Abstract

Eighty percent (21 of 26) of macrolide-resistant Peptostreptococcus strains studied harbored the ermTR gene. This methyltransferase gene is also the most frequently found gene among macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes strains. Transfer of the ermTR gene from Peptostreptococcus magnus to macrolide-susceptible S. pyogenes strains indicates that this resistance determinant may circulate among gram-positive aerobic and anaerobic species of the oropharyngeal bacterial flora.

Resistance to macrolides in Peptostreptococcus species is not a rare event. In our hospital, susceptibility of clinical isolates has been routinely studied using the broth microdilution technique (8); the E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) was used in strains with inadequate growth in liquid medium. Our rates of erythromycin resistance (MIC ≥ 8 μg/ml) in the last 6 years (1994 to 1999) ranged from 30.3 to 61.0%. The rates of the 158 erythromycin-resistant strains isolated in this period for which erythromycin MICs were 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, and >128 μg/ml were 13.3, 7.6, 2.5, 3.2, 5.7, and 67.7%, respectively. In 1992, we showed that both inducible and constitutive macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS) resistance phenotypes occurred in Peptostreptoccus, thus indicating the involvement of an erm mediated mechanism (11). The fact that these phenotypes were found among different Peptostreptococcus species suggests that erm genes are not only common but also circulate among species of this bacterial genus. In this work, we present evidence that MLS resistance in Peptostreptococcus is determined by erm genes, most frequently by ermTR, and that these genes can be conjugatively transferred. As the ermTR determinant is the erm gene most common among Streptococcus pyogenes isolates, we hypothesized that Peptostreptococcus could serve as a potential source of macrolide resistance in group A beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Twenty-six high-level macrolide-resistant (erythromycin MIC of ≥32 μg/ml) clinical strains of different species in the Peptostreptococcus genus (eight of Peptostreptococcus magnus, six of Peptostreptococcus asaccharolyticus, five of Peptostreptococcus spp., three of Peptostreptococcus anaerobius, three of Peptostreptococcus prevotii, and one of Peptostreptococcus tetradius) were studied. As deduced from their erythromycin and clindamycin MICs and the double-disk test (in situ induction of resistance on solid medium with erythromycin disks apposed to clindamycin disks) (14, 17), constitutive and inducible resistance phenotypes were found in 16 and 10 strains, respectively. To identify the class of the presumed erm genes involved in Peptostreptococcus MLS resistance, specific PCR amplification of the genes ermA, ermB, ermC, ermF, ermG, ermQ, and ermTR was performed with the DNA from the 26 selected resistant strains and from known erm-positive control strains. Total genomic DNA was obtained using either the InstaGene matrix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) or the proteinase K treatment method (2). Primers used for detection of the ermA, ermB, ermC, and ermTR genes were as previously described (6, 16). Primers for ermF, ermG, ermQ, and again for ermTR genes were designed in our laboratory on the basis of their published sequences (1, 7, 10, 15). The sequences of these primers were as follows: F1, 5′ TTACGGGTCAGCACTTTACTA 3′; F2, 5′ ACTTTCAGGACCTACCTCATA 3′; G1, 5′ AGGGAAAGGTCATTTTACTGC 3′; G2, 5′CCC TACCTATAACTAAACATT 3′; Q1, 5′ TAATAATTATAGAGGAAAAGT 3′; Q2, 5′ TATCCAATCATTATAAGAAAC 3′; TR′1, 5′ AGAAGGTTATAATGAAACAGAA 3′; TR′2, 5′ GGCATGACATAAACCTTCAT 3′. The PCR mixture and the amplification programs were as previously described (6, 16). In each case, annealing temperatures were adjusted for the nucleotide composition of the different primers. Electrophoresis was carried out on 1.5 and 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide, and the sizes of PCR products were determined using standard molecular weight markers (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Control strains were as follows: Staphylococcus aureus RN1389 (ermA), S. aureus RN4220 (ermC), and S. pyogenes 02C1061:AC1 (ermB), provided by J. Sutcliffe (Pfizer, Groton, Conn.); Bacteroides fragilis V479 (ermF), provided by C. J. Smith (East Carolina University); Bacillus subtilis JIR1021:BD1146 (ermG), Escherichia coli JIR2038:MC1022 (ermQ), and E. coli JIR1974:JM105 (ermQ), provided by J. I. Rood (Monash University, Clayton, Australia); and S. pyogenes S211 (ermTR), provided by C. Torres (La Rioja University, Logroño, Spain).

