Abstract

Background

Few data on the management of acute phase of traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI) in patients suffering polytrauma are available. As the therapeutic choices in the first hours may have a deep impact on outcome of tSCI patients, we conducted an international survey investigating this topic.

Methods

The survey was composed of 29 items. The main endpoints of the survey were to examine: (1) the hemodynamic and respiratory management, (2) the coagulation management, (3) the timing of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and spinal surgery, (4) the use of corticosteroid therapy, (5) the role of intraspinal pressure (ISP)/spinal cord perfusion pressure (SCPP) monitoring and (6) the utilization of therapeutic hypothermia.

Results

There were 171 respondents from 139 centers worldwide. A target mean arterial pressure (MAP) target of 80–90 mmHg was chosen in almost half of the cases [n = 84 (49.1%)]. A temporary reduction in the target MAP, for the time strictly necessary to achieve bleeding control in polytrauma, was accepted by most respondents [n = 100 (58.5%)]. Sixty-one respondents (35.7%) considered acceptable a hemoglobin (Hb) level of 7 g/dl in tSCI polytraumatized patients. An arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) of 80–100 mmHg [n = 94 (55%)] and an arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) of 35–40 mmHg [n = 130 (76%)] were chosen in most cases. A little more than half of respondents considered safe a platelet (PLT) count > 100.000/mm3 [n = 99 (57.9%)] and prothrombin time (PT)/activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) < 1.5 times the normal control [n = 85 (49.7%)] in patients needing spinal surgery. MRI [n = 160 (93.6%)] and spinal surgery [n = 158 (92.4%)] should be performed after intracranial, hemodynamic, and respiratory stabilization by most respondents. Corticosteroids [n = 103 (60.2%)], ISP/SCPP monitoring [n = 148 (86.5%)], and therapeutic hypothermia [n = 137 (80%)] were not utilized by most respondents.

Conclusions

Our survey has shown a great worldwide variability in clinical practices for acute phase management of tSCI patients with polytrauma. These findings can be helpful to define future research in order to optimize the care of patients suffering tSCI.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13017-022-00422-2.

Keywords: Polytrauma, Traumatic spinal cord injury, Management

Background

Traumatic spinal cord injury (tSCI) is a devastating condition with a worldwide annual incidence ranging from near 10–80 cases for 1 million people [1, 2]. The most frequent causes of tSCI are falls from height and road traffic collisions, with an association of multisystem trauma up to 80% in the latter case [1, 3]. From a pathophysiological point of view, tSCI and traumatic brain injury (TBI) have some similarities [3, 4]. In tSCI, as in TBI, we observe primary and secondary injuries; the latter, in particular, can be further exacerbated by dangerous secondary insults (hypoxia and hypotension) with possible higher severity in unstable polytrauma patients [3, 4]. Unfortunately, little is known regarding the acute phase management of tSCI patients with multisystem trauma. As in TBI, the therapeutic choices in the first hours can have a deep impact on the outcome and prognosis of tSCI patients. For these reasons, we conducted an international survey investigating the practices in the acute phase management in polytrauma patients with associated SCI.

Methods

Ethical considerations

This survey addresses the acute phase management practices in polytrauma patients having SCI. Participants voluntarily agreed to join the survey. Therefore, this study did not need an ethical approval. Participants did not receive compensation for their participation in the survey; all those who agreed are identified as contributors at the end of the manuscript.

Study design

This is a cross-sectional structured survey among the members of the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) and the European Association of Neurological Surgeons (EANS).

Sample size

This survey was distributed to the WSES and EANS members through their respective websites. Accordingly, sample size calculation was not needed and response rate could not be calculated as it used the media for communication.

Questionnaire design

This online questionnaire had 29 questions (Additional file 1). It was divided into 7 sections which were: (1) demographic (questions 1–6), (2) hemodynamic and respiratory management (questions 7–13), (3) coagulation management (questions 14–16), (4) timing of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and surgical spinal decompression/stabilization (questions 17–21), (5) use of corticosteroid therapy (question 22), (6) the role of intraspinal pressure (ISP)/spinal cord perfusion pressure (SCPP) monitoring [with/without cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage] (questions 23–27) and (7) utilization of therapeutic hypothermia (questions 28–29).

The questionnaire was written initially by two authors (EP and FC). An international panel of topic experts (number = 15) critically read and finalized the questionnaire. The final version of the survey was endorsed by the WSES.

Distribution of the survey and data collection

An invitation to participate in the questionnaire was announced and distributed through a link in the WSES and the EANS websites during the period of November 1, 2020 through March 31, 2021. Furthermore, investigators targeted physicians who are involved in the acute care of polytrauma patients with tSCI [American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale grade A–D without TBI]. The online entered data were stored in a database which was only accessed by the principal investigators and was protected by a secure password.

Statistical analysis

Data were downloaded from the online database, stored in an Excel file (Microsoft, Redmont, USA), and revised to assure the accuracy of the data. Only complete questionnaires were included in the final analysis. Descriptive statistics are reported as number (percentage). Comparisons between neurosurgeons versus non-neurosurgeons and between centers with an high admission trauma rate (> 250 polytrauma patients/year) versus low admission rate (< 250 polytrauma patients/year) were planned. Chi Square test or Fisher’s Exact test was used to compare categorical data of independent groups as appropriate. Cells with small values (0–3) were grouped with adjacent cells, where clinically reasonable. When grouping was not feasible, the cells were removed (grouped and removed cells are shown in the tables). Considering the exploratory and descriptive nature of the study, we did not find it necessary to correct for multiple comparisons, as it would be in the context of an experimental hypothesis testing that has been specified a priori [5]. In R × C tables, if the overall statistical test was significant, a post hoc test to detect the source of significance was done with the Fisher’s Exact test as suggested by Shan et al. [6], with the Hochberg’s [7] method to adjust for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using STATA 13.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX) software.

