Abstract

The Mycobacterium bovis P55 gene, located downstream from the gene that encodes the immunogenic lipoprotein P27, has been characterized. The gene was identical to the open reading frame of the Rv1410c gene in the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, annotated as a probable drug efflux protein. Genes similar to P55 were present in all species of the M. tuberculosis complex and other mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium avium. By Western blotting, P55 was located in the membrane fraction of M. bovis. When transformed into Mycobacterium smegmatis after cloning, P55 conferred aminoglycoside and tetracycline resistance. The levels of resistance to streptomycin and tetracycline conferred by P55 were decreased in the presence of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone and the pump inhibitors verapamil and reserpine. M. smegmatis cells expressing the plasmid-encoded P55 accumulated less tetracycline than the control cells. We conclude that P55 is a membrane protein implicated in aminoglycoside and tetracycline efflux in mycobacteria.

Tuberculosis is the world's leading cause of mortality owing to an infectious bacterial agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The estimated 8.8 millions new cases every year have an extraordinary impact on the economies of the developing world, where most of the cases occur (30). Short-course chemotherapy (with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and streptomycin being the backbones of treatment) is the most powerful weapon available against infection with susceptible strains of M. tuberculosis, breaking the chain of transmission and limiting contagion.

Recently, dramatic outbreaks caused by multidrug-resistant strains (defined as those resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin) of M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis have focused international attention (25, 30). These cases are extremely difficult to cure, and the necessary treatment is much more toxic and expensive.

In recent years, considerable work has been done on the characterization of drug-resistant mycobacteria. That work has identified structural or metabolic genes (encoding either the enzymes that activate antimycobacterial drugs or the protein targets of drug action) that lead to a high level of resistance to a single drug when the genes are altered by mutation. In most cases, multidrug-resistant isolates have accumulated independent mutations in several genes (21, 22, 26). However, these mutations do not account for all resistant strains, indicating that other mechanisms confer resistance in mycobacteria.

In bacteria, the permeability of the membrane and the actions of active transport mechanisms prevent access of certain drugs to the intracellular targets. These constitute a general mechanism of drug resistance capable of conferring resistance to a variety of structurally unrelated drugs and toxic compounds (12, 16, 17, 19, 24). The resistance efflux systems are characteristically energy dependent, either from the proton motive force or through the hydrolysis of ATP.

Recently, efflux-mediated resistance and efflux pumps that confer resistance to one or several compounds have been described in mycobacteria (2, 4, 7, 9, 14, 29). The genome of M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv has 20 open reading frames encoding putative efflux proteins (8), although most of them have not yet been characterized.

In the work described here, we functionally characterized the putative multidrug efflux pump P55 from M. bovis (in which it was initially described [5, 6]) and M. tuberculosis (since P55 is identical to the product of the Rv1410c gene of the M. tuberculosis H37Rv genome [8]). We have found that P55 confers resistance to tetracycline and aminoglycosides such as streptomycin and gentamicin. The effect of pump inhibitors on the resistance levels conferred by P55 has been also studied. P55 forms a operon with P27, which we have previously identified and characterized as a gene that encodes a lipoprotein antigen from M. bovis (5, 6).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture media, and growth conditions.

M. tuberculosis H37Rv, M. bovis BCG, Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2 155 (27), Escherichia coli DH5α, and derivatives of these strains were used (Table 1). Media were obtained from Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.). Luria-Bertani (LB) broth was used to culture E. coli and was supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 to culture the M. smegmatis strains. Kanamycin A (Sigma) was added at 20 μg/ml to maintain the plasmids for E. coli and mycobacterial species, and ampicillin was added at 100 μg/ml for E. coli. Mueller-Hinton agar plates were used for antibiotic susceptibility testing, and LB broth was used for microdilution tests. All the cultures were incubated at 37°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in the present work

| Strain, plasmid, or oligonucleotide | Characteristic | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| M. smegmatis mc2155 | Efficient plasmid transformation mutant | 27 |

