Abstract

PURPOSE:

To assess ocular biometric determinants of dark-to-light change in anterior chamber angle width and identify dynamic risk factors in primary angle closure disease (PACD).

DESIGN:

Population-based cross-sectional study.

METHODS:

Chinese American Eye Study (CHES) participants underwent anterior segment OCT (AS-OCT) imaging in the dark and light. Static dark and light biometric parameters, including angle opening distance (AOD750), anterior chamber width (ACW), lens vault (LV), and pupillary diameter (PD) were measured and dynamic dark-to-light changes were calculated. Contributions by static and dynamic parameters to dark-to-light changes in AOD750 were assessed using multivariable linear regression models with standardized regression coefficients (SRCs) and semi-partial correlation coefficients squares (SPCC2). PACD was defined as three or more quadrants of gonioscopic angle closure.

RESULTS:

1,011 participants were included in the analysis. All biometric parameters differed between dark and light (p-value<0.05). On multivariable regression analysis, change in ACW (SRC=−0.35, SPCC2=0.081) and PD (SRC=−0.46, SPCC2=0.072) were the strongest determinants of dark-to-light change in AOD750 (overall R2=0.40). Dark-to-light increase in AOD750 was less in eyes with than without PACD (0.081 mm and 0.111 mm, respectively; p<0.001). ACW increased in eyes with PACD and decreased in eyes without PACD from dark to light (p<0.025), whereas change in PD was similar (p=0.28).

CONCLUSIONS:

Beneficial angle widening effects of transitioning from dark to light are attenuated in eyes with PACD, which appears related to aberrant dark-to-light change in ACW. These findings highlight the importance of assessing the angle in both dark and light to identify potential dynamic mechanisms of angle closure.

Graphical Abstract

The dark-to-light response typically leads to pupillary constriction and angle widening, which could be beneficial in eyes with angle closure. However, dark-to-light increases in angle width are attenuated in angle closure compared to open angle eyes, which contributes to persistent angle narrowing despite pupillary constriction. This finding appears to be related to aberrant dynamic change in scleral spur position, represented by anterior chamber width, an important determinant of dark-to-light change in angle width.

Introduction

Primary angle closure disease (PACD) is a spectrum of disease characterized by appositional or synechial closure of the anterior chamber angle. In eyes with PACD, aqueous outflow through the trabecular meshwork can be compromised by iridotrabecular contact, leading to increased intraocular pressure (IOP) and risk of primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG), a leading cause of permanent blindness worldwide.1-3 Static angle width is determined by the shape, position, and configuration of anterior segment anatomical structures, including the iris and lens.4,5 However, static biometric parameters remain insufficient in predicting which patients with early-stage PACD will develop PACG.6,7 Biometric properties of anterior segment anatomical structures are dynamic and constantly changing in response to a range of physiologic stimuli, including ambient lighting.8 While the most noticeable effect of the pupillary light reflex is on the iris, it also has effects on other anatomical structures, including the angle and lens.9-11

The dark-to-light pupillary response typically leads to physiologic pupillary constriction and angle widening.9,11,12 This effect could be beneficial in eyes with PACD and iridotrabecular contact in the dark by alleviating tissue congestion in the angle recess and reestablishing normal aqueous outflow. However, aberrant dark-to-light behavior of some anatomical structures, such as the iris, exacerbates angle narrowing and plays a key role as a dynamic risk factor for PACD.7,13 The volume of normal iris tissue dynamically changes with pupillary movements due to exchange of fluid between the stroma of the iris and its surroundings. When this process is compromised, the risk of PACD is increased.13-16 While reduced dark-to-light change in iris area (IA) has been identified as a dynamic risk factor in PACD, other determinants of dark-to-light change in angle width and their roles in PACD are less well-studied.

In this study, we develop statistical models using dark-to-light anterior segment OCT (AS-OCT) data from the Chinese American Eye Study (CHES), a population-based study of Chinese Americans, to investigate contributions of ocular biometric parameters to dark-to-light change in angle width.17 We then compare dark-to-light measurement changes among significant biometric determinants in eyes with and without PACD to identify potential dynamic risk factors in PACD.

Methods

Ethics committee approval was obtained from the University of Southern California Medical Center Institutional Review Board. All study procedures adhered to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. All study participants provided informed consent at the time of enrollment.

Clinical Assessment

Study participants were recruited as part of the Chinese American Eye Study (CHES), a population-based investigation of cause-specific ocular disease in 4,582 self-identified adult Chinese American individuals aged 50 years or older living in Monterey Park, CA.17 Each participant received a complete eye examination by a trained ophthalmologist, including automated refraction (Humphrey Automatic Refractor, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA), IOP measured by Goldman applanation tonometry (GAT), A-scan ultrasound biometry (4000B A-Scan/Pachymeter; DGH Technology, Inc), gonioscopy, and anterior segment OCT (AS-OCT) imaging (CASIA SS-1000, Tomey Corporation, Nagoya, Japan) in the upright seated position.17

Gonioscopy was performed under dark ambient lighting (0.1 cd/m2) with a 1-mm light beam and a Posner-type 4-mirror lens (Model ODPSG; Ocular Instruments, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA) by one of two trained ophthalmologists (D.W., C.L.G.). Care was taken to avoid light falling on the pupil, inadvertent indentation of the globe, and tilting of the lens greater than 10 degrees. The angle was graded in each quadrant according to the modified Shaffer classification system: grade 0, no structures visible; grade 1, non-pigmented TM visible; grade 2; pigmented TM visible; grade 3, scleral spur visible; grade 4, ciliary body visible. PACD was defined as an eye with three or more quadrants gonioscopic angle closure (grade 0 or 1) in the absence of potential causes of secondary angle closure, such as inflammation or neovascularization.18

AS-OCT imaging was performed under dark (0.1 cd/m2) and bright (27 cd/m2) ambient lighting prior to pupillary dilation. Some participants were unable to be imaged due to availability of the AS-OCT device, clinical flow, or ability to participate. Participants with PACD on gonioscopy were prioritized for AS-OCT imaging on any given examination day.

