Highlights

-

•

Bacterial fucose-containing exopolysaccharides (FcEPSs) are reliable source of fucose.

-

•

The bacterial sources, structures, and bioactivities of FcEPSs are reviewed.

-

•

FcEPSs provide promising resources for preparing functional carbohydrates.

Keywords: Fucose, Bacterial exopolysaccharides, Structure, Bioactivity, Food application

Abbreviations: FCPs, fucose-containing polysaccharides; FCOs, fucose-containing oligosaccharides; EPS, exopolysaccharides; FcEPS, fucose-containing EPS; 2′-FL, 2′-fucosyllactose; 3-FL, 3-fucosyllactose; HMOs, human milk oligosaccharides; ROS, reactive oxygen species; DPPH, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; ABTS, 2,2′-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonate; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase

Abstract

Bacterial exopolysaccharides are high molecular weight polysaccharides that are secreted by a wide range of bacteria, with diverse structures and easy preparation. Fucose, fucose-containing oligosaccharides (FCOs), and fucose-containing polysaccharides (FCPs) have important applications in the food and medicine fields, including applications in products for removing Helicobacter pylori and infant formula powder. Fucose-containing bacterial exopolysaccharide (FcEPS) is a prospective source of fucose, FCOs, and FCPs. This review systematically summarizes the common sources and applications of FCPs and FCOs and the bacterial strains capable of producing FcEPS reported in recent years. The repeated-unit structures, synthesis pathways, and factors affecting the production of FcEPS are reviewed, as well as the degradation methods of FcEPS for preparing FCOs. Finally, the bioactivities of FcEPS, including anti-oxidant, prebiotic, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-viral, and anti-microbial activities, are discussed and may serve as a reference strategy for further applications of FcEPS in the functional food and medicine industries.

Introduction

l-fucose (6-deoxy-l-galactose), a rare monosaccharide in nature, is distinct from other d-monosaccharides owing to its unique structure, in which a hydroxyl group is lacking on carbon 6 (Becker & Lowe, 2003). Fucose has attracted increasing attention in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries owing to its important physiological functions, including anti-cancer, anti-allergic, anti-coagulant, and anti-aging activities (Hong, Choi, Chang, & Mun, 2019). However, the complexity and high cost of fucose chemical synthesis make it unable to meet the demands of large-scale industrial production. Recent years, fucose-containing polysaccharides (FCPs) and fucose-containing oligosaccharides (FCOs) have attracted more and more attentions owing to their abundant sources (plants, sea animals, and microorganisms) and functional activities (Freitas et al., 2011, Xiao et al., 2021).

Microbial exopolysaccharides (EPS) are promising sources of fucose, FCOs and FCPs. EPS are high molecular weight carbohydrate polymers produced by many microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and microalgae (Xiao et al., 2021). Bacterial EPS can be secreted extracellularly in two different states: capsular polysaccharides that are closely associated with the cell surface and form a capsule or as slime polysaccharides that are loosely attached or even totally secreted into the cell environment (Barcelos, Vespermann, Pelissari, & Molina, 2019). EPS could be further divided into homopolysaccharides and heteropolysaccharides based on the type of monosaccharides. Homopolysaccharides are usually made up of single monosaccharides, such as glucose and fructose (Oerlemans, Akkerman, Ferrari, Walvoort, & Vos, 2020). Heteropolysaccharides consist of not only glucose, fructose, and galactose, but also some rare monosaccharides, such as mannose, rhamnose, fucose, and occasionally N-acetylglucosamine and uronic acids (Jiang and Yang, 2018, Oerlemans et al., 2020). Common heteropolysaccharides contain xanthan gum produced by Xanthomonas sp., gellan produced by Sphingomonas paucimobilis, alginates produced by Azotobacter sp. and Pseudomonas sp., fucogel produced by Klebsiella pneumoniae, clavan produced by Clavibacter michiganensis, fucoPol produced by Enterobacter sp. A47, or kefiran produced by Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens (Barcelos et al., 2019, Freitas et al., 2011). Accumulating research has shown that bacterial EPS have anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetes, anti-viral, anti-oxidant, cholesterol-lowering, immune regulation, and probiotic activities (Freitas et al., 2011, Oerlemans et al., 2020). Marine microalgae, such as green algae, diatom and red algae, and fungi, such as Auricularia auricula-judae and Ganoderma lucidium, are also considered as abundant sources of EPS containing fucose. And microalgal and fungal EPS have promising applications in food, medicine and cosmetic industries, owing to their important physicochemical and biological properties (Osemwegie et al., 2020, Rui and Yi, 2016). The diversity of monosaccharide compositions, junction positions, branching patterns, and molecular weights resulted in different structures and activities of EPS. EPS have characteristic pseudoplastic rheological, emulsifying, and thickening properties, as well as water binding capacity, which make EPS to be applied as a thickener, emulsifier, and stabilizer to change the appearance, rheological properties, texture, and taste of food products (Li et al., 2017, Rani et al., 2018).

Although FCPs and FCOs are also found in plants, seaweeds, and marine invertebrates, bacterial production of such carbohydrates is demonstrably superior for several factors, namely easily controlled processing procedures and fast and reproducible production (Torres et al., 2012). Fucose-containing bacterial EPS (FcEPS) with high yield and diverse structures can be achieved by liquid fermentation of specific bacterial strains. In this sense, this review aims to summarize the specific FcEPSs, their structures, and 96 kinds of FcEPSs-producing bacteria. Various regulatory health properties of FcEPSs are discussed in depth, covering previous research on this subject. Finally, the applications of FcEPSs in different areas, especially in the food industry, are reviewed.

Research progress on FCPs and FCOs

FCPs and FCOs are considered attractive bioactive compounds owing to their abundant sources and diverse activities and have been applied in the food, medicine, and cosmetic industries. Here, we review the common sources, structural characteristics, activities, and applications of FCPs and FCOs, providing a reference for further efficient acquisition and application of FCPs and FCOs.

Sources and molecular structures of FCPs and FCOs

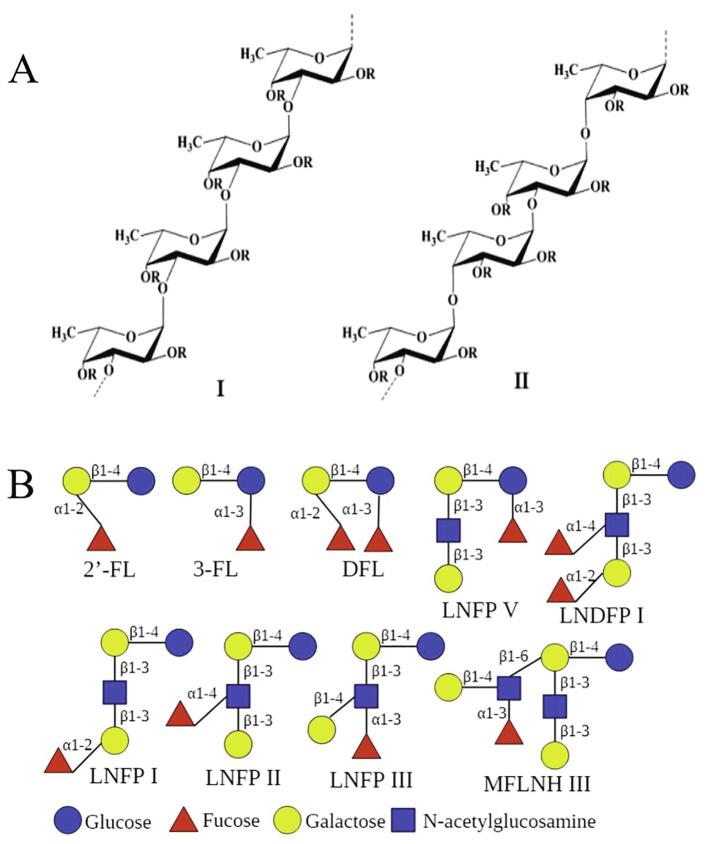

Fucoidan is a type of FCP that is commonly found in the cell wall matrix of brown seaweeds (Fucus distichus, F. evanescens, F. serratus, F. vesiculosus, and Undaria pinnatifida) (Pradhan et al., 2020, Vo and Kim, 2013). Other FCPs, sulfated fucans, and fucosylated chondroitin sulfate are derived from marine invertebrates, including sea cucumbers (Apostichopus japonicus, Pearsonothuria graeffei, Stichopus tremulus, and Holothuria vagabunda) and sea urchins (Lytechinus variegatus, Ly. grisea, Arbacia lixula, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, and S. franciscanus) (Shida, Mikami, Tamura, & Kitagawa, 2017). Fucoidan mostly consists of fucose and sulfate ester groups, with a small amount of other monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, mannose, rhamnose, and xylose) and uronic acids. The backbone of fucoidans are known as two types: one consisting of repeating (1 → 3)-linked α-fucosyl residues and another consisting of alternated (1 → 3)- and (1 → 4)-linked α-fucosyl residues (Fig. 1A) (Vo & Kim, 2013). The fucoidans extracted from sea cucumbers are composed of (1 → 3)-linked tetrafucose repeated units, each with one or two HSO4 substitutions (Chang, Hu, Long, Mcclements, & Xue, 2016). The structure of fucan is characterized as (1 → 3)- and/or (1 → 2)-linked fucosyl residues and sulfated or non-sulfated fucose residues on the side chains, similar to fucosylated chondroitin sulfate (Cao, Surayot, & You, 2017).

Fig. 1.

Structures of fucose-containing polysaccharides and fucose-containing oligosaccharides (FCOs). (A) Two types of backbones in fucoidans extracted from brown seaweeds. (B) Structures of the main FCOs in human milk. 2′-FL: 2′-fucosyllactose; 3-FL: 3-fucosyllactose, DFL: difucosyllactose, LNFP: lacto-N-fucopentaose, LNDFH: lacto-N-difucohexaose; MFLNH: monofucosyllacto-N-hexaose.

Human milk is an important source of natural FCOs. Human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are the third most abundant solid component in human milk and have a significant influence on infant health (Bode, 2015, Bych et al., 2019). There are >200 kinds of oligosaccharides in HMOs, which are roughly divided into acidic sialylated HMOs and neutral HMOs. Most of the neutral HMOs are fucosylated HMOs, accounting for 60% of the total HMOs, including 2′-fucosyllactose (2′-FL, 31%), 3-fucosyllactose (3-FL, 5%), difucosyllactose (4%), lacto-N-fucopentaose I/II/III (8/2/2%), lacto-N-fucopentaose V, lacto-N-difucohexaose I (4%), and monofucosyllacto-N-hexaose III (Bych et al., 2019, Pérez-Escalante et al., 2020). All nine FCOs are formed by the connection of three or four monosaccharides (glucose, galactose, fucose, and/or N-acetylglucosamine), with fucose as the non-reducing end and lactose as the reducing end (Fig. 1B).

