Abstract

People living with Parkinson Disease (PwP) have been at risk for the negative effects of loneliness even before the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic. Despite some similarities with previous outbreaks, the Covid-19 pandemic is significantly more wide-spread, long-lasting, and deadly, which likely means demonstrably more negative mental health issues. Although PwP are not any more likely to contract Covid-19 than those without, the indirect negative sequelae of isolation, loneliness, mental health issues, and worsening motor and non-motor features remains to be fully realized. Loneliness is not an isolated problem; the preliminary evidence indicates that loneliness associated with the Covid-19 restrictions has dramatically increased in nearly all countries around the world.

Key words: Covid-19, Social isolation, Loneliness, Mental health, Parkinson disease

1. Introduction

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19), caused by the novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), a global pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020), which has since wreaked havoc on health of people around the world and has resulted in an undeniable health crisis. Not only is the risk of contracting the virus concerning, but the consequences resulting from the mitigation efforts are alarming and poorly understood. The international literature concludes that among the potential mental health consequence imposed by social distancing, loneliness may be the most problematic (Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor, & Dailey, 2020; Luchetti et al., 2020). Loneliness is undoubtedly a concern for the general population, but for people with chronic illnesses, including Parkinson's disease (PD), it can compound health problems and be particularly detrimental. A growing body of research reports on the myriad complications associated with loneliness among people with PD (e.g., depression, fatigue, anxiety, apathy) (Antonini, Leta, Teo, & Chaudhuri, 2020; Brooks, Weston, & Greenberg, 2021; Prasad et al., 2020). Screening patients for loneliness and identifying appropriate interventions to mitigate its effects is critical as the pandemic persists. Importantly, loneliness is not confined to the Western World; it is rather recognized as a burgeoning health epidemic affecting the communities around the globe (Holt-Lunstad, 2017) and is considered among the greatest health challenges of this generation (World Health Organization, 2015).

2. Loneliness

People living with Parkinson Disease (PwP) have been at risk for the negative effects of loneliness even before the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite some similarities with previous outbreaks, the Covid-19 pandemic is significantly more wide-spread, long-lasting, and deadly, which likely means demonstrably more negative mental health issues (Mesa Vieira, Franco, Gómez Restrepo, & Abel, 2020). Although PwP are not any more likely to contract SARS-CoV-2 that those without PD, the indirect negative sequelae of isolation and loneliness, including mental health issues and worsening motor and non-motor features, remain to be fully realized (Prasad et al., 2020; Stoessl, Bhatia, & Merello, 2020). Loneliness is not an isolated problem; the preliminary evidence indicates that loneliness associated with the Covid-19 restrictions has dramatically increased in nearly all countries around the world (Folk, Okabe-Miyamoto, Dunn, & Lyubomirsky, 2020; Krendl & Perry, 2021; Macdonald & Hülür, 2021; McGinty, Presskreischer, Han, & Barry, 2020).

Although the risks associated with contracting SARS-CoV-2 have been well-documented, literature continues to evolve, describing the considerable psychosocial sequelae affecting both well-being and quality of life resulting from the unprecedented, strict social distancing measures (Antonini, 2020). International pandemics can evoke significant emotional disturbances, even among individuals who are seemingly at low risk (Brooks et al., 2020). As a result of the world-wide stay-at-home and social distancing mandates, social isolation and loneliness rose precipitously and the long-term effects remain unknown. Covid-19 is not the first time that quarantining (e.g., social distancing, isolation) has been employed to reduce the spread of an infectious disease—it was used successfully to contain severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the first pandemic of the 20th century. As a result of the mitigation efforts, individuals who experienced social isolation during SARS reported significant increases in both posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression with longer time in isolation resulting in increased symptomatology (Hawryluck et al., 2004; Reynolds et al., 2008). Additionally, likely due to the effective coping strategies, increased alcohol abuse/dependence has been reported for up to three years after being exposed to the isolation associated with the SARS mitigation efforts (Wu et al., 2008). Similarly, following the rapid spread of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and subsequent short periods of isolation (e.g., 6 months), people reported increased mental health issues (Jeong et al., 2016). The common denominator between the last three major viral pandemics is the use of social distancing measures, which resulted in isolation, loneliness, and increased mental health problems.

All people have a fundamental need for social connection and meaningful interpersonal relationships without which human flourishing is unlikely to be attained (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Cacioppo, Capitanio, & Cacioppo, 2014). The instinctive drive for social connectedness is evident throughout the lifespan—“from cradle to grave” (Bowlby, 1979, p. 179). Moreover, social relationships are essential to promote positive health and functioning. Social isolation and loneliness are frequently used interchangeably; however, they are distinct concepts. Social isolation can be described as the objective feeling of the inadequacy of social connections, resulting in a decreased frequency of social contact (Coyle & Dugan, 2012). Social isolation is particularly problematic for the aging population due to diminishing financial resources, declining physical health, and death of friends and loved ones (Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos, & Wardle, 2013). Loneliness, however, is a subjective emotional state associated with the lack of social connectedness (Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017). Therefore, one can be socially isolated without feeling lonely and can feel lonely despite being socially well-connected.

Although loneliness is largely discussed as a singular construct, researchers have delineated three dimensions or spheres of loneliness that identify the missing relationship. Intimate or emotional loneliness is the craving for a close, intimate relationship or emotional partner. Relational or social loneliness includes the absence of close friendships and a longing for social companionship. Collective loneliness refers to the lack of a structured network of people who all share a common interest and purpose—a community (Michela, Peplau, & Weeks, 1982; Murthy, 2020). Hence, a person can still be lonely if they lack a circle of friends or a community with a shared purpose outside their home even if they are happily married (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Social isolation vs. loneliness.

| Social isolation | Loneliness |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Three types: | |

|

|

|

|

|

Social isolation can undoubtedly exacerbate loneliness, but one's perception of loneliness is more closely associated with the quality of social interactions rather than the quantity (Hawkley et al., 2008). This may be due to the fact that loneliness is influenced by a number of factors, which are largely unrelated to one's objective view, including heritability (Boomsma, Willemsen, Dolan, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2005), environmental factors (Bartels, Cacioppo, Hudziak, & Boomsma, 2008), cultural norms (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008), individual social needs (Dykstra & Fokkema, 2007), presence of a chronic illness or disability (Hawkley et al., 2008; Mushtaq, 2014), poor coping strategies (Deckx, van den Akker, Buntinx, & van Driel, 2018), lower socioeconomic status (Wee et al., 2019), being female (Solmi et al., 2020), and the disparity between experienced versus desired relationships (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). More likely as a result of stigma and systemic societal issues, racial, ethnic, and LGBTQ + minorities are more prone to loneliness (Jeste, Lee, & Cacioppo, 2020). Loneliness is clearly a multidimensional construct, but, based on our evolutional heritage and available literature, the brain has been fashioned to seek meaningful connections with others.

