Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer plays significant role in morbidity, mortality and economic cost in Africa.

Objective

To investigate the burden and trends of incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) of colorectal cancer in Africa from 2010 to 2019.

Methods

This study was conducted according to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019 analytic and modeling strategies. The recent GBD 2019 study provided the most updated and compressive epidemiological evidence of cancer incidence, mortality, years lived with disability (YLDs), years of life lost (YLLs), and DALYs.

Results

In 2019, there were 58,000 (95% UI: 52,000–65,000), 49,000 (95% UI: 43,000–54,000), and 1.3 million (95% UI: 1.14–1.46) incident cases, deaths and DALYs counts of colorectal cancer respectively in Africa. Between 2010 and 2019, incidence cases, death, and DALY counts of CRC were significantly increased by 48% (95% UI: 34–62%), 41% (95% UI: 28–55%), and 41% (95% UI: 27–56%) respectively. Change of age-standardised rates of incidence, death and DALYs were increased by 11% (95% UI: 1–21%), 6% (95% UI: − 3 to 16%), and 6% (95% UI: − 5 to 16%) respectively from 2010 to 2019. There were marked variations of burden of colorectal cancer at national level from 2010 to 2019 in Africa.

Conclusion

Increased age-standardised death rate and DALYs of colorectal cancer indicates low progress in CRC standard care-diagnosis and treatment, primary prevention of modifiable risk factors and implementation of secondary prevention modality. This serious effect would be due to poor cancer infrastructure and policy, low workforce capacity, cancer center for diagnosis and treatment, low finical security and low of universal health coverage in Africa.

Keywords: Colorectal, Cancer, Africa, Burden

Background

Colorectal cancer plays significant role in morbidity, mortality and economic cost. In 2019, Global Burden Disease study reported that CRC accounted for 1.8 million incidence cases, 0.9 million deaths, and 19 million DALYs worldwide [1]. According to GLOBACAN reported in 2020, colorectal cancer was responsible for more than 1.9 million new incident cases and 0.94 million deaths, making third and second rank for overall cancer incidence and mortality globally [2]. Global incidence cases of CRC doubled or more than doubled in 157 of 204 countries, and mortality due to CRC doubled of more doubled in 129 of 204 countries, pronounced increases were observed in low and Middle SDI countries from 1990 to 2019 [3]. Due to the rapid rising of global population size, aging and human economic development, burden of CRC is predicted to be 2.2 million new cases and 1.1 million cancer deaths by 2030 [4] and 3.2 million new incidence cases in 2040 [5]. This trend alarms all concern bodies to stand for prevention and control of CRC. CRC is the indicator of socioeconomic transition, epidemiological and demographic change. The current global evidence ascertains that trend of CRC has three patterns-rapidly rising in many LMICs which is associated with socioeconomic transition, stabilizing or decreasing in middle high and high income countries [1, 2, 4]. Development of CRC has associated with males and older age. Lifetime risk of CRC estimated approximately 4.4% of men (1 in 23) and 4.1% of women (1 in 25) [6]. Approximately 70% of CRC cases occur sporadic, whereas the remaining 12–35% and 5–7% are linked with familiar and genetic respectively [7, 8]. More than half (55%) of all CRCs have attributed to lifestyle factors, including an unhealthy diet, insufficient physical activity, high alcohol consumption, and smoking [6]. Global efforts have tried to alleviate serious effect of cancer, specifically major cancers such as CRC, breast, and cervical cancer. In 2012, World Health Assembly members agreed to reduce premature death from noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) by 25% by 2025 [9]. In 2015, United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals planned to reduce NCD related premature mortality by one-third by 2030 [10]. Understanding the trend and variation in incidence, DALYs and mortality of colorectal cancer helps for public health experts, Professional experts, national policy makers and cancer prevention advocacy groups to bring evidence based decision in their countries and to evaluate the effectives, accessibility, affordability, and efficiency of interventions. GLOBACAN and GBD are the two studies that provide national, regional and global burden of cancers. Despite this evidence, burden of CRC in Africa and nations are not well narrated due to their compressive report. Therefore, considering the aforementioned issues, the present study provides regional and national incidence, mortality and DALYs for colorectal cancer in terms of counts, age-standardised rates, and percentage change for 54 countries from 2010 to 2019.

Methods

The data used for analysis of this study was obtained from GBD2019 data tools (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool). The study conducted based on GBD2019 methodology framework and tools. The GBD study provides a standardised approach for estimating incidence, prevalence, and DALYs by cause, age, sex, year, and location for global, regions and countries. The incidence, DALYs and mortality for CRC reported as part of the Global Burden of Disease, injury, and risk factors study 2019. The GBD 2019 estimates provided evidences for 363 causes of non-fatal burden, 302 causes of deaths, and 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 21 regions and 7 supper regions. The main sources of data used for GBD estimation were obtained from cancer registry, vital registration, sample registration system, and verbal autopsy [11]. There are three main standardised tools: Cause of Death Ensemble model (CODEm), spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression (ST-GPR), and DisMod-MI [11]. Cause of Death Ensemble model (CODEm) developed after stepwise data transformation of raw data. First, incidence and mortality data obtain from different sources are transformed into standardised format, categorize and registered. After standardised, cancer registry incidence data and cancer registry mortality data are mapped to GBD causes and standardized to the GBD age groups. Incidence and mortality data from cancer registries were processed before matching the same by cancer, age, sex, year, and location to generate crude mortality-to- incidence (MI) ratio. Finally, MI ratios estimates were estimated using a linear step mixed- effects model using the logit link function, in which healthcare access and quality (HAQ) index served as a covariate. The ST-GPR model has three main hyperparameters that control for smoothing across time, age, and geography. The final mortality estimates were produced using the Cause of Death Ensemble Model (CodeM) using crude mortality estimates as inputs along with other variables taken as covariates. DALYs of CRC was estimated using DisMod-MR 2.1 proportion model. The input of data for DisMod-MR 2.1 was procedure-related disability (ostomies) for all locations by age, sex, and year. Evidence from literature review narrated that an average of 58% of all ostomies are for colorectal cancer, so we multiplied the all-cause ostomies by 0·58 [12].

Result

Colorectal burden of Africa

In 2019, estimated incident new cases of colorectal cancer in Africa were 58,000 (95% UI: 52,000–65,000), with age-standardised 8.7 (95% UI: 8.–9.4) per 100,000 in both sexes. The incidence cases increased significantly from 40,000 (95% UI: 36,000–43,000) in 2010 to 58,000 (95% UI: 52,000–65,000) in 2019, which represented a percentage change of 48% (95% UI: 34–62%) and AAPC 4.4% (95% UI: 4.3–4.5%). Change of age –standardised incidence rate of CRC between 2010 and 2019 was 11% (95% UI: 1–21%) and AAPC was 1.1% (95% UI: 1–1.2%).

