Abstract

We report the first detailed pharmacokinetic assessment of intrarectal (i.r.) artesunate (ARS) in African children. Artesunate was given intravenously (i.v.; 2.4 mg/kg of body weight) and i.r. (10 or 20 mg/kg formulated as 50- or 200-mg suppositories [Rectocaps]) in a crossover study design to 34 Ghanaian children with moderate falciparum malaria. The median relative bioavailability of dihydroartemisinin (DHA), the active antimalarial metabolite of ARS, was higher in the low-dose i.r. group (10 mg/kg) than in the high-dose i.r. group (20 mg/kg) (58 versus 23%; P = 0.018). There was wide interpatient variation in the area under the concentration-time curve after i.r. ARS administration (up to 9-fold in the high-dose group and 20-fold in the low-dose group). i.r. administered ARS was more rapidly absorbed in the low-dose group than the high-dose group (median [range] absorption half-lives, 0.7 h [0.3 to 1.24 h] versus 1.1 h [0.6 to 2.7 h] [P = 0.023]. i.r. administered ARS was eliminated with a median (range) half-life of 0.8 h (0.4 to 2.7 h) (low-dose group and 0.9 h (0.1 to 2.5 h) (high-dose group) (P = 1). The fractional clearances of DHA were 3.9, 2.6, and 1.5 liters/kg/h for the 20-mg/kg, 10-mg/kg and i.v. groups, respectively (P = 0.001 and P = 0.06 for the high-and low-dose i.r. groups compared with the i.v. groups, respectively). The median volumes of distribution for DHA were 1.5 liters kg (20 mg/kg, i.r. group), 1.8 liters/kg (10 mg/kg, i.r. group), and 0.6 liters/kg (i.v. group) (P < 0.05 for both i.r. groups compared with the i.v. group). Parasite clearance kinetics were comparable in all treatment groups. i.r. administered ARS may be a useful alternative to parenterally administered ARS in the management of moderate childhood malaria and should be studied further.

In rural tropical areas, patients frequently present with malaria and require urgent therapy. Facilities may not exist for parenteral drug administration, and oral dosing is precluded by obtundation or vomiting. In these circumstances, the rectal route of administration may allow initiation of antimalarial therapy while patients await transfer to hospital, a process that may take many hours.

Artesunate (ARS) is a water-soluble hemisuccinate dihydroartemisinin (DHA) derivative being developed for the treatment of malaria and is particularly valuable against multidrug-resistant infections (2, 13). ARS is currently formulated for administration by the oral and parenteral routes (3, 11). ARS suppositories (Rectocaps; 50 mg of artesunate; Mepha Pharmaceuticals Ltd.) Aesch-Basle, Switzerland) have recently undergone preliminary assessment in Gabonese children (8). However, formal bioavailability studies with this formulation are lacking. Circulating ARS is quickly converted to DHA by blood esterases and hepatic metabolism (14). As DHA is the principal antimalarial metabolite of ARS, the bioavailability of DHA was studied by comparing intrarectally (i.r.) and intravenously (i.v.) administered ARS in Ghanaian children with moderate malaria. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection, currently the most precise and sensitive assay, was used to measure ARS and DHA levels. This crossover study was also designed to test the hypothesis that within the first 24 h there is no disease effect on the pharmacokinetics of ARS. These studies are critical to the design of larger (phase III-IV) studies seeking to use rectal ARS to reduce mortality from malaria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design description.

This was an open, randomized, crossover comparison between i.v. ARS and ARS suppositories conducted on a pediatric research ward at Komfo-Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana, from August to October 1996. This study was approved by The Committee of Research, Publication and Ethics of the School of Medical Sciences, University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana, and the Review Board of the World Health Organization. A computer-generated randomization list allocating patients to one of three treatment categories was prepared (in permuted blocks of 12 patients). The treatment category for each patient was provided in an opaque sealed envelope opened only when a patient entered the study. Treatment categories were as follows: group I, i.r. ARS at 10 mg/kg of body weight, followed 12 h later by i.v. ARS at 2.4 mg/kg; group II, i.r. ARS at 20 mg/kg, followed 12 h later by i.v. ARS at 2.4 mg/kg; and group III, i.v. ARS at 2.4 mg/kg, followed 12 h later by i.r. ARS at 20 mg/kg. The doses of i.r. ARS were based on preliminary pharmacodynamic analysis of a similar study of i.r. ARS in Thai adults with moderate malaria (S. Looareesuwan, personal communication).

Inclusion criteria.

Patients aged 18 months to 7 years (inclusive) with a diagnosis of moderate Plasmodium falciparum malaria were eligible, provided that relatives gave informed consent for the patients to participate in the study. The diagnosis of moderate malaria was based on clinical and laboratory evaluations after exclusion of severe malaria (defined below). Patients with ≥1% asexual P. falciparum parasitemia who required treatment with parenteral rather than oral antimalarials were selected. Clinical features that suggested a need for parenteral treatment were a history of frequent (more than once) and/or recent (within 12 h) vomiting, drowsiness, obtundation (i.e., an apathetic response to painful stimuli such as capillary blood sampling or venipuncture) or prostration (i.e., difficulty or inability to sit up, stand up, or walk unaided according to the child's age) (16). If patients developed one or more features of severe malaria, they were excluded from further study and were rescued immediately with i.v. ARS (2.4 mg/kg) and continued to receive parenteral antimalarial treatment until they could tolerate oral medication.

Exclusion criteria.

Severe malaria was defined as the presence of one or more of the following clinical or laboratory features: cerebral malaria (coma score of ≤2 on the Blantyre scale, with coma persisting at least 1/2 h after the last seizure), hypoglycemia (capillary or venous glucose concentration, ≤2.2 mmol/liter) or hyperlactatemia (capillary or venous lactate concentration, ≥5 mmol/liter), or severe anemia (packed cell volume [PCV], <15%) (16). In addition, children who had more than one short-lived (<5-min) convulsion after admission were also excluded from further study and were rescued with i.v. ARS. Patients with anatomical abnormalities of the rectum or acute diarrhea present during the preceding 12 h (precluding administration of suppositories) were also excluded.

