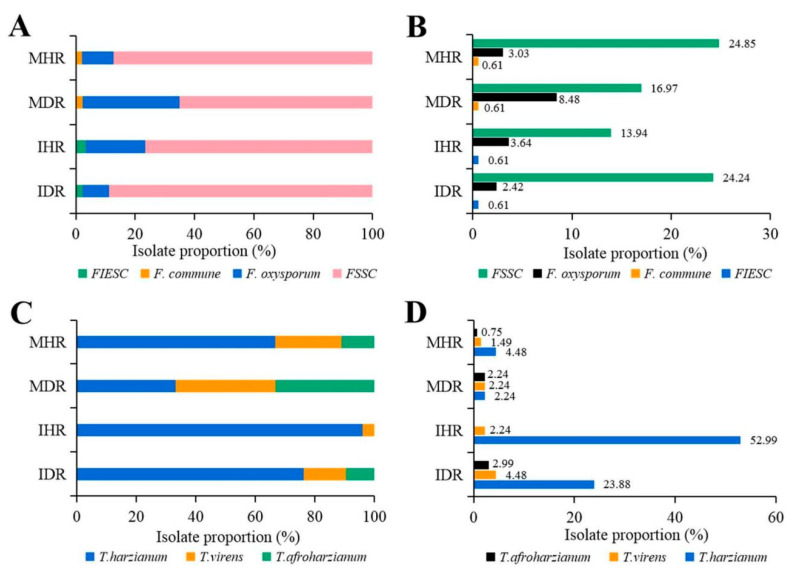

2.3. Composition and Isolation Proportion of Fusarium spp. and Trichoderma spp. Affected by Intercropping and Monoculture

The composition and isolation proportion of rhizosphere Fusarium and Trichoderma spp. was further compared between monoculture and intercropping as well as between diseased and healthy soils. As shown in Figure 3A,B, FSSC had the highest isolation proportion in all soil types that reached up to 88.89% (40/45) of Fusarium composition and 24.24% (40/165) of all isolated Fusarium in IDR as compared to 65% (28/43) and 16.97% (28/165) in MDR (Figure 3A,B), respectively. F. oxysporum accounted for the second largest proportion in different soil samples and had the highest proportion of 32.56% (14/43) in MDR than that of 8.89% (4/45) in IDR (Figure 1A). The FIESC and F. commune were specifically isolated species in intercropping and monoculture, respectively, with relatively less proportion in corresponding soil samples (Figure 1A,B).

Figure 3.

(A) Composition proportion of each Fusarium species in each soil sample. (B) Isolation proportion of each Fusarium species in total Fusarium isolates from all soil samples. (C) Composition proportion of each Trichoderma species in each soil sample. (D) Isolation proportion of each Trichoderma species in total Trichoderma isolates from all soil samples. The difference in composition percentage and isolation percentage was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test.

In this study, a total of three Trichoderma species were obtained from rhizosphere soils of two cropping patterns, but the species composition and isolation proportion varied over the occurrence of root rot as well as cropping pattern (Figure 3C,D). Both T. harzianum and T. virens were isolated from all soil types, but T. harzianum was the most predominant species of Trichoderma (Figure 3D). The composition proportion of T. harzianum was 95.9 % (71/74) and 76.2% (32/42) in IHR and IDR, whereas it was as low as 66.7% (6/9) and 33.3% (3/9) in MHR and MDR, respectively. As the secondary dominant species, T. virens of Trichoderma composition was clearly declined in two soil types of intercropping when compared with monoculture, whereas an increase in T. afroharzianum appeared in MHR and MDR of monoculture and in IDR of intercropping. These results indicate that intercropping changes Trichoderma composition and remarkably increases T. harzianum isolation proportion in comparison to monoculture.

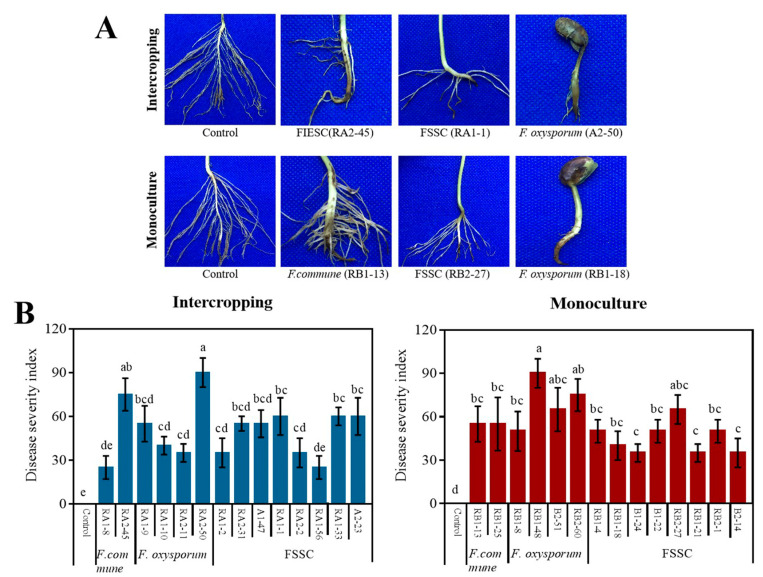

2.4. The Pathogenicity of Rhizosphere Fusarium spp. on Soybean

Pathogenicity test of rhizosphere Fusarium species on soybean seedlings showed that all four Fusarium species were able to infect soybean roots and cause stunted, brown, rotted taproots and hair roots, but displayed significantly different aggressiveness (Figure 4A). F. oxysporum was the most aggressive species among all Fusarium species with a disease severity index (DSI) ranging from 35 to 90 (Figure 4B). The DSI of F. oxysporum isolates from monoculture were much higher than those from intercropping, and the highest DSI went up to 90 (Figure 4B) followed by serious growth inhibition and rotted taproot (Figure 4A). FSSC as the most isolated fungi had moderate aggressiveness with DSI around 50, and there was no significant difference among those isolates from two cropping patterns. In addition, FIESC and F. commune separately for intercropping and monoculture were also moderately pathogenic to soybean, but different for their aggressiveness.

