Abstract

Maintaining blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity is crucial for the homeostasis of the central nervous system (CNS). Structurally comprising the BBB, brain endothelial cells interact with pericytes, astrocytes, neurons, microglia, and perivascular macrophages in the neurovascular unit (NVU). Brain ischemia unleashes a profound neuroinflammatory response to remove the damaged tissue and prepare the brain for repair. However, the intense neuroinflammation occurring during the acute phase of stroke is associated with BBB breakdown, neuronal injury, and worse neurological outcomes. Here, we critically discuss the role of neuroinflammation in ischemic stroke pathology, focusing on the BBB and the interactions between CNS and peripheral immune responses. We highlight inflammation-driven injury mechanisms in stroke, including oxidative stress, increased matrix metalloproteinase production, microglial activation, and infiltration of peripheral immune cells into the ischemic tissue. We provide an updated overview of imaging techniques for in vivo detection of BBB permeability, leukocyte infiltration, microglial activation, and upregulation of cell adhesion molecules following ischemic brain injury. We discuss the possibility of clinical implementation of imaging modalities to assess stroke-associated neuroinflammation with the potential to provide image-guided diagnosis and treatment. We summarize the results from several clinical studies evaluating the efficacy of anti-inflammatory interventions in stroke. Although convincing preclinical evidence suggests that neuroinflammation is a promising target for ischemic stroke, thus far, translating these results into the clinical setting has proved difficult. Due to the dual role of inflammation in the progression of ischemic damage, more research is needed to mechanistically understand when the neuroinflammatory response begins the transition from injury to repair. This could have important implications for ischemic stroke treatment by informing time- and context-specific therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: neuroinflammation, blood-brain barrier, neurovascular unit, ischemic stroke, imaging, peripheral immune cells, microglia

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is characterized by a highly interconnected and multiphasic neuropathological cascade of events in which an intense and protracted inflammatory response plays a crucial role in worsening brain injury. A large body of evidence indicates that post-ischemic inflammation is associated with acute blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption, vasogenic edema, hemorrhagic transformation, and worse neurological outcomes in animals and humans. While neuroinflammation contributes to brain damage in the early phase of ischemic stroke, the inflammatory response could promote recovery at late stages by facilitating neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and neuronal plasticity. A better mechanistic understanding of how the neuroinflammatory response transitions from injury to repair would help identify novel strategies to intervene therapeutically in a time- and context-specific manner.

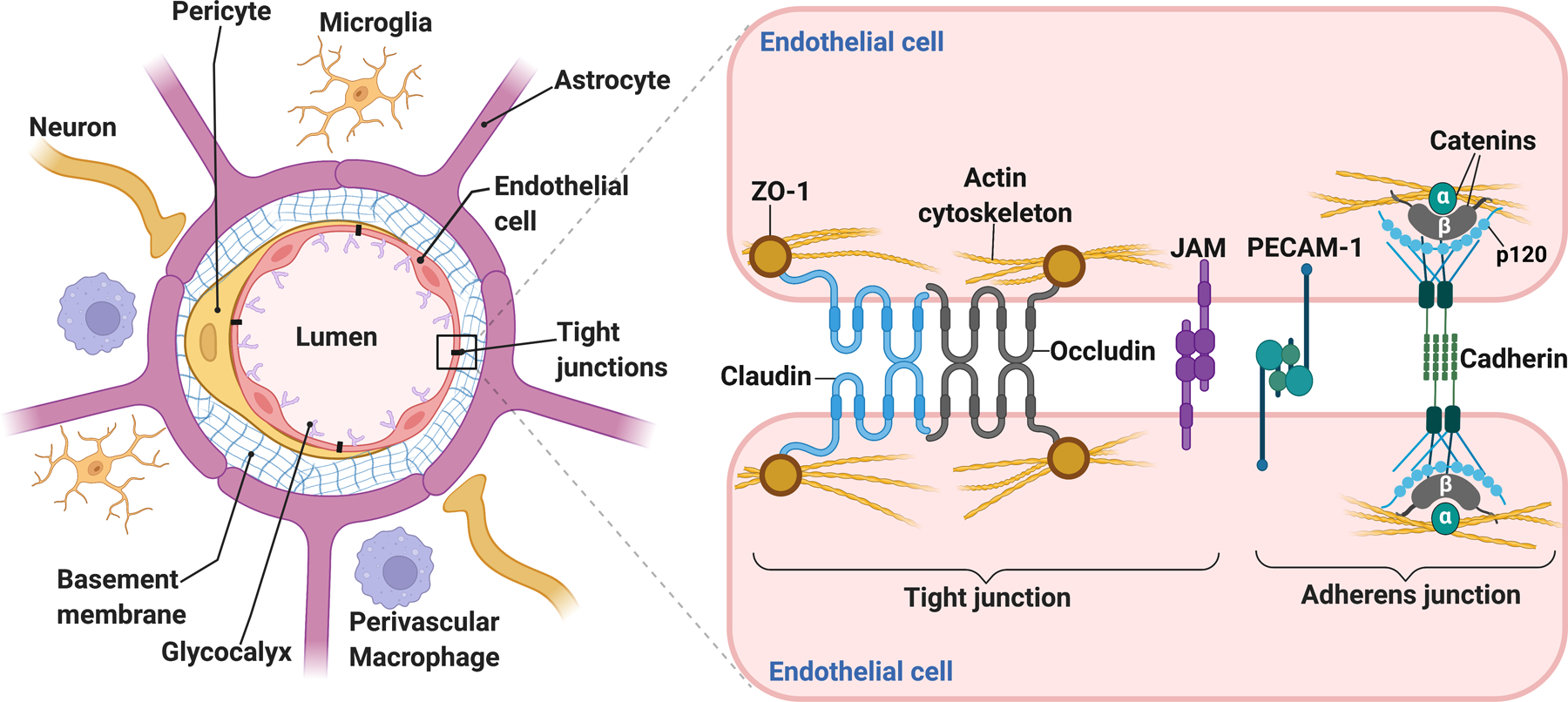

The BBB is a highly selective structural and functional barrier between the blood and the CNS, creating a unique microenvironment required for normal brain function and homeostasis. Comprising the BBB, brain endothelial cells interact with astrocytes, pericytes, nerve terminals, microglia, and perivascular macrophages in the neurovascular unit (NVU). The NVU concept was put forward to highlight the complex interactions among all the cells associated with the BBB (Figure 1)1–3. A more detailed description of the structural and functional aspects of the BBB is provided in the Supplemental Material.

Figure 1. Schematic of the neurovascular unit (NVU).

Anatomically comprising the blood-brain barrier (BBB), the endothelial cells are surrounded by pericytes, astrocytic end-feet processes, neuronal terminals, and the basement membrane, comprising extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins that provide mechanical support and facilitate cell-ECM and cell-cell interactions at the NVU. Perivascular microglial cells contact the brain vasculature and modulate BBB permeability. Perivascular macrophages are key mediators in immune surveillance and are located in penetrating arterioles and post-capillary venules. Situated on the luminal side of the endothelial cells, the glycocalyx is composed of proteoglycans and their linked glycosaminoglycan chains, including heparan sulfate and hyaluronan. Glycocalyx degradation and shedding dramatically increase BBB permeability. An intricate complex of tight junction and adherens junction proteins “zip” together adjacent endothelial cells, conferring the low permeability of the BBB under physiological conditions. Claudins and occludin form the seal between endothelial cells, and they associate with the actin cytoskeleton via accessory proteins, such as ZO-1. Junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs) form part of the tight junctions and facilitate the attachment of endothelial cell membranes. The brain vasculature expresses high levels of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1), also known as CD31, which contributes to BBB function. Vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) and catenins are the main structural proteins comprising the adherens junctions. They are necessary to form tight junctions and provide physical integrity to the BBB.

This review provides a critical evaluation of the role of neuroinflammation in ischemic stroke, with a particular emphasis on the BBB and peripheral immune responses. We provide an overview of the functional and structural elements determining the BBB phenotype and how this is disrupted after stroke by inflammation-driven mechanisms, including oxidative stress, matrix metalloproteinases, microglial activation, and peripheral immune cell invasion into the ischemic tissue. We discuss the role of peripheral immune cells and their cytokines in the resolution and recovery following ischemic stroke. We next provide an overview of methodologies and applications of medical imaging modalities to assess neuroinflammation after ischemic stroke and their potential implementation in clinical practice for image-guided diagnosis and treatment. We finally discuss the results of several clinical interventional trials targeting inflammatory pathways to reduce brain injury and improve outcomes.

Mechanisms of inflammation-driven BBB damage in ischemic stroke

Oxidative stress

As an essential contributor to cell death and BBB injury, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production occurs shortly after vessel occlusion and is closely associated with the stroke-induced inflammatory response. Stroke also impairs endogenous antioxidant mechanisms, which leads to oxidative stress. ROS directly damage endothelial cells of the BBB and contribute to vasogenic edema. The superoxide radical (O2−.) is a primary ROS involved in increased vascular permeability after cerebral ischemia4 and O2−. radical scavenging reduces stroke-induced BBB permeability and vasogenic edema4.

