Abstract

African Americans suffer from higher colorectal cancer morbidity and mortality than do Whites, yet have the lowest screening rates. To understand barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening, this study used perceptual mapping (multidimensional scaling) methods to compare patients’ perceptions of colonoscopy and general preventive health practices to those of their doctors in a general internal medicine clinic in a large urban hospital. African American patients (n = 102) were surveyed about their own screening beliefs; third-year resident physicians (n = 29) were asked what they perceived their patients believed. The perceptual maps showed significant differences between the patients’ and physicians’ perceptions of barriers, facilitators, and beliefs about screening. Physicians believed logistical lifestyle issues were the greatest screening barriers for their patients whereas fears of complications, pain, and cancer were the most important barriers perceived by patients. Physicians also underestimated patients’ understanding of the benefits and importance of screening, doctors’ recommendations, and beliefs that faith in God could facilitate screening. Physicians and patients perceived a doctor’s recommendation for screening was an important facilitator. Better understanding of patient perceptions can be used to improve doctor–patient communication and to improve medical resident training by incorporating specific messages tailored for use with African American patients.

Colorectal cancer (CRC), the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, resulted in almost 50,000 deaths in 2009 (American Cancer Society, 2010b). Despite increased screening rates, African Americans have disproportionate rates of morbidity and mortality (American Cancer Society, 2010b; Khankari et al., 2007). CRC screening, specifically colonoscopy, is recommended for all adults older than 50 years of age (Byers, Levin, Rothenberger, Dodd, & Smith, 1991; Pignone, Rich, Teutsch, Berg, & Lohr, 2002; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2002) because 5-year CRC survival rates are up to 90% when detected and treated early (Horner et al., 2010). Although more than 45% of eligible Americans have been screened in the past 5 years (American Cancer Society, 2010a), almost 60% of African Americans have never been screened (American Cancer Society, 2010a).

Research has shown that both patients and physicians have perceptions about CRC screening that impede shared agreement about its preventive value. The common factors that affect a patient’s decision to be screened include (a) knowledge of CRC and screening modalities (Geller et al., 2008; Jorgensen, Gelb, Merritt, & Seeff, 2001); (b) physician recommendations (Cairns & Viswanath, 2006); (c) health insurance coverage (Cairns & Viswanath, 2006); and (d) perceptions that screening is unpleasant, inconvenient (McCaul & Tulloch, 1999), uncomfortable, embarrassing, scary, or anxiety producing (Beeker, Kraft, Southwell, & Jorgensen, 2000; Green & Kelly, 2004; Holmes-Rovner et al., 2002). African American patients in particular face barriers such as lack of trust in the health care system and in health providers (Carcaise-Edinboro & Bradley, 2008; Greiner, Born, Nollen, & Ahluwalia, 2005; James, Campbell, & Hudson, 2002; Katz et al., 2004); lack of ability to pay for screening (Peterson et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2003); embarrassment (Greiner et al., 2005; McAlearney et al., 2008); and fatalistic beliefs (i.e., that screening and treatments are futile because the future is in God’s hands; Green & Kelly, 2004; Greiner et al., 2005).

Studies about the role of physicians in encouraging CRC screening have confirmed that some physicians are uncomfortable speaking to patients about screening, particularly colonoscopy (Guerra et al., 2007; Oxentenko et al., 2007); fail to promote screenings per recommended guidelines (Barrison, Smith, Oviedo, Heeren, & Schroy Iii, 2003; Dulai et al., 2004; Gorin et al., 2007); lack knowledge about CRC screening (Gennarelli et al., 2005; Oxentenko et al., 2007; Sharma et al., 2000); do not have enough time with patients to discuss screening options (Guerra et al., 2007); have difficulty scheduling screenings (Zack, DiBaise, Quigley, & Roy, 2001); prescribe screenings other than colonoscopy based on personal attitudes about specific screening tests (Schroy et al., 2001); and are least likely to promote colonoscopy to patients from lower socioeconomic areas (Gorin et al., 2007).

Although studies have addressed barriers to CRC screening for African Americans, no previous work has compared patient to physician perceptions of barriers to CRC screening. In particular, no published study has ascertained physicians’ perceptions of what patients view as barriers to colonoscopy and then compared them to what their patients actually view as barriers. Discordance in perception of barriers might be especially important to understand for African American populations and could be an essential first step toward understanding how to improve physician-patient communication about colonoscopy. This study was designed specifically to compare patients’ beliefs and perceptions of barriers to colonoscopy to those of their doctors. Thus, it fills an important gap in the literature and provides an empirical basis for how it may be possible to improve physician–patient communication to facilitate colonoscopy.

Method

To assess possible differences in perceptions about colonoscopy among African American patients compared with what their physicians perceived their patients believed, we surveyed patients and third-year resident physicians who received care or who worked in a general internal medicine clinic in a large urban teaching hospital that primarily serves low-income African Americans who have Medicare or Medicaid insurance. Patients and physicians were asked a series of fixed-choice questions about the beliefs, risks, benefits, and barriers they perceived to be associated with colonoscopy screening (see Table 1). Patients were asked about their own beliefs; physicians were asked what they perceived their patients to believe for each element. The Temple University Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and methods for maintaining anonymity.

Table 1.

Patients’ perceptions of colonoscopy screening

| Question/statement issues | Respondent | N | s | t | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question grouping 1: Barriers to colonoscopy screening | |||||||

| 1. Cost of having a colon screening test | Patient | 99 | 1.81 | 3.19 | −2.109 | 66.837 | .039 |

| Physician | 29 | 2.90 | 2.18 | ||||

| 2. Getting someone to take me to and from | Patient | 102 | 1.82 | 2.83 | −9.969 | 76.444 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.03 | 1.70 | ||||

| 3. Taking time off from work to get screened | Patient | 102 | .76 | 1.97 | −11.511 | 48.060 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.28 | 1.83 | ||||

| 4. Finding someone to care for children/grandchildren | Patient | 102 | 1.28 | 2.55 | −8.206 | 48.100 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.45 | 2.37 | ||||

| 5. Finding someone to care for adults I take care of | Patient | 102 | 1.25 | 2.50 | −8.083 | 51.162 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.07 | 2.17 | ||||

| 6. Preparing for the test is too much bother | Patient | 102 | 2.99 | 2.92 | −10.287 | 74.889 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 7.52 | 1.79 | ||||

| 7. Test is so unfamiliar, I don’t want to do it | Patient | 102 | 2.78 | 3.63 | −8.172 | 76.571 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 7.21 | 2.17 | ||||

| 8. Would find the test to be too embarrassing | Patient | 101 | 2.67 | 3.46 | −7.007 | 65.879 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.59 | 2.37 | ||||

| 9. Don’t think it is the best method for detection | Patient | 102 | 2.15 | 2.62 | −0.651 | 56.264 | .518 |

| Physician | 29 | 2.45 | 2.06 | ||||

| 10. Scares me I could find out I have cancer | Patient | 102 | 3.08 | 3.55 | −5.035 | 77.657 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.72 | 2.10 | ||||

| 11. Worry about medicine to make me sleepy | Patient | 102 | 1.72 | 2.94 | −6.409 | 68.008 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 4.69 | 1.95 | ||||

| 12. Concerned screening might be painful | Patient | 102 | 3.98 | 3.93 | −7.202 | 117.481 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 7.45 | 1.53 | ||||

| 13. Am worried about serious complication | Patient | 102 | 3.59 | 3.21 | −2.298 | 62.938 | .005 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.14 | 2.28 | ||||

