Abstract

Objective:

Emotion regulation is a transdiagnostic mechanism with relevance to the etiology, maintenance, and treatment of a wide range of clinically relevant outcomes. The current study applied systematic review methods to summarize the existing literature examining racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation.

Methods:

We systematically searched four electronic databases (PsycINFO, Embase, MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus) using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.

Results:

Of the initial 1,253 articles, 25 met the inclusion criteria. Findings for emotion regulation strategies generally provide evidence for racial/ethnic differences (71% of reviewed studies), with ethnoracial minorities largely exhibiting greater use of emotion regulation strategies. Whereas the results for emotion regulation potential were slightly more mixed (63% of reviewed studies found racial/ethnic differences), ethnoracial minorities were also largely found to report lower emotion regulation potential.

Conclusion:

This review advances literature by providing additional support for racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation.

Keywords: Emotion Regulation, Emotion Dysregulation, Expressive Suppression, Cognitive Reappraisal, Racial Differences, Ethnic Differences, Systematic Review

Emotion regulation is one of the fastest growing areas in psychological research (Tull & Aldao, 2015b). Empirical investigations over the past two decades highlight the transdiagnostic nature of emotion regulation (Cludius et al., 2020). Across these studies, emotion regulation has emerged as a key mechanism underlying the etiology, maintenance, and exacerbation of a wide array of clinically relevant outcomes (for reviews, see Aldao et al., 2010; Gratz & Tull, 2010a; Hu et al., 2014; Weiss, Sullivan, et al., 2015), including posttraumatic stress disorder (Tull et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2013), depression (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015; Tull & Gratz, 2008), anxiety (Roemer et al., 2009; Vujanovic et al., 2008), borderline personality disorder (Gratz et al., 2006; Gratz et al., 2008), substance use disorder (Fox et al., 2007; Fox et al., 2008), disordered eating (Lavender & Anderson, 2010; Lavender et al., 2014), nonsuicidal self-injury (Gratz & Chapman, 2007; Gratz & Tull, 2010b), HIV/sexual risk (Messman-Moore et al., 2010; Tull et al., 2012), and aggression (Gratz et al., 2009; Shorey et al., 2011). Moreover, results stemming from early clinical research studies highlight the utility of targeting emotion regulation as a target, outcome, and mechanism of psychological treatments (for a review, see Gratz et al., 2015). Collectively, this literature underscores the clinical significance of research on emotion regulation.

A key limitation of past studies on emotion regulation, however, is that the vast majority have been conducted in the United States among samples of predominantly white individuals. Of importance, existing literature suggests the potential for racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation. For instance, worldviews, ideologies, values, and concepts of the self vary across racial and ethnic groups and may influence how members of these groups evaluate or appraise emotional stimuli (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, 1998; Matsumoto, 2006; Schwartz & Bardi, 2001). Individuals from different racial and ethnic groups may diverge in their criteria for assessing event desirability, including their experience of specific emotions, related to culturally sanctioned rules and norms and related social reactions (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Roseman et al., 1995). Relatedly, tied to important aspects of cultural identity (e.g., individualistic versus collectivistic orientation) is the perception that emotional experiences are (un)controllable and (un)predictable, and thus these may differ as a function of race and ethnicity (De Leersnyder et al., 2013). Individuals from different racial and ethnic groups may also vary in how they modulate emotions. Emotions communicate important information to others (Keltner & Haidt, 1999)—divergent expectations for social behavior across racial and ethnic groups produce different guidelines for the regulation of emotional expression (Matsumoto, 1993). Indeed, one’s racial and ethnic social context provides valuable cues that are referenced when regulating emotions as well as differentially encourages and reinforces emotional responding, resulting in divergent conditions under which emotional responses are sanctioned (Butler et al., 2007). For example, racial and ethnic groups that are characterized by a collectivistic orientation prioritize in-group over individual goals, necessitating members modify their emotional experiences to meet the needs of the group (Hofstede, 2001). Specifically, cultural ideologies of conformity, obedience, and in-group cohesion among racial and ethnic groups that value collectivism produce standards for individuals to down-regulate emotional expressions that threaten in-group harmony and to encourage expression of emotions that maintain or create harmony. Despite evidence that racial and ethnic groups reference divergent ideological belief systems for guidelines on how to evaluate and modulate emotionally salient cues in their environments, racial and ethnic group differences are often overlooked in research on emotion regulation.

Notably, numerous definitions for emotion regulation have been set forth in the extant research (Tull & Aldao, 2015a), and research examining racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation has utilized these diverse conceptualizations. Tull and Aldao (2015a) distinguished between emotion regulation potential and strategies. Emotion regulation potential refers to the typical or dispositional ways in which individuals understand, regard, and respond to their emotional experiences (see Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Thompson, 1994; Weiss et al., 2015). Existing models of emotion regulation potential are multi-faceted and emphasize ones’ awareness, understanding, and acceptance of emotions; ability to control behaviors when experiencing emotional distress; access to emotion regulation strategies that are perceived as effective and flexibly applied to modulate the duration and/or intensity of aversive emotional experiences; and willingness to experience emotional distress as part of pursing meaningful activities in life. Conversely, consistent with the extended process model of emotion regulation (Gross, 2015), emotion regulation may be defined by the type and timing of particular strategies at different points in the emotion-generative process. These models of emotion regulation focus on the specific strategies used by individuals to influence the experience and expression of emotions (see Cole et al., 1994; Koole, 2009). Broadly speaking, these strategies can function in either adaptive or maladaptive ways (Gross, 2015), with putatively adaptive strategies (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) related to enhanced psychological well-being and putatively maladaptive strategies (e.g., expressive suppression) showing robust relations with psychological disorders (Aldao et al., 2010). Potential and strategy models of emotion regulation capture unique and significant aspects of the larger construct of emotion regulation, and thus their dual examination provides useful and comprehensive data on emotion regulation across racial and ethnic groups.

While empirical investigations of racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation are relatively scant, early research findings in this area provide support for divergent patterns of emotion regulation strategies across different racial and ethnic groups. For instance, Asian, Black, and Hispanic individuals have been shown to report more expressive suppression – or attempts to inhibit an emotional response – compared to white individuals (Gross & John, 2003; Gross et al., 2006). Conversely, mixed findings have been found for cognitive reapprisal – or re-evaluating the meaning of a given situation to reduce its emotional impact – among racial and ethnic groups, with one study finding that Asian vs. American individuals exhibited greater beliefs that emotions are changeable (Qu & Telzer, 2017) and others finding no significant racial and ethnic differences in the use of this emotion regulation strategy (Gross & John, 2003; Tsai et al., 2002; Tsai et al., 2006). Soto et al. (2011) proposed that emotional expression may draw unwanted attention to individuals that value collectivism – which varies across racial and ethnic groups (Green et al., 2005), disrupting group harmony/cohesion. In turn, these individuals may be more likley to utilize more emotion regulation strategies (both putatively adaptive and maldaptive) to modulate their emotional experiences. Evidence also suggests racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation potential. Specifically, non-white (vs. white) and Hispanic (vs. non-Hispanic) individuals exhibit less acceptance of emotions and greater behavioral dyscontrol (e.g., impulsivity) in the context of emotional stimuli (Weiss et al., 2019). Intense emotions may increase risk for disrupting cultural ideologies of conformity, obedience, and in-group harmony (Hofstede, 2001), eliciting negative evaluations and impulsive responding amongst racial and ethnic groups that promote these values. Together, these findings suggest potential racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation strategies and potential.

To advance culturally-informed research on emotion regulation, we systematically reviewed and synthesized prior investigations examining racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation strategies and potential. This systematic review is a critical next step in the existing literature given the application of various definitions of emotion regulation and evidence for mixed findings in past studies of racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation. Findings of this review will further clarify the nature of emotion regulation across racial and ethnic groups.