| M. smegmatis PAZ22 | M. smegmatis mc2155 carrying plasmid pPAZ22 | This work |

| M. smegmatis PAZ23 | M. smegmatis mc2155 carrying plasmid pPAZ23 | This work |

| M. smegmatis PAZ24 | M. smegmatis mc2155 carrying plasmid pPAZ24 | This work |

| M. smegmatis PAZ100 | M. smegmatis mc2155 carrying plasmid pSUM41 | This work |

| M. smegmatis PAZ101 | M. smegmatis mc2155 carrying plasmid pMV261 | This work |

| Plasmid | ||

| pMV261 | HygrE. coli-Mycobacterium shuttle vector | 28 |

| pSUM41 | KmrE. coli-Mycobacterium shuttle vector | 1 |

| pPAZ22 | pMV261 with P55 gene | This work |

| pPAZ23 | pSUM41 with P27-P55 operon | This work |

| pPAZ24 | pPAZ23 with omega cassette Smr in BamHI site | This work |

| pGEM-T | E. coli cloning vector | Promega |

| pRSET-A | E. coli expression vector | Invitrogene |

| pRSET-vec | pRSET-A with P55 gene | This work |

| pMAL-c | E. coli expression vector | New England Biolabs |

| pMAL-vec | pMAL-c with P55 gene | This work |

| Oligonucleotide | ||

| vec21-up | CCGGATCCCGAGCAGGACGTCGAGTCGCGATa | This work |

| vec21-low | GCGAATTCGGCTCGTTAGAGCGGCTCCACTTGb | This work |

| 2-1 dir | CCTCACAGACACCCTCTACG | This work |

| U292 | CGTTCCTCAACAATTCCG | This work |

The boldface indicates the BamHI restriction site.

The boldface indicates the EcoRI restriction site.

DNA manipulations.

Standard methods were used for DNA manipulations (3). Plasmid DNA isolation was performed with a Wizard Minipreps SV kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Both E. coli and M. smegmatis mc2 155 were transformed by electroporation (18) with a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. Richmond, Calif.).

Plasmid construction.

To clone P55 under the control of the hsp60 promoter, the gene was amplified by PCR with chromosomal DNA from M. bovis BCG as a template with primers 2-1Dir and vec21-low (Table 1). The PCR product was digested with BamHI and EcoRI and was cloned into the vector pMV261 (28), resulting in plasmid pPAZ22. The region containing the P27-P55 operon was amplified by PCR with primers U292 and vec21-low. The resulting 2.2-kb fragment was cloned in the pGEM-T vector (Promega), excised with EcoRI, blunt ended with the Klenow enzyme, and inserted in the blunt-ended BamHI site of pSUM41 (1), resulting in plasmid pPAZ23. The streptomycin resistance omega cassette (20) was inserted in the BamHI site of pPAZ23 (internal to P27 gene), resulting in pPAZ24.

To construct a plasmid for expression of the P55 gene in E. coli, the coding sequence was amplified with primers vec21-up and vec21-low, which provide BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites, respectively (Table 1). The resulting 1.6-kb fragment was cloned between the BamHI and EcoRI sites of plasmid pRSET-A (Invitrogene), generating pRSET-vec in which P55 is fused at the N terminus with a polyhistidine tag. The insert of pRSET-vec was excised with BamHI and HindIII and was cloned into pMAL-c (New England Biolabs), generating pMAL-vec, in which P55 has an N-terminal fusion with malE.

Preparation of anti-P55 sera in rabbits.

Since the production of recombinant P55 from pMAL-vec was stronger than that from pRSET-vec, we used E. coli pMAL-vec crude extracts as the source of recombinant P55. A total of 100 mg of E. coli pMAL-vec crude extract was loaded in a 10-cm-wide well and developed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Using Western blotting, we determined the region of the gel where the recombinant protein was located. The gel strip containing P55 was excised, mashed, mixed with Freund incomplete adjuvant, and injected in three doses into one rabbit in order to obtain antibodies against P55. The doses were given at 2-week intervals.

