Abstract

Kienböck's disease is a condition characterized by avascular necrosis of the lunate. It is also known as lunatomalacia and aseptic or ischemic necrosis of the lunate.

The aim of this work is to summarize and illustrate, through a case diagnosed in our institution, the radiological aspects of this rare entity, which occupy a prominent place in the diagnosis.

A better understanding of this recently described nosological entity and a wide dissemination of its diagnostic criteria, especially by radiologists, should facilitate the diagnosis and treatment of patients.

Keywords: Kienbock, Osteomalacia, Lunate

Introduction

The first description of aseptic osteonecrosis of the lunate was made in 1910 by an Austrian radiologist, Robert Kienböck [1]. It is a condition characterized by avascular necrosis of the lunate bone. It is also known as osteonecrosis, lunatomalacia and aseptic or ischemic necrosis of the lunate bone. Although the mechanisms by which this disorder develops are not fully understood, impaired bone vascularization is the most commonly proposed cause. This leads to infarction of the bone and ultimately mechanical failure. Kienböck's disease is often progressive, leading to joint destruction within 3-5 years if left untreated [1].

Case observation

A 43-year-old man, with no previous history, presented with rapidly progressive inflammatory pain of the dorsal aspect of the left wrist, not calmed by analgesic treatment, evolving during 8 months and justified multiple consultations with general practitioners, rheumatologists and orthopedists. The clinical examination on admission revealed a decrease in grip strength and moderate mechanical pain, exacerbated by dorsiflexion.

The patient was referred to us for MRI of the wrist, which showed a flattened heterogeneous lunate with a T1 hypointensity that was not enhanced after contrast injection and diffuse edema hyperintense on Proton-Density sequences (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(a) MRI of the left hand coronal PD Fat Sat sequence: collapsed lunate with heterogenic signal (star). (b) MRI of the left hand T1-weighted coronal sequence: collapsed lunate in hypointense in T1 (arrow). (c) MRI of the left hand sagittal PD Fat Sat sequence: collapsed lunate with heterogenic signal (star). (d) MRI of the left hand T1-weighted coronal sequence with fat suppression and gadolinium injection: collapsed lunate without significant enhancement (arrow).

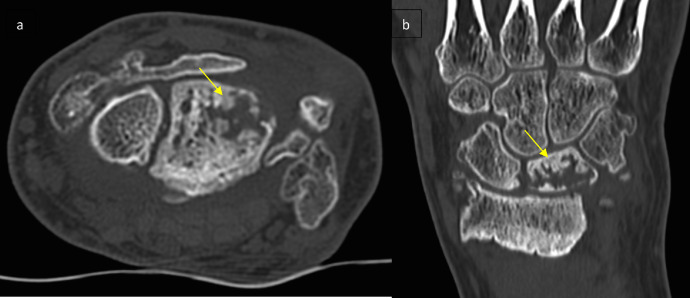

Additional CT scan revealed a fragmented lunate, as well as osteoarthritic changes and pinching of the radial carpal space with irregularity of the articular surface of the radial head correlatingwith a considerable secondary osteoarthritis (Fig. 2). No further investigation such as CT arthogram was performed for a better cartilage and ligament assessment.

Fig. 2.

CT scan of the left wrist in axial (a) and coronal (b) sections: fragmented and packed appearance of the lunate with arthrosic remodeling of the radiocarpal line (arrows).

The diagnosis of stage IV Kienböck disease was retained.

A type II lunate was associated with hamatolunate impingement with an extra facet between the lunate and the hamate (Fig. 2).

The patient was offered surgery and rehabilitation in a specialized center three weeks later, but for lack of financial means, refused treatment. In our Moroccan context, Kienbock's disease is still largely unknown, and therefore underdiagnosed, or discovered at a late stage.

Case discussion

Kienböck's disease or osteonecrosis of the lunate, described in 1910 by Robert Kienbock, remains a rare condition, the pathophysiology of which is not completely elucidated despite the development of imaging technics [2]. It is an avascular necrosis of the lunate that progressively evolves to carpal collapse [1].

