Abstract

Helicobacter pylori represents a global health threat with around 50% of the world population infected. Due to the increasing number of antibiotic-resistant strains, new strategies for eradication of H. pylori are needed. In this study, we suggest purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) as a possible new drug target, by characterising its interactions with 2- and/or 6-substituted purines as well as the effect of these compounds on bacterial growth. Inhibition constants are in the micromolar range, the lowest being that of 6-benzylthio-2-chloropurine. This compound also inhibits H. pylori 26695 growth at the lowest concentration. X-ray structures of the complexes of PNP with the investigated compounds allowed the identification of interactions of inhibitors in the enzyme’s base-binding site and the suggestion of structures that could bind to the enzyme more tightly. Our findings prove the potential of PNP inhibitors in the design of drugs against H. pylori.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, purine nucleoside phosphorylase, substituted purines, minimal inhibitory concentration, X-ray structure

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori, discovered about 30 years ago1, is a bacterial pathogen known for its ability to colonise and persist in the human stomach2, and today affects more than half of the world’s population. Although most infections caused by this bacterium are asymptomatic, H. pylori is strongly associated with severe diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract, such as chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, duodenal ulcer, and gastric cancer, and it is classified as a group I carcinogen3–6. There are various recommended treatments for the eradication of H. pylori. However, all of them require the use of at least three drugs, as in the first-line triple therapy, and yet they are ineffective in more than 20% of patients, mainly due to the constantly increasing number of strains resistant to one or more antibiotics used in these therapies7. H. pylori clarithromycin-resistant strains have recently been recognised by WHO as one of the 12 priority pathogens for which novel antibiotics are urgently needed8. With a general increase in the consumption of antibiotics, the number of resistant strains is also expected to rise, so a large effort is currently being made to identify new targets for potential drugs that will combat H. pylori using different molecular mechanisms than the drugs currently in use9. One of the recent examples of an innovative strategy in anti-ulcer treatment is the use of inhibitors of bacterial carbonic anhydrase in combination with probiotic strains10.

Enzymes belonging to the purine salvage pathway are possible targets of such new drugs because numerous microorganisms, including infectious pathogenic species, are unable to synthesise de novo purine nucleotides11–16. Therefore, the recovery of purines and purine nucleotides from the environment is for them the only source of these essential DNA and RNA building blocks. Given the importance of purine production and its direct effect on the organisms growth rate, targeting enzymes of the purine salvage pathway became a promising approach to find new drugs against such pathogens. One promising example of the new drug candidate is DADMe-Immucillin-G, a transition state inhibitor of the key enzyme of the purine salvage pathway, purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP), which shows clinical potential for treatment of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum16.

PNP, or purine nucleoside orthophosphate ribosyl transferase (EC 2.4.2.1) catalyses the reversible phosphorolytic cleavage of the glycosidic bond of purine ribo and deoxyribonucleosides as follows:

Relatively recently, it was discovered that H. pylori also belongs to this class of microorganisms incapable of de novo purine synthesis17. Nucleoside phosphorylases play a key role in the salvage pathway18 and, as far as we know, no one has tried to use inhibitors of the PNP to fight H. pylori infection. Therefore, in this study, we decided to check the influence of inhibitors of PNP from H. pylori on the growth rates of this bacterium in cell culture, and obtain a high-resolution three-dimensional structure of the enzyme-inhibitor complexes to characterise details of the enzyme-ligand interactions. As PNP from H. pylori is similar to the E. coli PNP19–21 we decided in the first attempt to check some known inhibitors of the latter enzyme, namely, 2,6-substituted purines22.

Materials and methods

Materials

Guanosine (Guo) and 2,6-dichloropurine (2,6-diCl-Pu, MW 189.00 g/mol) were purchased from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO), magnesium chloride, sodium chloride, sodium dihydrogen phosphate, Tris and Hepes were from Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany), NaOH 99% pure was from POCh (Gliwice, Poland). 7-methylguanosine (m7Guo) was synthesised from guanosine according to Jones’ and Robins’ method23 involving methyl iodide. This yields the preparation free from sulphate, which as an ion resembling phosphate could bias the results.

PNP from Helicobacter pylori strain 26695 (H. pylori PNP [HpPNP]) was purified as described previously20. Affinity chromatography was the final step of this purification. The Sepharose-Formycin A column, which is necessary for this step, was prepared as described previously for activating Sepharose CL-6B with adenosine and formycin B24,25.

The synthesis of known compounds 6-benzyloxy-2-chloropurine (6BnO-2Cl-Pu, MW 260.68 g/mol), 6-benzylthio-2-chloropurine (6BnS-2Cl-Pu, MW 276.74 g/mol), and 6-benzylthiopurine (6BnS-Pu, MW 242.3 g/mol)22,26 is described in the Supplemental Materials.

The 2-chloro-6-benzylthiopurine-2’deoxy-9-ribofuranoside (6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr, MW 393.87 g/mol) was a kind gift of prof. Zygmunt Kazimierczuk (Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Warsaw, Poland).

Culture reagents – fetal bovine serum (FBS), Helicobacter pylori Selective Supplement, Brain Heart Infusion Broth (BHI medium) and Christensen’s Urea Broth were from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Kanamycin (MW 484.5 g/mol), metronidazole (MTZ; MW 171.15 g/mol), glycerol (MW 92 g/mol), methanol (MW 32.04 g/mol), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO MW 78.13 g/mol) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO).

The 24-deep-well 2 ml plates, flat-bottomed for H. pylori culture and 96-deep-well microplates were from Nest Scientific Biotechnology (Rahway, NJ). Atmosphere generators were purchased from Mart Microbiology B.V., The Netherlands (Anoxomat Mark II). Microplate reader was from Tecan (Switzerland). Sterile syringe filters with a 0.22 µm pore size were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). The H. pylori wild-type strain 26695 was obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA).

All spectrophotometric studies were performed on a double-beam UV/VIS spectrophotometer Cary 100, with thermostated Peltier cell holders (Varian: Agilent Technologies, Mulgrave, Vic., Mulgrave, Australia).

PNP inhibition studies

Usually, the specific activity of PNP is determined with inosine as a substrate, using the assay in which the product of phosphorolysis, hypoxanthine, is oxidised to uric acid in a coupled reaction catalysed by xanthine oxidase27. However, for inhibition studies of PNP from H. pylori strain 26695, 7-methylguanosine and guanosine were used as nucleoside substrates to avoid possible inhibition of xanthine oxidase by the tested compounds. Phosphorolysis of these two substrates may be observed using a direct spectrophotometric method as described previously28,29. Spectral data for substrate concentration determination and for the activity assays used in this study, are the following: εmax =13,650 M−1 cm−1 for Guo29, εmax = 8500 M−1 cm−1 for m7Guo (at pH 7.0)28, Δε = −4850 M−1 cm−1 at λobs = 252 nm for Guo29 and Δε = −4600 M−1 cm−1 at λobs = 258 nm for m7Guo (at pH 7.0)28.

The enzyme activity was measured in a cuvette with the optical pathlength of 1 or 0.5 cm, so the absorption of the reaction mixture never exceeded 1.2. The reaction volume was 1 or 1.4 mL in 1 and 0.5 cm pathlength cuvettes, respectively. The reaction mixture contained 50 mM HEPES/NaOH buffer pH 7.0, 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.0, substrate, and inhibitor (the latter was omitted in the reference reactions).

For HpPNP inhibition studies, the tested compounds were dissolved in methanol, so that the concentration of stock solution was 5 or 10 mM. Inhibitor concentration was calculated based on the weighted amount and confirmed with the absorbance measurement at pH 7.0 in water containing 10% methanol (v/v) and using the extinction coefficients ε261 nm=10,900 M− 1 cm− 1 for 6BnO-2Cl-Pu and ε299 nm = 18,000 M−1 cm−1 for all compounds bearing the 6-BnS substituent22.

The range of substrate concentration used was 10–280 µM, and the broadest range of inhibitor concentration used was 0–15 µM for 6BnS-Pu and 2,6-diCl-Pu, while the lower maximal concentration for other, stronger inhibitors was sufficient to determine the inhibition constants. In the amount added with inhibitors, the effect of methanol on the enzyme activity was measured separately and found to be negligible.

The reaction mixture was pre-incubated for 5 min at 25 °C and enzyme activity (represented here as a change of initial absorbance over time) was measured for the next 2 min. Enzyme velocity was calculated as specific activity in given conditions, expressed in U/mg (U is the amount of enzyme that converts 1 µmol of substrate per minute at 25 °C). Initial velocity was calculated for the period 0.5–1.0 and 1.0–2.0 min from enzyme addition, to check for the linear absorbance change. The average value was taken to determine velocity in the absence and in the presence of inhibitors, vo and vi, respectively.

The equations of different types of inhibition were fitted to the experimental data by GraphPad Prism version 8 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) to determine the type of inhibition and inhibition constant. The best model was chosen based on the extra sum-of-squares F test for the models with a different number of parameters and on the Akaike’s criterion (AIC) for the models that are not nested.

