Abstract

Background:

African Americans experience disproportionately higher morbidity and mortality from colorectal cancer (CRC), yet they complete screening at lower rates than Caucasians. While studies have identified barriers and facilitators to CRC screening among African Americans, no study has examined physician perceptions of these barriers.

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to determine how resident physicians view barriers and facilitators to CRC screening among their African American patients, and to compare residents’ perceptions with barriers and facilitators that have been reported in studies with African Americans.

Design:

Both quantitative and qualitative data were obtained during in-depth interviews with 30 upper-year residents from an urban academic internal medicine program.

Results:

Residents recognized the low levels of awareness of CRC that have been reported among African American patients. The most common barriers reported by residents were lack of knowledge, fears, personal/social circumstances, and colonoscopy-specific concerns. Residents reported a need for increased education, increased public awareness, and easier scheduling as facilitators for screening. Residents failed to appreciate some key perceptions held by African Americans that have been documented to either impede or facilitate CRC screening completion, particularly the positive beliefs that could be used to overcome some of the perceived barriers.

Conclusions:

Residents may be missing opportunities to more effectively communicate about CRC screening with their African American patients. Residents need more explicit education about African Americans’ perceptions to successfully promote screening behaviors in this high-risk population.

Keywords: colon, cancer, screening, African Americans, residency

BACKGROUND

African Americans are disproportionately affected by colorectal cancer (CRC), experiencing significantly higher incidence of and mortality from CRC than whites.1 When detected early, CRC is a highly treatable disease, with survival rates at 5 years as high as 90%.2 However, despite their increased risk, African Americans complete CRC screening, particularly with endoscopic methods, at lower rates than their white counterparts.3–7 In fact, a multivariate analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey concluded African Americans are approximately 18% less likely than whites to be screened after controlling for age, sex, education, and income level.3 A critical step in working to address this health disparity and increase CRC screening rates among African Americans is to effectively address existing barriers to screening while understanding the factors that facilitate screening. Prior studies have identified several barriers to screening among African Americans, including fear, mistrust of the health care system, fatalism, lack of awareness/knowledge, access, and cost.7–16 To date, few studies have assessed resident physicians’ understanding of the barriers and facilitators to CRC screening among the African American patients for whom they care and refer for screening.

Residency programs in internal medicine often represent the final phase of formal training for physicians planning careers in primary care. It is generally accepted that the knowledge and practice patterns acquired by physicians during residency will be brought with them into their clinical practices and may persist for some time. Thus, residency is the optimal time to ensure that physicians possess accurate knowledge about the barriers and facilitators to CRC screening for this high-risk population in order to ultimately improve screening rates. Moreover, prior studies have demonstrated residents’ rates of CRC screening for African American patients can be improved with educational efforts.17,18

The purpose of this study was to interview residents using both open-ended and fixed-choice questions to determine how they view awareness of CRC screening, and facilitators and barriers to screening among their African American patients, and to compare their perceptions with barriers and facilitators that have been reported in previous research with African American patients.

METHODS

Study Setting and Participants

We conducted 30 semistructured interviews using fixed-choice and open-ended questions with second- and third-year internal medicine residents over 7 months in 2006 at an urban academic medical center. For ease of scheduling, residents on rotations that did not require overnight call were invited to participate by e-mail or by direct contact with a study investigator. No incentive was provided for study participation. The Temple University institutional review board approved the study protocol and methods for maintaining anonymity.

Data Collection

All interviews were conducted in administrative offices by the principal investigator or 1 of 2 coinvestigators who hold teaching appointments within the residency program. Prior to the interview, each participant signed an informed consent and consent to audiotape. Each interview lasted 30–40 minutes and was audiotaped.

