Abstract

Background

Experiencing anxiety and depression is very common in people living with dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI). There is uncertainty about the best treatment approach. Drug treatments may be ineffective and associated with adverse effects. Guidelines recommend psychological treatments. In this updated systematic review, we investigated the effectiveness of different psychological treatment approaches.

Objectives

Primary objective

To assess the clinical effectiveness of psychological interventions in reducing depression and anxiety in people with dementia or MCI.

Secondary objectives

To determine whether psychological interventions improve individuals' quality of life, cognition, activities of daily living (ADL), and reduce behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, and whether they improve caregiver quality of life or reduce caregiver burden.

Search methods

We searched ALOIS, the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group's register, MEDLINE, Embase, four other databases, and three trials registers on 18 February 2021.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared a psychological intervention for depression or anxiety with treatment as usual (TAU) or another control intervention in people with dementia or MCI.

Data collection and analysis

A minimum of two authors worked independently to select trials, extract data, and assess studies for risk of bias. We classified the included psychological interventions as cognitive behavioural therapies (cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), behavioural activation (BA), problem‐solving therapy (PST)); 'third‐wave' therapies (such as mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT)); supportive and counselling therapies; and interpersonal therapies. We compared each class of intervention with control. We expressed treatment effects as standardised mean differences or risk ratios. Where possible, we pooled data using a fixed‐effects model. We used GRADE methods to assess the certainty of the evidence behind each result.

Main results

We included 29 studies with 2599 participants. They were all published between 1997 and 2020. There were 15 trials of cognitive behavioural therapies (4 CBT, 8 BA, 3 PST), 11 trials of supportive and counselling therapies, three trials of MBCT, and one of interpersonal therapy. The comparison groups received either usual care, attention‐control education, or enhanced usual care incorporating an active control condition that was not a specific psychological treatment. There were 24 trials of people with a diagnosis of dementia, and five trials of people with MCI. Most studies were conducted in community settings. We considered none of the studies to be at low risk of bias in all domains.

Cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT, BA, PST)

Cognitive behavioural therapies are probably slightly better than treatment as usual or active control conditions for reducing depressive symptoms (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.23, 95% CI ‐0.37 to ‐0.10; 13 trials, 893 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence). They may also increase rates of depression remission at the end of treatment (risk ratio (RR) 1.84, 95% CI 1.18 to 2.88; 2 studies, with one study contributing 2 independent comparisons, 146 participants; low‐certainty evidence). We were very uncertain about the effect of cognitive behavioural therapies on anxiety at the end of treatment (SMD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.36 to 0.30; 3 trials, 143 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). Cognitive behavioural therapies probably improve patient quality of life (SMD 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.50; 7 trials, 459 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence) and activities of daily living at end of treatment compared to treatment as usual or active control (SMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.40 to ‐0.09; 7 trials, 680 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Supportive and counselling interventions

Meta‐analysis showed that supportive and counselling interventions may have little or no effect on depressive symptoms in people with dementia compared to usual care at end of treatment (SMD ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.07; 9 trials, 994 participants; low‐certainty evidence). We were very uncertain about the effects of these treatments on anxiety, which was assessed only in one small pilot study.

Other interventions

There were very few data and very low‐certainty evidence on MBCT and interpersonal therapy, so we were unable to draw any conclusions about the effectiveness of these interventions.

Authors' conclusions

CBT‐based treatments added to usual care probably slightly reduce symptoms of depression for people with dementia and MCI and may increase rates of remission of depression. There may be important effect modifiers (degree of baseline depression, cognitive diagnosis, or content of the intervention). CBT‐based treatments probably also have a small positive effect on quality of life and activities of daily living. Supportive and counselling interventions may not improve symptoms of depression in people with dementia. Effects of both types of treatment on anxiety symptoms are very uncertain. We are also uncertain about the effects of other types of psychological treatments, and about persistence of effects over time. To inform clinical guidelines, future studies should assess detailed components of these interventions and their implementation in different patient populations and in different settings.

Keywords: Humans, Anxiety, Anxiety/therapy, Anxiety Disorders, Anxiety Disorders/therapy, Cognitive Dysfunction, Cognitive Dysfunction/therapy, Dementia, Dementia/complications, Dementia/therapy, Depression, Depression/therapy, Quality of Life

Plain language summary

Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in dementia and mild cognitive impairment

Key points

‐ Psychological treatments based on cognitive behavioural therapy (which focuses on changing thoughts and behaviours) probably have small positive effects on depression, quality of life and daily activities in people with dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

‐ There is not enough evidence to know whether any psychological treatments are helpful for anxiety in people with dementia or MCI.

‐ More evidence is needed about different types of psychological treatments and which treatments may be best for which people.

What are dementia and mild cognitive impairment?

Dementia is a condition in which problems develop with cognition (memory and thinking skills). Someone with dementia is no longer able to manage all their daily activities independently. Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is less severe and does not have a significant effect on daily activities. Some people with MCI will go on to develop dementia.

What do we mean by psychological treatments?

Psychological treatments, sometimes known as ‘talking therapies’, are based on psychological theories. They involve a therapist working together with an individual or a small group of people to develop skills and strategies to improve well‐being. These treatments can be adapted for people with cognitive impairment.

What did we want to find out?

Depression and anxiety are common in people with dementia and MCI, but the best way to treat them is unclear. Medicines often used to treat these problems may not be effective for people with dementia and may cause side effects, so many guidelines recommend trying psychological treatments first. We were interested in psychological therapies that aim to reduce symptoms of anxiety or depression or to improve the emotional well‐being of people with dementia or MCI. There are a variety of different types of psychological treatment. We wanted to find out how effective each treatment is for symptoms of depression and anxiety in people with dementia or MCI. We also wanted to find out about effects on quality of life, ability to manage daily activities and thinking skills, and to know if the treatments had any unwanted effects.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that compared a psychological treatment to usual care, or to usual care plus a treatment that was not a specific psychological treatment.

We divided the psychological treatments into several broad categories based on the theory behind them and the content of the treatment sessions, and we looked at each category separately. We summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found 29 studies that included 2599 people with dementia or MCI. Most of the evidence we found was about treatments based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT, which aims to alter thoughts and behaviours) and treatments aimed at supporting well‐being, which we called counselling and supportive therapies. We also found a very small number of studies about mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy and interpersonal therapy. The majority of studies looked at the effect on depression, but very few studies had anxiety as an outcome.

The evidence we found suggests that:

‐ CBT‐based treatments probably improve symptoms of depression, quality of life and ability to manage daily activities at the end of the treatment period in people with dementia or MCI, although the effects were small. We could not be sure about any effect on anxiety. There was some evidence that the effect on depression might depend on how severe the symptoms of depression were before the start of treatment, whether people had a diagnosis of dementia or MCI and what type of treatment was used, but more research would be needed to be sure about this.

‐ Supportive and counselling treatments may have no effect on symptoms of depression at the end of treatment and there was not enough evidence for us to know if there was any effect on anxiety.

‐ We cannot be sure about the effect of mindfulness‐based therapies or interpersonal therapy because there were very few studies of these treatments.

There was limited information about unwanted effects associated with any of the treatments.

We also found 14 ongoing studies, so we can expect more evidence about our question to become available in the next few years.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

We could be moderately certain about the small positive effects of CBT‐based treatments on depression, quality of life and daily activities, but were less certain about other results. Most people in the review had dementia of mild to moderate severity so the results may not apply to people with MCI or more severe dementia. Very few studies included only people who had significant levels of depression before treatment, although these are the people most likely to be offered treatment in practice. There is not yet enough evidence to be able to say which people are most likely to benefit from which psychological treatments.

How up to date is the evidence?