3. Physiology of loneliness

Because early humans had a greater chance of survival if they existed in groups, evolutionary adaptation favored the preference for close human bonds by selecting genes that result in pleasure in company and feelings of unease when involuntarily alone (Solmi et al., 2020). Not only does social connectedness portend positive outcomes, but being deprived of them may lead to profound insecurity and loneliness. Most of the research on loneliness has been focused on surveys and animal studies to evaluate the effect of social deprivation on neuroendocrine activity. Research demonstrates an association between loneliness and stress-related inflammatory and neuroendocrine responses in adults (Steptoe et al., 2013). Loneliness can also affect cognitive processing and result in hypervigilance, which may lead to anxiety (Cacioppo et al., 2014). Additionally, loneliness is associated with increased hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity. For instance, loneliness is linked with greater cortisol awakening response in middle-aged adults (Steptoe et al., 2013), and previous day loneliness results in heightened cortisol awakening response in older adults (Adam, Hawkley, Kudielka, & Cacioppo, 2006). In PwP, cortisol-related pathological responses to stress has been shown to negatively affects both motor and non-motor symptoms of PD potentially even noticeable in the prodromal stage (van Wamelen, Wan, Chaudhuri, & Jenner, 2020).

A robust body of literature exists explicating the role of social support in buffering stress (Ditzen & Heinrichs, 2014; Holt-Lunstad, 2018; Nitschke et al., 2021; Sandi & Haller, 2015). During times of limited social support and isolation, people are increasingly susceptible to the damaging effects of stress. Loneliness, in addition to an inadequate social support system, is a predictor of a poor immune response to stress; however, the weakest immune response occurs in people who report being both lonely and lacking a reasonable social network (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006; Lim, Eres, & Vasan, 2020). Despite these reports, the impact of loneliness on people and society at large remains underrecognized and poorly understood.

4. Loneliness and the brain

Clinical evidence supports the notion that the human brain is wired to desire social connection and to have meaningful interactions with others. Specifically, neuroimaging studies report that the brain responds to the social pain of loneliness similar to how it responds to physical pain (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). Research has begun to attempt to understand the role of loneliness on brain health and preliminary evidence has identified connected regions of the brain midline and medial temporal lobes, including the hippocampus, which are hypothesized to provide a potential neural substrate, linking loneliness, aging, and brain health (Mwilambwe-Tshilobo et al., 2019; Spreng et al., 2020). Moreover, loneliness has been associated with higher amyloid burden - a neuropathological feature of Alzheimer's disease (Donovan et al., 2016). Loneliness not only results in a variety of psychosocial issues, but it may also be associated with pathophysiological changes in the brain.

5. General health effects of loneliness

Loneliness can result in significant negative health outcomes, including increased risk of depression, anxiety, cognitive decline, type 2 diabetes, poor sleep, arthritis (Dossey, 2020; Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, 2015), and even cancer (Nausheen, Gidron, Peveler, & Moss-Morris, 2009) and suicide (Brooks et al., 2020). Concerns have been raised about the association between loneliness and potentially problematic alcohol consumption, as alcohol sales rose by 54% during the initial shelter-in-place orders (Grossman, Benjamin-Neelon, & Sonnenschein, 2020). Loneliness is associated with a 29% increase in the incidence of coronary heart disease and a 32% increase in the risk of stroke (Valtorta, Kanaan, Gilbody, Ronzi, & Hanratty, 2016). Accordingly, a recent meta-analysis revealed that lonely people have an estimated 26% increased risk of all-cause mortality compared to non-lonely individuals (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). An estimated 162,000 Americans die annually as a result of social isolation (Veazie, Gilbert, Winchell, Paynter, & Guise, 2019) and loneliness has been reported to be more detrimental to health than obesity, smoking, lack of exercise, and excessive alcohol consumption combined (Lynch, 2000).

6. Loneliness and mental and cognitive health

Not only is there a variety of negative physical sequelae of loneliness, but mental and cognitive health are also significantly affected, possibly in a more damaging way. Research has implicated loneliness in depressive symptomology (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010). In addition to depression, loneliness is also associated with increased social anxiety and paranoia (Lim, Rodebaugh, Zyphur, & Gleeson, 2016). Emotional regulation is a strategy to manage or cope with emotions and has been shown to be negatively affected by loneliness, which results in less expression and enjoyment of positive feelings (Hawkley, Thisted, & Cacioppo, 2009). Furthermore, loneliness is associated with greater cognitive impairment among community dwelling adults and, even after controlling for confounders (e.g., sociodemographic, health conditions, depression), loneliness is implicated in accelerated cognitive decline later in life (Donovan et al., 2017; Poey, Burr, & Roberts, 2017). People who reported higher loneliness were 64% more likely to develop dementia than those who were not lonely (Holwerda et al., 2012) and were twice as likely to develop Alzheimer's disease, even after controlling for social isolation, social support, and living alone (Zhou, Wang, & Fang, 2018).

7. Loneliness and the aging population

The body of literature assessing the myriad health impacts of loneliness is large and unequivocal. While loneliness is associated with a variety of negative outcomes for nearly everyone, for older adults loneliness may be particularly injurious (Beam & Kim, 2020; Czaja, Moxley, & Rogers, 2021; Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2013; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001). In particular, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that older adults suffering from loneliness are at higher risk for dementia, depression, and anxiety (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). Loneliness is reported to have a prevalence of 30–40% in older individuals (Courtin & Knapp, 2017). As people age, they experience an increase in sensory impairments (e.g., hearing, visual), which can preclude them from fully participating in social activities and interactions, putting them at a greater risk for loneliness (Eggar, Spencer, Anderson, & Hiller, 2002). This is of particular relevance for PwP, as the vast majority of them are diagnosed at age 60 or older.

8. Loneliness and chronic illness

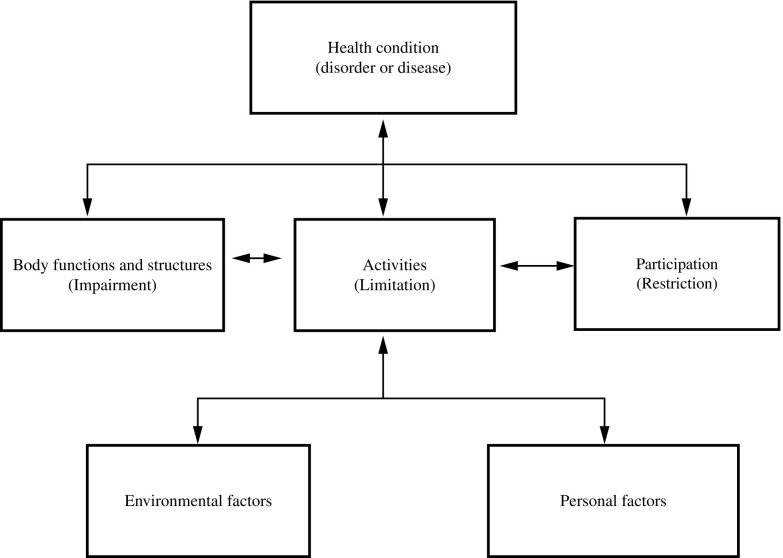

The negative effects of loneliness on health are well-established for the general population, but loneliness may be detrimental for people with serious health conditions (Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil, & Covinsky, 2019). Research asserts that loneliness is the single most significant predictor of psychological distress among people with chronic illness and disability (CID). Additionally, not only was loneliness associated with one's own CID, spousal CID was also correlated with higher levels of loneliness and subsequent poor health outcomes (Ditzen & Heinrichs, 2014; Holt-Lunstad, 2018; Nitschke et al., 2021; Sandi & Haller, 2015). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF; World Health Organization [WHO], 2001) was established in an attempt to provide a comprehensive framework for holistically conceptualizing health and has been used to describe the effects of neurologic conditions on health outcomes (McDaniels & Bishop, 2021; McDaniels, Bishop, & Rumrill Jr., 2021). The ICF model centers on the interaction between psychological, biological, and social components and how they, collectively, affect functioning (Peterson, 2016) (Fig. 1 ). For example, when individuals have limited interaction with others and are lonely (environmental factors), decreased community participation may occur leading to increased anxiety and depression (health condition). For people with CID, their health condition alone (e.g., PD) may result in impairment on body functions and structures (e.g., gait impairment, tremor, cognitive issues), precluding full community participation; however, when problems like loneliness arise in additional areas of one's life, consequences compound and may lead to additional health consequences and diagnoses.

