Abstract

Tumor cell–derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) are being explored as circulating biomarkers, but it is unclear whether bulk measurements will allow early cancer detection. We hypothesized that a single-EV analysis (sEVA) technique could potentially improve diagnostic accuracy. Using pancreatic cancer (PDAC), we analyzed the composition of putative cancer markers in 11 model lines. In parental PDAC cells positive for KRASmut and/or P53mut proteins, only ~40% of EVs were also positive. In a blinded study involving 16 patients with surgically proven stage 1 PDAC, KRASmut and P53mut protein was detectable at much lower levels, generally in <0.1% of vesicles. These vesicles were detectable by the new sEVA approach in 15 of the 16 patients. Using a modeling approach, we estimate that the current PDAC detection limit is at ~0.1-cm3 tumor volume, below clinical imaging capabilities. These findings establish the potential for sEVA for early cancer detection.

Single-vesicle analysis of human plasma with the sEVA method allows detection of stage 1 pancreatic cancers.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) currently represents the third leading cause of cancer death in the United States, and it is expected to become the second leading cause by 2030 (1). In 2021, 60,430 Americans are expected to develop pancreatic cancer and an estimated 48,220 Americans will die from the disease (https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html). The only way to cure pancreatic cancer is to surgically resect it when it is still localized. Under the current therapeutic paradigm, only 20% of patients will present with surgically resectable disease, while 40% will present with localized but surgically unresectable disease and 40% will present with metastatic disease. Despite state-of-the-art computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and endoscopic ultrasound for patients with “localized disease by imaging” and who undergo surgery, the rate of pathologically positive margins is 40 to 70% and the rate of pathologically positive peri-pancreatic nodal disease is 60 to 80%. If we are to cure more patients with pancreatic cancer, new diagnostic tools are necessary to identify patients with preclinical and truly localized disease and to explore novel therapeutic approaches to allow for more R0/N0 resections.

High-resolution, contrast-enhanced CT and MRI imaging are routinely obtained, but their sensitivity in detecting minimal disease is often limited especially in the neoadjuvant (2) and postoperative settings. Technological advances continue to rapidly improve the capacity to detect circulating biomarkers in blood samples (3, 4). These “liquid biopsy” markers include mutated or methylated cell-free DNA (cfDNA) (5–8), tumor-associated extracellular vesicles (EVs) (9), circulating tumor cells (10), and metabolic parameters (e.g., onset of diabetes and muscle wasting) (11). Although EV, cfDNA, and metabolism markers have already shown promise for PDAC diagnostics, their current detection sensitivities require further improvements to be clinically useful. Especially in early disease, the lower diagnostic accuracy is likely due to the large stromal component of PDAC, coexistence with focal areas of pancreatitis indistinguishable from tumor-free pancreatitis, and the low quantity of circulating biomarkers at early stages (7).

We and others have developed a number of methods to analyze EV (12–15). Many of the earlier techniques relied on bulk measurements requiring 102 to 106 EVs for a single measurement; while single EV methods [single-EV analysis (sEVA) with multifluorescence, single-particle interferometric reflectance imaging with fluorescence, nanoparticle tracking analysis, microfluidic resistive pulse sensing, and nanoflow cytometry] are being actively developed, they measure different parameters (often size rather than molecular biomarkers) (16, 17). Irrespective of the specific physical measurement, the next question is which molecular biomarker to assay. While research is still ongoing, it has also become apparent that many of the described biomarkers have failed in larger clinical validation cohorts (18–20). One of the key questions that have thus emerged is whether this failure is due to the choice of a given molecular biomarker, the extreme heterogeneity of PDAC, or the inability to accurately detect very small numbers of biomarker-positive EV in a population of normal EV.

We argue that one way to address the current question is to perform sEVA because the identification of a small number of tumor-originating EV (such as those found in microscopic cancers) in a background of host EV may be impossible by bulk methods. We furthermore hypothesized that mutated oncoproteins (e.g., KRASmut) or tumor suppressor genes (e.g., P53mut) can potentially be detected in single EV, while the same mutations occurring in cancer cells are causal in increased tumoral EV shedding (21–24). The choice of detecting these mutated proteins is also driven by their early appearance in the PDAC development cascade (25, 26). Last, we reasoned that detection efficiency could be improved by multiplexed measurements of several biomarkers. On the basis of these paradigms, we have developed and validated a robust sEVA technique that allows multiplexed protein measurements in individual EV. We apply the sEVA technique to unanswered questions such as (i) what is the inherent heterogeneity of putative cancer cell–associated proteins in EV, (ii) what is the frequency of mutant onco/tumor suppressor proteins in single EV, and (iii) what are the expression levels of two or more cancer-associated proteins on individual EV? The option of “covering” more tumor-derived EV (tEV) by nonoverlapping markers or obtaining “highly specific” EV identification like KRASmut and P53mut presents as a solid option to improve clinical PDAC diagnostics.

RESULTS

sEVA is a robust analytical tool

It is increasingly being recognized that molecular analysis of EV populations will require single-vesicle analysis. Compared to bulk methods, single-vesicle analysis allows several additional avenues of hypothesis testing such as (i) colocalization of distinct molecular markers on the same vesicle, (ii) frequency distribution of markers across the population, and (iii) with principal components or t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis, description of discrete EV subpopulations.

In an effort to develop a clinically useful sEVA tool, we considered multiple prerequisites: (i) the need to unambiguously define an entire EV population by a universal labeling approach since not all molecular markers are present in all EVs, (ii) the need for antibodies with very high affinity and low nonspecific binding, and (iii) the need to maximally reduce background signal by stringent purification. To address the first prerequisite, a number of general labeling approaches were tested but many ultimately proved unsuitable for total EV identification. Lipid insertion approaches (e.g., DiI and DiO labeling), while able to generate extremely bright EV, have also been shown to assemble into micellular lipid dye aggregates that cannot be readily distinguished or purified from bona fide EV. Other approaches such as wheat germ agglutinin, phosphatidylserine binding moieties, or specific protein-labeling approaches such as CD63 ignore that none of these molecules are present on 100% of EVs, leaving open the possibility that EVs harboring informative markers are not considered (27). We thus optimized a labeling approach using fluorochrome-polyethylene glycol-2,3,5,6-tetrafluorophenyl esters (“TFP”) to fluorescently label free amines of EV surface proteins (Fig. 1A and fig. S1), incorporating a long PEG12 linker to optimize labeling efficiency and water solubility and reduce nonspecific EV binding/aggregation. This labeling approach has no anticipated bias toward differently sized EV, as it labels any accessible surface proteins equally well.

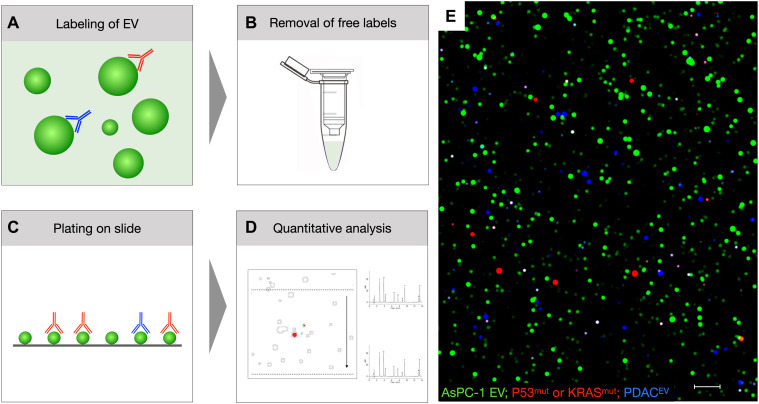

Fig. 1. Overview of sEVA.

(A) EVs are labeled in solution with (i) the protein-reactive TFP dye (green) and (ii) biomarker-specific fluorescent antibodies [red, far red (shown in blue)]. (B) Following purification to remove unbound TFP and fluorescent antibodies, the EVs are (C) pipetted onto hydrophobic glass sides and (D and E) imaged and then analyzed. See fig. S1 for details on labeling and fig. S2 for the computational analysis pipeline. The image in (E) represents an example of AsPC-1 EV stained with TFP-AF488 (green) to label all EV KRASmut or P53mut (red channel) and EGFR, MUC1, and/or FG-P4OH (blue; scale bar, 1 μm).

Having a bright, stable, and full-coverage pan-EV–labeling strategy is also important because it (i) allows calculation of the fraction of biomarker-positive EV (and thus set thresholds) and (ii) can be used to identify staining artifacts in non–TFP-labeled objects. The latter is due to the fact that despite considerable methodological improvements, off-target (i.e., non–TFP-localized) antibody signals, although rare, were present at similar frequencies between positive and negative controls. The major methodological improvements developed during the optimization of the sEVA protocol to reduce the incidence of nonspecific antibody signal included (i) using only very pure EV samples from size exclusion chromatography, (ii) using a low antibody concentration (13 nM), with high blocking buffer concentration, and in the most considerable improvement, (iii) performing an additional column purification to separate antibody-stained EV from free fluorescent antibodies that are retained on the column (Fig. 1B and fig. S1). The in-solution sEVA staining strategy was superior to a previously developed single-EV technique that required EV capture to glass slides before staining (17). On-slide staining requires strong EV attachment (such as streptavidin and biotin capture), which introduces biotinylation manipulation of EV and may bias EV capture while also requiring involved chemical manipulations to coat glass slides with streptavidin/neutravidin. In our hands, these manipulations resulted in nonhomogeneous background signal and introduction of artifacts that could be hard to distinguish from EV events. Strong capture is required for on-slide staining to allow for washing; however, we found that no washing conditions tested were harsh enough for total removal of background fluorescent antibody signal without also stripping EV off the glass. This, of course, is undesirable when rare EVs are being evaluated. Staining in-solution and then cleaning on column allowed us to attach EV on high optical purity commercial glass slides coated with a hydrophobic surface (Fig. 1C and fig. S1). EV can be adhered by hydrophobic interactions within 30 min, and since no additional washing is required, they show minimal mobility and deposited EV can be found in the same location over several days.

