Abstract

Background

Patients often do not get the information they require from doctors and nurses. To address this problem, interventions directed at patients to help them gather information in their healthcare consultations have been proposed and tested.

Objectives

To assess the effects on patients, clinicians and the healthcare system of interventions which are delivered before consultations, and which have been designed to help patients (and/or their representatives) address their information needs within consultations.

Search methods

We searched: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library (issue 3 2006); MEDLINE (1966 to September 2006); EMBASE (1980 to September 2006); PsycINFO (1985 to September 2006); and other databases, with no language restriction. We also searched reference lists of articles and related reviews, and handsearched Patient Education and Counseling (1986 to September 2006).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of interventions before consultations designed to encourage question asking and information gathering by the patient.

Data collection and analysis

Two researchers assessed the search output independently to identify potentially‐relevant studies, selected studies for inclusion, and extracted data. We conducted a narrative synthesis of the included trials, and meta‐analyses of five outcomes.

Main results

We identified 33 randomised controlled trials, from 6 countries and in a range of settings. A total of 8244 patients was randomised and entered into studies. The most common interventions were question checklists and patient coaching. Most interventions were delivered immediately before the consultations.

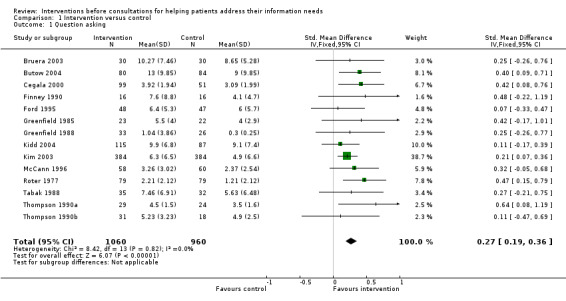

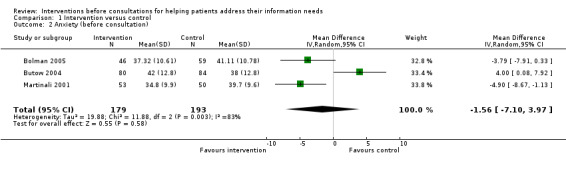

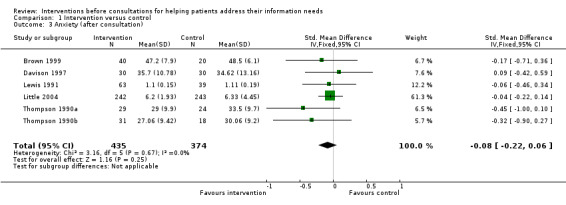

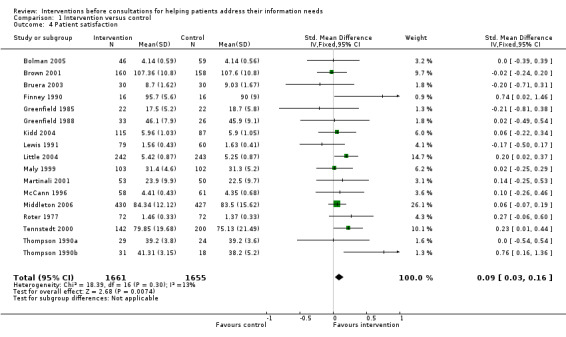

Commonly‐occurring outcomes were: question asking, patient participation, patient anxiety, knowledge, satisfaction and consultation length. A minority of studies showed positive effects for these outcomes. Meta‐analyses, however, showed small and statistically significant increases for question asking (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.27 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.19 to 0.36)) and patient satisfaction (SMD 0.09 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.16)). There was a notable but not statistically significant decrease in patient anxiety before consultations (weighted mean difference (WMD) ‐1.56 (95% CI ‐7.10 to 3.97)). There were small and not statistically significant changes in patient anxiety after consultations (reduced) (SMD ‐0.08 (95%CI ‐0.22 to 0.06)), patient knowledge (reduced) (SMD ‐0.34 (95% CI ‐0.94 to 0.25)), and consultation length (increased) (SMD 0.10 (95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.25)). Further analyses showed that both coaching and written materials produced similar effects on question asking but that coaching produced a smaller increase in consultation length and a larger increase in patient satisfaction.

Interventions immediately before consultations led to a small and statistically significant increase in consultation length, whereas those implemented some time before the consultation had no effect. Both interventions immediately before the consultation and those some time before it led to small increases in patient satisfaction, but this was only statistically significant for those immediately before the consultation. There appear to be no clear benefits from clinician training in addition to patient interventions, although the evidence is limited.

Authors' conclusions

Interventions before consultations designed to help patients address their information needs within consultations produce limited benefits to patients. Further research could explore whether the quality of questions is increased, whether anxiety before consultations is reduced, the effects on other outcomes and the impact of training and the timing of interventions. More studies need to consider the timing of interventions and possibly the type of training provided to clinicians.

Plain language summary

Interventions before healthcare consultations for helping patients get the information they require

Patients often report that they want more information from their healthcare providers or that the information they do receive does not address their needs. Generally, the amount of information given is small. People have differing needs for information, which also varies with the specific illness, but providing information is important as it helps patients recall, understand and follow treatment advice and be more satisfied. Clinicians may underestimate or undervalue the information needs of patients. They may also lack the skills to give information effectively. Training doctors and nurses probably helps, but another approach is to try to directly help patients ask questions in their consultations. This can be done by various methods such as question prompt sheets (which encourage patients to write down their questions) or coaching (when someone helps the patient to think of the questions they want to ask). This review evaluated studies of these types of interventions.

We identified 33 randomised controlled trials involving 8244 patients from six countries, mainly the USA, in a range of clinical settings. Most interventions, which included written materials (for example, question prompt sheets) and coaching sessions, were delivered in the waiting room immediately before the consultation. They were compared to dummy interventions or usual care. Health issues included primary care and family medicine, cancer, diabetes, heart problems, women's issues, peptic ulcer and mental illness.

We found small increases in question asking and patient satisfaction and a possible reduction in patient anxiety before and after consultations. We also found a possible reduction in patient knowledge and a possible small increase in consultation length. Both coaching and written materials produced similar effects on asking questions but coaching had a larger benefit in terms of patient satisfaction. Interventions immediately before the consultation led to a small increase in patient satisfaction whereas giving the intervention some time before did not. Interventions immediately before the consultation also resulted in small increases in consultation length, particularly when using written materials rather than coaching. Interventions some time before the consultation did not alter consultation time.

The interventions seem to help patients ask more questions in consultations, but do not have other clear benefits. Doctors and nurses need to continue to try to help their patients ask questions in consultations and question prompt sheets or coaching may help in some circumstances.

Background

Patients (or healthcare consumers) often report that they want more information from clinicians (doctors and nurses) or that the information they do receive does not address their particular needs (Boberg 2003; Boreham 1978; Jenkins 2001). External observation confirms that the amount of information usually given to patients is small (Ford 1995; Maguire 1996; Svarstad 1974; Waitzkin 1984). Patients have varying information needs and clinicians need to tailor the information given accordingly (Leydon 2000; Meredith 1996). Providing information is important because it is a determinant of patient satisfaction, compliance, recall and understanding (Deyo 1986; Faden 1981; Hall 1988). It has also been associated with symptom resolution, reduced emotional distress, physiological status, use of analgesia, length of hospital stay and quality of life (Egbert 1964; Fallowfield 1994; Kaplan 1989; Roter 1995; Stewart 1995). Failure to give information, or the provision of unwanted information, can reduce the benefits of the consultation or can cause negative outcomes (Fallowfield 1999).

Information giving may be poor for a number of reasons. Clinicians may underestimate or undervalue the information needs of patients (Beisecker 1990; Faden 1981; Kindelan 1987; Tuckett 1985; Waitzkin 1984). Alternatively, they may overestimate the amount of information they give (Makoul 1995), lack the skills to give information (Jenkins 2002; Maguire 1986; Tuckett 1985) or use technical language and jargon (Korsch 1968). Furthermore, patients may feel intimidated or otherwise unable to voice their needs (Leydon 2000; McKenzie 2000; Stimson 1975; Tuckett 1985). This may be particularly relevant for patients with serious or life‐threatening diseases to whom clinicians may be reluctant to give information, believing it to be harmful (Fleissig 2000; Jefford 2002; Silverman 2005).

Improving clinicians' provision of information to patients presents challenges. Clinicians' skills may not improve even with specific training, which can be resource intensive and in which clinicians may be reluctant to participate (Fallowfield 2002; Kramer 2004). As an adjunct or alternative, interventions directed at helping patients express their information needs and address them in consultations have been evaluated. Various methods has been identified to encourage patients to ask questions, including coaching sessions before consultations (Greenfield 1988), videos (Lewis 1991), and written materials (for example, question prompt sheets) (Butow 1994). Various outcomes have been studied with some positive results. For example, Greenfield and colleagues (Greenfield 1988) found that a 20‐minute patient coaching session delivered before consultations to improve participation and information‐seeking skills in the consultation led to patients reporting improved physical outcomes. Other positive results including increased patient satisfaction and improved psychological adjustment have been found in studies in both primary care and hospital settings, among patients with various conditions (Butow 1994; Kaplan 1989; Rost 1991; Roter 1977).

