Key Points

The prescribing patterns of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) in the CKD population remain largely unknown.

Prescription of SGLT-2i was low in patients with CKD, particularly those without diabetes.

Younger Black men with a history of heart failure and cardiologist visit were associated with higher odds of SGLT-2i prescription.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes, prescribing patterns, registry analysis, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i)

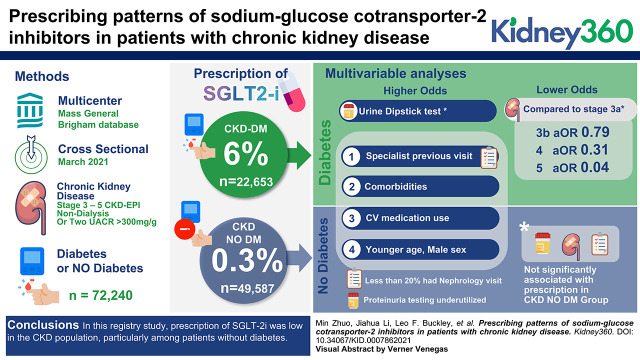

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) reduce kidney disease progression and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), regardless of diabetes status. However, the prescribing patterns of these novel therapeutics in the CKD population in real-world settings remain largely unknown.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included adults with stages 3–5 CKD included in the Mass General Brigham (MGB) CKD registry in March 2021. We described the adoption of SGLT-2i therapy and evaluated factors associated with SGLT-2i prescription using multivariable logistic regression models in the CKD population, with and without diabetes.

Results

A total of 72,240 patients with CKD met the inclusion criteria, 31,688 (44%) of whom were men and 61,265 (85%) White. A total of 22,653 (31%) patients were in the diabetic cohort, and 49,587 (69%) were in the nondiabetic cohort. SGLT-2i prescription was 6% in the diabetic cohort and 0.3% in the nondiabetic cohort. In multivariable analyses, younger Black men with a history of heart failure, use of cardiovascular medications, and at least one cardiologist visit in the previous year were associated with higher odds of SGLT-2i prescription in both diabetic and nondiabetic cohorts. Among patients with diabetes, advanced CKD stages were associated with lower odds of SGLT-2i prescription, whereas urine dipstick test and at least one subspecialist visit in the previous year were associated with higher odds of SGLT-2i prescription. In the nondiabetic cohort, CKD stage, urine dipstick test, and at least one nephrologist visit in the previous year were not significantly associated with SGLT-2i prescription.

Conclusions

In this registry study, prescription of SGLT-2i was low in the CKD population, particularly among patients without diabetes.

Introduction

CKD is a common noncommunicable disease (1). In the United States, 37 million Americans (15% of adults) were estimated to have CKD in 2018, with incident ESKD exceeding 130,000 and prevalent ESKD exceeding 785,000. In 2018, Medicare fee-for-service spending for beneficiaries with CKD or ESKD exceeded $130 billion (1). Finally, there are significant racial disparities in clinical outcomes. Black Americans comprise approximately 13% of the US population but >30% of patients with ESKD in the United States (2).

Despite the burden of CKD and ESKD, until recently, the only class of medications that has been shown to slow decline in kidney function was renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors (3–6). Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i), such as canagliflozin, empagliflozin, and dapagliflozin, are a breakthrough class of antidiabetic medications that increase urinary sodium and glucose excretion. Since the publication of the Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (EMPA-REG) in 2015, cardiovascular outcome trials demonstrated substantial cardiovascular and kidney protective effects (7–9). In 2019, Canagliflozin and Renal Events in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation (CREDENCE) trial showed that canagliflozin reduced the risk of kidney failure in patients with diabetes and an eGFR of 30–90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and a urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) of 300–5000 mg/g (10). More recently, in 2020, the Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease (DAPA-CKD) trial demonstrated that among patients with an eGFR of 25–75 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and a UACR of 200–5000 mg/g, dapagliflozin slowed kidney disease progression or death regardless of the presence or absence of diabetes (11). On the basis of trials, the US Food and Drug Administration approved: (1) in 2016, empagliflozin to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death in adults with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease; (2) in September 2019, canagliflozin to treat diabetic kidney disease; (3) in May 2020, dapagliflozin for heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction; and (4) in May 2021, after the publication of the DAPA-CKD trial in 2020, dapagliflozin to treat patients with CKD at risk of disease progression, regardless of diabetes and albuminuria status.

Although clinical trials have demonstrated the favorable cardiovascular and kidney effects of SGLT-2i therapy, little is known about to what extent these medications are being prescribed in real-world settings among patients with CKD. This study aimed to describe the adoption of SGLT-2i prescription in a large integrated health care system in the United States and to evaluate the factors associated with SGLT-2i prescription in patients with CKD, with and without diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

