Abstract

Lactosylceramide (LacCer) in the plasma membranes of immune cells is an important lipid for signaling in innate immunity through the formation of LacCer-rich domains together with cholesterol (Cho). However, the properties of the LacCer domains formed in multicomponent membranes remain unclear. In this study, we examined the properties of the LacCer domains formed in Cho-containing 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylcholine (POPC) membranes by deuterium solid-state NMR and fluorescence lifetimes. The potent affinity of LacCer-LacCer (homophilic interaction) is known to induce a thermally stable gel phase in the unitary LacCer bilayer. In LacCer/Cho binary membranes, Cho gradually destabilized the LacCer gel phase to form the liquid-ordered phase by its potent order effect. In the LacCer/POPC binary systems without Cho, the 2H NMR spectra of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer and 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer probes revealed that LacCer was poorly miscible with POPC in the membranes and formed stable gel phases without being distributed in the liquid crystalline domain. The lamellar structure of the LacCer/POPC membrane was gradually disrupted at around 60°C, whereas the addition of Cho increased the thermal stability of the lamellarity. Furthermore, the area of the LacCer gel phase and its chain order were decreased in the LacCer/POPC/Cho ternary membranes, whereas the liquid-ordered domain, which was observed in the LacCer/Cho binary membrane, was not observed. Cho surrounding the LacCer gel domain liberated LacCer and facilitated forming the submicron to nano-scale small domains in the liquid crystalline domain of the LacCer/POPC/Cho membranes, as revealed by the fluorescence lifetimes of trans-parinaric acid and trans-parinaric acid-LacCer. Our findings on the membrane properties of the LacCer domains, particularly in the presence of Cho, would help elucidate the properties of the LacCer domains in biological membranes.

Significance

LacCer in immune cells is known to constitute the membrane domain in the presence of Cho in the innate immune response. LacCer bilayers tend to form tightly packed gel phases owing to LacCer's potent homophilic interaction, resulting in poor miscibility with POPC. LacCer/POPC/Cho membranes were not preferable to the formation of large liquid-ordered domains as seen in saturated phospholipids. As the Cho content increased, the LacCer gel domains became smaller. The small and ordered LacCer domains were dispersed into the POPC-based liquid crystalline phase, which may be related to the LacCer domains in biological membranes.

Introduction

Sphingolipids, which are known to be among the major lipids in cell membranes, are particularly involved in biologically functional domains together with cholesterol (Cho) (1). Glycosphingolipids (GSLs), a class of sphingolipids with an oligosaccharide headgroup, have been recognized as a specific marker of lipid rafts (2). GSL-enriched membrane domains are involved in cell-cell interactions through specific interactions of the headgroup carbohydrate moiety with the proteins or other carbohydrate clusters (3). The entry of pathogenic viruses and bacteria into host cells often initiates due to interaction with GSL-enriched lipid rafts (4).

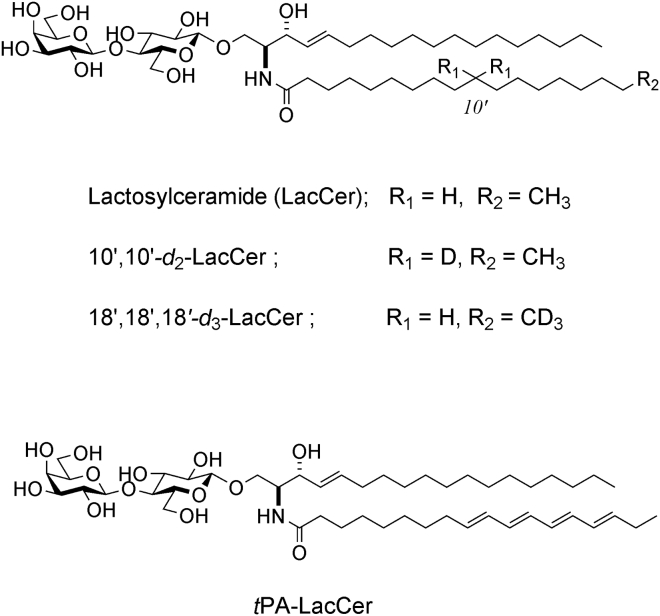

Lactosylceramide (LacCer), a neutral GSL with a Galβ1-4Glc headgroup (Fig. 1), is distributed in the plasma membrane of human neutrophils, intestinal epithetical cells, and skin (5). LacCer is not only a key intermediate molecule in the biosynthesis of gangliosides and other highly glycosylated GSLs but also has a pivotal role in immune responses by forming LacCer domains in cell membranes (6). LacCer-enriched microdomains act as infection receptors of Candida albicans by recognizing its surface β1,3-glucans (7,8). The entry of Mycobacterium tuberculosis into a host cell also uses the LacCer domains by interacting with the surface lipoarabinomannan (9). In their interactions with these fungal and bacterial glycans, LacCer domains are thought to transduce immune signaling through a Src family kinase Lyn located at the inner leaflet of these domains (10,11). Cho is also thought to be involved in this domain-mediated signaling because Cho depletion from the plasma membrane disturbs the phosphorylation of Lyn (12). LacCer with a C8 lipid chain has been reported to stimulate endocytosis through caveolae and induce microdomain formation (13), and be involved in the clustering and internalization of integrin (14). On the other hand, a stereoisomer of LacCer disrupts the downstream events initiated by GSLs, such as caveolae endocytosis and integrin signaling, probably by disturbing the formation of GSL domains (15).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of N-stearoyl-lactosylceramide (LacCer) and its analogs, 10′,10′-d2-LacCer and 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer, for solid-state 2H NMR and tPA-LacCer to probe the fluorescence lifetimes.

The lateral and intermembrane interactions of LacCer that involve phase states have been studied using model membranes to investigate the molecular basis for LacCer domains and their biological functions. A strong lateral LacCer-LacCer interaction has been evidenced by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms depicting the unitary LacCer membrane. For example, the phase transition temperature (Tm) from the gel phase to the liquid crystalline phase is approximately 80°C (16,17), which is close to the Tm of glucosylceramide (GlcCer) (18) and much higher than that of sphingomyelins (19). In binary membrane systems, Cho has shown a significant interaction with LacCer (20), and the LacCer-Cho interaction induced the formation of the liquid-ordered (Lo) phase (21). The lateral elasticity of LacCer/Cho membranes was higher than that of sphingomyelin/Cho and GalCer/Cho membranes, whereas the area-condensing effect of Cho on the LacCer hydrocarbon chains was not significant (20,21). On the other hand, Cho was not prone to associate with LacCer in ternary LacCer/POPC/Cho membranes under phase separation conditions (22). In terms of miscibility with phospholipids, the solid-state 2H NMR spectra of deuterated dihydroLacCer in dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) membranes showed high miscibility to form the liquid crystalline (Ld) phase at 30°C (23). LacCer induced intermembrane adhesion in supported phospholipid bilayers (24). Furthermore, DMPC bilayers, including >10 mol% LacCer, pulled the LacCer membranes on the other face closer, likely due to the interactions between the headgroup carbohydrates (25). A similar observation was reported for LewisX in DPPC membranes (26). Although several important findings regarding LacCer on lateral lipid interactions have been reported, the details of the LacCer domains under the phase-separated conditions mostly remain unclear.