Despite these apparent benefits, we know of no routine implementation of strategies to help patients address their information needs. Given the large number of patients who consult clinicians in hospital and primary care settings, this suggests that there is either lack of knowledge of the potential benefits, doubts about the consistency of the evidence, or concerns about unforeseen negative outcomes. In these circumstances a systematic review is required to evaluate the current evidence, identify further research needs, and inform decisions about implementation of the interventions.

This review complements a number of other Cochrane reviews; for example, the review by Wetzels et al (Wetzels 2007) which focuses on interventions to involve older patients in primary care, the review by Scott et al (Scott 2003) on the provision of tape recordings or summaries of consultations, and the review by Lewin et al (Lewin 2001) of interventions aimed at providers to promote patient‐centred care.

Objectives

To assess the effects on patients, clinicians and the healthcare system of interventions which are delivered before consultations, and which have been designed to help patients (and/or their representatives) address their information needs within consultations.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Excluded: controlled (non‐randomised) clinical trials (CCTs), prospective cohort studies (including controlled before‐and‐after studies and interrupted time series), studies without comparison groups, individual case reports.

In the protocol for this review we planned to include RCTs, CCTs and prospective cohort studies including controlled before‐and‐after studies and interrupted time series. This inclusive approach was designed to avoid missing important data in a rapidly expanding field, preliminary exploration of which suggested that few RCTs existed. However, we found 33 RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria for this review. Therefore we were able to raise the threshold for study design inclusion to include RCTs only, as these provide a more robust level of evidence than other study designs.

Types of participants

Patients and/or their representatives (or carers) of all ages before 'one‐to‐one' consultations with doctors or nurses in healthcare settings.

Excluded: Individuals or groups attending activities such as health promotion clinics (for example, antenatal classes) or in‐patients for whom there were not specific subsequent identifiable consultations. Individuals consulting other healthcare professionals.

Types of interventions

Interventions directed at individual patients, representatives or carers before a consultation and intended to help them address their information needs in the consultation.

Evidence of this intention was that patients were encouraged to:

consider and/or express their information needs by identifying and asking questions;

consider and/or express the amount and content of information they require;

consider how they might express their information needs in the consultation;

consider how they might overcome barriers to communication within the consultation; and/or

clarify and/or check their understanding of information provided in the consultation.

We excluded:

interventions provided to patients during their consultations, for example information leaflets about illnesses or diseases, and decision aids;

symptom diaries, unless the material appeared to encourage identification of patient information needs as well as provision of information;

interventions describing treatment options and effects of treatments;

interventions intended to provide patients with more information about their symptoms or illness unless this was intended to help the patient identify further information needs;

interventions intended to improve communication other than addressing information needs;

training and other interventions solely targeted at clinicians to encourage them to change their consulting behaviour, for example by providing more information to patients;

interventions intended to help patients address information needs outside consultations.

Types of outcome measures

We categorised outcomes into three major domains:

the consultation process;

the consultation outcome; and

service outcomes.

This allowed us to distinguish between measures of change in the consultation process (for example, patient question asking) and measures of consultation outcome (for example, psychological health after the consultation).

Within the second domain of consultation outcomes, we used two sub‐domains, as we considered primary outcomes to be measures of patient health (2a) and secondary outcomes to be measures which reflected the care the patient had received, or their experience or perception of it (such as patient satisfaction) (2b).

We considered service outcomes (domain 3), that is the effects of interventions on clinicians and the service as a whole, since benefits to patients must be weighed against other effects.

We thus intended to identify a range of outcomes which would provide data about the consultation process and outcomes for patients and service providers, and which enabled us to summarise data across studies.

We examined potentially important effect modifiers on the outcomes measured, looking in particular (where data were available) for the effects of: type of intervention, timing of intervention, and whether the interventions also included training for clinicians.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We used an explicit search strategy agreed with the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group to search the following databases from their start date:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library, issue 3, 2006);

MEDLINE (Ovid) (1966 to September 2006);

EMBASE (1980 to September 2006);

PsycINFO (1985 to September 2006);

ERIC (1966 to September 2006);

CINAHL (1982 to September 2006).

The search strategy was adapted for the requirements of each database. We conducted the searches in English, but considered citations identified in any language. We initially ran the searches in January 2004 and updated them in September 2006.

The search strategy for MEDLINE (Ovid) is presented in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We inspected the reference lists of possibly‐included studies to identify further potentially‐relevant citations. In addition, in an attempt to identify unpublished studies, we wrote to authors of included studies asking for information about similar studies not identified by our search and selection process. We also reviewed in detail the reference lists of five reviews on related topics (Anderson 1991; Cegala 2003, Gaston 2005; Harrington 2004; Jahad 1995).

Finally, since it was the journal in which the largest proportion of possibly‐included studies were published, we also handsearched the contents of Patient Education and Counseling from 1986 to September 2006 (including those articles listed as being 'in press').

Data collection and analysis

Consumer involvement

Before conducting the review, the protocol was submitted to two groups of consumers (University of Wales College of Medicine Simulated Patients and Cochrane Consumer and Communication Review Group consumer representatives) and other peer‐reviewers, and modified in the light of feedback.

Selection of studies

For the electronic searches, two researchers (PD and HP, DO or NC) independently reviewed each title and, where electronically available, the abstract. We categorised citations into three groups: 1) background literature; 2) possibly included studies; and 3) excluded (clearly irrelevant) studies.

Two authors (PK and HP or DO) reviewed independently the full text of the possibly‐included studies, and determined whether they met the review's inclusion criteria (stated previously). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, or by seeking a third opinion (AE).

Two members of the research team (PK and RR or NC) independently extracted the data from each study. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. We attempted to contact all authors to establish whether further data from studies were available, and to clarify any difficulties with interpretation or data extraction. When available, this additional data has been presented. We used piloted, specially‐developed data extraction forms. Fields included: author; year; country; setting (primary/secondary care); description of intervention; patient groups; clinician groups; disease area; inclusion/exclusion criteria; numbers eligible/approached/recruited/followed up; randomisation; outcomes; blinding of assessor; duration of follow up; results and comments. Where studies used combined interventions (for example, written materials and coaching) we used data on the effects of the combined intervention for the principal outcomes. However, we used the effects of separate elements of the intervention in secondary analyses (for example, comparing the effects of written materials to coaching).

Avoidance of bias/criteria for assessing quality

In order to make an evaluation of study quality we assessed studies for: (1) selection bias, (2) performance bias, (3) attrition bias, and (4) detection bias (Clarke 2003). In addition, we gathered data on the adequacy of randomisation with particular attention to concealment of allocation. We reported allocation concealment in the Characteristics of included studies table using the following classification scheme: (A) Adequate, (B) Unclear, (C) Inadequate, or (D) Not used. We used intention‐to‐treat analyses if available.

Methods for combining studies

We conducted a narrative synthesis of the included trials, presenting their characteristics and results, focusing in particular on the effects of similar interventions. Since the studies were reasonably similar in terms of settings, inclusion criteria and interventions, we pooled data across studies and conducted meta‐analyses where appropriate data were available. We conducted planned subgroup analyses to examine the possible effects of the type of intervention (written materials compared to coaching), and post‐hoc analyses to examine the timing of the interventions (some time before the consultation compared to immediately before the consultation) and whether or not the clinicians in the study had received additional training as to how to deal with patients' questions. These were performed to provide further evidence to inform the implementation of future interventions. In the analyses we used the data reporting the effects of appropriate components of the intervention.

We used statistical tests for heterogeneity between studies. To estimate effects we used fixed‐effect models where there was homogeneity, and random‐effects models where heterogeneity existed. For those outcomes which were measured using the same methods and units we used the weighted mean difference (WMD) method (Higgins 2006). For outcomes measured using differing methods, (for example, satisfaction), or where there was likely to be variation due to the context (for example, consultation length, or questions asked) we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) method (Higgins 2006).

Results

Description of studies

The search strategy generated 4876 citations. From these, the review authors identified 71 citations for possible inclusion. Eleven citations were added from the review by Cegala (Cegala 2003) and eleven from additional reading and citations of reviewed articles. In addition, as the review was proceeding, three further citations were added from the review by Harrington (Harrington 2004), four from handsearching Patient Education and Counseling, and six from further reading. We then assessed this final set of 106 citations. Of this set we excluded 71 papers. We included 33 trials described in 35 papers. The total number of patients randomised and entered into the studies was 8244. Three of the included studies were reported in more than one paper (Cegala 2000; McCann 1996; Roter 1977); also, two papers (Sander 1996; Thompson 1990) each reported two trials, and are thus labelled Sander 1996a and Sander 1996b; Thompson 1990a and Thompson 1990b.