In a transient mouse MCAO model, transgenic overexpression of the intracellular form of glutathione peroxidase (GPx1) reduces infarct size, decreases MMP-9, and prevents BBB disruption5. Conversely, GPx1-null mice display larger infarcts and a dramatic exacerbation of BBB leakage compared with wild-type controls6.

The Nox2/gp91phox containing NADPH oxidase in microglia and infiltrating immune cells is a significant source of ROS after transient cerebral ischemia. Compared to wild-type controls, gp91phox knockout mice display smaller lesions and reduced BBB breakdown after ischemic stroke7, suggesting that NADPH oxidase-driven oxidative stress plays a critical role in BBB injury in stroke.

Depending on the cell type in which it is generated, nitric oxide (NO) could have beneficial or deleterious effects after cerebral ischemia8. Increased NO formation by neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) is detrimental in the context of ischemic stroke9. Endothelial-derived NO is neuroprotective in models of ischemic brain injury through mechanisms involving increased CBF and attenuation of peripheral leukocyte invasion8,10. However, excessive eNOS-derived NO generation under oxidative stress conditions could be detrimental via the formation of peroxynitrite, the product of the reaction between NO and O2−. radical8. After stroke, peroxynitrite formation is dramatically increased in microvessels and astrocytic end-foot processes, which is associated with BBB disruption and active MMP-9 labeling, suggesting an association between peroxynitrite and vascular damage8.

Matrix Metalloproteinases

As critical mediators of cerebrovascular damage after stroke, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of zinc-dependent proteases that are rapidly increased in activated microglia, astrocytes, and extravasated leukocytes, particularly neutrophils. Among the MMPs, MMP-2 (gelatinase A), MMP-9 (gelatinase B), MMP-3 (stromelysin-1), and MMP-12 have been extensively documented to contribute to BBB damage in stroke11. MMP-dependent BBB disruption results from the degradation of the basal lamina and TJPs by active MMPs. The MMPs exist as zymogens, and several mechanisms activate these proteases during neuroinflammatory and hypoxic conditions. MMP-14 (also known as MT1-MMP) converts pro-MMP-2 into active MMP-2, and proMMP-9 can be activated by MMP-3 or oxidative modification11.

Poor neurological function and hemorrhagic transformation in stroke patients correlate with elevated plasma MMP-9 levels following rtPA thrombolysis12. BBB breakdown after stroke in humans correlates with increased MMP-913, and postmortem studies have found MMP-9 mainly localized in infiltrating neutrophils, microglia, and brain endothelium14. As the injury progresses, neutrophils are the primary source of active MMP-9 in stroke15, and release of MMP-9 from human neutrophils is significantly increased by tPA. This mechanism contributes to hemorrhagic complications following rtPA thrombolytic therapy16.

There is a sustained increase in MMP-2 and MMP-9 after transient MCAO, and post-ischemic administration of MMP inhibitors reduces BBB opening and stroke damage11. MMP-9 genetic deletion results in better functional outcomes and smaller infarcts in models of ischemic stroke17. Genetic or pharmacological inactivation of MMP-9 leads to less degradation of tight junction proteins and neurovascular protection17.

Most studies have focused on gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) in stroke pathophysiology. However, MMP-3 and MMP-12 are also implicated in neuroinflammation-mediated BBB damage after stroke. Compared to wild-type mice, MMP-3 knockout mice have reduced BBB leakage following delayed rtPA thrombolysis treatment18. In a model of transient cerebral ischemia in rats, MMP-12 levels are dramatically increased, and systemic administration of a plasmid expressing MMP-12 shRNA reduces stroke volume and BBB permeability19.

Targeting MMPs to reduce stroke injury has been proven difficult due to the lack of selective inhibitors with low toxicity. In addition to mediating a detrimental role in the acute stroke phase, MMPs are beneficial in the recovery phase by enhancing neuronal plasticity and vascular remodeling20,21.

Role of inflammatory mediators released by microglia and peripheral immune cells in acute ischemic brain injury

Dying cells in the ischemic brain release many molecules that activate the surrounding viable tissue or infiltrating cells. These molecules include, among others: ATP, high-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1), uridine triphosphate, and heat shock proteins22. These danger signals or danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) activate immune cells through the engagement of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as Toll-like receptor family (TLR1 to 13) and suppression of tumorigenicity 2 (ST2). As a second signal, they can activate purinergic receptors and intracellularly the inflammasome family, which induces secretion of proinflammatory cytokines by innate immune cells22. One example of such a pathway is the ATP/P2X7 axis, which can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and secretion of IL-1β. Overall, these events trigger proinflammatory intracellular signaling cascades and transcription factors, for example, NF-κB, ROS, MMPs, and the release of proinflammatory cytokines, especially IL-1β, −6, −17, −18, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, to initiate a local sterile immune response, which is associated with BBB dysfunction after stroke22.

The first cells to respond are microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells. Activated microglia migrate to the injured area and release proinflammatory cytokines, NO, ROS, prostaglandins, and chemokines, resulting in the additional chemoattraction of circulating leukocytes. Treatment with minocycline to block microglial activation markedly reduces infarct volume and BBB disruption, and improves neurological function23, suggesting that inhibition of microglial activation during the acute phase of stroke is neuroprotective. However, emerging data indicate that microglia actively participates in neurorepair after stroke by releasing growth factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines such as TGF-β124.

Like other paradigms of sterile tissue injury, the innate immune cells comprise the predominant cellular composition of the brain infiltrates in the early acute post-stroke phase followed by lymphocytes. The dynamics of leukocyte invasion into the ischemic brain differ substantially among different cell types25. After stroke, first microglia and then invading macrophages appear within minutes to hours after ischemia, followed by invading neutrophils peaking at three days post infarct25. Their presence persists until day seven and declines afterwards25. Atypical innate-like T cells such as γδ T cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells also arrive early25, while conventional CD4 T cells arrive in a time window similar to neutrophils25. T cells migrate preferentially to the lesion borders and can be detected throughout at least 30 days post-infarct in the brain parenchyma. Treg cells arrive several days after brain ischemia but are still present more than 30 days post lesion25.

T cells play a significant role in secondary neuroinflammation and stroke outcome. Lymphocyte deficient transgenic mice have smaller infarcts after transient or permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) than immunocompetent control animals25–31. Antibody-mediated depletion of single T cell subsets, namely CD8+, CD4+ and γδ T cells or their secreted cytokines, has also been shown to reduce secondary lesion progression27,28,32. T cell-directed therapies in the acute phase after stroke are antigen-independent30. Therefore, it is likely that innate-like lymphocytes or antigen-independent mechanisms of T cell activation are most important in acute ischemic tissue damage.

One of these innate-like T lymphocytes that have been implicated in tissue damage after stroke are the γδ T cells27. They arrive early (within 6 h) and are marked by the expression of Vγ6 segment of the γδ T cells receptor and the chemokine receptor CCR633. Their signature cytokine in stroke is IL-17 which has been shown to harm the peri-lesional tissue. Correspondingly, γδ T cell-deficient mice have reduced infarct volumes27,28, and neutralizing IL-17-specific antibodies can significantly improve stroke outcome28.

Another critical cytokine is IL-1β. It is upregulated rapidly in experimental stroke and worsens ischemic injury in experimental models34. Its release is usually triggered by TLRs’ engagement and purinergic receptors such as P2X7. The endogenous IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) reduces lesion size in experimental cerebral ischemia models, even in aged and comorbid animals and with delayed administration34. A meta-analysis of preclinical stroke studies demonstrated that IL-1Ra reduced infarct volume by 36% in pooled data from 1283 animals35. A recent human trial could verify a reduction in peripheral IL-6 levels after IL-1Ra treatment36.

The ligand-receptor pair TNF/TNFR1 was suggested as relevant for stroke pathology by genome-wide association studies in the form of a polymorphism in the TNF gene that increases the susceptibility for stroke37. After experimental stroke, TNF is mainly secreted by microglia, astrocytes, and invading macrophages and peaks at 12–24 h but remains elevated for days to weeks25,38. Interestingly, TNF-knockout mice38 and conditional TNF-KO mice with ablation of TNF in myeloid cells, including microglia39, develop larger infarcts and worse behavioral deficits. Therefore, microglial-derived TNF mediated via TNFR1 is thought to be protective in stroke, while mice with a loss of TACE-mediated cleavage of TNF and, therefore, loss of soluble TNF develop smaller infarcts40. Targeting soluble TNF experimentally, for example, with etanercept resulted in some studies in better behavioral outcomes but had no effect on infarct volume41.

Taken together, we can conclude that a lot of experimental data exists showing that acutely after an ischemic stroke, a robust sterile inflammation is triggered. This inflammation is induced by several different cell types and humoral factors. Inhibition of T cells, IL-17, IL-1β, or soluble TNF can experimentally result in better outcomes.