Results

The number of respondents was 171 from 139 centers in 42 countries worldwide. The majority of respondents were from Italy [n = 35 (20.5%)], USA [n = 33 (19.3%)] and Qatar [n = 16 (9.4%)] (Additional file 2: Table S1). Baseline characteristics of the survey participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of respondents were neurosurgeons [n = 61 (35.7%)] and Emergency/Trauma surgeons [n = 57 (33.3%)]. One hundred and twelve respondents (65.5%) worked in a level I trauma center.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the survey participants

| Total | |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Speciality | |

| Int Care | 25 (14.6) |

| Anesth | 8 (4.7) |

| Em Med | 5 (2.9) |

| E/T Surg | 57 (33.3) |

| N Surg | 61 (35.7) |

| Orth | 10 (5.8) |

| other | 5 (3) |

| Years of practice with tSCI | |

| < 5 | 26 (15.2) |

| 6–10 | 37 (21.6) |

| 11–15 | 38 (22.2) |

| 16–20 | 18 (10.5) |

| 21–25 | 22 (12.9) |

| > 25 | 30 (17.5) |

| Trauma Center Level | |

| I | 112 (65.5) |

| II | 21 (12.3) |

| III | 38 (22.2) |

| Major Trauma/year | |

| < 50 | 17 (9.9) |

| 50–100 | 35 (20.5) |

| 100–250 | 38 (22.2) |

| 250–500 | 34 (19.9) |

| > 500 | 47 (27.5) |

| Pts with tSCI/year | |

| < 20 | 42 (24.6) |

| 20–30 | 43 (25.1) |

| 30–40 | 31 (18.1) |

| 40–50 | 22 (12.9) |

| > 50 | 33 (19.3) |

Int Care intensive care, Anesth anesthesia, Em Med emergency medicine, E/T surg emergency trauma surgery, N surg neurosurgery, Orth orthopedics, tSCI traumatic spinal cord injury, Pts patients

Cardiorespiratory management

Target mean arterial pressure (MAP) and hemoglobin (Hb) levels in polytrauma patients with tSCI are reported in Table 2. A target MAP of 80–90 mmHg was chosen in less than half of cases [n = 84 (49.1%)]. Sixty-eight respondents (39.8%) kept a default target MAP for at least 72 h. For the time strictly necessary to achieve bleeding control in polytrauma, a temporary reduction in the MAP target, was accepted by the majority of respondents [n = 100 (58.5%)]. Sixty-one respondents (35.7%) considered acceptable a Hb target of 7 g/dl in tSCI polytraumatized patients. The presence of tSCI in the setting of polytrauma did not change the Hb target [n = 125 (73.1%)]. The arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) and carbon dioxide (PaCO2) targets in polytrauma patients with tSCI are reported in Table 2. A PaO2 of 80–100 mmHg [n = 94 (55%)] and a PaCO2 of 35–40 mmHg [n = 130 (76%)] were chosen in most cases.

Table 2.

Cardiorespiratory and coagulation management

| Total | |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| MAP target in polytrauma with tSCI | |

| 60–70 mm Hg | 14 (8.2) |

| 70–80 mm Hg | 40 (23.4) |

| 80–90 mm Hg | 84 (49.1) |

| 90–100 mm Hg | 32 (18.7) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) |

| Time length of MAP target | |

| 24 h | 18 (10.5) |

| 48 h | 26 (15.2) |

| 72 h | 68 (39.8) |

| 4 d | 5 (2.9) |

| 5 d | 17 (9.9) |

| 6 d | 1 (0.6) |

| 7 d | 34 (19.9) |

| Other | 2 (1.2) |

| Reduction in MAP target to achieve bleeding control | |

| Yes | 100 (58.5) |

| No | 71 (41.5) |

| Hb target in polytrauma without tSCI | |

| 7 g/dL | 61 (35.7) |

| 8 g/dL | 47 (27.5) |

| 9 g/dL | 31 (18.1) |

| 10 g/dL | 31 (18.1) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) |

| Hb target in case of tSCI | |

| Does not change | 125 (73.1) |

| Increases | 43 (25.1) |

| Decreases | 3 (1.8) |

| PaO2 target | |

| 60–80 mm Hg | 22 (12.9) |

| 80–100 mm Hg | 94 (55.0) |

| 100–120 mm Hg | 43 (25.1) |

| > 120 mm Hg | 4 (2.3) |

| Other | 8 (4.7) |

| PaCO2 target | |

| < 35 mm Hg | 14 (8.2) |

| 35–40 mm Hg | 130 (76.0) |

| 40–45 mm Hg | 19 (11.1) |

| > 45 mm Hg | 0 (0.0) |

| other | 8 (4.7) |

| PLTs count target | |

| > 50.000/μL | 59 (34.5) |

| > 100.000/μL | 99 (57.9) |

| > 250.000/μL | 13 (7.6) |

| PT/aPTT target for tSCI Surgery | |

| < 1.2 normal control | 81 (47.4) |

| < 1.5 normal control | 85 (49.7) |

| < 1.8 normal control | 5 (2.9) |

| Usefulness of POC test | |

| Yes | 109 (63.7) |

| No | 62 (36.3) |

MAP mean arterial pressure, tSCI traumatic spinal cord injury, Hb hemoglobin, PaO2 arterial partial pressure of oxygen, PaCO2 arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, PLTs platelets, PT prothrombin time, aPTT activated partial thromboplastin time, POC point-of-care

Coagulation management (Table 2)

Near half of respondents considered safe a platelet (PLT) count > 100.000/mm3 [n = 99 (57.9%)] and prothrombin time (PT)/activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) < 1.5 times the normal control [n = 85 (49.7%)] in tSCI polytrauma patients needing spinal surgery (decompression/stabilization). Point-of-care (POC) tests [i.e., thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM)] were also considered useful in this scenario [n = 109 (63.7%)].

MRI and spinal surgery (decompression/stabilization) timing (Table 3)

Table 3.

MRI/spinal surgery timing, ISP/SPP monitoring and neuroprotective therapies

| Total | |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Spinal surgery after intracranial, hemodynamic and respiratory stabilization? | |