Equations fitted to the data represent uncompetitive (1), non-competitive (2), and mixed type inhibition (3)30:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

The latter equation may be rearranged to the form of Equation (8.17) from31, which is used by the GraphPad Prism program, where Kiu = alpha Kic:

| (4) |

Determination of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) vs. H. pylori strain 26695

H. pylori ATCC 26695 was maintained as a frozen stock at −80 °C in BHI medium (37 g/L) supplemented with 20% glycerol and 10% FBS. Bacteria were grown on BHI agar plates containing 10% FBS and 1% H. pylori Selective Supplement under microaerophilic conditions at 37 °C for 3 d. Microaerophilic conditions were generated using an atmosphere generator Anoxomat Mark II. Overnight liquid culture of H. pylori was grown by shaking at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions in BHI medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% H. pylori Selective Supplement. Subsequently, double strengthened BHI medium was supplemented with 20% FBS and 2% H. pylori Selective Supplement.

The experiment was carried out in 24-deep-well 2 mL flat-bottomed plates, all in a final volume of 500 µL. In each well, 2-fold serial dilutions of inhibitors (in a final volume) and an equal volume of inoculated double-strength BHI were added (approximately 0.05 optical density OD600 which corresponds to 4 × 104 CFU/mL in a final volume). Kanamycin 25 µg/mL32 was used as a positive control, while Milli-Q water and BHI medium untreated with H. pylori were used as negative controls. H. pylori was grown on the plates with shaking (120 rpm) at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions and OD600 of samples was measured in the microplates at the start of the experiment and after 4, 8, and 24 h for minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination33. In the negative control after 24 h incubation, hence at the end of the experiment, OD600 typically was in the range of 1.2–1.4, which corresponds to about 106 CFU/mL. This method was further improved by applying the approach of Knezevic et al.34, which checks if the change in OD600 comes from viable H. pylori cells. The equal volume of double strength Christensen’s urea broth was added into wells after incubation, and the plates were additionally incubated for 4 h in an aerobic atmosphere at 37 °C. During the incubation, in wells with viable H. pylori urease produced by the bacteria converted urea into ammonia and carbon dioxide, changing the pH and colour of a phenol red indicator in the medium (from orange to purple)34. The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of a compound that inhibits visible growth (absence of colour change), compared with the growth in the controls (presence of colour change), which in the OD600 monitoring method corresponds to inhibition comparable to that in the positive control with 25 µg/mL kanamycin (i.e. % of inhibition of bacterial growth is 90% or higher). All experiments were performed in three repetitions.

Checkerboard assay

The combined antimicrobial activity of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu with MTZ was determined against H. pylori 26695 strain using the checkerboard assay35. Concentrations below MIC were tested. A concentration gradient used for the 6BnS-2Cl-Pu was 3.0–10.0 µg/mL. The range of MTZ concentrations was chosen based on MIC given in EUCAST36, 8 µg/mL. However, in our case, H. pylori 26695 strain, already with 2 µg/mL we observed 89–92% inhibition (Table 3). The range of concentrations of the tested compounds was prepared in test tubes in such a way as to obtain twice the test concentrations when testing the activity of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu or MTZ alone and four-fold test concentrations when testing the combination of both.

Table 3.

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, and inhibition obtained at the maximal solubility in 3.5% DMSO of the compounds tested in this study, against H. pylori 26695 strain cell cultures.

| Inhibitor | MW | MICa |

Maximal solubility |

% of H. pylori cell culture inhibition at inhibitor maximal solubility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [µg mL−1] | [µM] | [µg mL−1] | [µM] | |||

| DMSO | 78.13 | – | – | 55.0b | – | 60e |

| 38.5b | – | 26e | ||||

| 27.5b | – | 0e | ||||

| 2,6-diCl-Pu | 189.00 | 473 | 2500 | 236 | 1250 | 93 |

| 6BnO-2Cl-Pu | 260.68 | – | – | 25c | 95c | 35 |

| 91d | 350d | 75 | ||||

| 6BnS-2Cl-Pu | 276.74 | 69d | 250d | 11.1 | 40 | 92 |

| 6BnS-Pu | 242.3 | 48d | 200d | 21 | 85 | 83 |

| 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr | 393.87 | 79d | 200d | 4.3c | 10.8c | 5 |

| metronidazole | 171.15 | 8f | 47 | 2g | 12g | 89–92 |

| kanamycin | 484.5 | 0.5–64f | 1.1–132 | 25g | 52g | 92–96 |

| BHI medium untreated with H. pylori | – | – | – | – | – | 95h |

The results are presented as the mean of three repetitions (see Materials and methods).

aMIC is the minimal concentration used in the series of 2-fold dilutions that gave full inhibition of H. pylori cell culture growth, i.e. comparable to that observed for the positive control with 25 µg/mL kanamycin, i.e. by 92–96%.

bThese correspond to 5%, 3.5%, and 2.5% (v/v), respectively, and in this case, this is not the maximal solubility; DMSO density 1.1 g/cm³.

cIt was a maximal concentration possible to obtain in given conditions (at this concentration saturation was observed, see Table S1).

dInhibitor partially precipitated, so actual concentration of dissolved compound is lower.

eIn each experiment, the inhibition by DMSO was always checked to see its effect in this particular case, and compared with the effect of the HpPNP inhibitor tested. It was necessary as inhibition observed for the particular % of DMSO differs slightly among the experiments.

gIn this case this concentration is not the maximal solubility.

hIn this case there is no H. pylori, so the value shown is treated as a negative control.

The experiment with controls was prepared in the same way as described previously in the section “Determination of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) vs. H. pylori strain 26695.” The experiment was carried out in 24-deep-well 2 mL flat-bottomed plates, all in a final volume of 500 µL. In each well, where the activity of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu or MTZ alone was tested, 250 µL of one or the other substance in twice the test concentration and an equal volume of inoculated double-strength BHI were added (approximately 0.05 optical density OD600 which corresponds to 4 × 104 CFU/mL in a final volume). Whereas to the remaining wells, in which the interactions in the antimicrobial activity were determined, 125 µL of each 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and MTZ in four-fold test concentration with 250 µL of inoculated double-strength BHI were added (approximately 0.05 optical density OD600 which corresponds to 4 × 104 CFU/mL in a final volume). The plates were incubated with shaking (120 rpm) at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions and OD600 of samples was measured in the microplates after 4, 8, and 24 h for MIC determination. The MIC values were confirmed using Christensen’s urea broth. All experiments were performed in three repetitions.

The interaction between the tested compounds was determined by calculating the fractional inhibitor concentration index (FICI) as FICI = (MICA/MICa) + (MICB/MICb), where MICA = MIC of substance a, in the presence of substance b; MICa = MIC of substance a, applied as a single agent; MICB = MIC of substance b, in the presence of substance a, and MICb = MIC of inhibitor b, applied as a single agent. The results were interpreted as a synergistic effect if the FICI was <0.5; as an additive effect if 0.5 < FICI <1; a neutral effect if 1 < FICI <4; and as an antagonistic effect if the FICI was >437.

Preparation of solutions of tested compounds for H. pylori cell culture inhibition test

For checking the influence of the PNP inhibitors used in this study on the H. pylori cell culture growth, 10 mM stocks of 6BnO-2Cl-Pu, 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, 6BnS-Pu, and 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr were prepared in DMSO, while 10 mM stock of 2,6-diCl-Pu was prepared in milli-Q water. In some cases, 15 mM stock of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu was used. Stocks in DMSO were diluted with water, so that the DMSO content in the final solution used in the cell culture experiments in most cases did not exceed 5% (v/v). Hence, after two-fold dilution of the bacterial culture, the DMSO concentration in the experiment was a maximum 2.5% (in some cases 3.5%). It was independently checked that concentration up to 2.5% is almost neutral for the growth of H. pylori, while higher DMSO content inhibits H. pylori growth (Figure S5). Nevertheless, in each experiment, the inhibition by DMSO was always checked to see its effect in this particular case, and compared with the effect of the HpPNP inhibitor tested. It was necessary as inhibition observed for the particular % of DMSO differs slightly among the experiments. Two-fold serial dilutions with water prepared from the 10 mM 2,6-diCl-Pu stock show no precipitated compound, as this purine derivative exhibits good solubility in water. By contrast, upon dilution with water, also depending on the final concentration planned to obtain, in the case of the four other tested compounds, 6BnO-2Cl-Pu, 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, 6BnS-Pu, and 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr, a part of the dissolved inhibitor precipitated out of the solution. To overcome this problem, such solutions were filtered through sterile syringe filters with a 0.22 µm pore size and the supernatants thus obtained were tested in H. pylori culture. The concentration of the tested compounds present in the final filtered solutions was measured spectrophotometrically using the extinction coefficients shown in the section “PNP inhibition studies.” Second, the parallel approach used to determine the MIC of these compounds was to use unfiltered supernatants in which part of the compound was in solution and part in the form of precipitate (Table S1).

Crystallisation, data collection, and structure determination

Crystals of HpPNP complexes were obtained by the hanging-drop vapour diffusion method. The drops involved were set up with 1 or 2 μL of protein complexed with ligands and 1 or 2 μL of reservoir solution, whereas the reservoir volume was 700 μL. The crystallisation conditions were identified previously21 and contained 0.02 M MgCl2, 0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 7.0–7.6, 9–13% PEG 8000. For crystallisation, HpPNP (9–10 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 7.6) was mixed with ligands (0.5–0.6 mM phosphate and 0.5–1.4 mM 2,6-substituted purine) and kept for 30 min before setting up the crystallisation drops. The complex of HpPNP with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu was obtained by mixing protein with the respective nucleoside 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr and allowing the phosphorolysis to occur. The complex of HpPNP with 2,6-diCl-Pu was obtained by soaking and using different crystallisation conditions, namely, 0.2 M imidazole, pH 7.0 and PPG 400. The ligand was added as a powder to the drop with already existing crystals and stayed for 3 d before freezing.

