Abstract

The brainstem is among the first regions to accumulate Alzheimer’s disease-related hyperphosphorylated tau pathology during aging. We aimed to examine associations between brainstem volume and neocortical beta-amyloid or tau pathology in 271 middle-aged clinically normal individuals of the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) who underwent MRI and PET imaging. Lower volume of the medulla, pons or midbrain was associated with greater neocortical amyloid burden. No associations were detected between brainstem volumes and tau deposition. Our results support the hypothesis that lower brainstem volumes are associated with initial AD-related processes and may signal preclinical AD pathology.

Keywords: brainstem, amyloid, tau, aging

Introduction

The pathophysiological process of Alzheimer’s disease starts two to three decades prior to the clinical symptoms. Several autopsy studies suggested that neuromodulatory nuclei in the brainstem may be among the first regions in the brain to accumulate tau pathology, starting as early as young adulthood [1–3]. Accrual of tau pathology has been identified in midbrain nuclei, including the substantia nigra and raphe nuclei, and in the pontine nuclei, including the locus coeruleus and pedunculopontine nuclei. Some of these changes may occur early in life; for example the locus coeruleus has been reported to harbor hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates in approximately 50% of 30-year old individuals [4, 5]. Similarly, raphe nucleus neurons accumulate tau deposition in precortical stages [6]. Previous studies reported lower grey matter volume in the rostral midbrain and pons in Alzheimer’s disease patients relative to cognitively normal individuals [7]. Cognitively healthy older individuals who later progressed to Alzheimer’s disease dementia also exhibited lower grey matter volume in the midbrain and in a specific pontine cluster colocalized to the locus coeruleus as compared to those who did not progress [8, 9]. These findings suggest that brainstem volumetric changes may be occurring early, starting in clinically normal individuals, and reflect underlying progression of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. As tau pathology is one of the major contributors to neurodegeneration, we sought to examine the association between brainstem volume and neocortical beta-amyloid or tau pathology in the third generation (Gen 3) cohort of the Framingham Heart Study (FHS), comprising middle-aged clinically normal individuals.

Methods

Participants

Individuals from the FHS Gen 3 who underwent 3T-MRI, 18F Flortaucipir (FTP) and 11C Pittsburgh Compound B– (PiB)-PET were included for the present study (n=271, mean age=54.4 years (SD=8, range=32–73)). Participants in the FHS Gen 3 cohort are grandchildren of the original FHS cohort [10, 11]. The time between the FTP-PET visit, PIB-PET visit and MRI was less than one year (mean=0.5, SD=1.0). All participants underwent a clinical evaluation to exclude medical or neurological disorders that could impact their cognitive abilities. The majority of participants have had APOE genotyping (N=261, 96%). Participants underwent cognitive testing of which a global cognitive composite was derived (termed the PC1). This composite was obtained by extracting the first principal component from a principal component analysis forcing a single score solution including the Trails Making Test part B, the Hooper Visual Organization Test, the Logical Memory test, the Visual Reproductions test, the Paired Associate Learning and the Similarities. Measures that had a skewed distribution were log-transformed, and directionality was reversed such that higher scores reflect better performance. Study protocols were approved by Boston University School of Medicine and the Partners Human Research Committee of Massachusetts General Hospital and all participants provided written informed consent.

Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Anatomical scans of the FHS participants were collected at Boston University using a Philips 3T Achieva (Philips, Best, Netherland; repetition time=6800 ms, echo time = 3.1 ms, flip angle = 9 degrees, and a voxel size = 0.98 × 0.98 × 1.2 mm) All T1-weighted images were processed using FreeSurfer (FS) version 6 using the software package’s default, automated reconstruction protocol as described previously [12]. Briefly, each T1-weighted image was subjected to a volume-based and surface-based automated segmentation process involving intensity normalization, skull stripping, segregating left and right hemispheres, and in addition for the surface-based stream, brainstem and cerebellum were removed, topology defects were corrected, borders between grey/white matter and grey/cerebrospinal fluid were defined. Together, these resulted in a parcellation of cortical and subcortical areas. Using FS’s visualization toolbox, we visually inspected and, if necessary, edited each image. These edits included control point editing for over- or under-estimation of gray/white matter boundaries and manual editing the skull stripping procedures if needed. The brainstem volumes were segmented using a Bayesian segmentation algorithm that relies on a probabilistic atlas of the brainstem and neighboring structures, providing volumetric measures of the pons, medulla and midbrain (the superior cerebellar pedunculus was not included in our analyses) [13]. The segmentation of the brainstem structures was inspected visually, and we detected no issues. As a control region not specific to AD (outside the brainstem and not a site of atrophy or amyloid/tau accumulation in initial AD), we included the striatum volume, calculated as the sum of the caudate and putamen volumes, and fourth ventricle volume, given that this is located in the vicinity of the brainstem. In addition, we also included hippocampal volume representing a control region vulnerable to early AD pathology. Volumes were expressed in percentage relative to the total cranial volume.