Figure 4.

(A) Symptoms of soybean seedlings after inoculation with representative isolates of rhizosphere Fusarium species from intercropping and monoculture; FIESC (RA2-45), FSSC (RA-1), F. oxysporum (A2-50), F. commune (RB1-13), FSSC (RB2-27) and F. oxysporum (RB1-18) were the representative isolates of the corresponding Fusarium species from intercropping and monoculture. Control means soybean seedings without Fusarium inoculation. (B) Disease severity index of soybean root rot caused by representative Fusarium isolates in both cropping patterns. Difference significance was calculated from three independent replicates using SPSS 20 software at the level of p = 0.05 and marked by lowercase.

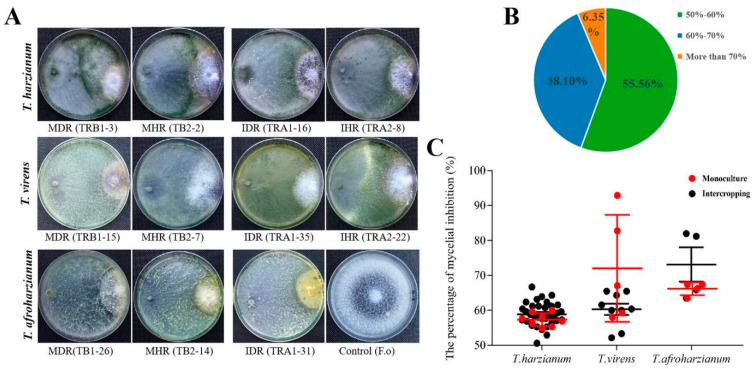

2.5. Inhibition Effects of Trichoderma spp. on the Pathogenic F. oxysporum of Soybean Root Rot

As compared to the F. oxysporum control, the representative isolates of three Trichoderma species grew towards F. oxysporum and significantly inhibited mycelial growth of F. oxysporum through spatial competition on PDA confrontation culture plates (Figure 5A), and the inhibition response had almost no difference among the same Trichoderma species from intercropping and monoculture. Furthermore, the percentage of mycelial inhibition (PMI) was distinct among three Trichoderma species, but 38.10% of isolates had the PMI values in the range of 60–70% (Figure 5B). T. harzianum isolates showed almost the same range of PMI between intercropping and monoculture, whereas T. afroharzianum and T. virens had slightly different central PMI values for tested isolates from two cropping patterns. Under two cropping patterns, there was almost no difference in the mean PMI of T. harzianum, which were 58.91% in intercropping and 57.35% in monoculture, respectively. The mean PMI for T. virens was concentrated at 72.0% in intercropping, but it was as high as 60.30% in monoculture (Figure 5C). In contrast, the mean PMI for T. afroharzianum was slightly higher, up to 73.14% in intercropping as compared to 66.18% in monoculture (Figure 5C). This indicates that T. virens and T. afroharzianum might be also related to F. oyxsporum inhibition during rhizosphere fungal interaction with respect to cropping pattern.

Figure 5.

(A) Confrontation culture of Trichoderma isolates against F. oxysporum on PDA plates. IDR and IHR are the abbreviations of diseased rhizosphere soil and healthy rhizosphere soil in maize–soybean relay strip intercropping, respectively; MDR and MHR stand for rhizosphere diseased soil and rhizosphere healthy soil in soybean monoculture, respectively. The isolate codes are marked in the brackets following the abbreviation of soil samples. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentages of Trichoderma isolates with different inhibition of mycelial percentage (IP) of 50–60%, 60–70% and more than 70%, respectively. (C) The inhibition percentage of Trichoderma isolates for three species against F. oxysporum in both maize–soybean relay strip intercropping and monoculture which are marked as black dots and red dots in the graph, respectively. The error bar represents the standard error of the mean value of three independent replicates, and the graph is drawn by GraPhpad Prism 7.00 software (https://www.graphpad.com/ accessed on 14 May 2021).