Data collection for all structures was done at the XRD1 beamline of the Elettra synchrotron, Trieste, Italy using the Dectris Pilatus 2 M detector. The data collection and refinement parameters for the structures are summarised in Table 1. The data were integrated using the XDS program38. All structures were solved by molecular replacement using the Molrep program39 and using the structure of H. pylori PNP (PDB code 5LU020) as a model, and the ligands were located in the difference maps. The models were then refined using the phenix.refine routine from the Phenix package40. Coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the following PDB codes: 7OOY for 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, 7OOZ for 6BnO-2Cl-Pu, 7OPA for 6BnS-Pu, and 7OP9 for 2,6-diCl-Pu. The figures of X-ray structures were made using Pymol41.

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics.

| Structure | 6BnS-2Cl-Pu | 6BnO-2Cl-Pu | 6BnS-Pu | 2,6-diCl-Pu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution range | 35.9–1.9 (1.97–1.9)a | 35.9–1.7 (1.76–1.7) | 46.35–2.0 (2.07–2.0) | 42.59–1.5 (1.55–1.5) |

| Space group | P 21 3 | P 21 3 | P 212121 | P 1 |

| Unit cell | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 113.6, 113.6, 113.6 | 113.7, 113.7, 113.7 | 67.6, 139.0, 318.7 | 93.4, 93.4, 95.4 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 81.9, 79.3, 60.1 |

| Total reflections | 433,440 (40977) | 465,820 (44846) | 2,504,977 (186198) | 1,079,039 (98731) |

| Unique reflections | 38,724 (3843) | 54,014 (5331) | 202,884 (19800) | 419,695 (38205) |

| Multiplicity | 11.2 (10.7) | 8.6 (8.4) | 12.3 (9.4) | 2.6 (2.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.97 (99.97) | 99.93 (99.61) | 99.83 (98.78) | 94.95 (86.85) |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 7.83 (1.14) | 12.18 (1.53) | 9.85 (0.76) | 9.13 (1.78) |

| Wilson B-factor | 20.88 | 19.04 | 36.70 | 13.35 |

| Rmerge | 0.32 (2.1) | 0.12 (1.27) | 0.18 (2.18) | 0.09 (0.52) |

| Rmeas | 0.33 (2.2) | 0.13 (1.36) | 0.19 (2.30) | 0.11 (0.66) |

| Rpim | 0.10 (0.69) | 0.04 (0.46) | 0.05 (0.73) | 0.07 (0.39) |

| CC1/2 | 0.99 (0.48) | 0.99 (0.60) | 0.99 (0.57) | 0.99 (0.54) |

| CC* | 0.99 (0.80) | 0.99 (0.87) | 0.99 (0.85) | 0.99 (0.84) |

| Reflections used in refinement | 38,720 (3843) | 54,008 (5330) | 202,855 (19799) | 417,539 (38185) |

| Reflections used for Rfree | 1992 (197) | 1989 (197) | 1999 (196) | 2013 (187) |

| Rwork | 0.16 (0.26) | 0.16 (0.28) | 0.23 (0.39) | 0.17 (0.31) |

| Rfree | 0.20 (0.31) | 0.19 (0.31) | 0.28 (0.43) | 0.20 (0.37) |

| CCwork | 0.97 (0.78) | 0.97 (0.82) | 0.92 (0.34) | 0.97 (0.84) |

| CCfree | 0.96 (0.77) | 0.96 (0.83) | 0.90 (0.43) | 0.97 (0.70) |

| Number of non-hydrogen atoms | 4106 | 4104 | 22,971 | 25,064 |

| Macromolecules | 3627 | 3653 | 21,616 | 21,765 |

| Ligands | 79 | 146 | 198 | 214 |

| Solvent | 400 | 305 | 1157 | 3085 |

| Protein residues | 466 | 466 | 2796 | 2796 |

| RMS(bonds) | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.006 |

| RMS(angles) | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 0.93 |

| Ramachandran favoured (%) | 96.75 | 96.97 | 94.59 | 96.89 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 3.25 | 3.03 | 4.87 | 3.11 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.54 | 0.00 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 1.26 | 1.25 | 3.79 | 0.46 |

| Clashscore | 5.20 | 4.02 | 10.46 | 4.23 |

| Average B-factor | 24.02 | 23.22 | 44.93 | 19.03 |

| Macromolecules | 22.92 | 22.04 | 45.06 | 17.66 |

| Ligands | 29.32 | 32.70 | 47.49 | 18.50 |

| Solvent | 32.93 | 32.86 | 41.99 | 28.74 |

aStatistics for the highest-resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Results and discussion

Inhibition of the H. pylori purine nucleoside phosphorylase

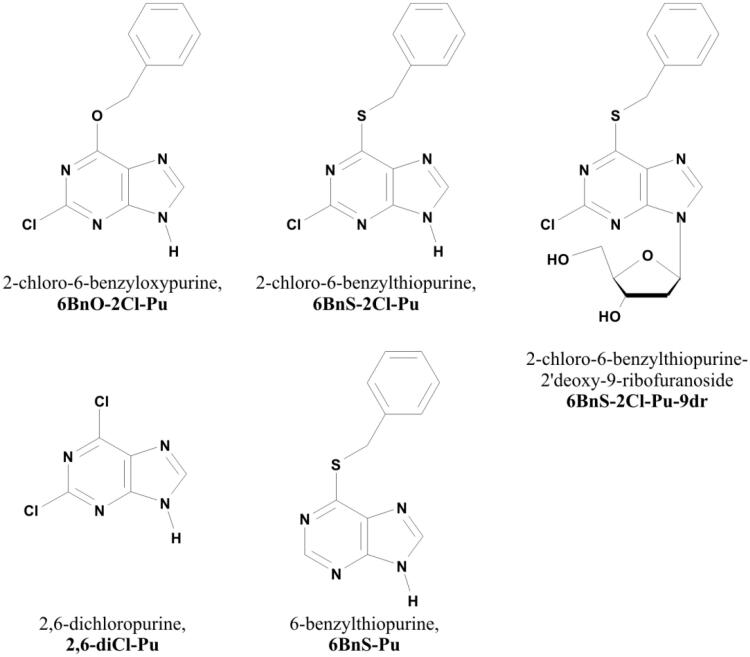

Inhibition of H. pylori PNP by 2- and/or 6-substituted purines, and by a 2′-deoxyriboside of 2-chloro-6-benzylthiopurine (Figure 1), was studied with 7-methylguanosine as variable substrate at saturating phosphate concentration (50 mM). Inhibition model and inhibition constants were determined and are depicted in Table 2. Data are also shown in Figures 2 and 3 and Figure S4. In most cases studied, when the Michaelis–Menten equation was fitted to each kinetic trace separately, it was found that both parameters, Michaelis constant, Km, and the maximal velocity, Vmax, significantly change when the inhibitor is present. Therefore, the mixed inhibition model was fitted globally to the whole data set for each compound, and compared with the fitting of the simpler models, competitive, non-competitive, and uncompetitive to the same data set.

Figure 1.

Structure of purine derivatives used in this study.

Table 2.

Inhibition properties of some purines substituted at positions 2 and/or 6, and deoxyriboside of one of them, vs. H. pylori PNP.

| Inhibitor | Kin [µM] | Kic [µM] | Kiu [µM] | alphaa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,6-Dichloropurineb | 22.2 ± 1.4 | – | – | – |

| 2,6-Dichloropurine | – | 20.0 ± 4.9 | 23.5 ± 3.5 | 1.17 ± 0.44 |

| 6-Benzylthiopurineb | 7.9 ± 0.4 | – | – | – |

| 6-Benzylthiopurine | – | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 8.1 ± 0.7 | 1.07 ± 0.27 |

| 2-Chloro-6-benzyloxypurinec | – | 18.3 ± 7.3 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | 0.25 ± 0.12 |

| 2-Chloro-6-benzyloxypurine | 6.5 ± 0.4 | – | – | – |

| 2-Chloro-6-benzyloxypurine | – | – | 3.8 ± 0.3 | – |

| 2-Chloro-6-benzylthiopurined | – | – | 1.8 ± 0.2 | – |

| 2-Chloro-6-benzylthiopurine | – | 13.2 ± 10.7 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 0.16 ± 0.15 |

| 2-Chloro-6-benzylthiopurine-2′deoxy-9-ribofuranosidec | – | 6.2 ± 2.4 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 0.47 ± 0.24 |

| 2-Chloro-6-benzylthiopurine-2′deoxy-9-ribofuranosidec,e | – | 12.6 ± 5.7 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.16 ± 0.08 |

Data were obtained at 25 °C, in the 50 mM Hepes/NaOH buffer pH 7.0, at saturating phosphate concentration of 50 mM. If not otherwise indicated, m7Guo was used as variable substrate.

aAlpha = Kiu/Kic, see Equation (3) and (4) in Materials and methods.

bNon-competitive inhibition model is the best.

cMixed inhibition model is the best.

dUncompetitive inhibition model and mixed type inhibition have similar probability. Due to poor solubility of the compound, data are limited to low inhibitor concentration, errors of Kic and parameter alpha are big, so it is not possible to unequivocally decide which inhibition model is actually better, uncompetitive or mixed.

eInhibition vs. guanosine as variable substrate.

