Abstract

Here, we report that the LynB splice variant of the Src-family kinase Lyn exerts a dominant immunosuppressive function in vivo, whereas the LynA isoform is uniquely required to restrain autoimmunity in female mice. We used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to constrain lyn splicing and expression, generating single-isoform LynA knockout (LynAKO) or LynBKO mice. Autoimmune disease in total LynKO mice is characterized by production of antinuclear antibodies, glomerulonephritis, impaired B cell development, and overabundance of activated B cells and proinflammatory myeloid cells. Expression of LynA or LynB alone uncoupled the developmental phenotype from the autoimmune disease: B cell transitional populations were restored, but myeloid cells and differentiated B cells were dysregulated. These changes were isoform-specific, sexually dimorphic, and distinct from the complete LynKO. Despite the apparent differences in disease etiology and penetrance, loss of either LynA or LynB had the potential to induce severe autoimmune disease with parallels to human systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Single-isoform Lyn knockout mice reveal sex-specific requirements for LynA and LynB kinases in preventing autoimmunity.

INTRODUCTION

The Src-family kinase (SFK) Lyn catalyzes the activation of many immune cell signaling pathways, including initiating antimicrobial responses by phosphorylating ITAMs [immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs; e.g., in B cell antigen receptor (BCR) and myeloid cell Fc gamma receptor (FcγR)] (1–6). However, Lyn can also perform inhibitory functions downstream of ITAMs and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in B and myeloid cells. To suppress ITAM signaling, Lyn phosphorylates ITIMs (immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs; e.g., in CD22 and SIRPα) and tyrosine and lipid phosphatases (e.g., SHP-1 and SHIP1) (2, 7, 8). Catalytic and adaptor functions of Lyn can suppress TLR signaling via SHIP1, the phosphatidylinositol kinase PI3K, and the transcription factor IRF5 (9–12).

In humans, hypomorphic alleles of LYN are linked to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (13, 14); in addition, lupus patients often have functional deficiencies in Lyn expression, signaling, or trafficking (15, 16). With age, Lyn knockout (LynKO) mice develop an autoimmune disorder with similarities to human SLE, including antinuclear antibody (ANA) production, glomerulonephritis, myeloproliferation, splenomegaly, B cell lymphopenia, and selective enrichment of autoreactive and inflammatory B cell and myeloid cell subsets (17–19). While Lyn functions in multiple cell types to suppress autoimmunity, it is not clear how the opposing positive and negative functions of Lyn are integrated in different populations of myeloid and B cells and signaling pathways to maintain immune homeostasis (5, 6).

Although no sex-specific differences have been reported in LynKO mice, 90% of human SLE patients are women (20). The reasons for this disparity are still a matter of discussion, with genetic and environmental factors both likely contributors. Hormone signaling appears to be involved, as SLE symptoms worsen during pregnancy (21). Immune cells express estrogen and androgen receptors, allowing them to respond directly to sex hormones. In addition, women can have higher inflammatory set points, with higher type I interferon (IFN) and antibody titers and more frequent allograft rejection (22–25). Incomplete X-chromosome inactivation in immune cells (26, 27), leading to increased protein levels of TLR7, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, and CD40L (23), may also be a factor predisposing women to SLE and other autoimmune diseases. Higher levels of TLR7 in B cells, monocytes, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) can lead to increased inflammatory signaling and production of IgD−CD27− double negative (DN2) B cells in women or aging-associated B cells (ABCs) in female mice (27–31). It is not known whether LynKO mice lack a sex-specific driver of lupus or whether the resulting disease, which can be initiated by conditional deletion of Lyn in either B cells or DCs alone (11, 32), is simply so severe as a germline knockout that it obscures any sex differences. The molecular mechanisms regulating Lyn function in a sex- and cell-specific manner are also unclear.

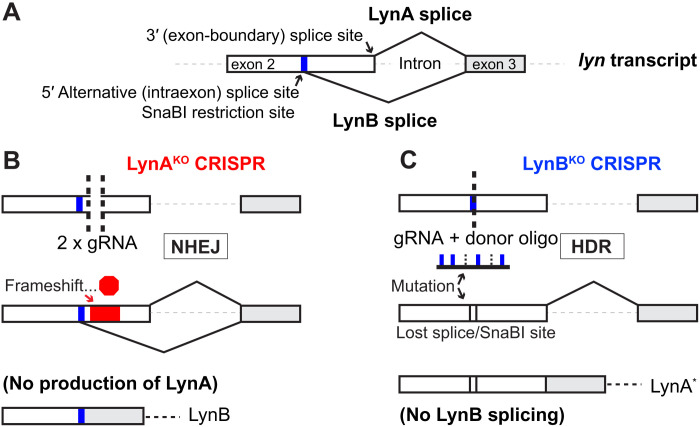

Lyn is expressed as two isoforms: LynA (56 kDa) and LynB (53 kDa). Spliced from a 5′ alternative donor site within exon 2, LynB lacks a 21–amino acid insert present in LynA (Fig. 1A and fig. S1A) (33). Using overexpression/reconstitution approaches in Lyn-deficient cells, previous studies have suggested that the roles of LynA and LynB may be distinct (34, 35). Our group has observed that selective degradation of LynA results in a signaling blockade that is not reversible by activated LynB (36, 37). Lack of isoform-specific knockout models, however, has remained a barrier to studying the discrete functions of LynA and LynB.

Fig. 1. Generation of LynAKO and LynBKO mice.

(A) Locations of LynA and LynB splice junctions in WT lyn transcript; a SnaBI restriction site is situated near the LynB splice donor in exon 2. (B) Generating LynAKO via NHEJ after double cutting within the LynA insert. (C) Generating LynBKO via HDR from a point-mutated donor oligonucleotide template.

To unmask isoform-specific functions of Lyn, we used CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing to generate single-isoform LynAKO and LynBKO mice, each with the remaining isoform expressed at a physiological level. While LynBKO mice uniformly developed a severe autoimmune disorder characterized by splenomegaly and autoantibody production, only female LynAKO mice developed severe disease. Notably, either isoform of Lyn was sufficient to support B cell development, which effectively uncoupled the developmental phenotype from the skewing and expansion of myeloid and differentiated B cell populations. We found unique, isoform-specific, and sex-specific differences in subsets of myeloid cells, B cells, and T cells in the single-isoform and total LynKO mice. Despite these differences, mice of either sex with severe splenomegaly produced autoreactive antibodies and developed lupus nephritis. These observations support a model in which LynB carries the more dominant immunosuppressive function, but LynA is uniquely required to protect against autoimmune disease in female mice.

RESULTS

Generation of LynAKO and LynBKO mice

We generated germline knockouts of LynA and LynB via CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. For the LynA knockout, we injected mouse embryos with a preformed ribonucleoprotein complex (38, 39) of Cas9 and two guide RNAs (gRNAs). This complex excised a short sequence near the (LynA-only) 3′ end of Lyn exon 2, triggering repair by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) (Fig. 1B). Shortened (double cut/deletion), SnaBI–sensitive (preserved 5′ splice donor), polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–screened candidates were sequenced and bred to homozygosity. The final LynAKO(CRISPR) allele contained a 37-nucleotide deletion, which induced a frameshift and predicted premature termination codon at position 78 in exon 4 of the 12 LynA coding exons (fig. S1B) (40, 41). Thus, the LynA splice product fit the criteria for nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) (42), with no alteration of the LynB splice site or mRNA sequence (fig. S1C).

For the LynB knockout, we used a single gRNA with a donor oligonucleotide as a template for homology-directed repair (HDR). The oligonucleotide contained a point mutation to ablate the LynB splice donor and a second silent mutation of the SnaBI restriction site for screening (Fig. 1C). In the final LynBKO(CRISPR) allele, ablation of the LynB splice donor introduced a conservative valine-to-leucine aliphatic substitution at LynA position 24 (fig. S2).

To confirm that LynAV24L was functional in LynBKO, we generated F1 (LynABhemi) mice by crossing homozygous LynAKO(CRISPR) and LynBKO(CRISPR) parents (Fig. 2A and fig. S3A). Bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) from LynABhemi mice expressed a physiological level of LynAV24L from one allele and a physiological level of LynB from the other (Fig. 2, B and C). The phenotypes of LynABhemi controls, reported throughout this paper, were indistinguishable from wild type (WT) (e.g., fig. S3B). LynA and LynAV24L were equally effective initiators of signaling in an ectopic expression system (fig. S3, C and D) (36, 43, 44) and had equal susceptibility to activation-induced degradation in BMDMs (fig. S3, E and F) (36, 37, 45–51). We therefore considered LynAV24L to be an acceptable substitute for LynA in LynBKO mice. Secondarily, these controls increase our confidence that no dominant-negative LynA truncation product was expressed in LynAKO mice.

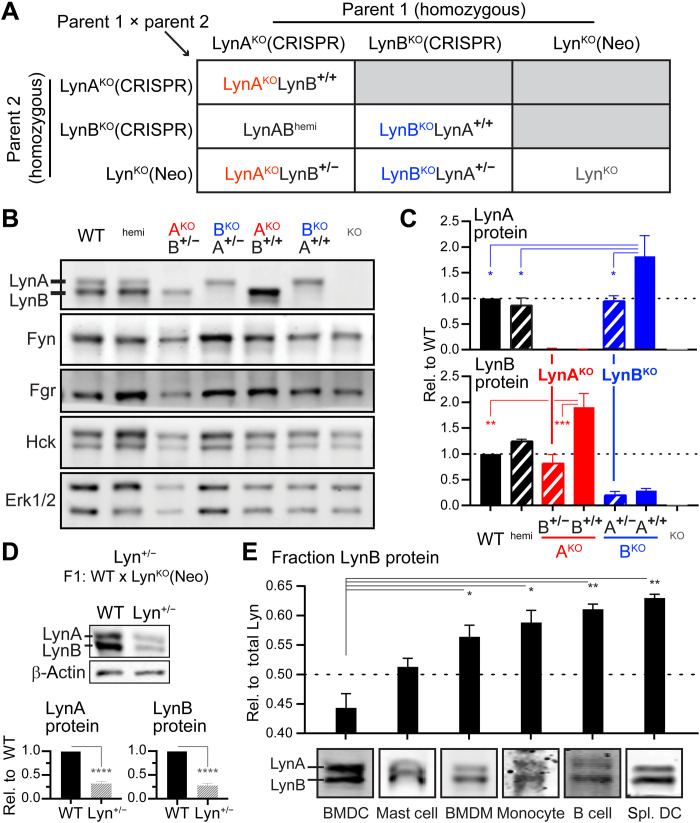

Fig. 2. SFK expression in LynAKO and LynBKO mice.