Methods

Search Strategy

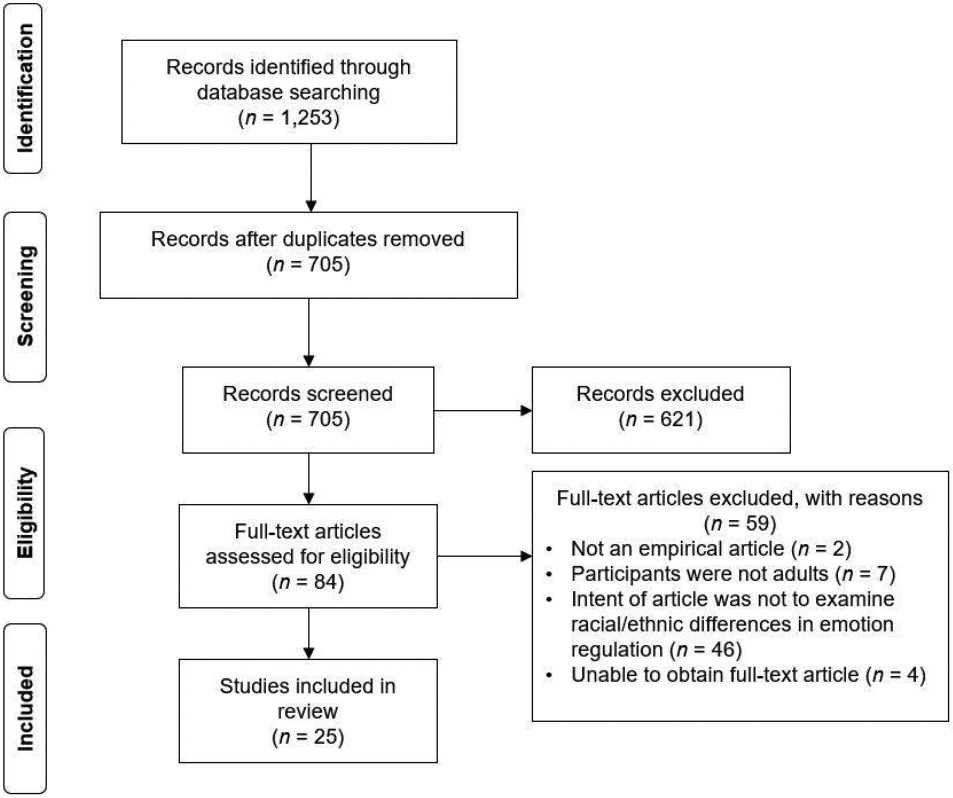

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). The following databases were searched on June 25, 2020: PsycINFO, Embase, MEDLINE, and CINAHL Plus. Search terms included “emotion regulation” OR “emotional regulation” OR “emotion* dysregulation” OR “emotional dysregulation” OR “emotion* dysfunction” “affect* regulation” OR “affective regulation” OR “affect* dysregulation” OR “affective dysregulation” OR “affect dysfunction” OR “affective dysfunction” OR “difficult* regulat*” AND “racial difference*” OR “ethnic* difference*” OR “racial/ethnic difference*” OR “race” OR “racial” OR “ethnic” OR “ethnicity”. All papers generated using these search criteria were compiled by one author into an Endnote database, and duplicate articles were removed. Abstracts were screened by two independent undergraduate student reviewers from the initial search to assess inclusion criteria. Discrepancies in coding were reviewed by a third doctoral student independent reviewer; final inclusionary determinations were made. The search strategy is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram

Article Selection Criteria

Articles were selected for this systematic review based on four pre-determined criteria: 1) reporting in English language, 2) empirical study, 3) paper reported on racial or ethnic differences in emotion regulation, and (4) sample comprised adults aged 18 and over.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The remaining full-length articles were reviewed and information relevant to study goals was then extracted and compiled into tables (see Tables 1 and 2). Information was pulled from each article regarding: 1) sample demographics (age, sex), 2) study characteristics (sample size, recruitment setting, location), 3) type of emotion regulation (strategy vs. potential model), 4) racial/ethnic group(s) of focus, 5) measure used to assess emotion regulation, 6) study design and analytic strategy, and 7) findings on racial/ethnic differences in emotion regulation.

Table 1.

Summary of Demographics of Final Studies

| Sample Size | Setting | Subgroup (When Applicable): Age | Female Sex | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arens, Balkir, & Barnow (2011) | ||||

| 108 | Community | Healthy Turkish: M=43.6 (SD=9.6) Healthy German: M=43.8 (SD=11.2) Depressed Turkish: M=44.4 (SD=8.1) Depressed German: M=43.4 (SD=10.7) |

100% | Germany |

| Berzenski & Yates (2010) | ||||

| 2,169 | University | Dating: M=19.22 (SD=1.64) Non-dating: M=19.06 (SD=1.35) |

63.8% | U.S. |

| Brownlow, Williams, Wiley, Sollers III, Koenig, & Thayer (2018) | ||||

| 469 | University | NA | NA | U.S. |

| Butler, Lee, & Gross (2007) | ||||

| 166 | University | M=20.2 (SD=1.9) | 100% | U.S. |

| Consedine, Chentsova-Dutton, & Krivoshekova (2014) | ||||

| 1364 | Community | English Caribbean: M=58.4 (SD=7.0) Haitian: M=60.4 (SD=6.5) Dominican: M=58.2 (SD=6.1) Eastern European: M=60.8 (SD=6.1) U.S.: M=59.1 (SD=6.31) |

100% | U.S. |

| Consedine, Magai & Horton (2005) | ||||

| 1,361 | Community | African American: M=58.9 (SD=6.2) English Caribbean: M=58.4 (SD=7.0) Haitian: M=60.4 (SD=6.5) Dominican: M=58.2 (SD=6.1) Eastern European: M=60.8 (SD=6.1) European American: M=59.4 (SD=6.5) |

100% | U.S. |

| Consedine, Magai, Horton, & Brown (2012) | ||||

| 1,364 | Community | African American: M=58.9 (SD=6.2) English Caribbean: M=58.4 (SD=7.0) Haitian: M=60.4 (SD=6.5) Dominican: M=58.2 (SD=6.1) Eastern European: M=60.8 (SD=6.1) European American: M=59.4 (SD=6.5) |

100% | U.S. |

| Fancourt, Garnett, & Müllensiefen (2020) | ||||

| 22,563 | Community | M=47.0 (SD=14.3) | 55% | United Kingdom |

| Gross & John (2003) | ||||

| Sample 1: 791 Sample 2: 336 | University | M=20 | Sample 1: 67% Sample 2: 63% |

U.S. |

| Gross, Richards, & John (2006) | ||||

| 500 | University | NA | 61% | U.S. |

| Haliczer, Dixon-Gordon, Law, Anestis, Rosenthal, & Chapman (2019) | ||||

| Sample 1: 194 Sample 2: 88 |

University Community | Sample 1: M=20.61 (SD=4.59) Sample 2: M=31.00 (SD=10.95) |

Sample 1: 77% Sample 2: 84% |

U.S. Canada |

| Harel & Finzi-Dottan (2018) | ||||

| 213 | Welfare Dept | 29.1% aged 20–30 49.8% aged 30–40 18.3% aged 40–50 2.8% aged 50–60 |