In this study, we examined the lateral interaction of N-stearoyl LacCer (simply referred to as LacCer unless otherwise stated) in bilayer membranes including Cho, using deuterated LacCer probes (Fig. 1). In binary membranes, the miscibility of LacCer with Cho was confirmed by DSC thermograms. Solid-state 2H NMR using 10′,10′-d2-LacCer (Fig. 1) revealed the formation of the Lo phase at temperatures ≥40°C in LacCer/Cho 50:50 membranes. On the other hand, the microscopic observations and fluorescence lifetime experiments with trans-parinaric acid (tPA) and tPA-LacCer (Fig. 1) indicated the poor miscibility of LacCer with POPC in LacCer/POPC 25:75 membranes. We then proceeded to the phase-separated ternary membranes composed of LacCer/POPC/Cho, where the LacCer/Cho ratio was different, whereas that of POPC was unchanged at 65 mol%. Microscopy and tPA lifetimes indicated that LacCer formed gel domains at lower temperatures (23°C and 25°C) in low Cho content of 9 and 13 mol%, respectively (LacCer content, 26 and 22 mol%, respectively), whereas no phase separation was observed when Cho was increased to 20 mol% (LacCer, 15 mol%). By contrast, the 2H NMR spectra of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer clearly showed that significant numbers of LacCer molecules were distributed in the Ld phase under the gel/Ld phase separation conditions. In the ternary membranes containing POPC, Cho decreased the size of the LacCer gel domain, but did not form the typical LacCer-Cho Lo domain observed in the LacCer/Cho binary membrane. Due to the potent LacCer-LacCer interaction, Cho may facilitate the formation of very small LacCer domains distributed throughout the POPC-rich Ld domain. These results support the idea that the ordered and submicron to nanometer size domains formed by LacCer are expected to occur in biological membranes.

Materials and methods

Materials

N-Stearoyl LacCer and 1-O-palmitoyl-2-O-oleoyl-sn-glycerophosphocholine (POPC) were obtained from Avanti Polar lipid (Alabaster, AL, USA). Cho was obtained from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). Bodipy-PC was obtained from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA, USA). tPA was synthesized according to a previous report (27). 10′,10′-d2-LacCer, 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer, and tPA-LacCer were synthesized in our laboratories; see the Supporting material for details.

Differential scanning calorimetry

DSC was performed using Nano-DSC (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). The vesicle samples were prepared according to a previous report (28). Briefly, an appropriate molar ratio of LacCer and Cho in chloroform/methanol (4:1) was evaporated under a nitrogen stream and then dried under a high vacuum for at least 12 h. The residual lipid film was dispersed into Milli-Q water and incubated for 30 min at 80°C with intermittent vortex mixing and occasional sonication. Then, 500 μL of the bilayer sample was degassed under centrifugation and injected into a DSC cell. The heating scans were performed from 40°C to 90°C with a linear increment of +0.5°C/min.

Solid-state 2H-NMR

Multilamellar vesicles (MLVs) for the NMR sample were prepared as described previously (28). The solution of deuterated LacCer and the other lipids (200 nmol in total) in methanol-chloroform (1:3) was prepared. The organic solvent was removed, and the obtained lipid film was further dried for at least 12 h under a high vacuum. The resulting lipid film was hydrated with Milli-Q water (30 times for the weight of the dried lipids) and vortexed at 65°C. The sample was then freeze-thawed several times, and the suspension was lyophilized. The lipid film was rehydrated with deuterium-depleted water purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA) to be 50% moisture (w/w), and then freeze-thawed several times. The sample was then transferred into a Kel-F insert tube for 4-mm Bruker MAS rotors, and the screw cap of the tube was sealed tight with epoxy glue.

Solid-state 2H-NMR spectra were collected with a 400-MHz spectrometer (AVANCEIII 400, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) equipped with a 4-mm 2H static probe. To observe the 2H quadrupole splitting pattern under the static conditions, a solid-echo pulse sequence (29) was used with a 90° pulse width set to 4.2 μs; the solid-echo delays were set to 30 μs and 24 μs, and the recycle delay was set to 0.5 s, respectively. The sweep width was set at 250 kHz with 4k points for 10′,10′-d2-LacCer and 8k data points for 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer, and the number of scans was ∼100,000. FID data was Fourier transformed upon exponential multiplication.

The order parameter (SCD) is highly related to the observed value of the quadrupolar coupling (Δν), as in the following equation (30,31):

| (1) |

where e2qQ/h is the value of the quadrupolar coupling constant (167 kHz for 2H in a C-2H segment), and SCD corresponds to the chain order parameter for the deuterated methylene positions relative to the principal ordering axis. The SCD is reduced to half by the rotation averaging around the ordering axis that intersects the C-D bond vector of the methylene segments at 90°. The terminal CD3 group undergoes fast rotation along with the C-CD3 bond. Therefore, SCD of the CD3 group (SCD3) is expressed as SCD = −3 SCD3 (30).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Giant unilamellar vesicles (GUVs) were prepared using the electroformation method (32). Briefly, a solution of the lipid mixture with 0.2 mol% Bodipy-PC in chloroform/methanol (1:1; 5–10 μL, 1 mg/mL) was spread on the surface of the platinum electrodes. The electrodes' surface was coated by the thin lipid film by drying it under a high vacuum for at least 18 h. The parallel electrodes were then put into Milli-Q water (400 μL) sandwiched between two cover glasses (24 mm × 60 mm, 0.12–0.17 mm thickness) using an open-square-shaped rubber spacer (1 mm thickness). The chamber was fixed on a temperature-controlled sample stage (Thermo plate, Tokai Hit, Shizuoka, Japan) and incubated at 55°C for 45 min, and a low-frequency alternating current (sinusoidal wave function, 10 Vpp, 10 Hz) was applied by a function generator (Santa Clara, CA, USA). After the formation of GUVs, the sample was gradually cooled to 25°C, equilibrated for 20 min, and then warmed up to the selected temperatures.

Fluorescence observations were conducted using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1000-D IX81, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Bodipy-PC (33) was excited at 488 nm. A laser scanning rate of 2.0 μs/pix was used for the acquisition of the confocal images (512 pix × 512 pix).

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements

Time-resolved fluorescence measurements were performed as follows [34]. The appropriate amount of lipids (200 nmol in total) in methanol was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen gas on a heating block (45°C) and further dried overnight under a high vacuum. The lipid film was hydrated with the argon-purged Milli-Q water (2 mL) and incubated at 75°C for 60 min. The sample tube was then vortexed and sonicated at 75°C for 5 min. tPA or tPA-LacCer (2 nmol) in methanol (the final methanol concentration was less than 1%) was added to the vesicle suspension, and the mixture was again vortexed and sonicated at 75°C for 5 min. The sample was gradually cooled to the ambient temperature over 30 min. tPA in MLVs were excited at 298 nm, and the emission was measured at 405 nm. The tPA fluorescence lifetime was collected using a FluoTime 200 spectrometer (PicoQuant, Berlin, Germany), with a PicoHarp 300E time-correlated single photon-counting module. Data acquisition and analysis were performed with FluoFit Pro software (PicoQuant). The average lifetime <τ> was expressed as follows (34):

| (2) |

where αi represents the amplitudes of the components, and τi indicates the decay times of each component. The experimentally obtained emission decay curves were initially resolved into three different lifetime components by the best fitting of the exponential decays, namely long (τ1), medium (τ2), and short (τ3), and reconstructed to the average lifetime according to Eq. 2, which can be related to the chain orders in the nanosecond time scale (35).