Exclusion criteria included eyes with history of medications that could affect angle width, laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI), intraocular surgery, or corneal opacities that precluded AS-OCT imaging. One eye per participant was selected at random for analysis using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) to avoid inter-eye correlations between independent and dependent variables.

Measurement of Ocular Biometric Parameters

128 two-dimensional cross-sectional AS-OCT images were acquired per eye per scan. AS-OCT images were imported into the Tomey SS-OCT Viewer software (version 3.0, Tomey Corporation, Nagoya, Japan). The software program automatically segmented anatomical structures and measured biometric parameters after a single expert human grader (A.A.P.) marked the location of the scleral spur and confirmed the accuracy of the segmentation. The scleral spur was defined as the inward protrusion of the sclera where a change in curvature of the corneoscleral junction was observed.19 Eyes with missing or corrupt images were excluded from the analysis.

AS-OCT images from both the horizontal (temporal-nasal) and vertical (superior-inferior) meridians were analyzed for the purposes of this study. As each image encompassed two sets of anterior iris and anterior chamber angle measurements, only measurements from the temporal quadrant (horizontal meridian) or inferior quadrant (vertical meridian) were analyzed to avoid intra-image correlations between independent and dependent variables. The temporal sector was selected to uphold convention established by a prior study. The inferior quadrant was selected over the superior quadrant to minimize superior eyelid artifacts.

Two biometric parameters describing angle width were measured: angle opening distance (AOD) and trabecular iris space area (TISA) 750 μm anterior to the scleral spur.20 These parameters were selected since AOD750 is strongly associated with gonioscopic angle closure and TISA750 is strongly associated with elevated IOP.21,22 Iris area (IA), iris curvature (IC), iris thickness 750μm from the scleral spur (IT750), lens vault (LV), anterior chamber width (ACW), pupillary diameter (PD), and anterior chamber area (ACA) were also measured.20,23

Intra-observer repeatability of averaged horizontal (nasal and temporal) and vertical (superior and inferior) parameter measurements was calculated in the form of intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) based on single images acquired in the dark from 20 open-angle eyes and 20 eyes with gonioscopic angle closure, each graded three months apart. ICC values reflected excellent measurement repeatability for all parameters, ranging between 0.89 (TISA750) to 0.98 (ACA).

Statistical Analysis

Dark-to-light change, defined as measurement value in the light minus measurement value in the dark, was calculated for each biometric parameter. Light greater than dark measurements produced positive change value whereas dark greater than light measurements produced negative change values. Means, standard deviations, and ranges were calculated for all continuous variables. AS-OCT measurements from the dark and light were compared using paired t-tests.

Univariable and multivariable linear regression analysis were performed with dark-to-light change in AOD750 or TISA750 as the dependent variable. Independent variables included the dark-to-light change in the remaining parameters and static dark measurements of all parameters. P-values, standardized regression coefficients (SRC; the relative influence of a variable on the R2 statistic per standard deviation increase in the independent variable), and R2 values were calculated to identify associated variables on univariable analysis. Independent variables with p-value < 0.1 on univariable analysis were used to develop the multivariable models. Variance inflation factors (VIF) were calculated for each model to assess for collinearity between variables. Models in which individual parameters had a VIF greater than 3.0 were excluded. In general, this meant that ACA and either ACD or LV were excluded from multivariable analysis. IT750 was also excluded from multivariable analysis, as the Tomey segmentation software failed to output measurements for more than half of our study cohort, especially from eyes with PACD. The contribution of each independent variable was estimated by the magnitude of SRCs and semipartial correlation coefficients squared (SPCC2s; decrease in the R2 statistic without the unique influence of variable). The R2 statistic reflected variation in angle width explained by the model’s independent variables. All statistical analysis was performed using Version 14.2 of the Stata® statistical software package (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Analyses were conducted using a significance level of 0.05.

Results

1,063 of the 4,582 participants of CHES (23.2%) underwent AS-OCT imaging under both dark and light ambient conditions. 21 participants (2.0%) were excluded due to history of medications or procedures that could affect angle width and 31 participants (2.9%) were excluded due one or more scleral spurs being unidentifiable. From the remaining 1,011 participants, one eye per participant (N = 1,011 eyes) was selected at random for analysis. 663 (65.6%) of the participants were female and 348 (34.4%) were male (Supplementary Table 1). The mean age of participants was 59.6 ± 7.4 years (range 50-94). 226 of the eyes (22.4%) fit the definition of PACD. Ocular parameters describing PACD eyes that were eligible for analysis (N = 226) closely resembled PACD eyes that were not eligible (N = 244) (Supplementary Table 2).