Role of peripheral immune cells and their cytokines in the resolution and recovery of ischemic brain injury

The peripheral immune cell most involved in the resolution of ischemic injury is the T regulatory (Treg) cell. Several reports have shown a protective role of Tregs in post-stroke neuroinflammation (reviewed by Liesz et al.42). IL-10 is the primary mediator of Treg-induced effects. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that inhibits IL1-β, TNF-α, and potentially even IL-17 secretion43. In experimental stroke, IL-10 mRNA and protein and IL-10R mRNA increase, and transgenic mice overexpressing IL-10 show reduced infarct volumes44,45. Administration of IL-10 is protective in experimental stroke and limits post-stroke inflammation43,46. Other sources of IL-10 are infiltrating immune cells such as B cells47 and resident cells, for example, microglia or astrocytes48,49. In addition, Treg might also affect BBB integrity during acute stroke. Besides effects on cytokines, adoptive Treg transfer also inhibits MMP-9 activity and protects the BBB integrity50. Tregs, microglia, and cytokines like IL-10 limit the acute inflammatory response after ischemic brain injury. However, there is convincing data of a prolonged presence of inflammatory cells and cytokines in the brain after stroke, which might be necessary for repair efforts.

In part, the recovery after stroke resembles the processes occurring in the early stages of nervous system development51. T cells and locally proliferating T cells have recently been documented for the chronic phase52. Recovery after stroke can be triggered partly by the release of growth factors and cytokines secreted by both microglia and invading T cells53. One exemplary mechanism for the pro-regenerative effect of T cells might be the production of BDNF54. Also, the production of the Th2-signature cytokine IL-4 and the regulatory T cell-derived cytokine IL-10 has been associated with neuroprotective functions of T cells after brain injury55. Moreover, T cell-derived IFN-γ can modulate social behavior by affecting GABAergic projections56. T cells are also potent modulators of the local inflammatory micromilieu aside from direct neuroprotective or modulatory effects. The reaction to acute brain injury and repair is a multicellular process involving multiple non-neuronal cell populations that can potentially be affected by T cells patrolling the injured brain57.

Similar observations are also valid for different proinflammatory cytokines. For example, the second peak in IL-17 expression occurs around day 28 after stroke58. Recent studies show that IL-17A+ γδ T cells populate the meninges from perinatal stages and control neuronal signaling, behavior59, and memory60. IL-17 is likely also involved in the repair mechanisms after stroke. The fact that IL-17A can have these dual roles can be explained by the dependence of the IL-17A receptor signaling on synergistic stimulation by other cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α61, which are also differentially upregulated in ischemic brain tissue62.

Under physiological conditions, TNF has an important role in modulating glutamatergic synaptic transmission and plasticity63. In addition, the absence of TNF has been reported to impact cognition and behavior64, making general strategy to block TNF in stroke difficult. The different receptors add to the difficulties. TNFR1 plays a role in sustaining chronic inflammation in the experimental allergic encephalomyelitis model, while TNFR2 is important for remyelination65. Intracortically infused soluble TNFR1 for one week after photothrombotic stroke preserved axonal plasticity in the brain by competing for soluble TNF with TNFR1 receptors66.

Taken together, most if not all parts of an inflammatory reaction have at least a dual role or, more likely multiple roles. While certain aspects in the acute stage might be harmful, they are later essential for repair and recovery. These events are context-specific and dependent on the receiving receptors and cells.

Imaging markers of neuroinflammation

Medical imaging modalities like CT, MRI, and PET have accelerated stroke diagnostics. These modalities are available in clinical and preclinical settings, providing ideal conditions for translational research. Over the years, numerous studies have demonstrated how imaging techniques can be applied for in vivo detection of BBB permeability, leukocyte infiltration, microglial activation, and upregulation of cell adhesion molecules. Here, we provide a brief overview of methodologies and recent applications of medical imaging modalities to assess neuroinflammation after stroke, including implications for clinical implementation.

BBB permeability imaging

BBB disruption can be measured from the extravasation of contrast agent or radioactive tracer, which results in image contrast enhancement. Quantification of BBB permeability is feasible with dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) or perfusion imaging protocols on MRI or CT scanners, for which paramagnetic or iodine-based contrast agents, respectively, are intravenously injected67,68. The efflux rate of the contrast agent from plasma into the tissue can be calculated through pharmacokinetic modeling of DCE T1-weighted MRI signal intensities, from which different permeability measures, such as the extraction fraction, blood-to-brain transfer constant, and permeability-surface area product, can be quantified69. These measures can also be calculated from perfusion imaging with dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced (DSC) T2(*)-weighted MRI or dynamic CT70, which enables fast acquisition at the expense of spatial resolution.

Most BBB permeability imaging studies use clinically available contrast agents like gadolinium chelates and iodinated contrast media. Alternative contrast agents with varying dimensions and pharmacodynamic properties allow assessment of different degrees of BBB opening and dynamics of BBB breakdown, but this has been limited to preclinical studies in animals67. Recent developments with arterial spin labeling techniques, typically used for perfusion MRI, have shown promise for the non-invasive measurement of BBB permeability71. This approach utilizes water as a tracer rather than an injected exogenous contrast agent.

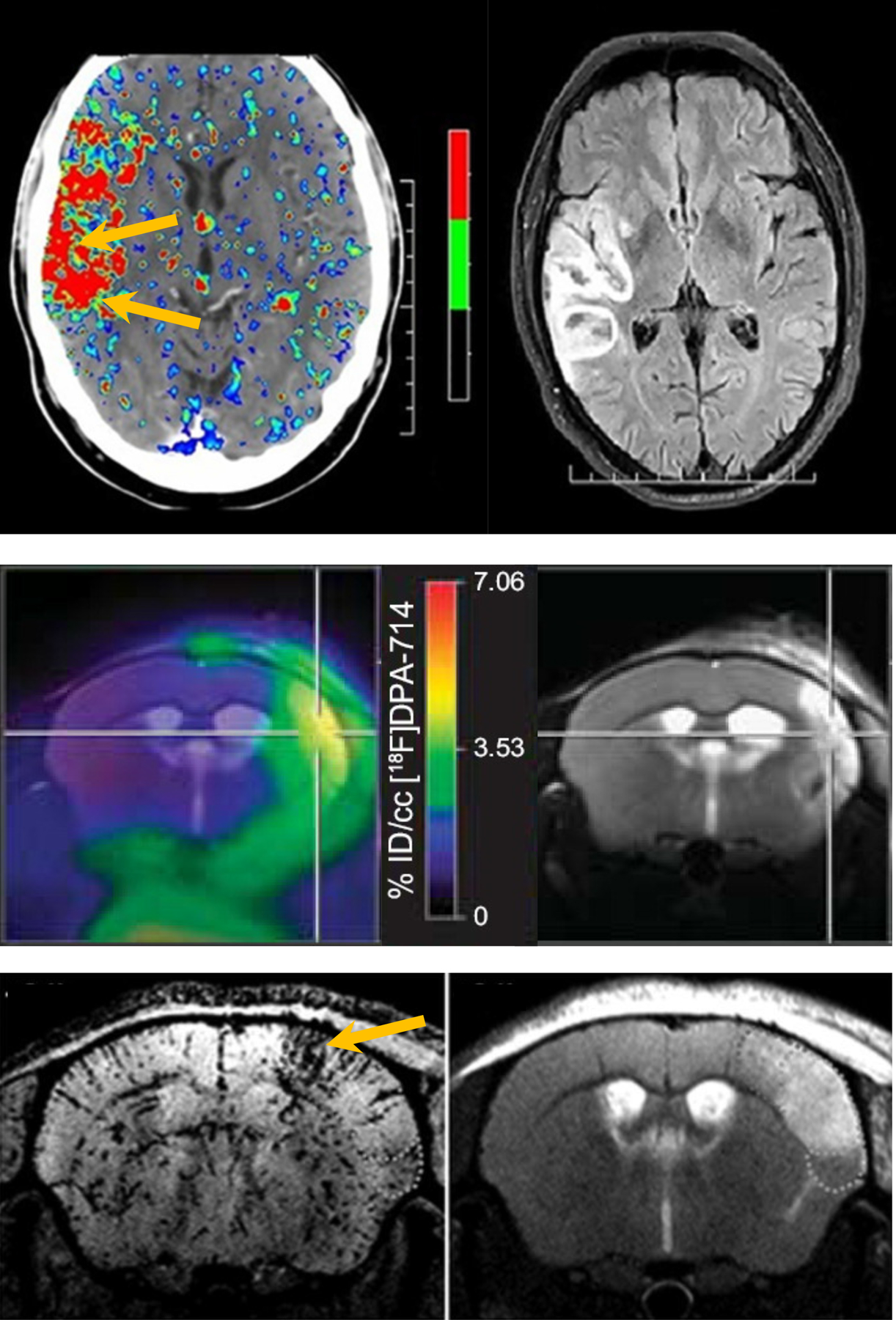

Increased BBB opening is associated with a reduced likelihood of a favorable neurological outcome at 90 days in stroke patients72–74. Various MRI and CT studies have shown that BBB permeability imaging can aid in predicting hemorrhagic transformation after acute ischemic stroke (see Bivard et al. for a recent multicenter study75 and Arba et al. for a recent systematic review and meta-analysis76) (Figure 2, top panel). The association between BBB permeability and hemorrhagic transformation is particularly apparent in hypoperfused areas after thrombolytic treatment77,78. A prospective study has recently demonstrated a significant correlation between pre-treatment BBB permeability and post-treatment hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke patients who underwent perfusion CT before intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular thrombectomy79. On the other hand, the absence of an association between (reversible) BBB permeability before thrombolysis and unfavorable clinical outcome after 90 days has also been reported80.