Screening of referred patients.

Patients were selected for study after referral from the outpatient department or from general pediatric wards. After a brief history and examination, screening for parasitemia, anemia, and blood glucose and lactate concentrations was carried out with capillary or venous blood. Parasitemia was confirmed and quantitated by using Field's stain (by counting the number of parasites per 1,000 red cells on a thin film or per 200 white cells on a thick film) by an experienced microscopist, and the PCV was estimated by using a microhematocrit centrifuge (Hawksley). Whole-blood lactate and glucose levels were measured on an automated glucose-lactate analyzer (YSI 2300; YSI Instruments Ltd.).

Antimalarial drugs.

Two study drugs were used: ARS suppositories (Rectocaps; capsules with 200 or 50 mg of ARS; Mepha Pharmaceuticals Ltd.), formulated as described previously (8), and parenteral ARS (Guilin No. 2 Factory, Guangxi, People's Republic of China). No more than two suppositories (inserted within 5 s of each other) were administered to a patient. Suppositories were administered whole, without the use of lubricant, and the actual dose administered was the nearest approximation to the theoretical dose for each rectal treatment category. Children were observed for 30 min to ensure that the suppository was retained. If rectal drug was expelled within 30 min of administration, a single attempt to readminister a further dose was made and the start of the study was taken to be at the time of administration of second dose. If this failed, the patient was rescued with i.v. ARS. ARS was chosen because it is effective against severe malaria and has been used locally (1), as well as to minimize any potential for drug interactions with nonartemisinin derivatives. i.v. doses of ARS were reconstituted as recommended by the manufacturer immediately before administration (in 5 ml syringes). Drug was given rapidly (as a bolus in <5 s) through a butterfly needle (Venisystem; Abbott Laboratories, Kent, United Kingdom) at a site separate from the sampling cannula site.

Sampling and storage protocols.

A fine (20- or 22-gauge) i.v. cannula (Medicut) was inserted into a peripheral vein for sampling purposes, and an admission plasma sample (from 1 ml of whole blood) was obtained. After ARS administration, sampling (1 ml of whole blood) for ARS and DHA assays was done at the following times: 15, 30, 60, and 90 min and 2, 4, 8, and 12 h. An identical sampling schedule was followed when crossover treatment was begun immediately after retrieval of the sample at 12 h. Whole blood was collected and placed into prechilled, heparinized (30 IU; Unihep; Leo, Bucks, United Kingdom) microcentrifuge tubes, and the plasma was separated within 15 min of collection (12,000 × g, 3 min). Storage and transport of specimens were at −70°C or below.

Patient monitoring.

Patients were under the care of dedicated study nurses and physicians. After study entry, vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, axillary temperature, and coma score) were recorded at the same time as blood sampling for pharmacokinetic analyses and every 6 h thereafter until discharge. Parasitemia, PCV, and blood glucose and lactate levels were monitored every 4 h until the parasites had cleared. A detailed daily neurological examination including assessment of external ocular movements, cerebellar signs, and pupillary reflexes was also carried out.

Concomitant therapy.

Fluids were administered i.v., if clinically indicated, to maintain circulating intravascular volume. Fever was treated with acetaminophen suspension (Calpol pediatric; Warner Lambert, Hants, United Kingdom), and seizures were managed with phenobarbital (Gardenal; May and Baker, Dagenham, United Kingdom) and i.v. diazepam (Valium; Roche, Herts, United Kingdom), as indicated. Severe anemia (PCV, <15%) was corrected by blood transfusion with blood screened for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus. i.r. administration of nonstudy drug was avoided.

Once the patients were able to tolerate oral medication, they were given a course of chloroquine, conventionally considered curative in areas with chloroquine-sensitive P. falciparum (25 mg of base total dose [Nivaquine; Rhône Poulenc, West Malling, United Kingdom] per kg in three daily doses). Patients with a history of intolerance to chloroquine received a single age-adjusted curative dose of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (<4 years, 1/2 tablet; 5 to 6 years, 1 tablet; 7 years, 1 1/2 tablets; Fansidar; Roche). Patients still requiring parenteral therapy 24 h after admission continued with i.v. ARS (1.2 mg/kg every 12 h until they were able to tolerate oral treatment). Some children were given ferrous fumarate syrup (2.5 to 5 ml once daily; Fersamal; Forley, Harrow, United Kingdom) and folic acid (5 mg once daily; Cox Continental, Devon, United Kingdom) for 14 days at the time of discharge and after the bioavailability study had been completed.

Follow-up.

Patients attended two follow-up appointments between 7 and 30 days after entry into the study. A full physical examination, including neurological assessment, and screening laboratory tests were carried out. Relatives were encouraged to attend earlier if the child developed fever or other symptoms. Patients with parasitemia at follow-up were treated with oral quinine (10 mg of base quinine sulfate [Edikay Pharmacy, Kumasi, Ghana] per kg three times daily) and asked to attend a further follow-up appointment. For children who could not swallow whole tablets, the tablets were crushed, mixed with water, and given in syrup made from sugar and water.

Drug assay.

