Abstract

Electrolyte-gated transistors (EGTs), capable of transducing biological and biochemical inputs into amplified electronic signals and stably operating in aqueous environments, have emerged as fundamental building blocks in bioelectronics. In this Primer, the different EGT architectures are described with the fundamental mechanisms underpinning their functional operation, providing insight into key experiments including necessary data analysis and validation. Several organic and inorganic materials used in the EGT structures and the different fabrication approaches for an optimal experimental design are presented and compared. The functional bio-layers and/or biosystems integrated into or interfaced to EGTs, including self-organization and self-assembly strategies, are reviewed. Relevant and promising applications are discussed, including two-dimensional and three-dimensional cell monitoring, ultra-sensitive biosensors, electrophysiology, synaptic and neuromorphic bio-interfaces, prosthetics and robotics. Advantages, limitations and possible optimizations are also surveyed. Finally, current issues and future directions for further developments and applications are discussed.

Bioelectronics enables the study of the aqueous media that host soft tissues and interfaces for their proper function, as well as of the connections between various cells and/or organs, which communicate by exchanging specific ions and biomolecules1. The fundamental properties of the biological systems set the requirements of the electronics counterpart. Electrolyte-gated transistors (EGTs) have emerged as important building blocks for enhanced bioelectronics because they are stable in an aqueous environment, operate at low voltages and can transduce and amplify biological signals into electronic signals2–5.

EGTs are three-terminal devices where the conductivity of a semiconducting material connected to two electrodes, classified as the source and the drain, is modulated by a third electrode known as the gate. In a basic EGT, the gate electrode and the semiconducting channel are in direct contact with the electrolyte. A voltage VG and VD is applied at the gate and drain electrode, respectively (FIG. 1a). VG and VD are referenced to the source voltage, which is typically set to ground, VS = 0 V. The polarity and magnitude of the voltage applied to the gate electrode result in a drift of cations or anions from the electrolyte to the semiconducting channel. The ionic charges can enhance or deplete the electronic charges residing in the semiconductor channel. This ionic–electronic modulation gives rise to a large variation of the channel conductivity that, in turn, manifests in a large modulation of the electronic source to drain current flowing through the transistor channel. Upon application of the gate, source and drain voltages, ions drift into the electrolyte and accumulate at the gate and semiconductor. The sign of the gate voltage controls the charge type of these ions (cations or anions), whereas its magnitude controls their density. For example, when a positive gate voltage is applied, the anion concentration increases at the gate and the cation concentration increases at the semiconducting channel. The sub-nanometre scale dimension of the ions interacting with the gate and channel materials results in a large electrostatic interaction at the gate/electrolyte and electrolyte/channel interfaces, which yields the low-voltage operation of EGTs that can range from a few volts to even less than 1 V, depending on the specific materials used. The low-voltage operation is critically important for electrophysiology and in the case of a large variety of biosensors. In addition, in contrast to the conventional thin-film field-effect transistors, in EGTs the gate is not required to be positioned in front of the channel as the charge modulation is due to the accumulation or depletion of ions transported within the electrolyte. Therefore, in EGTs the gate can also be positioned laterally, coplanar to the source and drain electrodes, which greatly simplifies the technological fabrication process4,6,7.

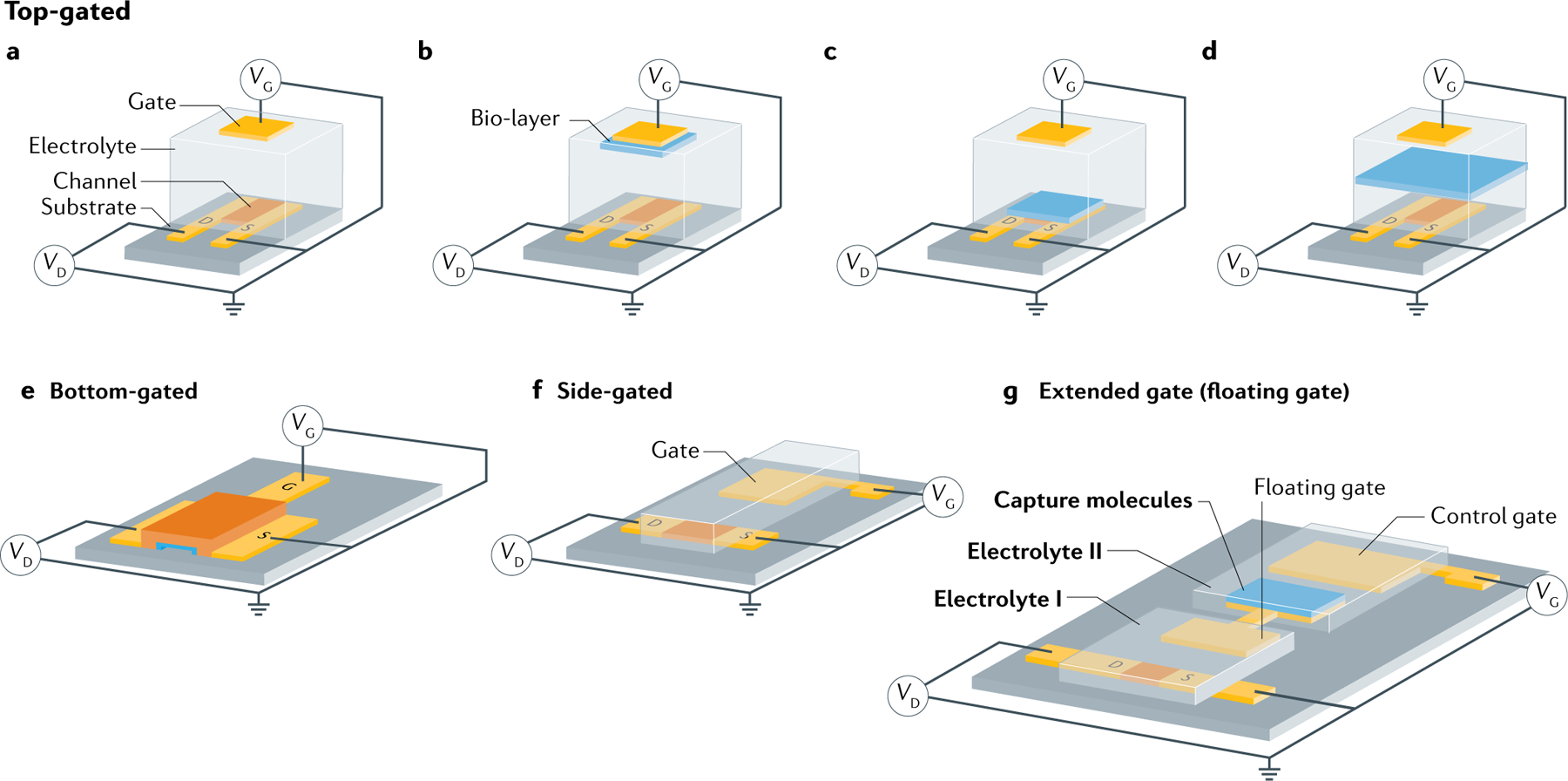

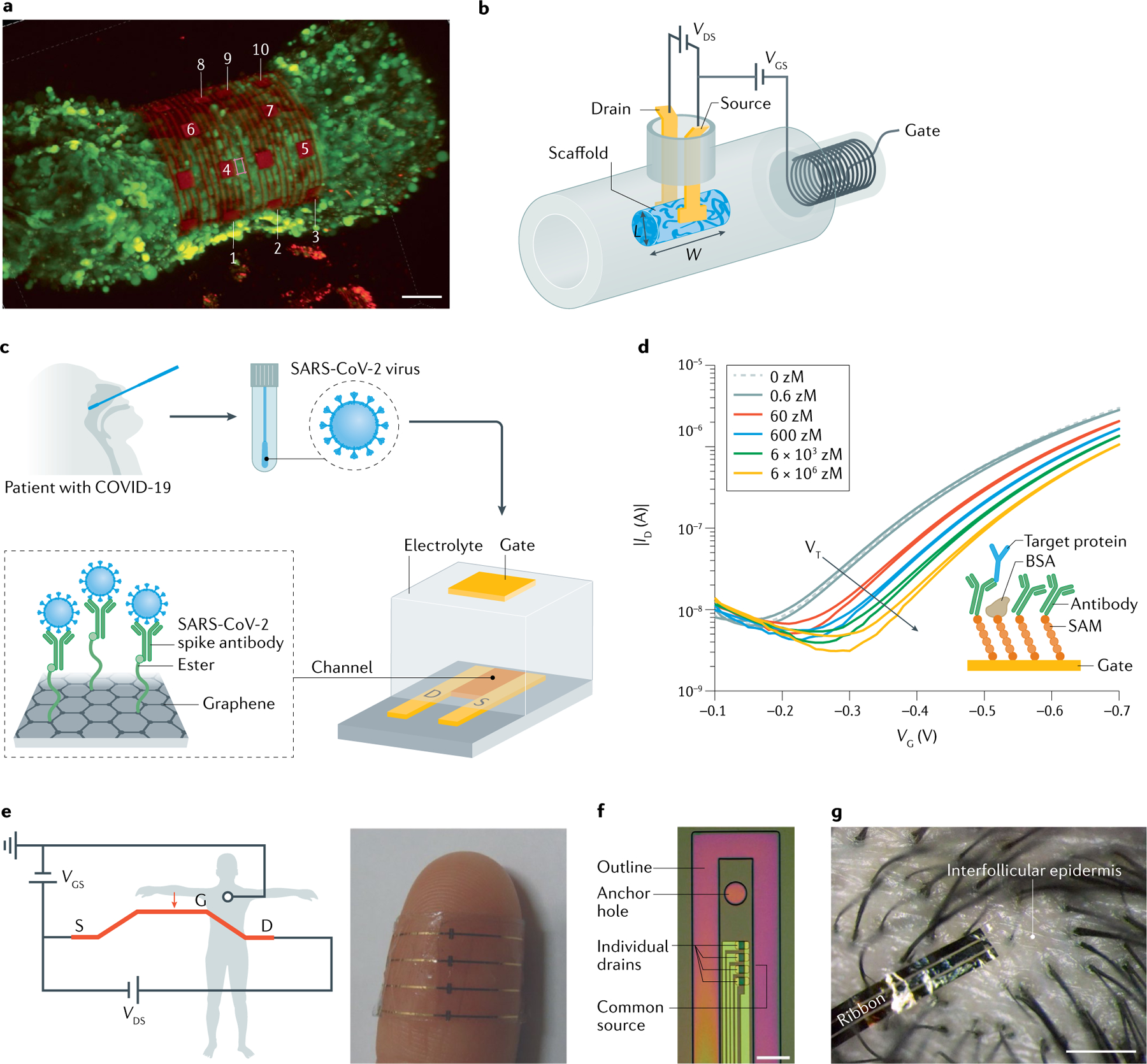

Fig. 1 |. EGTs for enhanced bioelectronics.

Basic architectures of an electrolyte-gated transistor (EGT). Various components, such as the gate, electrolyte, source, semiconducting channel and drain, are highlighted. VG, VD and VS are the gate, drain and source voltage, respectively. a | Top-gated architecture. b | Top-gated EGT with a bio-layer on the gate electrode. The gate is a polarizable electrode. c | Top-gated EGT with a bio-layer on the transistor channel. The gate can be a polarizable or non-polarizable (for example, reference) electrode. d | Top-gated EGT with a bio-layer included in the electrolyte. The bio-layer separates the electrolyte in two compartments. The gate can be a polarizable or non-polarizable electrode. e | Bottom-gated EGT architecture. f | Side-gated EGT architecture. g | Extended gate (or floating gate) EGT architecture.

