Abstract

Introduction

Switzerland experienced two waves of COVID-19 in 2020, but with a different ICU admission and treatment management strategy. The timing of ICU admission and intubation remains a matter of debate in severe patients. The aim of our study was to describe the characteristics of ICU patients between two subsequent waves of COVID-19 who underwent a different management strategy and to assess whether the timing of intubation was associated with differences in mortality.

Patients and methods

We conducted a prospective observational study of all adult patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 who required intubation between the 9th of March 2020 and the 9th of January 2021 in the intensive care unit (ICU) at Geneva University Hospitals, Switzerland.

Results

Two hundred twenty-three patients were intubated during the study period; 124 during the first wave, and 99 during the second wave. Patients admitted to the ICU during the second wave had a higher SAPS II severity score (52.5 vs. 60; p = 0.01). The time from hospital admission to intubation was significantly longer during the second compared to the first wave (4 days [IQR, 1-7] vs. 2 days [IQR, 0-4]; p < 0.01). All-cause ICU mortality was significantly higher during the second wave (42% vs. 23%; p < 0.01). In a multivariate analysis, the delay between hospital admission and intubation was significantly associated with ICU mortality (OR 3.25 [95% CI, 1.38-7.67]; p < 0.05).

Conclusions

In this observational study, delayed intubation was associated with increased mortality in patients with severe COVID-19. Further randomised controlled trials are needed.

Keywords: Acute respiratory distress syndrome, COVID-19, intensive care unit, mortality, timing intubation, delayed intubation

1. Introduction

A profound structural reorganisation of hospitals and intensive care units (ICUs) was necessary to accommodate a rapid and large surge of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients worldwide [1], [2]. In Geneva, Switzerland, we had to face two subsequent waves in spring and autumn 2020, with a large number of patients admitted to the hospital and the ICU [3], [4]. The main manifestation of severe COVID-19 is acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure requiring respiratory support. In this massive influx of patients, the optimal timing of intubation remained challenging for many reasons. First, patients frequently presented hypoxaemia without tachypnoea or another indication of respiratory distress [5]. Hence, the usual criteria for intubation were difficult to apply [6]. Second, the potential clinical benefit of a combined therapy using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), high-flow oxygen using nasal cannula (HFNC), and awake prone positioning in severe COVID-19 handled in intermediate care units outside the ICU prevented the ICU from becoming rapidly overwhelmed by the mass of incoming patients [7], [8], [9]. However, delaying intubation may have been associated with a poorer prognosis, partly because of a prolonged use of non-invasive ventilation on inflamed lungs, promoting self-inflicted lung injury [10]. The appropriate management approach to respiratory failure in COVID-19 has not yet been established and few studies have investigated the effect of the timing of intubation and whether it affects patient outcomes.

The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics of patients between two subsequent waves of COVID-19 in the ICU of a Swiss University Hospital and to assess whether the timing of intubation was associated with differences in mortality.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This prospective observational study was conducted at the ICU of Geneva University Hospitals (Switzerland) between the 9th of March 2020 and the 9th of January 2021. All adult patients admitted to the ICU with acute respiratory failure due to SARS-CoV-2 infection requiring intubation were included. SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined by a positive reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction test in a nasopharyngeal swab and/or in a bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. The first wave was defined by all patients admitted to the ICU from the 9th of March to the 15th of May 2020, and the second wave was defined by all patients admitted to the ICU from the 16th of May 2020 to the 9th of January 2021. The primary outcome was ICU mortality. The ethic committee from the canton of Geneva approved the study (BASEC #: 2020-00917) and informed consent was obtained from the patient or next-of-kin. This manuscript follows the STROBE statement for reporting of cohort studies.

2.2. ICU admission and therapies

In early March 2020, our hospital reorganised all the healthcare units in the hospital to ensure the management of all patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infections. The regular ICU bed capacity is 32. However, during the first wave, our ICU preparedness and reorganisation allowed us to have a maximum of 110 ICU available beds with our usual staff/patient ratio. During the second wave, we adapted our ICU bed capacity daily to ensure admission of all severe patients; this capacity reached 45 available beds. A complete description of care strategies and protocols developed at our centre during the first wave of spring 2020 has already been published [4]. A standardised protocol was used as a triage strategy for referring patients to the ICU during both waves. If patients did not meet ICU admission criteria, they were admitted to the intermediate care unit where they received non-invasive respiratory support combining alternatively CPAP (Hamilton ® T1 ventilators) or HFNC (Optiflow® system). Bi-level positive airway pressure ventilation (BiPAP) was never used during patient intermediate care unit stay. Awake prone positioning was left to the discretion of the physician-in-charge. HFNC was initiated with high-flow settings of 50-60 L/min and FiO2 was titrated to maintain SaO2 between 90% and 94%. CPAP was initiated with FiO2 to maintain SaO2 between 90% and 94% and a level of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) between 5-10 cmH20. During the first wave, patients arriving from the emergency department or hospitalised in COVID-19 units were admitted directly to the ICU when they had a SaO2 < 90%, despite FiO2 > 50%, together with signs of respiratory failure. Invasive airway support was immediately performed after admission to the ICU.

