Abstract

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) have great potential for disease modeling, drug discovery, and regenerative medicine as they can differentiate into many different functional cell types via directed differentiation. However, the application of disease modeling is limited due to a time-consuming and labor-intensive process of introducing known pathogenic mutations into hPSCs. Base editing is a newly developed technology that enables the facile introduction of point mutations into specific loci within the genome of living cells without unwanted genome injured. We describe an optimized stepwise protocol to introduce disease-specific mutations of long QT syndrome (LQTs) into hPSCs. We highlight technical issues, especially those associated with introducing a point mutation to obtain isogenic hPSCs without inserting any resistance cassette and reproducible cardiomyocyte differentiation. Based on the protocol, we succeeded in getting hPSCs carrying LQTs pathogenic mutation with excellent efficiency (31.7% of heterozygous clones, 9.1% of homozygous clones) in less than 20 days. In addition, we also provide protocols to analyze electrophysiological of hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes using multi-electrode arrays. This protocol is also applicable to introduce other disease-specific mutations into hPSCs.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Base editing, hPSCs, Point mutation, Disease model, LQT

Introduction

Human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and the closely related human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), are characterized by self-renewal and can differentiate into a huge number of different functional cell types via directed differentiation [1]. The ability to proliferate indefinitely allows large number of differentiated derived cells to be obtained in a short period. It plays a vital role in regenerative medicine. The ability to directionally differentiate into somatic cells allows stem cells to play an essential role in disease models [2], drug screening [3], cell development [4], and cell fate choice [5]. Patient tissue-derived iPSCs [6], which are then differentiated into cardiac [7], neural [8], endothelial [9], and other cells, are widely used in disease modeling. Using patient-derived iPSCs, we can study many genetic diseases, such as long QT syndrome [10], Brugada syndrome [11], hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [12], etc. However, some diseases are not genetically inherited [13], and such diseases-derived iPSCs are likely to be non-phenotype observed. For example, some diseases in which methylation is involved in regulation may be lost during reprogramming [14]. In addition, there is a lack of ideal control when compared with patient-derived iPSCs. Researchers usually select healthy people of the same family [15] or unrelated healthy people [16] as control. This may considerably reduce the reliability of the studies, as the genetic backgrounds of these individual are different. Moreover, the reprogramming process from tissue cells to iPSCs is time-consuming [17]. Using gene-editing technology to introduce disease mutations in hPSCs and using unedited hPSCs as control can be a perfect solution to overcome these limitations.

Base editing technique is an evolution of the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR) system, introducing point mutations without requiring DNA double-strand breaks or donor templates [18]. Under the guidance of sgRNA, the catalytically impaired Cas9 protein fused with a single-stranded DNA deaminase enzyme is guided to the target sequence and then substituted the bases [19]. Because it consists of inactivated Cas9, which undergoes point substitution without producing double-stranded DNA breaks, the non-specific activity is greatly reduced and is considered to be the safest. Three main classes of base editors have been developed to date: cytosine base editors (CBEs), which catalyze the conversion of C•G base pairs to T•A base pairs [20]; and adenine base editors (ABEs), which catalyze A•T-to-G•C conversions [21]; Glycosylase base editors (GBEs), which catalyze the conversion of C•G base pairs to A•G (in bacteria) [22] and catalyze the conversion of C•G base pairs to G•A (in mammalian cells) [23]. These techniques could theoretically be used to correct or introduce human pathogenic SNPs [24]. Conventional base editing techniques require two vectors. One expresses catalytically impaired Cas9 protein fused with a single-stranded DNA deaminase enzyme, the other expressing sgRNA. Gene editing is only possible happened if two plasmids enter a cell at the same time. However, although the efficiency of gene editing is high, the low efficiency of hPSCs transfection is a huge obstacle [25]. Therefore, the introduction of disease mutations in hPSCs is a very time-consuming and challenging work, but it is easier and shorter than reprogramming.