This review is up to date to February 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. CBT treatments compared to treatment as usual for depression and anxiety for people with dementia and MCI.

| CBT treatments compared to treatment as usual for depression and anxiety for people with dementia and MCI | ||||

| Patient or population: depression and anxiety for people with dementia and MCI Setting: community or long‐term care Intervention: CBT treatments Comparison: treatment as usual (usual care, attention‐control education, diagnostic feedback, or services slightly above usual care comprising active control conditions) | ||||

| Outcomes | SMD (95% CI) meta‐analysis/ relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Depressive symptoms post‐treatment assessed with: GDS, HDRS, MADRS, PHQ‐9, and CSDD Follow‐up: range 8 weeks to 24 months | SMD 0.23 lower (0.37 lower to 0.10 lower) | 893 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Higher scores indicate higher symptoms of depression. |

| Depression remission post‐treatment assessed with: MADRS, and DSM‐III‐R Follow‐up: range 10 weeks to 12 weeks | RR 1.84 (1.18 to 2.88) | 146 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | A RR > 1 favours the intervention group. |

| Anxiety symptoms post‐treatment assessed with: GAI, RAID, and NPI‐A Follow‐up: range 3 months to 15 weeks | SMD 0.03 lower (0.36 lower to 0.30 higher) | 143 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,d | Higher scores indicate higher symptoms of anxiety. |

| Quality of life post‐treatment assessed with: DEMQOL, QoL‐AD, LSI‐A, and QoL‐AD NH Follow‐up: range 8 weeks to 15 weeks | SMD 0.31 higher (0.13 higher to 0.50 higher) | 459 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Higher scores indicate better quality of life. |

| Activities of daily living post‐treatment assessed with: ADL‐PI, SDS, WHODAS 2.0, B‐ADL, ADCS‐ADL, BADLS, and UPSA Follow‐up: range 12 weeks to 2 years | SMD 0.25 lower (0.40 lower to 0.09 lower) | 680 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Lower scores indicate better performance of ADL. |

| Cognition post‐treatment assessed with: MMSE Follow‐up: range 10 weeks to 2 years | SMD 0.13 higher (0.04 lower to 0.30 higher) | 535 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,d | Higher scores indicate better cognition. |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms post‐treatment assessed with: NPI, RMBPC, and BEHAVE‐AD Follow‐up: range 10 weeks to 3 months | SMD 0.06 lower (0.26 lower to 0.14 higher) | 401 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Higher scores indicate more or more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

aDowngraded once for serious limitations to study quality bDowngraded twice for very serious imprecision cDowngraded once for serious inconsistency dDowngraded once for serious imprecision

ADCS‐ADL: Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study – Activities of Daily Living Inventory; ADL‐PI: Activities of Daily‐Living Prevention Instrument; B‐ADL: Bayer Activities of Daily Living Scale; BADLS: Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale; BEHAVE‐AD: Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; CSDD: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; DEMQOL: Dementia Quality of Life Instrument; DSM‐III‐R: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition, Revised; GAI: Geriatric Anxiety Inventory; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; LSI‐A: Life Satisfaction Index; MADRS: Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MMSE: Mini‐Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; NPI‐A: Neuropsychiatric Inventory‐Anxiety; PHQ‐9: Patient Health Questionnaire‐9; QoL‐AD: Quality of Life‐Alzheimer’s Disease; QoL‐AD NH: Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease in Nursing Homes; RAID: Rating Anxiety in Dementia; RMBPC: Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist; SDS: Sheehan Disability Scale; UPSA: University of California San Diego Performance‐Based Skills Assessment; WHODAS 2.0: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0

Summary of findings 2. Supportive and counselling interventions compared to treatment as usual for depression and anxiety for people with dementia.

| Supportive and counselling interventions compared to treatment as usual for depression and anxiety for people with dementia | ||||

| Patient or population: depression and anxiety for people with dementia Setting: community or long‐term care Intervention: supportive and counselling interventions Comparison: treatment as usual (usual care, attention‐control education, diagnostic feedback, or services slightly above usual care) | ||||

| Outcomes | SMD (95% CI) meta‐analysis | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Depressive symptoms post‐treatment assessed with: CSDD, BDI, GDS, and MADRS Follow‐up: range 9 weeks to 3 years | SMD 0.05 lower (0.18 lower to 0.07 higher) | 994 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Higher scores indicate higher symptoms of depression. |

| Depression remission post‐treatment | Not measured | |||

| Anxiety symptoms post‐treatment assessed with: HADS Follow‐up: mean 3 months |

MD 0.80 lower (3.07 lower to 1.47 higher) | 24 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,d | Higher scores indicate higher symptoms of anxiety. |

| Quality of life post‐treatment assessed with: EQ‐5D, QoL‐AD, and 15D Follow‐up: range 9 weeks to 3 years | SMD 0.15 higher (0.02 higher to 0.28 higher) | 935 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Higher scores indicate better quality of life. |

| Activities of daily living post‐treatment assessed with: ADCS‐ADL and Barthel Index Follow‐up: range 6 months to 3 years | SMD 0.17 higher (0.01 lower to 0.34 higher) | 511 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | Lower scores indicate better performance of ADL. |

| Cognition post‐treatment assessed with: MMSE and CDT Follow‐up: range 10 weeks to 3 years | SMD 0.11 higher (0.03 lower to 0.26 higher) | 730 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Higher scores indicate better cognition. |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms post‐treatment assessed with: NPI and RMBPC Follow‐up: range 9 weeks to 3 years | SMD 0.11 higher (0.06 lower to 0.29 higher) | 538 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,d | Higher scores indicate more or more severe neuropsychiatric symptoms. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

aDowngraded once for serious limitations to study quality bDowngraded once for serious imprecision cDowngraded twice for very serious imprecision dDowngraded once for serious inconsistency

ADCS‐ADL: Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study – Activities of Daily Living Inventory; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CDT: Clock Drawing Test; CSDD: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; EQ‐5D: EuroQoL‐5 Dimension; 15D: 15D instrument; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MADRS: Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MMSE: Mini‐Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; QoL‐AD: Quality of Life‐Alzheimer’s Disease; RMBPC: Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist

Background

Description of the condition

People living with dementia are twice as likely as age‐matched controls to be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, which has a significant impact on quality of life (Enache 2011). The most recent comprehensive systematic review of the prevalence of major depressive disorder in all‐cause dementia has shown that it is common, affecting approximately 15.9% of the population (Asmer 2018). Prevalence is higher in vascular dementia (24.7%) than in dementia due to Alzheimer's disease (AD) (14.8%). Younger age, a family history of psychiatric disorder, and presence of sleep disturbances and aggression are all associated with higher rates of clinical depression in AD (Steck 2018). In mild cognitive impairment (MCI), depressive symptoms are also common, with overall pooled prevalence reported to be 32%, and greater burden reported in clinic‐based samples (Ismail 2017).

Although anxiety symptoms are common in people with dementia and MCI (Hwang 2004), there is a lack of consensus about how to define and conceptualise anxiety in the context of cognitive impairment. Starkstein 2007 has proposed a revision of diagnostic criteria for generalised anxiety disorder for people with dementia, consisting of excessive anxiety and worry (criteria A and B of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM‐IV)) and any three of the symptoms of restlessness, irritability, muscle tension, fear, and respiratory symptoms. Anxiety is more common in individuals with dementia than those without. Prevalence rates for anxiety disorders are generally similar to those for depression, with overall estimates at around 14% for both dementia (Kuring 2018), and MCI populations (Chen 2018), and evidence of slightly higher estimates in clinic‐based samples.

Regarding the impact of the conditions, studies show that the severity of both anxiety and depression increases the severity of neurological impairment, which impacts on independence (Stogmann 2016), caregiver burden (Cheng 2017), and risk of entering long‐term care (Cepoiu‐Martin 2016). Symptoms of depression in MCI can be persistent and refractory to antidepressant medication (Devanand 2003), and generally predictive of higher rates of progression to AD dementia (Cooper 2015).

Description of the intervention

The main psychotherapeutic approaches in treating depression and anxiety in adults, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), behavioural activation (BA), problem‐solving therapy (PST), interpersonal therapy (IPT), and integrative approaches such as counselling, and psychodynamic therapies (WHO 2019). 'Third‐wave CBT' approaches include interventions characterised by techniques that focus on the process, rather than the content of thoughts, helping people accept their thoughts in a non‐judgmental way (Hofmann 2010). Examples of 'third‐wave' approaches include interventions such as mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Teasdale 1995), and acceptance and commitment therapy (Lars‐Göran 2014). Other psychological interventions include humanistic approaches (Cain 2002), and systemic therapies (MacFarlane 2003). Offering psychological treatments to older people is generally worthwhile as it promotes improvements in depression and anxiety and increases general psychological well‐being (Hall 2016; Jonsson 2016; Kirkham 2016).

