Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence and associated factors of overweight and obesity among primary school children (6–11 years old) in Thanhhoa city in 2021.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Seven primary schools in Thanhhoa city, Vietnam.

Participants

782 children (and their parents).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Two-stage cluster random sampling was used for selecting children and data were collected from January to February 2021. A self-administrated questionnaire was designed for children and their parents. Children’s height and weight were measured and body mass index (BMI)-for-age z-scores were computed using the WHO Anthro software V.1.0.4. Data were analysed using R software V.4.1.2. The associations between potential factors and childhood overweight/obesity were analysed through univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. Variables were selected using the Bayesian Model Averaging method.

Results

The prevalence of overweight/obesity among primary school children in Thanhhoa city was 35.93% (overweight 21.61% and obesity 14.32%). The proportion of overweight girls was nearly equal to that of boys (20.78% and 22.52%, respectively, p=0.6152) while the proportion of boys with obesity was four times as many as that of girls (23.86% and 5.62%, respectively, p<0.0001). Child’s sex was the factor significantly associated with childhood overweight/obesity. Boys had double the risk of being overweight/obese than girls (adjusted OR: aOR=2.48, p<0.0001). Other potential factors which may be associated with childhood overweight/obesity included mode of transport to school, the people living with the child, mother’s occupation, father’s education, eating confectionery, the total time of doing sports, and sedentary activities.

Conclusion

One in every three primary school children in Thanhhoa city were either overweight or obese. Parents, teachers and policy-makers can implement interventions in the aforementioned factors to reduce the rate of childhood obesity. In forthcoming years, longitudinal studies should be conducted to determine the causal relationships between potential factors and childhood overweight/obesity.

Keywords: associated factors, primary school children, obesity, overweight, Thanhhoa city, Vietnam

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Variables in the multivariate logistic regression model were selected using the Bayesian Model Averaging method.

By reason of the growing problems involving the low reproducibility probability in recent years, a factor was only regarded as a statistically significant variable if its p value was lower than 0.001.

Causal relationships between factors and overweight/obesity cannot be determined because this is only a cross-sectional study.

Using a self-administrated questionnaire can also bring about some biases such as recall bias.

The area under the curve of the multivariate logistic regression model is not high, this model cannot be widely used to prognosticate obesity/overweight status in children.

Background

As per the WHO, ‘overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that may impair health’.1 In 2017, overweight and obesity were the rationales behind the deaths of more than 4 million people. From 1975 to 2016, the prevalence of overweight/obesity among children and adolescents aged 5–19 years rocketed from 4% to 18%.2 In 2016, globally, there were approximately 340 million overweight/obese children and adolescents aged 5–19 years.1 In the USA, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of children with overweight and class III obesity from 1999 to 2016.3 It is estimated that roughly 33% of children aged 6–11 years and 50% of adolescents aged 12–19 years will become overweight or obese in 2030.4 In almost all European countries, from 1999 to 2016, the prevalence of overweight/obesity among children aged 2–13 years was very high, especially in some Mediterranean countries. About 25% of obese children were severely obese.5 6 In Vietnam, the prevalence of overweight/obesity among children and adolescents aged 5–19 years soared from 8.5% in 2010 to 19.0% in 2020.7 Data from other countries (such as Spain,8 China,9–12 Greece,13 Poland14 and Australia15) also showed the high prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents. Generally, obesity in childhood is a worldwide epidemic requiring urgent actions and practical interventions.

From 2010 to now, globally, there has been a multitude of studies conducted to determine the prevalence and factors associated with overweight/obesity among children and adolescents.16–44 The first group of risk factors significantly associated with overweight/obesity among children is the characteristics of children and their families, including child’s sex,17–22 child’s age,18 19 21 birth order,19 overweight at birth,19 the number of siblings,19 23 school type (public/private),18 25 father/mother’s education,18 26 27 father/mother’s occupation,17 19 24 parental overweight/obesity or BMIs18 19 24 29 30 and residence (urban/rural).21 22 24 The second group is the dietary habits of children, such as food intake,29 dinner time,26 fast food, sweets, sugary/sweetened drinks17 22 25 31 and eating vegetables/fruits.29 32 Other factors include physical activities (exercises/playing sports),20 29 mode of transport to school17 26 and sedentary activities (watching television, computer game playing, sleeping).17 19 29 31 32

In Vietnam, only two previous studies were conducted in Haiphong city, Vietnam to measure the prevalence of overweight/obesity among primary school children.33 34 Thanhhoa is a province located in the central part of Vietnam. Up to now, there is no study conducted in this province to determine associated factors and the prevalence of overweight/obesity among children. This research was conducted to determine the prevalence and associated factors of childhood overweight/obesity among primary school children in Thanhhoa city in 2021. We hypothesised that the characteristics of children and their parents, children’s dietary habits, physical activities and sedentary activities are risk factors associated with overweight/obesity among children in Thanhhoa city.