Biological properties and applications of FCPs and FCOs

During the last decades, many studies have demonstrated that fucoidans extracted from brown seaweeds or marine invertebrates possess promising application prospect in marine functional foods owing to their various biological functions, including anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, anti-tumor, anti-obesity, anti-coagulant, anti-viral, anti-hepatopathy, anti-uropathy, and anti-renalpathy activities (Pradhan et al., 2020). In addition, fucoidans are considered as superior dietary fiber, which may be attributed to their functions of promoting gastrointestinal peristalsis and increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria in the intestine (Li, Xue, Zhang, & Wang, 2020). Fucoidans also play a positive part in adsorbing toxic substances (especially toxic heavy metals) in intestine, thereby reducing the harm of toxic substances accumulation (Gao et al., 2020). Nowadays, fucoidan has been applied in the preparation of functional foods and beverages, including tablets, capsules, and granules, with the functions of enhancing immune, relieving constipation, reducing allergy, clearing Helicobacter pylori, etc. Although there are various extraction methods to prepare FCPs from brown algae and marine invertebrates, the exploration of optimal reaction conditions and new purification methods should be taken into consideration to simplify the extracted process and improve the yield of FCPs (Vo & Kim, 2013). In addition, FCPs extracted from different species, and even from the same species, have various structures that depend on the harvesting season and location. Special attention should be paid to the precise structural characterization of FCPs, and extensive in vivo studies is necessary to accurately assess their potential therapeutic applications.

Accumulating research has shown that fucosylated HMOs play a vital role in regulating intestinal health in early life by promoting the growth of dominant bacterial strains (bifidobacteria strains) in the gut (Pérez-Escalante et al., 2020). Fucosylated HMOs exert anti-microbial activity by modifying the host’s epithelial cell-surface glycome (Zhu et al., 2020). In addition, fucosylated HMOs are beneficial for promoting the maturation of the infant immune system and improving the cognitive ability of the baby brain, especially in the first months of life (Bode, 2015). 2′-FL is the most abundant oligosaccharide in human milk, and it has unique biological effects. Many clinical studies have shown that milk powder supplemented with 2′-FL is safe and well tolerated in infants, and the immune development of infants receiving 2′-FL supplemented milk powder is similar to that of breastfed infants (Zhu et al., 2020). To date, 2′-FL has attracted great attention in large-scale production and commercial applications, and infant formula supplemented with 2′-FL is available in some countries. Moreover, 2′-FL prepared by the fermentation of Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) #1540 has passed the safety certification of the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) (EU, 2017/2470) and the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA, GRN 650). In addition, 3-FL is also one of the abundant HMOs in human milk, and the concentration of 3-FL will increase with the extension of lactation. At present, 3-FL is considered to reduce the risk of intestinal microbiota imbalance caused by harmful bacteria and selectively stimulate the growth of beneficial bifidobacteria (Bych et al., 2019). And 3-FL prepared by the fermentation of E. coli K12MG1655 has been authorized to apply in food field as a new resource food. However, the availability of 2′-FL and 3-FL is limited by the high cost associated with its relatively complex synthesis process (Bych et al., 2019, Zhu et al., 2020). Therefore, new sources or preparation processes for FCPs and FCOs require further investigation.

Physiochemical and structural features of FcEPSs

FcEPSs produced by microorganisms have greater development potential for applications in the food, cosmetic, and medical industries than other natural materials. The preparation of fucose, FCOs, and FCPs via chemical synthesis or traditional extraction from natural sources (plants, algae, and animals) is not an easy task to meet the demands of large-scale industrial production. Production via microorganisms is a new strategy for the efficient preparation of fucose FCOs, and FCPs. Microorganisms capable of producing FcEPSs include a broad range of bacteria, as reviewed in Table 1, and the repeated-units structures of FcEPSs produced by several bacteria are displayed in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

The culture conditions of fucose-containing exopolysaccharides (FcEPS) producing bacteria, and monosaccharide compositions and molecular weights of these FcEPSs.

| No. | Bacteria | Source | Main carbon source | Temperature/time | Maximum yield | Monosaccharide composition | Molecular weight | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acidianus sp. | DSM 29099 | Yeast extract | 65 °C/7 d | – | Glucose/mannose/fucose | – | Zhang et al., 2019 |

| 2 | Acidithibacillus ferrooxidans R1 | – | – | 28 °C | – | Rhamnose/fucose/xylose/mannose/glucose/glucuronic acid = 10.8/17.1/0.8/0.7/15.2 /3.9/0.6 (by molar ratio) | – | (Kinzler, Gehrke, Telegdi, & Sand, 2003) |

| 3 | Aerobacter aerogenes | ATCC 12657 | – | 37 °C/16 h | – | aFucose/mannose | – | (Kornfeld, 1966) |

| 4 | Aerobacter cloaca | – | – | – | – | Galactose/glucose/fucose/uronic acid | – | (Salton, 1960) |

| 5 | Aeromonas hydrophila | – | Yeast extract | 30 °C | – | Fucose/mannosyl/glucose/N-acetylgalactosamine | – | (Castro et al., 2014) |

| 6 | Alcaligenes faecalis | NCTC 8764 | – | – | – | Glucose/arabinose/fucose/rhamnose | – | (Salton, 1960) |

| 7 | Alcaligenes latus B-16 | – | – | – | 25 g/L | Fucose/glucose/rhamnose/glucuronic acid = 1/1.8/1.1/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Nagayama, Karaiwa, Ueta, & Imai, 2002) |

| 8 | Alteromonas macleodii subsp. fijiensis HYD657 | Hydrothermal vent | Glucose | 28 °C/50 h | – | Galactose/glucose/rhamnose/glucuronic acid/galacturonic acid/mannose/fucose = 5.9/2.6/2.5/2.0/1.9/1.4/1.0 (by molar ratio) | 1.1 × 106 Da | (Costaouëc et al., 2012) |

| 9 | Azotobacter vinelandi | MTCC 2460 | Sucrose | 30 °C/2 d | – | Glucose/galactose/fucose/glucoronic acid = 2.2/2.7/5.6 /1.6 (by molar ratio) | – | (Vermani, Kelkar, & Kamat, 1995) |

| 10 | Bacillus atrophaeus WYZ | Mangrove system | Peptone, yeast extract, glucose | 37 °C/40 h | 0.58 g/L | Glucose/rhamnose/fucose/glucuronic acid = 84.4/7.2/6.7/1.7 (by mass percentage) | 3.19 × 105 Da | (Zhu et al., 2018) |

| 11 | Bacillus coagulans RK-02 | Soil sample | Yeast extract, glucose | 37 °C/36 h | 0.33 ± 0.005 g/L | Galactose/mannose/fucose/glucosamine/glucose = 55 ± 2.7/18 ± 2/12 ± 1.5/9 ± 2.8/7 ± 1.3 (by mass percentage) | – | (Kodali et al., 2009) |

| 12 |

Bacillus licheniformis BioE-BL11 |

Korean kimchi | Tryptone, sucrose | 37 °C/3 d | 9.18 g/L | Mannose/galactose/glucose/fucose/arabinose = 12.4/1.82/48.5/37.1/0.17 (by mass percentage) | 6.69 × 104 Da | (Kook et al., 2019) |

| 13 | Bacillus licheniformis T8 | Chinese Academy of Sciences | Yeast extract and peptone | 37 °C/3 d | 3.07 g/mL | BL-P1: mannose/ribose/rhamnose/galacturonic acid/glucose/galactose/xylose/arabinose/fucose=4.07/0.34/0.05/0.04/4.27/0.47/0.04/0.04/0.05; BL-P2: mannose/ribose/rhamnose/glucuronic acid/galacturonic acid/glucose/galactose/xylose/arabinose/fucose = 11.95/0.53/0.07/0.23/0.01/0.89/3.97/0.04/0.07/0.2 (by molar ratio) |

BL-P1: 3.96 × 106 Da; BL-P2: 1.23 × 105 Da |

(Xu et al., 2019) |

| 14 | Bacillus licheniformis T14 | Hydrothermal vent | Sucrose and yeast extract | 50 °C/2 d | 366 mg/L | Fructose/fucose/glucose/galactosamine/mannose = 1.0/0.75/0.28/tr/tr (by molar ratio) | 1 × 106 Da | (Gugliandolo et al., 2014, Spanò et al., 2013, Spanò et al., 2016) |

| 15 | Bacillus megaterium RB-05 | – | Glucose | 33 °C/90 h | 0.065 ± 0.013 g/L | N-acetyl glucosamine/glucose/galactose/mannose/arabinose/fucose = 4/14.03/37.58/19.33/20.16/4.9 (by mass percentage) | 1.7 × 105 Da | (Chowdhury, Basak, Sen, & Adhikari, 2011) |

| Jute fiber | 0.297 g ± 0.054 g/L | N-acetyl glucosamine/glucose/galactose/mannose /fucose = 3.55/26.56/12.19/15.81/41.89 (by mass percentage) | 1.28 × 105 Da | (Chowdhury et al., 2014) | ||||

| 16 | Beijerinckia indica TX-1 | Soil | Glucose and peptone | 30 °C/4 d | – | Glucose/fucose/glycero-manno-heptose/glucuronic acid = 5/1/2/0.9 (by molar ratio) | 6.5 × 105 Da | (Ohtani et al., 1995) |

| 17 | Bifidobacterium longum H73 | Human intestinal microbiota | MRSC broth | 37 °C/5 d | – | Rhamnose/galactose/glucose/fucose | 105–106 Da (70.7%), < 104 Da (29.3%) | (Salazar et al., 2009) |

| 18 | Bifidobacterium longum H63 | Human intestinal microbiota | – | – | – | Rhamnose/galactose/glucose/fucose | 105 ∼ 106 Da (52.6%), < 104 Da (47.4%) | (Salazar et al., 2009) |

| 19 | Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum H34 | Human intestinal microbiota | – | – | – | Galactose/glucose/fucose/N-acetyl-glucosamine | 105 ∼ 106 Da (56.5%), < 104 Da (43.5%) | (Salazar et al., 2009) |

| 20 | Burkholderia vietnamiensis LMG 10929 | BCCMTM bacteria collection | Mannitol and yeast extract | 30 °C/4 d | 35 mg/Petri dish | Rhamnose/fucose/mannose/galactose/glucose=0.31/0.23/0.08/1/1 (by molar ratio) | >1 × 106 Da | (Cescutti, Cuzzi, Herasimenka, & Rizzo, 2013) |

| 21 | Chromobacterium violoaceum | NCTC 7917 | CCY broth | 37 °C/22 h | – | Galactose/glucose/xylose/arabinose/fucose/galacturonic acid | – | (Davies, 1955) |