Positron Emission Tomography

All PiB-PET and FTP-PET data were acquired at Massachusetts General Hospital as previously reported [14]: PiB-PET was acquired with a 8.5 to 15 mCi (315 – 555 MBq) bolus injection followed immediately by a 60-minute dynamic acquisition in 69 frames (12×15 seconds, 57×60 seconds) and FTP was acquired from 80–100 minutes after a 9.0 to 11.0 mCi (330 – 405 MBq) bolus injection in 4 × 5-minute frames on a Siemens/CTI ECAT EXACT HR+ scanner (n=218) or a GE Discovery DMI 5-Ring TOF PET/CT scanner [15] (n=53). To harmonize data across these cameras, GE Discovery images were smoothed with a 6mm Gaussian smoothing filter. In addition, PET camera (HR+ or GE) was included as covariate in all statistical analyses.

PET data was reconstructed and attenuation-corrected, and each frame was evaluated to verify adequate count statistics and absence of head motion. PiB PET data were expressed as the distribution volume ratio (DVR) with cerebellar grey as reference tissue by using the Logan graphical method applied to data from 40 to 60 minutes after injection [16]. The FTP PET data were expressed in Standardized Uptake Values (SUVr) with cerebellar cortex as reference tissue. To evaluate the anatomy of cortical PiB or FTP binding, each individual PET data set was rigidly coregistered to the subject’s MPRAGE data. The FreeSurfer regions-of-interest (ROIs) were transformed into the PET native space. PET data were partial volume corrected (PVC) using the Geometrical Transfer Matrix method as implemented in FreeSurfer [17]. Neocortical PiB retention was also assessed in a large cortical ROI aggregate that included frontal, lateral temporal and retrosplenial cortices (FLR) [18]. For the FTP data we a priori chose several regions known to harbor neurofibrillary tangles in the early Braak stages: entorhinal cortex, inferior temporal cortex, fusiform cortex and amygdala and averaged values bilaterally [19].

Statistical analyses

All analyses were done in SAS version 9.4. Group characteristics are represented in mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, or proportions for dichotomous data. Neocortical PiB was log-transformed because of its skewed distribution. Associations between adjusted brainstem volumes (or volumes of the control regions in separate models) and neocortical amyloid (PiB) or regional tau (FTP) deposition were examined using linear regression analyses, including age, sex and PET camera as covariates. We also examined whether neocortical amyloid burden would modify the association between brainstem volumes and tau burden by including the interaction between PiB and brainstem volume.

Sensitivity analyses were done on the PET data without PVC. Only associations that were significant in both the PVC and non-PVC analyses were considered robust and interpreted. All reported p-values are two-sided.

