Abstract

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a vascular pathology with high prevalence among the aging population. PAD is associated with decreased cognitive performance, but the underlying mechanisms remain obscure. Normal brain function critically depends on an adequate adjustment of cerebral blood supply to match the needs of active brain regions via neurovascular coupling (NVC). NVC responses depend on healthy microvascular endothelial function. PAD is associated with significant endothelial dysfunction in peripheral arteries, but its effect on NVC responses has not been investigated. This study was designed to test the hypothesis that NVC and peripheral microvascular endothelial function are impaired in PAD. We enrolled 11 symptomatic patients with PAD and 11 age- and sex-matched controls. Participants were evaluated for cognitive performance using the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery and functional near-infrared spectroscopy to assess NVC responses during the cognitive n-back task. Peripheral microvascular endothelial function was evaluated using laser speckle contrast imaging. We found that cognitive performance was compromised in patients with PAD, evidenced by reduced visual memory, short-term memory, and sustained attention. We found that NVC responses and peripheral microvascular endothelial function were significantly impaired in patients with PAD. A positive correlation was observed between microvascular endothelial function, NVC responses, and cognitive performance in the study participants. Our findings support the concept that microvascular endothelial dysfunction and neurovascular uncoupling contribute to the genesis of cognitive impairment in older PAD patients with claudication. Longitudinal studies are warranted to test whether the targeted improvement of NVC responses can prevent or delay the onset of PAD-associated cognitive decline.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Peripheral artery disease (PAD) was associated with significantly decreased cognitive performance, impaired neurovascular coupling (NVC) responses in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (LDLPFC and RDLPFC), and impaired peripheral microvascular endothelial function. A positive correlation between microvascular endothelial function, NVC responses, and cognitive performance may suggest that PAD-related cognitive decrement is mechanistically linked, at least in part, to generalized microvascular endothelial dysfunction and subsequent impairment of NVC responses.

Keywords: cognitive impairment, microvascular endothelial dysfunction, neurovascular coupling, peripheral artery disease

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a highly prevalent age-related cardiovascular disease that affects 10%–20% of people over 70 yr of age (1–3). PAD represents a considerable global public health problem that imposes an increasing burden on society (4), leads to poor quality of life (5), and is associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (6–10). PAD is characterized by the narrowing of arteries in the lower extremities due to atherosclerosis, which can be accompanied by a variety of symptoms, the most common being leg pain during ambulation (known as intermittent claudication) (11). A growing body of epidemiological and clinical studies suggest that PAD is also associated with pathological alterations in other vascular beds (3). Importantly, clinical evidence demonstrates that PAD is associated with decreased cognitive performance (12–18), increasing the risk for the development of vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) and dementia (19–21).

The potential mechanism contributing to the genesis of cognitive impairment in patients with PAD is not well understood and may involve decreased cerebral perfusion. It is possible that atherosclerotic lesions in larger cerebral arteries are one contributing factor to impaired cerebral perfusion, such as vessels constituting and originating from the circle of Willis at the base of the brain. Functional impairment in the cerebral microcirculation is another contributing factor, which may promote cognitive decline (12, 14, 22–28). Because energetic demands of neurons are high and the brain has very little reserve capacity, maintenance of normal brain function is critically dependent on moment-to-moment adjustment of local cerebral blood flow to match the metabolic needs of activated neurons (23). In response to neuronal activity, signaling between constituents of the corresponding neurovascular unit (pericytes, astrocytes, and endothelial cells adjacent to a given neuron) leads to the dilation of feeding cerebral microvessels (29). These mechanisms, collectively termed as neurovascular coupling (NVC), result in a marked hemodynamic change in response to the release and accumulation of vasoactive mediators. Therefore, NVC responses enable rapid increases in oxygen and glucose delivery to active brain regions via increased perfusion and thus play a vital role in homeostatic support of the neural function. NVC responses are mediated, at least in part, by endothelial production of vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) (30–33), and pathological conditions that promote endothelial dysfunction are known to impair NVC responses. Importantly, patients with PAD exhibit generalized microvascular dysfunction (34–39). Previous studies have demonstrated that atherosclerotic vascular disease is not limited only to large vessels, but extends to other vascular beds, including microvascular circulation (25, 40–43). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that systemic impairment of endothelial function in patients with PAD contributes to the dysregulation of local cerebral blood flow and the genesis of cognitive impairment.

The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that microvascular hemodynamic responses in the microcirculation of the skin and in the brain cortex are impaired in patients with PAD. To test our hypothesis, we enrolled patients with PAD and compared their peripheral microvascular endothelial function [laser speckle contrast imaging (LSCI)] and NVC responses [functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS)], elicited by the cognitive n-back test, to age- and sex-matched controls. We found significantly impaired NVC responses in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of patients with PAD and significant peripheral microvascular endothelial dysfunction. The association between microvascular endothelial function, NVC responses, and cognitive performance was analyzed.

METHODS

Study Design and Participant Characteristics

A total of 22 adults [11 participants with PAD, 63.7 ± 5.2 yr of age, 6 males (2 African Americans and 4 Caucasians) and 5 females (2 African Americans and 3 Caucasians); and 11 controls, 64.1 ± 7.6 yr of age, 6 males (all Caucasians) and 5 females (1 African American and 4 Caucasians); P = 0.88, means ± SD] were enrolled in this study. Patients with PAD were recruited through the Vascular Medicine Program, Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, and healthy controls were enrolled via advertisement. All study participants obtained at least a high school degree. All participants were assessed for cognitive performance and peripheral microvascular endothelial function. Out of 11 patients enrolled, 5 participants with PAD (62.0 ± 8.6 yr of age, 3 males and 2 females; means ± SD) consented to the NVC assessment with functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). In the interest of an unbiased statistical comparison, five age- and sex-matched (P = 0.82) participants were selected from the control group (60.8 ± 6.5 yr of age, 3 males and 2 females; means ± SD) to assess the impact of PAD on NVC responses. Although control participants reported that they had not been smoking ever or in the preceding 20 yr, everyone in the PAD group were smokers with no intention to quit during the study. Participating patients with PAD had an ankle-brachial index (ABI) of 0.9–0.4 and presented with claudication at a >200-m distance. Neither PAD nor controls had a previous diagnosis of cognitive impairment, had a history of stroke or major coronary events in the past 6 mo, or were hypertensive on the day of physiological assessments. Comorbidities of the participants are summarized in Table 1 and were well controlled at the time of visit. All participants were asked to refrain from drinking caffeinated beverages for at least 6 h before the assessments. All participants were right-handed.

Table 1.

Health conditions of the patients with PAD and control participants

| Health Conditions | PAD (n = 11) | Control (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 5/11 | 7/11 |

| Diabetes | 4/11 (3 type 2) | 1/11 (type 2) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 7/11 | 2/11 |

| Other conditions | Osteoarthritis (1), coxarthrosis (1), depression (2), reflux (1) | Osteoporosis (1), osteoarthritis (1), reflux (1) |

Comorbidities considered as potential confounders are reported for the peripheral artery disease (PAD) and control group. All participants with reported comorbidities were medically controlled by their physician: β-blockers/diuretics/calcium channel blockers for hypertension, insulin/metformin for diabetes, and statins for hypercholesterinemia.

All procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Written, informed consent was obtained from each participant before participation.

Cognitive Assessment

Different domains of cognition were assessed using a selection of tests from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB, Cambridge Cognition). The CANTAB Connect Research tool is a validated and sensitive tool optimized to detect signs of age-related cognitive impairment and mild cognitive decline(25). Testing started with a Motor Screening Task to determine the presence of any sensorimotor deficit, and then continued with the following tests: Reaction Time, Paired Association Learning, Delayed Matching Sample, Spatial Working Memory, Rapid Visual Processing, and Attention. Participants were left alone in a quiet environment during the test with the touchscreen device running the application.

