Abstract

The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in twin pregnancies is not well-studied. In this retrospective study, we investigated the frequency of chromosomal abnormalities in twin pregnancies and compared the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in dichorionic diamniotic (DD) and monochorionic diamniotic (MD) twins. We used data from 57 clinical facilities across Japan. Twin pregnancies of more than 12 weeks of gestation managed between January 2016 and December 2018 were included in the study. A total of 2899 and 1908 cases of DD and MD twins, respectively, were reported, and the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in one or both fetuses was 0.9% (25/2899) and 0.2% (4/1908) in each group (p = 0.004). In this study, the most common chromosomal abnormality was trisomy 21 (51.7% [15/29]), followed by trisomy 18 (13.8% [4/29]) and trisomy 13 (6.9% [2/29]). The incidence of trisomy 21 in MD twins was lower than that in DD twins (0.05% vs. 0.5%, p = 0.007). Trisomy 21 was less common in MD twins, even when compared with the expected incidence in singletons (0.05% vs. 0.3%, RR 0.15 [95% CI 0.04–0.68]). The risk of chromosomal abnormality decreases in twin pregnancies, especially in MD twins.

Subject terms: Chromosome abnormality, Genetics research

Introduction

The incidence of twin pregnancies, particularly dizygotic pregnancies, which positively correlate with the maternal age and use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), has increased [1]. Twin pregnancies have a higher risk of intrauterine growth retardation, preterm delivery, and neonatal mortality. Many studies have found that twin pregnancies also have a higher risk of congenital anomalies than singleton pregnancies [2–4]. Approximately 25% of congenital anomalies are attributed to chromosomal abnormalities [5], and twin pregnancies have also been considered to have a high risk of chromosomal abnormalities. However, it was reported that the incidence of trisomy 21 was lower in twin than in singleton pregnancies, most notably in monozygotic twins [6], although these findings were not universal. The risk of chromosomal abnormalities in twin pregnancies remains controversial.

This study retrospectively investigated the frequency of chromosomal abnormalities in twin pregnancies in Japan. The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in dichorionic diamniotic (DD) and monochorionic diamniotic (MD) twins were compared using data collected from 57 clinical facilities across Japan. We also compared the observed incidence of trisomy 21 among twin pregnancies with that expected based on maternal age-matched singletons.

Materials and methods

This retrospective observational study used data collected from 57 perinatal centers that handle twin deliveries all over Japan. We asked facilities that handle many deliveries in Japan to participate in this research, and 57 of them cooperated. Cases of twin pregnancies between January 2016 and December 2018, wherein chorionicity was determined using ultrasound examination and that continued beyond 12 weeks of gestation, were included in the study. Cases of spontaneous abortion, artificial stillbirth, and single fetal demise after 12 weeks of gestation were not excluded. Cases of unknown age at the time of ovum collection and cases of ovum donation were excluded because the risk of chromosomal abnormalities in these cases may not be correlated with maternal age. Cases of unknown chorionicity, monochorionic monoamniotic (MM) twins, vanishing twins, and multifetal pregnancy reduction were also excluded. This study was approved by the ethics institutional boards of the Jikei University, School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan (approval number: 31-175 [9674]). Disclosure of this study was opt-out at each institution.

We collected the data for the number of total and twin deliveries in addition to that of the twins, including maternal age, method of conception, karyotype, and pregnancy outcomes from each facility. Chromosomal abnormalities were diagnosed by karyotyping using chorionic villus or amniotic fluid, prenatally, or peripheral blood, postnatally. Most of these tests were offered in case of abnormal clinical findings, including prenatal ultrasound findings and postnatal dysmorphic features. These tests were also sought by women of advanced maternal age (AMA; ≥ 35 years), even in the absence of abnormal findings. In cases of positive noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) results for women of AMA further investigations such as amniocentesis was performed. If there were no findings suggestive of chromosomal abnormalities during the fetal or neonatal period, chromosomal tests were not performed and the case was deemed to have “no chromosomal abnormalities”. Karyotype annotation was in accordance with the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature 2016.