Pharmacological treatments for depression and anxiety are prescribed for people with dementia, despite evidence that their clinical effectiveness, at least for depression, may be limited (Dudas 2018; Orgeta 2017). Psychological interventions are currently recommended for the management of depression and anxiety for people with dementia and are part of current clinical guidelines in several countries, such as in the UK (NICE 2018). These interventions have been adapted for people who experience dementia and cognitive impairment, through the use of behavioural techniques, in order to compensate for losses in cognition and declining sensory function (Grant 1995).

A wide variety of psychological interventions has been studied within the context of improving affective function for people with dementia and cognitive impairment. CBT is an umbrella term encompassing a wide range of therapeutic approaches that combine cognitive components (aimed at thinking processes such as identifying and challenging unrealistic negative thoughts) and behavioural components (aimed at increasing rewarding activities). BA is a component of CBT but also considered a psychological intervention on its own, comparable to CBT in terms of clinical effectiveness for depression (Richards 2016). BA is focused on reducing depressive symptoms by supporting individuals to set goals and engage in pleasant activities on a daily basis, and to modify precipitants of distress (Teri 2003). Other psychotherapies include IPT, which focuses on the connection between depressive symptoms and interpersonal problems (Churchill 2018), cognitive analytic therapy, or other integrative therapies such as counselling. Interventions for people with dementia and cognitive impairment may also focus on building social support, aiming to foster social networks and to help people to cope with cognitive loss in order to reduce psychological distress.

Although there are a number of other types of interventions which incorporate some psychological elements and which target depression and anxiety in dementia, such as reminiscence (Woods 2018), and interventions focusing on environmental changes or exercise (Gitlin 2003; Rolland 2007), the present review focuses on psychological interventions; that is, interventions primarily based on psychological models as defined by WHO 2019.

How the intervention might work

Most psychological treatments based on the cognitive‐behavioural model emphasise the need to modify dysfunctional beliefs as well as incorporating components of behavioural therapy. Their aim is to challenge negative cognitions that maintain depressive symptomatology and anxiety symptoms (WHO 2019). An important component of CBT is monitoring and identifying thoughts and behaviours that contribute to depression or anxiety (Beck 1979). Treatment components of CBT for anxiety often include additional techniques such as teaching of relaxation skills (Stanley 2004). Modifications of CBT emphasise cognitive strategies in early‐stage dementia and behavioural strategies in later stages, reducing cognitive load and utilising concrete examples (Gellis 2009). PST aims to help people learn skills to actively, constructively, and effectively solve problems they face in their daily life (Nezu 2010). Treatment goals often include the development of a positive problem‐solving orientation, through the use of rational strategies, and reducing the tendency to avoid problems (D'Zurilla 2010). BA, which is an integral part of CBT, can also be provided as a brief psychotherapeutic approach on its own (Dimidjian 2006). Techniques incorporated into treatment include changing the way a person interacts with their environment, by increasing access to positive reinforcers of healthy behaviours, reducing behaviours that limit access to positive reinforcement, and addressing barriers to activation (Dimidjian 2006; Jacobson 2001).

Psychodynamic therapies use the therapeutic alliance between patient and therapist to support the development of self‐awareness, helping people to recognise and modify interpersonal patterns that contribute to psychological distress (Shedler 2010).

IPT focuses on stressful life events, interpersonal difficulties, and important life transitions that may contribute to the onset and maintenance of depressive symptoms, in order to help individuals connect with social support networks and improve the quality of their interpersonal relationships (Ravitz 2019).

Third‐wave CBT approaches conceptualise cognitions as psychological or 'private' events and use strategies such as mindful exercises and acceptance of unwanted thoughts to elicit change in the thinking process and reduce depression (Hofmann 2010).

Counselling interventions focus on enhancing subjective experiences during treatment by focusing on a range of issues such as needs, relationships, and attachments, using structured methods to encourage change (Churchill 2001). Social support interventions have been implemented in diverse chronic conditions, and aim to improve physical and psychosocial health by fostering emotional support and information exchange, empowering individuals to enhance their skills and daily functioning (Dennis 2003). Psychological therapies for people with dementia may involve both the individual and their caregiver(s) in the therapeutic approach (Teri 2003).

Why it is important to do this review

Recommendations stress that the treatment of anxiety and depressive symptoms is an essential part of the treatment of AD and other dementias (Alexopoulos 2005; Azermai 2012). Currently, pharmacological approaches are commonly used for anxiety and depression in dementia, despite research indicative of poor efficacy and side effects of antidepressants (Banerjee 2011; Dudas 2018). Evidence that more than 30% of people with dementia are being prescribed antidepressants indicates potentially inappropriate and unnecessary prescribing (Puranen 2017). Symptoms of anxiety and depression may also contribute to the overuse of antipsychotics, which are associated with substantial adverse effects, such as an increased risk of sedation, falls, and death (Van der Hooft 2008).

Although most current clinical practice guidelines recommend the use of non‐pharmacological interventions as the first line of treatment for both anxiety and depression in dementia (Hogan 2008; Salzman 2008), the evidence base supporting the efficacy of particular psychological interventions remains small. In the previous version of this review, published in 2014, we systematically synthesised evidence on a variety of psychological interventions that were generally based on well‐defined, theory‐driven psychological models that were primarily aimed at people with dementia.

Despite recent reviews being published on the effectiveness of psychological interventions for people with dementia, most focus on behavioural and psychological symptoms in general as opposed to depression and anxiety (Li 2021), and the majority provide narrative reviews of the available literature (Carrion 2018). Given the growth of research in the area and the importance of offering psychological treatments to people with dementia and MCI, this review aims to provide a comprehensive and up‐to‐date evaluation of current evidence, which will be useful for informing clinical guidelines and future research. In conducting this review, we followed the protocol that we published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Orgeta 2011).

Objectives

Primary objective

To assess the clinical effectiveness of psychological interventions in reducing depression and anxiety in people with dementia or MCI.

Secondary objectives

To determine whether psychological interventions improve individuals' quality of life, cognition, activities of daily living (ADL), and reduce behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, and whether they improve caregiver quality of life or reduce caregiver burden.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies in this review if they fulfilled these criteria:

they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐randomised trials;

they included a control group (usual care) or a comparison group receiving no specific psychological intervention; and

they provided separate data on participants with dementia or MCI, or both, if the study was of a mixed population (also including older adults with normal cognition).

We identified ongoing studies but did not include these in the meta‐analysis.

Types of participants

The inclusion criteria for participants were:

people diagnosed with dementia of any type according to validated diagnostic criteria (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) or International Classification of Diseases, or other validated criteria), and people with a diagnosis of MCI. Any definition of MCI was acceptable as long as the criteria used were published and included evidence of objective cognitive impairment but no dementia (e.g. Petersen 1999; Petersen 2003; Visser 2005)

any setting (e.g. home, community, long‐term care/nursing homes, hospital).

Types of interventions

For the purposes of this review, we defined a psychological intervention as an intervention that: (a) was designed to reduce anxiety and depression or improve adaptive functioning, or both; (b) was based on a psychological theory (for example, learning theory); and (c) involved a structured interaction between a facilitator and a participant which incorporated psychological methods (for example,behavioural, cognitive behavioural, family systems), in line with previous meta‐analytic studies and Cochrane Reviews in the general population (Churchill 2018; Uphoff 2020).We included interventions facilitated by psychologists, therapists in training,and other trained professionals. We grouped eligible interventions, where possible, in line with definitions provided by WHO 2019 into these five categories:

CBT therapies (which included CBT, PST, BA or behaviour management therapy);

third‐wave CBT therapies, including MBCT;

psychodynamic therapies (including brief psychotherapy and insight‐oriented psychotherapy);

interpersonal therapies; and

supportive and counselling therapies.