We conducted a cross-sectional cohort study using the CKD registry of Mass General Brigham (MGB), previously known as the Partners Healthcare system. This is an electronic health record (EHR)-based registry, as described in a previous study (12). Briefly, the MGB-CKD registry is a multicenter registry collecting data on patients in the MGB, a nonprofit hospital and provider-based network in eastern Massachusetts, serving close to 6 million patients. MGB includes multiple academic hospitals (e.g., Massachusetts General Hospital, Brigham and Women’s Hospital), community hospitals, and outpatient care facilities in Massachusetts, and primary care providers and specialists practice primarily in academic medical or community-based practices. Patients are included in the CKD registry first by identifying alive patients who are at least 18 years old and “active” in our system, defined as having a prior ambulatory or inpatient encounter within the previous 5.5 years or a future scheduled encounter, and having recently (within the past 2 years) updated wellness information such as vaccinations or laboratory values. The EHR calculated eGFR using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) serum creatinine equation, adjusting for race. Among these active adult patients, we identify patients with CKD on the basis of the following criteria: (1) two eGFR results <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 separated by at least 90 days, with both values recorded within the last 3 years; or (2) the most recent two UACR >300 mg/g; or (3) an EHR problem list diagnosis of ESKD. In the development of the CKD registry, the majority of proteinuria quantitative tests were conducted using UACR. A conversion term was used to convert urine protein-to-creatinine ratio values to UACR, as previously described (13). The findings reported in this manuscript are reported as UACR as presented in the CKD registry. The CKD registry includes data capturing demographics, comorbid conditions (on the basis of the EHR-based problem list), medication use, health care utilization, and laboratory results. All data in the CKD registry are updated in real-time on a daily basis.

The study was conducted under MGB Institutional Review Board exemption, meeting quality improvement research requirements.

Study Population

We accessed the CKD registry on March 25, 2021 and identified all active nondialysis adult patients with stages 3–5 CKD. Patients were classified into diabetic or nondiabetic cohorts on the basis of the presence or absence of diabetes as a comorbidity.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the percentage of patients with CKD who were prescribed an SGLT-2i. We identified SGLT-2i prescription as any active SGLT-2i order being present in the patient’s EHR record. We compared patients who were prescribed and not prescribed SGLT-2i treatment in the diabetic cohort and nondiabetic cohort, respectively. For each group, summary statistics for patient characteristics are presented as means with SDs for continuous data and total numbers and percentages for categorical data. Continuous variables were compared using the t test, and categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test.

Statistical Analyses

To assess the factors associated with SGLT-2i prescription, we conducted multivariable logistic regression models with prescription of SGLT-2i as the dependent variable. Predefined independent variables are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The nondiabetic cohort had fewer outcome events (SGLT-2i prescription) compared with the diabetic cohort; therefore, fewer predefined independent variables were included in the logistic regression model for the nondiabetic cohort (14). Both models included demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, and race), comorbid conditions (e.g., HF), medication prescription (e.g., RAAS inhibitor and diuretic), laboratory results (e.g., CKD stage), and health care utilization (e.g., at least one nephrologist visit in the previous year). Estimated adjusted odds ratios (aORs) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Table 2.

Factors associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors prescription among patients with diabetes and stages 3–5 CKD

| Characteristica | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 0.96 | 0.96 to 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Men | 1.80 | 1.60 to 2.02 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | ref | ||

| Black | 1.30 | 1.06 to 1.60 | 0.01 |

| Asian | 1.20 | 0.86 to 1.66 | 0.28 |

| Other/unknown | 1.39 | 1.13 to 1.70 | 0.002 |

| Hispanic | 0.82 | 0.64 to 1.06 | 0.14 |

| English speaking | 0.73 | 0.60 to 0.89 | 0.002 |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight to normal weight | ref | ||

| Overweight | 1.49 | 1.23 to 1.80 | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 1.49 | 1.23 to 1.79 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 1.03 | 0.82 to 1.29 | 0.78 |

| Heart failure | 1.20 | 1.03 to 1.40 | 0.02 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.17 | 1.02 to 1.34 | 0.02 |

| Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 1.20 | 1.07 to 1.36 | <0.001 |

| RAAS inhibitor | 1.87 | 1.62 to 2.15 | 0.003 |

| β-blocker | 1.14 | 1.01 to 1.30 | 0.04 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 0.90 | 0.80 to 1.01 | 0.08 |

| Diuretic | 0.99 | 0.88 to 1.12 | 0.88 |

| Statin | 1.76 | 1.45 to 2.14 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory | |||

| CKD stages | |||

| 3a | ref | ||

| 3b | 0.79 | 0.70 to 0.89 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 0.31 | 0.24 to 0.39 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 0.04 | 0.01 to 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin A1C at goal | 0.92 | 0.81 to 1.05 | 0.21 |

| Utilization metrics | |||

| Urine dipstick test ordered | 1.22 | 1.08 to 1.38 | <0.001 |

| At least one primary care physician visit in the previous year | 1.10 | 0.97 to 1.24 | 0.14 |

| At least one nephrologist visit in the previous year | 1.18 | 1.00 to 1.39 | 0.05 |

| At least one cardiologist visit in the previous year | 1.48 | 1.30 to 1.70 | <0.001 |

| At least one endocrinologist visit in the previous year | 2.36 | 2.10 to 2.66 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization within last 30 days | 1.47 | 1.06 to 2.06 | 0.02 |

| Number of emergency room visits in the previous year | |||

| 0 | ref | ||

| 1 | 1.17 | 0.98 to 1.41 | 0.09 |

| ≥2 | 0.78 | 0.58 to 1.04 | 0.09 |

| Number of hospitalizations in the previous year | |||

| 0 | ref | ||

| 1 | 0.95 | 0.79 to 1.14 | 0.59 |

| ≥2 | 1.10 | 0.88 to 1.38 | 0.40 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; ref, reference.