Amplification of the DNA from the positive controls with the corresponding primers generated PCR products of the expected sizes. PCR products of identical corresponding size were obtained with primers TR1 and TR2, F1 and F2, and B1 and B2, and DNA from 21, 5, and 1 Peptostreptococcus strains, respectively. The specific nature of the ermTR, ermF, and ermB amplification products was controlled by DNA sequencing of one of each PCR product. In these three cases the amplified sequences corresponded to the expected amino acid sequence of the different erm genes (sequences available at the European Bioinformatics Institute website [http://www.ebi.ac.uk.]). Therefore, 80% (21 of 26) of the Peptostreptococcus strains studied carried the ermTR that was found in all species, five strains (19%) contained the ermF gene (two of P. anaerobius, one of P. asaccharolyticus, and two of Peptostreptococcus spp.), and one of them (P. anaerobius) contained both the ermF and the ermB genes.

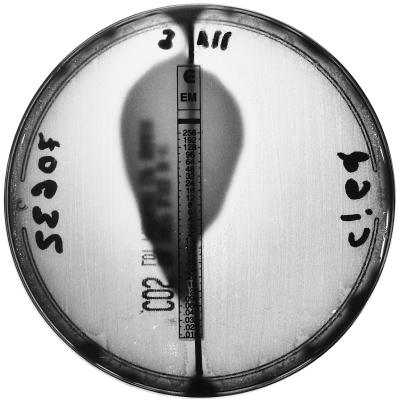

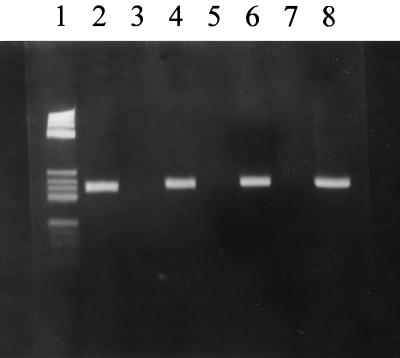

The transferability of the ermTR determinant from P. magnus RYC5.257 (erythromycin MIC of >128 μg/ml, inducible phenotype) to fully macrolide-susceptible S. pyogenes strains RYC69951 and RYC70632 (erythromycin MICs of 0.047 and 0.064 μg/ml, respectively) was first studied. The conjugation was carried out on solid media and by adapting previously published procedures (12, 13). In short, recipient S. pyogenes strains were grown during the day of mating in brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). Anaerobic donors were grown anaerobically on brucella blood agar plates (Oxoid) at 37°C for 24 to 48 h. Turbid suspensions of the agar anaerobic growth were mixed with equal volumes of the receptor. The mating mixtures were plated on brucella blood agar plates and incubated under anaerobic conditions (5% CO2, 10% H2, and 85% N2) at 37°C for 60 h. Transconjugants were selected on aerobically incubated Columbia blood agar (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) plates containing 0.5 μg of erythromycin per ml and were obtained at frequencies of 10−6 per recipient. This frequency was consistently found in three replicate experiments. To rule out the possibility of an inadvertent transformation, the mating studies were repeated in parallel in the presence or absence of DNase (400 U/ml) (Boehringer). The erythromycin MICs (E-test) (Fig. 1) for S. pyogenes transconjugants from both mating pairs were 1 and 1.5 μg/ml, respectively, and their inducible MLS phenotype was confirmed by the double-disk test. The presence of the ermTR gene in S. pyogenes transconjugants was verified by PCR using the TR′1 and TR′2 primers (Fig. 2). PCR products were sequenced and the identities of the donor and transconjugant amplified products were thus confirmed.

FIG. 1.

Erythromycin E-test with S. pyogenes RYC70632 (left) and transconjugant from the P. magnus RYC5.257-S. pyogenes RYC70632 mating (right).