| Question grouping 2: Facilitators to colonoscopy screening | |||||||

| 1. Colonoscopy is the most accurate way to check | Patient | 97 | 9.01 | 1.72 | 7.185 | 43.069 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.21 | 1.88 | ||||

| 2. Good way to find colon or rectal cancer early | Patient | 97 | 8.89 | 1.77 | 7.193 | 51.745 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.45 | 1.55 | ||||

| 3. Can remove growths before becoming cancer | Patient | 97 | 8.44 | 1.85 | 5.631 | 52.002 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.45 | 1.62 | ||||

| 4. Doesn’t have to be done as often as other tests | Patient | 97 | 7.10 | 2.37 | 1.758 | 59.684 | .084 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.38 | 1.80 | ||||

| 5. Peace of mind from knowing is good reason | Patient | 99 | 9.32 | 1.61 | 10.639 | 50.323 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.00 | 1.44 | ||||

| 6. Like that the test is recommended by doctors | Patient | 99 | 9.15 | 1.58 | 9.009 | 46.327 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.17 | 1.56 | ||||

| 7. Should have if my health insurance covers the cost | Patient | 99 | 8.94 | 1.77 | 7.150 | 46.373 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.31 | 1.73 | ||||

| 8. Getting medicine to make me sleepy is a plus | Patient | 99 | 9.15 | 1.78 | 6.059 | 42.280 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.69 | 1.97 | ||||

| Question Grouping 3: Preventive Health Practices/Beliefs | |||||||

| 1. I don’t go to the doctor unless I really need to | Patient | 102 | 4.70 | 3.77 | −2.867 | 103.321 | .005 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.10 | 1.71 | ||||

| 2. My body will let me know when I need to be tested | Patient | 102 | 6.58 | 3.22 | −0.180 | 99.929 | .857 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.66 | 1.52 | ||||

| 3. Don’t want tests unless something is wrong | Patient | 102 | 4.82 | 3.62 | −4.080 | 106.327 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.72 | 1.60 | ||||

| 4. I’d rather not know if I have cancer | Patient | 102 | 2.51 | 3.68 | −5.478 | 84.648 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.38 | 2.03 | ||||

| 5. Fear of cancer keeps me from getting tests I should | Patient | 101 | 2.50 | 3.41 | −5.524 | 80.791 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.24 | 1.96 | ||||

| 6. If I get cancer, I accept that it is the will of God. | Patient | 102 | 7.47 | 3.82 | −4.237 | 68.132 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.41 | 2.03 | ||||

| 7. Many tests aren’t very good at finding problems | Patient | 101 | 2.48 | 2.42 | 3.854 | 88.230 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 4.10 | 1.61 | ||||

| 8. Only have colonoscopy if family/friend told me to | Patient | 102 | 1.76 | 3.08 | −6.702 | 66.398 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.07 | 2.09 | ||||

| 9. Only have colonoscopy if doctor I trusted told me to | Patient | 102 | 8.46 | 3.10 | 3.812 | 79.053 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 6.72 | 1.81 | ||||

| 10. I think a colonoscopy is well worth the effort | Patient | 102 | 8.43 | 2.42 | 8.377 | 89.605 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.62 | 1.27 | ||||

| 11. To avoid getting sick, I try to do screening tests | Patient | 102 | 8.60 | 2.00 | 8.918 | 51.323 | .000 |

| Physician | 29 | 5.24 | 1.73 | ||||

Perceptual Mapping

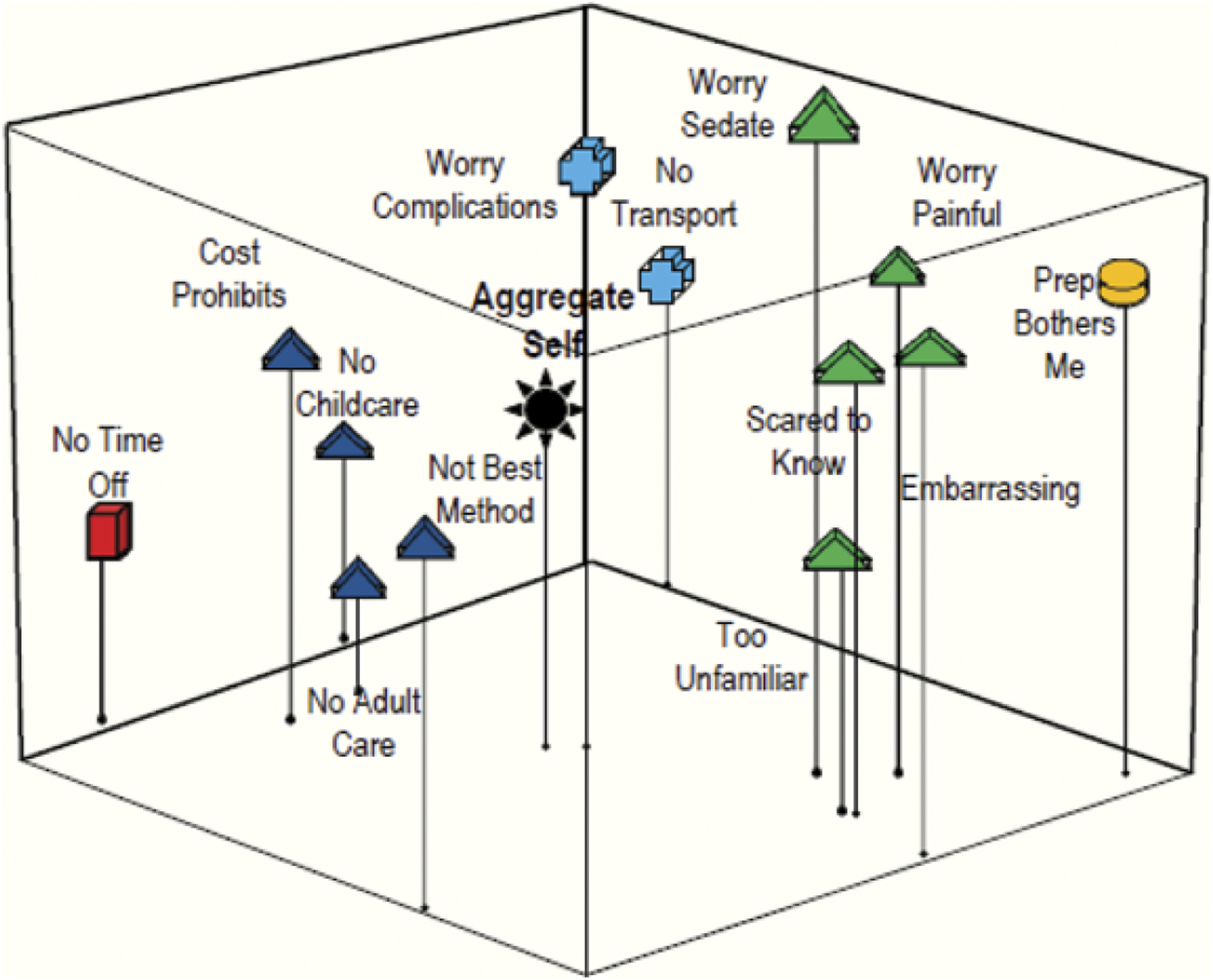

Data were collected and analyzed using perceptual mapping methods that use multidimensional scaling and message vector modeling techniques to design risk communication messages. Advances in modeling and theory development allow us to produce a graphic display of how participants perceive the relation among a set of elements (e.g. risks and benefits). The resulting maps (see Figures 1–6) show how patients and physicians conceptualize the key elements relative to each other and relative to an aggregate self. In a perceptual map, a self can be positioned in the model either as an individual (if the map is based on only one person) or as a group/sample average aggregate self where data are combined for multiple respondents. The ability to construct and analyze maps for segmented representative subgroups is critical for extracting information needed for targeting and tailoring messages (Bass, Gordon, Ruzek, & Hausman, 2008). (Methodological details about perceptual mapping techniques used in this study are available at: http://chpsw.temple.edu/publichealth/research-centers-and-labs/risk-communication-laboratory-rcl)

