Abstract

The objective of this observational study was to assess the genetic variability in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease gene from HIV type 1 (HIV-1)-positive (clade B), protease inhibitor-naïve patients and to evaluate its association with the subsequent effectiveness of a protease inhibitor-containing triple-drug regimen. The protease gene was sequenced from plasma-derived virus from 116 protease inhibitor-naïve patients. The virological response to a triple-drug regimen containing indinavir, ritonavir, or saquinavir was evaluated every 3 months for as long as 2 years (n = 40). A total of 36 different amino acid substitutions compared to the reference sequence (HIV-1 HXB2) were detected. No substitutions at the active site similar to the primary resistance mutations were found. The most frequent substitutions (prevalence, >10%) at baseline were located at codons 15, 13, 12, 62, 36, 64, 41, 35, 3, 93, 77, 63, and 37 (in ascending order of frequency). The mean number of polymorphisms was 4.2. A relatively poorer response to therapy was associated with a high number of baseline polymorphisms and, to a lesser extent, with the presence of I93L at baseline in comparison with the wild-type virus. A71V/T was slightly associated with a poorer response to first-line ritonavir-based therapy. In summary, within clade B viruses, protease gene natural polymorphisms are common. There is evidence suggesting that treatment response is associated with this genetic background, but most of the specific contributors could not be firmly identified. I93L, occurring in about 30% of untreated patients, may play a role, as A71V/T possibly does in ritonavir-treated patients.

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease is an essential enzyme for viral replication, and the use of protease inhibitors results in the production of noninfectious virions (20). The clinical use of protease inhibitors in association with two nucleoside reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors (NRTI) has recently reduced HIV-related morbidity and mortality (18). Unfortunately, protease inhibitor-resistant variants have appeared, under both in vitro and in vivo conditions, for all compounds. The fast selection of drug-resistant virus has been attributed to the high replication rate of HIV and the error-prone nature of the viral RT (11). Specific patterns of drug resistance mutations have been associated with each compound; furthermore, a large cross-resistance between drugs is likely to emerge under prolonged drug pressure (5, 23).

The HIV protease gene sequences from the clinical cohort in the present study displayed many differences from that of a clade B reference strain. This was referred to as gene variability or natural polymorphisms observed prior to the clinical use of any protease inhibitor. The protease from a sample of untreated patients has shown substitutions affecting more than 45% of the amino acid residues, compatible with sufficient flexibility of the enzyme (13, 24). The impact of these polymorphisms on treatment outcome has yet to be understood (1, 2). Primary resistance mutations located at the active site arise upon treatment. They generally cause decreased inhibitor binding and are often selected first (10), possibly conferring an altered viral fitness. Sooner or later secondary mutations, remote from the active site and having less effect on inhibitor binding in vitro (10), may compensate and restore normal viral replication capacity (12). With greater use of protease inhibitors, person-to-person transmissions of protease inhibitor-resistant virus have been reported (9).

In order to investigate the protease gene polymorphisms, we sequenced the protease gene for a cohort of protease inhibitor-naïve patients and evaluated the association between amino acid substitutions and virological outcome for patients under treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and treatment.

In an observational study, 116 HIV-1 clade B-infected patients monitored at the National Infectious Diseases Department (Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg) were screened for the variability of the protease gene. The first available isolate before protease inhibitor treatment was used for each patient. Forty-five percent of the isolates were obtained before the clinical use of protease inhibitors in 1996. Baseline data were obtained at initiation of protease inhibitor therapy. Later, 73 patients from this initial cohort were treated with a protease inhibitor and two NRTI. Genotypic or phenotypic resistance testing was not used to guide treatment. Anti-HIV treatment was changed during the follow-up period according to the physician's choice. Forty patients with a follow-up period of at least 24 months on protease inhibitor treatment were included in order to study the association between baseline amino acid substitutions and treatment outcome. A long follow-up period was required for this analysis of polymorphisms possibly indirectly related to drug resistance. NRTI-experienced patients differed in CD4 counts from naive patients; 14 of 19 (74%) had fewer than 200 CD4+ cells/μl compared to 7 of 21 (33%; P = 0.011), although the proportions of patients with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stage C disease (3) did not differ between the two groups (5 of 19 [26%] and 5 of 21 [24%], respectively [P = 1.000]). Patient characteristics and treatment regimens are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The median time between sampling and initiation of protease inhibitor treatment was 7.13 months (quartiles, 1.89 to 37.54). Thirty-three patients, initially treated with a protease inhibitor, could not be evaluated for a full 24 months for the following reasons: 14 patients (43%) discontinued protease inhibitor treatment, 11 patients (34%) had been treated for fewer than 24 months, 6 patients (17%) were lost at follow-up, and 2 (6%) died. In order to exclude a possible selection bias, patients with fewer than 24 months of follow-up were evaluated for additional confounding factors.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Value for group

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Initial cohort (n = 116) | Patients treated with protease inhibitor for 24 mo (n = 40) | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 36.7 ± 10.7 | 38.2 ± 10.4 |

| No. (%) of females | 17 (15) | 7 (18) |

| No. (%) non-Caucasian | 7 (6) | 2 (5) |

| No. (%) with risk factors | ||

| Heterosexual | 28 (24) | 9 (22) |

| Homosexual | 70 (60) | 29 (72) |

| Drug user | 16 (14) | 1 (3) |

| Transfusion | 2 (2) | 1 (3) |

| Time from seroconversion (yr, mean ± SD) | 4.1 ± 4.2 | 2.8 ± 3.4 |

| No. (%) at CDC clinical stagea | 25 (22) | 10 (25) |

| Viral load (mean log10 copies/ml ± SD) | 4.63 ± 0.64 | 4.75 ± 0.55 |

| CD4+ cell count (mean no. of cells/μl ± SD) | 390 ± 327 | 265 ± 209 |

| Prior nucleoside analogue therapy (%) | 20 | 53 |

| No. of drugs (range) | 1.1 (0–3) | 1.3 (0–3) |

| Time in yr (range) | 0.7 (0–5) | 10.7 (0–5) |

According to the 1993 classification of the CDC (3).