Statistical Models

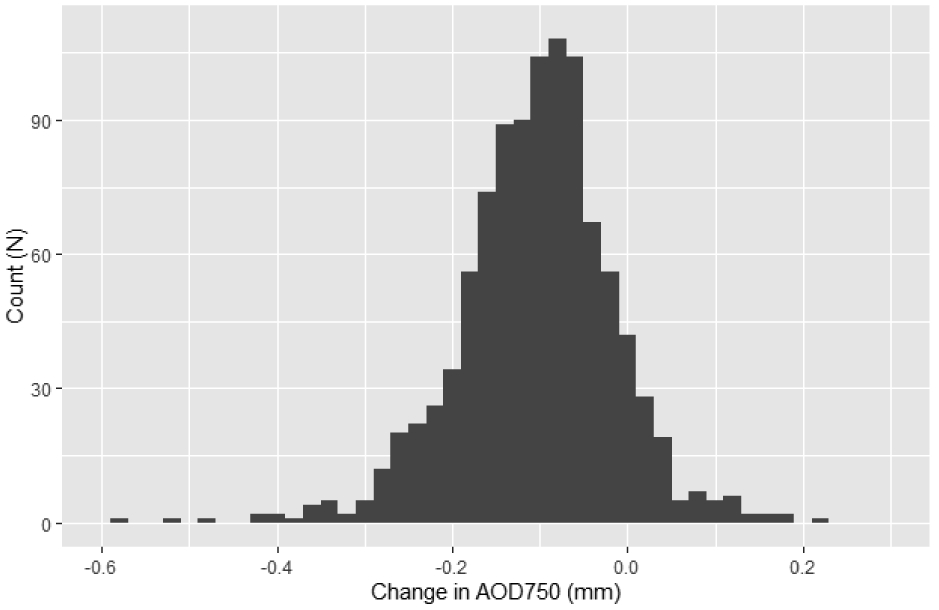

Temporal AOD750, TISA750, and IA significantly increased (p < 0.001) from dark to light (Table 1). 901 angles (89.1%) widened (increase in AOD750 > 0 mm) from dark to light (Figure 1). IC, IT750, ACD, ACW, PD, and ACA significantly decreased from dark to light (p < 0.022). The difference between dark and light LV was of borderline significance (p = 0.05)

Table 1:

Description of temporal and horizontal biometric parameters

| Dark | Light | P-value* | Dark-to-Light Change | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Mean (STD) | Range | N | Mean (STD) | Range | N | Mean (STD) | Range | |

| AOD750 (mm) | 1,008 | 0.39 (0.20) | 0 – 1.6 | 1,010 | 0.47 (0.21) | 0.067 – 1.6 | <0.001 | 1,007 | 0.10 (0.093) | −0.48 – 0.6 |

| TISA750 (mm2) | 1,008 | 0.19 (0.090) | 0 – 0.61 | 1,009 | 0.25 (0.10) | 0.22 – 0.88 | <0.001 | 1,006 | 0.052 (0.052) | −0.021 – 0.03 |

| IA (mm2) | 1,008 | 1.5 (0.22) | 0.42 – 2.3 | 1,010 | 1.7 (0.24) | 0.78 – 2.5 | <0.001 | 1,007 | 0.22 (0.12) | −0.63 – 0.75 |

| IC (mm) | 1,007 | 0.21 (0.16) | −1.2 – 0.63 | 1,003 | 0.21 (0.15) | −0.58 – 0.62 | 0.34 | 999 | −0.0036 (0.12) | −0.79 – 1.3 |

| IT750 (mm) | 371 | 0.39 (0.21) | 0.18 – 2.8 | 508 | 0.35 (0.26) | 0.15 – 3.8 | 0.030 | 334 | −0.032 (0.27) | −2.5 – 2.6 |

| ACD (mm) | 1,007 | 2.6 (0.34) | 1.5 – 3.5 | 1,009 | 2.5 (0.35) | 1.5 – 3.5 | <0.001 | 1,005 | −0.011 (0.054) | −0.42 – 0.53 |

| LV (mm) | 1,011 | 0.50 (0.27) | −0.30 – 1.5 | 1,011 | 0.51 (0.28) | −0.33 – 1.4 | 0.050 | 1,011 | 0.0059 (0.095) | −0.57 – 0.98 |

| ACW (mm) | 1,007 | 11.6 (0.40) | 10.2 – 12.8 | 1,009 | 11.5 (0.39) | 10.3 – 12.8 | <0.001 | 1,005 | −0.051 (0.14) | −0.56 – 0.7 |

| PD (mm) | 1,007 | 3.8 (0.74) | 1.6 – 6.0 | 1,009 | 2.5 (0.54) | 1.2 – 5.3 | <0.001 | 1,005 | −1.3 (0.53) | −4.1 – 1.7 |

| ACA (mm2) | 1,011 | 18.8 (3.5) | 8.9 – 28.9 | 1,011 | 18.3 (3.5) | 8.8 – 28.8 | <0.001 | 1,011 | −0.54 (0.32) | −4.2 – 1.2 |

Abbreviations: AOD750: Angle opening distance at 750 um from scleral spur. TISA750: Trabecular-iris space area at 750 um from scleral spur. IA: Iris Area. IC: Iris Curvature. IT750: Iris thickness at 750 μm from scleral spur. ACD: Anterior Chamber Depth. LV: Lens Vault. ACW: Anterior Chamber Width. PD: Pupillary Diameter. ACA: Anterior Chamber Area.

p-value calculated using paired t-tests comparing measurements in dark vs. measurements in light

Figure 1:

Histogram of dark-to-light change in AOD750

Abbreviations: AOD750: Angle opening distance at 750 um from scleral spur.