| Yes | 158 (92.4) |

| No | 13 (7.6) |

| MRI after intracranial, hemodynamic and respiratory stabilization? | |

| Yes | 160 (93.6) |

| No | 11 (6.4) |

| Timing of MRI in ASIA grade A-D | |

| Within 3 h | 74 (43.3) |

| Within 6 h | 38 (22.2) |

| Within 12 h | 20 (11.7) |

| Within 24 h | 20 (11.7) |

| Within 48 h | 4 (2.3) |

| Within 72 h | 6 (3.5) |

| Other | 9 (5.3) |

| Timing of spinal decompression/stabilization in ASIA grade A | |

| Within 6 h | 48 (28.1) |

| Within 12 h | 26 (15.2) |

| Within 24 h | 54 (31.6) |

| Within 48 h | 19 (11.1) |

| Within 72 h | 13 (7.6) |

| Other | 11 (6.4) |

| Timing of spinal decompression/stabilization in ASIA grade B-D | |

| Within 6 h | 58 (33.9) |

| Within 12 h | 31 (18.1) |

| Within 24 h | 57 (33.3) |

| Within 48 h | 15 (8.8) |

| Within 72 h | 8 (4.7) |

| Other | 2 (1.2) |

| Corticosteroids therapy in tSCI | |

| Yes as NASCIS II/III | 47 (27.5) |

| Yes but lower than NACSIS | 18 (10.5) |

| No | 103 (60.2) |

| Other | 3 (1.8) |

| Monitoring of ISP/SPP in tSCI | |

| Frequently | 8 (4.7) |

| In few cases | 15 (8.8) |

| Never | 148 (86.5) |

| Is ISP/SPP monitoring useful in tSCI? | |

| Yes | 87 (50.9) |

| No | 84 (49.1) |

| CSF drainage in tSCI | |

| Yes | 35 (20.5) |

| No | 136 (79.5) |

| Therapeutic hypothermia in tSCI | |

| Frequently | 3 (1.8) |

| In few cases | 31 (18.1) |

| Never | 137 (80.1) |

| Is therapeutic hypothermia useful in tSCI? | |

| Yes | 45 (26.3) |

| No | 126 (73.7) |

MRI magnetic resonance imaging, ASIA American Spinal Injury Association, tSCI traumatic spinal cord injury, ISP intraspinal pressure, SPP spinal perfusion pressure, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, NASCIS National Acute SCI study

MRI [n = 160 (93.6%)] and spinal surgery (decompression/stabilization) [n = 158 (92.4%)] should be performed after intracranial, hemodynamic and respiratory stabilization by the majority of respondents in tSCI polytraumatized patients. MRI could be performed within 3 h from the trauma [n = 74 (43.3%)]. The most frequent answers regarding timing for spinal surgery were within 24 h [n = 54 (31.6%)] and within 6 h [n = 48 (28.1%)] in ASIA grade A. Similarly, spinal surgery could be performed within 6 h [n = 58 (33.9%)] and within 24 h [n = 57 (33.3%)] in ASIA grade B–D.

Corticosteroid therapy (Table 3)

Corticosteroids were not utilized by the majority of respondents [n = 103 (60.2%)]. When used, these were administered as in the National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Studies (NASCIS II and III) [8, 9] [n = 47 (27.5%)] or at a lower dose [n = 18 (10.5%)].

ISP/SCPP monitoring (Table 3)

ISP/SCPP monitoring was generally not utilized [n = 148 (86.5%)] despite being considered useful by about half of the respondents [n = 87 (51%)].

The CSF drainage in tSCI was also utilized in few cases [n = 35 (20.5%)].

Therapeutic hypothermia (Table 3)

Therapeutic hypothermia was never utilized in tSCI polytrauma patients in most cases [n = 137 (80%)] and considered not useful [n = 126 (73.7%)].

