Abstract

Objectives:

To assess management choices in patients who undergo magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/ultrasound (MRI/US) fusion-guided prostate biopsy compared to patients who undergo systematic biopsy.

Methods:

We compared men who underwent MRI/US fusion-guided prostate biopsy to those who underwent systematic 12-core biopsy from 2014 to 2016. Patient demographics and pathologic findings were reviewed. The highest grade group per case was considered for analysis.

Results:

Follow-up was available on 133 patients who underwent MRI/US targeted biopsy and 215 patients who underwent systematic biopsy. There was no difference in prebiopsy prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (10.1 ± 10.0 vs. 12.9 ± 20.5, P = 0.11) between the 2 cohorts. Patients in the MRI cohort were more likely to have had a previous prostate biopsy (P < 0.0001). Overall, more patients in the MRI cohort choose active surveillance compared to the standard cohort (49.6% vs. 24.2%, P < 0.0001), confirmed on multivariate logistic regression model adjusting for age, PSA density, prior biopsy history, race, grade group, and provider (P = 0.013). This finding held true independently for patients with grade groups 1 and 2 tumors (P = 0.02 and P = 0.005, respectively) and in a multivariate logistic regression model adjusting for grade group 1 and 2 tumors (P = 0.0051). In the standard cohort, more patients chose radiation over prostatectomy (47.2% vs. 24.4%, P < 0.0001). On multivariate analysis, race was an independent predictor of active surveillance, with African Americans less likely to undergo active surveillance.

Conclusions:

Patients who undergo MRI/US targeted biopsy are more likely to choose active surveillance over early definitive treatment compared to men diagnosed on systematic biopsy when adjusting for tumor grade, PSA density, prior biopsy history, race, and provider.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Multiparametric MRI, Grade groups, Treatment, Active surveillance

1. Introduction

For years, the standard-of-care approach for diagnosing prostate cancer has been the extended sextant biopsy, which is essentially a systematic but random tissue sampling of the prostate gland. Prostate cancer remains the only solid organ malignancy that is standardly detected through such a random approach. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/ultrasound (US) fusion-targeted prostate biopsy has recently come onto the scene in prostate cancer detection. Instead of a random sampling of the prostate gland, this technology strives to target suspicious lesions found on MRI for biopsy under real-time US guidance. Several studies have shown that MRI/US targeted biopsy detects more clinically significant prostate cancers compared to standard biopsy alone [1–6]. As such, more academic institutions and community urology groups have adopted this technique in their practice.

The introduction of any new technology needs to be evaluated in terms of its impact on patient care. The era of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening brought about an increase in the detection of prostate cancer overall. However, this increased incidence of prostate cancer led to an increase in the detection of early staged, low-grade tumors that are often considered clinically insignificant. As such, there has been a shift in philosophy among the urologic community in terms of the management of prostate cancer. Many clinicians advocate for active surveillance (AS) or minimally invasive therapies for the treatment of organ confined, low-volume, low-grade disease [7–11]. The introduction of MRI/US targeted biopsy could further impact patients in the management of prostate cancer, specifically in their selection of AS vs. definitive treatment [12]. Our study assessed management choices in patients who underwent MRI/US fusion-guided prostate biopsy compared to patients who underwent a systematic biopsy approach.

2. Methods

Our prospectively maintained prostate biopsy database was reviewed between January 2014 and December 2016. Men who underwent MRI and MRI/US fusion-guided prostate biopsy with concurrent 12-core extended-sextant transrectal ultrasound (TRUS)-guided biopsy were identified. This cohort is referred to as the “target cohort.” In addition, patients who underwent only standard 12-core extended-sextant TRUS-guided biopsy were also identified. This cohort is referred to as the “standard cohort.” Patients were referred for suspected prostate cancer, which included elevated serum PSA level or abnormal digital rectal examination. Some patients had previously diagnosed low-grade tumors. For patients who had a standard biopsy performed at UAB and initially chose AS followed by MRI-targeted biopsy at a later date, the management choices that these patients made were recorded in their respective groups. Patients who had a previous positive biopsy performed at an outside institution followed by targeted biopsy at UAB were only included in the target cohort, as the charts from the outside institutions were not available for review as a part of this study. Patient demographics, insurance status, and pathologic findings were reviewed. More than 80% of patients in both cohorts had management discussions with one of 2 urologic oncologists.