Age and all biometric parameters except change in IT750 and static dark AOD750 (p ≤ 0.58) were significantly associated (p ≤ 0.043) with dark-to-light change in AOD750 (Table 2). Dark-to-light change in ACW (p < 0.001, R2 = 0.19) and PD (p < 0.001, R2 = 0.17) explained the most variability in dark-to-light change in AOD750.

Table 2:

Linear regression models of determinants of dark-to-light change in temporal AOD750

| Simple Regression | Multiple Regression (R2: 0.40)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | p-value* | SRC | R2 | p-value** | SRC | SPCC2 | |

| Age, years | <0.001 | −0.15 | 0.022 | 0.12 | - | - | |

| Sex (0 = F, 1 = M) | 0.88 | 0.005 | 0.00 | 0.89 | - | - | |

| Dark-to-Light Change |

IA | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.015 | 0.061 | - | - |

| IC | <0.001 | −0.22 | 0.050 | <0.001 | −0.16 | 0.015 | |

| IT750 | 0.52 | −0.035 | 0.0013 | - | - | - | |

| ACD | 0.038 | −0.066 | 0.0043 | - | - | - | |

| LV | <0.001 | −0.19 | 0.037 | 0.015 | −0.072 | 0.0036 | |

| ACW | <0.001 | −0.43 | 0.19 | <0.001 | −0.35 | 0.081 | |

| PD | <0.001 | −0.41 | 0.17 | <0.001 | −0.46 | 0.072 | |

| ACA | <0.001 | −0.12 | 0.015 | - | - | - | |

| Static Dark | IA | 0.002 | −0.097 | 0.0093 | 0.20 | - | - |

| IC | 0.011 | −0.080 | 0.0064 | 0.82 | - | - | |

| IT750 | 0.043 | 0.11 | 0.011 | - | - | - | |

| ACD | <0.001 | 0.26 | 0.070 | - | - | - | |

| LV | <0.001 | −0.19 | 0.038 | 0.002 | −0.11 | 0.0062 | |

| ACW | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.022 | 0.71 | - | - | |

| PD | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.082 | 0.60 | - | - | |

| ACA | <0.001 | 0.27 | 0.075 | - | - | - | |

| AOD750 | 0.58 | −0.017 | 0.0003 | - | - | - | |

Abbreviations: AOD750: Angle opening distance at 750 um from scleral spur. IA: Iris Area. IC: Iris Curvature. IT750: Iris thickness at 750 μm from scleral spur. ACD: Anterior Chamber Depth. LV: Lens Vault. ACW: Anterior Chamber Width. PD: Pupillary Diameter. ACA: Anterior Chamber Area. SRC: Standardized Regression Coefficient. SPCC2: Squared semi-partial correlation coefficient.

Mean variance-inflation factor (VIF) = 1.8 (no individual VIF > 3.0)

p-values calculated using simple linear regressions

p-values calculated using age- and sex-controlled multiple linear regressions

In the age- and sex-adjusted multivariable model of dark-to-light change in temporal AOD750, change in IC, LV, ACW, and PD and static dark LV were all significantly associated (p ≤ 0.015) with change in AOD750, whereas change in IA and static dark IA, IC, ACW, and PD were not (p ≥ 0.061) (Table 2). The entire model explained 40% of the variability in dark-to-light change in AOD750. The most explanatory determinants were change in ACW (SRC = −0.35, SPCC2 = 0.081) and PD (SRC = −0.46, SPCC2 = 0.072).

Univariable and multivariable relationships between dark-to-light change in temporal TISA750 and other parameters closely resembled those of temporal AOD750 (Table 3). This model explained 34% of the variability in dark-to-light change in TISA750. The most explanatory determinants were again change in ACW (SRC = −0.26, SPCC2 = 0.046) and PD (SRC = −0.44, SPCC2 = 0.066).

Table 3:

Linear regression models of determinants of dark-to-light change in temporal TISA750

| Simple Regression | Multiple Regression (R2: 0.34)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | p-value* | SRC | R2 | p-value** | SRC | SPCC2 | |

| Age, years | 0.003 | −0.093 | 0.0087 | 0.40 | - | - | |

| Sex (0 = F, 1 = M) | 0.61 | 0.016 | 0.0003 | 0.63 | - | - | |

| Dark-to-Light Change |

IA | 0.008 | 0.083 | 0.0069 | 0.010 | −0.087 | 0.0045 |

| IC | <0.001 | −0.15 | 0.021 | <0.001 | −0.13 | 0.011 | |

| IT750 | 0.94 | −0.004 | <0.001 | - | - | - | |

| ACD | 0.80 | −0.008 | 0.0001 | - | - | - | |

| LV | <0.001 | −0.21 | 0.044 | <0.001 | −0.13 | 0.013 | |

| ACW | <0.001 | −0.39 | 0.15 | <0.001 | −0.26 | 0.046 | |

| PD | <0.001 | −0.35 | 0.12 | <0.001 | −0.44 | 0.066 | |

| ACA | 0.18 | −0.043 | 0.0018 | - | - | - | |

| Static Dark | IA | 0.002 | −0.097 | 0.0094 | 0.94 | - | - |

| IC | <0.001 | −0.19 | 0.035 | 0.011 | −0.11 | 0.0043 | |

| IT750 | 0.013 | 0.13 | 0.017 | - | - | - | |

| ACD | <0.001 | 0.30 | 0.093 | - | - | - | |

| LV | <0.001 | −0.27 | 0.072 | <0.001 | −0.15 | 0.011 | |

| ACW | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.018 | 0.70 | - | - | |