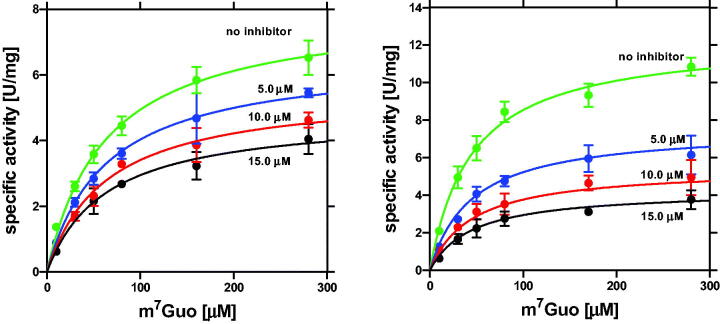

Figure 2.

Inhibition of H. pylori PNP at 25 °C, 50 mM Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.0, by 2,6-diCl-Pu (left) and by 6-BnS-Pu (right) with m7Guo and 50 mM phosphate as substrates. Initial velocity, vo, vs. variable substrate concentration (m7Guo), with no inhibitor added (green circles) and with several various concentrations of the inhibitor are shown; error bars represent SD; solid lines represent global fitting of the non-competitive inhibition model.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of H. pylori PNP at 25 °C, 50 mM Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.0, by 6BnO-2Cl-Pu (left) and by 6BnS-2Cl-Pu (right) with m7Guo and 50 mM phosphate as substrates. Initial velocity, vo, vs. variable substrate concentration (m7Guo), with no inhibitor added (green circles) and with several various concentrations of the inhibitor are shown; error bars represent SD; solid lines represent the global fitting of the mixed inhibition model.

For 2,6-diCl-Pu and 6-BnS-Pu, the non-competitive inhibition model is sufficient to describe the data (Figure 2) properly, and the inhibition constants were found to be (22.2 ± 1.4) µM and (7.9 ± 0.4) µM, respectively, showing that benzylthio substituent at position 6 replacing the chlorine atom, enhances the interaction of the purine analogue with the enzyme.

In the case of the 6BnO-2Cl-Pu, a mixed inhibition model is necessary to describe the data obtained, and fitting of this model (Figure 3, left panel) yielded the competitive inhibition constant Kic = (18.3 ± 7.3) µM and the uncompetitive inhibition constant Kiu=(4.6 ± 0.5) µM (alpha = Kiu/Kic=0.25 ± 0.12). The same model is the best in the case of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr (Figure S4, right panel), and the appropriate parameters fitted are Kic=(6.2 ± 2.4) µM and uncompetitive inhibition constant Kiu=(2.9 ± 0.5) µM (alpha = Kiu/Kic=0.47 ± 0.24) suggesting that sulphate atom replacing oxygen atom at position 6, acting as a linker between purine ring and benzyl ring, has a positive effect yielding stronger inhibition. To confirm this, we repeated the experiment with guanosine as a substrate undergoing phosphorolysis (Figure S4, left panel), and the respective parameters describing inhibition were found to agree in the 3σ test (Table 2).

6BnS-2Cl-Pu (Figure 3, right panel) turned out to be the strongest inhibitor, and the uncompetitive model gives Kiu=(1.8 ± 0.2) µM, but this and the mixed inhibition model have almost the same probability. Since the solution of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu in methanol partially precipitated upon adding to the reaction mixture (prepared in water), the data points obtained for the inhibitor concentration higher than 6 µM (6.48 and 9.72 µM, not shown) were excluded from the global fit. Therefore, the inhibition is probably a mixed type, but the poor solubility of the compound precludes measurements with higher inhibitor concentration, which could help to distinguish between models. Mixed type inhibition by such type of compounds was also previously reported for the E. coli PNP22, which is very similar to the H. pylori PNP20,21,42.

Inhibition of H. pylori cell culture

Encouraged by the fact that some of the tested compounds turned out to be relatively potent inhibitors of PNP from the H. pylori 26695 strain, we decided to check the effect of these compounds on the proliferation of cell cultures of this bacterium. We started with 2,6-diCl-Pu, which is well soluble in water. We have found that it is effective in inhibiting H. pylori 26695 strain proliferation, but the MIC necessary to stop bacteria cell culture growth is rather high, 473 µg/mL, which corresponds to 2.5 mM (Figure S5, Table 3).

Due to the benzyl ring at position 6, the four other compounds studied are not well soluble in water but in organic compounds like, for example, methanol or DMSO. Methanol is too volatile to be used in such an assay. Therefore, we first checked the impact of DMSO on H. pylori 26695 strain growth, and we observed that DMSO at a concentration up to 2.5% (v/v) inhibits the growth of H. pylori only slightly (Figure S5). Therefore, when examining the effect of DMSO-soluble compounds on the growth of H. pylori, we did not exceed the latter concentration of this solvent, and we always included DMSO in each experiment for direct comparison (see Materials and methods).

When the stocks of 6BnO-2Cl-Pu, 6BnS-Pu, 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, and 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr in DMSO were diluted with water to obtain appropriate concentrations, all four compounds were partially precipitated, so we decided to investigate in parallel the effect of (i) the solution of the partially precipitated compounds, and (ii) their supernatants obtained by filtering of the former (see Materials and methods). The actual concentration of the inhibitors in the supernatants was determined by performing UV spectra of several times diluted supernatants, and the absorbance at 261 nm (maximum) in the case of 6BnO-2Cl-Pu, 290 nm in the case of 6BnS-Pu and 299 nm (maximum) in the case of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9 dr, was used to calculate the concentration of the tested compound, and these data are shown in Table S1. It was noticed that for the higher planned concentrations a significant part of each compound precipitated out of the solution, so the actual concentrations of the obtained supernatants turned out to be much lower than intended.

The maximal tested concentration of the fully dissolved 6BnO-2Cl-Pu was 0.095 mM. It inhibits but not completely only by about 35%, the growth of H. pylori 26695 strain (Figure S5, Table 3). However, if the partially precipitated solution was used, an inhibition about 75% was observed, with 6BnO-2ClPu prepared as 0.35 mM but partially precipitated (Table 3). These results suggest that the bacteria uptake the dissolved inhibitor, and the precipitated solid material is gradually dissolved to maintain the equilibrium.

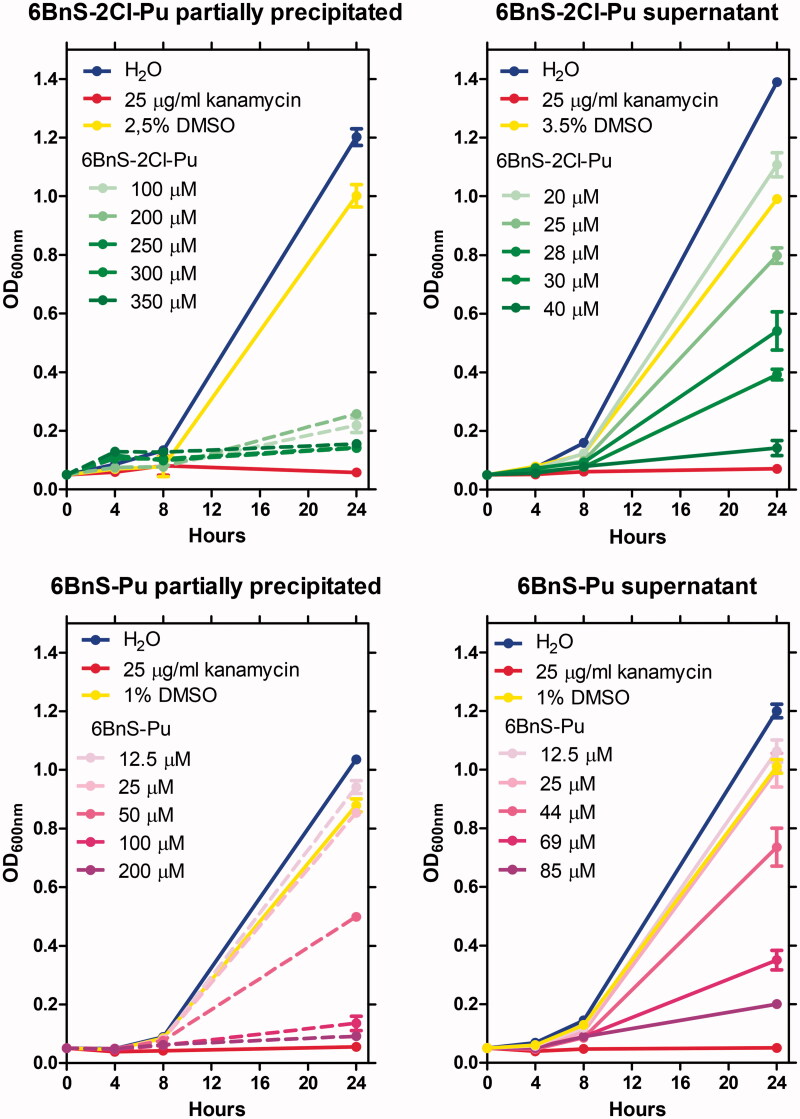

Even more promising results were obtained with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, for which the maximal tested concentration of the fully dissolved compound, 0.040 mM, yielded 92% inhibition of H. pylori 26695 cell culture growth, while the solution prepared as 0.25 mM but partially precipitated, led to the full inhibition (Figure 4, Table 3).

Figure 4.