The main characteristics of the 33 studies, including participants, interventions and outcomes measured, are described in the table 'Characteristics of included studies' . All were published in English. Seventeen studies were from the USA, seven from the UK, four from Australia, two from the Netherlands, two from Canada and one from Indonesia. There appeared to be increasing interest in the subject over time, with one study published in the 1970s, 3 published in the 1980s, 15 in the 1990s and 14 after 1999. The studies varied in size, with 2 studies involving less than 50 patients, 6 studies involving between 50 and 100 patients, 15 involving 100 to 200 patients and 10 involving over 200 patients. In addition, the number of clinicians varied, with 10 studies involving less than 5 clinicians, 4 studies involving between 5 and 9 clinicians, and 10 studies with 10 or more clinicians. In nine studies it was unclear how many clinicians were involved.

The patient population varied. Thirteen studies reported on primary care or family medicine patients, nine reported on patients with cancer, two on patients with diabetes, two on patients with cardiac problems, two on patients with obstetric or gynaecological problems, one on mixed outpatients, one on women attending family planning clinics, one on women attending a well baby clinic, one on children attending a paediatric clinic and one on patients with peptic ulcers. In the study conducted in a paediatric setting, both children and their parents received interventions (Lewis 1991). In one study, some of the patients were in‐patients, although they subsequently had an additional outpatient consultation (Butow 1994). Thirty studies reported on patients consulting physicians, two on patients consulting either physicians or nurses, and one on family planning care providers.

Interventions

The studies assessed a range of interventions, with some studies using multiple or combined interventions of varying complexity. Additional Table 1 provides further information on the interventions, with studies grouped by time of implementation of the intervention, and by level of complexity (single / combined interventions).

1. Details of interventions.

| Study name | Setting | Intervention |

| IMMEDIATELY BEFORE CONSULTATION (WHILE PATIENT WAITING TO SEE CLINICIAN) | ||

| ‐ Written materials | ||

| Brown 2001 | Oncology clinics, Australia | Question checklist endorsing question asking as a useful activity and welcomed by the doctor. Contained checklist of questions and participants circled questions they wanted to ask. Clinicians actively endorsed the checklist for a sample of patients. |

| Bruera 2003 | Oncology clinic, USA | Question checklist containing 22 questions with space for additional questions. |

| Butow 1994 | Oncology clinic, Australia | Question checklist designed to encourage question asking in the consultation. |

| Frederickson 1995 | General practice, UK | Leaflet (single page) encouraging patients to 'stop, think and tell the doctor about their problems and worries'. |

| Hornberger 1997 | Primary care clinics, USA | Question checklist with 25 items covering five categories of concerns. Patients marked whether they wanted to discuss the concern then identified three main concerns. List attached to medical records so physician could address during consultation. |

| Little 2004 | General practices, UK | Leaflet asking patients to list issues they wanted to raise and explaining that the doctor wanted them to be able to ask questions. |

| Maly 1999 | Family medicine clinic, USA | Question checklist in which patients asked to record two main questions they wanted to ask. Also given copy of previous entry in medical records. |

| McCann 1996 | General practice, UK | Question checklist ('Speak for yourself' leaflet) with space to write down ideas and encouraging patients to ask questions. |

| Middleton 2006 | General practices, UK | Patient agenda form asking patients to identify questions. |

| Sander 1996a | Family medicine clinic, USA | Two intervention groups ‐ each given different versions of 'health concerns card' focusing on health maintenance and designed to stimulate patient information seeking. |

| Tabak 1988 | Family medicine clinic, USA | Question checklist designed to encourage question asking in the consultation. |

| Thompson 1990a | Obstetric and gynaecology clinic, USA | Question checklist with list of possible concerns and instructions to write down at least three questions. |

| Thompson 1990b | Obstetric and gynaecology clinic, USA | Two intervention groups ‐ Group 1: Question checklist with list of possible concerns and instructions to write down at least three questions. Group 2: Written message from physician encouraging patients to ask questions but not write them down. |

| ‐ Coaching | ||

| Finney 1990 | Well baby clinics, USA | 'Brief prompting strategy' to help patients identify questions of interest to them. |

| Greenfield 1985 | Outpatient clinic, USA | Twenty minutes with three components: a) review of records, b) review of a treatment algorithm, c) behaviour change strategy to increase involvement in consultation. |

| Greenfield 1988 | Diabetic clinic, USA | As in Greenfield 1985 but delivered twice, before initial and follow up consultations (before outcomes measured) to increase the involvement of patients in medical decision making and to improve patient information seeking. |

| Roter 1977 | Family medicine clinic, USA | Ten minutes with health educator working through a question asking protocol to identify and write down patients' questions. Also encouragement to ask questions and patients took list of questions into consultation. |

| Sander 1996b | Family medicine clinic, USA | Two intervention groups ‐ each given different versions of 5 minutes of coaching with encouragement to identify and/or write down questions. |

| ‐ Combined interventions | ||

| ‐‐ Written materials and coaching | ||

| Brown 1999 | Oncology clinic, Australia | Two intervention groups ‐ Group 1: Question checklist containing 17 questions. Group 2: Question checklist with brief coaching from research psychologist covering question generation, exploration of benefits of and barriers to asking questions and rehearsal. Clinicians 'endorsed' the checklist and elicited and answered questions according to a standard protocol. |

| Davison 1997 | Oncology clinic, Canada | Combined intervention ‐ Question checklist completed by patient and then reviewed with researcher who provided coaching using an information pack to identify additional questions to ask. Patients encouraged to ask questions and ask for audiotape of consultation. |

| Kidd 2004 | Diabetic clinic, UK | Three intervention groups ‐ Group 1: Written message encouraging patients to ask questions. Group 2: Coaching for five minutes with researcher including identifying at least three questions to ask. Group 3: Coaching and rehearsal: five minutes with researcher identifying at least three questions to ask and also rehearsal of asking. |

| Kim 2003 | Family planning clinics, Indonesia | Combined intervention ‐ Question checklist completed by patient and 'Smart patient' coaching including how to ask questions and identification of questions to ask. |

| Oliver 2001 | Oncology clinics, USA | Combined intervention ‐ Question checklist in form of booklet encouraging question asking with space to write down questions combined with coaching: to teach patients practical pain management techniques and to empower patients to participate actively in their own care. |

| ‐‐ Computer and coaching | ||

| Davison 2002 | Oncology clinic, Canada | Combined intervention ‐ Computer programme to identify control preferences and information needs followed by coaching from nurses as to how to use computer printouts in the consultation to gather information. |

| ‐‐ Video and coaching | ||

| Lewis 1991 | Paediatric clinic, USA | Combined intervention ‐ three facets: Children shown 10 minute video with workbook to write down questions then coached to practice questions with research assistant. Parents shown 10 minute video. Physicians shown 15 minute video as part of one hour training session with boosters at 3, 8 and 15 months. Four common themes to videos ‐ 1) opportunity to think about the goals of the medical visit; 2) the long term goal of medical care is to encourage the child to be an active participant in the consultation; 3) modelling of skills to achieve this; 4) provision of evidence to support this. |

| SOME TIME BEFORE THE DAY OF THE CONSULTATION | ||

| ‐ Written materials | ||

| Bolman 2005 | Cardiology clinics, The Netherlands | Question checklist containing 49 questions on 10 different issues (as Martinali 2001). Mailed to patient one week before each of three linked consultations. |

| Butow 2004 | Oncology clinic, Australia | Question checklist ‐ 'Cancer consultation package' with three components: 1) 'How treatment decisions are made' booklet describing principles of evidence‐based medicine; 2) 'Your rights and responsibilities as a patient' brochure describing patients' legal rights; 3) question prompt sheet endorsing question asking with 19 suggested questions and recommendation to prepare list of questions (as in Butow 1994, Brown 1999, Brown 2001). Mailed to patients at least 2 days before consultation. |

| Fleissig 1999 | Outpatient clinic, UK | Question checklist in form of 'help card' and letter. The help card suggested general questions with space for the patient to write down questions covering the patient's condition, tests, treatment and other concerns. Mailed to patients two weeks before hospital visit. |

| Martinali 2001 | Cardiology clinics, The Netherlands | Question checklist with 49 items 'frequently asked questions' on 10 different issues. Also information booklet about heart disease. Mailed to patients one week before consultation. |

| Wilkinson 2002 | Family medicine clinics, USA | Question checklist in format of guidebook 'How to be prepared' with aim of improving patients' perceptions of primary care visit effectiveness with space for patient to write down questions. Mailed to patient prior to visit. |

| ‐ Combined interventions | ||

| ‐‐ Written materials and coaching | ||

| Tennstedt 2000 | Family medicine clinic, USA | Combined intervention ‐ Question checklist in format of booklet for patient to record and prioritise reasons for visit and to record questions to ask. Coaching: two hour group programme including modelling of both desirable and undesirable behaviours. Up to three months before consultation. |

| ‐‐ Written materials and information | ||

| Cegala 2000 | Primary care clinics, USA | Two intervention groups ‐ Group 1: Question checklist in format of 14 page workbook encouraging patients to list topics they wanted to discuss with additional sections on information seeking and verifying. All sections contained example questions. Mailed to patients 2 to 4 days before consultation and briefly gone over on arrival at clinic. Group 2: Brief summary of points in training booklet and patients encouraged verbally to organise thoughts and ask questions. On arrival at clinic. |

| AUDIOTAPE OF PREVIOUS CONSULTATION | ||

| Ford 1995 | Oncology clinic, UK | Audiotape of initial consultation, patient encouraged to listen to it at home before second consultation which was a month later. |

With regard to the interventions targeted at patients, 26 studies reported on single interventions and 7 reported on multiple interventions.