Results

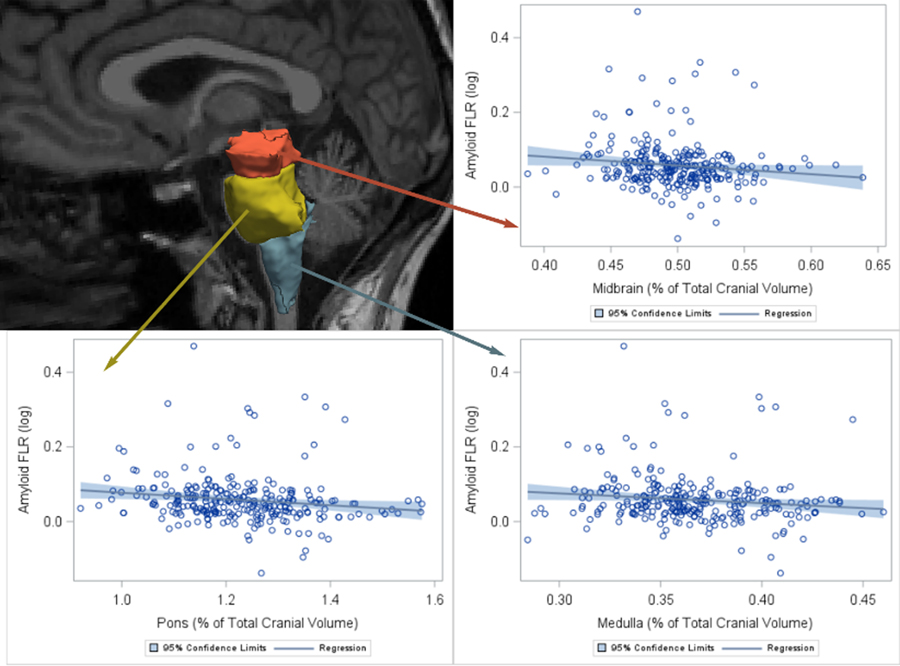

A description of the demographics of our sample is provided in Table 1. Lower midbrain volume was significantly associated with greater amygdala and fusiform tau (non-PVC), but these associations were at-trend or nonsignificant for the PVC tau data. We observed no other associations between any of the brainstem volumes and the regional tau measurements (Table 2). But, lower volume of the medulla, pons and midbrain were each associated with greater neocortical amyloid burden (Table 2 and Figure 1). In the non-PVC data, these relationships were also observed for the medulla and pons. These results did not change when adjusting the models for global cognition (PC1, Table S1) or APOE-E4 status (Table S2), or when removing potential influential PiB-values > 2SD from the mean (Table S3). In separate models, striatal volume or fourth ventricular volume were not associated with any of the PET variables, thus supporting the specificity of these findings. Hippocampal volume was not significantly associated with amyloid burden or tau pathology. No other associations between hippocampal volume and tau pathology were detected. We observed no interaction between neocortical amyloid burden and any of the brainstem volumes on cortical tau burden measures (Table 2).

Table 1:

Demographics of the sample

| N | Mean (SD) or n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at PET scan, Mean (SD) | 271 | 54 (8) |

| Age>60, n (%) | 62 (23%) | |

| Male, n (%) | 271 | 139 (51%) |

| APOE4, n (%) | 261 | 62 (24%) |

| Global cognition (PC1), Mean (SD) | 255 | 0.70 (0.78) |

| Brainstem Measures, Mean (SD) | ||

| Medulla, % of ICV | 271 | 0.37 (0.03) |

| Pons, % of ICV | 271 | 1.22 (0.12) |

| Midbrain, % of ICV | 271 | 0.50 (0.04) |

| PET measures (PVC) | ||

| Neocortical PiB, Median [Q1, Q3] | 267 | 1.13 [1.09 to 1.17]* |

| Entorhinal FTP, Mean (SD) | 238 | 1.20 (0.19) |

| Inferior Temporal FTP, Mean (SD) | 238 | 1.31 (0.14) |

| Fusiform FTP, Mean (SD) | 238 | 1.26 (0.11) |

| Amygdala FTP, Mean (SD) | 238 | 1.21 (0.17) |

Note:

: given the skewed distribution of this variable, the distribution is summarized here using the median and interquartile range.

Abbreviations: PET = Positron Emission Tomography; ICV = intracranial volume; PVC = partial volume correction; Q1 / Q3 = quartile 1/3, PiB= Pittsburgh Compound; FTP = Flortaucipir

Table 2:

Associations between brainstem volumes and Alzheimer’s disease pathology

| Predictor | Neocortical PiB | Entorhinal FTP | Inferior Temporal FTP | Fusiform FTP | Amygdala FTP |

|

| |||||

| N=267 | N=238 | N=238 | N=238 | N=238 | |

| Medulla | −0.12±0.06 (0.036) | 0.03±0.06 (0.677) | −0.04±0.06 (0.522) | −0.04±0.06 (0.545) | 0.03±0.06 (0.611) |

| Pons | −0.11±0.06 (0.047) | 0.01±0.07 (0.844) | −0.04±0.06 (0.482) | −0.02±0.07 (0.740) | −0.08±0.06 (0.213) |

| Midbrain | −0.13±0.06 (0.022) | −0.02±0.06 (0.783) | −0.11±0.06 (0.065) | −0.10±0.06 (0.123) | −0.12±0.06 (0.057) |