We excluded treatments identifiedas medication, exercise, reminiscence therapy, music therapy, art and drama therapy, yoga/meditation, befriending, or bibliotherapy. If an intervention could not be grouped into any of the preceding categories, we classified it as psychological, and included it in the review if there was some attempt to teach participants skills to reduce psychological distress such as depression and anxiety. We included both individual and group psychological interventions. The treatment could be of any intensity, duration, or frequency. Control conditions included no treatment (usual care) or a comparison group engaging in non‐specific psychosocial activity (for example, attention‐control, or active control conditions controlling for effects of staff attention or social contact). We did not consider comparisons with other therapeutic interventions in this review. We included studies that used combinations of different psychological treatments, or combinations of pharmacological and psychological interventions. In the case of combinations of pharmacological and psychological treatments, a comparison group of the pharmacological intervention alone or with the above control treatments was required.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that measured any of the primary or secondary outcomes specified below. We pre‐specified clinically important outcomes which are relevant to people with dementia and MCI, carers, and healthcare providers.

Primary outcomes

Scale‐based measures of depressive symptoms (e.g. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), Beck Depression Inventory, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)) and anxiety symptoms (e.g. Rating Anxiety in Dementia)

Depression remission (defined by a pre‐specified threshold on a depression scale or no longer meeting clinical criteria for depression). We accepted the authors' definition provided that the remission scores were based on changes in depression measures that were either clinician‐rated or other validated measures, and that these were similar to definitions used in the literature.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

Performance of activities of daily living (ADL)

Cognition

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

Caregivers' quality of life, burden, and depressive symptoms

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched ALOIS (www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois) ‐ the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (CDCIG) Specialised Register. We searched all "Treatment MCI" and "Treatment Dementia" studies in combination with the following terms or phrases: Depression or Dysthymi* or "Adjustment Disorder/s" or "Mood Disorder/s" or "Affective Disorder/s" or "Affective Symptoms", Anxiety or Anxious or phobia/s or "Panic Disorder", psychotherapy, "cognitive therapy", "behaviour therapy", "cognitive behaviour therapy". ALOIS is maintained by the Information Specialists for CDCIG and contains dementia (prevention and treatment), mild cognitive impairment and cognitive improvement studies. The studies are identified from:

monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINHAL), PsycINFO, and Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database (LILACS);

monthly searches of a number of trials registers: meta Register of Controlled Trials (mRCT); Umin Japan Trial Register; World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP/WHO) portal (which covers ClinicalTrials.gov; ISRCTN; Chinese Clinical Trials Register; German Clinical Trials Register; Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others);

quarterly searches of the Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library; and

six‐monthly searches of a number of grey literature sources: ISI Web of knowledge Conference Proceedings; Index to Theses; Australasian Digital Theses.

To view a list of all sources searched for ALOIS see About ALOIS on the ALOIS website. We ran additional separate searches in many of the above sources to ensure that the most up‐to‐date results were retrieved. We describe the search strategies used in Appendix 1. The most recent search was carried out on 18 February 2021.

Searching other resources

We searched identified citations for additional trials and contacted the corresponding authors of identified trials for additional references and unpublished data. We scanned the reference lists of identified publications and all review papers that were related to psychological treatments for people with dementia and MCI.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures as recommended by Cochrane.

Selection of studies

Four review authors (VO, PL, RdPC, AM) worked independently to identify RCTs that met the inclusion criteria, and discussed any disagreements. We excluded those studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained copies of the full texts of potentially relevant references. We documented reasons for exclusion of studies. Where necessary, we requested additional information from study authors.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (VO, PL, AM) independently extracted data, using a standardised data extraction form which was piloted before use. We contacted the authors of the primary trials if there were doubts regarding missing data or methodological details of the trial. The extracted information included data on: participants, methods, interventions, outcomes, and results for all studies meeting the inclusion criteria; ongoing studies; and studies awaiting classification. These details included the following.

Participants: characteristics of the sample (age, diagnostic criteria, severity of cognitive impairment, and exclusion criteria).

Methods: data on methodologies used for randomisation, blinding, outcome reporting, and participant dropout.

Interventions: duration, intensity, type, and frequency of psychological and control interventions.

Outcomes: primary outcomes were ratings of depressive and anxiety symptoms, and depression remission. Secondary outcomes were measures of quality of life, ADL, cognition, and neuropsychiatric symptoms for people with dementia and MCI, and quality of life, depressive symptoms, and carer burden for caregivers.

Results: where data were available, we collected the number of participants for whom the outcome was measured in each group, means and standard deviations (SDs). We used change from baseline scores for all analyses reported (except for the reporting of findings of the study by Quinn 2016) and, if necessary, calculated the change scores. Calculations of the SD of change scores were based on an assumption that the correlation between measurements at baseline and those at subsequent time points is zero. This method overestimates the SD of the change from baseline, but is considered preferable in a meta‐analysis to take a conservative approach.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies (Higgins 2011). The tool addresses six specific domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. Three review authors (VO, PL, AM) independently assessed each domain, resolving any differences through discussion with a fourth review author. In cases where no information was available to make a judgement, we explicitly stated this.

Measures of treatment effect

All outcomes except depression remission at post‐treatment were continuous, and a variety of different scales contributed data to each meta‐analysis. We therefore used the standardised mean difference (SMD) as the measure of treatment effect. For the dichotomous outcome of depression remission, we used risk ratio (RR). For reporting findings of the study by Quinn 2016, we used the mean difference as the measure of treatment effect.

Unit of analysis issues

We identified one trial that had multiple treatment groups: the Teri 1997 study, which contributed two independent comparisons of BA and PST. For this study, we combined the two control conditions and then divided the combined group in the meta‐analysis in line with the methods recommended by Cochrane (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We reported the number of participants included in the final analysis as a proportion of all participants in the study. For each study, we noted what approach had been taken to missing data and considered how each method may have contributed to a risk of bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to assess heterogeneity amongst studies. We defined substantial heterogeneity as an I² of more than 70%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed publication bias by producing funnel plots and inspecting them visually for all analyses combining six studies or more (Egger 1997). Due to the small number of studies combined in meta‐analyses, we did not conduct statistical tests for funnel plot asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We undertook separate comparisons of each of our intervention categories with control interventions at end of treatment, and ‐ where data were available ‐ also at post‐treatment follow‐up.

Where studies were sufficiently similar, we pooled data in meta‐analyses, using a fixed‐effect model to present overall estimated effects. This assumes that all studies are estimating the same (fixed) treatment effect. In practice, we were able to perform meta‐analyses for the following comparisons:

CBT interventions versus treatment as usual (TAU) immediately post‐intervention;

CBT interventions versus TAU at long‐term follow‐up;

supportive and counselling interventions versus TAU immediately post‐intervention.

We used Review Manager 5 to conduct all meta‐analyses (Review Manager 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used subgroup analyses to evaluate the effect of these effect modifiers:

cognitive diagnosis: dementia versus MCI; and

depression at baseline: studies in which all participants met diagnostic criteria for a depressive disorder or exceeded a specified threshold on a depressive symptom scale at baseline versus studies with no depression‐related inclusion criteria.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses to examine the effect of type of control comparison (TAU or active control). Where possible, we performed sensitivity analyses by excluding from the analysis studies at high risk of bias.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence for all outcomes, independently judged by two review authors (Guyatt 2011). Results of our analyses of CBT treatments versus TAU or active control are presented in Table 1, and of supportive and counselling interventions versus TAU in Table 2. Our summary of findings tables included these seven primary and secondary outcomes, measured at the end of the intervention period:

depressive symptoms;

depression remission;

anxiety symptoms;

quality of life;

activities of daily living;

cognition; and

neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

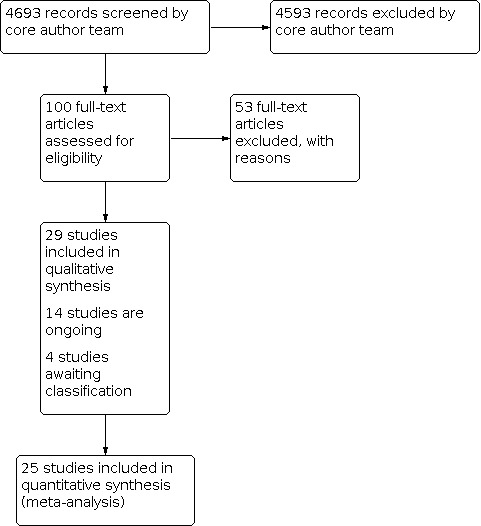

We identified a total of 4693 references through database searching. The search covered December 2011 to February 2021 and consisted of five searches (first search: 292 results; second search: 58 results, plus 3 studies identified by handsearching; third search: 715 results, plus 4 studies identified by handsearching; fourth search: 1511 results; fifth search: 2108 results, plus 2 studies identified by handsearching). The latest search was conducted on 18 February 2021.