| 22 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis | NCPPB 382 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 43.5/25.9/30.6/<1 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 23 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis | CMM 100 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 48.8/24.7/24.7/1.8 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 24 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis | NCPPB 1574 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 46.6/25.9/27.3/<1 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 25 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis | NCPPB 1496 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 44.5/33.2/22.3/<1 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 26 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis | NCPPB 515 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 9.6/31.2/6.4/52.8 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 27 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis | NCPPB 254 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 11.1/27.9/24.4/36.6 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 28 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis | NCPPB 399 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 26.4/20.6/32.2/20.8 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 29 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis | NCPPB 1064 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Glucose/galactose/fucose/pyruvate/succinate/acetate = 0.97/1/2.02/1.01/0.52/1.55 (by molar ratio) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bulk et al., 1991) |

| 30 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. insidiosus | NCPPB 2581 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 22.85/23.7/41.7/6.1 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 31 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus | NCPPB 1686 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 43.7/25.7/30.6/<1 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 32 | Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. nehraskensis | NCPPB 2140 | Yeast extract and glucose | 25 °C/12 d | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose = 20.9/24.4/22.9/29.8 (by molar percentage) | >1 × 105 Da | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 33 | Corynebacterium insidiosum | – | – | – | – | Glucose/galactose/fucose/pyruvic acid = 1/1/2/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Gorin, Spencer, Lindberg, & Lindh, 1980) |

| 34 | Enterobacter sp. A47 | DSM 23139 | Lactose | 30 ± 0.2 °C/4 d | 5.22 g/L | Fucose/galactose/glucose/glucuronic acid = 25/22/24/29 (by molar percentage) | 4.7 × 106 Da | (Antunes et al., 2015) |

| Cheese whey | 30 ± 0.2 °C/4 d | 6.40 g/L | Fucose/galactose/glucose/glucuronic acid = 29/21/21/29 (by molar percentage) | 1.8 × 106 Da | (Antunes et al., 2015) | |||

| Glycerol | 30 ± 0.1 °C/7 d | 13.28 ± 0.74 g/L | Fucose/galactose/glucose = 36 ∼ 48/21 ∼ 25/27 ∼ 32 (by molar percentage) | 0.9 ∼ 1.3 × 107 Da | (Alves et al., 2010) | |||

| 13.3 g/L | Fucose/galactose/glucose/mannose/rhamnose = 25/32/38/<1/<1 (by molar percentage) | 5.8 × 106 Da | (Cruz et al., 2011) | |||||

| Glycerol byproduct | 15.9 ∼ 14.1 °C/4 d | 7.79 g/L | Fucose/galactose/glucose/glucuronic acid/rhamnose /glucosamine/=0 ∼ 36/12 ∼ 26/27 ∼ 61/6 ∼ 12/0 ∼ 29/0 ∼ 11 (by molar percentage) | 0.26 ∼ 1.46 × 107 Da | (Torres et al., 2012) | |||

| Glucose | 30 ± 0.1 °C/4 d | 13.4 g/L | Fucose/galactose/glucose/glucuronic acid = 29/29/26/16 (by molar percentage) | 4.2 × 106 Da | (Freitas et al., 2014) | |||

| Xylose | 30 ± 0.1 °C/4 d | 5.39 g/L | Fucose/galactose/glucose/glucuronic acid = 38/18/27/17 (by molar percentage) | 1.7 × 106 Da | ||||

| 35 | Enterobacter amnigenus BPT 165 | Helsinki University of Technology | Yeast extract, bactopeptone and sucrose | 32 °C/6 h | – | Fucose/mannose/galactose/glucose = 1.5/0.2/1.1/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Cescutti et al., 2005) |

| 36 | Enterobacter cloacae | Marine sediment | Sucrose, peptone and yeast extract | 27 ∼ 30 °C/76 h | – | Fucose/galactose/glucose/glucuronic acid = 2/1/1/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Iyer et al., 2005) |

| 37 | Enterobacter cloacae Z0206 | Zhejiang University | Potato, bacto-peptone yeast extract and sucrose | 30 °C/2 d | – | Fucose/glucose/galactose/glucuronic acid/pyruvic acid = 2/1/3/1/1 (by molar ratio) | 1.1 × 106 Da | (Wang, Yang, & Wang, 2013) |

| Potato, bacto-pepton, yeast extract and sucrose | – | Se-ECZ-EPS-1: glucose/galactose/mannose = 91.75/0.66/7.59 (by molar percentage) | Se-ECZ-EPS-1: 2.93 × 104 Da | (Xu, Wang, Jin, & Yang, 2009) | ||||

| 38 | Enterobacter ludwigii Ez-185–17 | Root nodules | Glutamate and mannitol | 30 °C/3 d | 0.7 g/L | Galactose/glucose/fucose/glucuronic acid = 2/1/2/1 (by molar ratio) | 2.9 × 106 Da | (Pau-Roblot et al., 2013) |

| 39 | Enterobacter sakazakii M1 | Ocean University of China | Glucose | 36 ℃/2 d | 1.5 g/L | Fucose/glucose/galactose/galacturonic acid/glucuronic acid/mannose/rhamnose = 42.72/21.81/20.59/6.19/5.81/1.76/1.12 (by molar percentage) | 1.77 × 107 Da | (Xiao et al., 2021) |

| 40 | Escherichia coli EC100. Loci | – | 37 °C/1 d | – | Fucose/arabinose/galactose(N-acetyl glucosamine)/glucose/xylose/ribose/glucuronic acid = 80/3/53/69/1/2/64 (by molar percentage) | – | (Li et al., 2019) | |

| 41 | Flavobacterium uliginosum | Sea water | Glucose, polypeptone and yeast extract | 28 °C/2 ∼ 3 d | – | Glucose/mannose/fucose = 7/2/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Umezawa et al., 1983) |

| 42 | Geobacillus sp. 1A60 | Hydrothermal vents | Sucrose and yeast extract | 50 °C/3 d | 185 mg/L | Mannose/galactose/galactosamine/fucose/glucose=1/0.69/0.65/0.59/0.35 (by molar ratio) | – | (Gugliandolo, Lentini, Spanò, & Maugeri, 2012) |

| 43 | Geobacillus tepidamans V264 | Hot spring | Maltose and yeast extract | 60 °C | 111.4 mg/L | Glucose/galactose/fucose/fructose = 1/0.07/0.04/0.02 (by molar ratio) | > 1 × 106 Da | (Kambourova et al., 2009) |

| 44 | Gracilibacillus sp. SCU50 | Saline soil | Sucrose, tryptone and yeast extract | 30 °C/3 d | – | Mannose/galactose/glucose/fucose = 90.81/5.76/2.22 /1.21 (by molar percentage) | 5.881 × 104 Da | (Gan et al., 2020) |

| 45 | Halomonas stenophila HK30 | Soil | Dextrose, peptone, yeast extract and malt extract | 32 °C/5 d | 3.89 ± 0.1 g/L | Glucose/glucuronic acid/mannose/fucose/galactose/rhamnose = 24 ± 1.73/7.5 ± 0.37/5.5 ± 0.17/4.5 ± 0.36/1.2 ± 0.17/1 ± 0.05 (by molar percentage) | 1.4 × 106 Da/8.2 × 104 Da | (Amjres et al., 2015) |

| 46 | Halomonas stenophila B100 | Hypersaline soils | Dextrose, peptone, yeast extract and malt extract | 32 °C/5 d | – | Glucose/mannose/galactose = 44.5/15/40.5 (by molar percentage) | 3.75 × 105 Da | (Ruiz-Ruiz et al., 2011) |

| 47 | Halomonas stenophila N12T | Hypersaline soils | Dextrose, peptone, yeast extract and malt extract | 32 °C/5 d | – | Glucose/mannose/fucose = 48.82/25.47/25.69 (by molar percentage) | 2.5 × 105 Da | (Ruiz-Ruiz et al., 2011) |

| 48 | Klebsiella type 1 | – | – | – | – | Glucose/glucuronic acid/fucose/pyruvic acid = 1/1/1/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Rieger-Hug & Stirm, 1981) |

| 49 | Klebsiella type 6 | – | – | – | – | Glucose/glucuronic acid/fucose/pyruvic acid = 1/1/1/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Rieger-Hug & Stirm, 1981) |

| 50 | Klebsiella type 16 | – | – | – | – | Glucose/galactose/fucose | – | (Rieger-Hug & Stirm, 1981) |

| 51 | Klebsiella type 54 | – | – | – | – | Glucose/glucuronic acid/fucose = 2/1/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Rieger-Hug & Stirm, 1981) |

| 52 | Klebsiella type 60 | – | – | – | – | Glucose/mannose/fucose | – | (Rieger-Hug & Stirm, 1981) |

| 53 | Klebsiella type 63 | – | – | 30 °C/4 d | – | Fucose/galactose/galacturonic acid = 1/1/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Joseleau & Marais, 1979) |

| 54 | Klebsiella oxytoca | – | Glucose, yeast extract and peptone | 30 °C/7 d | – | Rhamnose/fucose/arabinose/xylose/mannose/galactose/glucose = 3.2968/4.1085/1.4653/0.5126/23.9307/9.8622/13.0377 (by molar ratio) | 116018 Da | (Feng, Li, Du, & Chen, 2009) |

| 55 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | ATCC 31646 | – | 30 °C/4 d | – | Fucose/galactose/galacturonic acid = 1/1/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Johansson, Jansson, & Widmalm, 1994) |

| 56 | Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae BEC1000 CNCMI-1507 | Sludge | Sorbitol, peptone and yeast extract | 30 °C/2 ∼ 4 d | 12 g/L | Fucose/galactose/galacturonic acid = 1/1/1 (by molar ratio) | 1 × 106 Da | (Paul, Perry, & Monsan, 1999) |

| 57 | Kosakonia sp. | CCTCC M2018092 | Glucose and yeast extract | 30 °C/20 h | – | Fucose/glucose/galactose/glucuronic acid /pyruvic acid = 2.03/1.00/1.18/0.64/0.67 (by molar ratio) | 3.65 × 105 Da | (Li et al., 2020) |

| 58 | Lactobacillus casei SB27 | Yak milk | Skim milk containing glycerol | 37 °C/36 h | – | LW1: rhamnose/fucose/arabinose/xylose/mannose /glucose/galactose = 3.1/1.9/7.2/1.4/4.9/29.1/52.4; LW2: rhamnose/fucose/arabinose/xylose/mannose/glucose/galactose = 2.0/2.6/5.6/1.6/8.5/22.2/57.4 (by molar percentage) | LW1: 2.51 × 104 Da; LW2: 1.234 × 104 Da | (Di et al., 2017) |

| 59 | Lactobacillus gasseri FR4 | Gastro intestinal tract of free range chicken | Sucrose | – | 7.5 g/L | Glucose/mannose/galactose/rhamnose/fucose = 65.31/16.51/8.45/6.55/3.18 (by molar percentage) | 1.86 × 105 Da | (Rani et al., 2018) |

| 60 | Lactobacillus plantarum JLAU103 | Hurood in Inner Mongolia of China | Bacto proteose peptone, bacto beef extract, bacto yeast extract and d-sorbitol | 37 °C/1 d | 75 mg/L | Arabinose/rhamnose/fucose/xylose/mannose/fructose/galactose/glucose = 4.05/6.04/6.29/5.22/1.47/5.21/2.24/1.83 (by molar ratio) | 1.24 × 104 Da | (Min et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2020) |