Studies assessing single interventions for patients

Of the single interventions, 20 had only one component and 6 had multiple components. The single component interventions were:

written materials in 15 studies (Bolman 2005; Brown 2001; Bruera 2003; Butow 1994; Butow 2004; Fleissig 1999; Frederickson 1995; Hornberger 1997; Maly 1999; Martinali 2001; McCann 1996; Middleton 2006; Tabak 1988; Thompson 1990a; Wilkinson 2002);

coaching in four studies (Finney 1990; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Roter 1977); and

an audiotape of the previous consultation in one study (Ford 1995).

The multiple component (single) interventions were:

coaching and written materials in four studies (Davison 1997; Kim 2003; Oliver 2001; Tennstedt 2000);

coaching and a computer programme in one study (Davison 2002); and

coaching, written materials and a video in one study (Lewis 1991).

Studies assessing multiple interventions for patients

Of the seven studies assessing multiple interventions:

one study compared written materials with written materials and coaching (Brown 1999);

one study compared written materials with brief advice on question asking (Cegala 2000);

one study compared a brief message about question asking with an interview to identify questions and a third intervention of coaching (Kidd 2004);

two studies compared two different forms of written materials (Little 2004; Sander 1996a);

one study compared two different forms of coaching (Sander 1996b); and

one study compared written materials with a brief message about question asking (Thompson 1990b).

All seven studies had an additional group who received usual care or a dummy intervention.

Intervention timing

In 26 of the 33 studies, the interventions were delivered to the patients in the waiting room immediately before their consultation. In six studies the intervention was delivered some time before the consultation ‐ by post in five studies (Bolman 2005; Butow 2004; Fleissig 1999; Martinali 2001; Wilkinson 2002) and by community‐based training in one study (Tennstedt 2000). In one study one group of patients received the intervention (a booklet to help them identify and ask questions) by post a few days before the consultation, and a second group of patients received a different intervention (brief advice about question asking) at the clinic on the day of the consultation (Cegala 2000).

Comparisons

In 20 studies, the control patients received a dummy intervention intended to be similar in length to that being studied, and in 11 studies they received only usual care. In one study (Kidd 2004) there were two control groups with one receiving a dummy intervention and the other usual care. Little 2004 used a 2 x 2 design testing two interventions with one group receiving neither and acting as a control. In three studies the interventions were repeated at subsequent consultations to the same patients (Bolman 2005; Greenfield 1988; Maly 1999).

Interventions for clinicians

In five studies (Bolman 2005; Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Lewis 1991; Middleton 2006) the clinicians also received an intervention intended to improve their ability to elicit questions from the patient and/or to enable them to answer patients' questions more effectively. In Bolman 2005 all clinicians were trained before the patient interventions were implemented. In Lewis 1991 only those clinicians who were seeing patients who received the intervention received training. Brown 1999 trained clinicians to address the patients' list of questions (if they had them). In Brown 2001 clinicians were randomised to address or to not address the question lists of patients who had received the intervention (that is, half of the patients who received a prompt sheet saw a doctor who actively endorsed the sheet and systematically reviewed each question). Finally, Middleton 2006 used a 2 x 2 design, with patients and clinicians being randomised to interventions.

Outcomes

We extracted data on all reported outcomes (See additional Table 2; and Table 3).

2. Main outcomes for each study.

| Study name | Intervention | Numbers randomised | Question asking | Anxiety | Patient satisfaction | Knowledge | Consultation length | Other outcomes |

| Bolman 2005 | Question checklist ‐ before each of three visits | 153 | Reduced (before first visit) | No change | Reduced (before first and third visits) | Reduced (first visit), increased (third visit) | Information exchange ‐ no change; Usefulness of intervention (Intervention group only) positive. | |

| Brown 1999 | Question checklist; coaching | 60 | Increased | No change | No change | Psychological adjustment no change; Types of question asked about prognosis increased | ||

| Brown 2001 | Question checklist; doctor training | 318 | No change | Increased | No change | No change | Recall no change; Types of question asked about prognosis increased | |

| Bruera 2003 | Question checklist | 60 | No change | No change | No change | Clinician satisfaction no change; Types of questions asked no change; Helpfulness of interventions (both groups) increased; Satisfaction with communication no change; Clinician estimate of consultation length no change. | ||

| Butow 1994 | Question checklist | 142 | No change | No change | No change | Psychological adjustment no change; Types of question asked about prognosis increased; Recall no change | ||

| Butow 2004 | Question checklist | 164 | Increased | Increased (Before consultations); No change (after consultation and at 1 month) | No change (immediately and at 1 month) | No change | Participation increased; Usefulness of intervention positive; Depression (before and after consultation) no change; Involvement in decision making no change; Satisfaction with treatment decision no change | |

| Cegala 2000 | Question checklist; brief information and coaching | 150 | Increased (Checklist only) | Participation increased; Compliance increased | ||||

| Davison 1997 | Question checklist and coaching | 60 | No change | Depression no change; Preferences for control over treatment decisions increased | ||||

| Davison 2002 | Computer programme and coaching | 749 | No change | Role preferences no change | ||||

| Finney 1990 | Coaching | 32 | No change | No change | ||||

| Fleissig 1999 | Question checklist | 1208 | Increased | Participation increased; Prepared questions raised no change | ||||

| Ford 1995 | Audiotape of previous consultation | 117 | No change | No change (before consultation) | No change | Participation increased; Depression no change (before consultation) | ||

| Frederickson 1995 | Question checklist | 80 | Doctor's assessment of quality of consultation increased | |||||

| Greenfield 1985 | Coaching | 45 | No change | No change | Reduced | No change | Participation increased; Role and physical limitation reduced; Pain no change; Preference for active involvement increased | |

| Greenfield 1988 | Coaching (delivered twice) | 73 | No change | No change | No change | No change | Participation increased; Functional limitations reduced; Health status increased; Days lost from work reduced; HbA1c reduced | |

| Hornberger 1997 | Question checklist | 101 | Reduced | No change | Increased | Depression no change; Health status no change; Services provided no change; Clinician satisfaction no change | ||

| Kidd 2004 | Written message; coaching; coaching and rehearsal | 202 | No change | No change (immediately); increased (three months) | Patient self efficacy increased; HbA1c no change | |||

| Kim 2003 | Question checklist and coaching | 768 | Increased | No change | Participation increased; Patient assessment of communication no change; Discontinuation of contraception no change | |||

| Lewis 1991 | Videotape for child, parent and clinician | 141 | Child anxiety no change | Child satisfaction increased; parent satisfaction no change | Participation increased; General recall no change; Medication recall increased; Child preference for active health role increased; Physician satisfaction no change | |||

| Little 2004 | Question checklist | 636 | No change | Increased | No change | Depression no change; Enablement no change; Resolution of symptoms no change; Number of investigations increased | ||

| Maly 1999 | Question checklist (delivered twice) | 265 | Increased | No change | Physical function increased; Global health no change; Disability days no change; Adherence no change; Desire to see medical records no change; Propensity for medical information increased. | |||

| Martinali 2001 | Question checklist | 142 | Reduced (before consultation) | No change | No change | No change | Participation no change; Adequacy of information exchange no change. | |

| McCann 1996 | Question checklist | 120 | No change | No change | Increased | Physical function no change; Mental health no change; Clinician evaluation no change; Consultations in next 12 months no change. | ||

| Middleton 2006 | Question prompt sheet | 955 | No change except for depth of doctor‐patient relationship (increased) | Increased | ||||

| Oliver 2001 | Question checklist and coaching | 87 | No change | No change | Pain reduced; Pain‐related impairment no change; Pain frequency no change; Analgesic adherence no change. | |||

| Roter 1977 | Coaching | 200 | Increased | Increased | No change | Participation no change; Patient expression of emotions increased; Patient internality of locus of control increased; Adherence to appointments increased. | ||

| Sander 1996a | Question checklist | 129 | Participation no change; Patient requests for information increased; Likelihood of using information from consultation no change; Recall no change. | |||||

| Sander 1996b | Coaching | 163 | Participation no change; Patient requests for information increased; Likelihood of using information from consultation no change; Recall no change. | |||||

| Tabak 1988 | Question checklist | 101 | No change | |||||

| Tennstedt 2000 | Coaching | 355 | No change except Interpersonal satisfaction increased | Participation no change | ||||

| Thompson 1990a | Question checklist | 66 | Increased | Reduced | No change | No change | Clinician satisfaction no change | |

| Thompson 1990b | Checklist of information to obtain; message encouraging questions | 105 | No change | No change | Increased | Extent to which questions answered increased; Sense of control increased; Recall no change. | ||

| Wilkinson 2002 | Question checklist | 278 | Evaluation of visit no change; health record review no change apart from prostate screening (increased) |