The assay of ARS and DHA in plasma samples was by a specific and selective HPLC method with electrochemical detection operating in the reductive mode (15). For ARS, the within-day and day-to-day coefficients of variation (CVs) were 4.2 and 3.1%, respectively, at 30 ng/ml and 7.4 and 9.6%, respectively, at 60 ng/ml. The within-day CV for ARS at 110 ng/ml was 3.4%. In addition, the CVs for day-to-day experiments at concentrations of 100 and 200 ng/ml were 8.0 and 1.6%, respectively. For DHA, the within-day and day-to-day CVs were 2.6 and 8.3%, respectively, at 30 ng/ml and 4.9 and 5.9%, respectively, at 60 ng/ml. At a concentration of 110 ng/ml, the within-day CV was 2.8%. For day-to-day experiments the CVs were 6.9 and 0.5% for concentrations of 100 and 200 ng/ml, respectively. The limit of quantification of ARS and DHA in spiked plasma samples (corresponding to a peak three times the baseline noise at 0.005 absorbance units, full scale) was 4 ng/ml for both compounds. Assays were conducted according to standards of good laboratory procedures.

Pharmacokinetic analyses.

Pharmacokinetic modeling was carried out with WinNonlin software (version 3.0; Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, Calif.). The sampling frequency for modeling of ARS concentrations was inappropriate for detailed pharmacokinetic analysis for many patients because the elimination half-life (t1/2; estimated in a subsequently published study (3) is <5 min. Fifteen patients receiving i.v. ARS had sufficient data with which to develop a preliminary one-compartment first-order model to estimate elimination constants (k10). These were entered as initial parameters when the pharmacokinetic behavior of DHA was modeled.

For modeling of DHA, conversion of ARS to DHA was assumed to be completed (17). When data on the elimination kinetics of ARS were lacking, a mean value for the i.v. group was used as an initial estimate for k10. For i.v. drug the Gauss-Newton minimization method was used, and for suppositories the Nelder-Mead minimization method was used. Goodness of fit was examined by the standard criteria (inspection of model compared with data, examination of residuals, and use of other measures such as the Aikake Information Criterion; User Guide for WinNonlin, Scientific Consulting Inc.) (7) as well as by comparison of modeled and observed estimates for values of lag time, maximum concentration of drug in serum (Cmax), and time to Cmax (Tmax). As relative bioavailability (f), which is defined as (AUCi.r./AUCi.v.) × (dosei.v./dosei.r.), where AUC is the area under the concentration-time curve, could not be estimated for all patients, values for fractional clearance (CL/f) and apparent volume of distribution (V/f) are also given. Doses were converted to molar equivalents to allow comparability between ARS (molecular mass, 384) and DHA (molecular mass, 284) levels.

Statistical analyses.

Data were analyzed by using SYSTAT (version 5.2; SYSTAT, Inc., Evanston, Ill.) or Stata (version 5; Stata Corporation, College Station, Tex.). Normally distributed data were compared by parametric tests (Student's t test or multiple analysis of variance), and nonnormally distributed data were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test. Pearson's product moment coefficient was used for correlational analysis. Measures repeated over time were compared by repeat measures analysis.

RESULTS

One hundred forty-three children were screened for eligibility for entry into this study. Of these, 113 (79%) had asexual P. falciparum parasites on blood film examination. Thirty-four (30%) patients were excluded from further study because of a history of recent chloroquine pretreatment (n = 10) or parasitemia of <1% (n = 24). Twelve patients (11%) were ineligible because they had severe malaria, and 22 (20%) patients had uncomplicated malaria (absence of features of moderate malaria as defined in Materials and Methods); one patient had severe diarrhea. Forty four patients were therefore eligible for further study, and 36 were randomized. Relatives of the remainder were either unavailable or declined consent or the patients could not be randomized because of other constraints (such as a lack of availability of beds on the research ward).

Withdrawals and exclusions. (i) Suppository treatment.

Two (of 12) patients in group I did not have plasma samples because one expelled suppositories on two occasions and the other patient's samples were spoiled. Three patients in groups II and III had insufficient or spoiled plasma, two patients developed severe disease (see below), two patients had plasma concentration-time profiles that were not adequately modeled, and one patient was withdrawn because of difficulty in obtaining samples, leaving 16 of 24 patients with useful information.

(ii) i.v. treatment.

Among the patients receiving i.v. ARS (all groups), 1 patient was withdrawn because of expelled suppositories (as described above), 2 patients developed severe disease (see below), 1 patient was withdrawn because of difficulty in obtaining samples (as described above), 5 patients had spoiled samples, 1 patient had a large carryover of drug from previous suppository treatment, and 1 patient had plasma concentration-time profiles that were not adequately modeled, leaving 25 of 36 patients with useful information.

The histories of two patients (both in group II) who were withdrawn from study the because of worsening disease follow. For patient AS3, admission parasitemia was 5.5%, the Blantyre coma score was 5, PCV was 18%, the glucose level was 3.7 mmol/liter, and the lactate level was 2.9 mmol/liter. One hour and 40 min later, he developed recurrent right-sided focal seizures, hyperlactatemia (5.6 mmol/liter), and severe anaemia (PCV, <15%) but was rescued with i.v. ARS and recovered fully. For patient AS14, admission parasitemia was 1.7%, the Blantyre coma score was 5, PCV was 24%, the glucose level was 8.3 mmol/liter, and the lactate level was 3.4 mmol/liter. Seven hours and 40 min later he developed recurrent generalized seizures and coma (Blantyre coma score, <2) and then bilateral retinal hemorrhage. After the administration of i.v. ARS, he remained comatose for approximately 24 h and then recovered. Cerebrospinal fluid examination ruled out bacterial meningitis.

Admission characteristics of patients.

Patients frequently had more than one defining feature of moderate malaria. Twenty-five (69%) had a history of frequent or recent vomiting, 22 (61%) were prostrate, and 4 (11%) were obtunded. Two patients (6%) had a history of a single generalized convulsion. The admission clinical, laboratory, and parasitological characteristics of the patients in each treatment category are summarized in Table 1. Treatment groups were comparable for these baseline variables. The administered doses of i.r. ARS are also included in Table 1. Only one patient required a second dose, as the first suppository was expelled intact within 10 min of administration.

TABLE 1.

