Abstract

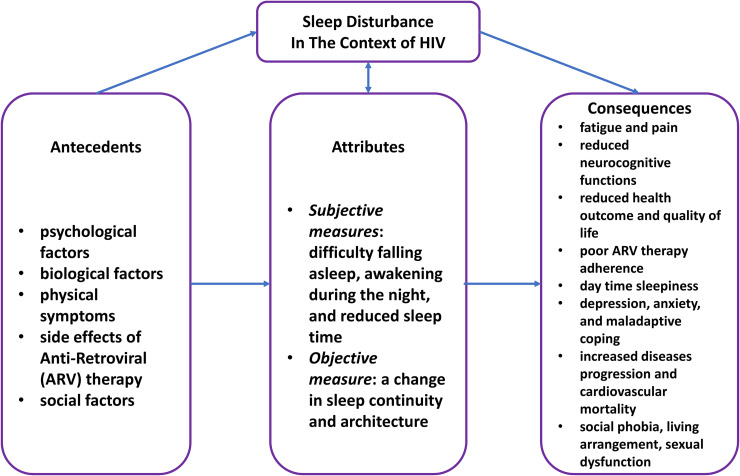

Due to the differing definitions of the concept of sleep disturbance among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), reviewers in this area have not reached any firm conclusions. The study aimed to clarify and provide a stronger foundation for the definition of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV to enhance the concept’s development. Following Beth Rodgers’ concept analysis guidelines, two leading databases were searched, and 73 articles were used for this concept analysis. The attributes, surrogate terms, antecedents, and consequences of sleep disturbance have been identified using thematic analysis. In this analysis, two main attributes of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV were identified: a) subjective measures, including reduced total sleep time, difficulty falling asleep, nighttime and early morning awakenings, feeling sleepy and poorly rested after a night’s sleep, frequent arousals, and irritability, and b) objective measures, including changes in sleep architecture and sleep continuity. Five antecedents of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV were identified.

Meanwhile, the consequences of sleep disturbance in HIV are listed based on the frequency the points occur within the reviewed articles. The list is as follows: fatigue and pain; reduced neurocognitive functions; reduced health outcome and quality of life; poor anti-retroviral (ARV) therapy adherence; daytime sleepiness; depression, anxiety, and maladaptive coping; increased disease progression and cardiovascular mortality; and social phobia, living arrangement and sexual dysfunction. An improved understanding of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV will be beneficial in directing analysts to develop research plans. At the same time, the knowledge gaps identified in the analysis provided a solid basis for further study intending to fill in these gaps.

Keywords: concept analysis, HIV, insomnia, sleep disturbance

Introduction

Why we sleep is one of the most fundamental questions asked in sleep studies, and the most straightforward answer is to overcome sleepiness (Horne, 1988). One population highly affected by inappropriate sleepiness and sleep disturbances is people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH) (Azimi et al., 2020; Balthazar et al., 2021b). It is apparent in the literature that with the onset of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, PLWH begins and continue to experience sleep disturbances (Voss et al., 2021). Sleepiness is defined as difficulty maintaining a wakeful state (Thorarinsdottir et al., 2019), and a sleep disturbance is the inability to initiate and maintain sleep (Cormier, 1990). Voss et al. (2021) found that as many as 50.0% of PLWH experience sleep disturbances and that this problem has thus far been unevaluated and untreated (Burgess et al., 2020; Gutierrez et al., 2019). This situation is likely due to uncertainties about the causes of sleep disturbances and the lack of research about sleep problem management in this group (De Francesco et al., 2021b).

The concept of sleep disturbance has been used inconsistently in the HIV context. Although sleep disturbance was most used among the terms referring to similar concepts, several other concepts have been used interchangeably, including poor sleep (Abdu & Dule, 2020; Alikhani et al., 2020; Cody et al., 2020), sleep complaint (Faraut et al., 2021; González-Tomé et al., 2018), sleep difficulty (Mahmood et al., 2018), sleep disruption (Aouizerat et al., 2021; Hixon et al., 2020), sleep pattern problem (Bedaso et al., 2020), sleep alteration (Moore et al., 2020), sleep disorder (Chen et al., 2021; Chenxi et al., 2019), and insomnia (Buchanan et al., 2018; Cody et al., 2020; Luu et al., 2022; Pujasari et al., 2020). Many previous researchers have undertaken studies to examine sleep among PLWH; however, there is no consensus on an accurate definition of sleep disturbance. The lack of an operational definition of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV has been identified in (Chen et al., 2021; Chenxi et al., 2019). Due to the differing definitions of sleep disturbance among PLWH, reviewers in this area have not reached any firm conclusions (Balthazar et al., 2021b). A clear definition of the concept of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV is crucial.

Concepts are defined as terms utilized to describe a phenomenon or a set of phenomena (Meleis, 2012). Duncan et al. (2007) posit that concepts are a shared language needed to facilitate effective professional communication. Rodgers and Knaf (2000) argued that defining the concept is critical in conducting research. A strong understanding of concepts in one’s area of interest is vital to a researcher’s success. The methodological rigor and implications of the research findings rely on how a researcher clarifies or defines these concepts.

The idea of defining concepts using concept analysis, using various approaches, has been proposed by several scholars (Knafl & Deatrick, 2000). Rodgers (Rodgers, 2000) introduced an evolutionary concept that valued dynamism and interrelationship in concept development. Her concept analysis approach specifically aimed to clarify a concept’s current use. Using Rodgers’ concept analysis as a preliminary step in conducting research is the most appropriate approach for defining concepts (Rodgers & Knaf, 2000).