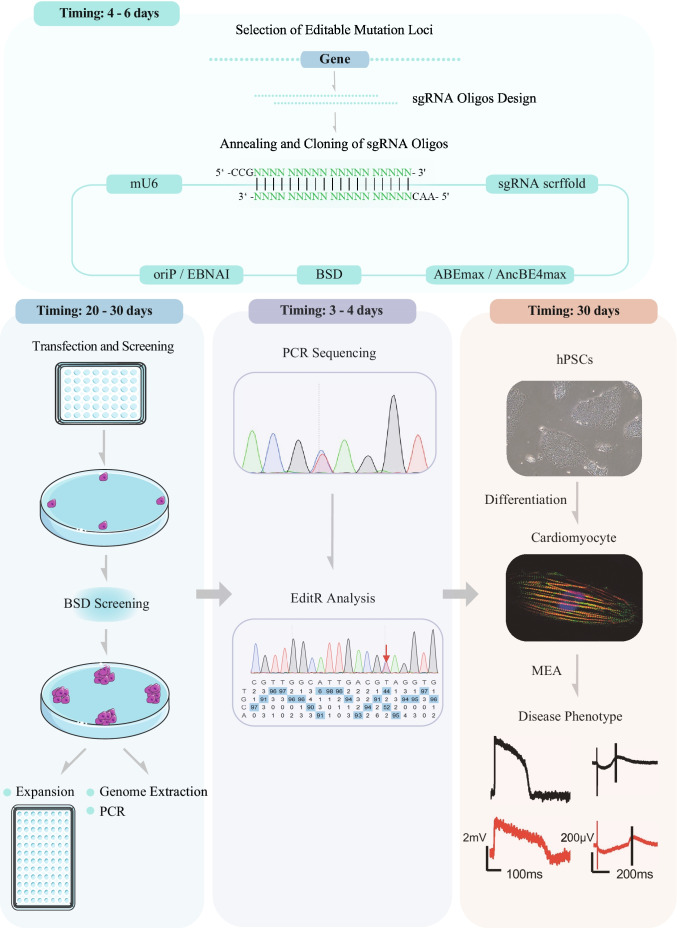

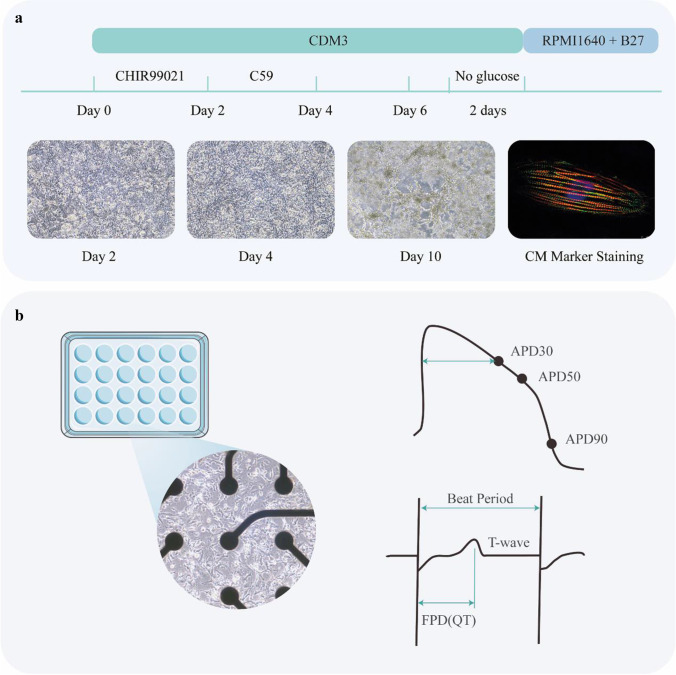

In our previous work [26], inactivated Cas9, a single guide RNA (sgRNA) with an adenine base editor (ABE) or a cytosine base editor (CBE), were all co-expressed in one episomal vector (refer to epi-BE). The episomal vector can replicate during cellular division in eukaryotes permitting the continuous expression of Cas9, base editor, and sgRNAs in hPSCs. epi-BE also contains a drug resistance gene. Despite the low efficiency of plasmid delivery, we were able to greatly enrich the target cells through long-term drug screening and the proliferation of drug-resistant cells. We introduced mutations in three pathogenic genes of LQT, KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A, and screened a total of 328 clones, of which 104 were heterozygous (31.7%) and 30 were homozygous (9.1%) (Note 12). In this paper, we will show how to introduce LQT disease mutation loci into hPSCs step by step. To model LQT syndrome, the diseased hPSCs are differentiated into cardiomyocytes for phenotypic and functional characterization Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Fig. 1.

