Abstract

Disparities exist in post-disaster flooding exposure and vulnerable populations bear a disproportionate impact of this exposure. We describe the unequal burden of flooding in a cohort of New York residents following Hurricane Sandy and assess whether the likelihood of flooding was distributed equally according to socioeconomic demographics, and whether this likelihood differed when analyzing self-reported or FEMA flood exposure measures. Residents of New York City and Long Island completed a self-administered survey 1.5–4.0 years after the storm. Multivariable logistic regressions were performed to determine the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and flood exposure. Participants (n=1231) residing in areas of the lowest two quartiles of median household income experienced flooding the most often (FEMA/self-reported: < $40,298: 65.3%/42.0%, $40,298 - $67,188: 43.3%/32.1%) and these areas contained the highest proportions of non-white participants (< $40,298: 39.1%, $40,298 - $67,188: 36.6%) and those with < high school education (< $40,298: 35.5%, $40,298 - $67,188: 33.6%). Both self-report (p < 0.05) and FEMA (p < 0.05) flood measures indicated that older participants were more likely to live in a household exposed to flooding, while those living in higher income areas had decreased likelihood of flooding (p < 0.0001). Socioeconomic and age disparities were present in exposure to flooding during Hurricane Sandy. Future disaster preparedness responses must understand flooding from an environmental justice perspective to create effective strategies that minimize disproportionate exposure and its adverse outcomes.

Keywords: Flooding, disparities, environmental justice

Introduction

An environmental justice approach to natural disasters aims to determine if specific disadvantaged populations bear a disproportionate impact of the event1,2. Research has commented that racial/ethnic minorities and lower-income populations are more likely to live in close proximity to environmental hazards3,4 and that this is likely to result in a disproportionate impact of the exposure in these populations3,5. After Hurricane Katrina, research identified that Black and low-income residents of New Orleans were exposed to a disproportionate amount of flooding, displacement from their homes, and long-term mental health concerns6–10. After Hurricane Harvey, non-Hispanic Black and socioeconomically deprived residents faced a higher burden of flood exposure, suggesting that racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities existed5. In addition to identifying vulnerable populations and risk factors for exposure, disaster preparedness efforts must identify these disparities in order to appropriately address the consequences of a traumatic event. Here we describe the unequal burden of flooding in a cohort of New York residents following Hurricane Sandy. The objective of this analysis was to determine whether the likelihood of flooding was distributed equally in the study sample according to demographics, with a particular focus on median household income, and whether this likelihood differed when studying self-reported flood exposure or (Federal Emergency Management Agency) FEMA flood exposure measures.

Methods

Participants

The full study methodology has been described previously11; residents of Long Island, Queens, and Staten Island who lived in areas ranging from mildly to heavily affected by Hurricane Sandy consented and completed a self-administered survey 1.5–4.0 years after the storm. While convenience sampling was utilized for recruitment, demographic characteristics of study participants were consistently compared to the demographic distribution of the county assessed from census data, and adjustment in recruitment strategies was performed when the comparability of the study sample to the distribution of residents living in that location was not met11. At the end of recruitment, the recruited population was congruous to the 2010 census data for the sampled geographies11. Approval for this study was given by the institutional review board of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research at Northwell Health and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Survey Variables

The survey queried demographics, hurricane exposure, and medical/behavioral health status, including questions regarding their mental health history before and after Hurricane Sandy. Participants also recorded if they experienced flooding (yes/no) at their residence during Hurricane Sandy, and if they resided in an apartment building (yes/no). Participant addresses lived in during Hurricane Sandy were then geocoded as previously described11. Median household income for 2012 at the zip code tabulation area (ZCTA) level was downloaded from American Community Survey 5-year estimates12, and each participant was assigned a median household income value for the ZCTA they resided in during Hurricane Sandy.