A considerable number of putative biomarkers have been proposed for the detection of PDAC including MUC1, MUC2, MUC4, MUC5AC, MUC6, DAS-1, PSCA, TSP-1, TSP-2, PLEC1, S100A4, STMN1, ZEB1, HOOK1, PTPN6, FBN1, CD73, CLDN18, TIMP1, EphA2, CYFRA21-1, LRG1, MSLN, HER2, and GRP94, among others (9, 20, 28–40). Most of the above studies were performed as bulk analyses of EV. In the current study, we hypothesized that single-vesicle analysis of cancer-specific mutated onco/tumor suppressor proteins in EV such as KRASmut and P53mut could improve sensitivity and specificity (26, 29). This approach was facilitated by the recent availability of mutant-specific KRAS and P53 antibodies. We were interested in detecting both specific mutations (e.g., KRASG12D versus KRASG12V) and in detecting all vesicles that harbored any mutated onco/tumor suppressor protein. For this reason, we labeled/detected different specific KRASmut antibodies and a pan-P53mut antibody with the same fluorochrome to allow colocalization with other proteins (Fig. 2). We also added a three-marker PDACEV panel (MUC1, EGFR, and FG-P4OH), which was a truncated version of an earlier bulk analysis panel that incorporated five biomarkers for late-stage PDAC (EGFR, MUC1, EPCAM, GPC1, and WNT2) (9).

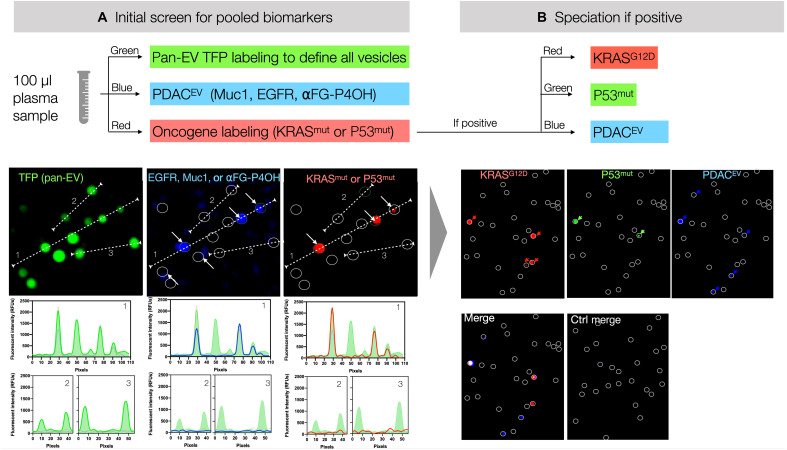

Fig. 2. Workflow of sEVA.

(A) In an initial screen, EVs are labeled for pooled biomarkers as shown. For example, onco/tumor suppressor gene labeling contains three antibodies labeled with the same fluorochrome (KRASG12D, KRASG12V, and P53mut; red channel); additional pancreatic cancer markers (EGFR, MUC1, and α FG-P4OH) are shown in the blue channel. Note the high signal-to-noise ratio of labeling individual EV as shown in the dashed lines (e.g., 1, 2, or 3). (B) In case of positivity, any of the channels can be subspeciated, where each antibody contains a separate fluorochrome as shown. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

EVs were then imaged by high-resolution microscopy and analyzed in ImageJ (Fig. 1D and fig. S1). The computational pipeline is summarized in fig. S2. Briefly, images were confirmed to be free of large artifacts or background abnormalities and found to contain sufficient TFP-labeled EV per field of view (FOV) (>500). Measurements of the marker signal intensities within TFP regions of interest (ROIs) from background-subtracted images were imported to GraphPad Prism 8, and a positive threshold was determined by maximum likelihood ratio of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis between positive (cell lines/late clinical) and negative (cell lines/healthy control) samples.

Using a 2-pixel Gaussian blur, EVs labeled with AF488-TFP (green) could be readily observed over the negligible background (Figs. 1 and 2) with a signal-to-noise ratio of >20. In the Texas Red acquisition channel, we detected EVs positive for either KRASG12D, KRASG12V, or P53mut. In the Cy5.5 channel, we detected EVs positive for either EGFR overexpression, MUC1, or FG-P4OH. Care was taken to use EV concentrations such that, once adhered to the glass slide, their spatial separation would minimize the statistical coincidence of these signals.

EVs derived from PDAC cell lines show heterogeneous biomarker expression

Armed with a robust and practical method for identifying all EVs via fluorophore-TFP labeling and characterization via fluorescently labeled antibodies, we next sought to characterize EV from well-established PDAC models. A key question was: If a parental PDAC cell ubiquitously expresses a defining cancer biomarker, what is the frequency at which the same biomarker can be identified in the entire EV population produced by the cell line? One would intuitively think that the ratio is 1:1, but we had previously observed that this was not always the case, hence a reason for more in-depth analysis.

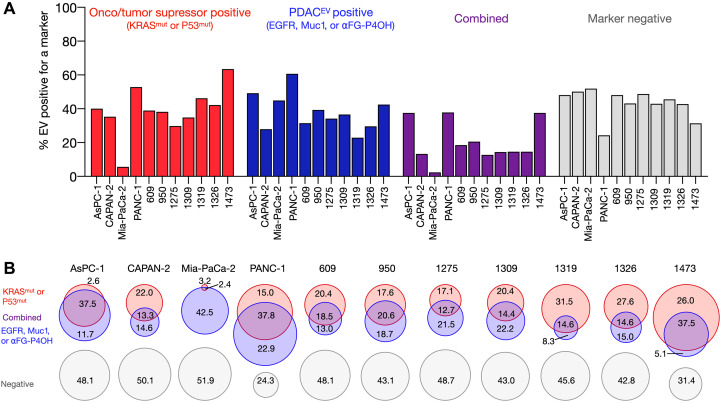

Starting with the AsPC-1 cell line, we found that essentially all parental cells stained positive for KRASmut or P53mut (41). With respect to harvested EV, only 3% were positive for KRASG12D or P53mut alone and another 38% were double-positive for the onco/tumor suppressor proteins and MUC1, EGFR, or αFG-P4OH. In summary, 48% of EVs were negative for any of the markers. As shown in Fig. 2, there was clear separation of EV signals. Similar data were observed across three other pancreatic cancer cell lines, although the biomarker expression ranged considerably. MIA-PaCa-2 demonstrated the lowest percent coverage with the combinatorial marker panels of any of the tested cell lines, with 52% of the analyzed MIA-PaCa-2 EV being negative for any of the six markers (Fig. 3B). This may not be entirely surprising as MIA-PaCa-2 is a KRASG12C cell line (G12C-specific analysis was not included in our testing panel given the lack of reliable antibodies at this time). The cell line is positive for P53mut signal, but the EV fraction had a disproportionately lower amount of P53mut when compared to EV from other cell lines with P53 mutations. This may be related to altered EV packaging or molecular defects in the exosome pathway (42). PANC-1 showed the highest marker coverage, with 75.7% of their EVs being positive for at least one of the tested markers (Fig. 3B). With these marker sets, we observed that most EVs were dual positive in both channels, meaning they had at least one of KRASG12D/G12V or P53mut and at least one of EGFR, MUC1, or FG-P4OH. The biomarker expression levels were similar over time when EVs were retested, i.e., similar fingerprints were observed.

Fig. 3. sEVA analysis across multiple PDAC cell line–derived EVs.

(A) Summary graph of the % EVs that stain for (i) KRASmut or P53mut (red); (ii) EGFR, MUC1, or FG-P4OH (blue); (iii) at least one of each of the former two marker panels (purple); or (iv) no marker (gray). The sum of EV was determined by pan-TFP labeling. Each column represents a different cell line or PDX line (see table S1 for characteristics of parental cells). (B) Data plotted in Venn diagrams to show EV distribution across cell lines. Note the often large fraction of EV negative for any marker.

We next characterized seven patient-derived xenograft (PDX) PDAC patient-derived cell lines (609, 950, 1275, 1309, 1319,1326, and 1473) that were originally developed at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) (43). These cell lines were analyzed for expression of KRASmut, P53mut, MUC1, and/or EGFR expression (table S1). Similar to the original manuscript (44), no pancreatic cell lines were positive for the specific prolyl-4 hydroxylated form of a-fibrinogen (FG) detected by this antibody, as it is thought that this is a posttranslational modification that occurs within inflammatory sites of the tumor microenvironment after EV secretion. Table S1 summarizes the background information of all PDAC cell lines, while table S2 provides a summary of biomarker presence in EV. Biomarker-positive EVs were detected in all cell lines positive for a given marker including KRASmut and P53mut. Similarly as in the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) panel, we found heterogeneity of expression. For example, in the KRASG12V-expressing cell line 1473, where it is estimated that each cell contains hundreds of thousands of KRASG12V proteins (45), 37% of EVs did not show expression of the mutant protein. This figure was considerably lower in the other PDX cell lines (Fig. 3B).