83% | Israel |

| Kalibatseva & Leong (2018) | ||||

| 519 | University | Chinese American: M=20.65 (SD=2.95) European American: M=19.87 (SD=2.88) | 64% | U.S. |

| Kalibetseva (2016) | ||||

| 521 | University | Chinese American: M=20.64 (SD=2.94) European American: M=19.87 (SD=2.86) | 64% | U.S. |

| Kaplan (2004) | ||||

| 103 | Family Planning Clinic | M=37.41 (SD=7.13) | 100% | U.S. |

| Lü & Wang (2012) | ||||

| 370 | University | NA | 48% | China |

| Melka, Lancaster, Bryant, & Rodriguez (2011) | ||||

| 1,188 | University | M=19.2 (SD=2.7) | 55% | U.S. |

| Morelen, Jacob, Suveg, Jones, & Thomassin (2013) | ||||

| 168 | University | M=19.49 (SD=1.31) | 57% | U.S. |

| Newhill, Eack, & Conner (2009) | ||||

| 100 | University Hospital | M=36.39 (SD=8.72) | 86% | U.S. |

| O'Neill & Rudenstine (2019) | ||||

| 177 | Outpatient Clinic | M=28.54 (SD=8.41) | 67% | U.S. |

| Perez & Soto (2011) | ||||

| 287 | University | Latino-American: M=18.94 (SD=1.03) Puerto Rican: M=20.53 (SD=2.36) | 56% | U.S. |

| Qu & Telzer (2017) | ||||

| 29 | University | American: M=19.02 Chinese: M=19.38 | 100% | U.S. |

| Schick, Weiss, Contractor, Thomas, & Spillane (2020) | ||||

| 373 | MTurk | M=35.74 (SD=11.10) | 57% | U.S. |

| Stupar, van de Vijver, & Fontaine (2015) | ||||

| 1195 | Centerdata | Dutch majority: M=49 (SD=1.52) Turkish/Moroccan Dutch: M=37 (SD=1.22) Antillean/Surinamese Dutch: M=43 (SD=1.44) Indonesian Dutch: M=53 (SD=1.32) Other Western immigrants: M=51 (SD=1.57) Other non-Western immigrants: M=40 (SD=1.56) |

55% | Netherlands |

| Su et al. (2015) | ||||

| 339 | University | M=19.40 (SD=1.34) | 64% | U.S. |

Table 2.

Summary of Findings of Final Studies

| Emotion Regulation Measure |

Racial/Ethnic Groups | Design | Analytic Strategy |

Findings on Racial/Ethnic Differences in Emotion Regulation Constructs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Regulation Strategies | ||||

| Arens, Balkir, & Barnow (2011) | ||||

| German (Abler & Kessler, 2009) and Turkish (Yurtsever, 2004) versions of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire | 52.78% Turkish 47.22% German |

Cross-sectional | T-test | Healthy Turkish women reported higher levels of suppression but not cognitive reappraisal than Healthy German women. No significant differences in the use of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal were found across depressed Turkish and German women. |

| Butler, Lee, & Gross (2007) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | 38% Asian American 45.2% European American 12.0% Other |

Cross-sectional | T-test | No significant differences on expressive suppression reported between Asian and European Americans. |

| Consedine, Chentsova-Dutton, & Krivoshekova (2014) | ||||

| Present Personality Questionnaire (Consedine et al., 2002) | 21.92% English Caribbean 22.36% Haitian 11.73% Dominican 11.07% Eastern European 32.92% U.S. |

Cross-sectional | MANCOVA | The non-U.S. group had significantly higher emotional expressivity and emotion inhibition than the U.S. group. Among the non-U.S. group, (a) English Caribbean and Haitian women had less emotional expressivity than Dominican and Eastern European women; (b) English Caribbean women had more emotional expressivity than the Haitian women; and (c) Eastern European women had more emotion inhibition than all other non-U.S. subgroups. |

| Consedine, Magai & Horton (2005) | ||||

| Present Personality Questionnaire (Consedine et al., 2002) | 21.60% African American 21.97% English Caribbean 22.34% Haitian 11.68% Dominican 11.09% Eastern European 11.32% European American |

Cross-sectional | MANCOVA | No significant racial/ethnic differences on emotion inhibition. |

| Consedine, Magai, Horton, & Brown (2012) | ||||

| The Index of Self-Regulation of Emotion (Mendolia, 2002) | 21.63% African American 21.92% English Caribbean 22.36% Haitian 11.73% Dominican 11.07 % Eastern European 11.29% European American |

Cross-sectional | MANCOVA | Eastern European women were less emotionally repressive than other groups, followed by U.S.-born European American women. African American women were less emotionally repressive than English Caribbean, Dominican, and Haitian women. |

| Fancourt, Garnett, & Müllensiefen (2020) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Strategies for Artistic Creative Activities Scale (Fancourt et al., 2019) | 91.4% white 8.6% Non-white 7.0% Black 2.6% Southeast Asian 0.6% East Asian 1.4% Multiracial 3.3% Other |

Cross-sectional | SEM | White individuals vs. other racial/ethnic groups reported less use of emotion regulation strategies generally and approach and self-development strategies specifically; no differences were found for avoidance. |

| Gross & John (2003) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | Study 1: 5% African American 41% Asian American 28% European American 9% Latino Study 2: 4% African American 40% Asian American 33% European American 16% Latino |

Cross-sectional | ANOVA | European Americans showed the least use of expressive suppression compared to other racial/ethnic groups across two samples. The three non-white racial/ethnic groups did not differ from each other in expressive suppression across the two studies. There were no racial/ethnic differences in cognitive reappraisal across the two studies. |

| Gross, Richards, & John (2006) | ||||

| Items assessing frequency of emotion regulation each week (Gross et al., 2006) | 35% Asian American 39% European Americans |

Cross-sectional | T-test | There was no effect of race/ethnicity for overall frequency of emotion regulation. Asian Americans reported greater use of suppression than European Americans for positive emotions. Specifically, Asian Americans reported significantly greater control of love, joy, surprise, and amusement, but not pride. There were no ethnic differences in suppression of negative emotions (i.e., sadness, anger, embarrassment, anxiety fear, shame, contempt, guilt, and disgust). |

| Harel & Finzi-Dottan (2018) | ||||

| Emotional Control Questionnaire (Roger & Najarian, 1989) | 47.40% Jewish 52.60% Arabic |

Cross-sectional | ANOVA | Jewish individuals had higher levels of emotional control compared to Arabic individuals. |

| Kalibatseva & Leong (2018) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | 39.3% Chinese American 60.7% European American |

Cross-sectional | T-test | The Chinese American sample endorsed higher (marginally significant) levels of expressive suppression than the European American sample. The Chinese American sample and the European American sample did not differ on cognitive reappraisal. |

| Kalibetseva (2016) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | 39.3% Chinese American 60.7% European American |

Cross-sectional | T-test | No significant ethnic/racial differences in cognitive reappraisal or expressive suppression were detected. |

| Lü & Wang (2012) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Huang & Guo, 2001) | 15% Hui 14% Uighur 14% Mongolia 17% Tibetan 40% Han |

Cross-sectional | MANOVA | Han college students reported higher levels of denial, inhibition, attention, amplification than Tibetan, Hui, Uighur, and Mongolian college students. |

| Melka, Lancaster, Bryant, & Rodriguez (2011) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | 28.9% African American 60.8% European American |

Cross-sectional | T-test | No statistically significant differences were observed between African American and European Americans on expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. |

| Perez & Soto (2011) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | 12.20% Latino-American 87.80% Puerto Rican |

Cross-sectional | T-test | There were no significant differences between Latino Americans and Puerto Ricans on cognitive reappraisal. |

| Qu & Telzer (2017) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | 48% American 52% Chinese |