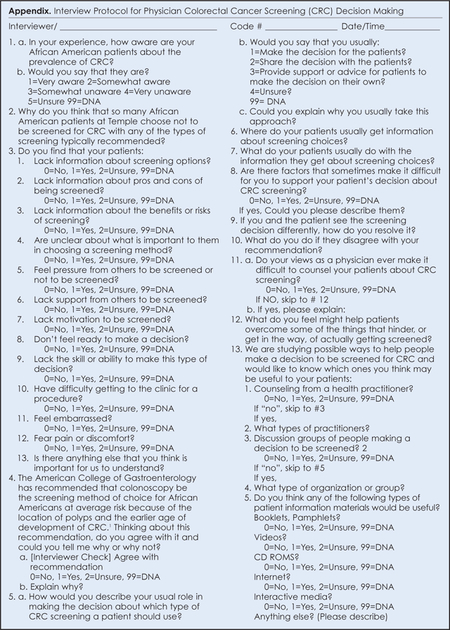

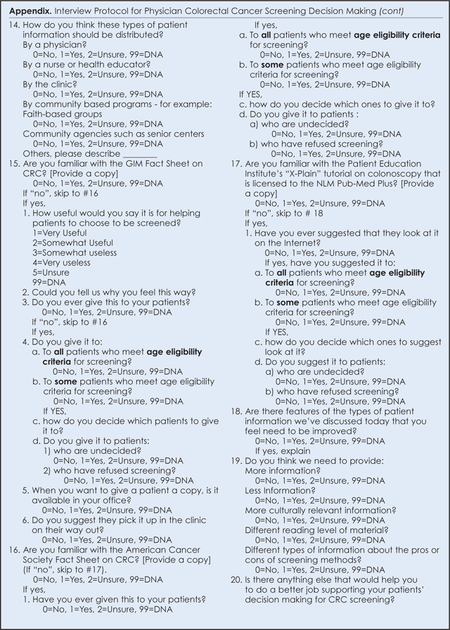

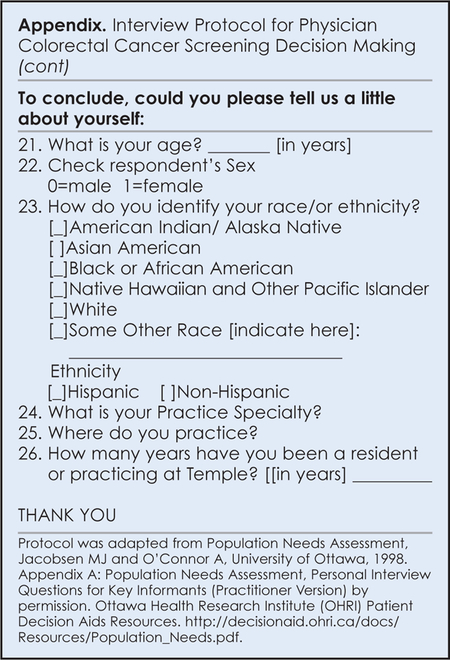

An interview guide, “Population Needs Assessment, Personal Interview Questions for Key Informants (Practitioner Version),” was adapted with permission from the Ottawa Health Research Institute (OHRI) (Appendix).19 Using open-ended questions we explored 3 broad topic areas: awareness of colorectal cancer and increased risk among African Americans, barriers to completing CRC screening, and facilitators of CRC screening. Fixed-choice questions were used after each open response to permit systematic data collection as well. For example, residents were asked, “In your experience, how aware are your African American patients about the prevalence of CRC?,” followed by “Would you say that they are: (1) very aware; (2) somewhat aware; (3) somewhat unaware; (4) very unaware; or (5) unsure.” These questions were part of a larger study designed to understand physicians’ roles in decision making about CRC screening.

All fixed-choice responses were analyzed using SPSS to generate descriptive statistics. Using standard qualitative methods, analysis of the open-ended questions was an iterative process. The principal investigator and a research assistant initially coded interview transcripts for broad themes. All codes were independently reviewed by the 2 physician interviewers and a third physician who had not interviewed participants. All investigators discussed the final codes and systematically checked completeness and accuracy. Coding conferences were held until agreement was reached on the codes used for all interview data. When there were disagreements between coders, the interview data were discussed until consensus was reached; in some instances, this required revising the codes themselves.

RESULTS

Resident Characteristics

Of the 43 residents eligible to participate, 95.4% agreed to participate; 2 (4.7%) did not respond to the invitation to participate. Thirty residents (69.8%) completed interviews; 11 (25.6%) were unable to schedule time to do so. The mean age of the participants was 29 years (range, 27–52). Approximately half of the residents were male (53%) and female (47%). Residents’ self-reported race was predominately Caucasian (47%), but also included 30% Asian, 13% African American, and 10% other.