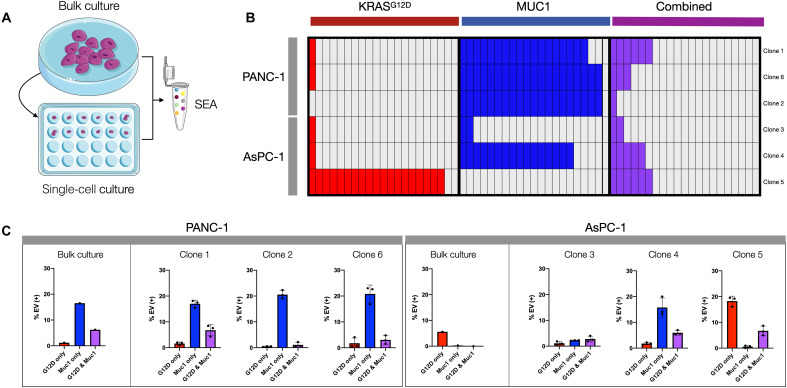

EV biomarkers can fluctuate in PDAC clonal populations

To further investigate EV biomarker heterogeneity, we performed clonal expansion experiments. In these experiments, we isolated single parental PDAC cells and grew them into individual clones from which EVs were then harvested and analyzed (Fig. 4A). For PANC-1 (KRASG12D/MUC1-positive), single cell–derived clones shed EVs that were representative of the parent cell line. Specifically, three tested clones retained high MUC1 expression and similar percentages of KRASG12D-positive EV (Fig. 4, B and C). In contradistinction, there was considerable heterogeneity in clonal expression with the KRASG12D/P53mut AsPC-1 cell line. Specifically, there was a ~5-fold increase in KRASG12D EV for clone 5, likely representative of a heterogeneous baseline population. This explanation is further suggested by the fact that there is a ~16-fold range in KRASG12D signal intensity among parental AsPC-1 cells. The AsPC-1 clones also showed induction of MUC1, with one clone exhibiting MUC1 positivity on ~20% of its EVs. Strong MUC1 induction has been previously shown for AsPC-1, and some laboratories report AsPC-1 as a MUC1+ cell line (46, 47). These data reinforce the idea that cell line heterogeneity, like tumor heterogeneity, can fluctuate temporally as selection pressures exert themselves and that this heterogeneity is reflected in EV. A takeaway from these findings is that sEVA is essential to capture low percentages of biomarker-positive EV, particularly when measurements are made in plasma and where nonmalignant EVs abound.

Fig. 4. Clonal EV analysis.

(A) A serial dilution was performed to obtain single-cell isolates from bulk cultures of PANC-1 and AsPC-1 cells. EVs were then collected from the medium of the resulting clonal expansion culture and compared to EVs from the parent cell lines. (B) The clone-derived EVs were analyzed for expression of KRASG12D and MUC1. Each box represents 1% of total EV staining for either marker alone or dual positive for both (purple). (C) Different PANC-1 clones appeared similar to each other and the parental line. Conversely, AsPC-1 clones showed variable expression of KRASG12D and MUC1 in EV. The EV formation rate was similar among clones, indicating that observed differences are due to differential clonal endogenous expression.

sEVA plasma sample analysis correlates with tumor mutational status

Being able to (co-)detect mutant onco/tumor suppressor proteins and other biomarkers in single EV, we next extended sEVA to clinical samples. Plasma, unlike cell culture medium, is a more complex mixture of potentially contaminating or confounding matrices, such as particles released upon platelet vesiculation (48), other lipid particles such as high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (49), as well as chemical anticoagulants such as EDTA, citrate, or heparin. Using a standardized input concentration of EV, all clinical samples were thresholded to obtain similar TFP-EV counts.

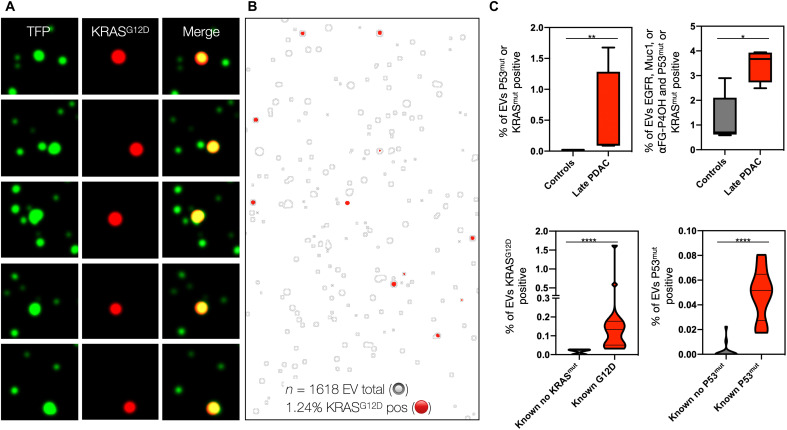

We initially tested the ability of sEVA to identify KRASG12D in a clinical plasma sample from a KRASG12D-positive late-stage pancreatic cancer patient (Fig. 5). Analyzing an FOV containing 1618 EVs (zoomed, Fig. 5, A and B) demonstrated that 1.24% of all EVs in circulation were positive for KRASG12D, but the frequency was much lower than observed in cell culture, presumably due to dilution effects. The KRASG12D signal was almost exclusively located on TFP-EVs rather than in secreted form (Fig. 5B). When the same sample was processed by bulk EV analysis, KRASmut became nondetectable against the background of >99% KRASmut-negative EV. To further validate sEVA in advanced PDAC, we processed additional samples (n = 2 stage III and n = 2 stage IV). We found that the KRASG12D and P53mut marker panel fully separated these four samples from healthy control samples (n = 5) and had, on average, greater than fivefold increased percentage of EV staining positive for the marker panel consisting of MUC1, EGFR, and αFG-P4OH (Fig. 5C). To establish the correlation between the EV onco/tumor suppressor protein analysis and next-generation sequencing (NGS) of surgical samples, we analyzed samples where matching information was available (i.e., KRASG12D, n = 13; KRAS wild type, n = 8; P53mut, n = 8; P53 wild type, n = 15). KRASG12D could be detected in this cohort with 100% specificity and sensitivity (P = 0.0002), and P53mut was detected at 100% specificity and 87.5% sensitivity (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. EV-based KRASG12D detection in clinical plasma sample.

(A) Representative images of a stage 4 PDAC, demonstrating superb colocalization of KRASG12D staining with TFP-labeled EV (green). Note that the bulk EV analysis of this sample failed to detect KRASmut. (B) Larger FOV of the same plasma sample. In this image, the TFP-ROI mask of all labeled EV is depicted by gray outlines, while the KRASG12D staining is shown in red. Of 1618 EVs imaged (only a fraction is shown for better visibility), 1.24% were positive for KRASG12D. (C) Group analysis of EV. The top graphs show quantitative analysis of late-stage PDAC samples (n = 4) against controls (n = 5). Note the high levels of EV positivity for KRASmut/P53mut as well as other PDAC biomarkers. The bottom graphs show the correlation of EV positivity for KRASmut/P53mut against the known mutational status derived from sequencing of surgical tumor samples (n = 24 samples). P values were indicated by significance: 0.0332 (*), 0.0021 (**), 0.0002 (***), and <0.0001 (****). Note the excellent correlation between EV analysis and NGS results. See text for details.

sEVA of plasma samples enables early cancer detection

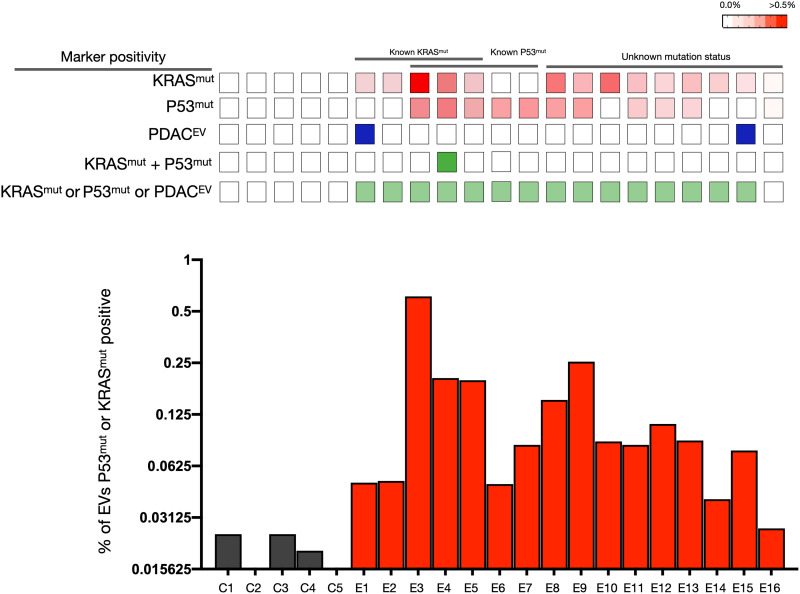

We next expanded the measurements to plasma samples from stage 1 pancreatic cancer patients (n = 16), although this is a rare clinical scenario as most PDACs will present at a later stage. Nevertheless, early PDAC detection has high clinical value in high-risk groups (50). We defined the threshold for EV staining as “positive” when a given biomarker stained >2× above an isotype control–labeled antibody. Plasma samples from healthy controls contained very low levels of biomarker-positive EV, although the number was not zero. Fewer than 0.03% of EV stained weakly positive for KRASmut or P53mut, and fewer than 1% stained weakly for EGFR, MUC1, or FG-P4OH (Fig. 6). For the clinical samples, all images analyzed passed quality control, and on average, several thousand vesicles were analyzed per sample (range, 3608 to 15,051; average > 5000).

Fig. 6. sEVA of clinical stage 1 PDAC cases.

Analysis of KRASmut and P53mut in EV of stage 1 PDAC plasma samples (n = 16) and in healthy controls (n = 5). Note that virtually all stage 1 PDAC plasma samples contained EV positive for either KRASmut (row 1) or P53mut (row 2). This marker positivity is higher than for PDACEV alone (row 3), as only two samples were above background. We also determined the fraction of EV double positive for both KRASmut and P53mut (row 4) in an effort to increase specificity, but this was a rare event. When all markers were combined, 15 of the 16 samples had positive EV (row 5). The bottom graph shows the fraction of KRASmut- or P53mut-positive EV in plasma samples.

When analyzing the stage 1 PDAC plasma samples, 15 of the 16 EV samples were positive for KRASmut and/or P53mut. All five samples with known KRAS mutation were positively identified, and another five samples with known P53 mutation were all positively identified. Only 1 of the 16 samples had dually positive EV staining for KRASmut and P53mut. For nine samples, the mutational status was not known, but five of these samples (56%) had EV positive for P53mut and seven samples (78%) had EV positive for KRASG12D, in line with the expected rate of these mutations in pancreatic cancer (8).