Cross-sectional | T-test | Chinese participants reported greater use of cognitive reappraisal in daily life than did American participants. Chinese participants reported the same level of expressive suppression in daily life as American participants. |

| Stupar, van de Vijver, & Fontaine (2015) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | 32.55% Dutch majority 11.38% Turkish/Moroccan-Dutch 8.79% Antillean/Surinamese Dutch 8.54% Indonesian Dutch 26.19% Western immigrants 12.55% Non-Western immigrants |

Cross-sectional | MANCOVA | Turkish and Moroccan members scored significantly higher on cognitive reappraisal than the Dutch, Indonesians, and Western immigrants. Dutch majority scored significantly lower on expressive suppression compared to Turkish and Moroccan immigrants. |

| Su et al. (2015) | ||||

| Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, 2003) | 56.93% Chinese Americans 43.07% Mexican Americans |

Cross-sectional | Regression | Chinese Americans reported greater suppression of positive emotions than Mexican Americans. Chinese Americans and Mexican Americans did not differ in the extent to which they suppressed negative emotions. |

| Emotion Regulation Potential | ||||

| Berzenski & Yates (2010) | ||||

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) | 46.2% Asian 27.1% Hispanic 16.7% white MANOVA |

Cross-sectional | MANOVA | Whites reported fewer difficulties with emotional awareness than Hispanics and Asians. Asians reported more emotion-driven impulsivity than Hispanics and whites. |

| Brownlow, Williams, Wiley, Sollers III, Koenig, & Thayer (2018) | ||||

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) | 78.7% European American 21.3% African American |

Cross-sectional | T-test | African Americans did not significantly differ from European Americans on overall emotion regulation potential. |

| Haliczer, Dixon-Gordon, Law, Anestis, Rosenthal, & Chapman (2019) | ||||

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale Gratz & Roemer, 2004) | Sample 1: 50.52% white 21.65% Black 27.83% East Asian Sample 2: 71.59% white 11.36% Black 17.05% East Asian |

Cross-sectional | ANOVA | Sample 1: The Black group reported significantly fewer difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior than the East Asian and white groups. No other differences emerged. Sample 2: Black and East Asian groups reported significantly less emotional nonacceptance than the white group. No other differences emerged. |

| Kaplan (2004) | ||||

| Toronto Alexithymia Scale (Taylor et al., 2003) | 73.8% African American 21.4% Hispanic |

Cross-sectional | ANOVA | There were no significant differences in emotional awareness or differentiation across race/ethnicity. |

| Morelen, Jacob, Suveg, Jones, & Thomassin (2013) | ||||

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) | 36.31% white 30.36% Black 33.33% Asian |

Cross-sectional | MANOVA | Asian participants reported experiencing more deficits in overall emotion regulation potential than white and Black participants. Asian participants reported less emotional acceptance than white and Black participants, more interference with their goals than white and Black participants, and less implementation of effective emotion regulation strategies than Black participants. There were no significant differences between white and Black participants on emotion regulation potential (overall scale or subscales). |

| Newhill, Eack, & Conner (2009) | ||||

| General Emotional Dysregulation Measure (Newhill et al., 2004) | 17% African American 27% white |

Cross-sectional | ANCOVA | African Americans reported higher levels of emotional dysregulation compared to white Americans. |

| O'Neill & Rudenstine (2019) | ||||

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, 2004) | 41.5% white 18.2% Black 9.1% Asian 31.3% Other |

Cross-sectional | T-test | No differences in emotion regulation potential were observed as function of race. |

| Schick, Weiss, Contractor, Thomas, & Spillane (2020) | ||||

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – Positive (Weiss, Gratz, et al., 2015) | 75.9% white 12.3% Hispani 10.5% Black 11% Asian 5.1% American Indian/Alaska Native 0.5% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

Cross-sectional | T-test | Hispanic individuals endorsed greater deficits in overall positive emotion regulation potential than non-Hispanic individuals. Non-white individuals endorsed greater deficits in overall positive emotion regulation potential than vs. white individuals. |

Results

Search Results

The search strategy yielded 1,253 articles. After removing duplicates, the search resulted in 705 articles. After the initial title and abstract review, 621 were excluded. Following the procedures outlined above, the remaining 84 full-text articles were reviewed. Of those, 59 were excluded (see Figure 1 for reasons for exclusions). Thus, the final 25 were subsequently examined, and relevant information pertaining to study goals was extracted.

Sample Demographics and Study Characteristics

Sample demographics and study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The 25 included studies represented 37,055 participants, 62.3% of whom were female.1 Sample sizes ranged from 29 (Qu & Telzer, 2017) to 22,563 (Fancourt et al., 2020), and the mean ages of participants ranged from 18.94 (Perez & Soto, 2011) to 60.8 (Consedine et al., 2012), while four studies did not report mean age (Brownlow et al., 2018; Gross et al., 2006; Harel & Finzi-Dottan, 2018; Lü & Wang, 2012). Regarding sex, seven articles (28.0%) had an all-female sample, and no articles had an all-male sample. The most common recruitment setting was within universities (n = 14, 56.0%; Berzenski & Yates, 2010; Brownlow et al., 2018; Butler et al., 2007; Gross & John, 2003; Gross et al., 2006; Haliczer et al., 2019; Kalibatseva, 2015; Kalibatseva & Leong, 2018; Lü & Wang, 2012; Melka et al., 2011; Morelen et al., 2013; Perez & Soto, 2011; Qu & Telzer, 2017; Su et al., 2015), followed by community samples (n = 7, 28.0%; Arens et al., 2013; Caplan, 1992; Consedine et al., 2014; Consedine et al., 2005; Consedine et al., 2012; Fancourt et al., 2020; Haliczer et al., 2019) and medical offices/facilities (n = 3, 12.0%; Kaplan, 2004; Newhill et al., 2009; O'Neill & Rudenstine, 2019). One study each used data collected from MTurk (Schick et al., 2020), Centerdata (Stupar et al., 2015), and a Welfare Department (Harel & Finzi-Dottan, 2018). The majority of the studies took place in the United States (n = 20, 80.0%). Other study locations included Puerto Rico (Perez & Soto, 2011), China (Lü & Wang, 2012), Germany (Arens et al., 2013), Israel (Harel & Finzi-Dottan, 2018), the Netherlands (Stupar et al., 2015), Canada (Haliczer et al., 2019), and the United Kingdom (Fancourt et al., 2020). Two studies took place in two countries and reported results separately for each country (U.S. and Canada and U.S. and Puerto Rico; Haliczer et al., 2019; Perez & Soto, 2011).