However, in autumn 2020, no clear data had shown a real benefit of an early intubation in severe COVID-19 patients. Given the demanding therapies associated with mechanical ventilation in the ICU, such as sedation and neuromuscular blockers, and the fear of experiencing the same or higher surge of intubated patients during the second wave, ICU admission criteria were thus adapted promoting non-invasive strategies in intermediate care units. During the second wave, patients were therefore admitted to the ICU when the FiO2 was ≥ 80% using HFNC and/or CPAP and with signs of respiratory distress. Invasive airway support was only performed in the ICU and left to the discretion of the physician in charge of the patient.

At the beginning of the second wave, protocols and treatment strategies were modified according to the scientific evidence available at that time (autumn 2020). Almost all patients admitted during the first wave received hydroxychloroquine [11], [12], whereas all patients admitted in the second wave received dexamethasone for 10 days [13]. Apart from the ICU admission criteria and COVID-19-specific medical therapies, all other ICU management protocols, including sedation, thromboprophylaxis, nutrition, or other organ support therapies, did not differ between the two study periods [4]. During both waves, the nurse/patient ratio varied from 1:1 to 1:2 according to the intensive care qualifications of nursing staff. Therapeutic limitations were made based on the evolution of the patient and the families’ wishes. End-of-life criteria and management did not change between the two study periods.

2.3. Data collection

Clinical and biological data were recorded prospectively. The Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were calculated at the time of ICU admission. All biological data were collected during the first 24 h of ICU admission. Static compliance of the respiratory system was calculated by dividing the tidal volume by the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP. Hydrocortisone (200 mg per day) was administered in patients presenting with septic shock requiring > 0.1 µg/kg/min norepinephrine and with lactate levels > 2 mmol/L [14], [15]. High-dose glucocorticoids were administered to patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) not resolving after one week (methylprednisolone loading dose of 2 mg/kg, followed by 1 mg/kg for 7 days) [16]. ICU mortality and ICU and hospital length of stay were recorded, as well as the duration of mechanical ventilation, mechanical ventilation free-days, the need for non-ventilatory ARDS therapies and renal replacement therapy, the incidence density of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), the incidence of septic shock, and thromboembolic events. Septic shock was defined as a clinical construct of sepsis with persisting hypotension requiring more than 0.1 µg/kg/min of norepinephrine to maintain MAP ≥ 65 mm Hg and a serum lactate level > 2 mmol/L, despite adequate volume resuscitation [15]. A thromboembolic event was defined by deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism. The diagnosis of aspergillosis was made according to Verweij et al. [17].

2.4. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables are expressed as the number of patients (percentage). Proportions are presented with the 95% confidence interval (CI). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare non-parametric continuous variables between both groups. Chi-2 or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, as appropriate. All reported p values are two-sided and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. To investigate an association between mortality and delay of intubation, a logistic regression was performed with an adjustment to the SAPS2 severity score and hospitalisation period (wave one or two). Results are expressed as odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs. Analyses were performed using Stata® IC 16.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA) and R Statistical Software (v3.6.2; R Core Team 2021).