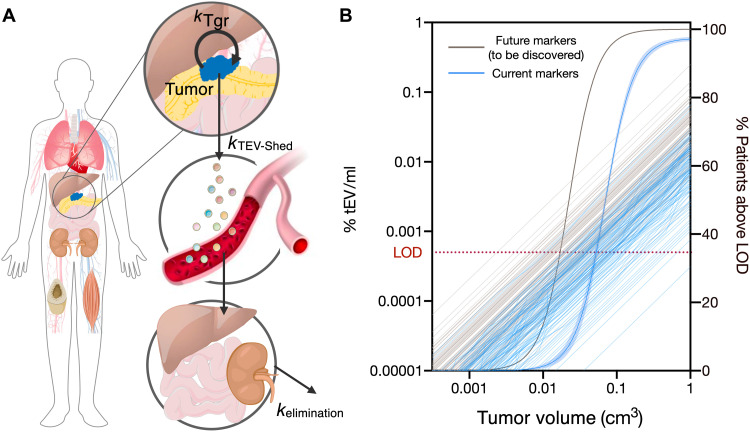

Modeling PDAC cancer detection thresholds

The ability to identify early forms of PDAC shows the clinical potential of sEVA. To address how early the current assay might be expected to detect pancreatic cancers, a modeling approach was necessary. We thus developed a framework model for tumor-EV shedding and distribution/elimination kinetics that was able to connect a tumor volume to expected tumor-EV concentrations in circulation (Fig. 7A). Two PDAC mouse models, KIC (51, 52) and KPC (51, 53), were included in the development of the model. Additional information used to inform our model simulations included (i) the EV shed rates observed from the patient-derived cell lines, (ii) the distribution of marker-positive EV observed for cancer cell lines, and (iii) biodistribution data of EV.

Fig. 7. Modeling of PDAC cancer detection using plasma sEVA.

(A) A model of tumor-EV production, distribution, and elimination (56) was combined with additional measurements of EV shed rates and the newly measured percent of EV positive for tumor-specific markers to (B) simulate current detection limits of PDAC tumors across a population of variable tEV shed rates and with variable percent coverage of tumor markers on the shed tEV. With the current set of markers shown in Fig. 6, ~70% of PDACs are estimated to become detectable at a tumor volume of 0.1 cm3. With additional robust markers, this detection level could approach 97%. LOD, limit of detection.

The ability to detect tEV in circulation is a combination of how many EVs are being shed by a tumor as well as the percentage of those EV positive for a given marker. Using the observed distributions in EV shed rate and EV marker coverage, 100 individuals were simulated (Fig. 7B). Interindividual variability around other parameters, such as EV distribution/elimination kinetics, was assumed constant across the population. In addition, the distribution simulated for marker coverage left open the very real possibility that some tumors are expected to be completely negative for any of the given markers; here, eight patients were simulated to be marker negative. Of all the model parameters, EV shed rate showed the greatest variability with a 100-fold difference between the highest and lowest shed rate tumors and thus is likely to represent the largest source of variability in detectable tumor sizes across a population.

Using the modeling approach, we estimate that ~92% of patients with a PDAC at a size of ~1 cm3 (~2 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm) will be detectable by sEVA. We also estimate that 68% of patients are likely to be diagnosable with pancreatic cancer at a tumor size of 0.1 cm3 with a specificity of at least ~80%. If in the future a panel of markers could be assembled to cover ~100% of all tumor-originating tEVs, the detection limit of PDAC could be as low as ~0.03 cm3 with similar specificity.

Superimposing the experimentally obtained patient data onto the modeling figure (fig. S8) shows the fraction of positive tEV in a plasma sample plotted against the tumor volume. Most data points fall into the upper right-hand corner of the graph, i.e., predicted to be diagnosable by sEVA. In some patients, the tumor volumes were higher (note logarithmic plot), but in others, they were lower. Irrespective of the specific data points, the experimental data generally agree with the model. Figure S9 shows additional data points in later-stage PDAC cases, where data from this study are plotted against data from studies with other late-stage cancers and result in an R2 of 0.96 between predicted and observed EV increases in different late-stage cancers.

DISCUSSION

Cancer cells release large quantities of EV, a finding that has prompted an exponential growth of this biomarker field. EVs are a heterogeneous group of vesicles varying in size, composition, intracellular biogenesis, and cell of origin (54). EV subpopulations are often divided into two groups: vesicles that bud directly from the plasma membrane (microvesicles) and vesicles that originate in endosomal compartments and are secreted by exocytosis (exosomes). Since exosomes and microvesicles partially overlap in size and composition, we use the general term “EV” when the specific cellular origin of the vesicle is unknown (55). A second useful classification is with respect to the compartment of origin (56): those derived directly from tumor cells (tEV) and those derived from host cells (hEV), which likely play different physiological roles.

Tumor cell–derived EVs not only can be useful diagnostic biomarkers but also have therapeutic implications. tEVs have been shown to modulate stromal cross-talk, cause immune evasion (57), prime metastatic sites, and lead to drug resistance, among others. To take full advantage of tEV, there is thus a need to better understand their kinetics during tumor development and therapy. Furthermore, there is a clear need to decipher why and how EV biogenesis ramps up in cancer cells, and what the specific avenues are for interventions (58). Here, we provide a much more granular insight into the composition and makeup of tEV in PDAC cell lines and in human plasma samples. Contrary to the common belief, we show at the single EV level that specific protein markers are generally low (e.g., 20 to 30% of EVs are positive for EGFR, whereas all parental cells are positive), heterogeneous, and uncommonly multiplexed unlike in parental cells. We furthermore show that tEVs carry mutated onco/tumor suppressor proteins and that these events can be detected by sEVA in plasma.

Mutated proteins in tumor cell–derived EV

KRAS mutation and/or hyperactivation can be found in virtually all PDACs (26). KRAS and other RAS proteins seem to be associated with increased tEV biogenesis. A recent study showed a role for Rab13 in sEV secretion from colorectal cancer cells expressing mutant KRAS (21). Mutant RAS has also been shown to up-regulate proteins involved in budding and vesicle exocytosis (59). Downstream targets of RAS have also been shown to control EV secretion from mammary tumor cells (60). We show that some KRAS mutations common in PDAC can be identified in circulating EV using sEVA. While ~40% of cell culture–derived EVs are positive for KRASmut in mutant cell lines (Fig. 3), the overall presence of KRASmut protein in patient-derived samples is much lower. This percentage in plasma is <0.1% of EV in early-stage cancers and ~1% in late-stage PDAC (Figs. 5 and 6). We assume that this is due to the heterogeneous makeup of PDAC, the fact that many EVs are shed by nontumor cells, and the stochastic process of internalizing proteins into EV from parental cells. Irrespective of the precise reason, the low numbers indicate that sEVA, such as sEVA developed here, is essential in early cancer diagnostics. It is much less likely that bulk EV analytical methods will be able to detect scant mutated proteins. Apart from a biomarker for early detection, we posit that EV KRAS analysis should also be useful in future clinical trials of patients receiving KRASG12C/KRASG12D inhibitors.

The tumor suppressor P53 is one of the most frequently mutated genes in human cancer and has been linked to EV release. Direct activation of P53 (61) or certain P53 target genes have been implicated in tEV secretion (62, 63). We show that P53mut is detectable in single EV and that multiplexed analysis can enhance the diagnostic accuracy of PDAC detection. Similar to KRAS, the P53 pathway is also subject to therapeutic development, providing a rationale for tEV monitoring.

There are a number of other mutated proteins in PDAC such as the oncogene GNAS or tumor suppressor genes CDKN2A and SMAD4 (8, 64). KRAS and GNAS are near-universal features of PDAC and PanIN but may also be present in low-grade precancerous lesions with little risk of malignant transformation. Additional driver genes may have potential utility in early detection of PDAC including RNF43, KLF4, PTEN, PIK3CA, and VHL (8). All of these could potentially be targeted, although reliable antibodies that detect all mutations are still awaiting development.

Multiplexing

It is theoretically possible to increase diagnostic specificity by assaying for and co-detecting multiple markers in EV. A number of multiplexing technologies have been developed, relying mostly on spectral fluorescence, image cycling, immunosequencing (65), and potentially others (66). Irrespective of the approach, vesicular real estate is somewhat limited. An EV has a 106 smaller volume compared to an entire cell. Protein packaging into or onto vesicles can thus be limited, while nuclear proteins are essentially absent in all vesicles. We believe that multiple marker analysis and multiplexing will still have particular value in two different scenarios. If mutated proteins are co-detected in the same vesicle, it can be assumed that this is virtually indicative of malignancy. Second, if different EVs with different mutated proteins coexist in a population, it raises the certainty by which the EV population arose from a heterogeneous cancer. In our cohort of 16 surgically proven stage 1 PDAC cases, we found biomarker-positive EV in 15 of the 16 cases (94%; Fig. 6).

Current challenges

In this work, we have overcome a number of technical challenges, while a few others still remain. We hope that future research can address these through further methodological advances. The quality of antibodies is essential in detecting rare and scant proteins. While amplification strategies can help, they also introduce potential errors in measurements. Furthermore, counting vesicular fluorescence events as positive requires setting a threshold. Such a threshold can be different for different antibodies and fluorochromes. Regardless of the approach, it is essential to analyze positive and negative control samples for each measurement. Another area for improvement is to optimize the small-volume measurements without losing vesicles during wash and purification steps. Microfluidic approaches could help, but they will need to be incorporated into glass devices [not poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) (PDMA)] to optimize the optical detection. Moving reagents and fluid through these devices without dislodging EV from the glass surface has proven challenging. Last, we have focused solely on plasma EV measurements. It is entirely possible to perform similar measurements in pancreatic duct fluid. This could help improve the dilution problem that occurs when tEVs are shed into circulation.