Methodological Variations

Almost all studies included white/European origin participants (n = 21, 84.0%; Arens et al., 2013; Berzenski & Yates, 2010; Brownlow et al., 2018; Butler et al., 2007; Caplan, 1992; Consedine et al., 2014; Consedine et al., 2005; Consedine et al., 2012; Fancourt et al., 2020; Gross & John, 2003; Gross et al., 2006; Haliczer et al., 2019; Harel & Finzi-Dottan, 2018; Kalibatseva, 2015; Kalibatseva & Leong, 2018; Melka et al., 2011; Morelen et al., 2013; Newhill et al., 2009; O'Neill & Rudenstine, 2019; Schick et al., 2020; Stupar et al., 2015). One of these studies specifically compared between groups of European origin (Turkish & German; Arens et al., 2013). One study compared individuals who were Jewish and Arabic (Harel & Finzi-Dottan, 2018), and one study compared Dutch majority individuals, individuals who had immigrated to the Netherlands from Western counties, and individuals who had immigrated from non-Western countries (Stupar et al., 2015). More than half of reviewed studies included Black/African origin participants (n = 16, 64.0%; Berzenski & Yates, 2010; Brownlow et al., 2018; Butler et al., 2007; Consedine et al., 2014; Consedine et al., 2005; Consedine et al., 2012; Fancourt et al., 2020; Gross & John, 2003; Gross et al., 2006; Haliczer et al., 2019; Kaplan, 2004; Melka et al., 2011; Morelen et al., 2013; Newhill et al., 2009; O'Neill & Rudenstine, 2019; Schick et al., 2020). Of these, three studies examined differences between Caribbean groups (English Caribbean, Haitian, and Dominican; Consedine et al., 2014; Consedine et al., 2005; Consedine et al., 2012). Fourteen studies included participants of Asian descent (56.0%; Berzenski & Yates, 2010; Butler et al., 2007; Fancourt et al., 2020; Gross & John, 2003; Gross et al., 2006; Haliczer et al., 2019; Kalibatseva, 2015; Kalibatseva & Leong, 2018; Lü & Wang, 2012; Morelen et al., 2013; O’Neill & Rudenstine, 2019; Qu & Telzer, 2017; Schick et al., 2020; Su et al., 2015). One of these studies compared among specific groups of Asian descent (Han, Hui, Uighur, Mongolian, and Tibetan; Lü & Wang, 2012). Another compared between individuals from China and from the U.S. (Qu & Telzer, 2017). Eight articles included Hispanic/Latinx participants (32.0%; Berzenski & Yates, 2010; Butler et al., 2007; Caplan, 1992; Gross & John, 2003; Gross et al., 2006; Kaplan, 2004; Schick et al., 2020; Su et al., 2015). One of these studies specifically compared between individuals from Puerto Rico and Latino-American individuals (Perez & Soto, 2011). One study each included American Indian/Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (Schick et al., 2020) and bi-racial/multiracial (O'Neill & Rudenstine, 2019) participants.

Most studies included measures assessing the use of emotion regulation strategies, with the most commonly used measure being the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (n = 10, 40.0%; Arens et al., 2013; Butler et al., 2007; Gross & John, 2003; Kalibatseva, 2015; Kalibatseva & Leong, 2018; Melka et al., 2011; Perez & Soto, 2011; Qu & Telzer, 2017; Stupar et al., 2015; Su et al., 2015). Of these studies, one used translated versions of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, specifically German and Turkish (Perez & Soto, 2011). Other measures used to assess the use of emotion regulation strategies were the Present Personality Questionnaire (n = 2; Consedine et al., 2014; Consedine et al., 2005), the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (n = 1; Lü & Wang, 2012; different from the Gross and John [2003] measure), the Emotion Regulation Strategies for Artistic Creative Activities Scale (n = 1; Fancourt et al., 2020), the Index of Self-Regulation of Emotion (n = 1; Consedine et al., 2012), and the Emotional Control Questionnaire (n = 1; Harel & Finzi-Dottan, 2018). Eight studies included measures assessing emotion regulation potential, including the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (n = 5; Berzenski & Yates, 2010; Brownlow et al., 2018; Haliczer et al., 2019; Morelen et al., 2013; O'Neill & Rudenstine, 2019), the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – Positive (n = 1; Schick et al., 2020), the Emotional Dysregulation Measure (n = 1; Newhill et al., 2009), and the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (n = 1; Kaplan, 2004).

All studies included in the present review made use of a cross-sectional design. With respect to analytic strategy, the most commonly used approach was an independent sample t-test (n = 11, 44.0%; Arens et al., 2013; Brownlow et al., 2018; Butler et al., 2007; Gross et al., 2006; Kalibatseva, 2015; Kalibatseva & Leong, 2018; Melka et al., 2011; O'Neill & Rudenstine, 2019; Perez & Soto, 2011; Qu & Telzer, 2017; Schick et al., 2020). Other analytic approaches used were multivariate analysis of variance/covariance (MANOVA/MANCOVA, n = 7, 28.0%; Berzenski & Yates, 2010; Consedine et al., 2014; Consedine et al., 2005; Consedine et al., 2012; Lü & Wang, 2012; Morelen et al., 2013; Stupar et al., 2015), analysis of variance/ covariance (ANOVA/ANCOVA, n = 5, 20.0%; Gross & John, 2003; Haliczer et al., 2019; Harel & Finzi-Dottan, 2018; Kaplan, 2004; Newhill et al., 2009), structural equation modeling (n = 1, 4.0%; Fancourt et al., 2020), and regression (n = 1, 4.0%; Su et al., 2015).

Racial/Ethnic Differences in Emotion Regulation Strategies

Of the 17 studies which examined racial/ethnic differences in the use of emotion regulation strategies, 12 studies (70.6%) found significant racial and ethnic differences.

Twelve studies (76.5%) included samples within the U.S. In one study conducted in the U.S., Asian individuals endorsed significantly greater suppression (putatively maladaptive) of negative emotions compared to White individuals (Kalibatseva & Leong, 2018) and positive emotions compared to Hispanic and White individuals (Gross et al., 2006; Su et al., 2015). On the other hand, Qu and Telzer (2017) found that Chinese-born participants in the U.S. reported using suppression (putatively maladaptive) to the same degree as U.S.-born participants of European origin but reported greater use of cognitive reappraisal (putatively adaptive). One study found White individuals to report the lowest use of suppression (putatively maladaptive) compared to Asian, Black, and Hispanic individuals in the U.S. (Gross & John, 2003). Another study found that individuals of Eastern European origin in the U.S. engaged in the greatest attempts to inhibit their emotions (putatively maladaptive) compared to Haitian, Dominican, English Caribbean, and U.S. born individuals (Consedine et al., 2014). Conversely, Consedine et al. (2012) found Eastern European and U.S.-born women to use emotional suppression (putatively maladaptive) less than African American women, who in turn used emotional suppression (putatively maladaptive) less than English Caribbean, Dominican, and Haitian women. In summary, among the 12 U.S.-based studies on emotion regulation strategies, seven studies (58.3%) found evidence of racial and ethnic differences.

In terms of the five studies conducted outside the U.S., one found that White individuals used fewer putatively adaptive emotion regulation strategies (general strategies and approach and self-development strategies specifically) compared to non-White (i.e., Black, Asian, “mixed race,” and “other race”) individuals (Fancourt et al., 2020). In another study, Turkish individuals reported higher levels of emotional suppression (putatively maladaptive) compared to German individuals (Arens et al., 2013). Another third study found Jewish individuals to report higher levels of emotional control (putatively adaptive) compared to Arabic individuals (Harel & Finzi-Dottan, 2018). Another study found Dutch individuals to report the lowest use of suppression (putatively maladaptive) compared to individuals of Turkish and Moroccan descent in the Netherlands (Stupar et al., 2015). A final study found Han individuals to report the highest levels of emotion regulation strategies (cognitive appraisal – putatively adaptive – in particular) compared to Tibetan, Hui, Uighur, and Mongolian individuals (Lü & Wang, 2012). In summary, among the five studies conducted outside the U.S. on emotion regulation strategies, all found evidence of racial and ethnic differences.

