Abstract

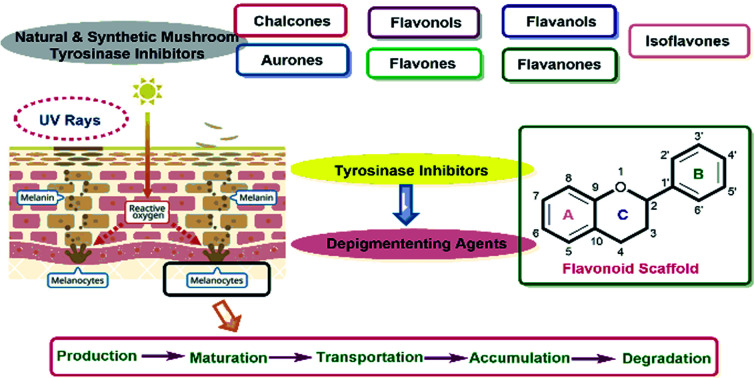

Tyrosinase is a multifunctional glycosylated and copper-containing oxidase that is highly prevalent in plants and animals and plays a pivotal role in catalyzing the two key steps of melanogenesis: tyrosine's hydroxylation to dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA), and oxidation of the latter species to dopaquinone. Melanin guards against the destructive effects of ultraviolet radiation which is known to produce considerable pathological disorders such as skin cancer, among others. Moreover, the overproduction of melanin can create aesthetic problems along with serious disorders linked to hyperpigmented spots or patches on skin. Several skin-whitening products which reduce melanogenesis activity and alleviate hyperpigmentation are commercially available. A few of them, particularly those obtained from natural sources and that incorporate a phenolic scaffold, have been exploited in the cosmetic industry. In this context, synthetic tyrosinase inhibitors (TIs) with elevated efficacy and fewer side effects are direly needed in the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries owing to their protective effect against pigmentation and dermatological disorders. Furthermore, the biological significance of the chromone skeleton and its associated medicinal and bioactive properties has drawn immense interest and inspired many researchers to design and develop novel anti-tyrosinase agents based on the flavonoid core (2-arylchromone). This review article is oriented to provide an insight and a deeper understanding of the tyrosinase inhibitory activity of an array of natural and bioinspired phenolic compounds with special emphasis on flavonoids to demonstrate how the position of ring substituents and their interaction with tyrosinase could be correlated with their effectiveness or lack thereof against inhibiting the enzyme.

This review revealed that among all the natural and synthetic flavonoids, the inhibitory findings suggest that the flavonol moiety can serve as an effective and a lead structural scaffold for the further development of novel TIs.

1. Introduction

Tyrosinase (E.C. 1.14.18.1) is a multifunctional copper-containing oxidase enzyme1,2 and is biologically significant because of the key role it plays in the biosynthesis of melanin pigment in living organisms.3–6 It catalyzes the o-hydroxylation of polyphenolic substrates to diphenol (catechol) derivatives, which further oxidize to o-quinone products.7 Tyrosinase is known as a rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the hydroxylation of l-tyrosine to l-DOPA and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine to dopaquinones which can cause unusual melanin pigment accumulation in the outermost layer of the skin.8 In this context, the standard tyrosinase inhibitors (TIs) such as kojic acid, tropolone, hydroquinone and mercury are clinically effective and may function as medicines for facial aesthetic treatments and other more serious dermatological disorders related to melanin hyperpigmentation in human skin. In addition, they are used in-cosmetics as skin-whitening agents and in agriculture as bio-insecticides.9–12 These inhibitors typically work by chelating with Cu2+ cation in the active site of tyrosinase or replacing it, as in the case of mercury, thus inhibiting the substrate–enzyme interaction and disrupting the ensuing electrochemical oxidation process. Over the past decade, a number of naturally occurring and synthetic TI's have been reported,13–15 though most of these inhibitors have associated toxic effects and low efficacy problems. In addition to providing pigmentation necessary for photoprotection, tyrosinase is also responsible for a variety of biological processes in arthropods including wound healing, cuticle sclerotization, and protective encapsulation. In plants, it is responsible for promoting enzymatic browning processes in damaged crops following harvest handling and managing. Thus, the production of efficient and harmless TI's is therefore essential not only for insect control, but also for use in the cosmetic, food, medical and agricultural industries.16

Despite extensive efforts to design and synthesize TI's, such compounds are scant and only few (e.g., PTU, anthracene, tropolone, and arbutin) have been employed in cosmetics and as therapeutic agents.17–21 However, because of poor safety profiles, adverse effects, or low efficacy, only a handful of them have been continued and put into practice.22–29 Undoubtedly, now more than ever, there is an urgent need to identify and develop more efficient and safer tyrosinase inhibitors.

1.1. The role of tyrosinase enzyme in the biosynthesis of melanin pigment

Melanin is the essential pigment formed by the dermal cells in the deepest layer of the epidermis known as the basal layer. It is produced by specialized cells called melanocytes through a multi-step chemical process where the amino acid tyrosine is oxidized, followed by polymerization. Melanogenesis is initiated in the skin following exposure to UV radiation and is able to dissipate almost completely the absorbed UV radiation. Thus, melanin performs an essential role in shielding the skin from the detrimental impacts of the sun's ultraviolet rays.30–32 Even though melanin primarily exhibits a photoprotective role in human skin, the accretion of melanin in various parts of the skin results in more pigmented spots and patches that could become an aesthetic problem.33,34 In worst cases, frequent exposure to UV radiation may be associated with increased risk of a cancer of melanocytes know as malignant melanoma. Furthermore, the enzymatic browning on the sliced surface of fresh fruits and vegetables can reduce the shelf life and impact their quality.35,36 Melanogenesis is the mechanism that leads to the development of dark molecular stains, i.e., melanin. When the skin is exposed to frequent and excessive UV radiation, abnormal melanin pigment formation occurs, creating severe aesthetic deformity especially common among elderly and middle-aged people. The biosynthesis of melanin can also be triggered by free radicals. As a countermeasure, antioxidants that can detoxify free radicals prevent oversupply of melanin. Few examples of antioxidants used as melanogenesis inhibitors include vitamin C and reduced glutathione. The benefit of developing tyrosinase chemistry is expected to provide deeper understanding of how to increased shelf life of products and efficiently increase farming yields while simultaneously minimizing economic loss.37–41

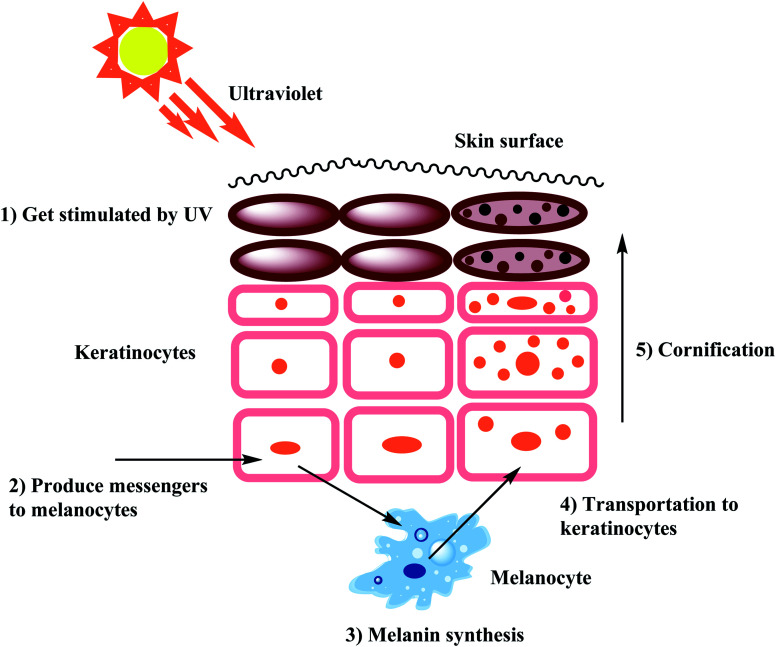

As stated earlier, melanocytes are cells produced in the dermal basal layer and are important in melanogenesis, the process of biosynthesizing melanin. Melanocytes are melanoblasts formed-dendritic cells that are unpigmented cells originating from neural crest cells of the embryos. These are mainly involved in melanin pigment synthesis. Each melanocyte is surrounded by about 36 keratinocytes which are the primary type of cell present in the outermost layer of the skin. After synthesizing melanin, it is stored inside melanosomes and subsequently transferred, using extended dendrites, to the outermost layer of suprabasal keratinocytes.42Fig. 1 shows that skin pigmentation is caused by keratinocyte cornification which includes the mature melanosomes which are biosynthesized, used to store melanin and transferred by the melanocytes to the keratinocytes. Eventually, keratinocytes undergo a process of cornification or programmed cell death and migrate, along with the engulfed melanin, to the skin surface. Cornification forms the outermost skin barrier known as the cornified layer.

Fig. 1. Mechanism of skin pigmentation.

With tyrosinase being the main enzyme that boosts up the process of melanin formation, tyrosinase inhibitors represent key inhibitory agents to combat the excess production of melanin. On the other hand, since the biosynthesis of melanin can also be triggered by free radicals, various natural and synthetic antioxidant systems able to scavenge such radicals may control excess production of melanin.43–46

2. Properties of various kinds of tyrosinase

2.1. Properties of mushroom tyrosinase

Tyrosinases have been extracted and refined from a variety of natural sources including some herbs, animals, and microbes. Although in many cases the isolated enzymes were sequenced, especially those extracted from humans, very few were properly characterized or probed. Recently, a new tyrosinase produced by Sahara soil actinobacteria was isolated and chemically characterized to detect novel enzymes useful for biotechnological purposes. Heretofore, among the various sources of tyrosinase, the Agaricus bisporus mushroom is the most common and inexpensive tyrosinase source where the enzyme exhibits high level of structural resemblance and homology to the human tyrosinase. Tyrosinase, a 120 kDa tetramer with two isolated intense and light subunits, was isolated from Agaricus bisporus by Bourquelot and Bertrand in 1895. It binds to six histidine residues and has three domains and two copper-binding sites that interact with molecular oxygen in the tyrosinase active site. Additionally, its structure is stabilized by the presence of disulfide linkage. Recently, a 50 kDa Agaricus bisporus (H-subunit) tyrosinase isoform with a high specific activity of over 38 000 U per mg has been identified and purified.47–52a

2.2. Properties of mammalian tyrosinase

Tyrosinases found in different living species are often very diverse in terms of chemical structure, structural properties, distribution in various tissues, and cellular location. The mammalian tyrosinase is characterized as single membrane-spanning transmembrane protein.52b In humans, this enzyme is sorted into organelles know as melanosomes52c and the catalytically active site of the protein is situated within melanosomes. Notably, only a short, enzymatically superfluous part of the protein extends into the cytoplasm of the melanocyte. Among the different known types of tyrosinases, the mushroom tyrosinase is known to exhibit the highest homology with mammalian tyrosinase and is the only commercially available enzyme and may be purchased through several chemical vendors.52d

2.3. Properties and significance of human tyrosinase

In humans, melanin is biosynthesized in melanosomes, which are organelles located inside melanocytes in skin and hair, and retinal pigment epithelium cells in the eye.52e Three tyrosinase-like enzymes are involved in its biosynthesis, tyrosinase (TYR) and tyrosinase-related proteins 1 and 2 (TYRP1 and TYRP2). Recent developments on the structure of TYR and TYRPs and their function by virtue of the crystal structure of human TYRP1, which represents the first available structure of a mammalian melanogenic protein have been reviewed by X. Lai et al.52f Combining the preceding structure with those found for tyrosinases from other lower eukaryotes and mutagenesis studies of catalytically active domains, have provided deeper insight into the mechanism of action of TYR and TYRPs proteins. In addition, a TYRP1-based homology model of TYR has now given the necessary foundation to gene map and investigate mutations associated with albinism, as well as to design specific anti-melanogenic agents. Mutations in the TYR or TYRP1 genes leads to oculocutaneous albinism (OCA1 and OCA3, respectively), a group of autosomal recessive conditions involving underproduction of melanin in skin, hair and eyes. Further, TYR and TYRP1 variants are closely associated with the development of melanoma, a malignant tumor of melanocytes responsible for the majority skin cancer related deaths.52g On the other hand, overproduction of melanin or abnormal distribution may lead to pigmentation disorders, such as over-tanning, age spots and melasma,52g which has triggered the development of skin-whitening products to lower the melanin content. Nowadays, inhibition of melanin biosynthesis is being considered as a rational therapeutic strategy to treat advanced melanotic melanomas.52h

2.4. Reaction mechanism of tyrosinase

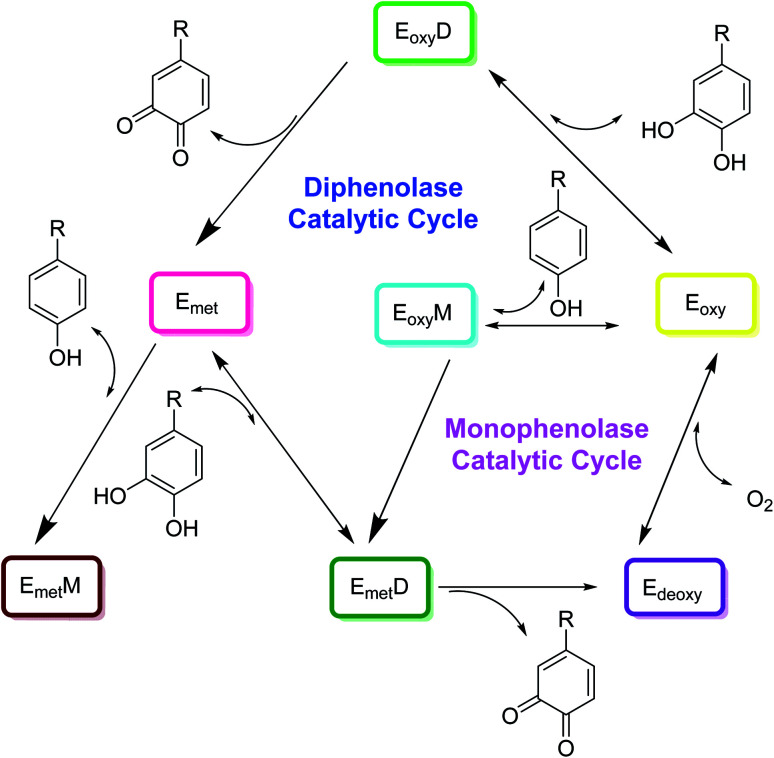

The catalytic cycle of tyrosinase involves two steps as shown in Fig. 2. First, monophenols are hydroxylated to o-diphenols by a monophenolase activity, and diphenols are hydroxylated by a diphenolase activity. In the second step, tyrosinase oxidizes o-diphenols to o-quinones. There exist a variety of chemical reactions that are coupled simultaneously to the enzymatic reaction in which two o-dopaquinone molecules react with each other to produce an o-diphenol fragment and a dopachrome particle (Fig. 2). Later on, when the tyrosinase molecule reacts with an o-diphenol, it is possible to investigate diphenolase behavior on its own. They form met-tyrosinase that furtherly joins the o-diphenol activating the complex EmD. This complex then oxidizes the o-diphenols into o-quinone and subsequently the enzyme is transformed into the deoxytyrosinase form. Ed exhibits high affinity for O2, initiating the oxy-tyrosinase form, which furtherly attaches to another o-diphenol fragment, forming a new multifaceted EoxD complex.

Fig. 2. Catalytic cycle for the hydroxylation of monophenol and the conversion of o-diphenol to o-quinone by the tree types of tyrosinase, Eoxy, Emet, and Edeoxy.24.

Later, o-diphenol is oxidized once more to o-quinone and Em is formed, completing the catalytic cycle. Following these enzymatic reactions, two o-quinone molecules react together, producing dopachrome and regenerating an o-diphenol molecule. Although diphenolase activity may be reviewed independently, this is not valid for monophenolase activity because chemical reactions of diphenolase and monophenolase production take place simultaneously. Furthermore, the monophenolase activity is expressed by tyrosinase in a given time interval. There are two new complexes formed by monophenolase activity. One is EoxM and the second one is EmM. EoxM is an active form and converts into EmD, which is primarily an intermediate in the catalytic cycle. The o-quinones products thus formed by these two oxidation cycles can react spontaneously with one another to form oligomers.24,53–56

3. Tyrosinase inhibition

Owing to the essential function of tyrosinase in the tanning process and melanogenesis, many studies describing the identification of TI's from both biological and synthetic sources have been reported. Typically, the activity of TIs is estimated in the presence of a tyrosine or l-dopa substrate, and the activity is evaluated based on dopachrome formation.57–61

3.1. Tyrosinase inhibition mechanism

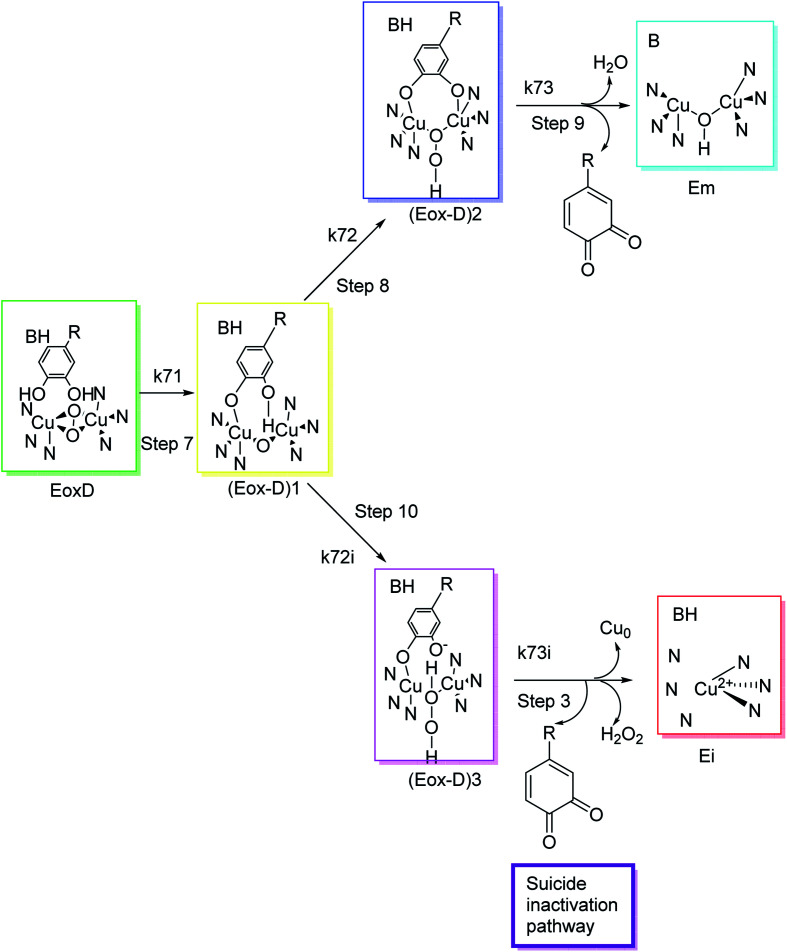

Different classes of compounds can prevent melanogenesis, for example, unique TI's and inactivators, different enzymatic substrates, dopaquinone foragers, non-specific enzyme denaturants, and nonspecific enzyme inactivators attach to the enzyme and hinder its process. Suicide inactivators were commonly registered for the treatment of hyperpigmentation. To describe tyrosinase suicide deactivation (Fig. 3), two pathways have been proposed. In the first pathway, it has been suggested that the conformational changes initiated by the inhibitor's complex in the 3D structures of tyrosinase may rationalize the suicide deactivation. Conversely, in the second pathway, suicide deactivation may take place following the proton transfer to the peroxyl bridge on the oxy-tyrosinase active site.62

Fig. 3. Molecular mechanism of tyrosinase suicide deactivation by oxidation of an o-diphenol substrate. The curly arrows showed that deprotonation results in the reduction of copper from bivalent to zero-valent form, and the elimination of an o-quinone and tyrosinase inactivation.62.

Moreover, to determine the inhibitory mechanism, the IC50 value could be premeditated in the kinetics studies of enzyme and inhibitor's screening to compare the inhibitory strength of an inhibitor with that of a standard and other inhibitors. Though the inhibitory values can be incomparable owing to different assay conditions (various substratum development time, concentrations, and numerous tyrosinase sources), a positive standard could be used for this purpose to normalize values.63,64 Unfortunately, many researchers have not determined IC50 values of novel TIs nor applied positive standards in their research like kojic acid, hydroquinone and arbutin which are typically used as a standards. Though amongst various kinds of TI's, few inhibitors such as azelaic acid, kojic acid, tranexamic acid, ellagic acid and l-ascorbic acid have been identified in cosmetic products as skin-whitening agents. Despite the good safety profile of these drugs, several studies failed to prove their outcome as useful skin lightening agents in clinical trials.65–67

From a structural point of view, the two divalent copper ions that are surrounded by three histidine residues are responsible for the catalytic activity of tyrosinase. A docking study (in silico) revealed that the various TIs expressed their inhibitory potential through hydrophobic π-alkyl, hydrophobic π–σ, hydrophobic π–π T-shaped, and hydrophobic π–π stacked type interactions with His263, Phe264, Ala286, Val283, and His85 amino acid residues inside of the activation loop of targeted tyrosinase biological molecule.52d

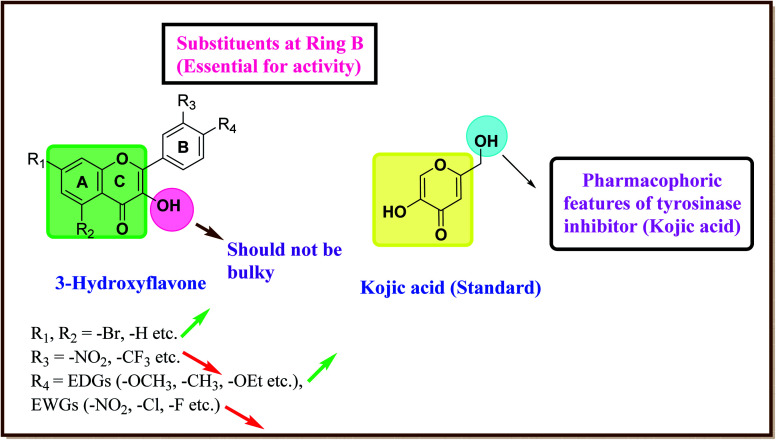

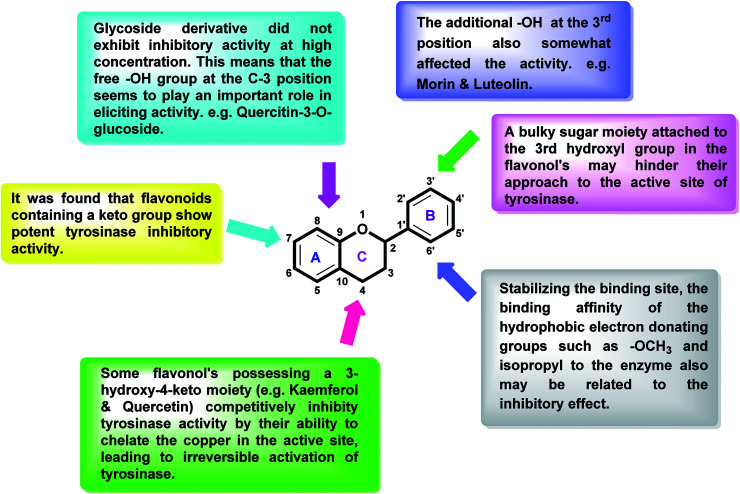

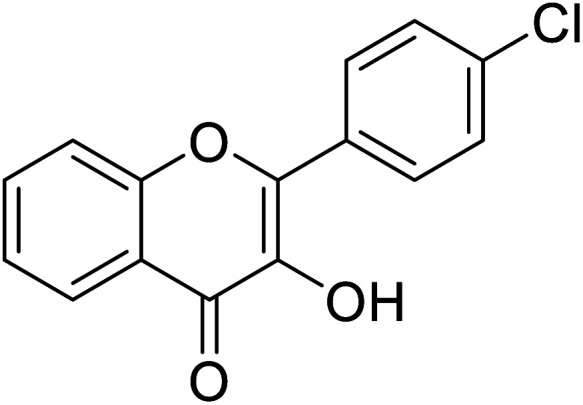

After an extensive structure–activity relationship studies, the SAR data suggest that among all the flavonoid derivatives, the flavonol class stands out and offers the most potent inhibitory activity due to its structural resemblance with that of the standard inhibitor kojic acid. In particular, the phenyl-γ-benzopyran core structure plays a vital role in tyrosinase inhibitory activity. It is noted though that variation in the activity of these inhibitors is attributed to variability in the positions and nature of substituents on the aryl ring (B) as well as the nature of ring B. Introducing halogen atoms into ring A of 2-phenylchromones enhances the electron density along with the hydrophobicity of the molecules and fosters strong bonding interactions. The structure of such inhibitors is therefore customizable and may be tuned to achieve optimum potency. The aforementioned results suggest that 3-hydroxyflavone molecules can serve as fascinating candidates for the treatment of tyrosinase-related ailments and as lead compounds for the development of potent new tyrosinase inhibitors (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Comparative SAR study of the most potent subclass (flavonol) among flavonoids with standard kojic acid. The green arrow indicates increased activity and the red arrow indicates decreased activity.

