Abstract

Worldwide head injuries are a growing problem. In the United States alone, 1.7 million people suffer a head injury each year. While most of these injuries are mild, head injury sufferers still sustain symptoms that can have major medical and economical impacts. Moreover, repetitive mild head injuries, like those observed in active military personnel and athletes, have demonstrated a more severe and long-term set of consequences. In an effort to better understand the delayed pathological changes following multiple mild head injuries, we used a mouse model of mild closed head injury (with no motor deficits observed by rotarod testing) and measured dendritic complexity at 30 days after injury and potentially related factors up to 60 days post-injury. We found an increase in TDP-43 protein at 60 days post-injury in the hippocampus and a decrease in autophagy factors three days post-injury. Alterations in dendritic complexity were neuronal subtype and location specific. Measurements of neurotropic factors suggest that an increase in complexity in the cortex may be a consequence of neuronal loss of the less connected neurons.

Keywords: autophagy, dendritic complexity, repetitive injury, transcription factors, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Repeated mild head injuries have become a hallmark affliction of military personnel and veterans, as well as athletes at all levels of play throughout the world.1,2 This repetitive injury produces a distinct pathology compared with a single isolated event. One of the most common ongoing post-traumatic brain injury (TBI) cognitive deficits is memory impairment.3,4 This may result partially from damage to the hippocampus, which is sensitive to mechanical injury.5 Memory deficits after TBI have been demonstrated in animal models, including rodents with neuronal loss in the hippocampus and associated cognitive deficits. Importantly, animal models have shown that closed head injury results in cognitive deficits similar to those of human patients with TBI.6

Although for some patients symptoms only persist for days or weeks, approximately 10% have long-term deficits from mild TBI.7–10 Initial clinical presentation may not show extensive damage or dramatic symptoms. More severe damage and dementia-like symptoms may result after many months, however. In addition, TBI is also a major risk factor for other neuropathologies.

Multiple concussive injuries can result in an increase in protein aggregates, including transactivation response (TAR) deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) protein 43 (TDP-43).11 The TDP-43 is a transcriptional repressor that binds to TAR elements on DNA. A hyperphosphorylated, polyubiquitinated, and cleaved form of TDP-43 is known as “pathogenic TDP-43” and has been implicated in the progression of several neurological diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia,12 and Alzheimer disease (AD).13 An increase in hyperphosphorylated TDB-43, as well as tau protein,14,15 in response to multiple brain injuries may cause a patient to have behavioral changes and a progressive decline in memory similar to neurodegenerative disorders such as AD.16 Understanding the accumulation and clearance of proteins after a head injury is important to developing therapeutics to prevent protein aggregates from forming and resulting neuronal disorders.

One mechanism by which proteins are cleared is autophagy, which plays an essential role in maintaining homeostasis by regulating protein and organelle turnover. Dysregulation in this system leads to severe neuropathology in a variety of disorders in the central nervous system.17 Polyubiquitinated TDP-43 is cleared by the proteasome and macroautophagy; however, accumulation of tau has also been shown to inhibit clearance of TDP-43, resulting in its accumulation.18 Several autophagy factors may also play a role in the accumulation and clearance of TDP-43 and other pathogenic proteins, including LAMP-2A,19 LC3b,20 and Atg7.21

To mimic the scenario that many service personnel or athletes encounter, we performed multiple mild closed head injuries in model mice. We monitored dendritic complexity at 30 days after the last injury when any initial impact-associated cell loss should have subsided. We also measured messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) and protein expression of several autophagy and neurotropic factors at multiple time points after the final injury as long as 60 days after the last injury to span the dendritic observations and include chronic effects.

We used the 30 g weight-drop model that delivers a noninvasive, closed injury to the skull of the mice.6 We use this injury model because it accurately recapitulates the impact, neuropathology, and symptoms that are observed in patients. This model also has a well-defined time course of cognitive deficits (frequently with measurements at 30 days after injury) that correlate with impact force.6,22,23 The cognitive deficits observed in the injured mice are not accompanied by morphological or nonspecific brain damage (e.g., edema), but do produce a combination of axonal and cell body changes.24 Further, the injury-induced cognitive deficits are accompanied by apoptotic and necrotic damage to neurons.24–26 With this model, we found that multiple mild injuries on the brain alter both long-term biochemistry and dendritic complexity in neurons, and that these effects are not ubiquitous but are very tissue specific.

Methods

Animals

The animal protocol was approved by the Bay Pines VA Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) and performed in accordance with all institutional, agency, and governmental Animal Welfare Regulations.

Male CD-1 mice at three months of age and weighing between 31 and 34 g were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). They were housed three to four per cage in a 22°C ± 0.5°C temperature controlled environment with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum.

Closed head injury

Mild TBI (mTBI) was induced using a concussive closed head injury weight drop model as described previously.6 Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed on a sponge, which allows for impact and movement of the head to inflict a diffuse concussive injury.22 The injury apparatus was positioned directly over the head such that the inner diameter of the tube (13 mm) spanned the right hemisphere caudal to the eye and rostral to the ear. A 30 g (for repetitive injuries and the single injury dendritic analysis) or 50 g (for all other single injuries) cylindrical weight was dropped 80 cm through the length of the tube in injured mice (n = 19). Sham mice (n = 19) did not receive the weight drop portion of the procedure. This injury, which has been demonstrated to cause a mild injury,24 was repeated five times at 24 h intervals or just once (Fig. 1A). Mice were allowed to recover from anesthesia in a heated chamber.

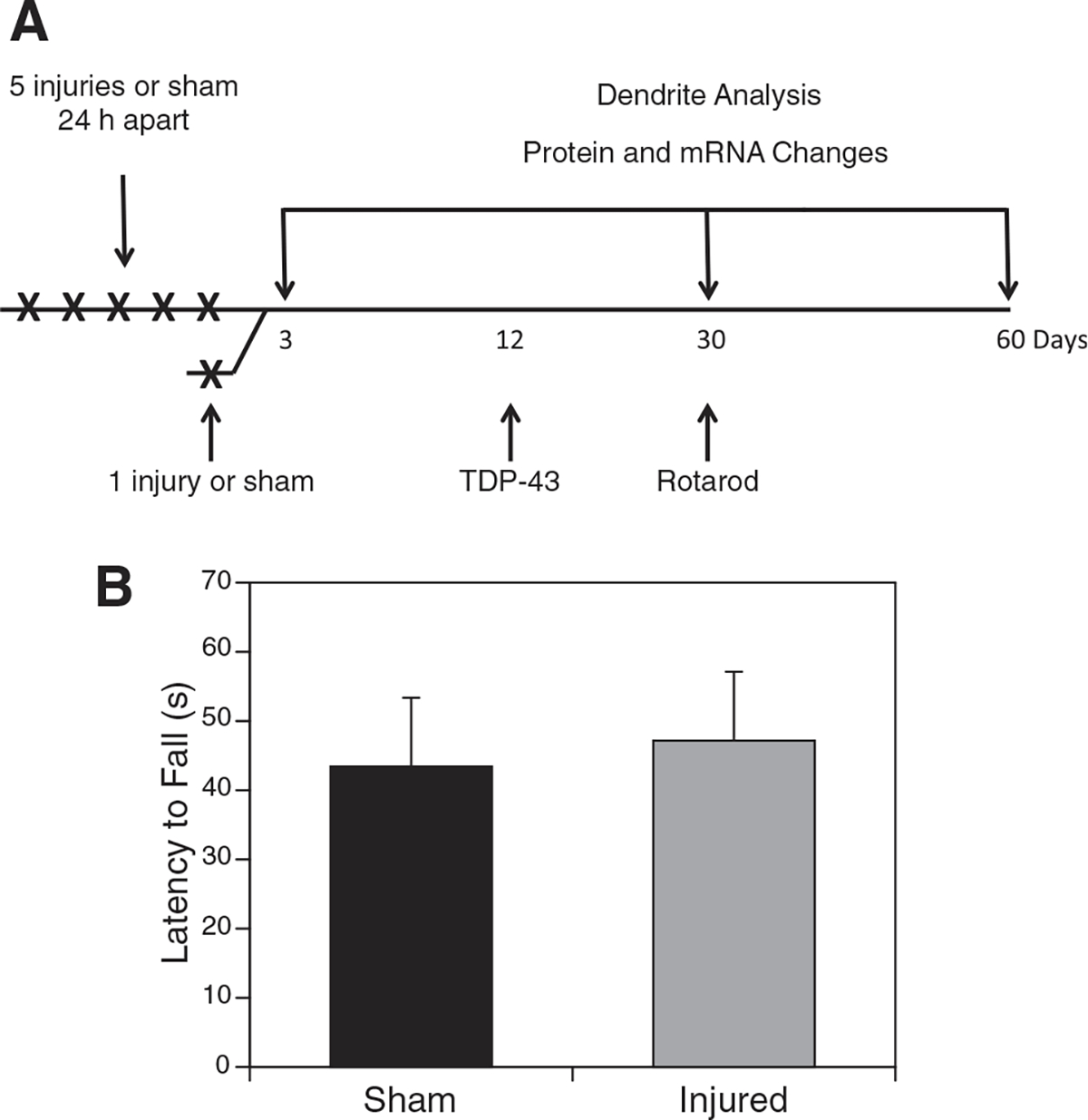

FIG. 1.