Our institutional protocol for MRI consists of triplanar T2-weighted imaging, diffusion weighted imaging with calculated apparent diffusion coefficient map, and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI. Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PIRADS) scores were assigned based upon the most recent version of PIRADS available at the time of the MRI study. At our institution, targeted biopsy is most commonly performed in patients with at least 1 lesion scored with a PIRADS 3 or greater. A minority of patients who have low suspicion via imaging parameters but have high clinical suspicion undergo targeted biopsy with lower PIRADS scoring.

All patients in the target cohort underwent MRI to identify areas within the prostate gland suspicious for prostate cancer. Patients in both cohorts then proceeded to standard-of-care, systematic 12-core extended-sextant TRUS-guided biopsy, including 2 cores (lateral and medial) from each sextant region. Patients in the target cohort additionally underwent targeted biopsy of MRI-identified lesions using the UroNav (Philips/InVivo, Gainsville, FL) MRI/US fusion biopsy platform. All biopsies of MRI/US targeted lesions were performed by one of 2 urologic oncologists with at least 2 cores sampled from each MRI-targeted lesion as previously recommended [13]. The overall prostate cancer grade group for each biopsy session was based on the core with the highest grade group in each case. Prostate cancer grade groups were defined as follows: Gleason score ≤ 6: grade group 1, Gleason score 3 + 4 = 7: grade group 2, Gleason score 4 + 3 = 7: grade group 3, Gleason score 8: grade group 4, Gleason score 9 to 10: grade group 5 [14]. All pathology was reviewed by a single fellowship trained genitourinary pathologist.

All continuous variables are expressed as means with standard deviations and compared using Student t-test comparison while categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages and compared with chi-squared test with Fisher exact modification for categorical values with low proportion incidence in the dataset. Multiple variable logistic regression was used to examine relationships between characteristics and AS choice. Type III analysis of effect P values were calculated in order to examine overall categorical differences across race and other covariates in the model. In our multivariable model, we examined multicollinearity of covariates using the variance inflation factor threshold of 5. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4, where statistical significance was considered if P values were less than 0.05.