3. Results

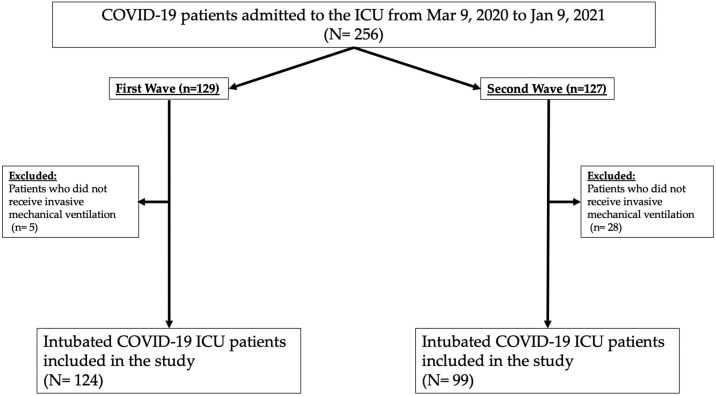

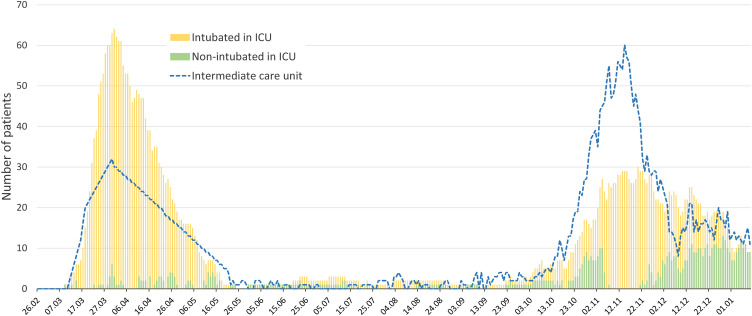

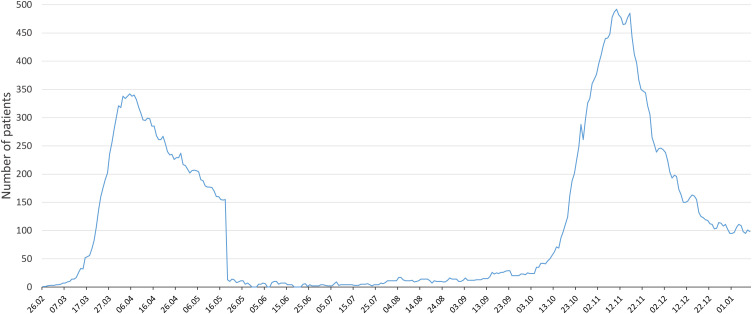

During the study period, 256 patients were admitted to the ICU. Finally, 223 patients were intubated and included in the study (Fig. 1 ). The distribution of severe COVID-19 patients during the two waves in the ICU and intermediate care units is presented in Fig. 2 . The total number of COVID-19 patients admitted to our hospital during the two waves is presented in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart.

ICU: intensive care unit; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of severe COVID-19 patients in the ICU and intermediate care units during the two waves.

ICU: intensive care unit; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

Fig. 3.

Total number of COVID-19 patients hospitalised during the two waves.

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

3.1. ICU admission characteristics

Age, sex ratio and body mass index were similar between the two waves of COVID-19 patients (Table 1 ). Comorbidities were also similar between the two waves, with the exception of a higher prevalence of diabetes among patients in the second wave (40.4% vs. 26.6%; p = 0.02). Patients were admitted to the ICU significantly later after hospital admission during the second wave compared to the first wave (median 4 days [IQR, 1-7] vs. 2 days [IQR, 0-4]; p < 0.01, respectively). In addition, patients admitted to the ICU during the second wave were more severely ill than those admitted during the first wave (median APACHE II score, 26 [IQR, 18-30] vs. 22 [IQR, 14-29]; p < 0.01; median SAPS II score, 60 [IQR, 43-72], vs. 52.5 [IQR, 40.5-65]; p < 0.01, respectively). Some laboratory variables significantly differed in patients admitted during the first vs. the second wave: white blood cell count (11.5 × 109/L [IQR, 8.5-15] vs. 7.6 [IQR, 5.8-10.4]; p < 0.01), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (17 [IQR, 10-31.2] vs. 11.3 [IQR, 6.6-19.2]; p < 0.01), platelet count (199 × 109/L [IQR, 158-250] vs. 260 [IQR, 185-342]; p < 0.01), and arterial lactate (1.5 mmol/L [IQR, 1.2-2] vs. 0.9 [IQR, 0.7-1.1]; p < 0.01, respectively) (Table 1). Patients admitted to the ICU during the two waves had a similar median duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (13 days; Table 2 ). Oxygenation parameters were more impaired in patients admitted to the ICU during the second wave at the time of intubation (median FiO2 70% [IQR, 60-80] vs. 60% [IQR, 45-75]; p < 0.01, median PaO2/FiO2 ratio 97 mmHg [IQR, 79.5-131.2] vs. 140 mmHg [IQR, 102-178.5]; p < 0.01, respectively). The median static respiratory compliance was significantly lower in patients intubated during the second wave (32.8 [IQR, 26-40] vs. 39 [IQR, 31-50]; p < 0.01, respectively). During the second wave, intubated patients received less neuromuscular blockade agents and for a shorter period of time (65.7% vs. 93%; p < 0.01 with a median of 3 days [IQR, 3-5] vs. 4 days [IQR, 3-7.5]; p < 0.01, respectively).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of intubated patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

| Patients admitted during the 1st wave (n = 124) | Patients admitted during the 2nd wave (n = 99) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), years | 64.5 (57-73) | 68 (59-74) | 0.1a |