EGTs are divided into two main classes depending on the ionic permeability of the channel material, which is a property related to both the electrolyte and the semiconductor. For ion-impermeable semiconductors, the ionic–electronic interaction takes place at the only electrolyte–semiconductor interface, and this mode of operation identifies electrolyte gate field-effect transistors. The ionic–electronic layer accumulated at the interface is named the electric double layer (EDL). Electrolyte gate field-effect transistors can operate with both inorganic and organic materials, including for example amorphous oxides8–10, transition metal dichalcogenides11,12, graphene13,14, nanotubes15–17, organic small molecules and polymers18–20. By contrast, the ionic–electronic interaction includes the whole three-dimensional volume of the material channel for ion-permeable semiconductors. This operational mode identifies devices addressed as electrochemical transistors21–24. At the state of the art, ion-permeable channels are based on organic mixed ionic–electronic conductors that are often polymers, which readily solvate and transport ionic species25–27. Organic mixed ionic–electronic conductor-based EGTs give rise to the class of organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs). Internal ion-gated transistors are a class of OECTs specifically designed for bioelectronic applications based on the concept of volumetric response, where the electrolyte is embedded into an ion-conducting membrane separating the gate and the channel. Relevant state-of-art polymers used for OECTs and ion-gated transistors include poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS), poly[3-(5-carboxypentyl)thiophene-2,5-diyl] (P3CPT), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy) ethoxy)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene) (p(g2T-TT)), poly[2,6-(4,4-bis-potassium butanylsulfonate-4H-cyclopenta-[2,1-b;3,4-b′]-dithiophene)-alt-4,7-(2,1,3-benzothiadiazole)] (PCPDTBT-SO3K; also known as CPE-K), poly(benzimidazobenzophenanthroline) (BBL) and poly[[1,2,3, 6,7,8-hexahydro-1,3,6,8-tetraoxo-2,7-bis(7-oxo-3,6,9,12,15-pentaoxahexadec-1-yl)benzo[lmn][3,8] phenanthroline-4,9-diyl][2,2′-bithiophene]-5,5′-diyl] (p(gNDI-T2))28–32.

The concept of EGTs was developed by Wrighton and colleagues in 1984 using polypyrrole33, an organic ion-permeable semiconductor. Compared with ion-sensitive field-effect transistors34–36 where an insulating layer separates the semiconductor and the electrolyte, the direct contact between the electrolyte and the semiconductor in EGTs enables a direct interaction between ions and electronic charges in the material channel. The class of ion-sensitive field-effect transistors34,36 are not discussed in great detail in this Primer, but are highlighted elsewhere37,38. Current efforts in EGTs leverage on the emerging materials, architectures, fabrication and integration approaches, opening possibilities for enhanced bioelectronics. Indeed, when EGTs serve in bioelectronics, the biological signals can be probed by directly embedding the medium of study within the EGT structure, such as blood, saliva, tears or lymph as the physiological liquid or cells and skin or leaf as the biological specimen.

EGT architectures.

EGTs can be constructed with different device architectures, which depend on the position of the gate electrode relative to the semiconductor channel. In the top-gated geometry (FIG. 1), the gate is positioned directly over the channel. The electrolyte can be a biological fluid and its chemical, biological or ionic properties can be directly probed with the EGT. This architecture is used in electrophysiology39–41, ion detection42–44 and neuromorphic applications45–49. A top-gated EGT with a bio-layer embedded on the gate electrode (FIG. 1b) is commonly used for the development of high-sensitivity label-free biosensors where protein probes such as antibodies, peptides and enzymes50–56, or genomic probes made up of DNA and RNA molecules57–59, are linked to the gate and selectively bind and detect the target biomarker. A top-gated EGT with a bio-layer placed on the top of the channel (FIG. 1c) is a typical design used for cell monitoring60,61 and in biosensors where the bio-functionalization of the semiconducting channel is deemed more convenient62–66. More insights into the self-organization and self-assembled materials used in EGTs biosensors are given in BOX 1. There is also a design where the bio-layer lacks contact with either the gate or the semiconductor surface but lies in the electrolyte (FIG. 1d), which is applicable for monitoring the integrity of cell membrane tight junctions67–69 as well as for selective ion detection and monitoring70–73.

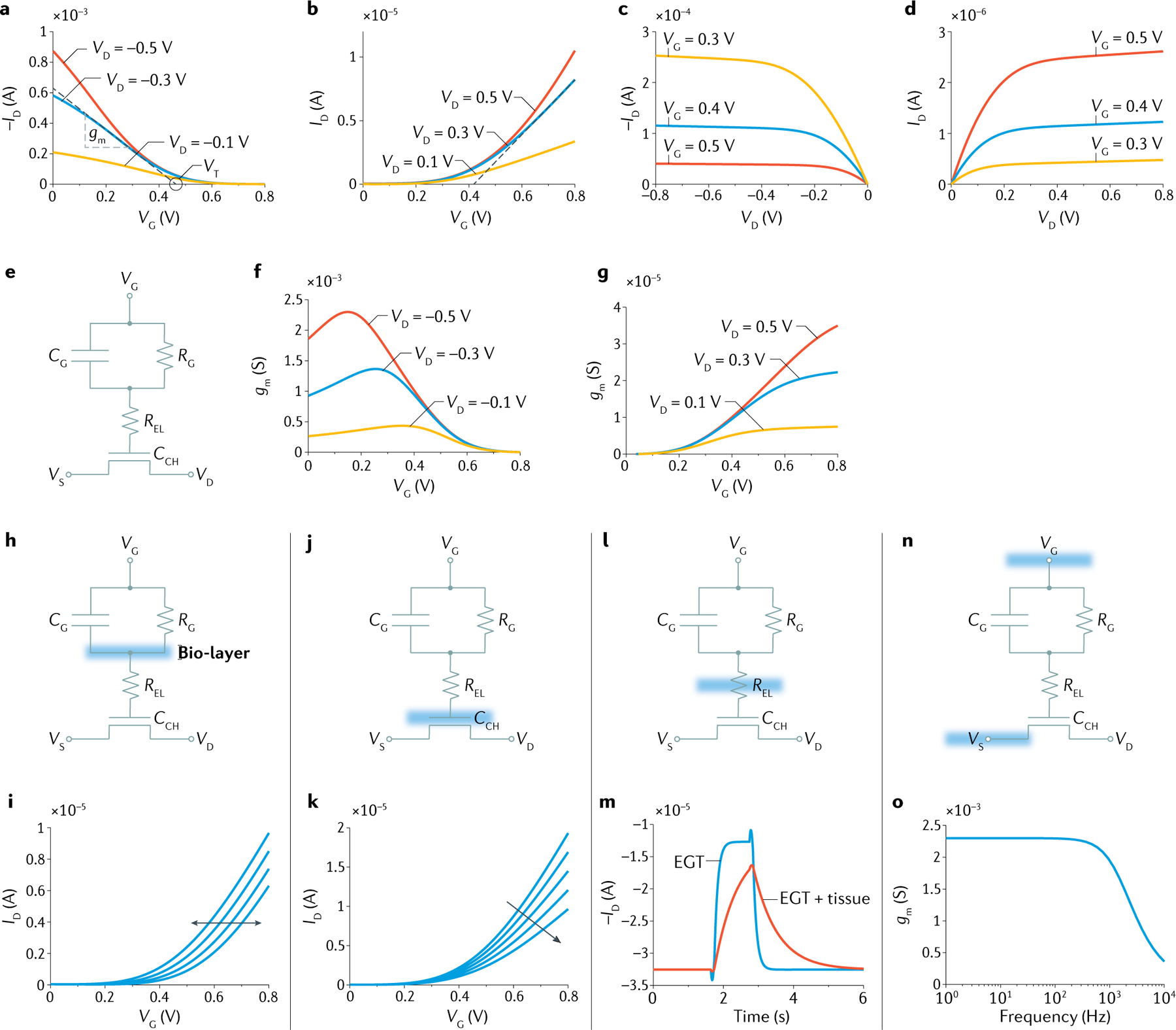

Box 1 |. Self-organization and self-assembly in EGTs for bioelectronics.

The most adopted electrolyte-gated transistor (EGT) biosensor architecture envisions a large-area gate electrode functionalized with a recognition moiety317. The strategies adopted are summarized here, with special attention to those based on self-organization and self-assembly on noble metals. Gate functionalization relies on three steps: grafting a linker to the gate electrode; building a primer layer on top for anchoring the bio-recognition group; and passivating the exposed gate surface with an (antifouling) material that minimizes non-specific adsorption.

Step 1: the linker

Metal electrodes are functionalized by covalent or strong non-covalent bonds with linker-bearing molecules. The reported types of linkers and anchoring strategies are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. These approaches are simple, versatile and easy to implement, as they exploit either naturally occurring chemical functions or groups that are easy to introduce by molecular engineering.

Step 2: the primer

Three main approaches were adopted in EGTs.

Streptavidin or neutravidin binds biotinylated linkers on self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on one side, and biotinylated peptides and nucleotides as bio-recognition moieties on the other side. This is a highly specific strong interaction318.

A monolayer of protein A/G engineered with linkers for direct immobilization, else grafted to a SAM by formation of amide bonds. Protein G suitably orients antibodies with their antigen binding sites offered to the medium319,320.

Constructive assembly of bio-recognition molecules on SAM-forming linkers by either click chemistry or physical interactions. This approach is detailed in Supplementary Table 3.

Step 3: passivation

This is necessary to avoid uncontrolled adsorption and minimize in-parallel capacitances that may lead to signal artefacts. To fill the bare metal surface left exposed after steps 1 and 2, hydrophobic/hydrophilic SAMs82,321 or antifouling SAMs such as oligo-ethylene glycol-terminated ones81,322 are used. Alternatively, it is possible to saturate the vacancies with bovine serum albumin (BSA)50,164.

Bio-layer.

A biological layer made with biological entities such as, for example, antibodies, peptides, DNA, RNA, enzymes, cells, tissues or organs.

The less common bottom gate geometry includes an ion-conducting membrane (a solid electrolyte; shown in blue in FIG. 1e) that separates the metallic gate from the semiconductor channel74. This configuration can be used in physiological recording where a biocompatible semiconductor channel (PEDOT:PSS) is placed in direct contact with human tissue, for example, to record neural signals75. The gate lies in the same plane as the semiconductor channel in the side-gated geometry76–78 (FIG. 1f), which is typically used in neuromorphic applications45,79. In this case, the side gate can function as a global gate, simultaneously biasing several nearby semiconductor channels. A fourth EGT architecture is the extended gate (or floating gate) design (FIG. 1g), in which there are two separate electrolyte compartments (I and II) connected by a gold electrode with two pads, called the floating gate. The floating gate is capacitively coupled through the electrolytes to both the semiconductor channel and the control gate80. The floating gate geometry is commonly used for biological or chemical sensing81–84, but has also been utilized for other sensing applications, such as the transduction of cell electroactivity85. In biological sensing, capture molecules are immobilized on the arm of the floating gate in electrolyte compartment II. Target molecules introduced into compartment II bind to the functionalized pad and produce an EGT signal. The two compartments avoid direct contact of the target molecules with the semiconductor channel in compartment I, preventing possible non-specific adsorption to the semiconductor.

This Primer provides an overview of the relevant materials, technologies and experimental methods for the development of enhanced performance bioelectronics based on EGTs (Experimentation). The electrical characteristics and the meaningful device parameters of the EGTs used in bioelectronics are highlighted and examined (Results). In the Applications section, an overview of key bioelectronic applications engaging EGTs is summarized. The factors affecting the device performance and reproducibility are discussed (Reproducibility and data deposition), along with the current limitations and approaches to improve EGT performance (Limitations and optimizations). Finally, the challenges, potential new routes and future application paths are outlined (Outlook). With respect to previous reviews on EGTs covering a specific class of materials4,6,86–89 and highlighting application-specific device implementation49,90–96, here we provide a broad perspective of EGTs for enhanced performance bioelectronics covering various aspects: from the underlying principles to best practices for experimental design, data analysis and promoting reproducibility.