Fig. 1.

Interactions between the components of the ICF model.

Adapted from World Health Organization. (2001). The international classification of functioning, disability, and health. World Health Organization.

The data for the negative effects of loneliness on the general population is clear (Xiong et al., 2020), but how the lockdown measures have affected those with neurologic conditions is still developing. Emerging data, however, suggests that individuals with an accompanying chronic disease are more susceptible to the psychological effects of the Covid-19 social distancing mandates, which may implicate loneliness as one of the predictors of poorer psychological health outcomes (Özdin & Bayrak Özdin, 2020). Among people with multiple sclerosis (PwMS), data reports increased levels of depression and anxiety from pre-pandemic to intra-pandemic, with loneliness being considered one of the precipitating factors (Alschuler, Roberts, Herring, & Ehde, 2021; Naser Moghadasi, 2020; Shaygannejad, Afshari-Safavi, & Hatef, 2021; Stojanov et al., 2020). Specifically, 73.3% of PwMS with increased anxiety and depression during the Covid-19 outbreak reported increased loneliness (Garjani et al., 2021). Similar findings have been published for people with epilepsy (Tashakori-Miyanroudi et al., 2021), visual impairments (Heinze et al., 2021), rheumatic diseases (Kool & Geenen, 2012), and generally for all people with CID (Elran-Barak & Mozeikov, 2020; Horesh, Kapel Lev-Ari, & Hasson-Ohayon, 2020; Wong et al., 2020).

9. Loneliness and Parkinson's disease

The fact that PwP are largely in an older demographic group, where loneliness is more common, means that this population may be particularly at risk for the effects of loneliness. In general, feeling socially isolated and lonely is not uncommon for PwP, as there can be stigma associated with the diagnosis of PD, which may cause patients to socially withdraw (Maffoni, Giardini, Pierobon, Ferrazzoli, & Frazzitta, 2017; Subramanian et al., 2021). Other reasons for social withdrawal can include difficulty communicating due to hypophonia, dysarthria, and facial masking (Subramanian, Farahnik, & Mischley, 2020). The presence of tremor and/or dyskinesia can also result in feelings of embarrassment, making one more reticent to engage socially (Soleimani, Negarandeh, Bastani, & Greysen, 2014). Drooling, difficulty handling utensils, unpredictable bowel and bladder issues (e.g., incontinence), the use of a cane or walker, poor balance, freezing of gate, and risk of falling are all predictors of loneliness among PwP (Sjödahl Hammarlund, Westergren, Åström, Edberg, & Hagell, 2018).

Mental health issues, such as apathy, depression and anxiety, can contribute to lack of motivation to seek social connection and a diminished desire to actively engage when found in such situations (Perepezko et al., 2019). Accumulating evidence supports the relationship between depression and social isolation among PwP (Helmich & Bloem, 2020; Janiri et al., 2020; Kitani-Morii et al., 2021; Subramanian et al., 2020). Not surprisingly, the added social consequences of the mitigation efforts associated with the pandemic have further compounded the effects of loneliness on the overall well-being and quality of life of PwP (Antonini, 2020; Subramanian et al., 2020). Subramanian et al. (2020) also reported that among PwP, those who are lonely mention greater severity of the symptoms of bradykinesia, pain, memory, depression, anxiety, and fatigue among others.

10. Non-motor aspects of Parkinson's disease

Despite the historical focus on the motor features of PD, a variety of non-motor features are commonly encountered and are a leading cause of poor quality of life for PwP (Chaudhuri et al., 2015; Kalia & Lang, 2015). Non-motor symptoms affect nearly all (> 90%) PwP and are often considered to be more burdensome than motor symptoms (Antonini et al., 2012; Martinez-Martin et al., 2011). Among the most problematic non-motor features are cognitive impairment, depression, sleep disorders, anxiety, and apathy (Weintraub & Mamikonyan, 2019). Although prevalence reports vary, dementia affects about 50% of PwP (Williams-Gray et al., 2013), while mild cognitive impairment (MCI) may be present in 25–50% (Aarsland et al., 2010). Cognitive decline is common, typically slow and insidious, and may occur across all stages of PD, increasing the risk of early dementia (Aarsland et al., 2021). Among mood disorders, depression, anxiety, and apathy are the most widely reported and occur in 35% (Schapira, Chaudhuri, & Jenner, 2017), 31% (Broen, Narayen, Kuijf, Dissanayaka, & Leentjens, 2016), and 60% of PwP (Schapira et al., 2017), respectively. Fatigue is another commonly reported non-motor feature of PD and reports indicate prevalence rates of around 50% (Siciliano et al., 2018). Sleep disorders are emerging among the most common and heterogeneous non-motor manifestations of PD, occurring in up to 90% of PwP (Chaudhuri et al., 2010). These disorders present significant challenges; however, when coupled with the effects of the mitigation efforts associated with a global pandemic and the resultant loneliness, their negative influence on quality of life is likely compounded.

11. Covid-19 and Parkinson's disease

Data on the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on PwP is increasing, but appears to clearly portend a worsening of nearly all PD-related symptoms. Among the most common potentiators of neuropsychiatric symptoms manifestation during a pandemic are fear of contracting the virus (Jeong et al., 2016) and isolation or lack of social connections (Hawryluck et al., 2004), all of which have been experienced by PwP throughout the past two years. Considering the unusual external conditions that contribute to increased anxiety, depression, and stress, along with the daily stress of living with and managing a chronic neurologic condition, identifying specific contributing factors and potential interventions is critical (McDaniels, Novak, Braitsch, & Chitnis, 2021; Subramanian et al., 2021).

Fear of health emergencies can contribute to severe emotional distress and anxiety among low risk populations, but for PwP the ramifications become more problematic (Schapira et al., 2017). Stress and anxiety are consistently among the most frequently reported non-motor features of PD; however, considering the challenges associated with the pandemic, there was a significant rise in these mental health issues. PwP are acutely sensitive to increased stress and reduction in physical activity, which can increase both motor and non-motor features of PD (Helmich & Bloem, 2020). One proposed mechanism is that mood symptoms (e.g., apathy, depression, anxiety) are believed to be associated with dysfunction of the dopaminergic, serotonergic, and noradrenergic system along with the changes in serum levels of dopaminergic medications (Bomasang-Layno, Fadlon, Murray, & Himelhoch, 2015; Cooney & Stacy, 2016; Espay, LeWitt, & Kaufmann, 2014).