| < 40, n (%) | 7 (5.6) | 1 (1) | |

| 40-49, n (%) | 5 (4) | 5 (5) | |

| 50-59, n (%) | 34 (27.4) | 22 (22.2) | |

| 60-69, n (%) | 37 (29.8) | 30 (30.3) | |

| 70-79, n (%) | 32 (25.8) | 31 (31.3) | |

| ≥ 80, n (%) | 9 (7.3) | 10 (10.1) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.74b | ||

| Female | 29 (23.4) | 25 (25.3) | |

| Male | 95 (76.6) | 74 (74.7) | |

| Body mass index, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 27.8 (25.5-31.8) | 28 (24.6-32.8) | 0.99a |

| < 25, n (%) | 23 (18.5) | 27 (27.3) | |

| 25-29, n (%) | 58 (46.8) | 35 (35.4) | |

| 30-34, n (%) | 31 (25) | 23 (23.2) | |

| 35-39, n (%) | 10 (8.1) | 9 (9.1) | |

| ≥ 40, n (%) | 2 (1.6) | 5 (5) | |

| Duration of symptoms before hospital admission, median (IQR), days | 7 (4-9) | 6 (3-9) | 0.55a |

| Time from hospital to ICU admission, median (IQR), days | 2 (0-3) | 3 (1-7) | < 0.01a |

| Duration of symptoms before intubation, median (IQR), days | 9 (7-11) | 10 (8-14) | < 0.01a |

| Time from hospital admission to intubation, median (IQR), days | 2 (0-4) | 4 (1-7) | < 0.01a |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| None | 27 (21.8) | 11 (11.1) | 0.b |

| Hypertension | 60 (48.4) | 47 (47.47) | 0.89b |

| Diabetes | 33 (26.6) | 40 (40.4) | 0.02b |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 34 (27.4) | 33 (33.3) | 0.33b |

| Cardiomyopathy and heart failure | 29 (23.4) | 13 (13.1) | 0.05b |

| Smoker | 19 (15.3) | 21 (21.4) | 0.23b |

| COPD | 9 (7.3) | 7 (7.1) | 0.94b |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7 (5.7) | 10 (10.1) | 0.21b |

| Malignancyd | 10 (8.1) | 13 (13.1) | 0.21b |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (8.1) | 9 (9.1) | 0.78b |

| Severity scores at the admission, median (IQR) | |||

| APACHE II score | 22 (14-29) | 26 (18-30) | 0.01a |

| SAPS II score | 52.5 (40.5-65) | 60 (43-72) | 0.01a |

| SOFA score | 6 (4-7) | 6 (4-8) | 0.13a |

| Laboratory data, median (IQR) | |||

| White blood cell count, x109/L | 7.6 (5.8-10.4) | 11.5 (8.5-15) | < 0.01a |

| Neutrophil count, x109/L | 6.46 (4.8-9.5) | 10.1 (7.3-13.3) | < 0.01a |

| Lymphocyte count, x109/L | 0.54 (0.37-0.83) | 0.54 (0.31-0.79) | 0.4a |

| Lymphocyte count < 1 × 109/L, n (%) | 92 (74.2) | 84 (84.9) | 0.05b |

| Neutrophils/lymphocytes ratio (95% CI) | 11.3 (6.6-19.2) | 17 (10-31.2) | < 0.01a |

| Platelet count, x109/L | 199 (158-250) | 260 (185-342) | < 0.01a |

| D-dimer, µg/L | 1553 (965-2476) | 1528.5 (909-3202) | 0.5a |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 81 (66.5-105) | 85 (64-112) | 0.47a |

| Creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL, n (%) | 10 (8) | 15 (15.2) | 0.09c |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 54 (42-79) | 46 (28-72) | 0.03a |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 34.5 (27-54) | 46 (28-67) | 0.09a |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 9 (6-14) | 9 (6-13) | 0.32a |

| Hypersensitive troponin T (hsTnT), ng/L | 18 (11-41.5) | 21 (10-49) | 0.75a |

| hsTnT ≥ 14 ng/Le, n (%) | 81 (65.3) | 69 (69.7) | 0.48a |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 0.41 (0.22-1.17) | 0.46 (0.2-1.71) | 0.61a |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 158 (101.5-207.8) | 134.7 (79.7-207) | 0.27a |

| Arterial lactate, mmol/L | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 1.5 (1.2-2) | < 0.01a |

APACHE, Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Chi-2 test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Malignancy includes active solid or haematologic neoplasia and solid or haematologic neoplasia in remission.

Concentration of hsTnT defining myocardial injury (99th percentile of the upper reference limit).

Table 2.