Baseline clinical variables of the children in the three groupsa

| Variable | Group I (n = 12) | Group II (n = 12) | Group III (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| i.r. dose (mg/kg) administered | 9.3 (1.9) | 18.9 (2) | 18.9 (2.6) |

| i.r. dose range (mg/kg) | 6.9–11.8 | 15.4–21.9 | 15.6–22.9 |

| Age (mo) | 51 (20) | 47 (19) | 58 (20) |

| Sex (no. of boys/no. of girls) | 6/6 | 5/7 | 5/7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 14.3 (1.3)b | 14.6 (1.9) | 14.6 (1.5) |

| Axillary temp (°C) | 38.2 (1) | 38.5 (1.1) | 38.4 (0.9) |

| Pulse (no. of beats/min) | 131 (13) | 139 (16) | 136 (15) |

| Respiration (no./min) | 35 (8) | 33 (6) | 34 (7) |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | 73 (9) | 68 (7) | 71 (6) |

| Hepatomegaly (cm)c | 1.25 (0–4) | 2 (0–5) | 2.5 (0–7) |

| Splenomegaly (cm)c | 1.25 (0–5) | 0 (0–2) | 0.5 (0–7) |

| PCV (%) | 32 (4) | 30 (7) | 28 (5) |

| Plasma lactate level (geometric mean mmol/liter) | 2.2 (1.1–4.3) | 2.4 (1.2–3.8) | 3.0 (1.4–4.8) |

| Plasma glucose level (mmol/liter) | 4.9 (1.1) | 5.4 (1.5) | 7 (2.4) |

| Parasitemia | |||

| Median % (range) | 2.7 (1–5.6) | 3.5 (1.3–14.4) | 4.2 (2.2–22) |

| Geometric mean/μl | 95,040 | 130,670 | 183,120 |

| Interquartile range | 64,060–138,410 | 69,710–239,270 | 114,550–311,490 |

Data are mean (standard deviation) or median (range) values, unless stated otherwise. Group I, 10 mg of ARS/kg i.r.; group II, 20 mg of ARS/kg i.r.; group III, 2.4 mg of ARS/kg i.v.

n = 10.

Measured below the costal margin.

Response to antimalarial treatment and hospital course.

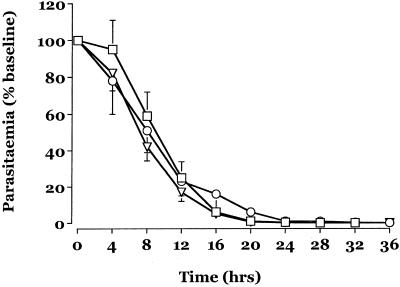

Figure 1 displays the mean change from the baseline parasitemia for the three treatment groups in the first 24 h. There were no significant differences between the three treatment groups during this time. There were no differences in parasite clearance parameters between the i.v. and i.r. routes of ARS administration and no difference due to dose. Table 2 summarizes other parasitological and clinical measures of recovery. The median fall from the baseline parasitemia at 12 h (∼80% for all groups) reflects the comparable activity of ARS in all three groups. There were no adverse events attributable to study drugs.

FIG. 1.

Mean ± standard error of the mean change in parasitemia after admission for patients in group I (triangles), group II (squares), and group III (circles).

TABLE 2.

Measures of recovery in treatment groupsa

| Variable | Group I (n = 11) | Group II (n = 10) | Group III (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC12 (%) | 85 (48–100) | 78 (4–100) | 86 (8–100) |

| PC50 (h) | 8 (3.75–9.25) | 7 (3.75–14.75) | 7.5 (2–18) |

| PC90 (h) | 13 (7.25–18.75) | 13.6 (10.5–19.75) | 14 (3.75–28) |

| PCT (h) | 20 (16–42) | 22 (16–32) | 24 (16–35) |

| FCT (h) | 2 (0–20) | 1.5 (0.25–8) | 4 (0–14) |

| Plasma lactate level (mmol/liter) at 12 h | 0.814 (0.35–1.62) | 1.13 (0.81–1.37) | 1.21 (0.83–4.14) |

| Plasma glucose level (mmol/liter) at 12 h | 4.84 (2.41–13.2) | 5.19 (3.31–7.56) | 6.2 (5.03–11.9) |

| PCV (%) at 12 h | 28 (20–32) | 28 (16–34) | 25 (18–35) |

| Geometric mean parasitemia at 12 h (no. of parasites/μl) | 6,933 (280–59,786) | 11,070 (400–160,768) | 14,765 (240–232,988) |

| PCV (%) at 7 day of follow-up | 29 (15–39) | 29 (23–35) | 28 (25–31) |

| PCV (%) at late follow-up (days 13 to 30) | 35 (32–40) | 33 (25–38) | 32 (25–33) |

| No. of patients with positive blood film at follow-up (days 13 to 30) | 3 | 2 | 4 |

Data are median (range) values, unless stated otherwise; PC12, percent fall in parasitemia at 12 h; PC50, time for parasitemia to fall to 50% of baseline value; PC90, time for parsitemia to fall to 90% of baseline value; PCT, parasite clearance time; FCT, fever clearance time. Group I, 10 mg of ARS/kg i.r.; group II, 20 mg of ARS/kg i.r.; group III, 2.4 mg of ARS/kg i.v.

Chloroquine pretreatment.

Patients with a positive history of chloroquine treatment were excluded from this study. Subsequent analysis of plasma for chloroquine (cutoff, 5 ng/ml), pyrimethamine, and quinine levels (dipsticks were kindly supplied by T. Eggelte) showed that five patients had detectable plasma chloroquine levels on admission (one patient in group I, one patient in group II, and three patients in group III). No patients had detectable quinine or pyrimethamine levels. Parasite clearance parameters were not significantly different for those patients with detectable chloroquine at the baseline and the remainder of the patients.