| PD | <0.001 | 0.23 | 0.054 | 0.12 | - | - | |

| ACA | <0.001 | 0.32 | 0.10 | - | - | - | |

| TISA750 | 0.26 | 0.036 | 0.0013 | - | - | - | |

Abbreviations: TISA750: Trabecular-iris space area at 750 um from scleral spur. IA: Iris Area. IC: Iris Curvature. IT750: Iris thickness at 750 μm from scleral spur. ACD: Anterior Chamber Depth. LV: Lens Vault. ACW: Anterior Chamber Width. PD: Pupillary Diameter. ACA: Anterior Chamber Area. SRC: Standardized Regression Coefficient. SPCC2: Squared semi-partial correlation coefficient.

Mean variance-inflation factor (VIF) = 1.8 (no individual VIF > 3.0)

p-values calculated using simple linear regressions

p-values calculated using age- and sex-controlled multiple linear regressions

Dark-to-light changes among biometric parameters of the inferior quadrant and univariable and multivariable models of dark-to-light change in inferior AOD750 and TISA750 generally resembled those of the temporal quadrant (Supplementary Tables 3 to 5). On multivariable analysis of inferior AOD750, change in IA and dark static AOD750 and PD were now significantly associated with dark-to-light change in AOD750 (p < 0.05), whereas change in IC and LV were no longer associated (p > 0.085). The most explanatory determinants remained change in PD (SRC = −0.43, SPCC2 = 0.075) and ACW (SRC = − 0.40, SPCC2 = 0.079). On multivariable analysis of inferior TISA750, static dark PD and TISA750 were now significantly associated with change in TISA750 (p < 0.006). The first and third most explanatory determinants were change in PD (SRC = −0.46, SPCC2 = 0.083) and ACW (SRC = −0.28, SPCC2 = 0.039).

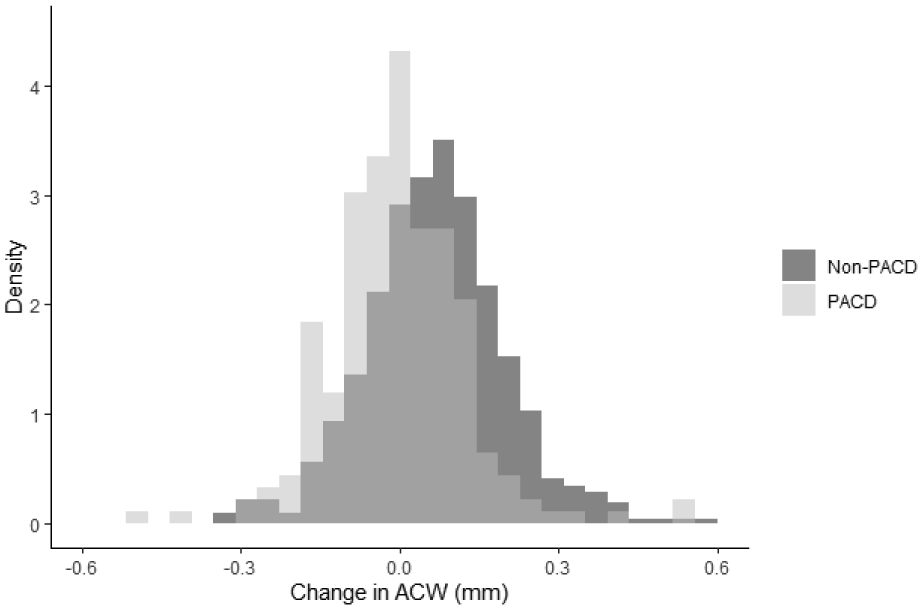

Differences Between PACD and Non-PACD Eyes

There was a significant difference (p < 0.001) in dark-to-light increase in temporal AOD750 between eyes with PACD (mean = 0.081 mm) and without PACD (mean = 0.111 mm) (Table 4). Among significant dynamic determinants of dark-to-light change in temporal AOD750, horizontal ACW tended to decrease in eyes without PACD and increase in eyes with PACD (p < 0.001) from dark to light (Figure 2). The effect was similar for LV (p < 0.001). There was no difference in mean dark-to-light change in IA, IC, and PD between eyes with and without PACD (p > 0.21).

Table 4:

Differences in dark-to-light change in temporal AOD750 and significant determinants between PACD and non-PACD Eyes

| Dark-to-Light Change Mean (STD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | No PACD (N = 785) |

PACD (N = 226) |

P-value* |

| AOD750 | 0.111 (0.098) | 0.081 (0.063) | <0.001 |

| ACW | −0.067 (0.133) | 0.004 (0.128) | <0.001 |

| LV | −0.001 (0.088) | 0.028 (0.113) | 0.001 |

| IA | 0.220 (0.113) | 0.215 (0.125) | 0.53 |

| IC | −0.001 (0.128) | −0.013 (0.085) | 0.206 |

| PD | −1.310 (0.508) | −1.280 (0.589) | 0.452 |

Abbreviations: AOD750: Angle opening distance at 750 um from scleral spur. IA: Iris Area. IC: Iris Curvature. IT750: Iris thickness at 750 μm from scleral spur. ACD: Anterior Chamber Depth. LV: Lens Vault. ACW: Anterior Chamber Width. PD: Pupillary Diameter. ACA: Anterior Chamber Area. SRC: Standardized Regression Coefficient. SPCC2: Squared semi-partial correlation coefficient. PACD = Primary Angle Closure Disease. IQR = Interquartile range.

p-values calculated using independent t-test

Figure 2:

Density histograms of dark-to-light change in ACW for PACD and non-PACD eyes

Abbreviations: ACW: Anterior chamber width. PACD: Primary angle closure disease.