Treatments, complications and outcome of intubated patients admitted to the intensive care unit.

| Patients admitted during the 1st wave (n = 124) | Patients admitted during the 2nd wave (n = 99) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory support | |||

| Duration of invasive mechanical ventilation, median (IQR), days | 13 (9-17) | 13 (7-22) | 0.8a |

| Free days of mechanical ventilation until Day 28, median (IQR), days | 15 (11-19) | 16 (8-22) | 0.37a |

| Oxygenation and ventilatory parameters at admission, median (IQR) | |||

| FiO2, % | 60 (45-75) | 70 (60-80) | < 0.01a |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio, mmHg | 140.2 (102-178.5) | 96.7 (79.5-131.2) | < 0.01a |

| Respiratory rate at admission, breaths/min | 32 (28-36) | 30 (25-35) | < 0.04a |

| PEEP, cmH2O | 11 (10-12) | 12 (10-12) | 0.74a |

| Static compliance, ml/cmH2O | 39 (31-50) | 32.8 (26-40) | < 0.0 1a |

| Non-ventilatory ARDS therapies | |||

| Neuromuscular blockade, n (%) | 116 (93.5) | 65 (65.7) | < 0.01b |

| Days under neuromuscular blockade, median (IQR) | 4 (3-7.5) | 3 (2-5) | < 0.01a |

| Prone positioning, n (%) | 95 (76.6) | 73 (73.7) | 0.6b |

| Prone sessions per patient, median (IQR) | 2 (1-4) | 2(1-4) | 0.8a |

| Inhaled nitric oxide, n (%) | 30 (24.2) | 25 (25.3) | 0.9b |

| ECMO, n (%) | 11 (8.9) | 5 (5.1) | 0.27c |

| COVID-19 specific medical treatments, n (%) | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine | 115 (89.1) | 0 | 0.b |

| Azithromycin | 112 (86.9) | 0 | 0.b |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 52 (40.3) | 0 | 0.b |

| Remdesivir | 9 (7.3) | 11 (11.1) | 0.32b |

| Anakinra | 16 (12.4) | 0 | 0. |

| Dexamethasone | 0 | 94 (94.9) | |

| Other medical treatments | |||

| Antibiotics, n (%) | 123 (99.2) | 97 (97.8) | 0.43b |

| Duration of antibiotics, median (IQR), days | 9(6-12) | 8 (5-13.5) | 0.77a |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 41 (33.1) | 43 (43.4) | 0.11b |

| Indications to glucocorticoids | |||

| Septic shock | 13 (33.3) | 3 (7) | < 0.01c |

| ARDS | 21 (31.7) | 38 (38.4) | < 0.01b |

| Othersd | 5 (12.2) | 2 (4.6) | 0.18c |

| Norepinephrine, n (%) | 114 (91.9) | 97 (98) | 0.04a |

| Norepinephrine > 0.1 µg/kg/min | 65 (52.4) | 52 (53.6) | 0.8b |

| Insuline dose per day, median (IQR), UI | 41 (15.6-78.3) | 50 (30.2-78.1) | 0.5a |

| Duration of Insulinotherapy, median (IQR), days | 8 (5-16) | 7 (3-13) | 0.46a |

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Septic shock | 6 (4.8) | 12 (12.1) | 0.04b |

| Thromboembolic evente | 19 (14.8) | 12 (12.1) | 0.06b |

| Acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy | 15 (12.1) | 3 (3) | 0.01b |

| Ventilatory-associated pneumonia, n (%) | 4 (3.2) | 10 (10.1) | 0.05c |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia, density incidence, cases/1,000 days of ventilation | 2.9 | 7.5 | f |

| Aspergillosis | 7 (5.6) | 7 (7.1) | 0.66b |

| Pressure sores, n (%) | 36 (29) | 12 (12.1) | < 0.01b |

| ICU mortality, n (%) | 23 (18.6) | 42 (42.4) | < 0.01b |

| Length of hospital stay, median (IQR), days | 28 (19-40) | 26.5 (16-38) | 0.2a |

| Length of ICU stay, median (IQR), days | 16 (11-21.5) | 14 (8-24) | 0.5a |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19, coronavirus disease-19; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2, inspired fraction of oxygen; ICU, intensive care unit; PaO2; arterial partial pressure of oxygen; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

Mann-Whitney U test.

Chi-2 test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Other includes vasculitis, COPD/asthma, or corticoids as usual treatment.

Thromboembolic event includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Due to the small number of events, no comparative analysis was performed.