Results

Miscibility of Cho in LacCer membranes

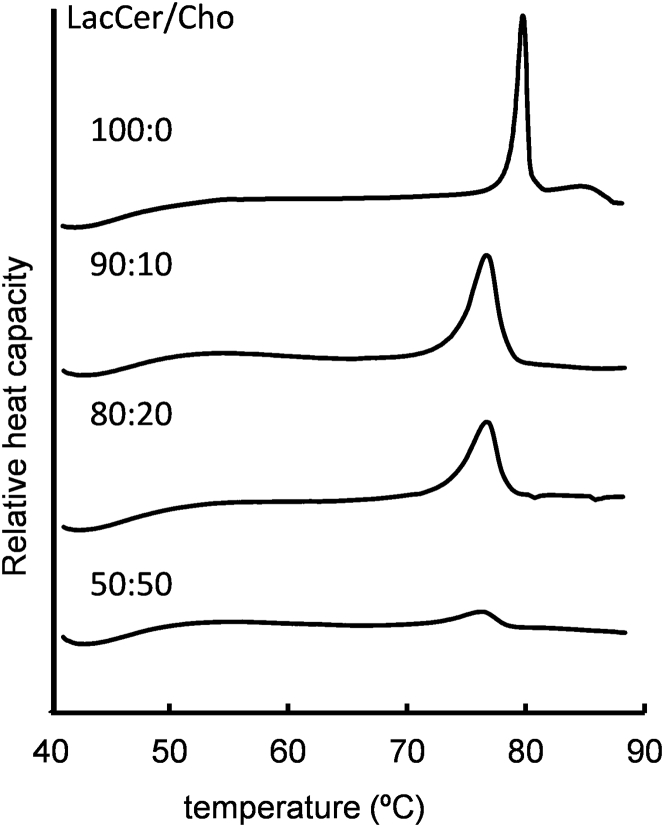

The miscibility of Cho in LacCer membranes was examined on DSC thermograms (Fig. 2). The DSC thermogram of the unitary LacCer membrane showed a relatively broad endothermic peak at 77.8 ± 0.5°C with the full-width at half-minimum (T1/2) in 1.5 ± 0.5°C, and a small endothermic peak ranging from 81°C to 86°C, similar to previous reports (16,17). The high phase transition temperature in the gel to liquid crystalline phase indicates the potent interaction of the lateral LacCers. Saxena et al. reported that the acyl chains of LacCer had multiple phase states, such as differences in chain tilt and hydration among the bilayer polymorphs, based on their x-ray scattering results (16). These multiple chain states are assumed to provide the small endothermic peak near the main transition peak. When added with Cho at 10 and 20 mol% to the LacCer membranes, a broader endothermic peak was observed at 76.4 ± 0.3°C, and 76.3 ± 1.2°C, respectively. The temperature of the main transition peak of 20 mol% Cho fluctuated between 75°C and 78°C even after several heating-cooling steps. The main transition peak consists of some subpeaks, and changes in their distribution on the heating-cooling cycles are assumed to relate to the fluctuations. The endothermic profiles indicate that the tight chain packing of LacCer was slightly disrupted by the addition of Cho. Cho was miscible to a certain extent in LacCer membranes and reduced the thermodynamic stability of the gel phase of LacCer. However, the decreased intensity in endothermic peaks due to the Cho addition was not remarkable compared with the saturated PC membranes. The reason is that LacCer forms a gel phase with moderate cooperativity even in the presence of Cho. This point is also discussed in the sections on NMR and fluorescence lifetime. In addition, the subendothermic peak above the main transition disappeared with the addition of Cho. Cho has an effect to promote homogenization of the multiple metastable gel phases of LacCer. Furthermore, a small endothermic peak was observed for LacCer membranes with an equimolar mixture of Cho probably because a small gel fraction remained around 75°C. The increase of the peak width suggests that Cho affected the potent LacCer-LacCer interaction and turned the LacCer gel phase mostly into the fluid phase in the 50:50 ratio. However, the effect of Cho in reducing the cooperativity of the gel phase was considerably smaller than when using sphingomyelin or saturated PC. The phase state was further examined by solid-state 2H NMR experiments, and the fluid phase in 50:50 LacCer/Cho membranes was demonstrated to be the Lo phase, as outlined in the following sections.

Figure 2.

DSC thermograms of LacCer membranes with Cho at 100:0, 90:10, 80:20, and 50:50 molar ratios of LacCer/Cho.

Gel-eliminating and chain-ordering effects of Cho in LacCer membranes

The ordering effect of Cho on the LacCer hydrocarbon chain was examined on solid-state 2H NMR using 10′,10′-d2-LacCer (Fig. 1). The deuterated segment at the 10′ position of the stearoyl chain of LacCer was assumed to receive the highest ordering effect from Cho based on the previous result using sphingomyelin (36,37).

As shown in Fig. 3, membranes with a 50:50 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/Cho ratio at 20°C and 30°C mostly showed broad signals, whereas a small amount of the Pake doublet with quadrupolar couplings larger than 50 kHz was observed at 30°C, and it became significant at ≥40°C. These spectra indicate that the mobility of the acyl chain of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer was highly restricted at ≤ 30°C. On the other hand, the gel phase to the Lo phase transition started at around 30°C. Note that some gel fraction of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer coexisted at 40°C.

Figure 3.

Solid-state 2H NMR spectra of membranes with a 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/Cho 50:50 ratio to examine the chain ordering and gradual phase transition from gel phase to the Lo phase. The intensity of the isotropic peaks adjusted the vertical axes. The center peak originates from the remaining deuterium in water.

The 2H NMR spectra indicate that the LacCer acyl chain received the strong ordering effects of Cho. The coupling values revealed that the membranes with a 50:50 LacCer/Cho ratio at ≥40°C were mostly in the Lo phase because the values were close to the previous results of the membranes with a 50:50 10′,10′-d2-stearoyl-sphingomyelin/Cho ratio (52.9 kHz at 40°C) in the Lo phase (38). The potent Cho effect to destabilize the gel phase has been reported in the sphingomyelin/Cho membranes; for example, the Pake pattern of a 50:50 10′,10′-d2-sphingomyelin/Cho membrane appeared at 10°C (38). Although LacCer and sphingomyelin have a common ceramide moiety, the Cho effect on destabilizing the LacCer gel phase was much smaller, probably due to the potent LacCer-LacCer interactions. The temperature-dependent slope of the quadrupolar couplings of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer, showing a value of −0.15 (R2: 0.96) with the approximation of a linear function (Fig. S1), was slightly steeper in comparison with the value of −0.13 (R2: 0.99) shown in membranes with a 50:50 10′,10′-d2-sphingomyelin/Cho ratio (35,38). The thermal stability of the LacCer Lo phase in this binary system was slightly lower in comparison with the sphingomyelin Lo phase, possibly due to the difference of the headgroup structures.