In line with Rodgers’ approach, this concept analysis intends to clarify the definition of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV to reduce or eliminate the confusion created by the lack of a clear-cut delineation of the concept. Furthermore, the six steps of Rodgers (2000) approach will be employed, including 1) identifying the concept of interest; 2) selecting an appropriate setting and sample; 3) identifying antecedents, attributes, and consequences; 4) analyzing data; 5) identifying examples; and 6) identifying the implications for further development of the concept.

Materials and Methods

Identification of the Concept of Interest

The initial step in Rodgers’ concept analysis approach is to identify the concept of interest. This step is central to the approach: identifying the concept using appropriate terminology will benefit subsequent analytical efforts (Rodgers, 2000). Consistent with the previously stated purpose of the analysis, the principal terms used to identify similar surrogate terms and relevant concepts were sleep and HIV. The analysts initially used these two terms to explore and become familiar with the literature. According to Rodgers (2000), to determine an appropriate terminology, it is essential for analysts first to be familiar with the literature. From the exploration of related literature, it was found that in the context of PLWH, some terms were used interchangeably to refer to sleep problems. The most common term used in the articles was sleep disturbance, used in 17 of 73 articles. Insomnia was the second most common term used, followed by sleep disorder. Some authors used certain expressions inconsistently, using the terms sleep complaints, sleep problem, and insomnia interchangeably to reference the same concept.

Identification of Data and Sample

Choosing the data and sample relevant to the investigated concept is the second step of Rodgers (2000) concept analysis. As Rodgers’ approach is a literature-based analysis (Knafl & Deatrick, 2000), having a rigorous literature review is vital. Her evolutionary view also emphasizes the importance of the period of the material in investigating the literature. Following Rodgers’ guidelines, searches of two leading databases, Embase (n = 62) and PubMed (n = 68), were conducted. To avoid omitting relevant articles, the word sleep was used in the search instead of the phrase sleep disturbance. Any articles that used the surrogate terms sleep disturbance would also be retrieved. Therefore, the keywords sleep and HIV; sleep and immunodeficiency virus; insomnia and HIV; and insomnia and human immunodeficiency virus were used. To attain a rigorous sample, focus the investigation on the analysis aim, and make the research feasible, the following search criteria were used: a) keyword located in the title, b) journal article, c) written in English, and d) published between January 2018 and January 2022. The article abstracts were then reviewed. Some articles were excluded because of the following conditions: a) the full text was unavailable; b) use of the term sleep was not consistent with the meaning of the concept as used in this study; c) the study included other physical conditions, not within the scope of this paper, such as sleep apnea; d) the study examined additional substances, such as caffeine and marijuana; and e) redundancy in more than one database. Finally, a total of 73 articles was used for this concept analysis.

Data Collection and Management

The third step of Rodgers (2000) approach is collecting and managing the data to identify the concept’s attributes and contextual features. Continuing with Rodgers’ approach in this step, the attributes of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV were identified. In addition, the contextual elements of the concept were determined through their antecedents and consequences.

Data Analysis

After data collection, the next step of Rodgers’ concept analysis is data analysis. According to Rodgers (2000), this step is conducted using a standard procedure of qualitative research: a thematic analysis. The reviewed articles are analogue research subjects in this analysis, while the row data are attributes, contextual information, and references. Identifying major themes was conducted by organizing and reorganizing similar points. The identical points were then clustered under the same label. The frequency of issue occurrence was noted to reach a consensus, but the authors disagreed in their characterizations of the sleep architecture of PLWH.

The points that seemed outliers were also recorded. Rodgers suggested that an outlier might indicate important insight into the concept. For example, sleep disturbance is the same as a sleep disorder, but the study data concerning the concept’s consequences were quite fragmented.

Results

Attributes

Attributes establish the actual definition of a concept. Accordingly, identifying the concept’s attributes is the main accomplishment of the concept analysis (Rodgers, 2000). In this analysis, two main attributes of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV were identified: a) subjective measures, including reduced total sleep time, difficulty falling asleep, nighttime and early morning awakenings, feeling sleepy and poorly rested after a night’s sleep, frequent arousal, and irritability American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014a); and b) objective measures, including changes in sleep architecture and sleep continuity (Shikuma et al., 2018), low total sleep time and efficiency, high sleep latency, several sleep awakening (Santos et al., 2018), and suspected rapid eye movement (REM) behavior disorder (Chen et al., 2021). The analysis revealed that only a few authors explicitly defined what they meant by sleep disturbance in the context of HIV. In addition, the authors disagreed on how sleep disturbances among the PLWH population were identified. Chen et al. (2021) concluded that limited data characterizes the type of sleep disturbance in these patients. Previous studies have not yielded consistent results. It was anticipated by Rodgers (Rodgers, 2000) that authors would rarely provide actual definitions. Accordingly, when no accurate description is provided, the analysts must thoroughly review all the statements to find clues that indicate the authors’ characterization of the concept. The two attributes discovered are discussed in more detail below.

The first attribute of sleep disturbance was drawn from authors who employed subjective measures, such as questionnaires and sleep diaries, in defining sleep disturbance. Ning et al. (2020) clarified the definition of sleep disturbance as having the same meaning as insomnia. Sleep disturbance, often categorized as insomnia, includes difficulty falling asleep (initiation insomnia) and nighttime awakening (maintenance insomnia), resulting in poor sleep efficiency. Similarly, Taibi (2013) used the general definition of insomnia by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2014b) to describe sleep disturbance, stating, “Insomnia is defined as difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, awakening too early, or unrefreshing sleep in combination with at least one daytime symptom such as sleepiness or irritability.” In another article, Faraut et al. (2021) specifically defined sleep disturbance in the PLWH population, suggesting that the “subjective measures of sleep (questionnaires, sleep diaries) show disruption of sleep continuity including difficulty falling asleep, awakening during the night, and reduced sleep time.” Although Cormier (1990) did not define sleep disturbance specifically in relation to the PLWH population, it was asserted that insomnia was a surrogate term for sleep disturbance, having stated, “Sleep disturbances encompass disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (DIMS, insomnias)….” Yan et al. (2021), on the other hand, described sleep disturbance in the context of HIV using scores obtained from a general perception of sleep quality instrument, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); the study found significant sleep disturbance in PLWH having scores of five or greater on the PSQI. Alternatively, Chenxi et al. (2019) explained the definition of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV in a manner distinguishable from most authors, arguing that sleep disturbance is similar to a sleep disorder, including specific sleep behaviors, such as restless leg syndrome.

The second attribute of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV is a change or anomaly in sleep continuity and sleep architecture. This attribute was proposed based on objective measures. Taibi et al. (2013) suggested that “objective measures (polysomnography, actigraphy, sleep monitor) also show disruption of sleep onset and continuity as well as disruption of sleep stages.” Specifically, (Faraut et al., 2021) defined sleep disturbance in HIV in terms of changes in sleep quality and sleep architecture observable using increases in the short-wave stage (SWS) of sleep, greater SWS during the latter half of the sleep period, and altered non-REM (NREM) and REM sleep cycles. These findings were echoed by Chen et al. (2021), who described similar objective characteristics of sleep disturbance in HIV based on polysomnography measurements, remarkably increased SWS during later sleep cycles, persistent alfa-intrusion into SWS, and suggestions of non-restorative sleep. Using actigraphy results, De Francesco et al. (2021c) proposed that a sleep disturbance involved a longer sleep latency, shorter total sleep time, reduced sleep efficiency, and more time spent in stage 1 sleep. The authors were inconsistent in their use of specific patterns of the sleep architecture to describe sleep disturbance in the context of the HIV (De Francesco et al., 2021a). Nevertheless, a general agreement was identified: sleep disturbance in the PLWH population can be described as changes in the distribution of SWS within different sleep stages.

Antecedents

Identifying antecedents is a part of describing the contextual basis of the concept. This is done to comprehend the context of the (Rodgers, 2000). To locate antecedents, Rodgers (2000) suggested asking such questions as, “What happens before the concept?” Sleep disturbance is anteceded by a multitude of situations (Robbins et al., 2004). Four antecedents of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV were identified as follows: a) psychological factors, b) biological factors, c) physical symptoms, d) side effects of ARV therapy, and e) social factors. The researched articles reveal that psychological factors are the most frequently described antecedent of sleep disturbance in the articles. According to Alikhani et al. (2020), Chen et al. (2021), Daubert et al. (2022), Han et al. (2021), Ren et al. (2018), Wang et al. (2021), and Yan et al. (2021), psychological factors, such as depression, anxiety, and stress-related to living with a chronic illness, preceded sleep disturbance in PLWH. The second antecedent of sleep disturbance involves biological factors, including low CD4 cell levels (Shi et al., 2020), high viral load (Balthazar et al., 2021a), genetic involvement (Aouizerat et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2018), sex (De Francesco et al., 2021a; Moore et al., 2020), brain damage (Happe, 2020; Leone et al., 2021), disease progress and duration (Faraut et al., 2018b; Milinkovic et al., 2020), and decreased immune function (Babson et al., 2013; Low et al., 2012; Taibi et al., 2013).

The third antecedent, physical symptoms, includes fatigue (Chenxi et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021; Voss et al., 2021), pain (Nogueira et al., 2019; Redman et al., 2018; Sabin et al., 2020), apnea (Chen et al., 2021; Gutierrez et al., 2019), gastrointestinal symptoms (Nogueira et al., 2019), and nocturnal sweats (Thorarinsdottir et al., 2019). The fourth antecedent of sleep disturbance is the side effects of the ARV therapy (González-Tomé et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2018; Shikuma et al., 2018; Venkataraman et al., 2021), and the fifth antecedent is social factors, including family and social support (Bedaso et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2018), internalized HIV stigma (Fekete et al., 2018), unsatisfactory lifestyles (dos Santos et al., 2018), low-income (Yan et al., 2021), unemployment (Najafi et al., 2021), and behavioral risk factors (Costa et al., 2019; Downing et al., 2020; Ogunbajo et al., 2020).

Consequences

According to Rodgers (2000), consequences can result from a concept or what happens due to the concept. In this analysis, the consequences of sleep disturbance in HIV are listed based on the frequency of the points that occurred within the reviewed articles. The list is as follows: a) fatigue and pain; b) reduced neurocognitive functions; c) reduced health outcome and quality of life; d) poor anti-retroviral (ARV) therapy adherence; e) daytime sleepiness; f) depression, anxiety, and maladaptive coping; g) increased disease progression and cardiovascular mortality; and h) social phobia, living arrangement, and sexual dysfunction. Table 1 presents the identified consequences of sleep disturbance and the corresponding authors who support the same consequences in their literature.

Table 1.

Literature Support for Consequences of Sleep Disturbance in the Context of HIV.

Identification of an Exemplar

The next step after data analysis is identifying an exemplar. In Rodgers (2000) approach, an exemplar is proposed to demonstrate the practical use of the concept in a relevant situation to enhance its clarity. Because her approach is an inductive technique, Rodgers advised analysts not to construct but to identify existing exemplars. In this analysis, the exemplar was determined from the reviewed articles to maintain the analysts’ neutrality. Rodgers (2000) warned analysts not to introduce personal biases by creating or selecting an exemplar that best represented the analysts’ interests. Although multiple exemplars seem beneficial for clarity, locating an appropriate exemplar is not always easy (Rodgers, 2000). The analysts found that few articles provided exemplars, which might illustrate the current state of the concept, as predicted by Rodgers (2000). The exemplar identified in Taibi’s article (2013) was assessed to determine whether it met Rodgers (2000) criteria for an ideal exemplar. The exemplar was considered general enough to illustrate real-world practices while covering a wide range of settings.

Taibi (2013) provided the following exemplar case: Gloria was a 45-year-old woman diagnosed with HIV infection five years prior and has been on ARV therapy for four years. Her CD4 + cell levels and viral load were stable and within normal ranges. Although Gloria was overweight, had mild hypertension controlled by medication, and was experiencing osteoarthritis in both knees, she was generally healthy. Gloria reported having sleep problems for two months. She first noticed the problem when she dealt with the stress of a new job; however, her sleep problem persisted even after she found she could adjust to her new job. She reported taking two hours to fall asleep, waking three to four times, and sleeping for a total of about five hours per night. When she woke up at night, she was worried about not being able to work well the next day. She described her sleep as “terrible” and “restless” and stated that she sometimes woke up for no apparent reason while she woke up due to knee pain. She reported drinking a glass of wine and taking herbal supplements at night before sleep, and drinking 4 cups of coffee during the day. She experienced fatigue and poor concentration because of her sleep problem. Gloria’s scores on the PSQI and Insomnia Severity Index indicated moderate severity, while her Fatigue Severity Scale indicated an elevated level of fatigue. Finally, her Patient Health Questionnaire revealed mild depression.

This example represents a real-life instance of sleep disturbance experienced by PLWH. Despite no objective measure of sleep disturbance, Gloria was found to have all the subjective attributes of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV. She had difficulty falling asleep, frequently awoke at nighttime, and had reduced sleep time. Her questionnaire scores confirmed her complaints, and she experienced almost all the antecedents of sleep disturbance. She identified the psychosocial factors of stress, anxiety, and depression as the causes of her sleep problem. Still, her gender was relevant to the antecedent biological factor, as sleep disturbance is more often experienced by female PLWH. Gloria also showed the antecedent physical factors of sleep disturbance, having experienced fatigue and knee pain.

Further, Gloria was on ARV therapy, and she was taking other substances, such as alcohol and caffeine. ARV therapy and substance use are also antecedents of sleep disturbance. She also reported suffering consequences from her sleep disturbance, claiming fatigue and reduced neurocognitive function.

Discussion

Variation in the Use of the Term Sleep Disturbance in HIV

After interchangeability and inconsistencies are identified, the next step is to clarify whether the terms are surrogate or separate but relevant concepts of the main concept being analyzed. According to Rodgers (2000), surrogate terms are used interchangeably because they express the same idea or associated characteristics.

Rodgers (2000) defines relevant concepts as associated with similar thoughts but different meanings. Some authors used the term sleep disorder to refer to the same concept as sleep disturbance, and most used the term disorder to refer to a distinct concept. Sleep disorder commonly refers to a group of sleep problems, including insomnia. In contrast, sleep disturbance is used to describe a more specific type of sleep disorder (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014b). Applying the definition of relevant concepts developed by Rodgers (2000), a sleep disorder is an example of a separate but relevant sleep disturbance concept.

On the other hand, the medical discipline preferred to use the term insomnia. Both terms had the same essential characteristics. Therefore, insomnia was considered a surrogate term for sleep disturbance in this analysis. In the nursing discipline, the term sleep disturbance was most used.

Study Characteristics for Attributes

Attributes establish the actual definition of a concept. Accordingly, identifying the concept’s attributes is the primary goal of the concept analysis (Rodgers, 2000). In this analysis, two main attributes of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV were identified: a) subjective measures, including reduced total sleep (Aouizerat et al., 2021; dos Santos et al., 2018; Faraut et al., 2018a, 2021; Hixon et al., 2020; Santos et al., 2018), difficulty falling asleep, nighttime and early morning awakenings, feeling sleepy and poorly rested after a night’s sleep, frequent arousal, and irritability (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014a), and b) objective measures, including changes in sleep architecture and sleep continuity (Shikuma et al., 2018). During the analysis, it was found that only a few authors explicitly defined what they meant by sleep disturbance in the context of HIV. In addition, the authors disagreed on how sleep disturbances among PLWH were identified. Ning et al. (2020) concluded that limited data characterize the type of sleep disturbance in these patients, as previous studies have not yielded consistent results. It was anticipated by Rodgers (Rodgers, 2000) that authors would rarely provide actual definitions of the terms they used.

Identification of Implications

As in the inductive process, this concept analysis identified the current consensus in the definition of sleep disturbance among sleep and HIV scholars. Although this analysis did not provide the ultimate answer to what sleep disturbance is in the context of HIV, it has generated added information about the present stage of evolution in developing the concept. This analysis aimed to clarify and provide a firmer foundation for the concept of sleep disturbance to enhance the concept’s development.

The implications of the results of this inquiry lie along two lines. First, they have provided insights into the current status of the concept. Second, they have provided a direction for further investigation. For the analysts, the results have provided a solid foundation of the concept in their area of interest. The analytical process significantly improved the analysts’ knowledge of the concept, which will be necessary for developing an adequate research plan. Clarifying the concept can improve nursing practice by providing more information about sleep problems experienced by PLWH. The identified gaps in knowledge could be viewed as new, emerging avenues of inquiry requiring further research to develop and clarify the concept. A potential area to build upon with future research would be the necessity of investigating specific changes in the sleep architectures of PLWH. Studies investigating the association among the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of sleep disturbance in PLWH will validate the concept analysis model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Model of concept of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV.

Conclusion

Rodgers’ evolutionary approach emphasizes the dynamic nature; she posits that concepts changes with time and context. Accordingly, this concept analysis based on Rodgers’ framework has clarified the current state of the concept of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV. The attributes, surrogate terms, antecedents, and consequences of sleep disturbance have been identified using thematic analysis. A better understanding of sleep disturbance in the context of HIV will benefit the analysts, and clarifying the current definition of sleep disturbance will help develop a research plan. At the same time, the gaps in knowledge that have been identified in the analysis have provided a solid basis for further study to fill in the missing pieces of the puzzle.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all parties involved for their invaluable contribution.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by Universitas Indonesia Directorate of Research and Development, PUTI Q3 2020, grant number NKB-1817/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2020.

ORCID iDs: Hening Pujasari https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0800-9889

Min-Huey Chung https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0517-5913

References

- Abdu Z., Dule A. (2020). Poor quality of sleep among HIV-positive persons in Ethiopia [article]. HIV/AIDS – Research and Palliative Care, 12(2020), 621–628. 10.2147/HIV.S279372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alikhani M., Ebrahimi A., Farnia V., Khazaie H., Radmehr F., Mohamadi E., Davarinejad O., Dürsteler K., Sadeghi Bahmani D., Brand S. (2020). Effects of treatment of sleep disorders on sleep, psychological and cognitive functioning and biomarkers in individuals with HIV/AIDS and under methadone maintenance therapy [article]. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 130(2020), 260–272. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2014a). http://www.aasmnet.org/practiceparameters.aspx?cid=109