4. Natural and synthetic sources of inhibitors

4.1. Natural phenolic tyrosinase inhibitors and their sources

Living organisms have developed shielding mechanisms to safeguard against the destructive actions of UV radiations. Hence, nature has a multitude of tyrosinase inhibitor sources. Several investigators have described the isolation of tyrosinase inhibitors from mycological metabolites, plants, and aquatic algae, among other sources. Tyrosinase inhibitors from natural resources commonly attract more interest compared to synthetic ones to meet cosmetic demand and requirements. The IC50 values for the current TI's in the literature are incomparable because of the differences in assay conditions, such as substrate concentration, different time of incubation, and various lots of tyrosinases (Table 1). Henceforth, many researchers have been using the most recognized TI, for example, kojic acid as a standard to adjust and normalize the reported inhibitory activity values.68–72

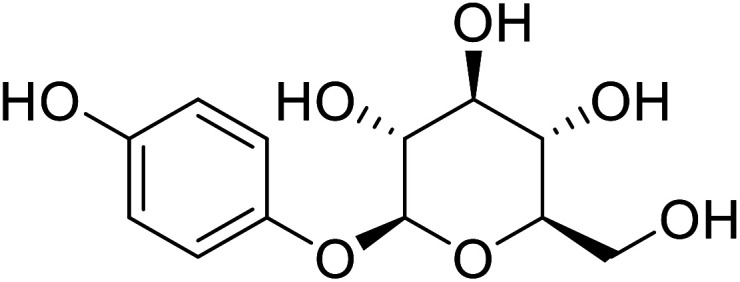

Structures of some mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors36.

| Compound name | Compound structure | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Arbutin |

|

Extracted from the dried leaves of bearberry plant in the genus Arctostaphylos |

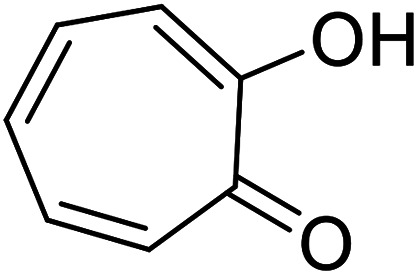

| Tropolone |

|

Isolated from Pseudomonas lindbergii |

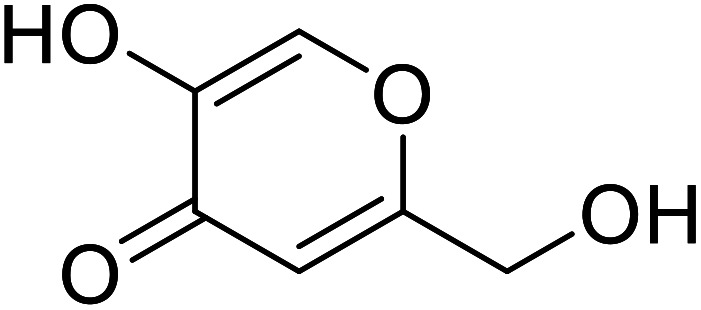

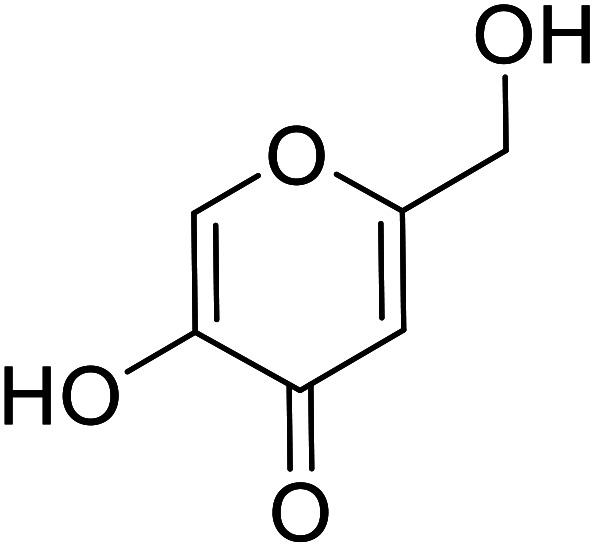

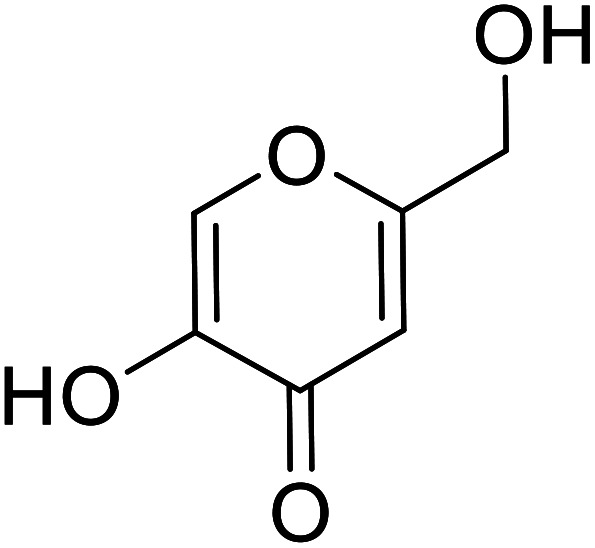

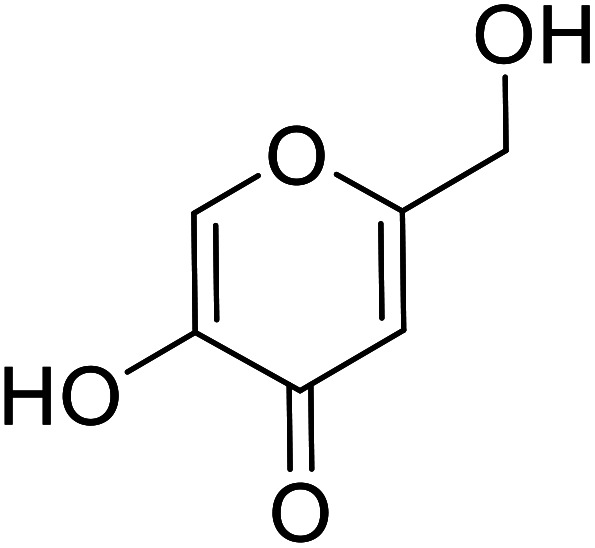

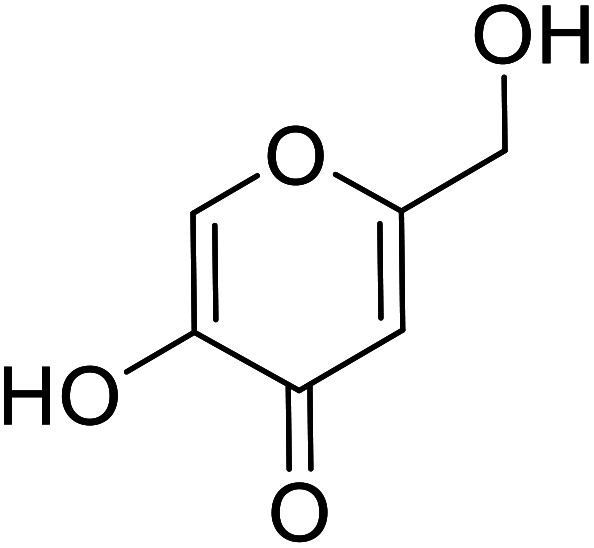

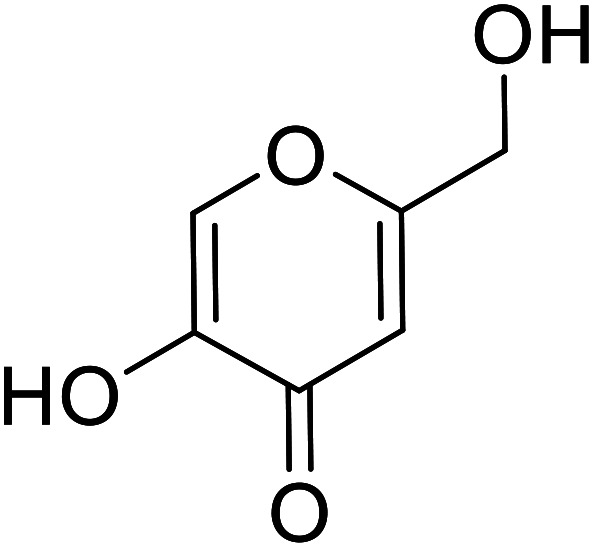

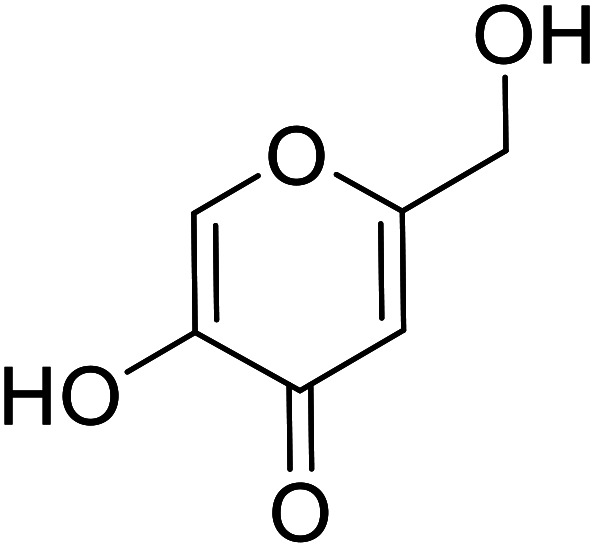

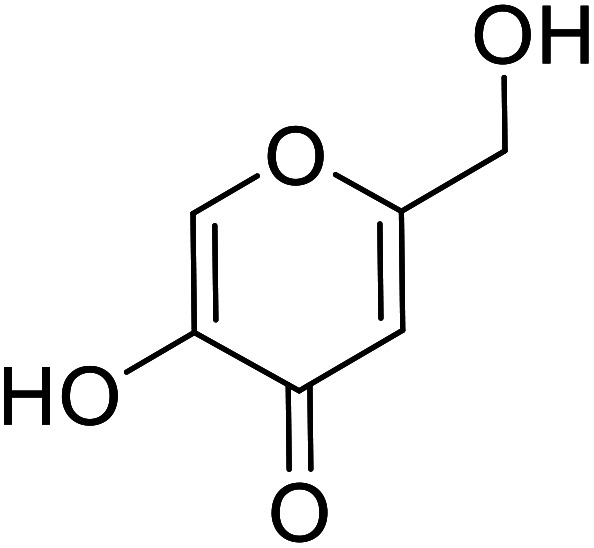

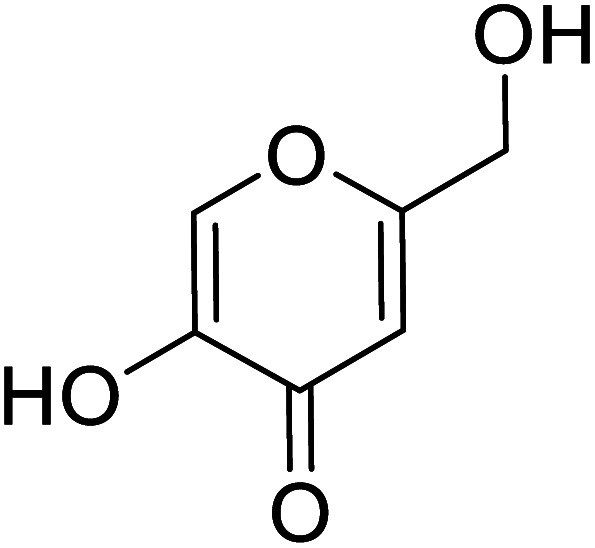

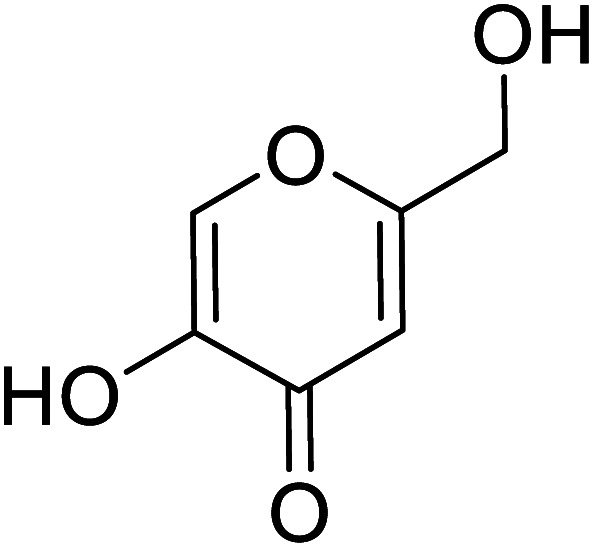

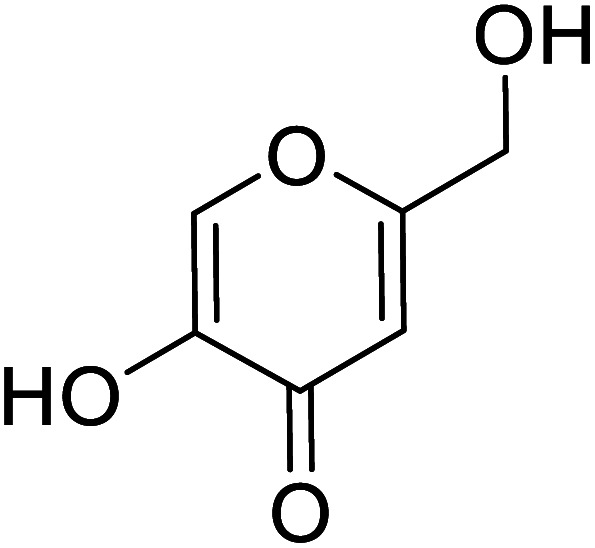

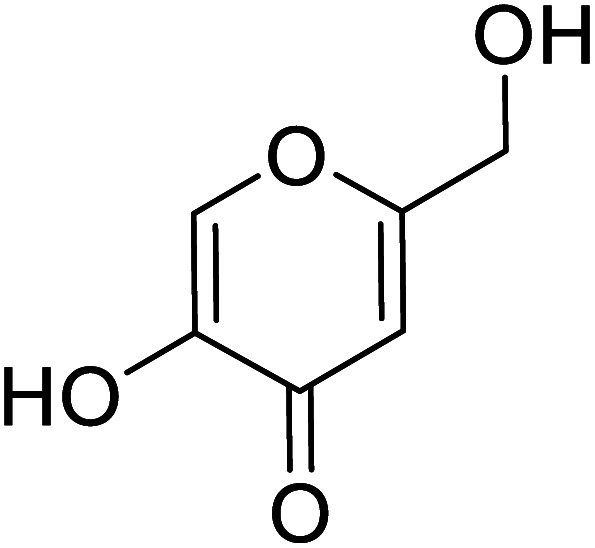

| Kojic acid |

|

Obtained from a few species of Aspergillus |

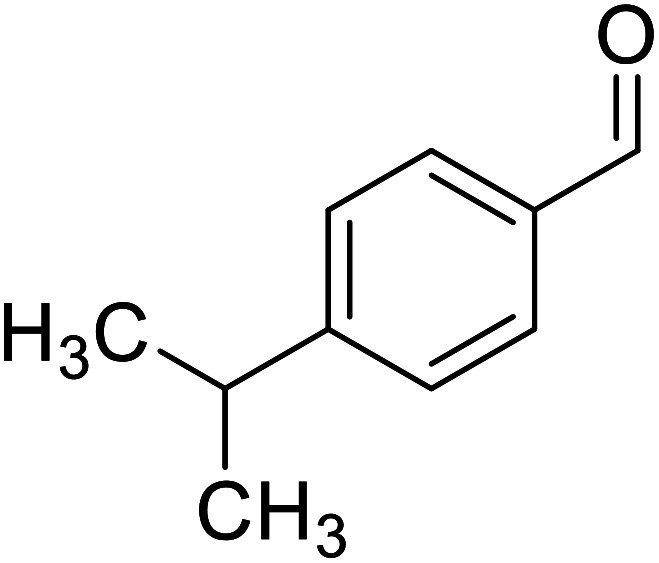

| Cuminaldehyde |

|

Obtained from essential oils |

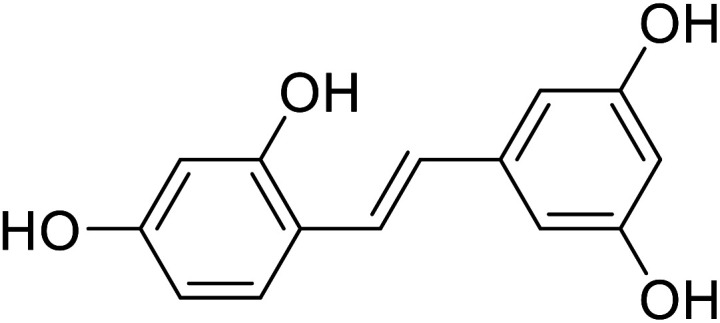

| Oxyresveratrol |

|

Obtained from the extract of heartwood |

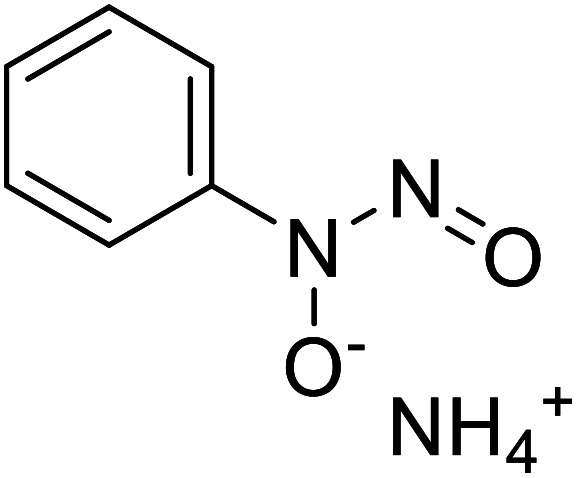

| Cupferron |

|

Obtained from natural samples rich in organic matter |

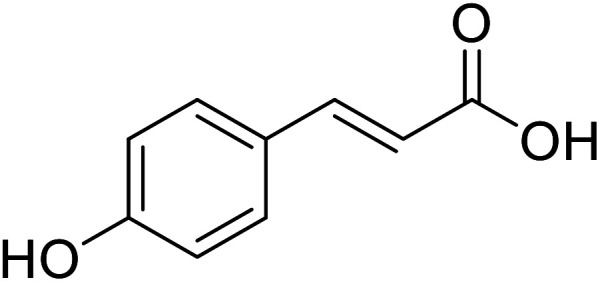

| p-Coumaric acid |

|

Obtained from pollens |

4.2. Synthetic phenolic tyrosinase inhibitors

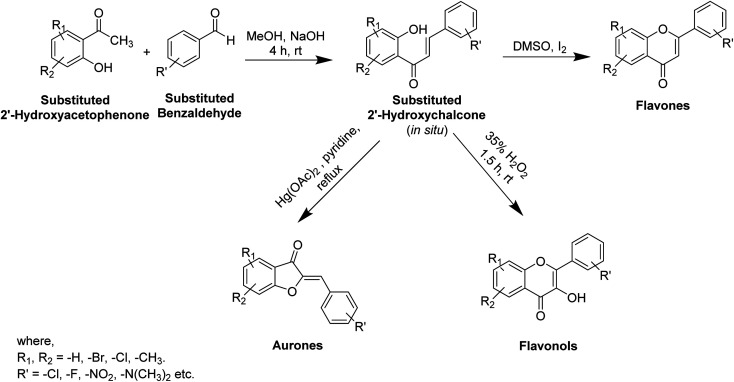

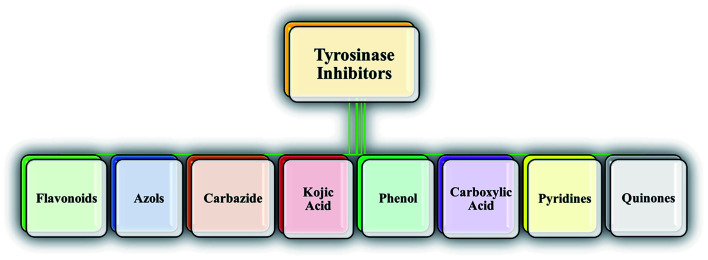

In recent years, numerous studies have addressed the development of new TI's based on natural structural motifs, yet designed to overcome issues related to chemical stability, effectiveness, and isolated yield.9,73 Thus, bioinspired by the various structural scaffolds of natural tyrosinase and the existing research course to design useful synthetic compounds (Fig. 5), synthetic inhibitors with new structural moieties as well as analogs of natural compounds have been synthesized (Scheme 1).74,75

Fig. 5. General structure of flavonoids and relevant pharmacophoric structural features.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of some flavonoids from substituted 2′-hydroxychalcone.

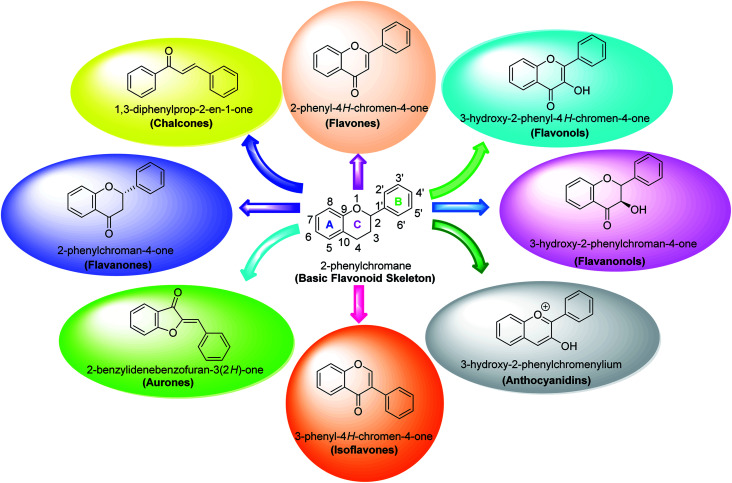

Various potent or weak synthetic (Scheme 1) and natural inhibitors have been reported for tyrosinase.76–78 Flavonoids, the most abundant and commonly studied polyphenols, are benzo-γ-pyrones comprising of pyrene and phenolic rings (Fig. 5). Broadly spread in the flowers, seeds, barks, and leaves, more than 4000 flavonoids have been discovered up to date. Flavonoids are accountable for the distinguished blue and red colors of wines, berries, and a variety of vegetables. Flavonoids can be divided into eight different classes, including aurones, chalcones, flavonols, flavones, flavanols, flavanones, and anthocyanins. Various flavonoid classes are characterized by oxygen-containing five or six-membered heterocyclic rings, and by variation in the position of ring B, and by –OH, –CH3, and –OCH3 groups widely spread in various distinct patterns around the rings.79–81 Besides flavonoids, other polyphenols, which are also known as TIs, include coumarin and stilbenes derivatives (Fig. 6).82 Detailed investigations have proven that few flavonoids are very powerful and effective inhibitors and are discussed in this segment.83–86

Fig. 6. Representative anti-tyrosinase scaffolds.

5. Flavonoids

Flavonoids belong to a class of naturally occurring plant polyphenolic secondary metabolites that are broadly dispersed in the plant kingdom and therefore commonly consumed in diet. Generally, they are identified as compounds having the C6–C3–C6 carbon framework as a core structure consisting of 15-carbon atoms. These often comprise two phenyl rings, designated as A and B, and a heterocyclic ring. Biological studies performed on natural and synthetic analogs of flavonoids have uncovered a considerably broad range of bioactivities manifested by these species which include anxiolytic, anti-microbial, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-ulcer, and thrombosis.85,87–90

Certain flavonoids commonly found in herbs, vegetables, or obtained from synthetic routes, have shown promising prospects as potential TIs among polyphenolic compounds. There is a considerable connection and correlation between the flavonoid's inhibitory potency on tyrosinase and melanin formation in melanocytes.

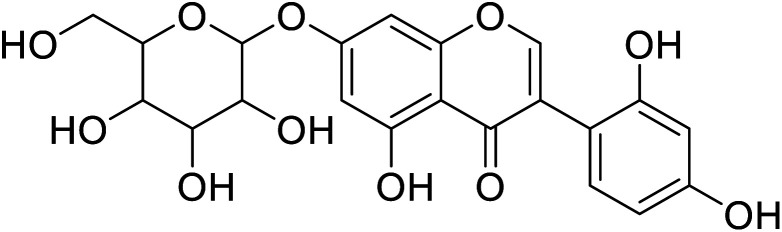

Several flavonoids, extracted from biological resources such as Teretrius nigrescens, Myristica yunnanensis, Pleurotus ostreatus, roots of Morus lhou, and Palhinhaea cernua, herbal plants, and other numerous medicinal plants, were analyzed for their inhibitory action on tyrosinase in the search for effective TI's.91–94 Flavonoids are categorized into various classes, for instance, isoflavones, flavonols, flavanonols, flavanones, flavan-3,4-diols, anthocyanidins, flavones, aurones, and chalcones (Fig. 7). Other flavonoid subclasses include vinylated and acetylated flavonoids, as well as their glycosides. Few flavonoid glycosides such as myricetin galactoside and quercetin galactopyronaside from Epilobium tetragonum have been examined for their TI activities. Remarkably, it has been revealed that far IR irradiation can increase the TI activity of certain flavonoid glycosides.95–103 In a review of recent findings, Orhan et al. surveyed many tyrosinase inhibitors incorporating the flavonoid scaffold.104 Many promising TI's from different classes of natural and synthetic flavonoids have been summarized and the role of flavonoids has been highlighted and recommended as the focus of future and continued tyrosinase inhibition studies.

Fig. 7. Various sub-classes of flavonoids.89.

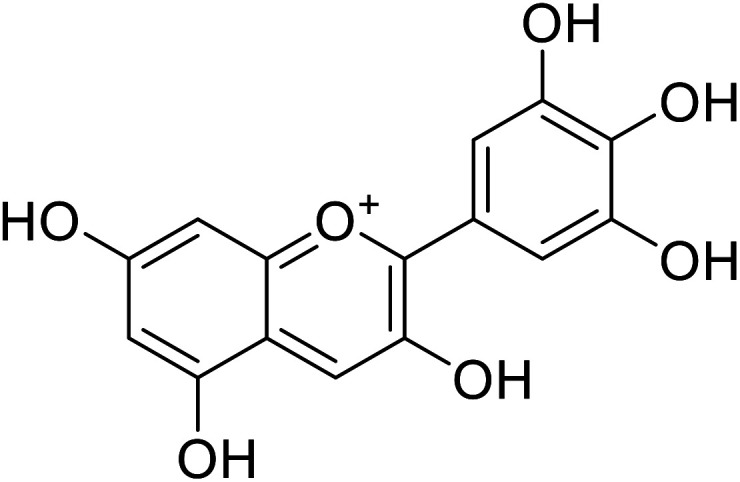

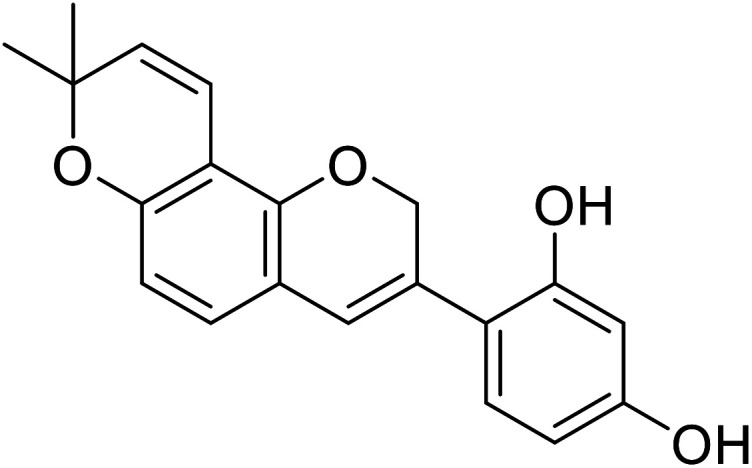

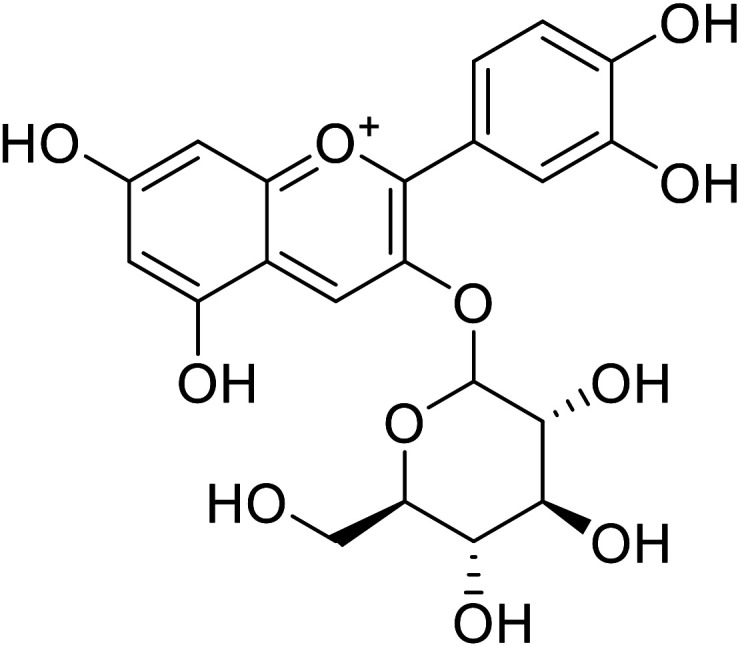

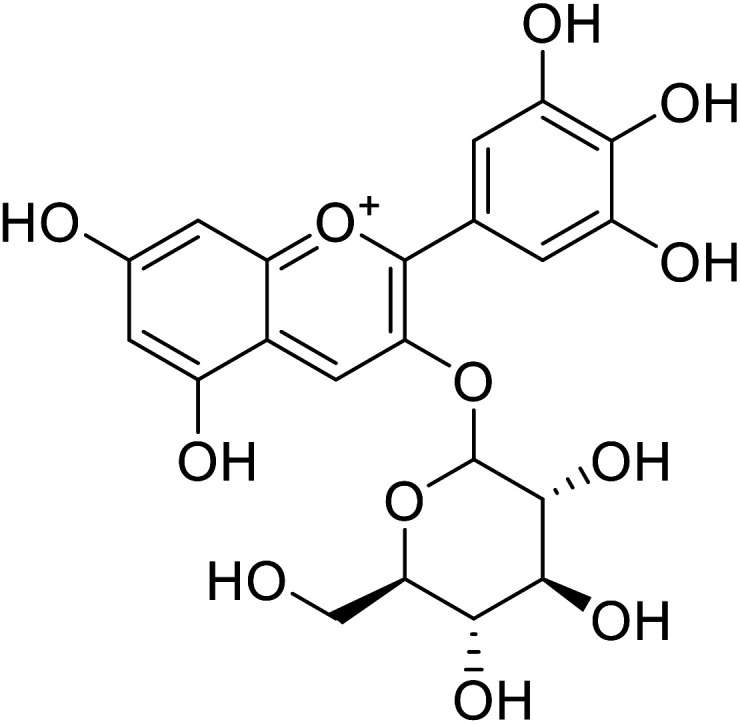

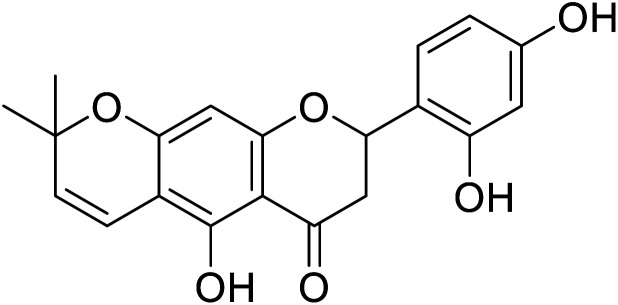

5.1. Anthocyanidins

Anthocyanin, also known as common sugar-coupled anthocyanidin, is a flavonoid found in plants and is accountable for the bright color of vegetables and fruits. It has wound healing and antioxidant properties. Anthocyanin is a naturally occurring pigment that can lessen excess free radicals in the body and can decrease the risk of cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn., an annual herbaceous shrub, is an exceptional resource of anthocyanin. Toxicity reports indicated that anthocyanin from Hibiscus sabdariffa can shield rat liver from the poisoning and destructive effect of tert-butyl hydroperoxide due to the antioxidant action of the former species. Still, there is no evidence that anthocyanin from Hibiscus sabdariffa inhibits melanogenesis. However, compounds 4, 6, and 8 (IC50 = 5, 0.09, and 7.5 μM) in Table 2 have shown excellent tyrosinase inhibitory activities.