Residents’ Perceptions of Patient Awareness of Colorectal Cancer

As shown in Table 1, when asked an open-ended question about their perceptions of their patients’ level of awareness of the prevalence of CRC, residents gave examples of the limited knowledge of the higher risk of CRC among African Americans. Residents also reported that African American patients were far less aware of CRC compared to other cancers, particularly lung, cervical, prostate, and breast cancer. In a fixed-choice follow-up question, most residents (76.6%) reported that their patients were very or somewhat unaware. Twenty percent reported somewhat aware. One resident believed that African Americans were very aware, but only if a family member had a history of CRC.

Table 1.

Physician Perceptions of African Americans’ Awareness of Colorectal Cancer (N = 30)

| Level of Awareness | Reported Level of Awareness % (N) | Descriptions of Awareness |

|---|---|---|

| Very aware | 3.3% (1) | “Some are aware of family members or friends who have had it.” |

| Somewhat aware | 20% (6) | “Moderately aware. They know it [CRC] exists, but I don’t think they know what screening modalities are out there.” |

| Somewhat unaware | 43.3% (13) | “Not very aware. Cancers that get more attention are breast and lung. There is not much attention in African Americans.” |

| Very unaware | 33.3% (10) | “In general, our patient population is not aware of the potential risk.” “I think they are quite unaware.” “They don’t understand it’s a major problem.” “Practically not at all aware.” |

Residents’ Perceptions of Patient Barriers to Colorectal Screening

When presented with fixed-response options to characterize their African American patients’ barriers to CRC screening, resident responses centered on availability of information, fear of being tested, and lack of patient readiness to make a screening decision. More than 90% of residents reported lack of information as an important barrier. Specifically, residents perceived an information deficit related to screening options, including knowledge about the benefits and risks of screening. Further, 87% of residents thought that fear of pain or discomfort was a barrier, with 83% reporting that their patients were not ready to make a decision about screening. Embarrassment, lack of motivation, and difficulty getting to the clinic for the procedure were cited as barriers by 60% of the residents interviewed. Least often reported were lack of support for screening (43%), feeling pressure from others (23%), and inability to make a decision (20%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of Resident-Reported Barriers to Colorectal Screening for African Americans

| Lack information about screening options | 96.7% |

| Lack information about pros and cons of being screened | 90% |

| Lack information about the benefits or risks of screening | 93% |

| Fear pain or discomfort | 86.7% |

| Don’t feel ready to make a decision | 83% |

| Unclear about what is important while choosing a screening method | 63% |

| Lack motivation to be screened | 60% |

| Feel embarrassed | 60% |

| Have difficulty getting to the clinic for a procedure | 60% |

| Lack support from others to be screened | 43% |

| Feel pressure from others to be screened or not to be screened | 23% |

| Lack the skill or ability to make this type of decision | 20% |

In reviewing participant responses to our open-ended question regarding their African American patients’ reluctance to get screened, several similar themes emerged (Table 3). These included: (1) lack of knowledge, (2) fear, (3) procedural concerns about colonoscopy, (4) personal and social circumstances, and (5) distrust of the medical establishment.

Table 3.

Barriers to Colorectal Screening Residents Perceived Among African Americans

| Lack of awareness and knowledge | Lack of awareness of need for screening “It’s part of a belief system and how it is used. You only come when you’re sick.” “I don’t think they understand that it is a good screening tool. They don’t understand the benefit of finding the cancer early.” “They don’t recognize the need for preventative care because they feel well.” |

| Lack of knowledge of colorectal cancer risk “A lot of people don’t understand the disease the way an average health care practitioner does—don’t understand how preventable it is or how much at risk they are for developing colorectal cancer.” |

|

| Fears | Fear of outcomes “I think the biggest reasons are that they’re scared to find out” [if they have cancer]. “Fear of finding something that they would’ve preferred to pretend they didn’t have.” “Fear of the unknown. The thinking is ‘I’m fine. Why go looking for something that may alter my life?’“ |

| Fear of colonoscopy procedure “More fear of the procedure than fear of the diagnosis.” “I think mostly they are afraid of the prep. They are afraid of the invasive procedure. They are worried it is going to be painful.” |