Overview of base editing of hPSCs for modeling LQT syndrome

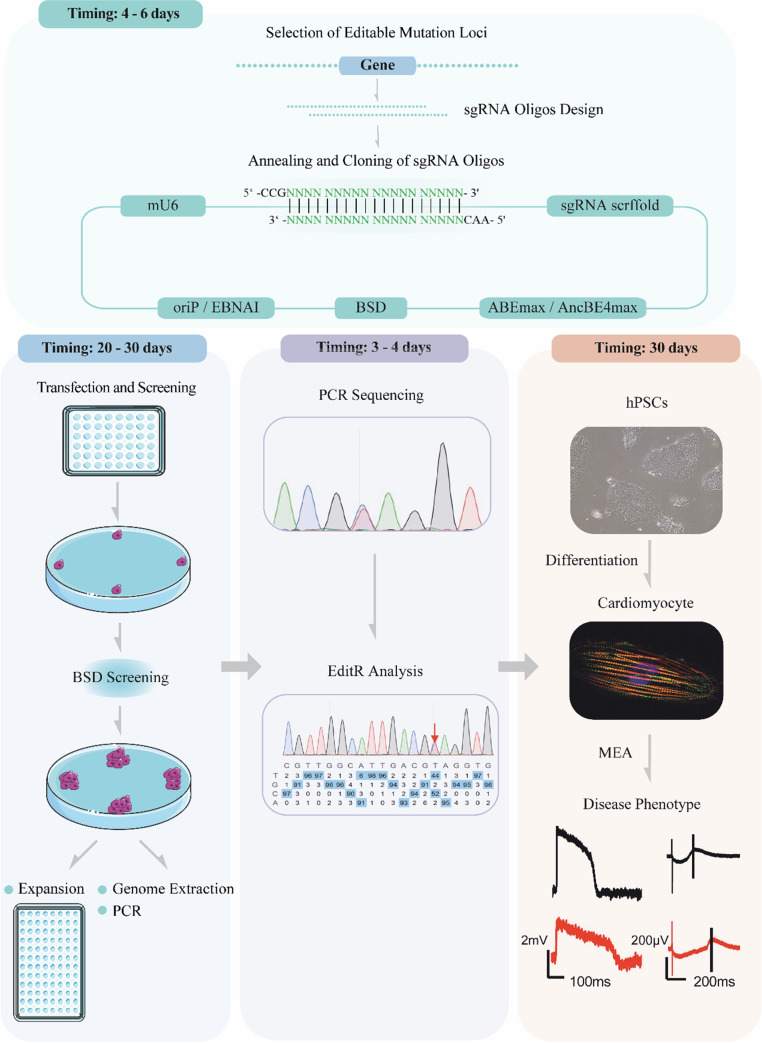

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of cell transfection and antibiotic screening

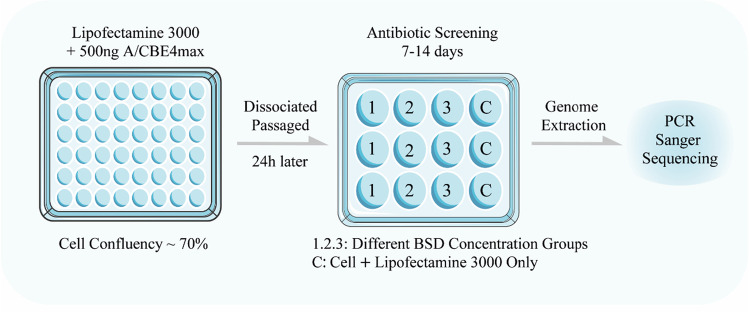

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of single cell clone screening

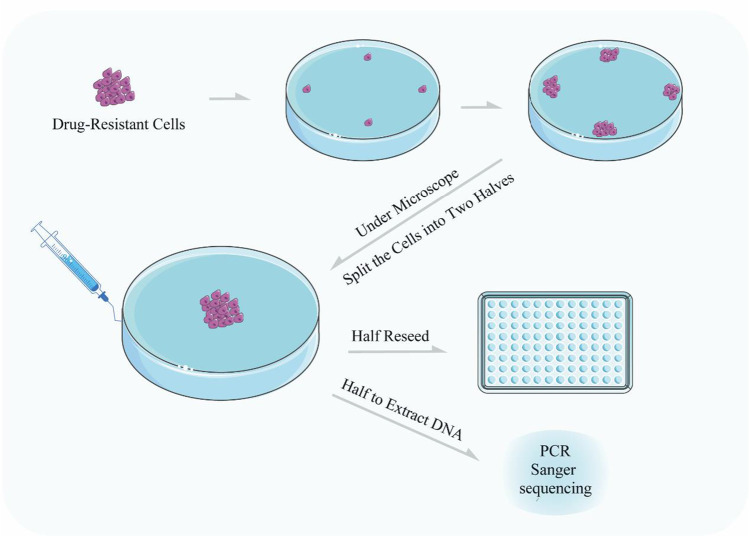

Fig. 4.

Cardiomyocytes differentiation and MEA testing. a Schematic diagram of the process of cardiomyocytes differentiation and photographs of cells at different days. b Cardiomyocytes plated on MEA plates and diagram of MEA results analysis

Materials

Reagents

Design of the Plasmids for Base Editing and Functional Analysis

Plasmids: epi-ABEmax (Addgene plasmid #135974), epi-BE4max (Addgene plasmid #135975).

PCR primers or oligos for sgRNA construction can be ordered with standard desalting purification at GUANGZHOU IGE BIOTECHNOLOGY LTD or other suppliers.