| Striatum | 0.02±0.06 (0.668) | −0.05±0.07 (0.463) | −0.01±0.06 (0.849) | −0.08±0.07 (0.227) | 0.01±0.07 (0.843) |

| Hippocampus * | 0.07±0.10 (0.520) | 0.13±0.12 (0.250) | −0.15±0.10 (0.140) | 0.05±0.11 (0.630) | −0.07±0.11 (0.56) |

| Fourth Ventricle ┼ | 0.02±0.06 (0.802) | −0.10±0.07 (0.137) | −0.08±0.06 (0.202) | −0.06±0.07 (0.412) | −0.01±0.07 (0.832) |

|

Interactions with neocortical PiB | |||||

| Medulla x Neocortical PiB | 0.530 | 0.480 | 0.870 | 0.98 | |

| Pons x Neocortical PiB | 0.460 | 0.690 | 0.360 | 0.62 | |

| Midbrain x Neocortical PiB | 0.170 | 0.490 | 0.960 | 0.68 | |

|

Non-PVC analyses | |||||

| Predictor | Neocortical PiB | Entorhinal FTP | Inferior Temporal FTP | Fusiform FTP | Amygdala FTP |

|

| |||||

| N=267 | N=238 | N=238 | N=238 | N=238 | |

| Medulla | −0.13±0.06 (0.024) | −0.01±0.06 (0.835) | −0.03±0.06 (0.645) | −0.04±0.06 (0.548) | −0.02±0.06 (0.755) |

| Pons | −0.13±0.06 (0.023) | −0.06±0.07 (0.335) | −0.09±0.06 (0.157) | −0.07±0.07 (0.300) | −0.12±0.06 (0.070) |

| Midbrain | −0.10±0.06 (0.094) | −0.06±0.06 (0.354) | −0.12±0.06 (0.054) | −0.14±0.06 (0.026) | −0.16±0.06 (0.011) |

| Striatum | 0.02±0.06 (0.726) | −0.10±0.07 (0.143) | −0.04±0.07 (0.522) | −0.11±0.07 (0.110) | −0.05±0.07 (0.422) |

| Hippocampus * | 0.05±0.10(0.600) | 0.23±0.12 (0.050) | −0.02±0.11 (0.850) | 0.06±0.11 (0.580) | 0.00±0.11 (0.97) |

|

Interactions with neocortical PiB | |||||

| Medulla x Neocortical PiB | 0.230 | 0.480 | 0.280 | 0.41 | |

| Pons x Neocortical PiB | 0.370 | 0.600 | 0.180 | 0.72 | |

| Midbrain x Neocortical PiB | 0.100 | 0.530 | 0.190 | 0.70 | |

Note: β±SE (p-value) presented unless otherwise specified. For interaction analyses only the p-value is presented. All models adjusted for age, sex, and camera. Analyses were also adjusted for total cranial volume. Neocortical PiB was log transformed for normality. Top section of the table shows the partial volume corrected (PVC)-results, the bottom part the non-PVC results.

: Number of observations for hippocampal volume was n=257 for associations with neocortical PiB and n=227 for tau measures.

: Number of observations for fourth ventricle was n=231 for associations with neocortical PiB and n=219 for tau measures.

Abbreviations: PVC = partial volume correction; PiB= Pittsburgh Compound; FTP = Flortaucipir

Figure 1.

Brainstem volumes are associated with neocortical PiB Unadjusted associations between the brainstem volume (as a % of total cranial volume) and neocortical PiB deposition (log-transformed, here referred to as amyloid FLR). FLR, fronto-lateral temporal–retrosplenial aggregate (neocortical region); PiB, Pittsburgh Compound B.”