Exercise and physical therapy are considered among the most highly encouraged and beneficial interventions for PD management, as they have been associated with improved mood and cognition (Douma & de Kloet, 2020) and may even improve all-cause mortality (Yoon, Suh, Yang, Han, & Kim, 2021). Periods of inactivity are positively correlated with worsening of both motor and non-motor features of PD (e.g., psychological stress, insomnia, depression; Helmich & Bloem, 2020). PwP were unable to engage with their medical providers via in-person appointments to discuss problematic progression of motor and non-motor symptoms, the evolution of new issues, or receive essential programming adjustments for deep brain stimulation (DBS) devices. Additionally, PwP experienced a dramatic reduction in their ability to remain active in community support groups and to interact with others in the community.

Loneliness and the lack of social connection stemming from Covid-19 clearly increases the likelihood of developing or exacerbating neuropsychiatric symptoms (Antonini et al., 2020; Prasad et al., 2020). A better understanding of the neurobiological sequalae of increased stress and the compounding effects of loneliness and isolation is critical not only for PwP, but for all individuals with CID. The pandemic has undoubtedly wreaked havoc on the lives of all populations worldwide, resulting in increased levels of stress, but those with PD and other CID are particularly at risk, as they rely on a variety of in-person support mechanisms to facilitate physical functioning and general well-being. Remaining both physically and socially engaged is imperative for the preservation of health, functioning, and quality of life among older individuals and PwP (Brady et al., 2020; Hajek et al., 2017). Thus, identifying novel means of remaining engaged with exercise and to socially connect is essential to stave off the negative effects of loneliness. The mental health issues associated with social isolation and loneliness are far-reaching, significant, and consistent around the globe (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Global Non-Motor Effects of Isolation in PwP.

| Study (authors, year) | Country | Sample size | Mental health outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anghelescu, Bruno, Martino, and Roach (2021) | Canada | 22 | Anxiety, irritability, sleep |

| Balci, Aktar, Buran, Tas, and Donmez Colakoglu (2021) | Turkey | 45 | Anxiety, cognition, depression, sleep |

| Baschi et al. (2020) | Italy | 65 | Anxiety, apathy, cognition, depression, fatigue |

| Brown et al. (2020) | USA (80%) | 5429 | Anxiety, apathy, cognition, depression, fatigue, sleep |

| Del Prete et al. (2021) | Italy | 740 | Anxiety, mood, sleep |

| de Rus Jacquet et al. (2021) | Canada | 417 | Anxiety, cognition, depression |

| Feeney et al. (2021) | USA | 1342 | Anxiety, cognition |

| Guo et al. (2020) | China | 113 | Depression, fatigue, sleep |

| Janiri et al. (2020) | Italy | 134 | Apathy, cognition, irritability, sleep |

| Kapel, Serdoner, Fabiani, and Velnar (2021) | Slovenia | 42 | Anxiety/stress, apathy |

| Kitani-Morii et al. (2021) | Japan | 39 | Anxiety, depression, sleep |

| Kumar et al. (2020) | India | 832 | Anxiety, cognition, depression, fatigue, sleep |

| Oppo et al. (2020) | Italy | 32 | Cognitive issues, fatigue, mood, sleep |

| Palermo et al. (2020) | Italy | 28 | Anxiety, cognition, sleep |

| Prasad et al. (2020) | India | 100 | Anxiety, depression, sleep, fatigue |

| Salari et al. (2020) | Iran | 137 | Anxiety |

| Santos-García et al. (2020) | Spain | 570 | Psychological stress, sleep |

| Schirinzi et al. (2020) | Italy | 162 | Anxiety, other neuropsychiatric symptoms |

| Shalash et al. (2020) | Egypt | 38 | Anxiety/stress, depression |

| Simpson, Lekwuwa, and Crawford (2013) | England, Scotland, Wales | 1741 | Anxiety, cognition, sleep, fatigue |

| Song et al. (2020) | South Korea | 100 | Depression, fatigue, sleep, stress |

| Suzuki et al. (2021) | Japan | 100 | Cognition, depression, sleep, stress |

| Thomsen, Wallerstedt, Winge, and Bergquist (2021) | Sweden/Netherlands | 67 | Apathy, anxiety, depression, sleep |

| Zipprich, Teschner, Witte, Schönenberg, and Prell (2020) | Germany | 99 | Anxiety |

12. Next steps in addressing loneliness among PwP

12.1. Accurate identification

As the evidence recognizing loneliness as a major risk factor for a variety of adverse psychological and physical health outcomes mounts, identifying evidence-based interventions aimed at mitigating loneliness is critical. Acknowledging the wide-spread problem of loneliness and its negative sequelae may be a silver-lining of the Covid-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, the medical community has been slow to realize the adverse health impact of loneliness and, hence, has not provided patients with vital interventions needed to address it (Perissinotto et al., 2019). Healthcare practitioners and social scientists have been recently driven to further identify ways to proactively alleviate worldwide loneliness.

The first step toward is raising awareness and accurate screening for loneliness. A variety of international initiatives to draw awareness to the problem have begun in an attempt to increase the visibility of this challenging issue (cf., Cacioppo, Grippo, London, Goossens, & Cacioppo, 2015). In 2014, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) convened a team charged with the inclusion of a psychosocial “vital sign” in electronic health records (EHRs; Matthews, Adler, Forrest, & Stead, 2016). As such, the IOM recognized “Social Connections and Social Isolation” as an essential domain of inclusion and the evidence supporting this addition was equivalent to that of race, education, physical activity, tobacco use, and neighborhood characteristics. Loneliness can be adequately assessed using the UCLA three-item loneliness scale (Domènech-Abella et al., 2017; Musich, Wang, Hawkins, & Yeh, 2015) or the IOM recommended Berkman-Syme Social Network Index (Institute of Medicine, 2014) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Tips for clinicians.

|

12.2. Interventions

Although the research describing the risk factors and health outcomes associated with loneliness is robust, limited research is available to inform mitigation efforts. Novel interventions geared toward attenuating loneliness have been proposed for this growing global issue, which itself has been termed a pandemic, but the work is far from complete (Gardiner, Geldenhuys, & Gott, 2018). The following is an overview of the interventions that have demonstrated cursory effectiveness for targeting loneliness.

12.2.1. Psychological interventions

Considering that loneliness is highly subjective and perceptual, it could be hypothesized that psychological interventions may constitute an effective tool. Improving social contact alone does not necessarily assuage the maladaptive emotional response leading to loneliness (Käll et al., 2020). Additionally, counseling-based interventions are effective for reducing anxiety and depression, involving mental processes which can overlap with the cognitive changes associated with loneliness, and it is believed that positively affecting a person's mental processes may result in decreased loneliness (Mann et al., 2017).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Among the most evaluated psychological interventions for loneliness is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Hickin et al., 2021). The perceptual and cognitive biases that result in hypervigilance to negative social information, a common precursor to loneliness, is targeted by CBT interventions (J. T. Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009; S. Cacioppo et al., 2015). Specifically, the commonly used CBT technique of cognitive restructuring appears to be useful in helping people reframe perceptions of loneliness and self-efficacy with the aim of decreasing loneliness (Käll, Backlund, Shafran, & Andersson, 2020). In addition to in-person individual and group CBT, emerging evidence supports the feasibility of a newly developed CBT intervention for loneliness delivered via telehealth with guidance from a trained therapist (Käll, Backlund, et al., 2020).