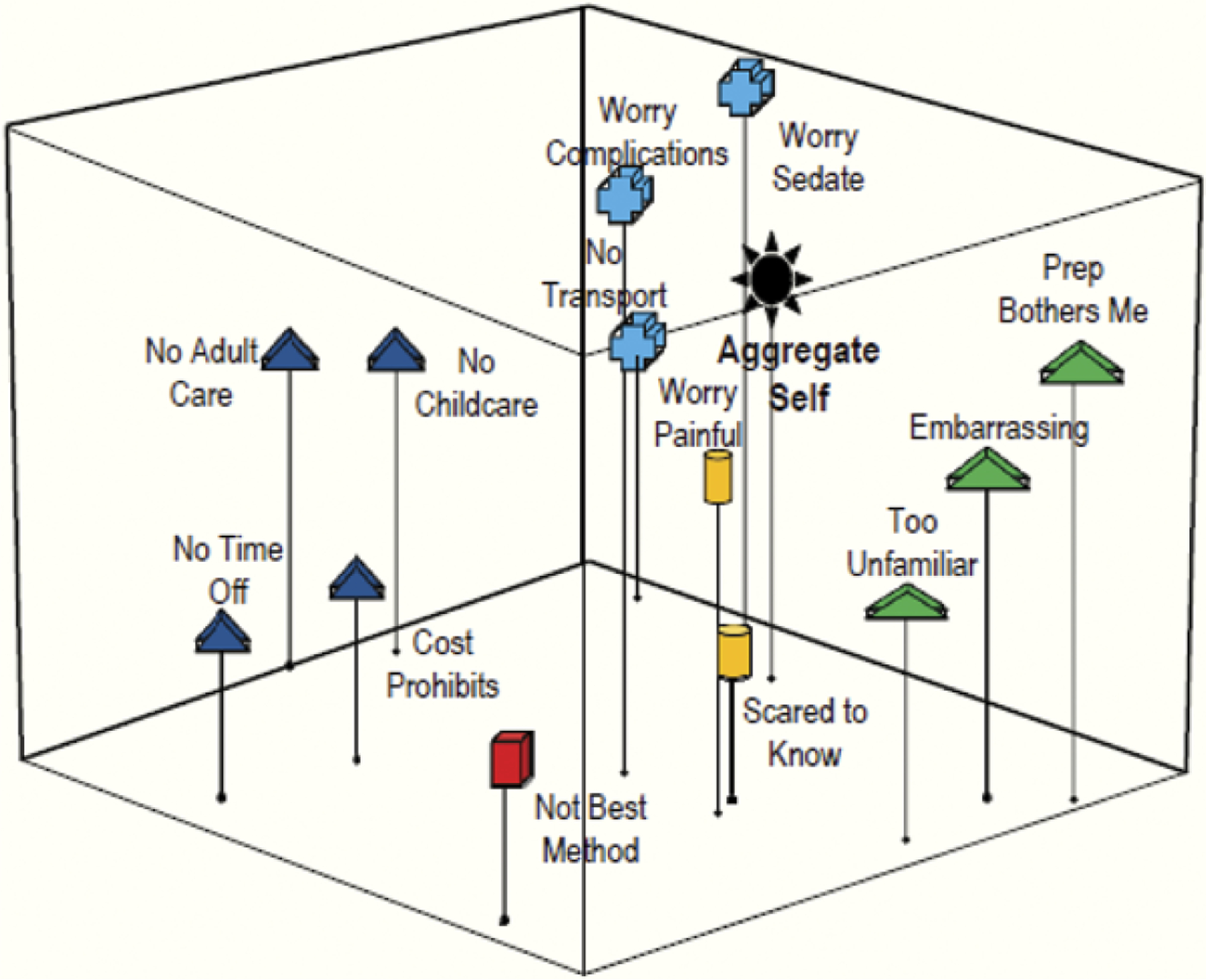

Figure 1.

Patients. Grouping 1: Barriers to colonoscopy.

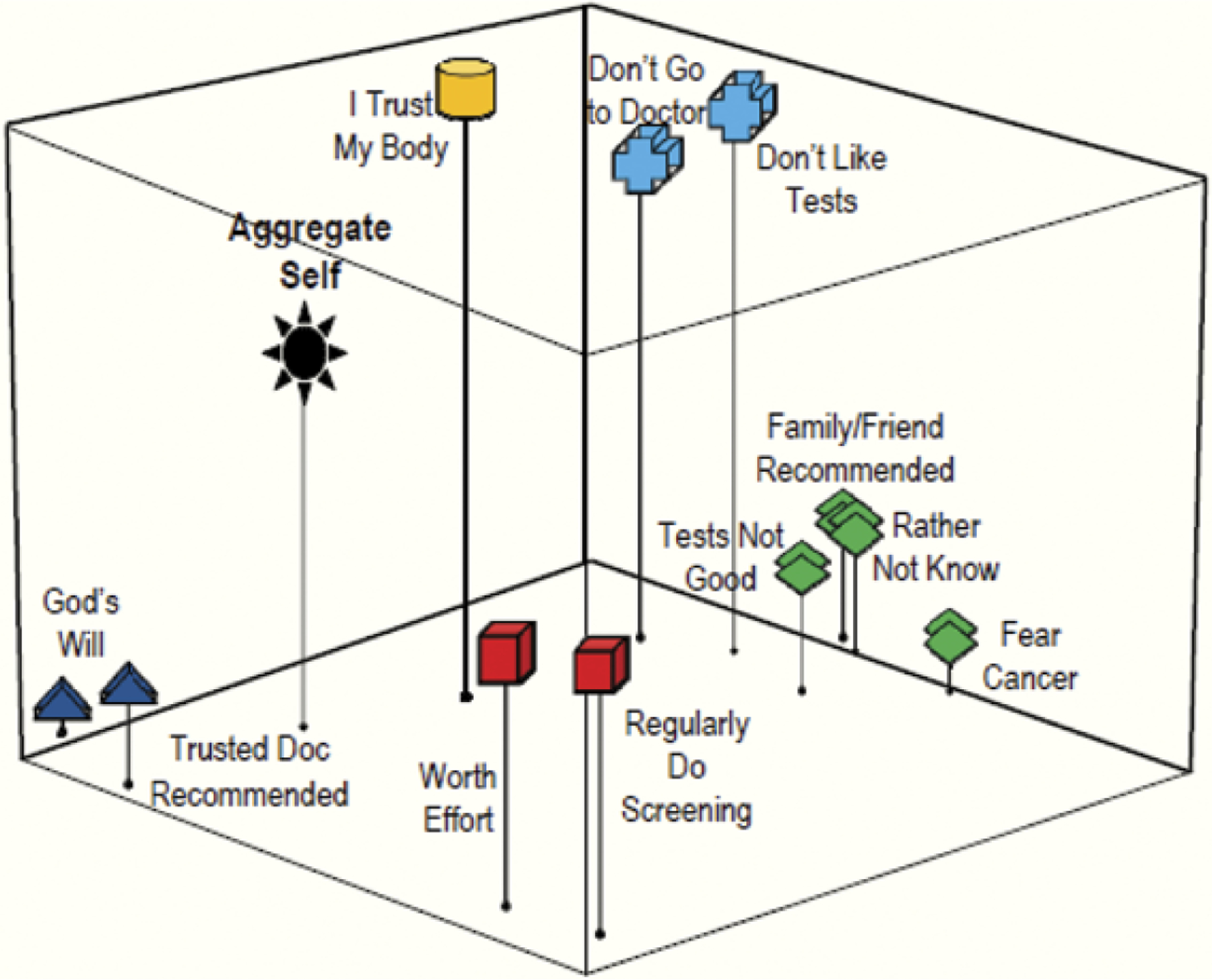

Figure 6.