Discussion

Several brainstem nuclei exhibit Alzheimer’s disease-related neurodegenerative processes early in adulthood [1], hence we examined associations between subregional brainstem volumes and the initial stages of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in a large cohort of middle-aged cognitively normal individuals. We found that lower brainstem volumes, in particular the medulla and the pons, were associated with greater beta-amyloid deposition. Contrary to our expectations, based on the Braak staging [4] and previous MRI-work [8], we did not observe robust relationships between any of the brainstem volumes and tau deposition. Effect sizes for the amygdala and fusiform gyrus – regions with strong connections with the brainstem - are in a similar range to those of neocortical PiB, providing some initial support for the hypothesis that neurodegenerative diseases including AD start in the brainstem. Interestingly, hippocampal volume was not associated with beta-amyloid or tau deposition in our sample. There is a plethora of studies reporting correlations between hippocampal volume and amyloid or tau pathology, or disease progression, in older or impaired individuals [20–24]. However, in younger or midlife individuals, previous studies reported no relationship between APOE genotyping and hippocampal volume [25–27], indicating that loss of grey matter tissue is a downstream effect of accumulating pathology[28]. In fact, recent work by Bussy et al. (2019) indicated that amyloid may already be accumulating at younger ages, prior to any measurable volumetric changes[25]. We observed that lower brainstem volumes were associated with initial amyloid accumulation in the neocortex, the earliest sign of preclinical AD. Based on these observations, we speculate that our associations between brainstem volumes and amyloid pathology reflect brain changes that occur prior to cortical neurodegeneration and thus may be valuable in the detection of preclinical AD. Other physiological markers of brainstem function, such as changes in heart rate variability, have also been associated with a greater risk of developing dementia. However, autopsy studies have identified a long time lag between tau deposition in the locus coeruleus and neuronal loss [29], indicating that the observed volumetric changes in the locus coeruleus may reflect loss of projection fiber density or other elements besides locus coeruleus neuronal loss. Similarly, while tau accumulation in the raphe nucleus occurs prior to cortical tau deposition, neuronal loss in the raphe nucleus was typically detected only in later Braak stages [6, 30]. Thus, the changes in brainstem volume may reflect processes other than tau deposition in brainstem nuclei. Previous volumetric MRI studies have already reported a relationship between lower brainstem volume and worse cognition in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease, but not in normal older individuals [7, 9] and no prior study has related brainstem volumes to brain amyloid and tau burden. It is important to note that these findings were specific to the brainstem, and not observed for any of the control regions, including the hippocampus. We did not yet probe the potential subtle functional implications of these Alzheimer’s disease-related changes in brainstem volume, but plan to do so when our sample size is large enough to capture cognitive variability in this cognitively healthy middle-aged population.

Unfortunately, detecting tau aggregation in vivo in these tiny nuclei of the brainstem is not yet feasible, due to the off-target binding of current tau radiotracers to neuromelanin [31, 32], which is abundantly present in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus. Novel emerging imaging methods may enable examination of the integrity of the locus coeruleus, substantia nigra and potentially also the other neuromodulatory subcortical systems, as well as their molecular alterations during aging or disease contributing to volumetric changes [33–35]. To better understand the temporal dynamics between volumetric changes and deposition of cortical beta-amyloid and tau, future studies should explore these associations through longitudinal studies that include repeated MRI and PET imaging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 AG049607 (to S.S.), R01 AG062559 (to H.I.L.J.), HHSN268201500001I and 75N92019D00031 (to S.S.). RFB is supported by a K99/R00 award from NIH-NIA (R00AG061238), an Alzheimer’s Association Research Fellowship and philanthropic support.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest to report.