(A) Breeding scheme showing parental CRISPR and neomycin (Neo) (53) knockouts. LynAKOLynB+/+ progeny have biallelic expression of LynB, whereas LynAKOLynB+/− have monoallelic expression of LynB; allelic expression is reversed in the LynBKO series. (B) Immunoblot showing SFK expression in WT, (LynAB)hemi, (Lyn)AKO, (Lyn)BKO, and (total Lyn)KO BMDMs; Erk1/2 shows protein loading. (C) Quantification of LynA and LynB protein in BMDMs from male and female mice, corrected for total protein staining (74) and background in LynKO, reported relative to WT. Residual LynB signal in LynBKO was caused by LynA bleed-through. Error bars are SEM from at least three independent experiments (n = 3 to 5). Unless otherwise specified, significance: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.002, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05. Not annotated: In the Lyn(B or A) quantifications, [WT/LynABhemi] versus [Lyn(A or B)KO/LynKO] pairs were significantly different. Other pairs were not significant. WT and CskAS BMDMs were both used in this analysis. (D) Total Lyn protein expression in WT and Lyn+/− BMDMs, corrected as above; in this and other figures, β-actin shows protein loading. Significance: unpaired t test; error bars: SEM (n = 4). (E) Relative LynB protein content in immune cells, with representative immunoblot images for BMDCs, bone marrow–derived mast cells, BMDMs, peripheral blood monocytes, splenic B cells, and splenic DCs (Spl. DC). Error bars: SEM (n = 3 to 13).

Knockout of LynA and LynB, respectively, was confirmed in BMDMs from homozygous LynAKOLynB+/+ and LynBKOLynA+/+ mice (Fig. 2, A and B). Expression levels of other SFKs (Fyn, Fgr, Hck, and Src) in BMDMs were unaltered (Fig. 2B and fig. S4A). LynA expression was increased twofold in homozygous LynBKOLynA+/+ BMDMs relative to WT; we attributed this increase to LynA being the only remaining option for transcript splicing.

As the LynA CRISPR deletion was expected to trigger NMD of mature mRNA after LynA and LynB splicing, we expected to find LynB expressed at roughly physiological levels in LynAKO cells. To our surprise, expression of LynB was up regulated twofold relative to WT in homozygous LynAKOLynB+/+ BMDMs (Fig. 2C). To assess whether LynB up-regulation was a feedback process triggered by cumulative loss of Lyn (A + B) or an isoform-specific regulatory effect, we generated F1 (Lyn+/−) progeny of WT and total LynKO(Neo) mice (52, 53). Lyn+/− BMDMs, in which LynA and LynB are coexpressed from a single allele, had 75% reduced expression of both LynA and LynB (Fig. 2D), suggesting that maintaining a balance of LynA and LynB or a change in splicing is the dominant driver of the feedback regulation in LynAKOLynB+/+ macrophages.

We also assessed the relative expression levels of LynA and LynB in representative immune cells: DCs, macrophages, monocytes, mast cells, and B cells (Fig. 2E). Preferential expression of LynA and LynB varied by cell type, suggesting some degree of cell-specific regulation at the splicing or protein level. Splenic DCs and B cells, for example, expressed the most LynB (63 and 61% of total Lyn), whereas bone marrow–derived DCs (BMDCs) expressed the least (44% of total Lyn). Although these differences were subtle, they were consistent within each cell type and lend context to cell-specific phenotypes of LynAKO and LynBKO mice.

To achieve physiological expression of the remaining isoform in the LynA and LynB knockouts, we pivoted to a monoallelic expression strategy, using F1 progeny from homozygous LynKO(Neo) × homozygous LynAKO(CRISPR) or LynBKO(CRISPR) parents (Fig. 2A). BMDMs from LynAKOLynB+/− and LynBKOLynA+/− mice expressed the remaining Lyn isoform at levels comparable to WT (Fig. 2, B and C). Single-isoform expression did not systematically affect the levels of other SFKs in BMDMs and BMDCs (Fig. 2B, fig. S4, A and B) and did not impair IFN-γ–dependent up-regulation of Lyn expression (fig. S5) (37)). LynAKOLynB+/− and LynBKOLynA+/− mice are hereafter referred to as “LynAKO” and “LynBKO,” respectively (Fig. 2C).

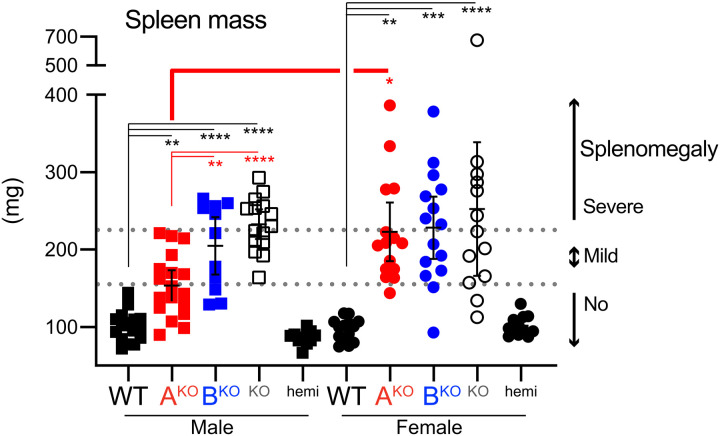

Severe splenomegaly in aging LynBKO mice and female LynAKO mice

Like LynKO mice (4, 17, 18), male and female LynBKO mice developed mild-to-severe splenomegaly between 5 and 8.5 months of age (Fig. 3 and fig. S6A). In contrast, only female LynAKO mice developed severe splenomegaly. The effects of LynA and LynB knockout were not additive, with the most severely affected single-isoform knockouts comparable in spleen mass to total LynKO. These data suggest that LynB performs the dominant regulatory function for both sexes, while LynA is uniquely required for maintaining normal cell numbers in the spleens of female mice. This observation did not extend to body mass, another typical indicator of disease, in part due to high variability in WT female mice (fig. S6B). Moreover, as Lyn and Lyn-expressing myeloid cells regulate adipose, bone, and other tissues (54, 55), interpretation of differences in body mass is not straightforward.

Fig. 3. LynBKO mice and female LynAKO mice develop severe splenomegaly.

Spleen masses from four to six different cohorts of male mice aged 8.5 ± 0.4 months and female mice aged 8.4 ± 0.2 months; error bars: 95% CIs. In this and other figures, in addition to the annotated comparisons (asterisks colored by genotype), there were no significant differences between LynABhemi and WT. Dotted lines reflect phenotypic scoring: no splenomegaly (spleen <155 mg), mild splenomegaly (155 to 225 mg), or severe splenomegaly (>225 mg), referenced in later figures.

Unique myeloid cell profiles in LynAKO and LynBKO mice

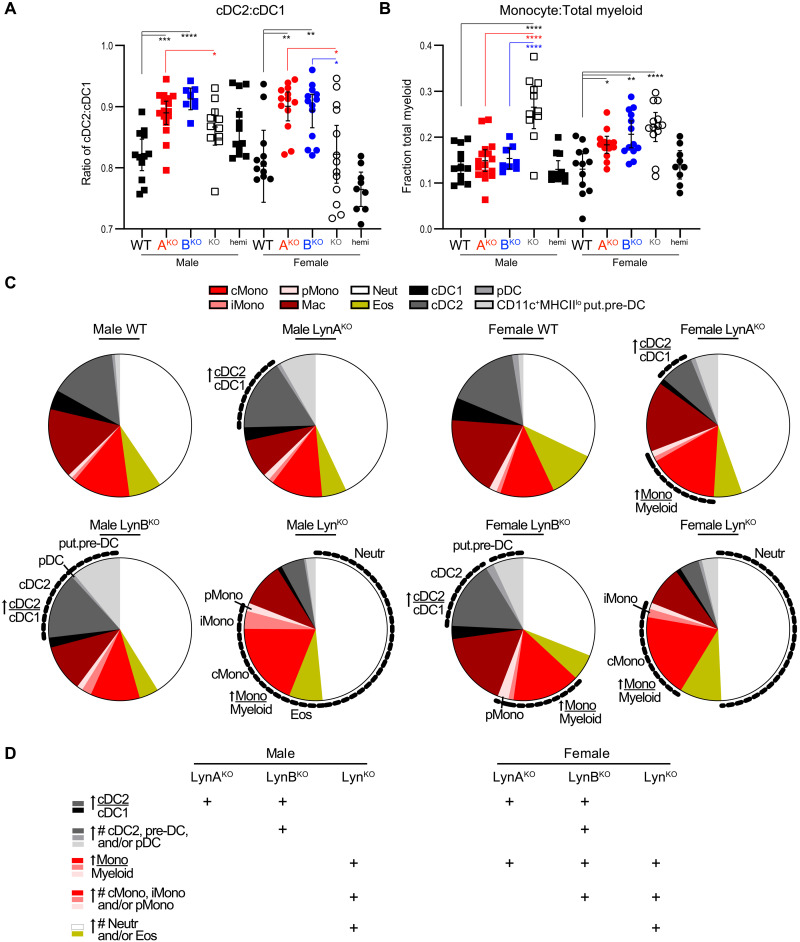

Because splenomegaly in total LynKO mice stems from myeloproliferation, especially in monocyte and granulocyte (neutrophil + eosinophil) populations (11, 32, 56), we used flow cytometry to quantify splenic myeloid cells (fig. S7). With the exception of an early increase in patrolling monocytes in total LynKO mice (57), myeloid cell expansion developed between 5 months (fig. S8) and 8.5 months of age.

Spleens from aged LynKO, LynBKO, and female LynAKO mice had distinctive myeloid cell imbalances. Most notably, the cDC2 (conventional type 2 DC) pool was increased in LynAKO and LynBKO mice but not in total LynKO mice (Fig. 4A and fig. S9). Only spleens from female single-isoform mice had a secondary expansion of monocytes within the myeloid cell pool (Fig. 4B and fig. S10). Neither LynAKO nor LynBKO spleens had the granulocyte expansion characteristic of the total LynKO (Fig. 4C and fig. S11) (11, 32, 56).

Fig. 4. Isoform- and sex-specific differences in splenic monocyte and DC composition of LynAKO and LynBKO mice.

