Abstract

Background

Laboratory evidence in the 1940s demonstrated a positive role of placental hormones in the continuation of pregnancy. It was suggested that diethylstilbestrol was the oestrogen of choice for prevention of miscarriages. Observational studies were carried out with apparently positive results, on which clinical practice was based. This led to a worldwide usage of diethylstilbestrol despite controlled studies with contrary findings.

Objectives

To determine the effects of antenatal administration of oestrogens, mainly diethylstilbestrol, on high risk and unselected pregnancy as regards miscarriages and other outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group Specialised Register of controlled trials in November 2002.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised trials were included.

Data collection and analysis

Both reviewers extracted data from the studies identified that met the selection criteria, and the data were analysed using the RevMan software.

Main results

Miscarriage, preterm labour, low birthweight and stillbirth or neonatal death were not positively influenced by the intervention (diethylstilbestrol) as compared to the control group. Diethylstilbestrol in utero exposure led to increased rate of miscarriage and preterm birth. There was also an increase in the numbers of babies weighing less than 2500 grams. The maternal outcome in terms of pre‐eclampsia was not influenced. Exposed female offsprings have a non‐significant trend towards more cancer of the genital tract and cancer other than of the genital tract. Primary infertility, adenosis of the vagina/cervix in female offsprings, and testicular abnormality in male offsprings were significantly higher in those exposed to diethylstilbestrol before birth.

Authors' conclusions

There was no benefit with the use of diethylstilbestrol in preventing miscarriages. Both short and long‐term adverse outcomes in exposed offsprings were demonstration of the harm that this intervention caused women and their offspring during its usage.

Plain language summary

Oestrogen supplementation, mainly diethylstilbestrol, for preventing miscarriages and other adverse pregnancy outcomes

Diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy poses serious long‐term risks for those exposed in the womb and offers no known benefit for mothers and children.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES), an oestrogen, was for decades widely believed to prevent miscarriage and other undesirable outcomes despite a lack of good evidence. A cluster of women with a rare form of vaginal cancer led researchers to associate this, and other adverse outcomes in adults, with their exposure to DES in the womb. This review of trials showed that DES increased the risk of miscarriage, of babies being born too early, and other serious adverse effects in women and men who were exposed in the womb. Results are a warning to avoid this drug in pregnancy.

Background

Over 10% of pregnancies end in miscarriage (Everett 1997). Laboratory evidence in the 1940s was proposed to support the concept that reduced placental hormone production was associated with a variety of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as miscarriage, preterm labour and hypertension in pregnancy (Smith 1941). Animal models suggested that diethylstilbestrol, a synthetic oestrogen, was a suitable therapeutic agent (Pencharz 1940; Smith 1944; Smith 1948). Diethylstilbestrol was thought to cause an increase in placental progesterone secretion because of its stimulatory effects on human chorionic gonadotrophin secretion without responding to negative inhibition by progesterone (Smith 1941; Smith 1944). On the basis of this, a rationale for providing hormone therapy to women in pregnancy, particularly those at risk of miscarriages, was advanced (Smith 1948). Synthetic oestrogens were administered to women, often at an incremental dosage, throughout pregnancy.

The practice was commonplace in parts of USA and Europe until the 1970s, when case control studies suggested an association between exposure before birth to diethylstilbestrol and clear cell carcinoma and adenosis of the vagina and cervix (Herbst 1971; Bibbo 1975; Herbst 1975). The Food and Drug Administration issued a bulletin, a few months after the publication, of a possible adverse effect that diethylstilboestrol was contraindicated in pregnancy and it was withdrawn from being prescribed to pregnant women (FDA 1971). Subsequent data analysis highlighted various possible effects not only in the female offsprings but also amongst the males (Bibbo 1977). The use of diethylstilbestrol continued until the 1980s in some regions of the world.

Diethylstilbestrol usage is now obsolete in modern obstetrics practice. The review is historical to buttress the need for adequate and rigorous research into the use of drugs in pregnancy and ensure that they do more good than harm before being introduced for consumption.

Objectives

This review aims to determine the effects of antenatal administration of oestrogens on pregnancy outcome. The specific objectives are to assess: (1) whether oestrogen administration during pregnancy improves outcome (eg pre‐eclampsia) for the mother; (2) the long‐term effect of oestrogen administration during pregnancy for the mother.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Trials that established a control group prospectively either by randomisation, alternate allocation or quasi randomisation were included in the review.