Methods

This cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey was carried out in Thanhhoa city, Vietnam from 1 January to 28 Feb 2021. This city was chosen for study by reason of the following rationales. First, the first author is living in Thanhhoa city. By virtue of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, conducting a survey in this place facilitated the data-collection process. In addition, during the time for data collection, Thanhhoa city was devoid of COVID-19 patients and therefore, travel restrictions and social distancing were not applied in this city. Last but not least, the data-collection process was also much easier thanks to the close relationship between authors and leaders of the education industry in Thanhhoa.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Sample

The study population was primary school children in Thanhhoa city (grade one to five). There are 48 primary schools and about 35 000 primary school students in this city. Seven schools were randomly selected for investigation. Data were collected with the approval of the headmasters/headmistresses of these primary schools. In each school, for each grade, one class was randomly selected. All students in these selected classes were recruited in this research, excluding children with amputations or those contracting any chronic/acute health conditions. The sample size was computed using the following formula:

Deff=1+ICCx(n−1)=1+0.05 x(30−1)=2.45 (ICC: interclass correlation for the statistic (ICC=0.05), n=the average size of the clusters (approximately 30 students/class)).

p=0.221 (from a study conducted in Haiphong city, Vietnam in 201834)

Z=1.96 (α=0.05), d=0.05 (because 0.1<p<0.3)

The minimum sample size was 700 children. To increase this study’s validity and generalisability, a total of 986 children were approached. The response rate was 84.69%. However, after checking data-collection forms, 53 children were excluded from this research because of missing values (questions in the data-collection forms were not fully answered). The final sample size was 782 children, adequate to achieve a margin of error of 5%, a confidence level of 99% and a response distribution of 50%.

Questionnaire

In the light of numerous difficulties in directly interviewing children, a self-administrated questionnaire was designed for both children and their parents. Based on the questionnaires of previous studies,19 25 27 29–32 questions were selected, amended and translated into Vietnamese. Furthermore, two senior lecturers of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City aided the research team to review the questionnaire. The final questionnaire which can be seen in online supplemental file 1 included three main parts. Part 1 included questions on sociodemographic characteristics of children and parents. Part 2 focused on investigating the dietary habits of children. Part 3 included questions in relation to children’s physical and sedentary activities. To validate the questionnaire, a pilot study was conducted with the participation of 20 children and their parents. The total Cronbach’s alpha=0.85 (the dietary habits of children: 0.67, physical and sedentary activities: 0.81).

bmjopen-2021-058504supp001.pdf (54.4KB, pdf)

Data collection and anthropometric measurements

Each student was given one data-collection form and one written consent form. Students took these two forms, went home, and filled in these forms in company with their parents. Then, the teachers collected forms from their students. A week later, data collectors came back to selected classes and received data-collection forms and written consent forms from teachers.

For students having both forms, their height and weight were measured by data collectors with the aid of the teachers during playtime. Weight and height were measured for children wearing light clothing without shoes. Weight was measured in kilograms (kg) with the Microlife Weight Scale 50A (manufactured in Sweden) and rounded to the nearest 0.1 kg. Each child was measured twice and his/her weight was the average weight. If the difference between the two measurements was more than 0.1 kg, a third measurement was carried out. Height was also measured twice with a SECA 222 (a stadiometer manufactured in Germany) and recorded in metres (m) with an accuracy of 0.01 m. The WHO Anthro software V.1.0.4 was employed for anthropometric calculation. BAZs (BMI-for-age z-scores) were used to categorised children into groups: thin, normal, overweight and obese. A child was categorised as thin, overweight and obese if BAZ<−2SD, 2SD >BAZ>1 SD, and BAZ≥2 SD, respectively.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using R software V.4.1.2. The correlations between factors (independent variables) and nutritional status of children were analysed using the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test (when at least one expected value was less than 5). All variables with p values<0.2 were included in the univariate logistic regression analyses. Variables in the multivariate logistic regression model were selected using the Bayesian Model Averaging method. This model was used to adjust for confounding and explore the associations between factors (independent variables) and the nutritional status of children (dependent variable—a binary variable indicating whether or not children were overweight/obese). The goodness of fit of the multivariate logistic model was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test and the value of area under the curve (AUC). By reason of the growing problems involving low reproducibility probability in recent years, in this study, a factor was only regarded as a statistically significant variable if its p value<0.001.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics and health risk factors among primary school children

The average age of children was 8.42±1.36 years old. More than 71% of children came from public schools. Most of the children lived with both parents (88.87%) and another sibling (73.02%). The parental education levels were primarily high school and university (father: 77.36%, mother: 79.15%). The monthly income of most families was lower than 20 million Vietnam dongs (76.22%) (table 1, (online supplemental file 2).

Table 1.

Main sociodemographic characteristics and health risk factors among 782 investigated children

| No | Children’s characteristics and health risk factors | Summary statistics* | |

| 1 | Child’s sex | Male | 373 (47.70) |

| Female | 409 (52.30) | ||

| 2 | Child’s age† (months) | 101 (87–114) | |

| 3 | Grade | One | 145 (18.54) |

| Two | 159 (20.33) | ||

| Three | 177 (22.63) | ||

| Four | 170 (21.74) | ||

| Five | 131 (16.75) | ||

| 4 | School type | Public | 557 (71.23) |

| Private | 225 (28.77) | ||

| 5 | The number of children in the family (including the child in this study) | 2 (2–2) | |

| 6 | Family income per month in 2020 (million Vietnam dongs) | 10.0 (7.0–16.0) | |