In 2019, estimated absolute number of deaths due to colorectal cancer in Africa was 49,000 (95% UI: 43,000–54,000), with age-standardised 8.1 (95% UI: 7.4–8.8) per 100,000. Between 2010 and 2019, deaths due to colorectal cancer increased from 35,000 (95% UI: 31,000–38,000) to 49,000 (95% UI: 43,000–54,000), which represented 41% (95% UI: 28–55%) and AAPC was 3.9% (95% UI: 3.8–4%). Change of age-standardised death rate of CRC between 2010 and 2019 was 6% (95% UI: − 3 to 16%) and AAPC was 0.7% (95% UI: 0.4–1%).

In 2019, estimated DALYs counts of colorectal cancer in Africa were 1.3 milion (95% UI: 1.14–1.46), with age-standardised 180 (95% UI: 160–200) per 100,000. The DALYs counts of colorectal increased significantly from 0.92 million (95% UI: 0.84–1.01) in 2010 to 1.3 million (95% UI: 1.1–1.6 in 2019, which represented 41% (95% UI: 27–56%) and AAPC was 3.7% (95% UI: 3.6–3.8%). Change of age-standardised DALYs rate of CRC between 2010 and 2019 was 6% (95% UI: − 5 to 16%) and AAPC was 0.6% (95% UI: 0.5–0.7%). For comparing purpose, we explored the trends of CRC in Europe, America, Asia and Global (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparing change of burden of colorectal cancer from 2010 to 2019

| Regions | Incidence cases | Death counts | DALYs counts | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | DALYs (%) | 95% UI (%) | ||||

| Global | 32 | 24 | 41 | 27 | 20 | 33 | 23 | 16 | 30 |

| Africa | 48 | 34 | 62 | 41 | 28 | 55 | 41 | 27 | 56 |

| America | 28 | 15 | 41 | 26 | 22 | 31 | 24 | 20 | 29 |

| Asia | 46 | 32 | 62 | 37 | 25 | 49 | 31 | 19 | 43 |

| Europe | 13 | 2 | 24 | 10 | 5 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

| Regions | ASIR | ASDR | Age standardised DALYs rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (%) | 95UI% (%) | Value (%) | 95UI% (%) | Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | ||||

| Global | 2 | − 4 | 9 | − 3 | − 8 | 2 | − 3 | − 8 | 3 |

| Africa | 11 | 1 | 21 | 6 | − 3 | 16 | 6 | − 5 | 16 |

| America | 0 | − 9 | 11 | − 1 | − 5 | 2 | − 1 | − 5 | 3 |

| Asia | 9 | − 1 | 20 | 0 | − 8 | 9 | 1 | − 8 | 10 |

| Europe | − 1 | − 10 | 9 | − 6 | − 10 | − 2 | − 7 | − 11 | − 2 |

Distribution of Burden of CRC among sexes in Africa

In 2019, CRC accounted for 31, 00 (95% UI: 27,000–36,000), 2500 (95% UI: 22,000–29,000), and 6.9 million (95% UI: 6–7.9) incidence cases, deaths and DALYs counts among males in Africa respectively. In Africa, CRC accounted for 27, 00 (95% UI: 24,000–30,000), 2300 (21,000–26,000), and 6.1 million (95% UI: 5.2–7) incidence cases, deaths and DALYs counts respectively among females in 2019. In 2019, age-standardised rates of incidence cases, deaths, and DALYs of CRC were 10.6 (95% UI: 9.4–11.9), 9.2 (95% UI: 8.2–10.3), and 210 (95% UI: 180–230) per 100,000 in African males respectively, and 8.7 (95% UI: 7.7–9.7), 8 (95% UI: 7.1–9), and 170 (95% UI: 150–200) per 100,000 in African females respectively. In Africa, between 2010 and 2019, percentage change of incidence cases, death and DALYs counts of CRC were 48% (95% UI: 31–65%), 40% (95% UI: 23–56%), and 40% (95% UI: 23–57%) in males, respectively, and 47% (95% UI: 31–64%), 42% (95% UI: 27–58%), and 42% (95% UI: 26–60%) in females, respectively. From 2010 to 2019 in Africa, changes of age-standardised rate of incidence, death and DALYs were 12% (95% UI: 0–25%), 7% (95% UI: − 5 to 19%), and 6% (95% UI: − 6 to 18%) respectively in males, and 10% (95% UI: − 1 to 21%), 6% (95% UI: − 4 to 17%), and 6% (95% UI: − 6 to 18%) respectively in females. From 2010 to 2019 in Africa, the average annual percentage change (AAPC) of incidence cases was 4.4% (95% UI: 4.3–4.5) in males and 4.4% (95% UI: 4.3–4.5) in females while AAPC of age-standardised DALYs was 1.3% (95% UI: 1.1–1.4%) in males and 1% (95% UI: 0.9–1.1%) in females.

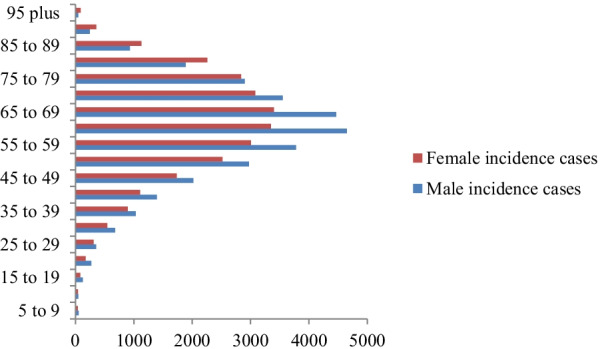

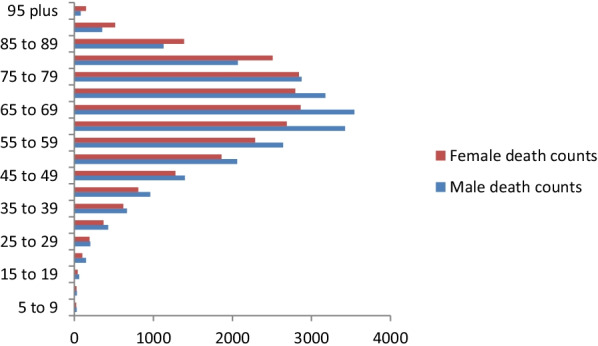

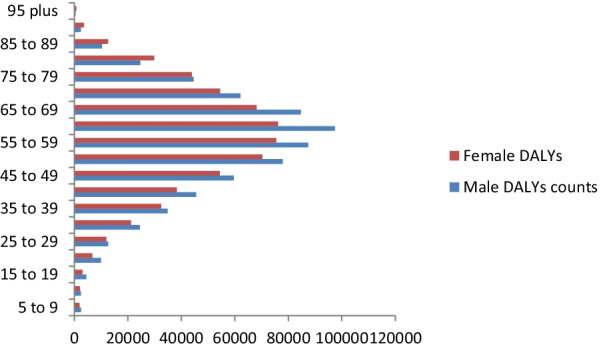

Age specific distribution of burden of CRC in Africa

In 2019, age specific incidence CRC was peaking at 60–69 years in both males and females. Age specific death counts were peaking at 60–69 years while 65–79 years in females. Most DALYs counts were recorded in 55–64 years in both male and female (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

Fig. 1.