Neurovascular Coupling Protocol with Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy

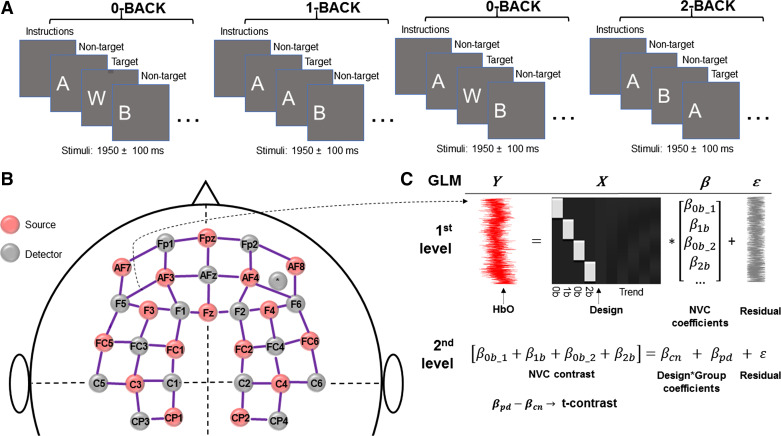

An n-back cognitive test was used to evoke NVC responses, as previously described (40). In brief, participants were seated in front of a computer monitor with their right hand on the mouse, and the n-back tasks were explained before the start of the paradigm, as well as during the task. Participants were instructed to perform to the best of their ability during each task, with 60 letters presented as stimuli during each task. The experimental design consisted of 0-back, 1-back, 0-back, and 2-back sessions during which they had to click only in case of the target stimulus. However, response to a nontarget stimulus (by clicking) was counted as an error (Fig. 1A). During 0-back, participants were asked to identify and respond to the letter “W” when presented on the screen with a left mouse button click. For the 1-back task, participants were asked to respond every time they saw two identical letters in a row (e.g., respond to second A and K sequences in A-A-B-C-K-K). For the 2-back task, the target stimulus was any letter that repeated itself two steps back (e.g., respond to a second letter B in A-A-B-C-B series). The n-back task requires monitoring, updating, and manipulating the information and is therefore assumed to place great demands on several key processes within working memory. The sequence of letters was randomized by the custom software developed in ePrime 3 (Psychology Software Tools, Sharpsburg, PA). The average block length was 134.13 ± 1.37 s.

Figure 1.

Experimental setup for neurovascular coupling (NVC) assessments. A: cognitive n-back task was implemented to evoke NVC responses in study participants. In brief, participants were presented with four tasks in the following order: 0-back, 1-back, 0-back, and 2-back. During 0-back, participants were asked to identify and respond to the letter “W” when presented on the screen with a left mouse button click. For the 1-back task, participants were asked to respond every time they saw two identical letters in a row (e.g., respond to second A in a sequence A-A-B). For the 2-back task, study participants were asked to respond when they saw any letter that repeated itself two letters back (e.g., respond to a second letter A in a sequence A-B-A). The average block length was 134.13 ± 1.37 s. B: NVC responses were assessed using the near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), NIRScout platform (NIRx Medical Technologies LLC, Glen Head, NY) equipped with 16 light sources and 16 detectors. To standardize optode placement, a 128-port Easycap head cap (Easycap GmbH, Woerthsee-Etterschlag, Germany) was positioned on the participant’s head by aligning its Fpz-Iz ports to the sagittal plane of the head and the optode in the Fpz position of the cap with Fpz on the participant. Hemodynamic responses were measured from 48 channels—defined by source-detector pairs with 3 cm separation according to the international 10-20 system—covering the prefrontal and motor cortex regions. C: fNIRS data were analyzed using a pipeline based on General Linear Model (GLM) approach created using the Brain AnalyzIR toolbox. At the individual (1st) level, regression coefficients (β-weights) were determined from the hemoglobin dynamics and the convolution of the design matrix with a canonical hemodynamic response function, indicating brain activation. Group-level (2nd) statistics (βpd and βcn; cn: control, pd: peripheral artery disease) were obtained by fitting a mixed-effect model β contrast. The model was defined in a Wilkinson–Rogers formula of “β ∼ −1 + Group +(1| Participant),” and its output was evaluated by a t-contrast of [pd-cn] for all cognitive n-back tests. For further details see main text. fNIRS, functional near-infrared spectroscopy; HbO, oxyhemoglobin.

For the fNIRS examination, we used a NIRScout platform (NIRx Medical Technologies LLC, Glen Head, NY) equipped with 16 light sources and 16 detectors. To standardize optode placement, a 128-port Easycap head cap (Easycap GmbH, Woerthsee-Etterschlag, Germany) was positioned on the participant’s head by aligning its Fpz-Iz ports to the sagittal plane of the head and the optode in the Fpz position of the cap with Fpz on the participant. Hemodynamic responses were measured from 48 channels—defined by source-detector pairs with 3 cm separation according to the international 10-20 system—covering the prefrontal and motor cortex regions (Fig. 1B). Measurements were performed in a quiet, dimly lit room.

Assessment of Peripheral Microvascular Endothelial Function

To measure endothelial function in skin microcirculation, we used a flow-mediated dilation approach (25). In brief, a sphygmomanometer cuff was placed above the left antecubital fossa, and after recording 60 s of stable baseline perfusion, occlusion was performed by inflating the arterial cuff to 50 mmHg above current systolic blood pressure for 5 min. After the release of cuff occlusion, vascular responses were recorded for 3 min using a Perimed PSI System (Perimed, Järfälla, Sweden). Skin temperature was measured with a noncontact thermometer (Thermoworks TW2) from less than 10 mm at the back of the hand and the first and last phalanx of the middle finger. We determined baseline perfusion and maximal postocclusive perfusion from the recordings.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

The impact of PAD on cognitive performance was assessed by unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney test after checking the normality of the data set with Shapiro–Wilk test.fNIRS data were analyzed using a pipeline based on General Linear Model (GLM) approach created using the Brain AnalyzIR toolbox (41). After the conversion of optical densities to change of hemoglobin concentration using the modified Beer–Lambert law (42), prewhitening of data with an autoregressive model-based algorithm, and a discrete cosine transformation using a high-pass filter (cutoff frequency: 0.0045 Hz), design matrices were convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function to predict brain activation. A mixed-effect model was fitted for group-level statistics using parameter estimates (β-weights) and scaling the predictors. The model was defined in a Wilkinson–Rogers formula of “β ∼ −1 + Group +(1 | Participant),” and its output was evaluated by a t-contrast of (PAD-Control) for the entire n-back test (i.e., contrast weights for each session was +1). Statistical significance was assumed for brain regions with a false discovery rate-corrected q < 0.05, according to the Benjamini–Hochberg method. A separate analysis was carried out for the channel between source AF3 and detector F5, which is located in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (a region specifically involved in the n-back task). Averaged change of oxyhemoglobin (HbO) and reduced hemoglobin (HbR) was compared between PAD and control participants by Student’s t test for the duration of the n-back tasks (Fig. 1C).

Assessment of peripheral microvascular endothelial function was based on maximal postocclusion perfusion (normalized to baseline perfusion), which was then analyzed via Student’s t test comparing responses from PAD and control participants after checking the normal distribution of the data set.

Finally, to evaluate the association between cognitive performance, NVC responses, and peripheral microvascular endothelial function, we determined an n-back accuracy index as a measure of working memory function, as it has been used as a cognitive stimulus to evoke NVC responses captured by fNIRS. The n-back accuracy index describes the ability of study participants to discriminate between target and nontarget stimuli. This parameter is defined as the difference between z-transform of hit-rate (correct responses to target stimuli/number of target stimuli) and z-transform of false alarm rate (incorrect responses to nontarget stimuli/number of nontarget stimuli), as previously described (43). In this study, we calculated the average of the n-back accuracy indices obtained for the 1- and 2-back sessions. The association between n-back accuracy index, NVC responses (mean β values across all the channels of the prefrontal cortex for all the n-back tasks), and microvascular endothelial function (maximal postocclusion perfusion, normalized to baseline perfusion) was performed using linear regression analysis, and correlation matrices were built using the Jamovi software (v. 1.6) (44, 45).