| 7 | Father’s education | Under secondary | 23 (2.94) |

| Secondary | 74 (9.46) | ||

| High school | 238 (30.43) | ||

| University | 367 (46.93) | ||

| Post university | 80 (10.23) | ||

| 8 | Father’s occupation | Blue-collar worker | 515 (65.86) |

| White-collar worker | 267 (34.14) | ||

| 9 | Mother’s education | Under secondary | 18 (2.30) |

| Secondary | 81 (10.36) | ||

| High school | 215 (27.49) | ||

| University | 404 (51.66) | ||

| Post university | 64 (8.18) | ||

| 10 | Mother’s occupation | Blue-collar worker | 438 (56.01) |

| White-collar worker | 344 (43.99) | ||

| 11 | People living with the child | Child’s mother and father | 695 (88.87) |

| Only child’s father | 9 (1.15) | ||

| Only child’s mother | 36 (4.60) | ||

| Others (grandparents…) | 42 (5.37) | ||

| 12 | Eating after 20:00 | Never/rarely | 453 (57.93) |

| Sometimes | 285 (36.45) | ||

| Usually/every day | 44 (5.63) | ||

| 13 | Eating confectionery, sweet foods | Never/rarely | 125 (15.98) |

| Sometimes | 549 (70.20) | ||

| Usually/every day | 108 (13.81) | ||

| 14 | Eating fast food | Never/rarely | 332 (42.46) |

| Sometimes | 429 (54.86) | ||

| Usually/every day | 21 (2.69) | ||

| 15 | Drinking soda, soft drinks | Never/rarely | 336 (42.97) |

| Sometimes | 420 (53.71) | ||

| Usually/every day | 26 (3.32) | ||

| 16 | Time of playing sports per week (hours) | 0.83 (0–2) | |

| 17 | Time of sedentary activities (hours) | 1 (0.5–1.5) | |

Exchange rate: 1 million Vietnam dongs=42.828US$.

*Median (25th–75th percentile) for continuous variables, number (%) for categorical variables.

†Child’s age = (2020 − child’s birth year) × 12 + (12 − child’s birth month).

Rarely, 1–3 days/month or 1 day/week; Sometimes, 2–4 days/week; Usually, 5–6 days/week.

bmjopen-2021-058504supp002.pdf (72.3KB, pdf)

Regarding children’s dietary habits, most of the children had breakfast, lunch and dinner daily. Only 44 children (5.63%) usually had a meal after 20:00. About three-fifths of children ate vegetables every day/almost every day. The proportions of children usually eating confectionery and fast food were low (13.81% and 2.69%, respectively). Only 26 children (3.32%) drank soda/soft drinks more than 5 days per week. Regarding children’s physical activities, most of the children assisted their parents in doing household chores (86.57%). More than 37% of children did not play sports. Two-fifths of children played sports from one to four times per week. The average time of doing sports among children was 1.50±2.28 hours per week. Only 231 children (29.54%) went to school by themselves (walking: 9.97%, cycling: 19.57%). For sedentary activities, the proportion of children using computers/laptops for recreational activities was extremely low. The number of children watching television and using phones/tablets for more than 3 hours per day was negligible. Only 62 children (7.92%) read books, newspapers, or magazines for more than an hour per day. In general, the total time for sedentary activities of almost all children was lower than 2 hours per day (table 1, (online supplemental file 2).

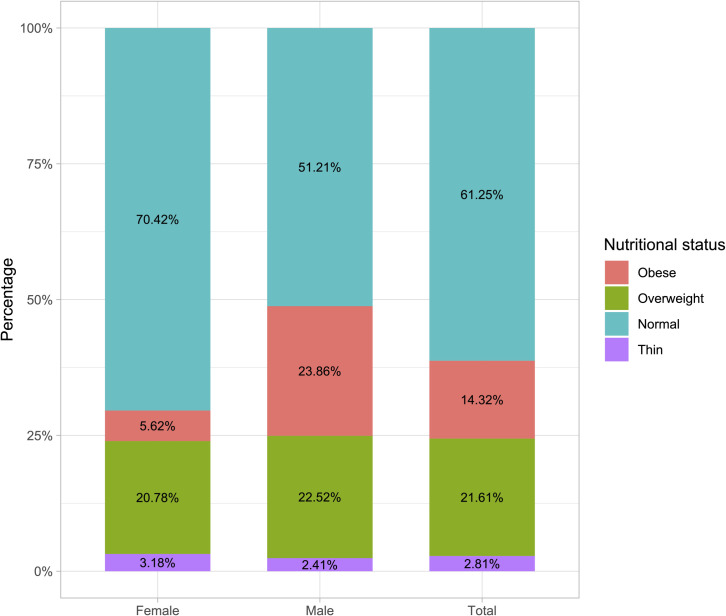

The nutritional status of children

Overall, the prevalence of overweight/obesity among primary school children in Thanhhoa city was 35.93% (overweight 21.61% and obesity 14.32%). The proportion of overweight girls (20.78%) was nearly equal to that of boys (22.52%) (p=0.6152). However, the proportion of boys with obesity (23.86%) was four times as many as that of girls (5.62%) (p<0.0001) (figure 1). In addition, the proportion of being overweight/obese among children going to school with the aid of their parents/other adults was higher than that of children walking and cycling to school (38.66%, 32.05% and 28.10%, respectively). The proportion of being overweight/obese among children whose mothers were white-collar workers was 1.36 times more likely when compared with those whose mothers were blue-collar workers (42.15% and 31.05%, respectively). A high proportion of being overweight/obese was found for children living with only fathers (88.89%) in comparison with those living with both mothers and fathers (34.24%), only mothers (47.22%), and other people (such as grandparents, aunts) (42.86%) (table 2). The association between the nutritional status of children and other factors can be seen in online supplemental file 2.

Figure 1.

The nutritional status of children classified by child’s sex.

Table 2.