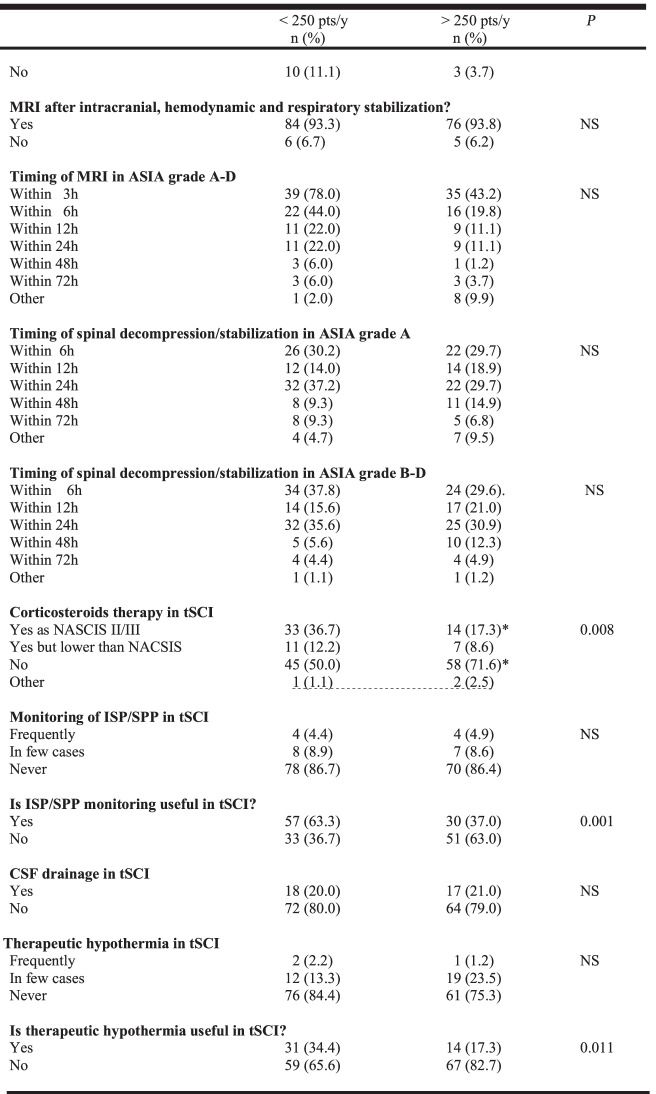

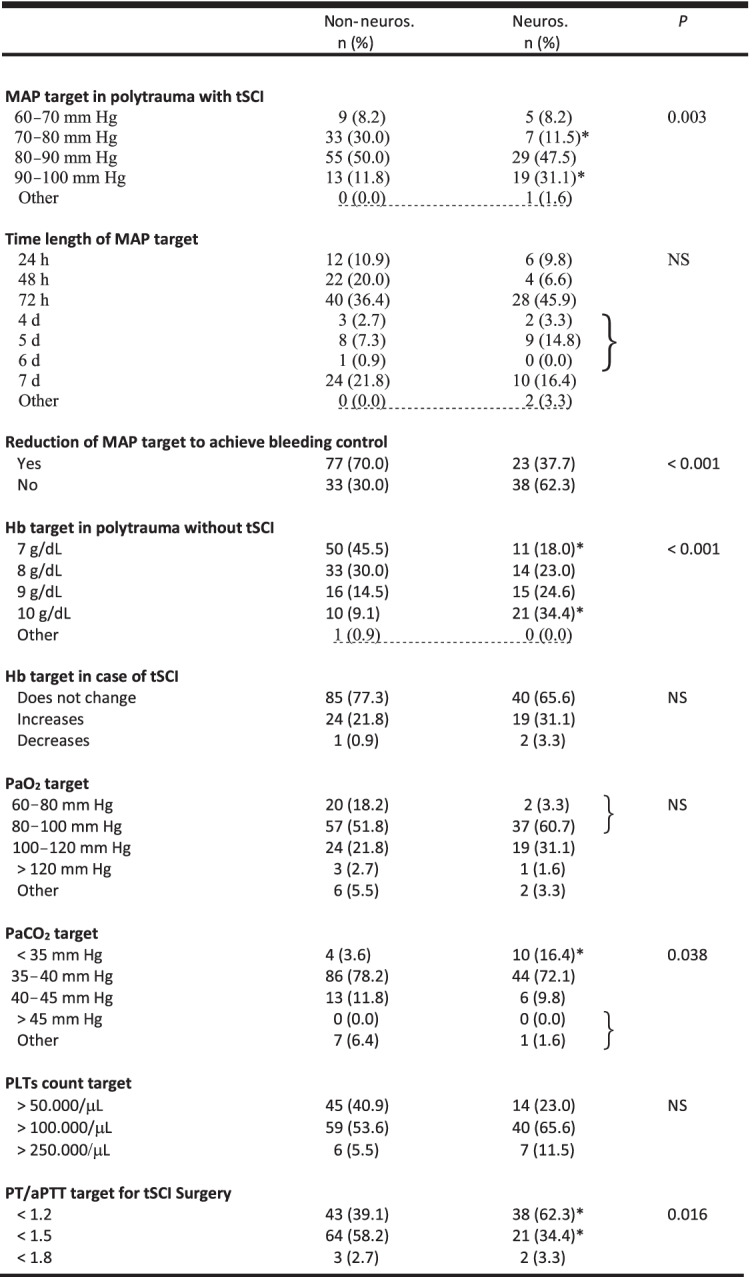

Neurosurgeons versus non-neurosurgeons (Table 4)

Table 4.

Comparison of neurosurgeons vs. non-neurosurgeons

neuros neurosurgeons, MAP mean arterial pressure, tSCI traumatic spinal cord injury, Hb hemoglobin, PaO2 arterial partial pressure of oxygen, PaCO2 arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, PLTs platelets, PT prothrombin time, aPTT activated partial thromboplastin time, POC point-of-care, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, ASIA American Spinal Injury Association, ISP intraspinal pressure, SPP spinal perfusion pressure, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, NASCIS National Acute SCI study, NS not significant

* = P < 0.05 vs Non-Neuros at the post hoc analysis

A curly bracket indicates that the cells were grouped for statistical purposes

Dotted underline means that cells were removed for statistical purposes

Considering the comparison between neurosurgeons and non-neurosurgeons, the statistically significant differences refer to:

Target MAP (more non-neurosurgeons considered safe a target MAP of 70–80 mmHg and more neurosurgeons considered safe a target MAP of 90–100 mmHg)

Temporary reduction in the target MAP to achieve bleeding control (more in the non-neurosurgeons group)

Target Hb (more non-neurosurgeons considered safe a target Hb of 7 g/dl and more neurosurgeons considered safe a target Hb of 10 g/dl)

Target PaCO2 (more neurosurgeons considered safe a target PaCO2 < 35 mmHg)

Target PT/aPTT (more neurosurgeons considered safe a target PT/aPTT < 1.2 normal control and more non-neurosurgeons considered safe a target PT/aPTT target < 1.5 normal control)

POC tests (more useful in the non-neurosurgeons group)

Timing of MRI in stable tSCI polytrauma patients (ASIA grade A–D) (more neurosurgeons suggested performing MRI within 3 h after injury)

Corticosteroid therapy (more non-neurosurgeons did not utilize corticosteroid therapy, and more neurosurgeons utilized corticosteroids as in NASCIS II /III trials).

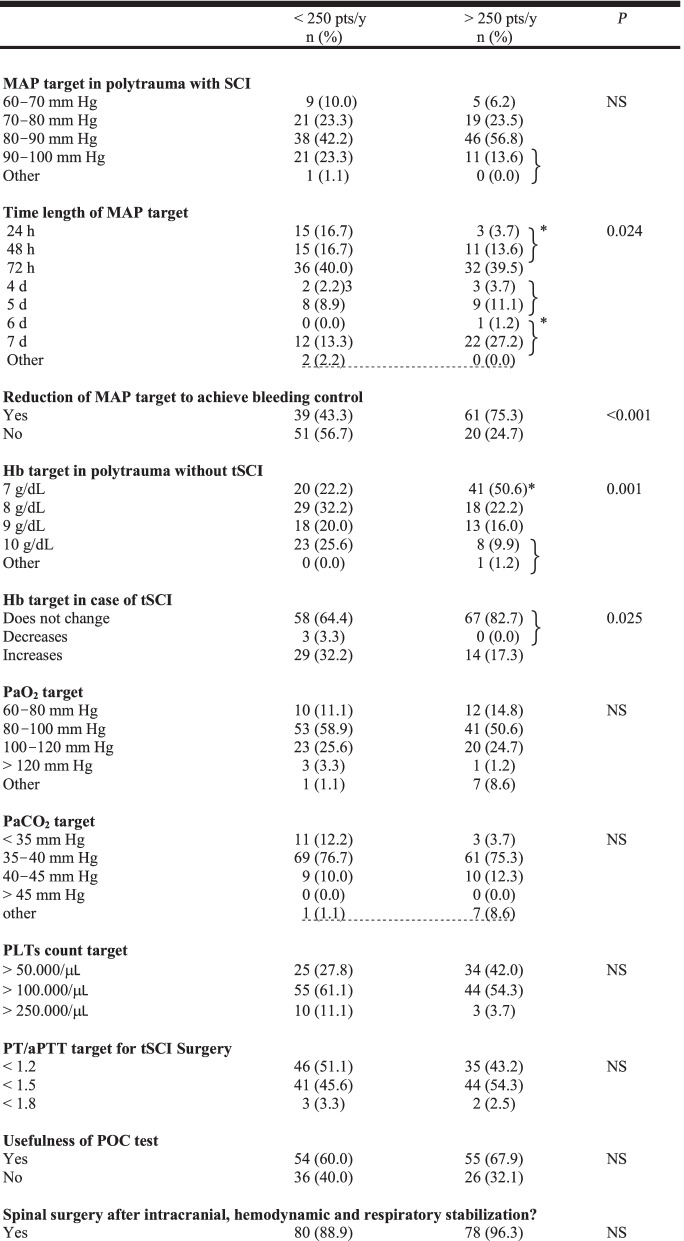

Trauma centers with polytrauma patients’ admission < 250/year versus > 250/year (Table 5)

Table 5.