Figures were prepared using MATLAB 2019 b (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and GraphPad Prism (v. 9, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Tables were prepared using Jamovi software (46, 47). We report means ± SD for normally distributed variables, medians, and interquartile ranges otherwise.

RESULTS

PAD Alters Cognitive Performance

To assess cognitive performance, we used a battery of cognitive tests that has previously shown to be sensitive to age-related changes in healthy older adults free from dementia. All study participants were evaluated for performance in several domains of cognition, including psychomotor speed, attention, memory, executive function, and specifically, for reaction time, sustained attention, visual memory, short-term recognition, visual matching, and spatial working memory.

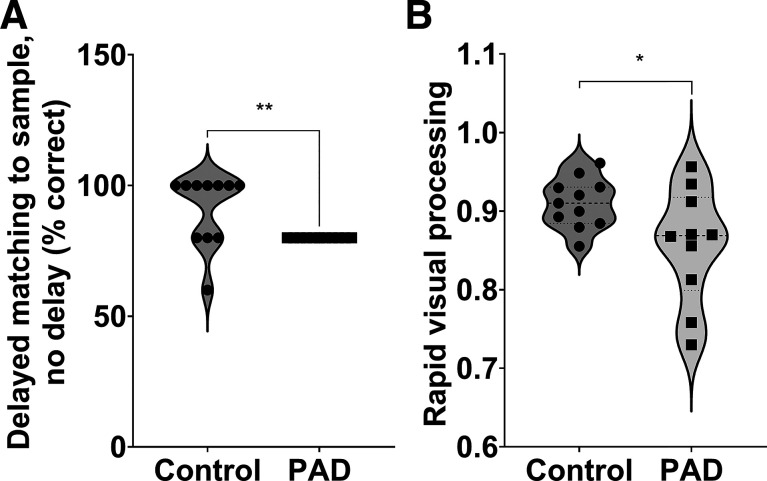

We observed significant group differences in the performance of a Delayed Matching to Sample test (Fig. 2A, median: 100, IQR: 80–100), indicating that PAD is associated with poorer short-term recognition performance in older adults, extending the results of previous studies (18). We also observed a significantly worse performance on a Rapid Visual Processing test in participants with PAD (Fig. 2B, means ± SD: 0.910 ± 0.0316), indicating that PAD is associated with lower levels of performance on tests of sustained attention and visual memory in older adults.

Figure 2.

PAD alters cognitive performance in older adults. A: we observed a significant decrease in the performance of delayed matching to sample test in participants with PAD versus controls, evidenced as a significantly lower percentage of correct responses with no delay (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.004, n = 11 per group). B: we also observed a significantly decreased performance in the rapid visual processing test (0 to 1 from poor to good performance; two-sample unpaired t test, P = 0.038, n = 11 per group) in participants with PAD compared with age- and sex-matched controls. PAD, peripheral artery disease.

PAD Impairs NVC Responses in Prefrontal Cortex during Cognitive n-Back Task

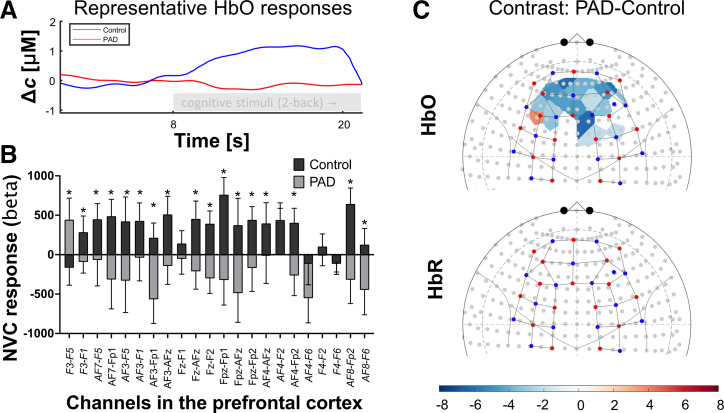

We measured hemodynamic NVC responses in the cerebral cortex during the cognitive n-back paradigm using the fNIRS approach. Our data demonstrate that PAD significantly impairs NVC responses during the n-back task when compared with healthy sex- and age-matched controls. We found that the distribution of oxyhemoglobin was significantly lower in participating patients with PAD when compared with healthy controls in the entire prefrontal cortex (see negative contrast values in blue-colored areas in Fig. 3A). The biggest change was localized to the prefrontal cortex (PFC), including the left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (LDLPFC and RDLPFC, respectively), brain regions involved in higher cognitive function, including attention, working memory, and inhibition of inappropriate responses. The β values from the channels of the PFC—including the left and right DLPFC—were averaged for control and participants with PAD and presented in Fig. 3B. No significant changes were observed for reduced hemoglobin between PAD and control groups during the cognitive task.

Figure 3.

PAD significantly impairs neurovascular coupling (NVC) responses during a cognitive task. A: representative oxyhemoglobin (HbO) curves are displayed for a randomly selected PAD patient (red) and control participant (blue), respectively. The underlying fNIRS recordings were acquired before and during 2-back task from a brain region (F3-FC3 channel) in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). B: group-level statistics β values from the prefrontal cortex (PFC), left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (LDLPFC and RDLPFC, respectively) were averaged for all n-back tasks in control and participants with PAD (n = 5 per group, *P < 0.05 vs. controls, means ± SD). C: fNIRS heatmap demonstrates the effect of PAD on the distribution of HbO/NVC responses measured in the cortical tissues during cognitive n-back task vs. healthy controls. β values of NVC responses of healthy controls during all cognitive tasks were subtracted from corresponding tasks of participants with PAD (contrast PAD-controls). Blue or red shaded areas highlight cortical zones with the significantly lower or higher distribution of HbO/NVC responses (false discovery rate-corrected q < 0.05 for multiple comparisons) and demonstrate that NVC responses in the highlighted regions of participants with PAD were significantly lower than in healthy age- and sex-matched controls (n = 5 per group). No significant difference in the reduced hemoglobin (HbR) was observed between the two groups. fNIRS, functional near-infrared spectroscopy; HbO, oxyhemoglobin; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