3. Results

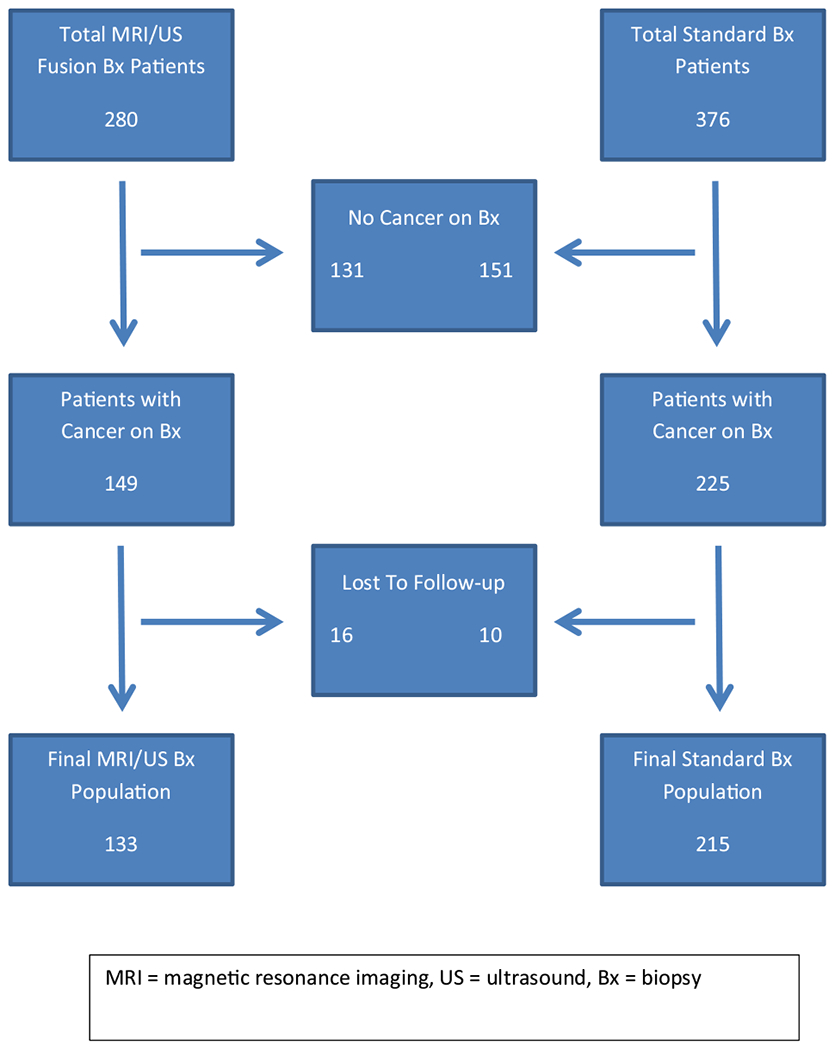

A total of 280 patients were identified that underwent systematic TRUS-guided 12-core sextant extended biopsy plus MRI/US targeted biopsy, of which 149 (53%) had cancer detected. Of this cohort, 16 were lost to follow-up, leaving 133 patients available for evaluation of management decisions in the target cohort. A total of 376 patients were identified who underwent only standard TRUS-guided 12-core extended sextant biopsy, of which 225 (60%) had cancer detected. Of this cohort, 10 were lost to follow-up, leaving 215 patients available for evaluation of management decisions in the standard cohort (Fig). The clinical and pathologic features of the patients excluded from our cohort are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Fig.

Patients who underwent prostate biopsy.

We compared the clinical and pathologic features of all patients with cancer detected on biopsy between the 2 cohorts (Table 1). The standard cohort was composed of a higher proportion of African-Americans patients compared to the target cohort: 118/225 (52.4%) vs. 38/149 (25.5%), respectively (P < 0.0001). Also, the distribution of insurance status was significantly different between the 2 cohorts (P < 0.0001). Patients in the target cohort were significantly more likely to carry military insurance coverage. Patients in the standard cohort were younger compared to the target cohort; mean age 62.7 ± 7.5 vs. 64.5 ± 7.2 years, respectively (P = 0.02). Mean prostate volume was significantly higher in the target cohort compared to the standard cohort; 46.0 ± 20.7 vs. 37.1 ± 16.7 ml, respectively (P = 0.0002). When reviewing the history of prior prostate biopsy, more patients in the standard cohort were biopsy naïve compared to the target cohort; 187/225 (83.1%) vs. 44/149 (29.5%), respectively (P < 0.0001). In addition, the target cohort had more patients with lower grade disease (P = 0.02). Mean (SD) PSA was comparable between the 2 groups (P = 0.11).

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic features in all patients with prostate cancer detected on biopsy at UAB

| Target cohort | Standard cohort | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients with cancer | 149 | 225 | – |

| Race | |||

| African American | 38 (25.5) | 118 (52.4) | <0.0001 |

| Non-African American | 111 (74.5) | 107 (47.6) | |

| Insurance status | |||

| Private insurance | 73 (49.0%) | 106 (47.1%) | <0.0001 |

| Medicare | 60 (40.2%) | 89 (39.6%) | |

| Medicaid | 1 (6.7%) | 17 (7.6%) | |

| Military | 15 (10.1%) | 6 (2.7%) | |

| Uninsured | 0 (0%) | 7 (3.1) | |

| Mean age ± SD (range) [y] | 64.5 ± 7.2 (44–82) | 62.7 ± 7.5 (46–91) | 0.02 |

| Mean PSA ± SD (range) [ng/ml] | 10.1 ± 10.0 (1.32–76.3) | 12.9 ± 20.5 (1.06–188) | 0.11 |

| Mean prostate volume ± SD (range) [cc] | 46.0 ± 20.7 (19.7–127) | 37.1 ± 16.7 (14–110) | 0.0002 |