|

| Colonoscopy procedure | Psychological-emotional “I guess that a lot of them just seem uncomfortable with the idea of someone ‘going there’ whether it’s a flex sig or colonoscopy. I think they’re just uncomfortable with the idea of someone doing that to them.” “There is a lot of stigma attached to having the anal area examined.” “We always say we’re going through the rectum looking with a camera. I think there’s a sexual connotation for some.” “People get caught up on how a colonoscopy is performed - an invasive procedure.” |

| Time and complexity of colonoscopy “Logistics are a big deterrent - first day is the prep, second day is the procedure…” “I think the process is a little bit more complicated than simply getting a mammogram. They need to do the bowel prep, they need to make another appointment with another doctor, they need a referral.” |

|

| Personal/social circumstances | “Often they have personal circumstances, social circumstances that make it hard. They often don’t see it as a priority….no substitute for any duties that they have (child care, elder care, etc).” “They come here to the hospital with serious illnesses. They don’t come here to be screened.” |

| Distrust related to experimentation | “I think there’s a distrust of medicine. They’ve gotten the impression that we’re here to experiment on them.” |

Lack of knowledge and awareness.

Lack of knowledge and awareness about CRC risk and screening options was widely reported among residents as significant barriers to CRC screening among African Americas patients. Specifically, residents thought patients lacked understanding of the importance of preventive screening in general and of screening for CRC in particular.

Fear.

Patient fears were the most frequently cited CRC screening barriers by residents; residents’ descriptions of these fears included fear of the screening outcome (ie, finding cancer), and fear of pain or discomfort during a screening procedure.

Colonoscopy procedure.

Residents reported procedural concerns such as the time required, the preparation needed, and the invasiveness of the colonoscopy as barriers to CRC screening. In addition, the complexities of scheduling, obtaining referrals, and completing the procedure were also cited as barriers.

Personal and social circumstances.

Personal and social circumstances that were reported as barriers to CRC screening reflected the residents’ awareness that many patients have other obligations and/or higher priority medical needs than being screened.

Distrust related to experimentation.

A few residents reported distrust of the medical establishment as a potential impediment to screening for African Americans, particularly the concern that physicians might be experimenting on them.

Residents’ Perceptions of Patient Facilitators to Colorectal screening

In response to the fixed-choice questions about facilitators to screening, 93% of residents reported that counseling and a recommendation from a health care provider were key facilitators leading African Americans to complete CRC screening. More than 90% also recognized the use of informational booklets, pamphlets, and videos as potential facilitators to screening.

Three themes emerged from the responses to the open-ended question about CRC screening facilitators: (1) the need for more knowledge and education, (2) increased public awareness, and (3) easier scheduling/logistics. These are outlined below with examples described in Table 4.

Table 4.

Resident-Reported Facilitators to Colorectal Screening Among African Americans

| Increased knowledge/education | “Knowing more. Once you explain, it helps. Not knowing is a big barrier.” “Discussing it more—what it really means to have colon cancer and how this screens early and what it means to be treated early rather than having it be undetected and the consequences of that.” “They need to understand the importance of preventative health and screening.” “It would be very helpful if we could do more education.” “We need to correct misconceptions and concerns.” |

| Increased public awareness | “More public awareness, knowing what to expect…The more people talk about it, the more it gets done.” “Education would be most important; not just for patients but also the community at large.” |

| Easier scheduling/logistics | “Making the process of actually getting there and getting an appointment, getting their bowel prep as easy as possible.” “Open access takes away the step of having to be evaluated by the GI doctor and then coming back again.” |

Knowledge and education.

Residents thought that increasing patient education about the elevated risk of CRC among African Americans, the potential for improved survival through early detection, the details of colonoscopy, and available screening options would help to increase CRC screening rates.

Increased public awareness.

Many residents felt that public awareness of CRC remains very low, especially when compared to other types of cancers and serious diseases. They discussed the importance of raising awareness at a community level as a way to increase screening rates.

Easier scheduling/logistics.