PrimeSTAR® Max DNA Polymerase (TAKARA, cat. no. R045Q).

FastPure® Gel DNA Extraction Mini Kit (Vazyme, cat. no. DC301)

EndoFree Mini Plasmid Kit II (TIANGEN, cat.no. 4992422)

Agarose (Sigma, cat. no. A9539)

100 bp DNA Ladder (Vazyme, cat.no. MD104-01)

Ultra GelRed Nucleic Acid Stain (Vazyme, cat. no.GR501-01)

BspQI (New England BioLabs, cat. no. R0712S)

T4 DNA Ligase (Vazyme, cat. no. C301-01)

FastPure Plasmid Mini Kit (Vazyme, cat. no. DC201-01)

DH5α chemically competent E. coli (Vazyme, cat. no. C502-02)

Ampicillin, 100 mg/ml (Beyotime, cat. no. ST008)

TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, cat.no. 4992254)

Cell Culture and Cardiomyocytes Differentiation

HEK293T cell line (Life Technologies, cat. no. R70007)

Human Embryonic Stem Cell H9 (National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, China, cat. no. SCSP-302)

DMEM, high glucose (Life Technologies, cat. no. 10566016)

Dulbecco’s PBS w/o Ca2+, Mg2+ (D-PBS) (Hyclone, cat. no. SH30028.02)

Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Life Technologies, cat. no.10270-106)

Opti-MEM™ reduced-serum medium (Life Technologies, cat. no. 11058-021)

Penicillin/streptomycin (Pen/strep), 100× (Life Technologies, cat. no. 15140-122)

EDTA (Cellapy, cat. no.CA3001500)

Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Life Technologies, cat. no. L3000008)

Accutase® (Sigma, cat. no. A6964-500ML)

ROCK1 inhibitor (Y-27632) (Selleck, cat. no. S6390)

P3 primary cell 4D-Nucleofector X kit S (Lonza, cat. no. V4XP-3032)

L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate (Sigma, cat. no.49752)

Recombinant Human Serum Albumin (Science Cell, cat. no. OsrHSA)

B-27™ Supplement, minus insulin (Life Technologies, cat. no. A1895601)

B-27™ Supplement, serum free (Life Technologies, cat. no. 17504044)

RPMI 1640 Medium (Life Technologies, cat. no. 61870150)

RPMI 1640 Medium, no glucose (Life Technologies, cat. no. 11879020)

CHIR-99021(Selleck, cat. no. S1263)

Wnt-C59 (Selleck, cat. no. S7037)

mTeSR-1 medium (STEMCELL Technologies, cat. no. 85850)

Matrigel® hESC-Qualified Matrix (Corning, cat. no. 354277)

Sodium DL-lactate (Sigma, cat. no. 71720)

Blasticidin S HCl (Selleck. cat. no. S7419)

Equipment

Standard microcentrifuge tubes, 1.5 ml (Eppendorf, cat.no. 0030125150)

15 ml Centrifuge Tube (Corning, cat. no. 430791)

Tissue culture dish, 100 × 20 mm (Corning, cat. no. 353003)

Tissue culture plate, 6 wells (Corning, cat. no. 353934)

Tissue culture plate, 96 wells (Corning, cat. no. 353075)

Cellometer AUTO T4 Bright Field Cell Counter (Nexcelom, cat. no. AUTO T4)

NanoDrop 2000 device, UV spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific)

4D-Nucleofector™ System (Lonza, cat. no. AAF-1002Band AAF-1002X)

1 ml sterile syringe (WEIGAO Group Medical Polymer CO., LTD, cat. no. ZSQWG1)

Softwares and Online Tools

CRISPR/Cas plasmids and resources on Addgene at https://www.addgene.org/CRISPR/

BLAST, human genome online tool: http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

BASE EDITING ANALYSIS TOOL: https://hanlab.cc/beat/

ImageJ, quantification software available at http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/

Snapgene: https://www.snapgene.com

Primer designing tool: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/

EditR: http://baseeditr.com/

Igor Pro: https://www.wavemetrics.com

AxIS Navigator, Cardiac Analysis Tool: https://www.axionbiosystems.com/products/software

Cas-Offinder: http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/

BE-Hive: https://www.crisprbehive.design

Culture Medium

HEK293T cell culture medium (500 ml): 440 ml DMEM, 50 ml FBS, 5 ml Pen/Strep. Store at 4 °C.

CDM3 (500 ml): 500 ml RPMI 1640, 0.25 g of Recombinant Human Serum Albumin, and 106.5 mg of L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate. Store at 4 °C.