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis. Lane 1, DNA molecular weight marker V. The other lanes represent the products of PCR results with TR′1 and TR′2 primers and DNA from the following strains: lane 2, S. pyogenes S211 (TR-positive control strain); lane 4, P. magnus RYC5.257 (inducible MLS-resistant strain); lanes 5 and 7, S. pyogenes RYC69951 and RYC70632 (erythromycin-susceptible strains); lanes 6 and 8, transconjugants from P. magnus RYC5.257-S. pyogenes RYC69951 and P. magnus RYC5.257-S. pyogenes RYC70632 matings. Lane 3 represents the negative control without DNA template.

The proportion of ermTR harboring Peptostreptococcus strains able to transfer macrolide resistance to S. pyogenes may be low. No transconjugants were obtained by mating four more P. magnus, two more P. prevotii, and one more P. asaccharolyticus strains. Nevertheless, the fact that ermTR determinant could be transferred in the case described in this paper suggests that this gene may circulate among both aerobic and anaerobic cocci of the oropharyngeal flora. Macrolide resistance in S. pyogenes is a problem of growing concern. Interestingly, ermTR is the most common 23S rRNA methylase-encoding gene in S. pyogenes (3, 4, 5, 9). Peptostreptococcus is considered a normal inhabitant of pharyngeal, dental, and gingival flora. Considering that macrolide-selective pressure is preferentially exerted on the more frequent bacterial populations, Peptostreptococcus could serve as an important reservoir for ermTR-mediated macrolide resistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berryman D I, Lyristis M, Rood J I. Cloning and sequence analysis of ermQ, the predominant macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance gene in Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1041–1046. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.5.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chung W O, Werckenthin C, Schwarz S, Roberts M C. Host range of the ermF rRNA methylase gene in bacteria of human and animal origin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:5–14. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Azavedo J C, Yeung R H, Bast D J, Duncan C L, Borgia S B, Low D E. Prevalence and mechanisms of macrolide resistance in clinical isolates of group A streptococci from Ontario, Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2144–2147. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.9.2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giovanetti E, Montanari M P, Mingoia M, Varaldo P E. Phenotypes and genotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes strains in Italy and heterogeneity of inducibly resistant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1935–1940. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kataja J, Huovinen P, Skurnik M, Seppälä H The Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. Erythromycin resistance genes in group A streptococci in Finland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:48–52. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kataja J, Seppälä H, Skurnik M, Sarkkinen H, Huovinen P. Different erythromycin resistance mechanisms in group C and group G streptococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1493–1494. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monod M, Mohan S, Dubnau D. Cloning and analysis of ermG, a new macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance element from Bacillus sphaericus. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:340–350. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.340-350.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria, 4th ed. Approved standard M11–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portillo A, Lantero M, Gastanares M J, Ruiz-Larrea F, Torres C. Macrolide resistance phenotypes and mechanisms of resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes in La Rioja, Spain. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;13:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen J L, Odelson D O, Macrina F L. Complete nucleotide sequence and transcription of ermF, a macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinant from Bacteroides fragilis. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:523–533. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.523-533.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reig M, Moreno A, Baquero F. Resistance of Peptostreptococcus spp. to macrolides and lincosamides: inducible and constitutive phenotypes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:662–664. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.3.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts M C. Tetracycline resistance in Peptostreptococcus species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1682–1684. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts M C, Lansciardi J. Transferable Tet M in Fusobacterium nucleatum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1836–1838. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seppälä H, Nissinen A, Yu Q, Huoniven P. Three different phenotypes of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in Finland. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:885–891. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seppälä H, Skurnik M, Soini H, Roberts M C, Huovinen P. A novel erythromycin resistance methylase gene (ermTR) in Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:257–262. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutcliffe J, Grebe T, Tait-Kamradt A, Wondrack L. Detection of erythromycin-resistant determinants by PCR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2562–2566. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisblum B, Graham M Y, Gryczan T, Dubnau D. Plasmid copy number control: isolation and characterization of high-copy-number mutants of plasmid pE194. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:635–643. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.635-643.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]