Experimentation

An overview of the typical active materials used for EGTs is provided in this section, with some focus on organic semiconductors (OSCs) comprising both ion-impermeable and ion-permeable small molecules and polymers. A comprehensive overview of the organic materials used is provided in Supplementary Table 1 and the operation modes of the various classes of EGTs are given in BOX 2. Following this, inorganic semiconductors made of amorphous metal oxides (AMOs) and two-dimensional materials are described and a comprehensive overview of the inorganic materials is provided in Supplementary Table 2. Finally, EGT fabrication methods based on both conventional photolithography and additive manufacturing are presented and discussed.

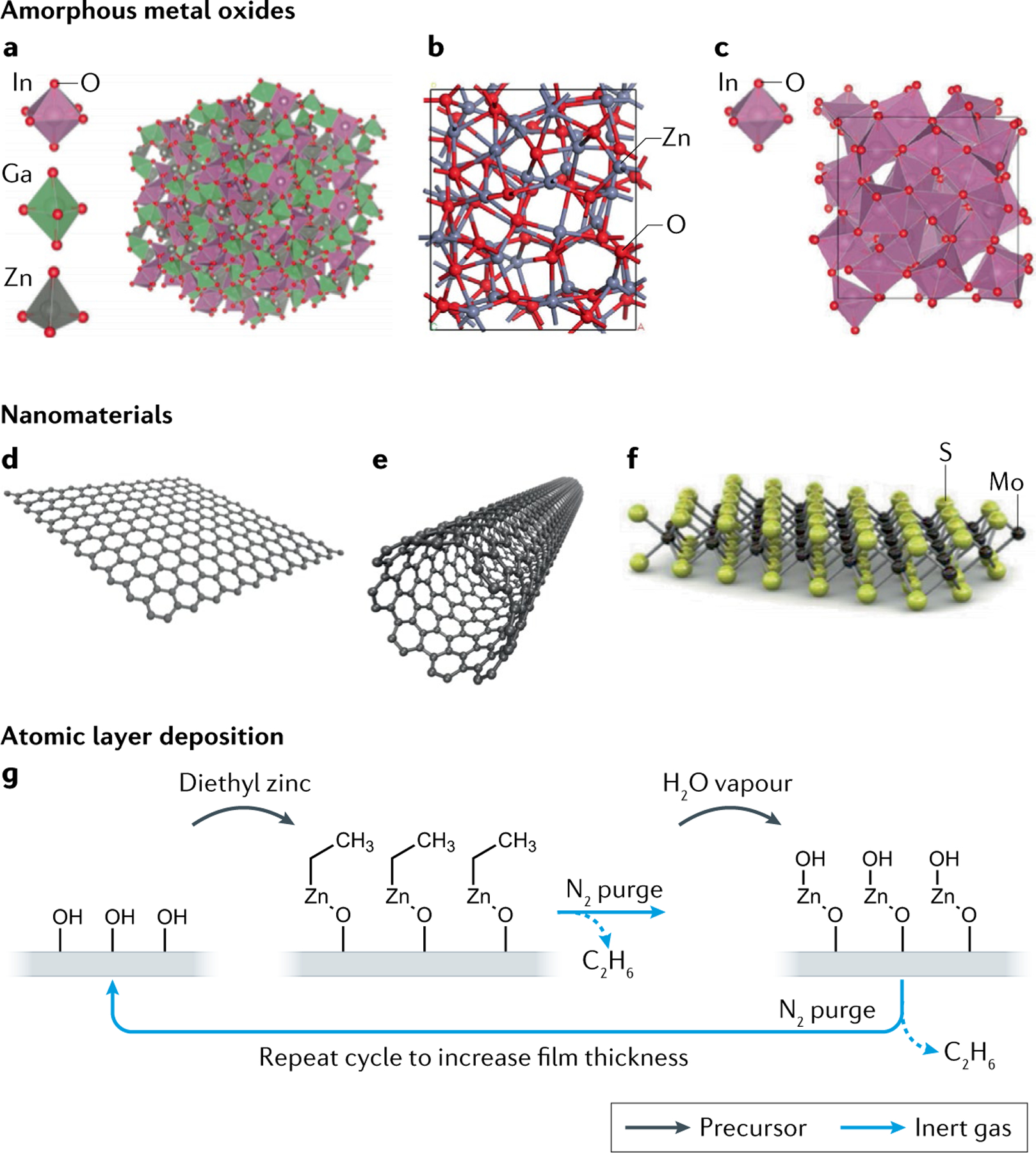

Box 2 |. Insight into EGT operation.

Upon application of a potential difference, charge polarization can be formed along semiconductor–electrolyte interfaces. Such polarization includes an elevated concentration of ions in the electrolyte and the accumulation of electronic charges within the semiconductor phase (see the figure). The former is governed by the static and dynamic fundamentals of the interfacial electric double layer (EDL), which involves an inner hydration sheet, the outer Helmholtz plane323 and a diffusive layer324. The latter process includes the transfer of charges from a source electrode into the semiconductor, charge transport, trap-filling and a corresponding alteration of the energetics325. Efforts have been devoted to further understand the nature and details of such charge polarization, as it is crucial for the operation of electrodes and devices.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, cyclic/hydrodynamic voltammetry, chrono-potentiometry/amperometry and atomic force microscopy, and transistor parameterization have been used to probe the properties of this electrolyte–semiconductor interface for organic, carbon, oxide and inorganic semiconductors when interfaced with ionic liquids, aqueous or non-aqueous electrolytes326–331. In addition, modelling327 has been employed to merge the theories of electrochemistry, charge transport and solid-state (device) physics in order to describe the capacitor residing across the interface. For instance, by coupling the chemical potential of the electronic charges in the semiconductor to the EDL, the key electrical characteristics of electrolyte-gated transistors (EGTs) can be reproduced23. Better descriptions of the device parameters have been achieved for graphene-based EGTs332 and for poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS)-based capacitors by incorporating quantum capacitance into the model333. Further, the capacitor, with its included polarized charges, is defined as coplanar sheets extending only over a few nanometres in the perpendicular direction (see the figure, left) and reaches typically from a few to tens of farads per square centimetre. For mixed ion-electron and nanoporous semiconductors, the ions can penetrate the channel bulk, which causes these sheets to turn into bi-continuous networks, residing along interfaces up to hundreds of square metres per gram (see the figure, right). This creation of networks generates volumetric capacitances that can reach beyond 100 F g−1 and corresponding bulk transistor channels. For proper transistor modulation, the capacitance at the gate is equally important and the design of gate electrodes operating as polarizable or non-polarizable (faradaic) electrodes is a crucial design criterion for EGTs. To a great extent, the nature of the gate-electrolyte334 and the electrolyte-channel capacitances dictates the accumulation/depletion of charges in the channel, which defines the operational characteristics of the resulting EGT and EGT-based bioelectronics.

Organic semiconductors.

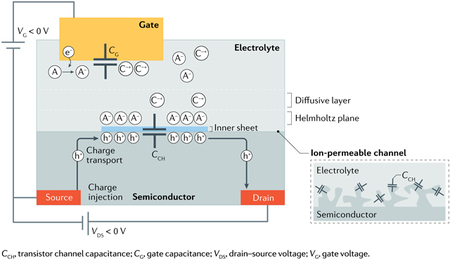

OSCs used for EGTs can be clustered in two main classes: ion-impermeable OSCs that produce an EDL at the electrolyte–semiconductor interface upon application of a gate bias; and ion-permeable OSCs that generate an EDL distributed in the whole volume of the OSC4,6. The most common organic conducting material used in OECTs is PEDOT:PSS28,97–101. Originally developed as an organic conductor and used in the inter-layer of photovoltaics and diodes, PEDOT:PSS has recently been used in OECTs for bioelectronics. Materials typically used for organic-based EGTs are small molecules, such as the prototypical pentacene102–104, and polymers, such as the widely used poly(3-hexylthiophene-2,5-diyl) (P3HT), poly[2,5-bis(3-tetradecylthiophen-2-yl) thieno[3,2-b]thiophene] (pBTTT-C14), poly[2,5-(2-octyldodecyl)-3,6-diketopyrrolopyrrole-alt-5,5-(2,5-di(thien-2-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene)] (DPP-DTT) and 5,5′-bis-(7-dodecyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)-2,2′-bithiophene (DDFTTF)105–109. These OSCs were originally developed for organic field-effect transistors and then tuned by optimizing the processing conditions for EGT bioelectronics. The molecular structure of the conjugated polymers and OSCs typically used for EGTs is shown in FIG. 2.

Fig. 2 |. Typical organic materials used for EGTs.

Various classes of organic semiconductors (OSCs) developed for organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) (conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs), conjugated polymer composites and conjugated polymers) and OSCs used for electrolyte-gated transistors (EGTs). α6T, α-sexithiophene; BBL, poly(benzimidazobenzophenanthroline); DDFTTF, 5,5′-bis-(7-dodecyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)-2,2′-bithiophene; DPP-DTT, poly[2,5-(2-octyldodecyl)-3,6-diketopyrrolopyrrole-alt-5,5-(2,5-di(thien-2-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene)]; gBDT-g2T, poly(2-(3,3′-bis(triethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)-(4,8-bis(triethylene glycol monomethyl ether)benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b’]dithiophene-2,6-diyl)); P3CPT, poly(3-carboxypentylthiophene); P3HT, poly(3-hexylthiophene); P3MEEMT, poly(3-{[diethylene glycol monomethyl ether]methyl}thiophene); p(gNDI-gT2), poly{[N,N′-naphthalene-1,4,5,8-bis(dicarboximide)-2,6-diyl]-alt-5,5′-(3,3′-bis(methoxy)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)}; pBTTT-C14, poly[2,5-bis(3-tetradecylthiophen-2-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene]; PCPDTBT-SO3K, poly[2,6-(4,4-bis-potassium butanylsulfonate-4H-cyclopenta-[2,1-b;3,4-b’]-dithiophene)-alt-4,7-(2,1,3-benzothiadiazole)]; PEDOT:PSS, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate; PEDOT:PSTFSILi, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) potassium poly[4-styrenesulfonyl(trifluoromethyl sulfonyl) imide]; PEDOT-S, sodium poly(4-(2,3-dihydrothieno[3,4-b][1,4]dioxin-2-yl-methoxy)-1-butylsulfonate); PEDOT:TOS, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) tosylate; p(g3T2), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(triethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)); p(g0T2-g6T2), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(methoxy)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl))-(2-(3,3′-bis(hexaethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)); p(g1T2-g5T2), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(monoethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl))-(2-(3,3′-bis(pentaethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)); p(g2T2-g4T2), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(diethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl))-(2-(3,3′-bis(tetraethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)); p(g2T2-T), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(diethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)thiophene); p(g3T2-T), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(triethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)thiophene); p(g4T2-T), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(tetraethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)thiophene); p(g6T2-T), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(hexaethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)thiophene); p(g2T-TT), poly(2-(3,3′-bis(triethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-[2,2′-bithiophen]-5-yl)thieno[3,2-b]thiophene); p(gDPP-T2), poly((3,6-bis(5-thien-2-yl)-2,5-di(triethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-2,5-dihydropyrrolo[3,4-c] pyrrole-1,4-dione)2,2′-bithiophene); PgNaN, poly([3,8-di-(heptaethylene glycol monomethyl ether)-3,8-dihydroindolo[7, 6-g]indole-2,7-dione]-[3,8-didodecyl-1,3,6,8-tetrahydroindolo[7, 6-g]indole-2,7-dione]); PTEBS, sodium poly[2-(3-thienyl)-ethoxy-4-butylsulfonate]; PTHS, tetrabutylammonium poly(6-(thiophene-3-yl)hexane-1-sulfonate).