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2014b). International classification of sleep disorders (3rd ed.). American Academy of Sleep Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Aouizerat B. E., Byun E., Pullinger C. R., Gay C., Lerdal A., Lee K. A. (2021). Sleep disruption and duration are associated with variants in genes involved in energy homeostasis in adults with HIV/AIDS [article]. Sleep Medicine, 82(2021), 84–95. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azimi H., Gunnarsdottir K. M., Sarma S. V., Gamaldo A. A., Salas R. M. E., Gamaldo C. E. (2020). Identifying Sleep Biomarkers to Evaluate Cognition in HIV. Annual International Conference IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2020, 2332–2336. 10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.9176592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babson K. A., Heinz A. J., Bonn-Miller M. O. (2013). HIV Medication adherence and HIV symptom severity: The roles of sleep quality and memory. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 27(10), 544–552. 10.1089/apc.2013.0221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazar M. S., Webel A., Gary F., Burant C. J., Totten V. Y., Voss J. G. (2021a). Sleep and immune function among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). AIDS Care, 33(9), 1196–1200. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1770180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazar M. S., Webel A., Gary F., Burant C. J., Totten V. Y., Voss J. G. (2021b). Sleep and immune function among people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [article]. AIDS Care – Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 33(9), 1196–1200. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1770180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedaso A., Abraham Y., Temesgen A., Mekonnen N. (2020). Quality of sleep and associated factors among people living with HIV/AIDS attending ART clinic at Hawassa University comprehensive specialized Hospital, Hawassa, SNNPR, Ethiopia. PloS One, 15(6), e0233849. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan D. T., McCurry S. M., Eilers K., Applin S., Williams E. T., Voss J. G. (2018). Brief behavioral treatment for insomnia in persons living with HIV [article]. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 16(3), 244–258. 10.1080/15402002.2016.1188392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess H. J., Williams B., Landay A., Engen P., Raeisi S., Naqib A., Fogg L. L., Keshavarzian A., Rasmussen H. E., Zhang X., Hamaker B., Green S. J. (2020). Sleep health should be included as a therapeutic target in the treatment of HIV. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 36(8), 631. 10.1089/AID.2020.0094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Vansteenkiste M., Delesie L., Soenens B., Tobback E., Vogelaers D., Mariman A. (2019). The role of basic psychological need satisfaction, sleep, and mindfulness in the health-related quality of life of people living with HIV. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(4), 535–545. 10.1177/1359105316678305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaponda M., Aldhouse N., Kroes M., Wild L., Robinson C., Smith A. (2018). Systematic review of the prevalence of psychiatric illness and sleep disturbance as co-morbidities of HIV infection in the UK. Int J STD AIDS, 29(7), 704–713. 10.1177/0956462417750708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. C., Chen C. C., Strollo P. J., Jr., Li C. Y., Ko W. C., Lin C. Y., Ko N. Y. (2021). Differences in sleep disorders between HIV-infected persons and matched controls with sleep problems: A matched-cohort study based on laboratory and survey data. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(21), 5206. 10.3390/jcm10215206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenxi N., Xiaoxiao C., Haijiang L., Xiaotong Q., Yuanyuan X., Weiwei S., Dan Z., Na H., Yingying D. (2019). Characteristics of sleep disorder in HIV positive and HIV negative individuals: A cluster analysis [article]. Chinese Journal of Endemiology, 40(5), 499–504. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody S. L., Fazeli P. L., Crowe M., Kempf M. C., Moneyham L., Stavrinos D., Vance D. E., Heaton K. (2020). Effects of speed of processing training and transcranial direct current stimulation on global sleep quality and speed of processing in older adults with and without HIV: A pilot study [article]. Applied Neuropsychology. Adult, 27(3), 267–278. 10.1080/23279095.2018.1534736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody S. L., Hobson J. M., Gilstrap S. R., Gloston G. F., Riggs K. R., Justin Thomas S., Goodin B. R. (2021). Insomnia severity and depressive symptoms in people living with HIV and chronic pain: associations with opioid use. AIDS Care, 1–10. 10.1080/09540121.2021.1889953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier R. E. (1990). Sleep disturbances. In Walker H. K., Hall W. D., Hurst J. W. (Eds.), Clinical methods: the history, physical, and laboratory examinations. Butterworths Copyright © 1990, 398–403. Butterworth Publishers, a division of Reed Publishing. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M., Rojas T. R., Lacoste D., Villes V., Aumaitre H., Protopopescu C., Yaya I., Wittkop L., Krause J., Salmon-Ceron D., Marcellin F., Sogni P., Carrieri M. P., Group A. C. H. S. (2019). Sleep disturbances in HIV-HCV coinfected patients: Indications for clinical management in the HCV cure era (ANRS CO13 HEPAVIH cohort). European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 31(12), 1508–1517. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daubert E., French A. L., Burgess H. J., Sharma A., Gustafson D., Cribbs S. K., Weiss D. J., Ramirez C., Konkle-Parker D., Kassaye S., Weber K. M. (2022). Association of poor sleep with depressive and anxiety symptoms by HIV disease Status: women’s interagency HIV study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 89(2), 222–230. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco D., Sabin C. A., Winston A., Mallon P. W. G., Anderson J., Boffito M., Doyle N. D., Haddow L., Post F. A., Vera J. H., Sachikonye M., Redline S., Kunisaki K. M. (2021a). Agreement between self-reported and objective measures of sleep in people with HIV and lifestyle-similar HIV-negative individuals. AIDS (London, England), 35(7), 1051–1060. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco D., Sabin C. A., Winston A., Mallon P. W. G., Anderson J., Boffito M., Doyle N. D., Haddow L., Post F. A., Vera J. H., Sachikonye M., Redline S., Kunisaki K. M. (2021b). Agreement between self-reported and objective measures of sleep in people with HIV and lifestyle-similar HIV-negative individuals [article]. AIDS (London, England), 35(7), 1051–1060. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Francesco D., Sabin C. A., Winston A., Rueschman M. N., Doyle N. D., Anderson J., Vera J. H., Boffito M., Sachikonye M., Mallon P. W. G., Haddow L., Post F. A., Redline S., Kunisaki K. M. (2021c). Sleep health and cognitive function among people with and without HIV: The use of different machine learning approaches. Sleep, 44(8), 1–13. 10.1093/sleep/zsab035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Lin H., Zhou S., Wang K., Li L., Zhang Y., Yao Y., Gao M., Liu X., He N. (2018). Stronger association between insomnia symptoms and shorter telomere length in old HIV-infected patients compared with uninfected individuals. Aging and Disease, 9(6), 1010–1019. 10.14336/AD.2018.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos I. K., de Azevedo K. P. M., Melo F. C. M., de Lima K. K. F., Pinto R. S., Dantas P. M. S., de Medeiros H. J., Knackfuss M. I. (2018). Lifestyle and sleep patterns among people living with and without HIV/AIDS [article]. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 51(4), 513–517. 10.1590/0037-8682-0235-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing M. J., Millar B. M., Hirshfield S. (2020). Changes in sleep quality and associated health outcomes among gay and bisexual men living with HIV. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 18(3), 406–419. 10.1080/15402002.2019.1604344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C., Cloutier J. D., Bailey P. H. (2007). Concept analysis: The importance of differentiating the ontological focus. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(3), 293–300. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraut B., Malmartel A., Ghosn J., Duracinsky M., Leger D., Grabar S., Viard J. P. (2018a). Sleep disturbance and total sleep time in persons living with HIV: A cross-sectional study [article]. AIDS and Behavior, 22(9), 2877–2887. 10.1007/s10461-018-2179-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraut B., Malmartel A., Ghosn J., Duracinsky M., Leger D., Grabar S., Viard J. P. (2018b). Sleep disturbance and total sleep time in persons living with HIV: A cross-sectional study. AIDS and Behavior, 22(9), 2877–2887. 10.1007/s10461-018-2179-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraut B., Tonetti L., Malmartel A., Grabar S., Ghosn J., Viard J. P., Natale V., Leger D. (2021). Sleep, prospective memory, and immune status among people living with HIV. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 1–15. 10.3390/ijerph18020438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete E. M., Williams S. L., Skinta M. D. (2018). Internalised HIV-stigma, loneliness, depressive symptoms and sleep quality in people living with HIV. Psychology & Health, 33(3), 398–415. 10.1080/08870446.2017.1357816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Tomé M. I., García-Navarro C., Ruiz-Saez B., Sainz T., Jiménez De Ory S., Rojo P., Mellado Peña M. J., Prieto L., Muñoz-Fernandez M. A., Zamora B., Cuéllar-Flores I., Velo C., Martin-Bejarano M., Ramos J. T., Navarro Gómez M. L. (2018). Sleep profile and self-reported neuropsychiatric symptoms in vertically HIV-infected adolescents on cART [article]. Journal of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 13(4), 300–307. 10.1055/s-0038-1673416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez J., Tedaldi E. M., Armon C., Patel V., Hart R., Buchacz K. (2019). Sleep disturbances in HIV-infected patients associated with depression and high risk of obstructive sleep apnea [article]. SAGE Open Medicine, 7(2019), 1–11. 10.1177/2050312119842268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Hu Y., Pei Y., Zhu Z., Qi X., Wu B. (2021). Sleep satisfaction and cognitive complaints in Chinese middle-aged and older persons living with HIV: The mediating role of anxiety and fatigue. AIDS Care, 33(7), 929–937. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1844861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happe S. (2020). HIV Infection and sleep disturbances [review]. Nervenheilkunde, 39(9), 548–550. 10.1055/a-1213-6750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hixon B., Burgess H. J., Wilson M. P., MaWhinney S., Jankowski C. M., Erlandson K. M. (2020). A supervised exercise intervention fails to improve subjective and objective sleep measures among older adults with and without HIV. HIV Res Clin Pract, 21(5), 121–129. 10.1080/25787489.2020.1839708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne J. (1988). Why we sleep: the functions of sleep in humans and other mammals In (pp. 310–311). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Chen W. T., Shiu C. S., Sun W., Radaza A., Toma L., . . . Ah-Yune J. (2021). Physical symptoms and sleep disturbances activate coping strategies among HIV-infected Asian Americans: a pathway analysis. AIDS Care, 33(9), 1201–1208. 10.1080/09540121.2021.1874270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K. A., Deatrick J. A. (2000). Knowledge synthesis and concept development in nursing. In Rodgers B. L., Knafl K. A. (Eds.), Concept development in nursing: foundations, techniques, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 39–53). Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Leone M. J., Sun H., Boutros C. L., Liu L., Ye E., Sullivan L., Thomas R. J., Robbins G. K., Mukerji S. S., Westover M. B. (2021). HIV Increases sleep-based brain age despite antiretroviral therapy. Sleep, 44(8), 1–9. 10.1093/sleep/zsab058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low Y., Goforth H. W., Omonuwa T., Preud‘homme X., Edinger J., Krystal A. (2012). Comparison of polysomnographic data in age-, sex- and axis I psychiatric diagnosis matched HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative insomnia patients. Clinical Neurophysiology, 123(12), 2402–2405. 10.1016/j.clinph.2012.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu B. R., Nance R. M., Delaney J. A. C., Ruderman S. A., Heckbert S. R., Budoff M. J., Mathews W. C., Moore R. D., Feinstein M. J., Burkholder G. A., Eron J. J., Mugavero M. J., Saag M. S., Kitahata M. M., Crane H. M., Whitney B. M. (2022). Insomnia and risk of myocardial infarction among people with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 90(1), 50–55. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood Z., Hammond A., Nunez R. A., Irwin M. R., Thames A. D. (2018). Effects of sleep health on cognitive function in HIV + and HIV- adults. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 24(10), 1038–1046. 10.1017/S1355617718000607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis A. I. (2012). Theory: metaphors, symbols, definitions. In Theoretical nursing: development & progress (5th ed., pp. 23–38). Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. P [Google Scholar]