Types of participants

Pregnant women, regardless of their previous obstetric history or specific risk factors, were included.

Types of interventions

The administration of any oestrogen in pregnancy regardless of gestation, dose, mode of administration or treatment duration.

Types of outcome measures

Outcome measures relating to the pregnancy, baby and mother were collected.

Pregnancy outcomes (1) Baby: miscarriage; preterm birth; birthweight less than 2500 g; stillbirth; neonatal death; congenital anomalies (excluded in error from original protocol). (2) Maternal: pre‐eclampsia.

Long term outcomes (1) Mother: cancer of the genital tract; cancer other than of the genital tract. (2) Female offsprings: cancer of the genital tract; adenosis of vagina and cervix; congenital anomaly; marital status; psychiatric disorders; mortality. (3) Male offsprings: testicular hypotrophy; infertility; marital status; psychiatric disorders.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials register (November 2002).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's trials register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from: 1. quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); 2. monthly searches of MEDLINE; 3. handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences; 4. weekly current awareness search of a further 37 journals.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the 'Search strategies for identification of studies' section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are given a code (or codes) depending on the topic. The codes are linked to review topics. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using these codes rather than keywords.

Data collection and analysis

Assessment of methodological quality Trials were evaluated for quality using the standard Cochrane criteria of adequacy of allocation concealment: adequate (A), unclear (B), inadequate (C) or that allocation concealment was not used (D). Information on single or double blinding of outcome assessment and loss to follow up was collected.

Data collection Data were extracted by both authors and were entered into the RevMan program for analysis. Analysis Categorical outcomes are presented as relative risks and continuous outcomes as weighted mean differences, with 95% confidence intervals for both. Results of trials are combined using a fixed effects model in the absence of significant heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were planned for quality of allocation concealment and different oestrogenic formulations, but appropriate data were not available for these analyses.

Results

Description of studies

See 'Table of included studies'.

Risk of bias in included studies

See 'Table of included studies'. The included trials were conducted in the 1950s, which explains the deficiencies in most of the studies in terms of allocation concealment and lack of adequate randomisation by modern standards

Effects of interventions

Antenatal oestrogen (diethylstilbestrol) was not shown to be of benefit in preventing adverse fetal outcome. The miscarriage rate, preterm labour, birthweight, stillbirth or neonatal death were not positively influenced by the intervention as compared to the control group.

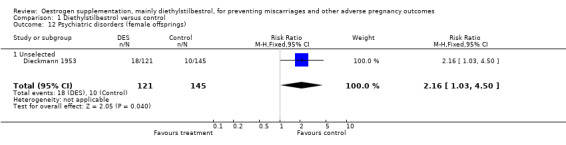

There was a litany of adverse and very harmful consequences. Diethylstilbestrol exposure led to an increased rate of miscarriage and preterm birth. There was also an increase in the numbers of babies weighing less than 2500 grams. The maternal outcomes in terms of pre‐eclampsia and survival of mothers were not influenced. Exposed female offsprings have a non‐significant trend towards more cancer of the genital tract, cancer other than the genital tract and psychiatric disorders. Primary infertility in exposed female offsprings, adenosis of the vagina/cervix and psychiatric disorders in the daughters, and testicular abnormality in exposed male offsprings were significantly higher in those exposed to diethylstilbestrol before birth. There was no difference in marital status between the two groups.

Discussion

The use of diethylstilbestrol (DES) during pregnancy is no longer a clinical issue in the 21st century. However, the lessons to be learnt historically will continue to make the topic a subject of interest for generations to come. The dictum 'do no harm' is relevant to the diethylstilboestrol saga of the 1950s. It was demonstrated physiologically that oestrogens and progesterone were necessary for pregnancy continuation. Thus, it was scientifically logical to postulate that diethylstilboestrol might prevent adverse pregnancy outcome. The sound physiological reasoning and impressive results from non‐randomised studies resulted in enthusiastic uptake of the treatment before it was adequately tested in controlled clinical trials.