Mindfulness. Mindfulness can be conceptualized as a process leading to a mental state of non-judgmental awareness of present moment experiences, including sensations, thoughts, bodily states, consciousness, and the environment, while fostering openness, curiosity, and acceptance (Käll, Backlund, et al., 2020). Mindfulness-based interventions are derived from Buddhist contemplative practices, emphasizing present-focused attention, and are nonreactive (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). The most well-known mindfulness-based intervention garnering empirical support is mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR, Kabat-Zinn, 1982). MBSR is an eight-week program that consists of weekly group-based classes with a trained instructor, daily audio-guided practice at home, and one day-long mindfulness retreat (Kabat-Zinn, 2013).

Evidence is available supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness/mediation, specifically utilizing a standardized eight-week MBSR program, for reducing the perception of loneliness in older adults (Creswell, 2017; Jazaieri, Goldin, Werner, Ziv, & Gross, 2012; Teoh, Letchumanan, & Lee, 2021; Veronese et al., 2021). In general, research appears to support that becoming more aware and present-focused may positively affect loneliness and social interactions (Lindsay, Young, Brown, Smyth, & Creswell, 2019). Mindfulness meditation has been associated with reduced depressive symptomology (Reangsing, Rittiwong, & Schneider, 2020), increased social cognition (Campos et al., 2019), and improved self-efficacy (Pandya, 2019), which may result in loneliness reduction. Additionally, preliminary evidence supports the effectiveness of mindfulness apps, thus, providing a convenient and inexpensive way for patients to engage in mindfulness in the comfort of their own homes (Boettcher et al., 2014; Figueroa & Aguilera, 2020; Lim, Condon, & DeSteno, 2015).

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wislon, 1999) is a psychological therapy that helps patients to evaluate their relationships with their thoughts and physical sensations through acceptance, mindfulness, and value-based action (Hayes, 2004). The overarching goal of ACT is to promote psychological flexibility (i.e., the ability to be mindful of experiences in the present moment) in an accepting and judgment-free manner, while maintaining a consistent behavior to one's values (Levin, Pistorello, Seeley, & Hayes, 2014). Limited but evolving evidence exists, delineating the negative association between psychological flexibility, ACT, and loneliness (Boman, Lundman, Nygren, Årestedt, & Santamäki Fischer, 2017; Frinking et al., 2020; Gardiner et al., 2018; Hamama-Raz & Hamama, 2015; Ziaee, Nejat, Amarghan, & Fariborzi, 2021), but the role of ACT in mitigating loneliness appears to be promising.

12.2.2. Social prescribing

Social prescribing is a holistic approach, consistent with the health and wellness precepts of the ICF model, empowering clinicians to refer patients for social support in their communities (Roland, Everington, & Marshall, 2020). Specialized clinicians have been long acquainted with social prescribing, as an intervention for addressing multifactorial physical and psychological health and social issues, with numerous publications reported over the years (Popay, Kowarzik, Mallinson, Mackian, & Barker, 2007). Specifically, there is increasing evidence that social prescribing improves patients reported well-being and reduces loneliness (Bickerdike, Booth, Wilson, Farley, & Wright, 2017; Foster et al., 2021; Kilgarriff-Foster & O’Cathain, 2015).

For PwP, there is a variety of ways to promote social engagement (e.g., boxing, dancing, yoga, meditation groups, music classes) (Popay et al., 2007), although the social distancing mandates associated with Covid-19 have led to cancellations of most in-person support and community groups, resulting in increased loneliness. However, through social prescribing, clinicians can direct patients to virtual exercise classes, virtual reality exercise games, and outdoor recreation activities of walking, hiking, biking, and running, thus, promoting connection with others in the community and encouraging PwP to continue exercising (Mirelman et al., 2016; Razani, Radhakrishna, & Chan, 2020; Schenkman et al., 2018; van der Kolk et al., 2019). Virtual support groups are growing at a rapid pace and provide PwP with tools for improving self-management of their disease and social connection (Subramanian et al., 2020; Visser, Bleijenbergh, Benschop, Van Riel, & Bloem, 2016).

Several social prescribing initiatives have been rolled out in the community and provide a potential avenue for improving loneliness. Specifically, the “Togetherness Program” at CareMore initiates home visits, regularly scheduled phone calls, and aims to bring patients in contact with appropriate social programs that already exist in the community (Masi, Chen, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2011; Murthy, 2020). In 2020, the Veteran's Administration began the “Compassionate Contact Corps Program” in response to the pandemic and has redeployed volunteers to make phone calls or virtual video visits to check on lonely veterans, while both the volunteers and those being called appear to benefit from this process (Winter & Gitlin, 2007). In the UK, the “Ways to Wellness” program (Newcastle Gateshed Clinical Commissioning Group, 2021) provides a model of social prescribing where a trained “Link Worker” is connected with a patient to identify health and wellness goals. Subsequently, the link worker connects the patient to community or volunteer groups, focusing on activities such as exercise, art-based therapy, gardening, and cooking (Moffatt, Steer, Lawson, Penn, & O’Brien, 2017). Considering the potential for social prescribing to translate into improved outcomes, proactive screening of loneliness by clinicians would be prudent (Subramanian et al., 2020).

12.3. Wellness strategies

Although a variety of interdisciplinary holistic health strategies have been implemented for PwP, they have almost exclusively focused on motor features (Subramanian et al., 2021). Helping PwP make lifestyle choices and creating structure and schedules to fill their daily lives during the pandemic has been posited as potentially helpful for preventing disruption of sleep pattern and exacerbation of mental health issues. Strategies such as exercise, health diet, sleep schedules, daily social activities, and mind-body approaches have been proposed as helpful interventions, even in the management of long-covid symptoms (Helmich & Bloem, 2020; Roth, Chan, & Jonas, 2021). Patients could be significantly benefited by some guidance in self-management in order to increase their sense of agency, when many other external factors related either to the pandemic or their disease are out of their control. Subramanian et al. (2021) have proposed several promising strategies designed to increase overall psychological wellness for PwP that include education, empowerment through teachable lifestyle choices, realigned health care team model, proactive outreach, social prescribing, and ultimately increased self-agency.

13. Conclusion

Due to the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 infections, the world has experienced an unprecedented global health crisis with tremendous morbidity and mortality. Covid-19 has dire implications in the psychosocial realm for all people around the world (Lai, Shih, Ko, Tang, & Hsueh, 2020), but for PwP the consequences may be particularly menacing. Although the risks of developing Covid-19 does not appear to be greater for PwP compared to the general population (Papa et al., 2020; Stoessl et al., 2020), the indirect impact of loneliness and social isolation have yet to be fully appreciated. Clinicians who treat PwP may not be aware of the negative health outcomes of loneliness, especially on non-motor symptoms, mental health, and quality of life (Subramanian et al., 2020). The added impact of the shelter-in-place and social distancing orders associated with the Covid-19 pandemic has further compounded the pandemic of loneliness. The interruption in social connection has led to increased reports of loneliness and associated increases in depression, anxiety, fatigue, cognitive decline, and apathy (Antonini et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2021; Prasad et al., 2020). We propose a call to action in order to increase awareness of how to pro-actively screen for loneliness and to devise creative solutions for mitigating this problem and preventing the devastating consequences of loneliness in PwP.