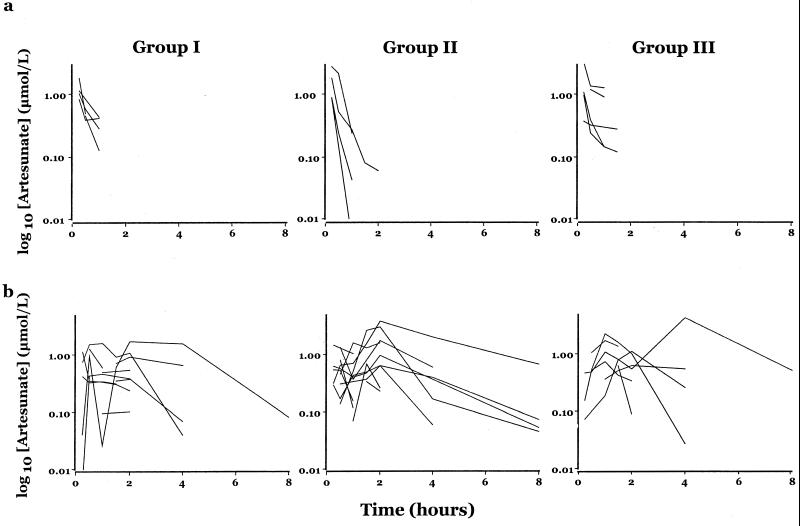

Pharmacokinetic analyses. ARS.

In the absence of more detailed pharmacokinetic analyses, plasma concentration-time profiles for ARS for each of the three treatment groups are displayed in Fig. 2. Compared with patients receiving suppositories, the i.v. route gave much higher peak concentrations (more than five fold), although ARS was also eliminated more rapidly in this group. Time to peak ARS levels may take hours in patients receiving suppositories and suggests that the rate of absorption of ARS may limit the clearance of drug given rectally.

FIG. 2.

(a) Plasma ARS-versus-time profiles after i.v. administration of ARS. (b) Plasma ARS-versus-time profiles after i.r. administration of ARS.

DHS. (i) i.v. route.

An open one-compartment model with first-order appearance and elimination kinetics with no lag time best fits the data. The median (range) correlation coefficient for this model for the i.v. route is 0.99 (0.85 to 1.00). Preliminary analysis (of both i.v. and i.r. data) with two-compartment models did not improve the goodness of fit, as judged by the criteria, outlined in Materials and Methods.

The median t1/2 for DHA was 66% longer in children receiving i.v. ARS after administration of suppositories (groups I and II; median t1/2, 32 min) than in those receiving i.v. ARS first (group III; median t1/2, 19.3 min) (P = 0.009). Consequently, all pharmacokinetic data for i.v. ARS were not pooled for analysis. For comparisons with the data for i.v. ARS, group III i.v. data are used (i.e., data for patients who received i.v. ARS first). There were no differences in any pharmacokinetic parameter in children who received i.v. ARS 12 h after admission (groups I and II), so data for these groups were pooled. Data for these groups are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for DHA (after administration of ARS) derived from one-compartment modeling in children with moderate malariaa

| Group | Actual doseb (mean±SD, μmol/kg) | V/f (liters/kg) | V (liters/kg) | CL/f (liters/kg/h) | CL (liters/kg/h) | t1/2 (h) | tlag (h) | tabs (h) | AUC (μmol · h/liter) | Relative bioavailability (%) | Tmax (h) | Cmax (μmol/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I (n = 10) | 24 (5.2) | 4.4 (1.8–14.4) | 1.9 (1–6)b | 2.6 (1–22.3) | 1.3 (0.9–2)b | 0.79 (0.41–2.69) | 0.63 (0–1.36) | 0.69 (0.3–1.24) | 9.8 (1.4–28.2) | 58 (24–131)b | 1.7 (0.9–3.2) | 2.4 (0.8–5.8) |

| Group II and III (n = 16) | 48.8 (5.9) | 5.9 (1.1–11.7) | 1.5 (0.6–6.7) | 3.9 (1.7–19.6) | 1.1 (0.6–2.8)c | 0.85 (0.09–2.5) | 0.37 (0–0.93) | 1.1 (0.6–2.7) | 13.2 (2.9–26.2) | 23 (6–78)c | 1.8 (0.6–3.3) | 3.1 (0.7–6.8) |

| Group III (n = 9) | 6.24 | NA | 0.9 (0.5–2.2) | NA | 1.0 (0.4–3.0) | 0.53 (0.20–3.0) | NA | 0.04 (0.02–0.20) | 6.0 (2.1–16.4) | NA | 0.2 (0.08–0.3) | 5.6 (2.0–10.1) |

| Groups I and II (n = 16) | 6.24 | NA | 0.6 (0.2–1.4) | NA | 1.5 (1.1–3.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | NA | 0.1 (0.02–0.3) | 4.1 (1.7–5.8) | NA | 0.2 (0.07–0.5) | 4.5 (3.0–13.7) |

Data are median values (ranges), unless stated otherwise. Abbreviations: Tlag, lag time; Tabs, half-life of appearance; NA, not available; the other abbreviations are defined in the text.

n = 6.

n = 13.

The t1/2 of the appearance of DHA from ARS after i.v. administration is rapid (for group III and groups I and II, median [range] t1/2 of appearance, 6 min [0.9 to 19.4 min] and 2.5 min [0.9 to 12 min], respectively [P = 0.83]). The estimated elimination t1/2 for DHA is much longer than the t1/2 of appearance. AUC estimates for DHA after i.v. ARS administration varied 3.4-fold (group III) and 8-fold (groups I and II). Absolute AUC values were not significantly different between children receiving i.v. ARS first and second (P = 0.06). This allowed pooling of relative bioavailability estimates for all groups, as presented in Table 3.

(ii) Suppository route.