All variables in the table were included in the multivariable logistic regression model.

Table 3.

Factors associated with prescribing sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors among patients with stages 3–5 CKD and without diabetes

| Characteristica | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 0.95 | 0.94 to 0.96 | <0.001 |

| Men | 3.48 | 2.36 to 5.13 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | ref | ||

| Black | 1.86 | 1.04 to 3.31 | 0.04 |

| Asian | 0.89 | 0.22 to 3.66 | 0.87 |

| Other/unknown | 0.71 | 0.34 to 1.48 | 0.36 |

| Heart failure | 3.11 | 2.09 to 4.62 | <0.001 |

| RAAS inhibitor | 2.16 | 1.53 to 3.06 | <0.001 |

| Diuretic | 3.26 | 2.14 to 4.99 | <0.001 |

| CKD stages | |||

| 3a | ref | ||

| 3b | 1.14 | 0.79 to 1.63 | 0.48 |

| 4 | 0.53 | 0.26 to 1.08 | 0.08 |

| 5 | 0.56 | 0.13 to 2.43 | 0.44 |

| Urine dipstick test ordered | 1.05 | 0.65 to 1.69 | 0.84 |

| At least one nephrologist visit in the previous year | 1.39 | 0.82 to 2.34 | 0.22 |

| At least one cardiologist visit in the previous year | 3.14 | 2.16 to 4.56 | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; ref, reference.

All variables in the table were included in the multivariable logistic regression model.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA v15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All statistical testing was two-tailed, with P<0.05 designated as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 72,240 adult patients in the MGB-CKD registry were included in this study, with 22,653 (31%) in the diabetic cohort and 49,587 (69%) in the nondiabetic cohort. Baseline characteristics between those who were and were not prescribed an SGLT-2i are summarized in Table 1. Overall, approximately 5% patients were identified as Black, 85% as White, and 90% of patients as non-Hispanic.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with stages 3–5 CKD by diabetes status and prescription of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors

| Variable | Diabetic Cohort (N=22,653) | Nondiabetic Cohort (N=49,587) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonprescribed (N=21,211) | SGLT-2i Prescribed (N=1442) | P Value | Nonprescribed (N=49,442) | SGLT-2i Prescribed (N=145) | P Value | |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 76 (11) | 71 (9) | <0.001 | 77 (12) | 70 (11) | <0.001 |

| Men | 9953 (47) | 917 (48) | <0.001 | 20,708 (42) | 110 (76) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 16,997 (80) | 1089 (76) | <0.001 | 43,059 (87) | 120 (83) | 0.002 |

| Black | 1474 (7) | 126 (9) | 1720 (3) | 15 (10) | ||

| Asian | 625 (3) | 48 (3) | 894 (2) | 2 (1) | ||

| Other/unknown | 2115 (10) | 179 (12) | 3769 (8) | 8 (6) | ||

| Hispanic | ||||||

| No | 19,621 (93) | 1315 (91) | 0.14 | 42,486 (86) | 125 (86) | 0.06 |

| Yes | 1564 (7) | 126 (9) | 1513(3) | 9 (6) | ||

| Unknown | 26 (0) | 1 (0) | 5443 (11) | 11 (8) | ||

| English speaking | 18,574 (88) | 1243 (86) | 0.13 | 45,960 (93) | 137 (94) | 0.62 |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Medicare | 6267 (30) | 443 (31) | <0.001 | 13,400 (27) | 20 (14) | 0.002 |

| Medicaid | 283 (1) | 38 (3) | 415 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| Commercial | 1481 (7) | 171 (12) | 3587 (7) | 8 (6) | ||

| Missing | 13,180 (62) | 790 (55) | 32,040 (65) | 116 (80) | ||

| BMI | ||||||

| Underweight to normal weight (BMI <24.9 kg/m2) | 4064 (19) | 155 (11) | <0.001 | 15,370 (31) | 32 (22) | 0.001 |

| Overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2) | 6769 (32) | 471 (33) | 18,736 (38) | 48 (33) | ||

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 10,378 (49) | 816 (57) | 15,336 (31) | 65 (45) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 19,244 (91) | 1343 (93) | 0.002 | 35,680 (72) | 101 (70) | 0.5 |

| Heart failure | 4957 (23) | 380 (26) | 0.01 | 6747 (14) | 78 (54) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 6657 (31) | 587 (41) | <0.001 | 8968 (18) | 55 (38) | <0.001 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Aspirin | 11,746 (55) | 929 (64) | <0.001 | 8108 (16) | 49 (34) | <0.001 |

| RAAS inhibitor | 14,120 (67) | 1161 (81) | <0.001 | 9637 (20) | 78 (54) | <0.001 |

| β-blocker | 12,695 (60) | 948 (66) | <0.001 | 20,914 (42) | 98 (68) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 8398 (40) | 542 (38) | 0.13 | 14,886 (30) | 25 (17) | 0.001 |