Age specific incidence cases of colorectal cancer among sexes in Africa, 2019

Fig. 2.

Age specific death counts of colorectal cancer in among sexes in Africa, 2019

Fig. 3.

Age specific DALYs counts of colorectal cancer among sexes in Africa, 2019

National burden

There were marked variations of burden of colorectal cancer at national level from 2010 to 2019 in Africa. In 2019, highest estimated new incident cases of colorectal cancer observed in Nigeria 7080 (5310–8960), Egypt 6520 (4680–9010), South Africa 5570 (5000–6290), Algeria 3410 (2670–4280), Morocco 3210 (2390–4070), and Ethiopia 3200 (2400–4460) while lowest new incident cases observed in Sao Tome and Principe 16 (11–22), Seychelles 38 (34–44), Comoros 40 (30–60), and Gambia 50 (50–90). In 2019, highest age-standardised new incidence rate of colorectal recorded in Seychelles 35.7 (31.4–40.6), Mauritius 19.8 (16.1–24.2), Botswana 18.8 (13.5–24.5), and Libya 17 (12.4–21.8) per 100,000 while lowest age-standardised rate saw in Central African Republic 6.3 (4.6–8.7), Malawi 6.3 (4.9–7.8), Niger 5.6 (4.2–7.6), and Somalia 5 (3.1–9.2) per 100,000 (Table 2). From 2010 to 2019, highest percentage change of incidence cases of CRC have seen in Djibouti 77% (40–125), Cabo Verde 77% (39–112%), Rwanda 72% (42–109%), Angola 68% (36–114%), and Democratic Republic of the Congo 63% (29–104%) while lowest changes observed Eswatini 20% (− 7 to 61%), Guinea 19% (− 2 to 19%) and Central African Republic 16% (− 8 to 45%). From 2010 to 2019, highest increased age-standardised incidence rate of CRC has seen in Cabo Verde 48% (15–78), Morocco 25% (1–54%), Sao Tome and Principe 22% (2–42%), Sudan 22% (0–48), Ethiopia 21 (− 1 to 42%), whereas decreased age-standardised incidence rate of CRC has seen Somalia—1% (− 19 to 19), Eswatini—2% (− 22 to 28%), South Africa—5% (− 15 to 8%), Central African Republic—8% (− 25 to 13%), Libya—8% (− 33 to 19%) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Incidences case, Deaths, and DALYs of colorectal cancer in 2019

| Location | Incidence case counts | Age-standardised incidence rate | Death counts | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 95% UI | 2019 | 95% UI | 2019 | 95% UI | ||||

| Africa | 58,000 | 52,000 | 65,000 | 8.7 | 8 | 9.4 | 49,000 | 43,000 | 54,000 |

| Algeria | 3410 | 2670 | 4280 | 10.5 | 8.3 | 13 | 2380 | 1890 | 2950 |

| Angola | 1080 | 830 | 1390 | 10 | 8.1 | 12.5 | 950 | 740 | 1210 |

| Benin | 360 | 280 | 470 | 7.8 | 6.3 | 9.8 | 330 | 260 | 420 |

| Botswana | 250 | 170 | 330 | 18.8 | 13.5 | 24.5 | 190 | 130 | 250 |

| Burkina Faso | 640 | 500 | 820 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 9.4 | 580 | 460 | 740 |

| Burundi | 330 | 240 | 480 | 7.3 | 5.3 | 10.4 | 300 | 220 | 440 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 950 | 720 | 1200 | 9.6 | 7.6 | 11.9 | 850 | 660 | 1070 |

| Cabo Verde | 60 | 50 | 70 | 13.4 | 10.7 | 15.7 | 50 | 40 | 60 |

| Cameroon | 1270 | 930 | 1680 | 11.2 | 8.6 | 14.6 | 1110 | 840 | 1460 |

| Central African Republic | 140 | 100 | 190 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 8.7 | 130 | 90 | 180 |

| Chad | 390 | 300 | 510 | 7.3 | 5.7 | 9.4 | 370 | 290 | 480 |

| Comoros | 40 | 30 | 60 | 9 | 6.6 | 11.4 | 40 | 30 | 50 |

| Congo | 300 | 220 | 400 | 11.9 | 9.1 | 15.4 | 270 | 200 | 350 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2190 | 1480 | 3260 | 6.4 | 4.2 | 9.6 | 2000 | 1340 | 2960 |

| Djibouti | 70 | 50 | 100 | 11.9 | 9.1 | 15.8 | 60 | 40 | 80 |

| Egypt | 6520 | 4680 | 9010 | 9.8 | 7.1 | 13.4 | 4560 | 3300 | 6270 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 70 | 50 | 110 | 15.6 | 9.8 | 22.4 | 60 | 40 | 90 |

| Eritrea | 280 | 210 | 370 | 10.3 | 8.1 | 13.2 | 250 | 190 | 320 |

| Eswatini | 80 | 50 | 110 | 14.4 | 9.8 | 19.7 | 70 | 50 | 100 |

| Ethiopia | 3200 | 2400 | 4460 | 7.7 | 5.8 | 10.7 | 2850 | 2130 | 4000 |

| Gabon | 170 | 120 | 210 | 16.4 | 12.1 | 20.3 | 140 | 100 | 180 |

| Gambia | 60 | 50 | 90 | 6.8 | 5 | 9.2 | 60 | 40 | 80 |

| Ghana | 1490 | 1160 | 1900 | 9.5 | 7.6 | 11.9 | 1270 | 1000 | 1610 |

| Guinea | 390 | 300 | 510 | 7.3 | 5.6 | 9.4 | 370 | 280 | 480 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 70 | 50 | 80 | 9.3 | 7.1 | 11.7 | 60 | 40 | 70 |

| Kenya | 1780 | 1420 | 2210 | 8.2 | 6.7 | 10 | 1630 | 1280 | 2040 |

| Lesotho | 150 | 100 | 190 | 12 | 8.8 | 15.5 | 130 | 100 | 170 |

| Liberia | 130 | 90 | 190 | 6.8 | 4.7 | 9.7 | 120 | 80 | 170 |

| Libya | 900 | 660 | 1180 | 17 | 12.4 | 21.8 | 620 | 450 | 800 |

| Madagascar | 800 | 580 | 1080 | 7.3 | 5.4 | 9.7 | 710 | 530 | 960 |

| Malawi | 440 | 340 | 560 | 6.3 | 4.9 | 7.8 | 400 | 310 | 510 |

| Mali | 680 | 530 | 850 | 8.1 | 6.4 | 10.1 | 610 | 490 | 770 |

| Mauritania | 170 | 130 | 220 | 8.8 | 6.8 | 11.1 | 160 | 120 | 200 |

| Mauritius | 340 | 280 | 420 | 19.8 | 16.1 | 24.2 | 210 | 180 | 260 |

| Morocco | 3210 | 2390 | 4070 | 10.3 | 7.7 | 13 | 2480 | 1860 | 3110 |

| Mozambique | 900 | 650 | 1190 | 8.7 | 6.4 | 11.4 | 830 | 610 | 1090 |

| Namibia | 130 | 100 | 170 | 9.7 | 7.7 | 12.3 | 110 | 90 | 140 |

| Niger | 410 | 290 | 560 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 7.6 | 370 | 280 | 510 |