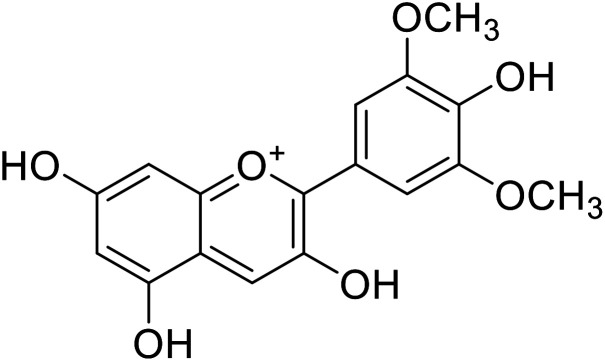

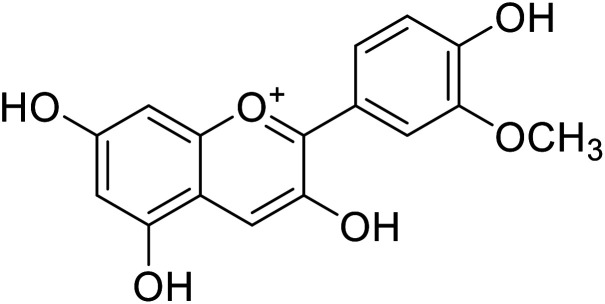

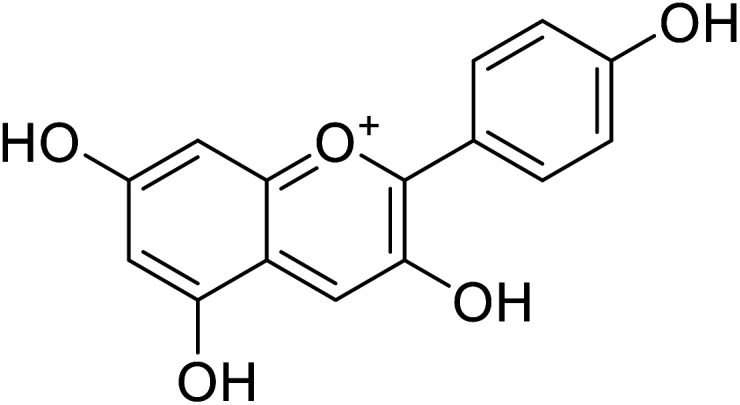

Chemical structures of natural anthocyanidins and IC50 values against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Malvidin |

|

45 | 31 |

| 2 | Peonidin |

|

22 | 31 |

| 3 | Pelargonidin |

|

78 | 31 |

| 4 | Haginin A |

|

5.0 | 31 |

| 5 | Delphinidin |

|

20.9 | 31 |

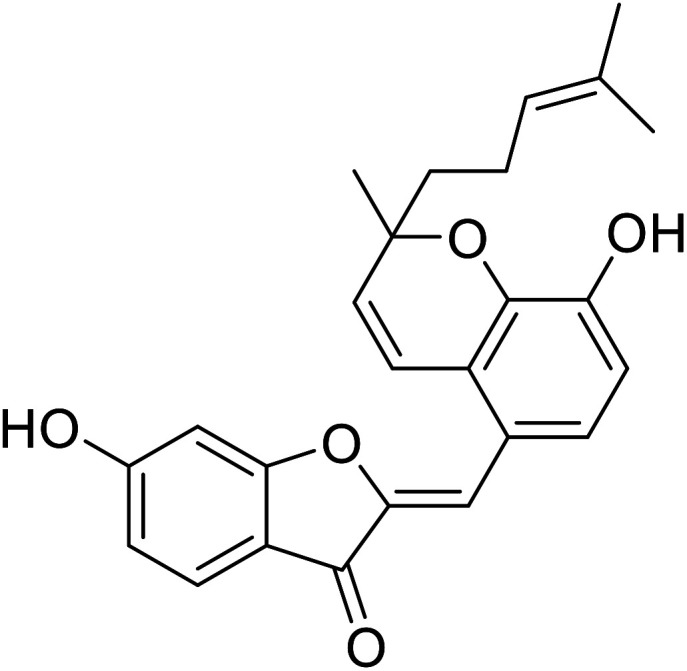

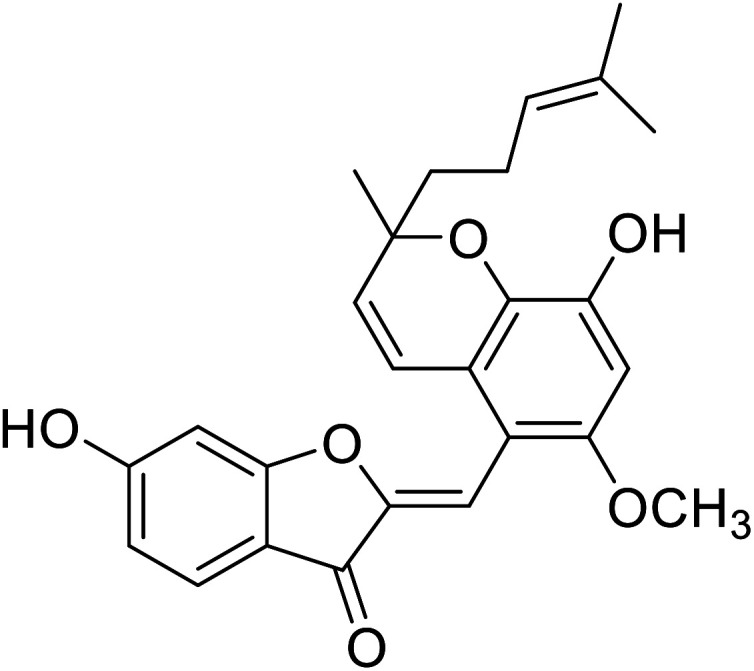

| 6 | 4-(8,8-Dimethyl-2H,8H-pyrano[2,3-f]chromen-3-yl)benzene-1,3-diol |

|

0.09 | 31 |

| 7 | Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside |

|

18.1 | 140 |

| 8 | Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside |

|

7.5 | 31 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

59.3 | 31 and 140 |

Anthocyanin molecules are highly unstable and prone to degradation because they are charged. The anthocyanin color persistency is influenced by temperature, presence of enzymes, pH, light, concentration, structure of the anthocyanin, and the existence of complex derivatives such as other phenolic acids, flavonoids, and metals. Anthocyanin has excellent antioxidant impacts but is susceptible to the effect of biological factors. Hence, encapsulating anthocyanin in liposomes will effectively extend the half-life of anthocyanin (Table 2).105 At the moment and to the best of our knowledge, there is no literature available on synthetic anthocyanins as mushroom TIs.

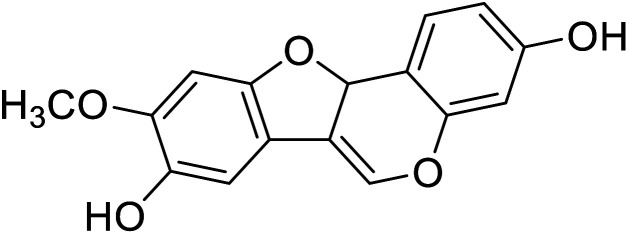

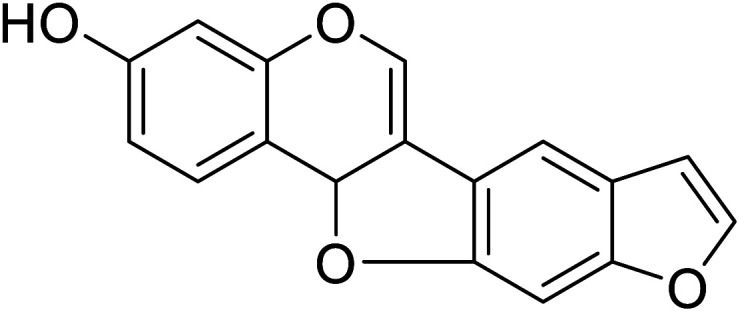

5.2. Aurones

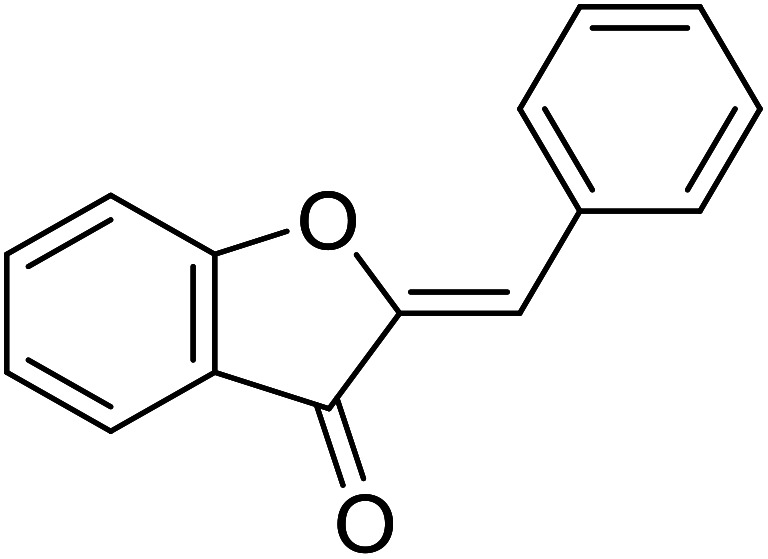

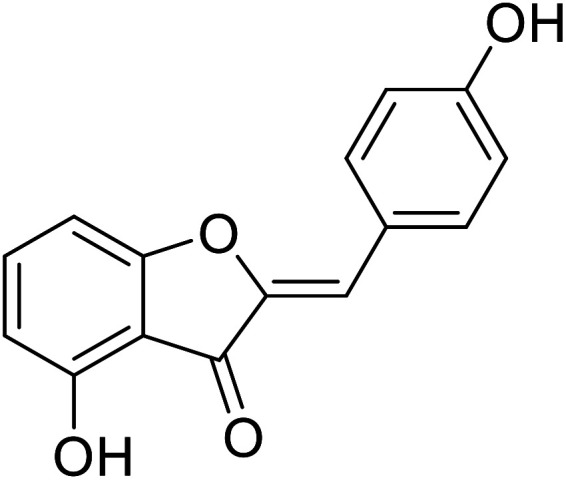

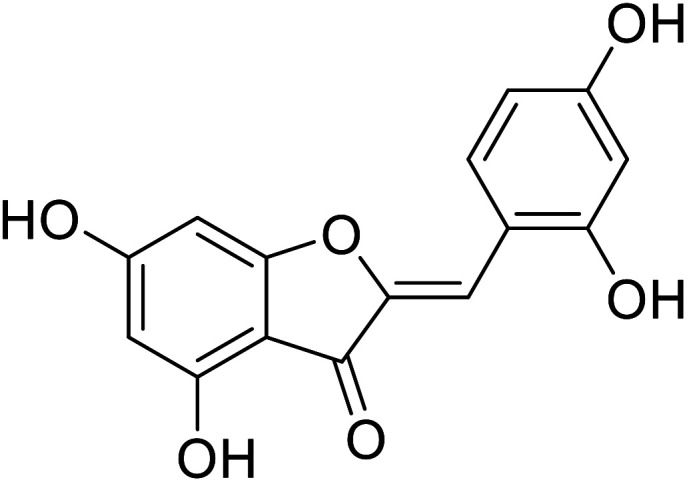

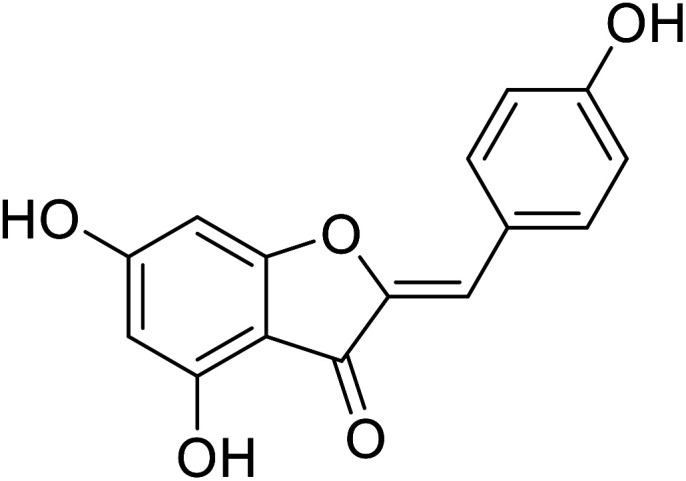

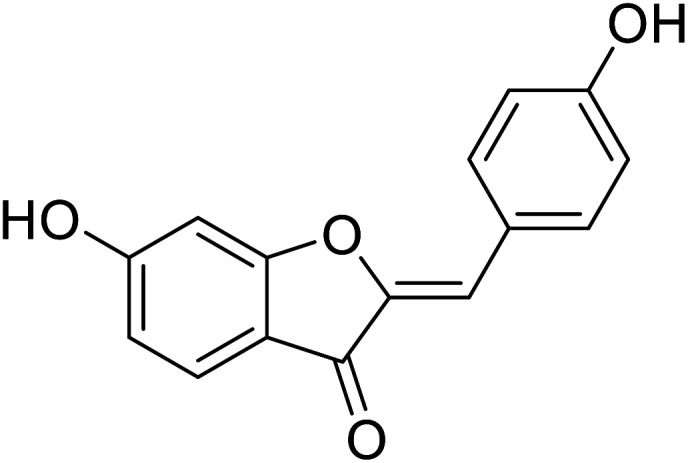

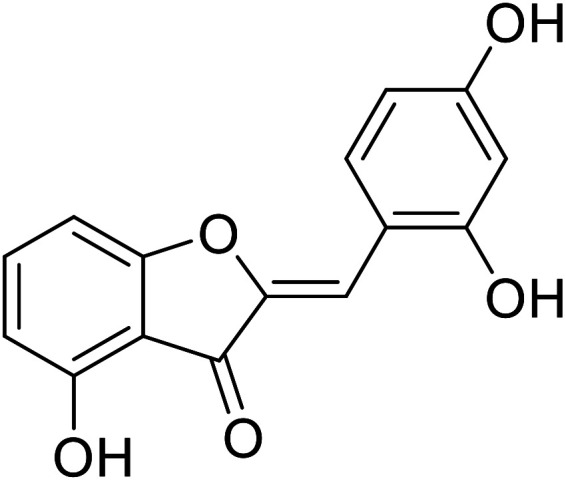

Aurone itself is a weak inhibitor of the tyrosinase enzyme, but its synthetic derivatives that contain more than two –OH groups residing at the 4′, 4, and 6 positions are more potent TI's. Researchers found that natural aurones are most effective against human tyrosinase. Synthetic aurone derivatives like 2-benzylidenebenzofuran-3(2H)-ones and 2′,3′-dihydro-2′-(1-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)-2,6′-dibenzofuran-6,4′-diol are also important TI's.106

Aurones, natural as well as their synthetic analogs, show a broad array of bioactivities such as antimicrobial, antileishmanial, and anticancer. However, these natural biologically active analogs are also specified for their inhibitory action against many kinds of proteins and enzymes. Particularly, natural 4,6,4′-trihydroxyaurone has been recognized as a highly effective inhibitor against human melanocyte-tyrosinase as shown in Table 3. In contrast with the known standard kojic acid, an excellent inhibitor of mushroom tyrosinase, 4,6,4′-trihydroxyaurone showed even superior inhibitory results.107,108

Chemical structures of natural aurones and IC50 values against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

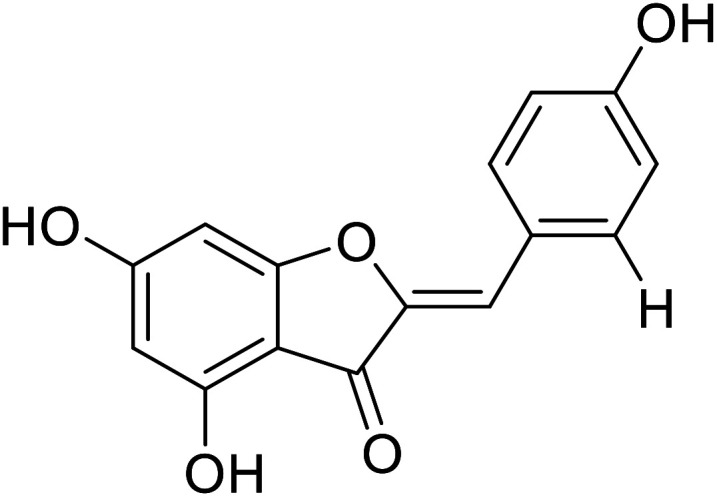

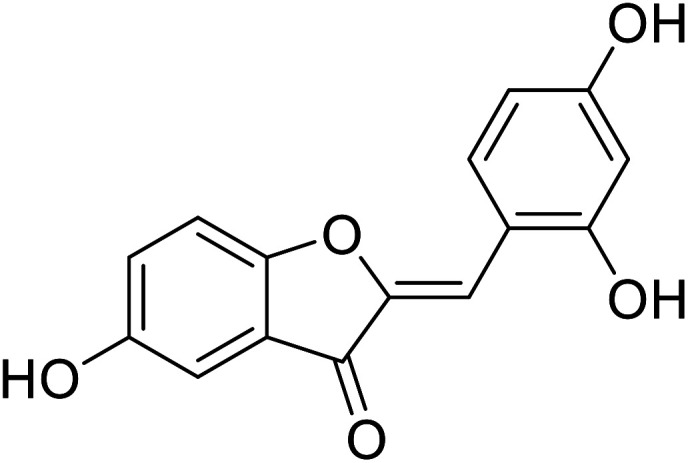

| 9 | 4,6,4′-Trihydroxyaurone |

|

38 | 35 |

| 10 | Altilisin J |

|

98.5 | 107 |

| 11 | Aurone |

|

12.3 | 31 |

| 12 | Altilisin H |

|

85 | 107 |

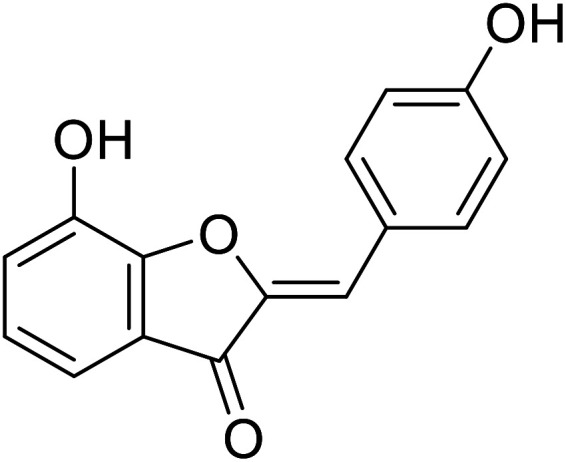

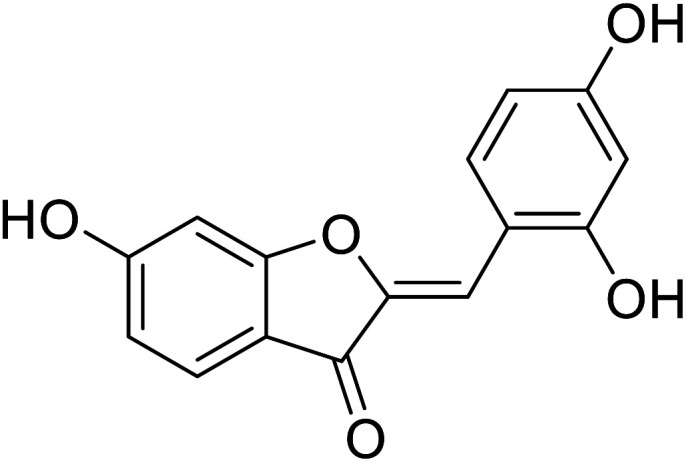

| 13 | 7-Hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzylidene) benzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

31.7 | 106 |

| 14 | 5-Hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzylidene) benzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

38.4 | 106 |

| 15 | Altilisin I |

|

88.9 | 107 |

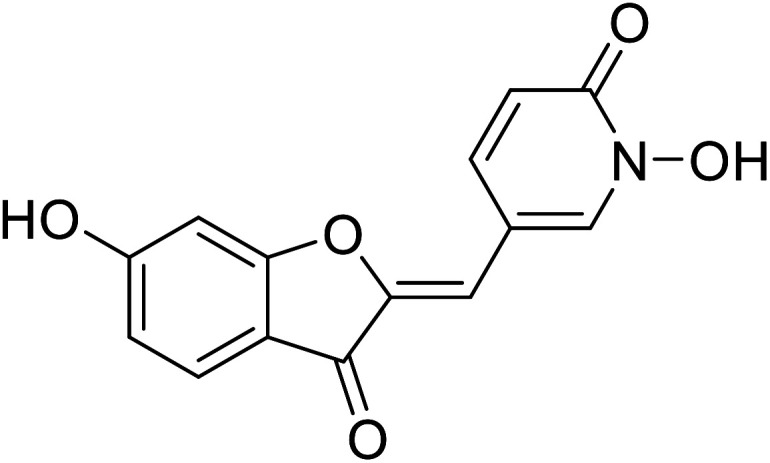

| 16 | 2-Hydroxypyridine N-oxide aurone |

|

1.5 | 111 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

167 | 107 and 111 |

Aurone and its derivatives were discovered as human tyrosinase inhibitors by Okombi et al. Moreover, they recognized that aurones themselves are weak blockers, yet their analogs with more than three –OH groups, usually at the 4′, 4, and 6 positions, are potent TI's. For example, the most active aurone, compound 9 (Table 3), causes 75% inhibition at 0.1 mM concentration and is very efficient compared to the standard kojic acid.108

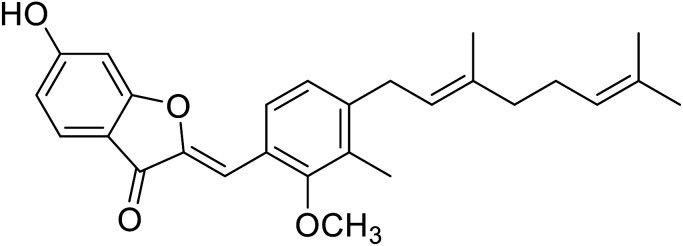

N. T. Mai and his colleagues (2012) have reported three new aurones (compounds 10, 12, and 15) isolated from a plant, Artocarpus altilis (Moraceae), which is broadly distributed over the tropical regions of Asia.109 The isolated compounds were tested for their tyrosinase inhibitory activity (Table 3). The assay was carried out at five different concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 μM for tyrosinase inhibition. All compounds possessed tyrosinase inhibitory activity with IC50 values less than 100 μM. Among them, compounds 12 and 15 showed more potent activities with IC50 values of 85 μM and 88.9 μM, respectively. The results showed that these derivatives had an excellent tyrosinase inhibitory activity.

Dubois et.al. (2012) showed that the most potent aurones were those bearing a –OH group at the 4′-position of ring B. Believing that aurones interact with the binuclear Cu2+ active site through this ring, they surveyed aurones in which the position of the –OH group on the A ring is fixed in the 6th position. Compound 16 (IC50 = 1.5 μM) was found to promote l-DOPA oxidation, which is mediated by tyrosinase. This particular finding indicated that 2-benzylidenefuran can either act as substrates or as hyperbolic activators.110

Among the synthesized aurone analogs, the one in which B-ring is substituted with a HOPNO group, compound 16 has been determined as an efficient and novel mushroom tyrosinase inhibitor. The hybrid aurone 16 has been constructed by combining an aurone moiety with 2-hydroxypyridine N-oxide, an excellent metal chelate.

In 2014, 24 different substituted hydroxylated aurones were synthetically prepared by R. Haudecoeur and his coworkers to evaluate their repressing action towards bacterial and mushroom tyrosinases. The inhibitory behavior of the chemical derivatives depended highly on the hydroxylation patterns of rings A and B and the type of tyrosinase used. Among the new derivatives, 2′,4′-dihydroxyaurones were recognized as the best effective mushroom and bacterial TI's. The presence of hydroxy groups in compounds 18, 19, and 22 at 4,4′; 6,4′; or 4,6,4′ positions was found to be critical for excellent tyrosinase inhibitory potencies in hydroxylated aurones. Based on the aforementioned findings, compounds 18, 19, and 22 were evaluated for their IC50 and proved much stronger and better inhibitors (Table 4) than kojic acid (IC50 = 280 μM) and arbutin (IC50 = 8.4 μM).111

Chemical structures of synthetic aurones and IC50 values against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | 2-(2,4-Dihydroxybenzylidene)-5-hydroxybenzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

>1000 | 106 |

| 18 | 2-(2,4-Dihydroxybenzylidene)-6-hydroxybenzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

>1000 | 106 |

| 19 | 4-Hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)benzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

31.7 | 31 |

| 20 | 2-(2,4-Dihydroxybenzylidene)-4,6-dihydroxybenzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

300 | 106 |

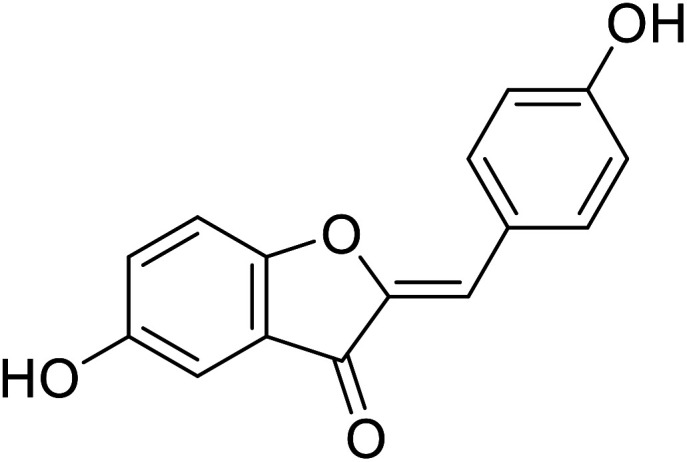

| 21 | 4,6-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)benzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

38.0 | 111 |

| 22 | 6-Hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)benzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