| Prior biopsy history, n (%) | |||

| No prior | 44 (29.5) | 187 (83.1) | <0.0001 |

| Prior negative | 47 (31.5) | 7 (3.1) | |

| Prior positive | 58 (38.9) | 31 (13.8) | |

| Highest grade group, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 66 (44.3) | 62 (27.6) | 0.02 |

| 2 | 41 (27.5) | 86 (38.2) | |

| 3 | 18 (12.1) | 30 (13.3) | |

| 4 | 12 (8.1) | 24 (10.7) | |

| 5 | 12 (8.1) | 23 (10.2) |

UAB = University of Alabama at Birmingham.

There was a significant difference in the distribution of management choices between the 2 cohorts (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). More patients in the target cohort chose AS compared to patients in the standard cohort; 66/133 (49.6%) vs. 52/215 (24.2%), respectively. In the target cohort, a similar amount of patients chose radiation ± hormonal therapy vs. radical prostatectomy; 33/133 (24.8%) vs. 31/133 (23.3%), respectively. In the standard cohort, nearly double the proportion of patients chose radiation ± hormonal therapy over radical prostatectomy; 101/215 (47.2%) vs. 52/215 (24.4%), respectively. Few patients in the target cohort and the standard cohort underwent hormonal therapy ± chemotherapy; 2/133 (1.5%) vs. 10/215 (4.7%), respectively. Only 1 patient underwent focal therapy, and this patient was in the target cohort.

Table 2.

Management choices in patients with cancer on biopsy performed at UABa

| Target cohort, n (%) | Standard cohort pts, n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active surveillance | 66 (49.6) | 52 (24.2) | <0.0001 |

| Radiation ± hormonal therapy | 33 (24.8) | 101 (47.2) | |

| Radical prostatectomy | 31 (23.3) | 52 (24.4) | |

| Hormonal therapy ± chemotherapy | 2 (1.5) | 10 (4.7) | |

| Focal therapy | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) |

UAB = University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Excludes patients lost to follow-up.

We further analyzed management choices between the 2 cohorts with respect to prostate cancer grade group detected. We found a significant difference between the target cohort and the standard cohort in those who chose AS vs. treatment in patients with grade group 1 and grade group 2 tumors (P = 0.02 and P = 0.005, respectively). Overall, in both cohorts, the majority of patients chose AS for grade group 1 tumors and definitive therapy for tumors > grade group 1. However, for patients with grade group 1 and grade group 2 tumors, more patients in the target cohort chose AS over treatment compared to the standard cohort. (Table 3). The expanded breakdown of management choices are presented in Supplemental Table 2.

Table 3.

Management choices stratified by grade group

| Target cohort | Standard cohort | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade group 1 | |||

| Active surveillance | 54 (88.5) | 45 (73.8) | 0.02 |

| Treatment | 7 (11.5) | 16 (26.2) | |

| Grade group 2 | |||

| Active surveillance | 10 (27.0) | 6 (7.4) | 0.005 |

| Treatment | 27 (73.0) | 75 (92.6) | |

| Grade group 3 | |||

| Active surveillance | 2 (12.5) | 1 (3.7) | 0.26 |

| Treatment | 14 (87.5) | 27 (96.4) | |

| Grade group 4 | |||

| Active surveillance | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Treatment | 10 (100) | 23 (100) | |

| Grade group 5 | |||

| Active surveillance | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Treatment | 9 (100) | 22 (100) |

Upon stratifying management choice by race, we found that among both groups, African Americans chose radiation therapy more frequently (70/137, 51.1%) compared to non-African Americans (64/211, 30.3%) P = 0.0001. In addition, among African Americans, radiation therapy was chosen more frequently in the standard cohort (P = 0.01). Among African Americans, more patients underwent AS in the target cohort (8/22, 36.4%) vs. the standard cohort (22/115, 19.1%), however, this result was not statistically significant (P = 0.07). Among non-African Americans, AS was preferred in the target cohort (58/111, 52.3%) vs. the standard cohort (30/100, 30.0%) P = 0.001 (Supplemental Table 3).