Dieckmann 1953 presented his prospective placebo controlled trial in an annual meeting of the American Gynecological Society in 1953, the result of which contradicts the findings of Smith 1948. During discussion time, Smith made a remark: "Our experience with the use of stilbestrol continues to be satisfactory ... we are convinced that it has reduced the complications of late pregnancy and saved many babies". He was at this time an authority in the field and the objective evidence provided by Dieckman was largely ignored. Doctors continued prescribing DES to several million women over the next 20 years. There were no known side effects, and despite lack of objective evidence of effectiveness, both doctors and women were happy with the therapy. With the occurrence of a rare vaginal adenocarcinoma in a cluster of young women in the 1970s, an epidemiological search was mounted that linked its etiology to diethylstilbestrol exposure before birth. Dieckman's paper was revisited, which eventually led to the discovery of several negative outcomes in the offsprings of exposed women.

There is a large loss to follow up in these studies but considering the fact that the Dieckmann trial was 50 years ago, such a large loss is inevitable and these results could be judged valid for the conclusions made in this review. The few randomised trials assessed here are not large enough to show the other more serious side effects attributable to the use of this medication in pregnancy.

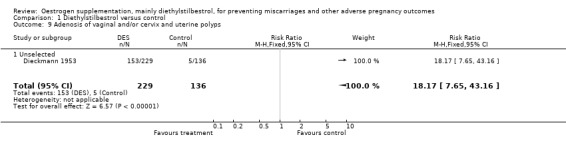

Adverse effects of interventions may be difficult to predict. Biological inferences in clinical practice without properly designed clinical trials may lead to more harm than good. All interventions need objective evidence of effectiveness and possible placebo effect should not be ignored. The MetaView in this presentation showed that the outcomes for babies born weighing less than 2500 grams and the survival of mothers at follow up favours the control group as against the DES exposed. Equally, occurrence of adenosis of the vagina and cervix and uterine polpys favours the control as against the DES exposed. Psychiatric disorders, primarily infertility and testicular abnormalities, significantly favour the control group. Had the principle of 'best evidence' been followed, the embarrassment of diethylstilboestrol as a medical intervention, and the effects on offspring who were exposed to it before birth, would have been avoided.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Diethylstilbestrol is no longer in use. The lessons learnt could be extrapolated to other interventions in medicine. Medical practice should always be guided by the best current evidence.

Implications for research.

There is no place for further research on the use of diethylstilbestrol in pregnancy. However, the need for researchers to invest in properly designed trials cannot be overemphasised.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

The Protocol for this Review was published as 'Antenatal oestrogens for preventing adverse foetal outcome'.

Acknowledgements

Justus Hofmeyr for mentorship. Paul Garner, Department for International Health, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, for support for Anthony Akinloye Bamigboye to visit the Effective Care Research Unit, East London (South Africa), to work on the review.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Diethylstilbestrol versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

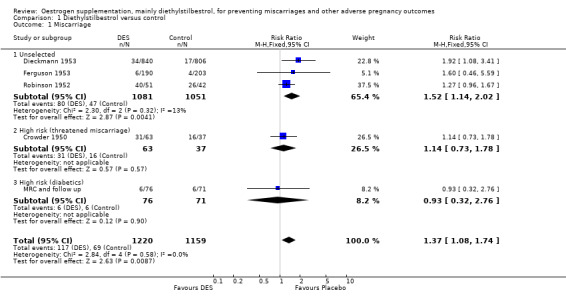

| 1 Miscarriage | 5 | 2379 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.37 [1.08, 1.74] |

| 1.1 Unselected | 3 | 2132 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [1.14, 2.02] |

| 1.2 High risk (threatened miscarriage) | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.73, 1.78] |

| 1.3 High risk (diabetics) | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.32, 2.76] |

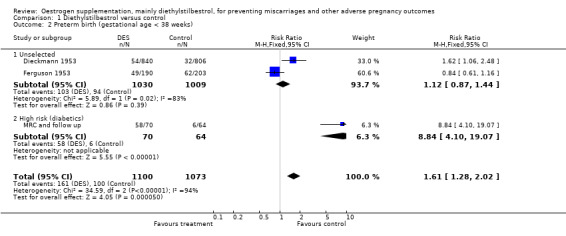

| 2 Preterm birth (gestational age < 38 weeks) | 3 | 2173 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.61 [1.28, 2.02] |

| 2.1 Unselected | 2 | 2039 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.87, 1.44] |

| 2.2 High risk (diabetics) | 1 | 134 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.84 [4.10, 19.07] |