Figure 2. Imaging neuroinflammation after stroke.

Multimodal brain images of different aspects of neuroinflammation (left images) and corresponding MR images of tissue injury (right images) after clinical or experimental stroke. Top: BBB permeability map, calculated from perfusion CT <4.5 h after ischemic stroke (before intravenous thrombolysis), and follow-up FLAIR MRI displaying hemorrhagic transformation after 24 h (after intravenous thrombolysis) (modified from Bivard et al.75, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Middle: Map of [18F]DPA-714 uptake, a marker of activated microglia, calculated from PET, overlaid on a T2-weighted MR image of the ischemic tissue lesion, at 7 days after transient MCAO in mice (from Zinnhardt et al.118, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND). Bottom: T2*-weighted MRI after injection of anti-VCAM-1 antibody functionalized MPIO, revealing upregulation of VCAM-1 in and around the lesion, shown on a T2-weighted MR image, at 2 days after transient MCAO in mouse (from Gauberti et al.112, reproduced with permission, Copyright Clearance Center, license# 5233371245585). Arrows or crosshair point at elevated BBB permeability preceding hemorrhagic transformation (top), maximal microglial activation in the lesion core (middle), and high VCAM-1 expression in the lesion borderzone (bottom).

Post-procedural hemorrhage and worse functional outcomes have also been associated with late contrast enhancement of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) space on follow-up T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MR images of acute ischemic stroke patients81. This phenomenon was termed “hyperintense acute reperfusion marker” (HARM)82. CSF enhancement in patients may start focally in the acute phase after stroke and become widespread and diffuse throughout the subarachnoid space at later stages83. Delayed CSF enhancement on post-contrast FLAIR images has been recognized as a marker of BBB leakage in different neurological disorders84. Moreover, the retention of the contrast agent in the subarachnoid space may also inform on (deficiencies in) CSF dynamics and (‘glymphatic’) clearance mechanisms, as demonstrated with MRI in rodents after intrathecal or intracisternal infusion of a gadolinium chelate85,86.

Immune cell imaging

It is possible to identify immune cells after labeling with contrast agents or tracer-binding to cell-specific markers. PET-based detection of the 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO), an outer mitochondrial membrane protein, can be considered the gold standard for imaging of activated (residential) microglia or (infiltrated) macrophages (although TSPO may also be expressed by endothelial cells and astrocytes)87. Over the years, different TSPO radiotracers have been synthesized and tested, also for other nuclear imaging methods, like SPECT, with varying levels of sensitivity and specificity for microglia/macrophage detection87. This is partly due to human TSPO polymorphisms causing differential affinity for TSPO ligands, although this does not appear to be an issue in preclinical animal studies87,88.

PET studies in animal models and patients have shown that TSPO expression is low in the first days after stroke, increases in the following weeks (Figure 2, middle panel), and normalizes again after several months88,89. Nevertheless, activation of microglia, co-localized with secondary tissue degeneration, has been detected in non-infarcted areas of chronic patients beyond 6–12 months after stroke90,91. Relatively little is known about the role of microglia activation in the development of post-stroke injury. Alternative PET tracers have been used to learn more about the profile and impact of microglial activation. A possible neuroprotective effect was suggested in a study in which early detection of post-stroke microglial activation, i.e., 24 h after experimental stroke in rats, was demonstrated with PET of the endocannabinoid receptor type 2 (CB2)92. Another study reported detection of gliogenesis, which may be part of restorative processes after stroke, with a PET marker for cell proliferation at day 7 after transient MCAO in rats93. Uptake of the PET tracer [18F]-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (a marker for glucose consumption) in infarcted brain tissue has also been associated with activated microglia or macrophages94. However, this may be obscured by other metabolically active cells in or around the lesion. Additional markers showing promise for PET-based assessment of post-stroke inflammatory responses include α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors95 and adenosine A1 receptors96.

Activated tissue-resident microglia and blood-borne macrophages may also be detected with MRI, enabling imaging at higher resolutions. The most frequently applied strategy for MRI of immune cells involves intravenous injection of ultrasmall particles of iron oxide (USPIOs), which may be internalized by circulating monocytes or phagocytosed by macrophages or microglia after extravasation97,98. Superparamagnetic iron oxide particles are available in different sizes and configurations and induce hypointense or hyperintense signals on T2(*)- or T1-weighted MR images, respectively. However, image contrast enhancement in (pathologic) brain areas after systemic injection of iron oxide particles may not always have a cellular origin, as these particles can get trapped intravascularly or accumulate interstitially without cellular uptake, possibly leading to false-positive assessments99. Moreover, some types of iron oxide particles were shown not to accumulate in post-stroke mouse brains after intravenous injection100. As an alternative strategy, cells can be labeled in vitro and subsequently injected to spatiotemporally track their distribution more specifically, as demonstrated for monocytes101 and T lymphocytes102 in rodents with an experimental stroke lesion. Nanoparticles specifically designed for phagocytic internalization may also improve cell-specific uptake. This was recently shown for a nanoprobe consisting of a gadolinium fluoride core coated with polyethylene glycol and functionalized with a fluorophore103. The multimodal properties, i.e., being paramagnetic and fluorescent, enabled combined in vivo MRI and intravital (two-photon) microscopy, which confirmed uptake by phagocytic immune cells in a mouse stroke model.

In addition to multimodal probes, the development of multifunctional (theranostic) probes may allow combined image-guided diagnosis and treatment. For example, platelet-mimetic nanoparticles, coloaded with iron oxide and an anti-inflammatory agent, are internalized by activated neutrophils in a mouse stroke model, where they can exert therapeutic effects and be detected with MRI104.

Only a few studies have evaluated the potential of immune cell imaging with MRI in humans. Pilot studies in stroke patients reported heterogeneous patterns of contrast enhancement after injection of USPIOs105–108, which could be due to different forms of accumulation (intra- and extracellular) and variation in timings of contrast agent injection and post-contrast MRI acquisition. At present, the clinical potential of MRI-based detection of immune cells with superparamagnetic iron oxide particles as contrast agents remains unclear and requires further investigations. Alternatively, labeling autologous leukocytes with radioisotopes enables detection with nuclear imaging techniques, like SPECT and PET, but this remains an invasive procedure that is further hampered by the release of radiolabel from cells after injection109.

Imaging molecular markers of inflammation

Molecular markers of neuroinflammation can be detected using contrast agents functionalized with ligands (e.g., peptides, proteins, or antibodies) that enable specific targeting and binding. This approach has been successfully applied to identify endothelial activation after experimental stroke with MRI89,97,110. Different contrast agents have been used, but micron-sized particles of iron oxide (MPIOs) have become the most popular for molecular imaging purposes110,111. Because of their size, these iron oxide particles generate large contrast-enhancing effects on MR images. They usually do not extravasate and remain inside the vasculature, allowing binding to molecular entities expressed on the luminal side of the cerebral endothelium. The relatively short plasma half-life (order of minutes) of MPIOs (as compared to many USPIO types (order of hours)) limits contrast effects arising from the circulating free agent.

Functionalization of MPIOs by conjugation with specific monoclonal antibodies has enabled in vivo MRI of the upregulation of P-selectin, E-selectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 in rodent stroke models89,97,110. These cell adhesion molecules have been detected in and outside the lesion territory. For example, Gauberti et al. observed strong contrast-enhancing effects around the ischemic lesion on T2(*)-weighted MR images after intravenous injection of anti-VCAM-1 antibody functionalized MPIO at 24 h after permanent MCAO in mice112 (Figure 2, bottom panel). This inflammatory response preceded secondary tissue injury, and therefore the authors coined the term “inflammatory penumbra”. Strong expression of VCAM-1 in a transient MCAO model in rats has also been revealed with MRI in the first hours after recanalization, which could affect reperfusion dynamics and contribute to expansion of the cerebral infarct113.

At subacute to chronic stages after stroke, cerebrovascular inflammation can be detected with anti-ICAM-1 antibody functionalized MPIO114. Colocalization with ICAM-1-positive leukocytes inside the vasculature, days to weeks after transient MCAO in mice, suggested that targeting MR contrast agents to cell adhesion molecules may also be employed to identify immune cells. This has indeed been demonstrated for microglia or macrophages using Iba-1 antibody-conjugated superparamagnetic nanoparticles, measured in rats up to four weeks after transient MCAO115. Conversely, iron oxide particles may be coated with a natural leukocyte membrane to target activated endothelium, demonstrated using neutrophil-mimetic magnetic nanoprobes in post-stroke mice 116.

Another approach for in vivo imaging of neuroinflammation involves using responsive contrast agents. In a study by Breckwoldt et al., mice were injected with a gadolinium-based paramagnetic contrast agent specifically activated by MPO117. MPO is secreted by activated neutrophils and microglia/macrophages, which peaks in the first days after experimental stroke in rodents. Correspondingly, these authors found clear signal enhancement on T1-weighted MRI, caused by the enzyme-activatable contrast agent, reflecting MPO activity that peaked on day 3 after transient MCAO.

Activation of MMPs, another family of enzymes involved in the neuroinflammatory cascade after stroke, can also be identified with medical imaging modalities. Zinnhardt et al. conducted an original dual-tracer PET study by injecting a radiofluorinated MMP inhibitor and a radiofluorinated TSPO ligand at different time-points after transient MCAO in mice118. Their study revealed differential time courses for MMP (maximal expression after seven days) and microglial activation (maximal expression after fourteen days). The presence of MMPs has also been visualized with 19F MR spectroscopic imaging, following injection of a fluorinated molecular ligand with a high affinity for MMPs119. The signal from this ligand, injected around 24 h after transient MCAO in mice, was significantly elevated inside the lesion area, which was further increased after tPA treatment, correlating with total MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity.

Future implications for clinical and preclinical imaging of neuroinflammation

Although many preclinical studies have demonstrated the ability of medical imaging modalities to assess neuroinflammation, most methods are not routinely utilized for stroke diagnosis in clinical practice. Some procedures, like BBB permeability imaging, have shown considerable promise in patient studies and could be easily implemented. BBB permeability imaging could aid in the identification of patients who can be safely treated with intravenous thrombolysis or endovascular thrombectomy, even beyond the currently recommended time windows for these treatments. However, standardized protocols for image acquisition and data analysis would need to be developed.

Imaging cellular or molecular markers of neuroinflammation may provide complementary diagnostic information after stroke. Yet, several methods await further preclinical evaluation of sensitivity, specificity, and safety. Developing biocompatible and biodegradable contrast agents with good labeling efficiency for human cells or strong binding affinity to human-specific epitopes will be critical for effective clinical implementation. Translational studies should continue to explore the potential of imaging methods to elucidate the role of different inflammatory processes, identify treatment targets and monitor immunomodulating interventions after stroke. Multimodal and multifunctional (theranostic) (nano)probes that can be detected with different imaging modalities and deliver therapeutic agents could be particularly promising for image-guided diagnosis and treatment.

Translation to Humans and Concluding Remarks

While the data from animal studies support a prominent role of inflammatory cells in the pathogenesis of stroke, human data, let alone positive human studies, are scarce. Some histopathological data documents inflammatory cells’ presence in acute and chronic stages after ischemic stroke120,121. However, the overall involvement of T cells seems to be less in human lesions and more prone to MHC class I-restricted CD8+ T-cells compared to the broader spectrum of lymphocytes in rodents121. Microglia and macrophages seem to follow similar patterns in human and rodent stroke, but in aged human stroke lesions, these cells often possess a pre-activated phenotype not seen in young rodents.

So far, our attempts to translate the experimental findings to a clinical application have failed to a large extent. Early studies blocking adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, MAC-1) or the recombinant neutrophil inhibitory factor have been ineffective in clinical trials122. For the ICAM-1 study, the negative outcome was attributed to deleterious immunoactivation resulting from the administration of a mouse antibody to humans. Other factors that likely contributed are the difference in human and rodent immune systems and different age structures in humans and rodents; blocking one inflammatory signal might not be enough and a failure to select the right patient cohort. This selection problem is well documented by the only preclinical randomized controlled trial (pRCT) followed by a human trial. In their pRCT, Llovera and colleagues investigated the effects of CD49d-specific antibodies123. A significant reduction in leukocyte invasion and infarct volume was only documented for permanent MCAO but not for temporary MCAO. Subsequent human trials (ACTION 1 and 2) using CD49d-specific antibodies failed to find any effect on stroke progression124,125. However, the variance in stroke volume with 1–212 ml was comparable to the non-significant tMCAO (0.001–0.095 ml) but not to the significant pMCAO results (0.003–0.016 ml)123. A much better selected patient cohort might have yielded a different result. However, there is another explanation for this discrepancy. A follow-up study showed that a single application of CD49d-specific antibodies only temporarily blocks T cell invasion and T cells accumulate in the brain afterwards52, making it difficult to compare the results of the acute rodent studies to the three-month follow-up time point in humans.

The use of large gyrencephalic animal models, including sheep, dogs, swine, and nonhuman primates, has been recommended by the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable to complement the preclinical testing in rodents and enhance the clinical translation of promising cerebroprotective strategies. Large animal stroke models could aid in the selection of the most viable therapies to test in clinical trials126. A recent study in swine subjected to stroke via an endovascular approach showed that while gadolinium enhancement on T1-weighted MR images was marginal at 24h, likely the result of restricted access of the contrast agent due to limited perfusion of the ischemic territory, immunoglobulin extravasation into the ischemic territory was elevated both (sub)acutely (24h) and chronically (up to 3 months)127, which is similar to findings from clinical studies showing persisting BBB dysfunction in ischemic stroke128,129.

Despite the mostly neutral or negative outcomes of clinical trials, there are some positive preliminary findings in ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke for anti-inflammatory treatments, such as with lymphocyte-trapping agent fingolimod130–132, approved to treat relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis. While the data presented is compelling, these were non-blinded, single-center trials that need to be repeated in larger cohorts. Also, intravenous IL-1Ra in patients with acute stroke significantly reduces plasma inflammatory markers133. In a recently published study, IL-1Ra significantly reduced IL-6 and C-reactive protein plasma levels. IL-1Ra was not associated with a favorable outcome, but the study was not powered to provide significant outcome data.

Despite reports of improved neurological outcomes in patients with stroke or traumatic brain injury treated with perispinal etanercept134,135, none of the currently used anti-TNF therapeutics have so far been approved as a neuroprotective strategy in combination with tissue plasminogen activator treatment.

According to the ClinicalTrials.gov registry of clinical intervention trials, more than 40 are exploring anti-inflammatory strategies with pending outcomes in ischemic stroke. They include a broad spectrum of potential therapies, including cell therapies, modulating lymphocyte migration, or repurposing drugs approved for multiple sclerosis.

Thus far, the lack of positive clinical data using anti-inflammatory therapies suggests that our understanding of the role of neuroinflammation in stroke is insufficient. It is essential to recognize and mechanistically determine the multiphasic nature of inflammation at different stages of the ischemic injury to better develop and implement anti-inflammatory strategies as stroke treatments. Many factors could explain the failure to translate animal studies into the clinic136. Before conducting clinical trials, potential anti-inflammatory therapies should be evaluated in clinically relevant experimental models that incorporate aging, comorbidities, and gender to better mimic the human stroke population. Moreover, to better assess responses to treatment, direct imaging of drug delivery could be valuable to confirm arrival of the drug in the ischemic territory.

Supplementary Material

Sources of Funding

Dr. Candelario-Jalil receives support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), grants R01NS103094 and R01NS109816.

Dr. Dijkhuizen is a member of the CONTRAST consortium, which acknowledges the support from the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative, an initiative of the Dutch Heart Foundation (CVON2015–01: CONTRAST) and from the Brain Foundation Netherlands (HA2015.01.06).

Dr. Magnus was supported by grants from the DFG (FOR 2879 A1 MA 4375/5–1, A3 MA 4375/6–1, A13 of the SFB 1328) and the Schilling Stiftung.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- CBF

Cerebral blood flow

- CNS

Central nervous system

- ECM

Extracellular Matrix

- ICAM-1

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IL

Interleukin

- JAM

Junctional adhesion molecule

- MCAO

Middle cerebral artery occlusion

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NVU

Neurovascular unit

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor α

- TJP

tight junction protein

- Treg

T regulatory cell

- VCAM-1

Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- ZO

zona occludens

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts.

Contributor Information

Eduardo Candelario-Jalil, Department of Neuroscience, McKnight Brain Institute, University of Florida, USA.

Rick M. Dijkhuizen, Biomedical MR Imaging and Spectroscopy Group, Center for Image Sciences, University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Tim Magnus, Department of Neurology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany.