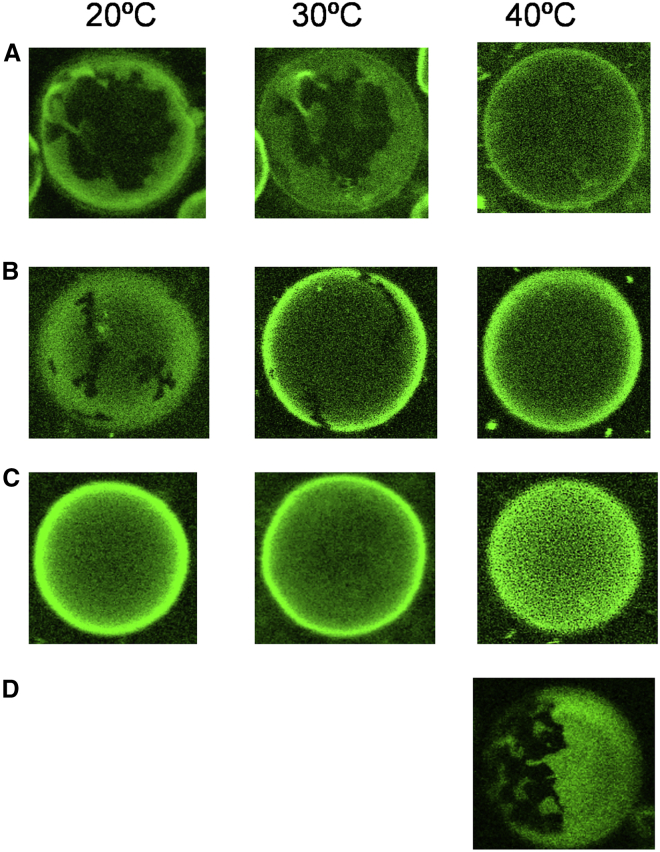

Phase separation of LacCer in POPC membranes

The extracellular leaflet of cell membranes is composed of sphingolipids such as sphingomyelin and GSLs, including LacCer as well as the unsaturated PCs such as POPC. The phase separations of LacCer in binary LacCer/POPC and ternary LacCer/POPC/Cho membranes were examined on confocal microscopy with GUVs composed of LacCer/POPC/Cho with Bodipy-PC for the marker of the liquid disordered (Ld) domains (Fig. 4). As shown in Fig. 4 D, phase separation was observed in membranes with a 25:75 LacCer/POPC ratio at 40°C. The dark condensed areas with irregular boundaries consisted of dense LacCer domains probably in the gel phase. In LacCer/POPC/Cho systems, 35 mol% of the total lipids was composed of three different ratios of LacCer and Cho, namely at 3:1 (approximately 26:9), almost 3:2 (approximately 22:13), and 3:4 (15:20), whereas the fraction of POPC was fixed at 65 mol%. As shown in Fig. 4 A, phase separation into dark areas and a green Ld domain were observed at both 20°C and 30°C in the membranes with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 26:65:9. The irregular shape of the dark areas indicates that LacCer is prone to form a gel-like domain. Similar shapes of the domains were also reported in the membranes of GlcCer/POPC/Cho (39) and galactosylceramide (GalCer)/dialuroyl phosphatidylcholine/Cho (40). By contrast, when N-stearoyl sphingomyelin was used instead of LacCer in the membranes with an N-stearoyl sphingomyelin/POPC/Cho ratio of 26:65:9, a clear phase separation with round-shaped domains was observed (Fig. S2).

Figure 4.

Microscopic images of GUVs composed of membranes with LacCer/POPC/Cho ratios of 26:65:9 (A), 22:65:13 (B), and 15:65:20 (C), and LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75 (D). Bodipy-PC was included at 0.2 mol% to visualize the GUVs. To see this figure in color, go online.

The effects of Cho on LacCer/POPC were evaluated using a 25:75 LacCer/POPC ratio compared with a 22:65:13 LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio, both of which had a 1:3 LacCer/POPC ratio. In membranes with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13, the area of the gel-like domains observed at ≤30°C disappeared at 40°C (Fig. 4 B). In comparison with Fig. 4 D, an addition of 13 mol% Cho markedly destabilized the LacCer gel-like domains to coalesce the gel and Ld phases at 40°C. Upon a further increase in Cho concentration, the LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 15:65:20 showed no clear phase segregation even at 20°C (Fig. 4 C). The phase state was further examined by 2H NMR and fluorescence lifetimes.

Application of 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer in the detection of gel phase by 2H NMR

Static 31P NMR spectrum changes in the 31P-chemical shift anisotropy of phospholipids are usually used for checking the formation of lamellar bilayers but cannot be adopted for GSLs. Therefore, the lamellarity of LacCer was also examined by the 2H NMR spectrum of the POPC-containing membrane. We first examined a membrane with 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/POPC 25:75 at 40°C, but the restricted motion of the LacCer hydrocarbon chains in the gel phase markedly broadened the NMR signal, which often becomes indistinguishable from the baseline undulation (Fig. 5 A). When 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer was used, the higher motion of the terminal −CD3 group enabled the detection of 2H NMR signals with the typical shape in the gel phase (Fig. 5 B). The 2H NMR signal of the terminal -CD3 is typically observed at a higher intensity with narrow splitting widths (41). The coupling widths from 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer depend on the order of the C-CD3 bond because of the rapid rotation of the -CD3 group. The rotation at the cone angle of C-CD3 is known to reduce the splitting width by a factor of 1/3 from the corresponding widths of the virtual methylene group in the same phase and position (30,42). The 2H NMR signals from these LacCer probes indicated that LacCer in a LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75 mostly resided in the gel phase, and hardly mixed with the POPC-based Ld phase at ≤40°C. When the temperature was increased to 60°C, the small doublet of 9.1 kHz (10′,10′-d2-LacCer; Fig. 5 A), which was less than half the usual coupling width originated from the lamellar Ld membranes (38), and 1.2 kHz (18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer; Fig. 5 B) overlapping with an intense central peak were observed. We assumed that the lamellar structure of LacCer was collapsed, and other phases such as hexagonal, cubic, and micelle coexisted in these conditions. This is in sharp contrast to the case of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer in DMPC membranes (10′,10′-d2-LacCer/DMPC 10:90). LacCer was miscible in the DMPC bilayer to give a Pake doublet in 27.3 Hz at 30°C (Fig. S3).

Figure 5.

The 2H NMR spectra of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer (A) and 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer (B) in membranes with a LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75. The inset spectra in panel B provide enlarged views of the center peak. The spectral intensity was normalized to that at 60°C except for 30°C in panel B, which was magnified two times. The sharp center peaks in panels A and B likely originate from residual deuterium in water and/or the deuterated lipids in micelles or a cubic phase.

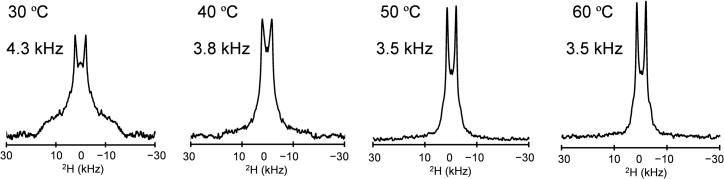

By contrast, Pake doublet peaks of 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer were observed at all measured temperatures in the 50 mol% Cho-containing bilayers (Fig. 6). In the presence of high concentrations of Cho, at 50°C and 60°C, LacCer formed a bilayer structure similar to the Lo phase of sphingomyelin because the doublet widths around 4.3 kHz–3.5 kHz were similar to that of 18′,18′,18′-d3-N-stearoyl-sphingomyelin/Cho 50:50 (3.5 kHz at 45°C) (36). The doublet widths were much smaller than that of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer due to a significant increase in the mobility of the chain terminal in addition to the scaling. These results show that LacCer stably formed bilayers in the presence of Cho, which was the case with the three-component bilayers. The broad 2H NMR signals coexisting with the Pake doublet at 30°C and 40°C indicate the presence of both gel and Lo phases. These results demonstrate that deuterium-labeled lipids at the terminal methyl group comprise a useful NMR probe for examining lamellarity and the phase state of lipid dispersions, particularly those of higher melting points.

Figure 6.

2H NMR spectra of 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer in membranes with an 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer/Cho ratio of 50:50. The poor S/N ratios at 30°C and 40°C show that the 2H signal intensity was very low, where LacCer largely forms in the gel phase.