Statistical analysis was performed using the EZR software (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Shimotsuke, Japan) and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The expected incidence of trisomy 21 in twin pregnancies was calculated by extrapolating from maternal age-matched risk using the Morris model [7]. The Morris model calculates the risk of Down syndrome using the following formula: risk = 1/(1 + exp (7.330 − 4.211/(1 + exp (−0.282 × (age − 37.23))))). Relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were estimated to compare the incidence of trisomy 21 between twin pregnancies and singleton pregnancies. RR were adjusted for maternal age divided into 1-year blocks.

Results

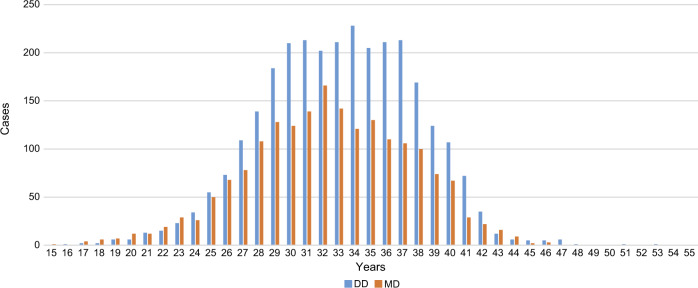

The study cohort included 120,927 deliveries from 57 facilities across Japan, among which 4921 (4.1%) were twin pregnancies. A total of 114 cases were excluded from the analysis, of which 68 cases were of MM twins and of unknown chorionicity, 22 cases were of ovum donation, 8 cases were of unknown age at the time of ovum collection, 5 cases were of vanishing twins, and 11 cases were of reduced fetuses. Of the 4807 included twin pregnancies, 2899 (60.3%) were DD twins and 1908 (39.7%) were MD twins (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Number and types of twin pregnancies included in the study.

The number and types of twin pregnancies included in the study, as well as the excluded cases and the reason for exclusion, are summarized. DD Dichorionic diamniotic, MD Monochorionic diamniotic, and MM Monochorionic monoamniotic.

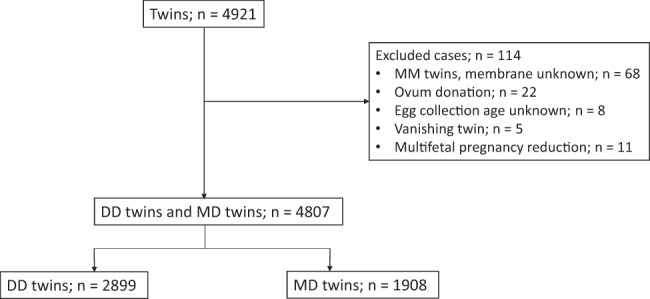

Table 1 shows a comparison of the maternal characteristics of DD and MD twins. The mean maternal age was 33.1 ± 4.8 and 32.4 ± 5.1 years in DD and MD twins, respectively (p < 0.001). As for the method of conception, MD twins had significantly more natural pregnancies (p < 0.001), whereas more than half of DD twins were conceived through infertility treatment. The maternal age distribution of DD and MD twins are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics of twin pregnancies.

| DD twins (n = 2899) | MD twins (n = 1908) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (mean ± SD years) | 33.1 ± 4.8 | 32.4 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Conception mode (% of total pregnancies studied) | <0.001 | ||

| Natural conception | 1333 (46.0) | 1473 (77.2) | |

| Infertility treatment | 1566 (54.0) | 435 (22.8) | |

| Ovulation drugs | 495 (17.1) | 66 (3.5) | |

| AIH | 263 (9.1) | 44 (2.3) | |

| IVF-ET | 509 (17.6) | 213 (11.2) | |

| ICSI | 258 (8.9) | 92 (5.1) | |

| Other | 41 (1.4) | 20 (0.9) | |

| Gestational age at delivery (mean ± SD weeks) | 35.7 ± 3.0 | 34.6 ± 4.6 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: AIH Artificial insemination with donor semen, DD Dichorionic diamniotic,

ICSI Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, IVF-ET In vitro fertilization and embryo transfer,

MD Monochorionic diamniotic, and SD Standard deviation.

Fig. 2. Maternal age distribution in different groups.