38.4 | 31 |

| 23 | 2-(2,4-Dihydroxybenzylidene)-4-hydroxybenzofuran-3(2H)-one |

|

9 | 106 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

280 | 31, 106 111 |

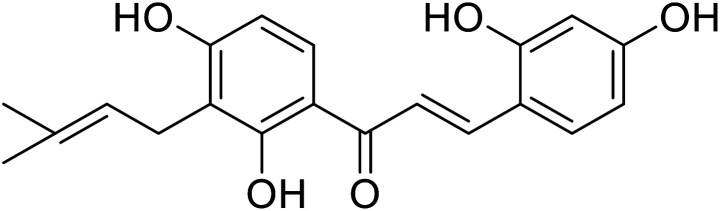

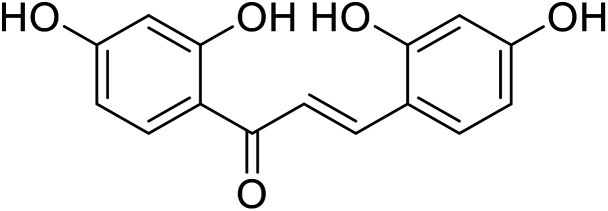

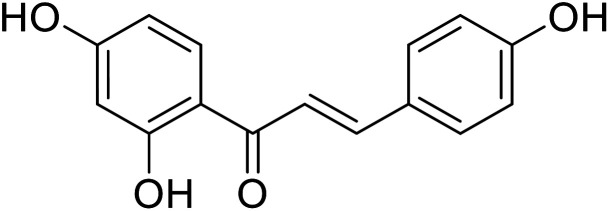

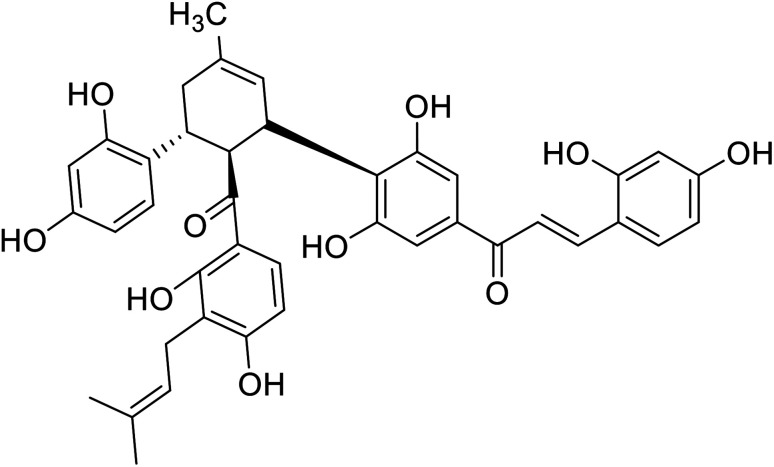

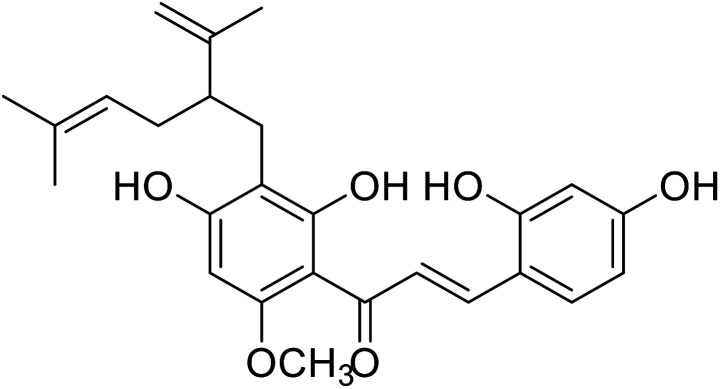

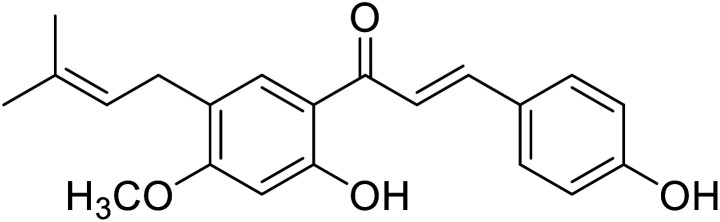

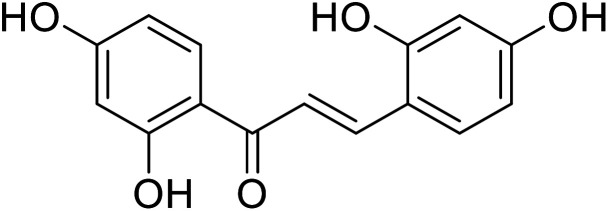

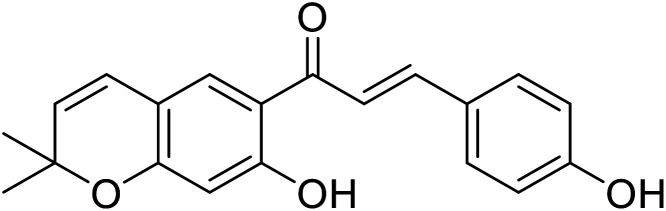

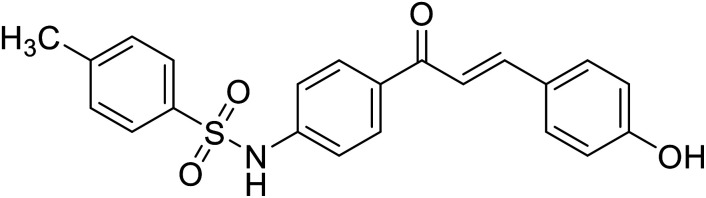

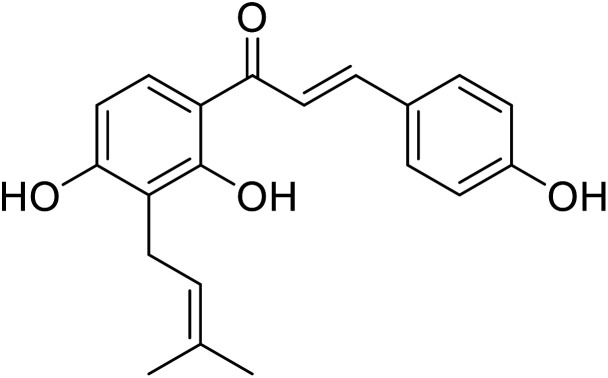

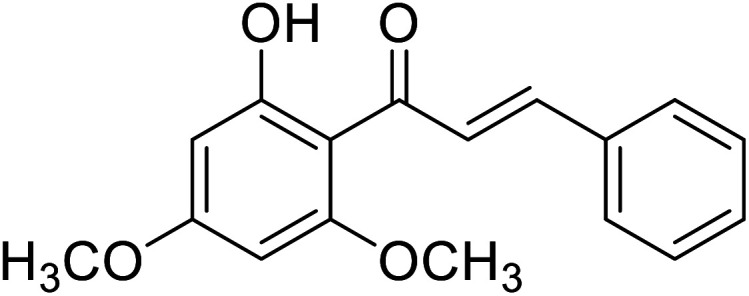

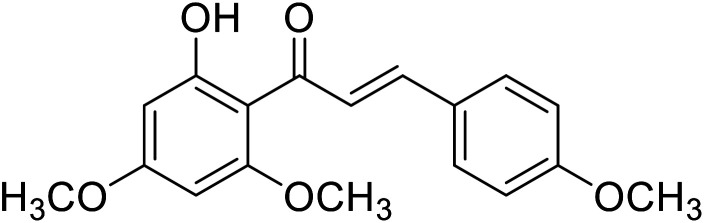

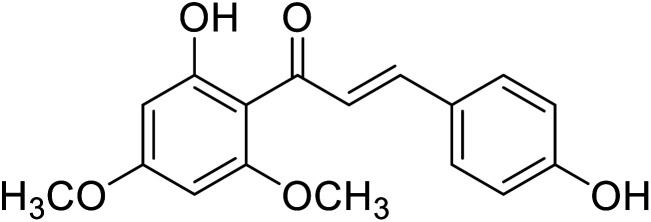

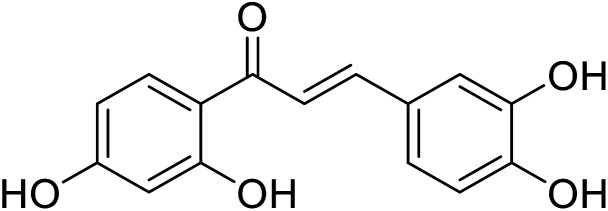

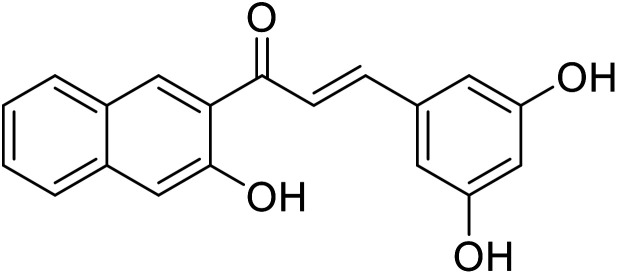

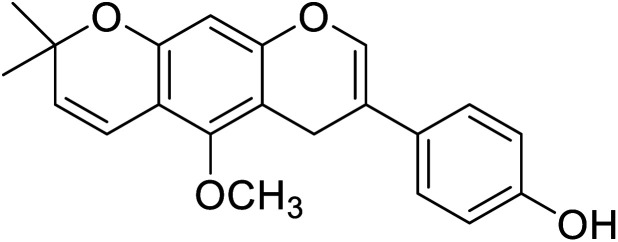

5.3. Chalcones

Chalcones are comprised of two trans-configured aryl rings, separated by 3C atoms, two of which are covalently bonded by a double bond ( ) and the third is a carbonyl (C O) functionality. Several natural acylated chalcones show potent tyrosinase inhibitory properties. Their aromatic rings are substituted with different functional groups: –OH, –OCH3, –R, and these substituents impact the bioactivities of chalcones. Several chalcones described in the literature show good tyrosinase inhibitory activity.8,58,112

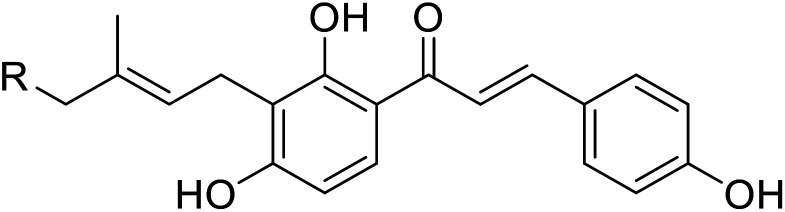

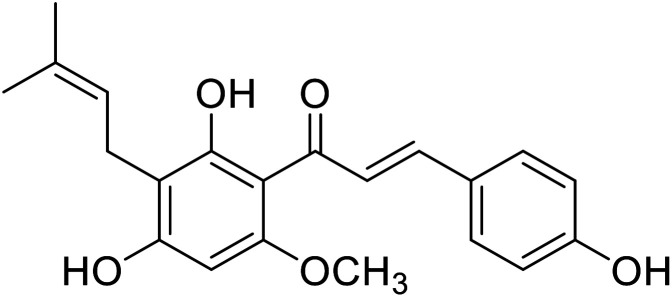

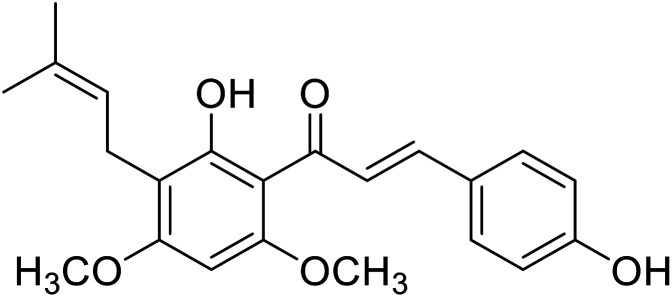

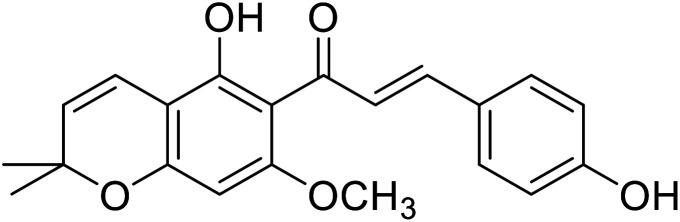

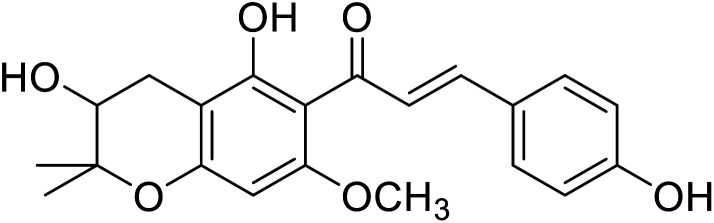

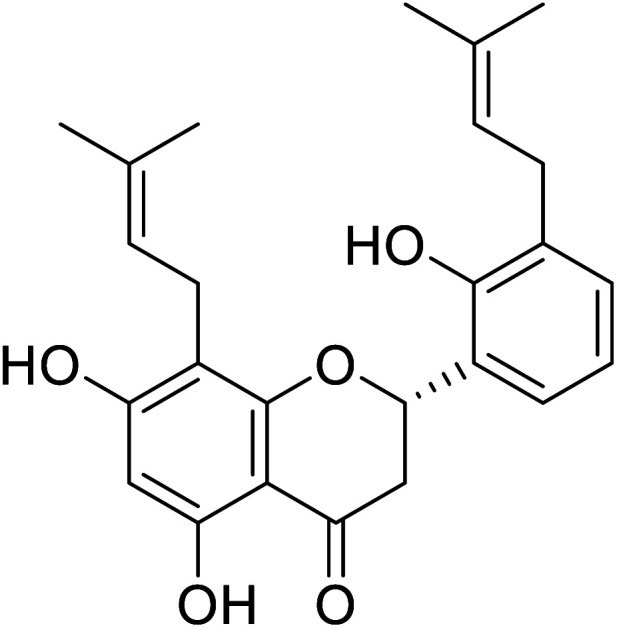

Khatib and colleagues discovered that mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra-substituted hydroxychalcones could inhibit tyrosinase. Compound 28 (Table 5), a prenylated chalcone isolated from the plant Sophora flavescens, was highly potent as it exhibited 34 fold activity compared to that of a standard against mushroom tyrosinase monophenolase. More intriguing, the two prenylated chalcones also showed higher activity than their flavanone analogs.27,96,97 Kuraridin (a chalcone) was 10 times more active than kurarinone (a flavanone). Compounds 28 and 24 produced 34- and 26-fold TI activities than kojic acid, respectively (Table 5).

Chemical structures of natural chalcones and IC50 values obtained against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 2,4,2′,4′-Tetrahydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)-chalcone (TMBC) |

|

0.95 | 118 |

| 25 | 2,2′,4,4′-Tetrahydroxychalcone |

|

0.07 | 113 |

| 26 | Isoliquiritigenin |

|

4.85 | 36 |

| 27 | Kuwanon J |

|

0.17 | 36 |

| 28 | Kuraridin |

|

0.6 | 27 |

| 29 | Isobavachromene |

|

15.8 | 134 |

| 30 | Morachalcone A |

|

0.14 | 112 |

| 31 | 4′-O-Methylbavachalcone |

|

48.8 | 134 |

| 32 | 4'-(p-Toluenesulfonylamino)-4-hydroxychalcone |

|

23.3 | 36 |

| 33 | Isovabachalcone |

|

12.3 | 134 |

| 34 | Artocarmitin C |

|

20.6 | 135 |

| 35 | Flavokawain B |

|

14.38 | 29 |

| 36 | Flavokawain A |

|

14.26 | 29 |

| 37 | Xanthohumol |

|

15.4 | 30 |

| 38 | 4′-O-Methylxanthohumol |

|

34.3 | 134 |

| 39 | Xanthohumol C |

|

41.3 | 30 |

| 40 | Xanthoumol B |

|

46.7 | 30 |

| 41 | Flavokawain C |

|

106.7 | 29 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

89.5 | 29, 30, 134 and 135 |

According to Nerya et al.,27 the location of the –OH groups attached to the aryl rings A and B is the most essential structural feature required to produce strong tyrosinase inhibitory activity of chalcones, and there is a substantial preference for p-substituted ring B over substitution at ring A. However, the findings drawn from their recent study revealed conflicting results that chalcones with 2,4-DNPH and resorcinol moieties displayed the greatest tyrosinase inhibitory activity, and the resorcinol subunit on ring B did not contribute effectively to maximize TI action. In the presence of both Cu2+ ions and tyrosinase, the catechol on ring A acted like a metal chelator (in the presence of Cu2+ ions) and a competitive inhibitor (in the presence of tyrosinase), while the catechol on ring B underwent oxidation to the corresponding o-quinone. Compounds 24 and 25 (IC50 = 0.95 and 0.07 μM respectively) are powerful tyrosinase inhibitors.

Likewise, Jun et al.113 synthesized a chalcone series and analyzed their tyrosinase repressive action. The findings were consistent with their prior work,27 and the most active derivative reported was 2,4,2′,4′,6′-pentahydroxychalcone, showing a 5-fold higher activity than 2,4,2′,4′-hydroxychalcone.

Nguyen et al.114 recently isolated acylated flavones and chalcones from the wood of Artocarpus heterophyllus. Compound 30, which had a 3000-fold greater activity than kojic acid, was the most active of the isolated compounds with significant TI activity. Many synthetic derivatives of chalcones were developed as effective candidates of tyrosinase inhibitors,115–117 inspired by their versatile bioactivity and unique structural motif. Some natural and synthetic chalcones, as well as their derivatives, have been reported as new potent depigmenting agents and TI's, according to several studies (Table 6). Up to now, natural chalcone isoliquiritigenin from licorice roots, 2,4,2′,4′-hydroxycalcone and three of its analogs with 3′-substituted resorcinol moieties from Malacosteus australis (Table 5) 2,4,2′,4′-tetrahydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)-chalcone from Morus nigra, 2,4,2′,4′-tetrahydroxychalcone (IC50 = 0.07 ± 0.02 μM) and morachalcone A (IC50 = 0.08 ± 0.02 μM) from Morus alba L. have been designated as tyrosinase inhibitors.115

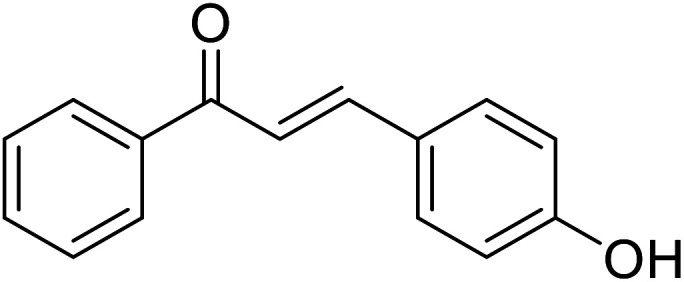

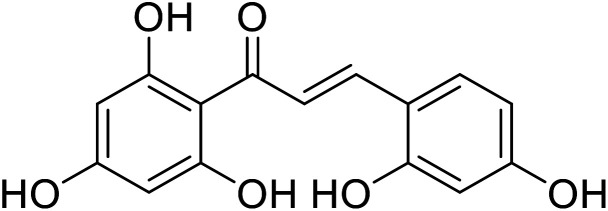

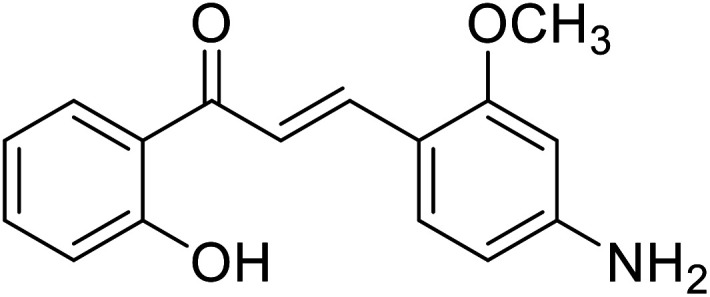

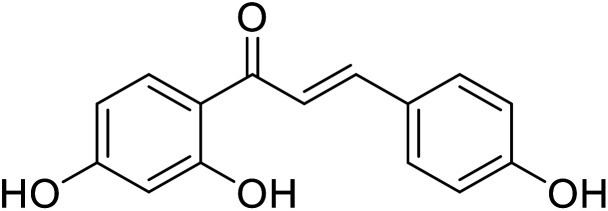

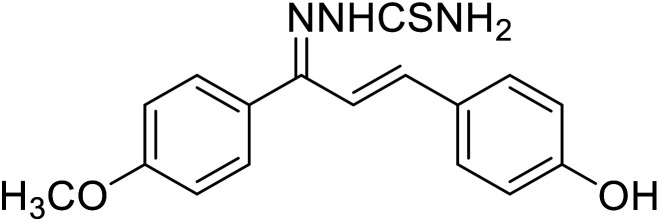

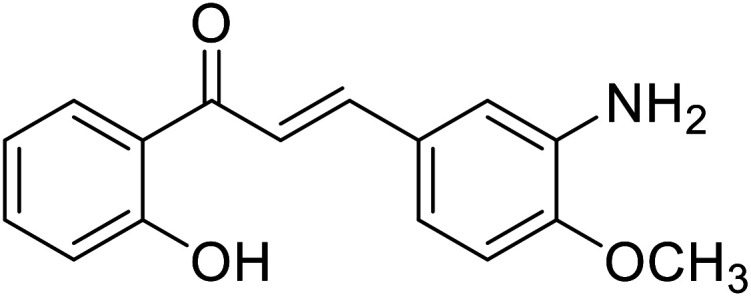

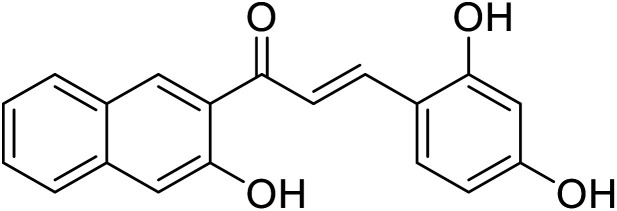

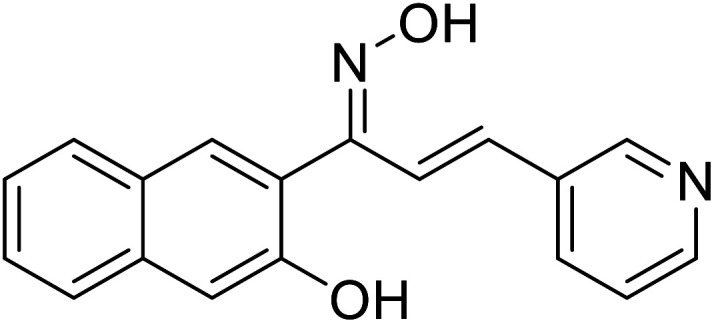

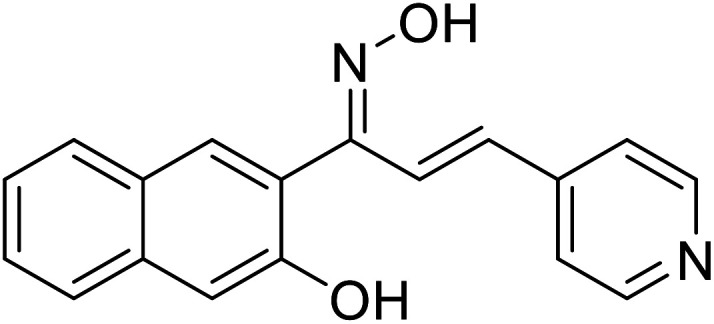

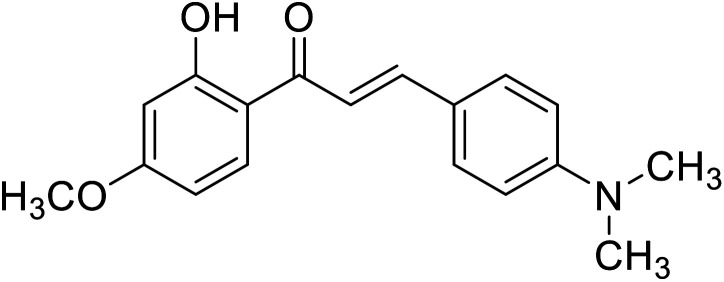

Chemical structures of synthetic chalcones and IC50 values against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

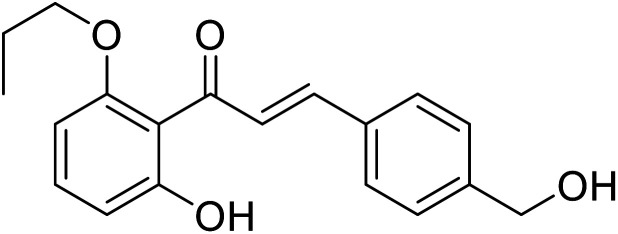

| 42 | 1-(2-Hydroxy-6-propoxyphenyl)-3-(4-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

26.8 | 96 |

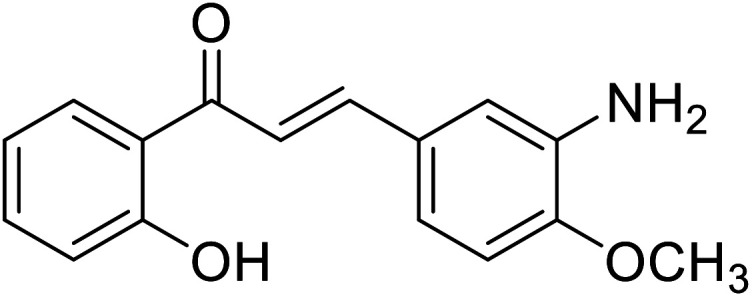

| 43 | 3-(3-Amino-4-methoxyphenyl)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

9.75 | 96 |

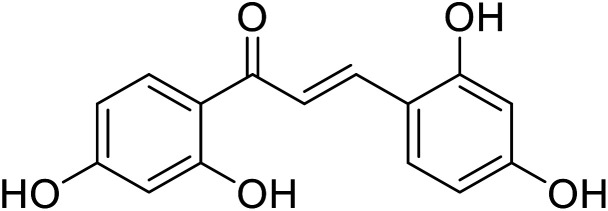

| 44 | 1,3-Bis(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl) prop-2-en-1-one |

|

0.02 | 96 |

| 45 | 3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenyl prop-2-en-1-one |

|

21.8 | 133 |

| 46 | 3-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-1-(2,4,6-trihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

17.6 | 133 |

| 47 | 3-(4-Amino-2-methoxyphenyl)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

7.82 | 112 |

| 48 | 1-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

8.1 | 114 |

| 49 | 1-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

29.3 | 114 |

| 50 | 1-(1-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-3-phenylallylidene) thiosemicarbazide |

|

0.274 | 123 |

| 51 | 3-(3-Amino-4-methoxyphenyl)-1-(2-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

9.75 | 112 |

| 52 | 3-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-1-(3-hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

114.4 | 116 |

| 53 | 3-(3,5-Dihydroxyphenyl)-1-(3-hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

10.4 | 116 |

| 54 | 1-(3-Hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl)-3-(pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-en-1-one oxime |

|

12.22 | 117 |

| 55 | 1-(3-Hydroxynaphthalen-2-yl)-3-(pyridin-4-yl)prop-2-en-1-one oxime |

|

19.45 | 117 |

| 56 | 3-(4-(Dimethylamino) phenyl)-1-(2-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one |

|

14.20 | 112 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

57.9 | 112, 116, 123 and 133 |

Tetrahydroxychalcone and its various derivatives (such as naphthyl chalcones and their thiosemicarbazide) have been described as a novel class of TI's (Table 6). Remarkably, compounds 44, 46, 50, and 54 have shown excellent tyrosinase inhibitory activity due to the presence of –OH groups on rings A and B and the number of –OH groups, while the presence of a catechol group did not correlate with rising tyrosinase inhibition potency.116,117

The synthesized chalcones, compound 47 and compound 51 (Table 6) were proven to be the most potent TIs in a competitive way. Their IC50 values indicated that they were more potent than kojic acid, the reference compound.27,118,119

Nerya et al. reported that chalcones are highly potent new depigmenting agents, with their dual effect of antioxidant activity and reductants.27,120Tables 4 and 5 depict chalcone and its analogs showing anti-tyrosinase behaviors (IC50 values).121–123

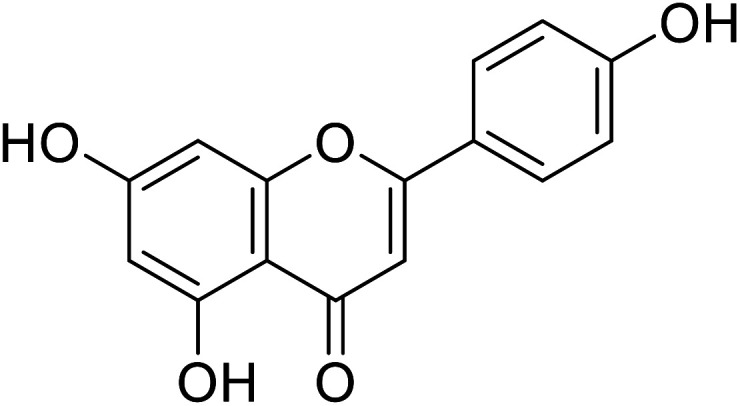

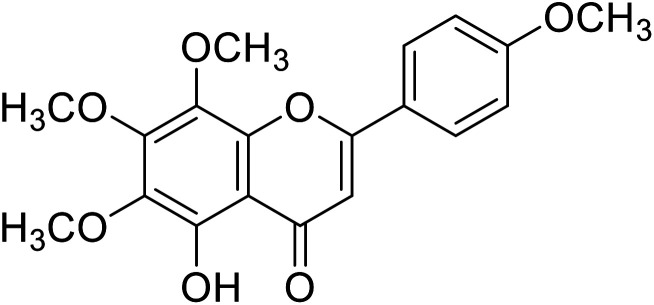

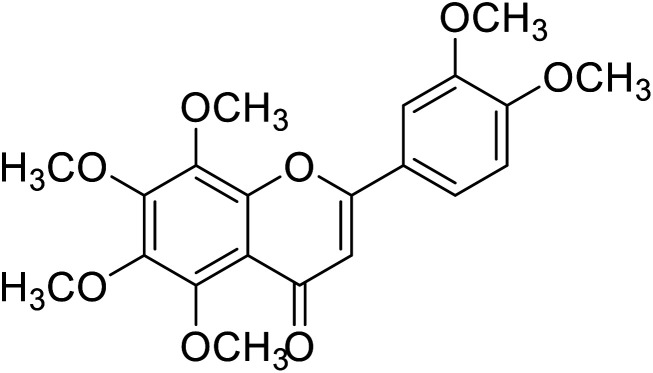

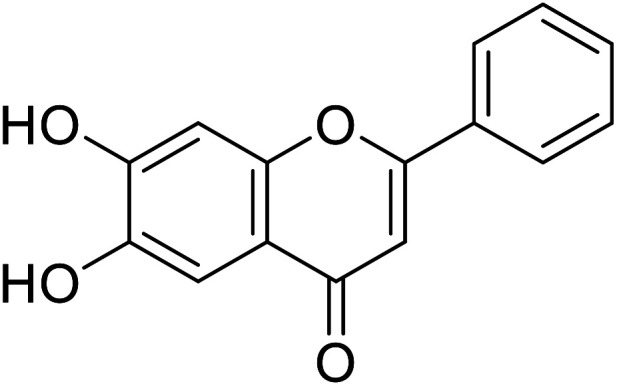

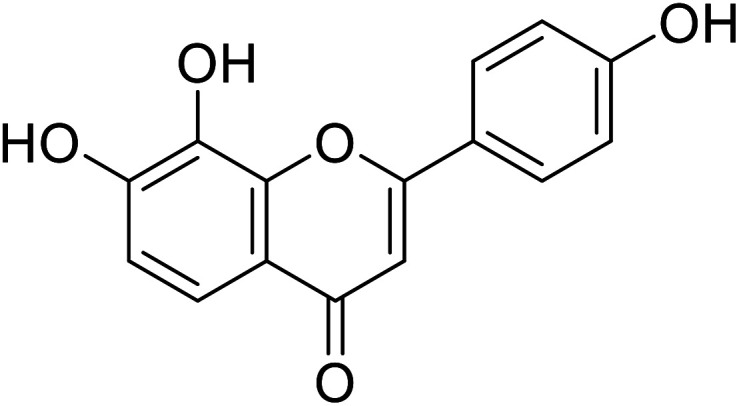

5.4. Flavones

Flavone belongs to the class of flavonoids having a 2-phenylchromen-4-one backbone. They can be found in some yellow and orange fruits and vegetables, as well as spices. Apigenin, lutein, chrysin, and baicalein along with their glycosides, the polymethoxylated flavones tangeretin, and nobiletin, are the most popular flavones.86,87,124 Nguyen et al.114 have studied the occurrence of compounds 60 and 62 from the methanolic extract of Artocarpus altilis with 11 other polyphenolic derivatives for their TI activity.