2H NMR of the LacCer acyl chain in ternary membranes

The deuterated LacCer probes were adopted for examining the phase state and chain ordering of LacCer in LacCer/POPC/Cho membranes (Figs. 7 and S4). As shown in Fig. 7 A, a Pake doublet was observed in the membrane with a 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 26:65:9 and a quadrupolar coupling width of 32.6 kHz at 30°C thought to have an origin from the Ld phase. On the other hand, the spectral pattern of the bilayer with an 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 26:65:9 that is shown in Fig. 7 D can be interpreted by the superposition of a broadened signal from the gel phase and a Pake doublet from the fluid phase, consistent with the microscopic observation (Fig. 4 A). The addition of Cho to LacCer/POPC membranes enabled a part of LacCer to be distributed in the Ld phase. Further increases in the Cho concentrations in the systems with 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/POPC/Cho ratios of 22:65:13 (Fig. 7 B) and 15:65:20 (Fig. 7 C) also afforded Pake doublets originated from the fluid phases. Furthermore, the membranes with 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer/POPC/Cho ratios of 22:65:13 (Fig. 7 E) and 15:65:20 (Fig. 7 F) afforded a negligible fraction of broad signal due to the gel phase. Therefore, LacCer was mostly distributed in the Ld phase in these membranes through increased miscibility with POPC in the presence of Cho. The Cho effect also increased the coupling widths of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer in a Cho concentration-dependent manner, showing that the ordering effect of Cho properly worked in this system (Fig. 7 G).

Figure 7.

Solid-state 2H NMR spectra and the quadrupolar coupling widths (Δν) of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer (A–C) and 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer (D–F) in LacCer/POPC/Cho bilayers at 30°C. The other spectra using 10′,10′-d2-LacCer and 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer are shown in Figs. S4–S7. (G) The Δν values of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer in membranes with a 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 26:65:9 (diamond), 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13 (triangle), and 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 15:65:20 (circle) in each temperature. The center peak was largely originated from the residual HDO.

Fluorescence lifetime of tPA and tPA-LacCer

tPA is a fluorescent lifetime probe that preferentially distributes into highly ordered lipid domains, including gel domains, and sensitively detects the rapid dynamics of the surrounding lipids on the nanosecond scale (35,43). The lifetime of tPA in the Ld phase is very short (<5 ns), whereas it becomes very long (>40 ns) in the highly ordered gel phase. Therefore, the probe is suitable for the analysis of highly ordered GSL domains in POPC membranes. In these lifetime experiments, we focused on the tPA lifetime in the systems with LacCer/POPC/Cho ratios of 22:65:13 and 15:65:20, where LacCer was suggested to largely occur in the Ld phase based on the 2H NMR spectrum, compared with the system with a LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75, where LacCer resides in the gel phase.

The fluorescence lifetime of tPA in the membranes with a LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75 was measured at 30°C, and the long lifetime component was approximately 40 ns, which indicated the presence of gel domains (Fig. 8 A) (44). The lifetime of the long lifetime component was decreased with increasing temperatures. Similar long lifetime components were observed in the membrane with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13 (Fig. 8 B) because of the presence of the LacCer gel domains. On the other hand, the average lifetimes of the membrane with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13 at <50°C were much shorter than those of membranes with a LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75. Therefore, Cho decreased the fraction of the long lifetime component of the tPA residing in LacCer gel domains, which decreased the average lifetime in the POPC membrane. The significantly shorter lifetimes of the long and average components were observed in the membranes with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 15:65:25, indicating that the LacCer gel domains disappeared because Cho further increased the partition of LacCer into the Ld phase (Fig. 8 C).

Figure 8.

The temperature-dependent change in fluorescence lifetimes of the tPA in the membranes with a LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75 (A), LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13 (B), and LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 15:65:20 (C). Long lifetimes are shown as filled circles, and average lifetimes are shown as blank squares. tPA at 1 mol% was included in the membranes. Each value is the mean ± SEM for n = 3.

To further examine the LacCer gel domains, we measured the fluorescence lifetime of tPA-LacCer (Fig. 1). tPA-LacCer is a lifetime probe mimicking LacCer in structure, where an acyl chain is substituted with tPA. Previously, tPA-sphingomyelin and tPA-sulfatide were developed to mimic not only the chemical structure but also the membrane physicochemical property of the original sphingolipids; thus, these probes were successfully used to examine the corresponding sphingolipid domains (45,46). Therefore, we assumed that tPA-LacCer would be a good probe to unveil the membrane property of LacCer by mimicking the domain partitions.

The long and average lifetimes of tPA-LacCer in the LacCer/POPC membranes are shown in Fig. 9. In the membrane with a LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75, LacCer resided in the gel domain at 23°C and 33°C because the long lifetime components showed extremely long lifetimes that further exceeded 40 ns (Fig. 9 A). Furthermore, the average lifetimes were much longer than those used in the tPA probe (Figs. 9 B and 8), indicating that the tPA-LacCer was largely included in the LacCer gel domain. The long lifetime component of >50 ns from the gel domain was still observed at 50°C. In the membrane with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13, the long lifetime component of 52 ns with an average lifetime component of >20 ns was observed at 23°C. The results suggest that tPA-LAcCer was mostly involved in the gel domain at this temperature. On the other hand, the tPA-LacCer in the gel phase was almost eliminated at 33°C and 50°C. In the membrane with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 15:65:20, the long lifetime component of approximately 10–20 ns was observed, likely from the intermediately ordered phase, which was not observable on microscopy and solid-state 2H NMR. These intermediately ordered domains are assumed to be associated with small submicron-scale domains dispersed in the Ld domains.

Figure 9.

The long (A) and average (B) lifetimes of tPA-LacCer in membranes with a LacCer/POPC ratio of 75:25 and LacCer/POPC/Cho ratios of 22:65:13 and 15:65:20. The lifetimes were collected at 23°C (white bar), 33°C (black bar), and 50°C (gray bar), respectively. tPA-LacCer at 1 mol% was included. Standard deviations are shown with a gray line.

Discussion

The Cho effect in the domain formation by GlcCer and GalCer in ternary model membranes has been reported (39,40), although similar reports for LacCer are extremely limited despite its biological significance. LacCer, having a neutral Gal(β1-4)Glc headgroup, forms a thermally stable gel phase through the potent homophilic interaction but showed relatively low cooperativity in the DSC thermogram (Fig. 2). The similar phase transition peak of GlcCer at 85°C (19) suggests the galactose extension on GlcCer was not significant for the thermostability of the tight GSL-GSL interaction and cooperativities. The low condensing effect of Cho on the LacCer monolayer was reported (21), and DSC results revealed that Cho decreased thermostability and cooperativity of the LacCer gel phase to a certain degree (20,21).