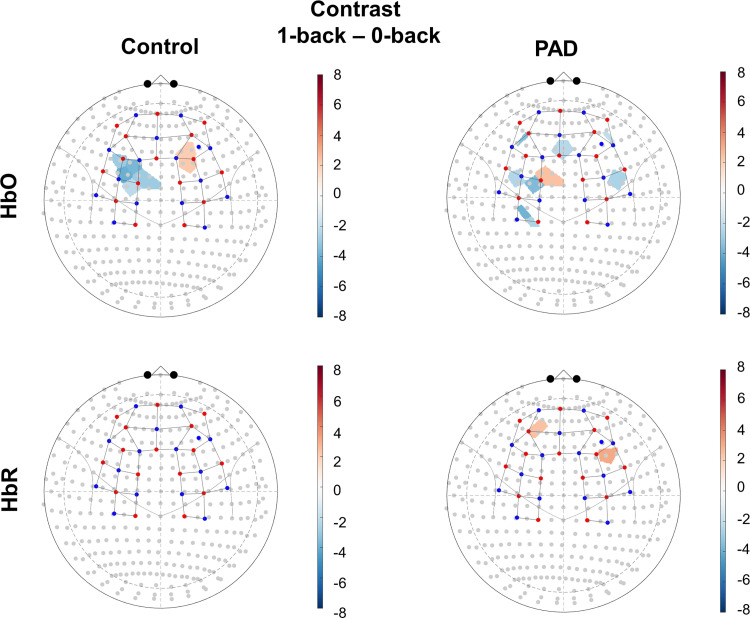

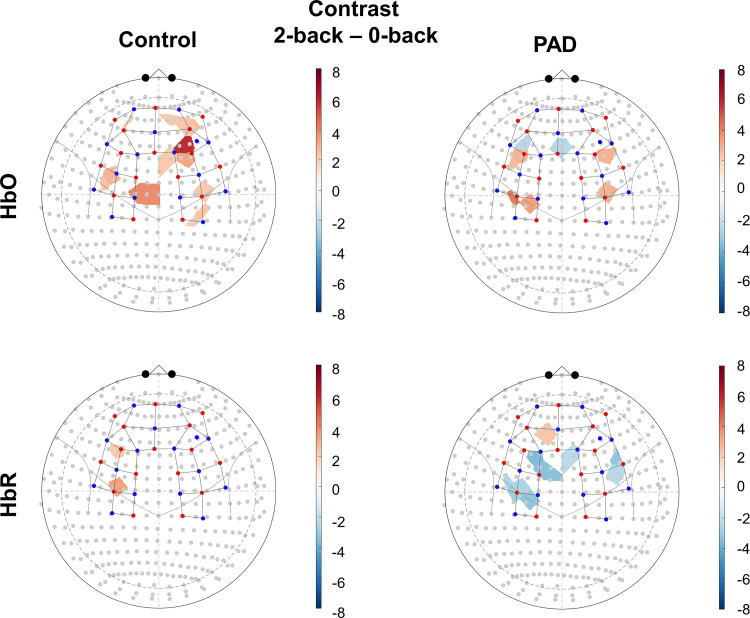

NVC responses evaluated separately for 1- and 2-back tasks normalized for baseline 0-back task, separately for PAD and control participants, are presented in Fig. A1 and Fig. A2.

PAD Impairs Peripheral Microvascular Endothelial Function

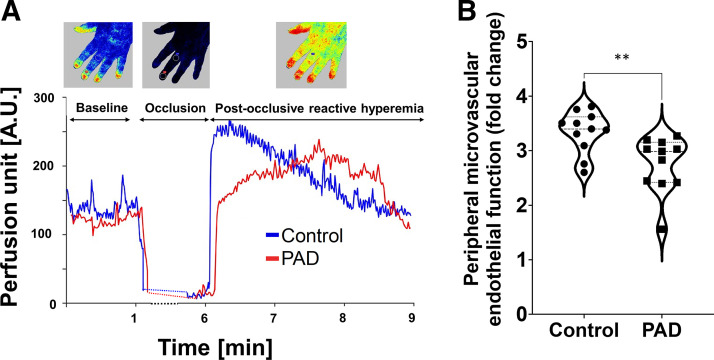

We measured microvascular endothelial function in the skin microcirculation of the hand in response to 5-min blood flow occlusion in the brachial artery using the LSCI approach (Fig. 4A). We found that patients with PAD had significantly impaired peripheral microvascular endothelial function, evidenced by a significantly reduced postocclusive reperfusion (maximal/baseline perfusion; P = 0.0065, Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

PAD significantly impairs peripheral microvascular endothelial function. A: representative recordings showing changes in microvascular perfusion in the left hand in response to occlusion and to a release of a 5-min blood flow restriction in the brachial artery of a participant with PAD (61-yr-old) and age- and sex-matched control participants. B: PAD significantly impaired microvascular endothelial function measured by maximal/baseline perfusion in the postocclusion period (Mann–Whitney test, P = 0.003, n = 11 per group). PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Association between Microvascular Endothelial Function, NVC Responses, and Cognitive Load

To study the association between cognitive performance, NVC responses, and peripheral microvascular endothelial function, we calculated the n-back accuracy index (average for 1- and 2-back tests), as it has been used to evoke NVC responses during fNIRS assessments. In control participants, we found a nonsignificant positive strong correlation between n-back accuracy index and NVC responses (r = 0.7), a nonsignificant positive weak correlation between n-back accuracy index and peripheral microvascular endothelial function (r = 0.2), and a nonsignificant positive strong correlation between NVC responses and peripheral microvascular endothelial function (r = 0.8) in control participants (Table 2). In patients with PAD, we observed a nonsignificant moderate positive correlation between n-back accuracy index and NVC responses (r = 0.4), nonsignificant moderate positive correlation between n-back accuracy index and peripheral microvascular endothelial function (r = 0.4), and a significant strong positive correlation between NVC responses and peripheral microvascular endothelial function (r = 0.9, P = 0.004, Table 3). These data suggest the association between NVC responses evoked by cognitive stimulation and peripheral microvascular endothelial function in the PAD group.

Table 2.

Cognitive load is associated with NVC responses and peripheral microvascular endothelial function in control participants

| Control Group (n = 5) | n-Back Accuracy Index (Mean) | fNIRS (β, Mean) |

|---|---|---|

| fNIRS (β, mean) | ||

| Pearson’s r | 0.708 | - |

| P value | 0.146 | - |

| Peripheral microvascular endothelial function | ||

| Pearson’s r | 0.233 | 0.843 |

| P value | 0.383 | 0.078 |

We found a nonsignificant strong positive correlation between n-back accuracy index and neurovascular coupling (NVC) responses (r = 0.70), nonsignificant positive weak correlation between n-back accuracy index and peripheral microvascular endothelial function (r = 0.23), and nonsignificant strong positive correlation between NVC responses and peripheral microvascular endothelial function (r = 0.84) in control participants (n = 5). fNIRS, functional near-infrared spectroscopy.

Table 3.

Cognitive load is associated with NVC responses and peripheral microvascular endothelial function in participants with PAD

| PAD Group (n = 5) | n-Back Accuracy Index (Mean) | fNIRS (β, Mean) |

|---|---|---|

| fNIRS (β, mean) | ||

| Pearson’s r | 0.422 | - |

| P value | 0.578 | - |

| Peripheral microvascular endothelial function | ||

| Pearson’s r | 0.422 | 0.996 |

| P value | 0.578 | 0.004 |

We observed a nonsignificant moderate positive correlation between n-back accuracy index and neurovascular coupling (NVC) responses (r = 0.4), nonsignificant moderate positive correlation between n-back accuracy index and peripheral microvascular endothelial function (r = 0.4), and a significant strong positive correlation between NVC responses and peripheral microvascular endothelial function (r = 0.9, P = 0.04) in peripheral artery disease (PAD) participants. These data suggest an association between NVC responses evoked by cognitive stimulation and peripheral microvascular endothelial function in the PAD group. fNIRS, functional near-infrared spectroscopy.

DISCUSSION

Cognitive decline has become a major healthcare burden in aging Western societies. It is recently recognized that vascular pathologies play a major role in the development of age-related cognitive decline and its progression to dementia (22). Relatedly, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have initiated the consortium aimed to promote scientific efforts in the understanding of vascular contributions to cognitive decline (https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-consortium-takes-aim-vascular-disease-linked-cognitive-impairment-dementia). However, the association between cerebromicrovascular pathologies with an accompanying neurovascular uncoupling and the increased prevalence of cognitive dysfunction observed in older adults is not fully understood.

With currently >8 million cases in the United States (48) and an exponentially increasing prevalence after the age of 60, peripheral artery disease (PAD) occupies a high rank among age-related morbidities. A growing body of evidence suggests that PAD exacerbates cognitive decline in older adults, increasing the risk for the development of dementia (12–16, 18). In line with these findings, our cohort of patients with PAD showed decreased performance in neuropsychological tests, including short-term memory and sustained attention. Considering that all study participants had at least a high school degree, we speculate that these differences can be attributed to cognitive dysfunction associated with the PAD.