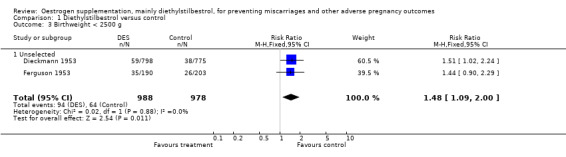

| 3 Birthweight < 2500 g | 2 | 1966 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [1.09, 2.00] |

| 3.1 Unselected | 2 | 1966 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [1.09, 2.00] |

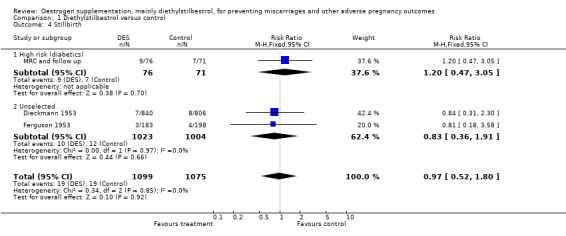

| 4 Stillbirth | 3 | 2174 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.52, 1.80] |

| 4.1 High risk (diabetics) | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.47, 3.05] |

| 4.2 Unselected | 2 | 2027 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.36, 1.91] |

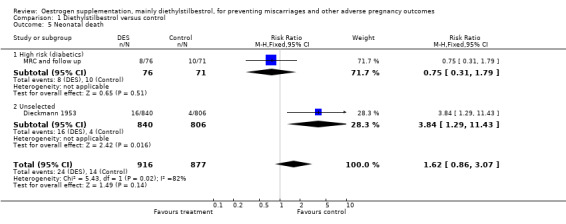

| 5 Neonatal death | 2 | 1793 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.62 [0.86, 3.07] |

| 5.1 High risk (diabetics) | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.31, 1.79] |

| 5.2 Unselected | 1 | 1646 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.84 [1.29, 11.43] |

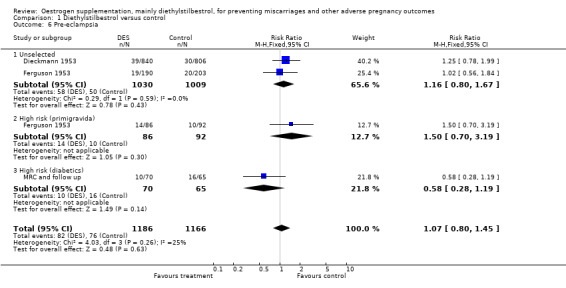

| 6 Pre‐eclampsia | 3 | 2352 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.80, 1.45] |

| 6.1 Unselected | 2 | 2039 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.80, 1.67] |

| 6.2 High risk (primigravida) | 1 | 178 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [0.70, 3.19] |

| 6.3 High risk (diabetics) | 1 | 135 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.28, 1.19] |

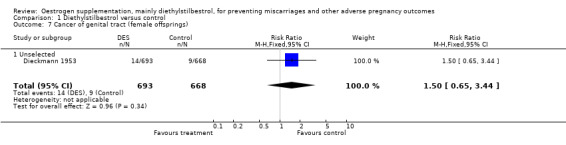

| 7 Cancer of genital tract (female offsprings) | 1 | 1361 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [0.65, 3.44] |

| 7.1 Unselected | 1 | 1361 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.50 [0.65, 3.44] |

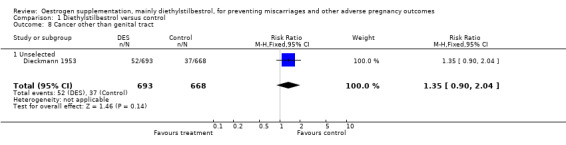

| 8 Cancer other than genital tract | 1 | 1361 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.90, 2.04] |

| 8.1 Unselected | 1 | 1361 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.90, 2.04] |

| 9 Adenosis of vaginal and/or cervix and uterine polyps | 1 | 365 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 18.17 [7.65, 43.16] |

| 9.1 Unselected | 1 | 365 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 18.17 [7.65, 43.16] |

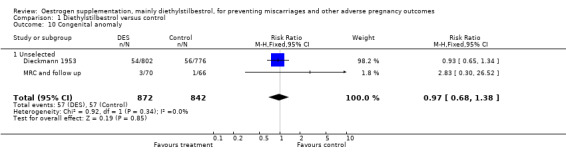

| 10 Congenital anomaly | 2 | 1714 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.68, 1.38] |

| 10.1 Unselected | 2 | 1714 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.68, 1.38] |