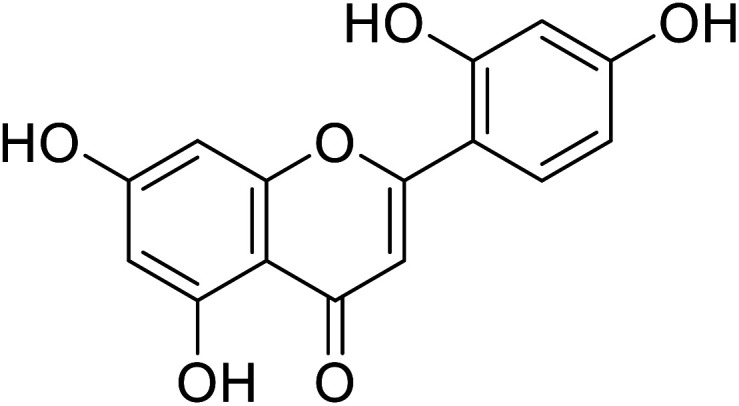

Shang et al.93 discovered a flavone derivative, namely 7,8,4′-trihydroxyflavone, which prevents tyrosinase diphenolase action (Table 7). The proposed binding mechanism involved van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding, according to the thermodynamics parameters. In addition, docking simulations revealed H-bonding between this compound and the active site residues His244 and Met280. Several hydroxyflavones, such as 6-hydroxyapigenin, baicalein, and 6-hydroxykaempferol, and 6-hydroxygalangin have also been shown as inhibitors of tyrosinase diphenolase activity (Table 7). Another active flavone, compound 57 (5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone), has been obtained from the roots and aerial parts of Chrysanthemum morifolium and Oroxylum indicum (Indian trumpet flower) (Table 7). The compound shows tyrosinase inhibition by inducing conformational changes within the structure of the target enzyme.125,126

Chemical structures of natural flavones and IC50 values obtained against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

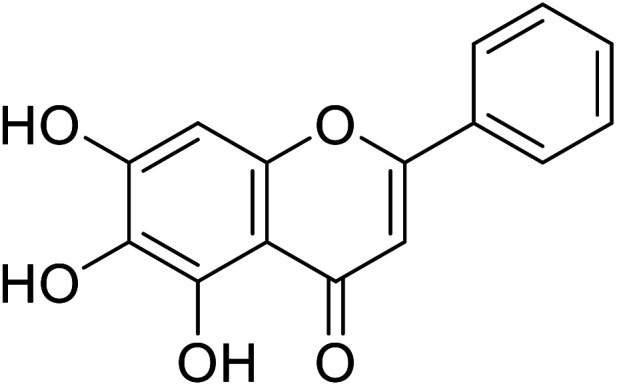

| 57 | Baicalein |

|

110 | 93 |

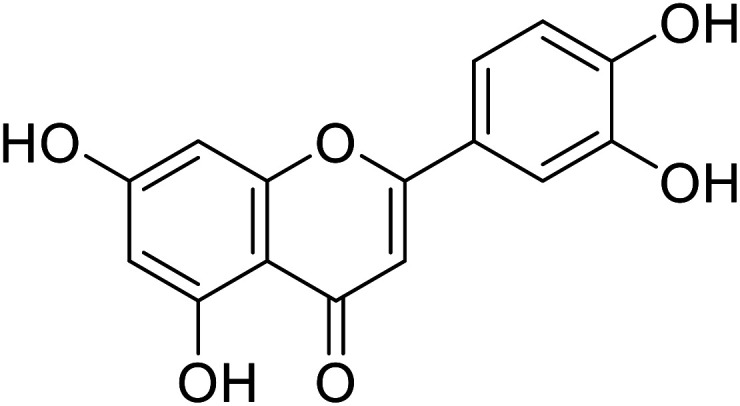

| 58 | Luteolin |

|

20.8 | 30 |

| 59 | Norartocarpetin |

|

1.2 | 86 |

| 60 | Apigenin |

|

17.3 | 30 |

| 61 | Tangeretin |

|

25 | 87 |

| 62 | Nobelitin |

|

29.8 | 124 |

| 63 | 6,7-Dihydroxy-2-phenyl-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

2.8 | 30 |

| 64 | 4′,7,8-Trihydroxyflavone |

|

10.31 | 94 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

78 | 30, 86 and 94 |

Nihong Guo et al. estimated the active site for binding interaction is present at the bottommost cavity of tyrosinase. From docking studies carried out using the same tyrosinase enzyme (PDB: 2Y9X), intermolecular interaction confirmed the binding between tyrosinase and baicalein which effectively produced a docking score of −6.20 kcal mol−1 for binding conformation. Several adjacent residues which include His85, Val 248, Phe264, Met280, Ser282, Val283, and Ala286 foster hydrophobic interaction with the benzene ring and increase the stability of binding interaction. The phenolic hydroxyl group (C-7) of baicalein and the carbamoyl oxygen atom of Met 280 residue form hydrogen bonding which stabilizes the complex. The C-7 hydroxy group was considered very essential for enhancing its inhibitory activity against tyrosinase.127–129

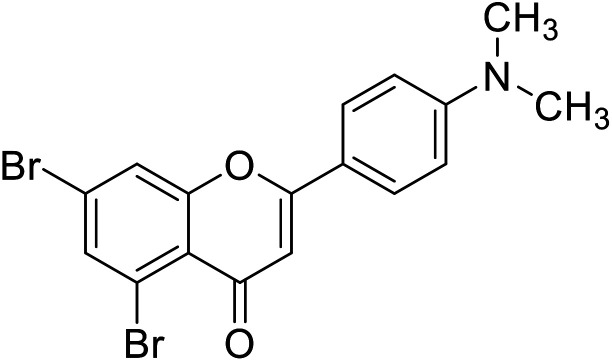

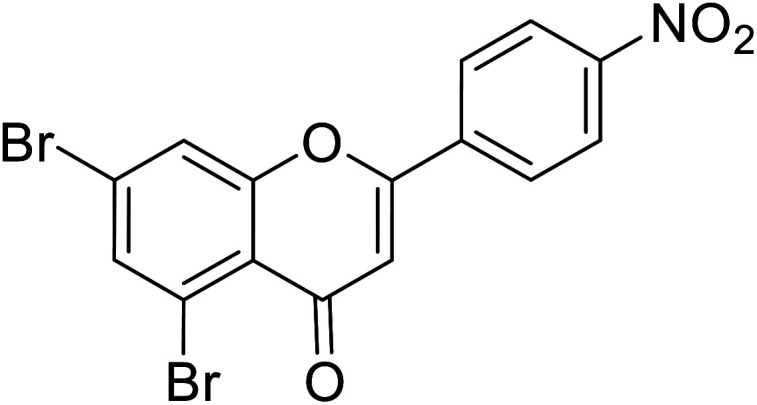

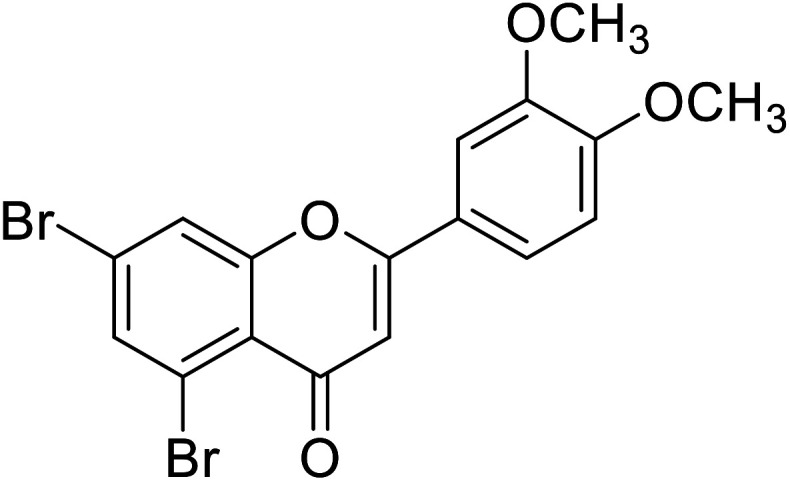

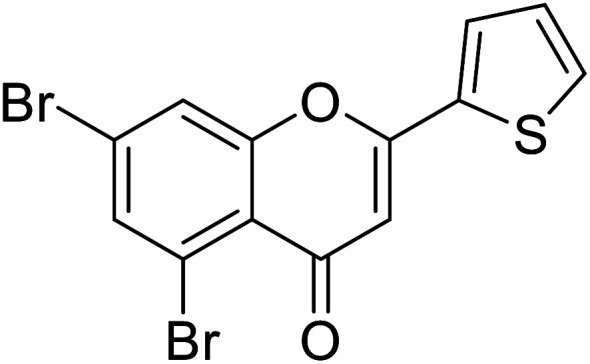

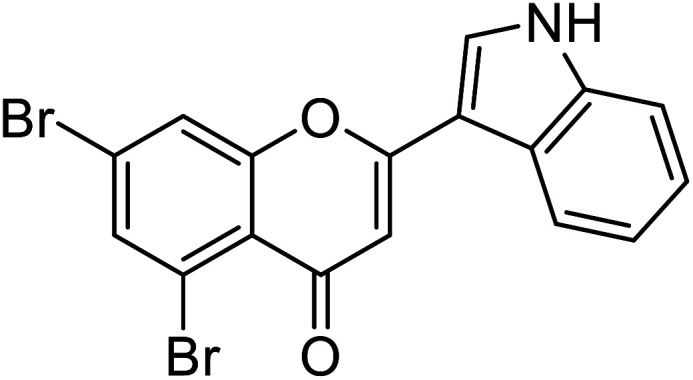

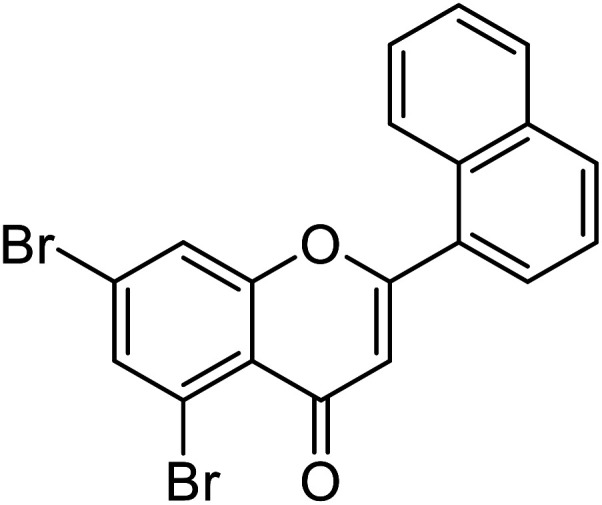

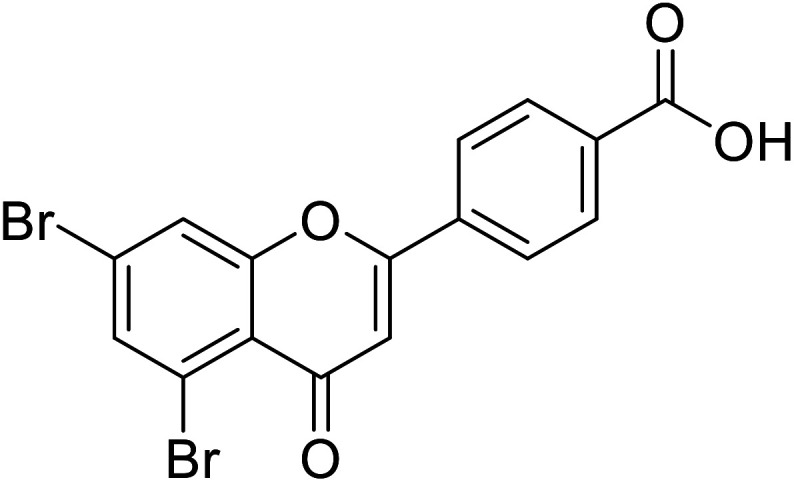

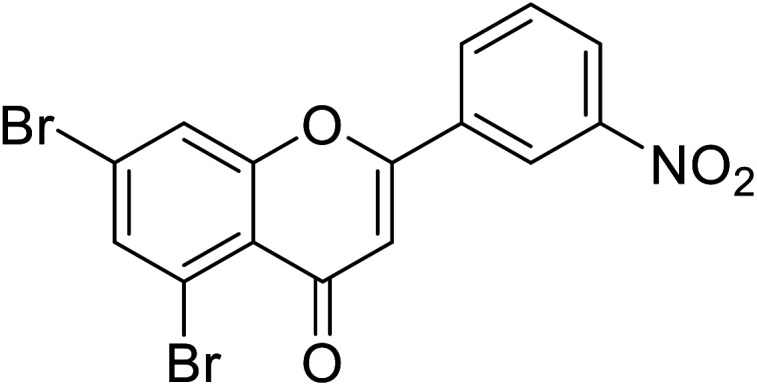

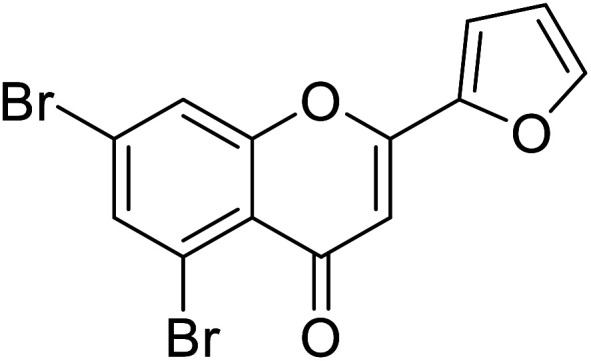

Jamshaid et al.87 reported compound 69 as a new synthetic analog of flavone with potential TIs (Table 8). It is obvious from their findings that the indole moiety present at the 2-position of the flavone motif is responsible for enhanced TI action as reflected by the greater activity obtained relative to the standard. Furthermore, the other substituted synthetic 2-phenylchromones substituted with a nitro group at the 4th position and dimethoxy groups at 3rd and 4th positions on the B ring, respectively, showed extraordinary activity as compared to the standard kojic acid.

Chemical structures of synthetic flavones and IC50 values obtained against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

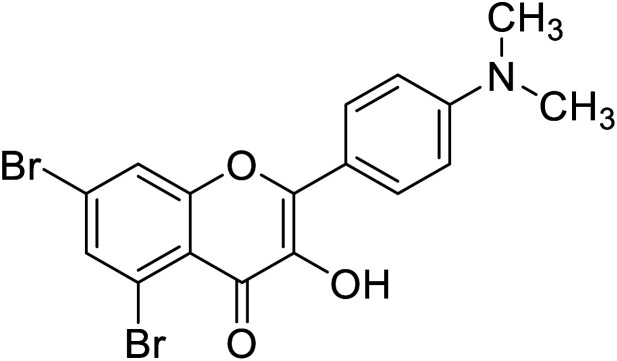

| 65 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.57 | 87 |

| 66 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.27 | 87 |

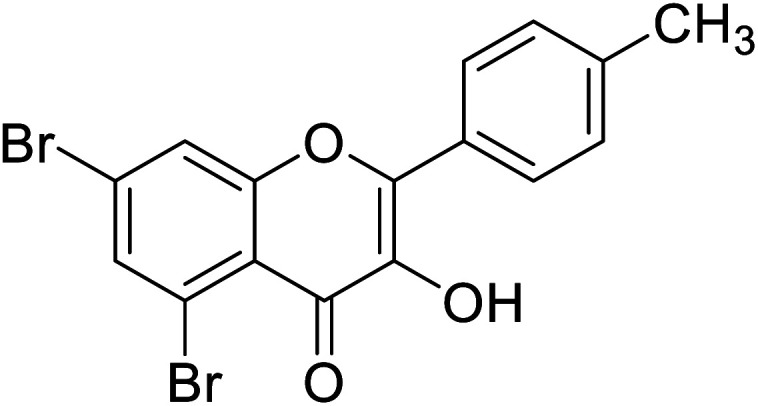

| 67 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.49 | 87 |

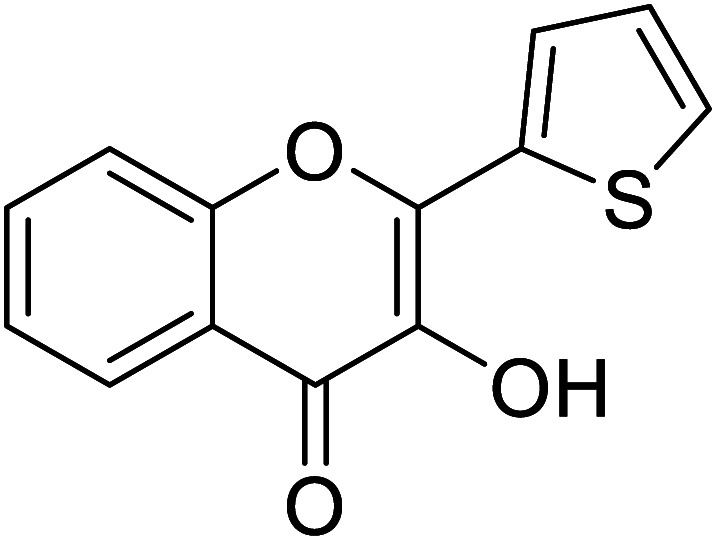

| 68 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.68 | 87 |

| 69 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(1H-indol-3-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.22 | 87 |

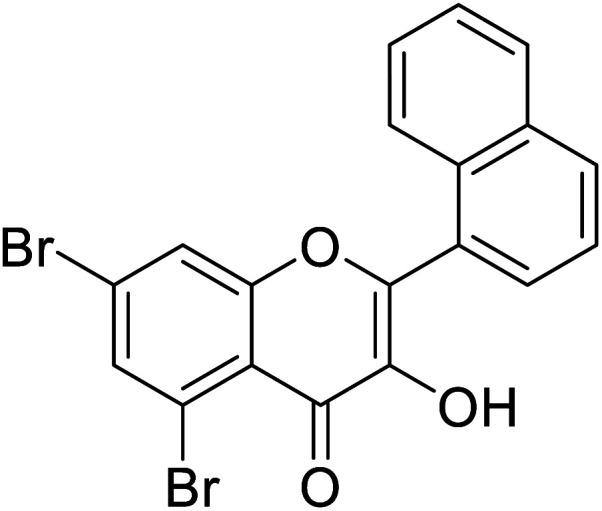

| 70 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

3.41 | 87 |

| 71 | 4-(5,7-Dibromo-4-oxo-4H-chromen-2-yl)benzoic acid |

|

3.28 | 87 |

| 72 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(3-nitrophenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

3.28 | 87 |

| 73 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(furan-2-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

2.07 | 87 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

1.79 | 87 |

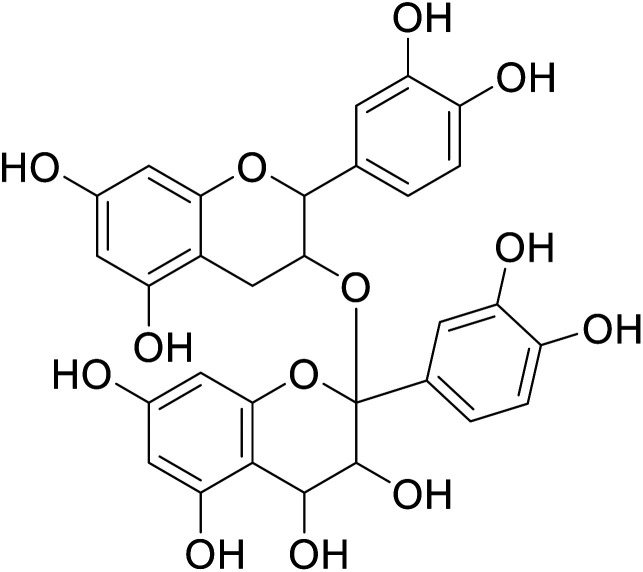

5.5. Flavanols

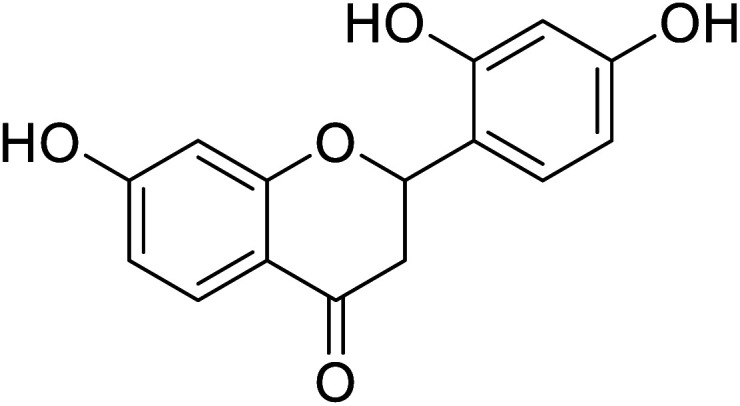

Flavanonols are a diverse subclass of the flavonoid family that includes catechin monomers and epicatechin isomers, as well as oligomeric and polymeric proanthocyanidins and condensed tannins. Flavanols found in the higher plants and medicinal herbs include epicatechin, catechin, epi-gallocatechin, ECG, EGCG, and proanthocyanidins. Astelia neocaledonica is a prevalent Caledonia tree, which was recognized as an anti-tyrosinase source due to the existence of gallocatechin and tannins. Furthermore, proanthocyanidins from Clausena lansium showed excellent TI in a competitive style and demonstrated good melanogenic inhibition activity of B16 cells (Table 9). Another study described that compound 81, purified from Annona squamosa pericarp, could strongly inhibit the monophenolase and diphenolase actions of tyrosinase, competitively.130–133 Additionally, Kim et al.134 had shown that catechin–aldehyde poly-condensates reduce the hydroxylation of l-tyrosine and oxidation of l-DOPA by chelation to the tyrosinase active site.

Chemical structures of natural flavanols and IC50 values obtained against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

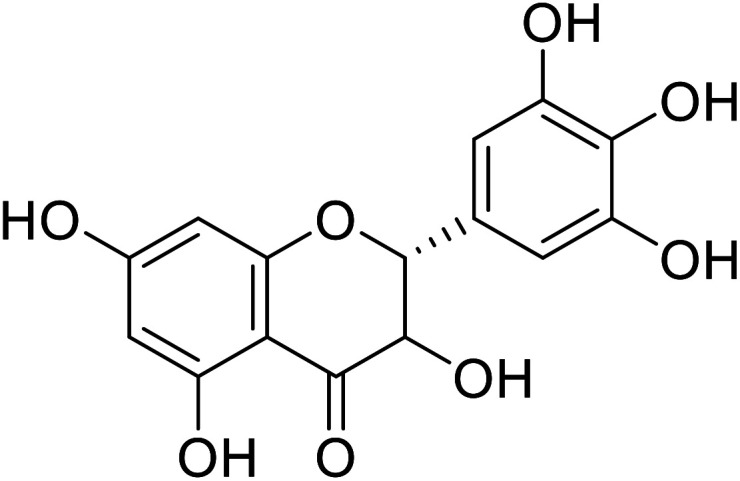

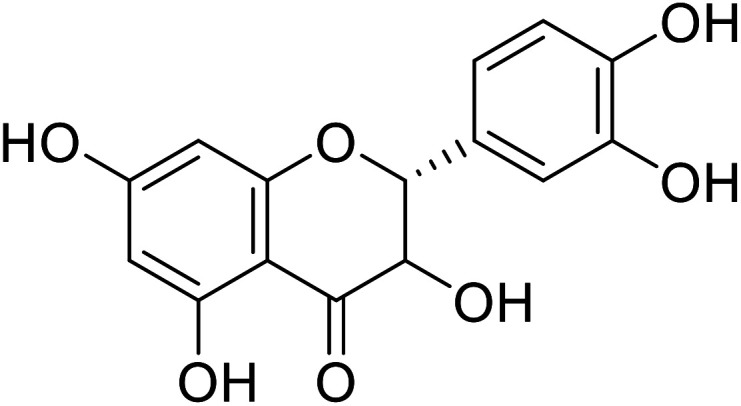

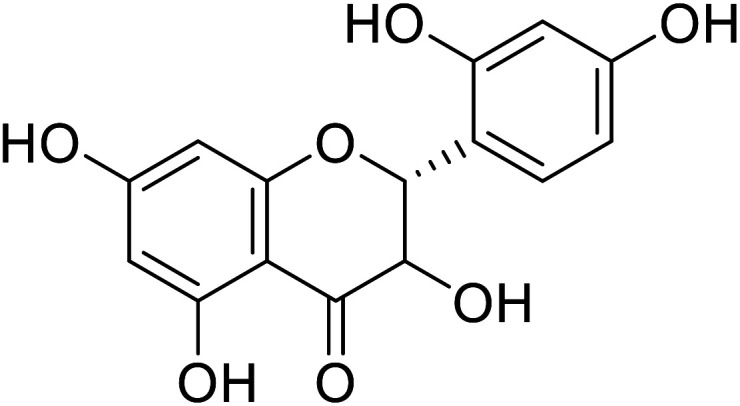

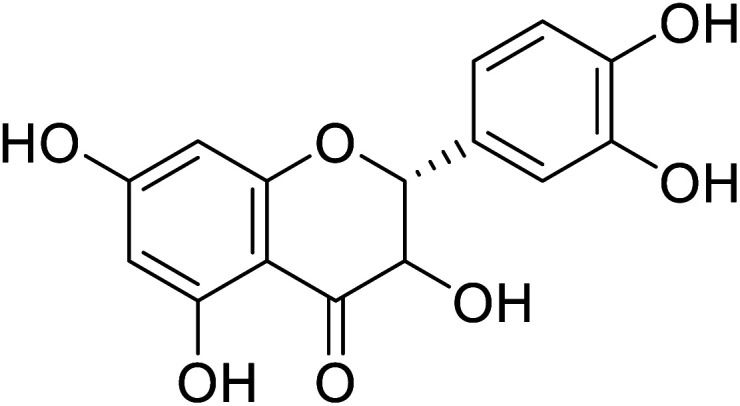

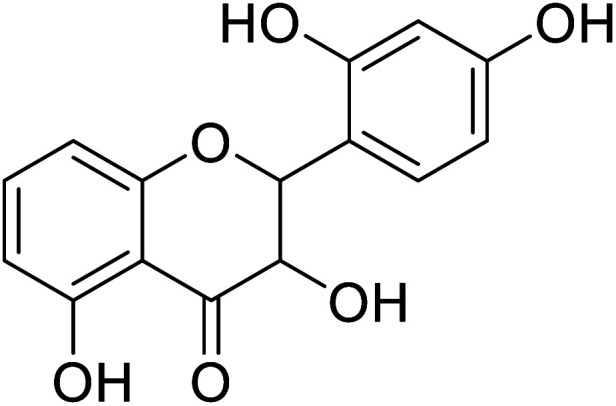

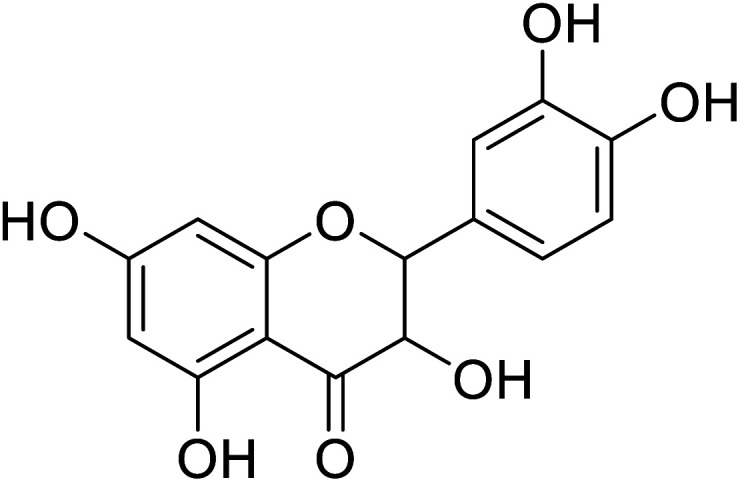

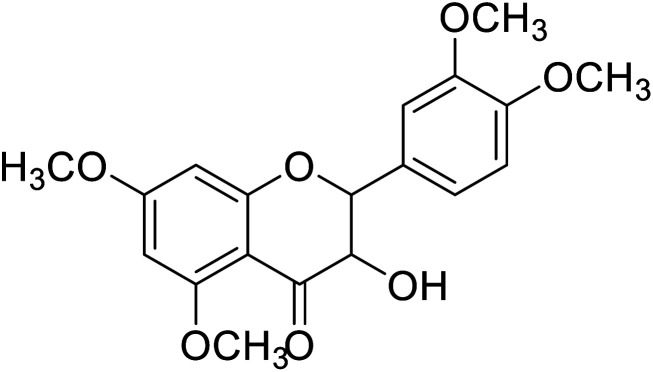

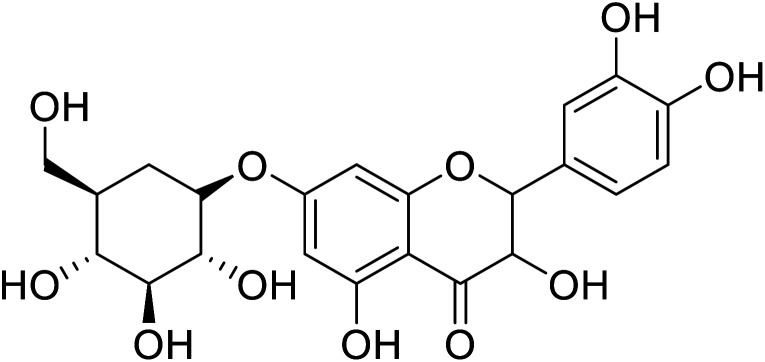

| 74 | Dihydromyricetin |

|

849.88 | 167 |

| 75 | Taxifolin |

|

0.24 | 118 |

| 76 | Dihydromorin |

|

9.4 | 10 |

| 77 | Dihydroxykampherol |

|

>200 | 58 |

| 78 | Broussoflavonol J |

|

9.29 | 96 |

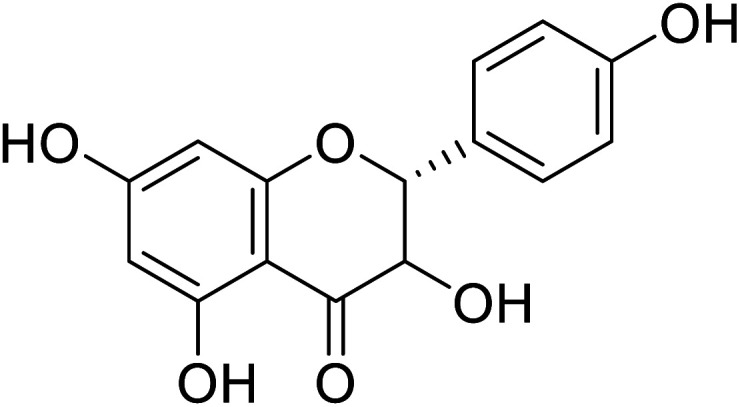

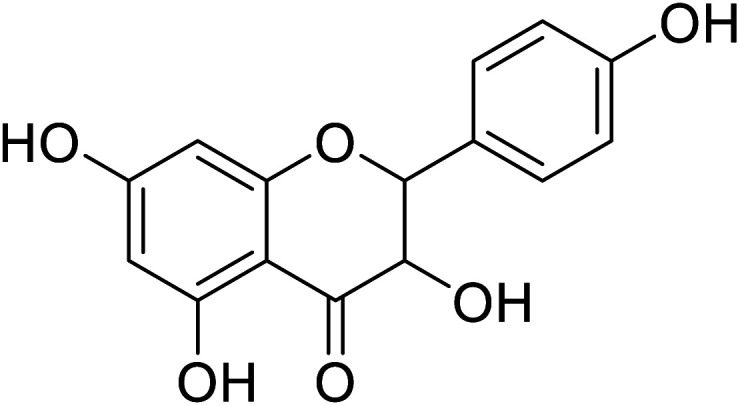

| 79 | 3,5,7-Trihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)chroman-4-one |