There was a borderline significant difference (p = 0.069) in dark-to-light increase in inferior AOD750 between eyes with PACD (mean = 0.067 mm) and without PACD (mean = 0.085 mm) (Supplementary Table 6). Among significant dynamic determinants of dark-to-light change in inferior AOD750, only vertical ACW differed between eyes with and without PACD (p = 0.011). There was no difference in dark-to-light change in IA and PD between eyes with and without PACD (p > 0.20).

Horizontal ACW decreased by an average of 0.051 mm and median of 0.053 mm from dark to light (range −0.70 to 0.56 mm). The mean and median of the absolute magnitude of the dark-to-light change in ACW was 0.11 and 0.093 mm, respectively. 727 eyes (71.9%) had an absolute change in ACW of greater than 0.05 mm from dark to light.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we assessed ocular biometric determinants of dynamic dark-to-light change in angle width among Chinese Americans with and without PACD. There were significant dark-to-light changes among most biometric parameters, including an overall increase in angle width in the light. Multivariable models demonstrated that changes in ACW and PD were the strongest determinants of dark-to-light change in angle width overall. Finally, eyes with PACD demonstrated less dark-to-light temporal angle widening compared to eyes without PACD, which is primarily explained by smaller dark-to-light change in ACW in PACD eyes. We believe these results highlight the importance of assessing the angle in both dark and light and may provide insights into dynamic anatomical mechanisms of angle closure.

The anterior chamber angle is typically assessed in the dark, whether using gonioscopy or AS-OCT, because on average angles are narrowest and at highest risk of angle closure in the dark.24 However, the pupil only briefly maintains a static maximally-dilated state under physiologic conditions as pupillary constriction occurs after a brief period of dark adaptation.25 Therefore, angle widening that accompanies dark-to-light or dark-adapted pupillary constriction could help alleviate angle narrowing and re-establish aqueous outflow in eyes with extensive iridotrabecular contact. Our findings support previous findings that the dark-to-light pupillary response promotes angle widening in most eyes, with 89.1% of eyes in our study demonstrating greater temporal AOD750 in the light than dark.9,11,12

Dynamic dark-to-light increases in ACW are strongly associated with decreases in angle width, a finding that was consistent across all models developed in this study. In AS-OCT images, ACW reflects the horizontal position of the scleral spurs, with larger ACW representing more lateral positions. The average dark-to-light change in ACW appears small relative to average dark ACW. However, it is important to note that the scale of ACW is greater than other biometric parameters, and the magnitude of change in ACW can be either negative or positive. The mean of the absolute magnitude of the dark-to-light change in ACW was 0.11 mm, and 71.9% of eyes had lateral or medial movement of the scleral spur of greater than 0.05 mm, which suggests that fairly sizeable lateral shifts in scleral spur position are common with the dark-to-light pupillary response. In addition, ACW tended to decrease in open angle eyes and increase in eyes with PACD, which would contribute to angle widening and narrowing, respectively. Dark-to-light increases in ACW may be produced by contraction of the longitudinal fibers of the ciliary body muscles, which terminate anteriorly at the scleral spur.26 However, knowledge about the effect of the dark-to-light pupillary response on ciliary body muscles is sparse.

Dynamic dark-to-light increases in lens vault are weakly associated with decreases in angle width. In AS-OCT images, LV reflects the anteroposterior position of the lens in relation to the scleral spurs, with greater LV representing more anterior lens positions. However, LV is not a direct measurement of scleral spur position, unlike ACW, as LV can also be affected by changes in lens thickness or position due to change in tension of the zonular fibers.27 This may explain the weaker association between change in angle width and change in LV compared to change in ACW. Similar to ACW, LV tended to decrease in open angle eyes and increase in eyes with PACD, which would contribute to angle widening and narrowing, respectively.

Dark-to-light changes in ACW and LV interpreted together appear to indicate that scleral spur positions tend to shift anteromedially in open angle eyes, contributing to angle widening, and posterolaterally in PACD eyes, contributing to angle narrowing. It seems counterintuitive at first that medial movement of the scleral spurs and decreases in ACW contribute to angle widening, since smaller ACW is a known risk factor for angle closure.28 While this relationship holds true for static measurements of ACW in populations of eyes and smaller eyes tend to be at higher risk of angle closure overall, it is important to point out that our findings are based on dynamic changes among ACW measurements in individual eyes. In this case, decreases in ACW do not occur in isolation; dynamic decreases in ACW are accompanied by other anatomical changes, including anterior scleral spur movement and shifts in iris configuration, that together contribute to dynamic angle widening.