Timeline for 1 × and 5 × injuries. Mice in the injury group received a single injury or five injuries 24 h apart (A). For the 1 × injury, brains were harvested and analyzed for transactivation response deoxyribonucleic acid protein 43 (TDP-43) expression. For the 5 × injury, brains were harvested at 3, 30, and 60 days post-injury for analysis. At 30 days post-injury, mice underwent rotarod testing to determine whether there were any observable motor deficits (B). No significant difference was observed with time spent on an accelerating rotarod (measuring motor and balance function) after repetitive injury compared with the sham-injured controls. mRNA, messenger ribonucleic acid.

Behavioral tests

A rotarod performance test was administered to a subset of mice (n = 5/group) at 30 days after the final injury or sham procedure to test motor skills. A Stoelting 57620 apparatus was used, consisting of a horizontally oriented dowel beginning at 5 rpm and slowly accelerating to 40 rpm. Mice were placed on the dowel, and the amount of time the mice were able to stay on the rod before falling off was measured. Mice were allowed three practice trials followed by a break of at least 30 min before beginning three recorded trials with three min of rest between each run.

Tissue collection

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation, and brain tissue was rapidly dissected while chilled on ice, then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was stored at −80°C.

Protein analysis

Proteins were isolated from the ipsilateral (right) cortex and hippocampus using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Protein concentration was quantified by bicinchoninic acid assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were separated on a 4–20% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel (Pierce), transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE), blocked with Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences), and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Controls lacking only the primary antibody were performed to make sure that bands visualized were specific.

The following day, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescent infrared (IR) dyes (LI-COR) for 1 h at 23°C, then scanned onto a LI-COR Odyssey IR Scanner and analyzed using Image Studio software (LI-COR). Primary antibodies used were: TARDBP (TDP-43) 1:1000 (10782-2-AP; Proteintech, Chicago, IL), LAMP-2A 1:500 (PA1-655; Thermo-Fisher, Waltham, MA), Apg7 1:1000 (AB133528, Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, MA), LC3b 1:1000 (AB63817, Abcam, Inc.), bone derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) 1:1000 (SC-546; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Netrin-1 1:100 (AB26162; Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, MA), nerve growth factor (NGF) 1:500 (AB6199; Abcam, Inc.), and glial fibrillary acidic protein [GFAP] 1:1000 (AB5804; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA). Secondary antibodies used were: goat anti-rabbit IR dye 800 (926-32211; LI-COR) and goat anti-mouse IR dye 680 (926-68070; LI-COR).

mRNA analysis

Frozen tissue from the ipsilateral (right) cortex was homogenized in QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), phase separated with chloroform, and RNA was precipitated with 70% ethanol. Purification of mRNA was performed using an RNeasy Mini Kit (74104; Qiagen) per the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA concentration was determined by NanoDrop (Thermo-Scientific, Waltham, MA). Potential changes in mRNA levels were checked by qRT-PCR with QuantiTect SYBR reagents (BioRad, Hercules, CA), primers (for Lamp-2A, BDNF, Netrin-1, and NGF) from IDT (Coralville, IA), and a CFX Connect fluorescent thermocycler (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

Dendritic analysis

At 30 days after the final injury, mice were perfused with phosphate buffered saline followed by 10% neutral buffered formalin. Whole brains were removed and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Formalin-fixed tissue blocks (2–3 mm thick in the coronal plane) incorporating the cortical samples were stained by the Rapid Golgi method and evaluated for the amount and distribution of dendritic branching by Sholl analysis and for the complexity of the dendritic arbor using branch point analysis as performed previously.27 Locations were confirmed in each brain sample by comparing the coronal sections to the mouse brain atlas,28 and measurements of Golgi stained neurons were made in regions including the parietal cortex, the dentate gyrus, and the striatum.

Briefly, the fixed tissue blocks were placed initially in potassium dichromate and osmium tetroxide for approximately six days, transferred to 0.75% silver nitrate for approximately 40 h, dehydrated through ascending concentration of alcohol solutions and ethyl ether, infiltrated with ascending concentrations of nitrocellulose solutions (5%, 10%, 20%, 30%; 1–2 days each), placed in plastic molds, and hardened by exposure to chloroform vapors. Tissue sections were cut in the coronal plane at a thickness of 120 microns using an AO sliding microtome, cleared in alpha-terpineol, thoroughly rinsed with xylene, and mounted on slides with Permount. In all cases, Golgi stained neurons of a specific cell population that were randomly selected for dendritic analysis had to meet strict criteria: they had to be well impregnated; the branches could not be obscured by other neurons or their dendrites, glia, blood vessels, or undefined precipitate (an occasional staining by-product), and the soma had to be located in the middle third of the thickness of the section. Camera lucida drawings were prepared using Zeiss brightfield research microscopes equipped with long-working distance oil-immersion objective lenses and drawing tubes.

Analyses of the dendritic arbors were subdivided into two types: the Sholl analysis, which defined the amount and distribution of the dendritic arbor, including an estimate of the total dendritic length, and the dendritic branch point analysis that—based on the number of branch points and dendritic bifurcations within the dendritic domain—characterized the complexity of the arbor. In addition, the area of the soma of each neuron was measured using a digitizing tablet linked to the drawing tube of the microscope. There were 3–5 brains examined per group and at least five neurons from each brain were measured (nine neurons per brain when the group size was low). All data from the coded neurons were analyzed statistically with Prism software.

Statistical analysis

Mean values are depicted ± standard deviation and were compared with the two tailed t test or analysis of variance, as indicated in the legends, with p < 0.05 indicating significance. For Sholl and branch point analyses, the Wilcoxon rank-sign test was used also to compare dendritic branching profiles of the two groups. When appropriate, an adjusted alpha level was used to account for multiple comparisons.

Results

Motor function after multiple injuries

To accomplish the mild, closed head, repetitive injury, mice underwent five mild injuries (30 g weight drop) on the right hemisphere with 24 h between each injury as depicted in the timeline (Fig. 1A). Animals were monitored closely after each injury to ensure they did not have any obvious symptoms—i.e., gross motor deficits. Thirty days after the final injury, motor function of the mice was monitored using a rotarod. No differences were observed between injured and uninjured (Fig. 1B). Similar results were found with single injuries with only transient deficits within the first seven post-injury days (data not shown).

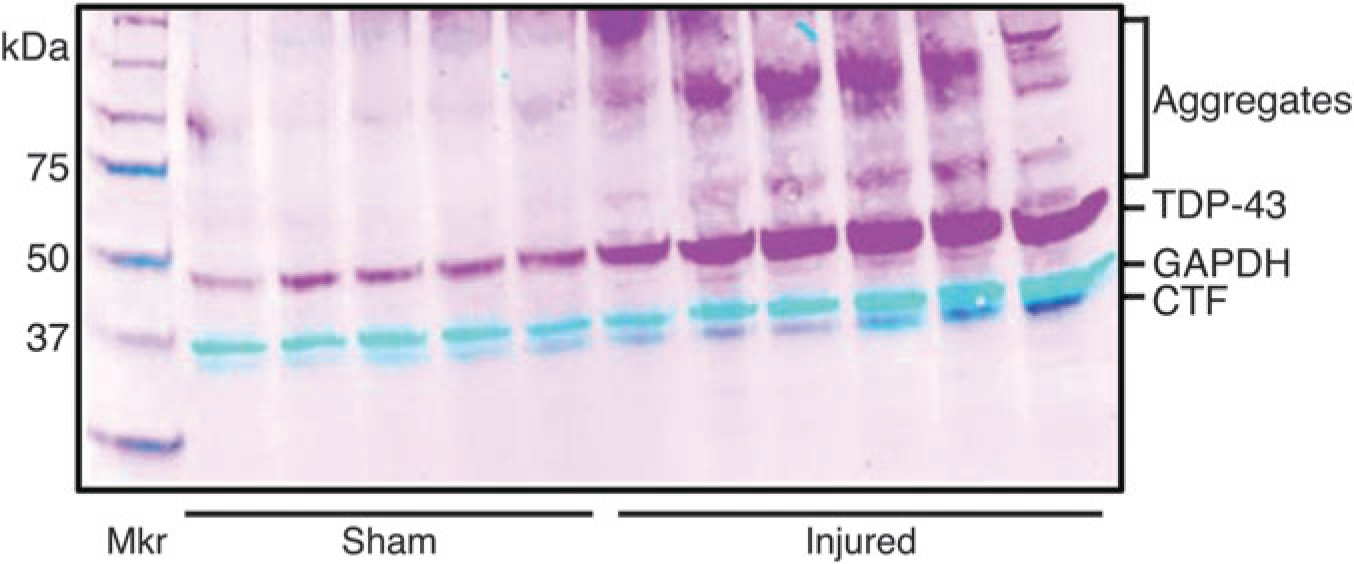

TDP-43 expression after 1 × head injury

The TDP-43 expression was evaluated after single and multiple head injuries. Twelve days after the single 50 g injury, mice were sacrificed; subregions of the brain were dissected, and TDP-43 protein expression was measured. Western blots identify significantly increased TDP-43 (green) expression in the cortex of injured male mice compared with sham controls 12 days post-injury. The glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was run as a loading control (red). The TDP-43 associated bands observed at approximately 25, 35, 60, and 100 kDa also increased with injury (Fig. 2). Apparent TDP-43 C-terminal fragments and aggregates, based on the literature, known to be toxic in several neuronal disorders29 were also present after injury.