2H NMR spectroscopy using deuterated lipid probes has been adopted to examine the lamellar bilayer structure, lipid chain ordering, and phase states because the signal patterns and quadrupole coupling in the spectra sensitively reflect the mobility and orientation of lipid molecules in bilayers (47). In this study, we developed new deuterated LacCer probes with a position-selective deuteration, which can precisely reproduce the membrane properties of the original lipid (36,48). When we used 10′-deuterated probes, only the nearly all-trans for the chain conformation in the Lo phase could induce the doublet width over 50 kHz (36). The LacCer-Cho interaction promotes the formation of the Lo phase in 50 mol% Cho concentration, as shown on the doublet widths in 2H NMR spectroscopy at ≥40°C (Fig. 3). The gradual change of the 2H NMR spectra from 20°C to 40°C (Fig. 3), and the gradual change of the DSC endothermic profile (Fig. S8) consistently indicate the coexistence of the gel phase and the Lo phase within the temperature range. The temperature-dependent slope of the quadrupolar coupling width of 10′,10′-d2-LacCer (Fig. S1) was slightly different from that of 10′,10′-d2-sphingomyelin/Cho (38), indicating that LacCer had received a significant order effect from Cho to form the Lo phase with high thermal stability, whereas the effect was weaker than that of sphingomyelin. The 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer, which furnished three deuterium atoms on the methyl group at the acyl-chain terminal, allowed the 2H NMR signal to be observable at higher intensity at 30°C because of the higher mobility of the terminal CD3 group even in the gel phase (Figs. 5 and 6). In LacCer/POPC membranes with a ratio of 25:75 (Fig. 5), the broad deuterium signals of 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer at 30°C or 40°C and 10′,10′-d2-LacCer at 40°C reflect the low mobility in the gel phase, thus revealing that POPC hardly interferes with the homophilic association of LacCer with gel formation in the absence of Cho, as previously reported in Langmuir monolayer experiments of dioleolyphosphatidylcholine/LacCer (49). This is a sharp contrast to the sphingomyelin-containing bilayers, where a clear Pake doublet derived from 10′,10′-d2-sphingomyelin was observed under the phase transition temperatures because sphingomyelin was miscible with dioleolyphosphatidylcholine to a certain extent (50). Furthermore, the intense center peak and small doublet signal have appeared in the spectra of 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer/POPC and 10′,10′-d2-LacCer/POPC at higher temperatures, suggesting that the lamellar structure of LacCer was collapsed and LacCer probably resides outside the POPC bilayer by forming smaller vesicles, micelles, cubic phase, or partially as an inverted hexagonal phase. It is assumed that the thickness of POPC membranes surrounding the LacCer gel phase can be decreased with increasing temperature (51), resulting in the destabilization of the LacCer gel phase. These LacCer gel domains possibly formed specific phases and may play a role in forming the spontaneous curvature or tube-like assembly that may regulate the activity of the membrane proteins in biological membranes (52,53). However, more extensive research is needed to understand the relationship between morphology and biological function. On the other hand, the Pake patterns suggested that the LacCer lamellar structure was retained in membranes with an 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer/Cho ratio of 50:50 (Fig. 6).

As is often shown for other high-melting-point lipids like sphingomyelin, Cho reduces the cooperativity of the LacCer gel phase and facilitates the formation of the Lo phase in the LacCer/Cho binary membranes. By contrast, large Lo domains were not observed in the phase-separated ternary membrane systems. The temperature-dependent changes of the 2H NMR spectra in the transition from the gel phase to the fluid phase and widths of the Pake doublet were reversible under most conditions of the lamellar bilayers. However, the spectral changes were not reversible once micelle and other phases were formed (these were observed in 25:75 LacCer/POPC membranes). In the membranes with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 26:65:9, the irregular shape of the dark areas observed on microscopy (Fig. 4 A) was confirmed to be the gel domain of LacCer by 2H NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 7 D). On the other hand, phase separation with the formation of round-shaped domains in GUVs was comprised of membranes with a sphingomyelin/POPC/Cho ratio of 26:65:9 (Fig. S2). In the membranes with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13, the LacCer gel domain became smaller (Fig. 4 B) and increased the LacCer distribution into the Ld phase (Fig. 7 B and E). This is in sharp contrast with the membranes with a LacCer/POPC ratio of 25:75, where LacCer was mostly distributed in the gel phase. When the Cho ratio to a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 15:65:20 was further increased, the LacCer gel domain disappeared (Fig. 4 C); thus, LacCer was mostly mixed in the POPC bilayers (Fig. 7 C and F). These results suggest that Cho decreases the cooperativity of the LacCer gel domain, likely liberating the small LacCer domains into the POPC bilayers. These small LacCer domains were detected in the tPA lifetime experiments. On the other hand, the Lo domain was not detected because small and tight LacCer domains do not favor Cho.

We adopted the tPA fluorescence lifetime experiment to detect the ordered domains in LacCer-containing membranes because the much shorter timescale of this experiment (35) was appropriate for examining small LacCer domains. In a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13, the size of LacCer gel domain decreased when increasing the temperature, and the small LacCer domains were assumed to be dominant in this composition because of the long lifetime component of tPA (Fig. 8 B), at which the LacCer domains were not observed on microscopy under these conditions (Fig. 4 B). However, the tPA fluorescence lifetime may overestimate the ordered component because of its preferable partitions into the ordered domains. Another experiment for the bilayers with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 22:65:13 using tPA-LacCer (Fig. 9 A) showed the long lifetime of tPA-LacCer in 18 ns at 33°C, assumed to be originated from the intermediately ordered small domains. The longer lifetimes of tPA-LacCer in the membrane with a LacCer/POPC/Cho ratio of 15:65:20 also suggests that tPA-LacCer was involved in the small and ordered LacCer domains, which were too small to observe under microscopy. Furthermore, the existence time of the small LacCer domains was shorter than the timescale of 2H NMR, so it could be less than tens of microseconds. The elongation of one Gal unit to GlcCer did not show a significant improvement in the formation of the macroscopic Lo domain with Cho in the phase-separated ternary membranes.

As shown in Fig. 10, the potent LacCer-LacCer interaction induces a thermally stable gel phase and requires equimolar Cho to form a homogeneous Lo phase in LacCer/Cho binary membranes. The Cho effect to LacCer to form the Lo phase is much lower than that to sphingomyelin. This is because the affinity between LacCer and Cho is significantly lower than that between sphingomyelin and Cho (see DSC in Fig. 2) due to the difference in headgroup structure (54). In the ternary bilayers containing POPC and Cho, the dynamics of LacCer is significantly different from that of sphingomyelin; neither the LacCer Lo domain (with a higher order of acyl chains) as seen for sphingomyelin nor the macroscopic gel domain was observed. Cho surrounds the LacCer gel domains and disturbs the large and heterogeneous H-bonding network, which reduces the cooperativity of the LacCer gel domains and assists in the formation of small and ordered LacCer domains in the POPC bilayers. Such small and ordered domains were also reported in sphingomyelin/POPC/Cho membranes (55). Since the large Lo domains of LacCer-Cho with long lifetimes were not detected in the microscopy and lifetime experiments on the ternary membranes containing 20 mol% Cho (Figs. 4 and 8), the potent homophilic LacCer interaction tends to block entry of Cho into the domains. These small lipid domains, the so-called lipid nano-subdomains, have already been suggested for GlcCer and other glycosphingolipid bilayers (56) but have not been reported for LacCer bilayers so far. In contrast, LacCer was well mixed with DMPC bearing two saturated lipid chains (Fig. S3). Therefore, LacCer in the cell membranes is potentially involved in the domain of saturated phospholipids such as sphingomyelin. Actually, Maunula et al. reported that LacCer was involved in the SM domains of the POPC/LacCer/SM/Cho bilayer and significantly increased the thermal stability of the SM domains (22). Therefore, LacCer not only form the gel-like domains but also distributes in the ordered SM domains in biological membranes and increases the lipid chain packing. This is similar to the effect of long-chain alkylresorcinols for saturated phospholipid membranes (57).

Figure 10.

Models of the LacCer-lipid interaction and domain formations. (A) The addition of Cho destabilizes the LacCer gel phase and induces the Lo phase at ≥40°C in the binary membrane. The potent ordering effect of Cho on the LacCer acyl chain was clearly observed. (B) The LacCer gel phase is highly stable and not miscible well with POPC in bilayers even at 40°C. (C) In the LacCer/POPC/Cho ternary membranes, Cho reduces the cooperativity of the LacCer gel phase and facilitates the formation of small and ordered LacCer domains, which are distributed to the POPC-rich Ld area.