Residents. Grouping 3: Preventive health practices/beliefs.

The mapping method uses paper-and-pencil instruments that require subjects to rate the extent to which they associate specific elements with each other (on the basis of similarities and differences or perceived association). For this study, patients and third-year residents answered a series of questions that asked them to rate the risks and benefits of having a colonoscopy screening using a scale of 0 to 10. Unlike other mental mapping procedures that require the respondent to make complex overall judgments, perceptual mapping only requires subjects to judge the individual component associations (e.g. risks, benefits); the software then puts these component parts together as a whole model, making the instrument easy for patients to use. Data can be collected from patients with limited literacy by having a researcher read the statements and ask the patient to rate how much they agree or disagree with each one, using a simple graphic display of agreement-disagreement.

To construct the perceptual maps, we used software based on a metric multidimensional scaling program called Galileo (Woelfel & Fink, 1980). This program converts the scaled judgments into distances used in the mapping. Input associations among the risks/benefits are derived from the interitem correlations of all elements, where the absolute values of the Pearson product-moment correlations are converted to a 0–10 scale base. Thus, all distance matrix input data are on the same 0–10 scale. Input values are also reflected so that more important elements appear closer to the aggregate self, whereas those judged less important are farther away (Bass et al., 2008).

In the last step, the software performs a metric multidimensional scaling analysis and produces graphic arrays of the distances among the elements. The graphic plots can be displayed in two or three dimensions for visual inspection and interpretation. The percentage of variance accounted for by the analysis is provided as an assessment of the explanatory value of each map (see Table 2). The resulting maps display the risk/benefit elements relative to each other and to the aggregate self. The maps ultimately provide a snapshot of the respondents’ conceptualization of the situation and reveal the relative importance of different elements (Bass et al., 2008) for each group (patients, physicians) that can be compared. Maps of the three groupings of issues patients and physicians associated with risks and benefits of colonoscopy screening studied are presented in Figures 1 through 6.

Table 2.

Percentage of variance explained by the perceptual maps

| Question grouping | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grouping 1: Barriers r2 | Grouping 2: Facilitators r2 | Grouping 3: Preventive health r2 | |

| Respondent | |||

| Patients | 58.41 | 78.55 | 68.95 |

| Physicians | 67.07 | 88.37 | 72.73 |

Instrumentation

The mapping survey instrument was developed based on research we conducted with physicians and patients (Bass et al., 2010; Ward et al., 2010). Resident physicians were asked a series of semi-structured interview questions about their perceptions of the facilitators and barriers to CRC screening for their African American patients (Ward et al., 2010). Focus groups of patients who used the clinic as their usual source of care were conducted to elicit patient perceptions of CRC risk and screening (Bass et al., 2010), some of which had been identified in previous research (Ward et al., 2010). The qualitative data obtained from the interviews and focus groups identified the concepts related to decision making and personal perceptions about colonoscopy, which we used to develop the perceptual mapping survey for physicians and patients.

The mapping survey was organized into three groupings of conceptually related questions (see Table 1): (a) 13 statements related to patient perceptions of the barriers to colonoscopy screening; (b) 8 statements related to the facilitators to colonoscopy screening; and (c) 11 statements about personal attitudes and preferences related to health maintenance, in general, and preventive screening, specifically. Patients were asked to rate how much they agreed or disagreed with each of the statements in the three groupings of the survey (perceived barriers, facilitators, and preventive health practices/beliefs) on a scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree); residents were asked to rate how they believed their patients would agree or disagree with each statement.

For patients, a research assistant read each survey question aloud and asked the patient to point to the graphic version of the scaled response that best fit his or her response. The points on the scale were presented using smiley faces ranging from 0 (strongly frowning) to 10 (strongly smiling). Similar graphic scales are widely used in clinical settings to assess pain, particularly in low literacy populations (Wong & Baker, 1988, 2001). For residents, the instrument was self-administered with instructions to answer how they believed their patients would answer the survey.

Sample and Data Collection

To survey African American patients, research assistants used scheduling records to determine eligibility and obtain a convenience sample of patients who consented to complete the mapping surveys. Patients who declined to participate cited schedule conflicts, were accompanied by a caretaker, or were not interested in focusing on anything other than their scheduled health visit. The survey was administered to 102 African American patients 50 to 82 years of age over an 8-week period in 2008.

The physician sample was comprised of third-year residents who were on a general internal medicine rotation in the same clinic. Third-year residents were chosen because it was assumed that by this point in their training they would have developed personal opinions and practices with patients yet still have time to alter their perceptions before leaving the program. Residency program faculty invited residents to complete an informed consent and perceptual mapping survey. Residents were asked to respond to the questions as they thought their patients would respond, allowing us to measure the physicians’ perceptions of their patients’ beliefs and perceptions about colonoscopy. Over the 8-week recruitment period, of the 31 third-year residents eligible to participate, 29 residents (94%) completed the survey.

Data Analysis

Survey data were entered into SPSS version 17.0 to generate interitem correlation coefficients, which were converted to a 0–10 scale for processing through the perceptual mapping software. This software produces maps that are models with n-dimensional rigid structures and a coordinate frame in the structures for referencing purposes. This allows the model to be interpreted with X-Y-Z coordinates so that any given point (concept) can be referenced in relation to the aggregate self. This process also produces eigen values for each dimension, providing a total variance explained value for each two- or three-dimensional model (Bass et al., 2008; see Table 2). The cumulative variance explains values for each of the perceptual maps, and ranged from 58.41% to 79.88% for the patients and 67.07% to 88.37% for the physicians. The greater variance explained in the physicians’ maps reflects the lower overall variability (standard deviation values) of physicians’ responses compared to those of patients across virtually all variables (see Table 1). The variance explained values for Grouping 1 (barriers) are lower than for Grouping 2 (facilitators) or Grouping 3 (preventive health) because Grouping 1 had more variables (13) compared with Grouping 2 (8) and Grouping 3 (11).

The resulting three-dimensional maps for each question grouping allow comparisons between patients’ perceptions (Figures 1, 3, and 5) and resident physicians’ perceptions (Figures 2, 4, and 6). These figures aggregate how the individuals in the sample thought about the concepts presented in the survey questions. By looking at the aggregate self position in relation to the concepts in the maps, we can see which concepts were or were not perceived as important by patients in deciding whether to have a colonoscopy. We can then compare these maps to those that represent the resident physicians’ perceptions of what their patients would identify as more or less important in deciding whether to have a colonoscopy.