Comparison of trauma centers with polytrauma patients admission < 250/year versus > 250/year

pts patients, y year, MAP mean arterial pressure, tSCI traumatic spinal cord injury, Hb hemoglobin, PaO2 arterial partial pressure of oxygen, PaCO2 arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide, PLTs platelets, PT prothrombin time, aPTT activated partial thromboplastin time, POC point-of-care, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, ASIA American Spinal Injury Association, ISP intraspinal pressure, SPP spinal perfusion pressure, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, NASCIS National Acute SCI study, NS not significant

* = P < 0.05 versus < 250 pts/y at the post hoc analysis

A curly bracket indicates that the cells were grouped for statistical purposes

Dotted underline means that cells were removed for statistical purposes

Regarding the comparison between trauma centers with polytrauma patients’ admission < 250/year and > 250/year, the statistically significant differences refer to:

Maintenance of target MAP (more respondents in the group with < 250 pts/year maintained target MAP for 24/48 h and fewer respondents in the group with < 250 pts/years maintained the target MAP for more than 6 days)

Temporary reduction in the target MAP to achieve bleeding control (more in the > 250/year group)

Target Hb (more physicians working in the > 250/year group considered safe a target Hb of 7 g/dl in polytrauma patients without tSCI; the presence of tSCI led to an increase in the target Hb in the < 250/year group)

Corticosteroids therapy (more physicians in the > 250/year group did not utilize corticosteroids therapy, and more physicians in the < 250/year group utilized corticosteroids as in the NASCIS II/III studies)

ISP/SCPP monitoring (more useful in the < 250/year group)

Therapeutic hypothermia (less useful in the > 250/year group)

Discussion

This international survey provides important information regarding worldwide acute phase management practices in polytrauma tSCI patients with particular focus on (1) cardiorespiratory management, (2) coagulation management, (3) MRI/spinal surgery timing, (4) corticosteroid therapy, (5) ISP/SCPP monitoring and (6) therapeutic hypothermia.

Cardiorespiratory management

A cardiorespiratory dysfunction (arterial hypotension, hypoxia, etc.) is frequently observed after tSCI, particularly when the injury occurs at high spinal cord levels, and is associated with an unfavourable neurological outcome [1]. This condition can be exacerbated further in unstable polytrauma patients [3]. The most recent guidelines by the Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) for the management of tSCI patients recommend the maintenance of MAP between 85 and 90 mm Hg for the first 7 days following an acute cervical SCI (Level III) [10]. This recommendation is poorly adopted by most of our respondents which consider safe the maintenance of a MAP value of 80–90 mmHg only for 3 days. Higher than recommended MAP values are deemed safe for neurosurgeons, maybe reflecting a greater attention for spine perfusion. These data suggest that additional educational efforts are required to increase clinical awareness concerning established and published recommendations to improve outcomes in tSCI patients.

Traditionally, the “golden hour” treatment of injured patients with or at risk of hemorrhagic shock consisted in an aggressive fluid resuscitation, at a 3:1 ratio with the estimated blood loss, to maintain a normal MAP to allow peripheral tissue perfusion. While this represented a huge step forward to decrease mortality from trauma, soon it was demonstrated that massive volume replacement has its drawbacks in terms of tissue oedema and impaired metabolic response; therefore it was speculated that aggressive resuscitation would jeopardize our efforts to rescue hemorrhagic patients. Permissive hypotension was introduced with the aim to reduce the risks of fluid overload while maintaining an adequate tissue oxygenation. However, the optimal tissue perfusion pressure has not been determined yet [11]. While it has been suggested to maintain a MAP around 70 mmHg in torso trauma patients, this target has been considered insufficient to maintain brain perfusion in patients with severe head trauma [12]. In the literature there is no specific evidence to guide the application of permissive hypotension to spine trauma but considering the frequent association between spine and head trauma, it seems logical to make any effort to maintain a MAP around 85–90 mmHg.

For the time strictly necessary to achieve bleeding control in polytrauma, a temporary reduction in the target MAP, was accepted by little more than half of respondents and more non-neurosurgeons and physicians working in high- volume centers. Probably, the choice of the respondents could be influenced by the increase in worldwide utilization of damage control resuscitation (DCR) protocols in polytrauma patients [13]. However, targeted parameters for maintenance of blood pressure should be higher in polytrauma patients with tSCI.

Guidelines for the management of tSCI patients do not refer to optimal Hb values, and data from high-quality studies in this setting are lacking [10, 14]. However, most respondents consider acceptable a target Hb of 7 g/dl in tSCI polytraumatized patients, and the presence of tSCI in the setting of polytrauma does not influence this strategy. This approach, mainly adopted by non-neurosurgeons and physicians working in high-volume centers, could reflect recommendations derived from different trauma guidelines [15, 16].

As for Hb values, data regarding optimal PaO2 and PaCO2 targets in tSCI polytrauma patients are lacking. In most cases, a PaO2 of 80–100 mmHg and a PaCO2 of 35–40 mmHg were chosen. This choice could be affected by what is recommended in patients with acute brain damage [17].

Coagulation management

The most recent European guideline concerning the management of major hemorrhage and coagulopathy following trauma [16] recommended that PT and aPTT be maintained < 1.5 times the normal control (grade 1C) and the PLT count be maintained above 50,000/mm3 (grade 1C). In addition, the maintenance of a PLT count > 100,000/mm3 was also recommended for patients with ongoing bleeding and/or TBI (grade 2C) [14] and in the case of neurosurgery [18]. To our knowledge, no specific guidelines regarding coagulation management in tSCI patients have been published, to date. However, POC tests (i.e., TEG, ROTEM, etc.) are increasingly used to evaluate coagulation function in trauma patients with hemorrhagic complications [16, 19]. In particular, these tests can be utilized to obtain a rapid assessment of hemostasis, to assist in clinical decision-making and to provide critical information about specific coagulation deficiencies, especially in patients taking novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) and in the evaluation of PLTs dysfunction induced by trauma and/or drugs [14, 19]. Most of the respondents are in accordance with these recommendations. Moreover, regarding PT and aPTT, predominantly neurosurgeons also have a more conservative approach.

MRI/Spinal surgery timing

MRI, providing a detailed image of the spinal cord and related soft tissues, is very important in influencing the treatment and prognosis of tSCI patients [2, 20]. However, considering its duration of execution and technical characteristics, it may be dangerous in cardiorespiratory unstable polytrauma patients. For this reason, as also remarked by the majority of the respondents, it could be performed after intracranial, hemodynamic, and respiratory stabilization.

Recent guidelines suggest that MRI should be performed in adult patients with acute SCI: (a) before surgical intervention, when feasible, to facilitate improved clinical decision making (Quality of Evidence: Very Low, Strength of Recommendation: Weak) and (b) in the acute period following SCI, before or after surgical intervention, to improve prediction of neurologic outcome (Quality of Evidence: Low Strength of Recommendation: Weak) [20]. However, an accurate and precise timing for MRI in tSCI patients is not clearly defined and probably needs to be determined. For most of the respondents, particularly neurosurgeons, MRI could be performed within 3 h from the trauma in stable patients.