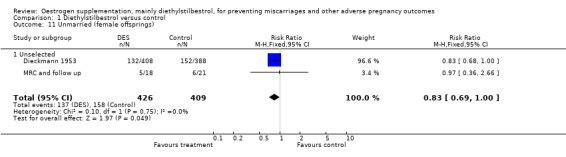

| 11 Unmarried (female offsprings) | 2 | 835 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.69, 1.00] |

| 11.1 Unselected | 2 | 835 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.69, 1.00] |

| 12 Psychiatric disorders (female offsprings) | 1 | 266 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.16 [1.03, 4.50] |

| 12.1 Unselected | 1 | 266 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.16 [1.03, 4.50] |

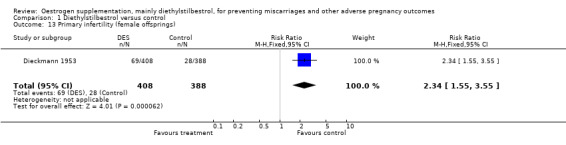

| 13 Primary infertility (female offsprings) | 1 | 796 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.34 [1.55, 3.55] |

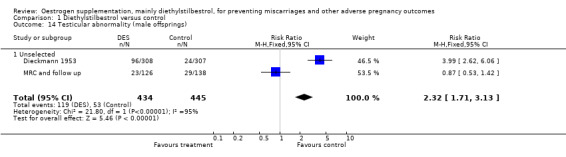

| 14 Testicular abnormality (male offsprings) | 2 | 879 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.32 [1.71, 3.13] |

| 14.1 Unselected | 2 | 879 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.32 [1.71, 3.13] |

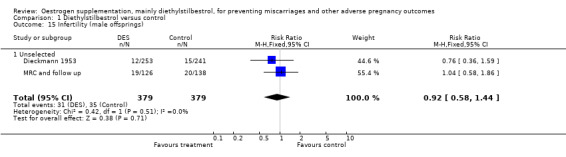

| 15 Infertility (male offsprings) | 2 | 758 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.58, 1.44] |

| 15.1 Unselected | 2 | 758 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.58, 1.44] |

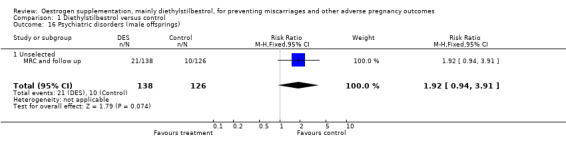

| 16 Psychiatric disorders (male offsprings) | 1 | 264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.92 [0.94, 3.91] |

| 16.1 Unselected | 1 | 264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.92 [0.94, 3.91] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 1 Miscarriage.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 2 Preterm birth (gestational age < 38 weeks).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 3 Birthweight < 2500 g.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 4 Stillbirth.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 5 Neonatal death.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 6 Pre‐eclampsia.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 7 Cancer of genital tract (female offsprings).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 8 Cancer other than genital tract.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 9 Adenosis of vaginal and/or cervix and uterine polyps.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 10 Congenital anomaly.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 11 Unmarried (female offsprings).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 12 Psychiatric disorders (female offsprings).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 13 Primary infertility (female offsprings).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 14 Testicular abnormality (male offsprings).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 15 Infertility (male offsprings).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Diethylstilbestrol versus control, Outcome 16 Psychiatric disorders (male offsprings).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bender 1988.

| Methods | Fifty eight women attending two separate antenatal clinics, 17 women had diethylstilbestrol in the first clinic and the second clinic of 41 women acted as control. | |

| Participants | Women with history of previous miscarriage(s) attending antenatal clinic. | |

| Interventions | No details of dosing. | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriage. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Crowder 1950.

| Methods | One hundred women were recruited, of which 37 had DES and 63 had placebo. | |

| Participants | Women admitted for threatened abortion and diabetic. | |

| Interventions | DES 25 mg every 30 minutes for 6 hours then 100 mg daily until asymptomatic for 24 hours, then 50 mg daily until 28 weeks of pregnancy. Both DES and control group had phenobarbitone and Demerol. | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriage. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Dieckmann 1953.