| 61 | Lactobacillus plantarum KX041 | Chinese Paocai | Lactose, soy peptone, beef extracts and yeast extract | 35 °C/25 h | 0.6 g/L | EPS-1: arabinose/mannose/glucose/galactose = 1.09/88.53/3.99/6.39 (by molar percentage) | 57201 Da | (Xu et al., 2019) |

| EPS-2: arabinose/mannose/glucose/galactose = 0.58/94.11/3.55/1.76 (by molar percentage) | 70734 Da | |||||||

| EPS-3: rhamnose/fucose/arabinose/xylose/mannose /glucose/galactose/galacturonic acid = 2.01/2.65/10.95/4.62/4.07/27.81/44.16/3.73 (by molar percentage) | 26387 Da | |||||||

| 62 | Leuconostoc mesenteroides BioE-LMD18 | – | – | – | 5.03 g/L | Mannose/arabinose/galactose/glucose/fucose = 8.71/0.07/1.22/79.8/10.21 (by molar percentage) | 1.24 × 105 Da | (Kook et al., 2019) |

| 63 | Microbacterium aurantiacum FSW-25 | Rasthakaadu beach | Glucose | 28 °C/3 d | 7.81 g/L | Glucuronic acid/glucose/mannose/fucose | 7.0 × 106 Da | (Sran et al., 2019) |

| 64 | Paenibacillus edaphicus NUST16 | Coastal soil | Sucrose | 30 °C/108 h | 12.5 ± 0.5 g/L | Mannose/glucuronic acid/glucose/galactose/fucose = 3.11/0.85/3/0.9/1.89 (by molar ratio) | 1.2 × 107 Da | (Li et al., 2017) |

| 65 | Pediococcus pentosaceus KFT18 | KCCM11309P | Sucrose | –/2 d | 3.94 g/L | Glucose/mannose/galactose/2-methyl xylose/fucose /rhamnose/2-methyl fucose/xylose/arabinose/aceric acid = 67.7/13.4/8.85/7.55/1.5/0.4/0.15/0.05/0.05/0.25 (by molar percentage) | ≥ 2.56 × 106 Da | (Shin et al., 2016) |

| 66 | Polaribacter irgensii CAM006 | Sea ice and seawater | Glucose | 20 °C/7 d | – | Arabinose/fucose/mannose/galactose/glucose/glucuronic acid/N-acetylgalactosamine/N-acetyl- glucosamine = 2/11/33/38/4/6/1/4 (by mass percentage) | 2.1 × 106 Da | (Nichols et al., 2005) |

| 67 | Polaribacter sp. SM1127 | Brown algae | Glucose, peptone and yeast extract | 15 °C/5 d | 2.11 g/L | Rhamnose/fucose/glucuronic acid/mannose/galactose/glucose/N-acetylglucosamine = 0.8/7.4/21.4/23.4/17.3/1.6/28.0 (by molar percentage) | 2.2 × 105 Da | (Sun et al., 2015) |

| 68 | Propionibacterium acidi-propionici VM-25 | ATCC 25562 | Partially deproteinated whey and lactose | 25 °C/3 d | 10 ∼ 15 g/L | Water-insoluble fraction: fucose/mannose/glucose/galactose = 7/22/40/31 (by mass percentage) | – | (Racine, Dumont, Champagne, & Morin, 1991) |

| 69 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. CAM003 | – | – | – | – | Arabinose/ribose/rhamnose/fucose/mannose/glucose/glucuronic acid/N-acetyl galactosamine /N-acetylglucosamine = 4/2/6/29/40/16/1/1/1 (by mass percentage) | 1.8 × 106 Da | (Nichols et al., 2005) |

| 70 | Pseudoalteromonas sp. CAM025 | Sea ice | Yeast extract and bacteriolo- gical peptone | −2 °C/14 d; 10 °C/14 d; 20 °C/7 d | 97.2 ± 9.3/99.9 ± 8/3.6 ± 0.2 mg/g (dry weight) | −2 °C: arabinose/ribose/rhamnose/fucose /galacturonic acid/mannose/galactose/glucose = 3.1 ± 1.0/1.2 ± 0.9/4.8 ± 0.5/1.6 ± 0.4/15.8 ± 0.4/16.5 ± 0.7/5.7 ± 0.3/51.3 ± 1.8 (by mass percentage); 10 °C: arabinose/ribose/rhamnose/fucose/galacturonic acid/mannose/galactose /glucose = 3.7 ± 1.9/1.6 ± 0.2/18.8 ± 3.1/7.7 ± 0.4/8.1 ± 1.0/9.6 ± 1.5/19.7 ± 3.2/30.9 ± 5.4 (by mass percentage); 20 °C: arabinose/rhamnose/fucose /galacturonic acid/mannose /galactose /glucose = 11.3 ± 2.5/25.9 ± 5.8/6.9 ± 2.9/0.2 ± 0.2/8.9 ± 0.8/23.6 ± 2.0/23.3 ± 9.2 (by mass percentage) | 5.7 × 106 Da | (Nichols et al., 2005) |

| 71 | Pseudomonas sp. | – | – | – | – | Glucose/fucose/rhamnose | – | (Salton, 1960) |

| 72 | Pseudomonas fluorescens Biovar II | ATCC 55421 | Soy broth | 37 °C/12 h | Rhamnose/fucose/arabinose/ribose/xylose/mannose/galactose/glucose | – | (Hung et al., 2005) | |

| 73 | Pseudomonas fluorescens H13 | Discolored lesions on mushroom caps | – | 20 ∼ 28 °C/2 ∼ 3 d | 7 ∼ 30 mg/five culture dishes | Glucose/glucosamine/rhamnose/fucose/arabinose/acetate | – | (Fett, Wells, Cescutti, & Wijey, 1995) |

| 74 | Pseudomonas marginalis type C | ATCC 10844 | – | 20 °C/7 d | – | Glucose/fucose/propionic acid = 2/1/1 (by molar ratio) | 1.49 × 106 Da | (Fishman et al., 1997) |

| 75 | Pseudomonas mendocina P2d | An industrial effluent | – | 28 °C/1 d | – | Rhamnose/fucose/glucose/ribose/arabinose/mannose = 50.79/3.33/7.23/6.53/0.76/19.21 (by mass percentage) | – | (Royan et al., 1999) |

| 76 | Pseudomonas oleovorans NRRL B-14682 | – | Glycerol byproduct | 30 ± 0.2 °C/5 d | 15 g/L | Galactose/mannose/glucose/fucose/rhamnose = 68/17/13/4/2 (by molar percentage) | 4.6 × 106 Da | (Alves et al., 2010) |

| 77 | Pseudomonas sp. ID1 | Marine sediment | Glucose, bacto-peptone and yeast extract | 11 °C/5 d | – | Glucose/galactose/fucose = 17.04% ± 0.32/8.57% ± 1.15/8.21% ± 1.12 (by molar percentage) | > 2 × 106 Da | (Carrión, Delgado, & Mercade, 2015) |

| 78 | Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola Ex-4 | Institute collection no. 655, IPO 38-2R7 | – | 25 °C/2 d | 761 mg/L | Rhamnose/fucose/glucose/amino sugars | – | (Gross & Rudolph, 1987) |

| 79 | Rhizobium sullae A6 | – | Mannitol and yeast extract | 28 °C/1 d | 7.5 ± 2.0 mg/g | Glucose/galactose/fucose/mannose/galacturonic acid/rhamnose = 42.7 ± 6.5/33.4 ± 1.0/19.9 ± 13.5/<1/<10/<1 (by molar percentage) | < 1.5 × 105 Da, 0.1 ∼ 6 × 104 Da | (Gharzouli, Carpéné, Couderc, Benguedouar, & Poinsot, 2013) |

| Sucrose and yeast extract | 10.6 ± 0.6 mg/g | Glucose/galactose/fucose/mannose/galacturonic acid/rhamnose = 24.7 ± 6.7/34.9 ± 2.0/30.4 ± 17.0/2.3 ± 1.5/<10/<1 (by molar percentage) | ||||||

| Glucose and yeast extract | 10.7 ± 1.1 mg/g | – | ||||||

| Sorbitol and yeast extract | 11.0 mg/g | Glucose/galactose/fucose/mannose/galacturonic acid/rhamnose = 54.4 ± 9.5/23.3 ± 1.2/<1/8.5/<10/11.2 ± 4.2 (by molar percentage) | ||||||

| 80 | Rhizobium sullae RHF | – | Mannitol and yeast extract | 28 °C/1 d | 11.6 ± 1.3 mg/g | Glucose/galactose/fucose/mannose/galacturonic acid/rhamnose = 34.1 ± 4.7/29.5 ± 2.0/23.6 ± 8.2/12.3 ± 12.3/<1/<1 (by molar percentage) | < 1.5 × 105 Da, 0.1 ∼ 6 × 104 Da | (Gharzouli et al., 2013) |

| Sucrose and yeast extract | 13.7 ± 1.0 mg/g | Glucose/galactose/fucose/mannose/galacturonic acid/rhamnose = 39.5 ± 6.3/28.8 ± 0.3/25.5 ± 12.5/<1/<10/<1 (by molar percentage) | ||||||

| Glucose and yeast extract | 20.6 ± 2.6 mg/g | – | ||||||

| Sorbitol and yeast extract | 3.4 ± 1.0 mg/g | Glucose/galactose/fucose/mannose/galacturonic acid = 35.5 ± 2.0/33.6 ± 0.5/29.5 ± 2.7/<1/<1 (by molar percentage) | ||||||

| 81 | Rhodospirillum rubrum | – | – | – | – | Glucose/fucose/rhamnose | – | (Salton, 1960) |

| 82 | Rhodococcus erythropolis HX-2 | Xinjiang oil field | Yeast powder | 25 °C/3 d | 8.957 g/L | Glucose/galactose/fucose/mannose/glucuronic acid = 27.29/24.83/4.79/26.66/15.84 (by molar percentage) | 1.04 × 106 Da | (Hu et al., 2019) |

| 83 | Salmonella enteritidis | – | – | – | – | aFucose/rhamnose | – | (Graber, Morin, Duchiron, & Monsan, 1988) |

| 84 | Salmonella grumpensis | NCTC 6533 | – | 37 °C/22 h | – | Glucosamine/chondrosamine/galactose/glucose/fucose | – | (Davies, 1955) |

| 85 | Salmonella paratyphi B | – | – | – | – | aFucose | – | (Graber et al., 1988) |

| 86 | Salmonella poona | NCPPB 254 | Yeast extract and glucose | 37 °C/22 h | – | Glucosamine/chondrosamine/galactose/glucose/fucose | – | (Bermpohl et al., 1996) |

| 87 | Salmonella typhimurium | – | – | – | – | aFucose | – | (Graber et al., 1988) |

| 88 | Salmonella wandsworth | – | – | – | – | aFucose | – | (Graber et al., 1988) |