| Diuretic | 11,210 (53) | 782 (54) | 0.31 | 19,054 (39) | 111 (77) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 17,184 (81) | 1313 (91) | <0.001 | 14,492 (29) | 84 (58) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory | ||||||

| Last eGFR, mean (SD), ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 41 (12) | 45 (9) | <0.001 | 45 (11) | 44 (10) | 0.24 |

| CKD stages | ||||||

| Stage 3a | 9602 (45) | 821 (57) | <0.001 | 29,391 (60) | 78 (54) | 0.41 |

| Stage 3b | 8025 (38) | 532 (37) | 15,274 (31) | 56 (39) | ||

| Stage 4 | 3019 (14) | 87 (6) | 4008 (8) | 9 (6) | ||

| Stage 5 | 565 (3) | 2 (0) | 769 (2) | 2 (1) | ||

| Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio | ||||||

| ≤30 mg/g | 1474 (7) | 123 (9) | <0.001 | 1646 (3) | 2 (1) | 0.006 |

| >30 mg/g | 11,873 (56) | 968 (67) | 9125 (18) | 41 (28) | ||

| Missing | 7864 (37) | 351 (24) | 38,671 (78) | 102 (70) | ||

| Hemoglobin A1C at goal | 8662 (41) | 462 (32) | <0.001 | — | — | — |

| Utilization metrics | ||||||

| Urine dipstick test ordered | 8105 (38) | 759 (53) | <0.001 | 5954 (12) | 31 (21) | <0.001 |

| At least one primary care physician visit in the previous year | 8718 (41) | 724 (50) | <0.001 | 18,168 (37) | 36 (25) | 0.003 |

| At least one nephrologist visit in the previous year | 2388 (11) | 235 (16) | <0.001 | 3628 (7) | 24 (17) | <0.001 |

| At least one cardiologist visit in the previous year | 4321 (19) | 478 (33) | <0.001 | 8340 (17) | 82 (57) | <0.001 |

| At least one endocrinologist visit in the previous year | 4526 (21) | 636 (44) | <0.001 | — | — | — |

| Hospitalization within last 30 days | 585 (3) | 52 (4) | 0.06 | 804 (2) | 11 (8) | <0.001 |

| Number of emergency room visits in the previous year | 0.03 | 0.6 | ||||

| 0 | 18,239 (86) | 1215 (84) | 43,876 (89) | 128 (88) | ||

| 1 | 1991 (9) | 166 (12) | 3937 (8) | 14 (10) | ||

| ≥2 | 981 (5) | 61 (4) | 1629 (3) | 3 (2) | ||

| Number of hospitalizations in the previous year | 0.12 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 16,835 (79) | 1120 (78) | 42,070 (85) | 104 (72) | ||

| 1 | 2542 (12) | 175 (12) | 4771 (10) | 25 (17) | ||

| ≥2 | 1834 (9) | 147 (10) | 2601 (5) | 16 (11) | ||

Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise. BMI, body mass index; RAAS, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; SGLT-2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; —, no data.

Diabetic Cohort

Among 22,653 patients with diabetes and CKD, 1442 (6%) were prescribed SGLT-2i. Compared with patients who were not prescribed SGLT-2i, those prescribed SGLT-2i were younger and more likely to be men. Those prescribed SGLT-2i had a greater comorbidity burden as reflected by higher prevalence of obesity, hypertension, HF, coronary artery disease, and more cardiovascular medication use (i.e., aspirin, RAAS inhibitor, β-blocker, and statin). Those prescribed SGLT-2i had a higher eGFR than those not prescribed SGLT-2i (mean eGFR 45 versus 41 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Although those prescribed SGLT-2i were more likely to have a urine dipstick test, approximately one quarter of patients with diabetes who were prescribed SGLT-2i did not have a UACR result. In multivariable analyses (Table 2), those who were older (aOR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.96 to 0.97; P<0.001) and who spoke English (aOR=0.73; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.89; P<0.001) had lower odds of being prescribed SGLT-2i. Compared with CKD stage 3a, CKD stages 3b (aOR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.89; P<0.001), 4 (aOR=0.31; 95% CI, 0.24 to 0.39; P<0.001), and 5 (aOR=0.04; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.17; P<0.001) were independently associated with lower odds of patients with diabetes being prescribed SGLT-2i. Having at least one nephrologist visit (aOR=1.18; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.39; P=0.05), cardiologist visit (aOR=1.48; 95% CI, 1.30 to 1.70; P<0.001), or endocrinologist visit (aOR=2.36; 95% CI, 2.10 to 2.66; P<0.001) in the previous year was associated with an increased likelihood of being prescribed SGLT-2i.