| Methods | Randomized double‐blind placebo controlled trial. 840 women were allocated to receive DES and 806 had placebos. | |

| Participants | All women attending prenatal clinic from 6 weeks. | |

| Interventions | 5 mg of DES administered from 7‐8 weeks in graduated fashion up to 150 mg at 34‐35 weeks. (Smith) | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriage in mothers (Dieckmann 1953; Brackbill 1978), prematurity (Dieckmann 1953), birthweight (Dieckmann 1953), pre‐eclampsia (Dieckmann 1953), congenital anomaly, and postmaturity. Testicular (Gill 1979) and genital tract abnormalities, semen analysis, sex hormone levels; female offspring: oligomenorrhoea; pregnancy; vaginal and cervical ridges; vaginal adenosis; vaginal and cervical dysplasia; cancer of genital tract and cancer other than genital tract; unmarried daughters (Bibbo 1978). Psychiatry disorders (Vessey 1983). 25‐year follow up of mothers: cancer; breast cancer; death; congenital anomalies (Bibbo 1978). Herbst 1980: pregnancy and contraception experience and pregnancy outcome in daughters. Herbst 1981: infertility (Senekjian 1981) pregnancy and gynaecological findings including tumors in daughters of exposed versus unexposed. Senekjian 1988: infertility among daughters, cervicovaginal abnormalities, hysterosalpingogram anomalies. Fertility in exposed men (Wilcox 1995). |

|

| Notes | The data in the follow‐up report by Hornsby 1994 has not been included because the outcome of interest (decrease in duration of menstruation) is not relevant to this review. The data from the report by Hornsby 1995 has not been included because the outcome of interest (time of onset of menopausal symptoms) is not relevant to this review. The data from the report by Schumacher 1981 has not been included because the principal outcome (semen analysis) is not relevant to this review. The reports by Wilcox 1992 and 1995 did not include any data relating to the outcomes of interest to this review. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Ferguson 1953.

| Methods | Alternate allocation, placebo controlled trial. 190 received DES and 203 had placebos. | |

| Participants | All women attending antenatal clinic. | |

| Interventions | DES 6.3 mg to 137.5 mg depending on gestational age vs placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriages, pre‐eclampsia, chronic hypertension with superimposed pre‐eclampsia, duration of pregnancy, weight gain and oedema, prematurity, stillbirth and neonatal deaths, fetal abnormality, threatened miscarriage, toxic reactions, placental effect. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

MRC and follow up.

| Methods | Randomised, placebo controlled trial. 76 women received DES and 71 received placebos. | |

| Participants | High risk diabetic women in pregnancy. | |

| Interventions | Incremental doses of 50 mg‐200 mg DES daily from about 16 weeks to term. Ethisterone, 25 mg/day from 16 weeks, incrementally to 250 mg/day at 32 weeks to term. Ethisterone was given incrementally. Graduated dosing with stilboestrol from 50 mg at 19 weeks or less to 200 mg at 32 weeks or more. Ethisterone from 25 mg/day at 19 weeks or less to 250 mg at 32 weeks or more. |

|

| Outcomes | Miscarriage (MRC 1955), stillbirth, birthweight. Congenital anomalies; unmarried daughters. Beral 1981: Genital tract abnormalities in sons, unmarried sons, psychiatric disorders and survival of exposed mothers (Vessey 1983). | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Robinson 1952.

| Methods | Alternate allocation, placebo controlled trial. 51 women had DES and 42 placebos | |

| Participants | Women admitted for threatened abortion. | |

| Interventions | DES 5 mg to 125 mg depending on gestational age vs placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Viable infants delivered. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Swyer 1954.

| Methods | Double‐blind placebo controlled trial. 227 received DES and 233 had placebo. | |

| Participants | All antenatal primigravida. | |

| Interventions | Smith regimen. | |

| Outcomes | Pre‐eclampsia, prematurity, labour duration and side effects of medication. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

The studies used in computing the outcome data appear in brackets after the outcome. This is the most recent data for each trial with the greatest numbers. DES: diethylstilboestrol vs: versus

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Baird 1996 | No outcomes that were relevant to the review were assessed. |

| Berle 1977 | A combination of estradiol and hydroxyprogesterone was used as the intervention. The protocol aims at assessing estrogens alone, hence the exclusion of this prospective trial. |

| Berle 1980 | Gestagens (progesterone) was used in the intervention and not an estrogen hence the exclusion. |

| Kaufman 2000 | This study concluded that pregnancy outcomes like spontaneous miscarriages, preterm births and ectopic pregnancies were more common in the DES exposed offsprings than unexposed. The study was excluded as it was not part of the original protocol, and included both randomised and non‐randomised cohorts. |

| Smith 1949 | Alternate allocations 'so far as was possible' without the use of placebo. Alternate allocations should yield fairly equal numbers in each group. However, 387 were in the DES group and 555 in the control group. This suggests bias in group allocations. |