Racial/Ethnic Differences in Emotion Regulation Potential

Of the eight studies that included a measure of emotion regulation potential, five found significant differences across racial and ethnic groups (62.5%). With respect to overall emotion regulation skills, one study in the U.S. found non-White and Hispanic individuals to report greater difficulties regulating positive emotions (putatively maladaptive) compared to White and non-Hispanic individuals, respectively (Schick et al., 2020), and two studies in the U.S. found Asian individuals to have significantly more difficulties regulating their emotions (putatively maladaptive) compared to other racial and ethnic groups (Berzenski & Yates, 2010; Morelen et al., 2013). One study found that Black individuals reported higher levels of overall emotion dysregulation (putatively maladaptive) compared to White individuals (Newhill et al., 2009). When examining specific emotion regulation skills, one study in the U.S. found that Black individuals reported significantly fewer difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior in the context of intense emotions (putatively maladaptive) compared to East Asian and White individuals, and that White individuals reported significantly more non-acceptance of emotions (putatively maladaptive) compared to Black and East Asian individuals (Haliczer et al., 2019). On the other hand, however, another study in the U.S. found that Asian individuals reported greater non-acceptance of their emotions (putatively maladaptive) and greater difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior in the context of intense emotions (putatively maladaptive) compared to White and Black individuals (Morelen et al., 2013). One study in the U.S. found White individuals to report greater emotional awareness (putatively adaptive) compared to Hispanic and Asian individuals, whereas Asian individuals reported greater difficulties controlling impulsive behavior in the context of emotions (putatively maladaptive) compared to Hispanic and White individuals (Berzenski & Yates, 2010). Finally, one study in the U.S. found that Asian participants reported less use of strategies to regulate their emotions (putatively maladaptive) compared to Black participants (Morelen et al., 2013). Of note, all articles focusing on emotion regulation potential were conducted within the U.S.2

Discussion

In the present systematic review, we synthesized research examining racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation strategies (i.e., specific tactics that individuals use to influence the experience and expression of emotions) and potential (i.e., the dispositional ways in which individuals understand, regard, and respond to their emotional experience). Of note, the majority of studies reviewed were conducted in the U.S. and involved comparison of white individuals to non-white racial and ethnic group(s). As such, we subsequently refer to ethnoracial minorities, which broadly captures non-white racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. Findings for emotion regulation strategies generally provide evidence for racial and ethnic differences (71% of studies), with ethnoracial minority individuals largely being found to exhibit greater use of emotion regulation strategies, primarily suppression of emotional experiences. Whereas the results for emotion regulation potential were more mixed (63% of studies found racial/ethnic differences), ethnoracial minority individuals were also largely found to report lower levels of emotion regulation potential. In sum, findings provided additional support for racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation and underscore key avenues for future research.

Before discussing the primary study findings, it should be noted that there were considerable differences in sample and study characteristics. Most notably, there was variation in the type and number of racial and ethnic groups examined across studies reviewed here. As a result, caution should be taken in making generalizations about levels of emotion regulation across specific racial and ethnic groups. For instance, although usually classified as single racial and ethnic groups by researchers, there is significant within-group variability among individuals from different racial and ethnic groups (e.g., Asians); they represent various national origins that each have their own culture. Given the influence of culture on emotion (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, 1998; Matsumoto, 2006; Schwartz & Bardi, 2001), perhaps emotion regulation may vary not only as a function of race and ethnicity, but more specifically national origin. In this respect, future research would benefit from identification of specific cultural factors (e.g., ethnic identity, acculturation, values adherence) that may help to explain racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation (Helms et al., 2005). Indeed, cultural values of collectivism and individualism have been tied to emotion regulation strategy implementation, with individualist cultures preferring expression of emotions and collectivistic cultures being more likely to apply emotional suppression (Ramzan & Amjad, 2017). These caveats may explain the mixed results of the current review which limit definitive conclusions. Specifically, whereas the majority of studies found more emotion regulation strategies and lower emotion regulation potential among ethnoracial minorities, others reported more emotion regulation strategies and lower emotion regulation potential among whites, and still others found no significant racial/ethnic differences in emotion regulation.

With these considerations in mind, findings from the current review primarily indicate greater use of emotion regulation strategies and lower levels of emotion regulation potential among ethnoracial minorities. These results align with the premise that ethnoracial minorities may be motivated to dampen emotional experiences and expression. To elaborate, specific cultural norms for emotional experiences and expression vary across racial and ethnic groups (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Roseman et al., 1995). These cultural norms impact the extent to which different racial and ethnic groups encourage and reinforce emotional responding (Butler et al., 2007). In this regard, cultural worldviews, ideologies, values, and self-concept influence how members of different racial and ethnic groups appraise emotional stimuli (Markus & Kitayama, 1991, 1998; Matsumoto, 2006; Schwartz & Bardi, 2001), including whether emotional experiences are viewed as undesirable (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Roseman et al., 1995), uncontrollable, and unpredictable (De Leersnyder et al., 2013). Ethnoracial minorities often prioritize the goals and needs of the group as a whole (Vargas & Kemmelmeier, 2013); thus, these individuals may prefer to down-regulate emotional experiences to maintain in-group harmony (Hofstede, 2001). Such down-regulation of emotional experiences may be reflected in the degree to which emotion regulation strategies are utilized as well as the types of emotion regulation potential that are experienced. Emotion regulation strategies serve to modulate the intensity and/or duration of emotional experiences, thus higher levels reflect more attempts to dampen emotions. Emotion regulation potential is also tied to the down-regulation of emotions, such as acceptance of emotions (i.e., emotional nonacceptance may lead to more attempts to down-regulate emotional experiences) and emotional urgency (i.e., impulsive responding may serve to dampen aversive emotional experiences). Alternatively, it is possible that greater use of emotion regulation strategies and lower levels of emotion regulation potential among ethnoracial minorities may be explained by some other third variables, such as lower socioeconomic status or greater number/severity of life stressors. Future research is needed to test these hypotheses.

One important question that remains unanswered in this systematic review relates to the potentially divergent consequences of emotion regulation strategies and potential across racial and ethnic groups. Existing literature refers to emotion regulation strategies as “adaptive” versus “maladaptive” based on general patterns of associations with health outcomes (for a review, see Aldao et al., 2010). However, there has been growing attention to the influence of context in the consequences of emotion regulation strategies (Aldao, 2013; Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012), with these studies documenting the potential for maladaptive outcomes for “adaptive” strategies and adaptive outcomes for “maladaptive” strategies. In the current study, we found evidence that ethnoracial minorities may be more likely to use both adaptive (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) and maladaptive (e.g., expressive suppression) emotion regulation strategies. While there is some evidence that greater use of both adaptive and maladaptive strategies is related to poorer health outcomes among predominantly white individuals in the U.S. (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015), more use of emotion regulation strategies among ethnoracial minorities may reflect cultural norms related to emotional expression. For example, the value of interdependence among many ethnoracial minorities might encourage emotional suppression for prosocial reasons (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In line with this hypothesis, Butler et al. (2007) found that while Americans adhering to Asian values reported more expressive suppression than those adhering to Western European values, expressive suppression was related to fewer negative social outcomes for Americans adhering to Asian vs. Western European values. The authors purported that expressive suppression may fulfill a broader range of social functions for individuals adhering to Asian values and thus may be less associated with negative emotion in Asian vs. Western European cultures. Similarly, another study in the U.S. found emotion regulation potential related to alcohol use for white women but not Black or Hispanic women (Weiss et al., in press); it was suggested that Black, Hispanic, and white individuals might be socialized to differentially respond to emotions to minimize risk for threat related to emotional expressions including race-related discrimination (e.g., anger). Notably, while differences in aspects of emotion regulation may function to maintain in-group harmony or cohesion (Hofstede, 2001), it is possible that they may serve to a detriment on the individual level, especially among individuals who are residing in individualist cultures like the U.S. Research that clarifies the health consequences of emotion regulation among different racial and ethnic groups at both the individual and group levels is warranted.

Some limitations require consideration when interpreting the findings of the current review. First, most studies reviewed were conducted in the U.S., thus emotion regulation among racial and ethnic groups that are not well-represented inside the U.S. or among examined racial and ethnic groups in contexts outside the U.S. remains unclear. Second, most reviewed studies involved comparison of white individuals to non-white racial and ethnic group(s) as opposed to other racial and ethnic groups. Third, none of the reviewed articles included data on sexual orientation and only seven reported on education and socioeconomic status, thus we were not able to examine the role of intersecting identities on emotion regulation. Fourth, despite the breadth of our search terms, we did not identify studies focused on racial and ethnic differences in all available emotion regulation measures, including alternative/complementary models (e.g., Berking & Schwarz, 2014; Garnefsky & Kraaij, 2007) to those featured here (i.e., Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Gross, 2015). Lastly, all of the reviewed studies utilized cross-sectional designs, preventing causal determination of the relations examined.