In summary, we show that sEVA is clinically feasible, powerful, and essential in detecting rare proteins in EV that can be indicative of disease. We expect that this approach could be combined with state-of-the-art whole-body imaging to improve the diagnostic accuracy of cancer detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

AsPC-1, CAPAN-2, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) (41). Patient-derived xenograft cell lines were developed in the laboratory of C. Fernandez at MGH (9, 43). All cells were characterized by mutational analysis, flow cytometry, and immunofluorescence (table S1).

Cell culture

AsPC-1, CAPAN-2, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Medium was changed every 1 to 2 days, and cells were passaged before confluency. Patient-derived cell lines were grown in 50:50 DMEM:F-12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Medium was also changed every other day, but cells were allowed to reach confluency. After each patient-derived cell line reached confluency, medium was collected every other day for 7 days (four collection points) for EV isolation. The total cells were counted for each plate along with noting the collection interval to calculate EV shed rate in units of day−1.

For clonal expansion experiments, a cross-diagonal dilution strategy on a 96-well plate to obtain on-diagonal single-cell wells was used as described (www.corning.com/catalog/cls/documents/protocols/Single_cell_cloning_protocol.pdf) for AsPC-1, CAPAN-2, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 cells. It is known that not all cell lines are capable of forming clones from a single cell. CAPAN-2 demonstrated this tendency with establishment of culture expansion predominantly in wells seeded with more than three cells. While MIA PaCa-2 established single-cell colonies, they quickly stopped expanding and appeared to enter contact-initiated senescence, passaging the colonies did not induce proliferation, and the scant EV material collected was insufficient for analysis. Both AsPC-1 and PANC-1 were capable of forming several single-cell colonies that after 6 weeks could be passaged to six-well plates and demonstrated easy to observe morphological differences. Six clones for each AsPC-1 and PANC-1 were grown on 10-cm dishes, and EVs were collected as described.

Clinical sample preparation

All specimens were collected from patients referred to MGH with abdominal complaints and who gave informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. A total of n = 25 patient samples were studied including healthy controls (n = 5), surgically proven stage 1 PDAC (n = 16), and biopsy-proven stage 2/4 PDAC (n = 4; table S3). Of the stage 1 PDAC, sequencing information was available in seven patients; the remaining patient samples predated routine sequencing, or sequencing costs were not covered by the health care provider. Blood collection was optimized for plasma EV analysis, and all samples were deidentified and analyzed in blinded fashion. Briefly, whole blood was collected in one 10-ml purple-top EDTA tube and was inverted 10 times to mix. Whole blood was stored upright at 4°C and processed within 1 hour of collection. To process blood for plasma isolation, the tube was centrifuged for 10 min at 400g (4°C). The plasma layer was collected in a 15-ml tube using a pipette so as not to disturb the buffy coat. Plasma was then centrifuged for 10 min at 1100g (4°C). The plasma was then aliquoted into 1-ml aliquots and stored at −80°C.

EV isolation

EVs were isolated from cell culture medium in a standard sequential approach. First, culture medium was spun at 500g for 5 min to remove cells and large cellular debris, and the supernatant was then spun at 2000g for 10 min for removal of apoptotic blebs and other micrometer-sized cellular material. The supernatant was then ultracentrifuged using a Beckman Coulter Optima L-90K ultracentrifuge with the SW 32 Ti rotor, spinning at 24,200 rpm for 70 min. Total cell culture medium per sample isolated in this manner was typically 30 to 100 ml. The EV pellets were decanted of supernatant and left inverted until all residual media could be quickly wicked off the centrifuge tube inner wall with a Kimwipe. EV pellets for each sample were then pooled by serially resuspending with 100 μl of 0.22-μm filtered phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Since ultracentrifugation can co-pellet nonvesicle material, concentrated samples from resuspension were further purified on Izon 70-nm qEV single columns following the manufacturer’s protocol. Clinical plasma samples stored at −80°C were thawed on ice, and 100 μl of each was spun at 10,000g for 20 min. The supernatant was carefully pipetted to avoid the loose pellet and was similarly isolated on an Izon 70-nm qEV single-size exclusion column. EV concentrations for cell culture samples obtained from the columns were typically of sufficient concentration as measured by the Qubit protein assay for downstream applications; however, this was not the case for clinical samples. For any samples of insufficient concentration (<50 ng/μl protein concentration), the 650-μl collection volume was concentrated on Nanosep Omega 300K molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) concentrators.

Pan-EV labeling with fluorescent TFP

Azido-dPEG-TFP ester obtained from Quanta Bio-design was reacted in house with different DBCO Alexa Fluor (AF) fluorophores (AF350, AF488, and AF647 were all validated) obtained from Click Chemistry Tools. Azido-dPEG12-TFP (1.1 molar equivalents) [dissolved in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to a stock concentration of 15 mg/ml] and Alexa Fluor DBCO dye (1 molar equivalent) (total 1 mg of dye obtained from the manufacturer dissolved in 50 μl of anhydrous DMSO) were combined for each reaction and incubated for 1 hour. The final coupling reaction concentrations thus varied by dye, ranging from 9 to 28 mM in the reaction mix. The copper-free Azido-DBCO click chemistry reaction was confirmed to have gone to completion and to have generated the correct product by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis. Dye-PEG12-TFP conjugates retain amine reactivity through the TFP-ester and were incubated with EV samples for general surface protein labeling. In most cases, 250 ng of EV was combined with 1 μl of Dye-PEG12-TFP. This ratio was scalable up to 1500 ng of EV input. The EV and Dye-PEG12-TFP reactions were brought to a final volume of 14 μl with filtered PBS and incubated in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes protected from light and under agitation using HulaMixer for 2 hours at room temperature. Excess Dye-PEG12-TFP was removed using Zeba Micro Spin Desalting Columns, 40K MWCO, 75 μl according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For EV samples >250 ng labeled with >1.0 μl of Dye-PEG-TFP, a second Zeba column purification to fully remove free dye signal was required.

While EV from cell culture could be reliably labeled and detected by AF350, this dye produced the dimmest signal and was sometimes insufficient for robust identification of EV derived from clinical samples. AF488 and AF647 worked well even for clinical samples for the conditions described above; however, for downstream detection of protein markers with 680-nm labeled antibodies, the AF647 TFP label showed bleed through into this channel at the exposure times necessary to detect lower antibody signals. Therefore, samples were labeled by AF488-TFP. Care was taken to avoid channel bleed through by optimizing filter choices and excitation light sources. A quantitation of channel bleed through and detection of fluorescent dyes are provided in fig. S3.

Antibody labeling of TFP-stained EV

Table S4 summarizes the antibodies used in this study, although a much larger panel of commercial antibodies was initially tested. Each antibody was (i) validated with recombinant protein (to determine the specificity of antibodies) and (ii) tested in cell lines (Western blotting and/or flow cytometry) and (iii) EVs were obtained from cell lines. Figure S6 shows (i) specificity of the antibodies used and (ii) generally good correlation between staining patterns in whole cells and cell-derived single EV.

EVs labeled with AF488-TFP were used for the cell line antibody panel. The optimized antibody panel included anti–pan-mutant P53 detection antibody (Abcam, ab247264) conjugated to AF555, anti-G12V KRAS (Cell Signaling, 14412BF, special carrier-free order), and anti-G12D (Genetex, GTX635362), both labeled with AF594 using the Alexa Fluor 594 Antibody Labeling Kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific, as well as anti-Prolyl 4-Hydroxylated FG-P4OH (Diagnocine, KC600), anti-MUC1 (BioLegend, 355602), and anti-EGFR (Abcam, Ab30) conjugated to AF680 using the Alexa Fluor 680 Antibody Labeling Kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific (table S3). The specificity of the mutant KRAS antibodies was determined by Western blotting (fig. S4) to assure that there was specificity as claimed by the vendors. The P53mut antibody (Abcam) does not recognize P53WT present in CAPAN-2 (fig. S5) but does recognize mutant P53 in BXPC3 (Y220C), MIA-PaCa-2 (R248W), and PANC-1 (R273H) cell lysate by Western blot analysis. However, there was not a strong signal for P53mut cell lines AsPC-1 (C135fs*35) or PSN-1 (K132Q) by Western blot. Clinical samples with known P53mut status included R213Ter, Y220C, Y163C, R196Ter, and R196H, all of which stained positively above levels in control plasma. Similar experiments were performed for all other antibodies against positive and negative control cell lines by flow cytometry and Western blot (fig. S6).

All samples were processed with the following optimized protocol: 14 μl of TFP-labeled EV was combined with 13 nM antibody and 0.001% Triton X-100 in 100-μl final volume of UltraBlock buffer (Bio-Rad, BUF033). Samples were then gently sonicated in a water bath for 5 min. The addition of 0.001% Triton X-100 and sonication steps were necessary for intravesicular targets such as P53mut since they reportedly permeabilize EV without disrupting vesicle integrity. These steps were not necessary to obtain efficient staining of surface markers such as MUC1 and EGFR. For speciation of oncoproteins in clinical samples, EVs were labeled with AF647-TFP and P53mut antibody was labeled with AF488, while the KRASG12D antibody was labeled with AF594. Samples were wrapped in foil to protect from photobleaching and were incubated on HulaMixer overnight at 4°C. In less optimal protocols (1 hour or less), benchtop incubation also provided strong staining of several markers but at marginally reduced sensitivity and specificity.

Sample preparation for sEVA

EV samples with fluorescently labeled antibodies were cleaned on the Izon 70-nm qEV single-size exclusion columns as described above, which allowed for substantial reduction in background noise coming from free fluorescent antibody that is retained on the column. The ~600- to 700-μl purified and labeled EVs were filtered by 0.2-μm polyvinylidene difluoride 17-mm syringe filters and then concentrated using Nanosep Omega 300K MWCO devices. In contrast to other MWCO filter devices, Nanosep Omega resulted in lower EV loss, perhaps due to less extensive fouling. While this loss observed for other MWCO devices could be largely reversed by stringent washing of the filter membrane, this appeared to introduce large fibrous artifacts into the sample. Samples were concentrated near to the dead-stop volume of the devices (~30 to 50 μl). The concentrated samples with initial EV input of 250 ng were then measured for total volume. A volume representing 100 ng of EV (typically ~12 to 20 μl, assuming no EV loss) was carefully pipetted onto a well of a 21-well polytetrafluoroethylene hydrophobically printed glass slide from Electron Microscopy Sciences (63429-04). Samples were incubated under humidified and light-protected conditions for 30 min by placing a wet Kimwipe under an opaque box along with the slide. After 30 min, most of the sample droplet was carefully pipetted off so that the surface tension of the remaining volume was level with the well depth but still sufficient volume to wet the entirety of the well area. A glass coverslip was then placed onto the slide, and images were promptly acquired.