Ion-impermeable OSCs interact with the electrolyte at a single interface, resulting in a limited impact of ions on the bulk molecular structure. By contrast, in ion-permeable OSCs the hydrated ions enter inside the OSC microstructure and this additional mass can often disrupt the pristine organization of the semiconductor. This volumetric mixed ionic–electronic conduction is currently calling for new materials for the active layer in OECTs20,25,110. Several ion-permeable and ion-impermeable semiconductors are listed in Supplementary Table 1. In both OSC types, the charge carriers are required to propagate along conjugated chains with a series of intermolecular hopping events. However, OECT semiconducting materials face other constraints imposed by aqueous and ionic ingress within the microstructure111–113. Charge injection into an OECT semiconductor, for example, can only occur when competing oxidation and reduction reactions of the aqueous media are not thermodynamically favourable. Consequently, hole injection is limited to relatively electron-rich semiconducting polymers, such as polythiophenes, and some diketopyrrolopyrrole variants, but excludes deeper HOMO (highest occupied molecular orbital) polymers. In the presence of an aqueous electrolyte, the semiconductor microstructure has to accommodate the diffusion of hydrated ions, which compensates the propagating polarons within the bulk of the semiconductor film112. Hydrated ions can disrupt the pristine organization of the semiconductor as well as introduce charge traps and coulombic pinning of the free electronic carriers. To date, semiconductors that can tolerate this physical swelling process with minimal impact on local organization seem to exhibit better performances. For example, polythiophenes with shorter glycolated side chain lengths typically outperform those with longer chain lengths, because the long chains exhibit more swelling by accommodating a larger fraction of water and ions. However, some degree of polar side chain incorporation into the polymer design is required to facilitate the hydrated ion influx. The relevant metrics for OECT electrical performance incorporate not only a carrier mobility term but also volumetric capacitance, which scales with the ionic mass density28. Long, inert, hydrocarbon chains — introduced originally in semiconducting polymers for solubility and aggregation purposes — are detrimental to capacitance. For example, in the exemplary electron-transporting polymer BBL114, large volumetric capacitances can be achieved because the polymer does not have these alkyl side chains, whereas the polystyrene sulfonate scaffold in PEDOT:PSS contributes to a much lower capacitance than analogous polythiophenes.

Intermolecular hopping events.

Charge transport mechanisms taking place between various parts of molecules and polymers.

Hole injection.

The transfer of holes from an electrode to a semiconductor.

HOMO.

(Highest occupied molecular orbital). A type of molecular orbital.

Polarons.

Fermionic quasiparticles due to the strong interaction between electrons and atoms in a solid material. When electrons move in a dielectric crystal, the atoms displace from their equilibrium positions to screen the electronic charges.

Conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs), characterized by their conjugated carbon backbone and pendant ionic side chains, are emerging as mixed ionic–electronic transport materials used in EGTs31,97,112,115–121. Focusing on CPEs, CPE-K is a self-doped polymer containing cyclopentadithiophene (CPDT) and benzothiadiazole (BT) alternating donor–acceptor units. The sulfonate side chains stabilize polarons on the conjugate backbone and the water-soluble side chains are critical for bulk doping of the film and volumetric operation. OECTs fabricated with CPE-K show accumulation-mode operation, allowing low power operation when the transistor is in its OFF state, rapid switching times and good stability over the range of temperatures relevant for biological applications31. A large maximum transconductance in a relatively small device area was obtained using interdigitated contacts that enable large channel width, making CPE-K OECTs ideal candidates for neural interfacing. These results highlight the potential of CPEs in OECTs and suggest new optimized designs, as for example by adapting the high-mobility donor–acceptor conjugated backbones discovered by the organic field-effect transistor community to OECTs.

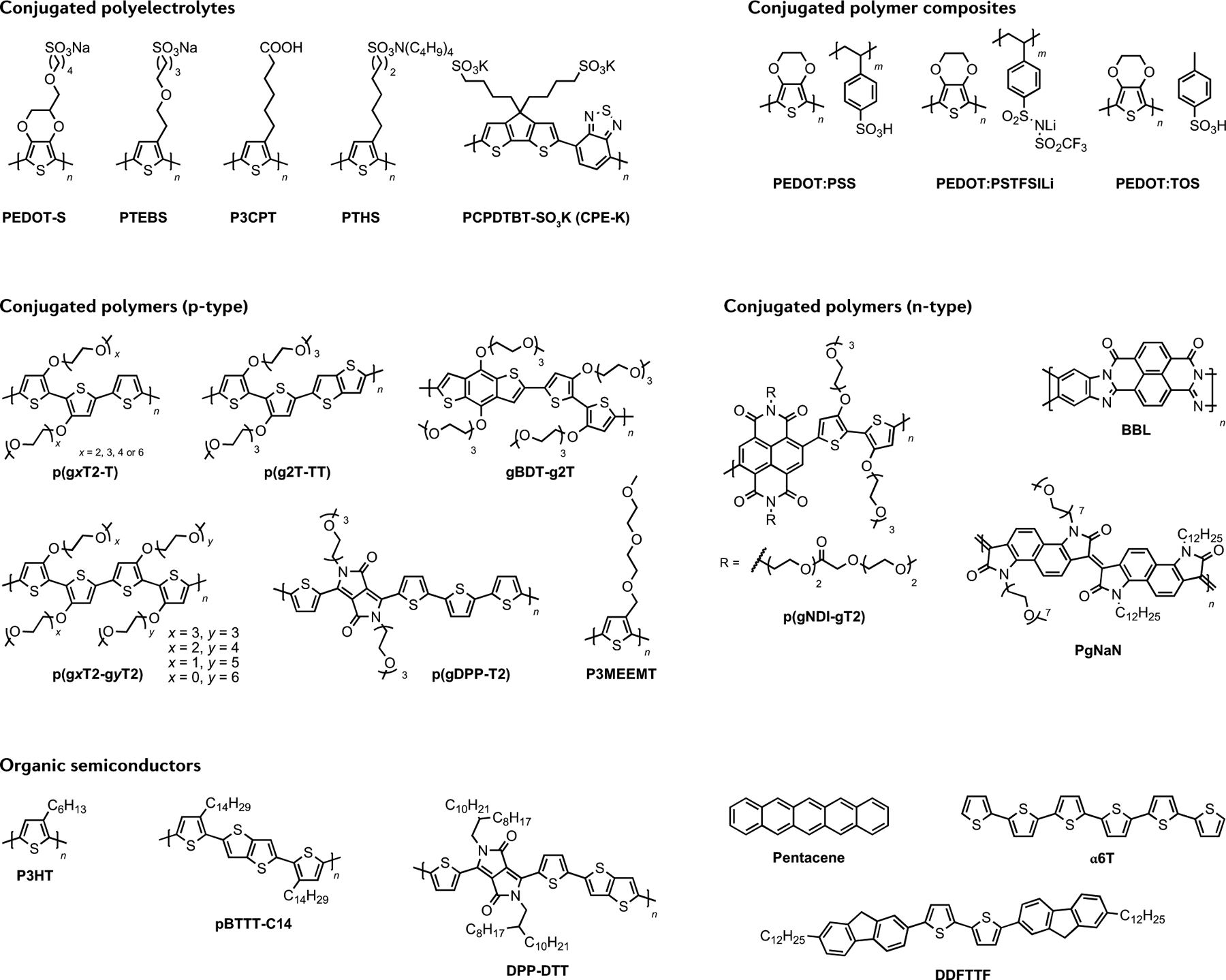

Inorganic semiconductors.

In addition to the OSCs, various inorganic semiconductors are employed as channel materials in EGTs. Many researchers have investigated the use of amorphous oxide semiconductors (AMOs), and in some cases crystalline metal oxides, such as InGaZnO9,122–124, ZnO125–128 or In2O3 (REFS129–134), as semiconductors in EGTs (FIG. 3a–c). These materials are generally n-channel materials (electron conductors) and can be deposited as thin films by various methods, including vapour-phase approaches such as atomic layer deposition or sputtering, as shown in FIG. 3g. n-Channel AMOs can also be solution-processed using printing methods, such as inkjet or aerosol printing, or spin-coating of inks containing molecular precursors126,129,130,132; subsequent annealing of the dried deposits at temperatures of several hundred degrees Celsius in air produces oxide films. Advantages of AMOs include their high electron mobility, which can be well over 10 cm2 V−1 s−1, leading in principle to high gain in EGT sensing applications9,123,124. Moreover, AMOs can be patterned using traditional photolithographic approaches (indium–gallium–zinc oxide (IGZO) transistors are already used in industry)130, or with additive manufacturing strategies. An ongoing challenge with solution-processed AMOs is lowering the annealing temperatures to 200 °C or less, which facilitates fabrication on plastic substrates126,129. The option to use plastic substrates, which is certainly possible for organic EGTs, could be important for high-throughput manufacturing of low-cost EGT biosensors.

Fig. 3 |. Typical inorganic semiconductors used for EGTs.

a | Amorphous structure of indium–gallium–zinc oxide (IGZO). b | Structure of amorphous zinc oxide (ZnO). c | Structure of amorphous indium oxide (InO3). d | Two-dimensional layer of the semimetal graphene. e | Single-walled carbon nanotubes. f | Two-dimensional molybdenum disulfide (MoS2). g | Atomic layer deposition is one method to deposit thin films of inorganic semiconductors on a substrate. Precursors injected into the chamber react with the surface of the substrate, building the film up layer by layer. Purge steps in between with inert gas remove by-products and undesired precursor from the chamber. Atomic layer deposition ultimately enables control over film thickness and uniformity. EGT, electrolyte-gated transistor. Part a adapted with permission from REF.312, ACS. Part b adapted from REF.313, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Part c adapted with permission from REF.314, Wiley. Parts d and e adapted from REF.315, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Part f adapted with permission from REF.316, Elsevier.

Atomic layer deposition.

A vacuum deposition method based on sequential use of one or more volatile compounds that react and/or decompose on the substrate surface, producing a deposit of a thin-film layer.

Sputtering.

A method used for the deposition of metals, insulators and semiconductors. in a vacuum chamber, a solid material (named target) is bombarded by energetic particles of a plasma or gas. The microscopic particles ejected from its surface deposit on a substrate.

The electrolyte gating of AMO EGTs is based on the EDL formation at the electrolyte–semiconductor interface (BOX 2). Upon application of a gate voltage, ions in the gating electrolyte generally cannot penetrate AMOs due to steric exclusion and they accumulate at the interface6. To counter the ionic charge, oppositely charged electrons (or holes) accumulate on the AMO side of the interface, turning ON the EGT. Despite the different channel modulation mechanism between AMOs and organics, the functional result is very similar, where current increases with increasing VG beyond a threshold gate voltage, VT.

Other alternative channel materials for EGTs include semimetals such as graphene58,135–138, two-dimensional semiconductors139–143 and carbon nanotubes17,144–147 (FIG. 3d–f). Supplementary Table 2 includes a list of the various inorganic and nanomaterial semiconductors employed in EGTs and the resulting key parameters. An advantage of two-dimensional materials or other nanomaterials is that they can be crystalline and, therefore, show large electronic mobilities ranging to as high as 50–1,000 cm2 V−1 s−1 in EGTs. Challenges compared with thin-film metal oxides include processing them by lithography or by printing, and several works are emerging on these topics17,141,143,148–151.

Fabrication approaches.

Two basic approaches to the fabrication of EGTs for bioelectronics are based on photolithography127 or additive manufacturing by printing80,152,153. EGT fabrication can be relatively simple because the gate electrode may be spatially separated from the source–drain channel. This feature eliminates a difficult gate metal alignment step that is usually required for fabricating thin-film transistors in other applications127. Furthermore, the EGT channel dimensions are in the range of 5–20 μm or even larger, which also relaxes the semiconductor patterning requirements.