The association between children’s nutritional status and factors with p values<0.2

| No | Factors (number of children) | The number of children (%) | P value | |||

| Overweight | Obesity | Overweight or obesity | ||||

| 1 | Child’s sex | Male (373) | 84 (22.52) | 89 (23.86) | 173 (46.38) | <0.0001 |

| Female (409) | 85 (20.78) | 23 (5.62) | 108 (26.41) | |||

| 2 | School type | Public (557) | 119 (21.36) | 71 (12.75) | 190 (34.11) | 0.1121 |

| Private (225) | 50 (22.22) | 41 (18.22) | 91 (40.44) | |||

| 3 | Number of children in the family | 1 (62) | 17 (27.42) | 15 (24.19) | 32 (51.61) | 0.0583 |

| 2 (571) | 118 (20.67) | 81 (14.19) | 199 (34.85) | |||

| 3 (125) | 28 (22.40) | 13 (10.40) | 41 (32.80) | |||

| >3 (24) | 6 (25.00) | 3 (12.50) | 9 (37.5) | |||

| 4 | People living with the child | Child’s mother and father (695) | 143 (20.58) | 95 (13.67) | 238 (34.24) | 0.0021* |

| Only child’s father (9) | 4 (44.44) | 4 (44.44) | 8 (88.89) | |||

| Only child’s mother (36) | 11 (30.56) | 6 (16.67) | 17 (47.22) | |||

| Others (42) | 11 (26.19) | 7 (16.67) | 18 (42.86) | |||

| 5 | Father’s education | Under secondary (23) | 2 (8.70) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (8.70) | 0.0390 |

| Secondary (74) | 19 (25.68) | 10 (13.51) | 29 (39.19) | |||

| High school (238) | 48 (20.17) | 30 (12.61) | 78 (32.77) | |||

| University (367) | 83 (22.62) | 59 (16.08) | 142 (38.69) | |||

| Post university (80) | 17 (21.25) | 13 (16.25) | 30 (37.50) | |||

| 6 | Father’s occupation | Blue-collar worker (515) | 107 (20.78) | 66 (12.82) | 173 (33.59) | 0.0693 |

| White-collar worker (267) | 62 (23.22) | 46 (17.23) | 108 (40.45) | |||

| 7 | Mother’s education | Under secondary (18) | 2 (11.11) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (11.11) | 0.0851 |

| Secondary (81) | 18 (22.22) | 8 (9.88) | 26 (32.10) | |||

| High school (215) | 45 (20.93) | 26 (12.09) | 71 (33.02) | |||

| University (404) | 90 (22.28) | 69 (17.08) | 159 (39.36) | |||

| Post university (64) | 14 (21.88) | 9 (14.06) | 23 (35.94) | |||

| 8 | Mother’s occupation | Blue-collar worker (438) | 82 (18.72) | 54 (12.33) | 136 (31.05) | 0.0017 |

| White-collar worker (344) | 87 (25.29) | 58 (16.86) | 145 (42.15) | |||

| 9 | Family income per month in 2020** | <10 (284) | 52 (18.31) | 29 (10.21) | 81 (28.52) | 0.0011 |

| 10–19.99 (312) | 70 (22.44) | 44 (14.10) | 114 (36.54) | |||

| 20–29.99 (131) | 36 (27.48) | 27 (20.61) | 63 (48.09) | |||

| 30 or more (55) | 11 (20.00) | 12 (21.82) | 23 (41.82) | |||

| 10 | Eating confectionery, sweet foods | Never/rarely (125) | 34 (27.20) | 24 (19.20) | 58 (46.40) | 0.0172 |

| Sometimes (549) | 115 (20.95) | 76 (13.84) | 191 (34.79) | |||

| Usually/every day (108) | 20 (18.52) | 12 (11.11) | 32 (29.63) | |||

| 11 | Time of playing sports | Less than 1 hour/week (393) | 76 (19.34) | 50 (12.72) | 126 (32.06) | 0.0260 |

| From 1 hour to 3 hours/week (284) | 78 (27.46) | 44 (15.49) | 122 (42.96) | |||

| More than 3 hours/week (105) | 26 (24.76) | 22 (20.95) | 48 (45.71) | |||

| 12 | Mode of transport to school | On foot (78) | 16 (20.51) | 9 (11.54) | 25 (32.05) | 0.0416 |

| Bicycle (153) | 26 (16.99) | 17 (11.11) | 43 (28.10) | |||

| Motorbike/car/bus (551) | 127 (23.05) | 86 (15.61) | 213 (38.66) | |||

| 13 | Time of sedentary activities | Less than 1 hour/day (314) | 59 (18.79) | 43 (13.69) | 102 (32.48) | 0.1763 |

| From 1 hour to 2 hours/day (398) | 85 (21.36) | 64 (16.08) | 149 (37.44) | |||

| More than 2 hours/day (70) | 25 (35.71) | 5 (7.14) | 30 (42.86) | |||

*Using Fisher’s exact test. P values were calculated using the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test to analyse the association between the nutritional status (overweight/obese and normal/thin) and risk factors.

†Unit: million Vietnam dongs. Exchange rate: 1 million Vietnam dongs=42.828US$.

Rarely, 1–3 days/month or 1 day/week; Sometimes, 2–4 days/week; Usually, 5–6 days/week.

