The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) demonstrated that intensive blood pressure (BP) treatment (<120 mmHg) decreases major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) rates compared to standard treatment (<140 mmHg).1 We recently reported that intensive treatment in SPRINT participants increased a composite of six treatment-related adverse events.2 While the magnitude of the benefits/harms have been presented previously,1,2 their timing has not been well characterized. For multimorbid older adults with limited life expectancy, the time to benefit (TTB) and time to harm (TTH) for an intervention may be especially important since interventions with a short TTH may expose those with limited life expectancy to the harms with little chance of surviving to experience the benefits.3

Methods

Using the SPRINT_POP dataset, we fit Cox survival models and graphed Kaplan–Meier survival curves by treatment intensity. The efficacy outcome was the composite SPRINT MACE outcome.1 The safety outcome was a composite of six treatment-related adverse events (hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, injurious falls, electrolyte abnormality, or acute kidney injury) that was centrally adjudicated as a serious adverse event or resulted in an emergency department (ED) visit.2 A sensitivity analysis was performed with the six treatment-related adverse events adjudicated as only SAEs (without ED visits). Following the method used by previous investigators,4 we determined the TTB and the TTH graphically, visually identifying the timepoint at which the curves between intensive and standard therapy separate.

Results

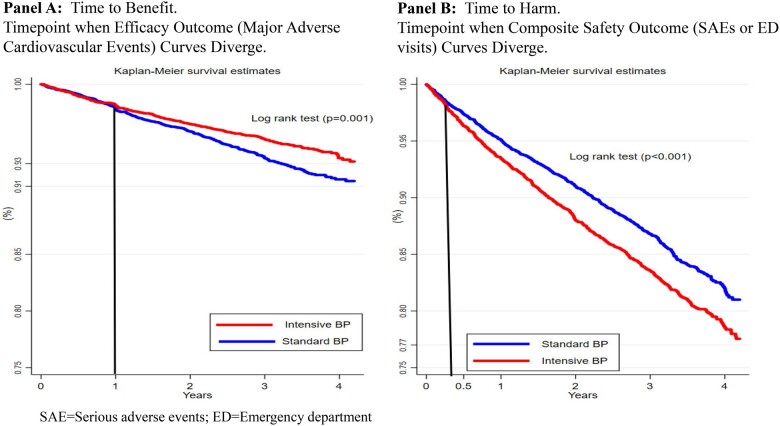

By 4.2 years, 6.0% (N = 562/9361) of SPRINT participants experienced the efficacy outcome, 15.7% (N = 1470) experienced the safety outcome. For the efficacy outcome, the Kaplan–Meier curves of the standard and intensive BP treatment arms overlap for 1 year before diverging (Figure 1A), suggesting no benefit to more intensive BP control in the first year. Thus, the TTB for more intensive BP control is 1 year. The absolute magnitude of benefit ranged from 0% (0–1 years) to 1.6% at 4.2 years. For the safety outcome, the Kaplan–Meier curves of the standard and intensive BP treatment arms overlap for 3 months before diverging, suggesting that the harms of more intensive BP management are seen after 3 months. In other words, the TTH for more intensive BP control is 3 months. The absolute magnitude of harms was two-fold higher than the benefits, ranging from 0% at 0–3 months to 3.2% at 4.2 years. No substantiative changes were noted with the sensitivity analysis.

Figure 1.

Graphs displaying the Kaplan–Meier survival curve by blood pressure treatment intensity in SPRINT trial participants. (A) Composite efficacy outcome and (B) Composite safety outcome in SPRINT trial participants. The black lines are drawn where the lines diverge, representing the time to benefit or harm.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available to the public in [National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes) Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center] at [https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/sprint/], and can be obtained by requesting access at [https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/login/?next=/requests/type/sprint/].

Discussion

The TTB/TTH for preventive/therapeutic interventions vary widely3 and harm often occurs before the benefits. The current study adds to the literature demonstrating that SAEs from intensive BP treatment are seen after 3 months, while the benefits (decrease in MACE) are not seen until 1 year. Our TTB/TTH results can inform an evidence-based shared decision-making discussion regarding the optimal BP treatment target. For example, older adults with a life expectancy <1 year may not be good candidates for intensive BP treatment since they would be exposed to the harms of treatment and unlikely to survive to benefit from treatment.2

Since our study relies on SPRINT data, it is unclear if our results apply to patients who do not meet SPRINT inclusion criteria. Application of TTB/TTH requires subjective determinations of the relative importance of avoiding MACE vs. avoiding SAEs for each patient. Also, TTB/TTH determination should be interpreted cautiously in the presence of Kaplan–Meier curves having more than one point of convergence. Further research is needed in this area.

Conclusions

We found that intensive BP treatment was associated with reduced MACE beginning at 1 year, and excess of adverse events beginning at 3 months. Our results may inform shared decision-making discussions between patients with limited life expectancy and their clinicians regarding appropriate BP treatment targets.

Conflict of interest: E.P. has no conflicts of interest to disclose. E.P. receives research funding from AstraZeneca, Janssen, Amgen, Sanofi. These are not relevant to the contents of current manuscript. D.H.K. has no conflicts of interest to disclose. D.H.K. was supported by NIA grant R21AG060227. S.J.L. has no conflicts of interest to disclose. S.J.L. was supported by NIA grant R01AG047897, R01AG057751, and VA HSR&D grant IIR 15-343. A.K., P.G., M.W.R. has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Ashok Krishnaswami, Division of Cardiology, Kaiser Permanente San Jose Medical Center, 270 International Circle, 2-North, 2nd Floor, San Jose, CA 95119, USA; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Eric D Peterson, Duke Clinical Research Institute and Division of Cardiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA.

Parag Goyal, Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY, USA.

Dae Hyun Kim, Hinda and Arthur Marcus Institute for Aging Research, Hebrew SeniorLife, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Michael W Rich, Division of Cardiology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Sei J Lee, Division of Geriatrics, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA.

References

- 1. Wright JT Jr, Williamson JD et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krishnaswami A, Peterson E, Kim DH, Goyal P, Rich MW. Efficacy and safety of intensive blood pressure therapy using restricted mean survival time - insights from the SPRINT trial. Am J Med doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lee SJ, Leipzig RM, Walter LC. Incorporating lag time to benefit into prevention decisions for older adults. JAMA 2013;310:2609–2610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holmes HM, Min LC, Yee M, Varadhan R, Basran J, Dale W et al. Rationalizing prescribing for older patients with multimorbidity: considering time to benefit. Drugs Aging 2013;30:655–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available to the public in [National Institutes of Health (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes) Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center] at [https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/sprint/], and can be obtained by requesting access at [https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/login/?next=/requests/type/sprint/].