Spleen cell suspensions from 8.5-month-old mice were stained for myeloid cell markers and analyzed by flow cytometry. Counting beads were used to calculate the total number of cells per spleen, from which the fractional content of each cell type was calculated. Populations: Classical monocyte (cMono: CD64+MerTK−Ly6Chi), intermediate monocyte (iMono: Ly6Cintermediate), patrolling monocyte (pMono: Ly6Clo), macrophage (Mac: CD64+MerTK+), conventional type 1 DC (cDC1: CD64−CD11chiMHCIIhiCD11bloXCR1hi), conventional type 2 DC (cDC2: CD11bhiXCR1lo), CD11c+SiglecF−MHCIIlo putative pre-DC [put.pre-DC (58–60)], plasmacytoid DC (pDC: CD11cloLy6ChiPDCA1hi), eosinophil (Eos: Ly6GmedSiglec-F+SSChi), and neutrophil (Neut: Ly6Ghi). (A and B) Fractional content of splenic monocyte (A) and cDC2 (B) populations. Error bars: 95% CI. Asterisks are statistical comparisons colored by genotype; no significant differences between LynABhemi and WT populations. Data pooled from four to six separate cohort analyses. Gating is shown in fig. S7, and cell counts and statistics are shown in figs. S9 to S11. (C) Myeloid cell populations in Lyn knockout mice. Labels and dotted lines highlight total splenic cell populations (or fractional populations, where indicated) that were increased significantly relative to same-sex WT comparators. LynABhemi analyses are included in the supplement. (D) Summary of myeloid cell imbalances in Lyn knockout mice.

The monocyte expansion phenotype in LynAKO and LynBKO mice was milder and more sexually dimorphic than in total LynKO mice. Phenotypes in the female single-isoform knockouts varied in severity from mild (elevated total monocyte fraction) in female LynAKO spleens to moderate (elevated patrolling monocyte numbers) in female LynBKO spleens to severe (elevated classical, intermediate, and/or patrolling monocyte numbers) in male and female LynKO spleens.

The DC expansion phenotype was present in male and female LynAKO and LynBKO mice. cDC1 numbers were not affected in any of the Lyn knockouts, but cDC2 and other DC populations were increased in LynAKO and LynBKO mice. Phenotypes varied in severity from mild (elevated cDC2:cDC1 ratio) in LynAKO spleens to severe (elevated cDC2 numbers) in LynBKO spleens.

A population of CD64−CD11c+SiglecF− cells was also increased in LynBKO but not total LynKO spleens. On the basis of their low expression of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII) and lack of B cell markers, we tentatively classified these cells as pre-DCs (fig. S7) (58–60). In all the Lyn knockouts, this putative pre-DC population up-regulated CD80/86, which was absent or expressed at low levels in WT pre-DCs (fig. S7, inset) (60).

Together, the unique expansion of DCs in the single-isoform knockouts and additional monocyte expansion in the female mice created a continuum of myeloid dysregulation, ranging from the mildest phenotype for male LynAKO spleens to more severe phenotypes in LynBKO and female LynAKO spleens (Fig. 4D). Severe phenotypes in male and female mice indicate a dominant role for LynB in maintaining splenic myeloid populations. Loss of both isoforms in the total Lyn knockout restored a WT-like balance of DCs but caused the most severe monocyte and granulocyte expansion.

Myeloid cells from LynKO mice are more proinflammatory and activated than cells from single-isoform knockouts

Most myeloid cell populations in spleens from LynKO mice expressed higher levels of proinflammatory and activation-associated markers than cells from either of the single-isoform knockouts, suggesting a more severe inflammatory phenotype. Female LynAKO and LynBKO mice, however, had increased expression of proinflammatory markers compared to WT. Splenic macrophages from female LynAKO and LynBKO mice had some elevation of CD80/86 and a significant increase in CD11c, comparable to LynKO (Fig. 5A). Male LynAKO and male LynBKO macrophages were not significantly different from WT. This sex-specific effect was absent in the total LynKO. For other markers that were responsive to Lyn expression, including CD11b expression on neutrophils, MHCII on cDC2s, and CD80/86 on pDCs, LynKO cells consistently had the most severe phenotype (Fig. 5B and fig. S12).

Fig. 5. Differential polarization of myeloid cells and BAFF production from male and female LynAKO and LynBKO mice.

Spleen cell suspensions from 8.5-month-old male and female mice were stained for markers of myeloid polarization and analyzed by flow cytometry. Geometric mean fluorescence intensities (gMFIs) reported relative to the average WT value for each cell type and marker within each of four to six experiment days. Statistical annotations and error bars as described in Fig. 4. (A) Expression of proinflammatory polarization markers by MerTK+ macrophages. (B) Expression of neutrophil and DC activation/polarization markers. (C) Serum from 8.5-month-old male and female mice was assayed for BAFF using ELISA; error bars: SEM.

In alignment with their preferential expression of hyperstimulatory markers on cDC2 and pDC populations (32, 61) and CD11bhi/expanded neutrophils (62, 63), only total LynKO mice had significantly elevated serum levels of the proinflammatory cytokine BAFF (Fig. 5C). The trend toward milder elevation of serum BAFF in LynAKO and LynBKO mice also paralleled the trend toward more modest expression levels of MHCII and CD80/86 on cDC2 and pDC subsets.

From these data, we conclude that loss of both Lyn isoforms causes more severe inflammatory dysregulation of myeloid cells than loss of either isoform alone. Notably, costimulatory markers are also most profoundly dysregulated on DCs in the total LynKO, despite the greater effect of isoform-specific LynA or LynB knockout on DC numbers. This could also suggest that granulocytes, not DCs, are the major drivers of BAFF production (64).

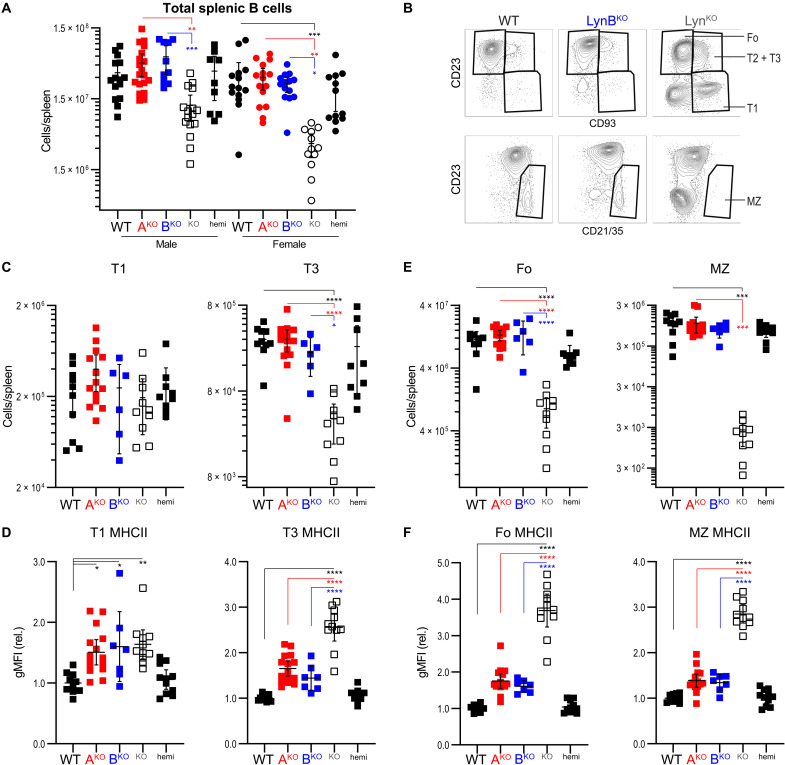

LynA or LynB expression is sufficient to restore B cell development

Reduced B cell numbers, attributed to cell death during progression through transitional stages 1 to 3 of development (56), are a hallmark of immune dysregulation in LynKO mice (17). Expression of either LynA or LynB, however, was sufficient to rescue B cell numbers to near-WT levels in male and female mice (Fig. 6A). Spleens from 8.5-month-old LynAKO and LynBKO mice had significantly more T2 and T3 B cells than those from LynKO mice (Fig. 6, B and C, and fig. S13), which appeared relatively enriched in T1 cells due to cell loss at later stages (fig. S14) (65, 66). LynAKO and LynBKO transitional cells generally had intermediate levels of MHCII expression, between WT and the significantly elevated levels in total LynKO cells (Fig. 6D) (32).

Fig. 6. B cell development is rescued by expression of LynA or LynB.

Spleen cell suspensions from 8.5-month-old male and female mice were stained for markers of B cell development and analyzed by flow cytometry on four to six cohort/experiment days. (A) Total spleen B cell numbers; error bars: 95% CI. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots showing gates for follicular B cells (Fo: CD93−CD23+), T1 B cells (CD93+CD23−), T2/T3 B cells (CD93+CD23+), and marginal zone B cells (MZ: CD23−CD21/35+). (C) Total numbers of B cell transitional populations T1 and IgMlo T3 per spleen. (D) Surface MHCII expression on T1 and T3 B cells relative to WT within each experiment. (E) Total numbers of Fo and MZ B cells per spleen. (F) Surface MHCII expression on Fo and MZ B cells.

LynAKO and LynBKO spleens also contained more follicular (Fo) and marginal zone (MZ) B cells than those of total LynKO (Fig. 6E and fig. S14), and these cells had levels of surface MHCII comparable to WT (Fig. 6F) (32, 67, 68). LynA or LynB expression also restored normal immunoglobulin M (IgM) expression within the Fo B cell population (fig. S14).

Together, either LynA or LynB expression appears sufficient to restore B cell development, supporting production of MZ and Fo B cell populations in WT-like numbers. However, these populations do not experience any further increase in proportion to splenomegaly. Increased surface MHCII could reflect elevated BCR signaling in early transitional populations of LynAKO and LynBKO B cells (69), but differentiated MZ and Fo B cell populations do not appear to be hyperresponsive. Thus, deletion of either isoform of Lyn effectively uncouples the B cell development defect from the other myeloid and B cell drivers of autoimmunity observed in total LynKO mice.