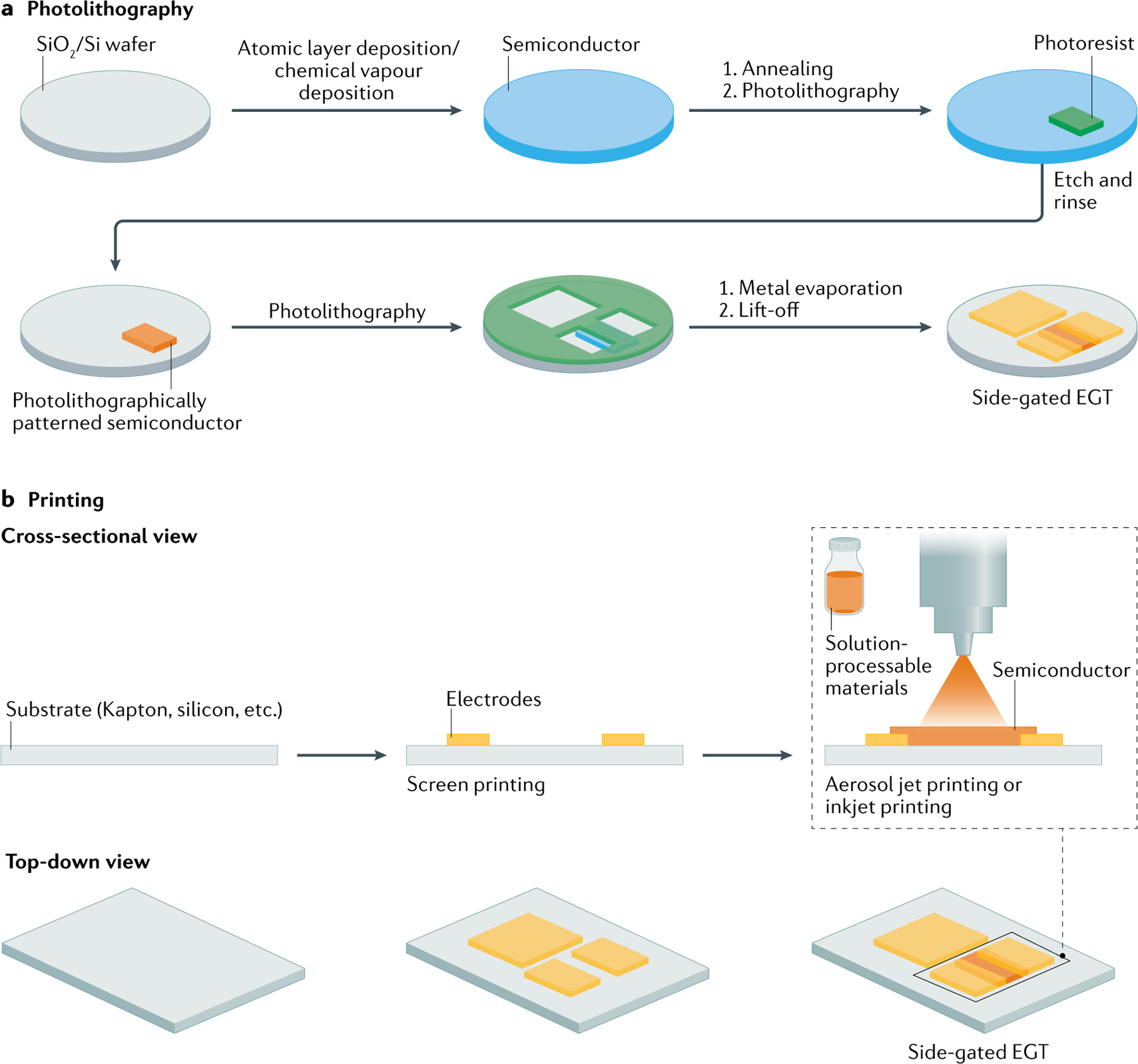

The fabrication approaches for building side-gated EGTs are illustrated in FIG. 4. In a typical fabrication approach (FIG. 4a), the semiconductor is first blanket deposited onto the substrate, which is followed by patterning the semiconductor into a rectangular patch using photolithography and etching. Next, a second photolithographic step includes spin-coating of photoresist, followed by light exposure through a photomask and subsequent photoresist development. In the case of the floating gate design, this second photolithographic step also produces the floating gate. Metal deposition (for example, electron beam-evaporated 50 nm gold, with a thin 5 nm titanium adhesion layer), followed by lift-off, produces the electrode pattern. These approaches can be extended also to the floating gate and charge-modulated field-effect transistor architecture (BOX 3).

Fig. 4 |. Fabrication of EGTs.

Fabrication of side-gated electrolyte-gated transistor (EGT). a | Conventional fabrication utilizing common deposition methods for semiconductor film growth and photolithography for selective patterning of the semiconductor and electrodes. Necessary equipment includes spin-coater, mask aligner, vacuum deposition chamber and vacuum evaporator chamber. Photolithography is typically performed on silicon, glass, ceramic and plastic substrates. Miniaturized devices with high-resolution features can be obtained. b | Unconventional fabrication utilizing additive processes including screen printing, aerosol jet printing and inkjet printing. Necessary equipment includes aerosol jet, inkjet, gravure and/or screen printer. Printing methods are suitable for glass, ceramic, plastic, textile and paper substrates. Fabricated devices can be flexible, wearable, on a large area and of low cost.

Box 3 |. Insight into the charge-modulated field-effect transistor architecture for bioelectronic applications.

The organic charge-modulated field-effect transistor is a bioelectronic field-effect transistor with two gates that cooperate to set the working point, which is the bias needed to form the channel and ensure the maximization of the device’s performance. The first, called the control gate, has the purpose to bias the transistor. The second, which is electrically floating, is the sensing part of the device. When one side of the extended gate (the sensing area) is functionalized and exposed to the detection environment, any charge variation within the Debye length is able to modulate the threshold voltage of the device and, therefore, the drain current. There are several strength points in this sensing strategy: the channel area is not exposed to the liquid measurement environment, preventing possible degradation of the semiconductor; the sensing surface can be specialized according to the species to detect; and the device does not need a biasing reference electrode in the solution owing to the presence of the control gate. On a planar substrate, it is possible to fabricate a large variety of materials and sensor arrays able to detect various quantities related to the same bioprocess (as depicted in the figure) including DNA–RNA detection335,336, cellular interfacing85,337, pH sensing338, temperature and pressure detection based on piezo/pyroelectric materials339,340.

This sensing strategy has the remarkable characteristic of being adaptable to any semiconductor or dielectric material. Moreover, the sensitivity of the device can be finely tuned by acting on geometric parameters, such as the ratio between the channel and the sensing area, or by adjusting the different capacitive contributions of the structure. All of these features make the organic charge-modulated field-effect transistor a versatile and ultra-sensitive tool for bioelectronic applications.

In the printing approach, metals and semiconductors are deposited from liquid inks. Common printing methods for sensor fabrication include screen printing76,154–156, inkjet printing153,157–159 and/or aerosol jet printing80–83,160,161. FIGURE 4b shows a representative process where first the metal source and drain electrodes are deposited on a substrate by screen printing. Typically, the metals need to be annealed to reach their maximum conductivity. Next, the semiconductor channel is printed ensuring alignment to the source and drain electrodes. In the case of the floating gate architecture, a third printing step is required to print a gel electrolyte over the channel and the floating gate80 (compartment I in FIG. 1g). A hybrid fabrication procedure in which conventional lithography steps are combined with printing steps can be also be adopted80–83,160,161. For example, conventional lithography can be used for the electrodes instead of screen printing in FIG. 4b, and printing can be used to complete the semiconductor channel and gel electrolyte. An inherent advantage of printing is the limited amount of materials needed, which can be desirable when using relatively expensive organic materials. On the other hand, lithography is extremely advanced and accessible for many laboratories. However, conventional photolithography is often incompatible with OSCs and requires either engineered resists or non-conventional processes162.

If the EGT is being applied for selective detection of biomolecules, it is necessary to chemically functionalize the gate or the floating gate with capture molecules. Insights into bio-functionalization methods are provided in BOX 1 and Supplementary Table 3. If a gate metal electrode is functionalized, adventitious adsorbates on the gate, from processing steps such as residual photoresist, should be removed with careful cleaning using oxygen plasma or ozone cleaning. The gate electrode can be fabricated without photoresist by printing or by shadow masking of vapour-deposited metal. Functionalization of the electrode can be done by immersing the electrode in the solution163,164 or by using a PDMS well or a microfluidic cell to deliver the solution over the electrode54,83,136,165,166.

Oxygen plasma.

A plasma for treatment of a surface that is an effective, economical, environmentally safe method for critical cleaning.

Ozone cleaning.

A cleaning process of surfaces based on photochemical reactions involving ultraviolet light, oxygen and the material on the surface of the substrate.

Shadow masking.

A technique using a metal, silicon or plastic sheet with suitably designed openings coupled to a substrate.

A material deposited over the mask can reach the substrate only in the opening regions, thus defining a pattern according to the design of the mask.

Experimental design and methods.

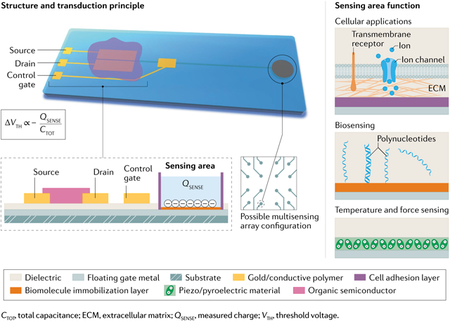

Bio-layer integration is imperative to enable EGTs with the ability to communicate with a surrounding biological environment. A layer of biological recognition elements, such as antibodies, nucleic acids, peptides, enzymes and so on, is required for biosensors to achieve selectivity via the stable binding of markers or analytes to the elicited recognition elements90,163,167. The bio-recognition layer is anchored to one of the transistor transducing interfaces168, usually the gate or the semiconductor surface. In general, the grafting on the gate surface is more reproducible and less impactful on the device’s electronic properties. For instance, functionalizing an OSC surface with anchoring chemical groups can result in lower mobilities169. FIGURE 5a–e displays various strategies adopted to attach capturing molecules to a gate surface.

Fig. 5 |. Integration of bio-layers in EGTs.

a–c | Immobilization of bio-recognition elements on a solid surface by means of physical adsorption (part a), self-assembled monolayer (SAM) (part b) and stepwise deposition of biological species with opposite charges (part c). d | Bio-affinity immobilization based on biotin-tagged bio-recognition elements and streptavidin immobilized on a solid surface. e | Bio-affinity immobilization used for the orientation of biomolecules on a solid surface. EGT, electrolyte-gated transistor.

The physical immobilization of biomolecules involves three main approaches. For the sake of simplicity, here we focus on protein immobilization but these same considerations hold for bio-layers made of DNA, RNA and peptides. Physical absorption is achieved by direct interaction of antibodies with the solid surface (FIG. 5a), such as the gate or the semiconductor in EGTs. To improve the density, a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) can be used. Covalent immobilization can be obtained via a reaction between carboxyl groups immobilized on the SAM with amino groups from residues of the biomolecules (FIG. 5b). In the case of biological species bearing opposite charges, layer-by-layer absorption enables a three-dimensional structure (FIG. 5c). Bio-affinity immobilization enables the orientation of antibodies on a surface and various approaches can be adopted, which include biotinylated biomolecules captured by a streptavidin layer deposited on the electrode (FIG. 5d) or direct binding between the Fc region of an antibody and protein A or protein G deposited on the surface (FIG. 5e).

Overall, these methods can be applied to anchor the bio-layer on both the gate electrode and the semiconducting channel. Typically, gold is used for the gate electrode because it is polarizable, and there are well-established chemical methods for the grafting of a bio-layer. In the case where the bio-layer is embedded on the channel, a wide range of semiconducting and conducting materials have been used, and the grafting method has to be properly optimized for the specific material adopted90,163. Fundamental insights into self-organization and self-assembly are given in BOX 1 and Supplementary Table 3.