Growth curves of H. pylori 26695 strain in the presence of various concentrations of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu (upper panels) and 6BnS-Pu (lower panels). Left panels – effects of partially precipitated stocks of the inhibitors, hence the actual concentration of dissolved inhibitor is lower. Right panels – effect of filtered stocks (supernatants). The effect of stocks (supernatants) of the particular tested compound (left panels), and the respective filtered solution of these stocks (right panels) are marked with the same colour, with the dashed and solid lines, respectively.

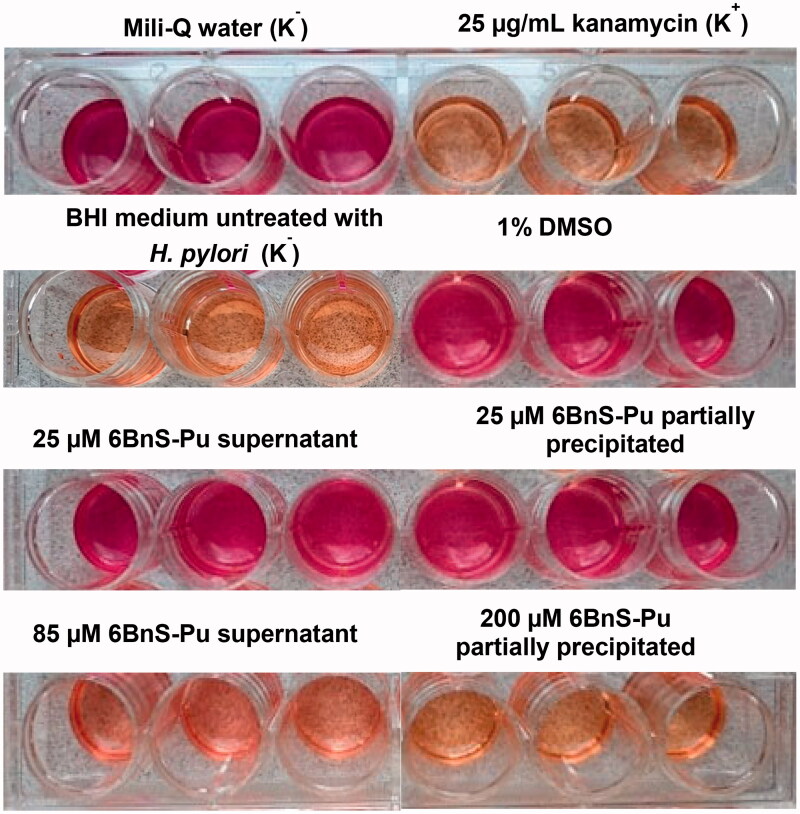

The maximal tested concentration of the fully dissolved 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr was 10.8 µM (see Table S1). The compound in this concentration has a very small effect on bacterial growth. However, with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr prepared as 200 µM but partially precipitated, complete inhibition of H. pylori 26695 strain growth is observed (Figure S5, Table 3). Moreover, prepared as 200 µM but partially precipitated 6BnS-Pu completely inhibited the growth of H. pylori 26695 strain, while the maximal concentration of the fully dissolved 6BnS-Pu (85 µM) yielded 83% inhibition (Figures 4 and 5, Table 3).

Figure 5.

Colour change examples observed in the Christensen’s test (see Materials and methods) in wells with H. pylori 26695 strain incubated in the presence of various concentrations of 6BnS-Pu. K+ indicates a positive control (25 µg/mL of kanamycin) and K− indicate negative controls as described. The results are presented for three repetitions.

The above results show that the investigated compounds can inhibit H. pylori cell culture growth. The urease test with the Christensen’s urea broth confirms that monitored H. pylori cells were viable (see the example of such data (Figure 5)).

The best PNP inhibitor, 6BnS-2Cl-Pu almost completely stops bacterial growth (by 92%, hence comparable to MTZ and kanamycin, see Table 3) at 40 µM concentration, maximal to obtain in given conditions. Complete growth inhibition occurs when 0.25 mM solution is used. However, at this concentration, the inhibitor partially precipitates, and while the dissolved material penetrates into bacterial cells, the present solid material maintains the equilibrium concentration of the dissolved inhibitor at the maximum possible level, which appears to be sufficient to arrest the growth of H. pylori cell culture (Figure 4, Table 3).

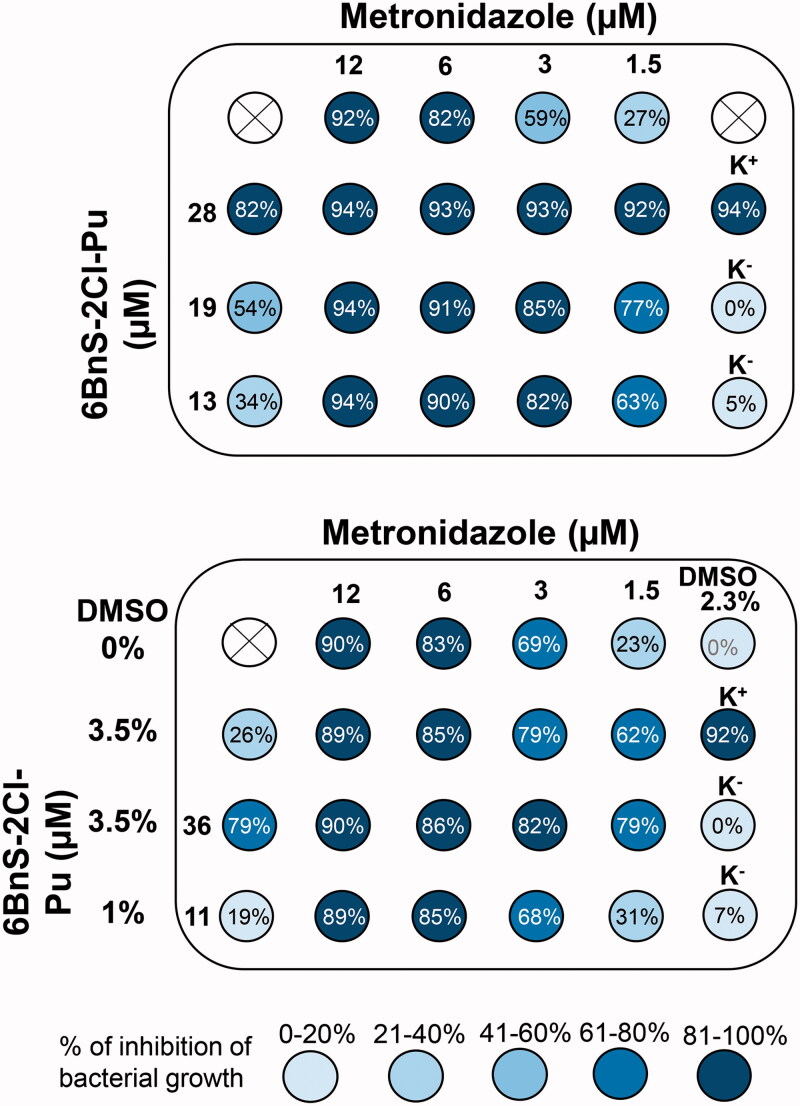

Combined antimicrobial effect of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and metronidazole

We have performed the checkerboard test with the most promising PNP inhibitor, 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, with one of the antimicrobials used in anti H. pylori therapies, MTZ, to check possible additive or synergistic effects of this combination. Data displayed in the upper panel of Figure 6 suggest an additive effect of MTZ and 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, because FICI determined based on this data (taking MIC of MTZ 2 µg/mL and MIC for 6BnS-2Cl-Pu 11.1 µg/mL, see Table 3) is 0.83, hence between 0.5 and 1.0. However, as the solution of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu contains DMSO (typically 1% per 3 µg/mL of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, maximum was 3.5%), the effect of MTZ solution containing 3.5% DMSO (Figure 6 lower panel, second row), and DMSO alone, 3.5% and 2.3% was also checked. Lower DMSO concentration, 2.3% does not affect H. pylori cell culture growth, while 3.5% yields 26% inhibition. Therefore FICI might be actually higher, and it is possible that the combined effect of MTZ and 6BnS-2Cl-Pu is neutral (FICI in the range 1.0–4.037), not additive.

Figure 6.

The antibacterial effects of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, metronidazole (MTZ), and combination of both against H. pylori 26695 strain replication. As solution of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu contains DMSO (typically roughly 1% per 3 µg/mL of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, maximum used was 3.5%), the effect of MTZ solution containing 3.5% DMSO (lower panel, second row), and DMSO alone, 3.5% and 2.3% were also checked. Lower DMSO concentration, 2.3% does not affect H. pylori cell culture growth, while 3.5% in this case yields 26% inhibition. The percent inhibition of bacterial growth is described in each well. The white circles with a cross in the middle indicate empty wells, K+ indicates a positive control (kanamycin 25 µg/mL) and K− indicate negative controls with water (upper) and BHI medium untreated with H. pylori cells (lower). The results are presented as the mean of three repetitions.

Although the poor solubility in water of purines substituted with a benzyl ring makes some problems determining MIC, the effects of these compounds on the proliferation of H. pylori cell cultures are very encouraging. To check how interactions with the target enzyme may be improved, we have determined the X-ray structure of H. pylori PNP complexes with the four purine analogues described above.