Preparation of crude extracts, fractionation, and Western blotting.

Crude extract preparations from mycobacteria, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and Western blotting were performed as described previously (6). A peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody was used for Western blotting, and bands were developed with the chemiluminescence ECL plus Western blotting detection system kit (Amersham). Sonication and centrifugation were used to fractionate M. bovis crude extracts into the membrane and cytosolic fractions. Membrane fractions were further fractionated by Triton X-114 extraction.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

The susceptibilities of M. smegmatis mc2155 derivatives containing the plasmids described above to the following drugs were tested: tetracycline, aminoglycosides (2′-N-ethylnetilmicin, 6′-N-ethylnetilmicin, netilmicin, tobramycin, gentamicin), quinolones (nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin), sulfadiazine, chloramphenicol, cefoxitin, erythromycin, minocycline, sulfamethoxazole, ethidium bromide, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), and the antituberculosis drugs streptomycin, isoniazid, ethionamide, rifampin, and ethambutol.

Initially, the antibiotic diffusion method was used to screen the drugs. Then, the MICs of those drugs for the strains that contained P55 and that presented any resistance were determined by the Alamar Blue assay (11), which was repeated at least three times.

The MICs of streptomycin and tetracycline were also determined under the same conditions in the presence of the following inhibitors of efflux pumps: CCCP (5 mM), verapamil (100 mM), and reserpine (20 mM).

Assay of tetracycline accumulation.

The accumulation of tritiated tetracycline (American Radiolabelled Chemicals Inc., St. Louis, Mo.) was monitored as described previously (2, 14) in a liquid scintillation counter (LS-6000 IC; Beckman).

Computer analysis.

Information on Rv1410c was obtained from the TubercuList database (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/). Sequence databases were searched by using the program BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Unfinished genomes of Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium avium were searched at The Sanger Centre (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_leprae/) and The Institute for Genomic Research (http://www.tigr.org/cgi-bin/BlastSearch/blast.cgi?organism=m_avium), respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Database searches and motifs in P55.

The P55 gene from M. bovis was identical to the Rv1410c gene from M. tuberculosis (8). Database searches showed that the P55 protein had a high level of similarity to membrane efflux proteins of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) of proteins (19) involved in antibiotic transport or resistance from other bacteria (Table 2). Several motifs characteristic of the drug transporters of the MFS (17, 19) are present in the sequence of P55. A motif present in all members of the MFS was found between residues 66 and 78 of P55 (GRASDRFGRKLML). Another motif was found between residues 104 and 116 (LIAGRTIQGVASG). Between residues 148 and 162 (LGSVLGPLYGIFIVW) there was a motif specific for all drug-proton antiporters; other motifs characteristic of the drug-antiporters with 14 transmembrane segments were present from residues 21 to 31 (LDTYVVVTIMR), 167 to 178 (WRDVFWINVPLT), and 202 to 208 (DLVGGLL).

TABLE 2.

Amino acid sequence identity between the deduced product of the P55 gene and other proteins

| Protein | Organism | % Identitya | Description | Accession no. (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv1410c | M. tuberculosis | 100 | Probable drug resistance protein | CAB02189 (8) |

| SC9C7.19 | Streptomyces coelicolor | 40 | Probable efflux protein | CAA22731 |

| DRA0061 | Deinococcus radiodurans | 38 | Putative drug transport protein | AAF12254 |

| Mdr | Bacillus subtilis | 36 | Multidrug-efflux transporter | CAB12101 |

| Otrb | Streptomyces rimosus | 35 | Tetracycline efflux protein | AAD04032 |

| Rv1877 | M. tuberculosis | 32 | Similar to drug efflux protein | CAB10049 (8) |

| Rv0783c | M. tuberculosis | 24 | Similar to multidrug resistance protein | CAB02373 (8) |

| LfrA | M. smegmatis | 23 | Proton antiporter efflux pump | AAC43550 (14, 29) |

The degree of identity was determined with the program BLAST.