DES = diethylstilbestrol

Contributions of authors

Jonathan Morris prepared the first draft of the protocol, extracted data and commented on drafts of the review. Anthony Bamigboye revised the protocol, extracted data, carried out the analysis and interpretation, and wrote the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

International Health Division, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (AAB), UK.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bender 1988 {unpublished data only}

- Bender S. The effect of diethylstilboestrol on recurrent miscarriage. Personal communication February 1988.

Crowder 1950 {published data only}

- Crowder RE, Bills ES, Broadbent JS. The management of threatened abortion. A study of 100 cases. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1950 Oct;60(4):896‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dieckmann 1953 {published data only}

- Bibbo M, Al‐Naqeeb M, Baccarini I, Gill W, Newton M, Sleeper KM, et al. Follow‐up study of male and female offspring of DES‐treated mothers. A preliminary report. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1975;15(1):29‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbo M, Gill W, Azizi F, Blough R, Fang VS, Rosenfield RL, et al. Follow‐up study of male and female offspring of DES‐exposed mothers. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1977;49(1):1‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbo M, Haemszel WM, Wied GL, Hubby M, Herbst AL. A twenty year follow‐up study of women exposed to diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine 1978;298(14):763‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackbill Y, Berendes H. Dangers of diethylstilbestrol: review of a 1953 paper. Lancet 1978;2:520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann WJ, Davis ME, Rynkiewcz SM, Pottinger RE. Does the administration of diethylstilbestrol during pregnancy have therapeutic value?. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1953;66(5):1062‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill WB, Schumacher GFB, Bibbo M. Pathological semen and anatomical abnormalities of the genital tract in human male subjects exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. Journal of Urology 1977;117:477‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill WB, Schumacher GFB, Bibbo M. Structural and functional abnormalities in the sex organs of male offspring of mothers treated with diethylstilbestrol. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1976;16(4):147‐53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill WB, Schumacher GFB, Bibbo M, Struas FH, Schoenbe HW. Association of diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero with cryptorchidism, testicular hypoplasia and semen abnormalities. Journal of Urology 1979;122:36‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst AL, Hubby MM, Azizi F, Makii MM. Reproductive and gynecologic surgical experience in diethylstilbestrol‐exposed daughters. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1981;141:1019‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst AL, Hubby MM, Blough RR, Azizi F. A comparison of pregnancy experience in DES‐exposed and DES‐unexposed daughters. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1980;24(2):62‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby PP, Wilcox AJ, Herbst AL. Onset of menopause in women exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1995;172(1):92‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby PP, Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Herbst AL. Effects on the menstrual cycle of in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994;170:709‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meara J, Fairweather DV. A randomized double‐blind controlled trial of the value of diethylstibestrol therapy in pregnancy: 35‐year follow‐up of mothers and their offspring. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1989;96(5):620‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penny R. The effect of DES on male offspring. Western Journal of Medicine 1982;136:329‐30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher GFB, Gill WB, Hubby MM, Blough RR. Semen analysis in males exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol or placebo. IRCS Medical Science 1981;9:100‐1. [Google Scholar]

- Senekjian EK, Potkul RK, Frey K, Herbst AL. Infertility among daughters either exposed or not exposed to diethylstilbestrol. Amercan Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1988;158(3):493‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR, Hornsby PP, Herbst AL. Fertility in men exposed prenatally to diethylstilbestrol. New England Journal of Medicine 1995;332(21):1411‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Maxey J, Herbst AL. Prenatal diethylstilbestrol exposure and performance on college entrance examinations. Hormones and Behavior 1992;26:433‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Umbach DM, Hornsby PP, Herbst AL. Age at menarche among diethylstilbestrol grand daughters. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1995;173:835‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ferguson 1953 {published data only}

- Ferguson JH. Effect of stilbestrol on pregnancy compared to the effect of a placebo. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1953;65(3):592‐601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

