Abstract

In estrogen receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer therapy, estrogen receptors (ERs) are the major targeting molecules. ER-targeted therapy has provided clinical benefits for approximately 70% of all breast cancer patients through targeting the ERα subtype. In recent years, mechanisms underlying breast cancer occurrence and progression have been extensively studied and largely clarified. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, microRNA regulation, and other ER downstream signaling pathways are found to be the effective therapeutic targets in ER+ BC therapy. A number of the ER+ (ER+) breast cancer biomarkers have been established for diagnosis and prognosis. The ESR1 gene mutations that lead to endocrine therapy resistance in ER+ breast cancer had been identified. Mutations in the ligand-binding domain of ERα which encoded by ESR1 gene occur in most cases. The targeted drugs combined with endocrine therapy have been developed to improve the therapeutic efficacy of ER+ breast cancer, particularly the endocrine therapy resistance ER+ breast cancer. The combination therapy has been demonstrated to be superior to monotherapy in overall clinical evaluation. In this review, we focus on recent progress in studies on ERs and related clinical applications for targeted therapy and provide a perspective view for therapy of ER+ breast cancer.

Keywords: estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, estrogen receptor, mutation, endocrine therapy, biomarkers, resistance mechanisms, clinical trials, targeted therapy, combination therapy

Introduction

The incidence of breast cancer (BC) is increasing worldwide in recent years, posing a serious threat to women's health. About 75% of BC patients are clinically diagnosed with estrogen receptor positive (ER+) tumors. Regulation of ER activity and expression becomes a key topic in both basic and clinical BC research. There are 2 types of estrogen receptor (ER), one is the transmembrane type or G-protein coupled receptor type, known as GPER, the other is the nuclear receptor type. In this review, we focus only on the nuclear receptor type ER. The nuclear receptor type ER is encoded by 2 genes, ESR1 and ESR2, and the corresponding protein products are ERα and ERβ. 1 Increased ERα activity is positively associated with BC progression. 2 ESR1 may mutate during therapy that leads to development of resistance to therapeutic drugs such as antiestrogen and/or ER drugs (endocrine therapy [ET]). ERβ has a broad-spectrum tumorigenesis effect. Apparently, ER-negative (ER−) BC cannot be treated by ET because of a lack of ER expression.

Development of ET resistance is a major problem in the ER+ BC treatment. When the classical ET drugs, such as aromatase inhibitors (AIs), selective ER modulators (SERMs) and selective ER degraders (SERDs) are used for treatment, the ER+ tumor usually develops drug resistance in the late stage. Causes for the drug resistance include, but are not restricted to, ESR1 mutation, BRCA1/2 mutation, 3 and upregulation of specific microRNAs (miRNAs) (eg, miR-221/222). 4 This has resulted in the need for the establishment of predictive and prognostic markers for detecting the drug resistance of BC. The expression level of ERα5–7 and the ESR1 mutations8,9 has been used as predictive or prognostic biomarkers in the ER+ BC. Many other drug resistance biomarkers of the ER+ BC have been identified and will be described in detail in the following sections. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs), drop-digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR), and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are the main methods for detecting the related molecules expression levels or mutations of the drug resistance genes.

A combination of multiple antitumor drugs has been applied for the therapy of the ER+ BC in drug resistance or metastasis settings in clinical trials. For example, treatment with the cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitors (palbociclib、ribociclib and abemaciclib) in combination with fulvestrant (SERD), which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has significantly improved survival of ET-resistant BC patients.10–12

Nowadays, numerous studies have reported new findings of the structure and function of ERs and the upstream and downstream pathways regulating ERs in BC cells. A number of clinical trials have shown the therapeutic efficacy of newly developed drugs. Many statistical data on combination therapies have been published. This review seeks to summarize the latest studies on the mechanism of the ET resistance of the ER+ BC and the therapy with newly developed drugs and clinical data in recent years.

Structure and Function of ERs

ER is a ligand-activated transcription factor (TF). 1 ER has 2 members: ERα and ERβ that are encoded by genes ESR1 and ESR2, respectively. ESR1 is located at chromosome position 6q24-27, and ESR2 at 14q22-24.13–15 The expression profile of ESR1 is very different from that of ESR2 in human tissues and cell types. ESR1 is mainly expressed in the uterus, pituitary gland, liver, hypothalamus, bone, mammary gland, cervix and vagina, while ESR2 is predominantly expressed in ovary, lung, and prostate. 16

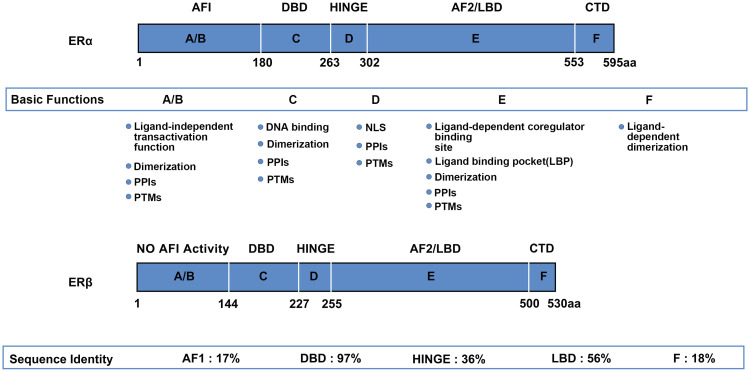

The tertiary structures of the ESR1 product ERα and the ESR2 product ERβ are highly similar with minor differences in some domains. Both receptors possess 5 structural domains: an N-terminal domain (NTD; A/B-domain) containing the transcription activation function 1 (AF-1) region that regulates ligand-independent transcriptional activity; 17 a DNA-binding domain (DBD; C-domain) that has 2 “zinc-finger” motifs capable of interacting with the estrogen response element (ERE); a hinge region (D-domain) that connects the C-domain and the E-domain and serves as an interface for the receptor posttranslational modifications (PTMs); a ligand-binding domain (LBD; E-domain) containing the ligand-binding pocket 18 and the transcription activation function 2 (AF-2) region that plays an essential role in ligand-dependent transcriptional regulation; 17 and a C-terminal domain (CTD; F-domain) that regulates ligand-dependent dimerization. 19 Although ERα and ERβ contain similar domains, their A/B, D and F domains are quite different from each other (Figure 1).1,20

Figure 1.

Domain structure of ERα and ERβ. Basic modular domain structure and functions of ERα and ERβ is very similar. The domain similarity of the 2 receptors is: the N-terminal domain (NTD; A-/B-domain) 17%; the DBD (C-domain) 97%; the hinge region (D-domain) 36%; the LBD (E-domain) 56%; and the CTD (F-domain) 18%, respectively. All the domains of the 2 receptors undergo PTMs. Some of domains are involved in PPIs, such as interaction with coregulator proteins. Both ERα and ERβ contain a NLS in the hinge domain. In addition, the NTD of ERβ has no AF1 activity, suggesting that ERβ may not have the ligand-independent transcriptional activity. Abbreviations: DBD, DNA-binding domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; CTD, C-terminal domain; PTM, posttranslational modification; PPI, protein–protein interaction; NLS, nuclear localization signal; NTD, N-terminal domain; ER, estrogen receptor.

Based on subcellular localization of ERs including cell membrane, cytoplasm and the nucleus, the physiological effects of ERs can be classified into 2 categories: nongenomic effects on cell membrane and genomic effects on the cytoplasm and nucleus. Nongenomic effects are complicated and make affects not only in ER+ BC, so they will not be dealt with in detail in this review. The genomic effects of ERs on the target gene transcription are through following 3 aspects: (i) direct binding to corresponding DNA ERE; (ii) interaction with other TFs to activate gene transcription; and (iii) a ligand-independent transactivation via phosphorylation of AF-1, which is a highly conserved DBD that binds to ERE.