Despite these limitations, the current systematic review advances the literature by highlighting racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation. Our findings suggest the need for additional research on the relation of race and ethnicity to emotion regulation. For instance, as cultural worldviews, ideologies, values, and concepts (along with acculturation and enculturation patterns) may vary among racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. compared to other geographical locations (e.g., Asian Americans versus Asian individuals; Yasuda & Duan, 2002), further research examining differences in emotion regulation among racial and ethnic groups needs to be conducted using international samples. Additionally, research on emotion regulation is needed to compare non-white racial and ethnic groups to one another as well as to better understand racial and ethnic differences across national contexts. Further, there has been increased consideration in psychology to intersectionality in the past decade (Clauss-Ehlers et al., 2019). Intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1990) purports that identities intersect (e.g., race/ethnicity and gender) to create unique experiences; this may include expectations about emotional experiencing and responding. As such, investigations that consider the impact of intersectional identities is warranted. Notably, in order for investigators to fully evaluate the role of intersecting identities on emotion regulation, it is recommended that empirical studies in this area assess/report on these (and other) important aspects of one’s identity. Moreover, research on racial and ethnic differences in emotion regulation using measures that capture other models of emotion regulation (e.g., Berking & Schwarz, 2014; Garnefsky & Kraaij, 2007) is needed. Lastly, future research is needed to investigate the nature and direction of these relations through prospective, longitudinal investigations.

Research that addresses these questions will inform culturally-tailored interventions aimed at improving emotion regulation. For instance, if subsequent evidence confirms that putatively maladaptive emotion regulation strategies are associated with positive outcomes for individuals from some racial and ethnic groups (e.g., expressive suppression for Asian individuals because it aligns with cultural norms of group harmony), emotion regulation treatments will need to be adapted to align with racial and ethnic cultural worldviews, ideologies, values, and self-concepts or else run the risk of advocating for behaviors that are culturally incongruent and thus potentially deleterious to specific individuals. This is an important avenue for future scientific inquiry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant K23 DA039327, awarded to the first author (NHW). NHW also acknowledges the support from the Center for Biomedical Research and Excellence (COBRE) on Opioids and Overdose funded by the National Institute on General Medical Sciences (P20 GM125507).

Footnotes

Of note, the percentage of female participants was calculated based on 24 studies that reported the sex breakdown of their participants.

See Supplemental Table 1 for a summary of results across the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire and the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – the most commonly used emotion regulation measures in the studies reviewed here.

References

- Abler B, & Kessler H (2009). Emotion regulation questionnaire–Eine deutschsprachige Fassung des ERQ von Gross und John. Diagnostica, 55, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A (2013). The future of emotion regulation research capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, & Nolen-Hoeksema S (2012). The influence of context on the implementation of adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Behavior Research and Therapy, 50, 493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schweizer S (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arens EA, Balkir N, & Barnow S (2013). Ethnic variation in emotion regulation: Do cultural differences end where psychopathology begins? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 335–351. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby RM, Parker JDA, & Taylor GJ (1994). The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale-I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38, 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzenski SR, & Yates TM (2010). A developmental process analysis of the contribution of childhood emotional abuse to relationship violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 19, 180–203. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlow BN, Williams DP, Wiley CR, Sollers JJ, Koenig J, & Thayer JF (2018). Examining ethnic differences in heart rate variability and differences in emotion regulation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 80, A18–A19. [Google Scholar]

- Butler EA, Lee TL, & Gross JJ (2007). Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion, 7, 30–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler EA, Lee TL, & Gross JJ (2007). Emotion regulation and culture: Are the social consequences of emotion suppression culture-specific? Emotion, 7, 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AL (1992). Twenty years later. The legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. When evil intrudes. The Hastings Center Report, 22, 29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss-Ehlers CS, Chiriboga DA, Hunter SJ, Roysircar G, & Tummala-Narra P (2019). APA Multicultural Guidelines executive summary: Ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. American Psychologist, 74, 232–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cludius B, Mennin D, & Ehring T (2020). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic process. Emotion, 20, 37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Michel MK, & Teti LO (1994). The development of emotion regulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 73–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Chentsova-Dutton YE, & Krivoshekova YS (2014). Emotional acculturation predicts better somatic health: Experiential and expressive acculturation among immigrant women from four ethnic groups. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33, 867–889. [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Magai C, Cohen CI, & Gillespie M (2002). Ethnic variation in the impact of negative affect and emotion inhibition on the health of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57, P396–P408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Magai C, & Horton D (2005). Ethnic variation in the impact of emotion and emotion regulation on health: A replication and extension. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60, P165–P173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Magai C, Horton D, & Brown WM (2012). The affective paradox: An emotion regulatory account of ethnic differences in self-reported anger. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43, 723–741. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- De Leersnyder J, Boiger M, & Mesquita B (2013). Cultural regulation of emotion: Individual, relational, and structural sources. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Aldao A, & De Los Reyes A (2015). Repertoires of emotion regulation: A person-centered approach to assessing emotion regulation strategies and links to psychopathology. Cognition & Emotion, 29, 1314–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Weiss NH, Tull MT, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore T, & Gratz KL (2015). Characterizing emotional dysfunction in borderline personality, major depression, and their co-occurrence. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 62, 187–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D, Garnett C, & Müllensiefen D (in press). The relationship between demographics, behavioral and experiential engagement factors, and the use of artistic creative activities to regulate emotions. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D, Garnett C, Spiro N, West R, & Müllensiefen D (2019). How do artistic creative activities regulate our emotions? Validation of the Emotion Regulation Strategies for Artistic Creative Activities Scale (ERS-ACA). PloSOone, 14, e0211362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Axelrod SR, Paliwal P, Sleeper J, & Sinha R (2007). Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control during cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 89, 298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong KA, & Sinha R (2008). Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 388–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Chapman AL (2007). The role of emotional responding and childhood maltreatment in the development and maintenance of deliberate self-harm among male undergraduates. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Paulson A, Jakupcak M, & Tull MT (2009). Exploring the relationship between childhood maltreatment and intimate partner abuse: gender differences in the mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Violence & Victims, 24, 68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Rosenthal MZ, Tull MT, Lejuez CW, & Gunderson JG (2006). An experimental investigation of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Tull MT (2010a). Emotion regulation as a mechanism of change in acceptance-and mindfulness-based treatments. In Baer RA (Ed.), Assessing Mindfulness and Acceptance: Illuminating the Theory and Practice of Change (pp. 105–133). New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Tull MT (2010b). The relationship between emotion dysregulation and deliberate self-harm among inpatients with substance use disorders. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 34, 544–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, Baruch DE, Bornovalova MA, & Lejuez CW (2008). Factors associated with co-occurring borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users: The roles of childhood maltreatment, negative affect intensity/reactivity, and emotion dysregulation. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49, 603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Weiss NH, & Tull MT (2015). Examining emotion regulation as an outcome, mechanism, or target of psychological treatments. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green EGT, Deschamps J-C, & Paez D (2005). Variation of individualism and collectivism within and between 20 countries: A typological analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 321–339. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, & John OP (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Richards JM, & John OP (2006). Emotion regulation in everyday life (Vol. 2006). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Haliczer LA, Dixon-Gordon KL, Law KC, Anestis MD, Rosenthal MZ, & Chapman AL (2019). Emotion regulation difficulties and borderline personality disorder: The moderating role of race. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 11, 280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel G, & Finzi-Dottan R (2018). Childhood maltreatment and its effect on parenting among high-risk parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Jernigan M, & Mascher J (2005). The meaning of race in psychology and how to change it: A methodological perspective. American Psychologist, 60, 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G (2001). Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Zhang D, Wang J, Mistry R, Ran G, & Wang X (2014). Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: A meta-analysis review. Psychological Reports, 114, 341–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ME, & Guo DJ (2001). Emotion regulation and its development trend. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 2, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kalibatseva Z (2015). Culture and depression among Asian Americans: Disentangling ethnic differences by examining culturally relevant psychological factors. Michigan State University. [Google Scholar]