Results

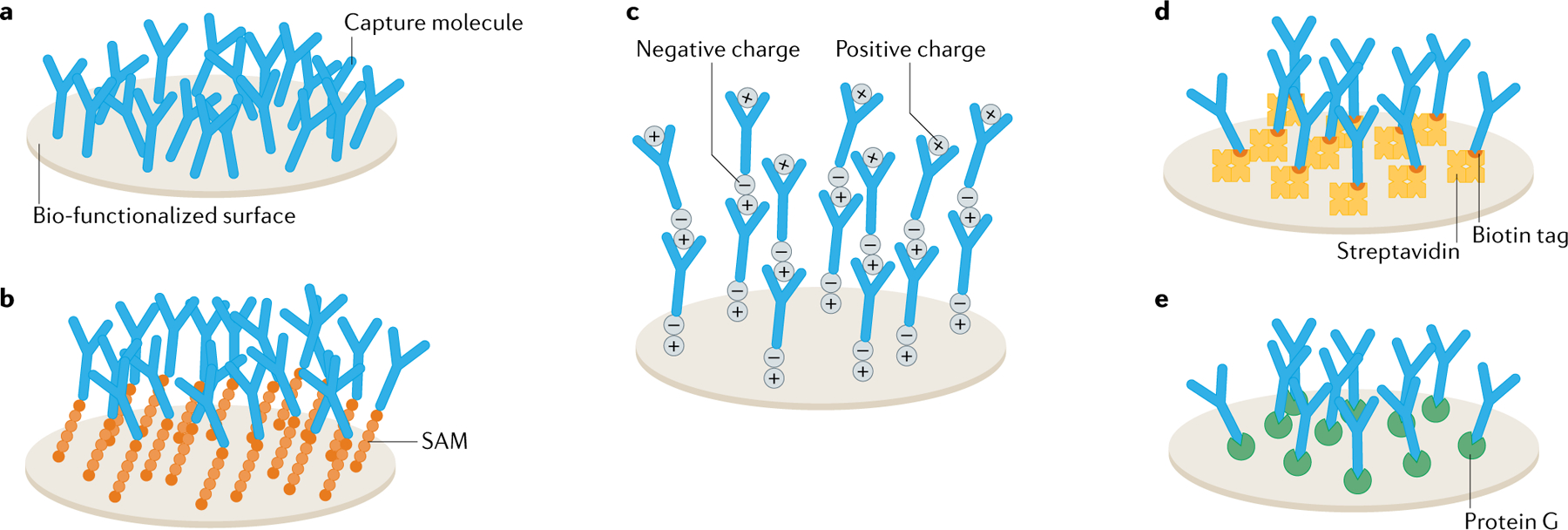

A fundamental advantage of EGT-based bioelectronics stems from the local bioelectric signal transduction and amplification, which results in an improved signal-to-noise ratio. The measured electrical characteristics provide meaningful information on the biological properties probed with the device. As a transistor class, the ‘identity card’ of EGTs is given by the transfer (ID−VG) and output (ID−VD) characteristics, where ID is the drain current. An example of typical transfer and output characteristics of a hole-conducting (p-type) ion-permeable EGT and an electron-conducting (n-type) ion-impermeable EGT are displayed in FIG. 6a–d, respectively. It is important to note that the maximum applied voltages (|VG| and |VD|) should be below 1 V in order to prevent electrolysis of the electrolyte solution15,115,170. In addition, faradaic currents, typically displayed in a gate current IG, should be monitored and minimized during the experiments. For instance, faradaic side reactions during the EGT operation are possible owing to redox-active materials that can produce reactive side products, which may be harmful for the local biological environment and may accelerate device degradation115,171.

Fig. 6 |. Representative electrical characteristics of EGTs.

a | Typical transfer characteristics ID−VG at various VD of a p-type ion-permeable and depletion-mode electrolyte-gated transistor (EGT) (full lines). Transconductance gm and threshold voltage VT are highlighted (dashed line) in the case VD = −0.3 V. b | Typical transfer characteristics ID−VG at various VD of an n-type ion-impermeable and accumulation-mode EGT (full lines). c | Typical output characteristics ID−VD at various VG of a p-type ion-permeable and depletion-mode EGT. d | Typical output characteristics ID−VD at various VG of an n-type ion-impermeable and accumulation-mode EGT. e | Schematic lumped circuit model of a bare EGT (without bio-layer). f | Typical gm as a function of VG at several VD in the case of a p-type ion-permeable and depletion-mode EGT. Maximum of gm depends on both VG and VD. g | Typical gm as a function of VG at several VD in the case of an n-type ion-impermeable and accumulation-mode EGT. h | EGT lumped model highlighting the bio-layer on the gate electrode. Position of the bio-layer schematically depicted by the cyan area. i | Typical ID−VG curves in the case of selective bio-recognition taking place at the bio-layer on the gate electrode. By the way of example, these characteristics could be obtained with EGT biosensors with bio-functionalized gate. j | EGT lumped model highlighting the bio-layer on the channel. k | Typical ID−VG curves in the case of biological events taking place on the channel mainly result in variation of bio-layer capacitance. These characteristics could be obtained when EGT is used for cell monitoring as well as EGT biosensors. l | EGT lumped model highlighting the bio-layer embedded in the electrolyte. m | Typical transient response obtained when the bio-layer results in a variation of the ionic resistance and/or capacitance, as for example when monitoring the cells grow and barrier integrity. n | EGT lumped model highlighting the external electrical connection between the EGT and the biology during electrophysiological measurements. o | Typical frequency response of an ion-permeable EGT. CCH, transistor channel capacitance; CG, gate capacitance; ID, drain current; REL, electrolyte resistance; RG, gate resistance; VD, drain voltage; VG, gate voltage; VS, source voltage.

EGT model and parameters.

As displayed in FIG. 6e, the EGT is modelled with lumped electrical components corresponding to three main elements: a transistor channel with capacitance CCH; an electrolyte with resistance REL; and a gate electrode with capacitance CG connected in parallel to resistance RG. CCH models the single or volumetric EDL capacitance, REL accounts for the ion movement into the electrolyte upon the application of VG, CG describes polarizable gate electrodes, such as gold and platinum electrodes, and RG describes non-polarizable gate electrodes, such as Ag/AgCl electrodes91,172. The very same material electrode can be polarizable or non-polarizable depending on the electrolyte used and the potential applied. Assuming there is a constant carrier mobility, μ, of the electronic charges into the channel and that the EGT operates under steady-state conditions, such that transient current is vanished and REL can be disregarded accordingly, the drain current can be calculated. This current can be computed by solving the Poisson drift-diffusion and current continuity equations, and in the case of an electron-transporting semiconductor (n-type EGT) reads91,172–174:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where W and L are the channel width and length, respectively, and C = CGCCH(CG + CCH)−1ACH−1 in the case of a polarizable gate electrode and C = CCHACH−1 in the case of a non-polarizable gate electrode. ACH is the area of the channel; CCH is the capacitance at the electrolyte/channel side. It is worth noting that CCH = CEDLWL, where CEDL is the EDL capacitance per unit area in the case of ion-impermeable — single interface — EGTs, and CCH = CVWLt, where CV is the volumetric capacitance in the case of ion-permeable EGTs and t is the semiconductor thickness. Thus, the interface and volumetric capacitances can be unified considering that the overall capacitance per unit area results as CEDL = CVt in the case of a volumetric capacitance EGT. VT is the threshold accounting for various physical parameters of the materials, including, for example, the Fermi energy level of the semiconductor, the bulk ion concentration of the electrolyte, fixed charges into the polymer and the gate work function24,175. λ is the channel length modulation parameter (λ ∝ L−1) and accounts for the shortening of the accumulated channel when the EGT is operated at saturation. The large gating capacitance C, typically about 1–100 10−6 F cm−2, results in almost flat ID−VD characteristics176 (as shown with FIG. 6c at VD < −0.5 V and FIG. 6d at VD > 0.5 V). However, λ can be neglected when the EGT is used as a bioelectronic transducer but remains a key parameter when the EGT is used in an amplifier topology73,83,114,177–179. Finally, Eqs. 1 and 2 can be rewritten for a p-type EGT by simply substituting VG with −VG, VD with −VD and ID with −ID.

Polarizable.

Characterized by a charge separation at the electrode–electrolyte interface and electrically equivalent to a capacitor.

Non-polarizable.

Characterized by no charge separation and electrically equivalent to a resistor.

Focusing on the transfer characteristics, the current ID is modulated by VG and the transconductance gm = dID/dVG is a figure of merit quantifying the modulation efficiency and defining the intrinsic amplification180–182. gm can be calculated directly from a transfer characteristic (FIG. 6f,g), and when the EGT operates in a linear region where VG − VT > VD, gm is the slope of the ID−VG curve (Eq. 1; FIG. 6a, dashed line) whereas the intersect between the linear least squares approximation of ID and the VG axis represents VT (Eq. 1; FIG. 6a). Further, gm depends on the bias conditions, channel geometries (W, L and t), ion species moving into the electrolyte (radius of solvated ions and ion–semiconductor interaction), bio-layer properties (geometrical dimensions, electrical, mechanical, ionic, chemical and biological properties) and EGT bioelectronic architecture. As an example, FIG. 6f,g shows gm as a function of VG at various VD calculated from the ID−VG displayed in FIG. 6a and FIG. 6b, respectively. The maximum gm is of the order of hundreds or even thousands of micro-siemens (gm/W ~ 10–100 S m−1) in the case of ion-permeable EGTs6,180,183,184 (FIG. 6f) and of the order of tens of micro-siemens (gm/W ~ 1–10 S m−1) for ion-impermeable EGTs185–187 (FIG. 6g). The magnitude of gm is a hallmark of the ionic–electronic interaction in EGTs27,188–190 marking the large volumetric capacitance obtained in OECTs and internal ion-gated transistors.

Bioelectronic configurations.

When the biological layer is integrated into the EGT architecture, various configurations can be used to transduce and enhance the bioelectronic response. FIGURE 6h–o highlights various EGT-based bioelectronics used for the detection and monitoring of biological properties. More specifically, the bio-layer can be arranged on the gate electrode (FIG. 6h) or on the channel (FIG. 6j). These configurations are typically used for the detection of proteins, DNA, RNA, peptides, viruses and chemical molecules191–196, as well as for monitoring of cellular cultures117,147,197–199 and lipid bilayers200–202. The bio-layer of EGT-based biosensors is made of bio-receptors or chemical receptors specific for the target molecules being evaluated. The bio-layer embedded into the EGT is exposed to the analyte of interest, which in some cases could be directly used as the electrolyte5,66,203. To monitor cells, a layer of cells is grown or deposited on the EGT channel, and properties such as cell growth or cell differentiation processes can be tracked. When the bio-layer is positioned on the gate, a polarizable electrode is used, and RG is large and can be neglected. By contrast, if the bio-layer is positioned on the channel, both polarizable (CG can be disregarded) or non-polarizable gate electrodes can be used. Typical transfer characteristics obtained when the EGT is functionalized with bio-receptors and exposed to various fluids with different analyte concentrations are displayed in FIG. 6i (REFS50–53). In this example, the variation of VT as a function of the analyte concentration is displayed in a shift of the ID−VG characteristics. Typical variations of VT are of the order of tens of millivolts. These variations depend on the concentration range of the target molecule and could be attributed to the charge of the molecules detected50,58,204, Donnan’s equilibrium205,206 and/or conformational changes of the bio-layer51,164. More comprehensive and systematic studies would be needed along this research direction. Depending on the position of the bio-layer, it can be electrically described as a charged capacitor in series to the gate electrode or channel. FIGURE 6k shows typical transfer characteristics obtained when cells grow on the EGT channel, where gm lowers, resulting in a lowering of ID in this example. The bio-layer can be modelled as a resistor RCELL in parallel to a capacitor CCELL. The RCELL element accounts for the ion flux across the cell layers and the CCELL models the ion accumulation at the cell interfaces68,69,207,208. The lumped circuit elements describing the bio-layer — RCELL and CCELL — are connected in series to the EGT channel. Overall, EGT parameters can be affected by the biological events taking place in the bio-layer and a detailed model-based analysis can provide relevant information about the biology.