An open one-compartment model with first-order appearance and elimination with a lag time best fits the data. The median (range) correlation coefficients for pharmacokinetic models for the low-dose (10-mg/kg) and high-dose (20-mg/kg) treatment groups are 0.985 (0.933 to 0.999) and 0.968 (0.849 to 0.999), respectively. The relatively long estimate of the absorption t1/2 (Tabs) of suppositories compared with the much shorter paired elimination t1/2 estimates after i.v. administration (approximately 50% of i.r. absorption estimates) suggests that the rate of absorption determines elimination kinetics in most patients (Table 3).

There were no differences in pharmacokinetic parameters for DHA after i.r. ARS administration for patients in group II (high-dose suppositories followed by i.v. ARS) or group III (i.v. ARS followed by high-dose suppositories), suggesting that clinical improvement over 12 h and/or i.v. ARS did not affect the pharmacokinetics of i.r. DHA. Pharmacokinetic data for DHA for high-dose i.r. ARS are therefore pooled, and these data are summarized in Table 3.

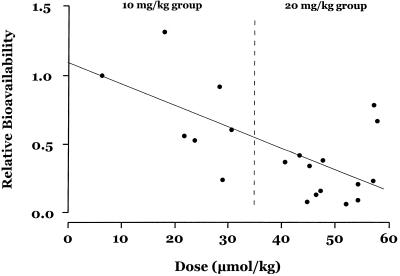

The high-dose group has a significantly reduced relative bioavailability of DHA compared with that for the low-dose group (median bioavailabilities, 23 and 58% respectively [P = 0.018]). Relative bioavailability estimates vary approximately 5.5-fold in the low-dose group (comparable to the variability in AUC for i.v. ARS in group III) and 13-fold in the high-dose groups (groups II and III). There was a negative correlation between the administered dose and relative bioavailability (r = −0.53; P = 0.019) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Relative bioavailability of DHA compared with dose of i.r. ARS.

The median Tabs is approximately 60% (64 versus 42 min) longer in the high-dose group than in the low-dose group (P = 0.023).

The Cmax of DHA after i.r. dosing is approximately 45 to 60% of that after i.v. dosing and is consistent with less rapid absorption or conversion of ARS to DHA. The median estimated V was significantly higher after i.r. ARS administration than after i.v. ARS administration (group I i.r. versus group III i.v., P = 0.013; group II and III i.r. versus group III i.v., P = 0.039) (Table 3).

For all groups, the number of suppositories influenced absorption, and the lag time was significantly shorter in patients receiving two suppository than in patients receiving one suppository (median [range] lag times, 21 min [0 to 81 min] versus 54 min [51 to 59 min] [P = 0.034]. The Tmax and Tabs were not influenced by the number of suppositories. There was no relationship between CL/f estimates for DHA after i.v. and i.r. ARS administration (all groups).

In patients receiving high-dose i.r. ARS (groups II and III), the admission lactate level positively correlated with CL (r = 0.59; P = 0.035) and V (r = 0.70; P < 0.008). The admission glucose level was also positively correlated with CL (r = 0.85; P < 0.001). The relative bioavailability of DHA positively correlated with the baseline lactate level (r = 0.7; P = 0.004). There were no other relationships between clinical, laboratory, and pharmacokinetic variables.

Pharmacodynamic analysis and follow-up.

There was no relationship between any pharmacokinetic variable and parasite clearance estimates during hospital admission (parasite clearance time, times for parasitemias to fall to 50 and 90% of the baseline levels, and parasite clearance at 12 h) (Table 2). The primary outcome measure of change in parasite count from the baseline measured 12 h after admission reflects the action of a single dose and the route of administration of ARS. Subsequent treatment regimens followed local treatment guidelines. Twenty-nine of 32 (91%) of the children attended the first follow-up (within 7 days of discharge), and one patient required sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine treatment, as chloroquine had failed to cure the patient's infection. The remainder were all well. Nineteen of 29 (59%) of the patients attended further follow-up (13 to 30 days after discharge), and 9 (47%) of these required treatment with oral quinine because of asymptomatic parasitemia or uncomplicated infection. Eight of these nine quinine-treated patients were well on subsequent follow-up; one patient did not reattend. Patients with recurrent parasitemia had a significantly lower median Cmax of DHA after i.r. ARS administration than the Cmax for those without a recurrence (2.2 versus 3.3 μmol/liter [P = 0.021]). The median (range) AUC values for DHA after i.r. ARS administration were also significantly lower in those with recurrent parasitemia than in those without recurrent parasitemia [4.6 μmol · h/kg [1.4 to 11.6 μmol · h/kg [n = 5] versus 12.8 μmol · h/kg [2.3 to 28.2 μmol · h/kg [n = 21] [P = 0.04]. There was no significant influence of i.r. dose for ARS and the risk of recurrence. For DHA after i.v. drug administration, there was no relationship between Cmax or AUC and risk of recurrence and no significant differences in the summed (i.v. and suppository) AUCs for DHA in patients who had recurrent infection and those who did not.

DISCUSSION

Intrarectal antimalarials may be lifesaving for children awaiting transfer from primary health care facilities to centers where a diagnosis of malaria can be confirmed and where definitive treatment can be implemented. Our study examined the pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and toxicity of a recently formulated, thermostable ARS suppository in children with malaria unable to take oral medication. To minimize the risk of inadequate treatment or toxicity, children with severe malaria were excluded from study by careful clinical and laboratory assessments. All children were monitored closely, and strictly defined criteria for rescue were applied if a child's clinical condition deteriorated. Data are given only for DHA because ARS elimination is very rapid (t1/2, 2 to 3 min [3, 4]) and hydrolysis produces DHA, which acts as the principal antimalarial compound (17).

i.v. ARS is one of the quickest antimalarials to clear parasitemia (13). Our comparison of i.r. ARS with i.v. ARS did not reveal pharmacodynamic differences between treatment groups. Parasitemia declined by a median of ∼80% of the baseline parasitemia by 12 h in both i.r. treatment groups as well as those receiving i.v. ARS. The crossover design of our study meant that only the 12-h time point for parasite clearance is informative for assessment of the action of a single-dose regimen (Table 2).