3. Summary of outcomes sought.

| Outcomes sought | No. of studies |

| 1) CONSULTATION PROCESS | |

| Patients' perceptions of communication, including usefulness of information provision | 7 |

| Information seeking and participation | 14 |

| Question asking | 17 |

| Provision of information | 2 |

| Verifying information | 0 |

| Types of questions asked | 4 |

| 2) CONSULTATION OUTCOMES | |

| 2a) Patient health outcomes | |

| Symptom control | 3 |

| Performance status (ability to undertake activities of daily living) | 5 |

| Pysiological measures of disease control | 2 |

| Physical health | 4 |

| Psychological health | 21 (including 12 studies measuring anxiety) |

| 2b) Patient care outcomes | |

| i) Patient knowledge | |

| Understanding/Knowledge acquisition | 5 |

| Retention of information, recall of information | 6 |

| Satisfaction with knowledge provision | 0 |

| ii) Evaluation of care | |

| Perception of care | 1 |

| Patient satisfaction | 23 |

| Perception of intervention | 3 |

| iii) Self‐efficacy | |

| Empowerment | 2 |

| Enablement | 1 |

| Confidence | 0 |

| Ability to cope | 0 |

| Sense of control | 5 |

| iv) Health behaviour | |

| Adherence (compliance) | 5 |

| Lifestyle or behavioural outcomes | 0 |

| Use of health services | 0 |

| Use of intervention | 1 |

| v) Treatment outcomes | |

| Adverse outcomes | 0 |

| 3) SERVICE OUTCOMES | |

| Provision of information | 0 |

| Clinician satisfaction | 3 |

| Clinician perception of intervention | 0 |

| Consultation length | 17 |

| Service utilisation | 4 |

Our primary focus is on seven important and commonly‐reported outcomes (question asking; patient participation; anxiety; patient satisfaction; knowledge; consultation length and clinician satisfaction) which are categorised into the outcome domains specified earlier, as follows: 1. Consultation process: question asking; patient participation; 2. Consultation outcomes: a) Patient health outcomes: anxiety (primary outcome); b) Patient care outcomes: patient satisfaction, knowledge (secondary outcomes); and 3. Service outcomes: consultation length, clinician satisfaction.

It should be noted that consultation length could be considered both to be a measure of consultation process and an outcome. However, for the purposes of this review, we chose to categorise it as an outcome of particular relevance to clinicians and the service itself.

We conducted meta‐analyses on five outcomes: question asking, anxiety, patient satisfaction, knowledge and consultation length. We did not meta‐analyse clinician satisfaction, since different methods were used to measure it in the three studies in which it was reported (Bruera 2003; Hornberger 1997; Lewis 1991). We did not meta‐analyse patient participation because there was no consistency of measurement in patient questionnaires, and because some studies assessed it from patient questionnaires while others used consultation audiotapes.

Consistent methods of data collection were used across studies (see table Characteristics of included studies). Seventeen studies audiotaped or videotaped patient consultations to measure features of the conversation between patient and clinician (most commonly question asking and consultation length). Twenty six studies used exit questionnaires given to the patients immediately after the consultation to be completed on the premises or to be returned by post, while 14 studies used postal questionnaires or phone interviews to follow up patients days or weeks after their consultations.

1. Consultation process

Question asking was measured in 17 studies (Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Bruera 2003; Butow 1994; Butow 2004; Cegala 2000; Fleissig 1999; Ford 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Kidd 2004; Kim 2003; McCann 1996; Roter 1977; Tabak 1988; Thompson 1990a; Thompson 1990b) using direct counts from an audiotape.

Participation was measured in 14 studies (Bolman 2005; Butow 2004; Cegala 2000; Fleissig 1999; Ford 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Kim 2003; Lewis 1991; Martinali 2001; Roter 1977; Sander 1996a; Sander 1996b; Tennstedt 2000). Eight studies measured it from audiotapes of consultations (Butow 2004; Cegala 2000; Ford 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Kim 2003; Lewis 1991; Roter 1977) and six used a range of patient questionnaires (Bolman 2005; Fleissig 1999; Martinali 2001; Sander 1996a; Sander 1996b; Tennstedt 2000).

2. Consultation outcomes

a) Patient health outcomes

Patient anxiety was measured in 12 studies, 8 of which used the Spielberger questionnaire (Bolman 2005; Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Butow 2004; Davison 1997; Martinali 2001; Thompson 1990a; Thompson 1990b). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Questionnaire was used in three studies (Ford 1995; Hornberger 1997; Little 2004), while Lewis 1991 used the Children's Picture Test of Anxiety to measured anxiety in children . In seven studies, anxiety was measured before the index consultation either as a baseline measure or an assessment of the impact of the intervention (Bolman 2005; Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Butow 2004; Davison 1997; Ford 1995; Martinali 2001). Anxiety was measured after the consultation in 10 studies (Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Butow 2004; Davison 1997; Ford 1995; Hornberger 1997; Lewis 1991; Little 2004; Thompson 1990a; Thompson 1990b).

b) Patient care outcomes

Patient satisfaction was measured in 23 studies. Four studies used questionnaires based on that developed by Roter (Roter 1977): Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Butow 1994; Butow 2004. Another four studies used methods based on the Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale (Finney 1990; Lewis 1991; Little 2004; McCann 1996). The remaining 15 studies used a variety of methods (Bolman 2005; Bruera 2003; Davison 2002; Fleissig 1999; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Hornberger 1997; Kidd 2004; Maly 1999; Martinali 2001; Middleton 2006; Roter 1977; Tennstedt 2000; Thompson 1990a; Thompson 1990b).

Patient knowledge was measured in five studies. Two studies used the same questionnaire for patients with heart problems (Bolman 2005; Martinali 2001), and the remaining three studies each used different instruments (Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Oliver 2001).

3. Service outcomes

Consultation length was measured in 17 studies; in 11 directly from audiotape (Brown 2001; Bruera 2003; Butow 1994; Butow 2004; Ford 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Hornberger 1997; Kim 2003; McCann 1996; Roter 1977), and in 6 by other methods (Bolman 2005; Little 2004; Maly 1999; Martinali 2001; Middleton 2006; Thompson 1990a). The unit of measurement for consultation length in all studies was minutes.

As stated earlier, clinician satisfaction was measured in three studies using various methods (Bruera 2003; Hornberger 1997; Lewis 1991).

Risk of bias in included studies

The studies were of variable quality, with more rigorous methods tending to be used in more recently published papers.

Study design

All of the included studies were described as randomised controlled trials. However, methods of randomisation were described only briefly. In 27 studies the information was very brief, using terms such as 'patients were randomly allocated' or 'patients were randomly given an envelope' (Bolman 2005; Brown 1999; Bruera 2003; Butow 1994; Butow 2004; Cegala 2000; Davison 1997; Davison 2002; Finney 1990; Frederickson 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Hornberger 1997; Kidd 2004; Kim 2003; Lewis 1991; Martinali 2001; McCann 1996; Oliver 2001; Roter 1977; Sander 1996a; Sander 1996b; Tabak 1988; Tennstedt 2000; Thompson 1990a; Thompson 1990b; Wilkinson 2002). In two studies computers were used to generate random numbers (Brown 2001; Fleissig 1999); two studies used random number tables (Little 2004; Middleton 2006); one study used a remote trials co‐ordination centre (Ford 1995); and one study used a card shuffling technique (Maly 1999).