Multivariable logistic regression models were created to evaluate the independent prognostication of MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy technique in predicting selection of AS. In a model of clinical parameters predicting AS, we evaluated age, PSA density (PSAD), prior biopsy history, race, urologist, highest grade group on biopsy, and biopsy approach (Table 4). Among the evaluated parameters, PSAD (P = 0.046), race (P = 0.037), biopsy approach (P = 0.013), and grade group (P ≤ 0.0001) remained independent predictors of choosing AS. Patients of African American race were less likely to choose AS (odds ratio, OR = 0.46 [95% CI: 0.25–0.85]) compared to patients of non-African American race. MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy approach was 3.93 times more likely to predict AS over systematic biopsy.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression model for clinical parameters predicting active surveillance management choice

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 (0.96–1.07) | 0.56 |

| PSAD | 0.62 (0.39–0.99) | 0.046 |

| Prior biopsy history | ||

| No prior vs. prior positive | 0.72 (0.26–2.00) | 0.174 |

| Prior negative vs. prior positive | 0.30 (0.088–1.06) | |

| Race | 0.44 (0.20–0.95) | 0.037 |

| Biopsy approach (MRI/US fusion vs. standard) | 3.93 (1.34–11.53) | 0.013 |

| Highest grade group on biopsy | 0.044 (0.021–0.091) | <0.0001 |

| Urologist | 0.54 (0.22–1.36) | 0.14 |

In a multivariable logistic regression model selecting for patients with grade group 1 and grade group 2 tumors, prior biopsy history (P = 0.04), race (P = 0.013), and biopsy approach were independent predictors of choosing AS. MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy approach was 3.25 times more likely to predict AS over systematic biopsy. In this subset analysis, patients who had a prior positive biopsy were less likely to undergo AS compared to those with a prior negative biopsy (OR = 0.30 [95% CI: 0.11–0.82]) (Table 5). An additional subset analysis with exclusion of patients with a prior positive biopsy from both cohorts demonstrated that biopsy approach remained an independent predictor of selecting AS on multivariable logistic regression modeling (P = 0.0002).

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression model for clinical parameters predicting active surveillance management choice in patients with grade group 1 and grade group 2 tumors

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 (0.95–1.04) | 0.70 |

| PSAD | 0.49 (0.24–1.03) | 0.06 |

| Prior biopsy history | ||

| Prior positive vs. no prior | 0.47 (0.20–1.06) | 0.04 |

| Prior positive vs. prior negative | 0.30 (0.11–0.82) | |

| Race | 0.46 (0.25–0.85) | 0.013 |

| Biopsy approach (MRI/US fusion vs. standard) | 3.25 (1.43–7.43) | 0.0051 |

| Urologist | 0.99 (0.42–2.36) | 0.10 |

4. Discussion

In 2014 we implemented MRI/US fusion-targeted prostate biopsy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. We have previously shown promising results in the implementation of this new technique at out institution. We have shown that compared to the systematic 12-core extended sextant biopsy, targeted biopsy detects an equal amount of cancer while identifying higher grade tumors compared to systematic biopsy cores [2]. Perineural invasion was also found to be detected more often on targeted biopsy [1]. Our studies showed that targeted biopsy allows for better representative sampling and assessment of a patient’s disease with the added benefit of less biopsy core sampling. To our knowledge no previous studies have addressed patient management choice in the setting of MRI/US targeted biopsy. We sought to assess the influence of this new biopsy technique on patient’ s management choices.