Several residents felt that systematic logistical changes, such as open-access colonoscopy scheduling; assistance with transportation; and relief from other daily obligations, including work or dependent care responsibilities, would help their patients adhere to CRC screening recommendations.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined how resident physicians caring for African American patients perceive the factors related to levels of awareness of CRC, and related to barriers to and facilitators of screening. The vast majority of residents in our study perceived that their African American patients were unaware of the prevalence of CRC or their risk of developing it. Indeed, research has shown that African Americans consistently underestimate their risk of colorectal cancer3–5,10 and also believe that there is nothing they can do to prevent it.6,7

This study also found that residents recognized an array of barriers to CRC screening that are consistent with those that have been identified in previous research studying African American patients. Specifically, the negative impact of fear and limited knowledge on screening rates are widely reported.7–10,13–15 African American patients’ lack of knowledge about screening options and the risks and benefits of screening, and the belief that screening should only be done if symptoms are present have previously been reported by Taylor et al.10 Fears of pain or discomfort as well as the fear of being diagnosed with cancer appear in recent studies of African Americans.13,15 Finally, logistical concerns, including the inconvenience of the bowel prep and time required for colonoscopy, have been previously documented as barriers to completion of CRC screening.7, 9

Residents also identified facilitators to screening that are consistent with those reported in prior studies, particularly the importance of a physician recommendation for CRC screening to African American patients.9, 14 Residents also reported a need for programs to increase both patient and public awareness of the risk of CRC and the importance of early detection and screening. While interventions aimed at increasing the rate of CRC screening among African Americans that have targeted entire communities have not produced significant increases in screening rates, such interventions have been successful in increasing both intent to be screened and positive beliefs about CRC screening in general.20,21 The effect of raising overall awareness on CRC perceptions and screening rates among African Americans remains to be seen.22 However, in this study, residents suggested that raising overall awareness might make counseling patients easier.

Importantly, we also found that residents less commonly recognized several significant barriers to CRC screening that have been previously established in studies of African Americans. While the concern about embarrassment has been widely reported in the literature,7,8 relatively few residents in this study reported it as a significant barrier, even when specifically asked about it. Similarly, concerns about patient ability to access care and the cost of screening were rarely reported by residents as barriers, despite existing studies that have identified copayments and the need for referrals as potential obstacles for African Americans in urban settings.10,14 In fact, Peterson et al found that the most commonly cited reason for not completing CRC screening after lack of a physician recommendation was cost.14

In general, resident physicians also failed to recognize key perceptions held by African Americans which, if not addressed, could hinder completion of recommended CRC screening. For example, while multiple studies have identified mistrust as a barrier to screening among African American patients,10,14 only a minority of residents reported lack of trust of the health care system as a significant barrier. Residents also did not identify fatalistic beliefs held by African Americans. Fatalism, such as the belief that CRC is not curable and that people have no control over detecting cancer early, has been repeatedly reported as a barrier to screening among African American patients.7,8,12

In addition, residents did not recognize that African Americans’ may hold beliefs that actually facilitate screening. Personal beliefs that have been reported to facilitate screening among African Americans include a desire to set a good example for family members, following a religious belief of taking care of one’s body because it is God’s holy temple, and worrying less.9,15 Greiner and colleagues posited that positive perceptions such as hope and accuracy of screening could be used to tailor educational interventions to overcome the perceived barriers to screening.8 Residents who remain unaware of the positive beliefs held by African Americans may be missing opportunities to more effectively communicate about screening with their patients.

A few strengths of this study worth noting include the use of a combination of fixed-choice survey questions and open-ended interview questions in a focused study of upper-year residents completing their training in an urban, underserved area. At the time of this study, colonoscopy had become the widely accepted standard of care and was reimbursed by Medicare and Medicaid as well as many private insurers. In this environment, residents clearly viewed colonoscopy as the screening method of choice for patients without severe comorbidities that would contraindicate the procedure. Unlike other studies, we asked about how residents though CRC screening rates could be improved for African Americans. Residents emphasized the need to raise awareness at the community level, as well as provide more relevant individual patient education in clinical settings. Several saw the need for more media attention to CRC, comparable to that given to other types of cancers on radio and TV, and through mobile units in communities.

The findings of this study are limited by the small number of resident physicians interviewed, although the sample represents approximately one-third of the total number of physicians in training at the participating institution. Another limitation may stem from the fact that 2 of the study physicians who conducted interviews hold teaching appointments in the residency program and this might have limited the openness of resident responses and discussions. However, the third interviewer was not affiliated with the residency program, and responses obtained during these interviews did not differ in any meaningful way. As a large portion of this study was qualitative, results presented have predictably limited generalizability. Our findings cannot be extended to residents training in other settings or with different patient populations, such as rural or community-based training programs, or residency programs in which colonoscopy is not so uniformly regarded as the standard of care.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, we found that resident physicians’ perceptions about awareness of CRC among African American patients and perceptions of barriers and facilitators to adherence with CRC screening are consistent with patient perceptions reported in prior research. However, several very important barriers were not widely recognized by residents, and residents failed to identify beliefs held by African Americans which may facilitate screening. By underestimating the potential impact of these barriers and not drawing upon patients’ positive beliefs about health and screening, physicians may be missing opportunities to communicate more effectively with their African American patients. A tailored educational intervention designed to increase resident awareness of patients’ beliefs may help to improve their ability to effectively counsel patients and subsequently encourage the completion of recommended CRC screening by African American patients. Resident physicians need more explicit education about perceptions held by African Americans in order to improve the care they deliver not only during their residency but also as they enter primary care medical practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully thank Karen Lin, MD, MPH, and Brian Meyer, MD, MPH, for their assistance with data collection and analysis. We would also like to thank Dr Lawrence Kaplan, section chief, General Internal Medicine, at Temple University School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for his support of this research.

Funding/Support:

This work was supported in part by Temple University through a research leave to Dr Ruzek from the College of Health Professions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrawal S, Bhupinderjit A, Bhutani MS, et al. Colorectal cancer in African Americans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:515–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006. Accessed April 20, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, et al. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2003;97:1528–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Data. Atlanta, GA: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004. http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/race.asp?yr=2008&state=UB&qkey=4425&grp=0. Accessed April 27, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.James TM, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, et al. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening: a guideline-based analysis of adherence. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:228–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards RJ, Reker DM. Racial differences in use of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and barium enema in Medicare Beneficiaries. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2715–2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McAlearney AS, Reeves KW, Dickinson SL, et al. Racial differences in colorectal cancer screening practices and knowledge within a low-income population. Cancer. 2008;112(2):391–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greiner KA, Born W, Nollen N, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of colorectal cancer screening among urban African Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer RC, Midgette LA, Dankwa I. Colorectal cancer screening and African Americans: findings from a qualitative study. Cancer Control. 2008;15(1):72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor V, Lessler D, Mertens K, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: the importance of physician recommendation. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:806–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vernon SW. Risk perception and risk communication for cancer screening behaviors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;25:101–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powe BD. Perceptions of cancer fatalism among African Americans: the influence of education, income and cancer knowledge. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 1994;7(2):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green PM, Kelly BA. Colorectal cancer knowledge, perceptions and behaviors in African Americans. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27:206–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson NB, Murff HJ, Fowke JH, et al. Use of colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy among African Americans and Whites in a low-income population [letter]. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1). http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/jan/07_0160.htm. Accessed January 18, 2008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James AS, Campbell JK, Hudson MA. Perceived barriers and benefits to colon cancer screening among African Americans in North Carolina: how does perception relate to screening behavior? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:529–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipkus IM, Rimer BK, Lyna PR, et al. Colorectal screening patterns and perceptions of risk among African American users of a community health center. J Community Health. 1996;21(6):409–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borum ML. Medical residents’ colorectal cancer screening may be dependent on ambulatory care education. Digest Dis Sci. 1997;42(6):1176–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman M, Borum ML. Colorectal cancer screening of African Americans by internal medicine residents physicians can be improved with focused educational efforts. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(9):1010–1012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsen MJ and O’Connor A. Personal Interview Questions for Key Informants (Practitioner Version). In: Population Needs Assessment. University of Ottawa: 1999 [updated 2006]. Ottawa Health Research Institute (OHRI) Patient Decision Aids Resources. http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/implement/Population_Needs.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blumenthal DS, Fort JG, Ahmed NU, et al. Impact of a two-city community cancer prevention intervention on African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:1479–1488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz ML, Tatum C, Dickinson, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers: results of the Carolinas Cancer Education and Screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007;110(7):1602–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward SH, Lin K, Meyer B, et al. Increasing colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: Linking risk perception to interventions targeting patients, communities and clinicians. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(6):748–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]