The number of mothers of DD and MD twins and the maternal age is displayed. DD Dichorionic diamniotic and MD Monochorionic diamniotic

The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in DD and MD twins is shown in Table 2. We classified chromosomal abnormalities into three types: recognizable phenotype, mild phenotype, and no phenotype. The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in one or both fetuses were 0.9% (25/2899) in DD twins, which was significantly higher than that in MD twins (0.2% [4/1908] (p = 0.004). The most common chromosomal abnormality was trisomy 21 (51.7% [15/29]), followed by trisomy 18 (13.8% [4/29]), and trisomy 13 (6.9% [2/29]). The incidence of trisomy 21 in DD twins was significantly higher than that in MD twins (0.5% vs. 0.05%, p = 0.007). Trisomy 21 was identified in only one fetus of the twin pairs in DD twins; however, trisomy 21 occurred in both fetuses of one pair in MD twins. There were no significant differences in the frequency of chromosomal abnormalities other than trisomy 21 between DD and MD twins. Eleven cases (8 DD and 3 MD twins) had abnormal findings, such as cardiac malformations and multiple malformations; however, the results of karyotyping were normal.

Table 2.

The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities.

| Abnormal karyotype | Total N = 4807 | DD twins N = 2899 | MD twins N = 1908 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recognizable phenotype | ||||

| Trisomy 21 | 15 (0.3) | 14 (0.5) | 1* (0.05) | 0.007 |

| Trisomy 18 | 4 (0.08) | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.05) | 1.000 |

| Trisomy 13 | 2 (0.04) | 2 (0.07) | 0 | 0.521 |

| Additional material on the chromosomea | 1 (0.02) | 0 | 1 (0.05) | |

| Marker chromosomeb | 2 (0.04) | 1 (0.03) | 1 (0.05) | |

| Deletionc | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.03) | 0 | |

| Mild phenotype | ||||

| Sex chromosomal aneuploidy | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mosaic aneuploidyd | 2 (0.04) | 2 (0.07) | 0 | |

| No phenotype | ||||

| Inversione | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.03) | 0 | |

| Robertsonian translocationf | 1 (0.02) | 1* (0.03) | 0 | |

| Total | 29 (0.6) | 25 (0.9) | 4 (0.2) | 0.004 |

*Both fetuses were diagnosed with chromosomal abnormalities.

Abbreviations: DD Dichorionic diamniotic, MD Monochorionic diamniotic.

a46,XY,der(11)t(11;12)(q24.1;11.1).

b47,X, + 2mar[8]/46,X, + mar[6]/48,X, + 3mar[2]/48,XX, +2mar[1]. 47,XY, + mar.

c46,XY,del(18)(q23).

d47,XX, + 21[4]/46,XX[12]. 47,XX, + 4[17]/47,XX[33].

e46,XX,inv(1)(p22p35).

f45,XY,der(13;14)(q10:q10).

Table 3 shows a comparison of the observed and expected incidence of trisomy 21 per fetus in each group. The observed incidence of trisomy 21 was significantly lower than the expected incidence in both MD (0.05% vs. 0.3%, RR 0.15 [95% CI 0.04–0.68]) and total (0.2% vs. 0.4%, RR 0.45 [95% CI 0.25–0.83]) twins. However, there were no significant differences between the observed and expected incidence of trisomy 21 in DD twins (0.2% vs. 0.4%, RR 0.64 [95% CI 0.33–1.24]).

Table 3.

Comparison of the incidences of trisomy 21 per fetus between observed and expected.

| Number of trisomy 21 fetuses | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Observed incidence (%) | Expected incidence (%)* | RR observed versus expected (95% CI) | |

| DD twins | 14 (0.2) | 21.7 (0.4) | 0.64 (0.33-1.24) |

| MD twins | 2 (0.05) | 12.9 (0.3) | 0.15 (0.04-0.68) |

| Total Twins | 16 (0.2) | 34.6 (0.4) | 0.46 (0.25-0.83) |

*Expected incidence of trisomy 21 calculated by maternal age-matched singleton rates using the Morris model (Morris, 2002).

Abbreviations: DD Dichorionic diamniotic and MD Monochorionic diamniotic.

Discussion

This retrospective investigation provides an overview of the rates of chromosomal abnormalities in twin pregnancies after 12 weeks of gestation. In this study, approximately half of the chromosomal abnormalities were trisomy 21. We found that the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in MD twins was lower than that in DD twins, and the incidence of trisomy 21 in MD twins was lower than that in DD twins. We also compared the observed incidence of trisomy 21 for twin pregnancies with the expected incidence based on maternal age-matched singletons and found that the observed incidence was lower than the expected incidence, especially in MD twins.