- Kalibatseva Z, & Leong FT (2018). Cultural factors, depressive and somatic symptoms among Chinese American and European American college students. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49, 1556–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A (2004). The role of affect regulation as a mediating mechanism between childhood trauma and adolescent and adult substance abuse Adelphi University, The Institute of Advanced Psychological Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, & Haidt J (1999). Social functions of emotions at four levels of analysis. Cognition & Emotion, 13, 505–521. [Google Scholar]

- Koole SL (2009). The psychology of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Cognition and emotion, 23, 4–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, & Anderson DA (2010). Contribution of emotion regulation difficulties to disordered eating and body dissatisfaction in college men. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43, 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, Smith TL, Klein MH, & Goldschmidt AB (2014). Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 22, 212–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü W, & Wang Z (2012). Emotional expressivity, emotion regulation, and mood in college students: A cross-ethnic study. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 40, 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, & Kitayama S (1998). The cultural psychology of personality. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 29, 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D (1993). Ethnic differences in affect intensity, emotion judgments, display rule attitudes, and self-reported emotional expression in an American sample. Motivation and Emotion, 17, 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D (2006). Culture and cultural worldviews: Do verbal descriptions about culture reflect anything other than verbal descriptions of culture? Culture & Psychology, 12, 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Melka SE, Lancaster SL, Bryant AR, & Rodriguez BF (2011). Confirmatory factor and measurement invariance analyses of the emotion regulation questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 1283–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendolia M (2002). An index of self-regulation of emotion and the study of repression in social contexts that threaten or do not threaten self-concept. Emotion, 2, 215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Walsh KL, & DiLillo D (2010). Emotion dysregulation and risky sexual behavior in revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 967–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, & Altman DG (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151, 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelen D, Jacob ML, Suveg C, Jones A, & Thomassin K (2013). Family emotion expressivity, emotion regulation, and the link to psychopathology: Examination across race. British Journal of Psychology, 104, 149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhill CE, Eack SM, & Conner KO (2009). Racial differences between African and White Americans in the presentation of borderline personality disorder. Race and Social Problems, 1, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Newhill CE, Mulvey EP, & Pilkonis PA (2004). Initial development of a measure of emotional dysregulation for individuals with cluster B personality disorders. Research on Social Work Practice, 14, 443–449. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill S, & Rudenstine S (2019). Inattention, emotion dysregulation and impairment among urban, diverse adults seeking psychological treatment. Psychiatry Research, 282, 112631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CR, & Soto JA (2011). Cognitive reappraisal in the context of oppression: Implications for psychological functioning. Emotion, 11, 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Y, & Telzer EH (2017). Cultural differences and similarities in beliefs, practices, and neural mechanisms of emotion regulation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23, 36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramzan N, & Amjad N (2017). Cross cultural variation in emotion regulation: A systematic review. Annals of King Edward Medical University, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer L, Lee JK, Salters-Pedneault K, Erisman SM, Orsillo SM, & Mennin DS (2009). Mindfulness and emotion regulation difficulties in generalized anxiety disorder: Preliminary evidence for independent and overlapping contributions. Behavior Therapy, 40, 142–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger D, & Najarian B (1989). The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring emotion control. Personality and Individual Differences, 10, 845–853. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman IJ, Dhawan N, Rettek SI, Naidu R, & Thapa K (1995). Cultural differences and cross-cultural similarities in appraisals and emotional responses. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schick MR, Weiss NH, Contractor AC, Thomas ED, & Spillane NS (2020). Difficulties regulating positive emotions and substance misuse: The influence of sociodemographic factors. Substance Use & Misuse, 55, 1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH, & Bardi A (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures: Taking a similarities perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 268–290. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Brasfield H, Febres J, & Stuart GL (2011). An examination of the association between difficulties with emotion regulation and dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 20, 870–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto JA, Perez CR, Kim Y-H, Lee EA, & Minnick MR (2011). Is expressive suppression always associated with poorer psychological functioning? A cross-cultural comparison between European Americans and Hong Kong Chinese. Emotion, 11, 1450–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupar S, van de Vijver FJ, & Fontaine JR (2015). Emotion valence, intensity and emotion regulation in immigrants and majority members in the Netherlands. International Journal of Psychology, 50, 312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su JC, Lee RM, Park IJ, Soto JA, Chang J, Zamboanga BL, Kim SY, Ham LS, Dezutter J, & Hurley EA (2015). Differential links between expressive suppression and well-being among Chinese and Mexican American college students. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, & Parker JD (2003). The 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale: IV. Reliability and factorial validity in different languages and cultures. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55, 277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Chentsova-Dutton Y, Freire-Bebeau L, & Przymus DE (2002). Emotional expression and physiology in European Americans and Hmong Americans. Emotion, 2, 380–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Levenson RW, & McCoy K (2006). Cultural and temperamental variation in emotional response. Emotion, 6, 484–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, & Aldao A (2015a). Editorial overview: New directions in the science of emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, & Aldao A (2015b). Emotion regulation [Special issue] Current Opinion in Psychology, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Barrett HM, McMillan ES, & Roemer L (2007). A preliminary investigation of the relationship between emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 38, 303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, & Gratz KL (2008). Further examination of the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and depression: the mediating role of experiential avoidance and difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior when distressed. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Weiss NH, Adams CE, & Gratz KL (2012). The contribution of emotion regulation difficulties to risky sexual behavior within a sample of patients in residential substance abuse treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 1084–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas JH, & Kemmelmeier M (2013). Ethnicity and contemporary American culture: A meta-analytic investigation of horizontal–vertical individualism–collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44, 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ, & Bernstein A (2008). The interactive effects of anxiety sensitivity and emotion dysregulation in predicting anxiety-related cognitive and affective symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 803–817. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Darosh A, Contractor A, Schick MR, & Dixon-Gordon KL (2019). Confirmatory validation of the factor structure and psychometric properties of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale – Positive. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75, 1267–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Gratz KL, & Lavender J (2015). Factor structure and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of difficulties in the regulation of positive emotions: The DERS-Positive. Behavior Modification, 39, 431–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Schick MR, Contractor AA, Reyes ME, Suazo NC, & Sullivan TP (in press). Racial/ethnic differences in alcohol and drug misuse among IPV-victimized women: Exploring the role of difficulties regulating positive emotions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Sullivan TP, & Tull MT (2015). Explicating the role of emotion dysregulation in risky behaviors: A review and synthesis of the literature with directions for future research and clinical practice. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Anestis MD, Gratz KL, Weiss NH, Tull MT, Anestis MD, & Gratz KL (2013). The relative and unique contributions of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity to posttraumatic stress disorder among substance dependent inpatients. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 128, 45–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda T, & Duan C (2002). Ethnic identity, acculturation, and emotional well-being among Asian American and Asian international students. Asian Journal of Counselling, 9, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Yurtsever G (2004). Emotional regulation strategies and negotiation. Psychological Reports, 95, 780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.