In 30 studies, randomisation was by patient. In two studies, randomisation was by clinician (Hornberger 1997; Lewis 1991) and in one by site of delivery of a community‐based intervention (Tennstedt 2000). In these three latter studies no attempt was made to account for the effects of clustering, which can lead to overestimation of the significance of the intervention. To explore this we conducted post‐hoc meta‐analyses with and without data from these studies and have described the results.

Only six studies provided sample size calculations (Bolman 2005; Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Kidd 2004; Little 2004; Middleton 2006).

Method of allocation concealment

Only four trials provided sufficient evidence of adequate concealment of allocation (Ford 1995; Little 2004; Middleton 2006; Tabak 1988). The methods used included an external trials co‐ordination centre (Ford 1995), numbered, pre‐prepared, sealed, opaque envelopes (Little 2004), and randomisation of appointment slots with blinding of receptionists (Middleton 2006). Twenty four studies were judged to be unclear about the method of allocation concealment, usually because insufficient information was provided. There was insufficient blinding of allocation in five studies (Cegala 2000; Frederickson 1995; Maly 1999; Sander 1996b; Tennstedt 2000).

Protection against contamination

In the two studies which were randomised by clinician (Hornberger 1997; Lewis 1991), no particular steps seem to have been taken to prevent contamination between clinicians in the different study arms. In addition, in Brown 2001 in which clinicians were randomly selected for training to address the intervention, there was a risk of contamination between trained and non‐trained clinicians and also the possibility that trained clinicians might use their training with patients who had not received the intervention (the trained clinicians were required to actively endorse the list of questions for those patients who had received a prompt sheet). Evidence was provided that the clinicians did vary their consulting style appropriately and did not overly facilitate questions with patients who had not received the prompt sheet.

Blinding of outcome assessors

In the 17 studies that used audio or videotapes to gather data about the consultation, 7 studies (Bruera 2003; Cegala 2000; Finney 1990; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Kidd 2004; Tabak 1988) reported that those who assessed the tape were blind to patients' group allocation. In addition, 8 studies (Brown 2001; Butow 2004; Cegala 2000; Ford 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Hornberger 1997; Kidd 2004) reported reliability checks on the gathering of this data, with double rating of a sample or of all tapes. Most studies were unclear about the blinding of assessors for other key outcomes. However as most studies used patient‐reported measures (questionnaires), there may be low risk of ascertainment bias.

Use of intention‐to‐treat analyses

Only two studies stated they used intention‐to‐treat analyses (Brown 2001; Little 2004).

Effects of interventions

Additional Table 2 'Main outcomes for each study' shows the effects of interventions on the outcomes measured in each study, classified as reduced, no change, or increased. These descriptors reflect statistical significance; that is, a statistically significant reduction in anxiety is labelled 'reduced' while a statistically insignificant reduction is labelled 'no change'

Additional Table 3 'Summary of outcomes sought' outlines the outcomes we looked for and the number of studies which reported them. We sought but did not find data on outcomes including: patients' satisfaction with knowledge provision, confidence and ability to cope, lifestyle or behavioural outcomes, use of health services, provision of information, clinicians' perceptions of the intervention, and, importantly, harms.

The most commonly‐used measures of consultation process were question asking and patient participation. Primary consultation outcome measures ‐ patient health outcomes ‐ were measured rarely apart from psychological health. We have summarised below secondary consultation outcome measures of patient care ‐ patient satisfaction and knowledge. The service outcome, consultation length, is also summarised below.

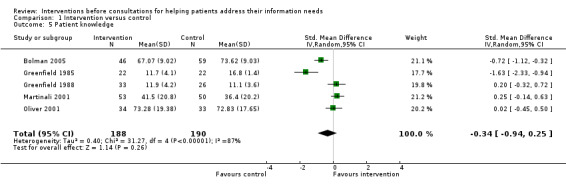

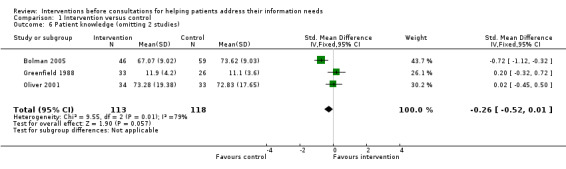

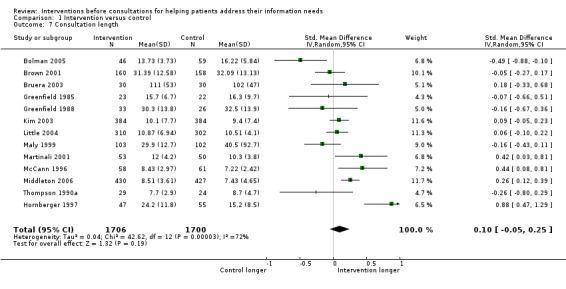

Meta‐analyses were undertaken for the outcomes of: patient question asking (Analysis 1.1), patient anxiety (before and after the index consultation (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3)) patient satisfaction (Analysis 1.4), knowledge (Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6), and consultation length (Analysis 1.7), where studies or authors provided appropriate data.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 1 Question asking.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 2 Anxiety (before consultation).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 3 Anxiety (after consultation).

1.4. Analysis.

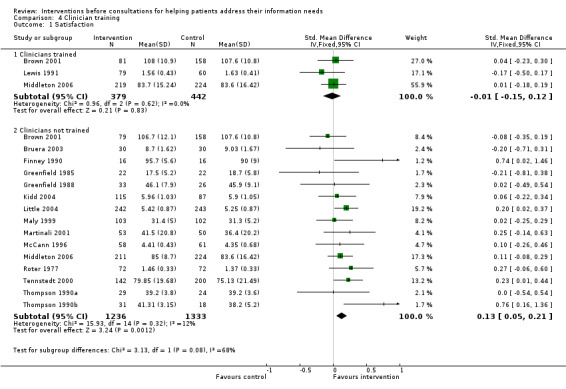

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 4 Patient satisfaction.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 5 Patient knowledge.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 6 Patient knowledge (omitting 2 studies).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 7 Consultation length.

Additional analyses examined the effect of the type of intervention (written materials versus coaching), timing of interventions (some time before the index consultation versus immediately before the index consultation) and co‐interventions (training for clinicians) for the same outcomes. However, for patient anxiety and knowledge there were insufficient studies in particular groups to undertake these further analyses, and for question asking it was only possible to investigate the effects of the type of intervention. To help with the interpretation of our findings, we considered effect sizes of around 0.2 to be 'small', 0.5 'moderate' and 0.8 or greater 'large' (Cohen 1988).

1. Consultation process

Question asking

With regard to consultation process outcomes, 17 studies measured question asking in the consultation, with 6 studies finding statistically significant increases (Brown 1999; Butow 2004; Cegala 2000; Kim 2003; Roter 1977; Thompson 1990a), and 11 studies finding no effects of the interventions compared to the controls (Brown 2001; Bruera 2003; Butow 1994; Fleissig 1999; Ford 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Kidd 2004; McCann 1996; Tabak 1988; Thompson 1990b).

The meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.1) shows a small and statistically significant increase in patient question asking (SMD 0.27 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.36). It should be noted that for the study by Roter (Roter 1977), we had to make two assumptions about the data; first, that the number of people analysed in the interventions and the control groups for the outcomes of question asking and patient satisfaction were equal, and second, that for patient satisfaction the means for the two groups were 1.46 and 1.37, and not 146 and 1.37 as stated in the text.

Patient participation

Patient participation in the consultation was measured in a variety of ways in 14 studies (Bolman 2005; Butow 2004; Cegala 2000; Fleissig 1999; Ford 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Kim 2003; Lewis 1991; Martinali 2001; Roter 1977; Sander 1996a; Sander 1996b; Tennstedt 2000). It was increased by the interventions in eight studies (Butow 2004; Cegala 2000; Fleissig 1999; Ford 1995; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Kim 2003; Lewis 1991), with no effect in five studies (Martinali 2001; Roter 1977; Sander 1996a; Sander 1996b; Tennstedt 2000). In Bolman 2005 participation was found to be increased after the first consultation and decreased in a second and third consultation.

2. Consultation outcomes

a) Patient health outcomes: anxiety

Anxiety is reported by the time of its measurement, either before or after the consultation.

With regard to primary consultation outcomes, patients' mental health was measured in the form of anxiety in 12 studies. In seven studies anxiety was measured before the index consultation (Bolman 2005; Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Butow 2004; Davison 1997; Ford 1995; Martinali 2001), but in three studies this was at the same time as the intervention (Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Davison 1997), so we considered it inappropriate to use this measurement as an outcome since it was intended as a baseline measure. However in four studies, the interventions were delivered some time before the consultation and anxiety was measured when the patient arrived for the consultation (Bolman 2005; Butow 2004; Ford 1995; Martinali 2001); in these studies we considered the assessment to be a true measure of the effects of the intervention.