Outcome Variables

Two binary measures of flood exposure were considered in the current analysis. Survey values on flood exposure (yes/no) was used to define self-reported exposure while flood data from the FEMA Modeling Task Force Hurricane Sandy Impact Analysis was utilized to provide a comparative measure of flood exposure13. Geocoded addresses for each participant were assigned a binary flood value (yes/no) according to FEMA data.

Statistical analysis

Univariate comparisons in FEMA and self-reported flood exposures and in median household income according to dichotomized study variables were performed using Chi-square tests. Associations between demographic variables and flood exposure were investigated using multivariate logistic regression, adjusting for the following covariates: age (quartiles 18‒27, 28–45, 46‒58, and 58+ years), race (White, non-White), education (≤ high school, > high school completed), existing mental health conditions prior to Hurricane Sandy (yes/no), living in an apartment during Hurricane Sandy (yes/no), and median household income according to 2012 US ZCTAs (quartiles < $40,298, $40,298 - $67,188, $67,189 - $89,684, and > $89,684). Existing mental health conditions was defined as reporting at least one of the following mental health issues: anxiety disorder, depression, Post-traumatic stress disorder PTSD, Schizophrenia, bipolar, substance/alcohol abuse, substance/prescription abuse, or other mental health problems. All significant findings are reported at the level of p < 0.05 or p < 0.001. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Code for analyses can be made available by contacting the corresponding author.

Results

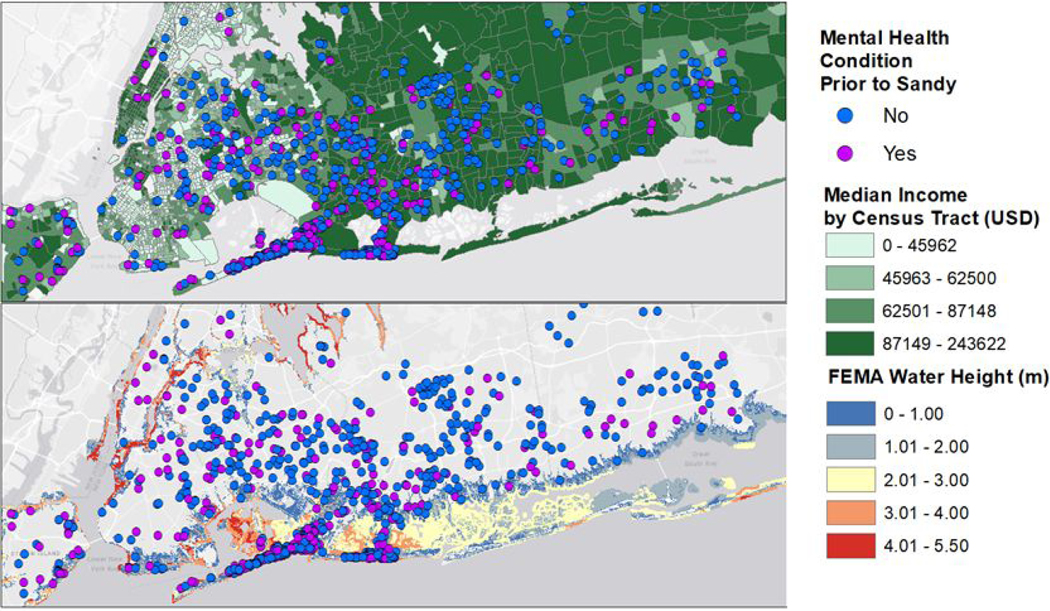

Participants (n = 1,231) were sampled from areas of varying median household incomes and flood exposure across New York City and Long Island (Figure 1). At univariate analysis, the lowest two income quartiles contained a disproportionate number of those who experienced flooding in both self-reported (< $40,298 income quartile: 65.3% experienced flooding; $40,298- $67,188: 43.3%; $67,189-$89,684: 29.2%; > $89,684: 12.7%; p < 0.0001) and FEMA measures (< $40,298: 42.0; $40,298-$67,188: 32.1%; $67,189-$89,684: 31.3%; > $89,684: 18.4%; p < 0.0001; Table 1). Non-white participants were more likely to experience flooding (45.2%) than White participants (36.3%) according to the FEMA measure (p = 0.0017). Older adults, including those aged 46–58 years, were the largest group experiencing flooding under both measures (Table 1). A greater proportion of participants with an existing mental health condition prior to Hurricane Sandy self-reported flooding compared to those not reporting an existing mental health condition (38.0% vs 28.9%, p = 0.0010), as well as experienced flooding according to the FEMA measure (47.0% vs 36.7%, p = 0.0004).A greater proportion of those with ≤ high school education (50.8%) compared to those with > high school education (33.6%) were more likely to experience flooding using the FEMA measure p < 0.0001). This difference was not reported for those self-reporting flooding: 33.8% of participants with < high school education reported flooding and 31.2% of participants with > high school education reported flooding (p = 0.3496).

Figure 1:

Distribution of participants (n=1,231) according to the presence of mental health conditions prior to Hurricane Sandy and income (top) or FEMA flood exposure (bottom) across New York City and Long Island.

Data were overlaid on 2012 median household income data from US census tracts downloaded from 5-year American Community Survey estimates, as well as the FEMA MOTF flood height layer12.

Table 1:

Distribution of study characteristics according to FEMA and self-reported flood exposure (n= 1,231).

| FEMA Flooding | Self-reported Flooding | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | No | Yes | p value | No | Yes | p value |

| Gender | Female | 289 (60.6) | 188 (39.4) | 0.5837 | 333 (69.8) | 144 (30.2) | 0.2437 |

| Male | 442 (59.0) | 307 (40.1) | 499 (66.6) | 250 (33.4) | |||

| Race | White | 410 (63.7) | 234 (36.3) | 0.0017 | 447 (69.4) | 197 (30.6) | 0.1344 |

| Non-White | 310 (54.8) | 256 (45.2) | 370 (65.4) | 196 (34.6) | |||

| Education | ≤ High school | 231 (49.2) | 239 (50.8) | < 0.0001 | 311 (66.2) | 159 (33.8) | 0.3496 |

| > High school | 474 (66.4) | 240 (33.6) | 491 (68.8) | 223 (31.2) | |||

| Existing mental health condition | No | 496 (63.4) | 287 (36.7) | 0.0004 | 557 (71.1) | 226 (28.9) | 0.0010 |

| Yes | 236 (53.0) | 209 (47.0) | 276 (62.0) | 169 (38.0) | |||

| Apartment Residence | No | 422 (70.9) | 173 (29.1) | < 0.0001 | 411 (69.1) | 184 (30.9) | 0.3871 |

| Yes | 311 (49.0) | 324 (51.0) | 424 (66.8) | 211 (33.2) | |||

| Age (years) | 18 – 27 | 225 (73.8) ** | 80 (26.2) | < 0.0001 | 235 (77.1) ** | 70 (22.9) | < 0.0001 |

| 28 – 45 | 170 (55.9) | 134 (44.1) | 197 (64.8) | 107 (35.2) | |||

| 46 – 58 | 125 (44.2) | 158 (55.8) | 164 (58.0) | 119 (42.0) | |||

| > 58 | 208 (63.2) | 121 (36.8) | 232 (70.5) | 97 (29.5) | |||

| Gender | Female | 289 (60.6) | 188 (39.4) | 0.5837 | 333 (69.8) | 144 (30.2) | 0.2437 |

| Male | 442 (59.0) | 307 (40.1) | 499 (66.6) | 250 (33.4) | |||

| Race | White | 410 (63.7) | 234 (36.3) | 0.0017 | 447 (69.4) | 197 (30.6) | 0.1344 |

| Non-White | 310 (54.8) | 256 (45.2) | 370 (65.4) | 196 (34.6) | |||

| Median Household Income (USD) | < $40,298 | 124 (34.7) | 233 (65.3) | < 0.0001 | 207 (58.0) | 150 (42.0) | < 0.0001 |

| $40,298 - $67,188 | 196 (56.7) | 150 (43.3) | 235 (67.9) | 111 (32.1) | |||

| $67,189 - $89,684 | 201 (70.8) | 83 (29.2) | 195 (68.7) | 89 (31.3) | |||

| > $89,684 | 213 (87.3) | 31 (12.7) | 199 (81.6) | 45 (18.4) | |||

Note: Age was treated as a categorical variable according to quartiles. Participants were assigned a median household income quartile according to 2012 ZCTA data. Comparisons were performed between each variable and each flood measure using Chi-squared tests, not across flood measures.

When data was analyzed according to quartiles of median household income, those with > high school education were equally distributed among income quartiles (< $40,298: 23.5%, $40,298 - $67,188: 36.6%, $67,189 - $89,684: 23.9%, > $89,684: 23.2%), while the lowest two income quartiles contained a disproportionate amount of those with ≤ high school education (< $40,298: 35.5%; $40,298 - $67,188: 33.6%, $67,189 - $89,684: 16.6%, > $89,684: 14.3%; Table 2). These lowest two income quartiles also contained the highest proportions of participants with an existing mental health condition prior to Hurricane Sandy (< $40,298: 34.2%, $40,298 - $67,188: 27.6%). White participants were more represented in higher income quartiles ($67,189 - $89,684: 26.9%, > $89,684: 32.8%) while non-White participants were most present in those lower income quartiles (< $40,298: 39.1%, $40,298 - $67,188: 36.6%; (p < 0.0001). Those aged 28–45 and 46–58 years were most commonly found in the lowest quartiles of income, while those age >58 years were most often in the highest income quartile (35.3%).

Table 2:

Distribution of characteristics of the study sample among quartiles of median household income (n= 1231)

| Quartiles of Median Household Income (USD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | < $40,298 | $40,298 - $67,188 | $67,189 - $89,684 | > $89,684 | p-value |

| Gender | Female | 145 (30.4) | 133 (27.9) | 112 (23.5) | 87 (18.2) | 0.5629 |

| Male | 207 (27.6) | 213 (28.4) | 172 (23.0) | 157 (21.0) | ||

| Race | White | 126 (19.6) | 134 (20.8) | 173 (26.9) | 211 (32.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Non-White | 221 (39.1) | 207 (36.6) | 108 (19.1) | 30 (5.3) | ||

| Education | ≤ High School | 167 (35.5) | 158 (33.6) | 78 (16.6) | 67 (14.3) | < 0.0001 |

| > High School | 168 (23.5) | 181 (25.4) | 199 (23.9) | 166 (23.2) | ||

| Existing mental health condition | No | 202 (25.8) | 223 (28.5) | 195 (24.9) | 163 (20.8) | 0.0169 |

| Yes | 152 (34.2) | 123 (27.6) | 89 (20.0) | 81 (18.2) | ||

| Apartment Residence | No | 104 (17.5) | 105 (17.7) | 200 (33.6) | 83 (13.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Yes | 253 (39.8) | 241 (38.0) | 83 (13.1) | 58 (9.1) | ||

| Age (years) | 18 – 27 | 46 (15.1) | 101 (33.1) | 94 (30.8) | 64 (21.0) | < 0.0001 |

| 28 – 45 | 114 (37.5) | 107 (35.2) | 52 (17.1) | 31 (10.2) | ||

| 46 – 58 | 108 (38.2) | 88 (31.1) | 57 (20.1) | 30 (10.6) | ||

| > 58 | 84 (25.5) | 48 (14.6) | 81 (24.6) | 116 (35.3) | ||

Note: Age was treated as a categorical variable according to quartiles. Participants were assigned a median household income quartile according to 2012 US Census data. Comparisons between median household income quartiles and each variable were performed using Chi-squared tests.

At multivariable analysis, some factors associated with flooding remained consistent across both FEMA and self-report flood measures, as older participants including those > 58 years were more likely to live in a household exposed to flooding (FEMA model ORadj: 1.71, 95% Confidence Interval 1.16–2.53; Self-report model 1.57, 1.07 ‒ 2.32.Those living in higher median household income ZCTAs had a decreased likelihood of experiencing flooding, and this trend was evident in both FEMA (p < 0.001) and self-reported flooding (p < 0.001) as median household income increased (Table 3). Other associated factors differed according to the type of flood measures utilized at multivariate analysis. Models using FEMA data reported that those with ≤ high school education (1.59, 1.21–2.10) and White race (0.74, 0.55–0.98) was associated with an increased likelihood of flooding. This relationship between education (1.02, 0.78–1.34) and race (0.96, 0.73–1.27) were not present when using the self-reported flood measure. Similarly, participants with an existing mental health condition prior to Hurricane Sandy were at increased risk of self-reported flooding (1.36, 1.04–1.77], but not according to FEMA flooding data (1.21, 0.92–1.59), although the two odds ratios and confidence intervals are basically overlapping. Living in an apartment during Hurricane Sandy was inversely associated with self-reported flooding only (0.73, 0.54–0.98). A directed acyclic graph conveying the relationships among predictors and flood measures has been included as Supplementary Figure 1.

Table 3:

Characteristics associated with FEMA flooding (yes/no) and self-reported flooding (yes/no), n= 1,231 participants.

| FEMA Flooding | Self-reported Flooding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Categories | ORadj | 95% Confidence Interval | ORadj | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Gender | Female / male | 1.11 | 0.84 – 1.40 | 1.09 | 0.83 ‒ 1.42 |

| Race | Non-White / White | 0.74 | 0.55 – 0.98* | 0.96 | 0.73 ‒ 1.27 |

| Education | ≤ High school / > High school | 1.59 | 1.21 – 2.10* | 1.02 | 0.78 ‒ 1.34 |

| Existing mental health condition prior to Hurricane Sandy | Yes / no | 1.21 | 0.92 – 1.59 | 1.36 | 1.04 ‒ 1.77* |

| Apartment Residence | Yes / no | 1.28 | 0.95–1.71 | 0.73 | 0.54 ‒ 0.98* |

| Age (years) | 18 – 27 | 1.00 | Ref | 1.00 | Ref |

| 28 – 45 | 1.45 | 0.99 – 2.12 | 1.67 | 1.14 ‒ 2.44 | |

| 46 – 58 | 2.39 | 1.62 – 3.54 | 2.14 | 1.45 ‒ 3.14 | |

| > 58 | 1.71 | 1.16 – 2.53@ | 1.57 | 1.07 ‒ 2.32@ | |

| Median Household Income (USD) | < $40,298 | 1.00 | Ref | 1.00 | Ref |

| $40,298 - $67,188 | 0.42 | 0.30 – 0.58 | 0.67 | 0.49 ‒ 0.93 | |

| $67,189 - $89,684 | 0.27 | 0.18 – 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.43 ‒ 0.90 | |

| > $89,684 | 0.09 | 0.05 – 0.14# | 0.29 | 0.19 ‒ 0.46# | |

Note: Existing mental health status was defined as reporting at least one of the following mental health issues: anxiety disorder, depression, PTSD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, substance/alcohol abuse, substance/prescription abuse, or other mental health problems prior to Hurricane Sandy. Age was treated as a categorical variable according to quartiles. Participants were assigned a median household income quartile according to 2012 US Census data. Logistic regression models were adjusted for gender, race, education status, existing mental health status, residing in an apartment during Hurricane Sandy, quartiles of age and quartiles of median household income.

p < 0.05.

denotes p < 0.05 for trend.

denotes p < 0.001 for trend.