| 89 | Salipiger mucosus A3T | Hypersaline soil (CECT 5855 T) | Dextrose, peptone, yeast extract and malt extract | 32 °C/5 d | 1.35 g/L | Glucose/mannose/galactose/fucose = 19.7/34/32.9/13.4 (by molar percentage) | 2.5 × 105 Da | (Llamas et al., 2010) |

| 90 | Shigella dysenteriae | – | – | – | – | aFucose/rhamnose | – | (Gehrke, Telegdi, Thierry, & Sand, 1998) |

| 91 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | – | – | – | – | aFucose/rhamnose | – | (Graber et al., 1988) |

| 92 | Streptococcus thermophilus MR-1C | – | Skim milk powder supplemented with a mixture of amino acids | 40 °C/1 d | – | Galactose/rhamnose/fucose = 5/2/1 (by molar ratio) | – | (Low et al., 1998) |

| 93 | Streptomyces sp. A-1845 | Soil sample | Glucose, corn starch, soybean meal and yeast extract | 25 °C/5–6 d | 0.785 g/L | Mannose/galactose/galacturonic acid/xylose/glucosamine/rhamnose/glucose/fucose/ribose/galactosamine = 7.6/4/3.4/3.1/2.6/1.9/1.7/1.1/1/0.6 (by molar ratio) | 1 × 106 Da | (Inoue, Murakawa, & Endo, 1992) |

| 94 | Thiobacillus ferrooxidans | – | – | – | Rhamnose/fucose/xylose/mannose/glucose/glucuronic acid = 13.9/20.5/0.9/0.4 /11.4/4.4 (by molar ratio) | – | (Graber et al., 1988) | |

| 95 | Vibrio sp. QY101 | A decaying thallus of Laminaria | – | 25 °C/4 d | – | Rhamnose/galacturonic acid/glucuronic acid/glucosamine/galactose/glucose/fucose/mannose = 23.90/23.05/21.47/12.15/6.89/6.57/3.61/2.36 (by molar percentage) | 5.46 × 105 Da | (Jiang et al., 2011) |

| 96 | Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | – | – | – | – | aFucose/rhamnose | – | (Graber et al., 1988) |

limited information of monosaccharide compositions according to available references.

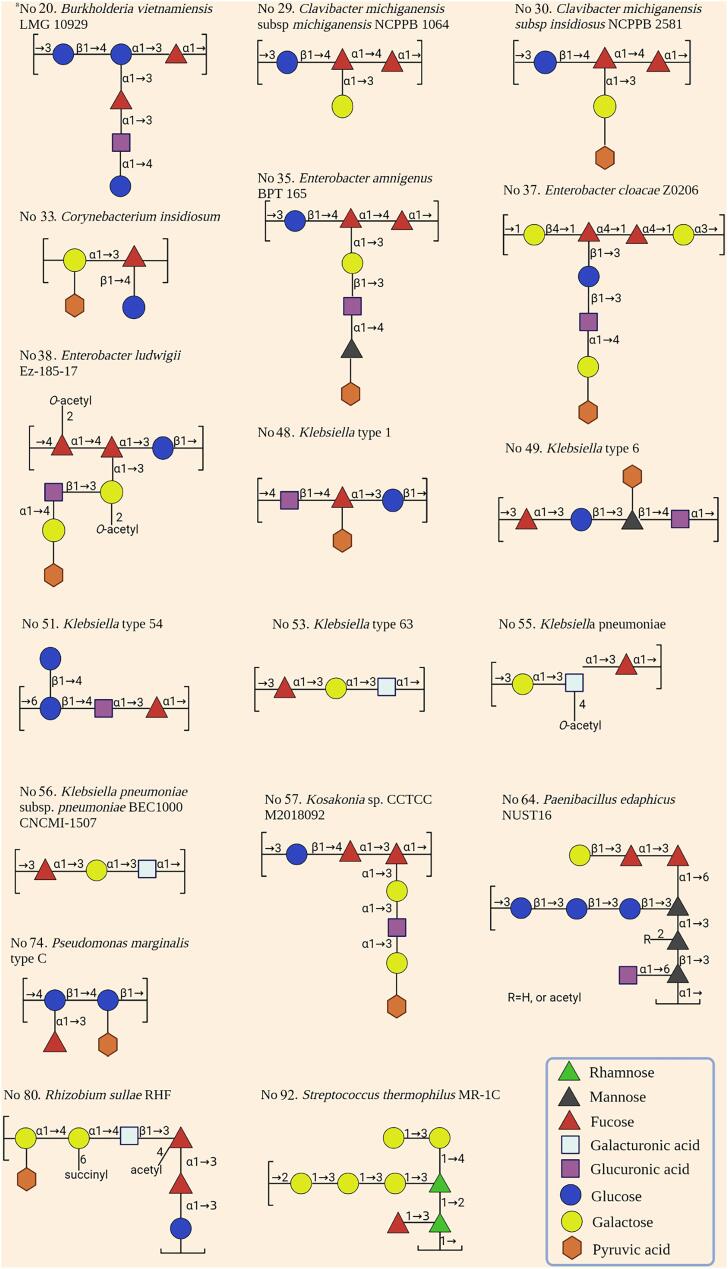

Fig. 2.

The repeating units structure of bacterial fucose-containing exopolysaccharides (FcEPS) produced by some bacteria. aThe No. refers the serial number of each reported FcEPS-producing strains in Table 1.

FcEPSs-producing bacteria

Bacteria capable of producing FcEPSs mainly include Enterobacter sp., Clavibacter sp., and Klebsiella sp. Enterobacter sp., a gram-negative bacterium, is widely distributed in the natural environment and has a wide host range. Enterobacter sp. has shown a strong adaptability to both abrupt changes in the environment and bio-contamination, as well as good proliferation and differentiation capabilities. Several species within the genus Enterobacter have been reported to produce EPS containing fucose. The EPS secreted by Enterobacter sp. A47 (DSM 23139), named FucoPol, is a high molecular weight polymer composed of fucose, galactose, glucose, and glucuronic acid at a ratio of 4:2.5:3:1 (Freitas et al., 2011). The marine bacteria E. cloacae and E. amnigenus can produce heteropolymers containing glucose, galactose, fucose, mannose, glucuronic acid, and pyruvil (Cescutti et al., 2005, Iyer et al., 2005). FcEPS is commonly obtained by liquid fermentation of E. sakazakii strains, including ATCC 53017, ATCC 29004, and ATCC 12868 (Vanhooren & Vandamme, 1999). In addition, a previous study showed that FcEPS extracted from E. sakazakii M1 was mainly composed of fucose, galactose, and glucose, in which the content of fucose reached 42.72 mol% (Xiao et al., 2021).

C. michiganensis subsp. is a plant pathogenic bacterium that spreads through the xylem, leading to bacterial wilt and canker in tomato and other plants (Gartemann et al., 2003). The EPS produced by C. michiganensis subsp. may protect bacteria by inhibiting the plant defense system and is conducive to the adhesion of bacteria on the plant surface, thus promoting the infection and colonization of host plants. The EPS, named Clavan, is a repeated-unit tetrasaccharide containing glucose, galactose, fucose, and pyruvate and is produced by C. michiganensis strains (Bulk, Zevenhuizen, Cordewener, & Dons, 1991). For example, C. m. subsp. michiganensis NCPPB 1574, C. m. subsp. nebraskensis NCPPB 2581, C. m. subsp. insidious NCPPB 1686, and C. m. subsp. sepedonicus NCPPB 2140 are all capable of producing FcEPSs, with fucose content of 46.6, 28.5, 43.7, and 20.9 mol%, respectively (Bermpohl et al., 1996, Bulk et al., 1991).

Colanic acid is a type of FcEPS generally produced by members of Enterobacteriaceae, including Escherichia and Klebsiella spp. (Rättö et al., 2006). Klebsiella sp. is a special gram-negative bacterium. Its polysaccharide capsule surrounds the cell wall, leading to the formation of K-antigen. All K-antigens of Klebsiella strains have been divided into 82 different types, in which only six strains have been reported to contain fucose, namely, K1, K6, K16, K54, K60 and K63 (Rieger-Hug & Stirm, 1981). The EPSs of several K. pneumoniae strains (ATCC 12657, 4208, 13886, 31646, and 31488) were reported to contain fucose (Vanhooren & Vandamme, 1999). Fucogel, an EPS prepared by fermentation of K. pneumoniae strain I-1507, is a high-viscosity polysaccharide developed by BioEurope and sold by Solabia. Fucogel has been used in the cosmetics industry because of its soft psychosensorial qualities, hydration, and emulsifying properties (Guetta, Mazeau, Auzely, Milas, & Rinaudo, 2003).