TABLE 2.

Treatment regimens of the patients treated for 2 years with protease inhibitor (n = 40)

| Drug (dose) | No. (%) at:

|

Duration prior to switch (mean mo ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Mo 24 | ||

| Protease inhibitors | |||

| Indinavir (800 mg t.i.d.) | 13 (33) | 19 (47.5) | 14.3 ± 8.3 |

| Ritonavir (600 mg b.i.d.) | 17 (42) | 3 (7.5) | 20.1 ± 9.7 |

| Saquinavira (600 mg t.i.d.) | 10 (25) | 9 (22.5) | 24.7 ± 6.3 |

| Nelfinavir (750 mg t.i.d.) | 7 (17.5) | ||

| Ritonavir + indinavir (200 mg b.i.d./800 mg b.i.d.) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Saquinavir + nelfinavir (600 mg t.i.d./750 mg t.i.d.) | 1 (2.5) | ||

| NRTIb | |||

| ZDV + ddC | 16 (40) | 9 (22.5) | |

| ZDV + 3TC | 14 (35) | 12 (30) | |

| D4T + 3TC | 5 (12.5) | 15 (37.5) | |

| 3TC + ddC | 2 (5) | 1 (2.5) | |

| d4T + ddI | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | |

| ddI + 3TC | 1 (2.5) | ||

| ZDV + ddI | 1 (2.5) | ||

| d4T + ddI | 1 (2.5) | ||

| d4T + ddI + HU | 1 (2.5) | ||

Hard gel formulation.

ZDV, zidovudine (300 mg b.i.d.); ddC, zalcitabine (0.75 mg t.i.d.); 3TC, lamivudine (150 mg b.i.d.); d4T, stavudine (40 mg b.i.d.); ddI, didanosine (200 mg b.i.d.); HU, hydroxyurea (500 mg b.i.d.).

Sequencing of the protease gene.

Direct cycle sequencing of the whole coding region of the protease gene from plasma virions was used with the dye terminator technology on an ABI 377 sequencer (ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Core Kit; Perkin-Elmer, Warrington, United Kingdom). The primers and conditions for the cDNA synthesis, the PCR amplifications, and the sequencing reactions have been described previously (25). Phenol-chloroform purification of PCR products was performed. The nucleotide sequences were translated into amino acids and compared to the HIV-1 clade B reference strain HXB2 (GenBank/EMBL accession number K03455) with ABI Sequence Navigator software. Mixtures of mutant and wild-type strains were considered mutants. Protease inhibitor resistance-related mutations are listed in Table 3 (22).

TABLE 3.

Amino acid changes related to protease inhibitor resistance

| Protease inhibitor | Residue(s) at the indicated position associated with protease inhibitor resistancea

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 10 | 20 | 24 | 30 | 32 | 33 | 36 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 50 | 54 | 63 | 71 | 73 | 77 | 82 | 84 | 88 | 90 | |

| None (reference) | R | L | K | L | D | V | L | M | M | I | G | I | I | L | A | G | V | V | I | N | L |

| Indinavir | IRV | MR | I | I | IL | V | P | TV | S | AFT | V | M | |||||||||

| Ritonavir | Q | I | R | I | F | I | I | VL | V | AFTS | V | M | |||||||||

| Saquinavir | I | V | V | S | A | V | M | ||||||||||||||

| Nelfinavir | N | I | I | P | V | I | V | D | M | ||||||||||||

| Amprenavir | IVF | R | I | F | IL | V | V | LMV | I | V | |||||||||||

Primary resistance mutations (located in the drug binding pocket, contributing to phenotypic drug resistance and often selected first) are boldfaced.

Plasma viral load.

Plasma HIV-1 load was measured by a second-generation branched-DNA assay (Quantiplex 2.0; Chiron, Cergy-Pontoise, France) following the manufacturer's recommendations. This test has a detection limit of 500 RNA copies per ml.

Virological outcomes.

Virological response was determined as the change in log10 HIV-1 RNA following initiation of protease inhibitor-based therapy. It was assessed every 3 months for as long as 24 months. RNA values reported as fewer than 500 copies/ml were considered equivalent to 250 copies/ml, as previously suggested (7). The time to virological failure, defined as a decrease from the baseline viral load (VL) of fewer than 1 log10 copies/ml, was also assessed. For patients never achieving a reduction of 1 log10 unit, failure was considered to occur from the first time point on.

Predictor variables.

Baseline characteristics were assessed as predictors of treatment response. These variables included the presence of individual polymorphisms versus wild-type codon, a high (>5) versus a low number of polymorphisms, CDC clinical stage C versus stage A or B, prior exposure to NRTI (number of drugs used, duration, experienced versus naïve status), CD4 stage 3 versus stage 1 or 2 (<200 versus ≥200 CD4+ cells/μl) (3), and high (≥5 log10 copies) versus low (<5 log10 copies) HIV-1 RNA levels. In order to facilitate clinical interpretation, baseline CD4 cells and VL were treated as categorical predictor variables, since modeling them either as continuous or as categorical variables gave the same results. Factors related to first-line combination therapy were the use of saquinavir (SQV, hard gel formulation) versus indinavir (IDV) or ritonavir (RTV) and the period the initial protease inhibitor was given. Compliance could not be reliably scored with data recorded in the past. Mutations related to protease inhibitor resistance were differentiated into primary and secondary mutations (Table 3) (10, 22).

Statistics.

The patients were divided into groups defined by the nature or the number of baseline protease polymorphisms. The virological response data were normally distributed within each group with equal variances. Thus a t test could be used to assess a differential response between groups with even a small sample size (crude analysis). Since an exploratory study has multiple observations, trends have to be confirmed from different angles. All variable analyses thought to confound the relationship between polymorphisms and virological outcome (confounders) were adjusted by two methods. First, the risk of developing virological failure (time-to-event data) was modeled using semiparametric Cox proportional-hazards regression (6). All predictor variables were categorical except for those related to the number of drugs or the exposure time. Only significant predictors were included in the final model. Forward stepwise analysis was based on log likelihood ratio, with probability for stepwise entry set to 0.05. This allowed identification of the stronger predictors. Second, the slope coefficient of a multiple linear regression measured longitudinally the association between the presence of baseline predictors and virological response. A positive association was related to a poorer response magnitude (Δ log copies per milliliter). The model was fitted as follows: the presence of a possible risk factor was set to one and its absence to zero. This allowed analysis both of weaker associations and of the postfailure period. The P values resulted from a t test on the slope coefficient and were adjusted for confounders and for all relevant polymorphisms in multivariate models. Subset univariate and multivariate analyses of only those patients assigned to a particular protease inhibitor were performed to evaluate more-specific associations. To handle the fact that polymorphisms might be predictors that are not completely independent from each other, various restricted models were built by excluding single polymorphisms, rather than summing substitutions not thought to be involved in resistance as a sum. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 9.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, Ill., 1999).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

All sequences were submitted to the GenBank/EMBL databases and are available under accession numbers AJ10714 to AJ10723, AJ12425 to AJ12435, and AJ279592 to AJ279685.

RESULTS

Polymorphisms of the HIV-1 protease from untreated patients.

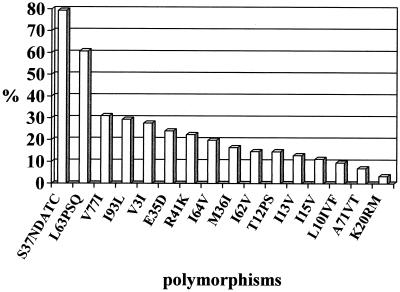

All viruses were confirmed to be clade B by submission of the protease sequence to the HIV-1 subtyping tool (http: //www.hiv-web.lanl.gov) (19) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Among the 116 samples, a total of 36 different amino acid substitutions were found compared to the HIV-1 HXB2 reference. The mean number of substitutions was 4.2 per isolate. Eleven isolates (10%) had fewer than 2 substitutions, 77 isolates (66%) had 2 to 5 substitutions, and 28 isolates (24%) had more than 5 (up to 14) substitutions. The most frequent substitutions (prevalence, >10%) were located at codons 15, 13, 12, 62, 36, 64, 41, 35, 3, 93, 77, 63, and 37 (in ascending order of frequency). Figure 1 gives the prevalence of substitutions. Prevalences in isolates obtained before and after the introduction of protease inhibitors in 1996 (means ± standard errors of the mean [SEM] (4.06 ± 0.32 and 4.16 ± 0.26, respectively) did not differ significantly. Certain polymorphisms showed amino acid substitutions (Fig. 1) similar to those of the so-called secondary resistance mutations (Table 3) (10, 22). In contrast, no active-site substitutions were found.

FIG. 1.

Most-frequent polymorphisms in the protease gene in protease inhibitor-naïve patients. The prevalences of L63P and L63S/Q were 43 and 18%, respectively.

Relative hazard for virological failure.

Patients who either had CDC clinical stage C disease at baseline, harbored a virus with a high number (>5) of polymorphisms, or harbored a virus with I93L or A71V/T (Table 4) had a greater relative risk of developing virological failure (Cox regression analysis; 95% confidence interval (95% CI), >1.00) than those lacking the characteristic. In contrast, prior nucleoside analogue therapy (either the experienced-versus-naïve status, the number of prior NRTI, or the time of prior exposure), high baseline VL, low CD4 counts, and the presence of other polymorphisms were not significant risk factors for failure in the study's cohort. The first-line use of SQV versus IDV or RTV was associated with a higher risk of developing failure. No association was observed for the time elapsed before a patient was switched to another protease inhibitor. A higher relative risk for developing failure was associated with a high number of polymorphisms or the presence of I93L at baseline independently of the presence of clinical stage C (multivariate analyses). A71V/T was still a predictor in the same model when I93L was not considered (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Baseline characteristics and RH of developing virological failurea

| Predictor | No. of patients with characteristic (n = 40) | RH (95% CI) by:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate (crude) analysis | Multivariate (adjusted) analysis

|

||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| High (>5) vs low no. of polymorphisms | 7 vs 33 | 3.45 (1.28–9.23) | 7.14 (2.26–22.50) | ||

| CDC stage C vs A or B | 10 vs 30 | 3.58 (1.41–9.06) | 4.77 (1.62–14.12) | 4.57 (1.54–13.56) | 4.35 (1.46–12.90) |

| I93L vs wild type | 10 vs 30 | 2.97 (1.18–7.45) | 3.17 (1.19–8.47) | ||

| A71V/T vs wild type | 5 vs 35 | 3.45 (1.10–10.77) | 3.74 (0.96–14.54) | 4.66 (1.17–18.48) | |

| First-line SQV hard gel vs IDV or RTV | 10 vs 30 | 6.17 (1.61–23.63) | 2.42 (0.88–6.61) | 1.83 (0.66–5.08) | 2.94 (1.206–8.11) |

| CD4 stage 3 vs 1 or 2 | 21 vs 19 | 1.43 (0.57–3.57) | |||

| Prior nucleoside analogue therapy vs naïve status | 21 vs 19 | 1.19 (0.48–2.94) | |||

| High (>5 log10 copies/ml) vs low VL | 13 vs 27 | 0.68 (0.24–1.90) | |||

A Cox regression analyzed if the presence of baseline characteristics was significantly (95% CI > 1.00) associated with a higher relative risk for developing virological failure, defined as a decrease from baseline VL of fewer than 1 log10 copies/ml. Prior nucleoside analogue therapy, high baseline VL, and low CD4 counts were not significant risk factors for failure. Various restricted multivariate models were built, as those predictors were not independent from each other. Model 1—excluding the variable high number of polymorphisms—studied the nature of polymorphisms and identified I93L as a significant risk factor independently from the clinical stage and the initial protease inhibitor (confounders). A71V/T was a predictor when I93L was excluded from the model (model 2). A high number of polymorphisms was a predictor (model 3) independent of the confounders in a model excluding the nature of polymorphisms.

The stronger baseline relative risk factors were, in decreasing order, CDC stage C, I93L, and first-line SQV (stepwise analysis). In a second analysis, a high number of polymorphisms was a stronger predictor than CDC clinical stage C (Table 4).

In the subgroup of patients treated with IDV or RTV, the presence of I93L (in 7 and 23 patients, respectively) was associated with a higher risk of developing treatment failure (relative hazard [RH], 3.47 [95% CI, 1.05 to 11.52], unadjusted). For the SQV arm, no significant predictors were identified.

Assessment of treated patients (n = 73) with different follow-up periods did not provide any different predictors (not shown). Subset analysis of isolates obtained before or after the clinical use of protease inhibitors gave similar results (data not shown).

Longitudinal analysis of virological response.

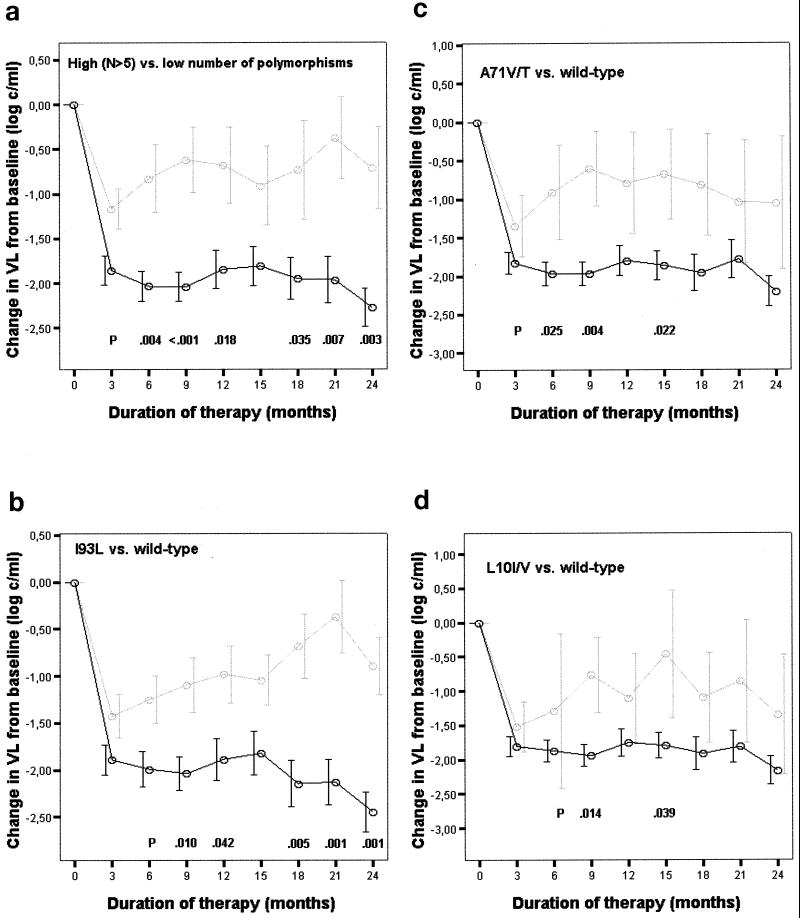

Out of a possible 40 VL data per time point, a mean of 4.0 ± 3.7 were missing. Patients harboring a virus with more than 5 polymorphisms at baseline had a significantly poorer virological response than those infected by a virus with fewer substitutions (Fig. 2a). This difference was already detectable after 3 months of treatment and was maintained over the whole study period. A poorer response from month 3 to month 6 was also associated with clinical AIDS at baseline. A higher magnitude of response from month 3 to month 9 was related to a high initial VL (Table 5). Therefore, both factors were included as confounders in adjusted analyses showing that a poorer response was independently associated with a high number of polymorphisms at months 3 to 12 and 18 to 24 (Table 5).

FIG. 2.

Virological response (mean changes in log10 HIV-1 RNA copies following initiation of protease inhibitor-based therapy) over time (up to 24 months). (a) Patients grouped by low (< 6; n = 7) (solid line) and high (≥6; n = 33) (shaded line) numbers of polymorphisms at baseline. (b) Patients with (n = 10) (solid line) or without (n = 30) (shaded line) the I93L polymorphism in the baseline sample. (c) Patients with (n = 5) (shaded line) or without (n = 35) (solid line) the A71V/T polymorphism in the baseline sample. (d) Patients with (n = 5) (shaded line) or without (n = 35) (solid line) the L10I/V polymorphism in the baseline sample. Error bars, show means ± 1 SEM. P values are from an unpaired t-test.

TABLE 5.

Association between baseline characteristics and virological response

| Group and analysis | Characteristica | Slope coefficient of the regression (P)b at:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo 3 | Mo 6 | Mo 9 | Mo 12 | Mo 15 | Mo 18 | Mo 21 | Mo 24 | ||

| All patients (n = 40) | |||||||||

| Univariate | CDC stage C vs A or B | 0.77 (0.011) | 0.83 (0.047) | 0.53 (0.161) | 0.34 (0.446) | 0.16 (0.725) | 0.50 (0.338) | 0.27 (0.617) | 0.51 (0.290) |

| High vs low VL | −0.69 (0.019) | −0.98 (0.004) | −0.71 (0.045) | −0.57 (0.171) | −0.16 (0.740) | −0.60 (0.218) | −0.51 (0.379) | −0.90 (0.039) | |

| Multivariate analysis, model 1 | >5 vs ≤5 polymorphisms | 0.83 (0.007) | 1.27 (<0.001) | 1.51 (<0.001) | 1.22 (0.016) | 0.98 (0.055) | 1.28 (0.029) | 1.71 (0.005) | 1.59 (0.002) |

| CDC stage C vs A or B | 0.77 (0.006) | 0.84 (0.010) | 0.63 (0.047) | 0.37 (0.396) | 0.26 (0.568) | 0.50 (0.419) | 0.45 (0.381) | 0.47 (0.274) | |

| High vs low VL | −0.58 (0.031) | −0.90 (0.002) | −0.54 (0.070) | −0.44 (0.293) | −0.01 (0.977) | −0.36 (0.442) | −0.64 (0.238) | −0.86 (0.036) | |

| Multivariate analysis, model 2 | CDC stage C vs A or B | 0.81 (0.006) | 1.04 (0.002) | 0.57 (0.070) | 0.33 (0.465) | 0.37 (0.426) | 0.39 (0.460) | 0.13 (0.793) | 0.47 (0.264) |

| High vs low VL | −0.73 (0.008) | −0.99 (0.001) | −0.62 (0.036) | −0.48 (0.243) | −0.36 (0.441) | −0.50 (0.289) | −0.23 (0.661) | −0.62 (0.092) | |

| L10I/V vs wild type | −0.06 (0.873) | 0.43 (0.415) | 0.50 (0.245) | −0.70 (0.910) | 0.17 (0.802) | 0.17 (0.802) | 0.28 (0.674) | −0.23 (0.674) | |

| E35D vs wild type | −0.30 (0.288) | 0.03 (0.918) | 0.08 (0.798) | 0.47 (0.346) | 0.14 (0.790) | 0.14 (0.790) | 0.93 (0.045) | 0.93 (0.029) | |

| A71V/T vs wild type | 0.70 (0.081) | 0.93 (0.045) | 1.23 (0.008) | 0.92 (0.152) | 0.76 (0.288) | 0.76 (0.288) | 0.17 (0.808) | 0.96 (0.097) | |

| I93L vs wild type | 0.30 (0.280) | 0.65 (0.057) | 0.57 (0.070) | 0.65 (0.167) | 1.17 (0.038) | 1.17 (0.038) | 1.59 (0.004) | 1.24 (0.003) | |

| RTV subgroup (n = 17) | |||||||||

| Univariate | L10I/V vs wild type | 0.75 (0.082) | 2.69 (0.016) | 1.85 (0.006) | 1.52 (0.021) | 1.99 (0.015) | 1.53 (0.079) | 2.35 (0.002) | 2.02 (0.030) |

| E35D vs wild type | 0.68 (0.054) | 1.35 (0.066) | 1.57 (0.005) | 1.52 (0.004) | 1.24 (0.074) | 1.92 (0.005) | 2.03 (0.001) | 2.08 (0.005) | |

| A71V/T vs wild type | 0.94 (0.023) | 1.60 (0.025) | 1.63 (0.018) | 1.41 (0.036) | 1.56 (0.012) | 1.52 (0.082) | 1.37 (0.113) | 1.57 (0.102) | |

| I93L vs wild type | 0.74 (0.036) | 0.68 (0.382) | 1.43 (0.038) | 0.45 (0.457) | 0.88 (0.271) | 0.57 (0.467) | 1.27 (0.077) | 0.96 (0.244) | |

| Multivariate | CDC stage C vs A or B | 0.24 (0.542) | 1.34 (0.210) | 0.42 (0.393) | 0.27 (0.609) | 0.74 (0.218) | 0.30 (0.674) | 0.91 (0.171) | 0.56 (0.564) |

| High vs low VL | −0.46 (0.157) | −1.04 (0.050) | −0.57 (0.156) | −0.61 (0.208) | 0.23 (0.677) | −0.36 (0.557) | 0.11 (0.984) | −0.61 (0.428) | |

| L10I/V vs wild type | −0.27 (0.589) | 2.02 (0.162) | 0.56 (0.366) | 0.08 (0.911) | 0.94 (0.213) | −0.74 (0.411) | 0.44 (0.586) | −0.23 (0.853) | |

| E35D vs wild type | 0.48 (0.278) | −0.12 (0.879) | 0.82 (0.138) | 0.94 (0.046) | 0.55 (0.340) | 2.10 (0.028) | 1.24 (0.096) | 0.93 (0.040) | |

| A71V/T vs wild type | 0.93 (0.035) | 1.39 (0.047) | 1.82 (0.003) | 1.68 (0.010) | 2.09 (0.015) | 1.82 (0.029) | 1.39 (0.052) | 1.74 (0.090) | |

| I93L vs wild type | 0.38 (0.266) | 0.55 (0.481) | −0.27 (0.503) | −0.29 (0.512) | −0.63 (0.303) | 0.02 (0.968) | 0.35 (0.508) | 0.07 (0.929) | |

| SQV subgroup (n = 10) | |||||||||

| Univariate | L10I/V vs wild type | −1.96 (0.175) | −1.52 (0.234) | −0.35 (0.757) | −1.73 (0.250) | −0.60 (0.261) | −1.88 (0.200) | −1.95 (0.214) | −2.07 (0.152) |

| A71V/T vs wild type | −0.86 (0.448) | −0.15 (0.879) | 0.51 (0.545) | −0.06 (0.957) | −0.25 (0.567) | −0.42 (0.728) | 0.14 (0.916) | 0.20 (0.859) | |

| I93L vs wild type | −0.12 (0.908) | 1.03 (0.214) | 1.47 (0.019) | 1.50 (0.112) | 0.44 (0.297) | 2.18 (0.010) | 2.59 (0.009) | 2.39 (0.001) | |

| Multivariate | CDC stage C vs A or B | 2.22 (0.319) | 1.62 (0.196) | 1.17 (0.136) | 1.47 (0.529) | 1.09 (0.129) | −0.75 (0.593) | 0.09 (0.944) | 0.47 (0.484) |

| High vs low VL | −0.89 (0.506) | −0.28 (0.829) | −0.27 (0.732) | 1.30 (0.631) | −0.69 (0.297) | −1.83 (0.358) | −0.74 (0.406) | −0.51 (0.518) | |

| L10I/V vs wild type | −0.15 (0.835) | −1.09 (0.653) | 0.63 (0.663) | −3.08 (0.453) | −0.18 (0.854) | 2.41 (0.486) | 1.63 (0.189) | −1.18 (0.422) | |

| A71V/T vs. wild type | 0.91 (0.643) | 1.13 (0.589) | 0.47 (0.704) | 2.63 (0.538) | −0.31 (0.697) | −2.66 (0.364) | −0.65 (0.629) | 0.50 (0.682) | |

| I93L vs wild type | 1.21 (0.384) | 1.18 (0.284) | 1.82 (0.029) | 0.50 (0.801) | 0.49 (0.448) | 1.37 (0.047) | 2.95 (0.031) | 2.36 (0.011) | |

The presence of a possible risk factor (the first characteristic in each row) was assigned a value of 1, while its absence (the second characteristic in each row) was assigned a value of 0.

The slope coefficient of the linear regression measures the association between the presence of baseline characteristics and virological response. A positive slope indicates a poorer response magnitude (Δ log copies per milliliter). For the first months of therapy, a poorer response was associated with clinical AIDS at baseline, and a higher response magnitude was associated with a high baseline VL (>5 log10 copies/ml). In multivariate analyses, the P values were adjusted for these two factors and for polymorphisms (either the number [model 1] or the nature [model 2] of polymorphisms) relevant by t test. Baseline factors such as a CD4 stage 3 (<200 CD4+ cells/μl) and the number of previously used nucleoside analogues were not associated with a poorer response (data not shown). Subset analyses, univariate and multivariate, for adjustment of P values, were performed for patients assigned to a specific protease inhibitor. The IDV subgroup did not show any trend (data not shown).

The presence at baseline of I93L, compared to the wild type, was associated with a poorer treatment response (Fig. 2b). The difference increased over time and reached statistical significance at 9 and 12 months and again from 18 months of therapy on. In multiple regression I93L was a risk factor for poorer response independent of the confounders and other polymorphisms from months 15 to 24 (Table 5). When A71V/T was excluded, the same association was present, even at month 6 (slope, 0.99 ± 0.30; P = 0.003), month 9 (slope, 0.82 ± 0.32; P = 0.014), and month 12 (slope, 0.86 ± 0.40; P = 0.047).

A poorer response was slightly associated with A71V/T (Fig. 2c). Despite large SEM of the virological response due to the small sample size of the group defined by the low-prevalence A71V/T polymorphism, significance was still reached at months 6, 9, and 15 in crude analyses. In analyses adjusted for the confounders and other polymorphisms, A71V/T was still associated with a poorer response at months 6 and 9 (Table 5). It became also significant at month 12 (slope, 1.21 ± 0.59; P = 0.045) when I93L was excluded and at month 15 (slope, 1.31 ± 0.60; P = 0.040) when L10I/V was not considered.

No significant difference was found between patients with and without the L63P substitution. Combining both L63P and I93L did not give additional significance.

A poorer response was slightly associated with the presence of L10I/V at baseline, but this association reached significance only at months 9 and 15 in crude analyses. For some of the other time points for which significance was not reached (Fig. 2d), the SEM were larger due to a smaller sample size of the group defined by this low-prevalence substitution. After controlling for confounders and other polymorphisms, a poorer response was no longer associated with baseline L10I/V (Table 5). When A71V/T was excluded, L10I/V remained a risk factor for months 9 (slope, 0.94 ± 0.44; P = 0.038) and 15 (slope, 1.32 ± 0.58; P = 0.039).

Analysis of polymorphisms at codon 15 or 36 did not show any trend. The group defined by the V77I substitution displayed a nonsignificant difference at month 6 (−2.11 ± 0.71 versus −1.17 ± 0.90 log10 copies/ml; P = 0.070). V77I was correlated with A71V/T (r = 0.41). The prevalence of K20R/M was too low to allow analysis.

A poorer response was weakly associated with E35D at baseline, but this association reached significance only at month 21 (−1.97 ± 0.26 versus −0.83 ± 0.46 log10 copies/ml; n = 10 versus 30; P = 0.036) and at month 24 (−2.34 ± 0.22 versus −1.20 ± 0.43 log10 copies/ml; P = 0.015) in crude analyses. In multiple regression this association remained significant for the same time points after adjustment for confounders and other polymorphisms (Table 5).

The patient group defined by first-line IDV, having a lower prevalence (median, less than 2) of substitutions, ranging from 0 for A71VT to 5 for E35D, did not show any significant associations. For first-line RTV-treated patients, a relatively poorer response was associated with baseline I93L at months 3 and 9 in a crude analysis (Table 5), but only at month 9 in a multivariate analysis excluding A71V/T (data not shown). I93L was a risk factor for a poorer response in the SQV arm at months 9 and 18 to 24 in adjusted analysis (Table 5). Analysis of L63P displayed a nonsignificant sustained difference for patients under RTV therapy (data not shown), whereas no trend was observed for the IDV and SQV arms. In the RTV-treated patient group, a poorer response was significantly associated with A71V/T at months 3 to 15 and with L10I/V at months 6 to 15 and 21 to 24 in crude analyses (Table 5). Analysis adjusted for the clinical stage, the initial VL, and the other polymorphisms provided similar results for A71V/T. The association between baseline L10I/V and a poorer response was significant at month 6 (slope, 2.83 ± 0.95; P = 0.018), month 9 (slope, 1.77 ± 0.72; P = 0.030), and month 15 (slope, 1.88 ± 0.79; P = 0.044) in the multivariate model restricted for A71V/T. In the RTV arm, a poorer outcome was significantly associated with E35D at months 9 to 12 and 18 to 24 in crude analysis, at months 12, 18, and 24 in analyses adjusted for confounders and other polymorphisms (Table 5), and even at month 21 if L10I/V was excluded (slope, 1.47 ± 0.51; P = 0.016). No patient with E35D was initially treated with SQV.

The baseline distribution of NRTI-experienced patients did not differ between groups defined by relevant polymorphisms: high (3 NRTI-experienced patients out of a total of 7), versus low number (16 of 33), I93L (5 of 10) versus wild type (14 of 30), A71V/T (2 of 5) versus wild-type (17 of 35), L10I/V (2 of 5) versus wild-type (17 of 35).

DISCUSSION

A retrospective analysis of clinical isolates from 116 protease inhibitor-naïve individuals using population-based sequencing approaches reveals a high degree of genetic variability in the HIV protease gene. These findings are in agreement with those of previous studies (1, 2, 13, 24). Some of the strains show amino acid substitutions similar to those of the so-called secondary resistance mutations. They might contribute to resistance and/or maintenance of viral fitness once primary resistance mutations occur; this has been referred to as “genetic background effect” (21). This genetic variability represents naturally occurring substitutions, so-called polymorphisms, as their prevalences did not change in the pre- or post-protease inhibitor periods.

This study provides evidence suggesting that response to triple-drug therapy including a protease inhibitor (IDV, RTV, or SQV) is associated with the overall number of baseline polymorphisms. This association is independent of other predictors of poorer response (14), such as the presence of clinical AIDS at the initiation of therapy and the use of first-line SQV hard gel. However, polymorphisms as predictors are not completely independent of each other. NRTI history appears in some larger studies (14), but not in all (16), as a predictor of poorer response, indicating that our study might not be discriminating enough to display the significance of NRTI history. In addition, although our experienced patients generally have a more advanced immunodeficiency at baseline, they do not show a higher proportion of clinical AIDS, which is a stronger predictor than low levels of CD4+ cells. Furthermore, NRTI history is well distributed between the groups defined by relevant polymorphisms, allowing exclusion of this factor as a possible missing confounder. To our knowledge, a few other published studies have addressed polymorphisms and virological response. In a study with a shorter follow-up, no association was found (2). In our study, most specific polymorphisms could not be firmly identified as contributors to a poorer response. Although I93L, occurring in about 30% of untreated patients, may play a role, as already suggested for IDV-treated patients (P. S. Eastman, C. Gee, R. Dewar, G. Fyfe, J. Metcalf, J. Kolberg, M. Urdea, H. C. Lane, and J. Falloon. Abstr. Fifth Workshop HIV Drug Resist., abstr. 34, 1996). In another study, I93L was believed to belong to the RTV resistance pattern (23). After a first viral rebound, I93L might also be associated with a poorer response, possibly mediated by cross-resistance. In our study A71V/T may possibly play a role in first-line RTV-treated patients. Previous studies (4, 5, 17, 23) had linked A71V/T to the RTV and IDV resistance patterns. No firm conclusions can be drawn for the L10I/V and E35D polymorphisms. E35D might be associated with a poorer outcome in RTV-treated patients, but this slight relationship is confounded by the interactions of other polymorphisms. Reports have included L10I/V in the mutational resistance pattern for IDV (4, 5) and L10I in that for RTV (23). In a statistical comparison of sequences obtained before and after protease inhibitors therapy, Shafer et al. showed that substitutions associated with resistance could include locations 35 and 93 (24). In patients mostly pretreated with a protease inhibitor, Harrigan et al. (8) showed that mutations at codons 10, 63, 71, 77, and 93 are often associated with a poor response to the combination of RTV and SQV. These mutation were attributed to selection through previous protease inhibitor treatment.

L63P is believed to confer IDV resistance in the presence of other substitutions (5) and to compensate for the deleterious effect on viral fitness conferred by the primary resistance mutations (15). Nevertheless, its presence as a polymorphism is not statistically associated with a poorer outcome in our study, in agreement with the findings of a previous report (2), possibly because of its high prevalence.

Our study obviously has several limitations. In general, studies based on data recorded in the past, even if adjusted for confounding factors, are less accurate than randomized trials, notably because of the lack of compliance and drug monitoring data. Certain associations in the statistical analysis are not strong enough to draw any firm conclusions. A larger sample size would allow analysis of polymorphisms with lower prevalence or weaker associations.

The present study reveals a high degree of genetic variability in the clade B HIV protease gene and provides evidence suggesting that treatment response is associated with the overall number of baseline polymorphisms, the so-called protease genetic background. While most of the specific contributors could not be firmly identified, substitutions I93L and possibly A71V/T may play a role. This has to be confirmed in larger cohorts of patients. Longitudinally assessing resistance in patients under protease inhibitor treatment is also warranted. Interactions between primary resistance mutations and background polymorphisms would be better understood if molecular and biochemical mechanisms of evolutionary patterns were known. In addition, more-sensitive genotypic tests would assess if smaller populations of polymorphisms located at the active site could be detected. Finally, similar studies should be done with patients receiving newly approved protease inhibitors (e.g., amprenavir, ABT-378) and with patients infected with non-clade B virus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Fondation Recherche sur le SIDA, Luxembourg, the Centre de Recherche Public-Santé (CRP-Santé), Luxembourg, and a GlaxoWellcome grant awarded through the Belgian Society of Infectiology and Clinical Microbiology in 1999. J.S. benefits from a Bourse-Formation Recherche (BFR97/015), Ministère de la Culture, de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, Luxembourg (1997-2000).

REFERENCES

- 1.Birk M, Sönnerborg A. Variations in HIV-1 pol gene associated with reduced sensitivity to antiretroviral drugs in treatment-naive patients. AIDS. 1998;12:2369–2375. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199818000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bossi P, Mouroux M, Yvon A, Bricaire F, Agut H, Huraux J-M, Katlama C, Calvez V. Polymorphism of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease gene and response of HIV-1-infected patients to a protease inhibitor. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2910–2912. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2910-2912.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1992;41(RR-17):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Condra J H, Holder D J, Schleif W A, Blahy O M, Danovich R M, Gabryelski L J, Graham D J, Laird D, Quintero J C, Rhodes A, Robbins H L, Roth E, Shivaprakash M, Yang T, Chodakewitz J A, Deutsch P J, Leavitt R Y, Massari F E, Mellors J W, Squires K E, Steigbigel R T, Teppler H, Emini E A. Genetic correlates of in vivo viral resistance to indinavir, a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor. J Virol. 1996;70:8270–8276. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8270-8276.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Condra J H, Schleif W A, Blahy O M, Gabryelski L J, Graham D J, Quintero J C, Rhodes A, Robbins H L, Roth E, Shivaprakash M, Titus D, Yang T, Teppler H, Squires K E, Deutsch P J, Emini E A. In vivo emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to multiple protease inhibitors. Nature. 1995;374:569–571. doi: 10.1038/374569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox D R. Regression models and life-tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gulick R M, Mellors J W, Havlir D, Eron J J, Gonzalez C, McMahon D, Jonas L, Meibohm A, Holder D, Schleif W A, Condra J H, Emini E A, Isaacs R, Chodakewitz J A, Richman D D. Simultaneous vs sequential initiation of therapy with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine for HIV-1 infection: 100-week follow-up. JAMA. 1998;280:35–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrigan P R, Hertogs K, Verbiest W, Pauwels R, Larder B, Kemp S, Bloor S, Yip B, Hogg R, Alexander C, Montaner J S G. Baseline HIV drug resistance profile predicts response to ritonavir/saquinavir protease inhibitor therapy in a community setting. AIDS. 1999;13:1863–1871. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hecht F M, Grant R M, Petropoulos C J, Dillon B, Chesney M A, Tian H, Hellmann N S, Bandrapalli N I, Digilio L, Branson B, Kahn J O. Sexual transmission of an HIV-1 variant resistant to multiple reverse-transcriptase and protease inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:341–343. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch M S, Brun-Vézinet F, D'Aquila R T, Hammer S M, Johnson V A, Kuritzkes D R, Loveday C, Mellors J W, Clotet B, Conway B, Demeter L, Vella S, Jacobsen D M, Richman D D. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adult HIV-1 infection: recommendations of an International AIDS Society— USA panel. JAMA. 2000;283:2417–2426. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.18.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho D D, Neumann A U, Perelson A S, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphoctytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho D D, Toyoshima T, Mo H, Kempf D J, Norbeck D, Chen C M, Wideburg N E, Burt S K, Erickson J W, Singh M K. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants with increased resistance to a C2-symmetric protease inhibitor. J Virol. 1994;68:2016–2020. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.2016-2020.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozal M J, Shah N, Shen N, Yang R, Fucini R, Merigan T C, Richman D D, Morris D, Hubbell E, Chee M, Gingeras T R. Extensive polymorphisms observed in HIV-1 clade B protease gene using high-density oligonucleotide arrays. Nat Med. 1996;2:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledergerber B, Egger M, Opravil M, Telenti A, Hirschel B, Battegay M, Vernazza P, Sudre P, Flepp M, Furrer H, Francioli P, Weber R. Clinical progression and virological failure on highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 patients: a prospective cohort study. Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Lancet. 1999;353:863–868. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Picado J, Savara A V, Sutton L, D'Aquilla R T. Replicative fitness of protease inhibitor-resistant mutants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1999;73:3744–3752. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3744-3752.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mocroft A, Gill M J, Davidson W, Phillips A N. Predictors of a viral response and subsequent virological treatment failure in patients with HIV starting a protease inhibitor. AIDS. 1998;12:2161–2167. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199816000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molla A, Korneyeva M, Gao Q, Vasavanonda S, Schipper P J, Mo H M, Markowitz M, Chernyavskiy T, Niu P, Lyons N, Hsu A, Granneman G R, Ho D D, Boucher C A B, Leonard J M, Norbeck D W, Kempf D J. Ordered accumulation of mutations in HIV protease confers resistance to ritonavir. Nat Med. 1996;2:760–766. doi: 10.1038/nm0796-760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mouton Y, Alfandari S, Valette M, Cartier F, Dellamonica P, Humbert G, Lang J M, Massip P, Mechali D, Leclercq P, Modai J, Portier H. Impact of protease inhibitors on AIDS-defining events and hospitalizations in 10 French AIDS reference centres. Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte contre le SIDA. AIDS. 1997;11:F101–F105. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers G, Korber B, Hahn B H. Human retroviruses and AIDS: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N. Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peng C, Ho B K, Chang T W, Chang N T. Role of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific protease in core protein maturation and viral infectivity. J Virol. 1989;63:2550–2556. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2550-2556.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose R E, Gong Y F, Greytok J A. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral background plays a major role in development of resistance to protease inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1648–1653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schinazi R F, Larder B A, Mellors J W. Mutations in retroviral genes associated with drug resistance: 2000–2001 update. Int Antivir News. 2000;8(5):65–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmit J C, Ruiz L, Clotet B, Raventos A, Tor J, Leonard J, Desmyter J, DeClercq E, Vandamme A M. Resistance-related mutations in the HIV-1 protease gene of patients treated for 1 year with the protease inhibitor ritonavir (ABT-538) AIDS. 1996;10:995–999. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610090-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shafer R W, Hsu P, Patick A K, Craig C, Brendel V. Identification of biased amino acid substitution patterns in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from patients treated with protease inhibitors. J Virol. 1999;73:6197–6202. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6197-6202.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandamme A M, Witvrouw M, Pannecouque C, Balzarini J, VanLaethem K, Schmit J C, Desmyter J, DeClercq E. Evaluating clinical isolates for their phenotypic and genotypic resistance against anti-HIV drugs. Methods Mol Med. 1999;24:223–258. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-245-7:223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]