A small study with Gabonese children examined the efficacy of i.r. ARS (1.7 to 5.1 mg/kg administered as two 50-mg suppositories [Rectocaps] given 4 h apart). There was a median 87% fall in parasitemia 12 h after admission, despite the administration of doses that ranged from approximately one-fifth to one-half of those used for our low-dose group (10 mg/kg) (8). In 26 Thai children treated with ARS suppositories (mean [range] dose, 15 mg/kg [10 to 19 mg/kg] administered as 200-mg suppositories [Rectocaps] for a total dose of 45 mg/kg in 3 days), parasite clearance parameters (times for parasitemias to fall to 50 and 90% of the baseline levels) were prolonged compared to those following oral treatment in 26 children (6 mg/kg/day for 3 days) (21). i.v. ARS had a longer elimination t1/2 if it was given after the administration of 20-mg/kg suppositories than if it was given before the administration of suppositories. This observation cannot distinguish between a pharmacokinetic effect of i.r. ARS and an effect due to improvement in the clinical condition of the patients during the 12 h before i.v. ARS was given. If moderate malaria alters the pharmacokinetics of ARS in children (as uncomplicated malaria does in adults [17]), then this will be difficult to establish because ethical considerations preclude classical pharmacokinetic studies with convalescent-phase children. There were no adverse events attributable to either i.r. or i.v. ARS in any patient.

Pharmacokinetic data for DHA from published studies on i.v. and i.r. ARS are summarized in Table 4 for comparison with our results. Most analyses, including ours, have found that a one-compartment model with first-order appearance and elimination adequately describes the pharmacokinetic behavior of i.r. and oral ARS. Our derived pharmacokinetic parameters are also consistent with those from published studies (Table 4) (3–6, 8, 17). As the Tabs of i.r. ARS is longer than the elimination t1/2 for i.v. artesunate, the apparent elimination t1/2 for i.r. ARS appears to be prolonged as a function of its slower absorption. This effect of prolonged absorption on elimination t1/2s has been noted for benzylpenicillin as well as other drugs (19).

TABLE 4.

Published studies on DHA pharmacokinetics in patients with uncomplicated malariaa

| Source | No. of patients | Dose and route | Subjects | V (liters/kg) | Elimination t1/2 (h) | CL (liters/kg/h) | AUC (μmol · h/liter) | Tmax (h) | Cmax (μmol/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halpaap et al. (8) | 12 | 50 mg twice, ir | C | NK | NK | NK | 1.13 (0.58) | 0.63 (0.35)b | |

| Sabchareon et al. (20) | 19 | 15 mg/kg, ir | C | NK | 0.7 (0.1)b | NK | 4.1 (0.8)bc | NK | 2.38 (0.6)b |

| Newton et al. (17)d | 19 | 2 mg/kg, iv | A | 0.61 (0.5–0.72) | 0.73 (0.62–0.83) | 0.83 (0.70–0.96) | 10.6 (8.7–12.5)e | NK | |

| Batty et al. (4) | 12 | 120 mg, iv | A | 0.92 (0.78–1.06) | 0.61 (0.5–0.72) | 1.10 (0.86–1.34) | 6.5 (5.2–7.8) | 0.13 (0.12–0.2) | 7.7 (6.9–9.8) |

| Batty et al. (3) | 2 | 120 mg, iv | A | 0.76 (0.68–0.85) | 0.67 (0.62–0.72) | 0.75 (0.68–0.91) | 8.4 (7.6–9.1) | 0.15 (0.1–0.2) | 9.31 (7.1–10.9) |

| 6 |

Data are mean values (95% confidence intervals), unless indicated otherwise. Abbreviations: C, children; A, adults; NK, not known.

Data are mean ± standard error of the mean.

AUC from 0 to 12 h.

Bioassay data.

AUC from 0 to 24 h.

Ghanaian children have higher rates of DHA clearance than adults in Southeast Asia after i.v. ARS administration (Tables 3 and 4). Our elimination t1/2 estimates for DHA (∼0.8 h) after i.r. dosing are similar to those obtained by bioassay in Vietnamese children given oral ARS for moderate malaria (1 h) (6). The relative bioavailability of i.r. ARS at 20 mg/kg was a median of 23%, and for i.r. ARS at 10 mg/kg it was 58%. The higher dose of i.r. ARS used larger suppositories more often, and these may have dissolved at a slower rate compared with the rate for the smaller ones. The bioavailability of either dose of i.r. ARS is lower than published estimates of the bioavailability of oral ARS (means, between 61 and 85%) (3, 4, 17). Absorption also increases in variability when the dose of i.r. ARS is doubled. The rate of absorption of i.r. ARS is comparable to that of oral ARS and is sufficiently rapid as to be useful against malaria with a moderate level of severity.