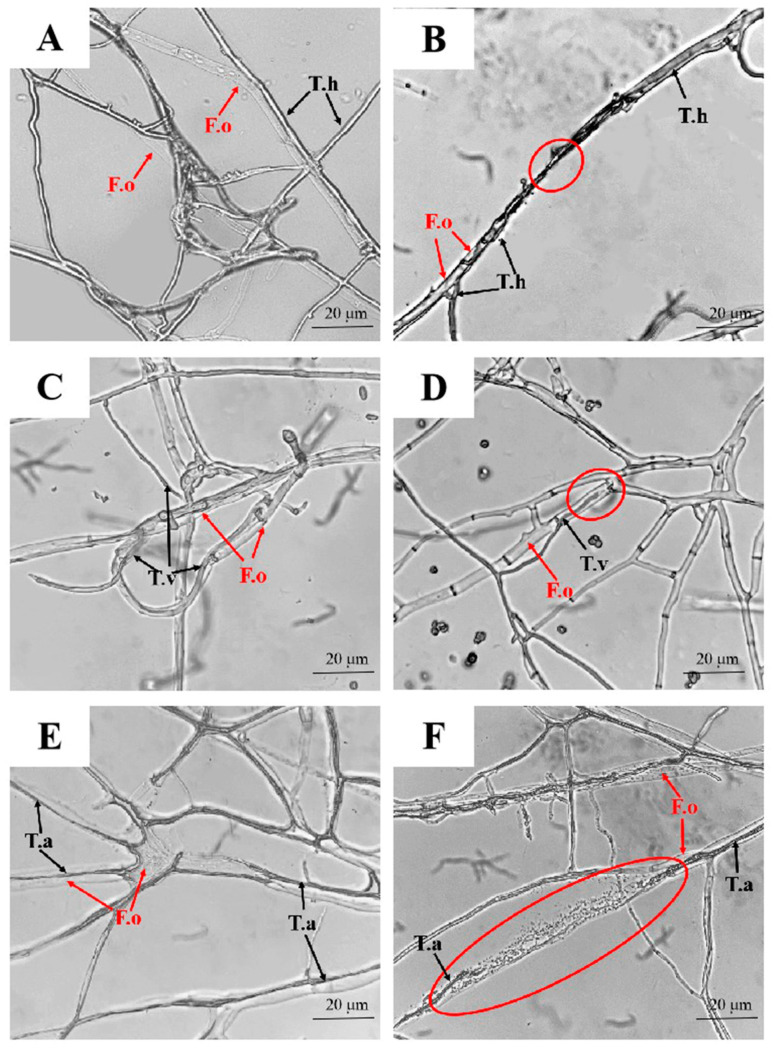

To observe the hyphae interaction, T. harzianum grew towards (Figure 6A), attached to the hyphae of F. oxysporum, and coiled around them (Figure 6B). The strains TRB1-15 and TRB1-7 of T. virens coiled around the hyphae, formed brown halos at the contact sites (Figure 6C), and some of them directly entered into the lumen of the target fungus (Figure 6D). As shown in Figure 6E, the hyphae of T.afroharzianum entered into the cell lumen of F. oxysporum and expanded along the host hyphae (Figure 6E), and resulted in dissolution of cell walls (Figure 6F). In general, rhizosphere Trichoderma strains display good mycoparasitic abilities against the pathogenic F. oxysporum of soybean root rot.

Figure 6.

The hyphae interaction of T. harzianum (A,B), T. virens (C,D) and T. afroharzianum (E,F) with F. oxysporum was observed under a compound microscope after confrontation culture on PDA plates for 3 days. The area marked by red circle means the interaction points of Trichoderma spp. and F. oxysporum. The hyphae of T. harzianum, T. afroharzianum, T. virens and F. oxysporum are abbreviated as T.h, T.a, T.v and F.o, respectively, and marked by red or black arrows. The scale bar represents 20 µm.

3. Discussion

Rhizosphere soil microbes play an important role in regulating soil-borne diseases that are closely related with cropping patterns [40,41,42]. Our previous study proved that maize–soybean relay strip intercropping suppressed the occurrence of soybean root rot and changed the diversity of the pathogenic Fusarium species [7]. In this study, we further focused on this intercropping effect on rhizosphere Fusarium communities and potential biocontrol Trichoderma communities in association with soybean root rot. We found that continuous maize–soybean relay strip intercropping caused a significant accumulation of rhizosphere Trichoderma, but reduced the abundance of the pathogenic Fusarium communities, in particular, in healthy soils. In contrast, consecutive soybean monoculture displayed almost no influence on the density of Trichoderma and Fusarium, no matter whether in diseased or healthy rhizosphere soils. These findings demonstrate that maize–soybean relay strip intercropping is beneficial to induce the accumulation of the rhizosphere Trichoderma community.

Fusarium species are the dominant pathogens of soybean root rot in Sichuan Province, Southwest China [7], and these Fusarium species often can survive saprophytically and accumulate largely on crop debris, even on or inside cultivated soil, thus serving as primary inocula for soybean infection in rhizosphere microenvironments in the following epidemic year [43]. In our study, four Fusarium species including F. oyxsporum, FSSC, FIESC and F. commune were identified from all rhizosphere soil samples and all resulted in pathogenicity in soybean. Among them, FSSC and F. oxysporum were most frequently isolated in both cropping patterns, which is similar to those by Liu et al. [44] who isolated Fusarium spp. from soybean rhizosphere soil of different rotation systems in the black soil area of Northeast China. However, F. oxysporum, rather than FSSC, had the highest isolation proportion from soybean rhizosphere soil in the black soil area [44], indicating an association between the difference in dominant rhizosphere Fusarium species and soybean ecological planting areas. Our previous study reported FSSC and F. oxysporum were the predominant species isolated from diseased soybean root in both maize–soybean relay strip intercropping and soybean monoculture [7,8]. In contrast, in this study, the diversity of Fusarium spp. was remarkably lower from diseased and healthy rhizosphere soils of two cropping patterns. These results indicate that some Fusarium species causing soybean root rot, such as F. gramniearum, F. asiaticum, F. proliferatum, might come from aboveground inoculums instead of rhizosphere soil-borne pathogens. Moreover, FIESC and F. commune were specific to intercropping and monoculture with relatively low isolation proportion, respectively, which is basically consistent with our previous findings that specifically isolated F. commune and a low isolation proportion of FIESC from the diseased soybean roots in monoculture rather than maize–soybean relay strip intercropping [7]. In addition, compared with intercropping, soybean monoculture did not change the density of rhizosphere Fusarium, but dramatically raised the proportion of composition and isolation of the most aggressive F. oxysporum. Therefore, unlike intercropping, more severe root rot in soybean monoculture might be related to a relatively higher proportion of the aggressive F. oxysporum but not a higher density of Fusarium communities. This can be supported by another study that continuous soybean cropping increased the population of Fusarium and tended to increase the susceptibility to root rot [45].