Nondiabetic Cohort

Of the 49,587 with CKD and without diabetes, 145 (0.3%) of them were prescribed SGLT-2i. Those prescribed SGLT-2i had more comorbid conditions (i.e., obesity, HF, and coronary artery disease) and more cardiovascular medication use (i.e., aspirin, RAAS inhibitors, β-blocker, diuretic, and statin) in unadjusted analyses. Those prescribed SGLT-2i had similar eGFR compared with those not on SGLT-2i (mean eGFR 44 versus 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2). Notably, >70% of patients with CKD and without diabetes did not have a UACR result in the last 2 years. More than half of patients without diabetes prescribed SGLT-2i had a cardiologist visit in the previous year, but only <20% had a nephrology visit in the previous year. In multivariable analyses (Table 3), older age (aOR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.94 to 0.96; P<0.001) was associated with lower odds of being prescribed SGLT-2i in patients with CKD and without diabetes. Men (aOR=3.48; 95% CI, 2.36 to 5.13; P<0.001) and Black patients (aOR=1.86; 95% CI, 1.04 to 3.31; P=0.04) had higher odds of being prescribed SGLT-2i. HF (aOR=3.11; 95% CI, 2.09 to 4.62; P<0.001), RAAS inhibitor prescription (aOR=3.11; 95% CI, 2.09 to 4.62; P<0.001), diuretic prescription (aOR=3.26; 95% CI, 2.14 to 4.99; P<0.001), and at least one cardiologist visit (aOR=3.14; 95% CI, 2.16 to 4.56; P<0.001) in the previous year were independently associated with increased SGLT-2i use. CKD stage, urine dipstick test, and at least one nephrologist visit in the previous year were not significantly associated with SGLT-2i prescription.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study utilizing health system CKD registry data showed that the adoption of SGLT-2i therapy remains low in the CKD population, particularly among patients without diabetes. Proteinuria testing was underutilized, particularly in patients with CKD and without diabetes. Younger Black men with cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities and taking cardiovascular medication had higher odds of being prescribed SGLT-2i in patients with and without diabetes. Specialist visits in the previous year were associated with higher SGLT-2i usage in patients with CKD and diabetes. This study highlights the vast opportunity for increased SGLT-2i therapy utilization for patients with CKD in a large integrated health system.

As the leading cause of ESKD in the United States (15), diabetes affects >10% or 34 million Americans (16). Both diabetes and kidney disease are associated with higher mortality (17). Since the publication of the EMPA-REG trial in 2015 (7), studies have demonstrated that SGLT-2i are cardioprotective and nephroprotective in patients with diabetic kidney disease (7–9). Given the observed benefits, the American Diabetes Association updated their guidelines promoting SGLT-2i use in diabetic patients with CKD or HF since 2018 (18), and the American Society of Nephrology Diabetic Kidney Task Force published a call to action promoting the uptake of SGLT-2i (19). A previous study using the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart, a large US administrative private payer claims database, demonstrated that the rate of SGLT-2i use in patients with diabetes and CKD stages 1–3 increased from 2% in 2015 to 8% in 2019 (20). A recent Optum study showed that the rate of SGLT-2i use in patients with diabetes and CKD stages 3–4 increased from 1% in 2013 to 13% in the first quarter of 2020 (21). Our study, focusing on more recent data from 2021 and patients with stages 3–5 CKD, illustrates that despite the publication of the dedicated kidney outcome trials CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD, SGLT-2i prescription remains low at 6% among patients with diabetes and CKD. Furthermore, our study provided a snapshot of SGLT-2i use in patients with CKD and without diabetes 6 months after the publication of the DAPA-CKD trial. Despite the well-demonstrated benefits in the DAPA-CKD trial (11), we still found low adoption (0.3%) of these novel agents in patients with stages 3–5 CKD and without diabetes. We acknowledge that at less than a year after the publication of DAPA-CKD, the use of SGLT-2i in patients with CKD and without diabetes in this study represents the baseline of adoption after the publication of the trial; evidence to support the use of SGLT-2i in patients with normoalbuminuric CKD without diabetes or HF is lacking. We expect that the use of SGLT-2i in patients with CKD and without diabetes may increase over time to some extent in our system as clinicians care for such patients in follow-up or consultation.

Gaps in care delivery for patients with CKD have been demonstrated in multiple studies (22,23). Estimates from multiple large observational CKD cohorts illustrate that proteinuria testing ranges from 10% to 50% in the CKD population (12,24). Despite established evidence and decades of clinical experience, RAAS inhibitors, which are inexpensive generic medications, are still underutilized for patients with CKD (12,24,25); a 1999–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey analysis showed that the use of RAAS inhibitors remained at ≤50% among patients with albuminuria and/or CKD (26). Our study highlights the slow translation of clinical benefits from SGLT-2i clinical trials to routine practice and suggests several barriers to widespread SGLT-2i implementation in the CKD population (Table 4). First, there is insufficient risk stratification due to missing proteinuria testing. In the CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD trials, SGLT-2i were demonstrated to be safe and efficacious in reducing kidney failure among patients with severely increased albuminuria across the eGFR spectrum down to 25 ml/min per 1.73 m2. The absence of proteinuria testing may lead to missing patients who otherwise would have been flagged at very high risk for CKD progression and suitable for SGLT-2i therapy. Our findings are similar to other large health systems, ranging from 32% of patients with CKD receiving albuminuria testing at Kaiser Permanente Southern California and 0% in another US-based CKD registry study (24,27). Second, providers may be unfamiliar with this novel class of medications, its appropriate clinical application, and its adverse effects (i.e., increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis, lower-limb amputations, and genital infection) (28). Thus, providers need to assess the benefit-risk profile and properly avoid risks. Our study found that diabetic CKD stage 3b was associated with less SGLT-2i prescription, but this practice is not supported by the evidence in the CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD trials, where SGLT-2i was safe and efficacious in reducing kidney failure in patients with an eGFR of 30–44 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommend initiating an SGLT-2i when the eGFR is >30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and SGLT-2i can be continued for kidney protection when the eGFR drops below 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (29). These statistics highlight the important role of nephrologists with expertise in managing advanced stages of CKD. Third, access to specialist care is a potential barrier, with our data showing that <10% of patients in the CKD registry saw a nephrologist in the MGB system in the previous year. Finally, a previous study showed that the utilization of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol–lowering therapies, the cornerstone of prevention in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, was low and increased dramatically after generic entry (30). The cost of SGLT-2i may be an issue for some patients on the basis of their insurance status (31); median annual out-of-pocket Medicare part D costs for these medications were about $1200 (32). Providers may be wary of prescribing medications if costs are high or unclear on the basis of the payer (33). Thus, despite the cost-effectiveness of SGLT-2i (34,35), affordability of SGLT-2i may contribute to low uptake and delays in care.