PAD is associated with the damage to vascular endothelium (49). Recent studies suggest that the PAD-associated damage is not limited to large vessels, but that it also extends to microvascular beds, including cerebral microcirculation. Given that the brain is very sensitive to reduced nutrient supply, maintaining the optimal microenvironment of metabolically active brain regions critically depends on NVC. Furthermore, it is now established that microvascular endothelial dysfunction is directly linked to the impairment of NVC responses (23). Here, we establish an association between impaired neurovascular function and diminished cognitive function in older adults with PAD. We demonstrate that NVC responses are significantly impaired in the PFC (including LDLPFC and RDLPFC) during a cognitive task in patients with PAD when compared with age- and sex-matched controls. These brain regions are implicated in higher cognitive functions, including attention, working memory, and inhibition of inappropriate responses (26). Clinical and experimental evidence supports the concept that impaired NVC responses (50–52) may be causally linked to age-related cognitive decline (53, 54). First, clinical studies demonstrate that cognitive performance is strongly correlated with NVC responses (55, 56) and that improvement of NVC responses is associated with improved cognitive performance in older adults (55, 56). Furthermore, short-term disruption of hemodynamic NVC responses, even in healthy young individuals, is associated with deterioration of cognitive performance. For example, short-term sleep deprivation in healthy young adults is associated with reduced NVC responses measured in the cerebral cortex and impaired cognitive performance (57, 58). Second, preclinical studies demonstrate that pharmacological disruption of NVC responses impairs cognitive performance in healthy young mice, mimicking the aging phenotype (31, 59). Third, the rescue of NVC responses in aged mice with pharmacological treatments that confer antiaging endothelial effects improves cognitive function (53, 54). These findings suggest that NVC may be an attractive target for the development of pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive performance in older adults with vascular diseases, such as PAD.

There is ample evidence that pathological conditions that promote endothelial dysfunction [e.g., hypertension (60), diabetes mellitus (61–63), obesity (64–66)] in the peripheral circulation also impair NVC responses. Our studies provide additional support to the concept that PAD is associated with generalized microvascular endothelial dysfunction, which in turn is associated with neurovascular impairment. However, microvascular endothelial dysfunction is not only a direct consequence of atherosclerotic disease. Studies using ex vivo approaches demonstrate that circulating factors present in the sera of patients with PAD elicit proinflammatory and prooxidative phenotypic changes in endothelial cells (67–69). Thus, it is likely that the same factors that promote atherogenesis in the large arteries also lead to the development of generalized endothelial dysfunction and thereby impair NVC responses. The same mechanisms are also likely to be responsible for the association between PAD and coronary endothelial dysfunction (70). The circulating factors that promote generalized endothelial dysfunction in patients with PAD may include factors related to the known dietary and lifestyle risk factors of PAD [e.g., cigarette smoke constituents (71), dyslipidemia, inflammatory cytokines, and other mediators]. Importantly, studies in the field of geroscience have identified interventions that can reverse endothelial dysfunction, rescue NVC responses, and thereby improve cognitive function (53, 72), including mitochondrial antioxidants (54), polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP)-1 inhibitors (73), dietary polyphenols (74), and modified dietary eating patterns (75). Although many of these experimental treatments have been tested in clinical studies (76, 77), future studies are warranted to test the efficacy of such interventions in older adults with PAD.

Furthermore, we found that peripheral microvascular endothelial function was significantly impaired in participants with PAD when compared to healthy controls. Although microvascular endothelial impairment is not a direct consequence of atherosclerotic disease, they often accompany each other (49), and recent studies indicate that peripheral microvascular endothelial dysfunction may increase the incidence of dysregulated perfusion to limbs (78).

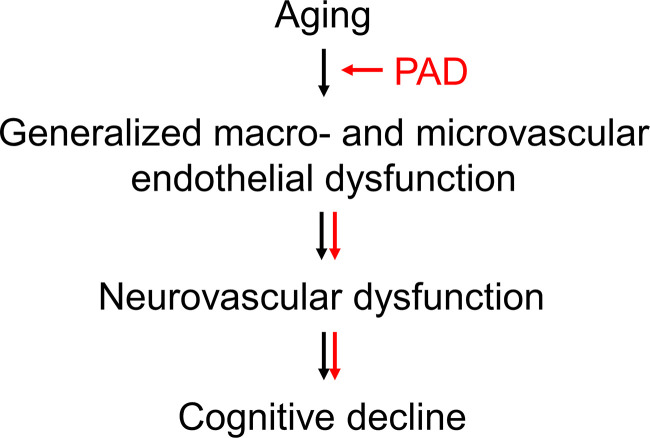

Although not significant, most likely due to a small sample size, we observed a medium-to-strong association between cognitive load, NVC responses, and peripheral microvascular endothelial function both in participants with PAD and in control participants. We also observed a significant and strong association between NVC responses evoked by cognitive stimulation and peripheral microvascular endothelial function in participants with PAD. Therefore, our findings provide initial evidence to support the theory that systemic endothelial dysfunction may extend from periphery to cerebral circulation to affect NVC responses and, possibly, to promote cognitive deficits in older adults with PAD (Fig. 5) (12, 15, 16, 79, 80). Our findings emphasize a need for further clinical studies to investigate the role of microvascular endothelial function in NVC responses and cognitive performance in aging and age-related diseases.

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanism by which PAD exacerbates the cognitive decline in aging. Based on our data, PAD exacerbates macro- and microvascular endothelial dysfunction in aging, which then extends to cerebral circulation, negatively impacting neurovascular coupling and promoting the cognitive decline in aging.

Conclusions

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to report the impairment of NVC responses in older adults with PAD. Our results suggest that PAD-related cognitive decrement may be mechanistically linked, at least in part, to generalized microvascular endothelial dysfunction and subsequent impairment of NVC responses. The clinical significance is that since endothelial dysfunction can be targeted pharmacologically, future studies are warranted to evaluate whether treatments, which improve NVC responses, can prevent or delay the onset of vascular cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults with PAD.

Limitations of the Study

The major limitation of our study is the small sample size, particularly with the NVC measurements. As with many clinical studies, there may have been a self-selection bias regarding study participation. Furthermore, the results of this study are only generalizable to patients with PAD with claudication. Although none of our study participants have been diagnosed with psychiatric or neurological disease, our study is limited because the familial medical history of psychiatric or neurologic has not been collected, nor it has been indicated in the electronic medical records. Furthermore, our study is limited because we were not equipped to evaluate carotid artery stenosis, which could be one of the contributing factors leading to the reduced cerebral circulation, nor this information was reflected in the electronic medical records. Finally, due to a small sample size, our study does not allow to control for smoking, comorbidities, and medications. However, recent evidence suggests that chronic smoking does not affect microvascular reactivity when measured in calves with fNIRS approach (81), and our participants abstained from smoking for at least 24 h before the assessments.

There are limitations associated with the design of the study and cross-sectional data analyses. Significant group differences and associations found in the variables do not provide evidence of causality. Although the association analysis demonstrates a positive correlation between key parameters measured, follow-up studies with larger sample sizes and longitudinal designs are needed to confirm these associations and potential changes over time. Although our study aimed to investigate hemodynamic changes in the brain during cognitive stimulation, the fNIRS methodology used in our study allows assessment of NVC responses limited to the cerebral cortex. Other methodologies such as transcranial Doppler flowmetry or functional MRI (fMRI) may provide additional insights into PAD-related hemodynamic changes in other deeper brain regions. Dynamic retinal vessel analysis may also provide additional insights into hemodynamic changes due to its ability to directly visualize NVC responses in retinal vasculature (26, 40, 51, 82).

GRANTS

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grants 941290, 966924, and 834339; National Institute on Aging Grants RF1AG072295, R01AG055395, R01AG068295, K01AG073614, and K01AG073613; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01NS100782; National Cancer Institute Grant R01CA255840; Oklahoma Shared Clinical and Translational Resources Grant U54GM104938 with an Institutional Development Award from National Institute of General Medical Sciences; the Presbyterian Health Foundation; the Reynolds Foundation; NIA-supported Geroscience Training Program in Oklahoma Grant T32AG052363; Oklahoma Nathan Shock Center Grant P30AG050911; and Cellular and Molecular GeroScience CoBRE Grant P20GM125528. Project no. TKP2021-NKTA-47 has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-NKTA funding scheme.

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, the Presbyterian Health Foundation, or the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary.

DISCLOSURES

A. Yabluchanskiy and Z. Ungvari serve as consulting editors for and A. Csiszar is an Editorial Board member of the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.D.O., P.M., T.C., A.L., F.S.-P., T.W.D., S.T., and A.Y. conceived and designed research; C.D.O., P.M., T.C., A.L., and A.Y. performed experiments; C.D.O., P.M., T.C., A.L., S.T., and A.Y. analyzed data; C.D.O., P.M., T.C., A.L., F.S.-P., T.W.D., S.T., A.W.G., P.S.M., S.R.W., J.M.K., A.N.-T, P.B., P.S., A.C., Z.U., and A.Y. interpreted results of experiments; C.D.O., P.M., T.C., A.L., and A.Y. prepared figures; C.D.O., P.M., T.C., A.L., S.T., and A.Y. drafted manuscript; C.D.O., F.S.-P., T.W.D., S.T., A.W.G., P.S.M., S.R.W., J.M.K., A.N.-T., P.B., P.S., A.C., Z.U., and A.Y. edited and revised manuscript; C.D.O., P.M.,T.C., A.L., F.S.-P., T.W.D., S.T., A.W.G., S.R.W., J.M.K., P.B., P.S., Z.U., and A.Y. approved final version of manuscript.

APPENDIX

Figures A1 and A2 demonstrate NVC responses measured during cognitive 1-back and 2-back stimulations.

Figure A1.

NVC responses measured during cognitive 1-back stimulation (vs. 0-back). Significant increase in oxyhemoglobin (HbO)/NVC responses was observed—shown as t-contrast map—in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of the control group, whereas participants with PAD showed significantly reduced distribution of HbO/NVC responses in the prefrontal cortex including the left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortices. We also observed a significant increase in reduced hemoglobin (HbR) in the prefrontal cortex including right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of participating patients with PAD. Significant changes correspond to q < 0.05 (false discovery rate-corrected), n = 5 per group. NVC, neurovascular coupling; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Figure A2.

NVC responses measured during cognitive 2-back stimulation (vs. 0-back). Significant increase in oxyhemoglobin (HbO)/NVC responses was observed—shown as t-contrast map—in the prefrontal cortex including the left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortices in the control group, whereas participants with PAD showed significantly reduced distribution of HbO/NVC responses in the prefrontal cortex including the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. We also observed a significant increase in reduced hemoglobin (HbR) in the prefrontal cortex of participants with PAD. Significant changes correspond to q < 0.05 (false discovery rate-corrected), n = 5 per group. NVC, neurovascular coupling; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Song P, Rudan D, Zhu Y, Fowkes FJI, Rahimi K, Fowkes FGR, Rudan I. Global, regional, and national prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: an updated systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health 7: e1020–e1030, 2019. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, Norman PE, Sampson UK, Williams LJ, Mensah GA, Criqui MH. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet 382: 1329–1340, 2013. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aday AW, Matsushita K. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease and polyvascular disease. Circ Res 128: 1818–1832, 2021. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch AT, Hartman L, Town RJ, Virnig BA. National health care costs of peripheral arterial disease in the Medicare population. Vasc Med 13: 209–215, 2008. doi: 10.1177/1358863X08089277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regensteiner JG, Hiatt WR, Coll JR, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, McDermott MM, Hirsch AT. The impact of peripheral arterial disease on health-related quality of life in the Peripheral Arterial Disease Awareness, Risk, and Treatment: New Resources for Survival (PARTNERS) program. Vasc Med 13: 15–24, 2008. doi: 10.1177/1358863X07084911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, Feigelson HS, Klauber MR, McCann TJ, Browner D. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med 326: 381–386, 1992. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202063260605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golomb BA, Dang TT, Criqui MH. Peripheral arterial disease: morbidity and mortality implications. Circulation 114: 688–699, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDermott MM, Liu K, Ferrucci L, Tian L, Guralnik JM, Liao Y, Criqui MH. Decline in functional performance predicts later increased mobility loss and mortality in peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 962–970, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDermott MM, Liu K, Greenland P, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, Chan C, Pearce WH, Schneider JR, Ferrucci L, Celic L, Taylor LM, Vonesh E, Martin GJ, Clark E. Functional decline in peripheral arterial disease: associations with the ankle brachial index and leg symptoms. JAMA 292: 453–461, 2004. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Green D, Greenland P, Tian L, Criqui MH, Lo C, Rifai N, Ridker PM, Zheng J, Pearce W. Functional decline in patients with and without peripheral arterial disease: predictive value of annual changes in levels of C-reactive protein and D-dimer. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 61: 374–379, 2006. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG; Group TIW. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg 45, Suppl S: S5– S67, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guerchet M, Aboyans V, Nubukpo P, Lacroix P, Clément JP, Preux PM. Ankle-brachial index as a marker of cognitive impairment and dementia in general population. A systematic review. Atherosclerosis 216: 251–257, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Casanegra AI, Silva-Palacios F, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A. Association between gait characteristics and endothelial oxidative stress and inflammation in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Age 38: 64, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s11357-016-9925-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breteler MM, Claus JJ, Grobbee DE, Hofman A. Cardiovascular disease and distribution of cognitive function in elderly people: the Rotterdam Study. BMJ 308: 1604–1608, 1994. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6944.1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espeland MA, Newman AB, Sink K, Gill TM, King AC, Miller ME, Guralnik J, Katula J, Church T, Manini T, Reid KF, McDermott MM; Group LS. Associations between ankle-brachial index and cognitive function: results from the lifestyle interventions and independence for elders trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16: 682–689, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laukka EJ, Starr JM, Deary IJ. Lower ankle-brachial index is related to worse cognitive performance in old age. Neuropsychology 28: 281–289, 2014. doi: 10.1037/neu0000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldstein SR, Tankard CF, Maier KJ, Pelletier JR, Snow J, Gardner AW, Macko R, Katzel LI. Peripheral arterial disease and cognitive function. Psychosom Med 65: 757–763, 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000088581.09495.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner AW, Montgomery PS, Wang M, Shen B, Casanegra AI, Silva-Palacios F, Ungvari Z, Yabluchanskiy A, Csiszar A, Waldstein SR. Cognitive decrement in older adults with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Geroscience 43: 2455–2465, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00437-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofman A, Ott A, Breteler MM, Bots ML, Slooter AJ, van Harskamp F, van Duijn CN, Van Broeckhoven C, Grobbee DE. Atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein E, and prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in the Rotterdam Study. Lancet 349: 151–154, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman AB, Fitzpatrick AL, Lopez O, Jackson S, Lyketsos C, Jagust W, Ives D, Dekosky ST, Kuller LH. Dementia and Alzheimer's disease incidence in relationship to cardiovascular disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 1101–1107, 2005. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tasci I, Safer U, Naharci MI, Gezer M, Demir O, Bozoglu E, Doruk H. Undetected peripheral arterial disease among older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 33: 5–11, 2018. doi: 10.1177/1533317517724000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corriveau RA, Bosetti F, Emr M, Gladman JT, Koenig JI, Moy CS, Pahigiannis K, Waddy SP, Koroshetz W. The science of vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID): a framework for advancing research priorities in the cerebrovascular biology of cognitive decline. Cell Mol Neurobiol 36: 281–288, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0334-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarantini S, Tran CHT, Gordon GR, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A. Impaired neurovascular coupling in aging and Alzheimer's disease: contribution of astrocyte dysfunction and endothelial impairment to cognitive decline. Exp Gerontol 94: 52–58, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toth P, Tarantini S, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Functional vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: Mechanisms and consequences of cerebral autoregulatory dysfunction, endothelial impairment, and neurovascular uncoupling in aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 312: H1–H20, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00581.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Csipo T, Lipecz A, Fulop GA, Hand RA, Ngo BTN, Dzialendzik M, Tarantini S, Balasubramanian P, Kiss T, Yabluchanska V, Silva-Palacios F, Courtney DL, Dasari TW, Sorond F, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Yabluchanskiy A. Age-related decline in peripheral vascular health predicts cognitive impairment. Geroscience 41: 125–136, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00063-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Csipo T, Mukli P, Lipecz A, Tarantini S, Bahadli D, Abdulhussein O, Owens C, Kiss T, Balasubramanian P, Nyúl-Tóth Á, Hand RA, Yabluchanska V, Sorond FA, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Yabluchanskiy A. Assessment of age-related decline of neurovascular coupling responses by functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) in humans. Geroscience 41: 495–509, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00122-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper LL, Mitchell GF. Aortic stiffness, cerebrovascular dysfunction, and memory. Pulse 4: 69–77, 2016. doi: 10.1159/000448176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim DH, Grodstein F, Newman AB, Chaves PH, Odden MC, Klein R, Sarnak MJ, Lipsitz LA. Microvascular and macrovascular abnormalities and cognitive and physical function in older adults: cardiovascular health study. J Am Geriatr Soc 63: 1886–1893, 2015. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girouard H, Iadecola C. Neurovascular coupling in the normal brain and in hypertension, stroke, and Alzheimer disease. J Appl Physiol 100: 328–335, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00966.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen BR, Kozberg MG, Bouchard MB, Shaik MA, Hillman EA. A critical role for the vascular endothelium in functional neurovascular coupling in the brain. J Am Heart Assoc 3: e000787, 2014. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarantini S, Hertelendy P, Tucsek Z, Valcarcel-Ares MN, Smith N, Menyhart A, Farkas E, Hodges EL, Towner R, Deak F, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Toth P. Pharmacologically-induced neurovascular uncoupling is associated with cognitive impairment in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35: 1871–1881, 2015. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarantini S, Nyúl-Tóth A, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Mukli P, Balasubramanian P, Ungvari A, Toth P, Benyo Z, Sonntag WE, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A. Endothelial deficiency of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) impairs neurovascular coupling responses in mice, mimicking aspects of the brain aging phenotype. Geroscience 43: 2387–2394, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00405-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toth P, Tarantini S, Ashpole NM, Tucsek Z, Milne GL, Valcarcel-Ares NM, Menyhart A, Farkas E, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. IGF-1 deficiency impairs neurovascular coupling in mice: implications for cerebromicrovascular aging. Aging Cell 14: 1034–1044, 2015. doi: 10.1111/acel.12372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang C, Kwak L, Ballew SH, Jaar BG, Deal JA, Folsom AR, Heiss G, Sharrett AR, Selvin E, Sabanayagam C, Coresh J, Matsushita K. Retinal microvascular findings and risk of incident peripheral artery disease: an analysis from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Atherosclerosis 294: 62–71, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wintergerst MWM, Falahat P, Holz FG, Schaefer C, Schahab N, Finger R. Retinal vasculature assessed by OCTA in peripheral arterial disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 61: 3203, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardner AW, Parker DE, Webb N, Montgomery PS, Scott KJ, Blevins SM. Calf muscle hemoglobin oxygen saturation characteristics and exercise performance in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 48: 644–649, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Blevins SM, Nael R, Afaq A. Sex differences in calf muscle hemoglobin oxygen saturation in patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Surg 50: 77–82, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.12.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Khurana A, Ritti-Dias RM, Blevins SM. Calf muscle hemoglobin oxygen saturation in patients with peripheral artery disease who have different types of exertional leg pain. J Vasc Surg 55: 1654–1661, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu WC, Mohler E 3rd, Ratcliffe SJ, Wehrli FW, Detre JA, Floyd TF. Skeletal muscle microvascular flow in progressive peripheral artery disease: assessment with continuous arterial spin-labeling perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 2372–2377, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Csipo T, Lipecz A, Mukli P, Bahadli D, Abdulhussein O, Owens CD, Tarantini S, Hand RA, Yabluchanska V, Kellawan JM, Sorond F, James JA, Csiszar A, Ungvari ZI, Yabluchanskiy A. Increased cognitive workload evokes greater neurovascular coupling responses in healthy young adults. PLoS One 16: e0250043, 2021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santosa H, Zhai X, Fishburn F, Huppert T. The NIRS Brain AnalyzIR Toolbox. Algorithms 11: 73, 2018. doi: 10.3390/a11050073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacques SL. Optical properties of biological tissues: a review. Phys Med Biol 58: R37–61, 2013. [Erratum in Phys Med Biol 58:5007–5008, 2013]. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/58/11/R37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haatveit BC, Sundet K, Hugdahl K, Ueland T, Melle I, Andreassen OA. The validity of d prime as a working memory index: results from the “Bergen n-back task". J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 32: 871–880, 2010. doi: 10.1080/13803391003596421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panerai RB, Moody M, Eames PJ, Potter JF. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation during brain activation paradigms. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1202– H1208, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00115.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dresler T, Obersteiner A, Schecklmann M, Vogel AC, Ehlis AC, Richter MM, Plichta MM, Reiss K, Pekrun R, Fallgatter AJ. Arithmetic tasks in different formats and their influence on behavior and brain oxygenation as assessed with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS): a study involving primary and secondary school children. J Neural Transm 116: 1689–1700, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Jamovi Project. jamovi. (Version 1.6) [Computer Software], 2021. https://www.jamovi.org.

- 47.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing (Version 4.0), 2020. [2020 Aug 24].https://cran.r-project.org [Google Scholar]

- 48.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2020 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 141: e139–e596, 2020. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Igari K, Kudo T, Toyofuku T, Inoue Y. Endothelial dysfunction of patients with peripheral arterial disease measured by peripheral arterial tonometry. Int J Vasc Med 2016: 3805380–3805380, 2016. doi: 10.1155/2016/3805380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Csiszar A, Yabluchanskiy A, Ungvari A, Ungvari Z, Tarantini S. Overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria improves neurovascular coupling responses in aged mice. Geroscience 41: 609–617, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00111-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lipecz A, Csipo T, Tarantini S, Hand RA, Ngo BN, Conley S, Nemeth G, Tsorbatzoglou A, Courtney DL, Yabluchanska V, Csiszar A, Ungvari ZI, Yabluchanskiy A. Age-related impairment of neurovascular coupling responses: a dynamic vessel analysis (DVA)-based approach to measure decreased flicker light stimulus-induced retinal arteriolar dilation in healthy older adults. Geroscience 41: 341–349, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yabluchanskiy A, Nyul-Toth A, Csiszar A, Gulej R, Saunders D, Towner R, Turner M, Zhao Y, Abdelkari D, Rypma B, Tarantini S. Age-related alterations in the cerebrovasculature affect neurovascular coupling and BOLD fMRI responses: Insights from animal models of aging. Psychophysiology 58: e13718, 2021. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tarantini S, Balasubramanian P, Delfavero J, Csipo T, Yabluchanskiy A, Kiss T, Nyul-Toth A, Mukli P, Toth P, Ahire C, Ungvari A, Benyo Z, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Treatment with the BCL-2/BCL-xL inhibitor senolytic drug ABT263/Navitoclax improves functional hyperemia in aged mice. Geroscience 43: 2427–2440, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00440-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tarantini S, Valcarcel-Ares NM, Yabluchanskiy A, Fulop GA, Hertelendy P, Gautam T, Farkas E, Perz A, Rabinovitch PS, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Treatment with the mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant peptide SS-31 rescues neurovascular coupling responses and cerebrovascular endothelial function and improves cognition in aged mice. Aging Cell 17: e12731, 2018. doi: 10.1111/acel.12731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sorond FA, Hurwitz S, Salat DH, Greve DN, Fisher ND. Neurovascular coupling, cerebral white matter integrity, and response to cocoa in older people. Neurology 81: 904–909, 2013. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a351aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sorond FA, Kiely DK, Galica A, Moscufo N, Serrador JM, Iloputaife I, Egorova S, Dell'Oglio E, Meier DS, Newton E, Milberg WP, Guttmann CR, Lipsitz LA. Neurovascular coupling is impaired in slow walkers: the MOBILIZE Boston Study. Ann Neurol 70: 213–220, 2011. doi: 10.1002/ana.22433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mukli P, Csipo T, Lipecz A, Stylianou O, Racz FS, Owens CD, Perry JW, Tarantini S, Sorond FA, Kellawan JM, Purebl G, Yang Y, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari ZI, Yabluchanskiy A. Sleep deprivation alters task-related changes in functional connectivity of the frontal cortex: a near-infrared spectroscopy study. Brain Behav 11: e02135, 2021. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Csipo T, Lipecz A, Owens C, Mukli P, Perry JW, Tarantini S, Balasubramanian P, Nyul-Toth A, Yabluchanska V, Sorond FA, Kellawan JM, Purebl G, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Yabluchanskiy A. Sleep deprivation impairs cognitive performance, alters task-associated cerebral blood flow and decreases cortical neurovascular coupling-related hemodynamic responses. Sci Rep 11: 20994, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-00188-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tarantini S, Yabluchanksiy A, Fulop GA, Hertelendy P, Valcarcel-Ares MN, Kiss T, Bagwell JM, O'Connor D, Farkas E, Sorond F, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Pharmacologically induced impairment of neurovascular coupling responses alters gait coordination in mice. Geroscience 39: 601–614, 2017. [Erratum in Geroscience 40: 219, 2018]. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-0003-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kazama K, Anrather J, Zhou P, Girouard H, Frys K, Milner TA, Iadecola C. Angiotensin II impairs neurovascular coupling in neocortex through NADPH oxidase-derived radicals. Circ Res 95: 1019–1026, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148637.85595.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duarte JV, Pereira JM, Quendera B, Raimundo M, Moreno C, Gomes L, Carrilho F, Castelo-Branco M. Early disrupted neurovascular coupling and changed event level hemodynamic response function in type 2 diabetes: an fMRI study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35: 1671–1680, 2015. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2015.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lasta M, Pemp B, Schmidl D, Boltz A, Kaya S, Palkovits S, Werkmeister R, Howorka K, Popa-Cherecheanu A, Garhöfer G, Schmetterer L. Neurovascular dysfunction precedes neural dysfunction in the retina of patients with type 1 diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 842–847, 2013. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mogi M, Horiuchi M. Neurovascular coupling in cognitive impairment associated with diabetes mellitus. Circ J 75: 1042–1048, 2011. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balasubramanian P, Kiss T, Tarantini S, Nyul-Toth A, Ahire C, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Lipecz A, Tabak A, Institoris A, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Obesity-induced cognitive impairment in older adults: a microvascular perspective. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 320: H740–H761, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00736.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li W, Prakash R, Chawla D, Du W, Didion SP, Filosa JA, Zhang Q, Brann DW, Lima VV, Tostes RC, Ergul A. Early effects of high-fat diet on neurovascular function and focal ischemic brain injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 304: R1001–1008, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00523.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tucsek Z, Toth P, Tarantini S, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Warrington JP, Giles CB, Wren JD, Koller A, Ballabh P, Sonntag WE, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A. Aging exacerbates obesity-induced cerebromicrovascular rarefaction, neurovascular uncoupling, and cognitive decline in mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 69: 1339–1352, 2014. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mangiafico RA, Sarnataro F, Mangiafico M, Fiore CE. Impaired cognitive performance in asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease: relation to C-reactive protein and D-dimer levels. Age Ageing 35: 60–65, 2006. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Sosnowska D, Casanegra AI, Esponda OL, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Sonntag WE. Impaired vascular endothelial growth factor A and inflammation in patients with peripheral artery disease. Angiology 65: 683–690, 2014. doi: 10.1177/0003319713501376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Sosnowska D, Casanegra AI, Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Sonntag WE. Greater endothelial apoptosis and oxidative stress in patients with peripheral artery disease. Int J Vasc Med 2014: 160534, 2014. doi: 10.1155/2014/160534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar A, Bano S, Bhurgri U, Kumar J, Ali A, Dembra S, Kumar L, Shahid S, Khalid D, Rizwan A. Peripheral artery disease as a predictor of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing coronary angiography. Cureus 13: e15094, 2021. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abdelghany TM, Ismail RS, Mansoor FA, Zweier JR, Lowe F, Zweier JL. Cigarette smoke constituents cause endothelial nitric oxide synthase dysfunction and uncoupling due to depletion of tetrahydrobiopterin with degradation of GTP cyclohydrolase. Nitric Oxide 76: 113–121, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kiss T, Nyul-Toth A, Balasubramanian P, Tarantini S, Ahire C, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Farkas E, Wren JD, Garman L, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) supplementation promotes neurovascular rejuvenation in aged mice: transcriptional footprint of SIRT1 activation, mitochondrial protection, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic effects. Geroscience 42: 527–546, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00165-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tarantini S, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Fulop G, Kiss T, Balasubramanian P, DelFavero J, Ahire C, Ungvari A, Nyul-Toth A, Farkas E, Benyo Z, Toth A, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Treatment with the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor PJ-34 improves cerebromicrovascular endothelial function, neurovascular coupling responses and cognitive performance in aged mice, supporting the NAD+ depletion hypothesis of neurovascular aging. Geroscience 41: 533–542, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Toth P, Tarantini S, Tucsek Z, Ashpole NM, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Ballabh P, Koller A, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Resveratrol treatment rescues neurovascular coupling in aged mice: role of improved cerebromicrovascular endothelial function and downregulation of NADPH oxidase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H299–H308, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00744.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Balasubramanian P, DelFavero J, Ungvari A, Papp M, Tarantini A, Price N, de Cabo R, Tarantini S. Time-restricted feeding (TRF) for prevention of age-related vascular cognitive impairment and dementia. Ageing Res Rev 64: 101189, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wightman EL, Reay JL, Haskell CF, Williamson G, Dew TP, Kennedy DO. Effects of resveratrol alone or in combination with piperine on cerebral blood flow parameters and cognitive performance in human subjects: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over investigation. Br J Nutr 112: 203–213, 2014. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514000737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Witte AV, Kerti L, Margulies DS, Floel A. Effects of resveratrol on memory performance, hippocampal functional connectivity, and glucose metabolism in healthy older adults. J Neurosci 34: 7862–7870, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0385-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beckman JA, Duncan MS, Damrauer SM, Wells QS, Barnett JV, Wasserman DH, Bedimo RJ, Butt AA, Marconi VC, Sico JJ, Tindle HA, Bonaca MP, Aday AW, Freiberg MS. Microvascular disease, peripheral artery disease, and amputation. Circulation 140: 449–458, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fujiwara Y, Chaves PH, Takahashi R, Amano H, Yoshida H, Kumagai S, Fujita K, Wang DG, Shinkai S. Arterial pulse wave velocity as a marker of poor cognitive function in an elderly community-dwelling population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60: 607–612, 2005. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haratz S, Weinstein G, Molshazki N, Beeri MS, Ravona-Springer R, Marzeliak O, Goldbourt U, Tanne D. Impaired cerebral hemodynamics and cognitive performance in patients with atherothrombotic disease. JAD 46: 137–144, 2015. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zamparini G, Butin G, Fischer MO, Gérard JL, Hanouz JL, Fellahi JL. Noninvasive assessment of peripheral microcirculation by near-infrared spectroscopy: a comparative study in healthy smoking and nonsmoking volunteers. J Clin Monit Comput 29: 555–559, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s10877-014-9631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.István L, Czakó C, Élő Á, Mihály Z, Sótonyi P, Varga A, Ungvári Z, Csiszár A, Yabluchanskiy A, Conley S, Csipő T, Lipecz Á, Kovács I, Nagy ZZ. Imaging retinal microvascular manifestations of carotid artery disease in older adults: from diagnosis of ocular complications to understanding microvascular contributions to cognitive impairment. Geroscience 43: 1703–1723, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00392-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]