References

- Aarsland D., Batzu L., Halliday G.M., Geurtsen G.J., Ballard C., Ray Chaudhuri K., et al. Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 2021;7(1):47. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarsland D., Bronnick K., Williams-Gray C., Weintraub D., Marder K., Kulisevsky J., et al. Mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson disease: A multicenter pooled analysis. Neurology. 2010;75(12):1062–1069. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f39d0e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam E.K., Hawkley L.C., Kudielka B.M., Cacioppo J.T. Day-to-day dynamics of experience-cortisol associations in a population-based sample of older adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103(45):17058–17063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605053103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alschuler K.N., Roberts M.K., Herring T.E., Ehde D.M. Distress and risk perception in people living with multiple sclerosis during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2021;47 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anghelescu B.A.-M., Bruno V., Martino D., Roach P. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease: A single-centered qualitative study. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences/Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques. 2021;1–13 doi: 10.1017/cjn.2021.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini A. Health care for chronic neurological patients after COVID-19. The Lancet Neurology. 2020;19(7):562–563. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30157-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini A., Barone P., Marconi R., Morgante L., Zappulla S., Pontieri F.E., et al. The progression of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease and their contribution to motor disability and quality of life. Journal of Neurology. 2012;259(12):2621–2631. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6557-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini A., Leta V., Teo J., Chaudhuri K.R. Outcome of Parkinson's disease patients affected by COVID-19. Movement Disorders. 2020;35(6):905–908. doi: 10.1002/mds.28104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balci B., Aktar B., Buran S., Tas M., Donmez Colakoglu B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity, anxiety, and depression in patients with Parkinson's disease. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2021;44(2):173–176. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M., Cacioppo J.T., Hudziak J.J., Boomsma D.I. Genetic and environmental contributions to stability in loneliness throughout childhood. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2008;147B(3):385–391. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baschi R., Luca A., Nicoletti A., Caccamo M., Cicero C.E., D’Agate C., et al. Changes in motor, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms in Parkinson's disease and mild cognitive impairment during the COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.590134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister R.F., Leary M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beam C.R., Kim A.J. Psychological sequelae of social isolation and loneliness might be a larger problem in young adults than older adults. Psychological Trauma Theory Research Practice and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S58–S60. doi: 10.1037/tra0000774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickerdike L., Booth A., Wilson P.M., Farley K., Wright K. Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher J., Åström V., Påhlsson D., Schenström O., Andersson G., Carlbring P. Internet-based mindfulness treatment for anxiety disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy. 2014;45(2):241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boman E., Lundman B., Nygren B., Årestedt K., Santamäki Fischer R. Inner strength and its relationship to health threats in ageing-A cross-sectional study among community-dwelling older women. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2017;73(11):2720–2729. doi: 10.1111/jan.13341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomasang-Layno E., Fadlon I., Murray A.N., Himelhoch S. Antidepressive treatments for Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2015;21(8):833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma D.I., Willemsen G., Dolan C.V., Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T. Genetic and environmental contributions to loneliness in adults: The Netherlands twin register study. Behavior Genetics. 2005;35(6):745–752. doi: 10.1007/s10519-005-6040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Tavistock; 1979. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady S., D’Ambrosio L.A., Felts A., Rula E.Y., Kell K.P., Coughlin J.F. Reducing isolation and loneliness through membership in a fitness program for older adults: implications for health. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2020;39(3):301–310. doi: 10.1177/0733464818807820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broen M.P.G., Narayen N.E., Kuijf M.L., Dissanayaka N.N.W., Leentjens A.F.G. Prevalence of anxiety in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Movement Disorders. 2016;31(8):1125–1133. doi: 10.1002/mds.26643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Weston D., Greenberg N. Social and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with Parkinson's disease: A scoping review. Public Health. 2021;199:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E.G., Chahine L.M., Goldman S.M., Korell M., Mann E., Kinel D.R., et al. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with Parkinson's disease [Preprint] Neurology. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.14.20153023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J.T., Hawkley L.C. Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. Guilford Press; 2009. Loneliness; pp. 227–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J.T., Hawkley L.C., Thisted R.A. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(2):453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo J.T., Patrick W. W.W. Norton; 2008. Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo S., Capitanio J.P., Cacioppo J.T. Toward a neurology of loneliness. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140(6):1464–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0037618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo S., Grippo A.J., London S., Goossens L., Cacioppo J.T. Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10(2):238–249. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos D., Modrego-Alarcón M., López-del-Hoyo Y., González-Panzano M., Van Gordon W., Shonin E., et al. Exploring the role of meditation and dispositional mindfulness on social cognition domains: A controlled study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2019;10:809. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. Alzheimer's disease and healthy aging: Loneliness and social isolation linked to serious health conditions.https://www.cdc.gov/aging/publications/features/lonely-older-adults.html [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri K.R., Prieto-Jurcynska C., Naidu Y., Mitra T., Frades-Payo B., Tluk S., et al. The nondeclaration of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson's disease to health care professionals: An international study using the nonmotor symptoms questionnaire. Movement Disorders. 2010;25(6):704–709. doi: 10.1002/mds.22868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri K.R., Sauerbier A., Rojo J.M., Sethi K., Schapira A.H.V., Brown R.G., et al. The burden of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease using a self-completed non-motor questionnaire: A simple grading system. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2015;21(3):287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney J.W., Stacy M. Neuropsychiatric issues in Parkinson's disease. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2016;16(5):49. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtin E., Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2017;25(3):799–812. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle C.E., Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health. 2012;24(8):1346–1363. doi: 10.1177/0898264312460275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.D. Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology. 2017;68(1):491–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czaja S.J., Moxley J.H., Rogers W.A. Social support, isolation, loneliness, and health among older adults in the PRISM randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.728658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Rus Jacquet A., Bogard S., Normandeau C.P., Degroot C., Postuma R.B., Dupré N., et al. Clinical perception and management of Parkinson's disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Canadian experience. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2021;91:66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckx L., van den Akker M., Buntinx F., van Driel M. A systematic literature review on the association between loneliness and coping strategies. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2018;23(8):899–916. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2018.1446096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete E., Francesconi A., Palermo G., Mazzucchi S., Frosini D., Morganti R., et al. Prevalence and impact of COVID-19 in Parkinson's disease: Evidence from a multi-center survey in Tuscany region. Journal of Neurology. 2021;268(4):1179–1187. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditzen B., Heinrichs M. Psychobiology of social support: The social dimension of stress buffering. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2014;32(1):149–162. doi: 10.3233/RNN-139008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domènech-Abella J., Lara E., Rubio-Valera M., Olaya B., Moneta M.V., Rico-Uribe L.A., et al. Loneliness and depression in the elderly: The role of social network. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2017;52(4):381–390. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan N.J., Okereke O.I., Vannini P., Amariglio R.E., Rentz D.M., Marshall G.A., et al. Association of higher cortical amyloid burden with loneliness in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(12):1230. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan N.J., Wu Q., Rentz D.M., Sperling R.A., Marshall G.A., Glymour M.M. Loneliness, depression and cognitive function in older U.S. adults: Loneliness, depression and cognition. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2017;32(5):564–573. doi: 10.1002/gps.4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dossey L. Loneliness and health. EXPLORE. 2020;16(2):75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douma E.H., de Kloet E.R. Stress-induced plasticity and functioning of ventral tegmental dopamine neurons. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2020;108:48–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra P.A., Fokkema T. Social and emotional loneliness among divorced and married men and women: Comparing the deficit and cognitive perspectives. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2007;29(1):1–12. doi: 10.1080/01973530701330843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eggar R., Spencer A., Anderson D., Hiller L. Views of elderly patients on cardiopulmonary resuscitation before and after treatment for depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):170–174. doi: 10.1002/gps.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elran-Barak R., Mozeikov M. One month into the reinforcement of social distancing due to the COVID-19 outbreak: Subjective health, health behaviors, and loneliness among people with chronic medical conditions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(15):5403. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17155403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espay A.J., LeWitt P.A., Kaufmann H. Norepinephrine deficiency in Parkinson's disease: The case for noradrenergic enhancement: Norepinephrine deficiency in PD. Movement Disorders. 2014;29(14):1710–1719. doi: 10.1002/mds.26048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney M.P., Xu Y., Surface M., Shah H., Vanegas-Arroyave N., Chan A.K., et al. The impact of COVID-19 and social distancing on people with Parkinson's disease: A survey study. Npj Parkinson's Disease. 2021;7(1):10. doi: 10.1038/s41531-020-00153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa C.A., Aguilera A. The need for a mental health technology revolution in the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:523. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folk D., Okabe-Miyamoto K., Dunn E., Lyubomirsky S. Did social connection decline during the first wave of COVID-19? The role of extraversion. Collabra: Psychology. 2020;6(1):37. doi: 10.1525/collabra.365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster A., Thompson J., Holding E., Ariss S., Mukuria C., Jacques R., et al. Impact of social prescribing to address loneliness: A mixed methods evaluation of a national social prescribing programme. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2021;29(5):1439–1449. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frinking E., Jans-Beken L., Janssens M., Peeters S., Lataster J., Jacobs N., et al. Gratitude and loneliness in adults over 40 years: Examining the role of psychological flexibility and engaged living. Aging & Mental Health. 2020;24(12):2117–2124. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1673309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C., Geldenhuys G., Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: An integrative review. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2018;26(2):147–157. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garjani A., Hunter R., Law G.R., Middleton R.M., Tuite-Dalton K.A., Dobson R., et al. Mental health of people with multiple sclerosis during the COVID-19 outbreak: A prospective cohort and cross-sectional case–control study of the UK MS Register. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2021 doi: 10.1177/13524585211020435. 135245852110204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman E.R., Benjamin-Neelon S.E., Sonnenschein S. Alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey of US adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(24):9189. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D., Han B., Lu Y., Lv C., Fang X., Zhang Z., et al. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinson's Disease. 2020;2020:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2020/1216568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek A., Brettschneider C., Mallon T., Ernst A., Mamone S., Wiese B., et al. The impact of social engagement on health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in old age—Evidence from a multicenter prospective cohort study in Germany. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0715-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamama-Raz Y., Hamama L. Quality of life among parents of children with epilepsy: A preliminary research study. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2015;45:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(2):218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L.C., Hughes M.E., Waite L.J., Masi C.M., Thisted R.A., Cacioppo J.T. From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago health, aging, and social relations study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63(6):S375–S384. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.S375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley L.C., Thisted R.A., Cacioppo J.T. Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: Cross-sectional & longitudinal analyses. Health Psychology. 2009;28(3):354–363. doi: 10.1037/a0014400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawryluck L., Gold W.L., Robinson S., Pogorski S., Galea S., Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(7):7. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:639–665. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S.C., Strosahl K.D., Wislon K.G. Guilford Press; 1999. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J., Wrosch C., Schulz R. A lines-of-defense model for managing health threats: A review. Gerontology. 2013;59(5):438–447. doi: 10.1159/000351269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich L.M., Gullone E. The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(6):695–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinze N., Hussain S.F., Castle C.L., Godier-McBard L.R., Kempapidis T., Gomes R.S.M. The long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness in people living with disability and visual impairment. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.738304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmich R.C., Bloem B.R. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease: Hidden sorrows and emerging opportunities. Journal of Parkinson's Disease. 2020;10(2):351–354. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickin N., Käll A., Shafran R., Sutcliffe S., Manzotti G., Langan D. The effectiveness of psychological interventions for loneliness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2021;88 doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J. The potential public health relevance of social isolation and loneliness: Prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Public Policy & Aging Report. 2017;27(4):127–130. doi: 10.1093/ppar/prx030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annual Review of Psychology. 2018;69(1):437–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J., Smith T.B., Baker M., Harris T., Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holwerda T.J., Beekman A.T.F., Deeg D.J.H., Stek M.L., van Tilburg T.G., Visser P.J., et al. Increased risk of mortality associated with social isolation in older men: Only when feeling lonely? Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL) Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(4):843–853. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horesh D., Kapel Lev-Ari R., Hasson-Ohayon I. Risk factors for psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: Loneliness, age, gender, and health status play an important role. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2020;25(4):925–933. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press; 2014. Capturing social and behavioral domains in electronic health records: Phase 1; p. 18709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiri D., Petracca M., Moccia L., Tricoli L., Piano C., Bove F., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and psychiatric symptoms: The impact on Parkinson's disease in the elderly. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.581144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazaieri H., Goldin P.R., Werner K., Ziv M., Gross J.J. A randomized trial of mbsr versus aerobic exercise for social anxiety disorder: MBSR v. AE in SAD. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68(7):715–731. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H., Yim H.W., Song Y.-J., Ki M., Min J.-A., Cho J., et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiology and Health. 2016;38 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste D.V., Lee E.E., Cacioppo S. Battling the modern behavioral epidemic of loneliness: Suggestions for research and interventions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(6):553. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program of behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindful meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychaitry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Revised ed. Random House; 2013. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. [Google Scholar]