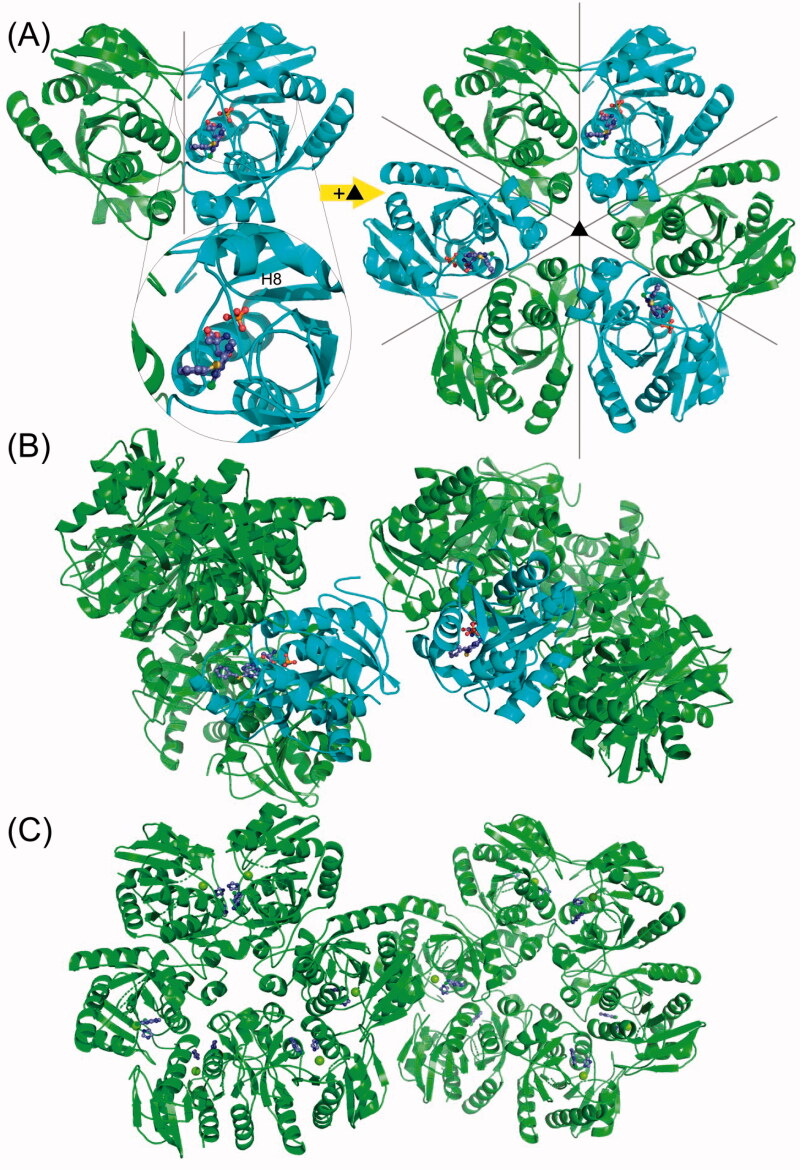

Structure of the H. pylori PNP complexes with 2,6-substituted purines

The PNP from H. pylori is a homo-hexamer consisting of six identical chains, each having 233 amino acids. The monomers in the hexamer are paired into three dimers, connected by a 2-fold symmetry operation passing between monomers. The complete hexamer is generated by a 3-fold symmetry axis perpendicular to the plane of the hexamer and to the 2-fold axis. Both symmetries can be approximate or exact, in which case they coincide with the crystallographic symmetry axis. Overall, this means that the enzyme molecules possess an approximate or exact symmetry of the point group 32. Thus, complexes with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and 6BnO-2Cl-Pu crystallise in the cubic space group P 21 3 and the asymmetric unit of the crystal is a dimer (Table 1). The whole hexamer is generated by the crystallographic 3-fold axis and possesses an exact 3-fold symmetry (Figure 7(A)).

Figure 7.

The overall structure of the H. pylori PNP complexes with 2,6-substituted purines. (A) Complexes with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and 6BnO-2Cl-Pu crystallise in the cubic space group P 213 with two monomers forming a dimer in the asymmetric unit. One of the monomers has the closed (shown in cyan) and one has the open (shown in green) conformation of the active site. The helix which is segmented to close the active site pocket (see text) is designated H8. The complete hexamer is generated by a crystallographic 3-fold axis, and therefore one hexamer has three open and three closed active sites. Ligands are shown in the ball and stick model. (B) In the crystals of PNP with 6BnS-Pu, two entire hexamers are in the asymmetric unit in the space group P 212121, and each hexamer (shown in cyan) has one closed active site. The closed active sites from different hexamers are next to each other in the crystal packing. (C) Complex of PNP with 2,6-diCl-Pu crystallised also with two hexamers in the asymmetric unit but this time in the P 1 space group. All the monomers are in the open conformation.

On the other hand, complexes with compounds 6BnS-Pu and 2,6-diCl-Pu crystallise in such a way that the asymmetric unit comprises two hexamers, in the orthorhombic P 212121 and triclinic P 1 space group, respectively (Table 1). This propensity of PNPs to crystallise in various space groups with highly different symmetries is known and has been described previously20,43. Indeed, the asymmetric unit of the crystal can comprise anything from a single monomer to three hexamers42.

The monomers themselves are made of a central part with parallel β-sheets surrounded by eight α-helices of varying lengths21. Each monomer has one active site located in the cavity close to the terminal α-helix H8 (Figure 7(A)). The active site is completed from one side by the residues His4 and Arg43 from the neighbouring monomer in the dimer. Helix H8 can be in two conformational states: elongated and segmented, which correspond to the open and closed conformation of the active site. The segmentation of the α-helix H8 occurs around residue Phe219, which undergoes a conformational change, and the last two turns of the helix H8 close the active site pocket20,21.

The active site in each monomer consists of parts that bind phosphate, pentose, and purine base. The phosphate-binding site is found in the most buried part of the active site, where the phosphate molecule is coordinated by three arginine residues, Arg24, Arg87 from one monomer, and Arg43 from the neighbouring monomer in the dimer. Phosphate molecule is further coordinated with hydrogen bonds to Gly20 and Thr90. Adjacent to the phosphate-binding part is the pentose-binding part surrounded by residues: Arg87, Thr90, Met64, Met180, and Glu181.

Binding of 2,6-substituted purines in the H. pylori PNP active site

In all closed active sites, inhibitor, phosphate, and buffer molecules are present (Tris or imidazole in the case of the structure with 2,6-diCl-Pu). In some of the structures, faint blobs of electron density in the open active sites are also observed, suggesting that in some protein molecules ligands are bound in these sites as well.

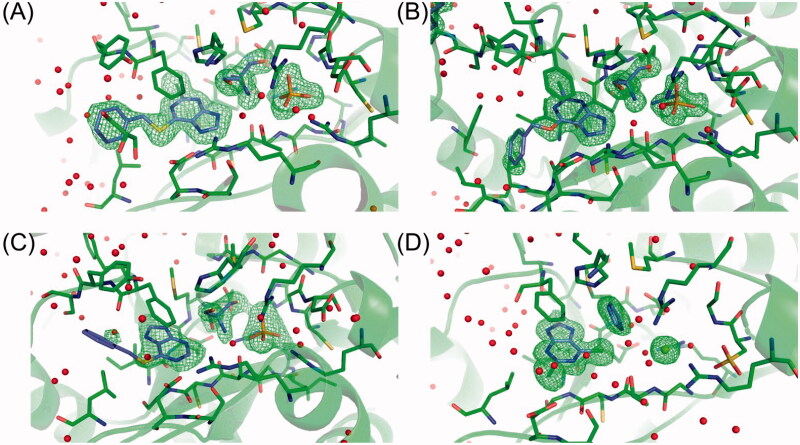

Details of ligand binding in the closed active sites of all four structures obtained are shown in Figure 8. The electron density in the closed active site of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu structure shows the presence of the ligand in the base binding part of the active site, and one molecule of Tris bound in the pentose binding part and a molecule of PO4. The phenyl arm is positioned towards the exit of the active site and above the plane of the purine base part (Figure 8(A)). 6BnO-2Cl-Pu shows an analogous way of binding as far as the planar base part is concerned. The difference is in the phenyl arm, which in the case of 6BnO-2Cl-Pu is positioned below the planar ring of the purine base. The positions of Tris and PO4 molecules are the same as in the previous structure (Figure 8(B)).

Figure 8.

Comparison of closed active sites in all four structures of H. pylori PNP with (A) 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, (B) 6BnO-2Cl-Pu, (C) 6BnS-Pu, and (D) 2,6-diCl-Pu. C atoms of the ligands are shown in violet, protein C atoms in green, and all other atoms in the CPK colours. The figure shows the electron mFo-DFc difference map density contoured at 3σ level (shown in green). Electron density only around molecules bound in the active sites is shown. Red spheres represent water molecules, and the green sphere on panel (D) – magnesium atom (from crystallisation mother liquor, see text).

Two other purines, 6BnS-Pu and 2,6-diCl-Pu, the former lacking chlorine atoms and the latter lacking the benzyl substituent, bind with a purine ring flipped around with respect to the two previous structures (Figure 8). The electron density of the phenyl arm in the structure of 6BnS-Pu is very poorly visible due to its large conformational mobility. Positions of Tris and PO4 molecules are the same as in the structures with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and 6BnO-2Cl-Pu. 2,6-diCl-Pu, which contains two Cl atoms, is very well defined in all twelve open active sites (chain A is shown in Figure 8). In the pentose binding part, one molecule of imidazole is visible and in the place of PO4, there is one Mg ion coordinated by water molecules and by Arg43. In all active sites, Cys19 is oxidised to cysteic acid (OCS) visible to the far right (Figure 8(D)).