Dark-to-light increases in AOD750 and TISA750 were attenuated in eyes with PACD compared to eyes without PACD. The causative role of scleral spur position in this observed difference is strengthened by the lack of a significant difference between eyes with and without PACD in dark-to-light change in PD, the other primary dynamic determinant of change in angle width. While our results suggest that abnormal dark-to-light change in scleral spur position contributes to persistence of angle narrowing in eyes with PACD in the constricted state, they do not provide a clear explanation as to why this difference exists between eyes with and without PACD. One explanation is that dark-to-light change in scleral spur position is intrinsic behavior that varies between individuals due to differential innervation of the ciliary body muscles or rigidity of the sclera. An alternative explanation is these changes themselves have biometric determinants, such as the size of the lens, configuration of the zonular apparatus, or thickness of the choroid.29,30 Therefore, additional work is necessary to identify the cause of these differences in dynamic scleral spur behavior.

Reduced change in IA with the pupillary light reflex is a well-established dynamic risk factor in PACD.13-16 Based on our multivariable models, an increase in IA is associated with a decrease in inferior AOD750 and temporal and inferior TISA750. These findings support the effectiveness of our statistical method for identifying dynamic risk factors in PACD. However, in contrast to previous studies, we did not find any difference in dark-to-light change in IA among CHES participants with and without PACD. This may be due to the fact that CHES was a population-based study, and the majority of PACD cases, including cases of primary angle closure (PAC) and PACG, are relatively mild.31

Decreases in PD and IC were significantly associated with increases in angle width. Pupillary constriction is the primary anatomical sequala of the dark-to-light pupillary response and leads to an overall shift of iris tissue away from the angle recess. Therefore, it is intuitive that dark-to-light change in PD, along with ACW, is a primary determinant of change in angle width. Decreased IC is consistent with flattening of the iris, which directs its anterior surface away from the trabecular meshwork. However, it is interesting that dark-to-light pupillary constriction led to an overall increase in IC, which should be associated with decreased angle width. Taken together, the dynamic determinants indicate that dark-to-light change in angle width is a product of anatomical factors that lean toward angle widening (decreased PD, ACW, LV) over angle narrowing (increased IC). However, it is conceivable that in some eyes, this balance could be shifted toward angle narrowing by increases in ACW and LV, as observed in eyes with PACD. This may explain why 10.9% of eyes had angle narrowing due to the dark-to-light pupillary response and why some eyes with early PACD detected on dark-room gonioscopy develop PACG while others do not.

We included static biometric parameters in our multivariable models to control for the effects of baseline structural morphology, position, and configuration on observed dark-to-light change in angle width. While a few static parameters, including static dark LV, were significantly associated with dark-to-light change in angle width, their effects were weaker than those of PD and ACW. Therefore, static biometric properties appear to play a weak role in determining dark-to-light change in angle width.

Our study has several limitations. First, we used ACW and LV to infer change in scleral spur position since there are currently no methods to quantify this change directly in static coordinates. This highlights a general limitation with current AS-OCT studies that use the scleral spur as a reference landmark. While previous studies accounted for the effect of pupil size on biometric measurements, the effects of scleral spur position were generally disregarded.14-16 Based on the importance of scleral spur position as a determinant of angle width, future studies may benefit from using static structures, such as the cornea, to register images for biometric measurements. A second limitation is that the CASIA does not have inter-scan image registration. It is conceivable that dark-to-light differences among biometric measurements, specifically ACW, could be related to imaging different sectors or meridians of the anterior chamber.32 However, it is unlikely that this limitation significantly impacted our findings, as AS-OCT inter-scan reproducibility of ACW on the CASIA SS-1000 is excellent (ICC = 0.93).33 This limitation would also have biased our results toward the null and weakened our observed effects and associations. Third, we did not differentiate between eyes with PACS and PAC/PACG in our analyses due to the relatively small number and low severity of PAC/PACG cases in the CHES cohort.31 Therefore, it remains unclear if aberrant dynamic scleral spur behavior plays a role in PACD severity. Fourth, our models of temporal AOD750 and TISA750 only explained 40% and 33% of the total variance without ACD and ACA. Therefore, there are other significant determinants of dark-to-light change in angle width that remain unidentified. Fifth, a large number of IT750 measurements were missing due to measurement software errors. However, IT750 was weakly correlated with angle width on univariable analysis and would not have qualified for multivariable analysis. Sixth, we only studied the temporal and inferior quadrants. While our findings were generally conserved between these two quadrants, it is possible they may not generalize to all sectors of the angle. Finally, all CHES participants self-identified as Chinese American. Dark-to-light pupillary responses differ between ethnic Chinese and Caucasians; therefore, our findings may not generalize to other ethnic populations.11

In this study, we find that dark-to-light change in scleral spur position, represented by change in ACW and LV, appears to be an important determinant of change in angle width and could contribute to anatomical mechanisms of PACD. Our findings also suggest that clinicians and researchers could consider evaluating eyes with angle closure eyes in both dark and light, to assess maximum and minimum angle widths and ensure that beneficial dark-to-light angle widening is not compromised. Finally, additional study of the clinical impact of this differential dynamic dark-to-light scleral spur behavior in eyes with and without PACD is warranted to advance the evaluation of patients with angle closure and at risk for PACG.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants U10 EY017337 and K23 EY029763 from the National Eye Institute, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland; a Young Clinician Scientist Research Award from the American Glaucoma Society; a Grant-in-Aid Research Award from Fight For Sight, Inc; and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY.