Beneficial soil microbes have some advantages on suppressing soil-borne pathogenic fungi, promoting plant growth or decomposing plant residues [46]. Trichoderma has widely been recognized as biological alternatives of soil-borne diseases in crop production [24,25], but Trichoderma communities are often affected by cropping patterns [47]. Previous studies found that compared with soybean–maize rotation, continuous soybean monoculture decreased the populations of Trichoderma [47]. In contrast, the abundance of soil Trichoderma increased significantly under the intercropping of sorghum and soybean [48]. Wei et al. (2014) previously identified three Trichoderma species, mainly T. harzianum and T. virens, and a small amount of T. viride, from soybean rhizosphere soil for different rotation years in Heilongjiang Province, China. Similarly, we found that T. harzianum had the highest isolation proportion from soybean rhizosphere soil of two cropping patterns, followed by T. virens and T. afroharzianum. We also observed that these Trichoderma species displayed a good mycoparasitic abilities in the antagonist against the pathogenic F. oxysporum of soybean root rot, and they interacted with F. oxysporum mainly through coiling around the hyphae, entering into the lumen of the target fungus, expanding into the cell–cell area and finally dissolving the cell wall of the host fungus. Thus, these antagonistic interactions of Trichoderma and Fusarium might explain that with the increase in Trichoderma, the Fusarium community was significantly decreased in healthy rhizosphere soil than that in diseased rhizosphere soil under intercropping pattern. In other studies, T. virens has been recognized as an aggressive mycoparasite that is capable of competing with pathogens at the site of infection [49] and also induces JA- and SA-mediated tomato resistance against Fusarium wilt [50]. From this point of view, Trichoderma communities are an important group in response to maize–soybean relay strip intercropping as compared to soybean monoculture. This is also supported by Chen et al. [32] who expanded that the monoculture of R. pseudostellariae altered Trichoderma communities in the plant rhizosphere leading to relatively low level of antagonistic microorganisms, and T. harzianum ZC51 could inhibit the pathogenic F. oxysporum and induce the expression of defense genes. However, several studies have shown that Trichoderma strains with a good plate-confrontation effect on pathogens might be not necessarily good, or even no effect, which is predicted to associate with the colonization ability of Trichoderma on plants [51]. Therefore, the antagonistic mechanism of these Trichoderma strains against F. oxysporum causing soybean root rot should be further verified in the actual field production.

4. Materials and Methods

Maize–soybean relay strip intercropping and soybean monoculture were continuously planted since 2012 at Yucheng District, Yaan City, China (29°59″3.17′ N, 102°59″2.57′ E) as described by Chang et al. [7]. This field experiment was designed using the randomized complete block for three replicated experimental plots. Maize cultivar “Denghai605” and soybean cultivar “Nandou12” were selected in the intercropping or monoculture, and all plots were not tilled before sowing to remain soil microbial community.

4.1. Collection of Soil Samples

At the R2 growth stage of soybean in the summer of 2018, soil samples were collected from diseased soybean plants displaying root rot and healthy soybean plants in each experimental plot of intercropping (marked as IDR and IHR) and monoculture (marked as MDR and MHR), respectively. The rhizosphere soil was carefully scraped from soybean root hair using a hairbrush after shaking off the loosely attached soil from the soil block. The soil of 9 plants accounting for about 5% of total plants in each plot were mixed as one sample and kept in an icebox with a sterile polyethylene bag, and then were used for the isolation and identification of Fusarium and Trichoderma species.

4.2. Isolation and Purification of Fusarium and Trichoderma

After drying and filtering using a 60 μm sieve, Fusarium were isolated from soil samples using sterilized Fusarium-selective medium (PPA, 5 g∙L−1 Tryptone, 1.0 g∙L−1 KH2PO4, 0.5 g∙L−1 MgSO4, 1.0g∙L−1 quintozene, 20.0 g∙L−1 agar) referred to previous methods [44]. Rhizosphere soil with different weights (0.020 g, 0.025 g, 0.030 g, 0.035 g, 0.040 g, 0.045 g and 0.050 g) were mixed with PPA medium poured on 90 mm plates and then incubated at 25 °C for 5–7 days. The colony number on PPA plates with the proper soil weight was calculated. Pure isolates of Fusarium were obtained through single-spore isolation method and transferred into Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, 200 g∙L−1 potato, 10 g∙L−1 glucosum anhydricum and 15 g∙L−1 agar) for further analysis.