LacCer in the plasma membrane of neutrophils and dendritic cells is assumed to form LacCer-rich domains, which plays a role in immune signaling, probably by interacting with the glycans derived from pathogenic bacteria and fungi (58). In the presence of high concentrations of Cho, such as in biological membranes, the size of the ordered domain of LacCer is likely to be smaller than the observable size under the microscope. LacCer, even at lower concentrations, can form more stable gel-phase domains than sphingomyelin, and such membrane properties are thought to be responsible for the biological functions. As shown in Fig. 10, LacCer was preferable for the formation of the gel-like domains or small ordered domains in the presence of Cho due to the potent LacCer homophilic interaction. This is consistent with the previous report (59) that found the LacCer-rich domains in the cell membrane contain less Cho and have a firm gel-like property in comparison with sphingomyelin-rich domains. However, how such firm LacCer-rich domains could induce interleaflet signaling that leads to kinase activation on the cytoplasmic leaflets remains unclear. In previous microscopic observations, the size of the LacCer-rich domain was estimated at <1 μm (60,61). Cho in the model bilayer membranes reduces the size of large LacCer gel-like domains and facilitates the distribution of the small LacCer domains over the cell membranes, which also leads to the formation of functional domains in the cell membranes.

Conclusion

We investigated the domain formation of LacCer, a glycosphingolipid with a high melting temperature, in bilayer model membranes composed of LacCer/POPC/Cho under phase-separated conditions. The solid-state 2H NMR with 10′,10′-d2-LacCer, having deuterium at the middle of the acyl chain, revealed that LacCer forms the Lo phase in LacCer/Cho 50:50 membranes. The 2H NMR with 18′,18′,18′-d3-LacCer, having deuterium at the acyl-chain terminal, and the tPA fluorescence lifetime in LacCer/POPC binary membrane revealed that LacCer is largely aggregated to form the rigid gel phase through the potent homophilic interaction and is not distributed in the Ld phase. The 2H NMR of Cho-containing ternary membranes (LacCer/POPC/Cho 26:65:9, 22:65:12, and 15:65:20) showed that the size of LacCer gel domain decreases, whereas the Lo domain was not formed in these lipid compositions. On the other hand, Cho significantly reduces the cooperativity of the LacCer gel domains and facilitates the distribution of small and ordered LacCer domains with submicron to nanometer sizes in the Ld domains. These LacCer domains in the model membranes are assumed to be related to the LacCer domains in immune cell membranes. To elucidate the biological function of these LacCer domains, further studies using quaternary or more complex lipid systems are necessary. Nevertheless, present findings on the domain structure and properties of LacCer in Cho-containing bilayers provide clues to elucidate the properties of LacCer domains in biological membranes.

Author contributions

S.H. and M.M. designed the research. S.H., R.I., Y.M., and H.T. performed the synthesis of the deuterated analogs. S.H., R.I., and Y.M. performed solid-state NMR spectroscopy and microscopy. R.I. and T.Y. collected DSC thermograms. R.I. performed and P.S. guided the fluorescent lifetime experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. K. Iwabuchi, Juntendo University, for the discussions and suggestions. We are also grateful to Drs. Inazumi and Todokoro, Osaka University, for their technical assistance in solid-state NMR spectroscopy. This work was supported in part by the International Joint Research Promotion Program of Osaka University, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research JP19K05713 (S.H.), JP16H06315 (M.M.), and JP19K22257 (M.M.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Japan, and JST, CREST Grant Number JPMJCR18H2 (S.H.).

Editor: Timothy A. Cross.

Footnotes

Hiroshi Tsuchikawa present address is Faculty of Medicine, Oita University, Oita, Japan