Collagenase solution (2 mg/mL): Dissolve 500 mg of collagenase type I in 200 mL of D-PBS. Add 50 mL of fetal bovine serum

Methods

Selecting Editable LQT Disease Mutation Loci

The widely used base editing tools ABE or CBE can replace A with G and C with T. Based on this, our choice of mutation sites for LQT disease should be C > T, or A > G (for antisense chains, it is G > A, T > C). More than 90% of LQT is caused by mutations in the KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A genes. Therefore, we mainly screened for these three genes. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®) is a robust database that collates all known (published) gene lesions responsible for human inherited disease. We use this database to screen LQT mutations.

Input KCNQ1 OR KCNH2 OR SCN5A

Select: Gene Symbol

Select: Go!

Select: Missense/nonsense

Click: Get mutations

Check: “codon change” and “Phenotype”

All A > G, G > A, C > T, T > C mutation loci were recorded

Open the NCBI gene database https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/?term=

Enter the gene name (for example: KCNQ1)

Click “Search”

Chose “Homo sapiens”

Click “GenBank”

Click “Send to”

Download the gene sequence file

(See Note 1)

sgRNA Oligos Design

After the sgRNA is designed, we can first evaluate its editing efficiency on the BE-Hive website. To evaluate sgRNAs, on the website:

Step1: Input Sequence: paste your target sequence into the input sequence box

Step2: select: base editor/cell type

Step3: chose CRISPR protospacer

Annealing and Cloning of sgRNA Oligos

-

Pick a 20 bp spacer ahead of the PAM sequence (5’-NGG-3′) in the target locus, and then synthesize the two oligonucleotides as follows:

Top: 5’-tttNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN-3’.

Bottom: 5’-aacN’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N’N′-3’.

For example, the selected spacer and PAM sequence for the KCNQ1L114P/+ gene is 5’-GCTCGAGGAAGTTGTAGACG-CGG −3′. The sequences of KCNQ1L114P/+ sgRNA oligonucleotides are as follows:

KCNQ1L114P/+ Top: 5’-tttGCTCGAGGAAGTTGTAGACG -3’.

KCNQ1L114P/+Bottom: 5’-aacCGTCTACAACTTCCTCGAGC -3′.

(See Note 2)

Annealing the oligonucleotides as indicated below.

| 100uM KCNQ1L114P/+ Top | 1ul |

| 100uM KCNQ1L114P/+ Bottom | 1ul |

| 10X T4 DNA ligation buffer | 1ul |

| ddH2O | 7ul |

Place the above samples in a 95 °C water bath, switch off the power, and cool naturally to room temperature. Alternatives: You can anneal the oligonucleotides using a thermocycler instead of a hot water bath. Incubate the reaction solution at 95 °C for 5 min and then slowly cool it down to room temperature (20-30 °C) using a thermocycler—the temperature decreases by 1 °C per 10s.

-

3.

Dilute the annealed oligonucleotides 20 folds with ddH2O. Clone the annealed oligonucleotide into the sgRNA expression plasmid as indicated below.

| Diluted annealed oligonucleotides | 3ul |

| ABE/CBE sgRNA expression plasmid | 1ul |

| T4 DNA Ligase | 1ul |

| 10X T4 DNA ligase buffer | 2ul |

| ddH2O | 13ul |

Place at 37 °C and ligate for 5 min (See Note 3)

-

4.

According to the manufacturer’s protocol, transform 10 uL ligated product into 50 uL E. coli DH5a competent cells. The cells are plated onto an LB agar plate supplemented with the Ampicillin, and the plate is incubated at 37 °C for 14-16 h (See Note 4)

-

5.

Randomly pick several colonies to verify the successful cloning by Sanger sequencing. Sequencing primer: ATTCTTTCCCCTGCACTGTACCCC (See Note 5)

-

6.

Extract the plasmids by EndoFree Mini Plasmid Kit II according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Determine the concentration of the extracted plasmid using NanoDrop.

Base Editing and Blasticidin Selection

-

7.

Cells were plated into 48-well plates and transfected the next day at approximately 70% confluency.

-

8.

500 ng of epi-ABEmax/epi-AncBE4max plasmid was transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions on day 1. (See note 6)

-

9.

Cells were passaged on day 2 and selected by blasticidin. 2 μg/ml of blasticidin was added into the growth media, except on days 2, 6, and 11, where 8, 4, and 0 μg/ml of blasticidin were used, respectively. Transfected cells were harvested for analysis on days 6, 11, and 16. The antibiotic screening time can be shortened when editing efficiency is enough.

-

10.

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, the genomic DNA was isolated using TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit. Targets of base editing were amplified by PCR using PrimeSTAR® Max DNA Polymerase. The PCR products were sequenced using Sanger sequencing, and the editing efficiency was analyzed by EditR (Kluesner et al., 2018) or BEAT (https://hanlab.cc/beat/).