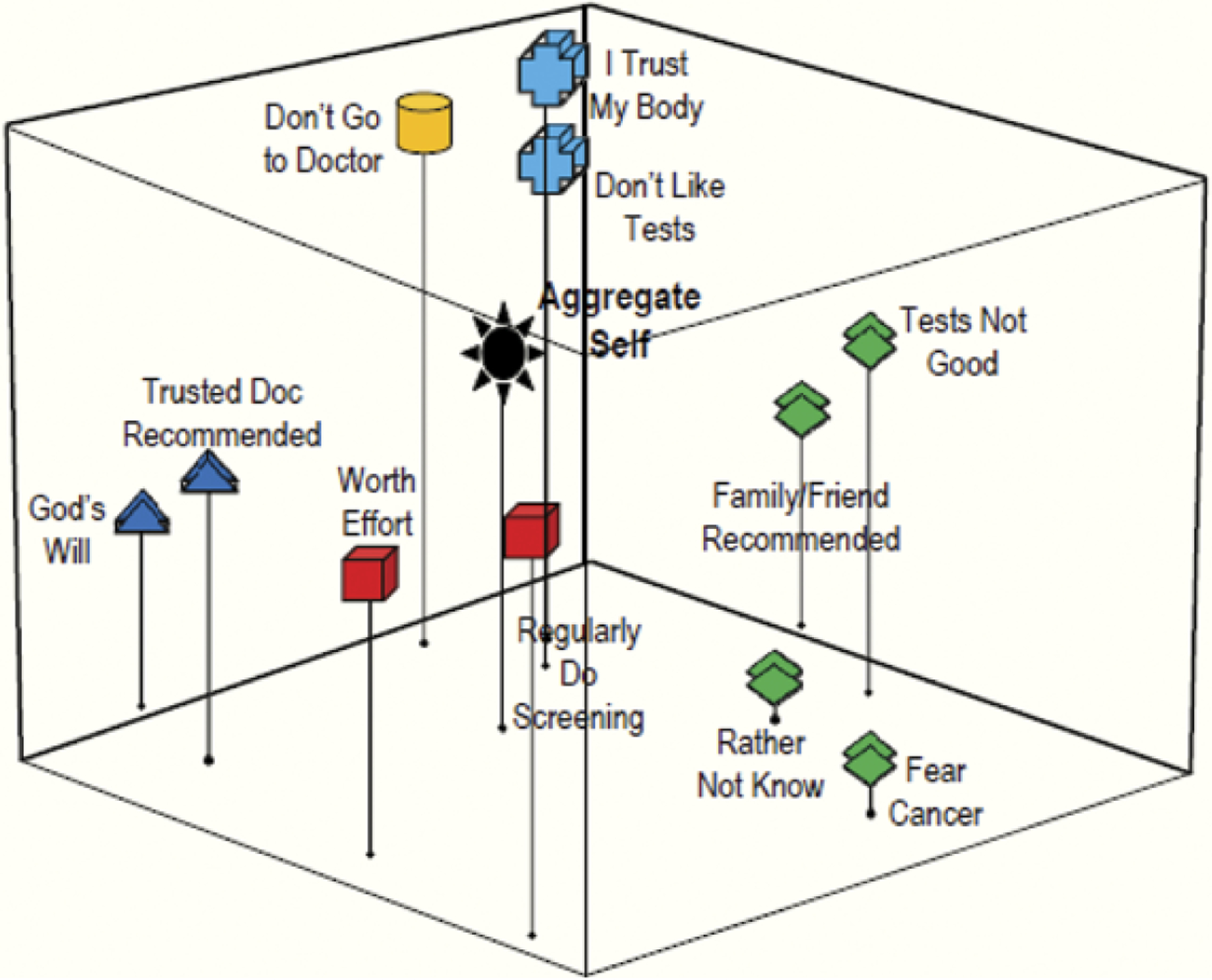

Figure 3.

Patients. Grouping 2: Facilitators to colonoscopy.

Figure 5.

Patients. Grouping 3: Preventive health practices/beliefs.

Figure 2.

Residents. Grouping 1: Barriers to colonoscopy.

Figure 4.

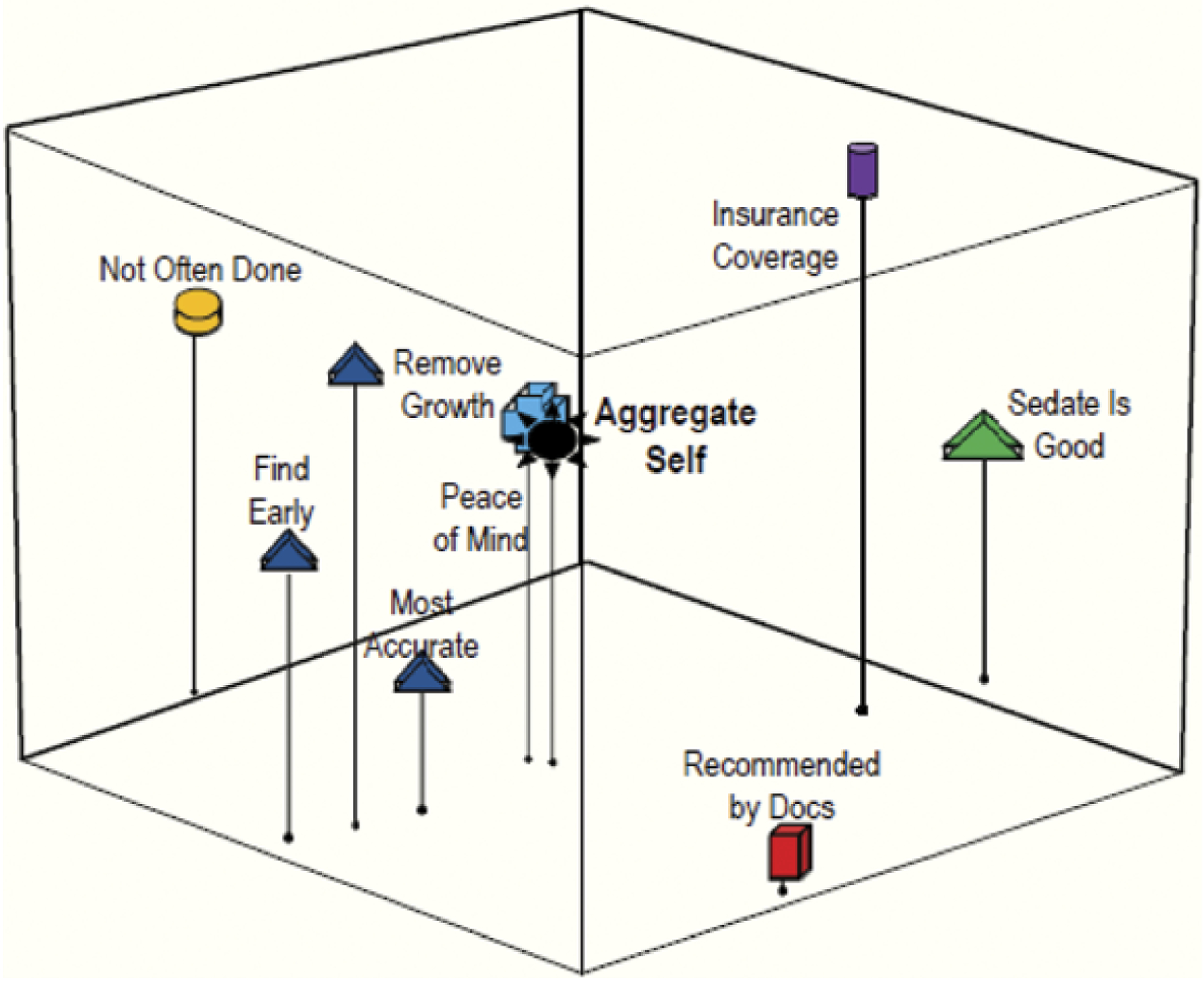

Residents. Grouping 2: Facilitators to colonoscopy.