Two studies which measured anxiety before the consultation found it to be reduced (Bolman 2005; Martinali 2001), one found it unchanged (Ford 1995) and one study found it increased (Butow 2004).

The meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.2) showed a large decrease in patient anxiety before consultations, but this result was not statistically significant (WMD ‐1.56 (95% CI ‐7.10 to 3.97)).

In the nine studies measuring anxiety after the index consultation, one study found an increase in anxiety (Brown 2001) two found decreases (Hornberger 1997; Thompson 1990a) and the other six studies found no effect (Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Butow 2004; Davison 1997; Ford 1995; Hornberger 1997; Lewis 1991; Little 2004; Thompson 1990a; Thompson 1990b). The meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.3) showed a small and statistically insignificant decrease in patient anxiety after consultations (SMD ‐0.08 (95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.06)).

b) Patient care outcomes: Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was measured in 23 studies. In 14 studies there were no changes (Bolman 2005; Brown 1999; Brown 2001; Bruera 2003; Butow 1994; Butow 2004; Davison 2002; Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Hornberger 1997; Martinali 2001; McCann 1996; Middleton 2006; Thompson 1990a) , and in 5 there was increased satisfaction (Fleissig 1999; Little 2004; Maly 1999; Roter 1977; Thompson 1990b). In two studies there were only increases for particular aspects of satisfaction (depth of relationship (Middleton 2006), interpersonal satisfaction (Tennstedt 2000)). In Lewis 1991 child satisfaction increased but parent satisfaction was unchanged (we used the data on parent satisfaction in the meta‐analyses, since all other patient groups were adults) and in Kidd 2004 there was no immediate change in satisfaction, but it was increased at three months post intervention.

The meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.4) shows a small and statistically significant increase in patient satisfaction (SMD 0.09 (95%CI 0.03 to 0.16)).

Patient satisfaction was affected by the type of intervention and its timing (see below).

Patient knowledge

With regard to secondary outcomes, patient knowledge was measured in five studies with reductions in two studies (Bolman 2005; Greenfield 1985) and no change in three studies (Greenfield 1988; Martinali 2001; Oliver 2001). However, in two studies we considered that the placebo intervention for the control group was likely to increase patients' knowledge of their condition, because it also included information about their condition (Greenfield 1985; Martinali 2001) .

The meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.5) shows a small and not statistically significant decrease in knowledge (SMD ‐0.34 (95% CI ‐0.94 to 0.25)). We repeated the analysis omitting Greenfield 1985 and Martinali 2001 (Analysis 1.6) and still found a small and not statistically significant decrease in knowledge (SMD ‐0.26 (95%CI ‐0.52 to 0.01)).

3. Service outcomes

Consultation length

Seventeen studies measured consultation length with 3 studies (Hornberger 1997; McCann 1996; Middleton 2006) finding statistically significant increases in consultation length and 13 studies (Brown 2001; Bruera 2003; Butow 1994; Butow 2004; Ford 1995, Greenfield 1985; Greenfield 1988; Kim 2003; Little 2004; Maly 1999; Martinali 2001; Roter 1977; Thompson 1990a) finding no effect. The study by Bolman (Bolman 2005) found that the first of three linked consultations was reduced in length, while the third consultation was increased.

The meta‐analysis (Analysis 1.7) shows a small and not statistically significant increase in consultation length (SMD 0.10 (95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.25)).

Consultation length was affected by the type of intervention and its timing (see below).

Clinician satisfaction

In three studies (Bruera 2003; Hornberger 1997; Lewis 1991) clinician satisfaction was measured, but with no notable effects identified. No meta‐analysis was conducted for this outcome.

With regard to other outcomes, there were no consistently positive effects.

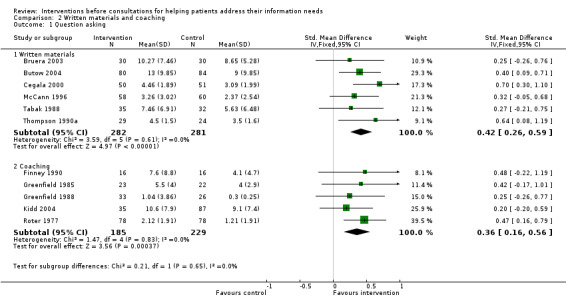

Types of intervention (written materials and coaching)

Question asking

With regard to the effects of different types of intervention, for the comparison between written materials alone and coaching alone there were similar, small to moderate and statistically significant increases for both types of intervention for the outcome of question asking (Analysis 2.1) (written materials SMD 0.42 (95% CI 0.26 TO 0.59); coaching SMD 0.36 (95% CI 0.16 to 0.56)).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Written materials and coaching, Outcome 1 Question asking.

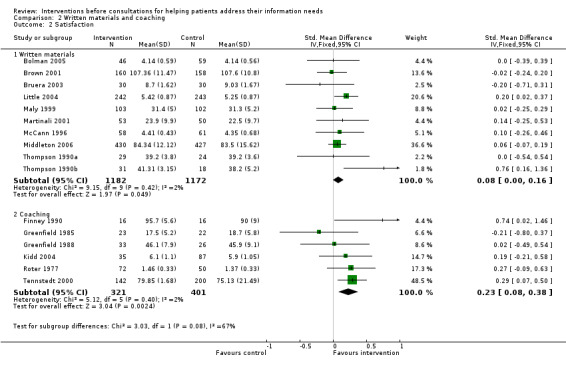

Patient satisfaction

For patient satisfaction (Analysis 2.2), written materials produced a small increase which was borderline for statistical significance (SMD 0.08 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.16)), whereas for coaching the effect was small and statistically significant (SMD 0.23 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.38)).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Written materials and coaching, Outcome 2 Satisfaction.

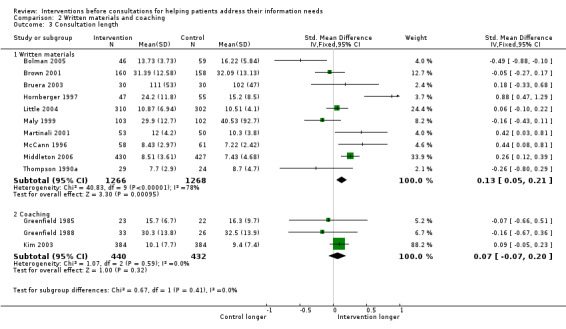

Consultation length

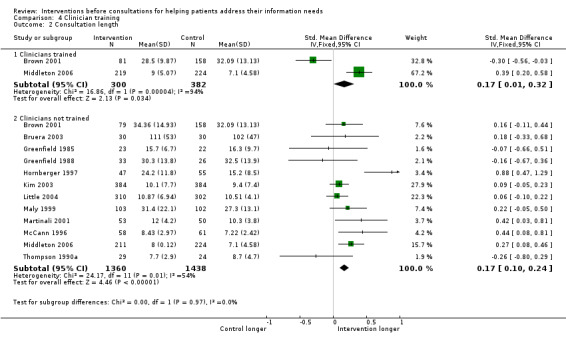

For the outcome of consultation length (Analysis 2.3), written materials led to a small and statistically significant increase in consultation length (SMD 0.13 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.21)), whereas for coaching there was a smaller increase in consultation length which was not significant (SMD 0.07 (95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.20)).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Written materials and coaching, Outcome 3 Consultation length.

Timing of the intervention

For the effects of timing of the intervention, there were only two studies with extractable data in which the interventions were conducted some time before the consultation (Bolman 2005; Martinali 2001).

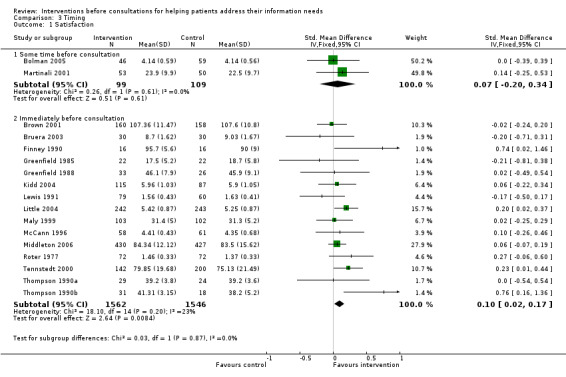

Patient satisfaction

For patient satisfaction (Analysis 3.1), interventions immediately before the consultation led to a small and statistically significant increase in patient satisfaction (SMD 0.10 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.17)) whereas those interventions given some time before the consultation led to a small and not significant change (SMD 0.07 (95% CI ‐0.20 to 0.34)).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Timing, Outcome 1 Satisfaction.