We screened a total of 100 full‐text articles for eligibility: we excluded 53 with reasons (see Characteristics of excluded studies); 29 met the inclusion criteria (of which one contributed two independent comparisons, and six were included in the previous version of the review); 14 studies are ongoing (see Characteristics of ongoing studies); and four studies are awaiting classification whilst further information is obtained (see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). See Figure 1 for a PRISMA flow diagram detailing the search process.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

Four studies evaluated the effectiveness of CBT versus TAU: Belleville 2018, Burgener 2008, Spector 2015, and Stanley 2013. Eight studies evaluated BA versus TAU: Kurz 2012, Lai 2020, Lichtenberg 2005, Lu 2016, Orgeta 2019, Rovner 2018 (BA versus an active control condition), Teri 1997 (pleasant‐event scheduling versus typical care control), and Travers 2017. Three studies evaluated PST versus TAU: Kiosses 2010 (PST versus an active control condition), Kiosses 2015 (PST versus an active control condition), and Teri 1997 (problem‐solving versus waiting‐list control). Eleven studies assessed the effectiveness of supportive and counselling interventions versus TAU: Bruvik 2013, Jha 2013, Koivisto 2016, Laakkonen 2016, Logsdon 2010, Marshall 2015, Nordheim 2019, Quinn 2016, Tappen 2009, Waldorff 2012, and Young 2014. Three studies evaluated MBCT versus TAU: Churcher Clarke 2017, Larouche 2019, and Wells 2013. One study evaluated IPT versus TAU: Burns 2005.

The majority of studies reported receiving national government funding (Belleville 2018; Bruvik 2013; Kiosses 2010; Kiosses 2015; Kurz 2012; Logsdon 2010; Lu 2016; Marshall 2015; Nordheim 2019; Quinn 2016; Rovner 2018; Spector 2015; Stanley 2013; Teri 1997; Waldorff 2012; Wells 2013). Two studies reported receiving university research funding (Burgener 2008; Young 2014). The studies by Burns 2005, Orgeta 2019, Travers 2017 and Tappen 2009 received funding from dementia research charities and trusts. One study reported receiving funding from both the pharmaceutical industry and government sectors (Koivisto 2016). Laakkonen 2016 and Larouche 2019 reported receiving funding from both the government and voluntary sectors. The studies by Churcher Clarke 2017, Jha 2013, Lai 2020, and Lichtenberg 2005 did not report their funding source.

Design

All 29 studies were RCTs that compared an eligible psychological intervention to a control intervention (TAU or waiting list or active control condition). Across all included studies, there were 2599 participants (n = 252 for CBT; n = 696 for BA; n = 137 for PST; n = 1381 for supportive and counselling interventions; n = 93 for MBCT; n = 40 for IPT).

CBT‐based therapies

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

Participants and setting

Belleville 2018 recruited people meeting criteria for single‐ or multiple‐domain amnestic MCI (Petersen 2004), from memory clinics in Canada. Burgener 2008 recruited people living with mild dementia in the USA but did not specify the setting. Spector 2015 recruited people with mild to moderate dementia and clinical anxiety living in the community in the UK. Stanley 2013 recruited people with mild to moderate dementia and clinical anxiety living in the community in the USA.

Intervention and control groups

Belleville 2018 evaluated group CBT versus a no‐contact control condition. Burgener 2008 tested the effectiveness of a multimodal intervention consisting of tai chi, CBT, and support groups versus a control condition which consisted of information about educational programs available. Both Spector 2015 and Stanley 2013 evaluated CBT‐based interventions adapted for people with anxiety and dementia versus TAU (medication or no treatment in Spector 2015; diagnostic feedback in Stanley 2013).

Outcomes

All the CBT trials assessed both depression and anxiety except Burgener 2008, which assessed only depression. We present the outcomes assessed across all CBT studies (Belleville 2018; Burgener 2008; Spector 2015; Stanley 2013), the details of participants recruited, and interventions evaluated, in Table 3. All four studies measured persistence of effects (assessed at 6 months, and 40 weeks), but for Burgener 2008 and Spector 2015, data were not available.

1. Table of cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT).

| Participants | Intervention and control conditions | Outcomes | |

| Belleville 2018 | Single‐or multiple‐domain amnestic MCI (Petersen 2004 criteria) n = 127; male (M) 57; female (F) 70 Mean age = 72.6 Mean MoCA = 24.4 Mean GDS‐15 = 3.3 |

Group CBT: cognitive restructuring of thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes helping participants modify thoughts causing unhelpful emotions, additional single booster session Eight 2‐hour group sessions over 8 weeks Control: no contact control condition |

1. Immediate and delayed episodic memory (Belleville 2006) 2. Depression (GDS‐15; Yesavage 1983) 3. Anxiety (GAI; Pachana 2007) 4. Well‐being (General Well‐Being Schedule; Dupuy 1977) 5. Memory strategies (Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire—Memory Strategies; Troyer 2002) 6. Subjective cognitive complaints (Questionnaire d’Auto‐Evaluation de la Mémoire; Van der Linden 1989) 7. Function (Activities of Daily‐Living Prevention Instrument; Galasko 2006) |

| Burgener 2008 | Mild dementia (CDR < 2.0) N = 43; M23; F20 Mean age = 76.9 Mean MMSE = 23.8 Mean GDS‐15 = 3.1 |

Multimodal intervention of tai chi, CBT, and support groups: strength and balance training, small group, and individual CBT which included challenging dysfunctional cognitions, developing positive coping skills, and enhancing personal control (Teri 1991); support groups focused on coping, problem‐solving, and developing relationships (Yale 1995) Tai chi was offered as a 1‐hour class 3 times a week over 20 weeks CBT was offered biweekly for 90 minutes for 20 weeks and social support groups bi‐weekly alternating with CBT over 20 weeks with each session lasting 90 minutes Control: attention‐control receiving information about educational programs available |

1. Cognition (MMSE; Folstein 1975) 2. Physical function (Single‐Leg Stance; Berg 1989, Berg Balance Scale; Rikki 1991, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; Linn 1968) 3. Depression (GDS‐15; Yesavage 1983) 4. Self‐esteem (Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale; Rosenberg 1979) |

| Spector 2015 | Mild to moderate dementia (DSM‐IV; CDR range 0.5 to 2; clinical anxiety ≥ 11 RAID) N = 50; M20; F30 Mean age = 78.5 Mean MMSE = 20.9 Mean RAID = 19.7 Mean CSDD = 15.9 |

CBT: identifying and practicing strategies for feeling safe, challenging negative thoughts, and incorporating calming thoughts, and behavioural experiments A total of 10 sessions, each lasting 60 minutes over 15 weeks Control: treatment as usual which included either medication or no treatment |

1. Anxiety (RAID; Shankar 1999, HADS; Zigmond 1983) 2. Depression (CSDD; Alexopoulos 1988, HADS; Zigmond 1983) 3. Quality of life (QoL‐AD; Logsdon 1999) 4. Cognition (MMSE; Folstein 1975) 5. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (Neuropsychiatric Inventory; Cummings 1994) 6. Patient‐rated quality of the caregiving relationship (QCPR; Spruytte 2002) 7. Caregiver depression (HADS; Zigmond 1983) 8. Caregiver anxiety (HADS; Zigmond 1983) 9. Carer‐rated quality of the caregiving relationship (QCPR; Spruytte 2002) |

| Stanley 2013 | Mild to moderate dementia (confirmed by medical provider; clinical anxiety ≥ 1 NPI‐A) N = 32; M13; F19 Mean age = 78.6 Mean NPI‐A = 4.7 Mean GDS‐30 = 10.1 |

CBT: self‐monitoring for anxiety, deep breathing, and optional skills such as coping self‐statements, behavioural activation, and sleep management Up to 12 weekly home sessions, lasting 30 to 60 minutes over 6 months over the initial 3 months, and up to 8 brief telephone booster appointments Control: treatment as usual which incorporated diagnostic feedback but no additional contact |

1. Anxiety (NPI‐A; Cummings 1994, RAID; Shankar 1999, GAI; Pachana 2007) 2. Worry (Penn State Worry Questionnaire ‐ Abbreviated; Crittendon 2006) 3. Depression (GDS‐30; Yesavage 1983) 4. Quality of life (QoL‐AD; Logsdon 1999) 5. Caregiver distress related to anxiety symptoms (NPI‐A; Cummings 1994) 6. Caregiver depression (Patient Health Questionnaire‐9; Kroenke 2001) |

CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy; GAI: Geriatric Anxiety Inventory; CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating; CSDD: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; DSM‐IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; MMSE: Mini‐Mental State Examination; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NPI‐A: Neuropsychiatric Inventory‐Anxiety; RAID: Rating Anxiety in Dementia; QCPR: Quality of the Carer–Patient Relationship; QoL‐AD: Quality of Life‐Alzheimer’s Disease

Behavioural activation (BA)

Participants and setting

Kurz 2012 recruited people living with mild Alzheimer's disease (AD) in community settings in Germany, and Lai 2020 recruited people living with mild to moderate dementia in their own home in Hong Kong. The Lichtenberg 2005 study was conducted in special dementia care nursing home units in the USA. Both Lu 2016 and Rovner 2018 recruited people with a diagnosis of MCI living in the community in the USA, and Orgeta 2019 recruited people living with mild dementia in the community in the UK. In the Teri 1997 trial, participants lived in their own home (USA), and in the Travers 2017 study, participants were people with dementia living in nursing homes (Australia). Both the Teri 1997 and Travers 2017 studies recruited people with mild to moderate dementia and depression or depressive symptoms at baseline. In the Teri 1997 trial, all participants met Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition, Revised (DSM‐III‐R) criteria for major or minor depressive disorder and had a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) score of at least 10. In the study by Travers 2017, participants scored 4 or higher on the 12‐item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).

Intervention and control groups

Kurz 2012 evaluated a BA program versus a control intervention incorporating standard medical management for early dementia. Lai 2020 evaluated behavioural activity scheduling versus dementia care education over 10 weeks. Lichtenberg 2005 evaluated a behavioural treatment program adapted for people living with dementia in nursing homes versus usual care comprised of regular activities provided within the home. Lu 2016 evaluated an intervention primarily aimed at increasing meaningful activity through planning, versus a control intervention comprised of receiving an educational brochure and follow‐up calls every two weeks. Orgeta 2019 evaluated BA adapted for people living with mild dementia versus TAU, comprising treatments in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. Rovner 2018 evaluated BA aimed at increasing cognitive, physical, and/or social activity versus a supportive control intervention focusing on conveying empathy and optimism. Teri 1997 evaluated pleasant‐event scheduling (of enjoyable activities) and modifying problem behaviours (behavioural and psychological symptoms) versus usual care, consisting of advice and information about support services available and a separate waiting list‐control group. Travers 2017 evaluated pleasant‐event scheduling of enjoyable activities versus a walking and talking intervention with a volunteer for 30 minutes each week.

Outcomes

All studies except Lai 2020 assessed depression. None of the trials assessed anxiety. We present the outcomes assessed across all BA studies (Kurz 2012; Lai 2020; Lichtenberg 2005; Lu 2016; Orgeta 2019; Rovner 2018; Teri 1997; Travers 2017), the details of participants recruited, and the interventions evaluated, in Table 4. Persistence of effects was assessed by Orgeta 2019 (six months) and Teri 1997 (six months), but study data were not available for the Teri 1997 study.

2. Table of behavioural activation (BA) therapies.

| Participants | Intervention and control conditions | Outcomes | |

| Kurz 2012 | Mild AD (ICD‐10; MMSE ≥ 21) N = 201; male (M) 113; female (F) 88 Mean age = 73.7 Mean MMSE = 25.1 Mean GDS‐30 = 8.9 |

BA: aimed at facilitating daily structuring, activity planning, resuming former activities based on individual goals, and mobilising support 12 weekly 1‐hour sessions over 12 weeks Control: site‐specific standard medical management for early dementia |

1. Function (Bayer Activities of Daily Living Scale; Hindmarch 1998, Aachen Functional Item Inventory; Böcker 2007) 2. Quality of life (DEMQOL; Smith 2005) 3. Depression (GDS‐30; Yesavage 1983) 4. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI; Cummings 1994) 5. Caregiver depression (BDI; Beck 1961) 6. Caregiver burden (ZBI; Zarit 1980) 7. Memory (Wechsler Memory Scale Revised Logical Memory; Wechsler 1987) 8. Attention (Trail Making Test (TMT); Reitan 1958) 9. Verbal fluency (Regensburg Word Fluency Test; Aschenbrenner 2000) 10. Cognition (MMSE; Folstein 1975) |

| Lai 2020 | Mild and moderate dementia (ICD‐10; MoCA ≤ 21) N = 100; M52; F48 Mean age = 69.7 Mean MoCA = 18.1 |

BA: activity scheduling of pleasant activities in line with life values and goals, improving communication, monitoring of mood, and reassessment 10 weekly sessions provided over 10 weeks with weekly telephone follow‐ups Control: dementia care education over 10 weeks provided weekly |

1. Caregiver burden (ZBI; Zarit 1980) 2. Problem behaviours (Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist; Teri 1992) 3. Caregiving time (Caregiver Activity Survey; Prince 2004) 4. Participant quality of life (Quality of Life‐Alzheimer’s Disease; Logsdon 1999) |

| Lichtenberg 2005 | Mild to moderate dementia N = 20; M2; F18 Mean age = 84.9 Mean MMSE = 14.2 Mean GDS‐15 = 4.0 |

BA: introduction to BA, pleasant‐event scheduling, mood monitoring, and relaxation strategies Three weekly sessions lasting 20 to 30 minutes each over 3 months Control: usual care comprised of regular activities taking place within the home |

1. Depression (GDS; Yesavage 1983, CSDD; Alexopoulos 1988) 2. Behavioural symptoms (Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer's Disease; Reisberg 1987) |

| Lu 2016 | MCI (Albert 2011 et al. criteria) N = 40; M23; F17 Mean age = 73.8 38% scored ≥ 5 on PHQ‐9 |

BA: increasing meaningful activity through planning, addressing barriers to engagement, problem‐solving, and learning strategies for living with MCI Six biweekly 1‐hour sessions (2 in‐person and 4 telephone sessions) over 3 months Control: received educational brochure describing MCI, and opportunities to answer questions through biweekly follow‐up phone calls |

1. Congruence in function (Dementia Deficits Scale; Snow 2004) 2. Sense of confidence (Nowotny Confidence Subscale of the Nowotny Hope Scale; Nowotny 1989) 3. Meaningful activity (Canadian Occupational Performance Measure; Keihofner 2002) 4. Depression (PHQ‐9; Kroenke 2001) 5. Communication (Communication and Affective Expression Subscales of the Family Assessment Device; Miller 1985) 6. Function (Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study – Activities of Daily Living Inventory; Galasko 1997) 7. Life satisfaction (Life Satisfaction Index; Barrett 2006) 8. Carer depression (PHQ‐9; Kroenke 2001) 9. Caregiver outcomes (Bakas Caregiving Outcomes Scale; Bakas 2006) |

| Orgeta 2019 | Mild dementia (NINCDS‐ADRDA; scoring ≥ 18 on the MMSE) N = 63; M28; F35 Mean age = 80.4 Mean MMSE = 24.5 Mean CSDD = 7.2 |

BA: introduction to BA, pleasant‐event scheduling based on individuals' life values and preferences, through addressing barriers and practising relaxation strategies 8 weekly sessions lasting 90 minutes over 12 weeks Control: treatment as usual in line with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines |

1. Function (Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale; Bucks 1996) 2. Meaningful activity (Meaningful and Enjoyable Activities Scale; Tuijt 2020) 3. Depression (CSDD; Alexopoulos 1988) 4. Generic and dementia‐specific quality of life (EQ‐5D; EuroQoL 1990, DEMQOL; Smith 2005) 5. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI; Cummings 1994) 6. Caregiver depression and anxiety (HADS; Zigmond 1983) 7. Caregiver quality of life (EQ‐5D; EuroQoL 1990, 12‐Item Short Form Health Survey; Ware 1996) |

| Rovner 2018 | Amnestic multiple‐ or single‐domain MCI (National Institute on Aging ‐ Alzheimer's Association) N = 221; M46; F175 Mean age = 75.8 Mean MMSE = 25.7 Mean GDS‐15 = 3.5 |

BA: increasing cognitive, physical, and/or social activity, in line with personal values, focusing on enhancement of treatment goals, and review of barriers Five in‐home 60‐minute sessions over 4 months and 6 in‐home 60‐minute follow‐up maintenance sessions over the next 20 months Control: supportive control intervention focusing on personal expression, conveying empathy, and optimism |

1. Cognition (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised; Benedict 1998, National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set; Weintraub 2009, MMSE; Folstein 1975) 2. Function (University of California San Diego Performance‐Based Skills Assessment; Gomar 2011) 3. Activities (Florida Cognitive Activities Scale; Dotson 2008, US Health Interview Survey; Sturman 2005) 4. Depression (GDS‐15; Yesavage 1983) |

| Teri 1997 | Mild to moderate dementia (NINCDS‐ADRDA; diagnosis of major or minor depression; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; HDRS ≥ 10) N = 33; M11; F22; 4‐arm RCT total N = 72 Mean age = 76.1 Mean MMSE = 16.3 Mean HDRS = 15.2 |

BA: pleasant‐event scheduling, mood monitoring, and modifying problem behaviours (behavioural and psychological symptoms) by addressing barriers and developing plans to maintain pleasant events for the future 9 weekly sessions lasting 60 minutes each over 9 weeks Control: treatment as usual incorporating typical advice and support services available in the community (and a separate waiting‐list control group) |

1. Depression (HDRS; Hamilton 1960, CSDD; Alexopoulos 1988, BDI; Beck 1961) 2. Cognition (MMSE; Folstein 1975, Dementia Rating Scale; Coblentz 1973) 3. Function (Record of Independent Living; Weintraub 1982; data not provided) 4. Caregiver depression (HDRS; Hamilton 1960) 5. Caregiver burden (ZBI; Zarit 1980; data not provided) |

| Travers 2017 | Mild to moderate dementia (SMMSE ≥ 10; GDS‐12R ≥ 4) N = 18; M2; F16 Mean age = 86.3 Mean SMMSE = 17.8 Mean GDS‐12R = 4.5 |

BA: pleasant‐event scheduling (scheduling of enjoyable activities), by developing individual plans, identifying barriers to engagement, and problem‐solving Sessions lasted 45 minutes over 8 weeks Control: receiving a walking‐and‐talking intervention (supervised social walking) for 30 minutes weekly |

1. Depression (GDS‐12R; Yesavage 1983) 2. Quality of life (Quality of Life in Alzheimer's Disease in Nursing Homes; Edelman 2005) |

BA: behavioural activation; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CSDD: Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; DEMQOL: Dementia Quality of Life Instrument; EQ‐5D: EuroQoL‐5 Dimension; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; ICD‐10: International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; MMSE: Mini‐Mental State Examination; MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NINCDS‐ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke ‐ Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; PHQ‐9: Patient Health Questionnaire‐9; SMMSE: Standardized Mini‐Mental State Examination; ZBI: Zarit Burden Interview

Problem‐solving therapy (PST)

Participants and setting

Kiosses 2010 and Kiosses 2015 recruited older people with major depression, advanced cognitive impairment, and disability living in the community in the USA. Teri 1997 included people with mild to moderate dementia living in the community, also in the USA. In this study, all participants met RDC and DSM‐III‐R criteria for major or minor depressive disorder and had a HDRS score of at least 10. Kiosses 2010 recruited people with a diagnosis of unipolar major depressive disorder based on Structured Clinical Interview for DMS (SCID) and Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV (SCID‐IV) criteria, and who had a score of 17 or higher on the HDRS. In the study by Kiosses 2015, all participants had non‐psychotic, unipolar major depressive disorder based on Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV‐TR (SCID‐R) criteria, and scored 17 or higher on the Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Intervention and control groups

Kiosses 2010 and Kiosses 2015 evaluated Problem Adaptation Therapy, aimed at reducing depression and disability versus a home‐delivered supportive control intervention focusing on empathic listening, encouragement, and use of reflection and emotion processing. Teri 1997 evaluated problem‐solving therapy versus usual care (consisting of advice and information about support services available and a separate waiting list‐control group).

Outcomes

Both the Kiosses 2010 and Kiosses 2015 studies measured depression at the end of 12‐week interventions, and Teri 1997 at the end of a 10‐week intervention. None of the PST studies measured anxiety as an outcome. We present the outcomes assessed across all PST studies (Kiosses 2010; Kiosses 2015; Teri 1997), the details of participants recruited, and the interventions evaluated, in Table 5. Teri 1997 measured persistence of effects at six months but data were not available.

3. Table of problem‐solving therapies (PST).

| Participants | Intervention and control conditions | Outcomes | |

| Kiosses 2010 | Major depression, cognitive impairment, and disability (major depression: SCID‐IV; ≥ 17 HDRS; cognitive impairment defined by < 2 standard deviations of mean of age‐matched controls on the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS; ≤ 30), or ≤ 18 on the Stroop Color and Word Test) N = 30; male (M) 9; female (F) 21 Mean age = 79.4 Mean MMSE = 26.6 Mean HDRS = 21.9 |

PST: aimed at reducing participants' depression and disability by facilitating problem‐solving, adaptive functioning, and engagement in pleasurable activities Weekly individual sessions over 12 weeks Control: home‐delivered supportive intervention consisting of empathic listening, reflection, emotional processing, and encouragement |

1. Depression (HDRS; Hamilton 1960) 2. Disability (Sheehan Disability Scale; Leon 1997) |

| Kiosses 2015 | Major depression, advanced cognitive impairment and disability (major depression: SCID‐R, mild cognitive deficits ≤ 7 on the DRS and ≥ 17 MADRS) N = 74; M23; F51 Mean age = 80.9 Mean DRS = 118.5 Mean MADRS = 21.2 |

PST: aimed at reducing the impact of negative emotions using a problem‐solving approach via specific tools Weekly individual home‐based sessions over 12 weeks Control: home‐delivered supportive intervention consisting of empathic listening, reflection, emotional processing, and encouragement |

1. Depression (MADRS; Montgomery 1979) 2. Disability (World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0; Ustun 2000) |

| Teri 1997 | Mild to moderate dementia (National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke ‐ Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association; diagnosis of major or minor depression; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; HDRS ≥ 10) N = 39; M27; F12; 4‐arm RCT total N = 72 Mean age = 77.6 Mean MMSE = 16.8 Mean HDRS = 15.2 |

PST: problem‐solving situations of concern with the main focus being problem‐solving participant depression behaviours of specific concern to carers Weekly individual sessions of 60 minutes each over 9 weeks Control: treatment as usual incorporating typical advice, and support services available in the community (and a separate waiting‐list control group) |

1. Depression (HDRS; Hamilton 1960, Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; Alexopoulos 1988, Beck Depression Inventory; Beck 1961) 2. Cognition (MMSE; Folstein 1975, DRS; Coblentz 1973) 3. Function (Record of Independent Living; Weintraub 1982; data not provided) 4. Caregiver depression (HDRS; Hamilton 1960) 5. Caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Interview; Zarit 1980; data not provided) |

DRS: Dementia Rating Scale; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS: Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; MMSE: Mini‐Mental State Examination; PST: problem‐solving therapy; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM‐IV

Supportive and counselling therapies

Participants and setting

Bruvik 2013 recruited people living with mild dementia in the community in Norway. The studies by Jha 2013, Marshall 2015, and Quinn 2016 recruited people living with dementia in their own home in the UK. Both the Koivisto 2016 and the Laakkonen 2016 studies recruited people living with dementia in Finland. Logsdon 2010 recruited people living with mild to moderate dementia in the community in the USA. Nordheim 2019 recruited people living with mild to moderate dementia in community settings in Germany. Tappen 2009 recruited people living with dementia in a long‐term care facility in the USA, and Waldorff 2012 recruited community‐dwelling people living with mild AD in Denmark. Young 2014 recruited people living with mild dementia in China.