References

- [1].Rub U, Stratmann K, Heinsen H, Turco DD, Seidel K, Dunnen W, Korf HW (2016) The Brainstem Tau Cytoskeletal Pathology of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Brief Historical Overview and Description of its Anatomical Distribution Pattern, Evolutional Features, Pathogenetic and Clinical Relevance. Curr Alzheimer Res 13, 1178–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rub U, Del Tredici K, Schultz C, Thal DR, Braak E, Braak H (2001) The autonomic higher order processing nuclei of the lower brain stem are among the early targets of the Alzheimer’s disease-related cytoskeletal pathology. Acta Neuropathol 101, 555–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Patthy A, Murai J, Hanics J, Pinter A, Zahola P, Hokfelt TGM, Harkany T, Alpar A (2021) Neuropathology of the Brainstem to Mechanistically Understand and to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. J Clin Med 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Braak H, Del Tredici K (2011) The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol 121, 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K (2011) Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 70, 960–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ehrenberg AJ, Nguy AK, Theofilas P, Dunlop S, Suemoto CK, Di Lorenzo Alho AT, Leite RP, Diehl Rodriguez R, Mejia MB, Rub U, Farfel JM, de Lucena Ferretti-Rebustini RE, Nascimento CF, Nitrini R, Pasquallucci CA, Jacob-Filho W, Miller B, Seeley WW, Heinsen H, Grinberg LT (2017) Quantifying the accretion of hyperphosphorylated tau in the locus coeruleus and dorsal raphe nucleus: the pathological building blocks of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 43, 393–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lee JH, Ryan J, Andreescu C, Aizenstein H, Lim HK (2015) Brainstem morphological changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport 26, 411–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dutt S, Li Y, Mather M, Nation DA, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2020) Brainstem Volumetric Integrity in Preclinical and Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 77, 1579–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dutt S, Li Y, Mather M, Nation DA, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2021) Brainstem substructures and cognition in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Imaging Behav 15, 2572–2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, Atwood LD, Cupples LA, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB, Fox CS, Larson MG, Murabito JM, O’Donnell CJ, Vasan RS, Wolf PA, Levy D (2007) The Third Generation Cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol 165, 1328–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tsao CW, Vasan RS (2015) Cohort Profile: The Framingham Heart Study (FHS): overview of milestones in cardiovascular epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 44, 1800–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI (1999) Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. NeuroImage 9, 179–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Iglesias JE, Van Leemput K, Bhatt P, Casillas C, Dutt S, Schuff N, Truran-Sacrey D, Boxer A, Fischl B, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2015) Bayesian segmentation of brainstem structures in MRI. NeuroImage 113, 184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, Becker JA, Sepulcre J, Rentz D, Mormino E, Chhatwal J, Amariglio R, Papp K, Marshall G, Albers M, Mauro S, Pepin L, Alverio J, Judge K, Philiossaint M, Shoup T, Yokell D, Dickerson B, Gomez-Isla T, Hyman B, Vasdev N, Sperling R (2016) Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 79, 110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pan T, Einstein SA, Kappadath SC, Grogg KS, Lois Gomez C, Alessio AM, Hunter WC, El Fakhri G, Kinahan PE, Mawlawi OR (2019) Performance evaluation of the 5-Ring GE Discovery MI PET/CT system using the national electrical manufacturers association NU 2–2012 Standard. Med Phys 46, 3025–3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wolf AP, Dewey SL, Schlyer DJ, MacGregor RR, Hitzemann R, Bendriem B, Gatley SJ, et al. (1990) Graphical analysis of reversible radioligand binding from time-activity measurements applied to [N-11C-methyl]-(−)-cocaine PET studies in human subjects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 10, 740–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Greve DN, Svarer C, Fisher PM, Feng L, Hansen AE, Baare W, Rosen B, Fischl B, Knudsen GM (2014) Cortical surface-based analysis reduces bias and variance in kinetic modeling of brain PET data. NeuroImage 92, 225–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jacobs HIL, Hedden T, Schultz AP, Sepulcre J, Perea RD, Amariglio RE, Papp KV, Rentz DM, Sperling RA, Johnson KA (2018) Structural tract alterations predict downstream tau accumulation in amyloid-positive older individuals. Nat Neurosci 21, 424–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Braak H, Del Tredici K (2015) The preclinical phase of the pathological process underlying sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 138, 2814–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jacobs HIL, Augustinack JC, Schultz AP, Hanseeuw BJ, Locascio J, Amariglio RE, Papp KV, Rentz DM, Sperling RA, Johnson KA (2020) The presubiculum links incipient amyloid and tau pathology to memory function in older persons. Neurology 94, e1916–e1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Schuff N, Woerner N, Boreta