Imaging and image processing

Images were acquired on an upright Olympus BX63 microscope using a 40× objective. EVs were brought into sharp focus with the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) filter set, allowing visualization of the TFP-labeled vesicles, and 4000-ms-long exposure was used for acquisition. Proper focusing is critical since lower-signal nano-sized EVs can be lost even with minor changes in z-plane settings. To ensure ideal focusing, the live image display was monitored by looking at the smaller/dimmer EVs and manually tweaking until a minimum pixel radius was observed. FOV selection was performed only on the FITC channel to minimize marker signal biases. Suitable FOVs were observed across the majority of each well, but in general, near-perimeter areas were avoided, as were areas of uneven background intensity (sometimes caused by small air bubbles, surface scratches, or crystallization patterning). After obtaining the total EV-TFP image, the samples were also imaged for 4000 ms with the Texas Red filter set for KRASmut and P53mut detection and 4000 ms with the CY5.5 filter set for EGFR, MUC1, and αFG-P4OH detection. EVs were thresholded according to the range of TFP labeling that varied across clinical samples by taking a ratio of the brightest (90th percentile pixels) to the background (10th percentile pixels). In this way, the number of TFP-identifiable EV per FOV, along with average EV size, and therefore total percent coverage of EV could be standardized across images, in line with the standardized amount of EV deposited per slide. Built-in particle analysis of particles larger than 5 pixels was then added into an ROI mask. This mask was applied to the background-subtracted Texas Red and CY5.5 images corresponding to that sample, and the signal intensities contained on TFP-EVs were measured. These measurements were then saved into comma delimited .CSV files to be analyzed. ROC analysis was used to maximize the sensitivity and specificity between positive and negative control samples. For cell lines, marker-positive cells and marker-negative cells were used to establish these thresholds. For clinical samples, healthy controls were used to establish a negative threshold. For a more detailed computational analysis protocol, see fig. S2.

Tumor volumes

The tumor volumes were determined by pathology and cross-sectional imaging findings. In brief, we used an ellipsoid approximation for cases where all three measurements were available from pathology reports; in cases where only one measurement was available, we used a spherical approximation. For stage I tumors smaller than 0.5 cm3, we assumed that the entire measurement was composed of tumor cells. For stage I tumors larger than 0.5 cm3, we approximated the tumor cell fraction by accounting for the amount of desmoplastic reaction (67) in specimen as per pathology report. For late-stage metastatic tumors, we used cross-sectional imaging to approximate the tumor extent and assumed that the tumor cell fraction was 50% of abnormal tissue (e.g., infiltrative tumors around the porta hepatis, portal vein, vena cava, lymph nodes, or liver metastases).

Statistics

Biomarker-positive EVs were summarized and expressed as the logarithm of the percent of total labeled EV per each clinical sample. Log-normalized distributions passed the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality, and statistically significant differences between groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) assuming a normal distribution. Each marker set was compared to healthy controls for both early and late PDAC, and multiple comparisons were corrected by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test. Multiplicity adjusted P values were indicated by significance: 0.0332 (*), 0.0021 (**), 0.0002 (***), <0.0001 (****). To determine the threshold of stage 1 PDAC detection, a ROC was performed with the lowest-bias cross-validation approach of leave-pair-out. The results are summarized in fig. S7. All statistics were performed in GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Quintana for performing LC-MS experiments on TFP reagents and H. Lee for helpful discussions.

Funding: This work was supported, in part, by the following NIH grants: R01CA237332 R01CA204019, R21CA236561, and P01CA069246. S.F. was supported by T32CA079443.

Author contributions: Design: S.F., K.S.Y., and R.W. Experiments: S.F. and K.S.Y. PDX cell lines: A.S.L. and C.F.d.C. Clinical samples: C.F.d.C. and K.S.Y. Data analysis: all authors. Writing: all authors