FIG. 2.

Transactivation response deoxyribonucleic acid protein 43 (TDP-43) expression 12 days after a 1 × 50 g head injury. Western blots were performed 12 days post-injury on the ipsilateral cortex of mice receiving a single injury or sham. The dual labeled, fluorescent, inverted signals appear as magenta (TDP-43) and cyan (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase [GAPDH]). An increase in TDP-43 expression (*p < 0.05) was found in injured mice compared with sham and aggregates, and C-terminal fragment (CTF) bands were observed (n = 5).

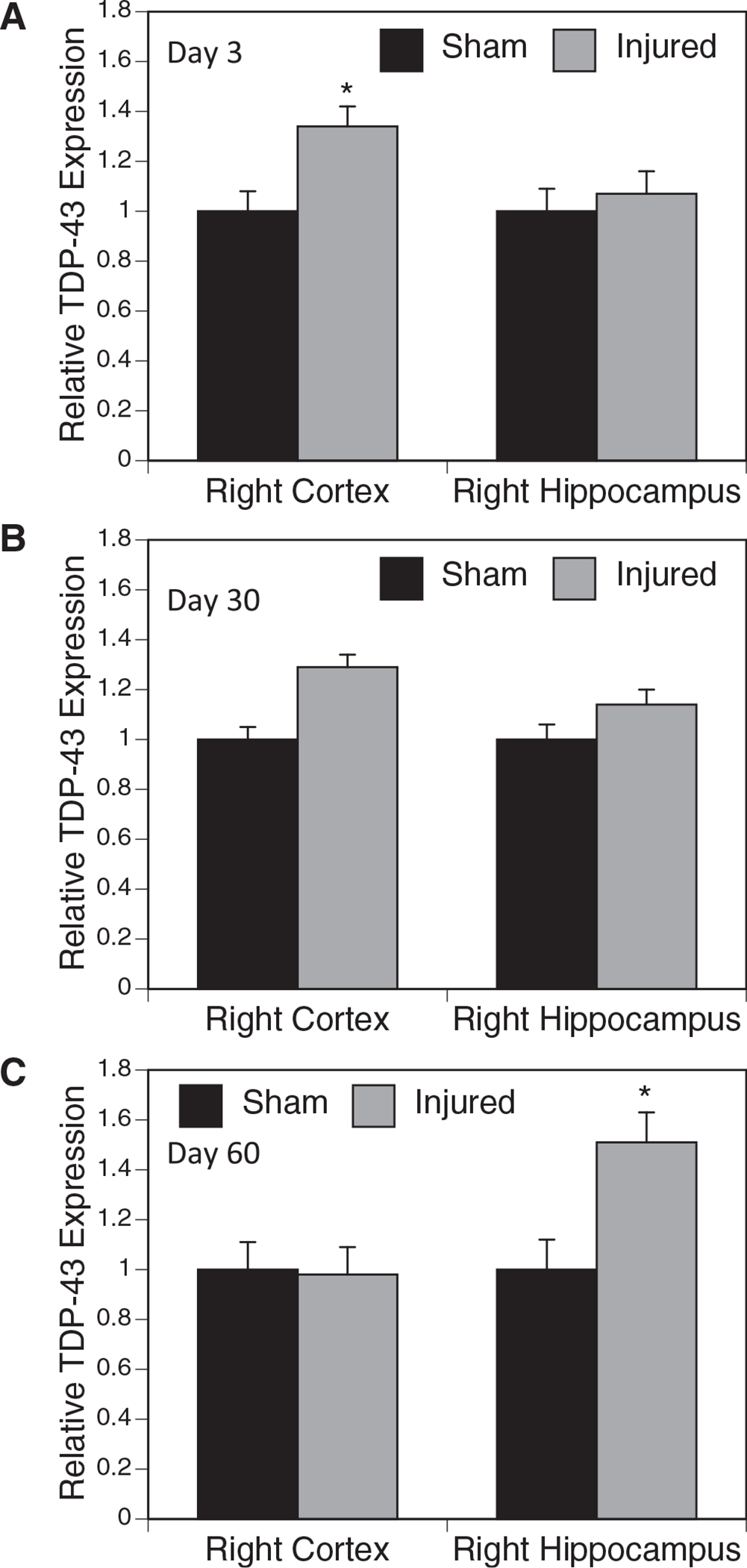

TDP-43 expression after 5 × head injury at 30 and 60 days

One characteristic of chronic traumatic encephalopathy pathology is an increase in TDP-43 expression in the brain. In these studies, we measured via Western blot TDP-43 protein expression in the cortex and hippocampus at three, 30, and 60 days after the last of five repetitive, 30 g injuries. In the ipsilateral cortex, we found relative TDP-43 expression to be increased at three days (Fig. 3A) (p = 0.022), still elevated—although not significantly—at 30 days (Fig. 3B), and returned to sham levels by 60 days (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, as TDP-43 protein levels were decreasing between 30–60 days in the cortex, in the ipsilateral hippocampus an increased expression on TDP-43 was not seen until 60 days after injury (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Transactivation response deoxyribonucleic acid protein 43 (TDP-43) expression after 5 × injury. The TDP-43 expression was analyzed via Western blot following 5 × injury or sham at three, 30, and 60 days after the final injury in the hippocampus and cortex of the ipsilateral hemisphere. Expression was normalized to β-actin. At three days post-injury, a significant increase in TDP-43 expression was observed in the cortex (A). The TDP-43 levels in the cortex were still elevated, but not significantly, at 30 days (B). At 60 days, TDP-43 expression in the hippocampus was significantly increased, but not in the cortex (C) (n = 5) (*p < 0.05).