SPSS was also used to generate descriptive statistics and independent sample t tests to compare the means between patient and physician responses (see Table 1). This allows us to compare how the patients and the physicians ranked the relative importance of each of the concepts in the groupings. Missing data were coded in SPSS and were excluded from analysis.

Results

Sample Demographics

Participants self-identified as 94.9% African American and 5.1% mixed race; 96% considered themselves to be non-Hispanic, 3% Hispanic, and 1% were unsure. Although 52% of the patients reported having graduated from high school or higher, 90% scored literacy levels below 6th grade on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine test (Davis et al., 1993). They were equal by gender, with a mean age of 69 years (range: 50 to 82 years). This subset of clinic patients was similar to the total population of patients who use the general internal medicine clinic. In the 12 months leading up to the study, general internal medicine clinic records indicated that patients were 64% female, 78% African American, and most were older than 50 years of age.

Resident physicians self-identified as 51.7% Caucasian, 24.1% Asian, 3.4% African American, and 20.7% other; 89.7% considered themselves to be Non-Hispanic, 6.9% Hispanic, and 3.4% did not answer. There were more men (55.2%) than women (41.4%); the mean age was 28 years (range: 27 to 33 years).

Perceptual Maps

Barriers to Colonoscopy

Figures 1 and 2 represent how the patients and third-year resident physicians conceptually grouped colonoscopy barriers. The subgroupings created by the patients’ (Figure 1) compared to the physicians’ (Figure 2) perceptions reveal that they interpret screening barriers differently. The patient map positions the variables of pain, fear and complication worries very close to the aggregate self, indicating that these concepts are important screening barriers for the patients (Figure 1). Although the physicians correctly identified the complications variable as important, they failed to recognize that fear of pain and a potential cancer diagnosis are important patient barriers. This discrepancy is indicated on the patient and physician maps by the greater distance between these concepts and the aggregate self (Figure 2).

The physician map also yielded subgroupings that indicate they view pragmatic barriers such as finding someone to care for family, cost of screening, as well as a belief that colonoscopy is not the best screening method, as being related issues of importance to patients, indicated by their perceived closeness to the aggregate self (Figure 2). Patients, however, viewed these lifestyle barriers as less important, indicated by their greater distance from the aggregate self (Figure 1).

Facilitators for Colonoscopy

Figures 3 and 4 represent perceptions about facilitators for colonoscopy. The close positioning of “test is good for early detection” to “doesn’t have to be done as often as other screenings” on both the patient (Figure 3) and physician maps (Figure 4) indicates that both groups perceived these two concepts as being closely related and perceived similarly. The patients also grouped these concepts closely to “doctor can remove growths before they become cancer” and “colonoscopy is the most accurate way to check [for CRC]” (Figure 3). The strong grouping of these factors shows that patients have a clear understanding of the benefits of colonoscopy. However, the absence of any grouping of these concepts in the physician map (Figure 4) indicates that the physicians underestimated their patients’ understanding and recognition of the advantages to colonoscopy.

Patients and physicians also differed in the importance they gave to peace of mind as a facilitator. The close positioning of this variable to the patient aggregate self shows that they viewed peace of mind as a critical motivator for having a colonoscopy. However, the physicians’ map shows this concept at a distance far from the aggregate self, indicating that they underestimated the importance of this concept to patients.

Preventive Health Practices/Beliefs

Concepts about preventive health practices and beliefs that might influence the decision to be screened are represented in Figures 5 and 6. Both the patients and the physicians identified “having a trusted physician recommendation” and “getting cancer is ‘God’s will’” as concepts that are related to one another; indicated by the similar grouping in both perceptual maps. However, the closer proximity of this grouping to the aggregate self in the patient map (Figure 5) reveals that they view these concepts as being more critical than other attitudes about health and screening, something their doctors did not fully perceive.

Another grouping that emerged in both maps (Figures 5 and 6) showed a grouping for the concepts of having colonoscopy only if a family member/friend recommended it, not wanting to know if cancer was present, not believing in screening tests, and fear of cancer. This grouping showed that both patients and physicians perceived that a person who fears cancer or doubts that screening tests are good might also be likely to avoid tests unless a loved one prompted action. However, the grouping’s relative distance from the aggregate self in the patient map also indicates that, although patients viewed these concepts as having a strong relationship, they were not representative of how they see themselves. Similarly, none of these concepts in the physician map were close to the aggregate self, suggesting that the doctors were unsure which of the concepts might influence their patients’ screening behaviors more.

Independent Sample t Test

Independent sample t tests were conducted to assess how statistically important concepts were for patients and residents, and to rank the perceived relative importance of certain barriers and facilitators for colonoscopy and preventive health practices/beliefs (Table 1).

For statements related to barriers (Grouping 1), patients ranked: (a) “concerned about pain” (p < .001); (b) “worried about complications” (p = .005); (c) “fear of cancer” (p < .001); (d) “preparing for the test is too much bother” (p < .001) as being most important to their colonoscopy screening decision. Physicians identified (a) “preparing for the test is too much bother” (p < .001); (b) “concerned about pain” (p < .001); (c) “test is so unfamiliar, I don’t want to do it” (p < .001); (d) “finding someone to care for my children or grandchildren” (p < .001) as significant, indicating that they perceived other barriers to be more important for their patients.

For statements related to facilitators (Grouping 2), patients identified (a) peace of mind (p < .001); (b) “sedation is a plus” (p < .001); (c) “recommended by doctors” (p < .001); (d) “colonoscopy is the most accurate test” (p < .0001). Physicians did not, however, perceive these as important facilitators, instead identifying (a) “sedation is a plus” (p < .001); (b) “good way to find CRC early” (p < .001); (c) “doctor can remove growths before they become cancer” (p < .001); and (d) “should have it if my health insurance covers cost” (p < .001) as significant.

For statements related to preventive health practices/beliefs (Grouping 3), patients’ perceptions about screening tests were again very different from what physicians thought that their patients’ perceptions were. Specifically, patients agreed most strongly with (a) “to avoid getting sick, I try to do screening tests” (p < .001); (b) “[I would] only have a colonoscopy if a doctor I trusted told me to” (p < .001); (c) “having a colonoscopy is well worth the effort” (p < .001); and (d) “if I get cancer, I accept that it is the will of God” (p < .001). In contrast, physicians reported that their patients do not, generally, want to be screened. Specifically, they perceived that patients would agree most strongly with the following: (a) “don’t get tests unless something is wrong” (p < .001); (b) “[I would] only have a colonoscopy if a doctor I trusted told me to” (p < .001); (c) “my body will let me know when I need testing” (p = .857); and (d) “don’t go to the doctor unless I need to” (p = .005). Thus, their only similar perception was that patients would agree that having a doctor they trusted tell them to have a test is a motivator for screening; physicians entirely missed that patients would have more intrinsic reasons to do so (i.e., to avoid getting sick, because it is worth the effort).