Single Cell-Derived Clone Screen

-

11.

The antibiotic-iPSCs were passaged with EDTA. Then, 1 × 105 cells were seeded on a Matrigel pre-coated 10 cm dish using mTeSR-1 cell culture medium with 5 μM of Y-27632. (See note 7)

-

12.

Twenty-four hours later, the mTeSR-1 media was replaced by new media without Y-27632. This media was changed every two days.

-

13.

Ten days after seeding, the single cell-derived clones were picked up using a 1 ml sterile syringe and divided into two halves. One half was placed on a Matrigel pre-coated 96-well plate for cell expansion. The other half extracted DNA using the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit for DNA sequencing. (See note 8)

Genotyping PCR

-

14.

Design Forward and Reverse primers flanking the region targeted by the sgRNAs for the genotyping. The PCR will be performed to confirm the outcomes of base substitution. This experiment is to extract DNA from a small number of cells for PCR experiments, and the steps are as follows:

Aspirate cells with a 50ul pipette, transfer to a 200ul PCR tube, and quick spin

95 °C for 10 min and cold down to 4 °C

Add 2ul of 20 mg/ml proteinase K solution and mix by quick spin

55 °C for 1 h, 95 °C for 10 min and cold down to 4 °C

The solution obtained is the cellular DNA extraction solution, which can be used as a template for PCR.

| 2x PrimeSTAR® Max DNA Polymerase | 25 ul |

| Primer-F | 2 ul |

| Primer-R | 2 ul |

| DNA solution | 8 ul |

| ddH2O | 13 ul |

Gently mix all the reagents and collect them by a quick spin. The order of addition of the reagents can be random.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

(See note 9)

Off-Target Analysis

-

15.

For each target site, five potential off-targets were selected based on Cas-Offinder and PCR-amplified for Sanger sequencing.

Cardiomyocyte Differentiation

-

16.

Cells (∼90% confluency) were seeded on a Matrigel pre-coated 6-well plate at a ratio of 1:6 in mTeSR-1 media. (See note 10)

-

17.

The media was changed to CDM3 supplemented with 6 μM of CHIR99021 when the cells reached ∼75% confluency.

-

18.

After 48 h, the media was changed to CDM3 [7] supplemented with 2 μM of Wnt-C59. After 2 days, the media was changed to CDM3 and refreshed every 2 days. After differentiation for 7– 8 days, spontaneous contracting cells could be observed.

-

19.

On day 12, Cardiomyocytes (CMs) were purified using a metabolic-selection method. The medium consisted of RPMI 1640 without glucose, 213 μg/ml of L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, 500 μg/ml of Oryza sativa-derived recombinant human albumin, and 5 mM of sodium DL-lactate.

-

20.

After purification, CMs were cultured with RPMI 1640 and B27 (with insulin). For cellular maintenance, the medium was changed every 3 days.

LQT Phenotype Identification Using MEA

-

21.

CMs were digested with Accutase. (See note 11)

-

22.

CytoView MEA24 plates (Axion Biosystems, Inc., Atlanta, United States) were pre-coated overnight using a 0.5% Matrigel phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution.

-

23.

15,000 CMs were plated on each multi-electrode array (MEA) well with RPMI/B27 medium and cultured for three days.

-

24.

When the cellular electrophysiological activity became stable, the experimental data were recorded using Maestro EDGE (Axion Biosystems, Inc., Atlanta, United States) according to the MEA manual. The data were analyzed using the AxIS Navigator, Cardiac Analysis Tool, and IGOR software.

Notes

The potential therapeutic targets were further screened according to the ABE/CBE sgRNA design rules, which must be in the form of 20 nt + PAM. The mutation site is in the sgRNA edit window 2-8. Therapeutic targets eligible for gene editing were obtained. To avoid bystander editing during gene editing, we recommend only one of the mutation loci in the edit window 2-8 of sgRNA. Other databases like ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/)are also recommended.

ttt and aac are the sequences that matche the sticky end produced by the enzymatic cleavage of the plasmid used in this paper. You should add the appropriate sequence to the sticky end sequence produced by the plasmid you are using.

The sgRNA expression plasmids in this protocol contain epi-ABEmax, epi-AncBE4max, which is an all-in-one episomal vector expressing a single guide RNA (sgRNA) with an adenine base editor (ABE) or a cytosine base editor (CBE). If you are using two plasmids for sgRNA and base editor expressing, you only need to ligate oligonucleotides to the sgRNA expression vector.

You should choose the appropriate antibiotic according to the resistance expressed by your plasmid.

You should choose the appropriate sequencing primer according to your plasmid.