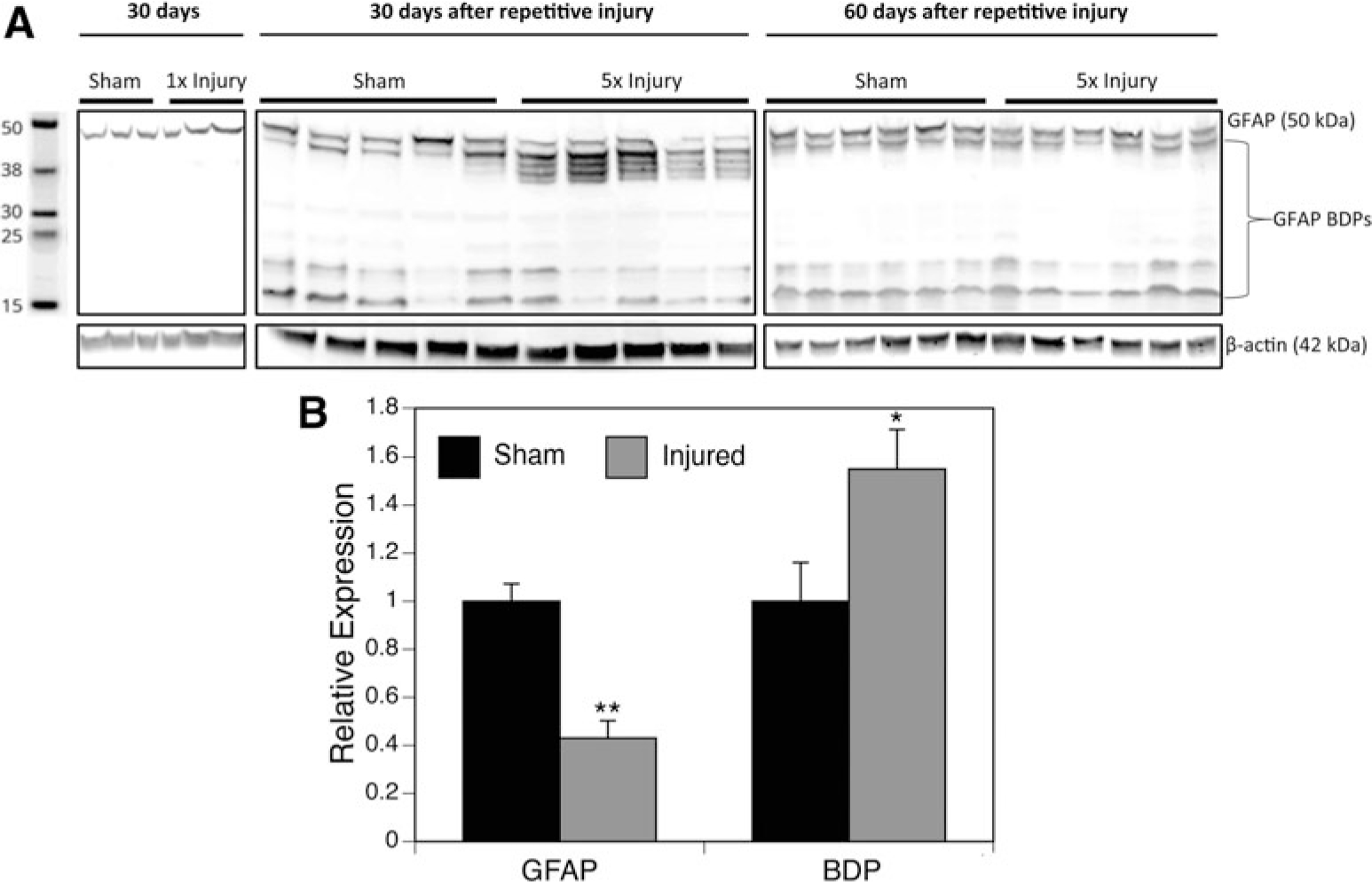

GFAP

Head injury results in many biochemical changes that contribute to neuronal and astrocytic loss. Some of these protein alterations that are being identified can also be used as tools to characterize an injury. One protein that is known to change after injury is GFAP, and we examined this at the longer time points. This protein increases in expression and converts to breakdown products after injury.30 We identified a decrease in GFAP expression of the full-length product, normalized to β-actin (p = 0.008), and a significant increase in the breakdown products (p = 0.027) 30 days post-injury in the cortex (Fig. 4). No significant differences were observed in the hippocampus (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) expression after injury. The GFAP expression and breakdown products from the ipsilateral cortex were analyzed at 30 and 60 days after final injury and are shown by (A) Western blot (inverted from fluorescent image) and (B) relative protein levels of GFAP and breakdown products (BDP), normalized to β-actin. Injured mice had a significant decrease in GFAP expression with a subsequent increase in breakdown products when compared with sham mice (*p < 0.05, n = 5).

Expression of autophagy factors

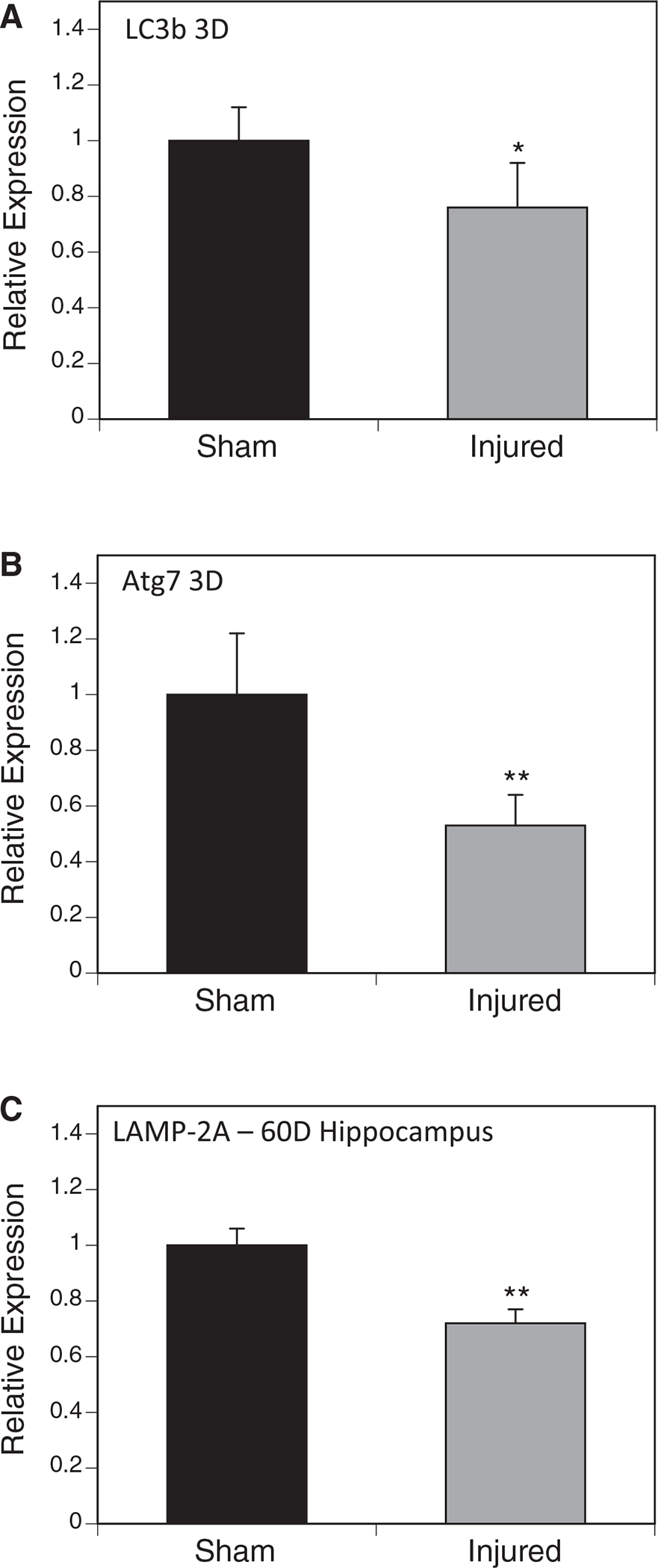

To determine whether the protein level that we observed was the result of a reduction in protein processing events, we measured the autophagy markers microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain-3 (LC3) and ubiquitin-like-modifier-activating-enzyme 7 (Atg7). We found a decrease in protein expression of both LC3 (Fig. 5A) and ATG7 (Fig. 5B) three days after the last injury in the right cortex.

FIG. 5.

Expression of autophagy factors. Western blots were performed on mouse brain samples using antibodies specific to several autophagy factors and normalized to β-actin. Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain-3 (LC3B) (A) and ubiquitin-like-modifier-activating-enzyme 7 (Atg7) (B) were found to be significantly decreased in the injured group compared with the sham group three days after injury. The lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A (LAMP-2A) (C) was examined in the ipsilateral hippocampus and was also found to be reduced 60 after injury (*p < 0.05, n = 5–6).

In addition, we measured expression of lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A (LAMP-2A), a limiting factor in chaperone-mediated autophagy at three, 30, and 60 days post-injury (Fig. 5C). Contrary to our results with macroautophagy factors, we found no difference in LAMP-2A three days post-injury but found a decrease 60 days post-injury in 5 × injured right hippocampi compared with sham controls by Western blotting normalized to β-actin. No differences were identified in mRNA (data not shown).