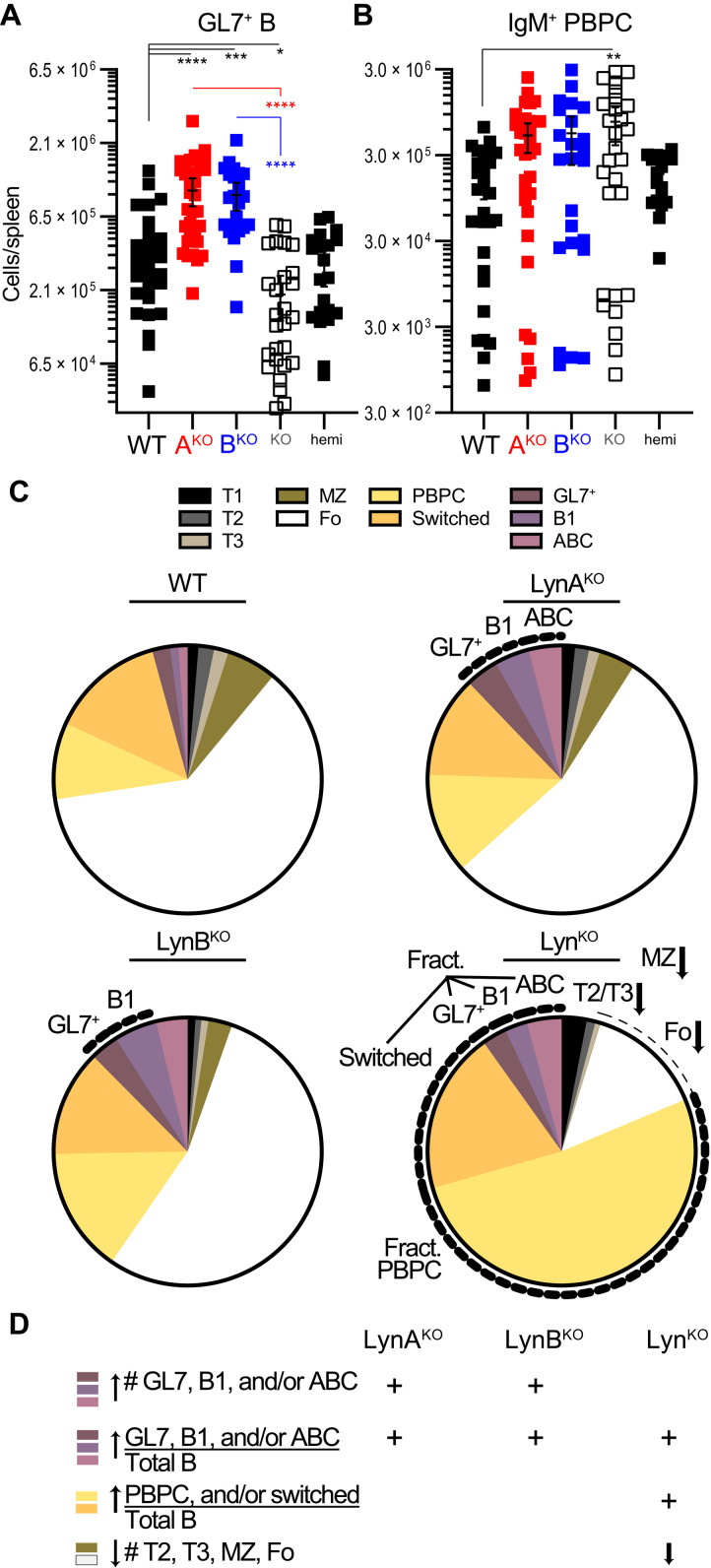

Enrichment of differentiated B cells in spleens from single-isoform Lyn knockout mice

Activated and autoreactive populations of differentiated B cells are enriched in total LynKO mice (56, 70), and we performed flow cytometry to quantify these populations in the single-isoform knockouts (fig. S13). Expansion of differentiated B cell pools in the Lyn knockouts occurred between 5 months (fig. S15) and 8.5 months of age. In the single-isoform knockouts but not the total LynKO, GL7+ germinal center (GC) or activated B cells, B1 cells, and a CD19hiCD21/35− population likely comprising ABCs increased roughly in proportion to spleen size (Fig. 7A and fig. S16A). In contrast, plasmablasts and plasma cells, including the IgM+ unswitched population reported to drive the plasma cell expansion in LynKO spleens (fig. S13, inset) (71), were not significantly more numerous in LynAKO or LynBKO than in LynKO (Fig. 7B). Immunoglobulin class-switched B cells, like Fo and MZ B cells, were not significantly expanded in the single-isoform knockouts relative to WT (fig. S16A). Overall, these expansion profiles resulted in a relative enrichment of GL7+ cells, B1 cells, and ABCs within the total B cell population in LynAKO, LynBKO, and LynKO. Only LynKO spleens, however, were significantly enriched in IgM+ plasmablasts and plasma cells and switched B cells (fig. S16B) (32, 52).

Fig. 7. Unique expansion of activated and autoimmunity-associated B cell subsets in LynAKO and LynBKO mice.

Spleen cell suspensions from 8.5-month-old male and female mice were stained for B cell markers and analyzed by flow cytometry. Populations of differentiated B cells: GL7+ GC and activated B cells (GL7+: B220+GL7hi), B1 B cells (B220+CD11bhi), ABCs (CD19hiCD21/35−), plasma cells and plasmablasts (PBPC: CD138hiIgH+Lhi), and switched B cells (IgM−IgD−). (A) Total splenic numbers of GL7+ B cells. (B) Total splenic numbers of IgM+ (unswitched) plasma cells and plasmablasts. (C) Fractional content of each B cell subset within the total B cell population; the PBPC pool includes IgM+ and IgM− cells. Labels and dotted lines highlight total splenic cell populations (or fractional populations, where indicated) that differ significantly from WT comparators. Gating is shown in fig. S13, and raw cell counts, statistics, and LynABhemi data are shown in Fig. 6 and figs. S14 and S16. No significant differences between LynABhemi and WT. Data pooled from four to six separate cohort analyses. (D) Summary of Lyn knockout splenic B cell composition.

GL7+ B cells were elevated in both male and female LynAKO mice, although females trended toward a more severe phenotype (fig. S17). In total LynKO mice, the increased fractional content of activated B cell subsets was largely attributable to the profound loss of Fo and MZ B cells (Fig. 7C). Overall, GL7+ B cells, B1 B cells, and ABCs increased 5- to 10-fold, roughly in proportion to spleen mass in LynAKO and LynBKO mice, whereas plasma and switched B cells failed to expand similarly (Fig. 7D).

Analysis of T cell subsets, which lack Lyn expression but respond to changes in myeloid and B cell activation, revealed additional differences in the single-isoform knockout mice (fig. S18). Although CD4+ and CD8+ populations of T cells were expanded in LynAKO and LynBKO spleens relative to total LynKO, natural killer (NK) cells and most T cell subsets had few significant differences (fig. S19).

In summary, despite supporting relatively normal B cell development and (cell extrinsically) T cell development, expression of either LynA or LynB alone was not sufficient to limit the production of activated and autoimmunity-driving B cells. This unique constellation of lymphocyte effects in LynAKO and LynBKO mice effectively uncoupled the B cell developmental phenotype from dysregulation of mature and further differentiated subsets.

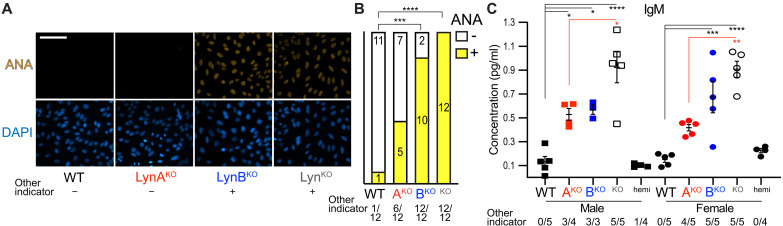

LynAKO and LynBKO mice with severe splenomegaly develop autoimmune disease

Total LynKO mice develop renal inflammation triggered by ANA and complement deposition. Kidneys from LynAKO and LynBKO mice with splenomegaly also had immune cell infiltration, evidence of glomerular and tubular inflammation (Fig. 8, A and B), deposition of IgG and complement (C3) (Fig. 8, C and D), and fibrosis (Fig. 8, E and F). The levels of renal IgG, C3, and trichrome staining were comparable in all the Lyn knockout genotypes, coinciding roughly with the splenomegaly profile. This suggests that loss of either LynA or LynB is sufficient to drive autoimmunity in mice with severely dysregulated myeloid and B cell populations, mostly LynBKO mice and female LynAKO mice. This also indicates that the blockade in B cell development in total LynKO mice is not a necessary precursor to the later dysregulation of differentiated B cells that drives autoimmunity.

Fig. 8. LynAKO and LynBKO mice with splenomegaly or low body mass develop autoimmune disease.

Mice (8.5 months old) were tested for indicators of autoimmunity and lupus nephritis. (A to D) Kidney and spleen sections and epifluorescence images were obtained from female and male mice with varying degrees of splenomegaly and body mass. (A) Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained kidney sections were deidentified and scored for glomerulonephritis; scale bar, 200 μm. Boxed regions are enlarged in the bottom row. Occurrence of splenomegaly or low body mass in the same individual (+ yes, − no), referenced after unblinding as defined in Fig. 3. Other indicators of disease are similar in all image panels. (B) Frequency of no (−), mild, or severe (Sev.) glomerulonephritis in clinical scoring; numbers reflect scores from sections prepared from individual mice; corresponding frequencies of splenomegaly and low body mass are indicated. Analysis pool: WT 5 M + 2 F, LynAKO 4 M + 3 F, LynBKO 2 M + 5 F, LynKO 5 M + 1 F, LynABhemi 1 M + 5 F. (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy images showing nuclei (DAPI), IgG deposition (Texas Red), and C3 deposition (FITC), n = 3; scale bar, 100 μm. Analysis pool for (C) to (F): WT 1 M + 2 F, LynAKO 3 F, LynBKO 3 F, LynKO 3 M, and LynABhemi 1 M + 2 F. (D) Quantification of IgG and C3 staining, using Imaris software; error bars, SEM. Corresponding frequencies of splenomegaly or low body mass are indicated; the same individuals were used for all other quantifications in this figure. (E) Masson’s trichrome (collagen, fibrin, and erythrocyte) staining of kidney; scale bar, 500 μm. (F) Quantification of trichrome staining in kidney and spleen. NIH ImageJ software was used to deconvolute and perform region-of-interest analysis; error bars, SEM.

ANA production (Fig. 9A) was assayed using sera from LynAKO and LynBKO mice. As with C3/IgG deposition in the kidney, the frequency of serum ANA positivity mirrored the pattern of splenomegaly within each genotype (Fig. 9B). In a mixed-sex analysis, LynBKO sera were primarily ANA positive, whereas LynAKO sera were more heterogeneous.

Fig. 9. LynAKO and LynBKO mice with splenomegaly or low body mass produce ANA and have elevated levels of serum IgM.

Serum was collected from 8.5-month-old male and female mice and assayed for antibody production. (A) Serum ANA detection via FITC staining of Hep-2 cells. Occurrence of splenomegaly or low body mass in the same individual is indicated (+ yes, − no). (B) Frequency of ANA negativity (−) and positivity (+). Occurrence of splenomegaly or low body mass in the same individual (+ yes, − no) as defined in Fig. 3. Significance for raw contingency data was assessed via two-sided Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Analysis pool: WT 4 M + 8 F, LynAKO 6 M + 6 F, LynBKO 4 M + 8 F, and LynKO 6 M + 6 F. (C) ELISA-derived IgM levels and associated splenomegaly or low body mass; error bars, SEM.

IgM levels were highest in sera from total LynKO mice, roughly doubling the intermediate phenotypes of the single-isoform knockouts (Fig. 9C) and mirroring the pattern of BAFF production and the expansion of IgM+ plasmablasts and plasma cells. Nevertheless, IgM levels in LynAKO and LynBKO sera were still elevated relative to WT, with loss of both Lyn isoforms trending toward an additive effect.