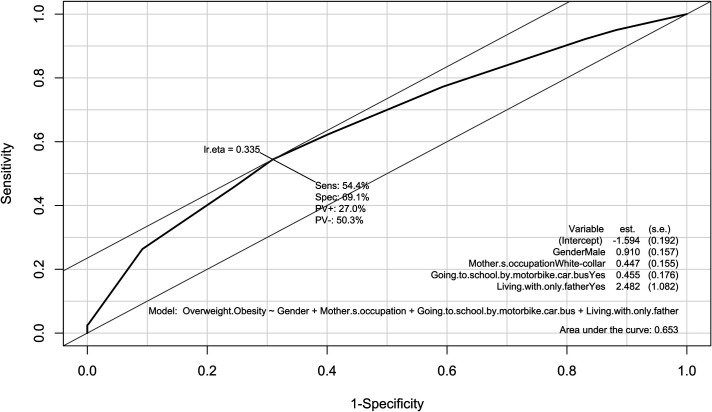

Factors associated with overweight and obesity among primary school children

The results from the univariate logistic regression model show that childhood overweight/obesity can be associated with child’s sex (p<0.0001), using a motorbike/car/bus to go to school (p=0.017), children living with only their fathers (p=0.0102), fathers with under secondary education level (p=0.030), mother’s occupation (p=0.0014), usually eating confectionery (p=0.0092), the total time of doing sports per week (p=0.0076), and the total time for sedentary activities per day (p=0.0348). The results from the multivariate logistic model show that sex, mode of transport to school, people living with the child, and mother’s occupation were several factors associated with childhood overweight/obesity. Child’s sex was the factor significantly associated with childhood overweight/obesity with p<0.0001. Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test for the multivariate logistic regression model showed that this model can adequately fit the data (χ2=2.107, df=8, p=0.9776). The AUC of the multivariate logistic regression model was 0.6525 (95% CI 0.6127 to 0.6924) (table 3 and figure 2).

Table 3.

Factors associated with overweight and obesity among primary school children in Thanhhoa City

| No | Factor | Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | ||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| 1 | Child’s sex (reference: female) | ||||

| Male | 2.41 (1.79 to 3.26) | <0.0001 | 2.48 (1.83 to 3.38) | <0.0001 | |

| 2 | School (reference: private) | ||||

| Public | 0.76 (0.55 to 1.05) | 0.0952 | |||

| 3 | The number of children in the family (continuous variable) | ||||

| Per child | 0.80 (0.62 to 1.01) | 0.0694 | |||

| 4 | Mode of transport to school (reference: bicycle) | ||||

| On foot | 1.21 (0.66 to 2.17) | 0.534 | |||

| Motorbike/car/bus | 1.61 (1.10 to 2.40) | 0.017 | 1.58 (1.12 to 2.23) | 0.0096 | |

| 5 | People living with the child (reference: both child’s mother and father) | ||||

| Only child’s father | 15.36 (2.80 to 285.83) | 0.0102 | 11.96 (2.07 to 226.84) | 0.0219 | |

| Only child’s mother | 1.72 (0.87 to 3.37) | 0.1149 | |||

| Others (grandparents…) | 1.44 (0.76 to 2.70) | 0.2572 | |||

| 6 | Father’s education (reference: high school) | ||||

| Under secondary | 0.20 (0.03 to 0.69) | 0.030 | |||

| Secondary | 1.32 (0.77 to 2.26) | 0.311 | |||

| University | 1.29 (0.92 to 1.83) | 0.140 | |||

| Post university | 1.23 (0.72 to 2.08) | 0.440 | |||

| 7 | Father’s occupation (reference: blue-collar worker) | ||||

| White-collar worker | 1.34 (0.99 to 1.82) | 0.0584 | |||

| 8 | Mother’s occupation (reference: blue-collar worker) | ||||

| White-collar worker | 1.62 (1.21 to 2.17) | 0.0014 | 1.56 (1.15 to 2.12) | 0.0040 | |

| 9 | Mother’s education (reference: high school) | ||||

| Under secondary | 0.25 (0.04 to 0.92) | 0.0724 | |||

| Secondary | 0.96 (0.55 to 1.64) | 0.8799 | |||

| University | 1.32 (0.93 to 1.87) | 0.1210 | |||

| Post university | 1.14 (0.63 to 2.03) | 0.6651 | |||

| 10 | Family income (continuous variable) | ||||

| Per one million Vietnam dongs | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) | 0.0563 | |||

| 11 | Eating confectionery/sweet foods (reference: Never/Rarely) | ||||

| Sometimes | 0.62 (0.42 to 0.91) | 0.0158 | |||

| Usually/Every day | 0.49 (0.28 to 0.83) | 0.0092 | |||

| 12 | The time of doing sports per week (continuous variable) | ||||

| Per hour | 1.09 (1.02 to 1.16) | 0.0076 | |||

| 13 | The time for sedentary activities per day (continuous variable) | ||||

| Per hour | 1.19 (1.01 to 1.41) | 0.0348 | |||

The multivariate logistic regression model was chosen using the Bayesian Model Averaging method.

Analysing the relation between two categorical variables was done using Cramer’s V. V-values were lower than 0.08 for all pairs of variables in the multivariate logistic regression model. Multicollinearity did not occur in this model.

Exchange rate: 1 million Vietnam dongs=42.828US$.

aOR, adjusted OR.

Figure 2.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for the multivariate logistic regression model.

Discussion

This is the first study conducted in Thanhhoa city to determine the prevalence and risk factors associated with overweight/obesity among primary school children. The results show that among 782 investigated children, 281 children (35.93%) were overweight/obese, congruent with the results of several studies conducted in urban areas/cities in Port Said (2011): 31.2%35; Uberaba, Brazil (2012–2013): 32.3%36; Ankara, Turkey (2015): 35.9%27; and New Zealand (2017–2018): 31.9%.37 The prevalence of overweight/obesity among primary school children in Thanhhoa is lower than the results of Hochiminh city, Vietnam (2014–2015): 55.6%38 but far higher than the results of Rikuzentakata, Japan (2013): 7.8%39; Guangzhou, China (2014): 18.2%18; Chocó, Colombia (2015): 13.2%40; Lomé, Togo (2015): 7.1%32; Nepal (2017): 25.7%17; and Abidjan, Ivory Coast (2018): 10.2%.41 Therefore, the epidemic of overweight/obesity among primary school children can be regarded as a matter of concern in Thanhhoa city.