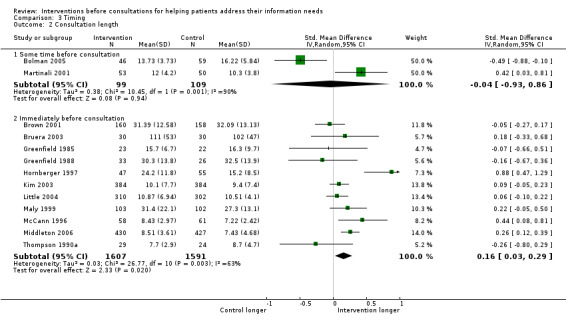

Consultation length

Similarly for consultation length (Analysis 3.2), interventions immediately before the consultation led to a small and statistically significant increase in consultation length (SMD 0.16 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.29)), whereas those some time before the consultation led to no change (SMD ‐0.04 (95% CI ‐0.93 to 0.86)).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Timing, Outcome 2 Consultation length.

Clinician training

For the effects of clinician training, there were two possible analyses to be considered. First, whether clinician training combined with interventions targeted at patients provided greater benefits than interventions targeted at patients alone. Since we considered this comparison to be of prime interest to those wanting to improve services to patients, we conducted a meta‐analysis of these data (Analysis 4.1; Analysis 4.2).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Clinician training, Outcome 1 Satisfaction.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Clinician training, Outcome 2 Consultation length.

Three studies contained usable data of combined interventions for the outcomes of patient satisfaction and consultation length (Brown 2001; Lewis 1991; Middleton 2006).

Patient satisfaction

Meta‐analysis showed that additional clinician training had no effect on patient satisfaction (Analysis 4.1) when interventions were combined with clinician training (SMD ‐0.01 (95%CI ‐0.15 to 0.12)) compared with patient interventions alone which had a small effect (SMD 0.13 (95%CI 0.05 to 0.21)).

Consultation length

We found the same effects on consultation length in studies where there was additional clinician training as in studies where there was no clinician training (Analysis 4.2). In both types of study there was little impact on consultation length (studies with clinician training SMD 0.17 (95% CI 0.01 TO 0.32); studies without clinician training SMD 0.17 (95%CI 0.10 to 0.24)). An alternative approach is to consider the impact of patient interventions in the context of the clinicians also receiving training (that is, all clinicians being trained so that patients from both control and intervention groups saw trained clinicians). For this analysis, two studies contained relevant data (Bolman 2005; Middleton 2006). Bolman 2005 showed that the patient intervention produced a small decrease in consultation length (SMD ‐0.49 (95%CI ‐0.88 to ‐0.10)) and had no effect on patient satisfaction (SMD 0.00 (95%CI ‐0.39 to 0.39)). Middleton 2006 showed a small increase in consultation length (SMD 0.24 (95%CI ‐0.05 to 0.43)), and very little effect on patient satisfaction (SMD 0.03 (95%CI ‐0.16 to 0.22)).

From these two analyses we conclude, from the limited evidence available, that there are no clear benefits from clinician training, either combined with patient interventions or before the implementation of patient interventions.

Three studies were randomised by clinician (Hornberger 1997; Lewis 1991; Tennstedt 2000). These cluster randomised trials may have overestimated the effects found. We re‐calculated the effect sizes and confidence intervals without these studies, and found small changes to the reported results (Additional Table 4). It should be noted that other studies may have also been vulnerable to clustering effects, and reported standard errors and confidence intervals may be overestimates.

4. Comparison of results with and without clustered data.

| Comparison | Effect size all data | 95% CI | Effect size no clust | 95%CI |

| INTERVENTION VERSUS CONTROL | ||||

| Anxiety (after consultation) | ‐0.08 | ‐0.22 to 0.06 | ‐0.09 | ‐0.23 to 0.06 |

| Patient satisfaction | 0.09 | 0.03 to 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.02 to 0.16 |

| Consultation length | 0.10 | ‐0.05 to 0.25 | 0.05 | ‐0.08 to 0.18 |

| WRITTEN MATERIALS VERSUS COACHING | ||||

| Coaching: Satisfaction | 0.23 | 0.08 to 0.38 | 0.18 | ‐0.03 to 0.39 |

| Written materials: Consultation length | 0.13 | 0.05 to 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.02 to 0.18 |

| TIMING OF INTERVENTION | ||||

| Immediately before consultation: Satisfaction | 0.10 | 0.02 to 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.02 to 0.17 |

| Immediately before consultation: Consultation length | 0.16 | 0.03 to 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.01 to 0.22 |

| CLINICIAN TRAINING | ||||

| Clinicians trained: Satisfaction | ‐0.01 | ‐0.15 to 0.12 | 0.02 | ‐0.14 to 0.17 |

| Clinicians not trained: Satisfaction | 0.13 | 0.05 to 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.03 to 0.20 |

| Clinicians not trained: Consultation length | 0.17 | 0.10 to 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.07 to 0.22 |

Discussion

Patients still do not get the information they require in clinical consultations (Rogers 2005). This review identified 33 randomised trials, in a range of settings and countries, of interventions designed to address this challenge which were targeted at patients. Our meta‐analyses show that although the individual effects found in particular trials may be small or non‐significant, when combined there are small and statistically significant effects in terms of increased patient question asking and increased patient satisfaction. The result for patient anxiety before consultations demonstrated a large, but not statistically significant, effect. Results for patient anxiety after consultations and consultation length were also small and not statistically significant. The effects of the interventions on patient knowledge are unclear due to methodological difficulties. Assessing patient participation remained a challenge throughout the review; although commonly measured, a range of methods are used (from tapes of consultations and from patient questionnaires); additionally, participation could mean different things to different people.

Question asking

The increase in question asking demonstrates the most direct effect of the interventions. Patients were asked, largely through written messages or coaching, to identify questions, and told that the clinicians were interested in the patients asking these questions and would try to provide information. While increased question asking in itself may be of little direct benefit to patients or clinicians, these findings demonstrate that relatively straight forward interventions are able to influence the dialogue between clinician and patient, albeit to a small degree. However, the interventions may be expected to have greater direct effects. A possible explanation for this is that many clinicians, and probably patients, adopt 'ritual' styles of consulting (Neighbour 1996), and these may not readily be changed by interventions, particularly if delivered immediately before the consultation and only targeted at one participant in the consultation (as most of these interventions were). Unfortunately, we did not have the data to explore whether question asking increased more when the clinicians were trained. In addition, desire for information by patients may not necessarily translate into question asking (Beisecker 1990). As a result, while the interventions may have helped patients to identify questions to ask, patients may have been unable to ask them, and may have left with the questions unanswered (Butow 2004; Fleissig 1999). Another possibility is that the doctor may have given the information unprompted and in trials randomising by patient there is the real possibility that clinicians may start giving more information to all patients, and not only those who asked questions. This could minimise the effects found for all outcomes; not just question asking. It should also be noted that most studies using this outcome focused on the number of questions asked, rather than the type of questions or topics raised. It would be hoped that the increase in number of questions indicated that the patient was able to address important information needs. This is supported by Brown's finding of an increase in the number of questions about prognosis in patients with cancer (Brown 2001). Prognosis would clearly be a topic of great significance in this patient group, but also could be an issue that patients might be reluctant to address without specific encouragement (Fleissig 2000; Leydon 2000).

Patient anxiety

The tentative finding of a reduction in patient anxiety before consultations indicates the most sizeable effect of the interventions. However, this result did not reach statistical significance and the number of studies and patients involved is small (3 studies involving 372 patients). Patients attending consultations feel they have a story to tell and questions to which they want answers (Helman 2007). However, they may feel uncertain as to whether they will get the chance to express their needs and get the information they seek. It would appear that the interventions reviewed here may act as an acknowledgement to the patients that their concerns will be heard and that they will get their questions answered. In addition, helping patients to organise their thoughts and plans for the consultation is likely to be an effective strategy for reducing anxiety. It should be noted, however, that the study by Butow which involved patients with cancer showed an increase in patient anxiety (Butow 2004), which suggests that the effects may be different with particular patient groups. It is also notable that Bolman found that fewer patients used the intervention at successive consultations and that pre‐consultation anxiety increased before each successive consultation in both the control and intervention groups (Bolman 2005). This suggests that rather than patients becoming familiar with the physicians at the clinic and feeling less need to organise themselves, they were finding that the clinicians were relatively unresponsive to their questions and thus there was little to be gained from the process. Support for this possibility comes from the finding that anxiety after consultations was not similarly reduced. It might be hoped that the interventions would give patients a greater sense of control within the consultations as they would be more organised about their concerns and more assertive. In addition, they would have identified and in some cases practised asking the questions they wanted to ask to alleviate their concerns. However, anxiety may not consequently be reduced for two possible reasons. First, the clinician may not respond helpfully, thus frustrating the patient's attempts to gather information or, second, the information provided as a result of the increased question asking may be worrying. This would be particularly likely in oncology clinics (in which nine studies were set).

Patient satisfaction