Subcellular localization of the P55 protein.

According to a computer-based prediction included in the TubercuList database at the Institut Pasteur generated with the TMMF program, the product of Rv1410c (which is identical to M. bovis P55) contains 14 membrane-spanning domains (data not shown), strongly suggesting a membrane localization for this protein. In order to check this possibility, cell fractions from M. bovis crude extracts were prepared and probed by Western blotting with a specific anti-P55 rabbit serum. In the membrane fraction, a band of approximately 55 kDa was detected, which corresponds with the expected size of the P55 protein (Fig. 1A), whereas no band was detected in the cytoplasmic fraction. When the membrane fraction was extracted with the detergent Triton X-114, P55 remained with the detergent fraction. These results suggest that P55 is an integral membrane protein, in agreement with the computer-predicted membrane localization of P55.

FIG. 1.

Detection of P55 protein by Western blotting. (A) Different M. bovis BCG preparations: lane 1, total cell extract; lane 2, supernatant obtained after centrifugation at 100,000 × g; lane 3, detergent phase of Triton X-114 fractionation; lane 4, pellet obtained after centrifugation at 100,000 × g. (B) Cell extracts from different mycobacterial species: lane 1, M. smegmatis; lane 2, M. avium: lane 3, M. chelonae; lane 4, M. phlei; lane 5, M. gordonae; lane 6, M. microti; lane 7, M. fortuitum; lane 8, M. tuberculosis. The sizes of the proteins (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

Presence of P55 in other mycobacterial species.

The anti-P55 rabbit serum was used in Western blotting assays against cell extracts from several mycobacteria. Bands of approximately 55 kDa were detected in unfractionated cell extracts of M. smegmatis, M. avium, Mycobacterium chelonae, Mycobacterium phlei, Mycobacterium gordonae, Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium fortuitum, and M. tuberculosis (Fig. 1B). By PCR with oligonucleotides vec21-low and 2-1dir, genes similar to P55 were detected in M. microti (in agreement with the results of Western blotting) and Mycobacterium africanum (data not shown). Also, genes similar to P55 were detected in the unfinished genomes of M. avium (in agreement with the results of Western blotting) and M. leprae through database searches. Therefore, since P55-like genes or P55-like proteins have been detected in fast and slow growers and in pathogenic and nonpathogenic species, it is likely that all species of the genus Mycobcterium have similar genes.

Resistance levels and substrate profile.

To study the involvement of P55 in antibiotic efflux, two plasmids containing the P55 gene were analyzed. In pPAZ22, P55 was cloned in pMV261 under the control of the hsp60 promoter; in pPAZ23, the operon (P27 and P55) with its natural promoter was cloned in pSUM41. M. smegmatis carrying each construct (and the vectors as controls) was tested against a series of antibiotics and chemicals. Both plasmid pPAZ22 and plasmid pPAZ23 produced 8-fold increases in the MICs of tetracycline and streptomycin, 4-fold increases in the MICs of gentamicin, and 16-fold increases in the MICs of 2′- and 6′-N-ethylnetilmicin compared with the MICs for the control strains containing pMV261 and pSUM41 (Table 3). (The levels of resistance to the other compounds tested were unaffected by the presence of the plasmid-encoded P55 gene. We cannot exclude the possibility that P55 may also transport other substances apart from antibiotics.) Therefore, these increases in the resistance to antibiotics reflect the expression of the P55 gene from both plasmids, suggesting that the P55 protein may act as a drug efflux pump that confers resistance to multiple drugs in M. smegmatis. Active efflux involving antituberculosis drugs has not been unambiguosly shown to cause resistance in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, as it has been demonstrated in fast-growing mycobacteria (2, 4, 7, 9, 14, 29). Previously described putative efflux pumps from M. tuberculosis failed to confer resistance to any particular drug (10), or only low-level resistance to tetracycline could be detected (2).