|

25 | 22 |

| 80 | Chlorophorin |

|

6.6 | 172 |

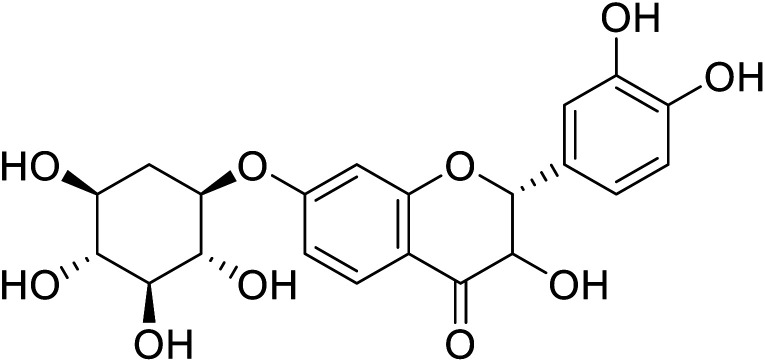

| 81 | Proanthocyanidins |

|

55.01 | 146 |

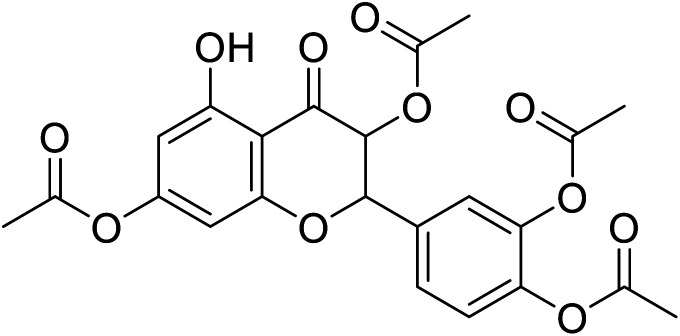

| 82 | 4-(3,8-Diacetoxy-5-hydroxy-4-oxochroman-2-yl)-1,2-phenylene diacetate |

|

>230 | 28 |

| 83 | 3,5,7-Trihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)chroman-4-one |

|

>100 | 28 |

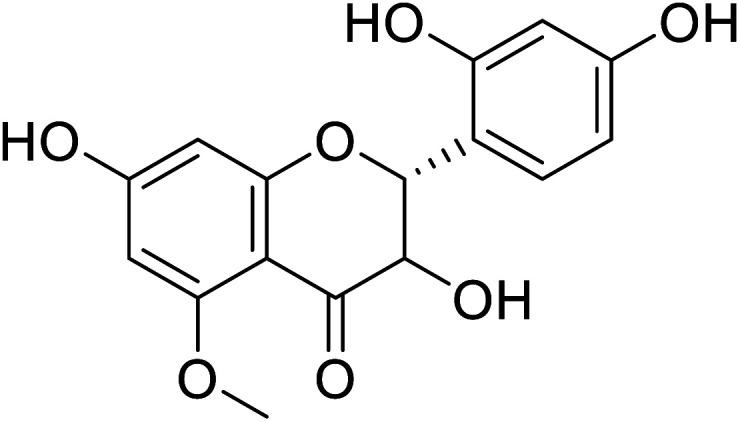

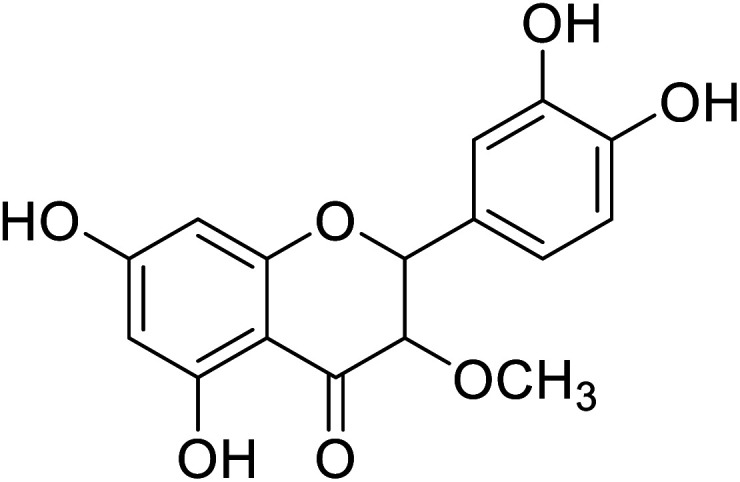

| 84 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-3-methoxychroman-4-one |

|

>300 | 28 |

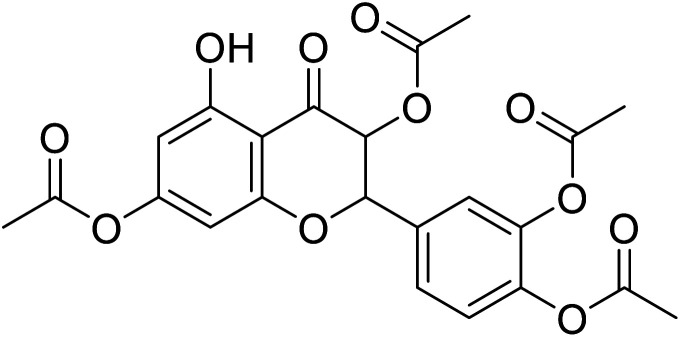

| 85 | 4-(3,7-Diacetoxy-5-hydroxy-4-oxochroman-2-yl)-1,2-phenylene diacetate |

|

>230 | 28 |

| 86 | 2-(2-Hydroxyphenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxychroman-4-one |

|

25 | 28 |

| 87 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxychroman-4-one |

|

>300 | 28 |

| 88 | 2-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-5,7-dimethoxychroman-4-one |

|

75.8 | 28 |

| 89 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dihydroxy-(7,2,3,4-trihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)cyclohexyl)oxychroman-4-one |

|

>200 | 28 |

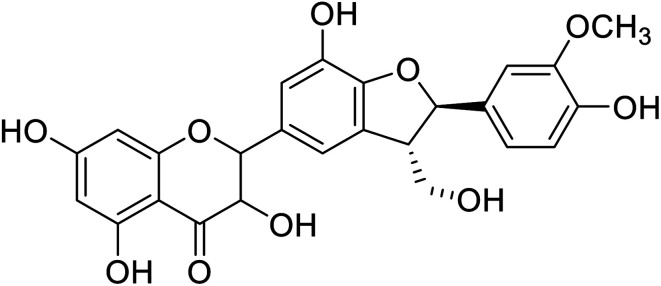

| 90 | 3,5,7-Trihydroxy-2,7-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzofuran-5-ylchroman-4-one |

|

28.8 | 28 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

237 | 28 and 167 |

Many flavanols have been extracted from plants, and several have been classified as potent TI's. The inhibitory mode of these natural inhibitors is normally competitive inhibition for the oxidation of l-dopa by tyrosinase where the 3-hydroxy-4-keto moiety (Table 9) of the flavanol structure plays the key role in copper chelation.28,135–138 Currently, to the best of our knowledge, there is no literature available on synthetic flavanols as mushroom TIs inhibitors.

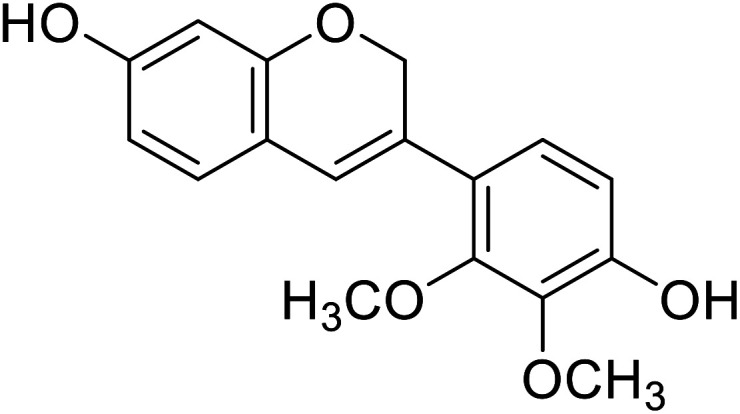

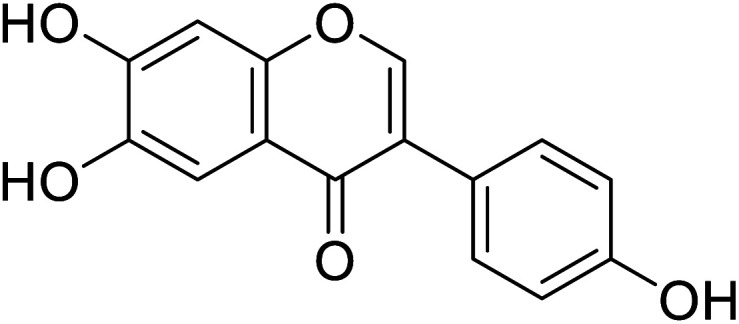

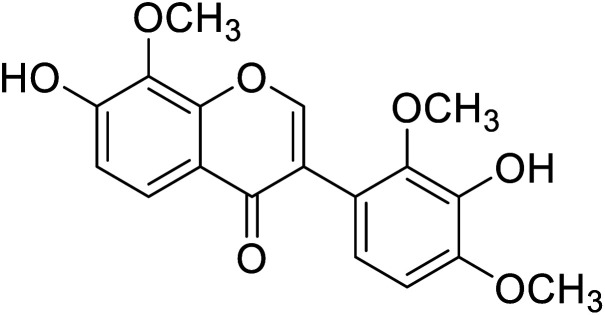

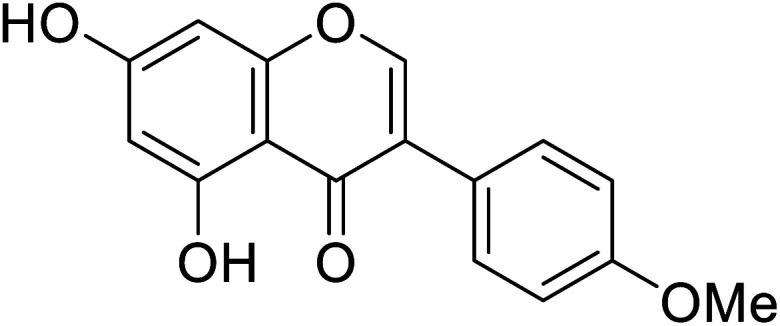

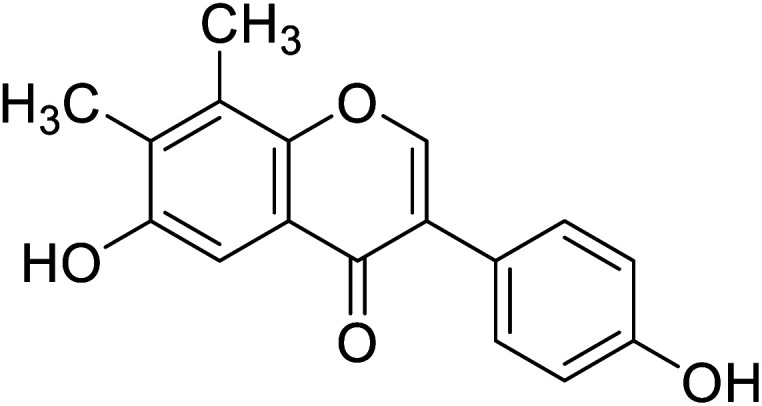

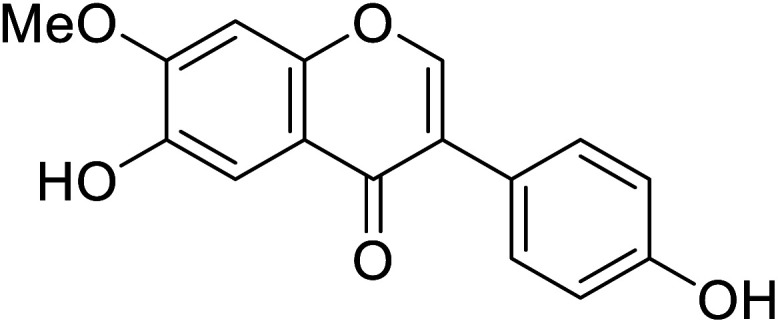

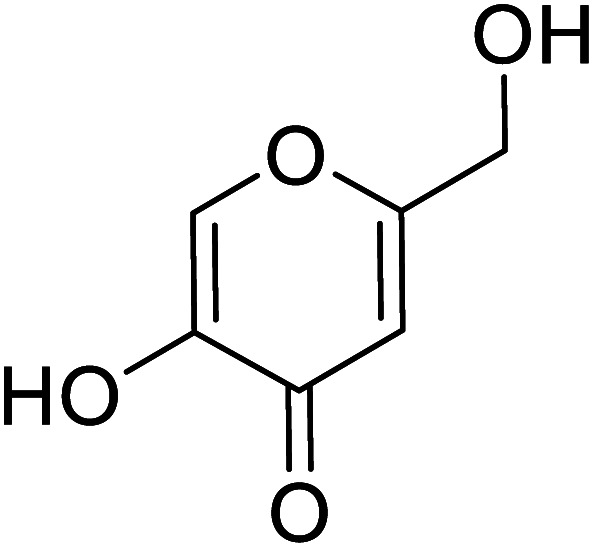

5.6. Isoflavones

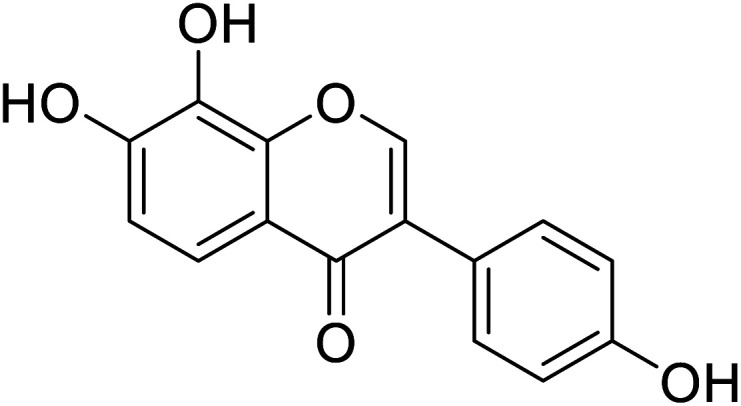

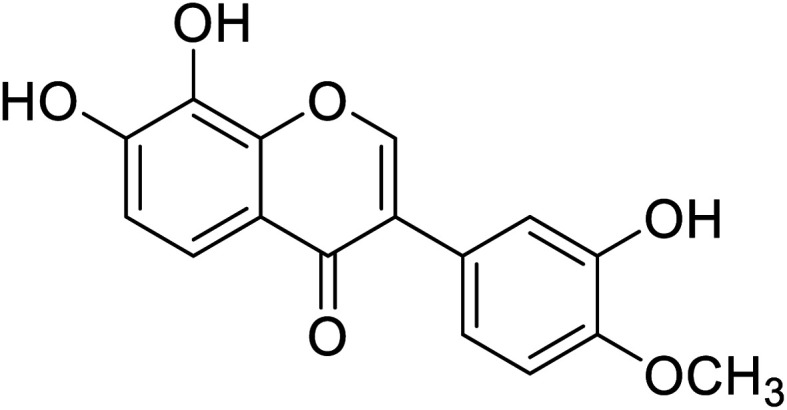

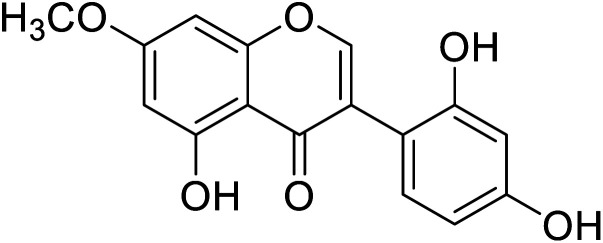

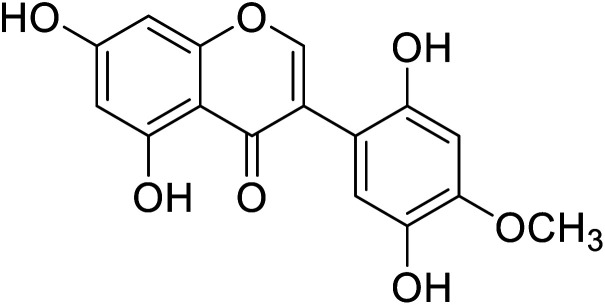

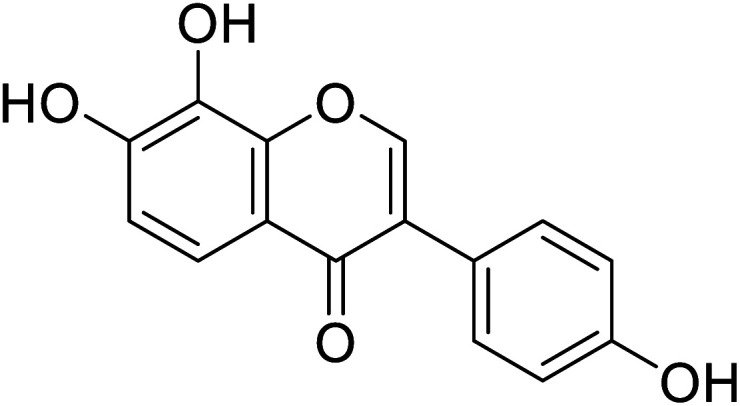

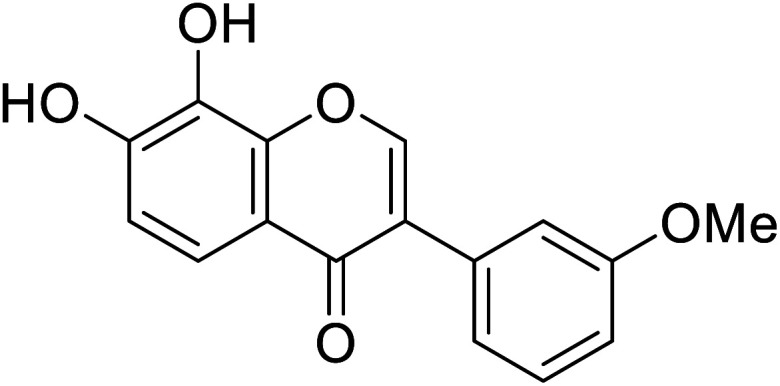

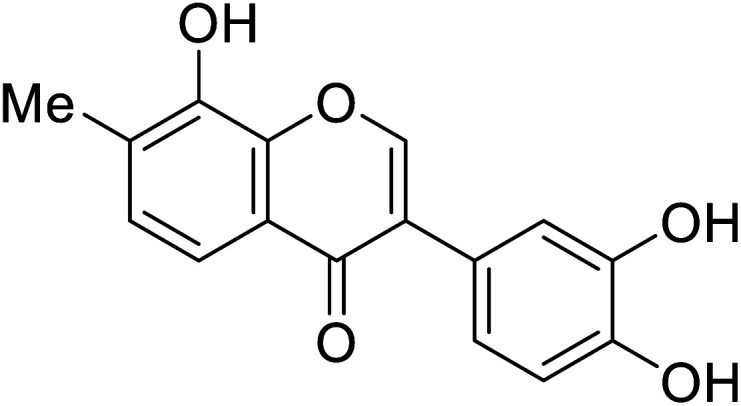

Isoflavones like daidzein and genistein, as well as their glycosides, are often found in medicinal plants. Park et al. investigated the activity of certain natural dihydroxylisoflavone analogs with a variable –OH group position at the aryl ring of isoflavone isolated from Korean fermented soybean paste in inhibiting tyrosinase. They discovered two trihydroxyisoflavone analogs with different positions of the hydroxyl groups. These produced IC50 values of 5.23 (compound 92) and 11.2 μM (compound 93) against mushroom tyrosinase. However, compound 91, a related derivative, showed no anti-tyrosinase activity (Table 10). As a result, it has been suggested that the C6 and C7 –OH groups of the isoflavone scaffold might be significant for inhibiting tyrosinase.135

Chemical structures of natural isoflavones and IC50 values obtained against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

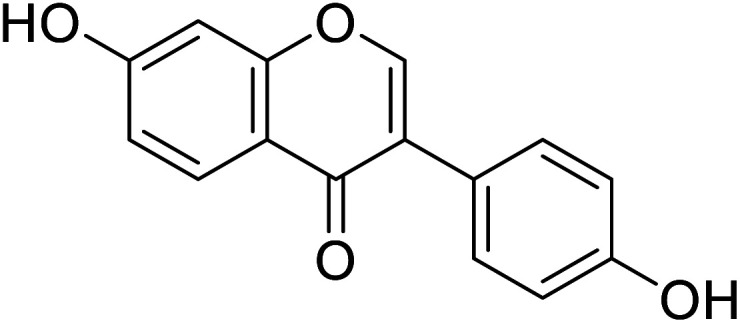

| 91 | Daidzein |

|

17.50 | 30 |

| 92 | 7,3′,4′-Trihydroxyisoflavone |

|

52.3 | 135 |

| 93 | 7,8,4′-Trihydroxyisoflavone |

|

11.21 | 135 |

| 94 | 3,8-Dihydroxy-9-methoxy pterocarpan |

|

16.7 | 141 |

| 95 | 3′-Hydroxygenistein |

|

15.9 | 168 |

| 96 | 6-Hydroxydaidzein |

|

0.009 | 58 |

| 97 | Calycosin |

|

1.45 | 180 |

| 98 | Cajanin |

|

67.9 | 58 |

| 99 | Daidzein-7-O-β-glucopyranose |

|

22.2 | 58 |

| 100 | 5-Hydroxy-daidzein-7-O-β-glucopyranose |

|

4.39 | 58 |

| 101 | 7-(b-Glucopyranosyl)-2′-hydroxygenistein |

|

729 | 58 |

| 102 | (8,9)-Furanyl-pterocarpan-3-ol |

|

7.18 | 50 |

| 103 | Neorauflavane |

|

500 | 78 |

| 104 | 3′-Hydroxy-8-methoxy vestitol |

|

67.8 | 50 |

| 105 | Khrinone B |

|

54.0 | 50 |

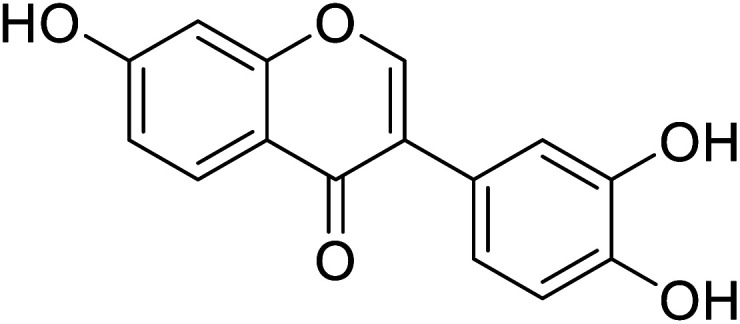

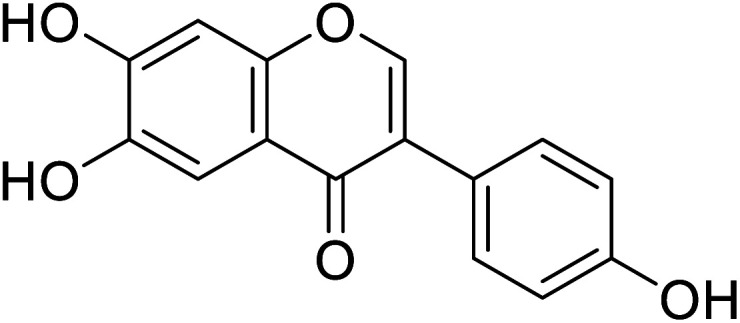

| 106 | 7,8-Dihydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

45.8 | 48 |

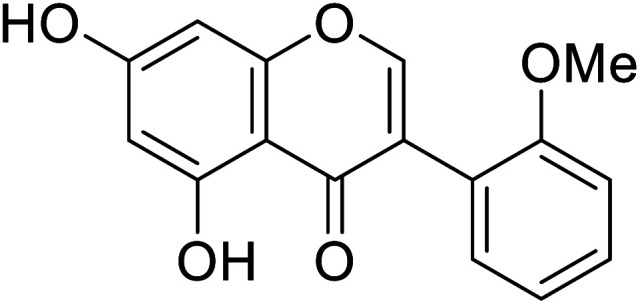

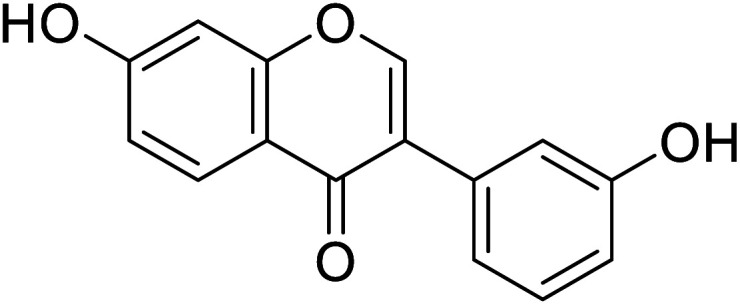

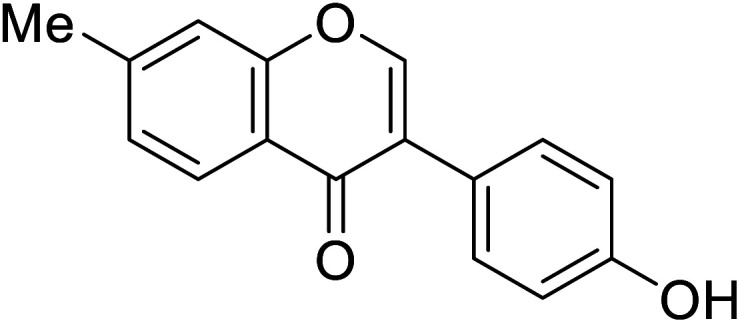

| 107 | 7,8-Dihydroxy-3-(3-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

53.9 | 48 |

| 108 | 3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-8-hydroxy-7-methyl-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