Last, we performed immunofluorescence microscopy on frozen spleen sections from 8.5-month-old mice with varying degrees of splenomegaly, using protein markers expressed by B cells (B220), GC/activated B cells (GL7), myeloid cells (CD11b), and T cells [T cell receptor β (TCRβ)] (Fig. 10A and figs. S20 and S21). Disruption of spleen architecture agreed with other indicators of disease, including splenomegaly. Focusing on lymphoid follicle organization (72) via immunofluorescence (Fig. 10B) or hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (Fig. 10C) revealed a series of intermediate phenotypes: WT and LynAKO mice with no or mild disease had well-formed B cell follicles, GCs, and T cell zones. LynBKO and LynKO mice with moderate-to-severe disease displayed follicular effacement with diffuse GCs and follicles. Together, these data suggest that severe disease is accompanied by disruptions in spleen architecture.

Fig. 10. Splenomegaly in male LynAKO and LynBKO mice corresponds with disruptions in spleen architecture.

(A) Spleen sections from 8.5-month-old male WT and Lyn knockout mice were imaged via immunofluorescence microscopy. Co-occurrence of either splenomegaly or low body mass (defined in Fig. 3) is indicated (+/−). Nuclei (DAPI), B220+ B cells (FITC), GL7+ GC or activated B cells [Alexa Fluor (AF) 555], CD11b+ myeloid cells (AF594), and TCRβ+ T cells (AF647) are shown; scale bar, 500 μm. (B) Fourfold increased magnification showing the architecture of a representative B cell follicle, GC, and T cell zone; scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Spleen sections visualized by H&E staining; scale bar, 500 μm. Images are representative of n = 3 mice.

DISCUSSION

Dissecting the contributions of the two Lyn isoforms has been stymied by a lack of experimental tools. LynB has no unique sequence, making the development of LynB-specific antibodies and RNA silencing reagents infeasible. In addition, LynB is produced from an intra-exon splice site, rendering traditional knockout and recombination/excision approaches intractable. We pioneered two CRISPR-Cas9 strategies to create splice-fixed LynB-only or LynA-only mouse strains: For LynAKO, we engineered a deletion and frameshift in the unique LynA insert, and for LynBKO, we ablated the LynB splice donor site. These new models can be used as hemizygotes or homozygotes for physiological or supraphysiological expression of the remaining isoform. We have found that LynB has the dominant regulatory role in mice of both sexes, but that LynA expression is uniquely required to prevent autoimmunity in female mice. Our data suggest that myeloid cells and B cells have different requirements for LynA and LynB expression, and the two isoforms are differentially required for development, proliferation, and reactivity. Last, we report that the relative expression levels of LynA and LynB are controlled by feedback regulation and maintained in a cell-specific manner.

We do not yet know why female mice are more reliant on LynA expression for immune homeostasis. It is possible that an added level of immune restraint is necessary simply because females are generally more prone to inflammation and thus easier to propel toward autoimmunity. It is also possible that LynA, and perhaps also LynB, has a direct function in hormone signaling, TLR7 signaling, or other sexually dimorphic signaling pathways. In our colony, female LynAKO mice (and by some criteria female LynBKO mice) had greater proinflammatory polarization of macrophages and with GL7+ B cells expanding proportionally with increased spleen size. When LynAKO mice did develop disease, the accompanying splenomegaly and glomerulonephritis were comparable to LynBKO and LynKO phenotypes, suggesting that the degree of disease could not be explained simply by the relative loss of Lyn expression in each genotype. Future studies will investigate dose- and pathway-specific mechanisms underlying these differences.

More generally, splenocyte expansion in the single-isoform knockouts was dominated by parallel increases in differentiated GL7+ B cell, B1, and ABC populations and by some DC subsets; monocyte numbers were additionally expanded in female LynAKO and LynBKO mice. In contrast, splenomegaly in both male and female LynKO mice was predominantly driven by granulocyte and monocyte expansion. With the exception of IgM+ plasmablasts/plasma cells, imbalances in B cell populations generally owed more to a paucity of MZ and Fo B cells than to proliferation of autoreactive subsets. These data suggest that expression of either LynA or LynB is sufficient to restore B cell development and promote increases in GL7+ and other B cell populations in parallel with myeloid cell expansion. Expression of either LynA or LynB is only partially able to rescue the bias toward IgM-producing plasma cells seen in LynKO mice. This differential requirement for Lyn expression in developing and differentiated cell subsets could stem from differential functions of LynA and LynB in the more mature cell types or the greater reliance on catalytic BCR signaling function during B cell development versus more stoichiometric adaptor functions in differentiated B and myeloid cells.

Clear phenotypic differences between Lyn+/− (52), LynAKO, and LynBKO mice could also support a model for some distinct functions of LynA and LynB, but with caveats. Although these comparison studies were performed on the same C57BL/6 strain background, colony-to-colony variation could influence disease kinetics and severity. In addition, we cannot make absolute comparisons of LynA and LynB protein concentrations across genotypes in vivo. Total expression of Lyn (A + B) is regulated by cell type and inflammatory environment (36, 37), and we have found subtle but consistent differences in the LynA:LynB ratio in different cell types. Nevertheless, from BMDMs, we estimate that LynAKO mice lose 45% of total Lyn, LynBKO mice lose 55%, and Lyn+/− mice lose 75%. Despite a more severe presumed Lyn deficiency, Lyn+/− mice were reported to develop less severe glomerulonephritis and less severe MZ/T2 B cell deficits (17, 52, 67) than observed in our single-isoform knockout mice. It could be that loss of a single Lyn isoform is more devastating than a balanced 75% depletion of LynA and LynB, and this should be the subject of future studies. In addition, the loss of either LynA or LynB alone produces an enrichment of DCs not found in the total knockout, suggesting that balanced expression of both isoforms is required for homeostatic control of DC populations.

LynB generally appears to be the dominant immunosuppressive isoform, with LynB deletion causing severe autoimmune disease in male and female mice. For some indicators (splenomegaly, glomerular IgG and C3 deposition, and kidney fibrosis), LynBKO and total LynKO mice developed equally severe phenotypes. In other cases (serum IgM and BAFF, glomerular immune infiltration, myeloid cell polarization, and monocyte/granulocyte expansion), LynBKO mice had less severe phenotypes than total LynKO mice, suggesting an additive effect with LynA. LynA and LynB seemed equally capable of promoting B cell development, regulating myeloid cell polarization and restraining myeloid-driven inflammation. Given the increased number of activated/inflammatory B cell types in LynAKO and LynBKO mice, future studies will be aimed at determining whether the single-isoform knockouts have a more B cell–initiated than myeloid cell–initiated form of autoimmune disease. Our data suggest that LynAKO and LynBKO manifestations of autoimmune disease are mechanistically distinct, given their peculiar myeloid cell expansion profiles and apparent restoration of BCR-dependent development.

Last, the up regulation of LynA protein in the homozygous LynBKO could be evidence of a feedback mechanism sensing LynA:LynB balance in cells. This is not a dose sensor for total Lyn, as Lyn+/− cells have no compensatory changes in expression. Lyn-specific feedback, independent of other SFKs, would reinforce the unique importance of balancing activating and inhibitory functions of Lyn. Our observation of cell type–specific LynA:LynB ratios further supports the idea that LynA and LynB levels are sensed and regulated. This process could be mediated by splicing factors, as in epithelial and cancer cells (35), or, as in mast cells and macrophages, by regulating the expression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase c-Cbl, which preferentially targets LynA for degradation (36, 37). Future studies will focus on these different contributions.

In summary, we have generated two new models of SLE, in which myeloid cell dysregulation and accumulation of activated B cells are offset by relatively normal B cell development and myeloid cell polarization. Selective expression of LynA or LynB is cell-specific and reveals a sexual dimorphism in the requirement for LynA expression to prevent autoimmune disease in female mice. As no sex-specific effects have been reported in LynKO mice, the more subtle and female-specific LynAKO disease is an opportunity to explore sexual dimorphism and cell-specific mechanisms of lupus progression. Definition of overlapping versus isoform-specific regulatory modes will inspire new ways of manipulating these signaling processes to restore immune balance in patients with SLE and other autoimmune diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse strains and housing

All animal use complied with University of Minnesota/American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and National Institutes of Health (NIH) policy, under Animal Welfare Assurance number A3456-01 and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol no. 1910-37487A. Animals were housed in a specific pathogen–free facility under the supervision of a licensed doctor of veterinary medicine and supporting veterinary staff. Breeding and experimental animals were genotyped via real-time PCR (Transnetyx Inc., Memphis, TN) and secondarily (where possible) by immunoblotting. All mice, including LynKO (53) and CskAS, were maintained on a C57BL/6 background and bred in house. CskAS mice are hemizygous for the CskAS bacterial artificial chromosome transgene on a CskKO background (37, 51). Lyn+/− mice are hemizygous for total Lyn expression (52).

Generation of LynAKO and LynBKO mice

CRISPR gRNAs were designed using CRISPOR.org (73) and purchased from IDT (Newark, NJ), and cutting efficiency was validated in NIH/3T3 cells. The LynAKO(CRISPR) allele was generated using two gRNAs to induce double-strand breaks, effectively deleting 77–base pair (bp) bounding portions of the unique LynA insert in mouse lyn exon 2 (5′-GAUCUCUCACAUAAAUAGUU-3′) and the following intron 2 (5′-CCAUGCUCCGAUCCUACUGU-3′). The LynBKO(CRISPR) allele was generated using one gRNA (5′-GUUCGGUCAGUAUUACGUAC-3′) to cut near the LynB splice site in exon 2. A donor oligonucleotide (5′-AAAAGGAAAGACAATCTCAATGACGATGAAGTAGATTCGAAGACTCAACCAcTgCGTAATACTGACCCAACTATTTATGTGAGAGATCCAACGTCCAATAAACAGCAAAGGCCAGTAAG-3′) was supplied to template two single-nucleotide substitutions for HDR (indicated by the lowercase letters in the above sequence) that ablated the LynB splice site and an BI restriction site.

To generate the CRISPR alleles, stud C57BL/6J male mice and 3-week-old C57BL/6J female mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME); females were housed 3 to 4 days before hormone injection. Superovulation was induced via intraperitoneal injection of 5 IU of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin, followed 48 hours later by 5 IU of human chorionic gonadotropin (National Hormone & Peptide Program, Torrance, CA). Females were then immediately mated with the stud males, and zygotes were harvested the following day and injected with Cas9 protein (30 ng/μl) and 3.5 ng/μl of each gRNA. For LynBKO, the injection mixture also included single-stranded, 120-bp donor oligonucleotide (7 ng/μl) (39). Embryos were then implanted into female CD-1 mice (38 to 49 days old) purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA).