TABLE 3.

MICs of different antibiotics for M. smegmatis strains

| Compound | MIC (μg/ml) for M.

smegmatis strain:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PAZ101 | PAZ22 | PAZ23 | |

| 2′-N-Ethylnetilmicin | 4 | 64 | 64 |

| 6′-N-Ethylnetilmicin | 4 | 64 | 64 |

| Gentamicin | 2 | 8 | 8 |

| Streptomycin | 0.5 | 4 | 4 |

| Tetracycline | 0.5 | 4 | 4 |

It is worth noting that P55 conferred resistance to streptomycin, one of the first-line drugs used in the treatment of tuberculosis. It has been reported that 30% of the streptomycin-resistant M. tuberculosis clinical isolates do not carry any mutation in the rpsL and the rrs genes (see references 21, 22, and 26 and references therein). A possible explanation for the levels of resistance to streptomycin in these strains could be an increase in the activity of M. tuberculosis P55 or any other streptomycin transporter. Future work will be carried out in order to test the activity of P55 in the streptomycin-resistant M. tuberculosis strains carrying wild-type rrs and rpsL genes.

Apart from resistance to streptomycin, P55 also confers resistance to other aminoglycosides, such as gentamicin and 2′- and 6′-N-ethylnetilmycin. The M. fortuitum Tap efflux pump was also associated with aminoglycoside resistance (2). Both proteins are members of the MFS family of transporters. Other efflux pumps related to aminoglycoside resistance have been identified in the resistance-nodulation-division family (RDN) of proteins, for example, E. coli AcrD (23).

Effect of pump inhibitors on resistance.

Because of the sequence similarity to proton-drug antiporters and the associated phenotype of multidrug resistance, we considered the possibility that P55 may act as a proton-dependent efflux pump. In order to test this hypothesis, we used the energy uncoupler CCCP, which disperses the proton gradient across the bacterial membrane, thus affecting the activities of the proton-dependent efflux pumps (12). Specific inhibitors of efflux pumps, verapamil and reserpine, were also tested since it has been shown that exposure of bacteria to substances that inhibit efflux systems produces an increase in susceptibility to antibiotics (7, 15). The MICs of streptomycin and tetracycline were determined in the presence and in the absence of these compounds (Table 4). The use of CCCP, verapamil, and reserpine produced a decrease in the MICs of both streptomycin and tetracycline for strain PAZ22 (which expresses P55 from plasmid pPAZ22), whereas the resistance levels of the control strain, PAZ101 (which contains the vector pMV261), were not changed (Table 4). These results indicate that the resistance levels produced by P55 are sensitive to both inhibitors of efflux pumps and substances that eliminate the proton gradient across membranes, suggesting that it is quite likely that P55 uses the energy from the proton gradient to drive the transport of the antibiotics.

TABLE 4.

MICs for M. smegmatis strains in the presence of various inhibitors

| Compound | MIC (μg/ml) for M. smegmatis:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PAZ101 | PAZ22 | |

| Streptomycin | 0.5 | 4 |

| Streptomycin + CCCP | 0.5 | 1 |

| Streptomycin + verapamil | 0.5 | 1 |

| Streptomycin + reserpine | 1 | 2 |

| Tetracycline | 0.5 | 4 |

| Tetracycline + CCCP | 0.5 | 1 |

| Tetracycline + verapamil | 0.5 | 2 |

| Tetracycline + reserpine | 0.5 | 2 |

Reserpine and verapamil reduced the MICs for PAZ22 to levels similar to those detected in the presence of CCCP. This is an important fact, suggesting that substances other than ionophores could be used to inhibit efflux pumps and improve the activities of antibiotics in the treatment of resistant clinical isolates, as has been proposed elsewhere (15).

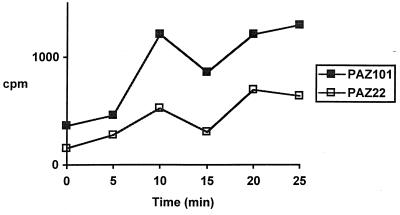

Tetracycline accumulation assays.

Since tetracycline is one of the substrates of the P55 efflux pump, we studied tetracycline accumulation in M. smegmatis PAZ22 (in which P55 is expressed under the control of the hsp60 promoter) and M. smegmatis PAZ101 as a control. The time course of tetracycline accumulation (Fig. 2) showed that PAZ101 accumulated more tetracycline than PAZ22, indicating that P55 is capable of extruding tetracycline from M. smegmatis.

FIG. 2.

Time course of tetracycline accumulation for M. smegmatis PAZ101 control cells (■) and M. smegmatis PAZ22 cells (□) expressing plasmid-encoded P55 gene.

Is P55 modulated by P27?

In the genomes of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, the P27 and P55 genes form an operon and both genes are transcribed from the operon promoter (5). We tested plasmid pPAZ24, which has the streptomycin resistance omega cassette inserted in the P27 gene, therefore preventing transcription of P55 from the operon promoter. pPAZ24 conferred to M. smegmatis the same levels of resistance to 2′-N-ethylnetilmicin, 6′-N-ethylnetilmicin, and gentamicin as the parental pPAZ23 did, although the levels of resistance to tetracycline were slightly lower (data not shown). This finding suggests that P55 may have a promoter in the ca. 390 nucleotides between the cassette and the P55 start codon.

Some bacteria have drug-sensor proteins that induce the expression of an associated efflux pump. In these cases, genes encoding the drug sensor and the efflux pump are located adjacent to each other (13). Since lipoproteins have been suggested to have a role in signal transduction (A. J. C. Steyn, J. Joseph, and B. R. Bloom, Abstr. ASM Conference on Tuberculosis: Past, Present and Future, abstr. 119, 2000), an interesting hypothesis suggests that the P27 protein could be a kind of sensor of specific signals (i.e., the presence of drugs) that would activate, either directly or indirectly, the expression of the P55 gene. Further experiments will be carried out in order to test the role of P27 in the putative modulation of P55 activity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria 00/1170 and the European Union (grant QLK2-CT-2000-01761). P.E.A.S. is a professor of the Fundaçaõ Universidade Federal do Rio Grande (FURG) and was supported by CAPES, Ministério de Educação de Brasil. A.C., M.I.R., and F.B. are fellows of the National Research Council of Argentina (CONICET). Both laboratories are members of the Red Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Tuberculosis (RELACTB).

We thank Sofia Samper for critical reading of the manuscript and Isabel Otal for helpful discussion and experimental advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aínsa J A, Martín C, Cabeza M, De la Cruz F, Mendiola M V. Construction of a family of Mycobacterium/Escherichia coli shuttle vectors derived from pAL5000 and pACYC184: their use for cloning an antibiotic resistance gene from Mycobacterium fortuitum. Gene. 1996;176:23–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aínsa J A, Blokpoel M C J, Otal I, Young D B, DeSmet K A L, Martín C. Molecular cloning and characterization of Tap, a putative multidrug efflux pump present in Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5836–5843. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5836-5843.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates, Inc., and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee S K, Bhatt K, Misra P, Chakraborti P K. Involvement of a natural transport system in the process of efflux-mediated drug resistance in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Gen Genet. 2000;262:949–956. doi: 10.1007/pl00008663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bigi F, Alito A, Romano M I, Zumarraga M, Caimi K, Cataldi A. P27 lipoprotein and a putative antibiotic resistance gene form an operon in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis. Microbiology. 2000;146:1011–1018. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-4-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bigi F, Espitia C, Alito A, Zumarraga M, Romano M I, Cravero S, Cataldi A. A novel 27kDa lipoprotein antigen from Mycobacterium bovis. Microbiology. 1997;143:3599–3605. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-11-3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhuri B S, Sen S, Chakrabarti P. Isoniazid accumulation in Mycobacterium smegmatisis modulated by proton motive force-driven and ATP-dependent extrusion systems. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256:682–684. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosisfrom the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Rossi E, Blokpoel M C J, Cantoni R, Branzoni M, Riccardi G, Young D B, De Smet K A L, Ciferri O. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of a novel tetracycline resistance determinant, tet(V), from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1931–1937. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doran J L, Pang Y, Mdluli K E, Moran A J, Victor T C, Stokes R W, Mahenthiralingam E, Kreiswirth B N, Butt J L, Baron G S, Treit J D, Kerr V J, van Helden P D, Roberts M C, Nano F E. Mycobacterium tuberculosis efpAencodes an efflux protein of the QacA transporter family. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:23–32. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.1.23-32.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franzblau S G, Witzig R S, McLaughlin J C, Torres P, Madico G, Hernandez A, Degnan M T, Cook M B, Quenzer V K, Ferguson R M, Gilman R H. Rapid, low-technology MIC determination with clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosisisolates by using the microplate Alamar Blue assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:362–366. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.362-366.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy S B. Active efflux mechanisms for antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:695–703. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.4.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis K. Multidrug resistance: versatile drug sensors of bacterial cells. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R403–R407. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Takiff H E, Nikaido H. Active efflux of fluoroquinolones in Mycobacterium smegmatismediated by LfrA, a multidrug efflux pump. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3791–3795. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3791-3795.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markham P N. Inhibition of the emergence of ciprofloxacin resistance in Streptoccocus pneumoniaeby the multidrug efflux inhibitor reserpine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:988–989. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikaido H. Multiple antibiotic resistance and efflux. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:516–523. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pao S S, Paulsen I T, Saier M H., Jr Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parish T, Stocker N G. Electroporation in mycobacteria. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;101:129–144. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-471-2:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paulsen I T, Brown M H, Skurray R A. Proton-dependent mutidrug efflux systems. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:575–608. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.575-608.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prentki P, Krisch H. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramaswamy S, Musser J M. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;79:3–29. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1998.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rattan A, Kalia A, Ahmad N. Multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: molecular perspectives. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:195–209. doi: 10.3201/eid0402.980207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg E Y, Ma D, Nikaido H. AcrD of Escherichia coliis an aminoglycoside efflux pump. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1754–1756. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1754-1756.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saier M H, Jr, Paulsen I T, Sliwinski M K, Pao S S, Skurray R A, Nikaido H. Evolutionary origins of multidrug and drug-specific efflux pumps in bacteria. FASEB J. 1998;12:265–274. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samper S, Martín C, Pinedo A, Rivero A, Blázquez J, Baquero F, van Soolingen D, van Embden J. Transmission between HIV-infected patients of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis. AIDS. 1997;11:1237–1242. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sander P, Böttger E C. Mycobacteria: genetics of resistance and implications for treatment. Chemotherapy (Basel) 1999;45:95–108. doi: 10.1159/000007171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snapper S B, Melton R E, Mustafa S, Kieser T, Jacobs W R., Jr Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1911–1919. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stover C K, De la Cruz V F, Fuerst T R, Burlein J E, Benson L A, Bennet L T, Bansal G P, Young J F, Lee M H, Hatfull G H, Snapper S B, Barletta R G, Jacobs W R, Jr, Bloom B R. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Science. 1991;351:456–460. doi: 10.1038/351456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takiff H E, Cimino M, Musso M C, Weisbrod T, Martínez R, Delgado M B, Salazar L, Bloom B R, Jacobs W R., Jr Efflux pump of the proton antiporter family confers low-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:362–366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]