Similar to the trend seen in medical centers across the United States, many of our patients are diagnosed with low-grade disease that is amendable to AS. We hypothesized that MRI/US targeted biopsy at our institution could influence patients’ management choices, especially in regards to selecting AS. We found equivalent PSA levels between the target and standard cohorts. More patients in the target cohort (50%) chose AS over the standard cohort (24%), which held true not only for grade group 1 but also grade group 2 tumors. There is now evidence that some very select patients with intermediate risk prostate cancers can safely undergo AS [10,11]. Grade group 3 and higher tumors had no difference in the overall distribution of management choices, which is to be expected as AS would not be recommended in these cases. On univariate analysis, we found a difference in the overall distribution of prostate cancer grade groups between the 2 cohorts. Given that more patients in the target cohort had low-grade tumors, we performed a multivariate analysis to better understand which factors were influencing management choice. The preference for AS in the target cohort remained statistically significant after adjusting for age, PSAD, prior biopsy history, provider, tumor grade, and race (P = 0.013). Men who had an MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy were 3.93 times more likely to undergo AS over systematic biopsy (Table 4). Furthermore, in a multivariable logistic regression model selecting for patients with grade group 1 and grade group 2 tumors, biopsy approach remained an independent predictor of choosing AS. MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy approach was 3.25 times more likely to predict AS over systematic biopsy. In this subset analysis, patients who had a prior positive biopsy were less likely to undergo AS compared to those with a prior negative biopsy (OR = 0.30 [95% CI: 0.11–0.82]) (Table 5).

In addition, we analyzed the data excluding all patients who had a diagnosis of prostate cancer prior to the biopsy performed at our institution (those who presented on AS). This subset analysis was performed since a significant proportion of the patients in the target cohort had a prior positive biopsy compared to patients in the standard cohort (39% vs. 14%, respectively). This finding could potentially bias patients in the target cohort towards selecting AS, as these patients commonly have low-grade prostate cancer and are seeking confirmatory biopsy. Nevertheless, subset analysis with exclusion of patients with a prior positive biopsy from both cohorts demonstrated that biopsy approach remained an independent predictor of selecting AS on multivariable logistic regression modeling (P = 0.0002).

Many factors go into a patient’s decision to pursue/continue AS, including the recommendation of the physician, the patient’s rapport with the physician, and the patient’s understanding of the nature of their disease process [15,16]. Many of these factors were controlled for between our cohorts in that over 80% of patients diagnosed with prostate cancer over the study period were advised by one of 2 physicians irrespective of the biopsy approach. Interestingly, we did not find the physician providing the patient counseling to be an independent predictor of AS on multivariate analysis (P = 0.14) Patient anxiety relating to living with cancer can be a major limiting factor in adherence to AS. MRI/US targeted biopsy has the benefit of sampling suspicious lesions that can be visualized on MRI. This could potentially allow patients a better insight into the nature of their disease given the additional data available via imaging. A better understanding of their disease could lead to decreased anxiety with the concept of AS. In addition, studies have shown that there is a more accurate correlation of MRI-directed biopsy to final, gold-standard radical prostatectomy pathology [6]. Thereby physicians might feel more comfortable that MRI-targeted biopsy results are truly representative of the patent’s tumor and that a higher grade lesion was not missed. This could lead to physicians being more comfortable recommending AS. The increased confidence in correctly assessing the biological behavior of the disease could be additionally reassuring to the patient.

We did see differences in clinical parameters between the 2 groups. Patients in the target cohort were older and had larger prostate volumes. It is intuitive that older patients are more likely to have larger volume prostate glands. It is also possible that the target cohort was enhanced with a population of patients with occult cancers that can be difficult to sample in larger prostate glands including anteriorly located cancers [17,18]. MRI/US targeted biopsy has been shown to be helpful in detecting occult cancers in larger glands [18]. The target cohort also had significantly more patients who had a prior prostate biopsy (74.5% vs. 14.2%), with 31.5% of patients in the target cohort having at least 1 prior negative prostate biopsy session. This finding can be explained by the current requirements for patients to have a MRI/US targeted prostate biopsy covered by many insurance providers. Most insurance companies will not cover the procedure for biopsy naïve patients and some will not cover prostate indication MRI at all. We found that management choice continued to be significant on multivariate analysis when including prior biopsy history. Interestingly, on multivariate analysis, biopsy history was an independent predictor of AS in patients with grade group 1 and 2 tumors (P = 0.04). Patients who had a prior positive biopsy were less likely to undergo AS compared to those with a prior negative biopsy (OR = 0.30 [95% CI: 0.11–0.82]).

Significantly less African American patients underwent MRI/US targeted biopsy compared to the standard biopsy; 15.4% vs. 52.4%, respectively. This is largely explained by the low number of African American men that are seen at our institution for a confirmatory biopsy session, which is the most common indication for a MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy. Another potential factor may be access to health care by means of the referral patterns to our tertiary care center and distances associated with the regional area that our institution serves. In addition, in our series there were significantly more uninsured patients in the standard cohort compared to the target cohort (3% vs. 0%). Patients who are uninsured will not have access to diagnostic MRI to guide the biopsy procedure. In addition, the target cohort had a significantly higher proportion of men carrying military health insurance. At our institution there is a close working relationship with the local Veteran Administration (VA) hospital. Patients who undergo prostate MRI at the VA hospital, are referred to our institution for targeted biopsy when found to have suspicious lesions. This explains the finding that more patients in the target cohort carry military insurance, as systematic biopsies are routinely provided at the VA hospital. Socioeconomic and racial disparities in cancer treatment have been well documented in the United States [19–26]. Overall cancer mortality is higher among lower socioeconomic groups and minorities [20]. Future studies investigating more in-depth socioeconomic status should address whether access to MRI/US targeted biopsy is an important factor in influencing management choices in prostate cancer.

In terms of definitive treatment, we noticed that a similar number of patients in the target and standard cohort chose radical prostatectomy. However, there were more patients in the standard cohort (47.2%) that chose radiation therapy compared to the target cohort (24.8%). Given the previously described racial disparity we found between the 2 groups, we hypothesized that race might be contributing to this observation. After stratifying by race, we found no significant difference in the number of patients that chose radical prostatectomy between the target and standard cohorts. Among African-Americans, more men who underwent systematic biopsy chose primary definitive radiation therapy (55.7% vs. 27.3%). The same was not seen among non-African Americans. Some studies have shown a preference for radiation therapy over radical prostatectomy among African Americans [23–25]. Among African-Americans, lower socioeconomic status has also been shown to predict increased rates of radiation therapy over radical prostatectomy [26]. In addition, on multivariate analysis, race was found to be an independent predictor of AS between the 2 cohorts, with African Americans favoring definitive therapy. This held true for all patients (P = 0.037) as well as when stratifying for grade group 1 and grade group 2 tumors (P = 0.013). Thus the data seems to suggest that race likely played a component in radiation being preferentially chosen over radical prostatectomy in the standard cohort.

At our institution it is standard of care for patients diagnosed with prostate cancer to be referred to consultation with an oncologic urologist as well as a radiation oncologist for discussion of all treatment options. In addition, our radiation oncologists routinely offer AS for those patients meeting the appropriate criteria. Both target and standard group patients were exposed equivalently to the same group of urologists and radiation oncologists. This is reflected in the fact that on multivariate analysis the individual provider was not a significant factor in determining management choice (P = 0.14).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate prostate cancer management choices in patients undergoing MRI/US fusion-guided biopsy. We acknowledge some limitations to the current study. Our target biopsy cohort is inherently different from the standard cohort in that the patient population is older, has larger volume prostates, and are more likely to have undergone a previous positive biopsy. However, this difference in of itself is an important reality to recognize in patients undergoing targeted biopsy. This paper has also not investigated the role of socioeconomic status in our population, which has previously been reported as correlating with radical disparities with respect to prostate cancer in the United States. We assume that the disparities reported in other studies hold true for our patient population. However, future studies are required to address this issue to determine if the technical approach to technique remains an independent predictor of management choices by men diagnosed with prostate cancer.

5. Conclusions

Overall, AS was more frequently chosen in patients in the target cohort compared to the standard cohort for patients with grade group 1 and grade group 2 tumors. This finding held true after adjusting for age, PSAD, prior biopsy history, provider, and race.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.02.003.