Recent studies suggest as early decompressive surgery (performed within 24 h from trauma) is associated with better neurological outcomes, thus highlighting the concept of “time is spine” [21, 22]. A more rapid approach (within 12 h or less) was also proposed in case of the incomplete spinal lesion (ASIA B–D) [23–25]. Recent guidelines “suggest that early surgery (< 24 h after injury) be considered as a treatment option in adult patients with traumatic central cord syndrome (Quality of Evidence: Low. Strength of Recommendation: Weak) and that early surgery be offered as an option for adult acute SCI patients regardless of level (Quality of Evidence: Low. Strength of Recommendation: Weak)” [26]. The majority of the respondents are in agreement with the timing as mentioned above, and a more rapid approach (< 6 h from trauma) was also preferred in cases of incomplete spinal lesions (ASIA B–D). The optimal timing of spinal surgery in tSCI polytrauma patients needs to be established and individualized after intracranial, hemodynamic and respiratory stabilization, as most of the respondents remarked.

Corticosteroid therapy

The utilization of methylprednisolone sodium succinate (MPSS) after tSCI is a debated and controversial topic. Guidelines from the CNS [27] do not recommend its use at all (Level I), whereas guidelines from the AO spine [28] suggest: (1) “not offering a 24-h infusion of high-dose MPSS to adult patients who present after 8 h with acute SCI”; (2) “a 24-h infusion of high-dose MPSS to adult patients within 8 h of acute SCI as a treatment option,” and (3) “not offering a 48-h infusion of high-dose MPSS to adult patients with acute SCI.” The majority of the respondents agreed with the CNS guidelines. However, more neurosurgeons (compared with non-neurosurgeons) and more physicians working in low- volume centers utilize corticosteroids. This may reflect the contrast between the two guidelines [27, 28]. Probably this topic will have to be evaluated in future well-performed studies.

ISP/SCPP monitoring

Recently, interest in ISP/SCPP monitoring was increased [29]. The ISP can be evaluated by surgically implanting an intradural extramedullary probe at the injury site [29–32]. In this way, it is possible to obtain SCPP (MAP-ISP) that can be considered a more accurate way to monitor spinal cord perfusion with respect to MAP, such as cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) in TBI [29]. A SCPP > 50 mm Hg is proven to be a strong predictor of improved neurologic recovery following SCI [30, 32]. In this regard, SCPP could provide useful information to guide the hemodynamic management of acute SCI patients.

More data are also necessary to increase the use of this type of monitoring in daily clinical practice. The responses collected in the survey are consistent with this aspect. However, our results also reflect the paucity of data regarding the role of CSF drainage in acute SCI [33].

Therapeutic hypothermia

Hypothermia, through various mechanisms, can play a role in preventing secondary injury after SCI [34]. Moreover, more data are necessary for its application in daily clinical practice [34]. Most of the respondents do not utilize this type of therapeutic approach or consider it useful.

Limitations

We have to acknowledge that our study has several limitations First, the number of the respondents was relatively small. This may reflect a selection bias with those more interested in this area which limits its generalizability. Second, this survey reflects personal opinions and practices which may be subjective or affected by recall bias. Third, 60% of the responders were from three countries which represents a geographical bias. Forth, using a web-based survey with secondary distribution hinders the ability to calculate the response rate. However, we were encouraged to find that we obtained responses from 139 centers worldwide. Finally, to be more focused and to improve the response rate by making the questionnaire short we have defined specific important topics excluding other questions which may be equally important.

Conclusions

Great worldwide great variability in clinical practices for acute phase management of tSCI patients with polytrauma was identified from the survey results. This finding can be helpful be helpful to optimize the care of patients having tSCI and to define future research questions to be answered.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2. Table S1 – Countries of respondents.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank WSES and EANS for the support.

LIST of CONTRIBUTORS*

Italy: Francesco Domenichelli, Gennaro Perrone, Carlo Giussani, Graziano Taddei, Osvaldo Chiara, Marco Meloni, Carlo Coniglio, Stefano Romoli, Nino Stocchetti, Giuseppe Citerio, Teresa Perra, Claudio Bernucci, Luca Longhi, Alberto Balestrino, Massimiliano Visocchi, Pasquale De Bonis, Francesco Costa, Laura Lippa, Giovanni Pinna, Maurizio Passanisi, Massimiliano Maria Pina, Simona Bistazzoni, Maximilian Broger, Maurizio Magliulo, Mario Giuffrida, Roberto Colasanti, Cristian Lupi, Vitaliano F. Muzii.

Brazil: José Mauro da Silva Rodrigues, Bruno M. Pereira, Gustavo P. Fraga, Ricardo, Alessandro Teixeira Gonsaga.

United Kingdom: Charalampos Seretis, Mario Ganau, Edoardo Viaroli, Andreas Demetriades.

Paraguay: Gustavo M. Machain.

Greece: Eftychios Lostoridis, Orestis Ionnadis.

Turkey: Arda Isik.

South Africa: Timothy Hardcastle, Victor Kong.

United Arab Emirates: Fikri Abu-Zidan.

The Netherlands: Edward Tan, Vincent J.M. Leferink, Wilco Peul.

Chile: Cristian Godoy.

Israel: Miklosh Bala, Boris Kessel.

Canada: Gregory Hawrylux, Andrew Kirkpatrick.

Spain: Jesus Sanchez Ballesteros, Adriana Gil-Rodrigo, Juan A. Sinisterra, Fernando Clau.

Tunisia: Oussama Baraket.

USA: Rocco Armonda, Addisu Mesfin, Matthew Martin, Sabareesh Natarajan, Jeremy Cannon, Eelco F. Wijdicks, Manny Lorenzo, Marc de Moya, David Livingston, Therese Duane, Joe DuBose, Stuart Hershman, Joseph Schwab, Tom Scalea, Gary Schwartzbauer, Jose Diaz, Rosemary Kozar, Sharon Henry, Harold Fogel, Christos Lazaridis, Randall M. Chesnut, Alejandro Rabinstein, Jonathan Morrison, P. David Adelson, James Guest.

France: Pierre Bouzat, Salvatore Chibbaro.

Colombia: Andres M. Rubiano, Luis Ricaurte Arcos, Alvaro Ricardo Soto-Angel, Milton Barbosa, Oscar Gutirerrez Rincon, Sebastian Toro Lopez.

Iran: Amin Jahanbakhshi.

India: Swatantra Mishra, Subash Vohra, Dhaval Shukla, Yawar Shoaib Ali.

Russia: Mahir Gachabayov, Andrey Litvin.

Japan: Takahiro Kinoshita, So Kato.

Australia: Dieter Weber, Simone Meakes, Ed Martinez, Simon Abson.