In contrast to the first wave, no patients from the second wave received hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, anakinra, or lopinavir/ritonavir. On the other hand, 94.9% of patients received dexamethasone during the second wave. Antibiotics were largely prescribed during both waves with median treatment duration of 8 days. Apart from dexamethasone administered to all hospitalised patients requiring oxygen, a large proportion of intubated patients received glucocorticoids during their ICU stay for various indications: hydrocortisone in patients presenting septic shock during the first wave (33.3% vs. 7% during the second wave, p < 0.01, respectively), and others for unresolving ARDS during the second wave (38% vs. 21% during the first wave, p < 0.01, respectively).

Only 3% of patients required renal replacement therapy during the second wave, compared to 12.1% during the first wave (p < 0.01; Table 2). Patients during the second wave tended to have more VAP (7.5 vs. 2.9 VAP/1000 ventilation days, respectively; Table 2). Fourteen (6.3%) of all intubated patients during the two waves fulfilled criteria for aspergillosis. No significant differences were observed between the two waves. Finally, ICU mortality was significantly higher in the second wave compared to the first wave (42% vs. 23%; p < 0.01, respectively).

In a multivariate analysis, the time from hospital admission to intubation was the main predictive risk factor associated with ICU mortality. The strength of the association was directly related to the time from hospital admission to intubation when performed after 7 days (OR 3.25 [95% CI 1.38-7.67]) (Table 3 ). In total, 50 patients were intubated after 7 days in the hospital stay.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis with the timing of intubation, SAPS II score and hospitalisation period.

| ICU mortality in intubated patients OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|

| Timing of intubation after hospital admission in days | |

| -Intubation between day 0 and day 3 | Ref. |

| -Intubation between day 3 and day 7 | 1.26 (0.57 - 2.80) |

| -Intubation after day 7 (including day 7) | 3.25 (1.38 - 7.67)* |

| SAPS II | 1.06 (1.03 - 1.08)* |

| Hospitalisation period | |

| -wave 1 | Ref. |

| -wave 2 | 2.14 (1.08 - 4.23)* |

ICU, intensive care unit; SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score; FiO2, inspired fraction of oxygen; PaO2; arterial partial pressure of oxygen; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

= p < 0.03.

4. Discussion

In this prospective, single-centre cohort study, patients admitted to the ICU and intubated during the second wave were more hypoxaemic, with a higher severity score at ICU admission and a higher mortality compared to those admitted during the first wave. During the second wave, a significant number of patients admitted to the hospital with severe respiratory failure were treated in dedicated intermediate care units with HFNO, CPAP, and awake prone positioning [18], [19]. A proportion of these patients did not finally need to be admitted to the ICU. In those who did need intubation, the duration between hospital admission and intubation was independently associated with ICU mortality, particularly when patients were intubated after 7 days. A higher mortality of ICU patients during the second wave can be explained by the fact that those who finally had to be admitted to the ICU were the most critically ill, i.e., patients who did not improve with – sometime prolonged – non-invasive ventilation and HFNO. Supporting elements for this more severe condition were that patients admitted to the ICU in the second wave had a significantly higher FiO2, a lower PaO2/FiO2 ratio, lower static pulmonary compliance at the time of intubation, and higher SAPS II and APACHE II scores. However, after performing a multivariate analysis including the SAPS II severity score (with PaO2/FiO2 ratio, age) and the time of ICU admission (wave), the duration between hospital admission and intubation remained associated with ICU mortality.

The association between the duration of non-invasive ventilatory support before intubation and mortality in our study may be explained by the selection of patients with more severe lung inflammation and failure who were ultimately admitted to the ICU. Interestingly, it has been shown that non-invasive ventilation may generate large tidal volumes in patients with ARDS and therefore induce volutrauma [20]. It can therefore be postulated that patients with prolonged respiratory failure kept extubated for a long period of time may have generated lung injury due to high tidal volumes, in addition to that induced by the viral pneumonia and alveolar inflammation [21], [22]. This is in accordance with the study by Hyman et al., showing that each additional day between hospital admission and intubation was associated with a higher in-hospital death rate [23]. In addition, another study reported that early intubation after a non-invasive procedure might reduce mortality in the ICU, as recently suggested [24]. In contrast, in a multicentre study, Hernandez-Romieu et al. did not find any association between timing of ICU admission and mortality [25].

These latter studies carry numerous limitations, mainly due to their retrospective design. Moreover, a recently published meta-analysis including previous studies did not show beneficial effect of an early intubation on mortality [26], but there was a high heterogeneity with differing or unknown patient severities. Hence, the timing of intubation and ICU management in severe COVID-19 pneumonia remains a matter of debate [27], [28], [29]. Although it seems reasonable that some of these patients may benefit from a strategy aimed at delaying intubation and invasive mechanical ventilation, it can also be argued that prolonged non-invasive ventilation may prevent some of these patients from receiving lung protection with low tidal volumes during invasive mechanical ventilation. Until now, it has not been possible to identify COVID-19 patients who may benefit from early vs. late intubation. The ROX index, defined as the ratio of oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry/FiO2 to the respiratory rate, has been proposed to detect patients who need intubation in ARDS [30] and a recent study has suggested it as a predictive tool to identify severe COVID-19 patients requiring early intubation [31].