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2022.02.037.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Simons K., Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westerlund B., Slotte J.P. How the molecular features of glycosphingolipids affect domain formation in fluid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooper N.M. Detergent-insoluble glycosphingolipid/cholesterol-rich membrane domains, lipid rafts and caveolae. Mol. Membr. Biol. 1999;16:145–156. doi: 10.1080/096876899294607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hakomori S. The glycosynapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:225–232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012540899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamanaka S., Asagami C., et al. Fujita H. The glycolipids of normal human skin. J. Dermatol. 1983;10:545–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1983.tb01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kniep B., Skubitz K.M. Subcellular localization of glycosphingolipids in human neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1998;63:83–88. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman J.W., Lindermuth J., et al. DeMong D.E. A novel carbohydrate-glycosphingolipid interaction between a β-(1-3)-glucan immunomodulator, pgg-glucan, and lactosylceramide of human leukocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22014–22020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.22014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato T., Iwabuchi K., et al. Ogawa H. Induction of human neutrophil chemotaxis by candida albicans-derived β-1,6-long glycoside side-chain-branched β-glucan. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;80:204–211. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0106069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakayama H., Kurihara H., et al. Iwabuchi K. Lipoarabinomannan binding to lactosylceramide in lipid rafts is essential for the phagocytosis of mycobacteria by human neutrophils. Sci. Signal. 2016;9:ra101. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwabuchi K., Prinetti A., et al. Nagaoka I. Involvement of very long fatty acid-containing lactosylceramide in lactosylceramide-mediated superoxide generation and migration in neutrophils. Glycoconj. J. 2008;25:357–374. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9084-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiricozzi E., Ciampa M.G., et al. Mauri L. Direct interaction, instrumental for signaling processes, between laccer and Lyn in the lipid rafts of neutrophil-like cells. J. Lipid Res. 2015;56:129–141. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M055319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwabuchi K., Nagaoka I. Lactosylceramide-enriched glycosphingolipid signaling domain mediates superoxide generation from human neutrophils. Blood. 2002;100:1454–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S.Y., Wang T.K., et al. Pagano R.E. Proteomic identification of proteins translocated to membrane microdomains upon treatment of fibroblasts with the glycosphingolipid, C8-β-D-lactosylceramide. Proteomics. 2009;9:4321–4328. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma D.K., Brown J.C., et al. Pagano R.E. The glycosphingolipid, lactosylceramide, regulates beta1-integrin clustering and endocytosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8233–8241. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh R.D., Holicky E.L., et al. Pagano R.E. Inhibition of caveolar uptake, SV40 infection, and β1-integrin signaling by a nonnatural glycosphingolipid stereoisomer. J. Cell Biol. 2007;176:895–901. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saxena K., Zimmermann P., et al. Shipley G.G. Bilayer properties of totally synthetic C16:0-lactosyl-ceramide. Biophys. J. 2000;78:306–312. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X.M., Momsen M.M., et al. Brown R.E. Lactosylceramide: effect of acyl chain structure on phase behavior and molecular packing. Biophys. J. 2002;83:1535–1546. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73923-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murate M., Hayakawa T., et al. Kobayashi T. Phosphatidylglucoside forms specific lipid domains on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4732–4739. doi: 10.1021/bi100007u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koynova R., Caffrey M. Phases and phase transitions of the sphingolipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1255:213–236. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)00202-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slotte J.P., Ostman A.L., et al. Bittman R. Cholesterol interacts with lactosyl and maltosyl cerebrosides but not with glucosyl or galactosyl cerebrosides in mixed monolayers. Biochemistry. 1993;32:7886–7892. doi: 10.1021/bi00082a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhai X., Li X.M., et al. Brown R.E. Lactosylceramide: lateral interactions with cholesterol. Biophys. J. 2006;91:2490–2500. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maunula S., Bjorkqvist Y.J., et al. Ramstedt B. Differences in the domain forming properties of N-palmitoylated neutral glycosphingolipids in bilayer membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:336–345. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenske D.B., Hamilton K., et al. Grant C.W. Glycosphingolipids: 2H NMR study of the influence of carbohydrate headgroup structure on ceramide acyl chain behavior in glycolipid-phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4503–4509. doi: 10.1021/bi00232a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu Z.W., Calvert T.L., Leckband D. Molecular forces between membranes displaying neutral glycosphingolipids: evidence for carbohydrate attraction. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1540–1550. doi: 10.1021/bi971010o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Latza V.M., Deme B., Schneck E. Membrane adhesion via glycolipids occurs for abundant saccharide chemistries. Biophys. J. 2020;118:1602–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneck E., Deme B., et al. Tanaka M. Membrane adhesion via homophilic saccharide-saccharide interactions investigated by neutron scattering. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2151–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuklev D.V., Smith W.L. Synthesis of four isomers of parinaric acid. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2004;131:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yano Y., Hanashima S., et al. Murata M. Sphingomyelin stereoisomers reveal that homophilic interactions cause nanodomain formation. Biophys. J. 2018;115:1530–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis J.H., Jeffrey K.R., et al. Higgs T.P. Quadrupolar echo deuteron magnetic-resonance spectroscopy in ordered hydrocarbon chains. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1976;42:390–394. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seelig J. Deuterium magnetic resonance: theory and application to lipid membranes. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1977;10:353–418. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500002948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schorn K., Marsh D. Dynamic chain conformations in dimyristoyl glycerol-dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine mixtures. 2H-NMR Studies. Biophys. J. 1996;71:3320–3329. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79524-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinoshita M., Suzuki K.G.N., et al. Murata M. Raft-based sphingomyelin interactions revealed by new fluorescent sphingomyelin analogs. J. Cell Biol. 2017;216:1183–1204. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201607086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson I.D., Kang H.C., Haugland R.P. Fluorescent membrane probes incorporating dipyrrometheneboron difluoride fluorophores. Anal. Biochem. 1991;198:228–237. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90418-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halling K.K., Ramstedt B., et al. Nyholm T.K.M. Cholesterol interactions with fluid-phase phospholipids: effect on the lateral organization of the bilayer. Biophys. J. 2008;95:3861–3871. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yasuda T., Matsumori N., et al. Murata M. Formation of gel-like nanodomains in cholesterol-containing sphingomyelin or phosphatidylcholine binary membrane as examined by fluorescence lifetimes and 2H NMR spectra. Langmuir. 2015;31:13783–13792. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsumori N., Yasuda T., et al. Murata M. Comprehensive molecular motion capture for sphingomyelin by site-specific deuterium labeling. Biochemistry. 2012;51:8363–8370. doi: 10.1021/bi3009399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yasuda T., Tsuchikawa H., et al. Matsumori N. Deuterium NMR of raft model membranes reveals domain-specific order profiles and compositional distribution. Biophys. J. 2015;108:2502–2506. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yasuda T., Kinoshita M., et al. Matsumori N. Detailed comparison of deuterium quadrupole profiles between sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biophys. J. 2014;106:631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varela A.R.P., Couto A.S., et al. Silva L.C. Glucosylceramide reorganizes cholesterol-containing domains in a fluid phospholipid membrane. Biophys. J. 2016;110:612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blanchette C.D., Lin W.C., et al. Longo M.L. Galactosylceramide domain microstructure: impact of cholesterol and nucleation/growth conditions. Biophys. J. 2006;90:4466–4478. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.072744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheidt H.A., Huster D. Structure and dynamics of the Myristoyl lipid modification of Src peptide deutertated by 2H solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3663–3672. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinnun J.J., Leftin A., Brown M.F. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy for the physical chemistry laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 2013;90:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sklar L.A., Hudson B.S., Simoni R.D. Conjugated polyene fatty-acids as fluorescent-probes - synthetic phospholipid membrane studies. Biochemistry. 1977;16:819–828. doi: 10.1021/bi00624a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engberg O., Nurmi H., et al. Slotte J.P. Effects of cholesterol and saturated sphingolipids on acyl chain order in 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine bilayers--a comparative study with phase-selective fluorophores. Langmuir. 2015;31:4255–4263. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engberg O., Scheidt H.A., et al. Huster D. Membrane localization and lipid interactions of common lipid-conjugated fluorescence probes. Langmuir. 2019;35:11902–11911. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b01202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bjoerkqvist Y.J.E., Nybond S., et al. Ramstedt B. N-palmitoyl-sulfatide participates in lateral domain formation in complex lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2008;1778:954–962. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Molugu T.R., Lee S., Brown M.F. Concepts and methods of solid-state NMR spectroscopy applied to biomembranes. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:12087–12132. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bryant G., Taylor M.B., et al. Garvey C.J. Effect of deuteration on the phase behaviour and structure of lamellar phases of phosphatidylcholines - deuterated lipids as proxies for the physical properties of native bilayers. Colloids Surf. B. 2019;177:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hashizume M., Sato T., Okahata Y. Selective bindings of a lectin for phase-separated glycolipid monolayers. Chem. Lett. 1998;27:399–400. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yasuda T., Slotte J.P., Murata M. Nanosized phase segregation of sphingomyelin and dihydrosphigomyelin in unsaturated phosphatidylcholine binary membranes without cholesterol. Langmuir. 2018;34:13426–13437. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b02637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Favela-Rosales F., Galván-Hernández A., et al. Ortega-Blake I. A molecular dynamics study proposing the existence of statistical structural heterogeneity due to chain orientation in the POPC-cholesterol bilayer. Biophys. Chem. 2020;257:106275. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2019.106275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bozelli J.C., Aulakh S.S., Epand R.M. Membrane shape as determinant of protein properties. Biophys. Chem. 2021;273:106587. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2021.106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inaba T., Murate M., et al. Kobayashi T. Formation of tubules and helical ribbons by ceramide phosphoethanolamine-containing membranes. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:5812. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42247-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang J., Feigenson G.W. A microscopic interaction model of maximum solubility of cholesterol in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 1999;76:2142–2157. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77369-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Almeida R.F.M., Loura L.M.S., et al. Prieto M. Lipid rafts have different sizes depending on membrane composition: a time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer study. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:1109–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cebecauer M., Amaro M., et al. Hof M. Membrane lipid nanodomains. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:11259–11297. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zawilska P., Cieślik-Boczula K. Laurdan emission study of the cholesterol-like effect of long-chain alkylresorcinols on the structure of dipalmitoylphosphocholine and sphingomyelin membranes. Biophys. Chem. 2018;221:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nakayama H., Nagafuku M., et al. Inokuchi J.I. The regulatory roles of glycosphingolipid-enriched lipid rafts in immune systems. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:3921–3942. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iwabuchi K., Handa K., Hakomori S. Separation of "glycosphingolipid signaling domain" from caveolin-containing membrane fraction in mouse melanoma B16 cells and its role in cell adhesion coupled with signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33766–33773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Iwabuchi K., Masuda H., et al. Takamori K. Properties and functions of lactosylceramide from mouse neutrophils. Glycobiology. 2015;25:655–668. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwv008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Singh R.D., Liu Y.D., et al. Pagano R.E. Caveolar endocytosis and microdomain association of a glycosphingolipid analog is dependent on its sphingosine stereochemistry. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:30660–30668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.