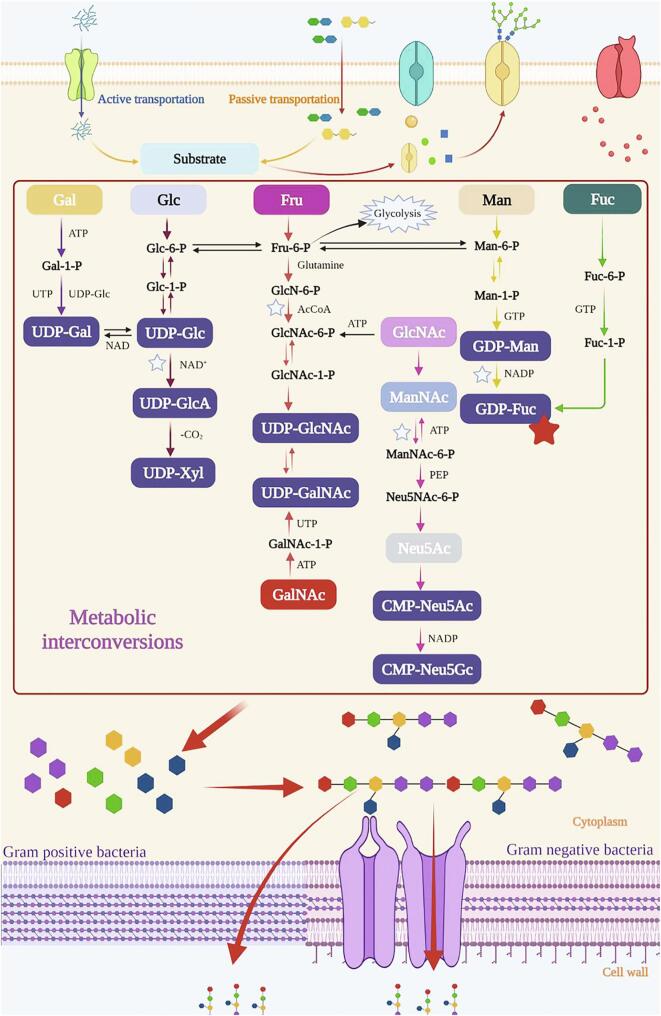

Synthesis of FcEPS

FcEPS is commonly composed of fucose, glucose, galactose, mannose, rhamnose, and uronic acid. FcEPS can be synthesized by combining the intracellular and extracellular pathways, as shown in Fig. 3. In general, the biosynthesis of FcEPS occurs in four steps (Chaisuwan et al., 2020, Freitas et al., 2011). First, the nutrients in the extracellular environment enter the cells via active or passive transport and are transformed into different monosaccharides. When glucose is used as the carbon source, it is converted into glucose-6-phosphate under the action of glucokinase; three pathways are then used to synthesize the nucleotide sugar: (i) glucose-6-phosphate is converted into glucose-1-phosphate under the action of α-phosphoglucomutase, from which UDP-glucose, UDP-glucuronic acid, UDP-xylose, and UDP-galactose are synthesized; (ii) glucose-6-phosphate is converted to mannose-6-phosphate through phosphomannose mutase, followed by the production of GDP-mannose and GDP-fucose; and (iii) fructose-6-phosphate is produced from glucose-6-phosphate by phosphoglucose isomerase, and then glucosamine-6-phosphate, N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate, and UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine are obtained step by step (Jiang & Yang, 2018). According to Fig. 3, GDP-fucose can be obtained through the conversion of a variety of monosaccharides. Second, monosaccharides are bound to a lipid carrier located in the cytoplasmic membrane. Thereafter, repeated units were formed by the linkage of different monosaccharides and extended into high molecular weight polysaccharides. Finally, these high molecular weight polysaccharides are secreted outside the cell to form FcEPS. In the last step, the polysaccharide must pass through the cell membrane without damaging its barrier characteristics. In the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria, FcEPS could be secreted out of the cells following the Wzx-Wzy-dependent pathway, in which the repeating units are assembled at the inner face of the cytoplasmic membrane and polymerized at the periplasm, or ABC transporter-dependent pathway, in which polymerization occurs at the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane (Barcelos et al., 2019).

Fig. 3.

Abbreviated diagram summarizing the biosynthetic pathways related to the synthesis of bacterial FcEPS by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria.

Factors affecting FcEPS production

The characteristics of FcEPS are mainly determined by the genetic factors of producing bacteria. The ability to produce different FcEPSs under the same culture conditions was exhibited within different strains of bacteria, although they belonged to the same species and genus, such as Bacillus licheniformis BioE-BL11 and T8; Bifidobacterium longum H73 and H63; and C. m. subsp. michiganensis strains (Bermpohl et al., 1996, Kook et al., 2019, Salazar et al., 2009). In addition, two or more kinds of FcEPSs may be synthesized by the same strain at the same time, although these FcEPSs exhibit different characteristic properties (molecular weight and monosaccharide composition) and activities; such FcEPSs can be produced by Bacillus sp. T14, L. plantarum KX041, L. plantarum JLAU103, and L. gasseri FR4 (Spanò et al., 2013, Gugliandolo et al., 2012, Min et al., 2018, Rani et al., 2018, Xu et al., 2019).

The production of FcEPS is highly influenced by the medium composition and culture conditions. The structure and yield of FcEPS are commonly related to the type of carbon sources in the culture medium. Taking the FcEPS produced by Enterobacter sp. A47 as an example, the yield produced using glucose as the main carbon source was 2.48-fold higher than that using xylose, whereas the molar proportion of fucose in the FcEPS produced using glucose as the main carbon source was lower than that using xylose (Freitas et al., 2014). Sugars are frequently used as a carbon source during the fermentation of FcEPS, and some cheaper substitutes have been shown as valuable for bacterial production of FcEPS. For example, the maximum FcEPS production of Enterobacter sp. A47 (13.3 g/L) was reached with glycerol used as the carbon source, whereas using out-of-specification tomato paste as the carbon source led to a maximum FcEPS production of 8.77 g/L (Antunes et al., 2017, Cruz et al., 2011). These low-cost materials are suitable carbon sources for the production of FcEPS to reduce the cost of industrial production. The existence of an excess carbon source is conducive to the synthesis of FcEPS, which is further limited by the nitrogen source and oxygen (Miqueleto, Dolosic, Pozzi, Foresti, & Zaiat, 2010). And the production of FcEPS is commonly performed under aerobic conditions. FcEPS can be synthesized throughout the logarithmic and stable phases of bacterial growth. However, the maximum yield of FcEPS generally occurs in the late logarithmic phase, rather than in the stable phase (Freitas et al., 2011).

FcEPSs served as new sources of FCOs

FcEPSs with high yield and diverse structures can be obtained by liquid fermentation of specific bacteria. FCOs are then prepared by depolymerizing FcEPSs using suitable degradation tools. Chemical degradation methods (acid hydrolysis and oxidative degradation) are commonly used for the preparation of oligosaccharides. Hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, and trifluoroacetic acid are widely used in acid hydrolysis degradation processes, while sodium periodate and hydrogen peroxide are common oxidants used to produce oligosaccharides (Cescutti et al., 2005, Wei et al., 2012). However, chemical degradation methods are usually performed at high concentrations and temperatures, leading to the production of more monosaccharides.

Enzymatic methods are more efficient and mild in comparison with chemical degradation methods. Enzymes capable of degrading EPS are usually produced in three ways. First, endogenous enzymes secreted by host EPS-producing bacterial strains (Lelchat, Cozien, Costaouec, Brandilly, & Boisset, 2014). Second, exogenous enzymes produced by other bacterial strains (Li et al., 2019). Third, polysaccharides depolymerases from phage particles or phage-induced bacterial lysates. Glycanase produced during phage infection of host EPS-producing bacteria has lytic effects on the EPS secreted by that host bacteria, which is conducive to the adsorption and infection of the phage (Xiao et al., 2021). Bacteriophage-borne glycanase is a promising tool for the preparation of FCOs. Based on the effective degradation effect of bacteriophage-borne glycanase on EPS, the structures of some FcEPSs produced by Klebsiella. sp. strains have been characterized (Rieger-Hug and Stirm, 1981, Shang et al., 2014). Moreover, two FCOs with new structures were successfully obtained via degradation of the FcEPS produced by E. sakazakii M1 by bacteriophage-borne glycanase (Xiao et al., 2021).

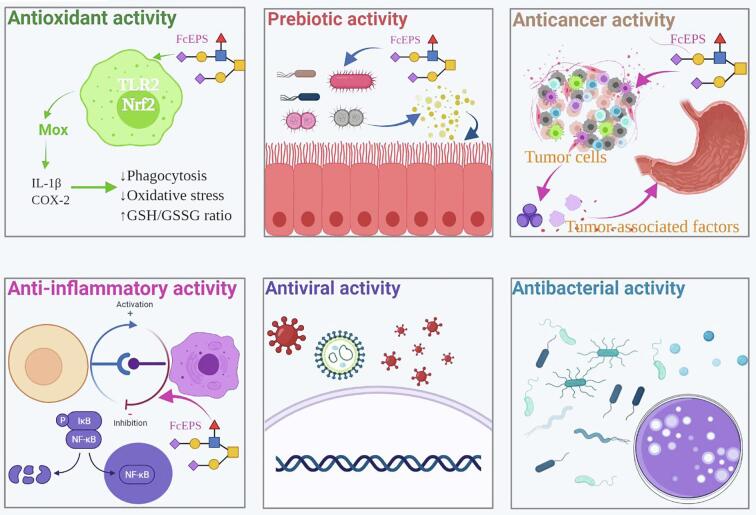

Activities and applications of FcEPSs

Although FcEPSs have been applied in the cosmetic, food, medicine, and environmental remediation industries, applications related to health will become an important trend in the future of FcEPSs development. Accumulating evidence has shown that FcEPSs exert various biological activities, including anti-oxidant, prebiotic, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-viral, and anti-microbial activities (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The main functional activities of bacterial FcEPS, including anti-oxidant, prebiotic, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-viral and anti-microbial activities.

Anti-oxidant activity

The overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) may result in oxidative stress and free radical-induced oxidation, leading to a series of diseases, such as diabetes, inflammatory and neurological diseases (Rani et al., 2018). Natural materials could serve as a highly promising source of anti-oxidants, especially polysaccharides obtained from plants, animals, and microorganisms.

Many studies have demonstrated the anti-oxidant activity of FcEPSs in vitro. FcEPSs prepared from bacteria exhibited anti-oxidant activity mainly by scavenging free radicals, including 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), hydroxyl, 2,2′-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonate (ABTS), superoxide radicals, etc. Three Lactobacillus strains, L. plantarum KX041, L. plantarum JLAU103, and L. gasseri FR4, displayed strong anti-oxidant activities against DPPH, ABTS, superoxide, and hydroxyl radicals, thus demonstrating their potential to reduce oxidation (Min et al., 2018, Rani et al., 2018, Xu et al., 2019). The FcEPSs of B. licheniformis T8, Polaribacter sp. SM1127, Microbacterium aurantiacum FSW-25, and Zunongwangia profunda SM-A87 also exhibited similar anti-oxidant activity by scavenging free radicals (Sran et al., 2019, Sun et al., 2015, Xu et al., 2019). Among them, two FcEPSs of B. licheniformis T8, BL-P1 (3.96 × 106 Da) and BL-P2 (1.23 × 105 Da), showed strong scavenging ability to DPPH and hydroxyl radicals. The scavenging abilities of the two EPSs increased with increasing concentrations until the maximum scavenging rate reached 62.33% and 67.31% at 140 μg/mL, respectively, indicating that FcEPS with low molecular weights may demonstrate better anti-oxidant activity than high molecular weight FcEPS (Xu et al., 2019).

The anti-oxidant activities of FcEPSs are influenced by their fucose content. Two EPSs, high-fucose-content EPS (41.89%) and low-fucose-content EPS (4.9%), are biosynthesized by B. megaterium RB-05 under two different fermentation processes, and high-fucose-content EPS exhibited better free radical scavenging activities than low-fucose-content EPS. High-fucose-content EPS can directly eliminate intracellular ROS induced by hydrogen peroxide and reduce oxidative stress in WI38 cells by regulating the Nrf2/Keap1 signaling pathway and cytoprotective genes related to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and mitochondrial-mediated pathways (Chowdhury et al., 2014). Anti-oxidant enzymes also play a vital role in preventing oxidative stress by catalyzing the stable formation of free radicals. Two fungal EPS (ALF1 and ALF2) were prepared from the fermentation liquid of Floccularia luteovirens but only ALF1 contained fucose. ALF1 exerts antioxidant activity by improving the activity of superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and catalase (Liu, Jiao, Lu, Shu, & Chen, 2020). Antioxidation is one of the most valuable properties of FcEPS, resulting in its potential application prospects in the food, medicine, and cosmetic fields.

Prebiotic activity

Prebiotics are beneficial for improving the intestinal health of the host by selectively stimulating the growth or metabolism of one or more bacteria in the colon (Gibson, Probert, Loo, Rastall, & Roberfroid, 2004). A FcEPS was prepared from a gene-recombinant E. coli with overexpression of the gene cluster ycjD-fabI-yciW-rnb, and the interaction of this FcEPS with gut microbiota was evaluated. The results showed that>96% of FcEPS could be degraded and utilized by the gut microbiota in human feces after 72 h of fermentation, with the enrichment of the genera Collinsella, Butyricimonas, and Hafnia. In addition, more short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) can be produced by human fecal microbiota using FcEPS as the carbon source than using starch as the carbon source (Li, Chen, Cao, Hu, & Yin, 2019). Other FCPs, for example, fucoidans, extracted from brown algae and sea cucumber also exhibited prebiotic activity. Fucoidans extracted from Laminaria spp. play a positive role in regulating intestinal microbiota by increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria (especially Lactobacilli spp.) in the intestine and the concentration of SCFAs in the colon, which has been proved to alleviate dyslipidemia and obesity caused by high-fat diet. Similarly, fucoidans extracted from Acaudina molpadioides are also effective in repairing the intestinal mucosal barrier damage caused by cyclophosphamide treatment through improving the expression of tight junction protein, promoting the production of SCFAs (particularly propionate and butyrate), and increasing the abundance of SCFAs-producing bacteria, such as Coprococcus, Rikenella, and Butyricicoccus species (Li et al., 2020).

Anti-cancer/anti-tumor activity

Despite advanced technology and in-depth research, cancer is still the largest cause of death worldwide and is caused by the uncontrolled division of cells. FcEPS, as a natural material, serves not only as a functional food product but also as a source of anti-tumor drugs (Hu, Li, Qiao, Wang, & Huang, 2019).

Colon cancer, further affecting other organs and tissues, is the most common type of cancer. Two FcEPSs with different fucose contents and molecular weights have been prepared from L. casei SB27, a strain isolated from yak milk obtained from the Gansu Tibetan region of China. In vitro anti-tumor tests showed that both FcEPSs could significantly inhibit the proliferation of HT-29 colorectal cancer cells and upregulate the expression of Bad, Bax, Cas3, and Cas8 genes (Di et al., 2017).

Leukemia is a serious disease caused by malignant cloning of hematopoietic stem cells, also known as “blood cancer”. Ruiz-Ruiz et al. (2011) screened a new type of halophilic bacterium and studied the anti-tumor activity of its EPS. This EPS is a miscellaneous polysaccharide containing fucose, which has anti-tumor activity against T-cells in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Only tumor cells were susceptible to apoptosis, whereas primary T-cells were resistant. The newly discovered EPS was the first bacterial EPS shown to have an effective and selective pro-apoptotic effect on leukemia T-cells. Umezawa et al. (1983) obtained a FcEPS from Flavobacterium uliginosum inhabiting the ocean and studied its anti-tumor activity against mouse sarcoma 180 solid tumors. Complete tumor regression was observed in some mice treated with FcEPS indicating it could prolong the survival of tumor mice. And some fungal FcEPSs also demonstrated anti-cancer activities. The anti-cancer effects of FcEPS extracted from Trichoderma pseudokoningii on human leukemia K562 cells were also studied. The findings showed that FcEPS could induce the apoptosis of K562 cells, mainly involving the mitochondrial pathway, suggesting that EPS may become a new potential adjuvant chemotherapeutic agent against human leukemia (Huang et al., 2012). In addition, another study reported the anti-cancer activity of FcEPS prepared from T. pseudokoningii on human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. These findings suggested that FcEPS induced the apoptosis of MCF-7 cells through an intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and that FcEPS may serve as an effective drug against human breast cancer (Wang, Liu, Liu, Bo, & Chen, 2016). Two EPSs, ALF1 with 13.86% fucose and ALF2 without fucose, were prepared from the fermentation liquid of Floccularia luteovirens, and the proliferation of tumor cells was inhibited by ALF1 without affecting the metabolic proliferation of normal cells (Liu et al., 2020).

Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation is a response of the host immune system to viral infection and tissue damage, and may cause leukocyte accumulation and plasma protein leakage through blood vessels. Long-term inflammatory reactions may lead to inflammatory diseases or cancer. Many studies have reported that EPS could serve as an immune regulator of the anti-inflammatory response of the immune system, in which the regulatory mechanism may be that some EPS with specific components and branches or high molecular weight may inhibit the immune response (Chaisuwan et al., 2020). However, further research is needed to understand the detailed mechanism.

Macrophages play an important role in the host immune defense system against various infections and cancers by secreting several mediators, such as nitric oxide, tumor necrosis factor α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and prostaglandin E2. RAW264.7 macrophages, which are commonly used in immune studies, can be activated by EPS, leading to the proliferation of macrophages, improvement of phagocytic phagocytosis, and secretion of cytokines (Min et al., 2018, Wang et al., 2020). Two FcEPSs with fucose contents of 37.1% and 10.21% were prepared from B. licheniformis BioE-BL11 and L. mesenteroides BioE-LMD18, respectively. Both FcEPSs inhibited the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 mouse macrophage with the inhibition rate of 40.7% and 32.1%, respectively, and enhanced the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in a dose-dependent manner (Kook et al., 2019). L. plantarum, as a probiotic strain, is capable of producing FcEPS, which also has strong immunomodulatory activity. The release of IL-6, tumor necrosis factor α, and nitric oxide by RAW264.7 were enhanced by the FcEPS of L. plantarum JLAU103 through the NF-κB signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2020). Another study also showed that FcEPS purified from the fermentation broth of L. plantarum KX041 also has potential immunomodulatory activity (Xu et al., 2019).

According to previous studies, FcEPS of T. pseudokoningii demonstrated not only anti-tumor activity but also immunomodulatory activity, which was attributed to the activation of toll-like receptor-4 and dectin-1 specific antibodies by FcEPS through the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, thereby inhibiting the secretion of cytokines (Wang et al., 2016). Moreover, FcEPS of T. pseudokoningii exhibited the ability to induce morphological changes in dendritic cells and enhance the expression of the dendritic cell surface characteristic molecules CD11c, CD86, CD80, and major histocompatibility complex II, which is also associated with NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways (Xu et al., 2016). These characteristics indicate that FcEPS is a promising anti-inflammatory agent.

Anti-viral and anti-microbial activity

Viral diseases are commonly targeted by vaccination, chemoprevention, and chemotherapy. Bacterial EPS, as natural products, are potential anti-viral drugs. Arena et al. (2006) isolated a heat-resistant strain, B. licheniformis, from marine hot springs and evaluated the immunomodulatory effects of its FcEPS. The results showed that the replication of HSV-2 in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) was blocked after treating with FcEPS. Moreover, both Th1 and Th2 cytokines were detected in the PBMCs supernatant, indicating that the anti-viral effect of FcEPS on PBMCs was related to the pattern of cytokines induced. In addition, another study reported the anti-viral and immunomodulatory effects of FcEPS obtained from B. licheniformis T14 on HSV-2; however, only Th1 cytokines were detected in the FcEPS-treated PBMCs supernatant (Gugliandolo, Spanò, Lentini, Arena, & Maugeri, 2014).

There are few studies on the anti-bacterial activity of FcEPSs. The FcEPS produced by L. gasseri FR4 exhibited anti-bacterial activity against E. coli MTCC 2622, Listeria monocytogenes MTCC 657, Staphylococcus aureus MTCC 3160, and Enterococcus faecalis MTCC 439, with the maximum inhibitory effect on Listeria monocytogenes MTCC 657 (Rani et al., 2018). The anti-bacterial effect of FcEPS produced by L. gasseri FR4 is related to the prevention of biofilm formation. An EPS containing fucose produced by B. licheniformis T14 also showed anti-bacterial and anti-biofilm properties against E. coli 463, K. pneumonia 2659, P. aeruginosa 445, and Staphylococcus aureus 210 (Spanò, Laganà, Visalli, Maugeri, & Gugliandolo, 2016). The biofilm formed by a wide range of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria could be inhibited by the FcEPS of Vibrio sp. QY101, although the FcEPS had no anti-bacterial activity (Jiang et al., 2011). In addition, the anti-bacterial activity of the hybrid film containing FcEPS prepared from Kosakonia sp. CCTCC M2018092 and partially acid-hydrolyzed FcEPS on Staphylococcus aureus were confirmed (Li et al., 2020). Taken together, FcEPS has good potential for developing new anti-viral, anti-bacterial, or degrading anti-bacterial membrane materials.

Applications of FcEPSs in food

FcEPSs have important applications in various industries owing to their anti-oxidant, prebiotic, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and anti-viral activities. In addition, the emulsification, pseudoplasticity, and stability of FcEPSs also provide the possibility for their applications in the food industry.

FcEPSs have potential applications in the food industry by stabilizing emulsions between water and hydrophobic materials (Freitas et al., 2011). Natural biological emulsifiers have the advantages of degradability, low toxicity, selectivity, and environmental compatibility compared to artificial emulsifiers (Mata et al., 2008). The activity of FcEPS extracted from Pseudomonas sp. ID1 against different food and cosmetic oils was much higher than commercial polysaccharides, such as xanthan gum and gum arabic. Emulsifying activity is a common property of the FcEPSs produced by Enterobacter sp. A47, Salipiger mucosus A3T, B. coagulans RK-02, Gracilibacillus sp. SCU50, P. mendocina P2d, and P. oleovorans NRRL B-14682 (Alves et al., 2010, Freitas et al., 2011, Gan et al., 2020, Kodali et al., 2009, Llamas et al., 2010, Royan et al., 1999). However, emulsifiers may be exposed to high or low temperatures, high or low pH, and high salinity during food processing (Freitas et al., 2009). Research has shown that FcEPS produced by Enterobacter sp. A47 is stable within a wide range of pH and temperatures (Cruz et al., 2011). The degradation temperature of the FcEPS produced by Rhodococcus erythropolis HX-2 reached 255.4 °C (Hu et al., 2019). The FcEPSs produced by low temperature-resistant strains, Polaribacter irgensii CAM006, Pseudoortermomonas sp. CAM003 and CAM025, could be served as cryoprotectants (Nichols, Bowman, & Guezennec, 2005). Another study suggested that the FcEPS of B. licheniformis T14 exhibited better thermal stability, which may be correlated with the presence of fucose (Caccamo et al., 2018).

Pseudoplastic rheological behavior is another common characteristic of FcEPS. Polysaccharides with better pseudoplasticity could be used in the preparation of different types of food, such as dairy products, cakes, syrups, and pudding. The pseudoplasticity of FcEPS is conducive to the perception of comfort when eating food (Antunes, Freitas, Alves, Grandfils, & Reis, 2015). Most FcEPSs have a high molecular weight (>100 kDa) and high viscosity and can serve as thickeners in the food industry. Several probiotics (L. plantarum H2, L. rhamnosus E41, and L. rhamnosus E43R) were isolated from human intestinal microbiota, and the FcEPSs of these strains could increase the viscosity of fermented milk, indicating their good viscosity-intensifying properties (Salazar et al., 2009).

Many studies have discussed potential biomedical and food applications from FcEPSs but only some outstanding results are reviewed here. However, whether these molecules can be marketed in food and pharmaceutical fields needs to be further evaluated. Unfortunately, few studies have determined the relationship between the structures and activities of FcEPSs, and the conclusions cannot be widely used. This paper systematically summarized the activities of FcEPSs to provide a research basis for the structure–activity relationship, which is also decisive for their potential application. In addition, the activity of natural products such as EPS needs to be simulated in animals before clinical development and application; however, so far, these aspects have been seldom studied.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Fucose and FCOs play a vital role in food industry application owing to their specific activities and physicochemical properties. However, the complexity and high cost of chemical synthesis of fucose or FCOs make them unable to meet the demands of large-scale industrial production. FcEPS could serve as a promising source of fucose and FCOs. To date, chemical degradation and enzymatic hydrolysis are effective means to degrade FcEPS for the preparation of FCOs, especially bacteriophage-borne glycanases.

FcEPSs produced by microorganisms have great development potential with regard to food, cosmetics, and medical applications in comparison with other natural materials. In addition, FcEPSs have various important functions, including anti-oxidant, prebiotic, anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-viral, and anti-microbial activities. The preparation, structural analysis, and functions of FcEPSs have been extensively explored over the past several years. However, the relationships between the structural characteristics and bioactivities of FcEPSs are still not fully established owing to the structural diversity and complexity of FcEPSs. Well-designed researches on the structure–activity relationship of FcEPSs are needed, which may serve as a reference strategy for the further applications of fucose-containing carbohydrates in the functional food and medicine industries.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872893) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M701547).

Contributor Information

Mengshi Xiao, Email: 18227591863@163.com.

Xinmiao Ren, Email: m13992623179@163.com.

Ying Yu, Email: yingmm1997@163.com.

Wei Gao, Email: 18864801157@163.com.

Changliang Zhu, Email: chlzhu@163.com.

Han Sun, Email: shlyg2242@163.com.

Qing Kong, Email: kongqing@ouc.edu.cn.

Xiaodan Fu, Email: luna_9303@163.com.

Haijin Mou, Email: mousun@ouc.edu.cn.

References

- Alves V.D., Freitas F., Costa N., Carvalheira M., Oliveira R., Gonçalves M.P., et al. Effect of temperature on the dynamic and steady-shear rheology of a new microbial extracellular polysaccharide produced from glycerol byproduct. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2010;79(4):981–988. [Google Scholar]

- Amjres H., Béjar V., Quesada E., Carranza D., Abrini J., Sinquin C., et al. Characterization of haloglycan, an exopolysaccharide produced by Halomonas stenophila HK30. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2015;72:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes S., Freitas F., Alves V.D., Grandfils C., Reis M.A.M. Conversion of cheese whey into a fucose- and glucuronic acid-rich extracellular polysaccharide by Enterobacter A47. Journal of Biotechnology. 2015;210:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antunes S., Freitas F., Sevrin C., Grandfils C., Reis M.A. Production of FucoPol by Enterobacter A47 using waste tomato paste by-product as sole carbon source. Bioresource Technology. 2017;227:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arena A., Maugeri T.L., Pavone B., Iannello D., Gugliandolo C., Bisignano G. Antiviral and immunoregulatory effect of a novel exopolysaccharide from a marine thermotolerant Bacillus licheniformis. International Immunopharmacology. 2006;6(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelos M.C.S., Vespermann K.A.C., Pelissari F.M., Molina G. Current status of biotechnological production and applications of microbial exopolysaccharides. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2019;60(9):1475–1495. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1575791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D.J., Lowe J.B. Fucose: Biosynthesis and biological function in mammals. Glycobiology. 2003;13(7):41R–53R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermpohl A., Dreier J., Bahro R., Eichenlaub R. Exopolysaccharides in the pathogenic interaction of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis with tomato plants. Microbiological Research. 1996;151(4):391–399. [Google Scholar]

- Bode L. The functional biology of human milk oligosaccharides. Early Human Development. 2015;91(11):619–622. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulk R.W.V.D., Zevenhuizen L.P.T.M., Cordewener J.H.G., Dons J.J.M. Characterization of the extracellular polysaccharide produced by Clavibacter michiganensis supsp. michiganensis. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry. 1991;81(6):619–623. [Google Scholar]

- Bych K., Mikš M.H., Johanson T., Hederos M.J., Vigsnæs L.K., Becker P. Production of HMOs using microbial hosts-from cell engineering to large scale production. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2019;56:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo M.T., Zammuto V., Gugliandolo C., Madeleine-Perdrillat C., Spanò A., Magazù S. Thermal restraint of a bacterial exopolysaccharide of shallow vent origin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018;114:649–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R.A., Surayot U., You S.G. Structural characterization of immunostimulating protein-sulfated fucan complex extracted from the body wall of a sea cucumber, Stichopus japonicus. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2017;99:539–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrión O., Delgado L., Mercade E. New emulsifying and cryoprotective exopolysaccharide from Antarctic Pseudomonas sp. ID1. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2015;117:1028–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro L., Zhang R., Muñoz J.A., Gonzáleza F., Blázqueza M.L., Sand W., et al. Characterization of exopolymeric substances (EPS) produced by Aeromonas hydrophila under reducing conditions. Biofouling. 2014;30(4):501–511. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2014.892586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cescutti P., Cuzzi B., Herasimenka Y., Rizzo R. Structure of a novel exopolysaccharide produced by Burkholderia vietnamiensis, a cystic fibrosis opportunistic pathogen. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2013;94(1):253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cescutti P., Kallioinen A., Impallomeni G., Toffanin R., Pollesello P., Leisola M., et al. Structure of the exopolysaccharide produced by Enterobacter amnigenus. Carbohydrate Research. 2005;340(3):439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaisuwan W., Jantanasakulwong K., Wangtueai S., Phimolsiripol Y., Chaiyaso T., Techapun C., et al. Microbial exopolysaccharides for immune enhancement: Fermentation, modifications and bioactivities. Food Bioscience. 2020;35 [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Hu Y., Long Y., Mcclements D.J., Xue C. Primary structure and chain conformation of fucoidan extracted from sea cucumber Holothuria tubulosa. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2016;136:1091–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S.R., Basak R.K., Sen R., Adhikari B. Production of extracellular polysaccharide by Bacillus megaterium RB-05 using jute as substrate. Bioresource Technology. 2011;102(11):6629–6632. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S.R., Sengupta S., Biswas S., Sinha T.K., Sen R., Basak K.R., et al. Bacterial fucose-rich polysaccharide stabilizes MAPK-mediated Nrf2/Keap1 signaling by directly scavenging reactive oxygen species during hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis of human lung fibroblast cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costaouëc T.L., Cérantola S., Ropartz D., Ratiskol J., Sinquin C., Colliec-Jouault S., et al. Structural data on a bacterial exopolysaccharide produced by a deep-sea Alteromonas macleodii strain. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2012;90(1):49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz M., Freitas F., Torres C., Reis M., Alves V.D. Influence of temperature on the rheological behavior of a new fucose-containing bacterial exopolysaccharide. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2011;48(4):695–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D.A. The specific polysaccharides of some gram-negative bacteria. The Biochemical Journal. 1955;59(4):696–704. doi: 10.1042/bj0590696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di W., Zhang L., Wang S., Yi H., Han X., Fan R., et al. Physicochemical characterization and antitumour activity of exopolysaccharides produced by Lactobacillus casei SB27 from yak milk. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2017;171:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Li X., Du G., Chen J. Characterization and fouling properties of exopolysaccharide produced by Klebsiella oxytoca. Bioresource Technology. 2009;100(13):3387–3394. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fett W.F., Wells J.M., Cescutti P., Wijey C. Identification of exopolysaccharides produced by Fluorescent pseudomonads associated with commercial mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) production. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1995;61(2):513–517. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.513-517.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman M.L., Cescutti P., Fett W.F., Osman S.F., Hoagland P.D., Chau H.K. Screening the physical properties of novel Pseudomonas exopolysaccharides by HPSEC with multi-angle light scattering and viscosity detection. Carbohydrate Polymers. 1997;32(3–4):213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas F., Alves V.D., Gouveia A.R., Pinheiro C., Torres C., Grandfils C., et al. Controlled production of exopolysaccharides from Enterobacter A47 as a function of carbon source with demonstration of their film and emulsifying abilities. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2014;172(2):641–657. doi: 10.1007/s12010-013-0560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas F., Alves V.D., Pais J., Costa N., Oliveira C., Mafra L., et al. Characterization of an extracellular polysaccharide produced by a Pseudomonas strain grown on glycerol. Bioresource Technology. 2009;99(2):859–865. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas F., Alves V.D., Reis M.A.M. Advances in bacterial exopolysaccharides: From production to biotechnological applications. Trends in Biotechnology. 2011;29(8):388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas F., Alves V.D., Torres C.A.V., Cruz M., Sousa I., Melo M.J., et al. Fucose-containing exopolysaccharide produced by the newly isolated Enterobacter strain A47 DSM 23139. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2011;83(1):159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gan L., Li X., Wang H., Peng B., Tian Y. Structural characterization and functional evaluation of a novel exopolysaccharide from the moderate halophile Gracilibacillus sp. SCU50. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;154:1140–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Guo Y., Wang L., Jiang Y., Liu Z., Lin H., et al. Ameliorative and protective effects of fucoidan and sodium alginate against lead-induced oxidative stress in Sprague Dawley rats. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2020;158(2):662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.04.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartemann K.H., Kirchner O., Engemann J., Grfen I., Eichenlaub R., Burger A. Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis: First steps in the understanding of virulence of a Gram-positive phytopathogenic bacterium. Journal of Biotechnology. 2003;106(2–3):179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke T., Telegdi J., Thierry D., Sand W. Importance of extracellular polymeric substances from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans for bioleaching. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1998;64(7):2743–2747. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2743-2747.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharzouli R., Carpéné M.A., Couderc F., Benguedouar A., Poinsot V. Relevance of fucose-rich extracellular polysaccharides produced by Rhizobium sullae strains nodulating Hedysarum coronarium L Legumes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2013;79(6):1764–1776. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02903-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G.R., Probert H.M., Loo J.V., Rastall R.A., Roberfroid M.B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Updating the concept of prebiotics. Nutrition Research Reviews. 2004;17(2):259–275. doi: 10.1079/NRR200479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin P.A., Spencer J.F., Lindberg B., Lindh F. Structure of the extracellular polysaccharide from Corynebacterium insidiosum. Carbohydrate Research. 1980;79(2):313–315. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)83846-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber M., Morin A., Duchiron F., Monsan P.F. Microbial polysaccharides containing 6-deoxysugars. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 1988;10(4):198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gross M., Rudolph K. Studies on the extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) produced in vitro by Pseudomonas phaseolicola I. Indications for a polysaccharide resembling alginic acid in seven P. syringae Pathovars. Journal of Phytopathology. 1987;118:216–287. [Google Scholar]