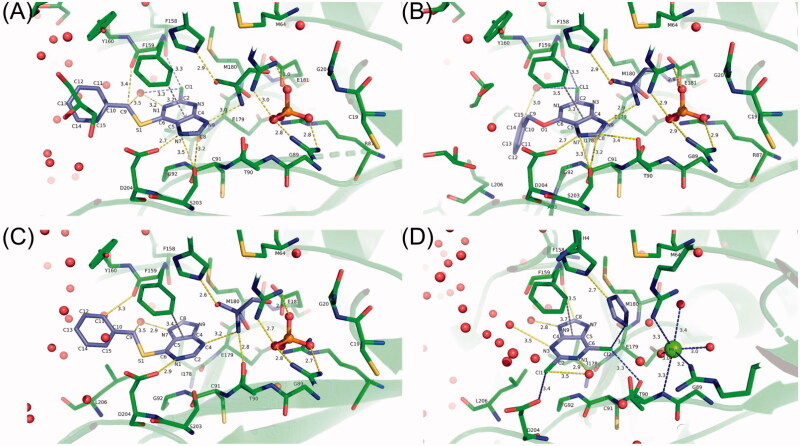

The most important interactions of the protein with ligands, namely, hydrogen bonds, classic and weak, involving carbon, close contacts, and C-H…π interactions are presented in Figure 9 and Table 4. In all four structures, Phe159 is placed on top of the pyrimidine ring and tilted approximately 45 degrees with respect to the ring plane. The distance from the closest atom to the centre of the C4-C5 bond ranges from 3.2 to 3.7 Å, which is characteristic for C-H…π interaction. Two purine ligands with the best inhibitor properties, namely, 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and 6BnO-2Cl-Pu (Table 2), form two strong hydrogen bonds with the protein, N7…Oδ1(Asp204) and N7…Oγ(Ser203). In two other enzyme structures, with weaker inhibitors, 6BnS-Pu and 2,6-diCl-Pu, the purine ring is flipped around, so the above contacts are impossible. 6BnS-Pu, the medium inhibitor (Table 2), forms one strong hydrogen bond N1…Oδ1(Asp204), while in the complex with the weakest inhibitor, 2,6-diCl-Pu, Asp204 is displaced by the Cl1 atom of the ligand and no strong hydrogen bonds are observed. Hence, the interactions observed in all four structures correlate with the inhibition properties of the ligands.

Figure 9.

The most important interactions of the protein with ligands in the H. pylori PNP complexes with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu (A), 6BnO-2Cl-Pu (B), 6BnS-Pu (C), and 2,6-diCl-Pu (D). Interactions of ligands under 3.5 Å in length are depicted, hydrogen bonds are shown in yellow, close contacts in blue, and C-H…π interactions are shown in grey. It is visible that in structures with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and 6BnO-2Cl-Pu purine ring is oriented in such a way that the five-membered ring is closer to the viewer, while in the two remaining structures the purine ring is flipped.

Table 4.

Hydrogen bonds (marked in bold) and close contacts shorter than 3.5 Å between ligands and active sites residues, observed in structures obtained in this study.

| 6BnS-2Cl-Pu | 6BnO-2Cl-Pu | 6BnS-Pu | 2,6-diCl-Pu | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N7…204(ASP)OD1 | 2.67 | N7…204(ASP)OD1 | 2.68 | N1…204(ASP)OD1 | 2.87 | N9…756(HOH)O | 2.78 |

| N9…302(TRS)N | 3.04 | N9…302(TRS)N | 2.94 | N7…215(HOH)O | 2.90 | N1…663(HOH)O | 2.86 |

| N1…192(HOH)O | 3.16 | C15…100(HOH)O | 2.99 | C11…942(HOH)O | 3.18 | Cl2…2(IMD)N1 | 3.15 |

| C8…203(SER)OG | 3.23 | C8…203(SER)OG | 3.22 | C11…159(PHE)O | 3.26 | Cl2…90(THR)O | 3.28 |

| CL1…158(PHE)O | 3.28 | CL1…158(PHE)O | 3.27 | N3…301(TRS)N | 3.27 | Cl2…204(ASP)OD2 | 3.36 |

| CL1…192(HOH)O | 3.34 | N7…203(SER)OG | 3.31 | C9…159(PHE)O | 3.28 | N3…2451(HOH)O | 3.51 |

| C9…159(PHE)O | 3.38 | C8…90(THR)OG1 | 3.38 | C9…215(HOH)O | 3.48 | C8…158(PHE)O | 3.53 |

| C9…192(HOH)O | 3.44 | CL1…100(HOH)O | 3.49 | Cl1…663(HOH)O | 3.53 | ||

| N7…203(SER)OG | 3.47 | ||||||

| C8…204(ASP)OD1 | 3.51 | ||||||

Atom numbering is given in Scheme S2 in the Supplemental Materials.

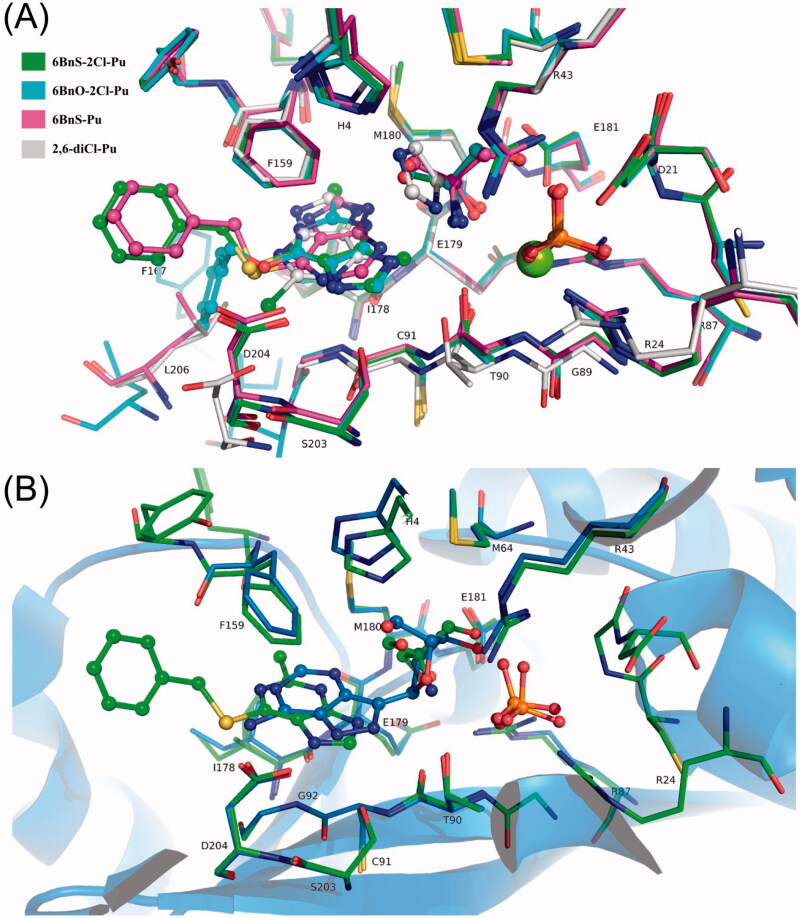

The upper panel of Figure 10 presents the overlapped positions of all four ligands in the structures of H. pylori PNP complexes studied in this report. In the figure legend, the similarities and differences of ligand binding are summarised. The lower panel of this figure compares H. pylori PNP complex with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, Tris, and PO4 obtained in this study, to the complex with formycin A and PO4 (PDB code 6F4X) described previously20. Formycin A is the analogue of PNP substrate, adenosine, and exhibits medium competitive vs. nucleoside substrate inhibitor properties, as its inhibition constant is 14.0 ± 1.7 µM20. It can be noted that in both structures, with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and with formycin A, the base rings are oriented in the same way, but are slightly tilted, and formycin A is more drawn into the active site because of the covalent bond with the ribose. The molecule of Tris is mimicking the ribose of formycin A with oxygen atoms occupying similar positions. This shows that sufficiently big substituents at positions 2 and 6 of the base secure the proper base orientation in the active site, allowing strong hydrogen bonds with Asp204 and Ser203. However, more space and freedom between the base and the pentose ring, or a base and a molecule mimicking the pentose, are necessary to allow the formation of such bonds and at the same time also strong interaction with the pentose part of the active site. These observations may be used to design nucleoside-like inhibitors, which may also be regarded as bisubstrate inhibitors of the reverse synthetic reaction direction (see reaction scheme in the Introduction). Such compounds may profit from better optimised interactions with the base and pentose binding sites, resulting in most probably stronger binding than observed in the case of formycin and the best inhibitors described in this study.

Figure 10.