129.9 | 48 |

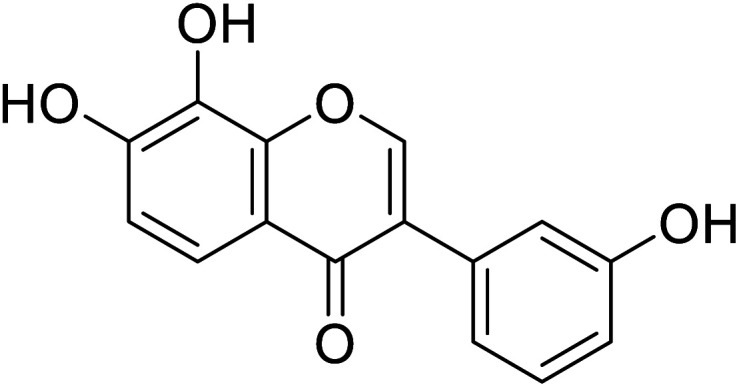

| 109 | 7,8-Dihydroxy-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

96.4 | 48 |

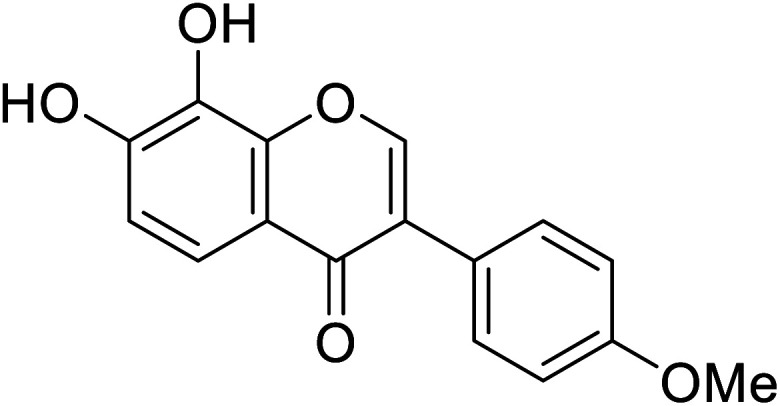

| 110 | 7,8-Dihydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

50.9 | 48 |

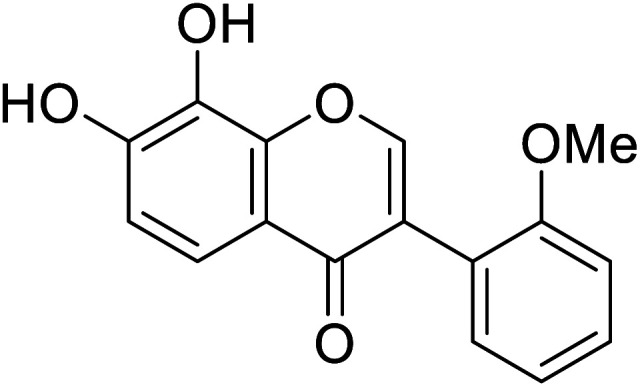

| 111 | 7,8-Dihydroxy-3-(2-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

82.8 | 48 |

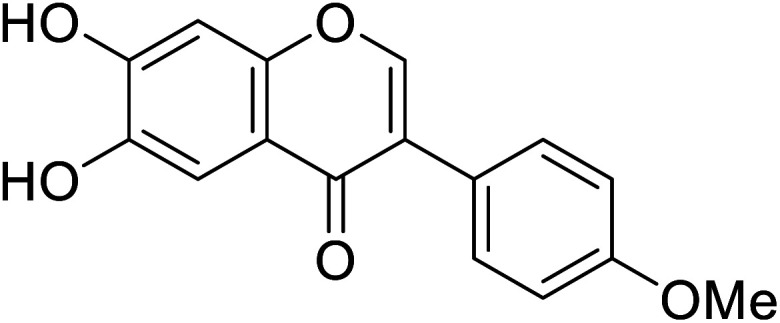

| 112 | 6,7-Dihydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

8.1 | 68 |

| 113 | 6,7-Dihydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

15.6 | 68 |

| 114 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-3-(2-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

171.1 | 68 |

| 115 | 7-Hydroxy-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

110.9 | 68 |

| 116 | 3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-7-methyl-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

38.1 | 68 |

| 117 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

141.3 | 68 |

| 118 | 6-Hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7,8-dimethyl-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

45.8 | 68 |

| 119 | 6-Hydroxy-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-7-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

83.5 | 68 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

89 | 48, 68, 135 and 141 |

Likewise, compound 93 extracted from soygerm koji, was evaluated by Chang et al. They also discovered that 7,8,4′-trihydroxyisoflavone is a potent inhibitor of tyrosinase monophenolase activity, with an IC50 value of 9.2 μM, rendering 93 six times more active than kojic acid. This compound had an irreversible inhibitory effect on both monophenolase and diphenolase activities. It may be concluded that the presence of the –OH group at both the C7 and C8 positions could entirely alter the inhibitory effect of the isoflavones from the reversible competitive to the irreversible suicide form ref. 139 and 140. Recently, the two isoflavones 6-hydroxydiadezein (compound 96) and calycosin (compound 97), isolated from Agave americana were recognized as competitive inhibitors.141 The most active mushroom TI was compound 112, which was 5 to 9 times higher than arbutin. In the various test intervals, the only oxygenated isoflavones at the C6 position displayed an excellent anti-tyrosinase activity with IC50 values of 52.3 and 45.8 μM (ref. 142) (Table 10).

In the 7-oxygenated series (Table 10), compounds 107 and 116 possessed notable anti-tyrosinase activity (IC50 = 53.9 and 38.1 μM), whereas the potent TI among the 7,8-dimethylated series was compound 118 (IC50 = 45.8 μM). Noteworthy, isoflavones having free hydroxyl groups at C6, C7, or C4′ usually exhibited potent anti-tyrosinase activities. However, the activity becomes erratic when both the C7and C4′ are hydroxylated in the same motif. For instance, while daidzein and genistein were inactive, 6,4′-dihydroxy-7,8-dimethylisoflavone and 6-hydroxydaidzein were the most potent TIs. In this study, o-dihydroxylated series with –OH groups at C7 and C8 or C6 and C7 appeared to be better mushroom TI's, except the C7-methoxylated derivatives. This result revealed that the inhibitory manner of the o-dihydroxylated series was different from that of the non-o-dihydroxylated series.46

Basically, O-bearing substituents at C4′ of ring B seem to contribute to the anti-tyrosinase activity, whereas the –OH or –MeO at C2′ and C3′ of ring B of an isoflavone tend to attenuate the TI effect. However, the existence of a lipophilic end in hydroxylated isoflavones may contribute to the binding to mushroom tyrosinase.143 The synthetic analogs of isoflavones as TIs have not yet been reported in the literature.

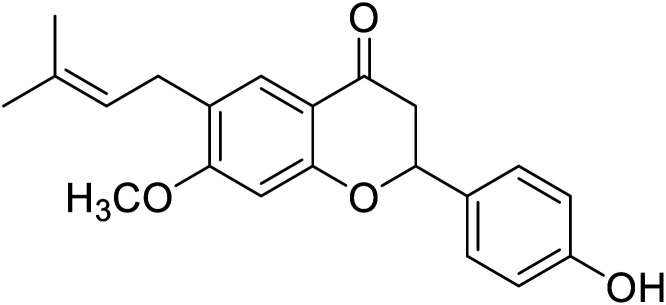

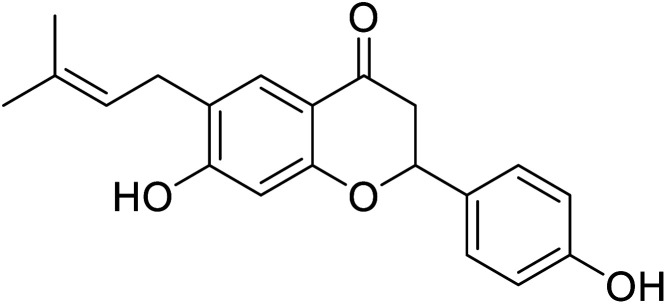

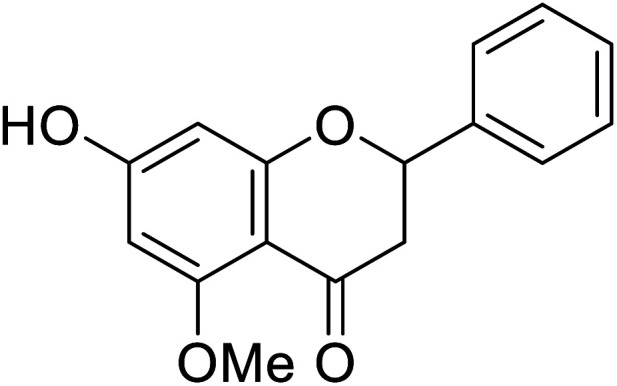

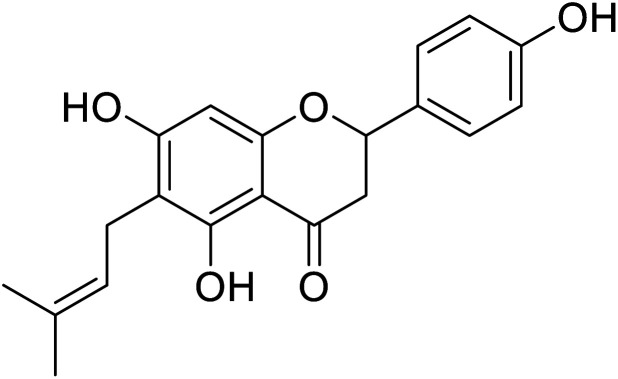

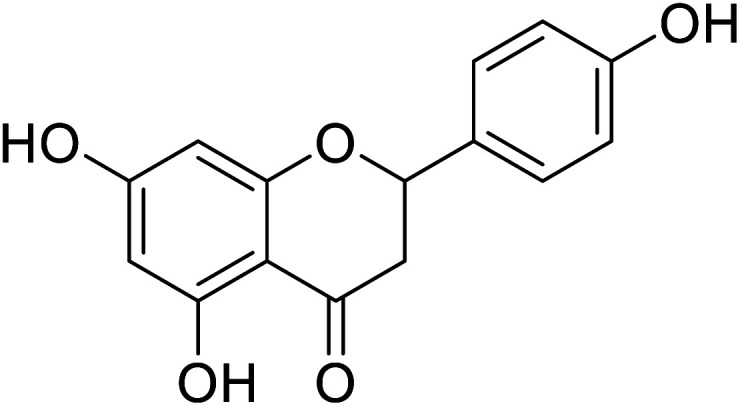

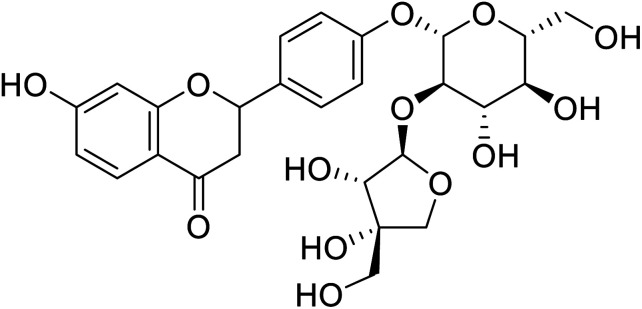

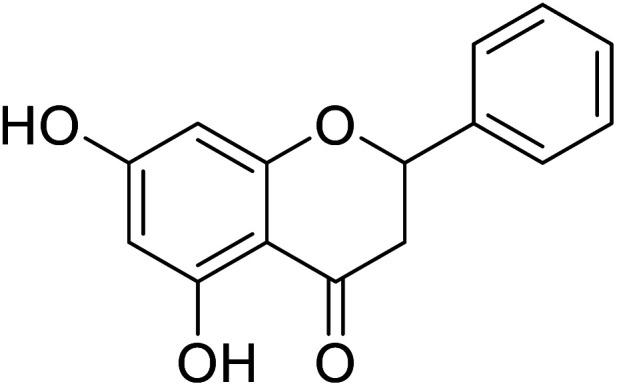

5.7. Flavanones

Flavanones may be discerned from other flavonoids by the absence of the covalent double bond ‘ ’ connecting the 2nd and 3rd positions of the pyrone ring. A systematic study about the influence of the number and position of –OH groups on the aryl ring indicated the importance of p-position on ring B.144 Naturally occurring flavanones such as streppogenin, bavachinin, alpinetin are primarily found in medicinal herbs and citrus fruits. Streppogenin, a copper chelator flavanone, inhibits tyrosinase reversibly and competitively (Table 11).

Chemical structures of natural flavanones and IC50 values obtained against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

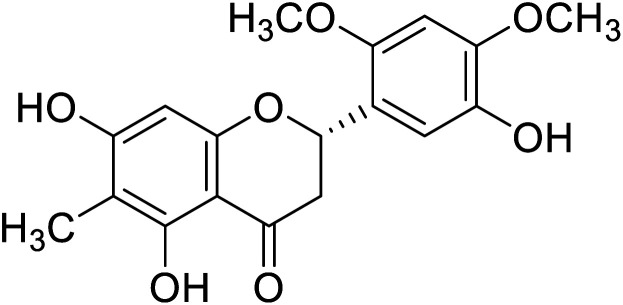

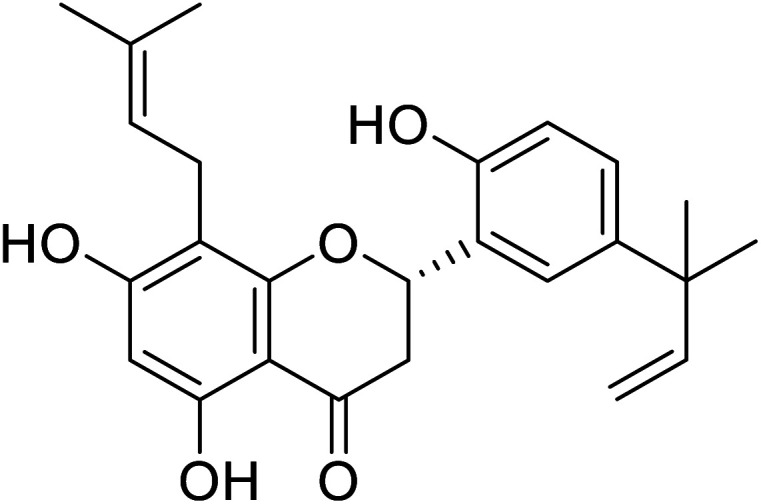

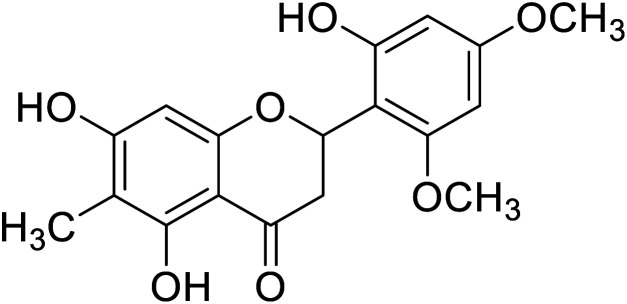

| 120 | 5,5′,7-Trihydroxy-2′,4′-dimethoxy-6-methylflavanone |

|

44.74 | 68 |

| 121 | Streppogenin |

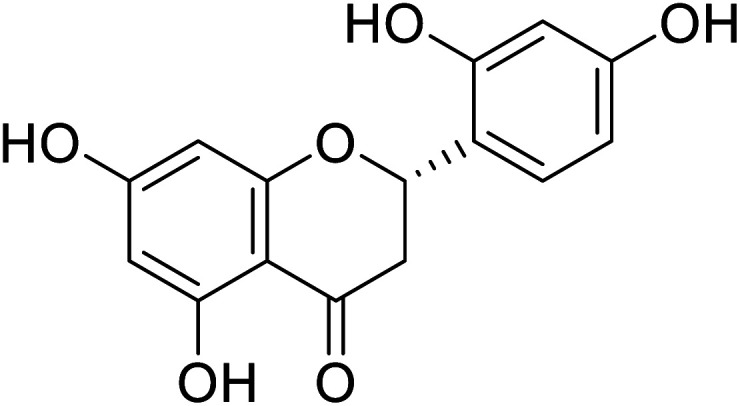

|

1.3 | 68 |

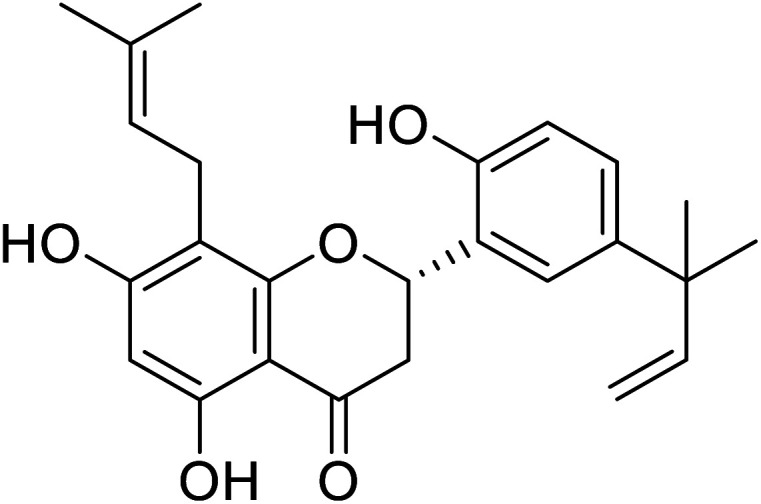

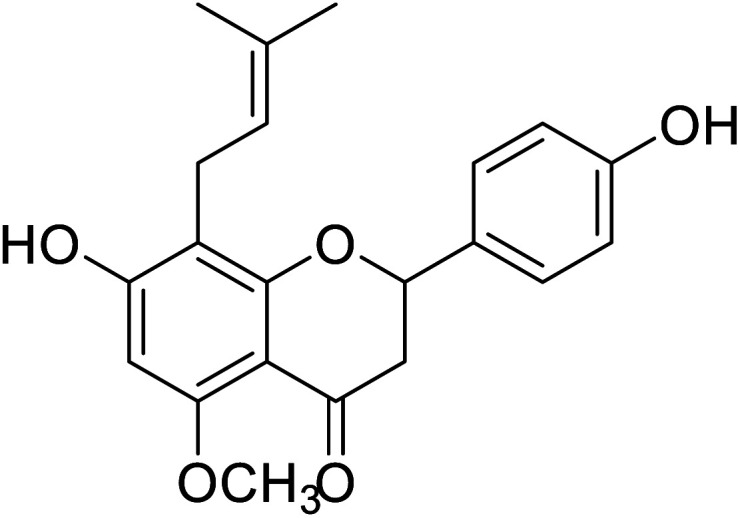

| 122 | 5,7,2′-Trihydroxy-5′-(1′′′,1′′′-dimethylallyl)-8-prenylflavanone |

|

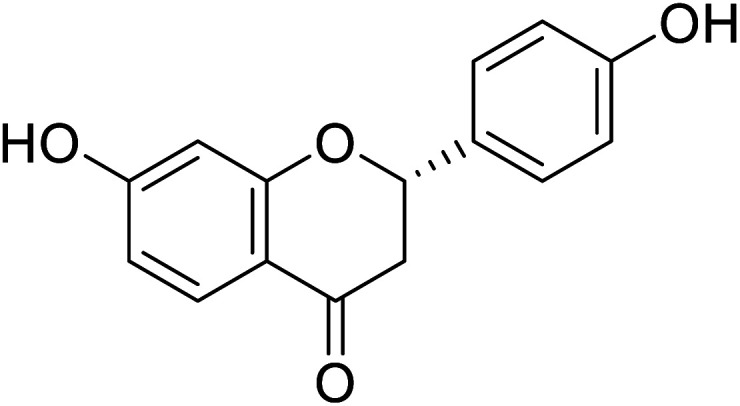

27.5 | 97 |

| 123 | Liquiritigenin |

|

22.0 | 50 |

| 124 | Bavachinin |

|

143.9 | 30 |

| 125 | Corylifolin |

|

23.6 | 30 |

| 126 | Alpinetin |

|

450 | 50 |

| 127 | Delanin |

|

0.26 | 144 |

| 128 | 5,7,2′-Trihydroxy-8,3′-diprenylflavanone |

|

68.5 | 97 |

| 129 | 5,7,2′-Trihydroxy-5'-(1′′′,1′′′-dimethylallyl)-8-prenylflavanone |

|

27.5 | 142 |

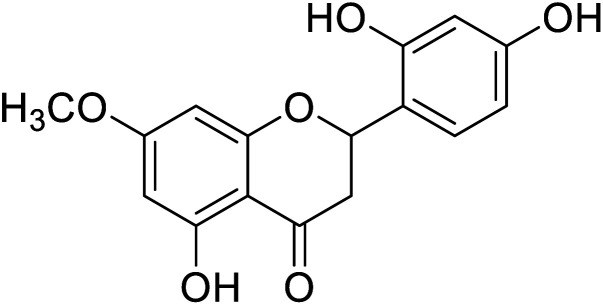

| 130 | 2-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-7-hydroxychroman-4-one |

|

0.11 | 4 |

| 131 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-6-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)chroman-4-one |

|

38.1 | 4 |

| 132 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(2-hydroxy-4,6-dimethoxy phenyl)-6-methylchroman-4-one |

|

44.74 | 4 |

| 133 | 7-Hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-methoxy-8-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)chroman-4-one |

|

77.4 | 4 |

| 134 | 2-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-5-hydroxy-7-methoxychroman-4-one |

|

2.0 | 4 |

| 135 | 2-(2,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxychroman-4-one |

|

1.76 | 4 |

| 136 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy phenyl)chroman-4-one |

|

>300 | 4 |

| 137 | (3,4-Dihydroxy-4-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)oxy-(4,5-dihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxyphenyl-7-hydroxychroman-4-one |

|

88.91 | 4 |

| 138 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-phenyl chroman-4-one |

|

>500 | 4 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

310 | 4, 30 and 50 |

Furthermore, docking findings demonstrated that hesperetin chelates a Cu2+ ion coordinating with three histidine (His61, His85, and His259) residues within the enzyme's active site. Chiari et al.144 validated the TI activity of a substituted 6-isoprenoid flavanone isolated from Dacryopinax elegans in another report. Among these inhibitors, streppogenin was a stronger inhibitor than the positive controls, arbutin or kojic acid.

Several phenolic compounds isolated from various plants were tested as inhibitors of mushroom tyrosinase. The Moraceae family is an effective supplier of skin-whitening agents4,145–152 (Table 11), and a source of several flavanone analogs that display, in some cases, very low IC50 values. Like compounds in the previous class, these analogs have not been explored as synthetic inhibitors against tyrosinase.