Isolation of soil Trichoderma was conducted using dilution plate method using Trichoderma-selective medium (TSM, glucose 3 g∙L−1, monobasic potassium phosphate 0.9 g∙L−1, magnesium sulfate 0.2 g∙L−1, 1/3000 rose-bengal 100 mL∙L−1, potassium chloride 0.15 g∙L−1, ammonium nitrate1 g∙L−1, agar 20 g∙L−1) as described by Elad et al. [52] with minor revisions. Total of 10 g of soil samples was suspended in 90 mL sterilized water containing 0.5% Tween−80 and shaken at 25 °C, 150 r·min−1 for 40 min. About 1 mL of soil suspension was then diluted into 10−1, 10−2, 10−3, 10−4, and 10−5 with sterilized water. Additionally, 1 mL diluted soil suspension was mixed with TSM medium and spread on 9 cm Petri plates. All culture plates were incubated at 25 °C in the darkness for 3–5 days. Colony number of Trichoderma in different diluted soil suspensions was calculated. For purification, the single spore of the putative Trichoderma colonies was transferred on PDA plates and cultured at 25 °C.

4.3. Richness of Rhizosphere Fusarium and Trichoderma

The richness of Fusarium and Trichoderma in different soil samples was calculated using water content (%) and colony concentration (cfu∙g−1) on proper diluted soil suspension by the formula below (1) and (2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

4.4. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

The mycelia of fungal isolates were collected from 7-day-old isolates on PDA dishes and then ground in liquid nitrogen with a disposable pellet pestle. Total genomic DNA of all isolates was extracted using a SP Fungal DNA Kit (Aidlab Biotech, Chengdu, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The partial sequences of translation elongation factor 1-alpha (EF-1α) and RNA polymerase beta large subunit II (RPB2) were amplified for the identification of Fusarium species using the primer pairs EF1/EF2 [53] and RPB2-5f2/RPB2-7cr [54,55], respectively. The sequences of ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (rDNA ITS), EF-1α and RPB2 were amplified using primers ITS1/ITS4 [56], EF-728F/EF1LLErev [57] and fRPB2-5F/fRPB2-7cR [58] to identify Trichoderma species. PCR reaction was conducted in a total volume of 25 μL containing DNA template 1 μL, each primer 1 μL (10 μM), Taq PCR Mastermix (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) 12.5 μL, and DNase free water 9.5 μL. The fragments of rDNA ITS were amplified with the conditions of 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, initial extension at 72 °C for 30s, and remaining at 72 °C for 10 min. Amplification conditions for EF-1α and RPB2 were 5 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, initial extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and kept at 72 °C for 10 min. All primer sequences were listed in Supplementary Materials Table S1 and S2. PCR products were checked by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and sequenced using an ABI-PRISM3730 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA) in Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China),

4.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

Amplified sequences of EF-1α and RPB2 genes from candidate Fusarium isolates were blasted on Fusarium MLST databases, while sequences of rDNA ITS, EF-1α and RPB2 genes from candidate Trichoderma isolates were blasted on the NCBI database. Species of Fusarium and Trichoderma were identified based on the sequence similarity as compared to the reference species. For phylogenetic analysis, sequences of Fusarium and Trichoderma representative isolates, referred isolates and the outgroup isolate were edited and aligned with Clustalx 1.83, and characters were weighed equally. The referred isolates information of Fusarium and Trichoderma are listed in Supplementary materials Table S2.

For Fusarium species, MEGA 5.0 (https://www.megasoftware.net/index.php, accessed on 14 May 2021) was used to calculate and analyze the differences in their base composition, and phylogenetic trees were constructed using neighbor-joining method based on both EF-1α and RPB2 sequences for Fusarium spp., while those were performed for Trichoderma spp. based on either the combination of rDNA ITS and EF-1α, or the combination of rDNA ITS and RPB2, respectively. Clade support was inferred from 1000 bootstrap replicates, and alignment gaps were excluded. Novel sequence data were deposited in GenBank and the alignment in TreeBASE (www.treebase.org, accessed on 14 May 2021).

4.6. Pathogenicity Test of Fusarium Species

To test whether these Fusarium species identified from soybean rhizosphere are pathogenic, the representative isolates were randomly selected for pathogenicity test on the seedlings of soybean cultivar Nandou12, as described by Chang et al. (2020) [7].

4.7. In Vitro Antagonistic Effects of Trichoderma Strains on the Pathogenic F. oxysporum

For in vitro antagonistic assay, the representative strains of each Trichoderma species were randomly selected to test their antagonistic effects on the mycelium growth of F. oxysporum, a strong aggressive pathogen of soybean root rot. Both mycelial plugs of F. oxysporum and Trichoderma strains were inoculated on two opposite sides of 90 mm PDA plates with the distance of 75 mm, while only mycelial plug of F. oxysporum isolates inoculated on PDA plates were used as controls. Three plates were prepared for each isolate, and three independent experiments were conducted. All plates were incubated at 25 °C for 5 days in the darkness, and then the distance of F. oxysporum and Trichoderma on PDA plates was recorded. The percentage of mycelial inhibition (PMI) was calculated by the formula below (3).

| (3) |

For

For the visualization of hyphae interaction, on the confrontation culture, one sterile cover glass was inserted into PDA medium equidistant from Trichoderma and F. oxysporum at an angle of 45° and cultured at 28 °C in the dark. When both Trichoderma and F. oxysporum grew on the cover glass, the cover glass was taken out and observed under the compound microscope (Eclipse 80i, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and the mycelial interaction between Trichoderma and F. oxysporum was recorded and photographed.