| Nigeria | 7080 | 5310 | 8960 | 8.9 | 6.9 | 11 | 6380 | 4880 | 8140 |

| Rwanda | 550 | 420 | 700 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 11.7 | 480 | 380 | 610 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 16 | 11 | 22 | 16.5 | 12 | 22.2 | 14 | 10 | 19 |

| Senegal | 630 | 500 | 800 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 11.1 | 590 | 470 | 730 |

| Seychelles | 38 | 34 | 44 | 35.7 | 31.4 | 40.6 | 26 | 23 | 30 |

| Sierra Leone | 240 | 190 | 320 | 7.1 | 5.5 | 9.1 | 220 | 170 | 290 |

| Somalia | 330 | 210 | 620 | 5 | 3.1 | 9.2 | 310 | 200 | 580 |

| South Africa | 5570 | 5000 | 6290 | 12.9 | 11.6 | 14.5 | 4600 | 4160 | 5200 |

| South Sudan | 370 | 240 | 550 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 14.7 | 350 | 220 | 530 |

| Sudan | 1560 | 1110 | 2340 | 8.2 | 6 | 12.3 | 1260 | 900 | 1850 |

| Togo | 280 | 200 | 370 | 8.2 | 6.1 | 10.5 | 250 | 180 | 320 |

| Tunisia | 1800 | 1300 | 2440 | 14.5 | 10.5 | 19.5 | 1150 | 840 | 1550 |

| Uganda | 1740 | 1350 | 2150 | 12.3 | 9.8 | 14.8 | 1520 | 1190 | 1860 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 2460 | 1930 | 3180 | 10.1 | 8.1 | 12.7 | 2180 | 1730 | 2790 |

| Zambia | 920 | 670 | 1200 | 13.6 | 10.1 | 17.4 | 790 | 580 | 1020 |

| Zimbabwe | 930 | 710 | 1180 | 13.8 | 10.6 | 17.2 | 820 | 620 | 1030 |

| Location | Age-standardised death rate | DALYs counts | Age-standardised DALYs rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 95% UI | 2019 | 95% UI | 2019 | 95% UI | ||||

| Africa | 8.1 | 7.4 | 8.8 | 1,300,000 | 1,140,000 | 1,460,000 | 180 | 160 | 200 |

| Algeria | 8 | 6.4 | 9.8 | 57,600 | 45,200 | 72,400 | 170 | 130 | 210 |

| Angola | 9.7 | 7.8 | 12 | 27,800 | 20,700 | 35,900 | 220 | 170 | 280 |

| Benin | 7.6 | 6.2 | 9.5 | 8500 | 6500 | 11,300 | 160 | 130 | 210 |

| Botswana | 15.8 | 11.6 | 20.5 | 5200 | 3500 | 7100 | 350 | 240 | 460 |

| Burkina Faso | 7.3 | 5.8 | 9.1 | 15,400 | 11,900 | 19,900 | 160 | 120 | 200 |

| Burundi | 7.2 | 5.2 | 10.1 | 8900 | 6200 | 12,900 | 170 | 120 | 240 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 9.4 | 7.6 | 11.5 | 23,400 | 17,400 | 30,300 | 200 | 160 | 250 |

| Cabo Verde | 11.4 | 9 | 13.4 | 1000 | 800 | 1100 | 220 | 180 | 260 |

| Cameroon | 10.6 | 8.3 | 13.8 | 30,000 | 21,600 | 40,900 | 230 | 170 | 300 |

| Central African Republic | 6.4 | 4.7 | 8.8 | 4000 | 2800 | 5600 | 160 | 110 | 220 |

| Chad | 7.4 | 5.8 | 9.3 | 9800 | 7400 | 13,000 | 160 | 120 | 210 |

| Comoros | 8.6 | 6.4 | 10.8 | 1000 | 700 | 1300 | 190 | 140 | 250 |

| Congo | 11.4 | 8.8 | 14.5 | 7500 | 5300 | 10,200 | 260 | 190 | 340 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 6.2 | 4.1 | 9.5 | 56,300 | 38,100 | 83,800 | 140 | 100 | 210 |

| Djibouti | 11.2 | 8.7 | 14.7 | 1700 | 1200 | 2500 | 250 | 180 | 350 |

| Egypt | 7.4 | 5.4 | 10.1 | 133,000 | 95,300 | 183,300 | 180 | 130 | 250 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 14.2 | 9.1 | 20 | 1700 | 1000 | 2500 | 310 | 190 | 450 |

| Eritrea | 10 | 7.9 | 12.7 | 7600 | 5700 | 10,100 | 240 | 180 | 310 |

| Eswatini | 13.5 | 9.3 | 18.2 | 1900 | 1300 | 2700 | 300 | 200 | 430 |

| Ethiopia | 7.3 | 5.5 | 10.4 | 79,000 | 58,500 | 109,700 | 170 | 120 | 240 |

| Gabon | 14.9 | 11.3 | 18.2 | 3700 | 2600 | 4800 | 330 | 240 | 420 |

| Gambia | 6.6 | 4.8 | 8.8 | 1500 | 1000 | 2000 | 140 | 100 | 190 |

| Ghana | 8.8 | 7 | 10.9 | 34,900 | 26,500 | 45,100 | 190 | 150 | 250 |

| Guinea | 7.2 | 5.5 | 9.2 | 9400 | 7000 | 12,400 | 160 | 120 | 210 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 9.1 | 6.9 | 11.3 | 1700 | 1200 | 2200 | 210 | 150 | 260 |

| Kenya | 8.1 | 6.5 | 10 | 45,300 | 35,300 | 57,200 | 180 | 140 | 230 |

| Lesotho | 11.7 | 8.7 | 15.1 | 3600 | 2500 | 4800 | 270 | 190 | 350 |

| Liberia | 6.7 | 4.6 | 9.5 | 3200 | 2100 | 4500 | 140 | 100 | 200 |

| Libya | 12.5 | 9.1 | 15.8 | 17,100 | 12,300 | 22,500 | 300 | 220 | 390 |

| Madagascar | 7.1 | 5.3 | 9.3 | 21,600 | 15,500 | 29,000 | 170 | 120 | 220 |

| Malawi | 6.1 | 4.7 | 7.5 | 10,700 | 7900 | 13,900 | 130 | 100 | 170 |

| Mali | 7.8 | 6.3 | 9.7 | 16,300 | 12,500 | 21,000 | 170 | 140 | 220 |

| Mauritania | 8.3 | 6.5 | 10.3 | 3600 | 2600 | 4700 | 170 | 120 | 210 |

| Mauritius | 12.8 | 10.5 | 15.5 | 5100 | 4100 | 6200 | 290 | 240 | 360 |

| Morocco | 8.5 | 6.3 | 10.5 | 63,600 | 47,400 | 81,100 | 190 | 150 | 250 |

| Mozambique | 8.7 | 6.5 | 11.2 | 22,400 | 15,800 | 29,800 | 190 | 140 | 250 |

| Namibia | 8.7 | 7 | 10.8 | 2800 | 2100 | 3700 | 190 | 150 | 240 |

| Niger | 5.6 | 4.2 | 7.5 | 10,100 | 7200 | 14,000 | 120 | 90 | 160 |

| Nigeria | 8.6 | 6.7 | 10.8 | 157,300 | 116,500 | 205,200 | 170 | 130 | 220 |

| Rwanda | 8.8 | 7.1 | 10.8 | 13,300 | 10,000 | 17,500 | 200 | 150 | 250 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 15.2 | 11.2 | 20.6 | 400 | 200 | 500 | 320 | 230 | 430 |

| Senegal | 8.7 | 7.1 | 10.8 | 14,400 | 11,000 | 18,600 | 180 | 140 | 230 |

| Seychelles | 25.3 | 22.2 | 28.7 | 600 | 500 | 700 | 550 | 490 | 630 |

| Sierra Leone | 7 | 5.4 | 8.9 | 5800 | 4300 | 7600 | 150 | 110 | 190 |

| Somalia | 5 | 3.2 | 9.3 | 9600 | 6100 | 17,900 | 120 | 80 | 230 |

| South Africa | 11.2 | 10.1 | 12.6 | 111,500 | 100,300 | 126,600 | 240 | 220 | 270 |

| South Sudan | 10 | 6.6 | 14.8 | 9500 | 5900 | 14,700 | 220 | 140 | 340 |

| Sudan | 7.1 | 5.3 | 10.6 | 34,700 | 24,000 | 50,900 | 160 | 120 | 240 |

| Togo | 7.9 | 5.9 | 10 | 6700 | 4800 | 9000 | 170 | 120 | 220 |

| Tunisia | 9.7 | 7.2 | 13 | 26,500 | 19,100 | 36,100 | 210 | 150 | 280 |

| Uganda | 11.6 | 9.2 | 13.8 | 43,100 | 32,500 | 54,500 | 270 | 210 | 330 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 9.5 | 7.7 | 11.8 | 59,000 | 45,100 | 78,200 | 220 | 170 | 280 |

| Zambia | 12.6 | 9.5 | 16 | 23,300 | 16,600 | 30,700 | 300 | 220 | 380 |

| Zimbabwe | 12.9 | 9.9 | 16.2 | 22,800 | 17,100 | 29,300 | 300 | 220 | 370 |

Table 3.

Percentage changes of national incidence cases, deaths and DALYs in Africa from 2010 to 2019

| Location | Incidence cases | ASIR | Death counts | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | ||||

| Africa | 48 | 34 | 62 | 11 | 1 | 21 | 41 | 28 | 55 |

| Algeria | 57 | 24 | 98 | 10 | − 12 | 38 | 43 | 14 | 79 |

| Angola | 68 | 36 | 114 | 14 | − 4 | 43 | 63 | 31 | 105 |

| Benin | 42 | 19 | 70 | 3 | − 12 | 21 | 40 | 19 | 65 |

| Botswana | 51 | 19 | 92 | 9 | − 11 | 36 | 41 | 12 | 77 |

| Burkina Faso | 59 | 35 | 92 | 18 | 2 | 39 | 55 | 32 | 85 |

| Burundi | 40 | 15 | 73 | 0 | − 17 | 21 | 39 | 15 | 69 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 39 | 11 | 73 | 4 | − 14 | 25 | 38 | 12 | 69 |

| Cabo Verde | 77 | 39 | 112 | 48 | 15 | 78 | 65 | 28 | 100 |

| Cameroon | 47 | 18 | 83 | 6 | − 14 | 29 | 41 | 14 | 75 |

| Central African Republic | 16 | − 8 | 45 | − 8 | − 25 | 13 | 16 | − 8 | 45 |

| Chad | 40 | 15 | 68 | 6 | − 11 | 27 | 37 | 14 | 63 |

| Comoros | 44 | 17 | 75 | 10 | − 10 | 32 | 40 | 14 | 68 |

| Congo | 53 | 23 | 90 | 9 | − 11 | 33 | 49 | 20 | 84 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 63 | 29 | 104 | 20 | − 4 | 49 | 58 | 26 | 97 |

| Djibouti | 77 | 40 | 125 | 13 | − 8 | 39 | 71 | 35 | 115 |

| Egypt | 59 | 18 | 110 | 20 | − 9 | 56 | 45 | 9 | 89 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 60 | 20 | 120 | 13 | − 13 | 52 | 53 | 16 | 105 |

| Eritrea | 47 | 21 | 79 | 9 | − 8 | 32 | 43 | 19 | 73 |

| Eswatini | 20 | − 7 | 61 | − 2 | − 22 | 28 | 16 | − 9 | 55 |

| Ethiopia | 62 | 33 | 92 | 21 | − 1 | 42 | 56 | 30 | 83 |

| Gabon | 37 | 9 | 72 | 7 | − 13 | 32 | 31 | 5 | 63 |

| Gambia | 47 | 15 | 81 | 13 | − 10 | 39 | 43 | 13 | 75 |

| Ghana | 53 | 26 | 86 | 14 | − 5 | 35 | 48 | 22 | 77 |

| Guinea | 19 | − 2 | 46 | 7 | − 11 | 29 | 16 | − 4 | 40 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 29 | 6 | 57 | 2 | − 15 | 22 | 27 | 5 | 54 |

| Kenya | 53 | 29 | 79 | 9 | − 7 | 27 | 46 | 26 | 69 |

| Lesotho | 25 | − 2 | 57 | 12 | − 11 | 40 | 20 | − 5 | 50 |

| Liberia | 34 | 8 | 68 | 3 | − 16 | 27 | 31 | 6 | 63 |

| Libya | 35 | − 3 | 76 | − 8 | − 33 | 19 | 35 | − 1 | 75 |

| Madagascar | 47 | 17 | 84 | 5 | − 15 | 30 | 44 | 16 | 79 |

| Malawi | 38 | 11 | 67 | 3 | − 15 | 22 | 36 | 10 | 62 |

| Mali | 42 | 18 | 70 | 7 | − 10 | 28 | 38 | 16 | 65 |

| Mauritania | 41 | 10 | 71 | 8 | − 14 | 29 | 35 | 8 | 63 |

| Mauritius | 54 | 23 | 90 | 16 | − 6 | 43 | 47 | 20 | 80 |

| Morocco | 61 | 31 | 99 | 25 | 1 | 54 | 48 | 21 | 82 |

| Mozambique | 44 | 12 | 82 | 15 | − 8 | 44 | 40 | 11 | 77 |

| Namibia | 47 | 18 | 81 | 18 | − 4 | 44 | 37 | 12 | 68 |

| Niger | 57 | 30 | 91 | 9 | − 8 | 28 | 55 | 29 | 86 |

| Nigeria | 41 | 6 | 84 | 8 | − 17 | 38 | 38 | 7 | 82 |

| Rwanda | 72 | 42 | 109 | 17 | − 2 | 39 | 67 | 38 | 100 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 50 | 23 | 74 | 22 | 2 | 42 | 40 | 17 | 63 |