- Kalia L.V., Lang A.E. Parkinson's disease. The Lancet. 2015;386(9996):896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käll A., Backlund U., Shafran R., Andersson G. Lonesome no more? A two-year follow-up of internet-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for loneliness. Internet Interventions. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käll A., Shafran R., Lindegaard T., Bennett S., Cooper Z., Coughtrey A., et al. A common elements approach to the development of a modular cognitive behavioral theory for chronic loneliness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2020;88(3):269–282. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapel A., Serdoner D., Fabiani E., Velnar T. Impact of physiotherapy absence in COVID-19 pandemic on neurological state of patients with Parkinson disease. Topics in Geriatric Rehabilitation. 2021;37(1):50–55. doi: 10.1097/TGR.0000000000000304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kilgarriff-Foster A., O’Cathain A. Exploring the components and impact of social prescribing. Journal of Public Mental Health. 2015;14(3):127–134. doi: 10.1108/JPMH-06-2014-0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D.S., Cloonan S.A., Taylor E.C., Dailey N.S. Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitani-Morii F., Kasai T., Horiguchi G., Teramukai S., Ohmichi T., Shinomoto M., et al. Risk factors for neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease during COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. PLoS One. 2021;16(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool M.B., Geenen R. Loneliness in patients with rheumatic diseases: The significance of invalidation and lack of social support. The Journal of Psychology. 2012;146(1–2):229–241. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2011.606434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krendl A.C., Perry B.L. The impact of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults’ social and mental well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2021;76(2):e53–e58. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N., Gupta R., Kumar H., Mehta S., Rajan R., Kumar D., et al. Impact of home confinement during COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2020;80:32–34. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C.-C., Shih T.-P., Ko W.-C., Tang H.-J., Hsueh P.-R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2020;55(3) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh-Hunt N., Bagguley D., Bash K., Turner V., Turnbull S., Valtorta N., et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. 2017;152:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M.E., Pistorello J., Seeley J.R., Hayes S.C. Feasibility of a prototype web-based acceptance and commitment therapy prevention program for college students. Journal of American College Health. 2014;62(1):20–30. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.843533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D., Condon P., DeSteno D. Mindfulness and compassion: An examination of mechanism and scalability. PLoS One. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M.H., Eres R., Vasan S. Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: An update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2020;55(7):793–810. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01889-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim M.H., Rodebaugh T.L., Zyphur M.J., Gleeson J.F.M. Loneliness over time: The crucial role of social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2016;125(5):620–630. doi: 10.1037/abn0000162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay E.K., Young S., Brown K.W., Smyth J.M., Creswell J.D. Mindfulness training reduces loneliness and increases social contact in a randomized controlled trial. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116(9):3488–3493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1813588116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchetti M., Lee J.H., Aschwanden D., Sesker A., Strickhouser J.E., Terracciano A., et al. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. The American Psychologist. 2020 doi: 10.1037/amp0000690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J.J. Bancroft Press; 2000. A cry unheard: New insights into the medical consequences of loneliness. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald B., Hülür G. Well-being and loneliness in Swiss older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of social relationships. The Gerontologist. 2021;61(2):240–250. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffoni M., Giardini A., Pierobon A., Ferrazzoli D., Frazzitta G. Stigma experienced by Parkinson's disease patients: A descriptive review of qualitative studies. Parkinson's Disease. 2017;2017:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2017/7203259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann F., Bone J.K., Lloyd-Evans B., Frerichs J., Pinfold V., Ma R., et al. A life less lonely: The state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2017;52(6):627–638. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1392-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Martin P., Rodriguez-Blazquez C., Kurtis M.M., Chaudhuri K.R., on Behalf of the NMSS Validation Group The impact of non-motor symptoms on health-related quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease: Nms and HRQ O L in Parkinson's Disease. Movement Disorders. 2011;26(3):399–406. doi: 10.1002/mds.23462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi C.M., Chen H.-Y., Hawkley L.C., Cacioppo J.T. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2011;15(3):219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews K.A., Adler N.E., Forrest C.B., Stead W.W. Collecting psychosocial “vital signs” in electronic health records: Why now? What are they? What's new for psychology? American Psychologist. 2016;71(6):497–504. doi: 10.1037/a0040317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniels B., Bishop M. Participation and psychological capital in adults with Parkinson's disease: Mediation analysis based on the international classification of functioning, disability, and health. Rehabilitation Research, Policy, and Education. 2021;35(3):144–157. doi: 10.1891/RE-21-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniels B., Bishop M., Rumrill P.D., Jr. In: Disability studies for human services: An interdisciplinary and intersectionality approach. Harley D.A., Flaherty C., editors. Springer; 2021. Quality of life in neurological disorders; pp. 303–324. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniels B., Novak D., Braitsch M., Chitnis S. Management of Parkinson's disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Challenges and Opportunities. 2021;87(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- McGinty E.E., Presskreischer R., Han H., Barry C.L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324(1):93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesa Vieira C., Franco O.H., Gómez Restrepo C., Abel T. COVID-19: The forgotten priorities of the pandemic. Maturitas. 2020;136:38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michela J.L., Peplau L.A., Weeks D.G. Perceived dimensions of attributions for loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;43(5):929–936. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirelman A., Rochester L., Maidan I., Del Din S., Alcock L., Nieuwhof F., et al. Addition of a non-immersive virtual reality component to treadmill training to reduce fall risk in older adults (V-TIME): A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2016;388(10050):1170–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt S., Steer M., Lawson S., Penn L., O’Brien N. Link worker social prescribing to improve health and well-being for people with long-term conditions: Qualitative study of service user perceptions. BMJ Open. 2017;7(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy V.H. 1st ed. Harper Wave; 2020. Together: The healing power of human connection in a sometimes lonely world. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq R. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2014 doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10077.4828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musich S., Wang S.S., Hawkins K., Yeh C.S. The impact of loneliness on quality of life and patient satisfaction among older, sicker adults. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine. 2015;1 doi: 10.1177/2333721415582119. 233372141558211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwilambwe-Tshilobo L., Ge T., Chong M., Ferguson M.A., Misic B., Burrow A.L., et al. Loneliness and meaning in life are reflected in the intrinsic network architecture of the brain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2019;14(4):423–433. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsz021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naser Moghadasi A. One aspect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Iran: High anxiety among MS patients. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2020;41 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nausheen B., Gidron Y., Peveler R., Moss-Morris R. Social support and cancer progression: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67(5):403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcastle Gateshed Clinical Commissioning Group Ways to wellness. 2021. https://waystowellness.org.uk/about/what-is-ways-to-wellness/