References

- [1].Gordetsky JB, Nix JW, Rais-Bahrami S. Perineural invasion in prostate cancer is more frequently detected by multiparametric MRI targeted biopsy compared with standard biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:490–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gordetsky JB, Thomas JV, Nix JW, et al. Higher prostate cancer grade groups are detected in patients undergoing multiparametric MRI-targeted biopsy compared with standard biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:101–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rais-Bahrami S, Siddiqui MM, Turkbey B, et al. Utility of multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging suspicion levels for detecting prostate cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:1721–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Baco E, Rud E, Eri LM, et al. A randomized controlled trial to assess and compare the outcomes of two-core prostate biopsy guided by fused magnetic resonance and transrectal ultrasound images and traditional 12-core systematic biopsy. Eur Urol 2016;69:149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Salami SS, Ben-Levi E, Yaskiv O, et al. In patients with a previous negative prostate biopsy and a suspicious lesion on magnetic resonance imaging, is a 12-core biopsy still necessary in addition to a targeted biopsy? BJU Int 2015;115:562–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Siddiqui MM, Rais-Bahrami S, Turkbey B, et al. Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. J Am Med Assoc 2015;313:390–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kryvenko ON, Carter HB, Trock BJ, et al. Biopsy criteria for determining appropriateness for active surveillance in the modern era. Urology 2014;83:869–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Eifler JB, Alvarez J, Koyama T, et al. More judicious use of expectant management for localized prostate cancer during the last 2 decades. J Urol 2017;197:614–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Godtman RA, Holmberg E, Khatami A, et al. Outcome following active surveillance of men with screen-detected prostate cancer. Results from the Göteborg randomised population-based prostate cancer screening trial. Eur Urol 2013;63:101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Musunuru HB, Yamamoto T, Klotz L, et al. Active surveillance for intermediate risk prostate cancer: survival outcomes in the Sunnybrook experience. J Urol 2016;196:1651–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bul M, van den Bergh RC, Zhu X, et al. Outcomes of initially expectantly managed patients with low or intermediate risk screen-detected localized prostate cancer. BJU Int 2012;110:1672–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lai WS, Gordetsky JB, Thomas JV, et al. Factors predicting prostate cancer upgrading on magnetic resonance imaging-targeted biopsy in an active surveillance population. Cancer 2017. 10.1002/cncr.30548:[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hong CW, Rais-Bahrami S, Walton-Diaz A, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound (MRI-US) fusion-guided prostate biopsies obtained from axial and sagittal approaches. BJU Int 2015;115:772–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gordetsky J, Epstein J. Grading of prostatic adenocarcinoma: current state and prognostic implications. Diagn Pathol 2016;11:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dall’Era MA. Patient and disease factors affecting the choice and adherence to active surveillance. Curr Opin Urol 2015;25:272–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Orom H, Homish DL, Homish GG, et al. Quality of physician-patient relationships is associated with the influence of physician treatment recommendations among patients with prostate cancer who chose active surveillance. Urol Oncol 2014;32:396–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Volkin D, Turkbey B, Hoang AN, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and subsequent MRI/ultrasonography fusion-guided biopsy increase the detection of anteriorly located prostate cancers. BJU Int 2014;114:E43–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Walton Diaz A, Hoang AN, Turkbey B, et al. Can magnetic resonance-ultrasound fusion biopsy improve cancer detection in enlarged prostates? J Urol 2013;190:2020–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Moses KA, Orom H, Brasel A, et al. Racial/ethnic disparity in treatment for Prostate cancer: does cancer severity matter?. Urology 2017;99:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Singh GK, Jemal A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950-2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J Environ Public Health 2017;2017:2819372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kelly SP, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF, et al. Trends in the incidence of fatal prostate cancer in the United States by race. Eur Urol 2017;71:195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Krishna S, Fan Y, Jarosek S, et al. Racial disparities in active surveillance for prostate cancer. J Urol 2017;197:342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chornokur G, Dalton K, Borysova ME, et al. Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate 2011;71:985–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Moses KA, Paciorek AT, Penson DF, et al. Impact of ethnicity on primary treatment choice and mortality in men with prostate cancer: data from CaPSURE. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1069–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Denberg TD, Beaty BL, Kim FJ, et al. Marriage and ethnicity predict treatment in localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2005;103: 1819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mahal BA, Ziehr DR, Aizer AA, et al. Getting back to equal: the influence of insurance status on racial disparities in the treatment of African American men with high-risk prostate cancer. Urol Oncol 2014;32:1285–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.