(A) Overlapped positions of ligands in H. pylori PNP complexes with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu, 6BnO-2Cl-Pu, 6BnS-Pu, and 2,6-diCl-Pu. The colour codes of C atoms are shown in the legend, and other atoms have their standard colours. It is visible that the purine ring occupies the base binding pocket. Ligands 6BnS-2Cl-Pu and 6BnO-2Cl-Pu have the plane of the ring almost in the identical position, with the chlorine atoms pointing away from the viewer, although their benzyl arms are positioned oppositely. The pentose binding part of the active site is occupied by Tris molecules in all structures except for imidazole in the structure with 2,6-diCl-Pu. It can be noted that two imidazole nitrogen atoms are positioned close to the positions of one oxygen and one nitrogen atom of Tris molecule to favour hydrogen bond contacts. The phosphate molecules in all structures occupy the same place and are in the same orientation, while in the structure with 2,6-diCl-Pu a highly coordinated Mg atom is located in this position. It is visible that in the structure with 2,6-diCl-Pu the second chlorine atom of the ligand displaces the Asp204 side chain. (B) Overlap of the structure with 6BnS-2Cl-Pu (green) and with formycin A and PO4 (PDB code 6F4X, shown in blue). It can be noted that the base rings are oriented in the same way but are slightly tilted and shifted in relation to each other with formycin A located deeper in the active site because of the covalent bond with the ribose. The molecule of Tris is mimicking the ribose part of formycin A with oxygen atoms occupying similar positions.

Conclusion

In this study, we have shown that some purines substituted at positions 2 and/or 6 are effective inhibitors of H. pylori PNP, having inhibition constants in the low μM range as well as inhibiting H. pylori cell culture growth. Compound with a benzylthio substituent at position 6 of the purine ring exhibits the best inhibition properties. We have determined the X-ray structure of H. pylori PNP complexes with each of the purine analogues described above and characterised details of the enzyme-ligand interactions. The strength of binding, characterised by the quality of the electron density maps and the number of contacts with the enzyme are in line with the inhibition properties. These data provide an excellent starting point for designing bisubstrate analogue inhibitors that feature an additional part attached to the 2,6-substituted purine ring, capable of interacting with the pentose-binding site as well. Altogether, we have demonstrated that this class of compounds, based on a novel molecular mechanism and targeting the crucial enzyme in the H. pylori purine salvage pathway, provides a promising lead structure for designing drugs against this severe pathogen.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to the late prof. Zygmunt Kazimierczuk from Warsaw University of Life Sciences for the kind gift of 6BnS-2Cl-Pu-9dr, to Dr. Katarzyna Bocian-Ostrzycka and Dr. Magdalena Grzeszczuk from Department of Bacterial Genetics, Institute of Microbiology, Faculty of Biology, University of Warsaw, for assistance in developing conditions for H. pylori growth in the liquid medium. The authors are also grateful to MSc. Alicja Dyzma and MSc. Natasza Gajda from the Division of Biophysics, Institute of Experimental Physics, Faculty of Physics, University of Warsaw, for the invaluable help in the first stages of this project, and for the excellent technical assistance in the determination of inhibition constants; to MSc. Alicja Dyzma also for the help in the checkerboard assay experiments. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Nicola Demitri for the assistance during synchrotron measurements at Elettra.

Funding Statement

Supported from the project Harmonia 2015/18/M/NZ1/00776 granted by the National Science Centre of Poland, partially also from the project 2018/29/B/NZ1/00140, from the Polish Ministry for Science and Higher Education 501-D111-01-1110102, and from the University of Warsaw project IDUB PSP-501-D111-20-0004316. Experiments conducted in Ruđer Bošković Institute in Zagreb were supported by the Croatian Science Foundation [under the project numbers IP-2013-11-7423 and IP-2019-04-6764]. Some experiments were performed in the Laboratory of Biopolymers, ERDF Project POIG.02.01.00-14-122/09.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Marshall BJ, Warren JR.. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet 1984;1:1311–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makola D, Peura DA, Crowe SE.. Helicobacter pylori infection and related gastrointestinal diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol 2007;41:548–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson K, Atherton JC.. The spectrum of Helicobacter-mediated diseases. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 2021;16:123–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falco MDE, Lucariello A, Iaquinto S, et al.. Molecular mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis. J Cell Physiol 2015;230:1702–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cover TL. Helicobacter pylori diversity and gastric cancer risk. mBio 2016;7:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georgopoulos S, Papastergiou V.. An update on current and advancing pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of H. pylori infection. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2021;22:729–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Freitas LC. WHO (2017) Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. Cad Pesqui 2013;43:348–65. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roszczenko-Jasińska P, Wojtyś MI, Jagusztyn-Krynicka EK.. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the post-antibiotics era-searching for new drug targets. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2020;104:9891–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campestre C, De Luca V, Carradori S, et al.. Carbonic anhydrases: new perspectives on protein functional role and inhibition in Helicobacter pylori. Front Microbiol 2021;12:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ullman B, Carter D.. Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase as a therapeutic target in protozoal infections. Infect Agents Dis 1995;4:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Kouni MH. Potential chemotherapeutic targets in the purine metabolism of parasites. Pharmacol Ther 2003;99:283–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Koning HP, Bridges DJ, Burchmore RJS.. Purine and pyrimidine transport in pathogenic protozoa: from biology to therapy. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2005;29:987–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyde JE. Fine targeting of purine salvage in cryptosporidium parasites. Trends Parasitol 2008;24:336–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg M, Van der Veken P, Goeminne A, et al.. Inhibitors of the purine salvage pathway: a valuable approach for antiprotozoal chemotherapy? Curr Med Chem 2010;17:2456–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans GB, Tyler PC, Schramm VL.. Immucillins in infectious diseases. ACS Infect Dis 2018;4:107–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liechti G, Goldberg JB.. Helicobacter pylori relies primarily on the purine salvage pathway for purine nucleotide biosynthesis. J Bacteriol 2012;194:839–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Il’icheva IA, Polyakov KM, Mikhailov SN.. Strained conformations of nucleosides in active sites of nucleoside phosphorylases. Biomolecules 2020;10:552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koellner G, Luić M, Shugar D, et al.. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of E. coli purine nucleoside phosphorylase with formycin B, a structural analogue of the substrate inosine, and phosphate (sulphate) at 2.1 A resolution. J Mol Biol 1998;280:153–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narczyk M, Bertoša B, Papa L, et al. Helicobacter pylori purine nucleoside phosphorylase shows new distribution patterns of open and closed active site conformations and unusual biochemical features. FEBS J 2018;285:1305–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Štefanić Z, Mikleušević G, Luić M, et al.. Structural characterization of purine nucleoside phosphorylase from human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Int J Biol Macromol 2017;101:518–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bzowska A, Magnowska L, Kazimierczuk Z.. Synthesis of 6-aryloxy- and 6-arylalkoxy-2-chloropurines and their interactions with purine nucleoside phosphorylase from Escherichia coli. Z Naturforsch C 1999;54:1055–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones JW, Robins RK.. Purine nucleosides. III. Methylation studies of certain naturally occurring purine nucleosides. J Am Chem Soc 1963;85:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schrader WP, Stacy AR, Pollara B.. Purification of human erythrocyte adenosine deaminase by affinity column chromatography. J Biol Chem 1976;251:4026–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bzowska A, Kazimierczuk Z, Seela F.. 7-deazapurine 2'-deoxyribofuranosides are noncleavable competitive inhibitors of Escherichia coli purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP). Acta Biochim Pol 1998;45:755–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bzowska A, Kazimierczuk Z.. 2-Chloro-2'-deoxyadenosine (cladribine) and its analogues are good substrates and potent selective inhibitors of Escherichia coli purine-nucleoside phosphorylase. Eur J Biochem 1995;233:886–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalckar HM, Shafran W.. Differential spectrophotometry of purine compounds by means of specific enzymes; Determination of hydroxypurine compounds. J Biol Chem 1947;167:429–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulikowska E, Bzowska A, Wierzchowski J, Shugar D.. Properties of two unusual, and fluorescent, substrates of purine-nucleoside phosphorylase: 7-methylguanosine and 7-methylinosine. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)/Protein Struct Mol 1986;874:355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bzowska A, Kulikowska E, Shugar D.. Properties of purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) of mammalian and bacterial origin. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci 1990;45:59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segel IH, Enzyme kinetics: behavior and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady-state enzyme systems. Vol. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley Sons; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Copeland RA, Enzymes. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irie Y, Tateda K, Matsumoto T, et al.. Antibiotic MICs and short time-killing against Helicobacter pylori: therapeutic potential of kanamycin. J Antimicrob Chemother 1997;40:235–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chowers MY, Keller N, Tal R, et al. Human gastrin: a Helicobacter pylori-specific growth factor. Gastroenterology 1999;117:1113–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knezevic P, Aleksic Sabo V, Simin N, et al. A colorimetric broth microdilution method for assessment of Helicobacter pylori sensitivity to antimicrobial agents. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2018;152:271–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krzyżek P, Franiczek R, Krzyżanowska B, et al.. In vitro activity of 3-bromopyruvate, an anticancer compound, against antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant Helicobacter pylori strains. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.EUCAST . Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 11.0, 2021. Available from: http://www.eucast.org.

- 37.Pillai SK, Eliopoulos GM, Moellering RC. Antimicrobial combinations. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2005:365–409. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2010;66:125–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vagin A, Teplyakov A.. MOLREP: an automated program for molecular replacement. J Appl Crystallogr 1997;30:1022–5. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liebschner D, Afonine PV, Baker ML, Bunkóczi G, et al.. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in phenix. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 2019;75:861–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrödinger LLC . The {PyMOL} molecular graphics system, Version∼1.8. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mikleušević G, Štefanić Z, Narczyk M, et al.. Validation of the catalytic mechanism of Escherichia coli purine nucleoside phosphorylase by structural and kinetic studies. Biochimie 2011;93:1610–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luić M, Štefanić Z.. Can crystal symmetry and packing influence the active site conformation of homohexameric purine nucleoside phosphorylases? Croat Chem Acta 2016;89:197–202. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.