Another interesting finding of our study was the significantly lower incidence of renal replacement therapy (RRT) during the second wave compared to the first wave (3% vs. 12%, respectively), despite higher severity scores in patients admitted during the second wave. Our results are consistent with the incidence of RRT in ICU COVID-19 patients [32]. Among the factors that may explain the difference in the incidence of acute kidney injury requiring RRT is the different panel of drugs used during the two waves. An explanation of the higher incidence of acute kidney injury requiring RRT during the first wave may reside in the fact that the several drugs presenting a potential nephrotoxicity were widely used, such as hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, lopinavir/ritonavir or remdesivir, whereas they were not given during the second wave. In addition, acute kidney injury may have been reduced during the second wave by the widespread use of dexamethasone. Indeed, glucocorticoids have been associated with renal protection by inducing a reduction of the renal and endothelial inflammatory process [33].

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a single centre-study, which limits the generalisability of the obtained results. Second, only patients who finally needed an intubation were included and followed. However, during the second wave, a proportion of patients may have avoided ICU admission in the delayed intubation strategy. Third, patients of the two waves were considerably different, with notably greater degree of severity at admission during the second wave, which could have led to a selection bias for the association between time to intubation and mortality. To minimise these biases, our multivariate analysis included an adjustment to the SAPS II severity score (including PaO2/FiO2 ratio) and time of ICU admission. Finally, this is an observational study, which only allows finding an association between intubation delay and mortality, but does not allow establishing a causal effect.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that delaying ICU admission and intubation could be potentially harmful and associated with increased mortality. Further randomised controlled trials are needed to provide key information about the optimal time of ICU admission and intubation.

Human and animal rights

The authors declare that the work described has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association revised in 2013 for experiments involving humans as well as in accordance with the EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments.

Consent for publication

All patients or the next-of-kin were informed that this conducted research might be published.

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Authors’ contributions

Drs. Le Terrier, Suh, Quintard, Bendjelid and J. Pugin imagined and designed the study. They had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Le Terrier, Suh, and Giudicelli-Bailly collected the data. Drs. Le Terrier, Suh, Wozniak and J. Pugin analysed the data. Drs. Le Terrier, Suh, Wozniak, Sangla, Legouis and J. Pugin drafted the paper. All authors interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval for the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

This study was performed at the Division of Intensive Care, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.