Estrogen-ER binding triggers conformational changes in the LBD, which is an α-helical bundle, with the C-terminal helix, H12, forms ER dissociation from the molecular chaperone heat shock protein-90 and assembles into homodimers (ERα/ERα or ERβ/ERβ) and heterodimers (ERα/ERβ), allows the complex to bind to DNA EREs. Then, recruitment event begins that specific coactivators or corepressors gather and associate with ERs, activating or inhibiting gene transcription. 21 Estrogen binding increases the number of binding peaks in the genome. The mouse model of DBD mutation of ERα shows that direct DNA binding is needed in order to induce hormonal response and biological activity. Direct DNA binding also needs to be supplemented by other signaling mechanisms, such as pioneering factor FoxA1 and GATA2, which allows the recruitment of chromatin remodeling proteins, opens chromatin so that ER can enter its DNA regulatory sites following ER transcriptional complex assembly, polymerase II recruitment, and gene transcriptional initiation.22,23 A second method, ERs also regulate gene expressions through indirect or tethered mechanism with protein–protein interactions of other TFs such as AP-1, SP-1, NF-kB 24 that have been bound to DNA, and then associate the receptor with other genes that do not contain ERE (ERE-independent way). Finally, in the absence of ligands, ERs can regulate activity and drive hormonal responses through ligand-independent activation of growth factors or other intracellular signaling pathways (thought to be involved in the phosphorylation of certain serine residues on the receptor, especially at AF-1 domain). 25 Overall, these may explain the complementarity of different cellular signaling pathways, indicating that ER has a great ability to change the phenotypes of cells.

Interestingly, in BC, the reference to ER generally refers to ERα rather than ERβ, which is probably related to the difference in expression and function of the 2 subtypes in BC cells. Statistics show that about two-thirds of BCs are positive for ERα at the time of diagnosis. 26 In BC cells, E2 accelerates disease progression by promoting many processes such as sustaining proliferative signaling that defined by the hallmarks of cancer, 2 however, in comparison to ERα, ERβ binds E2 with lower affinity and has lessened binding to nonconsensus EREs, which represent the majority of estrogen-responsive elements (eg, C-fos, c-jun, pS2, cathepsin D, and choline acetyltransferase cis-regulatory sequences). 27 Early studies using the ER (ERα and ERβ) knockout mice also indicate that ERα plays the significant role in estrogen-mediated metabolic regulation, whereas ERβ−/− mice show only a modest metabolic phenotype. 28 On the contrary, Rahul et al give opinions that ERβ possesses broad-spectrum tumor suppressor activity including BC in the year 2020, which slow down the progression of BC by regulating the genomic and nongenomic effects through a series of complex mechanisms that have not yet been fully explored, and serve as an independent prognostic marker and therapeutic target. 19

ER and BC

Not long ago, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) released the latest global cancer data that the total number of new cancers worldwide is expected to be 19.29 million in 2020. Among them, the number of new cases of BC reached 2.26 million, accounting for about 11.7% of new cancer cases, demonstrating the first time that BC has surpassed lung cancer to become “the largest cancer in the world.” Causes that result in BC include age, early menarche, late menopause radiation exposure, etc. 29 BC can be divided into 4 molecular subtypes on account of gene expression profiles: (i) luminal A, which is characterized by low tumor grade, ER-positivity, strong positive expression of progesterone receptor (PR) (PR≥20%), human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2)-negativity, low expression of Ki67 (< 14%) and have a proliferation of slow; (ii) luminal B, which is ER-positive, PR-positive (low expression,<20%) or HER-2 positive or Ki67 high expression (≥14%), is considered more aggressive; (iii) basal-like tumors/triple-negative (ER−, PR−, HER2−) and (iiii) HER2-enriched (ER−, PR−, HER2+). 30 Notably, ER+ BC accounts for about 70% of all BCs among the 4 categories. Estrogen-ER binding translocates to the cancer cell nucleus and initiates a signaling cascade, resulting in the proliferation and survival of BC cells. This mechanism reveals the important role of ET in the treatment of BC.

ERα and ERβ Crosstalk in Breast Cancer

ERβ expression was significantly correlated with the expression of ERα from the tissue microarray analysis of BC. 31 Given that the expression of ERα and ERβ exists in the majority of BCs, one key question is to understand their crosstalk effects. First of all, ERα itself can directly bind to its homologous DNA binding element EREs. However, the transactivation potential of the ERβ AF1 domain decreased and the cooperative interaction with its AF2 domain reduced, 32 so ERβ has a lower binding to EREs which represent the majority of estrogen-responsive elements. In addition, both ERα and ERβ can also indirectly interact with other DNA-binding TFs such as AP-1.33,34 In the presence of estradiol (E2), ERα was found to upregulate the transcription of ERE-AP-1 composite response elements while ERβ had the opposite effect. 35 Second, the study of Hall and McDonnell showed that ERβ antagonized the effect of ERα on E2-responsive E2-AP-1 complex promoters in transient transfection experiments. It is therefore suggested that selective activation of ERβ can inhibit cell proliferation induced by ERα. 36 Kim et al 37 using the estradiol response promoter containing 3 tandem GC-rich SP1 binding elements finding that both ERα and ERβ proteins interact with SP1 through their C-termini. Indeed, the binding event of ERβ with SP1 represses ERα transcription by recruiting a corepressor complex containing nuclear receptor co-repressor to the ESR1 gene promoter. 38 Furthermore, the interaction between the 2 isoforms with the cell division protein cyclin D1 (CCND1) promoter or EGFR signaling also revealed the opposite interesting effect which ERβ showed an inhibitory impact.39–41 These suggest that ERβ is a negative regulator of the proliferative and invasive effects. Last but not least, steroid receptor co-activator 3 (SRC-3)/AIB-1 which is an oncogenic co-activator in ER+ BC 42 had a positive association with ERα in their expressions but inversed with ERβ. Observation found induced SRC-3 recruitment and enhanced SRC-3/ERα but not SRC-3/ERβ interaction in the location of ERE under certain endocrine drug treatments. 43 The selective interaction of SRC-3 with ERα but not ERβ may explain some of the different cancer outcomes in the presence of drugs between the 2 ER isoforms.

ER and Endocrine Therapy Resistance

Despite the fact that most patients have the early-stage disease at the time of initial diagnosis, more than 25% of patients experience relapse and develop into metastatic BC (MBC). As stated previously, more than 70% of BCs are hormone receptor (HR, contains ER and PR) + and HER2−. Most of these tumors remain ER-positive, but the expression of ER in metastatic sites is lower than that in primary tumors.44–46 Blocking ER signal transduction is the principal treatment for ER+/HER2− BC. At present, effective clinical strategy to treat and arrest palindromia of ER+ BC is ET. ET cures about half of the patients in the nonmetastatic stage, and about 30% of metastatic patients have clinical benefits. Therefore, ET targeting ER activities has greatly reduced the mortality of BC. However, despite effective hormonal and targeted therapy, half of these patients will relapse or progress to incurable metastatic diseases. 47 The occurrence of endocrine resistance in patients with advanced BC is inevitable. ESR1 mutations, ERα PTM by kinase, and ER androgen receptor (AR) crosstalk are involved in this process.

According to genomic alterations, endocrine-resistant breast tumors are divided into 4 groups: (i) tumors with ESR1 gene changes (about 18%); (ii) tumors with impaired mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (about 13%); (iii) tumors with mutations in TFs (about 9%); and (iv) tumors with unknown endocrine resistance (about 60%). Several mechanisms of de novo and acquired ET resistance mainly focus on the imbalance of ER pathway itself, including loss of ER expression, crosstalk between ER and other nuclear receptors, genomic alterations of tumor suppressors or drivers, gene fusions of ESR1, and missense mutations of ESR1.48–50

ESR1 Mutations

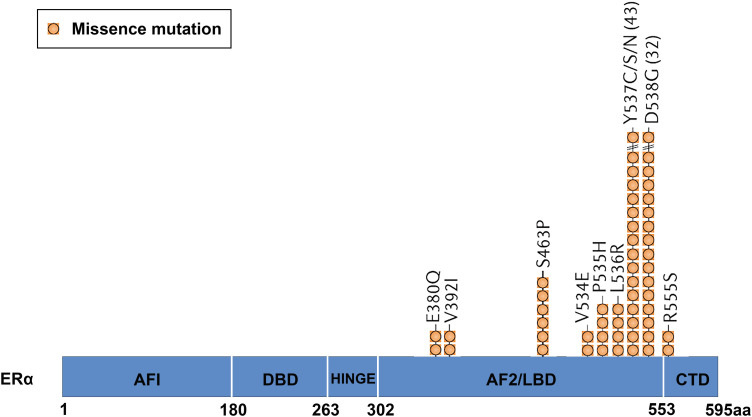

Since it was first described in the cell model in 1996 51 to the present clinical data indicate that ESR1 mutation is one of the most common mechanisms of endocrine resistance.47,52 ESR1 mutations tend to cluster in 2 hot spots of the gene which encodes the ER LBD (about 80% of the encountered mutations), one in exon 5 (E380Q mutation) and the other in exon 8 of helix 12 at codons 536, 537, and 538 (Figure 2).52,53

Figure 2.

The most common mutations occur in the LBD of ERα. Approximately 80% of mutations are D538G, Y537S, Y537N, Y537C, or E380Q, located in the LBD of ERα. Abbreviations: LBD, ligand-binding domain; ER, estrogen receptor.

In addition, there are other mutations, such as K303R (located in the ER hinge region), 54 S463P or L536R/H/P/Q mutations, with a prevalence of less than 3%.55,56 The most common mutations (Y537, D538)8,9,55 have been identified ligand-independent that leads to constitutive activation of ER, thus activating transcriptional function and promoting hormone-independent tumor cell growth.53,57 Both D538G and Y537S (less expressed in Y537N and Y537C) mutations are located in the H11-H12 loop of ERα LBD and have unique transcription actions. By changing the hydrogen bonds at different positions, the conformation of the loop is modified to be more similar to that of wild-type (WT) ER-E2, resulting in the recruitment of co-activators such as SRC-1, SRC-3 in the absence of hormones and further stabilizing its conformation through different biophysical mechanisms. 8 In vitro experiments showed that D538G mutation enhanced the migration ability of BC cells, which may be linked to the frequency of these mutations in the metastatic environment. 57 The activation degree of Y537S mutant is much higher than that of D538G, same with the drug resistance and phenotype invasion, which may explain the reason that Y537S constitutive transcriptional activity is higher than that of D538G. Other mutations lead to estrogen hypersensitivity (K303R, E380Q) or neutral, retaining hormone-dependent activation function (S432L, V534E).54–56 In addition, many of these mutations are rare and have not yet been functionally annotated.

The LBD ESR1 mutation is a gain-of-function activation and occurs in the heterozygous state, which suggests that the functional states of the WT alleles are overridden by those of coexisting mutations. 58 This is in line with clinical sample data showing that up to 20% of endocrine-resistant BCs contain ESR1 mutations, which appear to be rare in primary tumors.52,59 It implies that these mutations are either produced by clonal selection for very low abundance resistant clones, or are acquired later in the disease process under selection pressure from ET. BC cells harboring LBD ESR1 mutations showed partial resistance to tamoxifen (TAM) and fulvestrant in vitro because higher doses of these endocrine drugs were needed to induce their antiproliferative effects in cells carrying such mutations. 53 Data also suggest that LBD ESR1 mutations lead to complete resistance to AIs. 52 Furthermore, apart from the most widespread mutations mentioned above, gene fusions are another well-known activating alteration that has been explored by RNA sequencing, such as ESR1-CCDC170, ESR1-YAP1, ESR1-POLH, ESR1-PCDH11X, and ESR1-AKAP12.60,61 Notably, none of them had the LBD as a common feature. The absence of the LBD greatly reduces the efficacy of the targeted endocrine drugs, and the subsequent increase in frequency of ESR1 fusions in breast ER+ metastatic disease coexists with known missense alterations in ESR1, resulting in polyclonal resistance. 62

Kinase Signaling Pathways of the ERα Posttranslational Modifications

The PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway is the most common altered pathway not only in BC but possibly also in all human cancers. This key signaling pathway regulates cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, survival and other vital cell functions. 63 Crosstalks between proteins involved in the PI3K pathway and the ER activation signaling are related to the development of ER+ BC resistance to ET.64–66 In addition, AKT improves the efficiency of ER S305 phosphorylation in the presence of ESR1 K303R mutations is also closely related to TAM and AIs resistance.50,67,68

Interactions between ER and GFR (such as insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor [IGF-1R], HER2, and fibroblast growth factor receptor) activate the downstream PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways, 69 and accelerate the development of resistance to ET. 70 About 12% of ER-positive tumors possess HER2 gene amplification/overexpression which promotes cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis by activating MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways.71,72 IGF-1R is in charge of the insulin growth factor signaling pathway. The interaction between ER and IGF-1R will alter the antiproliferative effect of TAM by affecting the transcriptional activity of ER.

Overexpression of either p21 protein-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) or 2 (PAK2) is associated with ET resistance and worse clinical outcome. PAK1 induces the S305 ER site phosphorylation which enhances interaction with IGF-1, promoting cell growth. 50 The S305 phosphorylation by PAK1 protects the TAM-bound ER active conformation, similar to the AKT signaling. 73 Xiao T et al discovered an estrogen-induced negative feedback loop that normally constrains the growth of ER+ tumors. In the presence of E2, ER activates C-terminal SRC kinase expression, who represses SRC family kinases (SFKs) 74 and PAK2 activity. Inhibition of SFK and PAK2 represses oncogenic signaling pathways and estrogen-independent growth.

In general, ERα PTMs by kinases is actually one of the important reasons for drug resistance of ET in BC cases.

ER-AR Crosstalk

Almost 90% of ER+ BCs with endocrine resistance are AR-positive (AR+). AR interacts directly with ERα-LBD, promoting the ERα transcriptional activity and vice versa, increasing cell proliferation. 75 A recent ChIP-seq study found that E2-induced AR and ERα-binding sites share 75% overlap. 76 Genomic DNA binding of ERα was only inhibited at those overlapping sites when BC MCF-7 cells were treated with AR antagonists. 76 Some studies also found that interaction between ERα and AR occurred through a long-range enhancer and promoter chromatin interaction.77,78 These findings imply that AR may preferentially regulate the expression of ERα-targeted genes based on the ERα-ERE sequences and that may induce metastasis 79 or decrease ER transcriptional activity.75,80 Additionally, AR overexpression contributes to the conversion of androgens to E2 by CYP19 aromatase 81 which reduces the estrogen deprivation effect of endocrine drug AIs. However, AR-targeted therapy such as fluoxymesterone and testosterone propionate, have been used for the treatment of BC regardless of tumor AR expression levels since the 1940s.82,83 Kono et al retrospectively identified 103 patients with metastatic, ER-positive BC treated with fluoxymesterone and showed a clinical benefit rate of 43%. 84 Moreover, Davies et al found that tumors escape epithelial lineage confinement and transition to a high-plasticity state as an adaptive response to potent AR antagonism in prostate cancer, leading to AR-targeted therapy resistance phenotypes. 85 It is reasonable to speculate that a similar phenomenon may occur in ER+ BC.

Other ER-Mediated Endocrine Therapy Resistance Pathways

BC gene 1 and 2 (BRCA1/2) are tumor suppressor genes that play an important role in cell proliferation and DNA damage repair. 3 Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 lead to loss of tumor inhibition in BC. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations were found in about 5% of BC cases.86,87 Patients with a family history of BC, younger ages, or triple-negative BC have a high risk of the mutations. The BRCA1 mutation drives patients to develop the triple-negative BC to a great extent, while the BRCA2 mutation often induces expression of ERs.88,89

Shank-interactions protein-like 1 (SIPL1) or shank-associated RH domain interactions protein (SHARPIN) is a novel oncogenic protein with extensive carcinogenic activity and associated with poor overall survival (OS) in BC patients.90–92 Role of SIPL1/SHARPIN in BC oncogenesis, especially ER+ BC, has not been thoroughly studied until recent years. It has been reported that overexpression of SIPL1/SHARPIN in BC cells reduces p53 protein levels and p53 target genes MDM2, 93 P21, P53INP1, and BTG2, and increases activity of MAPK and AMPK pathways,94,95 leading to resistance to TAM through AKT activation and NF-kB signaling pathways.96,97

Various oncogenic miRNAs regulated by estrogen/ERα interaction signaling have been found to cause endocrine drug resistance during treatments. It is interesting to note that different miRNAs expression in BC cells is correlated with diverse effects of resistance to endocrine drugs. For example, miR-21 and miR-221/222 are involved in both fulvestrant and TAM resistance, while miR-125b, miR-205, and miR-30a are all significantly upregulated in AI-resistant cell lines.4,98 In addition, BC cells in 1 area which are sensitive to ET may eventually gain ET resistance by capturing miRNA-exosomes secreted from nearby ET-resistant cells. 99

In general, ET resistance is a complicated, not yet fully understood mechanism which brings huge challenges to clinical treatment.

Biomarkers in the ER+ Breast Cancer

ER and PR

ER (ERα) and PR have been used clinically for BC typing and ET selection for decades. It was speculated that the level of ER in BC was related to the benefit of antiestrogen therapy since the 1970s. 5 To this day, ER remains to be the preferred reference marker for all newly diagnosed BC cases and for patients with metastatic/recurrent settings.6,7 PR is often measured along with ER, due to the initial observation that PR is induced by estrogen 100 and competitively binds and alters the chromatin binding sites of ER, 101 changing the transcriptional target genes associated with proliferation into that with cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and differentiation.102,103 Clinical studies also found that patients with ER+, PR+ BC are more likely to respond to ET than patients with ER+, PR−. 104 However, it is not clear that PR has an independent predictive value for adjuvant ET, so the detection of PR exists only as a supplementary reference for ER.105,106

ESR1 Mutation as a Predictive and Prognostic Biomarker

Studies have suggested that ESR1 mutations may be a poor prognostic indicator for ER+ MBC. This is because ESR1 mutations accumulate during endocrine treatment and may produce a more aggressive phenotype through transcriptional changes. Most ESR1 mutations are deemed to occur in the LBD, leading to persistent, ligand-independent activation of ER. 107 Patients with ESR1 mutations had shorter progression-free survival (PFS) than patients who did not (P = .0007). 108 Takeshita et al 109 found that about 72.7% of MBC patients with ESR1 mutations developed polyclonal mutations during treatment, suggesting differences in response to drugs for the individual ESR1 mutations and furthermore, the unique clinical significance for each mutation. ESR1 mutations may occur at low frequency in primary tumors, but be enriched in metastatic ones. Data from a Fergi clinical trial showed ESR1 mutations in 9.7% (3/31) of metastatic samples not treated with AIs, comparing to 63% (12/19) of metastatic samples that treated. 110

In the early stage, traditional tissue biopsies obtain patient samples through repeated invasive surgery, which has a high detection rate and accuracy. However, this may cause serious harm to patients, and take a long time (a month or more) to get the test results. Nowadays, with advancement of DNA sequencing technology, liquid biopsy has become the first clinical choice due to advantages of noninvasion procedures and short test time. ddPCR and NGS are the 2 most commonly used methods for liquid biopsies. DdPCR has been the first choice for detecting ESR1 mutations due to its high sensitivity and accuracy. 111 NGS can gain larger data, such as gene panels, without prior knowledge of mutations. 112 Both approaches are based on the detection of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and cellular free DNA (cfDNA) in patient plasma to identify mutated ESR1 DNA alleles.

HER2 and PI3CA

Overexpression or amplification of HER2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic alpha polypeptide gene (PIK3CA) genes detected by genomic assessment and tumor tissue or blood ctDNA analysis are found to be associated with a shorter median PFS. 113 HER2 gene amplification or overexpression accounts for 15% to 20% of invasive cases. HER2 detection is now indispensable for all new cases of invasive BC and, if feasible, for recurrent / metastatic lesions. Although HER2 was originally proposed as a prognostic biomarker for BC, its current use is primarily to predict neoadjuvant, adjuvant therapy, and anti-HER2 treatment responses in advanced disease. In addition, since anti-HER2 therapy exerts its anticancer activity at least in part by inhibiting activation of the PI3K signaling pathway through HER2 overexpression, specific mutations in the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K (ie PIK3CA gene) can lead to resistance to the anti-HER2 therapy with trastuzumab or lapatinib.114,115 Thus, PIK3CA is, to some extent, a secondary marker for predicting the efficacy of the anti-HER2 therapy.

MicroRNAs

miRNAs are small noncoding RNA molecules composed of about 20–25 nucleotides, which are involved in the regulation of gene expression at the posttranscriptional level and in key processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis, migration, and apoptosis. 116 In serum/plasma, miRNAs are highly stable. 117 The miRNAs expression profile has been used as a reference for molecular classification of BC potential biomarkers and guidance for personalized treatment for nearly a decade. Moreover, the roles of miRNAs in the development of BC are diversified. First, miRNAs are expressed differentially in subtypes of BC. Secondly, disease progression in BC patients is promoted by down-regulation of some tumor suppressor miRNAs (such as miR-206) 118 and up-regulation of oncogenic miRNAs (such as miR-10b and miR-21).118,119 Finally, miRNAs intervene in standard first-line ET by regulation of ERα expression/activity and other oncogenic signaling pathways.

In addition to peripheral blood, the exosome is another site for detecting miRNAs clinically. Exosomes are 50–100 nm-sized vesicles derived from endosomes, secreted from a variety of cell types including cancer cells. The miRNAs are encapsulated in exosomes. Many clinical research data support the exosomal-derived miRNAs as an additional diagnostic tool for the prediction of BC. 120 The miRNA biomarkers of ER+ BC are summarized in Table 1 and the clinical information of those miRNAs is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

miRNAs Overexpressed in ER+ Breast Cancer Used for Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers.

| miRNA overexpression | Prognostic | Prediction of | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worse | Better | Response | Resistance | ||

| let-7f | - | - | Letrozole | - | 121 |

| let-7c | - | Outcome, RFS, OS | - | - | 122 |

| let-7b | - | Outcome, RFS, OS | - | - | 123 |

| miR-10a, miR-375 | - | DFS (TAM treated patients) | TAM | - | 124,125 |

| miR-26a, | - | - | TAM | - | 126 |

| miR-342 | - | - | TAM | - | 127,128 |

| miR-10b | Metastasis promoter | - | - | - | 129,130 |

| miR-221 | OS | - | - | H | 131 |

| miR-21 | OS | - | - | - | 132 |

| miR-29b | - | Metastasis suppressor | - | - | 133 |

| miR-193b | - | Metastasis suppressor | - | - | 134 |

| miR-30a | - | Outcome, RFS, DFS | - | - | 135 |

| miR-30c | - | - | DOX, PTX | - | 136 |

Abbreviations: RFS, relapse-free survival; OS, overall survival; TAM, tamoxifen; DFS, disease-free survival; DOX, doxorubicin; PTX, paclitaxel; H, trastuzumab; ER, estrogen receptor; miRNA, microRNA.

Table 2.

miRNAs Overexpressed in ER+ Breast Cancer Used in Clinic or Clinc Trials.

| miRNA overexpression | Known mechanism | Sample sources | Number of samples | Methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| let-7f | Tumor suppressor miRNA in breast cancer (directly targeted the aromatase gene) | Clinical (obtained from the Celecoxib AntiAromatase Neoadjuvant Trial (CAAN Trial)) | 90 patients | qRT-PCR, Western blotting, Immunohi-stochemistry, Luciferase reporter assay | 121 |

| let-7c | Tumor suppressor miRNA in breast cancer (directly targeted the HER2 gene) | Cell line (MCF-7) from TCGA | - | NanoString, qRT-PCR, Patient sample analysis, Western Blot | 122 |

| let-7b | Tumor suppressor miRNA in breast cancer (directly targeted the BSG gene) | Clinical (First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, China) | 102 samples between 2001 and 2002 | TMA construction, In situ hybridization, Immunohi-stochemical staining | 123 |

| miR-10a, miR-375 | MiR-10a is an Oncogenic miRNA in breast cancer (directly targeted the HOXA1 gene); MiR-375 is a tumor suppressor miRNA in breast cancer (directly targeted the MTDH gene) | Clinical (Robert Bosch Hospital (RBK), Stuttgart, Germany) | 2689 patients between 1986 and 2005 | MicroRNA microarray, qRT-PCR | 124,125 |

| miR-26a, | Suppresses ESR1 expression (directly targeted the ESR1 gene) | Clinical | 235 patients between 1981 and 1996 | qRT-PCR | 126 |

| miR-342 | Tumor suppressor miRNA in breast cancer (regulated genes in multiple tamoxifen actions including both apoptosis and cytostasis.) | Clinical (the Department of Pathology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA) | 791 patients | In situ Apoptosis Assay (TUNEL) | 127,128 |

| miR-10b | Oncogenic miRNA in breast cancer (inhibits synthesis of the HOXD10 protein, permitting the expression of the pro-metastatic gene product) | Collected at the University of Ferrara (Italy), Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milano (Italy), and Thomas Jefferson University (Philadelphia, PA). | 76 samples | miRNA microarray, Northern blotting | 129,130 |

| miR-221 | Suppresses ESR1 expression (directly targeted the ESR1 gene) | Clinical (Department of Breast Surgery, Sun-Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, China) | 125 samples | qRT-PCR | 131 |

| miR-21 | Oncogenic miRNA in breast cancer (associated with poor trastuzumab response.) | Clinical (Department of Breast Surgery, Sun-Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, China) | 32 patients | In Situ Hybridizati-on, Immunohi-stochemistry, MicroRNA microarray, qRT-PCR, Northern blotting | 132 |

| miR-29b | Tumor suppressor miRNA in breast cancer (inhibits metastasis) | Cell lines (MDA-MB-231, T47D) from ATCC | - | qRT-PCR, Immunostaining and histology | 133 |

| miR-193b | Suppresses ESR1 expression (directly targeted the ESR1 gene) | Clinical (Department of Breast Surgery at Shanghai Cancer Hospital, China) | 435 samples | qRT-PCR, MicroRNA microarray, Western blotting, Immunohi-stochemical staining | 134 |

| miR-30a | Tumor suppressor miRNA in breast cancer (decrease the vimentin- mediated migration and invasiveness) | Clinical (Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, China) | 221 patients | MicroRNA microarray, Western blotting, qRT-PCR, Dual luciferase reporter assay | 135 |

| miR-3 30c | Predictor for clinical benefit of tamoxifen therapy | Clinical | 246 patients between 1981 and 1995 | qRT-PCR, Pathways and global testing | 136 |

Abbreviations: TMA, tissue microarray; ER, estrogen receptor; miRNA, microRNA.

Targeted Therapy for ER+ Breast Cancer

Targeting Aromatase by AIs

Aromatase is an enzyme of the cytochrome P450 family. This enzyme catalyzes the conversion of the adrenal substrate androstenedione to estrogen in peripheral tissues such as the breast and liver. The basic principle of using AIs (anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane) in BC patients is to block estrogen production by inhibiting aromatase in the tumor and surrounding tissues. 137 AIs were once the first-line treatment of choice for postmenopausal women with HR+, ER2− metastatic BC (MBC). However, it is common in development of therapeutic relative resistance through acquisition of ligand-independent ESR1 mutations during AI therapy for metastatic ER+ BC. The rate of ESR1 mutations was significantly higher in ER+ MBC patients who progressed to AI resistance than in those who did not (25.8% vs 0%; P = .015). 138 Interestingly, a very low rate of ESR1 mutations was in patients with MBC treated with AIs in adjuvant therapy, but not in metastatic therapy. 139 This conclusion was also confirmed in a French trial, PADA-1, 140 in which only 3.2% (26 of 811) of patients diagnosed with stage IV HR + BC had ESR1 mutations detected in any pretreatment ctDNA. In these patients, the only variable significantly associated with ESR1 mutation detection was exposure to AIs. However, the overall frequency of ESR1 mutations detected in patients exposed to AIs was only 6.4%, which remains low. 141 A plausible explanation for this high prevalence of ESR1 mutations in metastatic settings after exposure to AI therapy and low prevalence of ESR1 mutations in adjuvant settings is that hormonal deprivation by AIs may lead to selection of existing ESR1 mutant subclones. 142 Emerging research found that AI resistance may also be mediated by miRNAs in ER+ BC. In both the letrozole and the anastrozole resistant MCF-7 cell lines, miR-125b, miR-205, and miR-30a were significantly upregulated, while miR-424 downregulated. These miRNA signals are related to regulation of various signaling pathways, including MAPK, focal adhesion, insulin, HER, and mTOR signaling pathways that converge to AKT regulation. 99

Targeting ER by SERMs

SERMs (selective ER modulators) competitively binds ER to form inactive complexes by preventing coactivator interactions.143,144 TAM is the first generation SERM, which has a selective tissue-specific antagonism against ERα in mammary tissue. However, it shows agonism in the endometrium and exhibits agonistic pro-estrogenic properties on the uterine tissue. 145 This results in a seemingly paradoxical increase in the incidence of endometrial cancer (EC) during TAM treatment. 146 Raloxifene, a second-generation SERM, partially compensates this shortcoming and is associated with a lower EC risk. Bazedoxifen is a third-generation SERM with SERD activity that triggers proteasomal degradation of ER by altering conformation of ER. 147 Bazedoxifen effectively inhibited BC cell growth regardless of whether the cells were sensitive or resistant to previous TAM treatment.

SERMs resistance is a major challenge in current BC treatment. There are considerable controversy and uncertainty regarding the mechanisms that lead to SERMs resistance. Currently, TAM is still the most common treatment option among multiple treatment regimens in primary ERα-positive BCs. 148 TAM extends the OS of approximately 85% of ERα-positive BC patients to more than 5 years after diagnosis. 149 However, when TAM treatment continues for 5–10 years, almost 1 in 3 women with primary disease receiving adjuvant TAM will develop resistance to the treatment within a variable time frame. 150 TAM resistance may be caused by genetic alterations, such as miRNAs 151 and ESR1 amplification. 152 Although up-regulation of BECN1 promotes autophagy and suppresses the tumorigenic properties of ER+ BC MCF-7 cells, 153 data from ER+ BC patients treated with TAM and the TAM resistance MCF7 cell line have shown that high BECN1 expression is associated with TAM resistance, high expression of HER2 and reduced patient survival, 154 suggestings that BECN1 is involved in TAM resistance. The miRNAs MiR-221/222, which inhibits the expression of BECN1, thus may enhance TAM sensitivity of ER+ BC. In addition, miR-21, miR-378, miR-27b, miR-342 and other miRNAs are also involved in TAM resistance of ER+ BC cells in vitro. ESR1 mutations reduce the inhibitory effect of SERMs due to structural changes in the H11-12 ring as well as changes in the H12 antagonist status. 142 It seems that TAM resistance is a partial resistance, 155 increasing the therapeutic dose may be sufficient to overcome TAM resistance. Metastatic TAM-resistant BC, which still expresses functional and highly active ERα in most cases, is difficult to treat and currently has no standard treatment regimens. 59 By far the best treatment options for treating metastatic TAM-resistant BC are still ET and high-dose TAM for preventing the proliferation of the cancer cells.

Targeting ER by SERDs

SERDs antagonize ERα and trigger receptor degradation via 26S proteasome, resulting in decreased ERα protein levels. This property makes SERDs as a unique type of inhibitors that block ERα signaling by reducing the protein level of ERα. Fulvestrant is the first and only SERD approved as a therapeutic drug for treatment of advanced BC. 156 Unlike TAM which exerts an agonistic effect, fulvestrant has no agonistic action. 157 Binding affinity of fulvestrant to ER is about 100 times higher than that of TAM. 158 Preclinical and clinical data have shown that fulvestrant is effective even in TAM resistant models.159,160 However, intramuscular administration of fulvestrant has poor bioavailability. Thus, development of oral SERDs is particularly important for ER+ BC treatment.

The initial study of fulvestrant approved by the US FDA in 2002 was based on a dose of 250 mg per month intramuscular injection. 161 In some studies, a load dose of 500 mg was also given. Median-free survival in the CONFIRM trial was 5.5 and 6.5 months in the 250 and 500 mg dose groups, respectively (hazard ratio 0.80 [95% confidence interval 0.68-0.94]); P = .006]. Median OS was 22.3 months in the 250 mg dose group and 26.4 months in the 500 mg dose group (hazard ratio 0.81 [95%CI 0.69-0.96]; nominal P = .02).162,163 Thus, 500 mg is recommended for postmenopausal women with HR + MBC patients who have failed previous hormone therapy. The first phase II study compared fulvestrant (500 mg/month) with the AI anastrozole (1 mg/day) in postmenopausal HR + locally advanced BC or MBC. 164 The 6-month clinical benefit rate was 72.5% for fulvestrant versus 67.0% for anastrozole. In the follow-up analysis, the median time to progression of fulvestrant was 23.4 months, anastrozole was 13.1 months. 165 Final OS analysis showed that the median OS of fulvestrant (54.1 months) was longer than anastrozole (48.4 months; hazard ratio 0.70 (95%CI 0.50-0.98]; P = 0.04). 166 The results of this study have shown for the first time that fulvestrant is more effective in first-line treatment than anastrozole. These findings suggest that fulvestrant is more effective than anastrozole in locally advanced BC or MBC patients who have not previously received ET. 167

Like TAM, fulvestrant resistance is also partly due to ESR1 mutations. ESR1 Y537S was identified as the mutation most likely to promote resistance to fulvestrant.168,169 Compared with other mutants, the ESR1 Y537 mutant requires the highest dose to completely block transcriptional activity and cell proliferation. 56 The biochemical mechanisms of fulvestrant resistance have not yet been elucidated, new SERMs or SERDs or high doses of TAM or fulvestrant may be the effective therapeutic strategies to overcome resistance associated with ESR1 mutations. 170

In addition, some miRNAs are associated with fulvestrant resistance. MiR-221/222 was up-regulated in fulvestrant resistant cell lines. 4 MiR-375, miR-21, and miR-214 may also be involved in fulvestrant resistance by regulating autophagy.171–173

Targeting ER by Selective ER Covalent Antagonistss

Selective ER covalent antagonist (SERCA) is a novel covalent ERα antagonist, and the experimental oral drug H3B-5942 is considered to be the first SERCA. H3B-5942 is capable of covalently binding cysteine residues (C530) both in ERα WT and ERα mutants, forcing ERα to fold into a unique conformation, thus effectively inhibiting ERα-dependent transcription in primary and MBC cells. In vivo, H3B-5942 showed antitumor activity superior to fulvestant therapy in BC xenograft models with ESR1 WT or ESR1 Y537S mutation. 174 Further clinical trials of H3B-5942 and development of new generation of SERCAs are currently under study.

CDK4/6 inhibitors

CDK4/6 are cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) that regulate the G1-to-S phase of the cell cycle and play a key role in ER+ BC. 175 CDK4/6 inhibitors inhibit the phosphorylation of the tumor suppressors retinoblastoma (RB) protein. This, in turn, promotes the binding of RB to E2F and blocks E2F-mediated oncogenic transcription, thereby preventing cell cycle progression from G1 phase to S phase. Three CDK4/6 inhibitors, palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib, are currently approved or in clinical trials. They are all commonly used in combination with other drugs, such as AIs and fulvestrant. Palbociclib is the first approved CDK4/6 inhibitor drug. Abemaciclib has been approved by the FDA as a monotherapy for refractory, severely pretreated ER+/HER2-MBC patients. In addition, CDK4/6 inhibitors exert anticancer effects by interfering with the immune system. CDK4/6 inhibitors enhance PD-L1 antigen presentation and cytotoxic T-cell activity in tumor cells but inhibit the proliferation of regulatory T cells, 176 suggesting that treatment with CDK4/6 inhibitors may increase response to immunotherapy. 177 CDK4/6 inhibitors have emerged as the first-line and second-line treatment of choice in postmenopausal and premenopausal/perimenopausal women with ER+/HER2− MBC. Unfortunately, up to 20% of ER+/HER2− MBC cases are intrinsically resistant to CDK4/6 inhibitors, and virtually all patients who initially respond to the drugs will develop acquired resistance. ESR1 mutations and activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway are common events in the drug-resistance.178,179 Currently, the mechanisms of intrinsic and acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors are still poorly understood. 180 Mechanism studies and combination therapy are ongoing.

Other Drugs and Combined Therapies

ET combined with a variety of targeted inhibitors has been widely tried in the clinical treatment of BC. It should be noted that the endocrine treatment is only one of the solutions of ER+ BC, chemotherapy is also clinically used to treat MBC or combined with endocrine drugs, such as capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine which has lower side effects, is approved as monotherapy for MBC patients who are resistant to paclitaxel and further anthracycline therapy. 181 For more information about chemotherapy see. 182 The inhibitors targeting ER signaling pathways have been used in combination with ET and shown to increase the sensitivity of BC treatment and prolong patients’ PFS. Three separate phase III clinical trials (PALOMA-3, Monaleesa-3 and MONARCH2) evaluated fulvestrant in combination with the CDK4/6 inhibitors palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib, respectively. The combination of fulvestrant with each of CDK4/6 inhibitors significantly extended PFS compared to fulvestrant alone.10–12 Therefore, CDK4/6 inhibitors had been approved in combination with fulvestrant for the first-line treatment of HR+/HER2− ABC or MBC with endocrine resistance. The same conclusion was achieved in a combination of CDK4/6 inhibitors with AIs in postmenopausal patients with the same disease setting. A brief summary of the endocrine and targeted drugs of BC and the details of ongoing clinical trials are presented in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Endocrine and Targeted Drugs of Breast Cancer and Their Targets.

| Drugs | Target | Stage | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane) | Aromatase | Approval (FDA) | 137,138,183 |

| Tamoxifen (SERM) | Estrogen receptor | Approval (FDA) | 144,183 |

| Fulvestrant (SERD) | Estrogen receptor | Approval (FDA) | 156,183 |

| Trastuzumab, lapatinib, pertuzumab, neratinib | HER2 | Approval (FDA) | 183 |

| Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors (palbociclib, ribociclib, abemaciclib | cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 | Approval (FDA) | 175,183 |

| Alpelisib | PI3K | Approval (FDA) | 183,184 |

| Megestrol | progesterone receptor | Approval (FDA) | 183 |

| Goserelin | GnRH receptor | Approval (FDA) | 183 |

| Pamidronate | farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase | Approval (FDA) | 183 |

| Everolimus | mTOR | Approval (FDA) | 183,185 |

| Olaparib, Talazoparib | PARP | Approval (FDA) | 183 |

| Bevacizumab | VEGF | Approval (FDA) | 183 |

| Bazedoxifene(mixed SERM/SERD) | Estrogen receptor | Clinical trial | 186 |

| H3B-5942 (SERCA) | Estrogen receptor | Clinical trial | 174 |

| Fluoxymesterone, testosterone | Androgen receptor | Clinical trial | 82 |

| Bortezomib | Proteasome | Clinical trial | 187 |

| FK228, Vorinostat | Histone deacetylase | Clinical trial | 188,189 |

| Venetoclax | BCL-2 | Clinical trial | 190 |

| Alisertib | Aurora Kinase A | Clinical trial | 191 |

| FRAX1036 | PAK1 | Clinical trial | 192 |

| Capivasertib, Ipatasertib | AKT | Clinical trial | 193,194 |

| Dasatinib, Saracatinib, Bosutinib | SRC | Clinical trial | 195 |

| Vorinostat, Entinostat, Tucidinostat | HDAC | Clinical trial | 196,197 |

| ARV-471 (Proteolysis targeting chimeras, PROTACs) | Estrogen receptor | Clinical trial | 198 |

| Buparlisib, Taselisib | PI3K | Clinical trial | 184 |

Abbreviations: SERD, selective estrogen receptor degrader; SERM, selective estrogen receptor modulator; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HER2, human epidermal growth factor 2; SERCA, selective estrogen receptor covalent antagonist; PAK1, protein-activated kinase 1; SRC, steroid receptor co-activator.

Table 4.

Ongoing Clinical Studies of Novel Drugs in ER+ BC Patients (Registered in Clinical Trials in clinical trials.gov from January 1, 2021 to August 25, 2021).

| NCT Number | Status | Conditions | Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04802759 | Recruiting |

|

|

| NCT04738292 | Recruiting |

|

|

| NCT04727632 | Recruiting |

|

|

| NCT04711252 | Recruiting |

|

|

| NCT04601116 | Recruiting |

|

|

| NCT04443348 | Recruiting |

|

|

| NCT04669587 | Recruiting |

|

|

| NCT04964934 | Recruiting |

|

|

ER, estrogen receptor; BC, breast cancer; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; LHRH, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone; +, positive; −, negative.

Conclusions

Overactivation of ERα makes ER+ BC more invasive and refractory. It is important to find out more precisely predicted and prognostic biomarkers and to develop novel drugs for ER+ BC and ET resistance therapy. To date, solutions targeting multiple mechanisms (ESR1 mutations, proteasomal inhibition, kinases, coactivators, etc) of ER biological activities have been established for the BC patients with ER+ setting as well as ET resistance. Because of in-depth exploration of ER signaling pathways, new drugs targeting these mechanisms have been developed with satisfactory results in clinic or clinical trials. In addition, the ER/AR, ER/PR or ERα/ERβ crosstalks may define novel targets for ER+ BC therapeutic innovation, especially for ET resistance. Currently, these crosstalks in ET resistance have not been fully investigated. Endocrine drugs combined with targeted inhibitors have shown to be more effective than monotherapy in clinical treatments. For example, a combination of fulvestrant with targeted inhibitors, such as CDK 4/6 or PI3K inhibitors, is a rational approach for ER+ BC treatment. The only SERD drug fulvestrant, due to its high ER binding affinity and mild side effects, is a promising endocrine drug for ER+ BC therapy, particularly for the ESR1-mutation patients with relapse on or after adjuvant AIs. However, the current limited bioavailability of intramuscular fulvestrant limits the effectiveness of the drug, and it is necessary to develop oral SERDs to overcome this limitation. In the future, the key steps in improving ET for ER+ BC are to overcome the drug resistance, discover more therapeutic targets of ER+ BC and develop more effective combination therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Wannian Yang for his critical comments on this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AF-1

activation function 1

- AF-2

transcription activation function 2

- AIs

aromatase inhibitors

- BRCA1/2

breast cancer gene 1 and 2

- CDK4/6

cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6

- CTCs

circulating tumor cells

- DBD

DNA-binding domain

- ddPCR

drop-digital polymerase chain reaction

- DFS

disease-free survival

- DOX

doxorubicin

- ER

estrogen receptor

- ERE

estrogen response element

- ET

endocrine therapy

- FGFR

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- FUL

fulvestrant

- GFR

growth factor receptor

- GPER

G-protein coupled estrogen receptor

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor 2

- HR

hormone receptor

- HSP90

heat shock protein-90

- IGF-1R

insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor

- LBD

ligand-binding domain

- LBP

ligand-binding pocket

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MBC

metastatic breast cancer

- NCoR

nuclear receptor co-repressor

- NGS

next-generation sequencing

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PIK3CA

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic alpha polypeptide gene

- PR

progesterone receptors

- PTX

paclitaxel

- RB

retinoblastoma

- SERCA

selective estrogen receptor covalent antagonist

- SERDs

selective estrogen receptor degraders

- SERMs

selective estrogen receptor modulators

- SHARPIN

shank-associated RH domain interactions protein

- SIPL1

shank-interactions protein-like1

- SRC-3

steroid receptor co-activator 3

- TAM

tamoxifen

- TF

transcription factor

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, (grant number Nos. 81871888, 82172942).

ORCID iD: Song Xia https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4327-3415

References

- 1.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M. et al. The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83(6):835‐839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646‐674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh CS. Two decades beyond BRCA1/2: homologous recombination, hereditary cancer risk and a target for ovarian cancer therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(2):343‐350. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao X, Di Leva G, Li M. et al. MicroRNA-221/222 confers breast cancer fulvestrant resistance by regulating multiple signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2011;30(9):1082‐1097. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuire WL. Current status of estrogen receptors in human breast cancer. Cancer. 1975;36(2):638‐644. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG), Davies C, . Godwin J, Gray R, et al. Relevance of breast cancer hormone receptors and other factors to the efficacy of adjuvant tamoxifen: patient-level meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):771‐784. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60993-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colleoni M, Montagna E. Neoadjuvant therapy for ER-positive breast cancers. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 10):x243‐x248. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fribbens C, O'Leary B, Kilburn L, et al. Plasma ESR1 mutations and the treatment of Estrogen receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(25):2961‐2968. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandarlapaty S, Chen D, He W, et al. Prevalence of ESR1 mutations in cell-free DNA and outcomes in metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the BOLERO-2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(10):1310‐1315. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sledge GW, Jr., Toi M, Neven P, et al. MONARCH 2: abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant in women with HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer who had progressed while receiving endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(25):2875‐2884. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, et al. Phase III randomized study of ribociclib and fulvestrant in hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer: MONALEESA-3. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(24):2465‐2472. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.9909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cristofanilli M, Turner NC, Bondarenko I, et al. Fulvestrant plus palbociclib versus fulvestrant plus placebo for treatment of hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer that progressed on previous endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3): final analysis of the multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):425‐439. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00613-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menasce LP, White GR, Harrison CJ, Boyle JM. Localization of the estrogen receptor locus (ESR) to chromosome 6q25.1 by FISH and a simple post-FISH banding technique. Genomics. 1993;17(1):263‐265. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K, et al. Human estrogen receptor beta-gene structure, chromosomal localization, and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(12):4258‐4265. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gosden JR, Middleton PG, Rout D. Localization of the human oestrogen receptor gene to chromosome 6q24—-q27 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1986;43(3-4):218‐220. doi: 10.1159/000132325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Couse JF, Lindzey J, Grandien K, Gustafsson JA, Korach KS. Tissue distribution and quantitative analysis of estrogen receptor-alpha (ERalpha) and estrogen receptor-beta (ERbeta) messenger ribonucleic acid in the wild-type and ERalpha-knockout mouse. Endocrinology. 1997;138(11):4613‐4621. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.11.5496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourguet W, Germain P, Gronemeyer H. Nuclear receptor ligand-binding domains: three-dimensional structures, molecular interactions and pharmacological implications. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21(10):381‐388. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weikum ER, Liu X, Ortlund EA. The nuclear receptor superfamily: a structural perspective. Protein Sci. 2018;27(11):1876‐1892. doi: 10.1002/pro.3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mal R, Magner A, David J, et al. Estrogen receptor Beta (ERbeta): a ligand activated tumor suppressor. Front Oncol. 2020;10(587386):587386. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.587386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Germain P, Staels B, Dacquet C, Spedding M, Laudet V. Overview of nomenclature of nuclear receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(4):685‐704. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen EV, Jordan VC. The estrogen receptor: a model for molecular medicine. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(6):1980‐1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carroll JS, Brown M. Estrogen receptor target gene: an evolving concept. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(8):1707‐1714. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahlbory-Dieker DL, Stride BD, Leder G, et al. DNA Binding by estrogen receptor-alpha is essential for the transcriptional response to estrogen in the liver and the uterus. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(10):1544‐1555. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ascenzi P, Bocedi A, Marino M. Structure-function relationship of estrogen receptor alpha and beta: impact on human health. Mol Aspects Med. 2006;27(4):299‐402. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith CL. Cross-talk between peptide growth factor and estrogen receptor signaling pathways. Biol Reprod. 1998;58(3):627‐632. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creighton CJ. The molecular profile of luminal B breast cancer. Biologics. 2012;6(30):289‐297. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S29923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katzenellenbogen BS. Biology and receptor interactions of estriol and estriol derivatives in vitro and in vivo. J Steroid Biochem. 1984;20(4B):1033‐1037. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(84)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryzgalova G, Gao H, Ahren B, et al. Evidence that oestrogen receptor-alpha plays an important role in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in mice: insulin sensitivity in the liver. Diabetologia. 2006;49(3):588‐597. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Britt K. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(11):1071‐1072. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, et al. De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen international expert consensus conference on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2017. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1700‐1712. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paterni I, Granchi C, Katzenellenbogen JA, Minutolo F. Estrogen receptors alpha (ERalpha) and beta (ERbeta): subtype-selective ligands and clinical potential. Steroids. 2014;90(4):13‐29. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwart W, de Leeuw R, Rondaij M, Neefjes J, Mancini MA, Michalides R. The hinge region of the human estrogen receptor determines functional synergy between AF-1 and AF-2 in the quantitative response to estradiol and tamoxifen. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 8):1253‐1261. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deroo BJ, Korach KS. Estrogen receptors and human disease. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(3):561‐570. doi: 10.1172/JCI27987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor transcription and transactivation: Estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta: regulation by selective estrogen receptor modulators and importance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2(5):335‐344. doi: 10.1186/bcr78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper GG, et al. Differential ligand activation of estrogen receptors ERalpha and ERbeta at AP1 sites. Science. 1997;277(5331):1508‐1510. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall JM, McDonnell DP. The estrogen receptor beta-isoform (ERbeta) of the human estrogen receptor modulates ERalpha transcriptional activity and is a key regulator of the cellular response to estrogens and antiestrogens. Endocrinology. 1999;140(12):5566‐5578. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim K, Thu N, Saville B, Safe S. Domains of estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha) required for ERalpha/Sp1-mediated activation of GC-rich promoters by estrogens and antiestrogens in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17(5):804‐817. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartella V, Rizza P, Barone I, et al. Estrogen receptor beta binds Sp1 and recruits a corepressor complex to the estrogen receptor alpha gene promoter. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):569‐581. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2090-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ignar-Trowbridge DM, Nelson KG, Bidwell MC, et al. Coupling of dual signaling pathways: epidermal growth factor action involves the estrogen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(10):4658‐4662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinton G, Thomas W, Bellini P, et al. Estrogen receptor beta exerts tumor repressive functions in human malignant pleural mesothelioma via EGFR inactivation and affects response to gefitinib. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu MM, Albanese C, Anderson CM, et al. Opposing action of estrogen receptors alpha and beta on cyclin D1 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(27):24353‐24360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tien JC, Xu J. Steroid receptor coactivator-3 as a potential molecular target for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2012;16(11):1085‐1096. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2012.718330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mc Ilroy M, Fleming FJ, Buggy Y, Hill AD, Young LS. Tamoxifen-induced ER-alpha-SRC-3 interaction in HER2 positive human breast cancer; a possible mechanism for ER isoform specific recurrence. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13(4):1135‐1145. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li BD, Byskosh A, Molteni A, Duda RB. Estrogen and progesterone receptor concordance between primary and recurrent breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1994;57(2):71‐77. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930570202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amir E, Ooi WS, Simmons C, et al. Discordance between receptor status in primary and metastatic breast cancer: an exploratory study of bone and bone marrow biopsies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2008;20(10):763‐768. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao ZX, Lu LJ, Wang RJ, et al. Discordance and clinical significance of ER, PR, and HER2 status between primary breast cancer and synchronous axillary lymph node metastasis. Med Oncol. 2014;31(1):798. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0798-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dustin D, Gu G, Fuqua SAW. ESR1 Mutations in breast cancer. Cancer. 2019;125(21):3714‐3728. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Razavi P, Chang MT, Xu G, et al. The genomic landscape of endocrine-resistant advanced breast cancers. Cancer Cell. 2018;34(3):427‐438. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fuqua SA, Gu G, Rechoum Y. Estrogen receptor (ER) alpha mutations in breast cancer: hidden in plain sight. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(1):11‐19. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2847-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barone I, Iacopetta D, Covington KR, et al. Phosphorylation of the mutant K303R estrogen receptor alpha at serine 305 affects aromatase inhibitor sensitivity. Oncogene. 2010;29(16):2404‐2414. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weis KE, Ekena K, Thomas JA, Lazennec G, Katzenellenbogen BS. Constitutively active human estrogen receptors containing amino acid substitutions for tyrosine 537 in the receptor protein. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10(11):1388‐1398. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.11.8923465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeselsohn R, Yelensky R, Buchwalter G, et al. Emergence of constitutively active estrogen receptor-alpha mutations in pretreated advanced estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(7):1757‐1767. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merenbakh-Lamin K, Ben-Baruch N, Yeheskel A, et al. D538g mutation in estrogen receptor-alpha: a novel mechanism for acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(23):6856‐6864. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fuqua SA, Wiltschke C, Zhang QX, et al. A hypersensitive estrogen receptor-alpha mutation in premalignant breast lesions. Cancer Res. 2000;60(15):4026‐4029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pejerrey SM, Dustin D, Kim JA, Gu G, Rechoum Y, Fuqua SAW. The impact of ESR1 mutations on the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Horm Cancer. 2018;9(4):215‐228. doi: 10.1007/s12672-017-0306-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toy W, Weir H, Razavi P, et al. Activating ESR1 mutations differentially affect the efficacy of ER antagonists. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(3):277‐287. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toy W, Shen Y, Won H, et al. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45(12):1439‐1445. doi: 10.1038/ng.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bahreini A, Li Z, Wang P, et al. Mutation site and context dependent effects of ESR1 mutation in genome-edited breast cancer cell models. Breast Cancer Res. 2017;19(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s13058-017-0851-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2013;45(12):1446‐1451. doi: 10.1038/ng.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lei JT, Shao J, Zhang J, et al. Functional annotation of ESR1 gene fusions in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cell Rep. 2018;24(6):1434‐1444. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Veeraraghavan J, Ma J, Hu Y, Wang XS. Recurrent and pathological gene fusions in breast cancer: current advances in genomic discovery and clinical implications. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158(2):219‐232. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3876-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hartmaier RJ, Trabucco SE, Priedigkeit N, et al. Recurrent hyperactive ESR1 fusion proteins in endocrine therapy-resistant breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(4):872‐880. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu P, Cheng H, Roberts TM, Zhao JJ. Targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(8):627‐644. doi: 10.1038/nrd2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma CX, Crowder RJ, Ellis MJ. Importance of PI3-kinase pathway in response/resistance to aromatase inhibitors. Steroids. 2011;76(8):750‐752. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller TW, Balko JM, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(33):4452‐4461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gluck S. Consequences of the convergence of multiple alternate pathways on the Estrogen receptor in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(2):79‐90. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rayala SK, Talukder AH, Balasenthil S, et al. P21-activated kinase 1 regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha activation involves serine 305 activation linked with serine 118 phosphorylation. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1694‐1701. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barone I, Cui Y, Herynk MH, et al. Expression of the K303R estrogen receptor-alpha breast cancer mutation induces resistance to an aromatase inhibitor via addiction to the PI3K/AKT kinase pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4724‐4732. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cavazzoni A, Bonelli MA, Fumarola C, et al. Overcoming acquired resistance to letrozole by targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in breast cancer cell clones. Cancer Lett. 2012;323(1):77‐87. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nayar U, Cohen O, Kapstad C, et al. Acquired HER2 mutations in ER(+) metastatic breast cancer confer resistance to estrogen receptor-directed therapies. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):207‐216. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rimawi MF, Schiff R, Osborne CK. Targeting HER2 for the treatment of breast cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66(8):111‐128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042513-015127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Katki HA. Tracking and evaluating molecular tumor markers with cancer registry data: HER2 and breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(5):1-3. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Michalides R, Griekspoor A, Balkenende A, et al. Tamoxifen resistance by a conformational arrest of the estrogen receptor alpha after PKA activation in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(6):597‐605. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yeh WL, Shioda K, Coser KR, Rivizzigno D, McSweeney KR, Shioda T. Fulvestrant-induced cell death and proteasomal degradation of estrogen receptor alpha protein in MCF-7 cells require the CSK c-src tyrosine kinase. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Panet-Raymond V, Gottlieb B, Beitel LK, Pinsky L, Trifiro MA. Interactions between androgen and estrogen receptors and the effects on their transactivational properties. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;167(1-2):139‐150. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.D'Amato NC, Gordon MA, Babbs B, et al. Cooperative dynamics of AR and ER activity in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14(11):1054‐1067. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tang Q, Chen Y, Meyer C, et al. A comprehensive view of nuclear receptor cancer cistromes. Cancer Res. 2011;71(22):6940‐6947. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Biddie SC, John S, Hager GL. Genome-wide mechanisms of nuclear receptor action. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(1):3‐9. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Majumder A, Singh M, Tyagi SC. Post-menopausal breast cancer: from estrogen to androgen receptor. Oncotarget. 2017;8(60):102739‐102758. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hickey TE, Selth LA, Chia KM, et al. The androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):310‐320. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bagnoli F, Oliveira VM, Silva MA, Taromaru GC, Rinaldi JF, Aoki T. The interaction between aromatase, metalloproteinase 2,9 and CD44 in breast cancer. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2010;56(4):472‐477. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302010000400023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Venema CM, Bense RD, Steenbruggen TG, et al. Consideration of breast cancer subtype in targeting the androgen receptor. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;200(11):135‐147. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fels E. Treatment of breast cancer with testosterone propionate. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1944;4(3):121‐125. doi: 10.1210/jcem-4-3-121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kono M, Fujii T, Lyons GR, et al. Impact of androgen receptor expression in fluoxymesterone-treated estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer refractory to contemporary hormonal therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;160(1):101‐109. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3986-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davies A, Nouruzi S, Ganguli D, et al. An androgen receptor switch underlies lineage infidelity in treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2021;23(9):1023‐1034. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00743-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kurian AW, Gong GD, John EM, et al. Performance of prediction models for BRCA mutation carriage in three racial/ethnic groups: findings from the northern California breast cancer family registry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(4):1084‐1091. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Malone KE, Daling JR, Doody DR, et al. Prevalence and predictors of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population-based study of breast cancer in white and black American women ages 35 to 64 years. Cancer Res. 2006;66(16):8297‐8308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mavaddat N, Barrowdale D, Andrulis IL, et al. Pathology of breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the consortium of investigators of modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(1):134‐147. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Antoniou AC, Kuchenbaecker KB, Soucy P, et al. Common variants at 12p11, 12q24, 9p21, 9q31.2 and in ZNF365 are associated with breast cancer risk for BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(1):R33. doi: 10.1186/bcr3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yang H, Yu S, Wang W, et al. SHARPIN Facilitates p53 degradation in breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2017;19(2):84‐92. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bii VM, Rae DT, Trobridge GD. A novel gammaretroviral shuttle vector insertional mutagenesis screen identifies SHARPIN as a breast cancer metastasis gene and prognostic biomarker. Oncotarget. 2015;6(37):39507‐39520. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.De Melo J, Tang D. Elevation of SIPL1 (SHARPIN) increases breast cancer risk. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]