DNA was isolated from the toes of candidate pups using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and subjected to intermediate Topo cloning (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to insert PCR products into a plasmid for PCR amplification/restriction digest and sequencing (GENEWIZ, South Plainfield, NJ). A 500-bp segment, encompassing the LynB splice site and the LynA unique insert, was amplified from each candidate using the primers 5′-ACAACCGAGATGTCCTGCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGCCAGATTATCCCTAAAATCTCTACA-3′ (reverse). SnaBI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) cleavage of WT product (recognition site TAC/GTA) generates two 250-bp fragments. In LynAKO, a Cas9 double cut yielded a shorter (~423 bp) SnaBI sensitive product. In LynBKO, the 500-bp PCR product was not cleavable by SnaBI.

CskASLynBKO mice were generated by breeding LynBKO into our Csk+/− and CskAS(CskKO) strains and then crossing the progeny Csk+/−LynBKO (or LynKO) and CskAS(CskKO)LynKO (or LynBKO) together, as described previously for CskASLynKO (37), CskASc-CblKO, and CskASCbl-bKO (36). CskASLynAKO mice were also generated in parallel.

DNA constructs, mutagenesis, and transfection of Jurkat cells

His6V5-tagged mouse LynA and Myc-tagged memCskAS constructs have been described previously (36). Site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange Lightning, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used to generate LynAV24L from the WT LynA plasmid DNA. Mutations were confirmed via sequencing (GENEWIZ, South Plainfield, NJ).

After authentication via short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and testing negative for mycoplasma (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), Jurkat-derived JCaM1.6 T cells (43, 44) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5 to 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA) and 2 mM glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). For transient transfections, cells were grown overnight in transfection medium: antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 2 mM glutamine. Batches of 15 million cells were resuspended in transfection medium with 10 to 15 μg each plasmid DNA (LynA and memCskAS). Cells were rested and then electroporated for 10 ms at 285 V in a BTX square-wave unit (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Cells were then resuspended in transfection medium and rested in a cell culture incubator overnight. One million live cells were then resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and rested for 30 min at 37°C before stimulation and analysis.

Preparation of BMDMs, BMDCs, and mast cells

Bone marrow was extracted from femora/tibiae of mice and subjected to hypotonic erythrocyte lysis. BMDMs were generated on untreated plates (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) by culturing in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA) containing ~10% heat-inactivated FBS (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA), sodium pyruvate (0.11 mg/ml), 2 mM penicillin/streptomycin/l-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 10% CMG14-12 cell–conditioned medium as a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF). After 6 or 7 days, cells were resuspended in enzyme-free EDTA buffer, replated, and rested overnight in untreated six-well plates (BD Falcon) at 1 million cells per well in unconditioned medium ± IFN-γ (25 U/ml) (PeproTech, Cranbury, NJ) (36, 74) before stimulation and analysis.

BMDCs were generated on 10-cm tissue culture (TC)–treated plates (Celltreat, Pepperell, MA) in DMEM (Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA). For DC culture, CMG-12-14 supernatant was replaced with murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (10 ng/ml) and murine interleukin-4 (IL-4) (10 ng/ml) (both PeproTech), with medium refreshment on day 4. On day 7, cells were resuspended in enzyme-free EDTA buffer, replated in TC-treated 12-well plates (Celltreat, Pepperell, MA) at 1 million cells per well in DMEM + 10% FBS, and rested overnight at 37°C before analysis. In the final cell mixture, CD11c+ cDCs comprised only 0.5% of live cells and PDCA1+ pDCs comprised 0.1% of live cells, with the major contaminating populations being macrophages (91%) and monocytes (6%).

Bone marrow–derived mast cells were prepared as described previously (36, 75), with CMG14-12 supernatant replaced by murine IL-3 (10 ng/ml; PeproTech). Cells were cultured for at least 5 weeks before lysis and analysis.

Isolation of splenic B cells, DCs, and peripheral blood monocytes

B cells were isolated from 3.5- to 4.5-month-old mice via a negative selection strategy adapted from the EasySep Mouse B Cell Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Mouse spleens were disintegrated in PBS containing 2% FBS and 1 mM EDTA (PBS-FBS-EDTA) and passed through a 40-μm mesh filter. Batches of 100 million cells were resuspended in 1 ml of PBS-FBS-EDTA, mixed with normal rat serum (STEMCELL Technologies), and incubated for 10 min at room temperature (RT) with the following biotinylated antibodies from BioLegend and Tonbo Biosciences (both San Diego, CA): CD3 (BioLegend, 100244), CD64 (BioLegend, 139318), CD4 (Tonbo Biosciences, 30-0041-U100), CD8 (Tonbo Biosciences, 30-0081-U500), CD161/NK1.1 (Tonbo Biosciences, 30-5941-U500), F4/80 (Tonbo Biosciences, 30-4801-U500), Gr-1 (Tonbo Biosciences, 30-5931-U500), CD11c (Tonbo Biosciences, 30-0114-U100), and Ter119 (Tonbo Biosciences, 30-5921-U500).

Splenocytes were then incubated with magnetic MojoSort Streptavidin Nanobeads (BioLegend) and incubated for 3 min at RT. Tubes were then placed inside a column-free EasySep magnet for 3 min. Flow-through was characterized via flow cytometry: From six independent isolations, the B220+ B cells comprised 76 ± 7% of live cells, with the major contaminating populations being (low-Lyn–expressing) NK cells (5 ± 3%) and eosinophils (3 ± 2%).

DCs were isolated via negative selection with the EasySep Mouse Pan-DC Enrichment Kit. From three independent isolations, CD11c+ cDCs comprised 42 ± 4% of live cells and PDCA1+ pDCs comprised 5 ± 1%, with the major contaminating populations being macrophages (5 ± 1%) and (low-Lyn–expressing) NK cells (1%).

Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated from 3.5- to 4.5-month-old mice by negative selection. Blood collected in heparin tubes was subjected to hypotonic lysis to remove erythrocytes. After washing, batches of 100 million cells were resuspended in 1 ml of PBS-FBS-EDTA and isolated by magnetic sorting with the EasySep Mouse Monocyte Isolation Kit (STEMCELL Technologies). Monocyte suspensions were washed and characterized via flow cytometry from six independent isolations, and the final samples contained approximately 61% CD64+MerTK− monocytes, with the largest contaminants being 10% B cells and 2% (non-Lyn–expressing) T cells.

Cell stimulation and immunoblotting

Cultured cells were treated with 10 μM 3-IB-PP1 (K. Shokat, University of California San Francisco) at 37°C before placing on ice, lysing with SDS sample buffer, and preparation for immunoblotting (74). Approximately 0.025 million cell equivalents were run in each lane of a 7% NuPAGE tris-acetate gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to Immobilon-FL polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA). REVERT Total Protein Stain (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) was used as a standard for the whole-sample protein content for quantification (74). After reversing the total protein staining, membranes were treated for 1 hour with Intercept (TBS) Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences) and incubated with the appropriate primary and near-infrared secondary antibodies from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), Abcam (Cambridge, UK), ProMab Biotechnologies (Richmond, CA), R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NE): β-actin 8H10D10 (Cell Signaling Technology, 3700), Erk1/2 3A7 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9107), Fgr 6G2 (ProMab Biotechnologies, 20318), Fyn (Cell Signaling Technology, 4023), Hck 394903 (R&D Systems, MAB3915), LynA + LynB Lyn-01 (Abcam, ab1890), Src (Cell Signaling Technology, 2108), V5 epitope tag D3H8Q (Cell Signaling Technology, 13202), phospho-Erk1/2 (pT202/pY204) D13.14.4E (Cell Signaling Technology, 4370), phospho-Zap70/Syk (pY Zap 319/Syk 352) 65E4 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2717), IRDye 800CW donkey anti-mouse IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, NC9744100), IRDye 800CW donkey anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, NC9523609), and IRDye 680RD donkey anti-mouse IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, 926-68072). Blots were visualized using an Odyssey CLx near-infrared imager (LI-COR Biosciences), and signals were background-subtracted using ImageStudio Software (LI-COR Biosciences) and corrected for whole-lane protein content (total protein stain) (74).

Flow cytometry

Spleens were excised from mice, mechanically disintegrated, and passed through a 70-μm mesh filter. Single-cell suspensions were then subjected to hypotonic erythrocyte lysis and resuspended in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (PBS without Ca2+/Mg2+ supplemented with 2% FBS and 2 mM EDTA). Antibody master mixes for cell surface stains were prepared in FACS buffer, and staining was performed for 1 hour at 4 or 37°C. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized in Cytofix/Cytoperm solution (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 20 min at 4°C. After washing in BD Perm/Wash buffer, intracellular staining was performed overnight at 4°C with antibodies in Perm/Wash buffer. Following washing, samples were resuspended in PBS with 0.5% paraformaldehyde. Flow cytometry was performed on Fortessa X-30, and data were analyzed using FlowJo software. Flow cytometry antibodies were combined as appropriate from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA), Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tonbo Biosciences, and BioLegend: B220 RA3-6B2 BUV395 (BD Biosciences), CD4 GK1.5 BUV395 (BD Biosciences), CD8a 53-6.7 BUV737 (BD Biosciences), CD11b M1/70 BUV395/A700/BUV737 (BD Biosciences), CD11c HL3 BUV737 (BD Biosciences), CD16/32 2.4G2 (Tonbo Biosciences), CD19 6D5 BV711 (BioLegend), CD21/35 7E9 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (BioLegend), CD23 B3B4 phycoerythrin (PE) (BioLegend), CD25 PC61 BV605 (BioLegend), CD38 90 A700 (BioLegend), CD44 IM7 peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)–Cy5.5 (Tonbo Biosciences), CD45 30-F11 A700/BUV496 (BioLegend), CD62L MEL-14 BV510 (BioLegend), CD64 X54-5/7.1 BV711 (BioLegend), CD69 H1.2F3 FITC (Tonbo Biosciences), CD80 B7-1/16-10A1 PE (Tonbo Biosciences), CD86 B7-2/PO3.1 PE (Tonbo Biosciences), CD93 AA4.1 allophycocyanin (APC) (BioLegend), CD138 281-2 BV421 (BioLegend), CD170/Siglec-F S17007L FITC (BioLegend), CD185 L138D7 PE (BioLegend), CD206 C068C2 BV650 (BioLegend), FoxP3 3G3 PE-Cy7 (Tonbo Biosciences), Ghost Dye Red 780 (Tonbo Biosciences), GL7 PerCP-Cy5.5 (BioLegend), I-A/I-E M5/114.15.2 BV510 (BioLegend), IgD 11-26C.1 BV786 (BD Biosciences), IgM RMM-1 PE-Cy7 (BioLegend), Intracellular Ig 550589 PE (BD Biosciences), Ly6C HK1.3 BV785 (BioLegend), Ly6G 1A8 PerCP-Cy5.5 (Tonbo Biosciences), MerTK DS5MMER PE-Cy7 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), NK1 PK136 BV421 (BioLegend), PD-1 29F.1A12 BV785 (BioLegend), PDCA-1 927 BV421 (BioLegend), TCRβ H57-597 FITC/APC (Tonbo Biosciences), and XCR1 ZET FITC and APC (BioLegend).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Spleens and kidneys were excised from aged mice and frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound before sectioning. Sections of 5-μm thickness were cut from each block and kept frozen (76). Before staining, sections were dried for 30 min, fixed for 15 min in ice-cold acetone, dried for 10 min, and washed for 5 min in PBS-based buffer with 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Sections were then blocked for 1 hour with 2% BSA and 1:100 Fc Shield (Tonbo Biosciences) in PBS and then washed for 5 min. Spleen sections were further blocked using an endogenous biotin blocking kit (Invitrogen) and washed 3 × 5 min. Spleen sections were then stained overnight at 4°C with CD11b-AF594 (M1/70), TCRβ-AF647 (H57-597), GL7-biotin (GL7), and B220-FITC (RA3-6B2). Kidney sections were stained with C3-FITC (RmC11H9) and goat anti-mouse FC–Texas Red (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Stained sections were washed 3 × 5 min. Spleen sections were subsequently stained for 1 hour with Streptavidin–DyLight 550 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) secondary antibody and washed. Sections were mounted with ProLong Gold DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)–infused mounting media (Cell Signaling Technology) and glass coverslips. Slides were imaged on a Leica DM6000B fluorescence microscope at ×5, ×20, or ×40 magnification. Sixteen tiled images from each kidney were merged for analysis. C3/Ig deposition was quantified in batch using Imaris software (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK).