Table 4.

Barriers to sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and proposed solutions

| Barrier | Solution |

|---|---|

| Lack of proteinuria testing | Electronic health record–based registries to identify gaps in care among patients with CKD and/or diabetes |

| Provider unfamiliarity with medical class and clinical application | Continuous medical education efforts geared toward primary care providers and nephrologists |

| Access to specialist care | Expanded use of telemedicine and allied health professionals for SGLT-2i-specific consultation |

| Medication cost | Advocacy with policy makers, payers, and pharmaceutical companies to lower costs |

| Lack of support to specialist | A remote care management program that is algorithm based, pharmacist or care navigator led, and nephrologist supported |

SGLT-2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors.

Despite clear barriers to SGLT-2i implementation, there are real opportunities to address these challenges and facilitate prescription (Table 4). Increased utilization of data repositories utilizing EHR-based data, such as our CKD registry, to identify gaps in testing proactively are needed and have been previously described (36). A comprehensive, nationwide continuous medical education effort targeted toward primary care and nephrology is needed to ensure a broad understanding of the clinical application of SGLT-2i therapy. Expanded use of telemedicine care specific to supporting SGLT-2i therapy consults could promote improved access. Our investigators previously published a successful nephrology electronic consult program that supported medication prescription consults (37). A pilot study of clinical pharmacists using an SGLT-2i prescribing algorithm (38) in a CKD clinic was safe and efficient for SGLT-2i initiation and encompassed many of the opportunities outlined above (39). A remote care management program that is CKD registry guided, algorithm driven, led by either a pharmacist or care navigator, and supported by a specialist can overcome numerous barriers. Finally, advocacy efforts are needed to encourage policy makers, payers, and pharmaceutical companies to lower the cost of this class of medication to ensure equitable access (40). Although our study suggested Black patients were more likely to be on an SGLT-2i, conclusions about racial disparities of SGLT-2i prescription are limited by the underrepresentation of Black patients in our CKD registry (5%). However, given the established disparity in progression to ESKD, implementation of SGLT-2i should be emphasized in the Black community. Coupled with CKD registries where risk factors and interventions can be targeted at the community level, nontraditional health care settings, such as barbershops in Black communities (41), can be leveraged to emphasize the importance of screening and therapeutic options.

Our study has several limitations. First, as a single-center study, physicians were primarily practicing in a large academic health system located in Massachusetts, and so the generalizability of our study may be limited. In addition, data of patients who were comanaged by a health care system outside of MGB might be not accessible or not updated in real time. Second, in this registry cohort study, we cannot determine physicians who prescribe certain medications, decision-making rationale, and clinical context; therefore, we could not identify prescriber specialty characteristics or specific patient-level barriers to the adoption of SGLT-2i. For example, cost and nonapproved prior authorizations could be barriers to prescribers, which was not possible to determine on the basis of available registry data (33). Third, as a cross-sectional study, we were only able to identify SGLT-2i prescription at the study time, not adherence to the medication, and could not assess the trend of SGLT-2i prescription over the time. Some patients might have been prescribed SGLT-2i in the past, but discontinued them because of intolerance or serious adverse effects. Fourth, some data in the registry were missing or unavailable, such as insurance data, prescriber specialty, socioeconomic status, and education levels, which may affect our findings.

Despite the well-demonstrated benefits of SGLT-2i in slowing kidney progression and reducing cardiovascular death, the adaption of these novel agents remained low in the CKD population, particularly among patients without diabetes. Population-level interventions to increase SGLT-2i utilization and improve outcomes in patients with CKD are urgently needed to affect the incidence of ESKD.

Disclosures

J. Li is a full-time employee at Akebia Therapeutics, Inc. D.B. Mount reports authorship and royalty payments from UpToDate and consultancy payments from Allena Pharmaceuticals, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, and Horizon Therapeutics. M.L. Mendu is a Clinical Advisory Board member of RubiconMD. S.L. Tummalapalli reports consultancy to Bayer AG and funding from Scanwell Health. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

D.B. Mount is supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) grant P50AR060772. S.L. Tummalapalli is supported by the National Kidney Foundation Young Investigator Grant. M. Zhuo is supported by a NIH NIDDK T32 award DK007199. These funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, reporting, or the decision to submit for publication.