References

- 1.Hawkins BT, Davis TP. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacological reviews 2005;57:173–185. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaeffer S, Iadecola C. Revisiting the neurovascular unit. Nature neuroscience 2021;24:1198–1209. doi: 10.1038/s41593-021-00904-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iadecola C The Neurovascular Unit Coming of Age: A Journey through Neurovascular Coupling in Health and Disease. Neuron 2017;96:17–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heo JH, Han SW, Lee SK. Free radicals as triggers of brain edema formation after stroke. Free Radic Biol Med 2005;39:51–70. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ishibashi N, Prokopenko O, Weisbrot-Lefkowitz M, Reuhl KR, Mirochnitchenko O. Glutathione peroxidase inhibits cell death and glial activation following experimental stroke. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2002;109:34–44. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00459-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong CH, Bozinovski S, Hertzog PJ, Hickey MJ, Crack PJ. Absence of glutathione peroxidase-1 exacerbates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by reducing post-ischemic microvascular perfusion. J Neurochem 2008;107:241–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05605.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahles T, Luedike P, Endres M, Galla HJ, Steinmetz H, Busse R, Neumann-Haefelin T, Brandes RP. NADPH oxidase plays a central role in blood-brain barrier damage in experimental stroke. Stroke 2007;38:3000–3006. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Can A, Dalkara T. Reperfusion-induced oxidative/nitrative injury to neurovascular unit after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2004;35:1449–1453. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000126044.83777.f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Z, Huang PL, Panahian N, Dalkara T, Fishman MC, Moskowitz MA. Effects of cerebral ischemia in mice deficient in neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Science 1994;265:1883–1885. doi: 10.1126/science.7522345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Z, Huang PL, Ma J, Meng W, Ayata C, Fishman MC, Moskowitz MA. Enlarged infarcts in endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice are attenuated by nitro-L-arginine. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1996;16:981–987. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang C, Hawkins KE, Dore S, Candelario-Jalil E. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of blood-brain barrier damage in ischemic stroke. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2019;316:C135–C153. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00136.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montaner J, Molina CA, Monasterio J, Abilleira S, Arenillas JF, Ribó M, Quintana M, Alvarez-Sabín J. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 pretreatment level predicts intracranial hemorrhagic complications after thrombolysis in human stroke. Circulation 2003;107:598–603. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046451.38849.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucivero V, Prontera M, Mezzapesa DM, Petruzzellis M, Sancilio M, Tinelli A, Di Noia D, Ruggieri M, Federico F. Different roles of matrix metalloproteinases-2 and −9 after human ischaemic stroke. Neurol Sci 2007;28:165–170. doi: 10.1007/s10072-007-0814-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosell A, Cuadrado E, Ortega-Aznar A, Hernández-Guillamon M, Lo EH, Montaner J. MMP-9-positive neutrophil infiltration is associated to blood-brain barrier breakdown and basal lamina type IV collagen degradation during hemorrhagic transformation after human ischemic stroke. Stroke 2008;39:1121–1126. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.107.500868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gidday JM, Gasche YG, Copin JC, Shah AR, Perez RS, Shapiro SD, Chan PH, Park TS. Leukocyte-derived matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates blood-brain barrier breakdown and is proinflammatory after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2005;289:H558–568. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01275.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuadrado E, Ortega L, Hernandez-Guillamon M, Penalba A, Fernandez-Cadenas I, Rosell A, Montaner J. Tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) promotes neutrophil degranulation and MMP-9 release. Journal of leukocyte biology 2008;84:207–214. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asahi M, Wang X, Mori T, Sumii T, Jung JC, Moskowitz MA, Fini ME, Lo EH. Effects of matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene knock-out on the proteolysis of blood-brain barrier and white matter components after cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci 2001;21:7724–7732. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.21-19-07724.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki Y, Nagai N, Umemura K, Collen D, Lijnen HR. Stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) is critical for intracranial bleeding after t-PA treatment of stroke in mice. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5:1732–1739. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02628.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chelluboina B, Klopfenstein JD, Pinson DM, Wang DZ, Vemuganti R, Veeravalli KK. Matrix Metalloproteinase-12 Induces Blood-Brain Barrier Damage After Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Stroke 2015;46:3523–3531. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akol I, Kalogeraki E, Pielecka-Fortuna J, Fricke M, Löwel S. MMP2 and MMP9 Activity Is Crucial for Adult Visual Cortex Plasticity in Healthy and Stroke-Affected Mice. J Neurosci 2022;42:16–32. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0902-21.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao BQ, Wang S, Kim HY, Storrie H, Rosen BR, Mooney DJ, Wang X, Lo EH. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in delayed cortical responses after stroke. Nat Med 2006;12:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nm1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulke E, Gelderblom M, Magnus T. Danger signals in stroke and their role on microglia activation after ischemia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2018;11:1756286418774254. doi: 10.1177/1756286418774254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yenari MA, Xu L, Tang XN, Qiao Y, Giffard RG. Microglia potentiate damage to blood-brain barrier constituents: improvement by minocycline in vivo and in vitro. Stroke 2006;37:1087–1093. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206281.77178.ac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Polazzi E, Monti B. Microglia and neuroprotection: from in vitro studies to therapeutic applications. Prog Neurobiol 2010;92:293–315. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelderblom M, Leypoldt F, Steinbach K, Behrens D, Choe CU, Siler DA, Arumugam TV, Orthey E, Gerloff C, Tolosa E, et al. Temporal and spatial dynamics of cerebral immune cell accumulation in stroke. Stroke 2009;40:1849–1857. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yilmaz G, Arumugam TV, Stokes KY, Granger DN. Role of T lymphocytes and interferon-gamma in ischemic stroke. Circulation 2006;113:2105–2112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shichita T, Sugiyama Y, Ooboshi H, Sugimori H, Nakagawa R, Takada I, Iwaki T, Okada Y, Iida M, Cua DJ, et al. Pivotal role of cerebral interleukin-17-producing gammadeltaT cells in the delayed phase of ischemic brain injury. Nat Med 2009;15:946–950. doi: 10.1038/nm.1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelderblom M, Weymar A, Bernreuther C, Velden J, Arunachalam P, Steinbach K, Orthey E, Arumugam TV, Leypoldt F, Simova O, et al. Neutralization of the IL-17 axis diminishes neutrophil invasion and protects from ischemic stroke. Blood 2012;120:3793–3802. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-412726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liesz A, Suri-Payer E, Veltkamp C, Doerr H, Sommer C, Rivest S, Giese T, Veltkamp R. Regulatory T cells are key cerebroprotective immunomodulators in acute experimental stroke. Nat Med 2009;15:192–199. doi: 10.1038/nm.1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleinschnitz C, Schwab N, Kraft P, Hagedorn I, Dreykluft A, Schwarz T, Austinat M, Nieswandt B, Wiendl H, Stoll G. Early detrimental T-cell effects in experimental cerebral ischemia are neither related to adaptive immunity nor thrombus formation. Blood 2010;115:3835–3842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleinschnitz C, Kraft P, Dreykluft A, Hagedorn I, Gobel K, Schuhmann MK, Langhauser F, Helluy X, Schwarz T, Bittner S, et al. Regulatory T cells are strong promoters of acute ischemic stroke in mice by inducing dysfunction of the cerebral microvasculature. Blood 2013;121:679–691. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-426734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liesz A, Zhou W, Mracsko E, Karcher S, Bauer H, Schwarting S, Sun L, Bruder D, Stegemann S, Cerwenka A, et al. Inhibition of lymphocyte trafficking shields the brain against deleterious neuroinflammation after stroke. Brain 2011;134:704–720. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arunachalam P, Ludewig P, Melich P, Arumugam TV, Gerloff C, Prinz I, Magnus T, Gelderblom M. CCR6 (CC Chemokine Receptor 6) Is Essential for the Migration of Detrimental Natural Interleukin-17-Producing gammadelta T Cells in Stroke. Stroke 2017;48:1957–1965. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sobowale OA, Parry-Jones AR, Smith CJ, Tyrrell PJ, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Interleukin-1 in Stroke: From Bench to Bedside. Stroke 2016;47:2160–2167. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCann SK, Cramond F, Macleod MR, Sena ES. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist in Animal Models of Stroke: an Update. Translational stroke research 2016;7:395–406. doi: 10.1007/s12975-016-0489-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith CJ, Hulme S, Vail A, Heal C, Parry-Jones AR, Scarth S, Hopkins K, Hoadley M, Allan SM, Rothwell NJ, et al. SCIL-STROKE (Subcutaneous Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist in Ischemic Stroke): A Randomized Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Stroke 2018;49:1210–1216. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.020750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Um JY, An NH, Kim HM. TNF-alpha and TNF-beta gene polymorphisms in cerebral infarction. J Mol Neurosci 2003;21:167–171. doi: 10.1385/JMN:21:2:167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambertsen KL, Clausen BH, Babcock AA, Gregersen R, Fenger C, Nielsen HH, Haugaard LS, Wirenfeldt M, Nielsen M, Dagnaes-Hansen F, et al. Microglia protect neurons against ischemia by synthesis of tumor necrosis factor. J Neurosci 2009;29:1319–1330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5505-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clausen BH, Degn M, Sivasaravanaparan M, Fogtmann T, Andersen MG, Trojanowsky MD, Gao H, Hvidsten S, Baun C, Deierborg T, et al. Conditional ablation of myeloid TNF increases lesion volume after experimental stroke in mice, possibly via altered ERK1/2 signaling. Sci Rep 2016;6:29291. doi: 10.1038/srep29291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madsen PM, Clausen BH, Degn M, Thyssen S, Kristensen LK, Svensson M, Ditzel N, Finsen B, Deierborg T, Brambilla R, et al. Genetic ablation of soluble tumor necrosis factor with preservation of membrane tumor necrosis factor is associated with neuroprotection after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016;36:1553–1569. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15610339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clausen BH, Degn M, Martin NA, Couch Y, Karimi L, Ormhoj M, Mortensen ML, Gredal HB, Gardiner C, Sargent, II, et al. Systemically administered anti-TNF therapy ameliorates functional outcomes after focal cerebral ischemia. J Neuroinflammation 2014;11:203. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0203-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liesz A, Hu X, Kleinschnitz C, Offner H. Functional role of regulatory lymphocytes in stroke: facts and controversies. Stroke 2015;46:1422–1430. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.114.008608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piepke M, Clausen BH, Ludewig P, Vienhues JH, Bedke T, Javidi E, Rissiek B, Jank L, Brockmann L, Sandrock I, et al. Interleukin-10 improves stroke outcome by controlling the detrimental Interleukin-17A response. J Neuroinflammation 2021;18:265. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02316-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez-de Puig I, Miro F, Salas-Perdomo A, Bonfill-Teixidor E, Ferrer-Ferrer M, Marquez-Kisinousky L, Planas AM. IL-10 deficiency exacerbates the brain inflammatory response to permanent ischemia without preventing resolution of the lesion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:1955–1966. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Bilbao F, Arsenijevic D, Moll T, Garcia-Gabay I, Vallet P, Langhans W, Giannakopoulos P. In vivo over-expression of interleukin-10 increases resistance to focal brain ischemia in mice. J Neurochem 2009;110:12–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ooboshi H, Ibayashi S, Shichita T, Kumai Y, Takada J, Ago T, Arakawa S, Sugimori H, Kamouchi M, Kitazono T, et al. Postischemic gene transfer of interleukin-10 protects against both focal and global brain ischemia. Circulation 2005;111:913–919. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155622.68580.DC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bodhankar S, Chen Y, Vandenbark AA, Murphy SJ, Offner H. IL-10-producing B-cells limit CNS inflammation and infarct volume in experimental stroke. Metabolic brain disease 2013;28:375–386. doi: 10.1007/s11011-013-9413-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He ML, Lv ZY, Shi X, Yang T, Zhang Y, Li TY, Chen J. Interleukin-10 release from astrocytes suppresses neuronal apoptosis via the TLR2/NFkappaB pathway in a neonatal rat model of hypoxic-ischemic brain damage. J Neurochem 2017;142:920–933. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nguyen TV, Frye JB, Zbesko JC, Stepanovic K, Hayes M, Urzua A, Serrano G, Beach TG, Doyle KP. Multiplex immunoassay characterization and species comparison of inflammation in acute and non-acute ischemic infarcts in human and mouse brain tissue. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2016;4:100. doi: 10.1186/s40478-016-0371-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li P, Mao L, Liu X, Gan Y, Zheng J, Thomson AW, Gao Y, Chen J, Hu X. Essential role of program death 1-ligand 1 in regulatory T-cell-afforded protection against blood-brain barrier damage after stroke. Stroke 2014;45:857–864. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wahl AS, Omlor W, Rubio JC, Chen JL, Zheng H, Schroter A, Gullo M, Weinmann O, Kobayashi K, Helmchen F, et al. Neuronal repair. Asynchronous therapy restores motor control by rewiring of the rat corticospinal tract after stroke. Science 2014;344:1250–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.1253050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heindl S, Ricci A, Carofiglio O, Zhou Q, Arzberger T, Lenart N, Franzmeier N, Hortobagyi T, Nelson PT, Stowe AM, et al. Chronic T cell proliferation in brains after stroke could interfere with the efficacy of immunotherapies. J Exp Med 2021;218. doi: 10.1084/jem.20202411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauer S, Kerr BJ, Patterson PH. The neuropoietic cytokine family in development, plasticity, disease and injury. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007;8:221–232. doi: 10.1038/nrn2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barouch R, Schwartz M. Autoreactive T cells induce neurotrophin production by immune and neural cells in injured rat optic nerve: implications for protective autoimmunity. FASEB J 2002;16:1304–1306. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0467fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walsh JT, Hendrix S, Boato F, Smirnov I, Zheng J, Lukens JR, Gadani S, Hechler D, Golz G, Rosenberger K, et al. MHCII-independent CD4+ T cells protect injured CNS neurons via IL-4. J Clin Invest 2015;125:699–714. doi: 10.1172/JCI76210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Filiano AJ, Xu Y, Tustison NJ, Marsh RL, Baker W, Smirnov I, Overall CC, Gadani SP, Turner SD, Weng Z, et al. Unexpected role of interferon-gamma in regulating neuronal connectivity and social behaviour. Nature 2016;535:425–429. doi: 10.1038/nature18626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burda JE, Sofroniew MV. Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron 2014;81:229–248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin Y, Zhang JC, Yao CY, Wu Y, Abdelgawad AF, Yao SL, Yuan SY. Critical role of astrocytic interleukin-17 A in post-stroke survival and neuronal differentiation of neural precursor cells in adult mice. Cell death & disease 2016;7:e2273. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alves de Lima K, Rustenhoven J, Da Mesquita S, Wall M, Salvador AF, Smirnov I, Martelossi Cebinelli G, Mamuladze T, Baker W, Papadopoulos Z, et al. Meningeal gammadelta T cells regulate anxiety-like behavior via IL-17a signaling in neurons. Nature immunology 2020;21:1421–1429. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-0776-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ribeiro M, Brigas HC, Temido-Ferreira M, Pousinha PA, Regen T, Santa C, Coelho JE, Marques-Morgado I, Valente CA, Omenetti S, et al. Meningeal gammadelta T cell-derived IL-17 controls synaptic plasticity and short-term memory. Sci Immunol 2019;4. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay5199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, Liu XK, Yamamoto H, Kasayama S, Kirkwood KL, Gaffen SL. Functional cooperation between interleukin-17 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha is mediated by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family members. J Biol Chem 2004;279:2559–2567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308809200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clausen BH, Lambertsen KL, Babcock AA, Holm TH, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Finsen B. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha are expressed by different subsets of microglia and macrophages after ischemic stroke in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2008;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature 2006;440:1054–1059. doi: 10.1038/nature04671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baune BT, Wiede F, Braun A, Golledge J, Arolt V, Koerner H. Cognitive dysfunction in mice deficient for TNF- and its receptors. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2008;147B:1056–1064. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brambilla R, Ashbaugh JJ, Magliozzi R, Dellarole A, Karmally S, Szymkowski DE, Bethea JR. Inhibition of soluble tumour necrosis factor is therapeutic in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and promotes axon preservation and remyelination. Brain 2011;134:2736–2754. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liguz-Lecznar M, Zakrzewska R, Kossut M. Inhibition of Tnf-alpha R1 signaling can rescue functional cortical plasticity impaired in early post-stroke period. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36:2877–2884. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liebner S, Dijkhuizen RM, Reiss Y, Plate KH, Agalliu D, Constantin G. Functional morphology of the blood-brain barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol 2018;135:311–336. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1815-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernardo-Castro S, Sousa JA, Bras A, Cecilia C, Rodrigues B, Almendra L, Machado C, Santo G, Silva F, Ferreira L, et al. Pathophysiology of Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Throughout the Different Stages of Ischemic Stroke and Its Implication on Hemorrhagic Transformation and Recovery. Frontiers in neurology 2020;11:594672. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.594672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sourbron SP, Buckley DL. Classic models for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. NMR Biomed 2013;26:1004–1027. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cuenod CA, Balvay D. Perfusion and vascular permeability: basic concepts and measurement in DCE-CT and DCE-MRI. Diagn Interv Imaging 2013;94:1187–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin Z, Li Y, Su P, Mao D, Wei Z, Pillai JJ, Moghekar A, van Osch M, Ge Y, Lu H. Non-contrast MR imaging of blood-brain barrier permeability to water. Magn Reson Med 2018;80:1507–1520. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ng FC, Churilov L, Yassi N, Kleinig TJ, Thijs V, Wu TY, Shah DG, Dewey HM, Sharma G, Desmond PM, et al. Reduced Severity of Tissue Injury Within the Infarct May Partially Mediate the Benefit of Reperfusion in Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2022:Strokeaha121036670. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.121.036670 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Nadareishvili Z, Simpkins AN, Hitomi E, Reyes D, Leigh R. Post-Stroke Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and Poor Functional Outcome in Patients Receiving Thrombolytic Therapy. Cerebrovasc Dis 2019;47:135–142. doi: 10.1159/000499666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rost NS, Cougo P, Lorenzano S, Li H, Cloonan L, Bouts MJ, Lauer A, Etherton MR, Karadeli HH, Musolino PL, et al. Diffuse microvascular dysfunction and loss of white matter integrity predict poor outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018;38:75–86. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bivard A, Kleinig T, Churilov L, Levi C, Lin L, Cheng X, Chen C, Aviv R, Choi PMC, Spratt NJ, et al. Permeability Measures Predict Hemorrhagic Transformation after Ischemic Stroke. Ann Neurol 2020;88:466–476. doi: 10.1002/ana.25785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arba F, Rinaldi C, Caimano D, Vit F, Busto G, Fainardi E. Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and Hemorrhagic Transformation in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in neurology 2020;11:594613. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.594613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Potreck A, Mutke MA, Weyland CS, Pfaff JAR, Ringleb PA, Mundiyanapurath S, Mohlenbruch MA, Heiland S, Pham M, Bendszus M, et al. Combined Perfusion and Permeability Imaging Reveals Different Pathophysiologic Tissue Responses After Successful Thrombectomy. Translational stroke research 2021;12:799–807. doi: 10.1007/s12975-020-00885-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Adebayo OD, Culpan G. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography perfusion in the prediction of haemorrhagic transformation and patient outcome in acute ischaemic stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Stroke J 2020;5:4–16. doi: 10.1177/2396987319883461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arba F, Piccardi B, Palumbo V, Biagini S, Galmozzi F, Iovene V, Giannini A, Testa GD, Sodero A, Nesi M, et al. Blood-brain barrier leakage and hemorrhagic transformation: The Reperfusion Injury in Ischemic StroKe (RISK) study. Eur J Neurol 2021;28:3147–3154. doi: 10.1111/ene.14985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu C, Zhang S, Yan S, Zhang R, Shi F, Ding X, Parsons M, Lou M. Reperfusion facilitates reversible disruption of the human blood-brain barrier following acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Radiol 2018;28:642–649. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Latour LL, Kang DW, Ezzeddine MA, Chalela JA, Warach S. Early blood-brain barrier disruption in human focal brain ischemia. Ann Neurol 2004;56:468–477. doi: 10.1002/ana.20199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Warach S, Latour LL. Evidence of reperfusion injury, exacerbated by thrombolytic therapy, in human focal brain ischemia using a novel imaging marker of early blood-brain barrier disruption. Stroke 2004;35:2659–2661. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000144051.32131.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee KM, Kim JH, Kim E, Choi BS, Bae YJ, Bae HJ. Early Stage of Hyperintense Acute Reperfusion Marker on Contrast-Enhanced FLAIR Images in Patients With Acute Stroke. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016;206:1272–1275. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Freeze WM, van der Thiel M, de Bresser J, Klijn CJM, van Etten ES, Jansen JFA, van der Weerd L, Jacobs HIL, Backes WH, van Veluw SJ. CSF enhancement on post-contrast fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images; a systematic review. Neuroimage Clin 2020;28:102456. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gaberel T, Gakuba C, Goulay R, Martinez De Lizarrondo S, Hanouz JL, Emery E, Touze E, Vivien D, Gauberti M. Impaired glymphatic perfusion after strokes revealed by contrast-enhanced MRI: a new target for fibrinolysis? Stroke 2014;45:3092–3096. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, Feng T, Logan J, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest 2013;123:1299–1309. doi: 10.1172/JCI67677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cumming P, Burgher B, Patkar O, Breakspear M, Vasdev N, Thomas P, Liu GJ, Banati R. Sifting through the surfeit of neuroinflammation tracers. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018;38:204–224. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17748786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Van Camp N, Lavisse S, Roost P, Gubinelli F, Hillmer A, Boutin H. TSPO imaging in animal models of brain diseases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2021;49:77–109. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05379-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zinnhardt B, Wiesmann M, Honold L, Barca C, Schafers M, Kiliaan AJ, Jacobs AH. In vivo imaging biomarkers of neuroinflammation in the development and assessment of stroke therapies - towards clinical translation. Theranostics 2018;8:2603–2620. doi: 10.7150/thno.24128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schaechter JD, Hightower BG, Kim M, Loggia ML. A pilot [(11)C]PBR28 PET/MRI study of neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in chronic stroke patients. Brain Behav Immun Health 2021;17:100336. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thiel A, Radlinska BA, Paquette C, Sidel M, Soucy JP, Schirrmacher R, Minuk J. The temporal dynamics of poststroke neuroinflammation: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging-guided PET study with 11C-PK11195 in acute subcortical stroke. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2010;51:1404–1412. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.076612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hosoya T, Fukumoto D, Kakiuchi T, Nishiyama S, Yamamoto S, Ohba H, Tsukada H, Ueki T, Sato K, Ouchi Y. In vivo TSPO and cannabinoid receptor type 2 availability early in post-stroke neuroinflammation in rats: a positron emission tomography study. J Neuroinflammation 2017;14:69. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0851-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ardaya M, Joya A, Padro D, Plaza-Garcia S, Gomez-Vallejo V, Sanchez M, Garbizu M, Cossio U, Matute C, Cavaliere F, et al. In vivo PET Imaging of Gliogenesis After Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Frontiers in neuroscience 2020;14:793. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Backes H, Walberer M, Ladwig A, Rueger MA, Neumaier B, Endepols H, Hoehn M, Fink GR, Schroeter M, Graf R. Glucose consumption of inflammatory cells masks metabolic deficits in the brain. Neuroimage 2016;128:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Colas L, Domercq M, Ramos-Cabrer P, Palma A, Gomez-Vallejo V, Padro D, Plaza-Garcia S, Pulagam KR, Higuchi M, Matute C, et al. In vivo imaging of Alpha7 nicotinic receptors as a novel method to monitor neuroinflammation after cerebral ischemia. Glia 2018;66:1611–1624. doi: 10.1002/glia.23326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Joya A, Ardaya M, Montilla A, Garbizu M, Plaza-Garcia S, Gomez-Vallejo V, Padro D, Gutierrez JJ, Rios X, Ramos-Cabrer P, et al. In vivo multimodal imaging of adenosine A1 receptors in neuroinflammation after experimental stroke. Theranostics 2021;11:410–425. doi: 10.7150/thno.51046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Deddens LH, Van Tilborg GA, Mulder WJ, De Vries HE, Dijkhuizen RM. Imaging neuroinflammation after stroke: current status of cellular and molecular MRI strategies. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;33:392–402. doi: 10.1159/000336116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stoll G, Bendszus M. New approaches to neuroimaging of central nervous system inflammation. Curr Opin Neurol 2010;23:282–286. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328337f4b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Desestret V, Brisset JC, Moucharrafie S, Devillard E, Nataf S, Honnorat J, Nighoghossian N, Berthezene Y, Wiart M. Early-stage investigations of ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide-induced signal change after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Stroke 2009;40:1834–1841. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Harms C, Datwyler AL, Wiekhorst F, Trahms L, Lindquist R, Schellenberger E, Mueller S, Schutz G, Roohi F, Ide A, et al. Certain types of iron oxide nanoparticles are not suited to passively target inflammatory cells that infiltrate the brain in response to stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013;33:e1–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Oude Engberink RD, Blezer EL, Hoff EI, van der Pol SM, van der Toorn A, Dijkhuizen RM, de Vries HE. MRI of monocyte infiltration in an animal model of neuroinflammation using SPIO-labeled monocytes or free USPIO. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008;28:841–851. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jin WN, Yang X, Li Z, Li M, Shi SX, Wood K, Liu Q, Fu Y, Han W, Xu Y, et al. Non-invasive tracking of CD4+ T cells with a paramagnetic and fluorescent nanoparticle in brain ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016;36:1464–1476. doi: 10.1177/0271678X15611137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hubert V, Hristovska I, Karpati S, Benkeder S, Dey A, Dumot C, Amaz C, Chounlamountri N, Watrin C, Comte JC, et al. Multimodal Imaging with NanoGd Reveals Spatiotemporal Features of Neuroinflammation after Experimental Stroke. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2021;8:e2101433. doi: 10.1002/advs.202101433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tang C, Wang C, Zhang Y, Xue L, Li Y, Ju C, Zhang C. Recognition, Intervention, and Monitoring of Neutrophils in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Nano letters 2019;19:4470–4477. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b01282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Saleh A, Schroeter M, Ringelstein A, Hartung HP, Siebler M, Modder U, Jander S. Iron oxide particle-enhanced MRI suggests variability of brain inflammation at early stages after ischemic stroke. Stroke 2007;38:2733–2737. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.481788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nighoghossian N, Wiart M, Cakmak S, Berthezene Y, Derex L, Cho TH, Nemoz C, Chapuis F, Tisserand GL, Pialat JB, et al. Inflammatory response after ischemic stroke: a USPIO-enhanced MRI study in patients. Stroke 2007;38:303–307. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000254548.30258.f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cho TH, Nighoghossian N, Wiart M, Desestret V, Cakmak S, Berthezene Y, Derex L, Louis-Tisserand G, Honnorat J, Froment JC, et al. USPIO-enhanced MRI of neuroinflammation at the sub-acute stage of ischemic stroke: preliminary data. Cerebrovasc Dis 2007;24:544–546. doi: 10.1159/000111222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Saleh A, Schroeter M, Jonkmanns C, Hartung HP, Modder U, Jander S. In vivo MRI of brain inflammation in human ischaemic stroke. Brain 2004;127:1670–1677. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wunder A, Klohs J, Dirnagl U. Non-invasive visualization of CNS inflammation with nuclear and optical imaging. Neuroscience 2009;158:1161–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gauberti M, Fournier AP, Docagne F, Vivien D, Martinez de Lizarrondo S. Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Endothelial Activation in the Central Nervous System. Theranostics 2018;8:1195–1212. doi: 10.7150/thno.22662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sibson NR, Anthony DC, van Kasteren S, Dickens A, Perez-Balderas F, McAteer MA, Choudhury RP, Davis BG. Molecular MRI approaches to the detection of CNS inflammation. Methods Mol Biol 2011;711:379–396. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-992-5_19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gauberti M, Montagne A, Marcos-Contreras OA, Le Behot A, Maubert E, Vivien D. Ultra-sensitive molecular MRI of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 reveals a dynamic inflammatory penumbra after strokes. Stroke 2013;44:1988–1996. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Franx BAA, Van der Toorn A, Van Heijningen C, Vivien D, Bonnard T, Dijkhuizen RM. Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Vascular Inflammation After Recanalization in a Rat Ischemic Stroke Model. Stroke 2021;52:e788–e791. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]