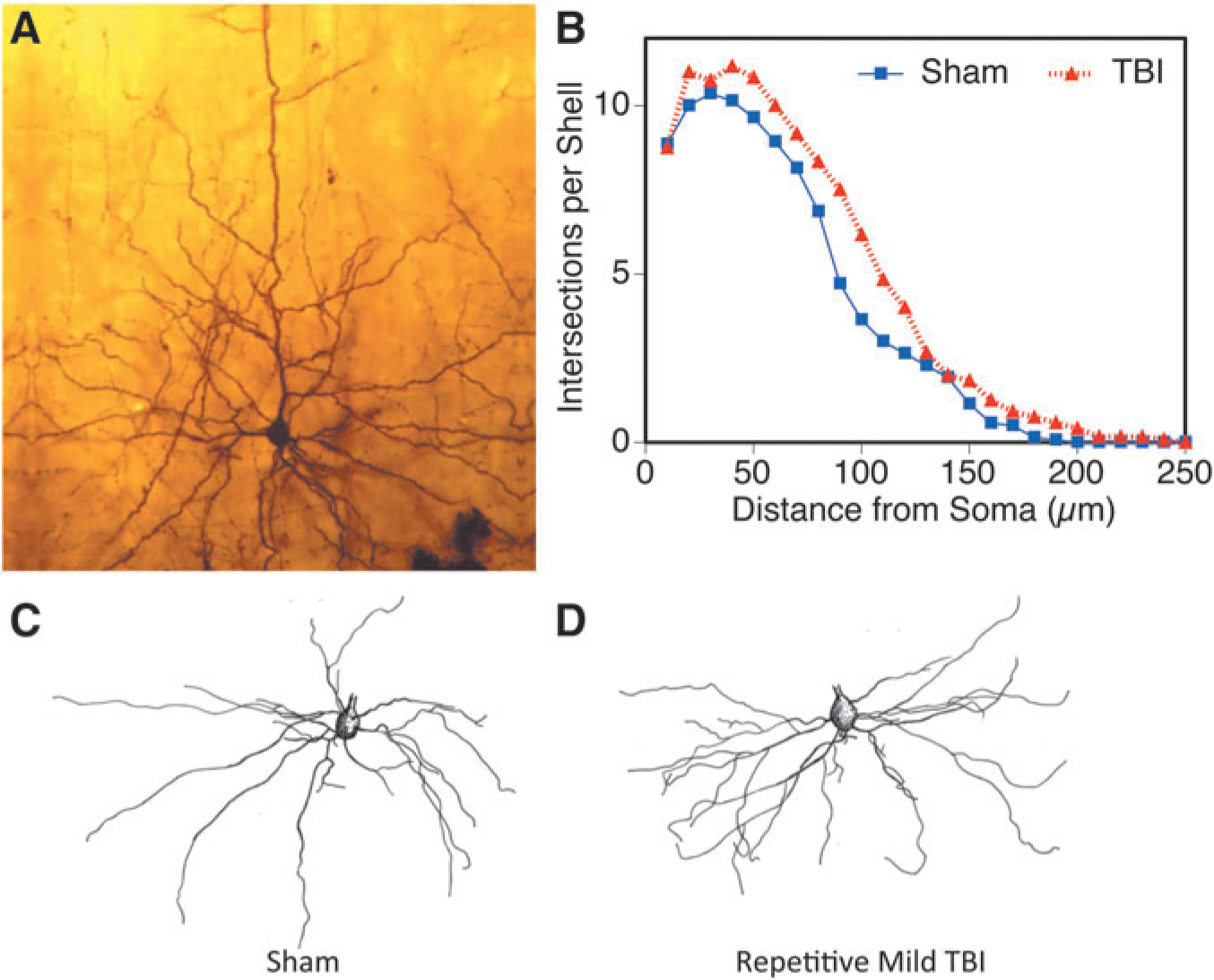

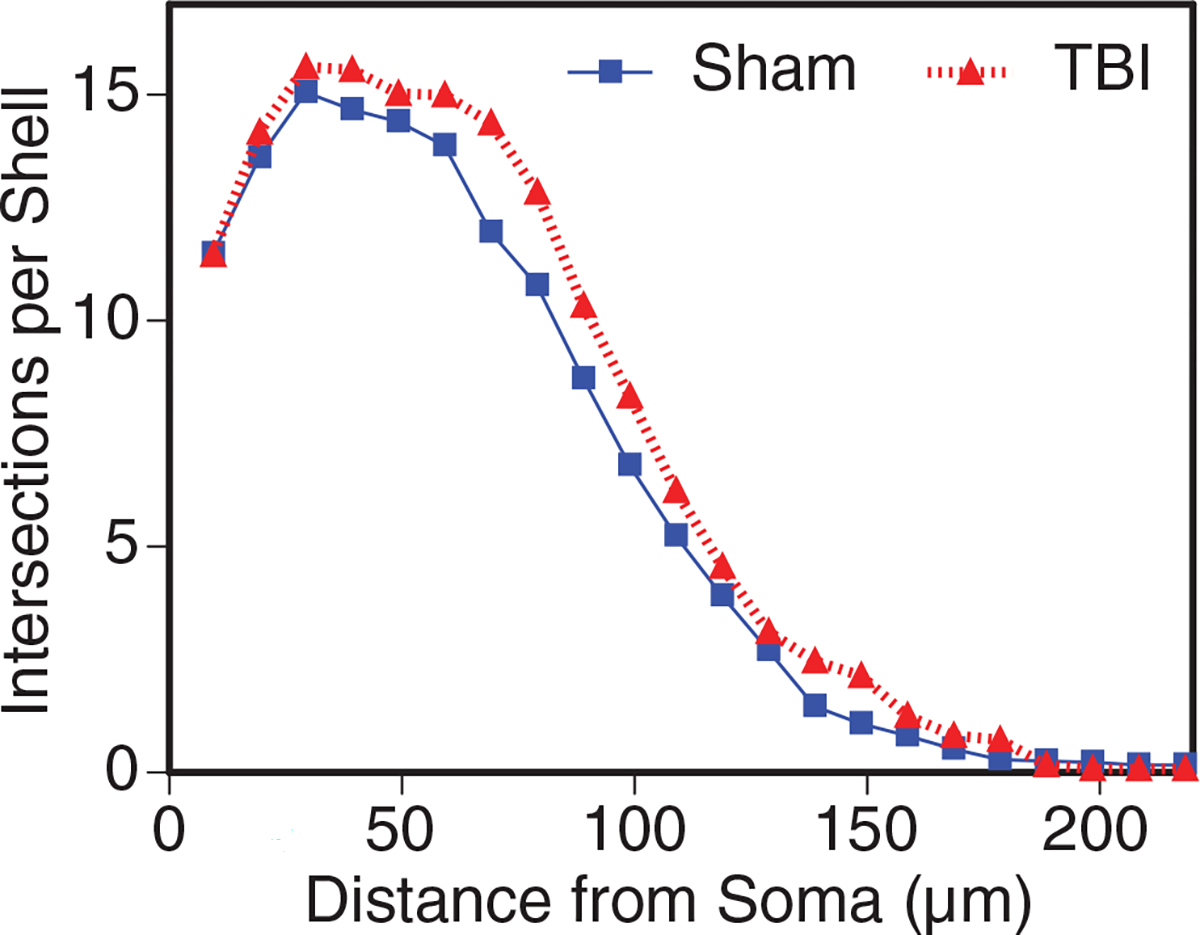

Dendritic branching and complexity in the parietal cortex

We measured dendritic parameters (Sholl analysis and complexity) 30 days post-injury in 5 × injured (Fig. 6D) and sham control animals (Fig. 6A, 6C). There were three subjects per group, and from each subject seven layer V pyramidal neurons were randomly selected for dendritic analysis of the basilar tree (dendrites originating from the base of the soma) extending laterally and inferiorly into cortical layers V and VI in a conical distribution. Golgi staining and subsequent Sholl analysis31,32 on the layer V pyramidal neurons of the outer half of the parietal cortex showed a significant increase in dendritic branching in animals that underwent 5 × mild TBI (Fig. 6B, p = 0.0001). The basilar tree of neurons from the 5 × TBI group displayed approximately 21% more dendritic length than those from the sham controls.

FIG. 6.

Sholl intersections were found higher in the 5 × injured cortex. Layer V pyramidal neurons from the parietal cortex are shown from sham (A, C) and injured (D) in an example micrograph (A) and camera lucida drawings (C, D). The distribution of Sholl intersections (B) indicated greater dendritic branch material found after injury (*p = 0.0031). TBI, traumatic brain injury.

With respect to the complexity of the dendritic arbor, there is more complexity (e.g., more branch points) in the proximal portion of the dendritic arbor (e.g., at first and second branch orders—those closest to the cell body), whereas the more distal branch orders show little or no difference between the two groups with respect to the numbers of branch points (data not shown).

In sum, the dendritic branching data on the layer V pyramidal neurons of the parietal cortex demonstrate that the repeated TBI events resulted in a significant increase in the amount of dendritic material in the basilar tree. Further, it suggests that dendritic complexity is also increased in the branching more proximal to the soma. Finally, these characteristics are most pronounced in the lateral parietal cortex—the region closest to the TBI impact zone.

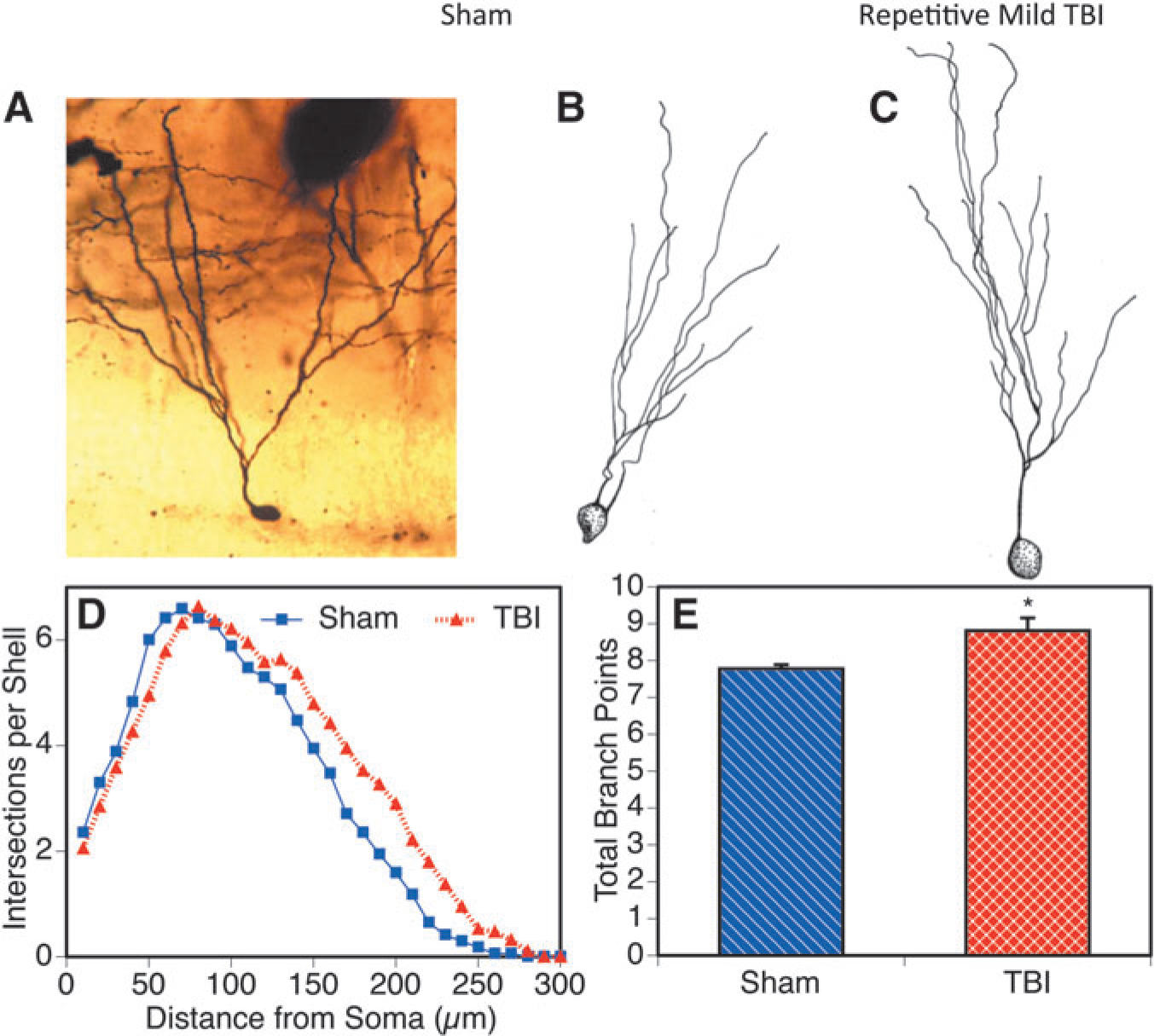

Dendritic arbors in the granule cells of the hippocampal dentate gyrus

In addition, we examined the granule cell neurons of the hippocampal dentate gyrus—an area known to be sensitive to injury.5 Assessment of randomly selected Golgi stained granule cells from 5 × injured (Fig. 7C) and sham controls (Fig. 7A, 7B) were used to perform Sholl analysis. The Sholl analysis of the granule cells of the dentate gyrus (Fig. 7D) showed that for the neurons from the 5 × TBI group, the outer (distal) 70% of the dendritic arbor had significantly more branching material than the sham controls (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.0001). For the entire neuron, this amounted to approximately a 12% increase. There was no significant change in the proximal portion of the arbor. Complexity of the dendritic arbor of the granule cells was also significantly increased in the 5 × TBI group based on the increase in the number of branch points (e.g., bifurcations of the branches) in the dendritic arbor (Fig. 7E).

FIG. 7.

The hippocampus also displayed neurons with more dendritic branch material after the repetitive mild traumatic brain injury (TBI). Granule cells from the dentate gyrus are shown after sham (A, B) or 5 × mild injury (C) in a micrograph (A) and camera lucida drawings (B, C). More dendritic branching was reflected by higher numbers of intersections of the dendritic tree with a series of concentric circles of enlarging diameters on the Sholl template (D) at 80 or greater microns from the soma (*p < 0.0001). Increased complexity of the dendritic arbor of the granule cells was reflected by greater numbers of dendritic branch points in that phase of the analysis (E; *p < 0.05).

Overall, both hippocampal granule cells and layer V pyramidal neurons of the lateral parietal cortex showed common findings—that the 5 × TBI injury resulted in an increase in both dendritic branch material and in the tendency to increase the complexity of those branches.

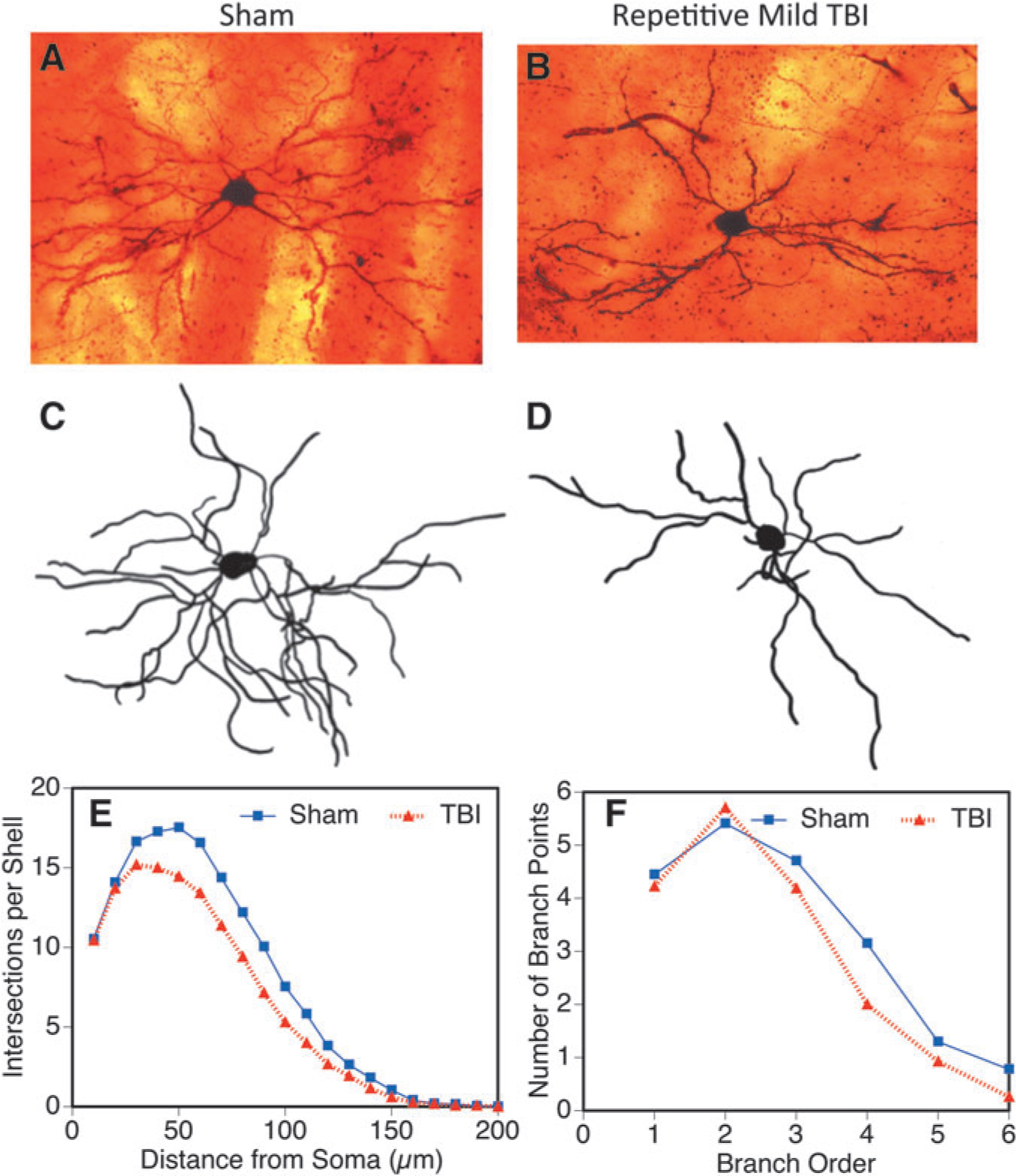

Dendritic structures in the striatal medium spiny neurons

We also explored dendritic complexity in the striatal medium spiny neurons from 5 × injured (Fig. 8B, 8D) and sham control (Fig. 8A, 8C). Contrary to what we observed in the hippocampus and cortex, the Sholl analysis of the striatal neurons revealed an 18% decrease in dendritic branch material (Fig. 8E) (Wilcoxon test, p < 0.001). This decrease was seen to be widespread throughout the extent of the dendritic arbor. There was also a reduction in the number of times that dendrites branched (Fig. 8F). This was seen particularly in the more distal branch orders of the striatal tree.

FIG. 8.

Dendritic complexity in the striatal medium spiny neurons 5 × closed head injury 30 days post-injury (*p < 0.05). Example neurons are shown in micrographs (A, B) and camera lucida drawings (C, D) from sham and repetitive injured brains. The dendritic arbor was evaluated by Sholl (E) and branch point analysis (F) and showed reduced total dendritic branch material (Sholl analysis) and arbor complexity (branch point analysis) in this region after injury (*p < 0.05). TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Dendritic complexity after 1 × injury

To determine whether this increase was specific to 5 × injury, it was compared with a single injury. Animals underwent a single 30 g injury, and Golgi staining was performed 30 days post-injury on 1 × injured and sham controls. Similar to 5 × injury, when mice underwent 1 × injury, we found an increase in dendritic complexity in injured animals compared with sham controls (Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

Dendritic complexity in 1x closed head injury 30 days post injury. Sholl analysis indicated that pyramidal neurons in layer V closest to the injury displayed significantly larger and more complex dendritic arbors (*p < 0.05, analysis of variance, Bonferroni multiple comparison test). TBI, traumatic brain injury.