4.8. Data Analysis

All data were recorded and processed using Microsoft office Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA). The data correlation was analyzed using generalized linear model (GLM) with quasi-poisson distribution for residuals, and statistical analysis was performed by Duncan’s test (p = 0.05) with GLM function using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). The composition proportion of Fusarium and Trichoderma spp. were calculated using the percentage of each species in total isolates from the corresponding soil sample, while isolation proportion of each species was evaluated using the percentage of each species in all isolates from four soil types. The difference in composition and isolation proportion of Fusarium or Trichoderma species in each cropping pattern was analyzed by Fisher’s exact test.

5. Conclusions

In this study, maize–soybean relay strip intercropping increased the density of beneficial Trichoderma and decreased the pathogenic Fusarium communities (in rhizosphere diseased soil) as compared to soybean monoculture. Intercropping also affected species composition and isolation proportion of rhizosphere Fusarium and Trichoderma communities. The change in the pathogenic Fusarium might be primarily driven by the beneficial Trichoderma strains by mycoparasitism interaction. Overall, these findings suggest that maize–soybean relay strip intercropping alters both pathogenic Fusarium and beneficial Trichoderma communities in soybean rhizosphere soil and leads to antagonistic development of the fungal community structure in plant health, which regulates the suppressive effect of this intercropping on soybean root rot.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Guoshu Gong for her kind technical support in fungal identification. We also thank Yang Huan for his help in field management and sampling.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens11040478/s1, Figure S1: Phylogenetic tree of ITS and EF-1α of Trichoderma spp. isolated from intercropping and monoculture; Table S1: Primers for PCR amplification of Fusarium spp. and Trichoderma spp.; Table S2: Information of referred isolates used for phylogenetic analysis of Fusarium and Trichoderm species; Table S3: Information of Fusarium isolates and GenBank accession information; Table S4: Information of Trichoderma isolates from different soil samples in monoculture and intercropping.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C., C.S. and T.L.; methodology, H.X., L.Y. and D.Z.; software, H.X., L.Y. and D.Z.; validation, D.W. and C.S.; formal analysis, H.X.; investigation, L.Y and M.N.; resources, X.W.; data curation, T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.X. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.C., M.Z. and D.W.; visualization, M.N. and X.W.; supervision, X.C.; project administration, X.C., W.C. and W.Y; funding acquisition, X.C., W.C. and W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 31801685), Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAAS-ASTIP) and the Breeding Key Project of the 14th five-year plan in Sichuan Province (Grant Number: 2021YFYZ0018).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Díaz-Arias M.M., Leandro L.F., Munkvold G.P. Aggressiveness of Fusarium species and impact of root infection on growth and yield of soybeans. Phytopathology. 2013;103:822–832. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-08-12-0207-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman G.L., Chang H.X., Leandro L.F. Research advances and management of soybean sudden death syndrome. Crop Prot. 2015;73:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2015.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandara A.Y., Weerasooriya D.K., Bradley C.A., Allen T.W., Esker P.D. Dissecting the economic impact of soybean diseases in the United States over two decades. PLoS ONE. 2015;15:e0231141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson B.D., Hansen J.M., Windels C.E., Helms T.C. Reaction of soybean cultivars to isolates of Fusarium solani from the Red River Valley. Plant Dis. 1997;81:664–668. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.6.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J.X., Xue A.G., Cober E.R., Morrison M.J., Zhang H.J., Zhang S.Z., Gregorich E. Prevalence, pathogenicity and cultivar resistance of Fusarium and Rhizoctonia species causing soybean root rot. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2013;93:221–236. doi: 10.4141/cjps2012-223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei W., Xu Y.L., Zhu L., Zhang S.L., Li S. Impact of long-term continuous cropping on the Fusarium population in soybean rhizosphere. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014;25:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang X.L., Yan L., Naeem M., Khaskheli M.I., Zhang H., Gong G.S., Zhang M., Song C., Yang W.Y., Liu W.G., et al. Maize/soybean relay strip intercropping reduces the occurrence of Fusarium root rot and changes the diversity of the pathogenic Fusarium species. Pathogens. 2020;9:211. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9030211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang X.L., Dai H., Wang D.P., Zhou H.H., He W.Q., Fu Y., Ibrahim F., Zhou Y., Gong G.S., Shang J., et al. Identification of Fusarium species associated with soybean root rot in Sichuan Province. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018;151:563–577. doi: 10.1007/s10658-017-1410-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao X., Wu M., Xu R., Wang X., Pan R., Kim H.J., Liao H. Root interactions in a maize/soybean intercropping system control soybean soil-borne disease, red crown rot. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e95031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akamatsu H., Kato M., Ochi S., Mimuro G., Matsuoka J., Takahashi M. Variation in the resistance of Japanese soybean cultivars to Phytophthora root and stem rot during the early plant growth stages and the effects of a fungicide seed treatment. Plant Pathol. J. 2019;35:219–233. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.11.2018.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sepiol C.J., Yu J., Dhaubhadel S. Genome-wide identification of chalroot specific GmCHRs and Phytophthora sojae cone reductase gene family in soybean: Insight into resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:2073. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.02073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naeem M., Munir M., Li H.J., Raza M.A., Song C., Wu X.L., Irshad G., Khalid M.H.B., Yang W.Y., Chang X.L. Transcriptional responses of Fusarium graminearum interacted with soybean to cause root rot. J. Fungi. 2021;7:422. doi: 10.3390/jof7060422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naseri B. Epidemics of Rhizoctonia root rot in association with biological and physicochemical properties of field soil in bean crops. J. Phytopathol. 2013;161:397–404. doi: 10.1111/jph.12077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naseri B. Bean production and Fusarium root rot in diverse soil environments in Iran. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014;14:177–188. doi: 10.4067/S0718-95162014005000014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.John R.P., Tyagi R.D., Prévost D., Brar S.K., Pouleur S., Surampalli R.Y. Mycoparasitic Trichoderma viride as a biocontrol agent against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. adzuki and Pythium arrhenomanes and as a growth promoter of soybean. Crop Prot. 2010;29:1452–1459. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berendsen R.L., Pieterse C.M.J., Bakker P.A.H.M. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L.Y., Xie Y.S., Cui Y.Y., Xu J., He W., Chen H.G., Guo J.H. Conjunctively screening of biocontrol agents (BCAs) against fusarium root rot and fusarium head blight caused by Fusarium graminearum. Microbiol. Res. 2015;177:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benitez T., Rincon A.M., Limon M.C., Codon A.C. Biocontrol mechanisms of Trichoderma strains. Int. Microbiol. 2004;7:249–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wending R. Trichodema lignorum as a parasite of other soil fungi. Phytopathology. 1932;22:837–845. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harman G.E., Howell C.R., Viterbo A., Chet I., Lorito M. Trichoderma species-opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izquierdo-García L.F., González-Almario A., Cotes A.M., Moreno-Velandia C.A. Trichoderma virens Gl006 and Bacillus velezensis Bs006: A compatible interaction controlling Fusarium wilt of cape gooseberry. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:6857. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63689-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynch J.M., Lumsden R.D., Atkey P.T., Ousley M.A. Prospects for control of Pythium damping-off of lettuce with Trichoderma, Gliocladium, and Enterobacter spp. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 1991;12:95–99. doi: 10.1007/BF00341482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anees M., Tronsmo A., Edel-Hermann V., Hjeljord L.G., Héraud C., Steinberg C. Characterization of field isolates of Trichoderma antagonistic against Rhizoctonia solani. Fungal. Biol. 2010;114:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lahlali R., Hijri M. Screening, identification and evaluation of potential biocontrolfungal endophytes against Rhizoctonia solani AG3 on potato plants. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010;311:152–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J.Y., Lu C.G., Liu T., Liu W.C., Su H.J. Trichoderma brevicompactum BF06, a novel strain with potential for biocontrol of soil-borne diseases and promotion of plant growth of cucumber. Chin. J. Biol. Control. 2018;34:449–460. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y., Tian C., Xiao J.L., Wei L., Tian Y., Liang Z.H. Soil inoculation of Trichoderma asperellum M45a regulates rhizosphere microbes and triggers watermelon resistance to Fusarium wilt. AMB Express. 2020;10:189. doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-01126-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cotxarrera L., Trillas-Gay M.I., Steinberg C., Alabouvette C. Use of sewage sludge compost and Trichoderma asperellum isolates to suppress Fusarium wilt of tomato. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002;34:467–476. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00205-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hermosa R., Viterbo A., Chet I., Monte E. Plant-beneficial effects of Trichoderma and of its genes. Microbiology. 2012;158:17–25. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.052274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdelrahman M., Abdel-Motaal F., El-Sayed M., Jogaiah S., Shigyo M., Ito S.I., Tran L.S.P. Dissection of Trichoderma longibrachiatum-induced defense in onion (Allium cepa L.) against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepa by target metabolite profiling. Plant Sci. 2016;246:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alfiky A., Weisskopf L. Deciphering Trichoderma-Plant-Pathogen Interactions for Better Development of Biocontrol Applications. J. Fungi. 2021;7:61. doi: 10.3390/jof7010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolfe S.A., Griffiths J., Ton J. Crying out for help with root exudates: Adaptive mechanisms by which stressed plants assemble health-promoting soil microbiomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019;49:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen J., Zhou L., Din I.U., Arafat Y., Li Q., Wang J. Antagonistic activity of Trichoderma spp. against Fusarium oxysporum in rhizosphere of Radix pseudostellariae triggers the expression of host defense genes and improves its growth under long-term monoculture system. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:579920. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.579920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang F., Wang X.C., Liao D.P., Lu F.Z., Gao R.C., Liu W.G., Yong T.W., Wu X.L., Du J.B., Liu J., et al. Yield response to different planting geometries in maize-soybean relay strip intercropping systems. Agron. J. 2015;107:296–304. doi: 10.2134/agronj14.0263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen P., Du Q., Liu X.N., Zhou L., Hussain S., Lei L., Song C., Wang X.C., Liu W.G., Yang F., et al. Effects of reduced nitrogen inputs on crop yield and nitrogen use efficiency in a long-term maize-soybean relay strip intercropping system. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0184503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song C., Wang Q.L., Zhang X.F., Sarpong C.K., Wang W.J., Yong T.W., Wang X.C., Wang Y., Yang W.Y. Crop productivity and nutrients recovery in maize-soybean additive relay intercropping systems under subtropical regions in Southwest China. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2020;14:373–387. doi: 10.1007/s42106-020-00090-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song C., Sarpong C.K., Zhang X.F., Wang W.J., Wang L.F., Gan Y.F., Yong T.W., Chang X.L., Wang Y., Yang W.Y. Mycorrhizosphere bacteria and plant-plant interactions facilitate maize Pacquisition in an intercropping system. J. Clean. Prod. 2021;314:127993. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su B.Y., Liu X., Cui L., Xiang B., Yang W.Y. Suppression of weeds and increases in food production in higher crop diversity planting arrangements: A case study of relay intercropping. Crop. Sci. 2018;58:1729–1739. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2017.11.0670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X., Rahman T., Song C., Su B., Yang F., Yong T.W., Wu Y.S., Zhang C.Y., Yang W.Y. Changes in light environment, morphology, growth and yield of soybean in maize-soybean intercropping systems. Field Crop. Res. 2017;200:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2016.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Du J.B., Han T.F., Gai J.Y., Yong T.W., Sun X., Wang X.C. Maize-soybean strip intercropping: Achieved a balance between high productivity and sustainability. J. Integr. Agric. 2018;17:747–754. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(17)61789-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren L.X., Su S.M., Yang X.M., Xu Y.C., Huang Q.W., Shen Q. Intercropping with aerobic rice suppressed Fusarium wilt in watermelon. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008;40:834–844. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X.G., Yu G.B., Wu F.Z. Effects of intercropping cucumber with onion or garlic on soil enzyme activities, microbial communities and cucumber yield. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2011;47:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ejsobi.2011.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hage-Ahmed K., Krammer J., Steinkellner S. The intercropping partner affects arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici interactions in tomato. Mycorrhiza. 2013;23:543–550. doi: 10.1007/s00572-013-0495-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beyer M., Klix M.B., Klink H., Verreet J.A. Quantifying the effects of previous crop, tillage, cultivar and triazole fungicides on the deoxynivalenol content of wheat grain-a review. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2006;113:241–246. doi: 10.1007/BF03356188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J.B., Xu Y.L., Wei W. Comparing different methods for isolating Fusarium from soybean rhizosphere soil. Soybean Sci. 2008;1:106–112. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jie W.G., Bai L., Yu W.J., Cai B.Y. Analysis of interspecific relationships between Funneliformis mosseae and Fusarium oxysporum in the continuous cropping of soybean rhizosphere soil during the branching period. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2015;25:1036–1051. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2015.1028891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Setälä H., McLean M.A. Decomposition rate of organic substrates in relation to the species diversity of soil saprophytic fungi. Oecologia. 2004;139:98–107. doi: 10.1007/s00442-003-1478-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pérez-Brandán C., Huidobro J., Grümberg B., Scandiani M.M., Luque A.G., Meriles J.M., Vargas-Gil S. Soybean fungal soil-borne diseases: A parameter for measuring the effect of agricultural intensification on soil health. Can. J. Microbiol. 2014;60:73–84. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2013-0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lian T.X., Mu Y.H., Ma Q.B., Cheng Y.B., Gao R., Cai Z.D., Jiang B., Nian H. Use of sugarcane–soybean intercropping in acid soil impacts the structure of the soil fungal community. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:14488. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32920-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Djonovic S., Vargas W.A., Kolomiets M.V., Horndeski M., Wiest A., Kenerley C.M. A proteinaceous elicitor Sm1 from the beneficial fungus Trichoderma virens is required for induced systemic resistance in maize. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:875–889. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.103689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jogaiah S., Abdelrahman M., Tran L.S.P., Ito S.I. Different mechanisms of Trichoderma virens-mediated resistance in tomato against Fusarium wilt involve the jasmonic and salicylic acide pathways. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018;19:870–882. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sivan A., Chet I. Degradation of fungal cell walls by lytic enzymes from Trichoderma harzianum. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1989;135:675–682. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elad Y., Chet I., Henis Y. Biological control of Rhizoctonia solani in strawberry fields by Trichoderma harzianum. Plant Soil. 1981;60:245–254. doi: 10.1007/BF02374109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Donnell K., Kistler H.C., Cigelnik E., Ploetz R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing Panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2044–2049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Donnell K., Sutton D.A., Rinaldi M.G., Sarver B.A.J., Balajee S.A., Schroers H.-J., Summerbell R.C., Robert V.A.R.G., Crous P.W., Zhang N., et al. Internet-accessible DNA sequence database for identifying Fusarium from human and animal infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:3708–3718. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00989-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Donnell K., Rooney A.P., Proctor R.H., Brown D.W., McCormick S.P., Ward T.J., Frandsen R.J.N., Lysøe E., Rehner S.A., Aoki T., et al. Phylogenetic analyses of RPB1 and RPB2 support a middle Cretaceous origin for a clade comprising all agriculturally and medically important fusaria. Fungal. Genet. Biol. 2013;52:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White T.J., Bruns T.D., Lee S.B., Taylor J.W. Amplification sand direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. 1990;18:315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jaklitsch W.M., Komon M., Kubicek C.P., Druzhinina I.S. Hypocrea voglmayrii sp. nov. from the Austrian Alps represents a new phylogenetic clade in Hypocrea/Trichoderma. Mycologia. 2005;97:1365–1378. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y.J., Whelen S., Hall B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.