L, Kornfield T, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Thompson PM, Jack CR Jr., Weiner MW, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2009) MRI of hippocampal volume loss in early Alzheimer’s disease in relation to ApoE genotype and biomarkers. Brain 132, 1067–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].de Flores R, La Joie R, Chetelat G (2015) Structural imaging of hippocampal subfields in healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 309, 29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wisse LE, Biessels GJ, Heringa SM, Kuijf HJ, Koek DH, Luijten PR, Geerlings MI, Utrecht Vascular Cognitive Impairment Study G (2014) Hippocampal subfield volumes at 7T in early Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging. Neurobiol Aging 35, 2039–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Fennema-Notestine C, McEvoy LK, Hagler DJ, Holland D, Brewer JB, Dale AM, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I (2010) CSF biomarkers in prediction of cerebral and clinical change in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 30, 2088–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bussy A, Snider BJ, Coble D, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Cruchaga C, Benzinger TLS, Gordon BA, Hassenstab J, Bateman RJ, Morris JC, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer N (2019) Effect of apolipoprotein E4 on clinical, neuroimaging, and biomarker measures in noncarrier participants in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Neurobiol Aging 75, 42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Habes M, Toledo JB, Resnick SM, Doshi J, Van der Auwera S, Erus G, Janowitz D, Hegenscheid K, Homuth G, Volzke H, Hoffmann W, Grabe HJ, Davatzikos C (2016) Relationship between APOE Genotype and Structural MRI Measures throughout Adulthood in the Study of Health in Pomerania Population-Based Cohort. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 37, 1636–1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Reiman EM, Uecker A, Caselli RJ, Lewis S, Bandy D, de Leon MJ, De Santi S, Convit A, Osborne D, Weaver A, Thibodeau SN (1998) Hippocampal volumes in cognitively normal persons at genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 44, 288–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].de Flores R, Wisse LEM, Das SR, Xie L, McMillan CT, Trojanowski JQ, Robinson JL, Grossman M, Lee E, Irwin DJ, Yushkevich PA, Wolk DA (2020) Contribution of mixed pathology to medial temporal lobe atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 16, 843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Theofilas P, Ehrenberg AJ, Dunlop S, Di Lorenzo Alho AT, Nguy A, Leite REP, Rodriguez RD, Mejia MB, Suemoto CK, Ferretti-Rebustini REL, Polichiso L, Nascimento CF, Seeley WW, Nitrini R, Pasqualucci CA, Jacob Filho W, Rueb U, Neuhaus J, Heinsen H, Grinberg LT (2017) Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer’s disease progression: A stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discovery. Alzheimers Dement 13, 236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Grinberg LT, Rub U, Ferretti RE, Nitrini R, Farfel JM, Polichiso L, Gierga K, Jacob-Filho W, Heinsen H, Brazilian Brain Bank Study G (2009) The dorsal raphe nucleus shows phospho-tau neurofibrillary changes before the transentorhinal region in Alzheimer’s disease. A precocious onset? Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 35, 406–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lee CM, Jacobs HIL, Marquie M, Becker JA, Andrea NV, Jin DS, Schultz AP, Frosch MP, Gomez-Isla T, Sperling RA, Johnson KA (2018) 18F-Flortaucipir Binding in Choroid Plexus: Related to Race and Hippocampus Signal. J Alzheimers Dis 62, 1691–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Marquie M, Normandin MD, Vanderburg CR, Costantino IM, Bien EA, Rycyna LG, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Ikonomovic MD, Debnath ML, Vasdev N, Dickerson BC, Gomperts SN, Growdon JH, Johnson KA, Frosch MP, Hyman BT, Gomez-Isla T (2015) Validating novel tau positron emission tomography tracer [F-18]-AV-1451 (T807) on postmortem brain tissue. Ann Neurol 78, 787–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Priovoulos N, Jacobs HIL, Ivanov D, Uludag K, Verhey FRJ, Poser BA (2018) High-resolution in vivo imaging of human locus coeruleus by magnetization transfer MRI at 3T and 7T. NeuroImage 168, 427–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Betts MJ, Kirilina E, Otaduy MCG, Ivanov D, Acosta-Cabronero J, Callaghan MF, Lambert C, Cardenas-Blanco A, Pine K, Passamonti L, Loane C, Keuken MC, Trujillo P, Lusebrink F, Mattern H, Liu KY, Priovoulos N, Fliessbach K, Dahl MJ, Maass A, Madelung CF, Meder D, Ehrenberg AJ, Speck O, Weiskopf N, Dolan R, Inglis B, Tosun D, Morawski M, Zucca FA, Siebner HR, Mather M, Uludag K, Heinsen H, Poser BA, Howard R, Zecca L, Rowe JB, Grinberg LT, Jacobs HIL, Duzel E, Hammerer D (2019) Locus coeruleus imaging as a biomarker for noradrenergic dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Brain 142, 2558–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Jacobs HIL, Becker JA, Kwong K, Engels-Dominguez E, Prokopiou PC, Papp KV, Properzi M, Hampton OL, D’Oleire Uquillas F, Sanchez JS, Rentz DM, El Fakhri G, Normandin MD, Price JC, Bennett DA, Sperling RA, Johnson KA (2021) In vivo and neuropathology data support locus coeruleus integrity as indicator of Alzheimer’s disease pathology and cognitive decline. Sci Transl Med 13, eabj2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.