Its prevalence in the general population is 0.5% and increases to 1.1%-2% in populations exposed to vibration (workers with jackhammers).

Kienböck's disease affects preferentially young men between 20 and 40 years of age. Bilateral lesions are rare (1.8%) [3].

The exact etiologies and pathophysiology are still poorly understood. The most obvious predisposing factor is the precarious vascularization of the lunate. Negativity of the inferior radio-ulnar index is considered by most authors to be a major predisposing factor for Kienböck disease. However, the pathogenesis of Kienböck disease remains multifactorial with genetic, anatomical, mechanical, and also metabolic involvement.

Clinical symptomatology is dominated by wrist pain, functional impotence, and decreased grip strength.

In the late stage, pain is more moderate and it's stiffness and loss of strength that dominate. Other signs such as wrist edema, sensory disturbances of the median nerve territory can be found [1].

The imaging is essential [3], indeed, it allows to confirm the diagnosis by objectifying a partial or total necrosis of the lunate, a settlement, a fragmentation or a collapse of the carpus [1]. It combines standard radiographs, CT scan and especially MRI.

The standard radiography allows to observe on the one hand modifications of the lunate such as densification, which will subsequently evolve towards a flattening until fragmentation of the lunate and on the other hand the adjacent environment such as disorganization of the carpus, pinching of the articular interlines essential for the assessment of the degree of the disease [1,4].

On CT, early remodeling of the lunate (small fracture lines, bone sclerosis, or early aplatization of the radial slope) is better appreciated, especially on multiplanar reconstructions. Later architectural remodeling can also be specified. Ct Arthrogram is useful for cartilage and ligament assessment [4].

Magnetic resonance imaging is an important complement to the diagnosis, showing early abnormalities when standard radiographs are still normal [1,4]. Indeed, at the early stage the affection is affirmed by an ischemic appearance of the bone on MRI with T1 hyposignal focused at the beginning at the superior-external part of the bone which seems quite specific of Kienböck disease. The T2 hyposignal is a sign of aggravation whether it is focal or total. At a more advanced stage, the bone is heterogeneous and subchondral geodes can be individualized especially at the proximal pole of the lunate. The injection of intravenous gadolinium during T1 sequences, allows to anticipate the prognosis: the enhancement after injection of the contrast medium allows to distinguish the areas susceptible to revascularization and those that are definitely necrotic. At a more advanced stage, fragmentation becomes evident: the MRI is thus of great importance in determining the evolutionary stage of the disease especially at the beginning of the affection [4].

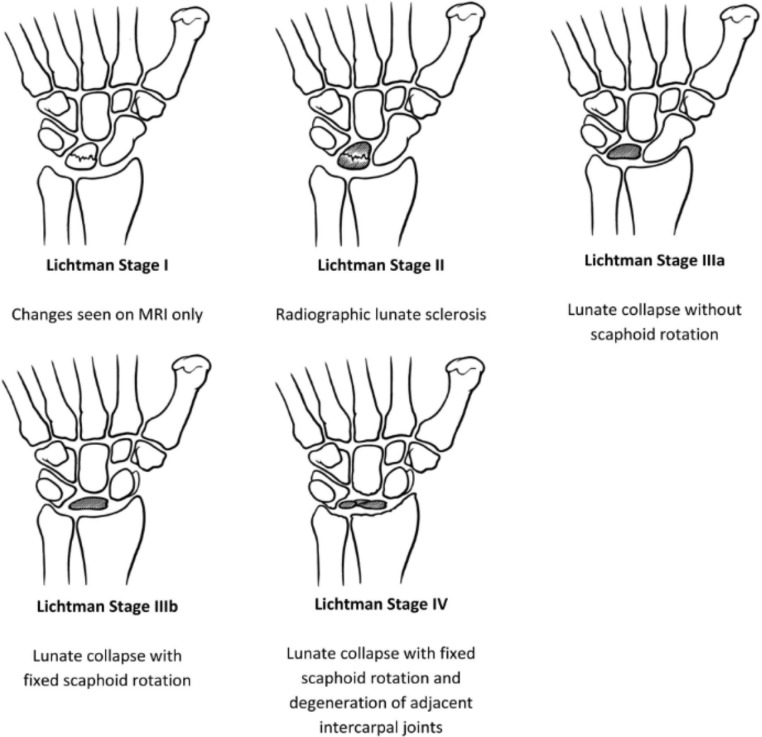

The various imaging techniques will make it possible to establish a classification, the most widely used of which is that of Lichtman. It is a reliable, reproducible classification with prognostic and therapeutic interest. It distinguishes 4 stages of increasing severity [1,4,5,7] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Classification of lunate lesions according to Lichtman during Kienbock's disease [7].