| Senegal | 46 | 19 | 78 | 13 | − 7 | 36 | 42 | 17 | 72 |

| Seychelles | 49 | 29 | 69 | 15 | 0 | 31 | 37 | 19 | 55 |

| Sierra Leone | 48 | 20 | 82 | 10 | − 9 | 34 | 42 | 17 | 74 |

| Somalia | 35 | 8 | 66 | − 1 | − 19 | 19 | 34 | 9 | 64 |

| South Africa | 22 | 8 | 39 | − 5 | − 15 | 8 | 16 | 4 | 32 |

| South Sudan | 24 | 1 | 55 | 1 | − 16 | 25 | 23 | 0 | 54 |

| Sudan | 57 | 28 | 93 | 22 | 0 | 48 | 45 | 20 | 80 |

| Togo | 53 | 25 | 88 | 7 | − 12 | 27 | 49 | 22 | 81 |

| Tunisia | 53 | 18 | 101 | 13 | − 12 | 48 | 38 | 8 | 79 |

| Uganda | 54 | 25 | 88 | 12 | − 7 | 34 | 51 | 23 | 81 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 50 | 22 | 79 | 12 | − 7 | 33 | 46 | 21 | 74 |

| Zambia | 63 | 29 | 101 | 11 | − 11 | 36 | 53 | 22 | 90 |

| Zimbabwe | 29 | 4 | 61 | 4 | − 15 | 29 | 27 | 3 | 58 |

| Location | ASDR | DALYS counts | Age-standardised DALYS rate change | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | Value (%) | 95% UI (%) | ||||

| Africa | 6 | − 3 | 16 | 41 | 27 | 56 | 6 | − 5 | 16 |

| Algeria | 1 | − 19 | 24 | 39 | 9 | 76 | − 1 | − 23 | 26 |

| Angola | 11 | − 8 | 36 | 59 | 25 | 101 | 7 | − 17 | 41 |

| Benin | 2 | − 12 | 19 | 41 | 16 | 71 | 5 | − 14 | 27 |

| Botswana | 3 | − 16 | 27 | 40 | 8 | 80 | 5 | − 23 | 45 |

| Burkina Faso | 16 | 0 | 35 | 61 | 34 | 98 | 21 | 0 | 50 |

| Burundi | − 1 | − 17 | 18 | 40 | 14 | 74 | 0 | − 20 | 26 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 3 | − 14 | 22 | 36 | 6 | 71 | 7 | − 14 | 34 |

| Cabo Verde | 41 | 8 | 70 | 62 | 30 | 94 | 19 | − 4 | 47 |

| Cameroon | 2 | − 16 | 24 | 41 | 12 | 81 | 3 | − 20 | 33 |

| Central African Republic | − 8 | − 25 | 13 | 15 | − 9 | 45 | − 8 | − 32 | 23 |

| Chad | 5 | − 11 | 25 | 38 | 14 | 68 | 8 | − 12 | 34 |

| Comoros | 7 | − 11 | 28 | 45 | 12 | 78 | 10 | − 16 | 36 |

| Congo | 7 | − 13 | 30 | 47 | 15 | 87 | 0 | − 24 | 31 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 17 | − 5 | 45 | 60 | 25 | 102 | 16 | − 9 | 49 |

| Djibouti | 9 | − 11 | 32 | 66 | 28 | 116 | 8 | − 17 | 38 |

| Egypt | 10 | − 15 | 41 | 46 | 9 | 92 | 6 | − 20 | 37 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 9 | − 15 | 46 | 53 | 11 | 114 | − 1 | − 30 | 45 |

| Eritrea | 7 | − 10 | 29 | 41 | 14 | 72 | 9 | − 15 | 38 |

| Eswatini | − 6 | − 25 | 22 | 11 | − 15 | 51 | − 9 | − 36 | 34 |

| Ethiopia | 16 | − 4 | 36 | 54 | 27 | 81 | 13 | − 8 | 38 |

| Gabon | 3 | − 15 | 25 | 31 | 2 | 68 | − 4 | − 27 | 27 |

| Gambia | 11 | − 11 | 34 | 44 | 11 | 80 | 13 | − 14 | 45 |

| Ghana | 10 | − 8 | 29 | 46 | 18 | 81 | 7 | − 14 | 31 |

| Guinea | 5 | − 12 | 25 | 22 | − 1 | 49 | 6 | − 15 | 32 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 | − 15 | 21 | 26 | 3 | 57 | 2 | − 18 | 28 |

| Kenya | 5 | − 9 | 21 | 44 | 23 | 71 | 7 | − 13 | 35 |

| Lesotho | 9 | − 13 | 35 | 23 | − 5 | 56 | 9 | − 23 | 47 |

| Liberia | 3 | − 15 | 24 | 36 | 7 | 72 | 4 | − 17 | 30 |

| Libya | − 8 | − 32 | 18 | 35 | − 5 | 77 | − 10 | − 38 | 18 |

| Madagascar | 4 | − 15 | 27 | 45 | 15 | 82 | 6 | − 17 | 35 |

| Malawi | 2 | − 15 | 20 | 36 | 7 | 68 | 4 | − 20 | 30 |

| Mali | 5 | − 11 | 24 | 41 | 15 | 73 | 4 | − 16 | 27 |

| Mauritania | 4 | − 15 | 24 | 31 | 0 | 64 | 0 | − 22 | 23 |

| Mauritius | 10 | − 10 | 34 | 38 | 11 | 71 | 11 | − 10 | 37 |

| Morocco | 17 | − 4 | 44 | 45 | 17 | 78 | 5 | − 16 | 31 |

| Mozambique | 13 | − 9 | 41 | 42 | 9 | 82 | 15 | − 15 | 57 |

| Namibia | 11 | − 8 | 35 | 37 | 8 | 72 | 10 | − 18 | 45 |

| Niger | 8 | − 9 | 25 | 55 | 26 | 90 | 10 | − 9 | 34 |

| Nigeria | 7 | − 16 | 37 | 39 | 4 | 91 | 9 | − 25 | 62 |

| Rwanda | 14 | − 4 | 34 | 63 | 32 | 100 | 13 | − 8 | 39 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | 17 | − 1 | 35 | 48 | 20 | 75 | 9 | − 11 | 30 |