Another possible EGT bioelectronic architecture is obtained by integrating the bio-layer within the electrolyte (FIG. 6l). This topology is particularly relevant to prevent any direct interaction between the biology and the electronic material components, namely the gate and channel of the EGT. This configuration can be typically used for monitoring cell layer integrity67–69 where the cell culture is left on the Transwell filter and for selective detection of metal cations where an ion-selective membrane separates the analyte compartment from the electrolyte in contact with the EGT24,42–44,72,73. FIGURE 6m shows a typical transient response obtained with an EGT without and with the cells. A voltage pulse is applied as input at the gate, and the drain current as a function of time is measured as a response. The transient response provides information on the status of the cell barriers. In more detail, without cells the EGT response is fast and rapidly achieves the steady-state output. When the barriers are embedded into the EGT, the ion flux from the gate compartment and the channel compartment depends on the status of the cell barrier. The time constant of the EGT drain current response depends on the barrier integrity and enables the quantitative monitoring of the cell barrier integrity. A detailed analysis also requires inclusion of the equivalent circuit model of the cells into the EGT lumped model shown in FIG. 6l. In a simple yet effective approach, a non-polarizable electrode is used (CG can be disregarded and RG is small), and the cell layer integrated into the filter can be described with a resistor RCELL in parallel to a capacitor CCELL67,147,209.

The EGT finds relevant application also for electrophysiology. Here, the EGT amplification enables the local amplification of the electric bio-signals, measured by directly connecting the gate and source electrodes with the tissue (as depicted in FIG. 6n). By way of example, electrocardiography, electromyography and electro-oculography with high signal-to-noise ratio can be achieved with EGTs75,210–213. In addition, the small device footprint as well as the biocompatibility of the materials enable in vivo recording of the biopotentials generated by electrogenic cells, tissues and organs2,190,214–216. The EGT transconductance frequency response is another relevant parameter. A typical result is displayed in FIG. 6o. The signal-to-noise ratio increases by increasing the EGT amplification and, thus, the gm. In this respect, volumetric EGTs, namely OECTs and internal ion-gated transistors, provide superior performance owing to the enhanced volumetric response75,188. The other relevant parameter is the bandwidth of the EGT, and in the case of biopotentials the large gm operation should extend for at least about 1,000 Hz. We note that in conventional OECTs there is a trade-off between gm and the bandwidth as by increasing the volumetric capacitance, gm increases but the transistor gets slower.

Electrocardiography.

The process of recording the electrical signals of the heart.

Electromyography.

The process of recording the electrical signals of skeletal muscles.

Electro-oculography.

The process of recording the electrical signals of eye.

Data analysis.

To date, data analysis is based on the description of the measurements with drain current models (Eqs. 1 and 2) and simple numerical calculations displayed on the ionic–electronic EGT circuit schematic (FIG. 6e). The bio-layer is included in the EGT circuit model and routinely described as an ionic resistor in parallel to a capacitor. Then, the overall lumped circuit models can be implemented using technical programming languages such as MATLAB, Python, C++ or other. However, to date there is a lack of standard software tools for data analysis.

Applications

In this section, we discuss relevant EGT-based bioelectronic applications including monitoring of two-dimensional and three-dimensional cells, ultra-sensitive biosensors, electrophysiology, synaptic and neuromorphic interfaces, prosthetics and robotics. The applications presented highlight specific features of EGTs, including seamless three-dimensional integration with cells, wide-area biosensors with a limit of detection of 1 ± 1 molecules, ionic to electronic in situ transduction and amplification for local electrophysiological recording with biocompatible conformable EGTs in contact with tissues and organs, neuromorphic bio-interfaces and artificial synapses with a focus on an artificial afferent nerve.

Two-dimensional and three-dimensional cell monitoring.

Cell monitoring based on electrodes has been described for several decades, where planar electrodes can be used to characterize cell adhesion, growth and differentiation217. In parallel, tissues were studied using opposing electrodes to measure resistance of a tissue and the ability to form compartments218. Multi-electrode/transistor arrays are a third way of integrating cells with electrical monitoring219, typically recording extracellular potentials from electrogenic cells such as neurons or cardiac cells220. EGTs used for monitoring cells in vitro have followed these three trends: planar devices for monitoring cells using, for example, graphene transistors173, carbon nanotube transistors147, organic transistors with a liquid gate221 and OECTs222; opposing set-ups where the gate is separated from the source, channel and drain, for measuring trans-epithelial/endothelial resistance67,69; and multi-transistor arrays for monitoring electrogenic cells223,224.

Early examples of integration of cells with EGTs focused on culturing cells on devices, and ensuring cytocompatibility225. There is a trade-off between the optimized device from a materials side and the biological side, and all materials exposed to the cell culture medium, which is a harsh environment for devices, must be considered. To ensure monomers or residual resists do not leach, stability experiments have to be run over time frames similar to cellular experiments, which typically take days to weeks226. In EGTs, the channel can be optically transparent allowing combined optical and electronic in situ monitoring, a property highly valued by cell biologists227,228.

Cell biology is currently focusing on growing cells in three dimensions, and also mimicking the physical environment of cells. In addition, measuring the electrical properties of cells requires intimate contact between the cell and the electrode229. Although examples have been reported of EGTs used to measure properties of three-dimensional cultures such as spheroids, the sensitivity is limited and typical EGTs will interface with only the outermost cells in the spheroid166. One interesting approach is to use bendable transistor arrays to bend around the three-dimensional shape of the tissue230 (FIG. 7a,b). Another approach involves processing conductive polymers into three-dimensional porous scaffolds, enabling the integration of such electrodes into EGT channels231. These devices show a very slow transient response compared with microfabricated EGTs, but cells can be grown within the electrode, where individual cells can make contact with the volume of the channel232,233 (FIG. 7b). Such configurations enable growth of complicated multicellular tissues and organs, allowing EGTs to keep pace with developments in cell biology234. The porous scaffolds can also be tuned to have mechanical properties that mimic the tissue235. Finally, the ease of mixing of biological molecules, such as extracellular matrix proteins or sugars, may enhance cell adhesion and could be used to allow spatio-temporal cell growth on a device236.

Fig. 7 |. Three-dimensional cell monitoring, ultra-sensitive biosensors and in vivo electrophysiology using EGTs.

a | Three-dimensional confocal microscopy image of cardiac spheroid labelled with Ca2+ indicator dye (Fluo-4, green fluorescence) encapsulated by the 3D-SR-BA. The numbers are the micro-electrodes labels. Scale bar, 50 μm. b | Three-dimensional conducting polymer transistors in a tube named Tubistor. The device is composed of a tubular cavity with three openings, gold-coated flexible electrodes used as source and drain contacts of the channel fixed inside the tube, and a poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) channel. Length L = 1 mm and width W = 4 mm. Gate electrode embedded inside the tube. c | COVID-19 electrolyte-gated transistor (EGT) sensor operation procedure. Graphene serves a sensing material and SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody is covalently attached to the graphene sheet via 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester, which is an interfacing molecule serving as probe linker. d | Single-Molecule assay with a large-area Transistor (SiMoT) EGT transfer characteristics. Dashed grey curve corresponds to anti-human IgG capturing layer incubated in the bare phosphate saline buffer (PBS) solution. Same gate is further exposed, in sequence, to PBS standard solutions of IgG at different concentrations. e | Wiring diagram for electrocardiographic recording with bio-resorbable EGT operated in direct contact with the skin and photograph of four organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) showing their adaptability when attached to human skin. f | Micrograph of an implantable device with four EGTs. g | Micrograph of an EGT conforming to human scalp (scale bar, 2 mm). BSA, bovine serum albumen; ID, drain current; SAM, self-assembled monolayer; VDS, drain–source voltage; VG, gate voltage; VGS, gate–source voltage; VT, threshold voltage. Part a reprinted with permission of AAAS from REF.230. © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee AAAS. Distributed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Part b reprinted with permission of AAAS from REF.233. © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee AAAS. Distributed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/). Part c adapted with permission from REF.66, ACS. Part d adapted from REF.164, Springer Nature Limited. Part e adapted with permission from REF.213, Wiley. Part f adapted from REF.75, Springer Nature Limited. Part g reprinted with permission of AAAS from REF.74. © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee AAAS. Distributed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/).

Spheroids.

Dense three-dimensional assemblies of cells grown in gels composed of extracellular matrix.

Ultra-sensitive biosensors.

The ultra-sensitive detection of markers including proteins, peptides, metabolites and nucleic acids in peripheral biofluids, such as blood or saliva, can lead to advances in early diagnostic technologies178,237. Such tools are minimally invasive and suitable for point-of-care and resource-limited settings238. Single-molecule detection can be performed with either nanoscale interfaces or large millimetre wide-area interfaces.

Point-of-care.

Medical diagnostic testing at the place and time of the patient care.

In nanometric transducers, the device comprises a single probe that binds one of the molecules in the assayed solution. This approach can reveal a single binding event but cannot be used for the detection of a fluid encompassing markers below the picomolar concentration239. Indeed, when the marker to be detected is dispersed in a volume of 10–100 μl around a nanoscale interface, an encounter between the two is very unlikely. For example, days can be needed for only a few molecules to impinge on a nanometric interface in a femtomolar concentrated solution — ~ 106 molecules in 100 μl (REFS237,240).

Large-area or wide-field interfaces164,237, with their higher geometrical cross section, offer a fast (time to results of a few minutes) viable solution for molecule detection at the physical limit of a single molecule or few molecules, as shown by several examples that involve both inorganic and organic EGT devices241. FIGURE 7c shows graphene-based EGT biosensors for label-free ultra-sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 (REF.66). The EGT sensor comprises graphene sheets functionalized with the antibody that specifically binds the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. The performance level was tested against the antigen protein, the cultured virus and nasopharyngeal swab specimens from patients with COVID-19, with limits of detection down to about 250 copies in 1 ml. Selectivity was demonstrated with MERS-CoV control experiments and patients who were both positive and negative were considered. Control experiments are essential to assess the biosensor response because other relevant effects could play a role. For example, depending on the surface properties, graphene-based EGTs can be sensitive or insensitive to the pH of the analyte solution242.

Single-Molecule assay with a large-area Transistor (SiMoT) technology, involving an OSC-based EGT, has enabled lowering the detection limit down to tens of zeptomoles (10−21 M)51,196,243,244. This method is considered a single-molecule assay as 100 μl of a 10–20 zM solution includes 1 ± 1 molecules164. FIGURE 7d shows typical transfer characteristics measured in phosphate saline buffer (PBS) solution (red line) and in standard solutions with concentration ranging from 60 to 6 × 106 zM. In this approach, the gate electrode work function (ϕ) decreases at the different functionalization steps and after human IgG binding. The variation of ϕ is correlated to the measured threshold voltage (VT) shift. At the physical limit, which is one molecule in the fluid assayed, the sensing was accomplished with 1011–1012 recognition elements (anti-IgG) covalently attached at a millimetre-wide gate electrode and detections were possible after 10 min of incubation in the solution to be assayed239. SiMoT has set an unbeaten reported record in label-free single-molecule detection and the detection of proteins such as HIV-p24, CRP, IgG, IgM, peptides and genomic markers has also been demonstrated in serum51,164,196,243,244.

Electrophysiology.

The electrophysiological activity of an organ and its surrounding tissue is a relevant application of EGTs in the field of health-care monitoring216. The EGT amplification has to be maximized to provide large local amplification of the bio-signals, which should be within a bandwidth of the order of 1,000 Hz for high-fidelity and low-noise measurements. In applications where the EGT is outside the body, as for example in electrocardiography, electromyography and electro-oculography, a reliable contact with the skin is essential and is typically achieved by using thin and conformable substrates. FIGURE 7e shows an array of EGTs operated in direct contact with the skin for electrocardiographic recording. In this example, the biocompatible conductive polymer PEDOT:PSS and PLGA is used for the channel and substrate, respectively. The photograph shown in FIG. 7e (REF.213) highlights its conformability to human skin.