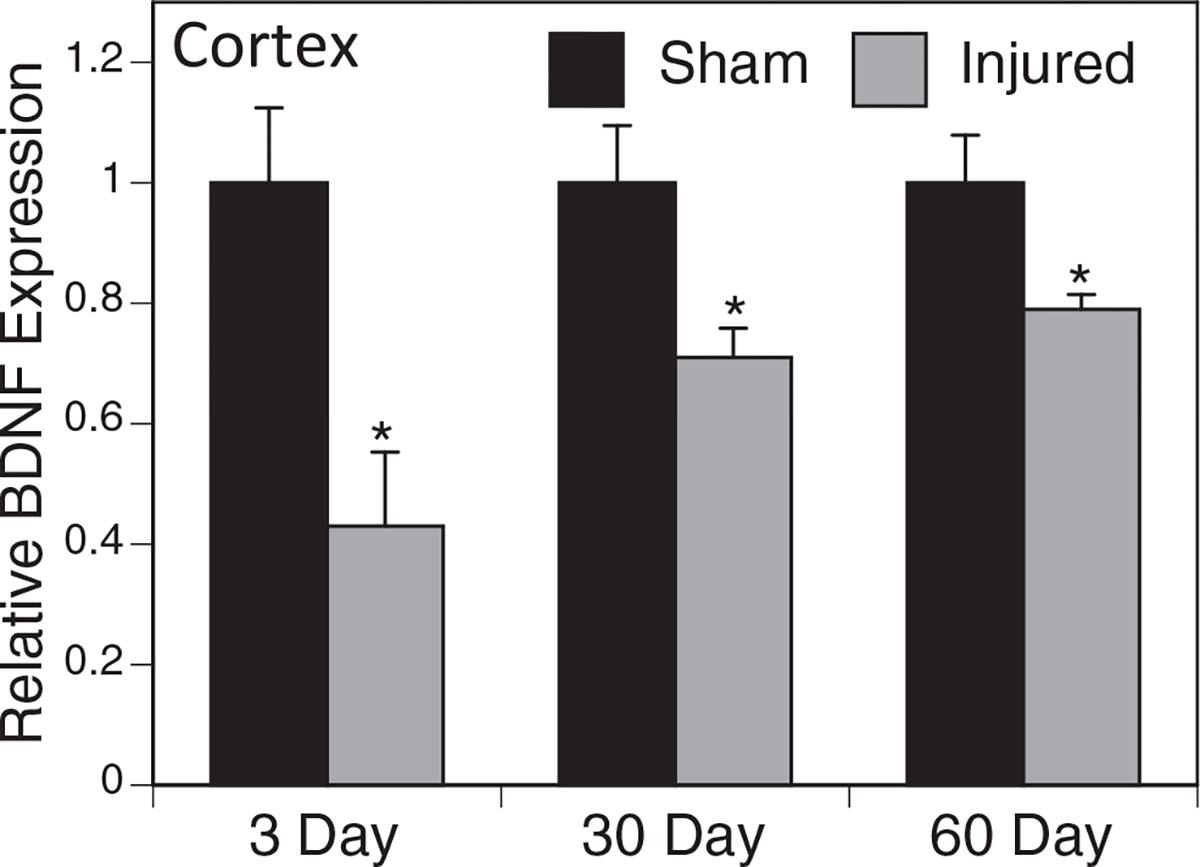

Expression of neurotrophic factors

To explore factors that may contribute to the differences that we found in dendritic complexity, we measured several known neurotrophic factors in the hippocampus and cortex. We found a significant decrease in mature BDNF at three, 30, and 60 days post-injury (p = 0.027, 0.034. 0.047, respectively) in the 5 × injured cortex compared with sham controls (Fig. 10), but found no significant difference in the hippocampus (data not shown). We found no difference in netrin-1 and NGF. No statistically significant differences were observed in mRNA expression (data not shown).

FIG. 10.

Mature bone derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein expression in the cortex. Western blots were performed using an antibody specific to mature BDNF and normalized to β-actin. Relative expression of mature BDNF was significantly decreased at three, 30, and 60 days in the ipsilateral cortex obtained from injured mice when compared with sham mice. Data shown represent relative expression when compared with the sham mice at each corresponding time point. (*p < 0.05, n = 5).

Discussion

Head injuries have become a major public health problem. It is now estimated that mild TBI affects approximately 42 million people worldwide each year.33 In particular, repeated injuries to the brain are a hallmark injury of our military members and athletes and produce a distinct set of molecular responses that have yet to be understood fully. Chronic problems in behavioral and biochemical parameters have also been reported in a similar closed head repetitive model with mice.34 Increasing evidence indicates that repetitive injuries, including sports injuries, can result in long-term deficits and contribute to the development of neurodegenerative disease.35–38 In our study, we have reproduced the effects of multiple mild TBIs in a mouse model to better understand the molecular mechanisms by which the brain responds to injury.

Our model of 5 × injury was mild enough to have no lasting impact on motor function, as demonstrated by the rotarod testing, performed after any short-term transient deficits would occur, but displayed changes in gene expression and dendritic complexity. We found that TDP-43, frequently associated with neurodegeneration, was upregulated early in the cortex at three days after repetitive injury. In the hippocampus, TDP-43 was increased at 60 days post 5 × injury. When mice received a single injury, we found that TDP-43 can also be upregulated, although this was at 12 days post-injury. The 50 g weight drop was not used in the 5 × injury model, because this may have resulted in too severe of an injury. Difference in expression at the different time points and in the cortex versus hippocampus suggests that TDP-43 undergoes an altered spatial and temporal expression pattern and raises questions about regional susceptibility. Nonetheless, it does identify that TDP-43 expression is increased in a mouse model of closed head injury.

One plausible mechanism for the increase in TDP-43 expression is a decrease in autophagy. Three days after the last injury, we observed a significant decrease in both LC3b and Atg7 in 5 × injured versus control, suggesting that 5 × injury results in decreased macroautophagy. In addition, we observed a significant decrease in LAMP-2A, the limiting factor in chaperone-mediated autophagy, 60 days after injury in the hippocampus. While TDP-43 is not broken down via chaperone-mediated autophagy, altered levels of this pathway could contribute to its status—namely, a decrease in chaperone-mediated autophagy could result in increased tau accumulation, which may hinder the clearance of TDP-43.

In addition to displaying TDP-43 pathology, the 5 × injury model also resulted in GFAP breakdown products. The sizes, 42, 40, and 38 kDa, may indicate a pathway involving calpain-2.30 This can be a marker for injury; however, there were also breakdown products present in the 5 × sham controls. This may have been caused by the five exposures of anesthesia.39

Newer imaging technology shows that patients with mild head injuries have not only neuronal loss, but also damaged neuronal connections. This loss of neuronal connectivity may be a major contributor to symptoms.40–42 We examined the amount of dendritic branch material and branching complexity in our model and anticipated a decrease in dendritic complexity in 5 × injured brains compared with sham controls as we observed in in vitro experiments.43 While we saw this in the striatum medium spiny neurons, we did not see this in either the layer V pyramidal neurons of the parietal cortex or the granule cells of the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Similar increases in Sholl intersections have been reported at several time points after fluid percussion injury in the rat amygdala,44 and it was noted that the structural alterations could be involved with behavioral problems that occur after injury.

This increase in dendritic branching after injury in the cortex and hippocampus may be because of compensatory dendritic hypertrophy where neurons increase complexity after injury as part of a recovery response. We did see a decrease in BDNF levels in injured cortex, however, when compared to sham controls, suggesting that compensatory hypertrophy is not predominant and that selective loss is likely involved. Neurons that were less complex, and less connected, may have been lost after injury, and the survival of the remaining neurons favored the more fit, more complex neurons. Further studies will be necessary to confirm whether this is the case.

Region specific differences (e.g., 5 × TBI-related increase of branching in cortex and hippocampus vis-á-vis loss in striatal neurons) could be because of differential neuronal mechanisms and sensitivity that require further research. For example, the layer V pyramidal neurons receive inputs from the thalamus and cortico-cortical circuitry and the contralateral hemisphere while the striatum receives inputs from the cerebral cortex; it is unknown as yet whether this, or differential energy, glutamate, or calcium metabolism could play a role in the region specific injury-induced changes seen in the dendritic complexity.

Using our mouse model of repetitive mTBI, we have determined, at different time points, certain effects on the levels of proteins associated with neurodegeneration, including autophagy factors, after repetitive head injury in a mouse model. We have demonstrated an increase in TDP-43 in response to injury as well as a decrease in autophagy factors, which could affect proteins within the cell after injury. This elevated amount of TDP-43 in response to multiple injuries could be a contributing factor to the long-term cognitive deficits that are found in those with TBI.

In addition, we characterized repetitive injury-induced changes for an aspect of connectivity by measuring dendritic branching. We showed an increase in dendritic complexity that warrants further investigation to see whether it could be the result of selective loss of less complex neurons as a result of the injury. Overall, this model of repetitive injury produces neuropathology and shares aspects of human traumatic brain injuries. Further study of this murine model will help us to better understand the molecular mechanisms of repeated brain injuries and identify potential biomarkers or targets for treatments to reduce or eliminate degenerative effects.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Smith for expert animal assistance and Sonya Bhaskar for expert technical assistance. This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs (Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development (I01RX001520)), the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Congressionally Directed Gulf War Illness Research Program (W81XWH-16-1-0626), the Florida Department of Health James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program (4KB14), and The Bay Pines Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government and the opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.