| Senegal | 10 | − 8 | 32 | 43 | 13 | 78 | 13 | − 12 | 42 |

| Seychelles | 8 | − 5 | 22 | 40 | 22 | 60 | 6 | − 13 | 28 |

| Sierra Leone | 7 | − 10 | 29 | 45 | 17 | 83 | 10 | − 12 | 38 |

| Somalia | − 2 | − 18 | 17 | 33 | 8 | 64 | 0 | − 20 | 27 |

| South Africa | − 9 | − 17 | 3 | 13 | 0 | 30 | − 10 | − 24 | 7 |

| South Sudan | 0 | − 17 | 23 | 22 | − 3 | 58 | 2 | − 17 | 34 |

| Sudan | 15 | − 5 | 39 | 47 | 17 | 86 | 10 | − 14 | 40 |

| Togo | 4 | − 13 | 24 | 46 | 17 | 82 | 8 | − 14 | 33 |

| Tunisia | 2 | − 20 | 32 | 35 | 4 | 79 | 0 | − 25 | 33 |

| Uganda | 10 | − 9 | 30 | 51 | 19 | 87 | 14 | − 11 | 46 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 10 | − 7 | 29 | 47 | 17 | 81 | 14 | − 8 | 40 |

| Zambia | 6 | − 15 | 29 | 55 | 19 | 97 | 7 | − 18 | 38 |

| Zimbabwe | 3 | − 16 | 28 | 29 | 3 | 64 | 3 | − 23 | 40 |

In terms of death counts in both sexes, Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, and Ethiopia were the leading four countries with 6380 (4880–8140), 4600 (4160–52), 4560 (3300–6270), and 2850 (2130–4000) deaths respectively in 2019. Comoros 40 (30–50), Seychelles 26 (23–30), and Sao Tome and Principe 14 (10–19) had lowest death counts in 2019. In 2019, Seychelles 25.3 (22.2–28.7), Botswana 15.8 (11.6–20.5), Sao Tome and Principe 15.2 (11.2–20.6), and Gabon 14.9 (11.3–18.2) per 100,000 had a highest age-standardised death rate whereas Democratic Republic of the Congo 6.2 (4.1–9.5), Malawi 6.1 (4.7–7.5), Niger 5.6 (4.2–7.5), and Somalia 5 (3.2–9.3) per 100,000 had a lowest age-standardised death rate (Table 2). From 2010 to 2019, highest percentage change of death counts due to CRC observed in Djibouti 71% (35–115%), Rwanda 67% (38–100%), Cabo Verde 65% (28–100%), Angola 63% (31–105%), Democratic Republic of the Congo 58% (26–97%), and Ethiopia 56% (30–83%) while lowest change observed in Eswatini 16% (− 9 to 55%), Guinea 16% (− 4 to 40%), Central African Republic 16% (− 8 to 45%), and South Africa 16% (4–32%). Cabo Verde 41% (8–70%), Democratic Republic of the Congo 17% (− 5 to 45%), Morocco 17% (− 4 to 44%) had highest percentage change of age-standardised death rate, while Burundi—1% (− 17 to 18%), Somalia—2% (− 18 to 17%), Eswatini—6% (− 25 to 13%), Central African Republic—8% (− 25 to 13%), Libya—8% (− 32 to 18%), and South Africa—9% (− 17 to 3%) had decreased age-standardised death rate from 2010 to 2019 (Table 3).

In 2019, DALYs counts due to CRC in Africa were ranging from 400 to 157, 3000. The four leading countries in terms of DALYs counts in both sexes were Nigeria 157,300 (116,500–205,200), Egypt 133,000 (95,300–183,300), South Africa 111,500 (100,300–126,600), and Ethiopia 79,000 (58,500–109,700) while Comoros, Seychelles, and Sao Tome and Principe had lowest DALYs counts with 1000 (700–1300), 600 (500–700) and 400 (200–500) respectively in 2019. In 2019, Seychelles 550 (490–630), Botswana 350 (240–460), Gabon 330 (240–420), Sao Tome and Principe 320 (230–430), and Equatorial Guinea 310 (190–450) per 100,000 had highest DALYs counts, whereas Malawi 130 (100–170), Niger 120 (90–160), and Somalia 120 (80–230) per 100,000 had lowest DALYs counts in Africa (Table 2). From 2010 to 2019, Djibouti 66% (28–116%), Rwanda 63% (32–100%), Cabo Verde 62% (30–94%), Burkina Faso 61% (34–98%), and Democratic Republic of the Congo 60% (25–102) had highest percentage change DALYs counts, while Central African Republic 15% (− 9 to 45%), South Africa 13% (0–30%), and Eswatini 11% (− 15 to 51%) lowest percentage of DALYs counts in Africa. From 2010 to 2019, Decreased age-standardised DALYs rate was observed in Algeria—1% (− 23 to 26%), Equatorial Guinea—1% (− 30 to 45%), Gabon—4% (− 27 to 27%), Central African Republic—8% (− 32 to 23%), Eswatini—9% (− 36 to 34%), Libya—10% (− 38 to 18%), and South Africa—10% (− 24 to 7%) (Table 3).

Discussion

From 2010 to 2019, age-standardised rates and counts of incidence cases, deaths, and DALYs of colorectal cancer in Africa increased with heterogeneous trend across the nations. The absolute numbers of incidence cases of CRC have increased in Asia, America, and Europe as well as worldwide. In addition to this, age standardised incidence rate of CRC also raised from 2010 to 2019 globally and in all regions except in Europe. Changes of incidence cases ranged from 16% in Central African Republic to 77% in Djibouti. More than 90% of countries had increased age-standardised incidence rate, however, decreased age-standardised incidence rate observed in Somalia, Eswatini, South Africa, Central African Republic, and Libya. This trend of CRC has attributed to population growth, aging, changing risk factors, adopting screening, increasing diagnosis, and registration of colorectal cancer mainly in Africa and Asia. Increased absolute incident cases and age-standardised incidence rate of CRC indicates that change in environmental, demographic, epidemiological, and sociodemographic have played a significant role in rising of burden of colorectal cancer in Africa. More than 55% [6] of colorectal cancer can be prevented with evidence based modification of strong modifiable risk factors such as smoking [13], weight gain [14], alcohol consumption [15], and lack of physical inactivity [16] and unhealthy diet. Change of living standards in transition countries in North Africa has exposed new risk factors such as sedentary life and metabolic syndrome. The colorectal cancer has a male predilection with peaking 60–69 years; however, the disparity is not much as western. This might be due to males have higher prevalence rates of modifiable risk factors such as smoking [17], alcohol consumption [18] and protective effect of estrogen for CRC in females [19].