Half of the chromosomal abnormalities found in twin pregnancies in this study included trisomy 21 (51.7% [15/29]), followed by trisomy 18 (13.8% [4/29]), and trisomy 13 (6.9% [2/29]). These findings were similar to the general frequency in fetuses or neonates reported previously [8, 9]. No cases of sex chromosome aneuploidy were found in this study. It is suspected that neonates with sex chromosome aneuploidy were not karyotyped because they showed no dysmorphic features.

In this study, MD twins were found to have a significantly lower incidence of chromosomal abnormalities compared with DD twins (0.9% vs. 0.2%, p = 0.004). The incidence of trisomy 21 was also significantly lower in MD twins than in DD twins (0.5% vs. 0.05%, p = 0.007). Monozygotic twins have a reportedly lower frequency of trisomy 21 compared with dizygotic twins [6], although monozygotic twins are not exactly the same as MD twins. Of note, 25–30% of monozygotic twins are DD twins [10].

We found that the risk of trisomy 21 is lower in twins, especially in MD twins than in singleton pregnancies. The incidence of chromosomal abnormalities was found to be lower in twins than that reported in singleton pregnancies [8, 9], contrasting with previous reports that suggested that twins had a higher risk of chromosomal abnormalities [11, 12]. Some studies from America and Europe showed a lower risk of trisomy 21 in twins than in singletons. There was only one report which mentioned that the ratio of observed-to-expected trisomy 21 incidence per pregnancy for monozygotic, dizygotic, and all twins was 33.6%, 75.2%, and 70.0%, respectively [6]. In our study, the observed incidence of trisomy 21 was significantly lower than the expected incidence in both MD twins (0.05% vs. 0.3%, RR 0.15 [95% CI 0.04–0.68]) and total twins (0.2% vs. 0.4%, RR 0.45 [95% CI 0.25–0.83]).

The low frequency of chromosomal abnormalities in twin pregnancies could be attributed to the fact that many twin pregnancies are lost or converted to singleton pregnancies [13–15]. Most twins are lost very early in the pregnancy. One study estimated that only one in eight individuals originating as a twin actually goes on to be born as a twin [16]. Furthermore, the abortion rate in twin pregnancies is three times higher than in singleton pregnancies [17, 18]. In addition, in twin pregnancies, embryos and fetuses with chromosomal abnormalities are likely to be eliminated, resulting in singleton pregnancies or miscarriages [10]. Therefore, the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in twin pregnancies that reach 12 weeks of gestation is likely to be lower than that in singleton pregnancies, and our results support this argument. Early pregnancy loss is significantly more common in monochorionic than in dichorionic twins and, in the setting of concordance for aneuploidy, an even higher risk of loss may have contributed to the relatively low incidence of Down syndrome in monozygotic pregnancies [19, 20].

This study has some limitations given the nature of the data used and the study design. Since this study included only cases where fetal heartbeats were confirmed after 12 weeks of gestation, cases of spontaneous abortion before the diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities as well as of induced abortion without fetal chromosomal examination were excluded. In addition, some cases deemed to have “no chromosomal abnormalities” might have had chromosomal abnormalities with minor phenotypic manifestations, mosaicism, or sex chromosome abnormalities, since chromosomal tests were not performed in all cases. In cases without karyotyping, we diagnosed “no chromosomal abnormalities” by ultrasound examination during the fetal period, which does not show morphological abnormalities or multiple malformations that are often accompanied by chromosomal abnormalities, and no external surface malformations or clinical findings that are suspected to be chromosomal abnormalities after birth. Nonetheless, all cases with more than 12 weeks of gestation, and not just cases in the third trimester, were included in the study, ensuring that the cases of induced abortion due to prenatal diagnosis were also included. In this study, chromosomal tests were not performed in all cases, but at least chromosomal abnormalities that affect the phenotype could be extracted. In some cases, chromosomal abnormalities were not observed even if there were phenotypic abnormalities, such as multiple malformations.