Data Sharing Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from M.L. Mendu. The data are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Author Contributions

J. Li and M.L. Mendu were responsible for data acquisition; J. Li, M.L. Mendu, and M. Zhuo designed the study; M. Zhuo was responsible for data analysis; all authors interpreted the results, contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting, accept personal accountability for their own contributions, and agree to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data Sytem : 2020 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, 2020. Available at: https://adr.usrds.org/2020. Accessed December 2, 2021

- 2.Norton JM, Moxey-Mims MM, Eggers PW, Narva AS, Star RA, Kimmel PL, Rodgers GP: Social determinants of racial disparities in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2576–2595, 2016. 10.1681/ASN.2016010027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Gherardi G, Garini G, Zoccali C, Salvadori M, Scolari F, Schena FP, Remuzzi G: Renoprotective properties of ACE-inhibition in non-diabetic nephropathies with non-nephrotic proteinuria. Lancet 354: 359–364, 1999. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10363-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou FF, Zhang X, Zhang GH, Xie D, Chen PY, Zhang WR, Jiang JP, Liang M, Wang GB, Liu ZR, Geng RW: Efficacy and safety of benazepril for advanced chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 354: 131–140, 2006. 10.1056/NEJMoa053107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S; RENAAL Study Investigators : Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001. 10.1056/NEJMoa011161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, Ritz E, Atkins RC, Rohde R, Raz I; Collaborative Study Group : Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 345: 851–860, 2001. 10.1056/NEJMoa011303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, Mattheus M, Devins T, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Inzucchi SE; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators : Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 373: 2117–2128, 2015. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Wilding JPH, Ruff CT, Gause-Nilsson IAM, Fredriksson M, Johansson PA, Langkilde A-M, Sabatine MS: Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 380: 347–357, 2018. 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M, Matthews DR; CANVAS Program Collaborative Group : Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 377: 644–657, 2017. 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu P-LL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW: Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 380: 2295–2306, 2019. 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou F-F, Mann JFE, McMurray JJV, Lindberg M, Rossing P, Sjöström CD, Toto RD, Langkilde A-M, Wheeler DC; DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators : Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 383: 1436–1446, 2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendu ML, Ahmed S, Maron JK, Rao SK, Chaguturu SK, May MF, Mutter WP, Burdge KA, Steele DJR, Mount DB, Waikar SS, Weilburg JB, Sequist TD: Development of an electronic health record-based chronic kidney disease registry to promote population health management. BMC Nephrol 20: 72, 2019. 10.1186/s12882-019-1260-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, Coresh J, Appel LJ, Astor BC, Chodick G, Collins AJ, Djurdjev O, Elley CR, Evans M, Garg AX, Hallan SI, Inker LA, Ito S, Jee SH, Kovesdy CP, Kronenberg F, Heerspink HJL, Marks A, Nadkarni GN, Navaneethan SD, Nelson RG, Titze S, Sarnak MJ, Stengel B, Woodward M, Iseki K; CKD Prognosis Consortium : Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: A meta-analysis. JAMA 315: 164–174, 2016. 10.1001/jama.2015.18202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR: A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 49: 1373–1379, 1996. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Bragg-Gresham J, Chen X, Gipson D, Gu H, Hirth RA, Hutton D, Jin Y, Kapke A, Kurtz V, Li Y, McCullough K, Modi Z, Morgenstern H, Mukhopadhyay P, Pearson J, Pisoni R, Repeck K, Schaubel DE, Shamraj R, Steffick D, Turf M, Woodside KJ, Xiang J, Yin M, Zhang X, Shahinian V: US Renal Data System 2019 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 75: A6–A7, 2020. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention : National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afkarian M, Sachs MC, Kestenbaum B, Hirsch IB, Tuttle KR, Himmelfarb J, de Boer IH: Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 302–308, 2013. 10.1681/ASN.2012070718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tsapas A, Wexler DJ, Buse JB: Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 41: 2669–2701, 2018. 10.2337/dci18-0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tuttle KR, Cherney DZ; Diabetic Kidney Disease Task Force of the American Society of Nephrology : Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition heralds a call-to-action for diabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 285–288, 2020. 10.2215/CJN.07730719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eberly LA, Yang L, Eneanya ND, Essien U, Julien H, Nathan AS, Khatana SAM, Dayoub EJ, Fanaroff AC, Giri J, Groeneveld PW, Adusumalli S: Association of race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor use among patients with diabetes in the US. JAMA Netw Open 4: e216139, 2021. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris ST, Patorno E, Zhuo M, Kim SC, Paik JM: Prescribing trends of antidiabetes medications in patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease, a cohort study. Diabetes Care 44: dc210529, 2021. 10.2337/dc21-0529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tummalapalli SL, Powe NR, Keyhani S: Trends in quality of care for patients with CKD in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1142–1150, 2019. 