Discussion

The perceptual maps and the independent sample t tests revealed that physicians and their patients had different perceptions regarding the barriers and facilitators for having a colonoscopy or preventive health screenings in general. Three comparisons are central for understanding this discrepancy: (a) the physicians’ perceptual maps (Figures 2, 4, and 6) had few concepts with a close proximity to the aggregate self, indicating a general lack of perceived importance for patients of any particular concept; (b) the physicians’ maps had fewer concept groupings, indicating that physicians were often unsure about which issues patients viewed as related; and (c) the physicians’ mean scores for the survey questions (Table 1) tended to be centered around the middle of the 0 to 10 scale, suggesting their lack of clarity or assuredness about what concepts would be salient to their patients. In contrast, patients were more definitive, rating many concepts highly which, when modeled, appeared close to the aggregate self (indicating importance) and included clear conceptual groupings (indicating relation to one another). Patients’ mean scores for the survey questions (Table 1) were also frequently low or high on the 0 to 10 scale, indicating they strongly agreed or disagreed, displaying a far more definitive set of perceptions about barriers and facilitators to colonoscopy.

Physicians thus struggled to recognize the importance of numerous barriers to colonoscopy for their own patients, as well as those identified as important for African Americans by previous research. Specifically, fear and limited knowledge about screening options and the risks and benefits of screening are widely reported barriers that physicians in this study underestimated in importance. Overall, the barriers patients scored as important were consistent with those reported in previous research, with fear of pain and fear of a cancer diagnosis as the most significant barriers to screening (Green & Kelly, 2004; James et al., 2002).

Similarly, patient concerns about embarrassment were identified as conceptually related to bothersome preparation and lack of familiarity with the screening test. Embarrassment has been reported in the literature as a significant barrier for African American patients (Greiner et al., 2005; James et al., 2002), yet the physicians in our sample did not recognize it as a barrier. Although lifestyle and logistical concerns about the preparation and time required for screenings have been reported as barriers for African Americans (McAlearney et al., 2008; Palmer, Midgette, & Dankwa, 2008) and were reported as likely barriers by residents in this study, patients surveyed identified those issues as being less important than pain, sedation, or a possible cancer diagnosis. Thus, while residents appeared to be somewhat familiar with commonly reported lifestyle and logistical barriers, they did not adjust these general barriers for the perceptions of their particular patient population.

Perceptual discrepancies were also evident regarding facilitators to screening. Residents tended to rate survey questions as neutral, resulting in a perceptual map (Figure 4) that illustrated little belief in their patients’ understanding of the benefits of screening. The lack of any conceptual grouping, combined with the far distance from the aggregate self of all concepts on their map, shows that the physicians were less confident about their knowledge of patient facilitators to colonoscopy compared to barriers. In contrast, the clear grouping and close proximity of the peace-of-mind concept in the patient map (Figure 3) reveals that the patients appeared to have a clear understanding of the benefits of colonoscopy. Specifically, patients’ recognition of the test’s accuracy and potential to lead to removal of growths early were what gave them the peace of mind that they might associate with knowing that they are cancer-free.

Physician–patient communication may also be impeded by discordant perceptions about personal attitudes toward preventive health practices/beliefs among African Americans, particularly those that may facilitate screening. For example, if physicians do not recognize patients’ perceptions about the importance of screening to prevent disease and their understanding that colonoscopy is the most accurate test, they may inhibit and complicate physician-patient communication about colonoscopy. Similarly, since few physicians reported mistrust as a barrier, despite it being reported by their patients as well as reported previously in the literature (Peterson et al., 2008), they may miss addressing trust and mistrust either directly, in relation to a specific test, or more globally, in their doctoring role (Peterson et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2003). Residents in our sample also did not identify the extent to which fatalistic beliefs are held by African Americans, particularly the belief that cancer is not curable and patients lack control over early detection, commonly reported as a barrier to screening for African American patients (Greiner et al., 2005; McAlearney et al., 2008; Powe, 1994).

Physicians may also miss opportunities to facilitate screening if they overlook many African Americans’ desire to take care of their body as God’s holy temple, or to build on their faith in God’s will (James et al., 2002; Palmer et al., 2008). Physician-patient communication that builds on these core beliefs in religiously oriented patients could motivate a patient to seek screening tests by reinforcing that colonoscopy is worth the effort. Integrating patient perceptions more fully into communication strategies is particularly important because previous research has shown that for African American patients, a physician’s recommendation to be screened is an important facilitator to CRC screening (Palmer et al., 2008; Peterson et al., 2008).

Limitations

Our findings are limited by the characteristics of the resident physician sample. Although constituting 94% of eligible residents and approximately one third of all residents in the teaching program, the total number was small (n = 29). In addition, since residents were recruited during their general internal medicine rotation, some had more gastroenterology training than others and thus may have had greater knowledge of and enthusiasm for colonoscopy. The residents who had no particular interest in gastroenterology might have been less motivated to answer the survey thoughtfully or to have paid particular attention to patients’ screening perceptions and preferences.

Another limitation is that all patients had either Medicaid or Medicare insurance, which covers colonoscopy. This could have influenced the absence of the cost of screening as an important barrier which previous studies have identified as obstacles for urban African American patients (Peterson et al., 2008; Taylor et al., 2003). While patients did not report financial concerns as important, physicians saw them as barriers to screening. Third-year residents may not, at this point in their training, be aware of the differences in coverage of colonoscopy that may exist among different insurance carriers, thus affecting their survey answers.

In addition, this study did not match individual patients and physicians; participants were asked to speak about patients’ perceptions, in general. However, it is possible that some physicians could have responded to survey questions with specific patients’ lifestyles and preferences in mind. This might have skewed their responses regarding patients’ barriers and facilitators for colonoscopy screening. For example, clinic patients with time, mobility and/or health constraints were potentially less likely to participate. These same constraints might prevent those patients from obtaining a colonoscopy. Thus, it is possible that the residents might have had those patients, among others, in mind when identifying lifestyle and logistical issues as being important barriers to colonoscopy screening.

Our findings cannot be generalized to third-year residents in other settings or with different patient populations. Other residency programs may or may not consider colonoscopy as the standard of care. Similarly, these findings may not be representative of perceptions of all African Americans with Medicare or Medicaid access to colonoscopy in urban settings. Uninsured African American patients or those without a usual source of care may have different experiences and perceptions related to colonoscopy than those reported in this study.

Conclusions

This comparative analysis of perceptual maps indicates that third-year resident physicians may not accurately perceive what their African American patients view as the most important barriers and facilitators to colonoscopy and preventive health screenings. The methods used for this study allowed us to gain a better understanding of residents’ perceptions, on the basis of their residency education and clinical experiences. Specifically, physicians in our sample underestimated the extent to which their patients understood the benefits of screening, the importance of doctors’ recommendations, and the role that religious beliefs play in screening decisions. Residents also underestimated the importance of certain screening barriers for their patients (e.g., fear of complications, pain, sedation, and fear of finding cancer), and underestimated patients’ acceptance that if they get cancer, it is God’s will.

If resident physicians had more accurate perceptions of these facilitators and barriers, they might more effectively counsel African American patients by building on facilitators and addressing barriers. Because patients reported that having a doctor recommend a test was an important facilitator, as reported in other studies (Palmer et al., 2008; Peterson et al., 2008), making a specific recommendation to have a colonoscopy may be more effective than giving patients the choice of several different screening methods.

Resident physicians have a unique role in encouraging patients to accept colonoscopy as a valuable preventive tool and are likely to do so most effectively when they understand their patients’ perceptions about this and other preventive health practices. Residency training programs can encourage this by placing high value on understanding and communicating effectively with patients to influence health behavior. Because African Americans are at particular risk for CRC, residency programs attempting to increase colonoscopy screening rates in this population may do so by increasing the accuracy of residents’ awareness of their patients’ perceptions.