Chinese and Vietnamese scientists have pioneered the rectal use of artemisinin derivatives, as well as artemisinin itself, for malaria of various levels of severity (9, 10, 12, 13). The earlier studies relied upon pharmacodynamic measures to guide usage because assay of ARS and its metabolites in the circulation proved to be difficult. With the recent availability of such assays, it should be possible to examine relationships between dose, the pharmacokinetic behavior of ARS (and DHA), and pharmacodynamic effects in phase III-IV studies. Smaller studies, including this one, have failed to show relationships between the pharmacokinetic behavior of ARS and acute parasite clearance kinetics. The ARS and DHA levels following i.r. therapy are well above estimates of the 50% inhibitory concentration for P. falciparum obtained in vitro (median [range] 50% inhibitory concentration, 7.4 nmol/liter [0.6 to 36.6 nmol/liter] [n = 256 isolates]) (18) and remain above these levels for many hours. The rapidity of parasite clearance kinetics in most children therefore implies that drug-dependent parasite clearance rates are likely to be maximal in all treatment groups. Our study therefore could not provide any indication of a minimum parasiticidal concentration. Drug-independent factors also influence parasite clearance kinetics and may explain the less rapid fall from the baseline parasitemia observed in some children receiving i.v. or high-dose i.r. ARS (Table 2) (21). Dosing regimens that implement the use of rectal ARS will require information from larger studies that define, with greater confidence, variability in absorption characteristics and that relate these to pharmacodynamic outcomes. To provide this information, phase III hospital-based studies (n > 100 children) have recently been completed (M. Gomes, personal communication). Phase IV trials will be implemented soon and will aim to study the efficacy of i.r. ARS in reducing mortality when it is used at the primary health care level to treat African children with clinically diagnosed malaria while they are en route to hospital.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the WHO-TDR Special Programme in Tropical Diseases and by The Wellcome Trust and forms part of a program for research in Clinical Tropical Medicine based at the Department of Infectious Diseases at St. George's Hospital Medical School. S.K. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Clinical Science, Charles Woodrow was funded by a Wellcome Trust Travel grant, Dan Agranoff was funded by an MRC Clinical Training Fellowship, and Tim Planche acknowledges support from the St. George's Hospital Special Trustees fund.

We thank Evans Kyei-Nimako and Esther Essuming and her staff for assistance with patient management, Theunis Eggelte for dipsticks, B. Baffoe-Bonnie, G. Brobby, and G. Griffin for support, and Ric Price for randomization. We also thank Peter Folb, Nick White, and Melba Gomes as well as other members of the Artesunate Task Force for valuable discussions. Kris Weerasuriya and Isabela Ribeiro were trial monitors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agbenyega T, Angus B, Bedu-Addo G, Baffoe-Bonnie B, Guyton T, Stacpoole P, Krishna S. Glucose and lactate kinetics in children with severe malaria. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1569–1576. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.4.6529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barradell L B, Fitton A. Artesunate. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of malaria. Drugs. 1995;50:714–741. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199550040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batty K T, Thu L T, Davis T M, Ilett K F, Mai T X, Hung N C, Tien N P, Powell S M, Thien H V, Binh T Q, Kim N V. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of intravenous vs oral artesunate in uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45:123–129. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batty K T, Thu L T A, Ilett K E, Tien N P, Powell S M, Hung N C, Mai T X, Chon V V, Thien H V, Binh T Q, Kim N V, Davis T M E. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of artesunate for vivax malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:823–827. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benakis A, Paris M, Loutan L, Plessas C T, Plessas S T. Pharmacokinetics of artemisinin and artesunate after oral administration in healthy volunteers. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:17–23. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bethell D B, Teja-Isavadharm P, Cao X T, Pham T T, Ta T T, Tran T N, Nguyen T T, Pham T P, Kyle D, Day N P, White N J. Pharmacokinetics of oral artesunate in children with moderately severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:195–198. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90222-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabrielsson J, Weiner D. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data analysis: concepts and applications. 2nd ed. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Pharmaceutical Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halpaap B, Ndjave M, Paris M, Benakis A, Kremsner P G. Plasma levels of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin in children with Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Gabon after administration of 50-milligram artesunate suppositories. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:365–368. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hien T T. An overview of the clinical use of artemisinin and its derivatives in the treatment of falciparum malaria in Viet Nam. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88(Suppl. 1):S7–S8. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90461-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hien T T, Arnold K, Vinh H, Cuong B M, Phu N H, Chau T T H, Ho N T M, Chuong L V, Mai N T H, Vinh N N, Trang T T M. Comparison of artemisinin suppositories with intravenous artesunate and intravenous quinine in the treatment of cerebral malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:582–583. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hien T T, Phu N H, Mai N T H, Chau T T H, Trang T T M, Loc P P, Cuong B M, Dung N T, Vinh H, Waller D J, White N J. An open randomized comparison of intravenous and intramuscular artesunate in severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992;86:584–585. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(92)90138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hien T T, Tam D, Cuc N, Arnold K. Comparative effectiveness of artemisinin suppositories and oral quinine in children with acute falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:210–211. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90024-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hien T T, White N J. Qinghaosu. Lancet. 1993;341:603–608. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90362-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee I S, Hufford C D. Metabolism of antimalarial sesquiterpene lactones. Pharmacol Ther. 1990;48:345–355. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navaratnam V, Mordi M N, Mansor S M. Simultaneous determination of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin in blood plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography for application in clinical pharmacological studies. J Chromatogr. 1997;692:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newton C W, Krishna S. Severe falciparum malaria in children: current understanding of its pathophysiology and supportive treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79:1–53. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newton P, Suputtamongkol Y, Teja-Isavadharm P, Pukrittayakamee S, Navaratnam V, Bates I, White N. Antimalarial bioavailability and disposition of artesunate in acute falciparum malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:972–977. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.4.972-977.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price R, Cassar C A, Brockman A, Duraisingh M, van Vugt M, White N J, Nosten F, Krishna S. pfmdr1 gene amplification and multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum on the northwest border of Thailand. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2943–2949. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowland M, Tozer R N. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2nd ed. Malvern, Pa: Lea & Febiger; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabchareon A, Attanath P, Chanthavanich P, Phanuaksook P, Prarinyanupharb V, Poonpanich Y, Mookmanee D, Teja-Isavadharm P, Heppner D G, Brewer T G, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T. Comparative clinical trial of artesunate suppositories and oral artesunate in combination with mefloquine in the treatment of children with acute falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:11–16. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.58.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White N J, Krishna S. Treatment of malaria: some considerations and limitations of current methods of assessment. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:767–777. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]