Child’s sex was the risk factor significantly associated with overweight/obesity among children in Thanhhoa. The odds of being overweight/obese among boys was 2.48 times more likely when compared with girls (p<0.0001), in line with the results from studies conducted in urban Nepal,17 Montenegro,19 China11 18 and Iran.42 By contrast, in some other countries, girls were more likely to be overweight/obese than boys, for example, in Ethiopia28 and Ivory Coast.41 In Brazil, there was no difference in obesity prevalence between boys and girls (p>0.05).43 There were several possible rationales behind the higher prevalence of overweight/obesity among boys than girls in Thanhhoa city. First, in comparison with girls, the average time (minutes per day) for sedentary activities of boys (73.12) was higher than girls (67.77), including watching television: 37.45 and 32.28, using computers/phones/tablets: 19.65 and 16.79, respectively. This reason was also reported in previous studies in Montenegro19 and Columbia.45 In addition, in many countries, male chauvinism is still rife. In Vietnam, many parents hold a belief that girls are less valuable than boys and strong fertility desire commonly appears in families without sons.46 As a result, parents usually cosset their sons more than their daughters. Another possible reason is that boys consumed unhealthy foods (such as fast food) more frequently than girls,47 thereby being able to increase the risk of being overweight/obese. In this study, we only asked children’s parents about the frequency of consuming fast food, confectionery and soda. Future studies should focus on the total intakes of these unhealthy foods to assess their effects on children’s nutritional status more specifically.

Besides sex, three other risk factors which could be associated with childhood overweight/obesity included transportation to school, the mother’s occupation, and the people living with the child. In Nepal, the mother’s occupation was also the risk factor significantly associated with childhood overweight/obesity (p<0.001).17 Regarding transportation to school, the percentage of children who walked/cycled to school in Thanhhoa (29.54%) was far lower than the result of Lomé, Togo (90.1%)32 and Port Said city (47.3%).35 In Thanhhoa, children going to school with the aid of parents/other adults had more risks of being overweight/obese than those going to school by themselves, in line with the result of a study in Nepal.17 For the factor involving people living with the child, 88.87% of children in Thanhhoa lived with both parents, similar to the result of Montenegro (91.11%).19 By virtue of the low divorce rate, the number of children living with only a father/mother was extremely low (9 and 36 cases, respectively). This can affect the accuracy and the reproducibility of results involving this factor. It is necessary to carry out other studies to reanalyse the effect of this factor on the prevalence of being overweight/obese among children.

Besides the four abovementioned factors, the results from univariate logistic regression show that father’s education, confectionery consumption, the time of doing sports, and the time for sedentary activities can be risk factors associated with overweight/obesity among children in Thanhhoa city. In Hanoi, Vietnam, the father’s education may be a factor associated with the prevalence of overweight/obesity among children (p=0.05).29 For sugary/sweetened foods, the proportion of children eating confectionery more than five times/week in Thanhhoa was 13.81%, in line with the result of Nepal (16.9%)17 but lower than the result of Sharjah, UAE (54.6%).31 In lieu of overweight/obese children having a higher consumption of confectionery, our results showed a reverse association. In comparison with children never/rarely eating confectionery, the odds of being overweight/obese were, respectively, 38% and 51% lower than that of children sometimes and usually/every day eating confectionery, in line with the result of a systematic review and meta-analysis.48 Although eating chocolate and sugar candies may not have pernicious effects on children’s health,49 excessive consumption of these types of foods is unnecessary and detrimental in some cases.

Regarding sedentary activities, in Thanhhoa, the OR for being overweight/obese increased 19% for a 1 hour increase in the total time of sedentary activities (p=0.0348). In Nepal, sedentary activities were the factor significantly associated with overweight/obesity among children: children spending>2 hours a day on weekends on sedentary activities were three times more likely to be overweight/obese than those spending≤2 hours a day on weekends.17 Several previous studies having the same results include Lomé, Togo32 and Montenegro.19 For physical activities, playing sports was not the predilection of many primary school children in Thanhhoa. Only 25.58% of children played sports more than three times/week, far lower than the result of China (physical activities≥4 times/week: 45.05%).30 There is no denying that physical activities such as doing exercises and playing sports play an important role in helping people to lose weight and keep fit, thereby improving people’s health. Children in Thanhhoa city should spend more time doing these beneficial activities.

Our results showed that overweight/obesity should be a problematic matter of concern by virtue of the high prevalence of overweight/obesity among primary school children in Thanhhoa city. By reason of the fairly low AUC, the multivariate logistic regression model cannot be widely used to prognosticate obesity/overweight status in children. However, parents, teachers, and policymakers can implement interventions in factors (such as eating confectionery, playing sports, and sedentary activities) to reduce the rate of childhood obesity. Sports and sedentary activities were associated with dietary patterns and the quality of food choices which can help prevent childhood obesity.50

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study conducted to investigate the prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity among primary school children in Thanhhoa province. In this study, only p-values less than 0.001 were considered statistically significant by reason of the growing problems involving the low reproducibility probability in recent years. Variables in the multivariate logistic regression model were selected using the Bayesian Model Averaging method.

Besides the aforementioned strengths, this study has some following limitations. First, causal relationships between risk factors and overweight/obesity cannot be determined because this is only a cross-sectional study. Second, using a self-administrated questionnaire to collect data can bring about some biases such as recall bias. For factors involving children’s dietary habits, we only gather information on the frequency of the meals. Further studies should focus on collecting data on the total intake of various kinds of foods that are strongly associated with overweight/obesity (the portion size). Some factors such as child’s birth weight and parental BMIs which may be strongly associated with children’s overweight and obesity were not collected. Third, the height of children should be measured in centimetres with an accuracy of 0.1 cm, instead of metres with an accuracy of 0.01 m. Last but not least, the AUC of the multivariate logistic regression model is not high; this model cannot be widely used to predict obesity/overweight status in children.

Conclusion

One in every three primary school children in Thanhhoa city were either overweight or obese. Besides sex, the significantly associated factor, other potential factors which may be associated with childhood overweight/obesity included mode of transport to school, the people living with the child, mother’s occupation, father’s education, eating confectionery, the time of playing sports and sedentary activities. Parents, teachers and policy-makers can implement interventions in these factors to reduce the rate of childhood obesity. In forthcoming years, longitudinal studies should be conducted to determine the causal relationships between potential factors and childhood overweight/obesity.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GBL: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, software, data curation, project administration, writing – review & editing. DXD: methodology, investigation, software, formal analysis, data curation, visualisation, supervision, project administration, validation, writing – original draft preparation, writing – review and editing. GBL is the author responsible for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author (dinhxuandai.224@gmail.com) if you are interested in accessing data from our research.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study proposal was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (number 914/HĐĐĐ-ĐHYD). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Obesity and overweight. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [Accessed 11 Feb 2022].

- 2.World Health Organization . Obesity. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/obesity#tab=tab_1 [Accessed 11 Feb 2022].

- 3.Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, et al. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in US children, 1999-2016. Pediatrics 2018;141:e20173459. 10.1542/peds.2017-3459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Min J, et al. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol 2020;49:810–23. 10.1093/ije/dyz273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrido-Miguel M, Cavero-Redondo I, Álvarez-Bueno C, et al. Prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity in European children from 1999 to 2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2019;173:e192430. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinelli A, Buoncristiano M, Kovacs VA, et al. Prevalence of severe obesity among primary school children in 21 European countries. Obes Facts 2019;12:244–58. 10.1159/000500436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vietnam Ministry of Health . The Ministry of health announced the results of the nutrition census during 2019-2020. Available: https://moh.gov.vn/tin-noi-bat/-/asset_publisher/3Yst7YhbkA5j/content/bo-y-te-cong-bo-ket-qua-tong-ieu-tra-dinh-duong-nam-2019-2020 [Accessed 11 Feb 2022].

- 8.de Bont J, Díaz Y, Casas M, et al. Time trends and sociodemographic factors associated with overweight and obesity in children and adolescents in Spain. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e201171. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin W, Wang L, Xu L, et al. An exploratory spatial analysis of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in Shandong, China. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028152. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang X, Zhang F, Yang J, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among primary school-aged children in Jiangsu Province, China, 2014-2017. PLoS One 2018;13:e0202681. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan R, Kou C, Jie J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of overweight and obesity among adolescents in northeastern China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e036820. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song Y, Wang H-J, Dong B, et al. 25-year trends in gender disparity for obesity and overweight by using WHO and IOTF definitions among Chinese school-aged children: a multiple cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011904. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kosti RI, Kanellopoulou A, Fragkedaki E, et al. The influence of adherence to the Mediterranean diet among children and their parents in relation to childhood Overweight/Obesity: a cross-sectional study in Greece. Child Obes 2020;16:571–8. 10.1089/chi.2020.0228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Żegleń M, Kryst Łukasz, Kowal M, et al. Changes in the prevalence of overweight/obesity and adiposity among pre-school children in Kraków, Poland, from 2008 to 2018. J Biosoc Sci 2020;52:895–906. 10.1017/S0021932019000853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australia’s children. Available: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/australias-children/contents/health/overweight-and-obesity [Accessed 11 Feb 2022].

- 16.Dereń K, Nyankovskyy S, Nyankovska O, et al. The prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in children and adolescents from Ukraine. Sci Rep 2018;8:3625. 10.1038/s41598-018-21773-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karki A, Shrestha A, Subedi N. Prevalence and associated factors of childhood overweight/obesity among primary school children in urban Nepal. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1055. 10.1186/s12889-019-7406-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu W, Liu W, Lin R, et al. Socioeconomic determinants of childhood obesity among primary school children in Guangzhou, China. BMC Public Health 2016;16:482. 10.1186/s12889-016-3171-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinovic M, Belojevic G, Evans GW, et al. Prevalence of and contributing factors for overweight and obesity among Montenegrin schoolchildren. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:833–9. 10.1093/eurpub/ckv071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gunter KB, Nader PA, John DH. Physical activity levels and obesity status of Oregon rural elementary school children. Prev Med Rep 2015;2:478–82. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muhihi AJ, Mpembeni RNM, Njelekela MA, et al. Prevalence and determinants of obesity among primary school children in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Arch Public Health 2013;71:26. 10.1186/0778-7367-71-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen T, Sokal-Gutierrez K, Lahiff M, et al. Early childhood factors associated with obesity at age 8 in Vietnamese children: the young lives cohort study. BMC Public Health 2021;21:301. 10.1186/s12889-021-10292-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koirala M, Khatri RB, Khanal V, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with childhood overweight/obesity of private school children in Nepal. Obes Res Clin Pract 2015;9:220–7. 10.1016/j.orcp.2014.10.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oddo VM, Maehara M, Rah JH. Overweight in Indonesia: an observational study of trends and risk factors among adults and children. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031198. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosha MV, Msuya SE, Kasagama E, et al. Prevalence and correlates of overweight and obesity among primary school children in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania. PLoS One 2021;16:e0249595. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mwaikambo SA, Leyna GH, Killewo J, et al. Why are primary school children overweight and obese? A cross sectional study undertaken in Kinondoni district, Dar-es-salaam. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1269. 10.1186/s12889-015-2598-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yardim MS, Özcebe LH, Araz OM, et al. Prevalence of childhood obesity and related parental factors across socioeconomic strata in Ankara, Turkey. East Mediterr Health J 2019;25:374–84. 10.26719/emhj.18.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gebrie A, Alebel A, Zegeye A, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of overweight/ obesity among children and adolescents in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Obes 2018;5:19. 10.1186/s40608-018-0198-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pham TTP, Matsushita Y, Dinh LTK, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of overweight and obesity among schoolchildren in Hanoi, Vietnam. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1478. 10.1186/s12889-019-7823-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo X, Zheng L, Li Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of being overweight or obese among children and adolescents in northeast China. Pediatr Res 2013;74:443–9. 10.1038/pr.2013.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abduelkarem AR, Sharif SI, Bankessli FG, et al. Obesity and its associated risk factors among school-aged children in Sharjah, UAE. PLoS One 2020;15:e0234244. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sagbo H, Ekouevi DK, Ranjandriarison DT, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity among children from primary schools in urban areas of Lomé, Togo. Public Health Nutr 2018;21:1048–56. 10.1017/S1368980017003664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ngan HTD, Tuyen LD, Phu PV, et al. Childhood overweight and obesity amongst primary school children in Hai Phong City, Vietnam. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2018;27:399–405. 10.6133/apjcn.062017.08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoang N, Orellana L, Le T, et al. Anthropometric status among 6–9-Year-Old school children in rural areas in HAI Phong City, Vietnam. Nutrients 2018;10:1431. 10.3390/nu10101431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badawi NE-S, Barakat AA, El Sherbini SA, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in primary school children in Port said City. Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette 2013;61:31–6. 10.1016/j.epag.2013.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva APda, Feilbelmann TCM, Silva DC, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and associated factors in school children and adolescents in a medium-sized Brazilian City. Clinics 2018;73:e438. 10.6061/clinics/2018/e438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiavaroli V, Gibbins JD, Cutfield WS, et al. Childhood obesity in New Zealand. World J Pediatr 2019;15:322–31. 10.1007/s12519-019-00261-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mai TMT, Pham NO, Tran TMH, et al. The double burden of malnutrition in Vietnamese school-aged children and adolescents: a rapid shift over a decade in Ho Chi Minh City. Eur J Clin Nutr 2020;74:1448–56. 10.1038/s41430-020-0587-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moriyama H, Fuchimukai T, Kondo N, et al. Obesity in elementary school children after the Great East Japan earthquake. Pediatr Int 2018;60:282–6. 10.1111/ped.13468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Botero-Meneses JS, Aguilera-Otalvaro PA, Pradilla I, et al. Assessment of nutrition and learning skills in children aged 5-11 years old from two elementary schools in Chocó, Colombia. Heliyon 2020;6:e03821. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fossou AF, Ahui Bitty ML, Coulibaly TJ, et al. Prevalence of obesity in children enrolled in private and public primary schools. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020;40:115–20. 10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghadimi R, Asgharzadeh E, Sajjadi P. Obesity among elementary schoolchildren: a growing concern in the North of Iran, 2012. Int J Prev Med 2015;6:99. 10.4103/2008-7802.167177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aiello AM, Marques de Mello L, Souza Nunes M, et al. Prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents in Brazil: a meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Curr Pediatr Rev 2015;11:36–42. 10.2174/1573396311666150501003250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bilińska I, Kryst Łukasz. Effectiveness of a school-based intervention to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children aged 7-11 years from Poznań (Poland). Anthropol Anz 2017;74:89–100. 10.1127/anthranz/2017/0719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taverno Ross SE, Byun W, Dowda M, et al. Sedentary behaviors in fifth-grade boys and girls: where, with whom, and why? Child Obes 2013;9:532–9. 10.1089/chi.2013.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yen NTH, Sukontamarn P, Dang TNH. Sex-Composition of living children and women's fertility desire in Vietnam. J Family Reprod Health 2020;14:234–41. 10.18502/jfrh.v14i4.5204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Psarra G, et al. Association between fast-food consumption and lifestyle characteristics in Greek children and adolescents; results from the EYZHN (National action for children's health) programme. Public Health Nutr 2018;21:3386–94. 10.1017/S1368980018002707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gasser CE, Mensah FK, Russell M, et al. Confectionery consumption and overweight, obesity, and related outcomes in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103:1344–56. 10.3945/ajcn.115.119883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Neil CE, Fulgoni VL, Nicklas TA. Association of candy consumption with body weight measures, other health risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and diet quality in US children and adolescents: NHANES 1999-2004. Food Nutr Res 2011;55. 10.3402/fnr.v55i0.5794. [Epub ahead of print: 14 06 2011]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanellopoulou A, Diamantis DV, Notara V, et al. Extracurricular sports participation and sedentary behavior in association with dietary habits and obesity risk in children and adolescents and the role of family structure: a literature review. Curr Nutr Rep 2021;10:1–11. 10.1007/s13668-021-00352-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058504supp001.pdf (54.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-058504supp002.pdf (72.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author (dinhxuandai.224@gmail.com) if you are interested in accessing data from our research.