In this study, DD and MD twins were compared based on membrane and not zygosity. Of note, 25–30% of monozygotic twins are DD twins [10]. Although DNA analyses of newborns are required to determine zygosity, chorionicity is more practical because it is determined by prenatal ultrasound. In clinical practice, the management of twin pregnancies depends on chorionicity. Therefore, the results of this study are clinically more useful.

This is the first attempt to investigate the frequency of chromosomal abnormalities in twin pregnancies in Japan. In most of the previous studies conducted in Europe and in the United States, only the incidence of Down syndrome was investigated [6, 21]. In contrast, in this study, the rate of all chromosomal aberrations in twin pregnancies was evaluated, which revealed that MD twins have a lower chromosomal aberration rate than DD twins. This study may provide useful information that could pave the way for better genetic counseling before prenatal testing.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was in part supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C; Number 17K10194).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Leila P, Sedigheh A, Shahrzad J, Ahmadreza Z, Mohammad SSA. Obstetrics and perinatal outcomes of dichorionic twin pregnancy following ART compared with spontaneous pregnancy. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2016;14:317–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang Y, Ma CX, Cui W, Chang V, Ariet M, Morse SB, et al. The risk of birth defects in multiple births: a population-based study. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang XH, Qiu LQ, Huang JP. Risk of birth defects increased in multiple births. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:34–8. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glinianaia SV, Rankin J, Wright C. Congenital anomalies in twins: a register-based study. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1306–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toufaily MH, Westgate MN, Lin AE, Holmes LB. Causes of congenital malformations. Birth Defects Res. 2018;110:87–91. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teresa NS, Mary EN, Monica F, Sara G, Robert JC. Observed rate of Down syndrome in twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:1127–33.. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JK, Mutton DE, Alberman E. Revised estimates of the maternal age specific live birth prevalence of Down’s syndrome. J Med Screen. 2002;9:2–6. doi: 10.1136/jms.9.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wellesley D, Dolk H, Boyd PA, Greenlees R, Haeusler M, Nelen V, et al. Rare chromosome abnormalities, prevalence and prenatal diagnosis rates from population-based congenital anomaly registers in Europe. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:521–6. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishiyama M, Yan J, Yotsumoto J, Sawai H, Sekizawa A, Sago H, et al. Chromosome abnormalities diagnosed in utero: a Japanese study of 28983 amniotic fluid specimens collected before 22 weeks gestations. J Hum Genet. 2015;60:133–7. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2014.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall JG. Twinning. Lancet. 2003;362:735–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.John FR, James FXE, Alicia C, Leslie C, Robert MG, William ES. Calculated risk of chromosomal abnormalities in twin gestations. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:1037–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benirschke K, Kim CK. Multiple pregnancy. N. Engl J Med. 1973;288:1329–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197306212882505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landy HJ, Weiner S, Corson SL, Batzer FR, Bolobnese RJ. The “vanishing twin”: Ultrasonographic assessment of fetal disappearance in the first trimester. Am J Obst Gynecol. 1986;155:14–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(86)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levi S. Ultrasonic assessment of the high rate of human multiple pregnancy in the first trimester. J Clin Ultrasound. 1976;4:3–5. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varma TR. Ultrasound evidence of early pregnancy failure in patients with multiple conceptions. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1979;86:290–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1979.tb11258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boklage CE. Survival probability of human conceptions from fertilization to term. Int J Fertil. 1990;35:75–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livingston JE, Poland BJ. A study of spontaneously aborted twins. Teratology. 1980;21:139–48. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420210202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uchida IA, Freeman VCP, Gedeon M, Goldmaker J. Twinning rate in spontaneous abortions. Am J Hum Genet. 1983;35:987–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Antnio F, Khalil A, Dias T, Thilaganayhan B. Early fetal loss in monochorionic and dichorionic twin pregnancies: analysis of the Southwest Thames Obstetric Research Collaborative (STORK) multiple pregnancy cohort. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:632–6. doi: 10.1002/uog.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPherson JA, Odibo AO, Shanks AL, Roehl KA, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Impact of chorionicity on risk and timing of intrauterine fetal demise in twin pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:190.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyle B, Morris JK, McConkey R, Garne E, Loane M, Dolk H, et al. Prevalence and risk of Down syndrome in monozygotic and dizygotic multiple pregnancies in Europe: implications for prenatal screening. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121:809–19.. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.