Electrophysiology is also extensively used in neuroscience research and in the diagnosis of disorders of the brain, heart and muscles. Electrodes placed on the skin or implanted, such as gel-assisted Ag/AgCl and Pt/Ir, respectively, measure signals in the brain, which can range from a few microvolts for evoked potentials to several millivolts for epileptic seizures, at frequencies of 1–1,000 Hz (REF.245). Recent advances in electronics have led to a wealth of new implantable and wearable transducers for health and human performance monitoring246. EGTs are prominent here39,247–249 because they can locally transduce and amplify the recorded signal at the source, for example when conformed to the brain surface and on organs for in vivo recording, rendering it more robust towards downstream noise. EGTs convert a voltage signal at the gate into a modulation in the drain current. The power of the signal is amplified by a factor that depends on the transconductance, which can be >50 dB for a simple OECT180.

The first application of EGTs in in vivo electrophysiology involved the use of using PEDOT:PSS OECTs to record epileptic seizures in rats. Compared with electrodes of similar size, these OECTs afforded a signal-to-noise ratio more than 20 dB higher212,216. In a major development, the frequency response and transconductance of OECTs were significantly improved by engineering channels with internal ion reservoirs, which enabled single neuron recordings in the cortex of rats75 (FIG. 7f). Further experiments involved arrays of PEDOT:PSS OECTs on transparent and stretchable substrates that were employed to map the heart and the brain250,251. PEDOT:PSS OECTs have also been used to stimulate cortical neurons252. A similar path was followed for graphene-based EGTs, where individual devices253, as well as passive and actively multiplexed arrays40,254–257, were used to record and map cortical activity. Other notable examples include brain recordings made with injectable nanowire transistors258 and electrolyte-gated metal oxide semiconductor field-effect transistors259.

EGTs were first applied in cutaneous electrophysiology to measure cardiac activity using a PEDOT:PSS OECT that was attached to the skin of volunteers with the aid of a gel213. The use of non-volatile gels enabled stable recordings over several days260. A novel organic EGT geometry based on conducting fibres encapsulated in a soft biodegradable polymer was integrated with textiles and used to record cardiac activity261. The high transconductance of OECTs with internal ion reservoirs allowed miniaturization and direct attachment between hair follicles for long-term measurements of brain activity, as displayed in FIG. 7g (REF.74). A different method of coupling EGTs to the body involves the use of a cutaneous electrode as the gate, which has afforded applications of PEDOT:PSS OECTs in electrocardiography, electro-oculography and electroencephalography262. Tuning the thickness of the channel was used to navigate the gain versus bandwidth trade-off188.

Compared with electrodes, which show high impedance at low frequencies, the low-pass filter characteristics of EGTs make them particularly suitable for electrophysiology recordings and transducer miniaturization. The key issues with EGTs include the high power consumption, and the fact that the signal is in the form of a current and, thereby, incompatible with standard electrophysiology amplifiers. However, encouragingly, an improved power consumption was observed when an EGT was operated in a sub-threshold regime263. Moreover, a simple circuit with a drain resistor was reported as an efficient method to convert the output current into voltage177. Despite these reports, there is still room for creative solutions on these fronts.

Synaptic and neuromorphic bio-interfaces.

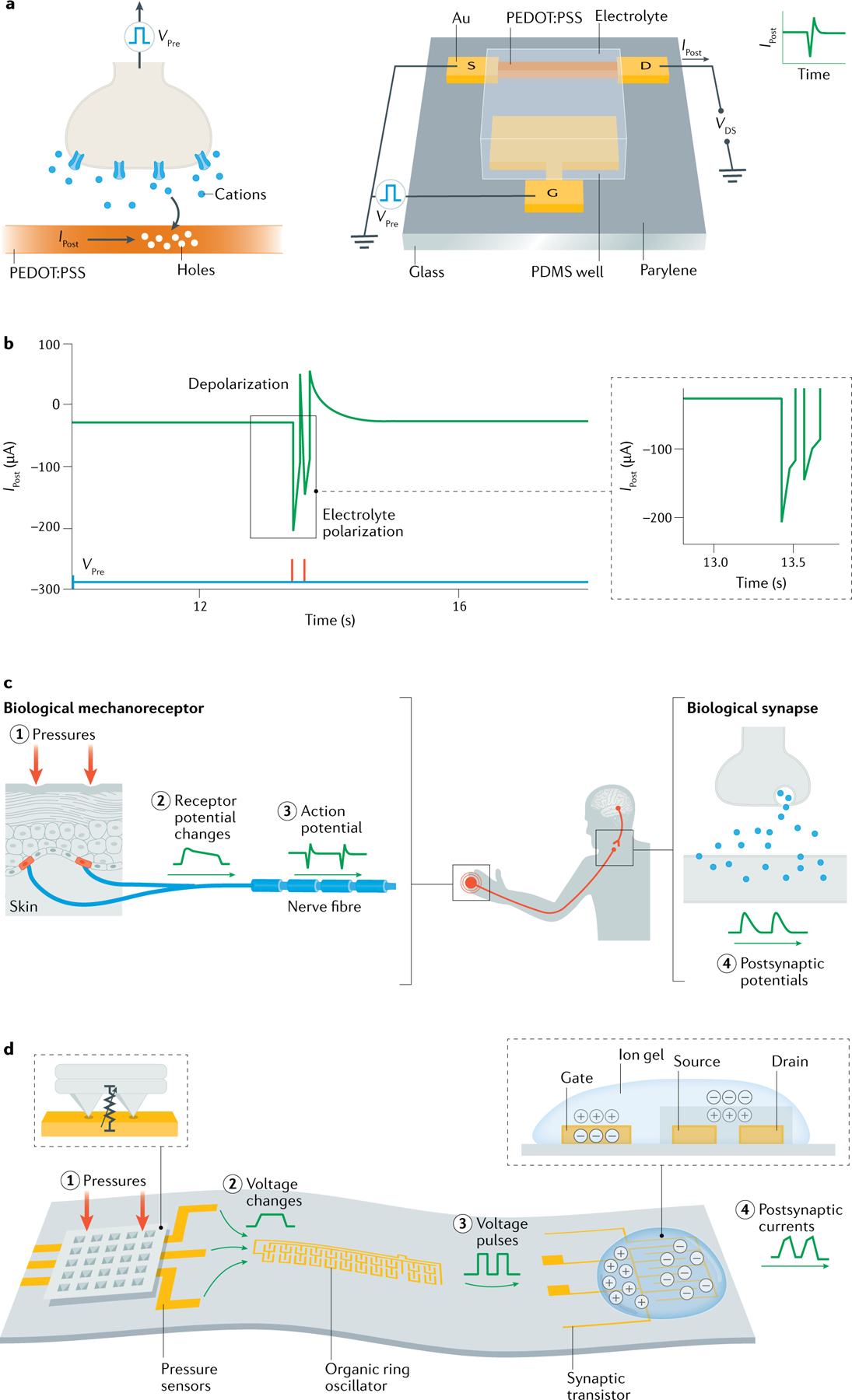

Neuromorphic EGTs are an emerging platform for synaptic electronics because EGTs offer large capacitance (up to 500 μF cm−2) for efficiently coupling the gate to the channel264–266. The large and tunable ionic–electronic conductance combined with low power consumption and decoupled ‘write’ and ‘read’ operations are key advantages of EGTs compared with dielectric transistors and two-terminal devices267,268. The analogy between neurotransmitters diffusing through the synaptic cleft and ions drifting in and out of the channel of ion-permeable EGTs, such as OECTs (FIG. 8a), is an attractive approach to understand the working mechanism of OECT-based artificial synapses269. As displayed in FIG. 8b, the postsynaptic drain current shows paired pulse depression behaviour as a function of time (IPost) by applying a pair of presynaptic pulses (VPre) at the gate electrode of an OECT. In addition, the hysteretic behaviour of OECT electrical characteristics is due to the relatively slow kinetics of ion penetration into the polymer. This behaviour, in turn, results in an inherently volatile operation with a slow timescale. Enhanced chemical stability of the polymers in the electrolyte and reduced parasitic leakage currents through the external circuit270 are essential to improve the retention time. Using high-capacitance polarizable gate electrodes essentially transforms the OECT into a capacitor and, relying on the slow discharge of this capacitor, a volatile artificial synapse for neuromorphic computing has been demonstrated.

Fig. 8 |. Synaptics and neuromorphics with EGTs.

a | Schematic synaptic organic electrochemical transistor (OECT) in analogy with a biological synapse. b | Example of a pair of presynaptic pulses (VPre) applied at the OECT gate electrode and the postsynaptic drain current (IPost) measured as a function of time. Amplitude, A, of IPost exhibits paired pulse depression behaviour. c | Biological afferent nerve stimulated by pressure. Action potentials from multiple nerve fibres combine through synapses and contribute to information processing. d | Schematic structure of an artificial afferent nerve. EGT, electrolyte-gated transistor; PEDOT:PSS, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate; VDS, drain–source voltage. Parts a and b adapted with permission from REF.274, Wiley. Parts c and d adapted with permission from REF.282, AAAS.

The memristive behaviour of the polyaniline devices was used to demonstrate XOR logic classification271, to simulate the dysfunction associated with Alzheimer disease272 and, more recently, to couple electrically with cortical neurons273. Further developments of the use of the EGT for synaptic operations involved multiple gate or multiple channel configurations49,270,274,275. Indeed, an electrolyte common to multiple channels enables the emulation of the common electrochemical environment in which biological neural networks are typically immersed giving rise to mutual feedbacks45. In this context, the use of multiple inputs operating on a single output, or the use of a single input affecting multiple outputs, can simulate functions such as orientation selectivity276, homeoplasticity277 and coordinated voltage oscillations79.

Memristive.

Relating to a non-linear two-terminal electrical component linking magnetic flux and electric charge.

One unique aspect of implementing artificial synapses with redox-active polymers is the ability to couple electrochemistry on biomolecules with a purely electronic function, using biocompatible materials. Dopamine secreted by cells could be used to induce long-term potentiation embodied as a non-volatile conductance modulation across a device channel48, thereby demonstrating a key synaptic functionality across the biotic/abiotic interface. Integration of neuromorphic devices with living matter is a promising research direction. Other important future areas of research involve applications where some amount of computation must be performed untethered and ‘at the edge’, which for instance would be the case for the sensory arm of a soft robot. The octopus provides an interesting model along these lines, as its tentacles contain a relatively large number of neurons and are thus capable of sensing, local computation and learning without involving the central brain.

Prosthetics and robotics.

The EGT-based synaptic device can be applied to neuromorphic signal processing from multiple sensors, which is attractive for e-skin prosthetic and robotic applications because many sensors are required to detect the shape, size, texture and consistency of objects. In addition, immediate decisions on required actions need to be made based on detected information, especially for example a future threat. Therefore, fast processing of a large amount of data is required. Conventional data collection and processing methods scan each sensor individually to construct the information, but this process is slow and power-intensive when many sensors are involved. In biological nervous systems, synapses process information with a distributed, parallel and event-driven computation approach. For example, the tactile information in a biological somatosensory system (FIG. 8c) is processed by integrating signals from multiple tactile inputs at the synapses in order to partially process the information before delivering it to the brain278,279. To mimic slow-adapting type I mechanoreceptor responses to tactile pressure input signals, the generated spike train frequency should increase with input pressure280. Recently, by combining a resistive pressure sensor with organic transistor ring oscillators, a pressure-dependent tunable frequency — in which the higher the pressure, the higher the ring oscillator frequency — has been demonstrated and then extended to multiple pressure sensors281,282 (FIG. 8d). The outputs were further used as gate inputs of a synaptic EGT, and by properly selecting the polymer semiconductor it was possible to mimic the synapsis of biological afferent nerves279,283. This artificial afferent neuron (FIG. 8d) consumed ~8 mW in the OFF state and ~25 mW in the ON state282. The EGT synaptic transistor can be gated by multiple inputs coming from multiple ring oscillators and combines the information. The signals from two pressure sensors were combined in a postsynaptic current with two frequency components corresponding to the two inputs, which is analogous to the connection of postsynaptic neuron dendrites with biological synapses from multiple neurons. This approach can be applied to various types of sensors, such as temperature, strain or light284–286, as well as to mimic various sensory functions of biological systems, such as smell, taste and vision285–288.

Reproducibility and data deposition