- Milinkovic A., Singh S., Simmons B., Pozniak A., Boffito M., Nwokolo N. (2020). Multimodality assessment of sleep outcomes in people living with HIV performed using validated sleep questionnaires. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 31(10), 996–1003. 10.1177/0956462420941693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore S. E., Voss J. G., Webel A. R. (2020). Sex-Based differences in plasma cytokine concentrations and sleep disturbance relationships among people living with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 31(2), 249–254. 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi A., Mahboobi M., Sadeghniiat Haghighi K., Aghajani F., Nakhostin-Ansari A., Soltani S., Jafarpour A., Afsar Kazerooni P., Bazargani M., Ghodrati S., Akbarpour S. (2021). Sleep disturbance, psychiatric issues, and employment status of Iranian people living with HIV [article]. BMC Research Notes, 14(1), 338. 10.1186/s13104-021-05755-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning C., Lin H., Chen X., Qiao X., Xu X., Xu X., Shen W., Liu X., He N., Ding Y. (2020). Cross-sectional comparison of various sleep disturbances among sex- and age-matched HIV-infected versus HIV-uninfected individuals in China. Sleep Medicine, 65(2020), 18–25. 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira L. F. R., da Fonseca T. C., Paterlini P. H., Duarte A. S., Pellegrino P., Barros C., Moreno C. R. C., Marqueze E. C. (2019). Influence of nutritional status and gastrointestinal symptoms on sleep quality in people living with HIV. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 30(9), 885–890. 10.1177/0956462419846723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbajo A., Restar A., Edeza A., Goedel W., Jin H., Iwuagwu S., Williams R., Abubakari M. R., Biello K., Mimiaga M. (2020). Poor sleep health is associated with increased mental health problems, substance use, and HIV sexual risk behavior in a large, multistate sample of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) in Nigeria, Africa [article]. Sleep Health, 6(5), 662–670. 10.1016/j.sleh.2020.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujasari H., Culbert G. J., Levy J. A., Steffen A., Carley D. W., Kapella M. C. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of insomnia in people living with HIV in Indonesia: A descriptive, cross-sectional study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 31(5), 606–614. 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujasari H., Levy J., Culbert G., Steffen A., Carley D., Kapella M. (2021). Sleep disturbance, associated symptoms, and quality of life in adults living with HIV in Jakarta, Indonesia. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 33(1), 39–46. 10.1080/09540121.2020.1748868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman K. N., Karstaedt A. S., Scheuermaier K. (2018). Increased CD4 counts, pain and depression are correlates of lower sleep quality in treated HIV positive patients with low baseline CD4 counts [article]. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 69(2018), 548–555. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., Zhao M., Liu B., Wu Q., Hao Y., Jiao M., Qu L., Ding D., Ning N., Kang Z., Liang L., Liu H., Zheng T. (2018). Factors associated with sleep quality in HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 29(6), 924–931. 10.1016/j.jana.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J. L., Phillips K. D., Dudgeon W. D., Hand G. A. (2004). Physiological and psychological correlates of sleep in HIV infection. Clinical Nursing Research, 13(1), 33–52. 10.1177/1054773803259655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B. L. (2000). Concept analysis: an evolutionary view. In Rodgers B. L., Knafl K. A. (Eds.), Concept development in nursing: foundations, techniques, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 77–102). Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B. L., Knaf L. A. (2000). Applications and future directions for concept development in nursing. In Rodgers B. L., Knafl K. A. (Eds.), Concept development in nursing: foundations, techniques, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 401–409). PA Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers B. G., Bainter S. A., Smith-Alvarez R., Wohlgemuth W. K., Antoni M. H., Rodriguez A. E., Safren S. A. (2021). Insomnia, health, and health-related quality of life in an urban clinic sample of people living with HIV/AIDS. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 19(4), 516–532. 10.1080/15402002.2020.1803871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers B. G., Lee J. S., Bainter S. A., Bedoya C. A., Pinkston M., Safren S. A. (2020). A multilevel examination of sleep, depression, and quality of life in people living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(10-11), 1556–1566. 10.1177/1359105318765632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin C. A., Harding R., Doyle N., Redline S., de Francesco D., Mallon P. W. G., Post F. A., Boffito M., Sachikonye M., Geressu A., Winston A., Kunisaki K. M. (2020). Associations between widespread pain and sleep quality in people with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 85(1), 106–112. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos I. K. D., Azevedo K. P. M., Melo F. C. M., Lima K. K. F., Pinto R. S., Dantas P. M. S., Medeiros H. J., Knackfuss M. I. (2018). Lifestyle and sleep patterns among people living with and without HIV/AIDS. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 51(4), 513–517. 10.1590/0037-8682-0235-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Yang C., Xu L., He Y., Wang H., Cao J., Wen M., Chen W., Wu B., Chen S., Chen H. (2020). CD4 + T Cell count, sleep, depression, and anxiety in people living with HIV: A growth curve mixture modeling. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 31(5), 535–543. 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikuma C. M., Kohorn L., Paul R., Chow D. C., Kallianpur K. J., Walker M., Souza S., Gangcuangco L. M. A., Nakamoto B. K., Pien F. D., Duerler T., Castro L., Nagamine L., Soll B. (2018). Sleep and neuropsychological performance in HIV + subjects on efavirenz-based therapy and response to switch in therapy [article]. HIV Clinical Trials, 19(4), 139–147. 10.1080/15284336.2018.1511348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun-Suslow N., Campbell L. M., Tang B., Fisher A. C., Lee E., Paolillo E. W., Moore R. C.. (2022). Use of digital health technologies to examine subjective and objective sleep with next-day cognition and daily indicators of health in persons with and without HIV. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 45(1), 62–75. 10.1007/s10865-021-00233-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taibi D. M. (2013). Sleep disturbances in persons living with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24(1 Suppl), S72–S85. 10.1016/j.jana.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taibi D. M., Price C., Voss J. (2013). A pilot study of sleep quality and rest-activity patterns in persons living with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24(5), 411–421. 10.1016/j.jana.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorarinsdottir E. H., Bjornsdottir E., Benediktsdottir B., Janson C., Gislason T., Aspelund T., Kuna S. T., Pack A. I., Arnardottir E. S. (2019). Definition of excessive daytime sleepiness in the general population: feeling sleepy relates better to sleep-related symptoms and quality of life than the epworth sleepiness scale score. Results from an epidemiological study. Journal of Sleep Research, 28(6), e12852. 10.1111/jsr.12852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman A., Zhuang Y., Marsella J., Tivarus M. E., Qiu X., Wang L., Zhong J., Schifitto G. (2021). Functional MRI correlates of sleep quality in HIV. Nature and Science of Sleep, 13(2021), 291–301. 10.2147/NSS.S291544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss J. G., Barroso J., Wang T. (2021). A critical review of symptom management nursing science on HIV-related fatigue and sleep disturbance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(20), 1–18. 10.3390/ijerph182010685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Wang M., Xin X., Zhang T., Wu H., Huang X., Liu H. (2021). Exploring the relationship between anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance among HIV patients in China from a network perspective [article]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12(2021), 1–10. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.764246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D. Q., Huang Y. X., Chen X., Wang M., Li J., Luo D. (2021). Application of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh sleep quality Index in people living with HIV: preliminary reliability and validity. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12(2021), 676022. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.676022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. Q., Li L., Zhong B. L. (2021). Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in older chinese adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne ), 8, 779914. 10.3389/fmed.2021.779914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]