The discovery of the disease at the advanced stage in our patient can be explained by a neglect of the symptomatology that led to a diagnostic delay.

The natural course of Kienböck's disease is the gradual progression from stage I to stage IV over several years. There is not necessarily a correlation between clinical symptomatology and the severity of radiological signs [4].

Several treatments have been proposed, the aim of which is to obtain a flexible, mobile, painless wrist on the one hand but also to slow down the progression of the disease towards carpal collapse on the other hand [1,4].

In stage I, conservative treatment is proposed with immobilization combined with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that is offered to all patients and can be effective in relieving symptoms. It may be aided by a cast splint or external fixator for 3 months. The failure means that the disease would have already progressed to stage II [3,6]. In stage II, isolated length adjustments or in combination with revascularization are most often proposed. In early stages III, length adjustment associated with vascularized graft revascularization has become the most logical indication. In late stages III, depending on the result of the arthroscopy, either reconstruction by length adjustment and revascularization, or simple isolated unloading, or resection of the first row of the carpus in elderly subjects may be proposed. In stages IV where the arthrosis is global, either wrist denervation or complete wrist arthrodesis will be chosen [3].

Conclusion

Kienböck's disease is a rare pathology, the etiopathogeny of which remains poorly elucidated a century after its description. The symptomatology is aspecific, dominated by pain and functional impotence. Imaging diagnosis technics are essentials, combining standard radiographs, CT scan, and especially MRI, which will allow detection of the disease at an early stage of its evolution.

In some countries, Kienbock's disease is still widely unknown and therefore delay its diagnosis, making the treatment more challenging.

The imaging also makes it possible to classify patients into different stages determining the therapeutic modalities that range from a conservative treatment at the beginning to an arthrodesis or a complete denervation of the wrist in the advanced stages.

Patient Consent

Written, informed consent for publication of their case was obtained from the patient.

Authors’ contributions

All the above authors contributed on the writing of this manuscript or the lecture of the imaging studies.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Fontaine C. Kienböck´s disease. Chirurgie de la Main. 2015;34(1):4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2014.10.149. PubMed | Google Scholar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Facca S, Gondrand I, Naito K, Lequint T, Nonnenmacher J, Liverneaux P. Vol. 32. de La Main.; Chirurgie: 2013. pp. 305–309. (Graner ´s procedure in Kienböck disease: a series of four cases with 25 years of follow-up). PubMed | Google Scholar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathoulin C, Galbiatti A, Haerle M. Revascularisation du semi-lunaire associé à une ostéotomie du radius dans le traitement de la maladie de Kienböck. e-mémoires de l'Académie Nationale de. Chirurgie. 2006;5(2):50–60. Google Scholar. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamas C, Carrera A, Proubasta I, Llusa M, Majo J, Mir X. The anatomy and vascularity of the lunate: considerations applied to Kienböck ´s disease. Chir Main. 2007;26(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2007.01.001. PubMed | Google Scholar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldfarb CA, Hsu J, Gelberman RH. The Lichtman classification for Kienböck ´s disease: an assessment of reliability. J Hand Surg. 2003;28(1):7480. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2003.50035. PubMed | Google Scholar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nealey EM, Petscavage Thomas JM, Chew FS. Radiologic guide to surgical treatment of Kienbock ´s disease. Curr Probl Diagnostic Radiol. 2018;47(2):103–109. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2017.04.012. PubMed | Google Scholar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rioux-Forker D, Shin AY. Osteonecrosis of the Lunate: Kienböck Disease. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(14):570–584. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]