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Modeling and Simulation

Figs. S1 to S11

Tables S1 to S6

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Rahib L., Smith B. D., Aizenberg R., Rosenzweig A. B., Fleshman J. M., Matrisian L. M., Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 74, 2913–2921 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrone C. R., Marchegiani G., Hong T. S., Ryan D. P., Deshpande V., McDonnell E. I., Sabbatino F., Santos D. D., Allen J. N., Blaszkowsky L. S., Clark J. W., Faris J. E., Goyal L., Kwak E. L., Murphy J. E., Ting D. T., Wo J. Y., Zhu A. X., Warshaw A. L., Lillemoe K. D., Fernández-del Castillo C., Radiological and surgical implications of neoadjuvant treatment with FOLFIRINOX for locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann. Surg. 261, 12–17 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattox A. K., Bettegowda C., Zhou S., Papadopoulos N., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Applications of liquid biopsies for cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaay1984 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krantz B. A., O’Reilly E. M., Biomarker-based therapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: An emerging reality. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 2241–2250 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bettegowda C., Sausen M., Leary R. J., Kinde I., Wang Y., Agrawal N., Bartlett B. R., Wang H., Luber B., Alani R. M., Antonarakis E. S., Azad N. S., Bardelli A., Brem H., Cameron J. L., Lee C. C., Fecher L. A., Gallia G. L., Gibbs P., Le D., Giuntoli R. L., Goggins M., Hogarty M. D., Holdhoff M., Hong S. M., Jiao Y., Juhl H. H., Kim J. J., Siravegna G., Laheru D. A., Lauricella C., Lim M., Lipson E. J., Marie S. K., Netto G. J., Oliner K. S., Olivi A., Olsson L., Riggins G. J., Sartore-Bianchi A., Schmidt K., Shih L. M., Oba-Shinjo S. M., Siena S., Theodorescu D., Tie J., Harkins T. T., Veronese S., Wang T. L., Weingart J. D., Wolfgang C. L., Wood L. D., Xing D., Hruban R. H., Wu J., Allen P. J., Schmidt C. M., Choti M. A., Velculescu V. E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Papadopoulos N., Diaz L. A., Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 224ra24 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen J. D., Li L., Wang Y., Thoburn C., Afsari B., Danilova L., Douville C., Javed A. A., Wong F., Mattox A., Hruban R. H., Wolfgang C. L., Goggins M. G., Molin M. D., Wang T. L., Roden R., Klein A. P., Ptak J., Dobbyn L., Schaefer J., Silliman N., Popoli M., Vogelstein J. T., Browne J. D., Schoen R. E., Brand R. E., Tie J., Gibbs P., Wong H. L., Mansfield A. S., Jen J., Hanash S. M., Falconi M., Allen P. J., Zhou S., Bettegowda C., Diaz L. A., Tomasetti C., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Lennon A. M., Papadopoulos N., Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 359, 926–930 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee B., Lipton L., Cohen J., Tie J., Javed A. A., Li L., Goldstein D., Burge M., Cooray P., Nagrial A., Tebbutt N. C., Thomson B., Nikfarjam M., Harris M., Haydon A., Lawrence B., Tai D. W. M., Simons K., Lennon A. M., Wolfgang C. L., Tomasetti C., Papadopoulos N., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Gibbs P., Circulating tumor DNA as a potential marker of adjuvant chemotherapy benefit following surgery for localized pancreatic cancer. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1472–1478 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singhi A. D., Wood L. D., Early detection of pancreatic cancer using DNA-based molecular approaches. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 457–468 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang K. S., Im H., Hong S., Pergolini I., Del Castillo A. F., Wang R., Clardy S., Huang C. H., Pille C., Ferrone S., Yang R., Castro C. M., Lee H., Del Castillo C. F., Weissleder R., Multiparametric plasma EV profiling facilitates diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaal3226 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martini V., Timme-Bronsert S., Fichtner-Feigl S., Hoeppner J., Kulemann B., Circulating tumor cells in pancreatic cancer: Current perspectives. Cancers 11, 1659 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan C., Clish C. B., Wu C., Mayers J. R., Kraft P., Townsend M. K., Zhang M., Tworoger S. S., Bao Y., Qian Z. R., Rubinson D. A., Ng K., Giovannucci E. L., Ogino S., Stampfer M. J., Gaziano J. M., Ma J., Sesso H. D., Anderson G. L., Cochrane B. B., Manson J. E., Torrence M. E., Kimmelman A. C., Amundadottir L. T., Vander Heiden M. G., Fuchs C. S., Wolpin B. M., Circulating metabolites and survival among patients with pancreatic cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 108, djv409 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shao H., Im H., Castro C. M., Breakefield X., Weissleder R., Lee H., New technologies for analysis of extracellular vesicles. Chem. Rev. 118, 1917–1950 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Im H., Shao H., Park Y. I., Peterson V. M., Castro C. M., Weissleder R., Lee H., Label-free detection and molecular profiling of exosomes with a nano-plasmonic sensor. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 490–495 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issadore D., Min C., Liong M., Chung J., Weissleder R., Lee H., Miniature magnetic resonance system for point-of-care diagnostics. Lab Chip 11, 2282–2287 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H., Sun E., Ham D., Weissleder R., Chip-NMR biosensor for detection and molecular analysis of cells. Nat. Med. 14, 869–874 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arab T., Mallick E. R., Huang Y., Dong L., Liao Z., Zhao Z., Gololobova O., Smith B., Haughey N. J., Pienta K. J., Slusher B. S., Tarwater P. M., Tosar J. P., Zivkovic A. M., Vreeland W. N., Paulaitis M. E., Witwer K. W., Characterization of extracellular vesicles and synthetic nanoparticles with four orthogonal single-particle analysis platforms. J. Extracell Vesicles 10, e12079 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee K., Fraser K., Ghaddar B., Yang K., Kim E., Balaj L., Chiocca A., Breakefield X. O., Lee H., Weissleder R., Multiplexed profiling of single extracellular vesicles. ACS Nano 12, 494–503 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melo S. A., Luecke L. B., Kahlert C., Fernandez A. F., Gammon S. T., Kaye J., LeBleu V. S., Mittendorf E. A., Weitz J., Rahbari N., Reissfelder C., Pilarsky C., Fraga M. F., Piwnica-Worms D., Kalluri R., Glypican-1 identifies cancer exosomes and detects early pancreatic cancer. Nature 523, 177–182 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capello M., Bantis L. E., Scelo G., Zhao Y., Li P., Dhillon D. S., Patel N. J., Kundnani D. L., Wang H., Abbruzzese J. L., Maitra A., Tempero M. A., Brand R., Firpo M. A., Mulvihill S. J., Katz M. H., Brennan P., Feng Z., Taguchi A., Hanash S. M., Sequential validation of blood-based protein biomarker candidates for early-stage pancreatic cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 109, djw266 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J., Bamlet W. R., Oberg A. L., Chaffee K. G., Donahue G., Cao X. J., Chari S., Garcia B. A., Petersen G. M., Zaret K. S., Detection of early pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with thrombospondin-2 and CA19–9 blood markers. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaah5583 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinger S. A., Abner J. J., Franklin J. L., Jeppesen D. K., Coffey R. J., Patton J. G., Rab13 regulates sEV secretion in mutant KRAS colorectal cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 10, 15804 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim K. H., O’Hayer K., Adam S. J., Kendall S. D., Campbell P. M., Der C. J., Counter C. M., Divergent roles for RalA and RalB in malignant growth of human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Curr. Biol. 16, 2385–2394 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim K. H., Baines A. T., Fiordalisi J. J., Shipitsin M., Feig L. A., Cox A. D., Der C. J., Counter C. M., Activation of RalA is critical for Ras-induced tumorigenesis of human cells. Cancer Cell 7, 533–545 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang S., Wang C., Ma B., Xu M., Xu S., Liu J., Tian Y., Fu Y., Luo Y., Mutant p53 drives cancer metastasis via RCP-mediated Hsp90α secretion. Cell Rep. 32, 107879 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ying H., Dey P., Yao W., Kimmelman A. C., Draetta G. F., Maitra A., DePinho R. A., Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 30, 355–385 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waters A. M., Der C. J., KRAS: The critical driver and therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 8, a031435 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kowal J., Arras G., Colombo M., Jouve M., Morath J. P., Primdal-Bengtson B., Dingli F., Loew D., Tkach M., Théry C., Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E968–E977 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Springer S., Wang Y., Molin M. D., Masica D. L., Jiao Y., Kinde I., Blackford A., Raman S. P., Wolfgang C. L., Tomita T., Niknafs N., Douville C., Ptak J., Dobbyn L., Allen P. J., Klimstra D. S., Schattner M. A., Schmidt C. M., Yip-Schneider M., Cummings O. W., Brand R. E., Zeh H. J., Singhi A. D., Scarpa A., Salvia R., Malleo G., Zamboni G., Falconi M., Jang J. Y., Kim S. W., Kwon W., Hong S. M., Song K. B., Kim S. C., Swan N., Murphy J., Geoghegan J., Brugge W., Castillo C. F.-D., Mino-Kenudson M., Schulick R., Edil B. H., Adsay V., Paulino J., van Hooft J., Yachida S., Nara S., Hiraoka N., Yamao K., Hijioka S., van der Merwe S., Goggins M., Canto M. I., Ahuja N., Hirose K., Makary M., Weiss M. J., Cameron J., Pittman M., Eshleman J. R., Diaz L. A., Papadopoulos N., Kinzler K. W., Karchin R., Hruban R. H., Vogelstein B., Lennon A. M., A combination of molecular markers and clinical features improve the classification of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology 149, 1501–1510 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Integrated genomic characterization of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 32, 185–203.e13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koshikawa N., Minegishi T., Kiyokawa H., Seiki M., Specific detection of soluble EphA2 fragments in blood as a new biomarker for pancreatic cancer. Cell Death Dis. 8, e3134 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gambini L., Salem A. F., Udompholkul P., Tan X. F., Baggio C., Shah N., Aronson A., Song J., Pellecchia M., Structure-based design of novel EphA2 agonistic agents with nanomolar affinity in vitro and in cell. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 2633–2644 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boeck S., Wittwer C., Heinemann V., Haas M., Kern C., Stieber P., Nagel D., Holdenrieder S., Cytokeratin 19-fragments (CYFRA 21-1) as a novel serum biomarker for response and survival in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 108, 1684–1694 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bausch D., Mino-Kenudson M., Fernández-Del Castillo C., Warshaw A. L., Kelly K. A., Thayer S. P., Plectin-1 is a biomarker of malignant pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 13, 1948–1954; discussion 1954 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen R., Yi E. C., Donohoe S., Pan S., Eng J., Cooke K., Crispin D. A., Lane Z., Goodlett D. R., Bronner M. P., Aebersold R., Brentnall T. A., Pancreatic cancer proteome: The proteins that underlie invasion, metastasis, and immunologic escape. Gastroenterology 129, 1187–1197 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki K., Watanabe A., Araki K., Yokobori T., Harimoto N., Gantumur D., Hagiwara K., Yamanaka T., Ishii N., Tsukagoshi M., Igarashi T., Kubo N., Gombodorj N., Nishiyama M., Hosouchi Y., Kuwano H., Shirabe K., High STMN1 expression is associated with tumor differentiation and metastasis in clinical patients with pancreatic cancer. Anticancer Res. 38, 939–944 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keklikoglou I., Cianciaruso C., Güç E., Squadrito M. L., Spring L. M., Tazzyman S., Lambein L., Poissonnier A., Ferraro G. B., Baer C., Cassará A., Guichard A., Iruela-Arispe M. L., Lewis C. E., Coussens L. M., Bardia A., Jain R. K., Pollard J. W., De Palma M., Chemotherapy elicits pro-metastatic extracellular vesicles in breast cancer models. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 190–202 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaur S., Smith L. M., Patel A., Menning M., Watley D. C., Malik S. S., Krishn S. R., Mallya K., Aithal A., Sasson A. R., Johansson S. L., Jain M., Singh S., Guha S., Are C., Raimondo M., Hollingsworth M. A., Brand R. E., Batra S. K., A combination of MUC5AC and CA19-9 improves the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer: A multicenter study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112, 172–183 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Das K. K., Geng X., Brown J. W., Morales-Oyarvide V., Huynh T., Pergolini I., Pitman M. B., Ferrone C., Al Efishat M., Haviland D., Thompson E., Wolfgang C., Lennon A. M., Allen P., Lillemoe K. D., Fields R. C., Hawkins W. G., Liu J., Castillo C. F., Das K. M., Mino-Kenudson M., Cross validation of the monoclonal antibody Das-1 in identification of high-risk mucinous pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastroenterology 157, 720–730.e2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das K. K., Xiao H., Geng X., Fernandez-Del-Castillo C., Morales-Oyarvide V., Daglilar E., Forcione D. G., Bounds B. C., Brugge W. R., Pitman M. B., Mino-Kenudson M., Das K. M., mAb Das-1 is specific for high-risk and malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). Gut 63, 1626–1634 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang K. S., Ciprani D., O’Shea A., Liss A., Yang R., Fletcher-Mercaldo S., Mino-Kenudson M., Fernández-Del Castillo C., Weissleder R., Extracellular vesicle analysis allows for identification of invasive IPMN. Gastroenterology 160, 1345–1358.e11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deer E. L., González-Hernández J., Coursen J. D., Shea J. E., Ngatia J., Scaife C. L., Firpo M. A., Mulvihill S. J., Phenotype and genotype of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Pancreas 39, 425–435 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hessvik N. P., Llorente A., Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75, 193–208 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pergolini I., Morales-Oyarvide V., Mino-Kenudson M., Honselmann K. C., Rosenbaum M. W., Nahar S., Kem M., Ferrone C. R., Lillemoe K. D., Bardeesy N., Ryan D. P., Thayer S. P., Warshaw A. L., Fernández-Del Castillo C., Liss A. S., Tumor engraftment in patient-derived xenografts of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is associated with adverse clinicopathological features and poor survival. PLOS ONE 12, e0182855 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ono M., Matsubara J., Honda K., Sakuma T., Hashiguchi T., Nose H., Nakamori S., Okusaka T., Kosuge T., Sata N., Nagai H., Ioka T., Tanaka S., Tsuchida A., Aoki T., Shimahara M., Yasunami Y., Itoi T., Moriyasu F., Negishi A., Kuwabara H., Shoji A., Hirohashi S., Yamada T., Prolyl 4-hydroxylation of alpha-fibrinogen: A novel protein modification revealed by plasma proteomics. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29041–29049 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mageean C. J., Griffiths J. R., Smith D. L., Clague M. J., Prior I. A., Absolute quantification of endogenous Ras isoform abundance. PLOS ONE 10, e0142674 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kitamoto S., Yokoyama S., Higashi M., Yamada N., Takao S., Yonezawa S., MUC1 enhances hypoxia-driven angiogenesis through the regulation of multiple proangiogenic factors. Oncogene 32, 4614–4621 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang H. L., Wu H. Y., Chu P. C., Lai I. L., Huang P. H., Kulp S. K., Pan S. L., Teng C. M., Chen C. S., Role of integrin-linked kinase in regulating the protein stability of the MUC1-C oncoprotein in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogenesis 6, e359 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palviainen M., Saraswat M., Varga Z., Kitka D., Neuvonen M., Puhka M., Joenväärä S., Renkonen R., Nieuwland R., Takatalo M., Siljander P. R. M., Extracellular vesicles from human plasma and serum are carriers of extravesicular cargo-Implications for biomarker discovery. PLOS ONE 15, e0236439 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van Deun J., Jo A., Li H., Lin H. Y., Weissleder R., Im H., Lee H., Integrated dual-mode chromatography to enrich extracellular vesicles from plasma. Adv. Biosyst. 4, e1900310 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goggins M., Overbeek K. A., Brand R., Syngal S., Del Chiaro M., Bartsch D. K., Bassi C., Carrato A., Farrell J., Fishman E. K., Fockens P., Gress T. M., van Hooft J. E., Hruban R. H., Kastrinos F., Klein A., Lennon A. M., Lucas A., Park W., Rustgi A., Simeone D., Stoffel E., Vasen H. F. A., Cahen D. L., Canto M. I., Bruno M.; International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) consortium , Management of patients with increased risk for familial pancreatic cancer: Updated recommendations from the International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium. Gut 69, 7–17 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma R., Huang X., Brekken R. A., Schroit A. J., Detection of phosphatidylserine-positive exosomes for the diagnosis of early-stage malignancies. Br. J. Cancer 117, 545–552 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cruz V. H., Arner E. N., Du W., Bremauntz A. E., Brekken R. A., Axl-mediated activation of TBK1 drives epithelial plasticity in pancreatic cancer. JCI Insight 5, 126117 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Olive K. P., Jacobetz M. A., Davidson C. J., Gopinathan A., McIntyre D., Honess D., Madhu B., Goldgraben M. A., Caldwell M. E., Allard D., Frese K. K., Denicola G., Feig C., Combs C., Winter S. P., Ireland-Zecchini H., Reichelt S., Howat W. J., Chang A., Dhara M., Wang L., Rückert F., Grützmann R., Pilarsky C., Izeradjene K., Hingorani S. R., Huang P., Davies S. E., Plunkett W., Egorin M., Hruban R. H., Whitebread N., McGovern K., Adams J., Iacobuzio-Donahue C., Griffiths J., Tuveson D. A., Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science 324, 1457–1461 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaborowski M. P., Balaj L., Breakefield X. O., Lai C. P., Extracellular vesicles: Composition, biological relevance, and methods of study. Bioscience 65, 783–797 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Théry C., Witwer K. W., Aikawa E., Alcaraz M. J., Anderson J. D., Andriantsitohaina R., Antoniou A., Arab T., Archer F., Atkin-Smith G. K., Ayre D. C., Bach J. M., Bachurski D., Baharvand H., Balaj L., Baldacchino S., Bauer N. N., Baxter A. A., Bebawy M., Beckham C., Zavec A. B., Benmoussa A., Berardi A. C., Bergese P., Bielska E., Blenkiron C., Bobis-Wozowicz S., Boilard E., Boireau W., Bongiovanni A., Borràs F. E., Bosch S., Boulanger C. M., Breakefield X., Breglio A. M., Brennan M. Á., Brigstock D. R., Brisson A., Broekman M. L., Bromberg J. F., Bryl-Górecka P., Buch S., Buck A. H., Burger D., Busatto S., Buschmann D., Bussolati B., Buzás E. I., Byrd J. B., Camussi G., Carter D. R., Caruso S., Chamley L. W., Chang Y. T., Chen C., Chen S., Cheng L., Chin A. R., Clayton A., Clerici S. P., Cocks A., Cocucci E., Coffey R. J., Cordeiro-da-Silva A., Couch Y., Coumans F. A., Coyle B., Crescitelli R., Criado M. F., D’Souza-Schorey C., Das S., Chaudhuri A. D., de Candia P., De Santana E. F., De Wever O., Del Portillo H. A., Demaret T., Deville S., Devitt A., Dhondt B., Di Vizio D., Dieterich L. C., Dolo V., Rubio A. P. D., Dominici M., Dourado M. R., Driedonks T. A., Duarte F. V., Duncan H. M., Eichenberger R. M., Ekström K., El Andaloussi S., Elie-Caille C., Erdbrügger U., Falcón-Pérez J. M., Fatima F., Fish J. E., Flores-Bellver M., Försönits A., Frelet-Barrand A., Fricke F., Fuhrmann G., Gabrielsson S., Gámez-Valero A., Gardiner C., Gärtner K., Gaudin R., Gho Y. S., Giebel B., Gilbert C., Gimona M., Giusti I., Goberdhan D. C., Görgens A., Gorski S. M., Greening D. W., Gross J. C., Gualerzi A., Gupta G. N., Gustafson D., Handberg A., Haraszti R. A., Harrison P., Hegyesi H., Hendrix A., Hill A. F., Hochberg F. H., Hoffmann K. F., Holder B., Holthofer H., Hosseinkhani B., Hu G., Huang Y., Huber V., Hunt S., Ibrahim A. G., Ikezu T., Inal J. M., Isin M., Ivanova A., Jackson H. K., Jacobsen S., Jay S. M., Jayachandran M., Jenster G., Jiang L., Johnson S. M., Jones J. C., Jong A., Jovanovic-Talisman T., Jung S., Kalluri R., Kano S. I., Kaur S., Kawamura Y., Keller E. T., Khamari D., Khomyakova E., Khvorova A., Kierulf P., Kim K. P., Kislinger T., Klingeborn M., Klinke D. J., Kornek M., Kosanović M. M., Kovács Á. F., Krämer-Albers E. M., Krasemann S., Krause M., Kurochkin I. V., Kusuma G. D., Kuypers S., Laitinen S., Langevin S. M., Languino L. R., Lannigan J., Lässer C., Laurent L. C., Lavieu G., Lázaro-Ibáñez E., Le Lay S., Lee M. S., Lee Y. X. F., Lemos D. S., Lenassi M., Leszczynska A., Li I. T., Liao K., Libregts S. F., Ligeti E., Lim R., Lim S. K., Linē A., Linnemannstöns K., Llorente A., Lombard C. A., Lorenowicz M. J., Lörincz Á. M., Lötvall J., Lovett J., Lowry M. C., Loyer X., Lu Q., Lukomska B., Lunavat T. R., Maas S. L., Malhi H., Marcilla A., Mariani J., Mariscal J., Martens-Uzunova E. S., Martin-Jaular L., Martinez M. C., Martins V. R., Mathieu M., Mathivanan S., Maugeri M., McGinnis L. K., McVey M. J., Meckes D. G., Meehan K. L., Mertens I., Minciacchi V. R., Möller A., Jørgensen M. M., Morales-Kastresana A., Morhayim J., Mullier F., Muraca M., Musante L., Mussack V., Muth D. C., Myburgh K. H., Najrana T., Nawaz M., Nazarenko I., Nejsum P., Neri C., Neri T., Nieuwland R., Nimrichter L., Nolan J. P., Nolte-‘t Hoen E. N., Hooten N. N., O’Driscoll L., O’Grady T., O’Loghlen A., Ochiya T., Olivier M., Ortiz A., Ortiz L. A., Osteikoetxea X., Østergaard O., Ostrowski M., Park J., Pegtel D. M., Peinado H., Perut F., Pfaffl M. W., Phinney D. G., Pieters B. C., Pink R. C., Pisetsky D. S., von Strandmann E. P., Polakovicova I., Poon I. K., Powell B. H., Prada I., Pulliam L., Quesenberry P., Radeghieri A., Raffai R. L., Raimondo S., Rak J., Ramirez M. I., Raposo G., Rayyan M. S., Regev-Rudzki N., Ricklefs F. L., Robbins P. D., Roberts D. D., Rodrigues S. C., Rohde E., Rome S., Rouschop K. M., Rughetti A., Russell A. E., Saá P., Sahoo S., Salas-Huenuleo E., Sánchez C., Saugstad J. A., Saul M. J., Schiffelers R. M., Schneider R., Schøyen T. H., Scott A., Shahaj E., Sharma S., Shatnyeva O., Shekari F., Shelke G. V., Shetty A. K., Shiba K., Siljander P. R., Silva A. M., Skowronek A., Snyder O. L., Soares R. P., Sódar B. W., Soekmadji C., Sotillo J., Stahl P. D., Stoorvogel W., Stott S. L., Strasser E. F., Swift S., Tahara H., Tewari M., Timms K., Tiwari S., Tixeira R., Tkach M., Toh W. S., Tomasini R., Torrecilhas A. C., Tosar J. P., Toxavidis V., Urbanelli L., Vader P., van Balkom B. W., van der Grein S. G., Van Deun J., van Herwijnen M. J., Van Keuren-Jensen K., van Niel G., van Royen M. E., van Wijnen A. J., Vasconcelos M. H., Vechetti I. J., Veit T. D., Vella L. J., Velot É., Verweij F. J., Vestad B., Viñas J. L., Visnovitz T., Vukman K. V., Wahlgren J., Watson D. C., Wauben M. H., Weaver A., Webber J. P., Weber V., Wehman A. M., Weiss D. J., Welsh J. A., Wendt S., Wheelock A. M., Wiener Z., Witte L., Wolfram J., Xagorari A., Xander P., Xu J., Yan X., Yáñez-Mó M., Yin H., Yuana Y., Zappulli V., Zarubova J., Žėkas V., Zhang J. Y., Zhao Z., Zheng L., Zheutlin A. R., Zickler A. M., Zimmermann P., Zivkovic A. M., Zocco D., Zuba-Surma E. K., Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 7, 1535750 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferguson S., Weissleder R., Modeling EV kinetics for use in early cancer detection. Adv. Biosyst. 4, e1900305 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pucci F., Garris C., Lai C. P., Newton A., Pfirschke C., Engblom C., Alvarez D., Sprachman M., Evavold C., Magnuson A., von Andrian U. H., Glatz K., Breakefield X. O., Mempel T. R., Weissleder R., Pittet M. J., SCS macrophages suppress melanoma by restricting tumor-derived vesicle-B cell interactions. Science 352, 242–246 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]