Acknowledgments

There were no conflicts of interest for this research. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (grant number 1R21CA120122).

Contributor Information

DOMINIQUE G. RUGGIERI, Department of Health Services, Saint Joseph’s University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

SARAH BAUERLE BASS, Department of Public Health, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

MICHAEL J. ROVITO, Department of Health Professions, University of Central Florida, Orlando, Florida, USA

STEPHANIE WARD, Bravo Health Advanced Care Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

THOMAS F. GORDON, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, Massachusetts, USA

ANURADHA PARANJAPE, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

KAREN LIN, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

BRIAN MEYER, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

LILITHA PARAMESWARAN, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

CAITLIN WOLAK, Department of Public Health, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

JOHNSON BRITTO, Department of Public Health, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

SHERYL B. RUZEK, Department of Public Health, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

References

- American Cancer Society. (2010a). Colorectal cancer facts & figures 2008–2010. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/F861708_finalforweb.pdf

- American Cancer Society. (2010b, March 1). Overview: Colon and rectum cancer—How many people get colorectal cancer? Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_2_1X_How_Many_People_Get_Colorectal_Cancer.asp?rnav=cri

- Barrison AF, Smith C, Oviedo J, Heeren T, & Schroy PC III (2003). Colorectal cancer screening and familial risk: A survey of internal medicine residents’ knowledge and practice patterns. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 98, 1410–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass SB, Gordon TF, Burt Ruzek S, Wolak C, Ward S, Paranjape A, … Ruggieri DG (2011). Perceptions of colorectal cancer screening in urban African American clinic patients: Differences by gender and screening status. Journal of Cancer Education, 26(1), 121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass SB, Gordon TF, Ruzek SB, & Hausman AJ (2008). Mapping perceptions related to acceptance of smallpox vaccination by hospital emergency room personnel. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science, 6, 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeker C, Kraft JM, Southwell BG, & Jorgensen CM (2000). Colorectal cancer screening in older men and women: Qualitative research findings and implications for intervention. Journal of Community Health, 25, 263–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers T, Levin B, Rothenberger D, Dodd GD, & Smith RA (1991). American cancer society guidelines for screening and surveillance for early detection of colorectal polyps and cancer. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 47, 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns CP, & Viswanath K (2006). Communication and colorectal cancer screening among the uninsured: Data from the Health Information National Trends Survey (United States). Cancer Causes and Control, 17, 1115–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcaise-Edinboro P, & Bradley CJ (2008). Influence of patient-provider communication on colorectal cancer screening. Medical Care, 46, 738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Davis TC, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, … Crouch MA (1993). Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Family Medicine, 25, 391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulai GS, Farmer MM, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, Qi K, Dietrich AJ, …. Khan KA (2004). Primary care provider perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in a managed care setting. Cancer, 100, 1843–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller BM, Skelly JM, Dorwaldt AL, Howe KD, Dana GS, & Flynn BS (2008). Increasing Patient/Physician Communications About Colorectal Cancer Screening in Rural Primary Care Practices. Medical Care, 46(9 Suppl 1), S36–S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennarelli M, Jandorf L, Cromwell C, Valdimarsdottir H, Redd W, & Itzkowitz S (2005). Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: Inadequate knowledge by physicians. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, 72(1), 36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin SS, Ashford AR, Lantigua R, Hajiani F, Franco R, & Heck JE, & Gemson D (2007). Intraurban influences on physician colorectal cancer screening practices. Journal of the National Medical Association, 99, 1371–1380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PM, & Kelly BA (2004). Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions, and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nursing, 27, 206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner KA, Born W, Nollen N, & Ahluwalia JS (2005). Knowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra CE, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Brown JS, Halbert CH, & Shea JA (2007). Barriers of and facilitators to physician recommendation of colorectal cancer screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22, 1681–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes-Rovner M, Williams GA, Hoppough S, Quillan L, Butler R, & Given CW (2002). Colorectal cancer screening barriers in persons with low income. Cancer Practice, 10, 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner M, Ries L, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Howlader N, …. Edwards BK (2010, January 28). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Retrieved from http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006 [Google Scholar]

- James AS, Campbell MK, & Hudson MA (2002). Perceived barriers and benefits to colon cancer screening among African Americans in North Carolina: How does perception relate to screening behavior? Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 11, 529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen CM, Gelb CA, Merritt TL, & Seeff LC (2001). CDC’s Screen for Life: A national colorectal cancer action campaign. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 10, 417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz ML, James AS, Pignone MP, Hudson MA, Jackson E, & Oates V, & Campbell MK (2004). Colorectal cancer screening among African American church members: A qualitative and quantitative study of patient-provider communication. BMC Public Health, 4, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khankari K, Eder M, Osbarn CY, Makoul G, Clayman M, & Skripkauskas S, … Wolf MS (2007). Improving colorectal cancer screening among the medically underserved: A pilot study within a federally qualified health center. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22, 1410–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlearney AS, Reeves KW, Dickinson SL, Kelly KM, Tatum C, & Katz ML, … Parker ED (2008). Racial differences in colorectal cancer screening practices and knowledge within a low-income population. Cancer, 112, 391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul KD, & Tulloch HE (1999). Cancer screening decisions. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 91(18), 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxentenko AS, Goel NK, Pardi DS, Vierkant RA, Petersen WO, & Kolars JC, … Limburg PJ (2007). Colorectal cancer screening education, prioritization, and self-perceived preparedness among primary care residents: Data from a national survey. Journal of Cancer Education, 22, 208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RC, Midgette LA, & Dankwa I (2008). Colorectal cancer screening and African Americans: Findings from a qualitative study. Cancer Control, 15(1), 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson NB, Murff HJ, Fowke JH, Cui Y, Hargreaves M, Signorello LB, & Blot WJ (2008). Use of colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy among African Americans and Whites in a low-income population [Letter]. Preventing Chronic Disease, 5(1), 1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, Berg AO, & Lohr KN (2002). Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: A summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine, 137, 132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powe BD (1994). Perceptions of cancer fatalism among African Americans: The influence of education, income and cancer knowledge. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association, 7(2), 41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroy PC 3rd, Geller AC, Crosier Wood M, Page M, Sutherland L, Holm LJ, & Heeren T (2001). Utilization of colorectal cancer screening tests: A 1997 survey of Massachusetts internists. Preventive Medicine, 33, 381–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma VK, Corder FA, Raufman JP, Sharma P, Fennerty MB, & Howden CW (2000). Survey of internal medicine residents’ use of the fecal occult blood test and their understanding of colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 95, 2068–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor V, Lessler D, Mertens K, Tu S-P, Hart A, Chan N, … Thompson B (2003). Colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: The importance of physician recommendation. Journal of the National Medical Association, 95, 806–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2002). The guide to clinical preventive services: Report of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (3rd ed.). McLean, VA: International Medical Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ward SH, Parameswaran L, Bass SB, Paranjape A, Gordon TF, & Ruzek SB (2010). Resident physicians’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to colorectal cancer screening for African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association, 102, 303–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woelfel J, & Fink E (1980). The measurement of communication processes: Galileo theory and method. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong DL, & Baker CM (1988). Pain in children: Comparison of assessment scales. Pediatric Nursing, 14, 9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DL, & Baker CM (2001). Smiling face as anchor for pain intensity scales. Pain, 89, 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zack DL, DiBaise JK, Quigley EM, & Roy HK (2001). Colorectal cancer screening compliance by medicine residents: Perceived and actual. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 96, 3004–3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]