Biography

Benjamin Xu, MD, PhD, graduated from Yale University with a Bachelor of Science in Biomedical Engineering. He received his MD and PhD from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons as a member of the NIH-funded Medical Scientist Training Program. Dr. Xu completed his ophthalmology residency at the LAC+USC Medical Center / USC Roski Eye Institute and glaucoma fellowship at the UCSD Shiley Eye Institute. He is now a member of the glaucoma service at the USC Roski Eye Institute. His research focuses on studying the impact of angle closure disease on patient populations in the United States and developing new clinical methods to detect patients at high risk for primary angle closure glaucoma.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

J.L., B.B., X.J., A.A.P., G.R., R.M., B.X. have no financial disclosures. R.V. is a consultant for Allegro Inc., Allergan, and Bausch Health Companies Inc.

References

- 1.Quigley H, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: A review. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311(18):1901–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foo LL, Nongpiur ME, Allen JC, et al. Determinants of angle width in Chinese Singaporeans. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):278–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu BY, Lifton J, Burkemper B, et al. Ocular Biometric Determinants of Anterior Chamber Angle Width in Chinese Americans: The Chinese American Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;220:19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quigley HA. Angle-Closure Glaucoma-Simpler Answers to Complex Mechanisms: LXVI Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quigley HA. The Iris Is a Sponge: A Cause of Angle Closure. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(1):1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zele AJ, Gamlin PD. Editorial: The Pupil: Behavior, Anatomy, Physiology and Clinical Biomarkers. Front Neurol. 2020;11:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung CKS, Cheung CYL, Li H, et al. Dynamic analysis of dark-light changes of the anterior chamber angle with anterior segment OCT. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(9):4116–4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma S, Baskaran M, Rukmini A V., et al. Factors influencing the pupillary light reflex in healthy individuals. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2016;254(7):1353–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang D, Chiu C, He M, Wu L, Kao A, Lin S. Differences in baseline dark and the dark-to-light changes in anterior chamber angle parameters in whites and ethnic chinese. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(13):9404–9410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu BY, Penteado RC, Weinreb RN. Diurnal Variation of Optical Coherence Tomography Measurements of Static and Dynamic Anterior Segment Parameters. J Glaucoma. 2018;27(1):16–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soh Z Da, Thakur S, Majithia S, Nongpiur ME, Cheng CY. Iris and its relevance to angle closure disease: A review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021;105(1):3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quigley HA, Silver DM, Friedman DS, et al. Iris cross-sectional area decreases with pupil dilation and its dynamic behavior is a risk factor in angle closure. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(3):173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Li SZ, Li L, He MG, Thomas R, Wang NL. Dynamic iris changes as a risk factor in primary angle closure disease. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(1):218–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aptel F, Chiquet C, Beccat S, Denis P. Biometric evaluation of anterior chamber changes after physiologic pupil dilation using Pentacam and anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(7):4005–4010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varma R, Hsu C, Wang D, Torres M, Azen SP. The Chinese American eye study: Design and methods. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2013;20(6):335–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster PJ, Buhrmann R, Quigley HA, Johnson GJ. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence surveys. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(2):238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho SW, Baskaran M, Zheng C, et al. Swept source optical coherence tomography measurement of the iris-trabecular contact (ITC) index: A new parameter for angle closure. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251(4):1205–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung CKS, Weinreb RN. Anterior chamber angle imaging with optical coherence tomography. Eye. 2011;25(3):261–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narayanaswamy A, Sakata LM, He MG, et al. Diagnostic performance of anterior chamber angle measurements for detecting eyes with narrow angles: An anterior segment OCT study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(10):1321–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu BY, Burkemper B, Lewinger JP, et al. Correlation between Intraocular Pressure and Angle Configuration Measured by OCT: The Chinese American Eye Study. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2018;1(3):158–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansouri M, Ramezani F, Moghimi S, et al. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography parameters in phacomorphic angle closure and mature cataracts. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(11):7403–7409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SD, Singh K, Lin SC, et al. Evaluation of the anterior chamber angle in glaucoma: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(10):1985–1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce DS, Feigl B, Zele AJ. The effects of short-term light adaptation on the human post-illumination pupil response. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(13):5672–5680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grierson I, Lee WR, Abraham S. Effects of pilocarpine on the morphology of the human outflow apparatus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1978;62(5):302–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nankivil D, Heilman BM, Durkee H, et al. The zonules selectively alter the shape of the lens during accommodation based on the location of their anchorage points. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(3):1751–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nongpiur ME, Sakata LM, Friedman DS, et al. Novel association of smaller anterior chamber width with angle closure in Singaporeans. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(10):1967–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arora KS, Jefferys JL, Maul EA, Quigley HA. The choroid is thicker in angle closure than in open angle and control eyes. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(12):7813–7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang W, Wang W, Gao X, et al. Choroidal thickness in the subtypes of angle closure: An EDI-OCT study. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(13):7849–7853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu BY, Liang S, Pardeshi AA, et al. Differences in Ocular Biometric Measurements among Subtypes of Primary Angle Closure Disease: The Chinese American Eye Study. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2021;4(2):224–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu BY, Israelsen P, Pan BX, Wang D, Jiang X, Varma R. Benefit of measuring anterior segment structures using an increased number of optical coherence tomography images: The Chinese American Eye Study. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(14):6313–6319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pardeshi AA, Song AE, Lazkani N, Xie X, Huang A, Xu BY. Intradevice repeatability and interdevice agreement of ocular biometric measurements: A comparison of two swept-source anterior segment oct devices. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2020;9(9):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.