We recommend the use of the LONZA 4D Nuclear Transfection System to transfer plasmids into cells, programmed as CA137.

EDTA is less toxic to cells. To obtain single cells, we try to increase the contact time between EDTA and the cells until the cells are observed as single cells under the microscope. Typically contact time is10-20 min.

The cell clone must not be too small, or the clone will fail to pick up. Generally, under a 10x microscope, the cell clone should fulfill the entire field. The microscope should be transferred to a biosafety cabinet in advance and UV irradiated for at least half an hour.

PCR conditions should be referred to the instructions for the polymerase used. We should determine primer Tm values in advance. The amount of DNA extracted by our method is minimal, and therefore the number of cycles of PCR should be increased, with a recommended setting of 38 cycles.

Matrigel was diluted using pre-cooled PBS solution at a ratio of 1:500. The process of CM differentiation is susceptible to mycoplasma, and we strongly recommend testing the mycoplasma before CM differentiation. The cell culture medium supernatant is aspirated and used as a template for PCR amplification using mycoplasma-specific primers and agarose gels for validation. Mycoplasma-specific primer [27]-F: CACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAAC, R: GGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATAC

If the CM differentiation is inefficient, dead cells are produced, and many cell fragments are released during CM purification. These cell fragments can bind to collagen, the cardiomyocyte, in a pile and hinder the CM digestion. Collagenase can be an excellent solution to this problem. Add collagenase solution to CM and incubate at 37 °C for 1 h. Aspirate the collagenase solution, add Accutase, and placed at 37 °C for 30 min.

Summary of base editing efficiency

| Gene | mutation | Total number of clones | Heterozygous clones | Homozygous clones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCNQ1 | L114P | 52 | 26(50%) | 3(5.8%) |

| KCNQ1 | R190Q | 77 | 22(28.6%) | 6(7.8%) |

| KCNH2 | Y616C | 4 | 4(100%) | 0(0) |

| KCNH2 | Y475C | 41 | 18(40.9%) | 8(19.5% |

| SCN5A | E1784K | 107 | 32(29.9%) | 5(4.7%) |

| SCN5A | R1879W | 47 | 2(4.3%) | 8(17%) |

| Average | 31.7% | 9.1% |

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. F.L., F. W.and X.Y. designed the experiments. T.G. and L.S. performed the experiments. F.W. analyzed and interpreted the data. F.l., F. W.and X.Y. provided conceptual advice and financial support. F. W. wrote the article.

Funding

This protocol is the result of work funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81800685, 81670702), The Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (No. 2018A030310039), the Science and Technology Project of Shenzhen (No. GJHZ20180413181702008).