Discussion

Previous research has identified demographic disparities in flood exposure following a hurricane5, and that minority populations are often located in close proximity to sites where environmental exposure is present or highly possible in the case of a natural or human-made disaster3,4,14. This analysis emphasizes disproportionate flood exposure in potentially vulnerable populations such as the aging and less affluent, and the unequal social impacts that natural disasters have. Our analysis shows that higher median household income at the ZCTA level is independently associated with less flooding, when considering both the self-reported and the FEMA flood measures. This suggests that higher income neighborhoods may be located in safer areas than lower income neighborhoods, where flooding from a natural disaster is more likely to occur.

We have previously published that Hurricane Sandy and Hurricane Harvey exposures have long-term mental health consequences, particularly among populations who are most vulnerable such as those with pre-existing mental health conditions15,16. Here, those with existing mental health conditions prior to the hurricane were more frequently living in lower-income areas where the most flooding extent occurred. This integrates with literature reporting an increased vulnerability to natural disasters and their consequences among those who report mental health difficulties prior to the storm17 and among those of lower income18,19. Older adults also face additional challenges during disasters20,21, including difficulty in evacuating their homes, lack of access to medical care and prescriptions, and loss of support networks and services22,23. The present results highlight the heighted vulnerability of older populations during disasters and the need for comprehensive disaster planning to reduce flood exposure. Taken together, the results suggest that lower income neighborhoods are likely to be more exposed to the effects of a natural disaster, and are at the same time home to those who are most vulnerable to the effects of a disaster, such as older adults and those who are less educated or have previous mental health issues.

The current work also highlights the discrepancies in understanding risk factors for flooding based on how flooding is assessed. Our prior research has emphasized that while FEMA measures are more objective in providing flood assessments, self-reported measures of flood exposure can be more valuable for understanding mental health outcomes as they rely on the individual’s perception of his/her exposure to flooding11. The present work underscores this importance, and confirms that having a mental health difficultly prior to Hurricane Sandy was significantly associated with flooding in self-report measures, but not FEMA models, although the two point estimates were very similar. We observed that the more objective FEMA measure of flooding suggest that lower levels of educational attainment were associated with a significant increased likelihood of flooding, but this was not captured by self-reported data on flooding. As educational attainment is one component of socioeconomic status, this finding could complement the association between higher household income and less flood exposure, and warrant further research in understanding disparities in flood exposure.

The study has some limitations: the study utilized convenience sampling, thus it is possible that individuals with lower socioeconomic status, more exposure to the hurricane, and more mental health difficulties will have been more likely to agree to participate, as all participants were receiving a small monetary token for their time. However, as we made an effort to match the demographics of the sample to the general population, the sample closely matched the 2010 United States Census data on race and ethnicity11. Additionally, flood exposure measures must be better refined to capture those residing in apartments units. While FEMA measures can provide a flood height for a specific location that contains an apartment building, it is likely that this flooding value does not apply to all units in the apartment building. Although we have shown that self-reported flood measures can be powerful tools to capture people’s perception of flooding as it relates to their mental health11, it is vital regardless to calculate accurate flood exposure measures for appropriate disaster response and future preparedness.

Socioeconomic and age disparities were present in exposure to flooding during Hurricane Sandy; It is likely that the most vulnerable groups of the population end up living in less favorable areas, more prone to flooding and natural disasters. While prior research has provided quantitative data on the individual experience after hurricane exposure, more research is needed to understand the differential impact of flooding exposure and the unequal vulnerability to adverse outcomes among the exposed population to guide disaster preparedness. As the frequency and intensity of climate change-related disasters will likely increase in the future, disaster preparedness responses must understand flooding from an environmental justice perspective to create appropriate and effective strategies that minimize disproportionate exposure and its subsequent adverse outcomes among socio-economically vulnerable populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under award number U01-TP000573-01 and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response under HITEP150029-01-00, as well as a private donation given to Northwell Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Agyeman J, Schlosberg D, Craven L, & Matthews C. (2016). Trends and directions in environmental justice: from inequity to everyday life, community, and just sustainabilities. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41, 321–340. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holifield R, Chakraborty J, & Walker G. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge handbook of environmental justice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker G. (2009). Beyond distribution and proximity: exploring the multiple spatialities of environmental justice. Antipode, 41(4), 614–636.. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakraborty J, Maantay JA, & Brender JD (2011). Disproportionate proximity to environmental health hazards: methods, models, and measurement. American Journal of Public Health, 101(S1), S27–S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakraborty J, Collins TW, & Grineski SE (2019). Exploring the environmental justice implications of Hurricane Harvey flooding in Greater Houston, Texas. American journal of public health, 109(2), 244–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander AC, Ali J, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Forde DR, Stockton M, Read M, & Ward KD (2017). Racial differences in posttraumatic stress disorder vulnerability following Hurricane Katrina among a sample of adult cigarette smokers from New Orleans. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities, 4(1), 94–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rhodes J, Chan C, Paxson C, Rouse CE, Waters M, & Fussell E. (2010). The impact of Hurricane Katrina on the mental and physical health of low-income parents in New Orleans. American journal of orthopsychiatry, 80(2), 237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowe SR, Willis M, & Rhodes JE (2014). Health problems among low-income parents in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Health Psychology, 33(8), 774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fussell Elizabeth, and Lowe Sarah R.. “The impact of housing displacement on the mental health of low-income parents after Hurricane Katrina.” Social Science & Medicine 113 (2014): 137–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, Jones RT, King DW, King LA, ... & Kessler RC (2007). Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Archives of general psychiatry, 64(12), 1427–1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman-Cribbin W, Liu B, Schneider S, Schwartz R, & Taioli E. (2017). Self-Reported and FEMA flood exposure assessment after hurricane Sandy: association with mental health outcomes. PloS one, 12(1), e0170965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U.S. Census Bureau; American Community Survey, 2012. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19013; http://factfinder2.census.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MOTF F. (2014). FEMA Modeling Task Force (MOTF)-Hurricane Sandy Impact Analysis. FEMA MOTF. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amin R, Nelson A, & McDougall S. (2018). A spatial study of the location of superfund sites and associated cancer risk. Statistics and Public Policy, 5(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz RM, Gillezeau CN, Liu B, Lieberman-Cribbin W, & Taioli E. (2017). Longitudinal impact of Hurricane Sandy exposure on mental health symptoms. International journal of environmental research and public health, 14(9), 957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taioli E, Tuminello S, Lieberman-Cribbin W, Bevilacqua K, Schneider S, Guzman M, ... & Schwartz RM (2018). Mental health challenges and experiences in displaced populations following Hurricane Sandy and Hurricane Harvey: the need for more comprehensive interventions in temporary shelters. JEpidemiol Community Health, 72(10), 867–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sullivan G, Vasterling JJ, Han X, Tharp AT, Davis T, Deitch EA, & Constans JI (2013). Preexisting mental illness and risk for developing a new disorder after Hurricane Katrina. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 201(2), 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petkova EP, Beedasy J, Oh EJ, Sury JJ, Sehnert EM, Tsai WY, & Reilly MJ (2018). Long-term recovery from Hurricane Sandy: evidence from a survey in New York City. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness, 12(2), 172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonanno GA, Galea S, Bucciarelli A, & Vlahov D. (2007). What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 75(5), 671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sirey JA, Berman J, Halkett A, Giunta N, Kerrigan J, Raeifar E, ... & Raue PJ (2017). Storm impact and depression among older adults living in hurricane Sandy-affected areas. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness, 11(1), 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dostal PJ (2015). Vulnerability of urban homebound older adults in disasters: a survey of evacuation preparedness. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness, 9(3), 301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SM, Tremethick MJ, Johnson P, & Gorski J. (2009). Disaster planning and response: considering the needs of the frail elderly. International journal of emergency management, 6(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aldrich N, & Benson WF (2008). Disaster Preparedness and the Chronic Disease Nedds of Vulnerable Older Adults. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(1), 1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.