H&E staining and scoring

Spleen and kidney sections were H&E-stained for pathological assessment of tissue architecture and glomerulonephritis. Sections were dried for 30 min at RT and fixed for 15 min in ice-cold acetone. Sections were then rinsed for 2 min in PBS, stained for 2 min with hematoxylin quick stain (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and rinsed again in water until clear. Sections were then stained for 1 min with eosin (Vector), rinsed 2 × 5 min in 95% ethanol, rinsed 2 × 5 min in 100%, and cleared for 10 min in a xylene mixture. Slides were mounted with VectaMount medium (Vector Laboratories). Kidney images were deidentified and sent to a pathologist for disease scoring of glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis (77). Scoring was performed on a 0 to 3 scale (0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = severe) based on glomerular size, hypercellularity, and sclerosis; interstitial disease was assessed on the basis of the degree of inflammatory infiltrate and alteration in tissue architecture.

Trichrome staining

Kidney or spleen sections were dried for 30 min and fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at RT. The Trichrome Stain Kit (Abcam ab150686) was then used to stain sections according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, sections were incubated for 1 hour at 60°C in Bouin’s fluid, rinsed, and incubated for 5 min in Weigert’s hematoxylin, rinsed, stained for 15 min with Biebrich scarlet/acid fuschin, rinsed, incubated for 10 min in phosphomolybdic/phosphotungstic acid, stained for 15 min with aniline blue, rinsed in deionized water, and then incubated for 5 min in 1% acetic acid. Sections were then dehydrated with two rinses with 95% ethanol and two rinses with 100% ethanol, cleared with xylene, and mounted with VectaMount medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Slides were imaged on a bright-field microscope and analyzed using NIH ImageJ Fiji.

Serum collection from mice

Blood was harvested via venipuncture from the submandibular vein of mice or via retroorbital bleed and allowed to clot at RT for 90 min, after which it was spun at 4000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. The resulting serum supernatant was then aliquoted and placed on ice for immediate use or stored at −80°C.

BAFF analysis

The Quantikine ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) Kit for Mouse BAFF/BLyS/TNFSF13B (R&D Systems, catalog no. MBLYS0) was used to quantify serum levels of BAFF. Assay Diluent RD1N (80 μl) was added to each well of a microplate. Standard or sample (40 μl, after 1:50 dilution in Calibrator Diluent RD6-12) was added to each well in technical duplicate. Other reagents were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were incubated for 2 hours at RT on a horizontal orbital shaker at 225 rpm. Each well was then washed 5×. Mouse BAFF/BLyS Conjugate (120 μl) was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours at RT on the orbital shaker. After washing, 120 μl of Substrate Solution was added to each well and incubated for 30 min in the dark. Stop solution (120 μl) was then added to each well. Optical density (OD) at 450 nm was measured immediately using the Bio-Rad iMark Microplate Reader. The average OD from each sample was converted to picogram per milliliter value with reference to the standard curve and correction for dilution.

IgM analysis

Wells in polystyrene 96-well plates were coated with 50 μl of anti-mouse IgM Fab2 (prepared at 1 μg/ml in PBS), incubated overnight, washed 6× with distilled water, blocked for 1 hour at RT with 50 μl of PBS-BB (PBS without Ca2+/Mg2+, 0.05% Tween 20, and 1% BSA), and initiated with 50 μl of 1:60,000 diluted serum. After incubation for 2 hours at RT, wells were washed 6×. Biotinylated anti-mouse IgM (50 μl at 500 ng/ml) was then added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at RT. After washing, 50 μl of streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (diluted 1:40 in PBS-BB) was added to each well and incubated for 1 hour at RT. After washing, ELISA results were visualized by adding 50 μl of trimethylboron:peroxide and stopped with 50 μl of sulfuric acid (1 N). Relative amounts of IgM were determined by measuring the OD at 450 nm using the Bio-Rad iMark Microplate Reader.

ANA detection

Kallestad HEp-2 (Bio-Rad, catalog no. 30472) was used to detect ANA staining according to the manufacturer’s instruction, modified to detect mouse IgG. Briefly, wells were incubated with 40 μl of mouse serum, diluted 40× in PBS with 1% BSA, at RT for 20 min. After incubation, slides were washed in PBS for 10 min and incubated with 30 μl of FITC-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, catalog no. 115-095-164) diluted 200× in DAPI for 20 min at RT, followed by a 10-min PBS wash. Slides were then mounted and coverslipped and viewed on an Olympus BX51 fluorescent microscope equipped with a digital camera and DP-BSW software (Olympus). Images were quantified, pseudo-colored, and merged using ImageJ software (NIH) with the Fiji plugin.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Significance was typically assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, unless otherwise indicated. For cellularity analyses, outliers were identified using robust regression and outlier removal (ROUT) analysis (Q = 1%). Student’s t test was used for simple, two-way comparisons. Contingency data were assessed using two-sided Fisher’s exact test with Welch’s correction, with and without Bonferroni correction. To meet the test conditions, data were binarized as indicated by combining no/mild disease groups or mild/severe groups. Error bars typically reflect 95% confidence interval (CI) or SEM, and n values reflect individual animals, pooled from multiple independent experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Bagchi, Y. You, the University of Minnesota Mouse Genetics Laboratory, and the University of Minnesota Genome Engineering Shared Resource for technical assistance; K. Shokat and F. Rutaganira for supplying the CskAS inhibitor 3-IB-PP1; J. Williams and J. Mitchell for microscopy advice and assistance; and J. Zikherman, M. Headley, J. Hamerman, A. O’Rourke, C. Abram, M. Jenkins, K. Pape, G. Randolph, J. Brooks, C. Sellner, B. Burbach, K. Schwertfeger, M. Farrar, C. Lange, and J. Connett for valuable protocols, feedback, and discussion.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grant R01AR073966 (to T.S.F.), NIH supplement 3R01AR073966-03S1 (to T.S.F.), NIH grant R03AI130978 (to T.S.F.), NIH grant T32DA007097 (to B.F.B.), NIH grant T32CA009138 (to M.L.S. and J.T.G.), American Cancer Society–Kirby Foundation Postdoc Fellowship PF-21-068-01-LIB (to J.T.G.), University of Minnesota Center for Immunology New Mouse Award (to T.S.F.), University of Minnesota Foundation Equipment Award E-0918-01 (to T.S.F.), and University of Minnesota Center for Autoimmune Diseases Research Pilot Grant (to T.S.F.)

Author contributions: Conceptualization: B.F.B. and T.S.F. Methodology: B.F.B., J.T.G., M.L.S., A.J.L., J.L.A., B.L.R., B.S.M., C.A.L., B.A.B., and T.S.F. Investigation: B.F.B., M.L.S., J.T.G., O.L.F., S.E.S., A.J.L., L.A.R., J.L.A., M.G.N., W.L.S., C.A.L., and T.S.F. Visualization: B.F.B., J.T.G., J.L.A., and T.S.F. Funding acquisition: B.F.B., J.T.G., M.L.S., and T.S.F. Project administration: T.S.F. Supervision: T.S.F. Writing—original draft: B.F.B. and T.S.F. Writing—review and editing: B.F.B., M.L.S., J.T.G., O.L.F., S.E.S., A.J.L., L.A.R., J.L.A., M.G.N., W.L.S., B.L.R., B.S.M., C.A.L., B.A.B., and T.S.F.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S21