Availability of data and materials

After publication, the data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. A proposal with a detailed description of study objectives and statistical analysis plan will be needed for evaluation of the reasonability of requests. Additional materials might also be required during the process of evaluation. De-identified participant data will be provided after approval from the corresponding author and the Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics committee from the canton of Geneva, Switzerland approved the study (BASEC #: 2020-00917), and an informed consent was obtained from the patient or the next-of-kin, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the ICU staff for taking care of all those patients admitted to the ICU. We also thank Rosemary Sudan for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2022.101092.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Aziz S., Arabi Y.M., Alhazzani W., Evans L., Citerio G., Fischkoff K., et al. Managing ICU surge during the COVID-19 crisis: rapid guidelines. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(Jul (7)):1303–1325. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffin K.M., Karas M.G., Ivascu N.S., Lief L. Hospital preparedness for COVID-19: a practical guide from a critical care perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1337–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1037CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- 4.Primmaz S., Le Terrier C., Suh N., Ventura F., Boroli F., Bendjelid K., et al. Preparedness and reorganization of care for coronavirus disease 2019 Patients in a Swiss ICU: characteristics and outcomes of 129 Patients. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(8):e0173. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tobin M.J., Laghi F., Jubran A. Why COVID-19 silent hypoxemia is baffling to physicians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(3):356–360. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2157CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsolaki V, Zakynthinos GE. Timing of intubation in covid-19 ARDS: What "time" really matters? Crit Care. 2021;25(1):173. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03598-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppo A., Bellani G., Winterton D., Di Pierro M., Soria A., Faverio P., et al. Feasibility and physiological effects of prone positioning in non-intubated patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 (PRON-COVID): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(8):765–774. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30268-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calligaro G.L., Lalla U., Audley G., Gina P., Miller M.G., Mendelson M., et al. The utility of high-flow nasal oxygen for severe COVID-19 pneumonia in a resource-constrained setting: A multi-centre prospective observational study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franco C., Facciolongo N., Tonelli R., Dongilli R., Vianello A., Pisani L., et al. Feasibility and clinical impact of out-of-ICU noninvasive respiratory support in patients with COVID-19-related pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02130-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kangelaris K.N., Ware L.B., Wang C.Y., Janz D.R., Zhuo H., Matthay M.A., et al. Timing of intubation and clinical outcomes in adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(1):120–129. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gautret P., Lagier J.C., Parola P., Hoang V.T., Meddeb L., Mailhe M., et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Million M., Lagier J.C., Gautret P., Colson P., Fournier P.E., Amrane S., et al. Early treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: A retrospective analysis of 1061 cases in Marseille. France. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;35 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes A., Evans L.E., Alhazzani W., Levy M.M., Antonelli M., Ferrer R., et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(3):304–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., Shankar-Hari M., Annane D., Bauer M., et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meduri G.U., Bridges L., Siemieniuk R.A.C., Kocak M. An exploratory reanalysis of the randomized trial on efficacy of corticosteroids as rescue therapy for the late phase of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):884–891. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verweij P.E., Rijnders B.J.A., Brüggemann R.J.M., Azoulay E., Bassetti M., Blot S., et al. Review of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients and proposal for a case definition: an expert opinion. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(8):1524–1535. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosgurin O., Leidi A., Farhoumand P.D., Carballo S., Adler D., Reny J.L., et al. Role of intermediate care unit admission and noninvasive respiratory support during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective cohort study. Respiration. 2021;100(8):1–8. doi: 10.1159/000516329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kharat A., Dupuis-Lozeron E., Cantero C., Marti C., Grosgurin O., Lolachi S., et al. Self-proning in COVID-19 patients on low-flow oxygen therapy: a cluster randomised controlled trial. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00692–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00692-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carteaux G., Millán-Guilarte T., De Prost N., Razazi K., Abid S., Thille A.W., et al. Failure of noninvasive ventilation for de novo acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: Role of tidal volume. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(2):282–290. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battaglini D, Robba C, Ball L, Silva PL, Cruz FF, Pelosi P, et al. Noninvasive respiratory support and patient self-inflicted lung injury in COVID-19: a narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.05.024. S0007-0912(21)00340-00348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finfer S., Rocker G. Alveolar overdistension is an important mechanism of persistent lung damage following severe protracted ARDS. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1996;24(5):569–573. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9602400511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyman J.B., Leibner E.S., Tandon P., Egorova N.N., Bassily-Marcus A., Kohli-Seth R., et al. Timing of intubation and in-hospital mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(10):e0254. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez-Romieu A.C., Adelman M.W., Hockstein M.A., Robichaux C.J., Edwards J.A., Fazio J.C., et al. Timing of intubation and mortality among critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients: A single-center cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(11):e1045–e1053. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q., Shen J., Chen L., Li S., Zhang W., Jiang C., et al. Timing of invasive mechanic ventilation in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020;89(6):1092–1098. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papoutsi E., Giannakoulis V.G., Xourgia E., Routsi C., Kotanidou A., Siempos I.I. Effect of timing of intubation on clinical outcomes of critically ill patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of non-randomized cohort studies. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03540-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marini J.J., Gattinoni L. Management of COVID-19 respiratory distress. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2329–2330. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobin M.J., Laghi F., Jubran A. Caution about early intubation and mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00692-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gattinoni L., Chiumello D., Caironi P., Busana M., Romitti F., Brazzi L., et al. COVID-19 pneumonia: different respiratory treatments for different phenotypes? Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1099–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roca O., Caralt B., Messika J., Samper M., Sztrymf B., Hernández G., et al. An index combining respiratory rate and oxygenation to predict outcome of nasal high-flow therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(11):1368–1376. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0589OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leszek A., Wozniak H., Giudicelli-Bailly A., Suh N., Boroli F., Pugin J., et al. Early measurement of ROX index in intermediary care unit is associated with mortality in intubated COVID-19 patients: a retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2022;11(2):365. doi: 10.3390/jcm11020365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang X., Tian S., Guo H. Acute kidney injury and renal replacement therapy in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;90 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim W.H., Hur M., Park S.K., Jung D.E., Kang P., Yoo S., et al. Pharmacological interventions for protecting renal function after cardiac surgery: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of comparative effectiveness. Anaesthesia. 2018;73(8):1019–1031. doi: 10.1111/anae.14227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

After publication, the data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. A proposal with a detailed description of study objectives and statistical analysis plan will be needed for evaluation of the reasonability of requests. Additional materials might also be required during the process of evaluation. De-identified participant data will be provided after approval from the corresponding author and the Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland.