Abstract

Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumors (ES/PNETs) are rare tumors that belong to a family of round-cell neuroectodermally derived tumors, and their optimal treatment remains a great challenge. This study presented a case of ES/PNET, arising in the esophagus of a 21-year-old female patient presented with progressive dysphagia. Computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasonography showed a well-defined, submucosal solid mass in the superthoracic esophagus. The accurate diagnosis after surgery was obtained through immunohistochemistry and genetic studies, namely the CD99 immunopositivity as well as the EWSR1/FLI1 gene rearrangement associated with t(11;22)(q24;q12) in tumor cells. The patient underwent localized tumor resection followed by chemotherapy and chest radiotherapy. The patient is doing well with no evidence of tumor recurrence or metastasis 18 months after surgery. Although the esophagus is a rare site for ES/pPNET, we can speculate that the treatment protocol of ES/pPNET should include multi-agent chemotherapy, surgery, and local radiotherapy in order to improve the prognosis based on our report.

Keywords: Extraosseous Ewing sarcoma, Primitive neuroectodermal tumor, Esophagus, Diagnosis, Treatment

Introduction

Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor (ES/PNET) is a family of small round-cell neuroectodermally derived tumors, which are overlapping entities with the same histological origin and different degrees of neuroectodermal differentiation, i.e., PNET has neuroectodermal differentiation, and ES is lacking [1]. ES/PNET is often derived from the bone and soft tissue and is common in young people, with an annual incidence rate of 2.9 cases per million from birth up until the age of 20 years [2]. Histologically, PNETs share the morphologic appearance on light microscopy of small, round, darkly staining cells, with variable differentiation. Furthermore, PNET is often aggressive and portend a poor prognosis [2]. Due to variable histology and a wide range of anatomic origin, diagnosis of PNET can be challenging and depends on a combination of a thorough history, light microscopy, and immunohistochemistry, with genetic abnormity being the most prominent feature [3]. ES/PNETs have conventionally been divided into central (cPNET) and peripheral (pPNET) based on their neural tissue features [4]. cPNETs are central nervous system embryonal tumors, most commonly arising from the supratentorial parenchyma, which does not exhibit the abnormality of the EWSR1 gene or expresses MIC2 gene and thus can be differentiated from ES/pPNET [5]. However, the 2016 WHO classification of primary CNS tumors deleted the term CNS-PNET, and those previously called “cPNET” has been reclassified into more detailed diagnostic entities under the umbrella of “embryonal tumors of CNS.” On the other hand, pPNETs arise from peripheral nerves or from soft tissues and are conventionally considered as part of the larger ES family of tumors due to their cytogenetic and histopathologic similarity [3]. We herein report a case of PNET presenting as a polypoid esophageal mass in an adult patient.

Case Presentation

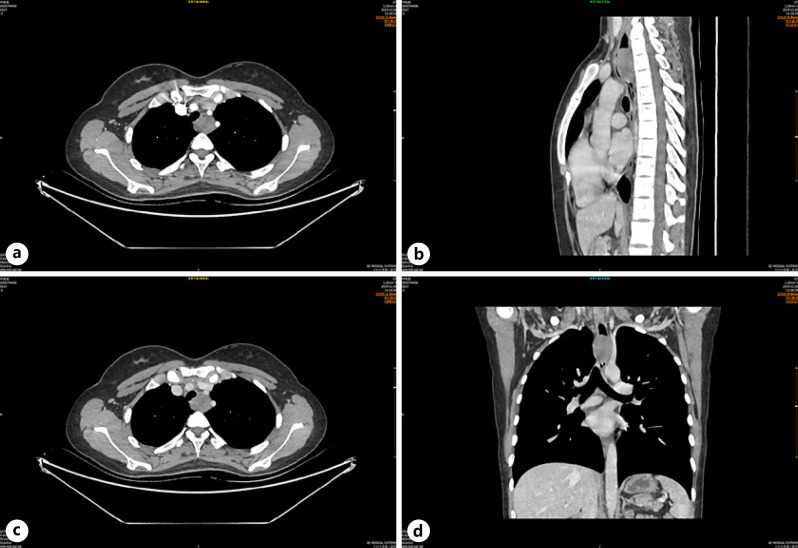

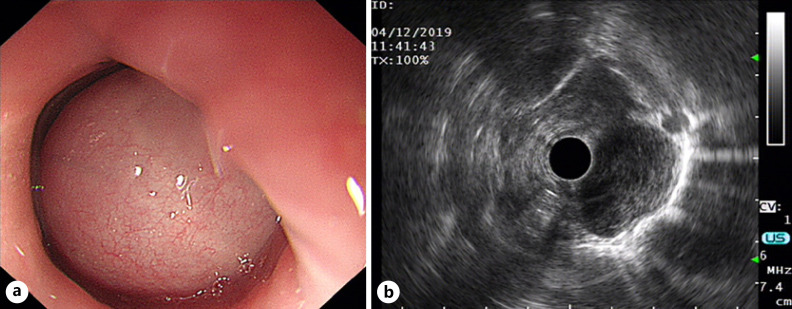

The 21-year-old female patient was admitted to the thoracic surgery department of our hospital due to progressive dysphagia accompanied by nausea and vomiting after meal consumption for 2 months. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed a spherical soft tissue mass in the upper thoracic esophagus, with obvious narrowing of the lumen (Fig. 1). The size of the lesion was about 30 × 26 mm, which was mild uniform enhancement. No obvious enlarged lymph nodes were found in the mediastinum. Abdominal CT, neck ultrasound, brain MRI, and bone ECT revealed no obvious abnormalities. Flexible esophagoscopy confirmed a large polypoid mass 18 cm away from the incisor teeth, completely obstructing the esophagus within the intact mucosal surface, presenting with formation of mucosal bridges (Fig. 2a). Endoscopic ultrasonography of esophagus showed that the lesion arose from the esophageal muscularis propria with a smooth and continuous adventitia (Fig. 2b). The primary clinical diagnosis was that of submucosal lesions of the upper thoracic esophagus, possibly a leiomyoma.

Fig. 1.

Axial (a–c), coronal (c, d), and sagittal (b, d) CT showing a well-defined, spherical solid mass in the upper thoracic esophagus presenting with mild uniform enhancement, which caused proximal esophagus dilatation.

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic ultrasonography of the esophagus before operation. a Hemispherical protruding lesion in the upper thoracic esophagus with an intact mucosal surface, presented with the formation of mucosal bridges. b Lesion originated from the esophageal muscularis propria, and the adventitia is smooth and continuous.

Thoracoscopic esophageal lesion resection under general intravenous anesthesia after completing all investigation was done. A 2.9 × 2.1 × 3.0 cm mass in the upper thoracic esophagus was seen during the operation. Taking precautions to avoid any damage, the muscle layer was carefully separated, and the mucosa was carefully peeled off. After complete tumor removal, the muscle layer defect was about 3 cm long, and the mucosal layer was damaged in three spots due to dense adhesions. The mucosal layer was repaired thoracoscopically, and the stumping muscle layer was pulled to the middle for an end-to-end anastomotic procedure, which was covered and sutured using the surrounding pleura.

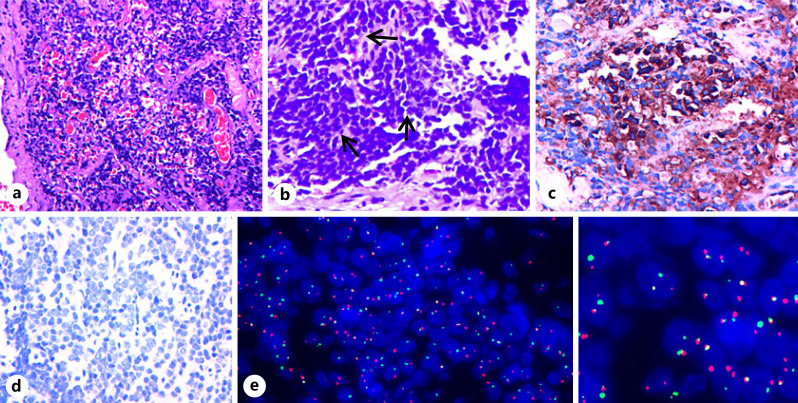

The resected esophageal mass was submitted to undergo histology, immunochemistry, and genetic studies. Histologically, the tumor consisted of a markedly cellular tissue with a trabecular growth pattern accompanied by hemorrhage on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Fig. 3a). In addition, the classical Homer-Wright rosettes were also seen (Fig. 3b). Tumor cells had small, uniform, mildly atypical nuclei with granular chromatin and small amounts of cytoplasm (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

The pathological and FISH results of pPNET of the upper thoracic esophagus. a H&E stain showed a uniform population of small round blue cells with markedly vesicular nuclei and finely dispersed chromatin, accompanied by some remarkable hemorrhage. b Homer-Wright rosettes (arrow) were seen on H&E. c, d Immunohistochemistry of CD99 (c) showed a diffuse strong membrane staining, but synaptophysin (d) was negative in the tumor cells. e FISH by the EWSR1/FLI1 Fusion Translocation t(11;22) Probe illustrating the EWSR1/FLI1 gene rearrangement associated with t(11;22)(q24;q12). Note: green signal (e) is GSP EWSR1, and red signal (e) is GSP FLI1 (original magnification ×20 (a), ×40 (b–d)). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Immunoperoxidase stains were performed on a Ventana NEXES Automated Immunohistochemistry System (Fuzhou Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd., Fuzhou, China). CD99 (clone O13; Maixin) (Fig. 3c) and P63 (clone MX 013; Maixin) were positive in the tumor cells. Vimentin (clone MX 034; Maixin) was less positive. Furthermore, tumor cells did not stain for synaptophysin (clone SP 11; Maixin), pan-cytokeratin (clone AE1/AE3; Maixin), and CD56 (clone 123C3. D5; Maixin) (Fig. 3d). Ki-67 was reactive in approximately 55% of the tumor cells. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections were prepared, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed with the EWSR1/FLI1 Fusion Translocation t(11;22) Probe (Guangzhou LBP Medicine Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China), and two hundred interphase cells were examined. The patient's sample was positive for EWS/FLI1 transcripts associated with t(11;22)(q24;q12) (Fig. 3e), which signal modes are as follows: 1 G1R1F 37.0%, 2 G1R1F 10.0%, 2 G2R1F 4.0%, 1 G1F 10.0%, 2 G1F 10.0%, 1R1F 7.5%, 1R2F 5.0%, 1 G2F 7.5%, and 1 G1R2F 9.0%.

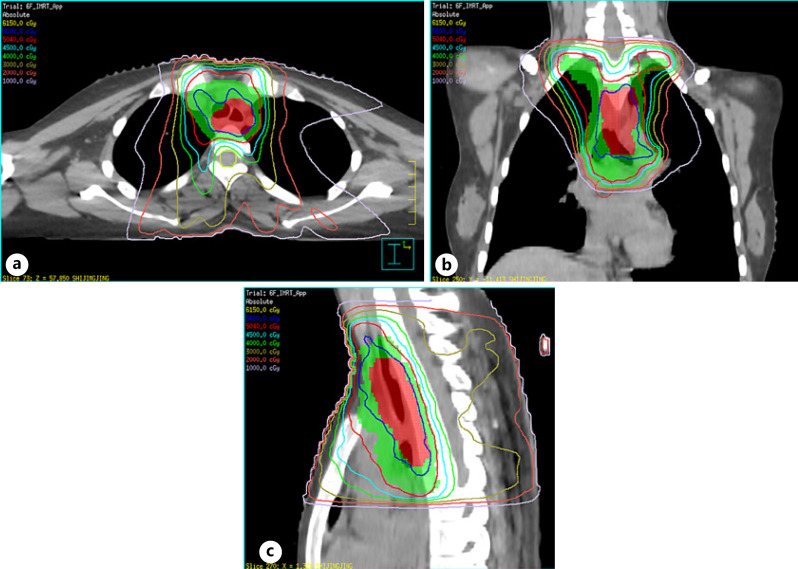

After 2 months after the operation, the patient received 2 cycles of EP (etoposide/cisplatin) chemotherapy, followed by chest radiotherapy and concurrent EP regimen chemotherapy for 2 cycles and then continued to receive 2 cycles of EP regimen adjuvant chemotherapy. Chest radiation was delivered using intensity-modulated radiation therapy (Fig. 4a-c) as follows: the planning gross tumor volume of the tumor bed (TB) (PGTVtb) and planning target volume (PTV) were administered using 56 and 50.4 Gy in 28 daily fractions of 1.8–2.0 Gy, respectively. The clinical target volume (CTV) depended on the location of the primary tumor and was irradiated using involved-field radiotherapy. The CTV included GTVtb with a radial margin of 0.5–1.0 cm and a longitudinal margin of 3 cm. The CTV and GTVtb with a margin of 0.5 cm in three dimensions formed the PTV and PGTVtb, respectively. Chemotherapy consisted of cisplatin 25 mg/m2 and etoposide 100 mg/m2 per day on days 1 through 3 every 21 days for up to six cycles.

Fig. 4.

Computed dosimetric reconstruction images used for IMRT. a–c PGTVtb (red color wash image) and PTV (green color wash image) were administered 56 Gy (shown in blue isodose line) and 50.4 Gy (shown in red isodose line), respectively. Note: GTVtb refers to gross tumor volume of TB, and CTV refers to GTVtb with a radial margin of 0.5–1.0 cm and a longitudinal margin of 3 cm; CTV and GTVtb with a margin of 0.5 cm in three dimensions formed the PTV and PGTVtb. IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; PGTVtb, planning gross tumor volume of the tumor bed; PTV, planning target volume.

The patient has been followed up regularly for one and half years after surgery and for 1 year after adjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy including clinical examination, ECT, chest CT, and gastroscopy. No obvious signs of recurrence or metastasis were found, and the patient's general condition was satisfactory.

Discussion

ES/pPNET most commonly arises from soft tissues and bones [6]. As far as soft tissue origin is concerned, the thoracoabdominal region is the most predominant location for primary disease followed by even distributions in other soft tissue locations, such as the extremities [6]. To the best of our knowledge, there are approximately 7 cases reported in literature searches of patients who suffered from esophageal PNETs (Table 1) [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. However, our understanding of appropriate diagnostic methods and efficient treatment strategies for esophageal PNET is still insufficient. In this report, we describe in detail a case of pPNETs in an adult who presented with progressive dysphagia. During the primary assessment, the patient had a spherical mass in the superior thoracic esophageal region, which had the imaging characteristics of esophageal submucosal tumors that prohibited clinicians from acquiring an accurate diagnosis prior to surgery. The patient was initially and clinically diagnosed with esophageal leiomyoma before surgery. Based on radiology and esophagoscopy, the differential diagnosis should have included leiomyomas and malignant mesenchymal neoplasms of the esophagus. Esophageal leiomyomas are the most common benign tumors of the esophagus. Malignant mesenchymal neoplasms of the esophagus are unusual, the commonest of which are gastrointestinal stromal tumors and leiomyosarcomas.

Table 1.

Characteristics of previously reported cases of the Ewing family of tumors in the esophagus

| Reference | Age/sex | Tumor site | Tumor size, cm | Immunohistochemistry (+) | Immunohistochemistry weakly or focally (+) | Immunohistochemistry (−) | Ancillary diagnostic tests schedule | Therapeutic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inaba et al. [7] | 32/F | Middle esophagus | − | − | − | − | − | Surgery + chemotherapy | |

| Maesawa et al. [8] | 56/M | Lower esophagus | 3.4 × 2.0 × 1.8 HMB45 and p53 | CD99, vimentin, actin, α-SMA, HMA, and S100 | − | CK, AE1/AE3, EMA, and LCA FISH: EWSRl(ex10) | RT-PCR: EWSR1/ERG Desmin, NSE, and CgA | +Surgery ERG (ex6) | |

| Cabarcos Ortiz Barrón et al. [9] | 21/M | Middle esophagus | 7.4 × 2.5 | Not performed | Not performed FISH: t(11;22) (q24;q12) | Not performed | RT-PCR: EWS/FLI1 | Not performed | |

| Johnson et al. [10] | 44/F | Upper esophagus | 5.0 cm in diameter p53 and cyclin D1 | CD99, ß-catenin, Ki-67 (5%), Vimentin, and NSE | S100, FLI1 PR, CHR, SYN, c-kit, and SMA | CK, AE1/AE3, inhibin, GFAP EWSR1 locus in band 22q12 EMA, CAM5.2, and neurofilament MMelanA, HMB45, and tyrosinase | FISH: rearrangement of RT-PCR: EWS/FLI1 | Chemotherapy | |

| Tarazona et al. [11] | 25/M | Upper esophagus | 4.1 × 6.8 | Ki-67 + 60%, c-kit | CD99 and FLI1 | − | − | RT-PCR: EWSR1/ERG FISH: EWSRl(ex7)-ERG(ex6] | Chemotherapy + radiotherapy EWSRl(ex7)-ERG(ex7] |

| Blas Jhon et al. [12] | 49/F | Middle esophagus | 5.0 × 2.7 × 1.0 MIB-1 + 100% CK, SYN, and AE3 | CD99, vimentin, and CAM5.2 | CK and AE1/AE3 | − | FIFH: reciprocal translocation of EWSR1 t(22q12] | Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | |

| Wang et al. [13] | 36/F | Cervical esophagus | 9.0 × 6.7 × 4.7 NS and ERG | CD99 and FLI1 | S100 and Ki-67 | LCA, SYN, Cg A, and HMB45 | FISH: rearrangement of EWSR1 Other hematopoietic markers on chromosome t(11;22) (q24;q12) | Surgery + chemotherapy + radiotherapy | |

| Current case | 21/F | Upper esophagus | 2.9 × 2.1 × 3.0 | Ki-67 + 55% | Vimentin | SYN, CKP, CK7, CD56, CgA CD99, and P63 | RT-PCR: EWSR1/FLI1 CD68, TTF-1, EMA, CK5/6, CD3 CD30, CD43, CD20, Pax-5, MPO, and CD34 | Surgery + chemotherapy + radiotherapy |

(+), positive; (−), negative; −, not described; RT-PCR, reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; EWS, Ewing sarcoma; CK, cytokeratin; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; EMA, epithelial membrane antigen; SMA, smooth muscle actin; SYN, synaptophysin; CHR, chromogranin; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein.

ES/pPNET grossly appears as a lobulated mass, featuring extensive necrosis and/or with hemorrhage. Microscopically, the tumor is uniformly composed of closely packed small round cells, showing vesicular nuclei with finely dispersed chromatin and scant cytoplasm. A variable number of rosettes can be detected and are traditionally interpreted as evidence of neuroectodermal differentiation. The classical Homer-Wright rosette as well as remarkable hemorrhage was observed in our case, but obvious necrosis was insignificant. Immunohistochemically, CD99 (a cell surface glycoprotein and gene product of MIC 2) is highly sensitive to pPNET but not specific because it can be present in practically all patients with ES [1]. In view of strong CD99 membrane immunopositivity being expressed within a broad variety of mesenchymal tumors, it needs to be evaluated combining with morphology. More importantly, considering its remarkable sensitivity, CD99 immunonegativity would strongly rule out a diagnosis of ES. In addition, it has been reported that the immunopositivity rate for CD99 is more than 95% in patients with pPNET [14]. In our case, the tumor cells were strongly positive for CD99. Although ES/pPNET was originally diagnosed by the use of a microscope and immunohistochemistry, more importance has been based on genetic confirmation of this type of tumors in the past 2 decades. Detection of genetic changes by cytogenetic and/or molecular genetic methods is unique for ES/PNET and is increasingly considered as the “gold standard” for diagnosis [15]. The genetic abnormality of ES/pPNET is characterized by the fusion of the EWSR1 gene (a member along with FUS and TAF15 of the FET family that contains an RNA-binding domain) on chromosome 22q12 with other genes of the ETS (avian erythroblastosis virus transforming sequence) family (FLI1, ERG, ETV1, ETV4, and FEV), most commonly with the FLI1 gene on chromosome 11q24 forming a t(11;22)(q24;q12) translocation [5, 16], which is present in 90–95% of cases, and being responsible for the dysregulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis [17]. It has been also reported that the characteristic t(11;22)(q24;q12) translocation rate was as high as 88% in histologically and immunohistochemically diagnosed cases of ES, while 12% of these cases lacked t(11;22)(q24;q12) translocation, which suggests the presence of some variant translocations that involves the EWSR1 gene on 22q12 chromosomal region, such as t(21;22)(q22;q12), t(7;22)(p22;q12), or t(2;22)(q33;q12), which result in different fusion products, such as EWSR1-ERG, EWSR1-ETV1, or EWSR1-FEV [18]. ES/pPNET genetic abnormality can be detected with FISH and reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). However, FISH is found to be more sensitive and specific compared to RT-PCR on paraffin-embedded tissue sections [18]. In this case, we reported that genetic abnormality was detected using the FISH method. EWS/FLI1 transcripts associated with t(11;22)(q24;q12) for surgical specimen was positive, confirming the diagnosis.

ES/pPNET are very rare neoplasms, and optimal treatment remains challenging and often requires a multidisciplinary approach relying on surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy [19]. As for the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas, the NCCN recommends primary treatment with chemotherapy in order to downstage huge tumors in an attempt at achieving microscopic residual disease during surgery, followed by local control with surgery. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for 4–7 weeks is recommended. The preferred chemotherapeutic regimen is vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide alternating with ifosfamide and etoposide (VDC/IE), especially in patients with metastatic disease. Because most of ES/PNETs are sensitive to chemotherapy, systemic chemotherapy should be initiated first, which allows for a safer surgical approach, minimizing risk for tumor spread. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) typically consists of a combination regimen, e.g., vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and etoposide help in obtaining complete tumor resection with negative microscopic margins [20]. Additionally, studies confirmed that extraskeletal ES have more differentiated neuroectodermal component as compared to skeletal ES, which render extraskeletal ES more sensitive to radiotherapy [21]. The treatment of our patient was based on the clinical diagnosis of esophageal leiomyoma; therefore, she underwent surgical excision without preoperative biopsy results and NACT.

Based on the fact that the patient underwent localized tumor resection without radical esophagectomy, she underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with EP (etoposide/cisplatin) and radiotherapy for TB/locoregional lymph node. To date, she is doing and recovering well with no evidence of tumor recurrence or metastasis. Although the chemotherapy regimen we have chosen is debatable, clinical results are satisfactory. El Housheimi et al. [22] reported a patient with primary vulvar ES/pPNET being associated with pelvic lymph nodes metastasis. The patient first received 3 cycles of NACT with VAC, alternating with IE. PET/CT post-NACT completion revealed a complete response for the LNs in the pelvic and inguinal area, with only minor residual lesion at the vulva. Considering that the residual lesions can reach a complete resection and achieve negative margins, the patient underwent vulvar radical local excision followed by 4 additional cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with VAC/IE and radiation of the TB as well as the previously involved LN with a total dose of 54 Gy. The patient remained disease-free after 3 years. Based on the case report, we can speculate that the treatment protocol of ES/pPNET should include multi-agent chemotherapy, surgery, and local radiotherapy in some cases in order to improve the prognosis. Therefore, multimodal treatment is recommended in ES/PNET, and clinicians must carefully consider each intervention before implementation.

With regard to treatment of esophageal ES/pPNET, there still have been no uniform standardized therapeutic strategies. Wang et al. [13] reported a patient with ES/pPNET in the cervical esophagus. The patient underwent localized tumor resection and seven cycles of chemotherapy with VDC/IE followed by local radiotherapy of the neck. Nineteen months after surgery, the patient recuperated well with no evidence of tumor recurrence or metastasis. The report suggests that postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy are of great importance in improving the prognosis of esophageal PNET. To our knowledge, 7 cases of esophageal ES/pPNET have been reported in the literature to date [7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13]. The treatment strategy included surgery only, chemotherapy only, surgery combined with chemotherapy, chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy, and a combination of all three modalities. The latter and most aggressive approach has shown better results.

Method of Literature Review

For the years 1980–2021, we searched the MEDLINE database from the PubMed website, using the main terms extraosseous Ewing sarcoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, and esophagus. Further papers were derived from the retrieved articles through an analysis of the reference list. Non-English publications in the literature have not been reviewed.

Conclusion

ES/pPNET arising in the esophagus is rare, and its diagnosis relies on histology, immunochemistry, and genetic studies. The cytogenetic and molecular genetic analysis is crucial to establish the diagnosis, and the genetic abnormality in ES/pPNET is characterized by the fusion of the EWSR1 gene on chromosome 22q12 with other genes of the ETS family. ES/pPNETs are considered to have an unfavorable prognosis, and the optimal treatment remains challenging and often requires a multidisciplinary approach relying on surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. In general, postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy are of great value in improving the prognosis of esophageal ES/pPNET.

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. This case report was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Second Hospital Affiliated to Lanzhou University, approval number (2021A-609).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Sources

This research was not funded.

Author Contributions

Jie Li: writing and literature review; Pengfei Sun: writing and editing; Li Ma: writing and literature review; Xianhua Min: clinical data collecting and literature review; Binqiang Ye: imaging review; Yao Zhang: imaging review; Weiwei Ta: clinical data collecting and pathology review; Jiyun Deng: clinical data collecting; Xiangrong Cao: imaging review; and Chi Dong: pathology examination and review.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient with sincere appreciation.

References

- 1.Kumar V, Singh A, Sharma V, Kumar M. Primary intracranial dural-based Ewing sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor mimicking a meningioma: a rare tumor with review of literature. Asian J Neurosurg. 2017 Jul–Sep;12((3)):351–7. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.185060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malek A, Ziaee V, Kompani F, Moradinejad MH, Afzali N. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor, a rare cause of musculoskeletal manifestations in a child. Iran J Pediatr. 2014 Apr;24((2)):221–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel H, Fuller GN. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors, embryonal tumors, and other small cell and poorly differentiated malignant neoplasms of the central and peripheral nervous systems. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2003 Dec;7((6)):387–98. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batsakis JG, MacKay B, El-Naggar AK. Ewing's sarcoma and peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: an interim report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996 Oct;105((10)):838–43. doi: 10.1177/000348949610501014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang MJ, Whelan R, Madden J, Mulcahy Levy JM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Hankinson TC, et al. Intracranial Ewing sarcoma: four pediatric examples. Childs Nerv Syst. 2018 Mar;34((3)):441–8. doi: 10.1007/s00381-017-3684-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woeste MR, Bhutiani N, Hong YK, Shah J, Kim W, Egger M, et al. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor incidence, treatment patterns, and outcome: an analysis of the National Cancer Database. J Surg Oncol. 2020 Jul;122:1145–51. doi: 10.1002/jso.26139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inaba H, Ohta S, Nishimura T, Takamochi K, Ishida I, Etoh T, et al. An operative case of primitive neuroectodermal tumor in the posterior mediastinum. Kyobu Geka. 1998 Mar;51((3)):250–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maesawa C, Iijima S, Sato N, Yoshinori N, Suzuki M, Tarusawa M, et al. Esophageal extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma. Hum Pathol. 2002 Jan;33((1)):130–2. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.30219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabarcos Ortiz Barrón A, Cinza Sanjurjo S, Rivero Velasco C, Mariño Rozados A, Antúnez López J. Esophageal Ewing's sarcoma with tracheal invasion with presentation as asthmatic episode. Rev Clin Esp. 2007;207((6)):310–1. doi: 10.1157/13106858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson AD, Pambuccian SE, Andrade RS, Dolan MM, Aslan DL. Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the esophagus: report of a case and review of literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010 Oct;18((5)):388–93. doi: 10.1177/1066896908316903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarazona N, Navarro L, Cejalvo JM, Gambardella V, Pérez-Fidalgo JA, Sempere A, et al. Primary paraesophageal Ewing's sarcoma: an uncommon case report and literature review. Onco Targets Ther. 2015 May;8:1053–9. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S80879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blas Jhon L, Sánchez-Fayos P, Martín Relloso MJ, Calero Barón D, Porres Cubero JC. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the esophagus with metastasis in the pineal gland. Endosc Int Open. 2019 Sep;7((9)):E1163–5. doi: 10.1055/a-0977-2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang S, Zhu W, Zhang H, Yang X. Extraosseous Ewing sarcoma of the cervical esophagus: case report and literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020 Sep; doi: 10.1177/0145561320953696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahrami A, Truong LD, Ro JY. Undiferentiated tumor: true identity by immunohistochemistry. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008 Mar;132((3)):326–48. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-326-UTTIBI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller DL, Roy-Chowdhuri S, Illei P, James A, Hruban RH, Ali SZ. Primary pancreatic Ewing sarcoma: a cytomorphologic and histopathologic study of 13 cases. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2020 Nov–Dec;9((6)):502–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Bhargava R, Zheng T, Wexler L, Collins MH, Roulston D, et al. Undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas with rare EWS gene fusions: identification of a novel EWS-SP3 fusion and of additional cases with the EWS-ETV1 and EWS-FEV fusions. J Mol Diagn. 2007 Sep;9((4)):498–509. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.070053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, Ghent F, Levingston R, Scholsem M. Intracranial Ewing sarcoma: a case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2020 May;11:134. doi: 10.25259/SNI_178_2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bashir MR, Pervez S, Hashmi AA, Irfan M. Frequency of translocation t(11;22)(q24;q12) using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in histologically and immunohistochemically diagnosed cases of Ewing's sarcoma. Cureus. 2020 Aug;12((8)):e9885. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell K, Shulman D, Janeway KA, DuBois SG. Comparison of epidemiology, clinical features, and outcomes of patients with reported Ewing sarcoma and PNET over 40 years justifies current WHO classification and treatment approaches. Sarcoma. 2018 Aug;2018:1712964. doi: 10.1155/2018/1712964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutta D, Shivaprasad KS, Das RN, Ghosh S, Chowdhury S. Primitive neuroectodermal tumor of adrenal: clinical presentation and outcomes. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013 Oct–Dec;9((4)):709–11. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.126459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takenaka S, Naka N, Obata H, Joyama S, Hamada KI, Imura Y, et al. Treatment outcomes of Japanese patients with Ewing sarcoma: differences between skeletal and extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jun;46((6)):522–8. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyw032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Housheimi A, Khalil A, Khalifeh D, Berjawi G, Seoud M, Tabbarah A, et al. Primary vulvar Ewing sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor with pelvic lymph nodes metastasis: a case report and review of literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020 Oct;46((10)):2185–92. doi: 10.1111/jog.14399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.