References

- 1.Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, and Castro CA (2008). Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N. Engl. J. Med 358, 453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell JW and Barber-Foss KD (1999). Traumatic brain injury in high school athletes. JAMA 282, 958–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDowell S, Whyte J and D’Esposito M (1997). Working memory impairments in traumatic brain injury: evidence from a dual-task paradigm. Neuropsychologia 35, 1341–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stuss D, Ely P, Hugenholtz H, Richard M, LaRochelle S, Poirier C, and Bell I (1985). Subtle neuropsychological deficits in patients with good recovery after closed head injury. Neurosurgery 17, 41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hicks RR, Smith DH, Lowenstein DH, Saint Marie R, and McIntosh TK (1993). Mild experimental brain injury in the rat induces cognitive deficits associated with regional neuronal loss in the hippocampus. J. Neurotrauma 10, 405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zohar O, Schreiber S, Getslev V, Schwartz JP, Mullins PG, and Pick CG (2003). Closed-head minimal traumatic brain injury produces long-term cognitive deficits in mice. Neuroscience 118, 949–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terrio H, Brenner LA, Ivins BJ, Cho JM, Helmick K, Schwab K, Scally K, Bretthauer R, and Warden D (2009). Traumatic brain injury screening: preliminary findings in a US Army Brigade Combat Team. J. Head Trauma Rehabil 24, 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneiderman AI, Braver ER, and Kang HK (2008). Understanding sequelae of injury mechanisms and mild traumatic brain injury incurred during the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan: persistent postconcussive symptoms and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Epidemiol 167, 1446–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCrea M, Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Barr W, Randolph C, Cantu RC, Onate JA, Yang J, and Kelly JP (2003). Acute effects and recovery time following concussion in collegiate football players: the NCAA Concussion Study. JAMA 290, 2556–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iverson GL (2005). Outcome from mild traumatic brain injury. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 18, 301–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, Daneshvar DH, Lee HS, Wojtowicz SM, Hall G, Baugh CM, Riley DO, Kubilus CA, Cormier KA, Jacobs MA, Martin BR, Abraham CR, Ikezu T, Reichard RR, Wolozin BL, Budson AE, Goldstein LE, Kowall NW, and Cantu RC. (2013). The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 136, 43–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, McCluskey LF, Miller BL, Masliah E, Mackenzie IR, Feldman H, Feiden W, Kretzschmar HA, Trojanowski JQ, and Lee VM (2006). Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science 314, 130–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tremblay C, St-Amour I, Schneider J, Bennett DA, and Calon F (2011). Accumulation of transactive response DNA binding protein 43 in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 70, 788–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, Santini VE, Lee HS, Kubilus CA, and Stern RA (2009). Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 68, 709–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkins BE, Krishnamurthy S, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Prough DS, Jackson GR, DeWitt DS, and Kayed R (2013). Rapid accumulation of endogenous tau oligomers in a rat model of traumatic brain injury: possible link between traumatic brain injury and sporadic tauopathies. J. Biol. Chem 288, 17042–17050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson RS, Yu L, Trojanowski JQ, Chen EY, Boyle PA, Bennett DA, and Schneider JA (2013). TDP-43 pathology, cognitive decline, and dementia in old age. JAMA Neurol 70, 1418–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuervo AM and Wong E (2014). Chaperone-mediated autophagy: roles in disease and aging. Cell Res. 24, 92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jinwal UK, Abisambra JF, Zhang J, Dharia S, O’Leary JC, Patel T, Braswell K, Jani T, Gestwicki JE, and Dickey CA (2012). Cdc37/Hsp90 protein complex disruption triggers an autophagic clearance cascade for TDP-43 protein. J. Biol. Chem 287, 24814–24820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CC, Bose JK, Majumder P, Lee KH, Huang JT, Huang JK, and Shen CK (2014). Metabolism and mis-metabolism of the neuropathological signature protein TDP-43. J. Cell Sci 127, 3024–3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Fan H, Ying Z, Li B, Wang H, and Wang G (2010). Degradation of TDP-43 and its pathogenic form by autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Neurosci. Lett 469, 112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bose JK, Huang CC, and Shen CK (2011). Regulation of autophagy by neuropathological protein TDP-43. J. Biol. Chem 286, 44441–44448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milman A, Rosenberg A, Weizman R, and Pick CG (2005). Mild traumatic brain injury induces persistent cognitive deficits and behavioral disturbances in mice. J. Neurotrauma 22, 1003–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heim LR, Badar M, Edut S, Rachmany L, Baratz-Goldstein R, Lin R, Elpaz A, Qubty D, Bikovski L, Rubovitch V, Schreiber S, and Pick CG (2017). The invisibility of mild traumatic brain injury: impaired cognitive performance as a silent symptom. J. Neurotrauma Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tashlykov V, Katz Y, Gazit V, Zohar O, Schreiber S, and Pick CG (2007). Apoptotic changes in the cortex and hippocampus following minimal brain trauma in mice. Brain Res. 1130, 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saykally JN, Rachmany L, Hatic H, Shaer A, Rubovitch V, Pick CG, and Citron BA (2012). The nuclear factor erythroid 2-like 2 activator, tert-butylhydroquinone, improves cognitive performance in mice after mild traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience 223, 305–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tweedie D, Milman A, Holloway HW, Li Y, Harvey BK, Shen H, Pistell PJ, Lahiri DK, Hoffer BJ, Wang Y, Pick CG, and Greig NH (2007). Apoptotic and behavioral sequelae of mild brain trauma in mice. J. Neurosci. Res 85, 805–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diamond DM, Campbell AM, Park CR, Woodson JC, Conrad CD, Bachstetter AD, and Mervis RF (2006). Influence of predator stress on the consolidation versus retrieval of long-term spatial memory and hippocampal spinogenesis. Hippocampus 16, 571–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paxinos G and Franklin KB (2012). The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4th ed. Academic Press: Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang YJ, Xu YF, Cook C, Gendron TF, Roettges P, Link CD, Lin WL, Tong J, Castanedes-Casey M, Ash P, Gass J, Rangachari V, Buratti E, Baralle F, Golde TE, Dickson DW and Petrucelli L (2009). Aberrant cleavage of TDP-43 enhances aggregation and cellular toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 7607–7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoltewicz JS, Scharf D, Yang B, Chawla A, Newsom KJ, and Fang L (2012). Characterization of antibodies that detect human GFAP after traumatic brain injury. Biomark. Insights 7, 71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sholl DA (1953). Dendritic organization in the neurons of the visual and motor cortices of the cat. J. Anat 87, 387–406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Segura LM and Perez-Marquez J (2014). A new mathematical function to evaluate neuronal morphology using the Sholl analysis. J. Neurosci. Meth 226, 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gardner RC and Yaffe K (2015). Epidemiology of mild traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative disease. Mol. Cell Neurosci 66, 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mannix R, Berkner J, Mei Z, Alcon S, Hashim J, Robinson S, Jantzie L, Meehan WP 3rd, and Qiu J (2017). Adolescent mice demonstrate a distinct pattern of injury after repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 34, 495–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldman SM, Tanner CM, Oakes D, Bhudhikanok GS, Gupta A, and Langston JW (2006). Head injury and Parkinson’s disease risk in twins. Ann. Neurol 60, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen H, Richard M, Sandler DP, Umbach DM, and Kamel F (2007). Head injury and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am. J. Epidemiol 166, 810–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehman EJ, Hein MJ, Baron SL, and Gersic CM (2012). Neurodegenerative causes of death among retired National Football League players. Neurology 79, 1970–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guskiewicz KM, Marshall SW, Bailes J, McCrea M, Cantu RC, Randolph C, and Jordan BD (2005). Association between recurrent concussion and late-life cognitive impairment in retired professional football players. Neurosurgery 57, 719–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dallasen RM, Bowman JD, and Xu Y (2011). Isoflurane does not cause neuroapoptosis but reduces astroglial processes in young adult mice. Med. Gas Res 1, 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rafols JA, Morgan R, Kallakuri S, and Kreipke CW (2007). Extent of nerve cell injury in Marmarou’s model compared to other brain trauma models. Neurol. Res 29, 348–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheff S, Price D, Hicks R, Baldwin S, Robinson S, and Brackney C (2005). Synaptogenesis in the hippocampal CA1 field following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 22, 719–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Semchenko V, Bogolepov N, Stepanov S, Maksimishin S, and Khizhnyak A (2006). Synaptic plasticity of the neocortex of white rats with diffuse-focal brain injuries. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol 36, 613–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hatic H, Kane MJ, Saykally JN, and Citron BA (2012). Modulation of transcription factor Nrf2 in an in vitro model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 29, 1188–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffman AN, Paode PR, May HG, Ortiz JB, Kemmou S, Lifshitz J, Conrad CD, and Currier Thomas T (2017). Early and persistent dendritic hypertrophy in the basolateral amygdala following experimental diffuse traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 34, 213–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]