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.De Los Angeles A, Ferrari F, Xi R, Fujiwara Y, Benvenisty N, Deng H, Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R, Lee S, Leitch HG, Lensch MW, Lujan E, Pei D, Rossant J, Wernig M, Park PJ, Daley GQ. Hallmarks of pluripotency. Nature. 2015;525(7570):469–478. doi: 10.1038/nature15515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang X, Chen Y, Liu X, Ye L, Yu M, Shen Z, Lei W, Hu S. Uncovering inherited cardiomyopathy with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Frontiers in Cell and Development Biology. 2021;9:672039. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.672039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonaventura G, Iemmolo R, Attaguile GA, La Cognata V, Pistone BS, Raudino G, D'Agata V, Cantarella G, Barcellona ML, Cavallaro S. iPSCs: A preclinical drug research tool for neurological disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(9):4596. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hicks M, Pyle A. The path from pluripotency to skeletal muscle: Developmental Myogenesis guides the way. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;17(3):255–257. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shan Y, Liang Z, Xing Q, Zhang T, Wang B, Tian S, Huang W, Zhang Y, Yao J, Zhu Y, Huang K, Liu Y, Wang X, Chen Q, Zhang J, Shang B, Li S, Shi X, Liao B, Zhang C, Lai K, Zhong X, Shu X, Wang J, Yao H, Chen J, Pei D, Pan G. PRC2 specifies ectoderm lineages and maintains pluripotency in primed but not naïve ESCs. Nature Communications. 2017;8(1):672. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00668-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P, Lin ZC, Churko JM, Ebert AD, Lan F, Diecke S, Huber B, Mordwinkin NM, Plews JR, Abilez OJ, Cui B, Gold JD, Wu JC. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nature Methods. 2014;11(8):855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambers SM, Fasano CA, Papapetrou EP, Tomishima M, Sadelain M, Studer L. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nature Biotechnology. 2009;27(3):275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee I, Li F, Kohler EE, Rehman J, Malik AB, Wary KK. Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell culture methods and induction of differentiation into endothelial cells. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2016;1357:311–327. doi: 10.1007/7651_2015_203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moretti A, Bellin M, Welling A, Jung CB, Lam JT, Bott-Flügel L, Dorn T, Goedel A, Höhnke C, Hofmann F, Seyfarth M, Sinnecker D, Schömig A, Laugwitz KL. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(15):1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang P, Sallam K, Wu H, Li Y, Itzhaki I, Garg P, Zhang Y, Vermglinchan V, Lan F, Gu M, Gong T, Zhuge Y, He C, Ebert AD, Sanchez-Freire V, Churko J, Hu S, Sharma A, Lam CK, Scheinman MM, Bers DM, Wu JC. Patient-specific and genome-edited induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes elucidate single-cell phenotype of Brugada syndrome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016;68(19):2086–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu H, Yang H, Rhee JW, Zhang JZ, Lam CK, Sallam K, Chang ACY, Ma N, Lee J, Zhang H, Blau HM, Bers DM, Wu JC. Modelling diastolic dysfunction in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients. European Heart Journal. 2019;40(45):3685–3695. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brida M, Chessa M, Celermajer D, Li W, Geva T, Khairy P, Griselli M, Baumgartner H, Gatzoulis MA. Atrial septal defect in adulthood: a new paradigm for congenital heart disease. European Heart Journal. 2021;18:ehab646. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo G, von Meyenn F, Rostovskaya M, Clarke J, Dietmann S, Baker D, Sahakyan A, Myers S, Bertone P, Reik W, Plath K, Smith A. Epigenetic resetting of human pluripotency. Development. 2017;144(15):2748–2763. doi: 10.1242/dev.146811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lan F, Lee AS, Liang P, Sanchez-Freire V, Nguyen PK, Wang L, Han L, Yen M, Wang Y, Sun N, Abilez OJ, Hu S, Ebert AD, Navarrete EG, Simmons CS, Wheeler M, Pruitt B, Lewis R, Yamaguchi Y, Ashley EA, Bers DM, Robbins RC, Longaker MT, Wu JC. Abnormal calcium handling properties underlie familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathology in patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12(1):101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han L, Li Y, Tchao J, Kaplan AD, Lin B, Li Y, Mich-Basso J, Lis A, Hassan N, London B, Bett GC, Tobita K, Rasmusson RL, Yang L. Study familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cardiovascular Research. 2014;104(2):258–269. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C, Chen S, Zhou Y, Zhao Y, Liu P, Cai J. Application of induced pluripotent stem cell transplants: Autologous or allogeneic? Life Sciences. 2018;212:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533(7603):420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rees HA, Liu DR. Base editing: Precision chemistry on the genome and transcriptome of living cells. Nature Reviews. Genetics. 2018;19(12):770–788. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuo E, Sun Y, Wei W, Yuan T, Ying W, Sun H, Yuan L, Steinmetz LM, Li Y, Yang H. Cytosine base editor generates substantial off-target single-nucleotide variants in mouse embryos. Science. 2019;364(6437):289–292. doi: 10.1126/science.aav9973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Programmable base editing of a•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. 2017;551(7681):464–471. doi: 10.1038/nature24644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao D, Li J, Li S, Xin X, Hu M, Price MA, Rosser SJ, Bi C, Zhang X. Glycosylase base editors enable C-to-a and C-to-G base changes. Nature Biotechnology. 2021;39(1):35–40. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0592-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurt IC, Zhou R, Iyer S, Garcia SP, Miller BR, Langner LM, Grünewald J, Joung JK. CRISPR C-to-G base editors for inducing targeted DNA transversions in human cells. Nature Biotechnology. 2021;39(1):41–46. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0609-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molla KA, Yang Y. CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Base editing: Technical considerations and practical applications. Trends in Biotechnology. 2019;37(10):1121–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ihry RJ, Worringer KA, Salick MR, Frias E, Ho D, Theriault K, Kommineni S, Chen J, Sondey M, Ye C, Randhawa R, Kulkarni T, Yang Z, McAllister G, Russ C, Reece-Hoyes J, Forrester W, Hoffman GR, Dolmetsch R, Kaykas A. p53 inhibits CRISPR-Cas9 engineering in human pluripotent stem cells. Nature Medicine. 2018;24(7):939–946. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi T, Wu F, Xie Y, Gao S, Li M, Pu J, Li D, Lan F, Wang Y. Base editing mediated generation of point mutations into human pluripotent stem cells for modeling disease. Frontiers in Cell and Development Biology. 2020;8:590581. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.590581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu X, Zhang S, Chang Y, Wu F, Bai R. Establishment of a KCNQ1 homozygous knockout human embryonic stem cell line by episomal vector-based CRISPR/Cas9 system. Stem Cell Research. 2021;55:102467. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2021.102467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.