Intervention and control groups

Bruvik 2013 evaluated a counselling intervention versus a control condition comprised of receiving information about available services or support as required. Jha 2013 evaluated a well‐being recovery‐orientated counselling intervention versus a fixed package of care consisting of monthly visits for six months. Koivisto 2016 evaluated enhanced counselling support versus basic information about AD and access to regular services. Laakkonen 2016 evaluated a supportive therapy intervention based on psychosocial rehabilitation versus usual care which comprised regular health and social care services and advice about nutrition and exercise. Logsdon 2010 evaluated the effectiveness of structured support groups versus a waiting‐list control condition comprised of educational materials about dementia and support services available. Marshall 2015 evaluated a supportive therapy intervention known as Living Well with Dementia, incorporating psycho‐education about dementia, versus usual care. Nordheim 2019 evaluated couples‐based counselling versus standard care. Quinn 2016 evaluated a supportive group therapy intervention incorporating information about dementia versus TAU comprised of access to routine memory clinic services. Tappen 2009 assessed a counselling intervention adapted for people living with dementia in care homes versus usual care provided by staff at the long‐term care facility. Waldorff 2012 assessed the effectiveness of a counselling intervention versus information about local support available. Young 2014 evaluated a supportive therapy intervention incorporating provision of information and support about dementia versus standardised educational written materials about dementia.

Outcomes

All studies except Laakkonen 2016 measured depression, and only the study by Quinn 2016 measured anxiety as an outcome. We present the outcomes assessed across all supportive and counselling intervention studies (Bruvik 2013; Jha 2013; Koivisto 2016; Laakkonen 2016; Logsdon 2010; Marshall 2015; Nordheim 2019; Quinn 2016; Tappen 2009; Waldorff 2012; Young 2014), the details of participants recruited, and the interventions evaluated, in Table 6. Marshall 2015 assessed persistence of effects at 22 weeks, and Quinn 2016 assessed persistence of effects at six months post‐intervention (but data were not reported in a form that could be included in a meta‐analysis). The study by Waldorff 2012 examined persistence of effects of the intervention at three years.

4. Table of supportive and counselling therapies.

| Participants | Intervention and control conditions | Outcomes | |

| Bruvik 2013 | Mild dementia (ICD‐10) N = 230; male (M) 107; female (F) 123 Mean age = 78.4 Mean MMSE = 21.2 Mean CSDD = 8.0 |

CI: individual counselling sessions addressing unmet needs through problem‐solving, educational sessions about dementia, and social support meetings Five individual counselling sessions, one educational session, and 6 social support group meetings of 1 hour each over 12 months Control: received information about available services in local authority and were free to seek additional support |

1. Depression (CSDD; Alexopoulos 1988) 2. Carer depression (GDS; Yesavage 1983) |

| Jha 2013 | MCI or mild dementia (ICD‐10) N = 48; M16; F32 Mean age = 78.7 Mean MMSE = 22.0 Mean CSDD = 6.6 |

CI: well‐being and recovery orientated counselling intervention consisting of pre‐diagnostic counselling, a well‐being assessment, feedback primarily aimed at improving well‐being, post‐diagnostic counselling, and support Monthly visits for 6 months of 1 hour each Control: offered a fixed package of care of monthly visits for 6 months without being assessed for well‐being |

1. Well‐being (WHO 5‐item Well‐Being Index; Heun 1999) 2. Cognition (MMSE; Folstein 1975) 3. Depression (CSDD; Alexopoulos 1988) 4. Quality of life (EQ5D; EuroQoL 1990) 5. Caregiver burden (Zarit Burden Interview; Zarit 1980) |

| Koivisto 2016 | Mild AD (NINCDS‐ADRDA) N = 236; M115; F121 Mean age = 75.6 Mean MMSE = 21.5 Mean BDI = 10.7 |

CI: individual counselling, education, and both individual and support groups primarily aimed at enhancing knowledge, reducing social isolation, and support function Offered over 4 courses (total of 16 days) over 2 years Control: participated in annual follow‐up visits, and received regular healthcare services |

1. Institutionalisation 2. Dementia severity (CDR; Morris 1993) 3. Cognition (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease neuropsychological battery; Chandler 2005, MMSE; Folstein 1975) 4. Function (ADCS‐ADL; Galasko 1997) 5. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI; Cummings 1994) 6. Depression (BDI; Beck 1961) 7. Participant quality of life (QoL‐AD; Logsdon 1999) 8. Carer depression (BDI; Beck 1961) 9. Carer sense of coherence (Sense of Coherence Scale; Antonovsky 1987) 10. General physical and mental health for carers (GHQ; Goldberg 1985) 11. Carer quality of life (15D instrument; Sintonen 2001) |

| Laakkonen 2016 | Mild to moderate dementia (Finnish National Guidelines) N = 136; M85; F51 Mean age = 77.0 Mean MMSE = 20.8 |

ST: structured psychosocial rehabilitation program aimed at maintaining self‐efficacy, provision of social support, psycho‐education, use of resources, and problem‐solving skills in everyday life 4‐hour group sessions once a week over 8 weeks Control: usual care consisting of regular health and social services, and provision of advice on nutrition and exercise |

1. Quality of life (15D instrument; Sintonen 2001) 2. Cognition (CDR; Hughes 1982, Verbal Fluency; Morris 1989, Clock Drawing Test; Sunderland 1989) 3. Carer quality of life (RAND‐36 Item Health Survey; Hays 2001) 4. Carer sense of competence (SCQ; Vernooij‐Dassen 1996) 5. Carer mastery (Pearlin Mastery Scale; Pearlin 1978) |

| Logsdon 2010 | Mild to moderate dementia (diagnosed by physician) N = 142; M72; F70 Mean age = 74.9 Mean MMSE = 23.4 Mean GDS = 5.3 |

ST: structured support groups aimed at improving quality of life, sharing experiences, reducing feelings of isolation, and providing assistance with long‐term care planning Weekly 90‐minute sessions, taking place over 9 weeks Control: waiting‐list condition where people received written educational materials about dementia and AD, and services available |

1. Quality of life (QoL‐AD; Logsdon 1999, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36; Stewart 1988) 2. Depression (GDS; Yesavage 1983) 3. Family communication (Family Assessment Measure; Skinner 1983) 4. Perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale; Cohen 1983) 5. Self‐efficacy (Self Efficacy Scale; Seeman 1996) 6. Caregiver reactions to problem behaviours (Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist; Teri 1992) |

| Marshall 2015 | Mild dementia (NINCDS‐ADRDA) N = 58; M25; F33 Mean age = 75.6 Mean MMSE = 23.0 Mean CSDD = 6.2 |

ST: psycho‐education provided in a group setting aimed at improving quality of life, provision of information about dementia, coping with stress, and living as well as you can Weekly 75‐minute sessions over 10 weeks Control: a waiting‐list condition in which participants received usual care |

1. Quality of life (QoL‐AD; Logsdon 1999) 2. Depression (CSDD; Alexopoulos 1988) 3. Self‐esteem (RSES; Rosenberg 1965) 4. Cognition (MMSE; Folstein 1975) 5. Carer general health (GHQ; Goldberg 1985) |

| Nordheim 2019 | Mild to moderate dementia (National Institute on Aging ‐ Alzheimer's Association) N = 108; M66; F42 Mean age = 85.0 Mean MMSE = 22.8 Mean GDS‐15 = 5.5 |