From 2010 to 2019, we found that death counts and age-standardised death rates of CRC have increased in Africa. Increased death counts were also observed in America, Asia, Europe and globally. However, trend of age-standardised death rate of CRC has decreased in America, Europe and global as whole with slight stable change in Asia. From 2010 to 2019, heterogeneity trend and burden of CRC mortality has noticed across nations of Africa. Mortality CRC related has increased significantly, ranging from 16 to 71% with more than 90% of countries had increased age-standardised death rate, however, decreased age-standardised incidence rate was observed only in Burundi, Somalia, Eswatini, South Africa, Central African Republic, and Libya. Increased absolute colorectal cancer related mortality and age-standardised death rate have associated to increased population size and change age structure, decreasing mortality from other disease, increased risk factors, low rate of screening, diagnosis, and, treatment in Africa. There are a strong evidence described that mortality and incidence of colorectal cancer can be reduced through screening. Apply primary, secondary and tertiary prevention modality such as reduction of modifiable risk factors and adopting evidence based screening modality are key steps to achieve sustainable development goals [10] and 25 by 25 targets [9] of colorectal cancer.

DALYs measurement is an important indicator of quality of CRC cares. Results from this study revealed that absolute DALYs counts and age-standardised rates of CRC have increased between 2010 and 2019 in Africa. Increased DALYs counts of colorectal cancer is a global phenomenon, however, change in Africa as compared with Asia, America, Europe, and global as a whole was invariably significant. Despite regions and global have increased DALYs counts of CRC between 2010 and 2019, trend of age-standardised DALYs rate of CRC was decreasing in America, Europe and global as whole with slight stable in Asia. Most of DALYs was contributed from YLL in Africa, which indicates low survival rate. Increased age-standardised rate of death and DALYs of colorectal cancer indicates low efforts and progresses for CRC standard and qualitive care-early diagnosis and treatment, primary prevention of modifiable risk factors and implementation of secondary prevention modality in Africa and across most nations. This serious effect would be due to poor cancer infrastructure and policy, low workforce capacity, cancer center to diagnosis and treatment, low finical security and low of universal health coverage in Africa. Geographical variation of screening of CRC has attributed to geographic variation in CRC incidence, ability in identify the target population at risk, economic resource, human resource capacity, health care structure, infrastructure, and health care policy and direction [20]. Evidence from mathematical modeling study recommended that colonoscopy screen in Africa begins at age of 50 years [21]. Estimated efficacy of colorectal screening ranged from 2.6% (single screen with fecal occult blood test) to over 50% (such as colonoscopy every 10 years, or annual fecal occult blood test and sigmoidoscopy every 5 years) [21]. However, recommendation of population based CRC screen in Africa is questionable due high burden of communicable disease, low human capacity, availability of colonoscopy, and relatively low burden of CRC as compared as other health condition [22]. Several factors might have contributed to low rate of quality of CRC care in Africa such as inaccessibility of screening [20], early detection, low quality and skill in oncological surgery, inaccessibility of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, target therapy and palliative therapy [23].

Limitation

GBD studies provide qualitive, compressive, and up-dated evidence of global, regional and national burden of diseases for policy maker, researcher and planner. This study has played a great and invaluable role, particularly for Africa. The main limitation of this study is unavailability and quality of data sources. Therefore, African nation should have improved cancer registration, collaborated and provided data to IHME, and follow the prediction and give feedback.

Conclusion

Increased age-standardised rate of incidence, death and DALYs have been observed in Africa and across a nations. Evidence from this analysis showed that there is fast rising burden of colorectal cancer due to increased prevalence of modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol, unhealthy diet, sedentary lifestyle, and metabolic syndrome. Observation indicates that there are low efforts and progresses in CRC standard and qualitative care-evidence based early diagnosis and treatment, primary prevention of modifiable risk factors and implementation of secondary prevention modality. This alarm all nations and global community to call integrated, comparative and resilience measures for prevention, awareness creation, adopting screening, and evidence based treatments and rehabilitations.

Acknowledgements

We send special appreciation and respection to IHME staffs and collaborators for their commitment and energy for producing Global Burden of Disease study output.

Abbreviations

- AAPC

Annual average percentage change

- ASDR

Age-standardized death rate

- ASIR

Age-standardized incidence rate

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- GBD

Global Burden of Disease

- IHME

Institute of Heath Metrics and Evaluation

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

A.F. and Z.A. conceptualized of the study, A.F. and W.B. drafted the manuscript, A.F. generate all data from GBD 2019 tools, A.F., Z.A., W.B. write the result, Z.A. and A.F. write discussion, A.F. and W.B. table and figure preparation, A.F., Z.A., W.B. finalized the final paper. All authors approved the final version of manuscript.

Funding

No funding given for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available in GBD 2019 tools (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Atalel Fentahun Awedew, Email: atalel.fentahun@aau.edu.et.

Zelalem Asefa, Email: zelalem.asefa@aau.edu.et.

Woldemariam Beka Belay, Email: weldemariambeka@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Cancer C. Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1749–1768. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2019 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66(4):683–691. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xi Y, Xu P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(10):101174. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Cancer Society. Colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2020-2022.pdf. 2020 (2020).

- 7.Dekker E, Tanis PJ, Vleugels JLA, Kasi PM, Wallace MB. Colorectal cancer. The Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1467–1480. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32319-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granados-Romero JJ, Valderrama-Treviño AI, Contreras-Flores EH, Barrera-Mera B, Herrera Enríquez M, Uriarte-Ruíz K, et al. Colorectal cancer: a review. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5(11):4667. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20174914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nation. High level meeting on prevention and control of non-communicable diseases (2011).

- 10.UN. Sustainable developments goals 2015–2030 (2015).

- 11.GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GBD 2017 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(12):913–933. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30345-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Botteri E, Iodice S, Bagnardi V, Raimondi S, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P. Smoking and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(23):2765–2778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karahalios A, English DR, Simpson JA. Weight change and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(11):832–845. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, Rota M, Scotti L, Islami F, et al. Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2011;22(9):1958–1972. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolin KY, Yan Y, Colditz GA, Lee IM. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(4):611–616. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;19(397):2337–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy N, Strickler HD, Stanczyk FZ, Xue X, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE, et al. A prospective evaluation of endogenous sex hormone levels and colorectal cancer risk in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(10):djv210. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schreuders EH, Ruco A, Rabeneck L, Schoen RE, Sung JJ, Young GP, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: a global overview of existing programmes. Gut. 2015;64(10):1637–1649. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-309086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginsberg GM, Lauer JA, Zelle S, Baeten S, Baltussen R. Cost effectiveness of strategies to combat breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: mathematical modelling study. BMJ. 2012;344:e614. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert R, Sauvaget C, Sankaranarayanan R. Mass screening for colorectal cancer is not justified in most developing countries. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(2):253–256. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boland GM, Chang GJ, Haynes AB, Chiang Y-J, Chagpar R, Xing Y, et al. Association between adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines and improved survival in patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(8):1593–1601. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in GBD 2019 tools (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool).