Abstract

Bacterial resistance to antibiotics is an ever-growing problem in heathcare. We have previously identified a set of osmium(II), ruthenium(II), iridium(III) and rhodium(III) half-sandwich type complexes with bidentate monosaccharide ligands possessing cytostatic properties against carcinoma, lymphoma and sarcoma cells with low micromolar or submicromolar IC50 values. Importantly, these complexes were not active on primary, non-transformed cells. These complexes have now been assessed as to their antimicrobial properties and found to be potent inhibitors of the growth of reference strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis (Gram-positive species), though the compounds proved inactive on reference strains of Pseudomonas aerugonisa, Escherichia coli, Candida albicans, Candida auris and Acinetobacter baumannii (Gram-negative species and fungi). Furthermore, clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus sp. (both multiresistant and susceptible strains) were also susceptible to the organometallic complexes in this study with similar MIC values as the reference strains. Taken together, we identified a set of osmium(II), ruthenium(II), iridium(III) and rhodium(III) half-sandwich type antineoplastic organometallic complexes which also have antimicrobial activity among Gram-positive bacteria. These compounds represent a novel class of antimicrobial agents that are not detoxified by multiresistant bacteria suggesting a potential to be used to combat multiresistant infections.

Keywords: platinum-group metal complexes, half-sandwich, glycosyl heterocycle, oxadiazole, triazole, gram positive, MRSA, VRE

Introduction

Bacterial resistance to registered antibiotics is one of the biggest challenges of mankind (Hernando-Amado et al., 2019; Murray et al., 2022) that begs for the discovery of novel antibacterial compounds. There are multiple examples of antibacterial agents that were repurposed as anticancer drugs [e.g., Methenamine (Altinoz et al., 2019)], or anticancer medications being repurposed as antibacterial ones, such as platinum(II) remedies. Indeed, cisplatin and carboplatin do have bacteriostatic properties on Acinetobacter, Mycobacteria, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Zhang et al., 2011; McCarron et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2018) and other pathogens (Hummell and Kirienko, 2020). To complement the registered platinum-based anticancer agents, there is a thrust towards identifying novel complexes of transition metals with anticancer activity (Kenny and Marmion, 2019). Ruthenium complexes have emerged as anticancer agents, characterized by low toxicity (Melchart and Sadler, 2006; Mello-Andrade et al., 2018; Gano et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Mihajlovic et al., 2020), good cellular entry properties (Graf and Lippard, 2012; Yadav et al., 2013) and with excellent targetability (Berger et al., 2008; Hanif et al., 2013; Florindo et al., 2014; Zeng et al., 2017; Kenny and Marmion, 2019; Hamala et al., 2020). In fact, a ruthenium complex, IT-139 has passed clinical phase I to be applied in colorectal cancer (Burris et al., 2016). Furthermore, rhodium (Leung et al., 2013; Gichumbi and Friedrich, 2018; Štarha and Trávníček, 2019; Máliková et al., 2021), osmium (Hartinger et al., 2011; Hanif et al., 2014; Gichumbi and Friedrich, 2018; Konkankit et al., 2018; Meier-Menches et al., 2018; Štarha and Trávníček, 2019; Nabiyeva et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021) and iridium (Leung et al., 2013; Liu and Sadler, 2014; Gichumbi and Friedrich, 2018; Konkankit et al., 2018; Štarha and Trávníček, 2019; Li et al., 2021) compounds were also described as anticancer agent candidates.

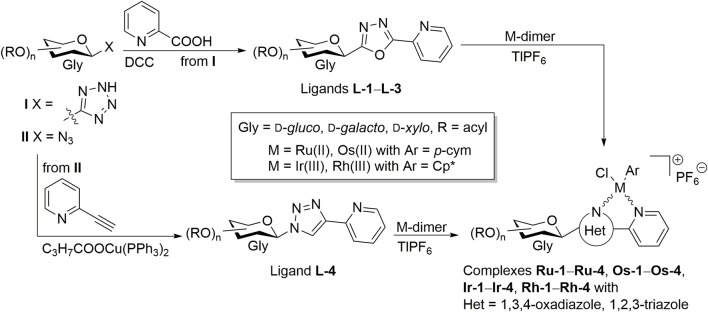

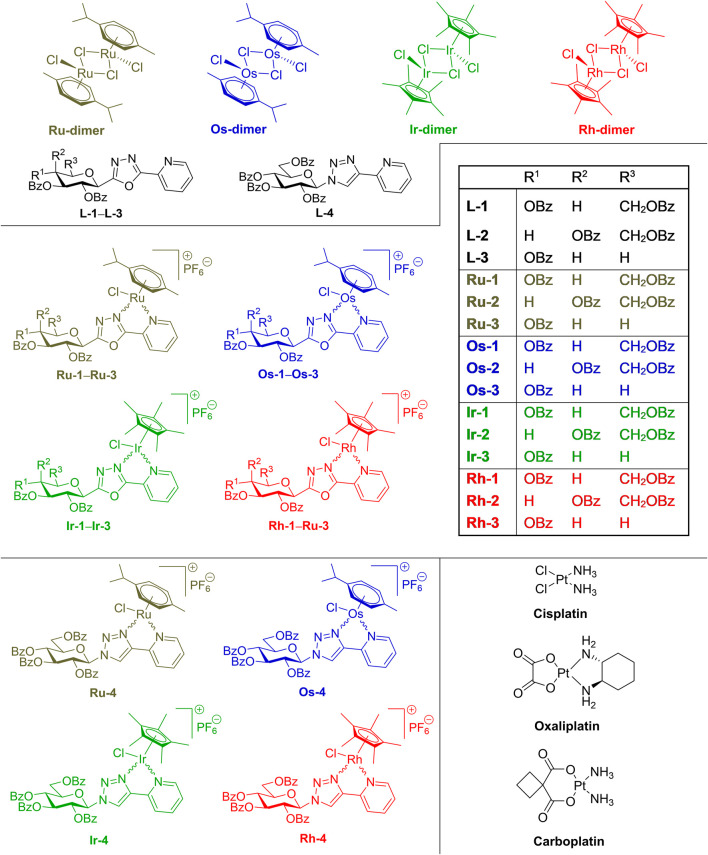

We synthesized a set of half-sandwich complexes of ruthenium(II), osmium(II), iridium(III) and rhodium(III) incorporating real C- and N-glycopyranosyl azole type N,N-bidentate ligands (Figure 1) (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022). To get the 1,3,4-oxadiazole type L-1–L-3 ring-transformation of C-glycosyl tetrazoles I with picolinic acid was performed (Bokor et al., 2017), while for 1,2,3-triazole-based chelator L-4 copper(I) catalyzed azide alkyne cycloadditon (CuAAc) (Agrahari et al., 2021) of glucosyl azide II was used. The ligands were reacted with dimeric chloro-bridged platinum-group metal complexes in the presence of TlPF6 to result in complexes Ru-1‒Ru-4, Os-1‒Os-4, Ir-1‒Ir-4 and Rh-1‒Rh-4 (Figures 1, 2). These complexes were identified to show cytostatic properties on carcinomas (representative data listed in Table 1), sarcomas and lymphomas in the low micromolar or submicromolar range, but have no bioactivity on primary, non-transformed fibroblasts (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022). The compounds exert their cytostatic activity through inducing oxidative stress (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022). The cytostatic activity of the compounds can be alleviated by vitamin E, an apolar, membrane antioxidant (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022) suggesting that the compounds likely target the cell membrane or other apolar compartments in the cells. On the analogy of the bacteriotoxic activity of platinum or palladium compounds (Quirante et al., 2011; Vieites et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; McCarron et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2018; Hummell and Kirienko, 2020; Yufanyi et al., 2020; Frei et al., 2021; Mansour, 2021) we set out to assess whether the above cytostatic complexes Ru-1‒Ru-4, Os-1‒Os-4, Ir-1‒Ir-4 and Rh-1‒Rh-4 in Figure 2 (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022), might have bacteriostatic properties. For comparative studies, the precursors of these complexes (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022), such as the chloro-bridged platinum-metal dimeric complexes (Ru-dimer, Os-dimer, Ir-dimer and Rh-dimer) and the glycosyl heterocyclic N,N-bidentate ligands (L-1‒L-4), as well as, the reference platinum-based anticancer drugs (cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin) were also planned to be tested (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Outline of the syntheses of the compounds to be tested in this study (the precise structures of the compounds are shown in Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Selected compounds to be tested for antimicrobial activity.

TABLE 1.

The IC50 values [(µM)] of the selected compounds on A2780 ovarian cancer cells in (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022).

| L-1 | L-2 | L-3 | L-4 | Ru-Dimer | Os-Dimer | Ir-Dimer | Rh-Dimer |

| ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Ru-1 | Ru-2 | Ru-3 | Ru-4 | Os-1 | Os-2 | Os-3 | Os-4 |

| 6.2 | 4.3 | 8.5 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 0.7 |

| Ir-1 | Ir-2 | Ir-3 | Ir-4 | Rh-1 | Rh-2 | Rh-3 | Rh-4 |

| ND | ND | ND | 1.6 | ND | ND | ND | 25.3 |

| Cisplatin | Oxaliplatin | Carboplatin | ND: no effect | ||||

| 1.2 | 0.1 | 28.0 | |||||

Materials and Methods

Chemical Compounds

All compounds (including cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States). Ligands L-1‒L-4, complexes Ru-1‒Ru-4, Os-1‒Os-4, Ir-1‒Ir-4, Rh-1‒Rh-4 were published in (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022). The Os-dimer was published in (Godó et al., 2012), Ru-dimer was from Strem Chemicals (Newburyport, MA, United States), Ir-dimer was from Acros Organics (Gael, Belgium) and the Rh-dimer was from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, United States). Compounds were dissolved in DMSO. In experiments the highest DMSO concentration was 0.04%, therefore, control cells were treated with 0.04% DMSO.

Synthesis of the Compounds Tested

Synthesis and assessment of structural integrity of the sugar-based compounds (L-1‒L-4, Ru-1‒Ru-4, Os-1‒Os-4, Ir-1‒Ir-4, Rh-1‒Rh-4 used in the manuscript (Figures 1, 2) were described in (Kacsir et al., 2021) and (Kacsir et al., 2022).

Reference Strains

For testing we used the following reference strains: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC27853), Escherichia coli (ATCC25922), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC11007), Candida albicans (SC5314), Candida auris (ATCC21092) and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC29112). All were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, United States).

Clinical Isolates of S. aureus and E. Faecium

We used a set of clinical isloates of S. aureus and E. faecium that were collected at the Medical Center of the University of Debrecen (Hungary) between 01.01.2018. ‒ 31.12.2020. (Table 2). We also included a multiresistant clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii. These were identified using a Microflex MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, United States). Antibiotic susceptibility of the isolates was tested following the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, 2021) guidelines valid at the time of collection.

TABLE 2.

Clinical isolates used in the study: MSSA–methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA–methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, VSE–vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus, VRE - vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.

| Species | Year | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20276 | S. aureus | MSSA | 2018 | Wound |

| 20478 | S. aureus | MSSA | 2018 | Bronchial |

| 20559 | S. aureus | MSSA | 2018 | Wound |

| 20627 | S. aureus | MSSA | 2018 | Ear |

| 20650 | S. aureus | MSSA | 2018 | Nasal |

| 20904 | S. aureus | MSSA | 2018 | Abscess |

| 20426 | S. aureus | MRSA | 2020 | Blood |

| 24035 | S. aureus | MRSA | 2018 | Wound |

| 24268 | S. aureus | MRSA | 2018 | Throat |

| 24272 | S. aureus | MRSA | 2018 | Throat |

| 24328 | S. aureus | MRSA | 2018 | Throat |

| 24408 | S. aureus | MRSA | 2018 | Bronchial |

| 28046 | E. faecium | VSE | 2021 | Abdominal |

| 28386 | E. faecium | VSE | 2021 | Urine |

| 25051 | E. faecium | VRE | 2018 | Nephrostoma |

| 25342 | E. faecium | VRE | 2021 | Urine |

| 25498 | E. faecium | VRE | 2018 | Rectal swab for screening for multiresistant pathogens |

| 27085 | E. faecium | VRE | 2018 | Wound |

| 28209 | E. faecium | VRE | 2021 | Urine |

| 28085 | E. faecium | VRE | 2021 | Urine |

Broth Microdilution

Microdilution experiments were performed according to the standards of EUCAST (EUCAST, 2021). The bacterial isolates to be tested were grown in Mueller-Hinton broth. Candida species were grown in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) -1,640 medium. Inoculum density of bacteria or fungi was set at 5.0 × 105 CFU/ml in microtiter plates in a final volume of 200 µl Mueller-Hinton broth (for bacteria) or in RPMI (for fungi). Tested concentration range was 0.08–40 µM (10 concentrations, two-fold serial dilutions), drug-free growth control and inoculum-free negative control were included. The inoculated plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C then were assessed visually. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration with 50% ≤ inhibitory effect. All experiments were performed at least twice in duplicates.

Results

The Complexes Can Inhibit the Growth of Gram-Positive Bacteria

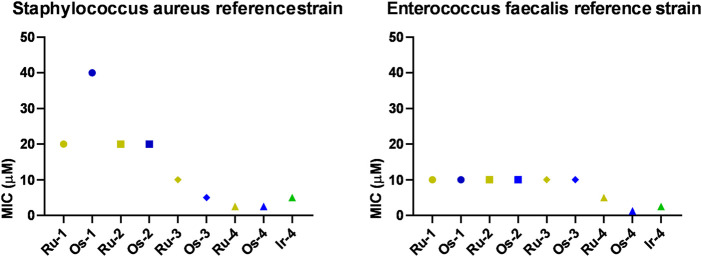

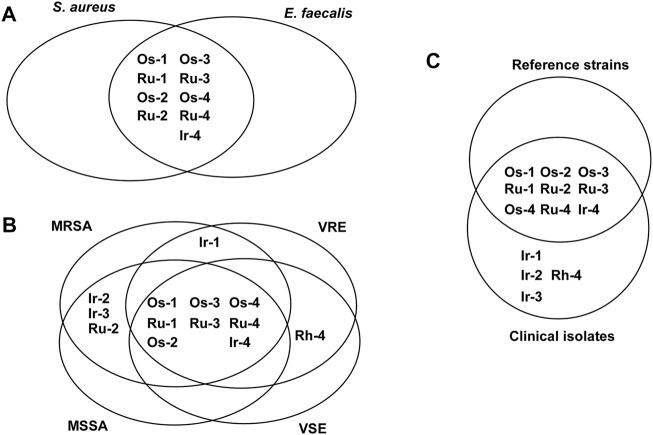

First, we tested the ruthenium(II), osmium(II), iridium(III) and rhodium(III) complexes (Ru-1‒Ru-4, Os-1‒Os-4, Ir-1‒Ir-4, Rh-1‒Rh-4; Figure 2) identified in the studies by Kacsir et al. (2021); Kacsir et al., 2022). These compounds were not active on the reference strains of Gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aerugonisa (ATCC27853), Escherichia coli (ATCC25922), or a clinical isolate of Acinetobacter baumannii, nor on fungi as Candida albicans (SC5314) and Candida auris (ATCC21092). Nevertheless, the Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC11007) and Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC29112) were susceptible to Ru-1, Os-1, Ru-2, Os-2, Ru-3, Os-3, Ru-4, Os-4 and Ir-4, the best being osmium and ruthenium complexes and the complexes of the free ligand L-4 (Figure 3). Cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin were included in the study as controls, as they were reported to have antibacterial activity (Zhang et al., 2011; McCarron et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2018; Hummell and Kirienko, 2020). Cisplatin inhibited the growth of P. aurigenosa at a high MIC value of 40 μM, carboplatin and oxaliplatin had no effect suggesting that the effects of platinum complexes were fundamentally different from that of the organometallic bidentate complexes. Neither the free ligands (L-1‒L-4), the Ru(II)/Os(II) hexahapto p-cymene dimer (Ru-dimer and Os-dimer), or the Rh(III)/Ir(III) pentahapto arenyl dimer (Ir-dimer and Rh-dimer), Ir-1‒Ir-3 and Rh-1‒Rh-4 complexes had any bacteriostatic activity.

FIGURE 3.

The effects of the complexes on the reference strains of S. aureus (ATCC11007) and E. faecalis (ATCC29112). Bacterial reference strains were subjected to microdilution assays (repeated at least twice in duplicates) as described in Materials and Methods.

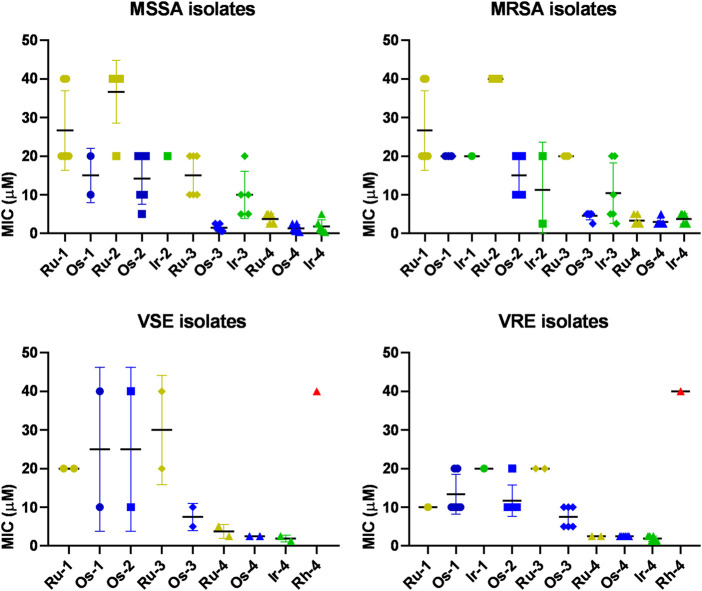

Complexes Are Active on Multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus isolates

Subsequently, we assessed whether the compounds were active on the clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus [6 methicillin susceptible (MSSA) and six methicillin resistant (MRSA)] and Enterococcus sp [2 vancomycin susceptible (VSE) and six vancomycin resistant (VRE)] (Figure 4; Tables 3, 4, 5, 6). MSSA, MRSA, VSE and VRE growth was inhibited by the complexes Os-2‒Os-4 and Ir-4 in all isolates (Figures 4, 5; Tables 3, 4, 5, 6). Ir-1‒Ir-3, Ru-1‒Ru-4 and Os-1 were active only on a subset of isolates (Figures 4, 5; Tables 3, 4, 5, 6). The best activity was observed for the osmium, ruthenium and iridium complexes of L-4 (Os-4, Ru-4, Ir-4) showing MIC values in the low micromolar range (MIC<10 µM) and being active on most or all clinical isolates tested, as well as, on the reference strains (Figures 3, 4; Tables 3, 4, 5, 6). Rh-4 was active only on Enterococcus isolates (both VSE and VRE), but not on MSSA or MRSA isolates (Figures 4, 5; Tables 3, 4, 5, 6). Rh-1‒Rh-3 complexes were inactive (Figures 4, 5; Tables 3, 4, 5, 6).

FIGURE 4.

The effects of the complexes on clinical isolates of S. aureus and E. faecium. MICs were determined by microdilution assays (repeated at least twice in duplicates) as described in Materials and Methods. Abbreviations: MSSA–methicyllin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA–methicyllin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, VSE–vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus, VRE–vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus.

TABLE 3.

MIC values [(µM)] of the complexes against MSSA isolates.

| Strain | Ru-1 | Os-1 | Ru-2 | Os-2 | Ir-2 | Ru-3 | Os-3 | Ir-3 | Ru-4 | Os-4 | Ir-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20627 | 20 | >40 | 40 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 1.25 | 5 | 2.50 | 0.3 | 0.60 |

| 20559 | 20 | >40 | 40 | 20 | >40 | 10 | 0.60 | 10 | 5 | 0.60 | 1.25 |

| 20650 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 20 | >40 | 20 | 0.60 | 5 | 5 | 0.60 | 0.30 |

| 20904 | 40 | >40 | 40 | 20 | >40 | 20 | 2.50 | >40 | 5 | 2.5 | 5 |

| 20276 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 5 | >40 | 10 | 1.25 | 10 | 2.50 | 1.25 | 1.25 |

| 20478 | 20 | >40 | 40 | 10 | >40 | 10 | 2.50 | 20 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

TABLE 4.

MIC values [(µM)] of the complexes against MRSA isolates.

| Strain | Ru-1 | Os-1 | Ir-1 | Ru-2 | Os-2 | Ir-2 | Ru-3 | Os-3 | Ir-3 | Ru-4 | Os-4 | Ir-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20426 | 40 | 20 | >40 | 40 | 20 | >40 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 2.50 | 5 | 5 |

| 24408 | 20 | >40 | >40 | 40 | 10 | 2.5 | 20 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| 24268 | 40 | 20 | 20 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| 20328 | 20 | >40 | >40 | 40 | 20 | >40 | 20 | 5 | 20 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 5 |

| 24272 | 20 | 20 | >40 | >40 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| 24035 | 20 | >40 | >40 | 40 | 10 | >40 | 20 | 5 | 20 | 5 | 2.50 | 5 |

TABLE 5.

MIC values [(µM)] of the complexes against VSE isolates.

| Strain | Ru-1 | Os-1 | Os-2 | Ru-3 | Os-3 | Ru-4 | Os-4 | Ir-4 | Rh-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28386 | 20 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 5 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 1.25 | 40 |

| 28046 | 20 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 10 | 5 | 2.50 | 2.50 | >40 |

TABLE 6.

MIC values [(µM)] of the complexes against VRE isolates.

| Strain | Ru-1 | Os-1 | Ir-1 | Os-2 | Ru-3 | Os-3 | Ru-4 | Os-4 | Ir-4 | Rh-4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25051 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 2.50 | 1.25 | >40 |

| 25085 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 2.50 | 1.25 | >40 |

| 25498 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 10 | >40 | 5 | >40 | 2.50 | 2.50 | >40 |

| 25342 | >40 | 20 | >40 | 20 | >40 | 5 | >40 | 2.50 | 2.50 | >40 |

| 28209 | >40 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 5 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 40 |

| 28085 | 10 | 10 | >40 | 10 | 20 | 10 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 1.25 | >40 |

FIGURE 5.

Effects of the complexes on the reference strains and clinical isolates.

Discussion

We assessed a set of half-sandwich type ruthenium(II), osmium(II), rhodium(III) and iridium(III) complexes of monosaccharide derivatives bearing bidentate N,N-chelating sets. The compounds discussed in the study and compounds with similar structure were identified earlier as anticancer agents (Florindo et al., 2014; Florindo et al., 2015; Florindo et al., 2016; Hamala et al., 2020; Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022). From the perspective of the current study it is important to note that the complexes were not active on primary human fibroblasts up to 33.3 µM (i.e., their IC50 values were higher than 33.3 µM), but only had activity on neoplastic cell lines in low micromolar to submicromolar range (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022) and here we show that these compounds have antimicrobial effects. These suggest that the complexes would be selective towards bacteria and neoplastic cells, which may be an advantageous feature in a clinical setting. The type of the central metal ion and the ligands, the stability and kinetic behavior as well as hydrolytic properties and the lipophilicity of a complex contribute significantly to its biological activity.

With respect to the central metal ion of the complex, osmium compounds were the most efficient on bacteria, followed by ruthenium complexes both in terms of the number of active complexes, as well as, their MIC values, while the iridium and rhodium complexes showed less activity. These findings are similar to our data on cancer cells (Kacsir et al., 2022). In other words, when comparing the Ru(II) and Os(II) complexes with hexahapto p-cymene ligand to the pentahapto arenyl-containing Ir(III) and Rh(III) complexes, the former ones were found to show better activity. There are multiple chemical features that can explain this finding. For the mentioned two pairs of metal ions in Ru and Os complexes, the hexahapto coordinated p-cym ligand provides less electron densitiy than the Cp* arenyl in the corresponding Rh or Ir compounds and their steric hindrance is different. Kinetic differences may also provide an explanation, as it is widely accepted that the half-sandwich type Os and Ir complexes, in general, exhibit much lower ligand exchange rates than the Ru and Rh analogues (Bruijnincx and Sadler, 2009). When comparing the IC50 values for cancer cells with the MIC values against bacteria, it is apparent that the MIC values of the active complexes are higher than their IC50 values on the most sensitive cancer cell model [e.g., for Os-4 IC50 = 0.7 µM on 2780 ovarian cancer cells (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022) vs. MIC range = 0.3–5 µM on multiresistant bacteria]. When comparing the MIC values of the complexes we found similar trends as a function of the central metal ion or the ligand as the IC50 values of the complexes on cancer cells. Complexes of L-4 were considerably more effective than complexes of L-3, L-2 or L-1. These findings are also in good correlation with our observations on cancer cells (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022) and may support the importance of the high hydrophobicity of the complexes. Importantly, for the complexes with good bacteriostatic activity (e.g., Os-4) there was no difference in the MIC value on the reference strains, the susceptible (MSSA, VSE) or the multiresistant isolates (MRSA, VRE). The activity of the complexes in previous antineoplastic studies was dependent on the apolar character of the compounds (Kacsir et al., 2021; Kacsir et al., 2022). We provided experimental evidence the carbohydrate moiety has a key role in bringing about the apolar character of the molecules by harboring multiple OBz groups. The replacement of the carbohydrate moiety with one single aromatic group largely hampered or eliminated the biological activity of the complexes (Kacsir et al., 2021). Therefore, the complexes supposedly affect the cell membrane that may be the case in bacteria as well. It is also of note that the exact target of the complexes has not been identified yet. Taken together, we identified osmium, ruthenium, iridium and rhodium complexes that exhibit antibacterial effects. The complexes have multiple advantageous properties, they are stable over extended periods [2 days were assessed in (Kacsir et al., 2021)], their MIC and IC50 values are in the low micromolar or submicromolar range, respectively, and they are not active on non-transformed cells. As noted earlier, the active complexes have similar MIC values against multiresistant clinical isolates of MRSA and VRE and on sensitive isolates or reference strains suggesting a novel, yet unidentified target in Gram-positive bacteria that is not detoxified by existing resistance mechanisms. These findings suggest that the complexes studied here and similar ones may represent a novel class of antibiotics against multiresistant Gram-positive bacteria.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

BB, ZT and AS performed experiments, IK synthesized the compounds, PBu, LS, ÉB, GK and PBa conceptualized and supervised research, wrote the paper and contributed to the manuscript editing.

Funding

Our work was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office of Hungary (grants K123975 and FK125067), the University of Debrecen and by the Thematic Excellence Programme (TKP2021-EGA-19 and TKP2021-EGA-20) of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology in Hungary.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Agrahari A. K., Bose P., Jaiswal M. K., Rajkhowa S., Singh A. S., Hotha S., et al. (2021). Cu(I)-Catalyzed Click Chemistry in Glycoscience and Their Diverse Applications. Chem. Rev. 121 (13), 7638–7956. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altinoz M. A., Ozpinar A., Ozpinar A., Perez J. L., Elmaci İ. (2019). Methenamine's Journey of 160 years: Repurposal of an Old Urinary Antiseptic for Treatment and Hypoxic Radiosensitization of Cancers and Glioblastoma. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 46 (5), 407–412. 10.1111/1440-1681.13070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger I., Hanif M., Nazarov A. A., Hartinger C. G., John R. O., Kuznetsov M. L., et al. (2008). In Vitro Anticancer Activity and Biologically Relevant Metabolization of Organometallic Ruthenium Complexes with Carbohydrate-Based Ligands. Chem. Eur. J. 14 (29), 9046–9057. 10.1002/chem.200801032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokor É., Kun S., Goyard D., Tóth M., Praly J.-P., Vidal S., et al. (2017). C-glycopyranosyl Arenes and Hetarenes: Synthetic Methods and Bioactivity Focused on Antidiabetic Potential. Chem. Rev. 117 (3), 1687–1764. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnincx P. C. A., Sadler P. J. (2009). Controlling Platinum, Ruthenium, and Osmium Reactivity for Anticancer Drug Design. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 61, 1–62. 10.1016/S0898-8838(09)00201-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris H. A., Bakewell S., Bendell J. C., Infante J., Jones S. F., Spigel D. R., et al. (2016). Safety and Activity of IT-139, a Ruthenium-Based Compound, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumours: a First-In-Human, Open-Label, Dose-Escalation Phase I Study with Expansion Cohort. ESMO Open 1 (6), e000154. 10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST (2021). MIC Determination of Non-fastidious and Fastidious Organisms. [Online]. Availavle at: https://www.eucast.org/ast_of_bacteria/mic_determination/?no_cache=1 (Accessed 202111, , 04).

- Florindo P., Marques I. J., Nunes C. D., Fernandes A. C. (2014). Synthesis, Characterization and Cytotoxicity of Cyclopentadienyl Ruthenium(II) Complexes Containing Carbohydrate-Derived Ligands. J. Organomet. Chem. 760, 240–247. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2013.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florindo P. R., Pereira D. M., Borralho P. M., Costa P. J., Piedade M. F. M., Rodrigues C. M. P., et al. (2016). New [(η5-C5H5)Ru(N-N)(PPh3)][PF6] Compounds: colon Anticancer Activity and GLUT-Mediated Cellular Uptake of Carbohydrate-Appended Complexes. Dalton Trans. 45 (30), 11926–11930. 10.1039/c6dt01571a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florindo P. R., Pereira D. M., Borralho P. M., Rodrigues C. M. P., Piedade M. F. M., Fernandes A. C. (2015). Cyclopentadienyl-Ruthenium(II) and Iron(II) Organometallic Compounds with Carbohydrate Derivative Ligands as Good Colorectal Anticancer Agents. J. Med. Chem. 58 (10), 4339–4347. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei A., Ramu S., Lowe G. J., Dinh H., Semenec L., Elliott A. G., et al. (2021). Platinum Cyclooctadiene Complexes with Activity against Gram‐positive Bacteria. ChemMedChem 16 (20), 3165–3171. 10.1002/cmdc.202100157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gano L., Pinheiro T., Matos A. P., Tortosa F., Jorge T. F., Gonçalves M. S., et al. (2019). Antitumour and Toxicity Evaluation of a Ru(II)-Cyclopentadienyl Complex in a Prostate Cancer Model by Imaging Tools. Acamc 19 (10), 1262–1275. 10.2174/1871520619666190318152726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- G. Hartinger C., D. Phillips A., A. Nazarov A. (2011). Polynuclear Ruthenium, Osmium and Gold Complexes. The Quest for Innovative Anticancer Chemotherapeutics. Ctmc 11 (21), 2688–2702. 10.2174/156802611798040769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gichumbi J. M., Friedrich H. B. (2018). Half-sandwich Complexes of Platinum Group Metals (Ir, Rh, Ru and Os) and Some Recent Biological and Catalytic Applications. J. Organomet. Chem. 866, 123–143. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.04.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godó A. J., Bényei A. C., Duff B., Egan D. A., Buglyó P. (2012). Synthesis and X-ray Diffraction Structures of Novel Half-sandwich Os(II)-and Ru(II)-Hydroxamate Complexes. RSC Adv. 2 (4), 1486–1495. 10.1039/C1RA00998B [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graf N., Lippard S. J. (2012). Redox Activation of Metal-Based Prodrugs as a Strategy for Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64 (11), 993–1004. 10.1016/j.addr.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamala V., Martišová A., Červenková Šťastná L., Karban J., Dančo A., Šimarek A., et al. (2020). Ruthenium Tetrazene Complexes Bearing Glucose Moieties on Their Periphery: Synthesis, Characterization, and In Vitro Cytotoxicity. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 34, e5896. 10.1002/aoc.5896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanif M., Babak M. V., Hartinger C. G. (2014). Development of Anticancer Agents: Wizardry with Osmium. Drug Discov. Today 19 (10), 1640–1648. 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanif M., Meier S. M., Nazarov A. A., Risse J., Legin A., Casini A., et al. (2013). Influence of the π-coordinated Arene on the Anticancer Activity of Ruthenium(II) Carbohydrate Organometallic Complexes. Front. Chem. 1, 27. 10.3389/fchem.2013.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernando-Amado S., Coque T. M., Baquero F., Martínez J. L. (2019). Defining and Combating Antibiotic Resistance from One Health and Global Health Perspectives. Nat. Microbiol. 4 (9), 1432–1442. 10.1038/s41564-019-0503-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummell N. A., Kirienko N. V. (2020). Repurposing Bioactive Compounds for Treating Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens. J. Med. Microbiol. 69 (6), 881–894. 10.1099/jmm.0.001172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacsir I., Sipos A., Bényei A., Janka E., Buglyó P., Somsák L., et al. (2022). Reactive Oxygen Species Production Is Responsible for Antineoplastic Activity of Osmium, Ruthenium, Iridium and Rhodium Half-Sandwich Type Complexes with Bidentate Glycosyl Heterocyclic Ligands in Various Cancer Cell Models. Ijms 23 (2), 813. 10.3390/ijms23020813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacsir I., Sipos A., Ujlaki G., Buglyó P., Somsák L., Bai P., et al. (2021). Ruthenium Half-Sandwich Type Complexes with Bidentate Monosaccharide Ligands Show Antineoplastic Activity in Ovarian Cancer Cell Models through Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Ijms 22 (19), 10454. 10.3390/ijms221910454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny R. G., Marmion C. J. (2019). Toward Multi-Targeted Platinum and Ruthenium Drugs-A New Paradigm in Cancer Drug Treatment Regimens? Chem. Rev. 119 (2), 1058–1137. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkankit C. C., Marker S. C., Knopf K. M., Wilson J. J. (2018). Anticancer Activity of Complexes of the Third Row Transition Metals, Rhenium, Osmium, and Iridium. Dalton Trans. 47 (30), 9934–9974. 10.1039/c8dt01858h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C.-H., Zhong H.-J., Chan D. S.-H., Ma D.-L. (2013). Bioactive Iridium and Rhodium Complexes as Therapeutic Agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 257 (11-12), 1764–1776. 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Liu B., Shi H., Wang Y., Sun Q., Zhang Q. (2021). Metal Complexes against Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Dalton Trans. 50, 14498–14512. 10.1039/d1dt02909f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Lai H., Xiong Z., Chen B., Chen T. (2019). Functionalization and Cancer-Targeting Design of Ruthenium Complexes for Precise Cancer Therapy. Chem. Commun. 55 (67), 9904–9914. 10.1039/c9cc04098f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Sadler P. J. (2014). Organoiridium Complexes: Anticancer Agents and Catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (4), 1174–1185. 10.1021/ar400266c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Máliková K., Masaryk L., Štarha P. (2021). Anticancer Half-Sandwich Rhodium(III) Complexes. Inorganics 9 (4), 26. 10.3390/inorganics9040026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A. M. (2021). Pd(ii) and Pt(ii) Complexes of Tridentate Ligands with Selective Toxicity against Cryptococcus Neoformans and Candida Albicans. RSC Adv. 11 (63), 39748–39757. 10.1039/D1RA06559A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron A. J., Armstrong C., Glynn G., Millar B. C., Rooney P. J., Goldsmith C. E., et al. (2012). Antibacterial Effects on Acinetobacter Species of Commonly Employed Antineoplastic Agents Used in the Treatment of Haematological Malignancies: an In Vitro Laboratory Evaluation. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 69 (1), 14–17. 10.1080/09674845.2012.11669916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier-Menches S. M., Gerner C., Berger W., Hartinger C. G., Keppler B. K. (2018). Structure-activity Relationships for Ruthenium and Osmium Anticancer Agents - towards Clinical Development. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (3), 909–928. 10.1039/C7CS00332C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchart M., Sadler P. J. (2006). “Ruthenium Arene Anticancer Complexes,” in Ruthenium Arene Anticancer ComplexesBioorganometallics. Editor Jaouen G. (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; ), 39–64. 10.1002/3527607692.ch2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mello-Andrade F., Cardoso C. G., Silva C. R. e., Chen-Chen L., Melo-Reis P. R. d., Lima A. P. d., et al. (2018). Acute Toxic Effects of Ruthenium(II)/amino Acid/diphosphine Complexes on Swiss Mice and Zebrafish Embryos. Biomed. Pharmacother. 107, 1082–1092. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihajlovic K., Milosavljevic I., Jeremic J., Savic M., Sretenovic J., Srejovic I., et al. (2021). Redox and Apoptotic Potential of Novel Ruthenium Complexes in Rat Blood and Heart. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 99, 207–217. 10.1139/cjpp-2020-0349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. J. L., Ikuta K. S., Sharara F., Swetschinski L., Robles Aguilar G., Gray A., et al. (2022). Global burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: a Systematic Analysis. The Lancet. 10.1016/S0140-6736(1021)02724-0272010.1016/s0140-6736(21)02724-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabiyeva T., Marschner C., Blom B. (2020). Synthesis, Structure and Anti-cancer Activity of Osmium Complexes Bearing π-bound Arene Substituents and Phosphane Co-ligands: A Review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 201, 112483. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirante J., Ruiz D., Gonzalez A., López C., Cascante M., Cortés R., et al. (2011). Platinum(II) and Palladium(II) Complexes with (N,N′) and (C,N,N′)− Ligands Derived from Pyrazole as Anticancer and Antimalarial Agents: Synthesis, Characterization and In Vitro Activities. J. Inorg. Biochem. 105 (12), 1720–1728. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Štarha P., Trávníček Z. (2019). Non-platinum Complexes Containing Releasable Biologically Active Ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 395, 130–145. 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vieites M., Smircich P., Pagano M., Otero L., Fischer F. L., Terenzi H., et al. (2011). DNA as Molecular Target of Analogous Palladium and Platinum Anti-trypanosoma Cruzi Compounds: a Comparative Study. J. Inorg. Biochem. 105 (12), 1704–1711. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav A., Janaratne T., Krishnan A., Singhal S. S., Yadav S., Dayoub A. S., et al. (2013). Regression of Lung Cancer by Hypoxia-Sensitizing Ruthenium Polypyridyl Complexes. Mol. Cancer Ther. 12 (5), 643–653. 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-12-1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan M., Chua S. L., Liu Y., Drautz-Moses D. I., Yam J. K. H., Aung T. T., et al. (2018). Repurposing the Anticancer Drug Cisplatin with the Aim of Developing Novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection Control Agents. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 14, 3059–3069. 10.3762/bjoc.14.284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yufanyi D. M., Abbo H. S., Titinchi S. J. J., Neville T. (2020). Platinum(II) and Ruthenium(II) Complexes in Medicine: Antimycobacterial and Anti-HIV Activities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 414, 213285. 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L., Gupta P., Chen Y., Wang E., Ji L., Chao H., et al. (2017). The Development of Anticancer Ruthenium(II) Complexes: from Single Molecule Compounds to Nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46 (19), 5771–5804. 10.1039/C7CS00195A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Zheng Y., Callahan B., Belfort M., Liu Y. (2011). Cisplatin Inhibits Protein Splicing, Suggesting Inteins as Therapeutic Targets in Mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 286 (2), 1277–1282. 10.1074/jbc.M110.171124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.