MRC and follow up {published data only}

- Beral V, Colwell L. Randomised trial of high doses of stilboestrol and ethisterone in pregnancy: long‐term follow‐up of mothers. BMJ 1980;281:1098‐101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beral V, Colwell L. Randomised trial of high doses of stilboestrol and ethisterone therapy in pregnancy: long‐term follow‐up. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 1981;35:155‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Research Council. The use of hormones in the management of pregnancy in diabetics. Lancet 1955;2:833‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey MP, Fairweather DVI, Norman‐Smith B, Buckley J. A randomized double‐blind controlled trial of the value of stilboestrol therapy in pregnancy: long term follow‐up of mothers and their offspring. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1983;90:1007‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Robinson 1952 {published data only}

- Robinson D, Shettles LB. The use of diethylstilboestrol in threatened abortion. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1952;63(6):1330‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Swyer 1954 {published data only}

- Swyer GIM, Law RG. An evaluation of the prophylactic ante‐natal use of stilboestrol. Preliminary report. Proceedings of the society for endocrinology. Journal of Endocrinology 1954;10:36‐7. [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Baird 1996 {published data only}

- Baird DD, Wilcox AJ, Herbst AL. Self‐reported allergy, infection and autoimmune diseases among men and women exposed in utero to diethylstilboestrol. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1996;49(2):263‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berle 1977 {published data only}

- Berle P, Behnke K. The treatment of threatened abortion [Uber Behandlungserfolge der drohenden Fehlgeburt]. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde 1977;37:139‐42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berle 1980 {published data only}

- Berle P, Budenz M, Michaelis J. Is hormonal therapy still justified in imminent abortions? [Besitzt die Hormontherapie bei der Behandlung des Abortus immens eine Berechtigung?]. Zeitschrift fur Geburtshilfe und Perinatologie 1980;184:353‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kaufman 2000 {published data only}

- Kaufman RH, Adam E, Hatch EE, Noller K, Herbst AL, Palmer JR, et al. Continued follow up of pregnancy outcomes in diethylstilbestrol‐exposed offspring. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;96(4):483‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 1949 {published data only}

- Smith OW, S Smith G. The influence of diethylstilbestrol on the progress and outcome of pregnancy as based on a comparison of treated with untreated primigravidas. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1949;58:994‐1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bibbo 1975

- Bibbo M, Al‐Naqeeb M, Baccarini I, Gill W, Newton M, Sleeper KM, et al. Follow‐up study of male and female offspring of DES‐treated mothers. A preliminary report. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1975;15:29‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bibbo 1977

- Bibbo M, Gill WB, Azizi P, Blough R, Fang VS, Rosenfield RL, et al. Follow‐up study of male and female offspring of DES‐exposed mothers. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1977;49:1‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Everett 1997

- Everett C. Incidence and outcome of bleeding before the 20th week of pregnancy: prospective study from general practice. BMJ 1997;315:32‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

FDA 1971

- FDA Drug Bulletin. Diethylstilboestrol contraindicated in pregnancy. US Dept of Health, Education and Welfare 1971.

Herbst 1971

- Herbst AL, Ulfelder H, Poskanzer DC. Association of maternal stilboestrol therapy with tumour appearance in young women. New England Journal of Medicine 1971;284:878‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Herbst 1975

- Herbst AL, Poskanzer DC, Robboy SJ, Friedlander L, Scully RE, et al. Prenatal exposure to stilboestrol. A prospective comparison of exposed female offspring with unexposed controls. New England Journal of Medicine 1975;292:334‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pencharz 1940

- Pencharz RI. Effect of estrogens and androgens alone and in combination with chorionic gonadotrophin on ovary of hypophysectomized rat. Science 1940;91:554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 1941

- Smith OW, Smith GV, Schiller S. Estrogen and progestin metabolism in pregnancy: spontaneous and induced labor. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology 1941;1:461‐9. [Google Scholar]

Smith 1944

- Smith OW, Smith GVS. Pituitary stimulating property of stilbestrol as compared with that of estrone. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 1944;57:198‐200. [Google Scholar]

Smith 1948

- Smith OW. Diethylstilboestrol in the prevention and treatment of complications of pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1948;56:821‐34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Beral 1995

- Beral V, Chalmers I. Diethylstilboestrol (DES) in pregnancy. [ revised 21 April 1994] In: Enkin MW, Keirse MJNC, Renfrew MJ, Neilson JP, Crowther C (eds.) Pregnancy and Childbirth Module. In: The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Database [database on disk and CDROM]. The Cochrane Collaboration; Issue 2, Oxford: Update Software; 1995.