- Nitschke J.P., Forbes P.A.G., Ali N., Cutler J., Apps M.A.J., Lockwood P.L., et al. Resilience during uncertainty? Greater social connectedness during COVID-19 lockdown is associated with reduced distress and fatigue. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2021;26(2):553–569. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppo V., Serra G., Fenu G., Murgia D., Ricciardi L., Melis M., et al. Parkinson's disease symptoms have a distinct impact on caregivers’ and patients’ stress: A study assessing the consequences of the covid-19 lockdown. Movement Disorders Clinical Practice. 2020;7(7):865–867. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Özdin S., Bayrak Özdin Ş. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2020;66(5):504–511. doi: 10.1177/0020764020927051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo G., Tommasini L., Baldacci F., Del Prete E., Siciliano G., Ceravolo R. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on cognition in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2020;35(10):1717–1718. doi: 10.1002/mds.28254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya S.P. Meditation program enhances self-efficacy and resilience of home-based caregivers of older adults with Alzheimer’s: A five-year follow-up study in two south Asian cities. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2019;62(16):663–681. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2019.1642278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa S.M., Brundin P., Fung V.S.C., Kang U.J., Burn D.J., Colosimo C., et al. Impact of the COVID -19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Movement Disorders. 2020;35(5):711–715. doi: 10.1002/mds.28067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepezko K., Hinkle J.T., Shepard M.D., Fischer N., Broen M.P.G., Leentjens A.F.G., et al. Social role functioning in Parkinson's disease: A mixed-methods systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2019;34(8):1128–1138. doi: 10.1002/gps.5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissinotto C., Holt-Lunstad J., Periyakoil V.S., Covinsky K. A practical approach to assessing and mitigating loneliness and isolation in older adults: Loneliness and isolation in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(4):657–662. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson D.B. The professional counselor's desk reference. 2nd ed. Springer; 2016. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health: Applications for professional counselors; pp. 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M., Sorensen S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2001;23(4):245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Poey J.L., Burr J.A., Roberts J.S. Social connectedness, perceived isolation, and dementia: Does the social environment moderate the relationship between genetic risk and cognitive well-being? The Gerontologist. 2017;57(6):1031–1040. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay J., Kowarzik U., Mallinson S., Mackian S., Barker J. Social problems, primary care and pathways to help and support: Addressing health inequalities at the individual level. Part I: The GP perspective. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2007;61(11):966–971. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.061937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad S., Holla V.V., Neeraja K., Surisetti B.K., Kamble N., Yadav R., et al. Parkinson's disease and COVID -19: Perceptions and implications in patients and caregivers. Movement Disorders. 2020;35(6):912–914. doi: 10.1002/mds.28088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razani N., Radhakrishna R., Chan C. Public lands are essential to public health during a pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]