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Yamanashi Y., Fukui Y., Wongsasant B., Kinoshita Y., Ichimori Y., Toyoshima K., Yamamoto T., Activation of Src-like protein-tyrosine kinase Lyn and its association with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase upon B-cell antigen receptor-mediated signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 1118–1122 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith K. G., Tarlinton D. M., Doody G. M., Hibbs M. L., Fearon D. T., Inhibition of the B cell by CD22: A requirement for Lyn. J. Exp. Med. 187, 807–811 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodie E. J., Infantino S., Low M. S. Y., Tarlinton D. M., Lyn, lupus, and (B) lymphocytes, a lesson on the critical balance of kinase signaling in immunity. Front. Immunol. 9, 401 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scapini P., Pereira S., Zhang H., Lowell C. A., Multiple roles of Lyn kinase in myeloid cell signaling and function. Immunol. Rev. 228, 23–40 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brian B. F., Freedman T. S., The Src-family kinase lyn in immunoreceptor signaling. Endocrinology 162, bqab152 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene J. T., Brian B. F., Senevirathne S. E., Freedman T. S., Regulation of myeloid-cell activation. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 73, 34–42 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan V. W., Lowell C. A., DeFranco A. L., Defective negative regulation of antigen receptor signaling in Lyn-deficient B lymphocytes. Curr. Biol. 8, 545–553 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross A. J., Lyandres J. R., Panigrahi A. K., Prak E. T., DeFranco A. L., Developmental acquisition of the Lyn-CD22-SHP-1 inhibitory pathway promotes B cell tolerance. J. Immunol. 182, 5382–5392 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma J., Abram C. L., Hu Y., Lowell C. A., CARD9 mediates dendritic cell-induced development of Lyn deficiency-associated autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Sci. Signal. 12, eaao3829 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ban T., Sato G. R., Nishiyama A., Akiyama A., Takasuna M., Umehara M., Suzuki S., Ichino M., Matsunaga S., Kimura A., Kimura Y., Yanai H., Miyashita S., Kuromitsu J., Tsukahara K., Yoshimatsu K., Endo I., Yamamoto T., Hirano H., Ryo A., Taniguchi T., Tamura T., Lyn kinase suppresses the transcriptional activity of IRF5 in the TLR-MyD88 pathway to restrain the development of autoimmunity. Immunity 45, 319–332 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamagna C., Scapini P., van Ziffle J. A., DeFranco A. L., Lowell C. A., Hyperactivated MyD88 signaling in dendritic cells, through specific deletion of Lyn kinase, causes severe autoimmunity and inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E3311–E3320 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keck S., Freudenberg M., Huber M., Activation of murine macrophages via TLR2 and TLR4 is negatively regulated by a Lyn/PI3K module and promoted by SHIP1. J. Immunol. 184, 5809–5818 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu R., Vidal G. S., Kelly J. A., Vega A. M. D., Howard X. K., Macwana S. R., Dominguez N., Klein W., Burrell C., Harley I. T., Kaufman K. M., Bruner G. R., Moser K. L., Gaffney P. M., Gilkeson G. S., Wakeland E. K., Li Q.-Z., Langefeld C. D., Marion M. C., Divers J., Alarcón G. S., Brown E. E., Kimberly R. P., Edberg J. C., Goldman R. R., Reveille J. D., Mc Gwin G. Jr., Vilá L. M., Petri M. A., Bae S.-C., Cho S.-K., Bang S.-Y., Kim I., Choi C.-B., Martin J., Vyse T. J., Merrill J. T., Harley J. B., Riquelme M. E. A.; BIOLUPUS, GENLES Multicenter Collaborations, Nath S. K., James J. A., Guthridge J. M., Genetic associations of LYN with systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 10, 397–403 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Consortium for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Genetics (SLEGEN), Harley J. B., A.-Riquelme M. E., Criswell L. A., Jacob C. O., Kimberly R. P., Moser K. L., Tsao B. P., Vyse T. J., Langefeld C. D., Nath S. K., Guthridge J. M., Cobb B. L., Mirel D. B., Marion M. C., Williams A. H., Divers J., Wang W., Frank S. G., Namjou B., Gabriel S. B., Lee A. T., Gregersen P. K., Behrens T. W., Taylor K. E., Fernando M., Zidovetzki R., Gaffney P. M., Edberg J. C., Rioux J. D., Ojwang J. O., James J. A., Merrill J. T., Gilkeson G. S., Seldin M. F., Yin H., Baechler E. C., Li Q.-Z., Wakeland E. K., Bruner G. R., Kaufman K. M., Kelly J. A., Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat. Genet. 40, 204–210 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liossis S. N., Solomou E. E., Dimopoulos M. A., Panayiotidis P., Mavrikakis M. M., Sfikakis P. P., B cell kinase lyn deficiency in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Invest. Med. 49, 157–165 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flores-Borja F., Kabouridis P. S., Jury E. C., Isenberg D. A., Mageed R. A., Decreased Lyn expression and translocation to lipid raft signaling domains in B lymphocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 52, 3955–3965 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hibbs M. L., Tarlinton D. M., Armes J., Grail D., Hodgson G., Maglitto R., Stacker S. A., Dunn A. R., Multiple defects in the immune system of Lyn-deficient mice, culminating in autoimmune disease. Cell 83, 301–311 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harder K. W., Parsons L. M., Armes J., Evans N., Kountouri N., Clark R., Quilici C., Grail D., Hodgson G. S., Dunn A. R., Hibbs M. L., Gain- and loss-of-function Lyn mutant mice define a critical inhibitory role for Lyn in the myeloid lineage. Immunity 15, 603–615 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu C. C. K., Yen T. S. B., Lowell C. A., DeFranco A. L., Lupus-like kidney disease in mice deficient in the Src family tyrosine kinases Lyn and Fyn. Curr. Biol. 11, 34–38 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollard K. M., Gender differences in autoimmunity associated with exposure to environmental factors. J. Autoimmun. 38, J177–J186 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubtsov A. V., Rubtsova K., Kappler J. W., Marrack P., Genetic and hormonal factors in female-biased autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 9, 494–498 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quintero O. L., Amador-Patarroyo M. J., Montoya-Ortiz G., Rojas-Villarraga A., Anaya J. M., Autoimmune disease and gender: Plausible mechanisms for the female predominance of autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 38, J109–J119 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syrett C. M., Anguera M. C., When the balance is broken: X-linked gene dosage from two X chromosomes and female-biased autoimmunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 106, 919–932 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fink A. L., Engle K., Ursin R. L., Tang W. Y., Klein S. L., Biological sex affects vaccine efficacy and protection against influenza in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 12477–12482 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein S. L., Hodgson A., Robinson D. P., Mechanisms of sex disparities in influenza pathogenesis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 92, 67–73 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozcelik T., X chromosome inactivation and female predisposition to autoimmunity. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 34, 348–351 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Souyris M., Cenac C., Azar P., Daviaud D., Canivet A., Grunenwald S., Pienkowski C., Chaumeil J., Mejía J. E., Guéry J.-C., TLR7 escapes X chromosome inactivation in immune cells. Sci. Immunol. 3, eaap8855 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricker E., Manni M., Flores-Castro D., Jenkins D., Gupta S., Rivera-Correa J., Meng W., Rosenfeld A. M., Pannellini T., Bachu M., Chinenov Y., Sculco P. K., Jessberger R., Luning Prak E. T., Pernis A. B., Altered function and differentiation of age-associated B cells contribute to the female bias in lupus mice. Nat. Commun. 12, 4813 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hao Y., O’Neill P., Naradikian M. S., Scholz J. L., Cancro M. P., A B-cell subset uniquely responsive to innate stimuli accumulates in aged mice. Blood 118, 1294–1304 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubtsov A. V., Rubtsova K., Fischer A., Meehan R. T., Gillis J. Z., Kappler J. W., Marrack P., Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)-driven accumulation of a novel CD11c+ B-cell population is important for the development of autoimmunity. Blood 118, 1305–1315 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenks S. A., Cashman K. S., Zumaquero E., Marigorta U. M., Patel A. V., Wang X., Tomar D., Woodruff M. C., Simon Z., Bugrovsky R., Blalock E. L., Scharer C. D., Tipton C. M., Wei C., Lim S. S., Petri M., Niewold T. B., Anolik J. H., Gibson G., Lee F. E.-H., Boss J. M., Lund F. E., Sanz I., Distinct effector b cells induced by unregulated toll-like receptor 7 contribute to pathogenic responses in systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunity 49, 725, 739.e6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamagna C., Hu Y., DeFranco A. L., Lowell C. A., B cell-specific loss of Lyn kinase leads to autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 192, 919–928 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yi T. L., Bolen J. B., Ihle J. N., Hematopoietic cells express two forms of lyn kinase differing by 21 amino acids in the amino terminus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 2391–2398 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvarez-Errico D., Yamashita Y., Suzuki R., Odom S., Furumoto Y., Yamashita T., Rivera J., Functional analysis of Lyn kinase A and B isoforms reveals redundant and distinct roles in Fc ε RI-dependent mast cell activation. J. Immunol. 184, 5000–5008 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tornillo G., Knowlson C., Kendrick H., Cooke J., Mirza H., Aurrekoetxea-Rodríguez I., Vivanco M. D. M., Buckley N. E., Grigoriadis A., Smalley M. J., Dual mechanisms of LYN kinase dysregulation drive aggressive behavior in breast cancer cells. Cell Rep. 25, 3674–3692.e10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brian B. F. IV, Jolicoeur A. S., Guerrero C. R., Nunez M. G., Sychev Z. E., Hegre S. A., Sætrom P., Habib N., Drake J. M., Schwertfeger K. L., Freedman T. S., Unique-region phosphorylation targets LynA for rapid degradation, tuning its expression and signaling in myeloid cells. eLife 8, e46043 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freedman T. S., Tan Y. X., Skrzypczynska K. M., Manz B. N., Sjaastad F. V., Goodridge H. S., Lowell C. A., Weiss A., LynA regulates an inflammation-sensitive signaling checkpoint in macrophages. eLife 4, e09183 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma X., Chen C., Veevers J., Zhou X. M., Ross R. S., Feng W., Chen J., CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene manipulation to create single-amino-acid-substituted and floxed mice with a cloning-free method. Sci. Rep. 7, 42244 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miura H., Quadros R. M., Gurumurthy C. B., Ohtsuka M., Easi-CRISPR for creating knock-in and conditional knockout mouse models using long ssDNA donors. Nat. Protoc. 13, 195–215 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madeira F., Park Y. M., Lee J., Buso N., Gur T., Madhusoodanan N., Basutkar P., Tivey A. R. N., Potter S. C., Finn R. D., Lopez R., The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, W636–W641 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gasteiger E., Gattiker A., Hoogland C., Ivanyi I., Appel R. D., Bairoch A., ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Supek F., Lehner B., Lindeboom R. G. H., To NMD or not to NMD: Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in cancer and other genetic diseases. Trends Genet. 37, 657–668 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldsmith M. A., Weiss A., Isolation and characterization of a T-lymphocyte somatic mutant with altered signal transduction by the antigen receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6879–6883 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Straus D. B., Weiss A., Genetic evidence for the involvement of the lck tyrosine kinase in signal transduction through the T cell antigen receptor. Cell 70, 585–593 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okuzumi T., Ducker G. S., Zhang C., Aizenstein B., Hoffman R., Shokat K. M., Synthesis and evaluation of indazole based analog sensitive Akt inhibitors. Mol. Biosyst. 6, 1389–1402 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okuzumi T., Fiedler D., Zhang C., Gray D. C., Aizenstein B., Hoffman R., Shokat K. M., Inhibitor hijacking of Akt activation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 484–493 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schoenborn J. R., Tan Y. X., Zhang C., Shokat K. M., Weiss A., Feedback circuits monitor and adjust basal Lck-dependent events in T cell receptor signaling. Sci. Signal. 4, ra59 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown M. T., Cooper J. A., Regulation, substrates and functions of src. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1287, 121–149 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chow L. M., Veillette A., The Src and Csk families of tyrosine protein kinases in hemopoietic cells. Semin. Immunol. 7, 207–226 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yokoyama N., Miller W. T., Identification of residues involved in v-Src substrate recognition by site-directed mutagenesis. FEBS Lett. 456, 403–408 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan Y. X., Manz B. N., Freedman T. S., Zhang C., Shokat K. M., Weiss A., Inhibition of the kinase Csk in thymocytes reveals a requirement for actin remodeling in the initiation of full TCR signaling. Nat. Immunol. 15, 186–194 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]