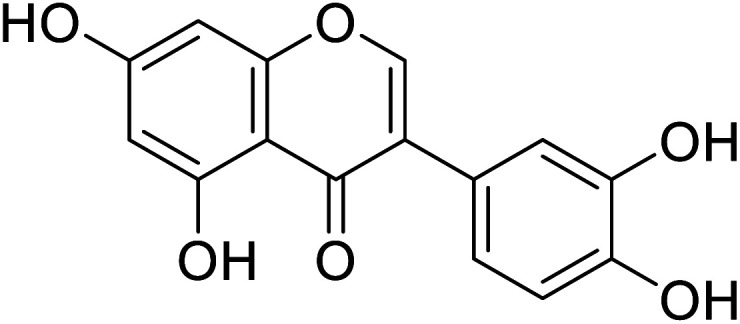

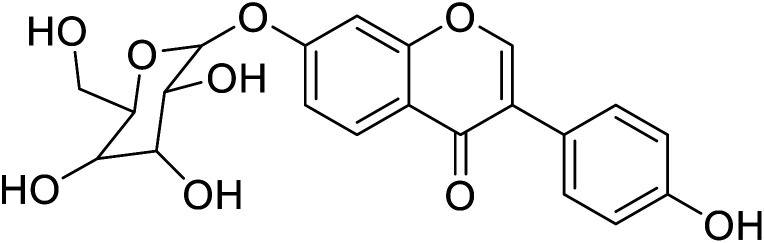

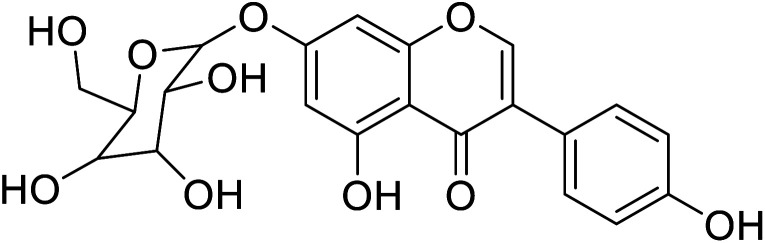

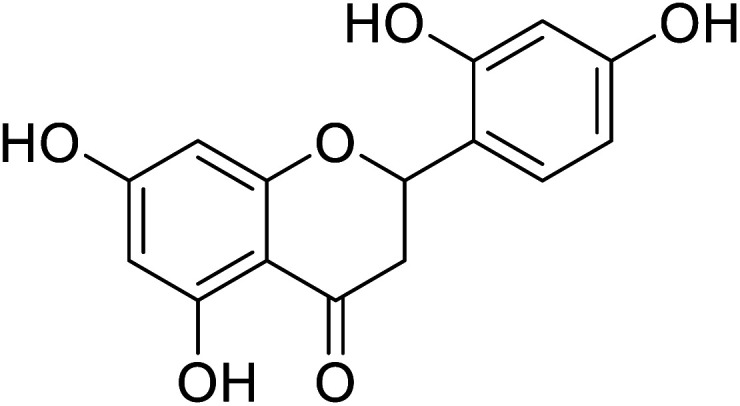

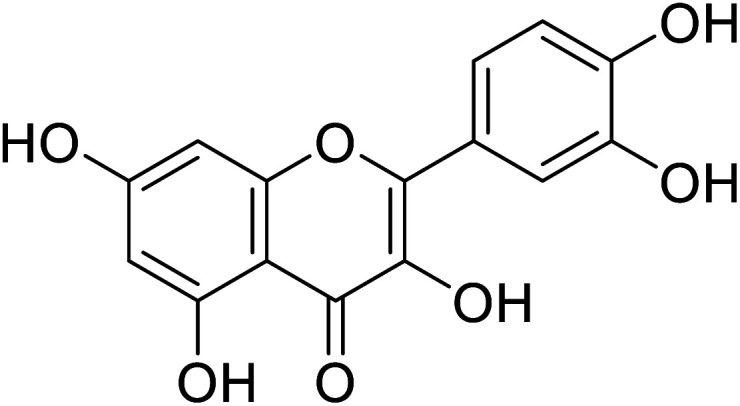

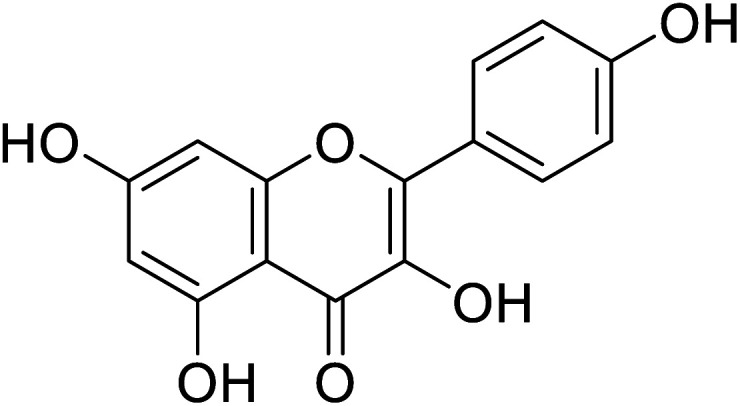

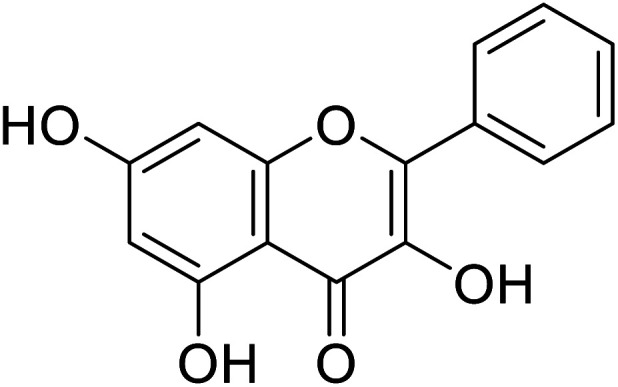

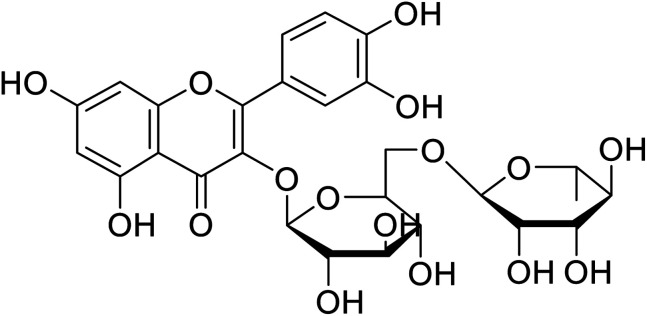

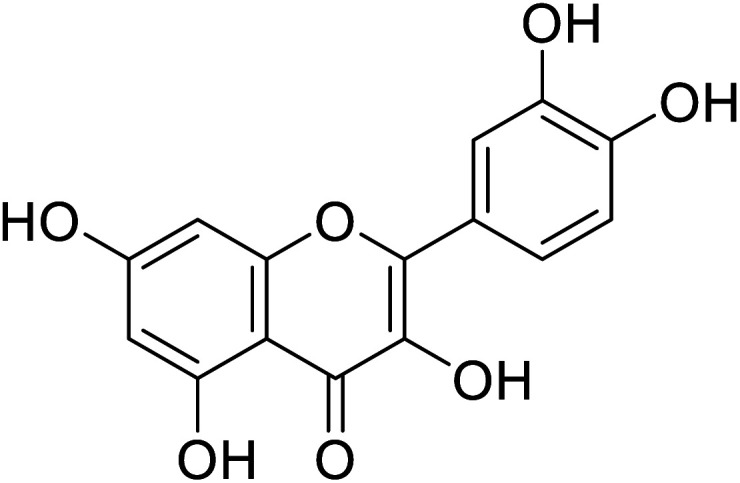

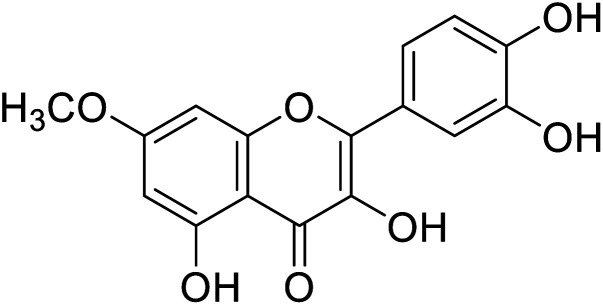

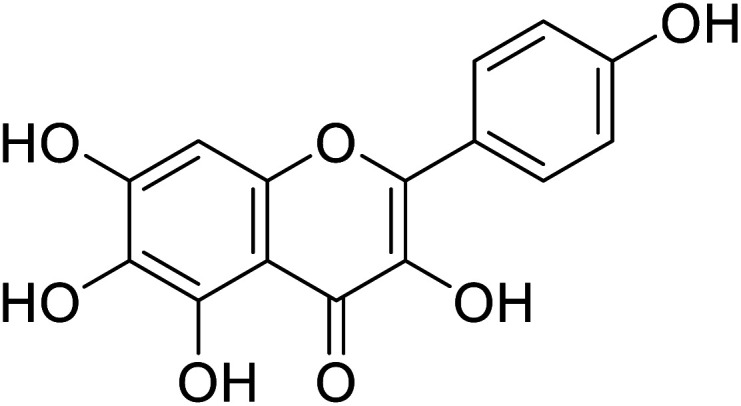

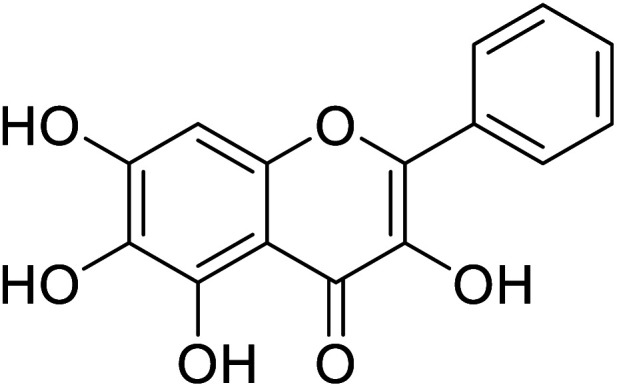

5.8. Flavonols

Plants contain numerous flavonols, some of which have been described as tyrosinase inhibitors. The flavonol's structure, 3-hydroxy-4-keto moiety, is essential in copper chelation, and the inhibitory mode of flavonol inhibitors is normally competitive inhibition for the oxidation of l-dopa by tyrosinase.153 Kaempferol, myricetin, quercetin, isorhamnetin, galangin, morin, and their glycosides are the prevalent naturally occurring flavonols, mostly found as O-glycosides.154–160 So far, several flavonols such as quercetin from Olea europaea, kaempferol from Hypericum laricifolium, and Crocus sativus, quercetin-4′-O-beta-D-glucoside from Parornix bifurca, quercetin glucopyranoside and kaempferol glucopyranoside from mulberry leaves, morin and 2,3-cis-dihydromorin, 2,3-trans-dihydromorin from Chloropsis cochinchinensis, were found to act as tyrosinase inhibitors (Table 12). Moreover, it was reported that three 3-hydroxyflavones including kaempferol, galangin, and quercetin inhibit the l-DOPA oxidation process catalyzed by tyrosinase, and apparently, this TI activity arises from their Cu2+ chelating ability.161–166 Kubo et al. assumed that the chelation mechanism by flavonols may be attributed to the free 3-OH group. Remarkably, quercetin acts as a cofactor and does not inhibit monophenolase activity. The common feature of these three flavonols167–172 is that they all inhibit diphenolase activity by chelating copper in the enzyme. Furthermore, quercetin glucoside, with an IC50 value of 1.9 μM, inhibited tyrosinase more effectively than the positive standard, kojic acid.173–178

Chemical structures of natural flavonols and IC50 values obtained against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 139 | Quercitin |

|

10.73 | 58 |

| 140 | Kaempferol |

|

5.5 | 71 |

| 141 | Galangin |

|

3.55 | 38 |

| 142 | Rutin |

|

130 | 101 |

| 143 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

53.4 | 31 |

| 144 | 2-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3,5-dihydroxy-7-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one1 |

|

72.5 | 31 |

| 145 | 6-Hydroxykaempferol |

|

124 | 31 |

| 146 | 6-Hydroxygalangin |

|

182 | 31 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

318 | 31, 38, 58 and 71 |

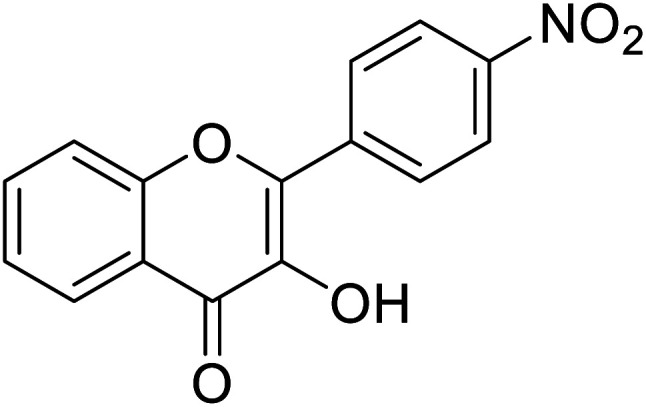

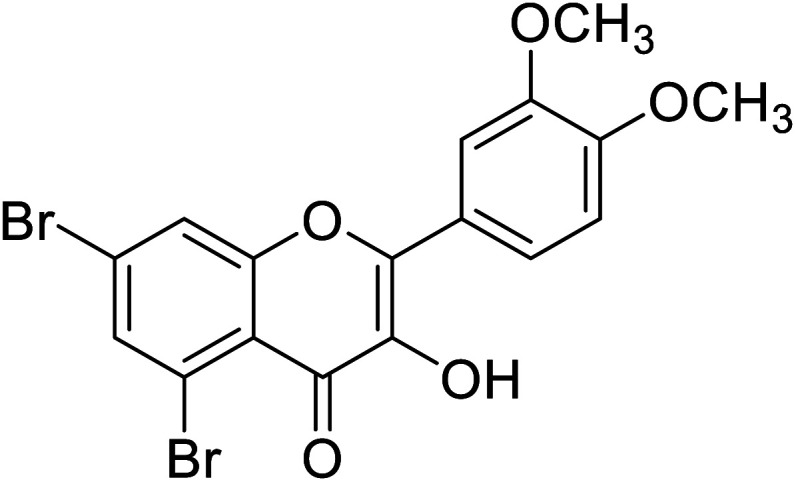

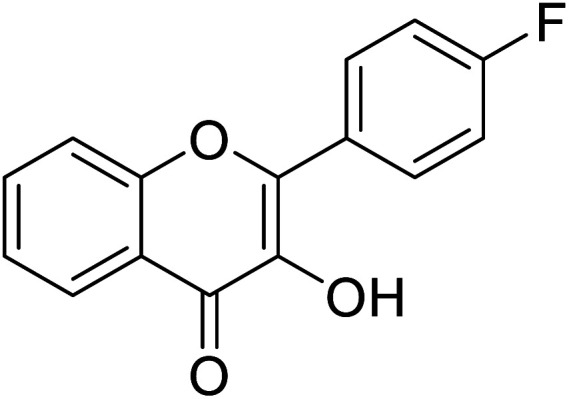

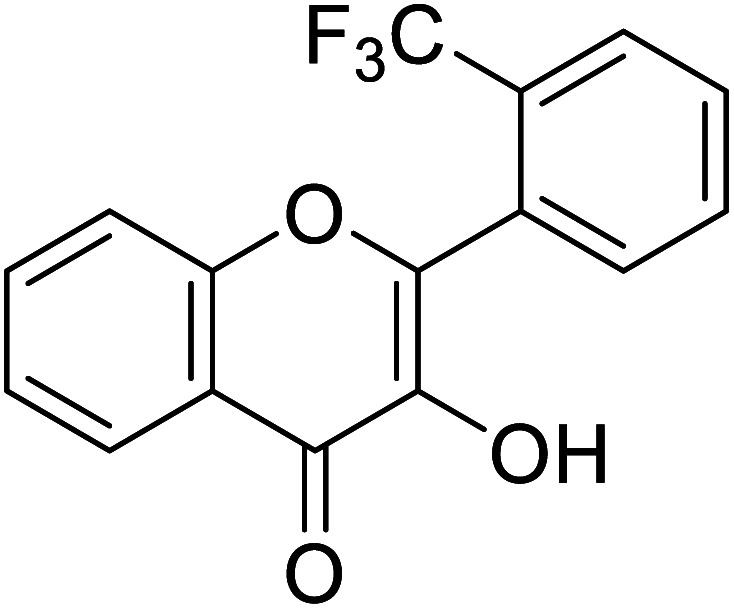

Jamshaid et al.,85 synthesized some 3-hydroxyflavone derivatives and tested their TI potential against mushroom tyrosinase (Table 13). Fascinatingly, the test analogs 2-(3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-hydroxyflavone (IC50 = 0.280 μM) and 2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-hydroxyflavone (IC50 = 0.230 μM) were found to be the most potent among all the synthesized derivatives and superior to the positive control kojic acid. The 2-(3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-hydroxyflavone possesses a highly electron-withdrawing group (–CF3) at the m-position on ring B. This reveals that the structure fits nicely and strongly interacts with the active site of the envisioned enzyme. Interestingly, 2-(2-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-hydroxyflavone (IC50 = 0.30 μM), having trifluoromethyl group (–CF3) at the o-position of ring B, was found comparatively less active than its m-isomer, but still more active than the standard.

Chemical structures of synthetic flavonols and IC50 values obtained against mushroom tyrosinase.

| Compound no. | Compound name | Chemical structures | IC50 values (μM) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

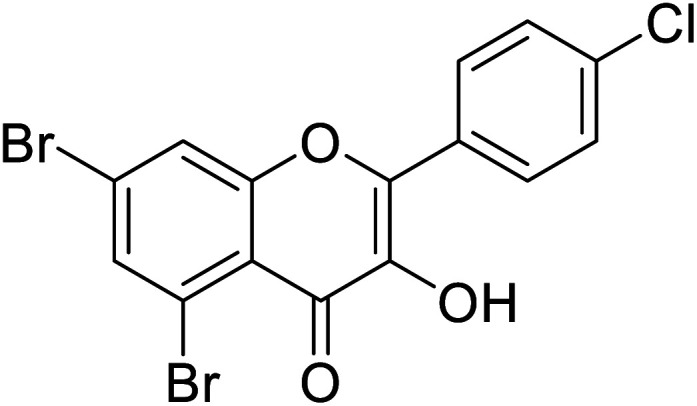

| 147 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.71 | 87 |

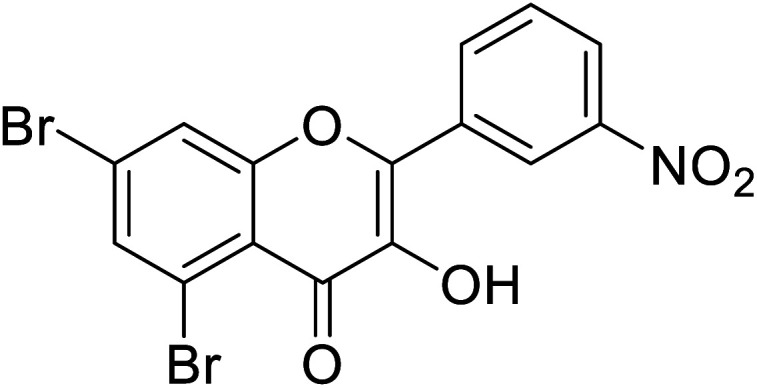

| 148 | 5,7-Dibromo-3-hydroxy-2-(3-nitrophenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.15 | 87 |

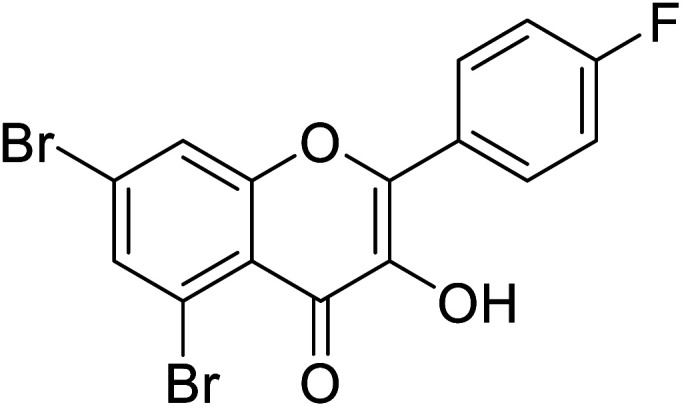

| 149 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(4-fluorophenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

2.36 | 87 |

| 150 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.50 | 87 |

| 151 | 5,7-Dibromo-3-hydroxy-2-(naphthalen-1-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.564 | 87 |

| 152 | 5,7-Dibromo-3-hydroxy-2-(p-tolyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.126 | 87 |

| 153 | 3-Hydroxy-2-(thiophen-2-yl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.347 | 85 |

| 154 | 3-Hydroxy-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.284 | 85 |

| 155 | 5,7-Dibromo-2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.093 | 87 |

| 156 | 2-(4-Fluorophenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.799 | 85 |

| 157 | 3-Hydroxy-2-(2-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.30 | 85 |

| 158 | 2-(4-Chlorophenyl)-3-hydroxy-4H-chromen-4-one |

|

0.230 | 85 |

| Standard | Kojic acid |

|

1.79 | 85 and 87 |

Jamshaid et al.,87 synthesized substituted flavonols where the most active derivative, which contains a strong EWG (–NO2) at the p-position of the B ring, was 2-(4-nitrophenyl)-3-hydroxyflavone (IC50 = 0.284 μM). Likewise, the replacement of the aromatic B ring with other 5-membered heterocyclic rings such as thiophene (IC50 = 0.347 μM) also produced excellent activity. The TI by 2-(thiophen-3-yl)-3-hydroxyflavone depends on the ability of a ‘S’ atom to coordinate with the dinuclear Cu2+ in the enzyme's active site. The high inhibitory potential may be due to the electronegativity of the two –OCH3 groups at o- and p-positions of the B-ring which fits appropriately in the active pocket of the target enzyme. Moreover, the 5,7-dibromo-2-(4-chlorophenyl)-3-hydroxyflavone has an EWD (–Cl) at 4th position on ring B. Perhaps, this functionality and its location have suitable interactions with the enzyme's active site. Subsequently, the next most active derivative, which contains a strong EWG (–NO2) at the 3rd position on the B ring, is 5,7-dibromo-2-(3-nitrophenyl)-3-hydroxyflavone. Excitingly, the p-NO2 substituted 5,7-dibromo-3-hydroxyflavone displayed enhanced activity as compared to its m-analog (Table 13).

6. Conclusions and perspectives

Pigment disorders are triggered by the upregulation or downregulation of tyrosinase. Because of the cosmetically significant issue of abnormal pigmentation and its impact on the quality of life and the development of life-threatening diseases, there is a great demand for melanogenesis inhibitors. The regulation of melanogenesis is a complicated process which involves several cellular factors. Tyrosinase, the central culprit in the enzymatic pathway of melanogenesis, has emerged as the most important target for the treatment of clinical and aesthetic hyperpigmentation. The enzyme catalyzes the first and only rate-limiting step in melanogenesis. Plants have always played a significant role as supply for drug lead compounds. In particular, some plants are rich in polyphenols, which form building blocks for the biosynthesis of chalcone, flavones, and flavonols, among others, which further form proanthocyanins and function as antioxidants. However, as these phytoconstituent have poor solubility and stability when formulated in different matrices, their bioavailability becomes a major concern. Pleasingly, their synthetic structural analogs offer interesting anti-tyrosinase activities, and thus help in the development of customized chemical agents with desired features to maximize inhibitory activity, stability, and safety for long-term use in skincare. Consequently, in recent years, many inhibitors have been identified and shown to act against tyrosinase.

It is fascinating to note that, regardless of the variety of natural inhibitors, many TI's are phenolic in nature. Several investigators had considered suitable skeletons based on natural compound structures and created new synthetic inhibitors. Among all the natural and synthetic flavonoid derivatives, the preceding survey of tabulated compounds and their inhibitory results suggest that the flavonol moiety can serve as an effective scaffold and a lead structural feature and foundation for the further development of novel tyrosinase inhibitors. For flavonols (3-hydroxyflavones), vicinal positions of the hydroxyl group and keto functionality play a significant role in chelating with Cu2+ ions to render them the most potent anti-tyrosinase agents.

Useful provisions have been proposed by molecular modeling studies that outline the essential structural elements required for the manifestation of inhibitory actions of natural compounds, providing a guide for the design of more efficient synthetic bioinspired chemical repressors. Hence, it is important to assess the efficiency and safety of inhibitors by examining e.g., whether the candidate inhibitor is a tyrosinase substrate being altered on exposure to the enzyme. Future research guidelines on pigmentation regulation by tyrosinase modulation also include the production of highly specific assays of enzymatic activity, as well as the proper use of novel formulations to enhance the efficiency of the inhibitors by increasing their bioavailability. In conclusion, we expect that this review will serve as helpful reference to the medicinal chemists working on melanogenesis, specifically on various tyrosinase enzymes, to develop lead tyrosinase inhibitors with drug-like characteristics.

Abbreviations

- DOPA

Dihydroxyphenylalanine;

- TI's

Tyrosinase Inhibitors

- PTU

1-Phenyl-2-thiourea

- UV

Ultraviolet

- kDa

Kilo dalton

- Em

Met-tyrosinase

- Eox

Oxy-tyrosinase

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- IR

Infrared

- HOPNO

2-Hydroxypyridine N-oxide

- TMBC

2,4,2′,4′-Tetrahydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl) chalcone

- His

Histamine

- Val

Valine

- Phe

Phenylalanine

- Met

Methionine

- Ser

Serine

- Ala

Alanine

- ECG

Epicatechin gallate

- EGCG

Epigallocatechin gallate

- EWG

Electron-withdrawing group

Conflicts of interest

Hereby, I declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm Al-Qura University for supporting this work under grant number 18-SCI-1-02-0006. The authors are also grateful to the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC) for providing financial assistance under the Project No. (NRPU-6484).

Biographies

Biography

Ehsan Ullah Mughal.

Ehsan Ullah Mughal was born in Wazirabad, Pakistan in 1978 and obtained his master's degree from Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan in organic chemistry. In 2013, he obtained his PhD from Bielefeld University, Germany under the supervision of Prof. Dr Dietmar Kuck. Thereafter, he moved to the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research, Mainz, Germany for a postdoctoral stay in the group of Prof. Dr Xinliang Feng. In 2015, he started his independent research group at the Department of Chemistry in University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan. His current research interests focus on the design and synthesis of bioactive heterocycles, synthetic flavonoids, transition metals-based terpyridine complexes and their fabrication in dye-sensitized solar cells and carbon-rich polycyclic aromatic compounds for applications in organic electronics.

Biography

Saleh A. Ahmed.

Saleh Abdel-Mgeed Ahmed was born in Assiut, Egypt in 1968 and received his bachelor's and master's degrees from Assiut University, Egypt, and PhD in photochemistry (photochromism) under the supervision of Prof. Heinz Dürr in Saarland University, Saarbrücken, Germany as DAAD fellow. During his last 27 years of stay in Europe, Japan, and the USA, he had successfully published more than 190 publications and has more than 15 registered and filed patents in the US patent office. His current research interests include synthesis and photophysical properties of novel organic compounds such as material-based gels, electronic devices, solar energy conversion, and bioactive materials.

References

- Chen C.-Y. Lin L.-C. Yang W.-F. Bordon J. D Wang H.-M. Curr. Org. Chem. 2015;19:4–18. doi: 10.2174/1385272819666141107224806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.-X. Lin J.-F. Song K.-K. J. Xiamen Univ., Nat. Sci. 2007;46:274. [Google Scholar]

- Brożyna A. A. Jóźwicki W. Carlson J. A. Slominski A. T. Hum. Pathol. 2013;44:2071–2074. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masum M. N. Yamauchi K. Mitsunaga T. Reviews in Agricultural Science. 2019;7:41–58. doi: 10.7831/ras.7.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah S. Son S. Yun H. Y. Kim D. H. Chun P. Moon H. R. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016;26:347–362. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2016.1146253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescigno A. Sollai F. Pisu B. Rinaldi A. Sanjust E. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2002;17:207–218. doi: 10.1080/14756360210000010923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Videira I. F. d. S. Moura D. F. L. Magina S. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013;88:76–83. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962013000100009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T.-S. Materials. 2012;5:1661–1685. doi: 10.3390/ma5091661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rendon M. I. Gaviria J. I. Dermatol. Surg. 2005;31:886–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaita E. Lambrinidis G. Cheimonidi C. Agalou A. Beis D. Trougakos I. Mikros E. Skaltsounis A.-L. Aligiannis N. Molecules. 2017;22:514. doi: 10.3390/molecules22040514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns J. Pierard-Franchimont C. Pierard G. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2000;22:67–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2494.2000.00021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draelos Z. D. Dermatol. Ther. 2007;20:308–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakaya G. Türe A. Ercan A. Öncül S. Aytemir M. D. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;88:102950. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.102950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. T. H. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007;79:2277–2295. [Google Scholar]

- Şöhretoğlu D. Sari S. Barut B. Özel A. Bioorg. Chem. 2018;81:168–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi S. M. Emami S. Pharm. Biomed. Res. 2015;1:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Asadzadeh A. Sirous H. Pourfarzam M. Yaghmaei P. Afshin F. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2016;19:132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funayama M. Arakawa H. Yamamoto R. Nishino T. Shin T. Murao S. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 1995;59:143–144. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. Lee H.-e. Kim Y. J. Kim S. Y. Kim D.-S. Min K. H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:6943–6946. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plensdorf S. Livieratos M. Dada N. Am. Fam. Physician. 2017;96:797–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y. Hearing V. J. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2014;4:017046. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano F. Briganti S. Picardo M. Ghanem G. Pigm. Cell Res. 2006;19:550–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Muñoz J. L. Garcia-Molina F. Varon R. Garcia-Ruíz P. A. Tudela J. Garcia-Cánovas F. Rodríguez-López J. N. IUBMB life. 2010;62:539–547. doi: 10.1002/iub.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Borrón J. C. Solano F. Pigm. Cell Res. 2002;15:162–173. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2002.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabanes J. Chazarra S. Garcia-Carmona F. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1994;46:982–985. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1994.tb03253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. S. Wei C. I. Marshall M. R. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991;39:1897–1901. doi: 10.1021/jf00011a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nerya O. Musa R. Khatib S. Tamir S. Vaya J. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1389–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillaiyar T. Manickam M. Namasivayam V. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017;32:403–425. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1256882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Y. Baek N. Nam T.-g. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016;31:1–13. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2015.1004058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-J. Uyama H. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1707–1723. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5054-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolghadri S. Bahrami A. Hassan Khan M. T. Munoz-Munoz J. Garcia-Molina F. Garcia-Canovas F. Saboury A. A. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019;34:279–309. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1545767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzaiene N. N. Chaabane F. Sassi A. Chekir-Ghedira L. Ghedira K. Life Sci. 2016;144:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing V. J. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:467. doi: 10.1038/skinbio.2011.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. Y. Fisher D. E. Nature. 2007;445:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nature05660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loizzo M. Tundis R. Menichini F. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2012;11:378–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2012.00191.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo S.-Y. Sharma V. K. Sharma N. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:2837–2853. doi: 10.1021/jf020826f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slominski A. Tobin D. J. Shibahara S. Wortsman J. Physiol. Rev. 2004;84:1155–1228. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvez S. Kang M. Chung H. S. Cho C. Hong M. C. Shin M. K. Bae H. Phytother. Res. 2006;20:921–934. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillaiyar T. Manickam M. Jung S.-H. Drug Discovery Today. 2017;22:282–298. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cestari T. F. Dantas L. P. Boza J. C. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014;18:11–25. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K. Zhao D. Chen Y. Wei X. Li Y. Kong L.-M. Hider R. C. Zhou T. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017;10:2146–2155. doi: 10.1007/s11947-017-1976-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsunaga T. Yamauchi K. J. Wood Sci. 2015;61:351–363. doi: 10.1007/s10086-015-1476-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y. Jin W. Nazir Y. Fercher C. Blaskovich M. A. Cooper M. A. Barnard R. T. Ziora Z. M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;187:111892. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelini P. Venanzoni R. Angeles Flores G. Tirillini B. Orlando G. Recinella L. Chiavaroli A. Brunetti L. Leone S. Di Simone S. C. Antibiotics. 2020;9:513. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9080513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J.-C. Rho H. S. Joo Y. H. Lee C. S. Lee J. Ahn S. M. Kim J. E. Shin S. S. Park Y.-H. Suh K.-D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:4159–4162. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T. M. Ko H. H. Ng L. T. Hsieh Y. P. Chem. Biodiversity. 2015;12:963–979. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201400208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq M. Nazir Y. Ashraf Z. Rafique H. Afzal S. Mumtaz A. Hassan M. Ali A. Afzal K. Yousuf M. R. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019;34:1562–1572. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2019.1654468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh K. Poddar S. J. Microencapsulation. 2012;29:559–568. doi: 10.3109/02652048.2012.668955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn V. Pigm. Cell Res. 1995;8:234–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1995.tb00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promden W. Viriyabancha W. Monthakantirat O. Umehara K. Noguchi H. De-Eknamkul W. Molecules. 2018;23:1403. doi: 10.3390/molecules23061403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Ferrer Á. Rodríguez-López J. N. García-Cánovas F. García-Carmona F. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1995;1247:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(94)00204-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Duckworth H. W. Coleman J. E. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:1613–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)77137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kwon B. S. Haq A. K. Pomerantz S. H. Halaban R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987;84:7473–7477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Theos A. C. Tenza D. Martina J. A. Hurbain I. Peden A. A. Sviderskaya E. V. Stewart A. Robinson M. S. Bennett D. C. Cutler D. F. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:5356–5372. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e05-07-0626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bagherzadeh K. Shirgahi Talari F. Sharifi A. Ganjali M. R. Saboury A. A. Amanlou M. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2015;33:487–501. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2014.893203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wasmeier C. Hume A. N. Bolasco G. Seabra M. C. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3995–3999. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lai X. Wichers H. J. Soler-Lopez M. Dijkstra B. W. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018;24:47–55. doi: 10.1002/chem.201704410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Costin G.-E. Hearing V. J. FASEB J. 2007;21:976–994. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6649rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Buitrago E. Hardre R. Haudecoeur R. Jamet H. Belle C. Boumendjel A. Bubacco L. Reglier M. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016;16:3033–3047. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160216160112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S.-H. Kim K.-H. Koh J.-U. Kong K.-H. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2005;26:1135–1137. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2005.26.7.1135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asebi N. Nihei K. Tetrahedron. 2019;79:130589. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2019.130589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zubair R. Lyons A. B. Vellaichamy G. Peacock A. Hamzavi I. Dermatol. Clin. 2019;37:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Molina F. Munoz J. Varón R. Rodriguez-Lopez J. Garcia-Canovas F. Tudela J. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:9739–9749. doi: 10.1021/jf0712301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing V. Jiménez M. Pigm. Cell Res. 1989;2:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1989.tb00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]