10.2215/CJN.00060119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bello AK, Ronksley PE, Tangri N, Kurzawa J, Osman MA, Singer A, Grill AK, Nitsch D, Queenan JA, Wick J, Lindeman C, Soos B, Tuot DS, Shojai S, Brimble KS, Mangin D, Drummond N: Quality of chronic kidney disease management in Canadian primary care. JAMA Netw Open 2: e1910704, 2019. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuttle KR, Alicic RZ, Duru OK, Jones CR, Daratha KB, Nicholas SB, McPherson SM, Neumiller JJ, Bell DS, Mangione CM, Norris KC: Clinical characteristics of and risk factors for chronic kidney disease among adults and children: An analysis of the CURE-CKD registry. JAMA Netw Open 2: e1918169, 2019. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCoy IE, Han J, Montez-Rath ME, Chertow GM: Barriers to ACEI/ARB use in proteinuric chronic kidney disease: An observational study. Mayo Clin Proc 96: 2114–2122, 2021. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu A, Farzadeh SN, Chang YJ, Kwong A, Lam S: Patterns of antihypertensive drug utilization among US adults with diabetes and comorbid hypertension: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2014. Clin Med Insights Cardiol 13: 1179546819839418, 2019. 10.1177/1179546819839418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sim JJ, Batech M, Danforth KN, Rutkowski MP, Jacobsen SJ, Kanter MH: End-stage renal disease outcomes among the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Creatinine Safety Program (Creatinine SureNet): Opportunities to reflect and improve. Perm J 21: 16–143, 2017. 10.7812/TPP/16-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patorno E, Pawar A, Bessette LG, Kim DH, Dave C, Glynn RJ, Munshi MN, Schneeweiss S, Wexler DJ, Kim SC: Comparative effectiveness and safety of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors versus glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in older adults. Diabetes Care 44: 826–835, 2021. 10.2337/dc20-1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Boer IH, Caramori ML, Chan JCN, Heerspink HJL, Hurst C, Khunti K, Liew A, Michos ED, Navaneethan SD, Olowu WA, Sadusky T, Tandon N, Tuttle KR, Wanner C, Wilkens KG, Zoungas S, Rossing P; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group : KDIGO 2020 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Available at https://kdigo.org/guidelines/diabetes-ckd/. Accessed December 1 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sumarsono A, Lalani HS, Vaduganathan M, Navar AM, Fonarow GC, Das SR, Pandey A: Trends in utilization and cost of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering therapies among Medicare beneficiaries: An analysis from the Medicare Part D database. JAMA Cardiol 6: 92–96, 2021. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tummalapalli SL, Montealegre JL, Warnock N, Green M, Ibrahim SA, Estrella MM: Coverage, formulary restrictions, and affordability of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors by US insurance plan types. JAMA Health Forum 2: e21420, 2021. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.4205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo J, Feldman R, Rothenberger SD, Hernandez I, Gellad WF: Coverage, formulary restrictions, and out-of-pocket costs for sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in the Medicare Part D program. JAMA Netw Open 3: e2020969, 2020. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao Y, Peterson E, Pagidipati N: Barriers to prescribing glucose-lowering therapies with cardiometabolic benefits. Am Heart J 224: 47–53, 2020. 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reifsnider O, Kansal A, Pimple P, Aponte-Ribero V, Brand S, Shetty S: Cost-effectiveness analysis of empagliflozin versus sitagliptin as second-line therapy for treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes in the United States. Diabetes Obes Metab 23: 791–799, 2021. 10.1111/dom.14268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reifsnider OS, Pimple P, Brand S, Bergrath Washington E, Shetty S, Desai NR: Cost-effectiveness of second-line empagliflozin versus liraglutide for type 2 diabetes in the United States. Diabetes Obes Metab 23: 791–799, 2021 10.1111/dom.14268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendu ML, Waikar SS, Rao SK: Kidney disease population health management in the era of accountable care: A conceptual framework for optimizing care across the CKD spectrum. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 122–131, 2017. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendu ML, McMahon GM, Licurse A, Solomon S, Greenberg J, Waikar SS: Electronic consultations in nephrology: Pilot implementation and evaluation. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 821–823, 2016. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Albajrami O, Zhuo M, Hawley CE, Paik JM: Decision algorithm for prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists for diabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1678–1688, 2020. 10.2215/CJN.02690320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Triantafylidis LK, Hawley CE, Fagbote C, Li J, Genovese N, Paik JM: A pilot study embedding clinical pharmacists within an interprofessional nephrology clinic for the initiation and monitoring of empagliflozin in diabetic kidney disease. J Pharm Pract 34: 428–437, 2019. 10.1177/0897190019876499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li J, Tummalapalli SL, Mendu ML: Advancing American kidney health and the role of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors: A missed opportunity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1584–1586, 2021. 10.2215/CJN.05450421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Victor RG, Lynch K, Li N, Blyler C, Muhammad E, Handler J, Brettler J, Rashid M, Hsu B, Foxx-Drew D, Moy N, Reid AE, Elashoff RM: A cluster-randomized trial of blood-pressure reduction in black barbershops. N Engl J Med 378: 1291–1301, 2018. 10.1056/NEJMoa1717250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]