Singapore: Vishal G Shelat.

Sweden: Niklas Marklund, Tal Horer.

Romania: Ioan-Alexandru Floriana, Ionut Negoi, Maria Mihaela Pop, Gheorghe Ungureanu.

Argentina: Daniel Oscar Pintos Chiesa, Ricardo Carmona, Martin Truszkowski, Fernando Palizas.

Perù: Pool Avila, Juan Luis Pinedo.

Belarus: Sergey Kirynela.

Iraq: Mazin S. Mohammed Jawad.

Qatar: Vishw Verma, Mohammad Alabdallat, Mohammed Farhat, Ibrahim Afifi, Yasir Al-Zubaidi, Ahad Kanbar, Suhail Yaqoob, Basil Younis, Hisham Aljogol, Sherwan Rashid M. Khoschnau, Suresh Kumar, Mushreq Ayesh, Talat Chughtai.

Hungary: Andras Buki.

Pakistan: Amer Aziz Ghurki.

Switzerland: Giulia Cossu.

Nepal: Bipin Chaurasia.

Indonesia: Yunus Kuntawi Aji.

Honduras: Ronny Leiva.

Vietnam: Duong Lx.

Moldova: Cauia Artur.

* only those who agree are reported as contributors.

Abbreviations

- tSCI

Traumatic spinal cord injury

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- WSES

World Society of Emergency Surgery

- EANS

European Association of Neurological Surgeons

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ISP

Intraspinal pressure

- SCPP

Spinal cord perfusion pressure

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- ASIA

American Spinal Injury Association

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- PaO2

Arterial partial pressure of oxygen

- PaCO2

Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PLT

Platelet

- PT

Prothrombin time

- aPTT

Activated partial thromboplastin time

- POC

Point-of-care

- TEG

Thromboelastography

- ROTEM

Rotational thromboelastometry

- NASCIS

National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study

- DCR

Damage control resuscitation

- NOACs

Novel oral anticoagulants

- MPSS

Methylprednisolone sodium succinate

- CNS

Congress of Neurological Surgeons

- CPP

Cerebral perfusion pressure

Author contributions

EP, CI and FC have designed the study. EP has performed acquisition of data. EP has done the analysis and interpretation of data. EP, CI, SR and FC have drafted the article. All authors have revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to be submitted.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Edoardo Picetti and Corrado Iaccarino contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Ahuja CS, Wilson JR, Nori S, Kotter MRN, Druschel C, Curt A, Fehlings MG. Traumatic spinal cord injury. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:17018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eli I, Lerner DP, Ghogawala Z. Acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Neurol Clin. 2021;39(2):471–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2021.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yue JK, Winkler EA, Rick JW, Deng H, Partow CP, Upadhyayula PS, Birk HS, Chan AK, Dhall SS. Update on critical care for acute spinal cord injury in the setting of polytrauma. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;43(5):E19. doi: 10.3171/2017.7.FOCUS17396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hachem LD, Ahuja CS, Fehlings MG. Assessment and management of acute spinal cord injury: from point of injury to rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017;40(6):665–675. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2017.1329076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing—when and how? J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:343–349. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shan G, Gerstenberger S. Fisher's exact approach for post hoc analysis of a chi-squared test. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0188709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometika. 1988;75(4):800–808. doi: 10.1093/biomet/75.4.800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Collins WF, Holford TR, Young W, Baskin DS, Eisenberg HM, Flamm E, Leo-Summers L, Maroon J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of methylprednisolone or naloxone in the treatment of acute spinal-cord injury. Results of the Second National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(20):1405–1411. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005173222001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bracken MB, Shepard MJ, Holford TR, Leo-Summers L, Aldrich EF, Fazl M, Fehlings M, Herr DL, Hitchon PW, Marshall LF, Nockels RP, Pascale V, Perot PL, Jr, Piepmeier J, Sonntag VK, Wagner F, Wilberger JE, Winn HR, Young W. Administration of methylprednisolone for 24 or 48 hours or tirilazad mesylate for 48 hours in the treatment of acute spinal cord injury. Results of the Third National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Randomized Controlled Trial. National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study. JAMA. 1997;277(20):1597–1604. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540440031029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryken TC, Hurlbert RJ, Hadley MN, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, Rozzelle CJ, Theodore N, Walters BC. The acute cardiopulmonary management of patients with cervical spinal cord injuries. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(Suppl 2):84–92. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318276ee16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodward L, Alsabri M. Permissive hypotension vs. conventional resuscitation in patients with trauma or hemorrhagic shock: a review. Cureus. 2021;13(7):e16487. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carney N, Totten AM, O'Reilly C, Ullman JS, Hawryluk GW, Bell MJ, Bratton SL, Chesnut R, Harris OA, Kissoon N, Rubiano AM, Shutter L, Tasker RC, Vavilala MS, Wilberger J, Wright DW, Ghajar J. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. Fourth Ed Neurosurg. 2017;80(1):6–15. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000001432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannon JW, Khan MA, Raja AS, Cohen MJ, Como JJ, Cotton BA, Dubose JJ, Fox EE, Inaba K, Rodriguez CJ, Holcomb JB, Duchesne JC. Damage control resuscitation in patients with severe traumatic hemorrhage: a practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(3):605–617. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Wilson JR, Kwon BK, Burns AS, Martin AR, Hawryluk G, Harrop JS. A clinical practice guideline for the management of acute spinal cord injury: introduction, rationale, and scope. Global Spine J. 2017;7(3 Suppl):84S–94S. doi: 10.1177/2192568217703387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picetti E, Rossi S, Abu-Zidan FM, Ansaloni L, Armonda R, Baiocchi GL, Bala M, Balogh ZJ, Berardino M, Biffl WL, Bouzat P, Buki A, Ceresoli M, Chesnut RM, Chiara O, Citerio G, Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Di Saverio S, Fraga GP, Gupta D, Helbok R, Hutchinson PJ, Kirkpatrick AW, Kinoshita T, Kluger Y, Leppaniemi A, Maas AIR, Maier RV, Minardi F, Moore EE, Myburgh JA, Okonkwo DO, Otomo Y, Rizoli S, Rubiano AM, Sahuquillo J, Sartelli M, Scalea TM, Servadei F, Stahel PF, Stocchetti N, Taccone FS, Tonetti T, Velmahos G, Weber D, Catena F. WSES consensus conference guidelines: monitoring and management of severe adult traumatic brain injury patients with polytrauma in the first 24 hours. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;29(14):53. doi: 10.1186/s13017-019-0270-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spahn DR, Bouillon B, Cerny V, Duranteau J, Filipescu D, Hunt BJ, Komadina R, Maegele M, Nardi G, Riddez L, Samama CM, Vincent JL, Rossaint R. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fifth edition. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2347-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robba C, Poole D, McNett M, Asehnoune K, Bösel J, Bruder N, Chieregato A, Cinotti R, Duranteau J, Einav S, Ercole A, Ferguson N, Guerin C, Siempos II, Kurtz P, Juffermans NP, Mancebo J, Mascia L, McCredie V, Nin N, Oddo M, Pelosi P, Rabinstein AA, Neto AS, Seder DB, Skrifvars MB, Suarez JI, Taccone FS, van der Jagt M, Citerio G, Stevens RD. Mechanical ventilation in patients with acute brain injury: recommendations of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine consensus. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(12):2397–2410. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hess AS, Ramamoorthy J, Hess JR. Perioperative platelet transfusions. Anesthesiology. 2021;134(3):471–479. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornblith LZ, Moore HB, Cohen MJ. Trauma-induced coagulopathy: the past, present, and future. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(6):852–862. doi: 10.1111/jth.14450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fehlings MG, Martin AR, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, Brodke D, Burns AS, Chiba K, Dettori JR, Furlan JC, Hawryluk G, Holly LT, Howley S, Jeji T, Kalsi-Ryan S, Kotter M, Kurpad S, Kwon BK, Marino RJ, Massicotte E, Merli G, Middleton JW, Nakashima H, Nagoshi N, Palmieri K, Singh A, Skelly AC, Tsai EC, Vaccaro A, Wilson JR, Yee A, Harrop JS. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with acute spinal cord injury: recommendations on the role of baseline magnetic resonance imaging in clinical decision making and outcome prediction. Global Spine J. 2017;7(3 Suppl):221S–230S. doi: 10.1177/2192568217703089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badhiwala JH, Wilson JR, Witiw CD, Harrop JS, Vaccaro AR, Aarabi B, Grossman RG, Geisler FH, Fehlings MG. The influence of timing of surgical decompression for acute spinal cord injury: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(2):117–126. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30406-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsieh YL, Tay J, Hsu SH, Chen WT, Fang YD, Liew CQ, Chou EH, Wolfshohl J, d'Etienne J, Wang CH, Tsuang FY. Early versus late surgical decompression for traumatic spinal cord injury on neurological recovery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38(21):2927–2936. doi: 10.1089/neu.2021.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fehlings MG, Rabin D, Sears W, Cadotte DW, Aarabi B. Current practice in the timing of surgical intervention in spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35(21 Suppl):S166–S173. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f386f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jug M, Kejžar N, Cimerman M, Bajrović FF. Window of opportunity for surgical decompression in patients with acute traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019;32:1–9. doi: 10.3171/2019.10.SPINE19888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ter Wengel PV, Feller RE, Stadhouder A, Verbaan D, Oner FC, Goslings JC, Vandertop WP. Timing of surgery in traumatic spinal cord injury: a national, multidisciplinary survey. Eur Spine J. 2018;27(8):1831–1838. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5551-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Wilson JR, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, Brodke DS, Burns AS, Chiba K, Dettori JR, Furlan JC, Hawryluk G, Holly LT, Howley S, Jeji T, Kalsi-Ryan S, Kotter M, Kurpad S, Marino RJ, Martin AR, Massicotte E, Merli G, Middleton JW, Nakashima H, Nagoshi N, Palmieri K, Singh A, Skelly AC, Tsai EC, Vaccaro A, Yee A, Harrop JS. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with acute spinal cord injury and central cord syndrome: recommendations on the timing (≤24 hours versus >24 hours) of decompressive surgery. Global Spine J. 2017;7(3 Suppl):195S–202S. doi: 10.1177/2192568217706367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurlbert RJ, Hadley MN, Walters BC, Aarabi B, Dhall SS, Gelb DE, Rozzelle CJ, Ryken TC, Theodore N. Pharmacological therapy for acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery. 2013;72(Suppl 2):93–105. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e31827765c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fehlings MG, Wilson JR, Tetreault LA, Aarabi B, Anderson P, Arnold PM, Brodke DS, Burns AS, Chiba K, Dettori JR, Furlan JC, Hawryluk G, Holly LT, Howley S, Jeji T, Kalsi-Ryan S, Kotter M, Kurpad S, Kwon BK, Marino RJ, Martin AR, Massicotte E, Merli G, Middleton JW, Nakashima H, Nagoshi N, Palmieri K, Skelly AC, Singh A, Tsai EC, Vaccaro A, Yee A, Harrop JS. A clinical practice guideline for the management of patients with acute spinal cord injury: recommendations on the use of methylprednisolone sodium succinate. Global Spine J. 2017;7(3 Suppl):203S–211S. doi: 10.1177/2192568217703085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC. Acute, severe traumatic spinal cord injury: monitoring from the injury site and expansion duraplasty. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2021;32(3):365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werndle MC, Saadoun S, Phang I, Czosnyka M, Varsos GV, Czosnyka ZH, Smielewski P, Jamous A, Bell BA, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC. Monitoring of spinal cord perfusion pressure in acute spinal cord injury: initial findings of the injured spinal cord pressure evaluation study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):646–655. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varsos GV, Werndle MC, Czosnyka ZH, Smielewski P, Kolias AG, Phang I, Saadoun S, Bell BA, Zoumprouli A, Papadopoulos MC, Czosnyka M. Intraspinal pressure and spinal cord perfusion pressure after spinal cord injury: an observational study. J Neurosurg Spine. 2015;23(6):763–771. doi: 10.3171/2015.3.SPINE14870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Squair JW, Bélanger LM, Tsang A, Ritchie L, Mac-Thiong JM, Parent S, Christie S, Bailey C, Dhall S, Street J, Ailon T, Paquette S, Dea N, Fisher CG, Dvorak MF, West CR, Kwon BK. Spinal cord perfusion pressure predicts neurologic recovery in acute spinal cord injury. Neurology. 2017;89(16):1660–1667. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon BK, Curt A, Belanger LM, Bernardo A, Chan D, Markez JA, Gorelik S, Slobogean GP, Umedaly H, Giffin M, Nikolakis MA, Street J, Boyd MC, Paquette S, Fisher CG, Dvorak MF. Intrathecal pressure monitoring and cerebrospinal fluid drainage in acute spinal cord injury: a prospective randomized trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;10(3):181–193. doi: 10.3171/2008.10.SPINE08217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martirosyan NL, Patel AA, Carotenuto A, Kalani MY, Bohl MA, Preul MC, Theodore N. The role of therapeutic hypothermia in the management of acute spinal cord injury. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;154:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 2. Table S1 – Countries of respondents.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.