ABSTRACT

Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) producers are an emerging threat to global health, and the hospital water environment is considered an important reservoir of these life-threatening bacteria. We characterized plasmids of KPC-2-producing Citrobacter freundii and Klebsiella variicola isolates recovered from hospital sewage in Japan. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing, whole-genome sequencing analysis, bacterial conjugation, and transformation experiments were performed for both KPC-2 producers. The blaKPC-2 gene was located on the Tn3 transposon-related region from an IncP-6 replicon plasmid that could not be transferred via conjugation. Compared to the blaKPC-2-encoding plasmid of the C. freundii isolate, alignment analysis of plasmids with blaKPC-2 showed that the blaKPC-2-encoding plasmid of the K. variicola isolate was a novel IncP-6/IncF-like hybrid plasmid containing a 75,218-bp insertion sequence composed of IncF-like plasmid conjugative transfer proteins. Carbapenem-resistant transformants harboring blaKPC-2 were obtained for both isolates. However, no IncF-like insertion region was found in the K. variicola donor plasmid of the transformant, suggesting that this IncF-like region is not readily functional for plasmid conjugative transfer and is maintained depending on the host cells. The findings on the KPC-2 producers and novel genetic content emphasize the key role of hospital sewage as a potential reservoir of pathogens and its linked dissemination of blaKPC-2 through the hospital water environment. Our results indicate that continuous monitoring for environmental emergence of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria might be needed to control the spread of these infectious bacteria. Moreover, it will help elucidate both the evolution and transmission pathways of these bacteria harboring antimicrobial resistance.

IMPORTANCE Antimicrobial resistance is a significant problem for global health, and the hospital environment has been recognized as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance. Here, we provide insight into the genomic features of blaKPC-2-harboring isolates of Citrobacter freundii and Klebsiella variicola obtained from hospital sewage in Japan. The findings of carbapenem-resistant bacteria containing this novel genetic context emphasize that hospital sewage could act as a potential reservoir of pathogens and cause the subsequent spread of blaKPC-2 via horizontal gene transfer in the hospital water environment. This indicates that serial monitoring for environmental bacteria possessing antimicrobial resistance may help us control the spread of infection and also lead to elucidating the evolution and transmission pathways of these bacteria.

KEYWORDS: Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella variicola, KPC-2, IncP-6, hospital sewage

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an important threat to public health. In particular, the emergence and spread of carbapenemase-producing bacteria have become a growing problem because these bacteria are resistant to all β-lactams, which are antibiotics commonly used for treatment, thereby limiting therapeutic options (1). The Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) gene is one of the most widely distributed carbapenemase genes worldwide, and KPC producers are mainly found in the United States, Mediterranean Europe, and China (2). The incidence of resistant bacteria is low in Japan, but sporadic isolation of KPC-2 producers in both clinical and environmental samples has been reported (3, 4).

Currently, the dissemination of pan-drug-resistant bacteria, including carbapenemase producers, has been globally facilitated in hospitals. Previous studies identified high abundance of pan-drug-resistant bacteria in hospital amenities, such as sinks, faucets, and drains, and the occurrence of blaKPC-2 in these places represents an emerging environmental issue (5, 6). Tofteland et al. found evidence of possible blaKPC-2 transfer between K. pneumoniae isolates in the environment during a long-term outbreak, indicating that KPC-2 producers could be a local environmental reservoir (7). Thus, elucidating the dissemination mechanism of the bacteria as a reservoir could prevent environmentally mediated outbreaks; however, the genetic role of environmental transmission in KPC-2 producers is not fully understood. The carbapenemase genes, including blaKPC-2, are normally located on mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids, and can be transferred among bacteria from different genera (8). The blaKPC-2 gene has been found on several plasmids with different incompatibility groups, including IncFII, IncN, IncFIB, IncA/C, and IncFIA, and only a few IncP-6 replicon plasmids have been detected (9). IncP-6-type is a broad-host-range plasmid that has demonstrated potential to mediate the horizontal dissemination of AMR genes (8). Nevertheless, the genetic characteristics and gene context responsible for environmental spread remain largely unknown.

In this study, we describe the molecular characterization of Citrobacter freundii and Klebsiella variicola isolates with blaKPC-2-encoding IncP-6 plasmids that were obtained from hospital sewage in Japan. These data will help clarify the genetic and phenotypic features of KPC-2 producers, providing further insights on the mechanism of spread of blaKPC-2 and the need for infection control in the hospital environment.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isolation of KPC-2 producers from hospital sewage.

The emergence of AMR in bacterial infections is a major health threat worldwide, leading to higher medical costs, prolonged hospital stays, and increased mortality rates (10–12). Both CFTMDU and KVTMDU isolates were identified as carbapenemase producers with the modified carbapenem inactivation method (mCIM) and as blaKPC-positive with the GeneXpert system; hence, we performed short- and long-read whole-genome sequencing (WGS) for one isolate from each species. The CFTMDU isolate included a chromosome of 5,093,232 bp and six circularly closed plasmids ranging in length from 4,922 bp to 290,379 bp (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The KVTMDU isolate contained a chromosome of 5,338,792 bp, 13 circularly closed plasmids of 1,452 bp to 224,595 bp, and a linear plasmid of 329,735 bp (see Table S3). The generation of this linear plasmid by the de novo hybrid assembly was considered to be due to the large plasmid size or many repetitive sequences (13), and the acquisition of more sequence data for the isolate could be a solution for the assembly failure. In the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis, CFTMDU and KVTMDU were classified as sequence type 91 (ST91) and ST113, respectively. The results showed that CFTMDU carried AMR genes mediating resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, phenicols, fluoroquinolones, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and tetracyclines. The total genome of KVTMDU included genes mediating resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, phenicols, fluoroquinolones, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, tetracyclines, and fosfomycin. The blaKPC-2 gene was located on plasmids p5_CFTMDU (38,297 bp) and p3_KVTMDU (119,262 bp), and these plasmids had no known AMR genes besides blaKPC-2.

Aquatic environments serve as persistent reservoirs of AMR genes, thereby increasing the risk of AMR transmission and infection with AMR bacteria (14, 15). Recent studies showed that hospital water amenities, such as sinks, faucets, and drains, could be potential sources for the emergence of hospital-based outbreaks of AMR bacteria (6, 16). The clinically important KPC producers have recently been recovered from hospital environmental samples worldwide (17–24), corroborating our findings, although KPC producers have rarely been detected in Japan. These findings, coupled with previous studies (17–24), implicate hospital water samples as environmental reservoirs of pathogens. Because this may lead to the dissemination of blaKPC-2 via hospital environments, infection control approaches should be considered to prevent microbial contamination with these life-threatening isolates within medical establishments on a daily basis.

A recent study suggested that complex premise plumbing systems within hospitals could have areas of stagnation and corrosion that include variable nutrient and microbiological loads and water temperatures suitable for promoting bacterial colonization and biofilm formation, leading to further spread of AMR in the ecosystem (6). Perilli et al. also demonstrated a genetic relationship between KPC-3 producers from clinical specimens and those from wastewater treatment plants near hospitals (25). For these reasons, it is necessary to determine the relationship between hospital sewage and the neighboring water environment to reveal the diffusion pathway through the aquatic networks.

Phylogenetic analysis of KPC-2-producing isolates.

Roary matrix-based gene sequence analysis identified a large pan-genome consisting of 27,802 gene clusters across 20 genomes of the Citrobacter species isolates and 20,047 gene clusters across 69 genomes of the Klebsiella species isolates (see Fig. S1). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that CFTMDU was closely related to the human urine isolate C. freundii SL151 from Sierra Leone (26). The isolate KVTMDU had a close genetic relationship with the human-derived K. variicola 04153260899A from Australia. These analyses showed no characteristic relationship between our KPC-2 producers and other isolates with blaKPC-2 registered in the GenBank genome database (accessed 16 November 2021).

Structural characterization of blaKPC-2-containing plasmids.

PlasmidFinder analysis indicated that the blaKPC-2-containing plasmids p5_CFTMDU and p3_KVTMDU both belonged to the IncP-6 incompatibility group (GenBank accession number JF785550), with similarity scores of 99.9% and 99.8%, respectively. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an IncP-6 replicon carrying blaKPC-2 in a K. variicola isolate. We previously isolated a KPC-2-producing K. pneumoniae strain without an IncP-6 plasmid (GenBank accession number GCA_900322685) from a patient at the Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital (3); however, a blaKPC-2-harboring IncP-6 plasmid has not been isolated from clinical specimens in our hospital. This IncP-6 plasmid has been detected in the effluent of an urban wastewater treatment plant near the hospital (27), suggesting that our strains might have spread via environmental sources rather than clinical specimens.

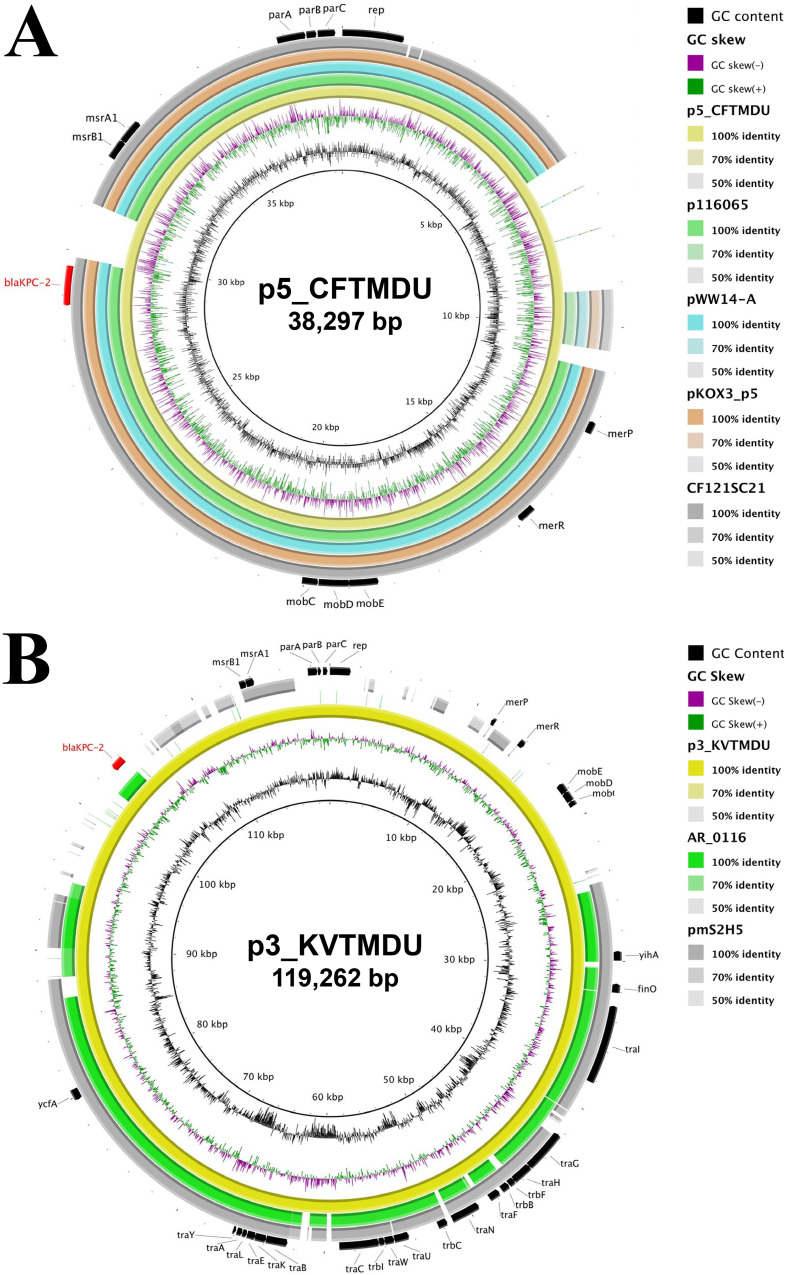

By BLAST analysis, the whole sequence of p5_CFTMDU showed over 99% identity with a C. freundii CF121SC21 plasmid (GenBank accession number LT992437) from Spain (82% query), Klebsiella quasipneumoniae pWW-14A (GenBank accession number NZ_CP080103) from Argentina (83% query), Klebsiella oxytoca pKOX3 (GenBank accession number KY913901) from China (83% query), and Citrobacter sp. strain P116965 (GenBank accession number MN539620) from China (83% query). These plasmids share high background similarity around the blaKPC-2-containing region (Fig. 1A). p3_KVTMDU has 99% identity and shares 61% coverage with the blaKPC-2-noncoding K. pneumoniae pmS2H5 (GenBank accession number LC623933) from Japan and has 99% identity and shares 56% coverage with the blaKPC-2-encoding C. freundii AR_0116 plasmid (GenBank accession number CP032181) of unknown origin (Fig. 1B). The IncP-6 replicon with blaKPC-2 was discovered in various species of bacteria from both clinical and environmental samples, indicating that it can replicate within a broad range of hosts and is involved in the long-term persistence of the plasmids in the environment (19, 27–33). Thus, the IncP-6 replicon could play a key role in the horizontal dissemination of blaKPC-2.

FIG 1.

Circular comparison of blaKPC-2-encoding plasmids with closely related plasmids available in public repositories. The reference sequences of p5_CFTMDU (A) and p3_KVTMDU (B) with their shared region are depicted. Each plasmid is indicated by a ring of different colors, and the color intensity represents the nucleotide identities. The arrows indicate the positions and direction of annotated genes.

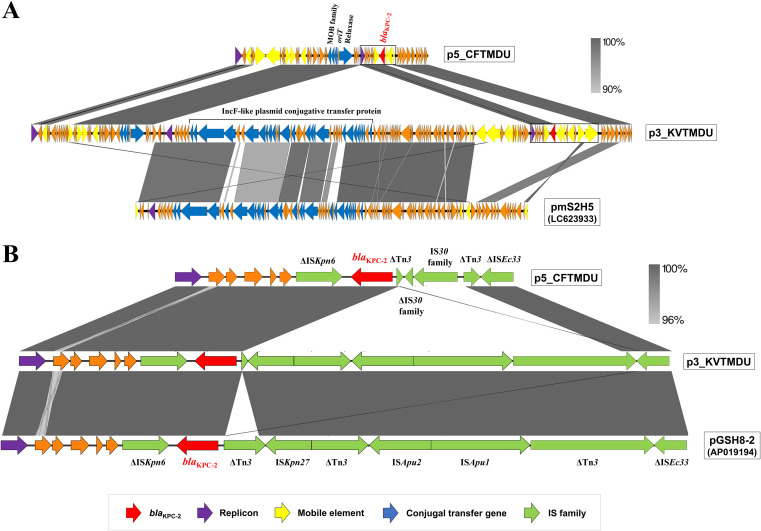

The blaKPC-2-containing plasmids p5_CFTMDU and p3_KVTMDU have a typical IncP-6 backbone with three partition genes and a downstream replication gene. Comparison of the sequence around blaKPC-2 indicated that multiple insertion regions could be associated with the acquisition of blaKPC-2. The Tn3 transposons of p5_CFTMDU and p3_KVTMDU are flanked by the insertion of ΔIS30-IS30 and ISKpn27-ΔTn3-ISApu2-ISApu1, respectively (Fig. 2). The sequence context of the blaKPC-2 site indicated high homology with Aeromonas hydrophila pGSH8-2 (GenBank accession number AP019194) from Japan. The previous analyses of the IncP-6 plasmid with blaKPC-2 indicated its link with Tn3-derived genetic elements, which is responsible for its widespread presence in different countries (19, 28, 29, 32–34). These findings suggest that the Tn3-formed composite transposon is a common vehicle for mediating the spread of blaKPC-2 and that dissemination could contribute to the establishment of emerging clones as major nosocomial pathogens (35).

FIG 2.

Linear comparison among p5_CFTMDU, p3_KVTMDU, and closely related plasmids available in a public database. Alignment of the whole plasmid sequence (A) and the blaKPC-2-surrounding region (B) is shown. The arrows indicate the position and direction of open reading frames and are colored based on gene functional classification. The percentage of sequence homology is provided based on the gray color scale.

The plasmid structure of p5_CFTMDU exhibits high similarity to that of other IncP-6 plasmids with blaKPC-2 that have been isolated from various countries and deposited in GenBank. In contrast, insertion of a 75,218-bp DNA fragment was found between the hypothetical protein and the replication protein in p3_KVTMDU. Notably, this inserted region is based on IncF-like plasmid conjugative transfer proteins, indicating a novel IncP-6/IncF-like hybrid plasmid; the sequence showed 99% identity and 84% coverage with respect to pmS2H5 (GenBank accession number LC623933), which was isolated from hospital sewage in the Gifu prefecture of Japan (unpublished data). This indicates that p3_KVTMDU might have been generated by recombination between the globally distributed blaKPC-2-harboring IncP-6 backbone and the domestic IncF-like region. The IncF plasmid is the most frequently described plasmid type from human and animal sources and is known to carry many AMR genes (8). The colocalization of IncP-6 and IncF-like plasmids may contribute to expanding the ability to disseminate previously unreported AMR genes.

Transferability of blaKPC-2-containing plasmids.

IncP is a broad-host-range incompatibility plasmid that has been shown to mediate the dissemination of AMR genes (36). Nevertheless, p5_CFTMDU and p3_KVTMDU could not be transferred to Escherichia coli C600 and J53 recipient strains via conjugation, suggesting that these plasmids lack transfer-system-related genes. Conjugative plasmids normally carry a set of mobility components (oriT, relaxase, and type IV coupling protein [T4CP]) and the component of the mating channel that assembles a type IV secretion system (T4SS) for self-transfer (37). However, the T4CP and T4SS regions were not detected in p5_CFTMDU. This observation of the plasmid lacking T4CP and T4SS is consistent with the previous theoretical proposal for failed conjugation experiments with the blaKPC-2-encoding IncP-6 plasmid because of the absence of conjugative genes in plasmid transfer (29, 31–33). In contrast, Yao et al. reported that a blaKPC-2-encoding IncP-6 plasmid (GenBank accession number ERR1950686) that showed high similarity to p5_CFTMDU was successfully transferred to E. coli BM21 by conjugation (19). Since these plasmids may differ in their conjugation-related region, this sequence variation appears to be involved in the conjugation ability (see Fig. S2). It might also result from different transferability due to the suitability of the E. coli C600 and J53 recipient strains used in this study for p5_CFTMDU. T4CP and T4SS regions based on the IncF-like sequence were observed in p3_KVTMDU, but their function and interaction in conjugation are not clear; therefore, further investigation is needed to elucidate their involvement in conjugation.

The E. coli HST08 transformants p5TF_CFTMDU and p3TF_KVTMDU were obtained from p5_CFTMDU and p3_KVTMDU, respectively, for which transfer by conjugation was not successful. From the assembled sequence data, the plasmids of the two transformants were completely circularized, and the sizes of p5TF_CFTMDU and p3TF_KVTMDU were 37,770 bp and 43,823 bp, respectively (see Fig. S3). By BLAST analysis, p5TF_CFTMDU and p3TF_KVTMDU showed the highest homology to Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain C79 (GenBank accession number CP040685) from China and C. freundii pCRE12-KPC (GenBank accession number MK050973) from China, respectively. While p5TF_CFTMDU was over 98% identical to p5_CFTMDU, p3TF_KVTMDU had a deletion sequence and was significantly different in size from the donor plasmid. The deletion region included an IncF-like plasmid conjugative transfer protein and was consistent with the insertion sequence found in p3_KVTMDU, compared to p5_CFTMDU, as shown in Fig. 2A. We conducted additional PCR assays to investigate the region using primers for detecting the IncF-like plasmid conjugative transfer pilus traC. PCR bands were detected from the extracted plasmid of p3_KVTMDU but not from that of p3TF_KVTMDU (see Fig. S4). Additionally, the results presented were repeated in an independent electroporation experiment; blaKPC of the transformants was amplified by PCR, while traC was not, suggesting that the insertion sequence was excluded from the plasmid during electroporation (see Fig. S5). These results indicate that the IncP-6 plasmid containing the IncF-like region may not be readily maintained against a different host of E. coli recipient cells, and further analysis of the conjugal function of the IncF-like region from p3_KVTMDU is required.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of KPC-2-producing isolates and their transformants.

The antimicrobial susceptibility profiles according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines are listed in Table 1. All strains showed low MICs for gentamicin, amikacin, and colistin. CFTMDU exhibited resistance to β-lactams, minocycline, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and ciprofloxacin. KVTMDU was resistant to β-lactams, minocycline, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. Transformants of CFTMDU and KVTMDU acquired resistance to most β-lactam antibiotics, including imipenem, meropenem, and doripenem, by obtaining blaKPC-2-containing plasmids, indicating that blaKPC-2 was functional in the recipient strains.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of blaKPC-2-producing isolates, their transformants, and the E. coli HST08 recipient strain

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/mL) fora: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HST08 recipient | KVTMDU donor | KVTMDU transformant | CFTMDU donor | CFTMDU transformant | |

| Piperacillin | ≤0.5 (S) | >64 (R) | >64 (R) | >64 (R) | >64 (R) |

| Sulbactam-ampicillin | ≤2/4 (S) | >8/16 (R) | >8/16 (R) | >8/16 (R) | >8/16 (R) |

| Sulbactam-cefoperazone | ≤8/8 | >32/32 | 32/32 | >32/32 | >32/32 |

| Tazobactam-piperacillin | ≤4/2 (S) | >4/64 (R) | >4/64 (R) | >4/64 (R) | >4/64 (R) |

| Cefazolin | 2 (S) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) |

| Cefotiam | ≤0.5 (S) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) |

| Cefotaxime | ≤0.5 (S) | >32 (R) | 4 (R) | >32 (R) | 4 (R) |

| Ceftazidime | ≤0.5 (S) | >32 (R) | 16 (R) | >32 (R) | 16 (R) |

| Cefpodoxime | ≤1 (S) | >4 (R) | >4 (R) | >4 (R) | >4 (R) |

| Cefepime | ≤0.5 (S) | >16 (R) | 4 (SDD) | >16 (R) | 8 (SDD) |

| Cefozopran | ≤0.5 | >16 | 16 | >16 | >16 |

| Flomoxef | ≤0.5 | >16 | 16 | >16 | 16 |

| Aztreonam | ≤0.5 (S) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) | >16 (R) |

| Imipenem | ≤0.25 (S) | 16 (R) | 8 (R) | >16 (R) | 8 (R) |

| Meropenem | ≤0.25 (S) | >16 (R) | 4 (R) | >16 (R) | 4 (R) |

| Doripenem | ≤1 (S) | 8 (R) | 2 (I) | >8 (R) | 4 (R) |

| Ceftazidime-dipicolinic acid | ≤2 | >8 | >8 | >8 | 8 |

| Imipenem-dipicolinic acid | ≤1 | >4 | >4 | >4 | >4 |

| Meropenem-dipicolinic acid | ≤1 | >4 | 4 | >4 | 4 |

| Gentamicin | ≤0.25 (S) | ≤0.25 (S) | ≤0.25 (S) | 0.5 (S) | ≤0.25 (S) |

| Amikacin | ≤1 (S) | 4 (S) | ≤1 (S) | 8 (S) | ≤1 (S) |

| Tobramycin | ≤1 (S) | 8 (I) | ≤1 (S) | 8 (I) | ≤1 (S) |

| Minocycline | 1 (S) | >8 (R) | 0.5 (S) | >8 (R) | 1 (S) |

| Fosfomycin | ≤32 (S) | 128 (I) | ≤32 (S) | 128 (I) | ≤32 (S) |

| Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim | ≤9.5/0.5 (S) | >38/2 (R) | ≤9.5/0.5 (S) | >38/2 (R) | ≤9.5/0.5 (S) |

| Levofloxacin | ≤0.25 (S) | 4 (I) | ≤0.25 (S) | >4 (R) | ≤0.25 (S) |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.25 (S) | >2 (R) | ≤0.25 (S) | >2 (R) | ≤0.25 (S) |

| Colistin | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 |

S, susceptible; I, intermediate; R, resistant; SDD, susceptible-dose dependent.

Conclusions.

In summary, we have provided insight into the genomic features of C. freundii and K. variicola isolates with the blaKPC-2-harboring IncP-6 plasmid from hospital sewage in Japan. The findings of carbapenem-resistant bacteria containing this novel genetic context emphasize the importance of hospital sewage as a potential reservoir of pathogens and its associated spread of blaKPC-2 through hospital water environments. This indicates that continuous monitoring of environmental contamination with bacteria with AMR may be needed for infection control and the elucidation of both the evolution and transmissible pathways of resistant bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling and bacterial isolation.

In June 2021, using culture swabs, we obtained samples from five different locations of a single sewage tank in the intensive care unit of the Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan). Each sample was plated on an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-selective agar plate (Kanto Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) and incubated at 37°C under aerobic conditions. C. freundii strain CFTMDU and K. variicola strain KVTMDU were recovered and identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Bremen, Germany) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The mCIM was performed as described in CLSI document M100-S30 (38). The carbapenemase-encoding genes (blaIMP-1, blaVIM, blaKPC, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48) were screened using the GeneXpert system with the Xpert Carba-R assay (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The MICs of 28 antibiotics were determined using commercial Dry Plate DP31 and DP45 (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan), which are commonly used as antimicrobial susceptibility testing plates for Enterobacterales. The results were analyzed using an IA01 MIC Pro image analyzer (Eiken Chemical). The results were interpreted according to CLSI document M100-S30 (38).

WGS analysis of KPC-2-producing isolates.

Genomic DNA was extracted using a NucleoBond high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), following the manufacturer's protocol, from formed colonies of each isolate. Sequencing libraries for Illumina short reads were generated using a Nextera DNA Flex library preparation kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), and short-read WGS was conducted on an Illumina MiSeq platform. Long-read WGS was performed using a Nanopore GridION sequencer (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, United Kingdom) using a short-read eliminator XS kit (Circulomics Inc., Baltimore, MD, USA), ligation sequencing kit, and R9.4.1 flow cell (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). The de novo hybrid assembly of both short and long reads was performed using Unicycler v0.4.8 (39). Gene annotation was carried out using DFAST v1.2.4 (40), the Prokka v1.14.6 annotation pipeline (41), and Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) v2.0 (42). The ST, AMR genes, and plasmid replicon types were identified using the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (http://www.genomicepidemiology.org) online database MLST v2.0 (43), ResFinder v4.1 (44), and PlasmidFinder v2.0 (45), respectively. The ST of KVTMDU was determined according to a previously reported method (46). Transposons and insertion sequences were determined using ISfinder (47). The oriTfinder web server was used to detect the presence of conjugal transfer components originating from the transfer oriT, relaxase, T4CP, and T4SS region of the plasmid (48). Multiple and pairwise sequence comparisons between the blaKPC-2-containing plasmids and closely related plasmids from the GenBank genome database were performed using the BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG) v0.95 (49). The genetic contexts of the plasmids were compared and visualized using EasyFig v2.2.2 (50). The accession numbers of isolates used in this study are presented in Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material.

Pan-genome analysis was performed to determine the number of core and accessory genes, as described previously (51). The complete genome sequences of 19 Citrobacter species strains based on previous research (52) and 68 Klebsiella species strains, which are completed at the assembly level, were downloaded from the GenBank genome database (accessed 16 November 2021) (see Table S4). The genome annotated by the Prokka v1.14.6 annotation pipeline was used in a pan-genome analysis with Roary v3.13.0 (53). FastTree v2.1.10 was used to construct approximate maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees (54), and the phylogenetic tree was visualized using the online tool Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6 (55).

Plasmid characterization.

Transfer of plasmids carrying blaKPC-2 was attempted by bacterial conjugation and transformation assays. Bacterial conjugation was conducted using rifampicin-resistant E. coli C600 and sodium azide-resistant E. coli J53 as the recipients, following the agar mating method as described previously with some modifications (56). Briefly, equal amounts of donor and recipient cultures were mixed and transferred to tryptic soy agar plates. After 16 to 20 h of incubation at 37°C, presumptive transconjugants were selected on BTB agar plates containing meropenem (2 μg/mL) or cefotaxime (2 μg/mL) plus rifampicin (50 μg/mL) for E. coli C600 recipients and meropenem (2 μg/mL) or cefotaxime (2 μg/mL) plus sodium azide (100 μg/mL) for E. coli J53 recipients. The transformation experiments were performed using plasmid DNA extracted with a NucleoBond Xtra midikit (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The plasmid DNA was electroporated into E. coli HST08 Premium Electro-Cells (TaKaRa Bio) using a MicroPulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and the transformants were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with meropenem (2 μg/mL) or cefotaxime (2 μg/mL). The blaKPC gene of the transformants was screened using EmeraldAmp MAX PCR master mix (TaKaRa Bio) and previously reported primers (57). The plasmids of transformants were confirmed by short-read WGS using a Nextera DNA Flex library preparation kit and an Illumina MiniSeq platform. The de novo assembly of short reads was conducted using Unicycler v0.4.8 (39). PCR amplification was performed using EmeraldAmp MAX PCR master mix and specific primers for the detection of traC (KVTMDU_traC-F, 5′-AGCAGTTCGCTTCCACCTGCA-3′; KVTMDU_traC-R, 3′-AGCGTAATCATGCACGCGTTGATGAC-5′) using the following thermal cycling conditions: 30 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the support from the staff of the Department of Clinical Laboratory, Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital. We thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

This work was partially supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (https://www.amed.go.jp) under grant JP20wm0125007.

None of the authors has any financial relationships with commercial entities that have an interest in the subject of the manuscript.

Y.N. and R.S. designed, organized, and coordinated this project. Y.O. was the chief investigator and was responsible for data analysis. I.P. and R.K. contributed to the data interpretation. Y.O. and R.S. wrote the initial and final drafts of the manuscript. All authors revised the drafts of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Yoko Nukui, Email: y-nukui.infe@tmd.ac.jp.

Ryoichi Saito, Email: r-saito.mi@tmd.ac.jp.

Christopher A. Elkins, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonomo RA, Burd EM, Conly J, Limbago BM, Poirel L, Segre JA, Westblade LF. 2018. Carbapenemase-producing organisms: a global scourge. Clin Infect Dis 66:1290–1297. 10.1093/cid/cix893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Duin D, Doi Y. 2017. The global epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence 8:460–469. 10.1080/21505594.2016.1222343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saito R, Takahashi R, Sawabe E, Koyano S, Takahashi Y, Shima M, Ushizawa H, Fujie T, Tosaka N, Kato Y, Moriya K, Tohda S, Tojo N, Koike R, Kubota T. 2014. First report of KPC-2 carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Japan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:2961–2963. 10.1128/AAC.02072-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekizuka T, Yatsu K, Inamine Y, Segawa T, Nishio M, Kishi N, Kuroda M. 2018. Complete genome sequence of a blaKPC-2-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae strain isolated from the effluent of an urban sewage treatment plant in Japan. mSphere 3:e00314-18. 10.1128/mSphere.00314-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picao RC, Cardoso JP, Campana EH, Nicoletti AG, Petrolini FV, Assis DM, Juliano L, Gales AC. 2013. The route of antimicrobial resistance from the hospital effluent to the environment: focus on the occurrence of KPC-producing Aeromonas spp. and Enterobacteriaceae in sewage. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 76:80–85. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kizny Gordon AE, Mathers AJ, Cheong EYL, Gottlieb T, Kotay S, Walker AS, Peto TEA, Crook DW, Stoesser N. 2017. The hospital water environment as a reservoir for carbapenem-resistant organisms causing hospital-acquired infections: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 64:1435–1444. 10.1093/cid/cix132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tofteland S, Naseer U, Lislevand JH, Sundsfjord A, Samuelsen O. 2013. A long-term low-frequency hospital outbreak of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae involving intergenus plasmid diffusion and a persisting environmental reservoir. PLoS One 8:e59015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozwandowicz M, Brouwer MSM, Fischer J, Wagenaar JA, Gonzalez-Zorn B, Guerra B, Mevius DJ, Hordijk J. 2018. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:1121–1137. 10.1093/jac/dkx488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandt C, Viehweger A, Singh A, Pletz MW, Wibberg D, Kalinowski J, Lerch S, Muller B, Makarewicz O. 2019. Assessing genetic diversity and similarity of 435 KPC-carrying plasmids. Sci Rep 9:11223. 10.1038/s41598-019-47758-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwaber MJ, Navon-Venezia S, Kaye KS, Ben-Ami R, Schwartz D, Carmeli Y. 2006. Clinical and economic impact of bacteremia with extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1257–1262. 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1257-1262.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasink LB, Edelstein PH, Lautenbach E, Synnestvedt M, Fishman NO. 2009. Risk factors and clinical impact of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 30:1180–1185. 10.1086/648451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q, Li X, Li W, Du X, He JQ, Tao C, Feng Y. 2015. Influence of carbapenem resistance on mortality of patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 5:11715. 10.1038/srep11715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George S, Pankhurst L, Hubbard A, Votintseva A, Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, Mathers A, Norris R, Navickaite I, Eaton C, Iqbal Z, Crook DW, Phan HTT. 2017. Resolving plasmid structures in Enterobacteriaceae using the MinION Nanopore sequencer: assessment of MinION and MinION/Illumina hybrid data assembly approaches. Microb Genom 3:e000118. 10.1099/mgen.0.000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marti E, Variatza E, Balcazar JL. 2014. The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol 22:36–41. 10.1016/j.tim.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chia PY, Sengupta S, Kukreja A, Ponnampalavanar SSL, Ng OT, Marimuthu K. 2020. The role of hospital environment in transmissions of multidrug-resistant gram-negative organisms. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 9:29. 10.1186/s13756-020-0685-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Geyter D, Blommaert L, Verbraeken N, Sevenois M, Huyghens L, Martini H, Covens L, Pierard D, Wybo I. 2017. The sink as a potential source of transmission of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the intensive care unit. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 6:24. 10.1186/s13756-017-0182-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chagas TP, Seki LM, da Silva DM, Asensi MD. 2011. Occurrence of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in hospital wastewater. J Hosp Infect 77:281. 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu W, Espedido B, Feng Y, Zong Z. 2016. Citrobacter freundii carrying blaKPC-2 and blaNDM-1: characterization by whole genome sequencing. Sci Rep 6:30670. 10.1038/srep30670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yao Y, Lazaro-Perona F, Falgenhauer L, Valverde A, Imirzalioglu C, Dominguez L, Canton R, Mingorance J, Chakraborty T. 2017. Insights into a novel blaKPC-2-encoding IncP-6 plasmid reveal carbapenem-resistance circulation in several Enterobacteriaceae species from wastewater and a hospital source in Spain. Front Microbiol 8:1143. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomi R, Matsuda T, Yamamoto M, Chou PH, Tanaka M, Ichiyama S, Yoneda M, Matsumura Y. 2018. Characteristics of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in wastewater revealed by genomic analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02501-17. 10.1128/AAC.02501-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakkas H, Bozidis P, Ilia A, Mpekoulis G, Papadopoulou C. 2019. Antimicrobial resistance in bacterial pathogens and detection of carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from hospital wastewater. Antibiotics (Basel) 8:85. 10.3390/antibiotics8030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eda R, Maehana S, Hirabayashi A, Nakamura M, Furukawa T, Ikeda S, Sakai K, Kojima F, Sei K, Suzuki M, Kitasato H. 2021. Complete genome sequencing and comparative plasmid analysis of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from hospital sewage water in Japan. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 24:180–182. 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamal AJ, Mataseje LF, Brown KA, Katz K, Johnstone J, Muller MP, Allen VG, Borgia S, Boyd DA, Ciccotelli W, Delibasic K, Fisman DN, Khan N, Leis JA, Li AX, Mehta M, Ng W, Pantelidis R, Paterson A, Pikula G, Sawicki R, Schmidt S, Souto R, Tang L, Thomas C, McGeer AJ, Mulvey MR. 2020. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in hospital drains in southern Ontario, Canada. J Hosp Infect 106:820–827. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki Y, Nazareno PJ, Nakano R, Mondoy M, Nakano A, Bugayong MP, Bilar J, Perez M V, Medina EJ, Saito-Obata M, Saito M, Nakashima K, Oshitani H, Yano H. 2020. Environmental presence and genetic characteristics of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae from hospital sewage and river water in the Philippines. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e01906-19. 10.1128/AEM.01906-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perilli M, Bottoni C, Pontieri E, Segatore B, Celenza G, Setacci D, Bellio P, Strom R, Amicosante G. 2013. Emergence of blaKPC-3-Tn4401a in Klebsiella pneumoniae ST512 in the municipal wastewater treatment plant and in the university hospital of a town in central Italy. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 1:217–220. 10.1016/j.jgar.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leski TA, Taitt CR, Bangura U, Ansumana R, Stenger DA, Wang Z, Vora GJ. 2016. Finished genome sequence of the highly multidrug-resistant human urine isolate Citrobacter freundii strain SL151. Genome Announc 4:e01225-16. 10.1128/genomeA.01225-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sekizuka T, Inamine Y, Segawa T, Hashino M, Yatsu K, Kuroda M. 2019. Potential KPC-2 carbapenemase reservoir of environmental Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas caviae isolates from the effluent of an urban wastewater treatment plant in Japan. Environ Microbiol Rep 11:589–597. 10.1111/1758-2229.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naas T, Bonnin RA, Cuzon G, Villegas MV, Nordmann P. 2013. Complete sequence of two KPC-harbouring plasmids from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1757–1762. 10.1093/jac/dkt094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai X, Zhou D, Xiong W, Feng J, Luo W, Luo G, Wang H, Sun F, Zhou X. 2016. The IncP-6 plasmid p10265-KPC from Pseudomonas aeruginosa carries a novel ΔISEc33-associated blaKPC-2 gene cluster. Front Microbiol 7:310. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Yuan M, Chen H, Chen X, Jia Y, Zhu X, Bai L, Bai X, Fanning S, Lu J, Li J. 2017. First report of Klebsiella oxytoca strain simultaneously producing NDM-1, IMP-4, and KPC-2 carbapenemases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00877-17. 10.1128/AAC.00877-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kukla R, Chudejova K, Papagiannitsis CC, Medvecky M, Habalova K, Hobzova L, Bolehovska R, Pliskova L, Hrabak J, Zemlickova H. 2018. Characterization of KPC-encoding plasmids from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in a Czech hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02152-17. 10.1128/AAC.02152-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu X, Yu X, Shang Y, Xu H, Guo L, Liang Y, Kang Y, Song L, Sun J, Yue F, Mao Y, Zheng B. 2019. Emergence and characterization of a novel IncP-6 plasmid harboring blaKPC-2 and qnrS2 genes in Aeromonas taiwanensis isolates. Front Microbiol 10:2132. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghiglione B, Haim MS, Penzotti P, Brunetti F, D’Amico González G, Di Conza J, Figueroa-Espinosa R, Nunez L, Razzolini MTP, Fuga B, Esposito F, Vander Horden M, Lincopan N, Gutkind G, Power P, Dropa M. 2021. Characterization of emerging pathogens carrying blaKPC-2 gene in IncP-6 plasmids isolated from urban sewage in Argentina. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11:722536. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.722536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen P, Wei Z, Jiang Y, Du X, Ji S, Yu Y, Li L. 2009. Novel genetic environment of the carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase KPC-2 among Enterobacteriaceae in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4333–4338. 10.1128/AAC.00260-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Q, Jia X, Zhou M, Zhang H, Yang W, Kudinha T, Xu Y. 2020. Emergence of ST11-K47 and ST11-K64 hypervirulent carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in bacterial liver abscesses from China: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Emerg Microbes Infect 9:320–331. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1721334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schluter A, Szczepanowski R, Puhler A, Top EM. 2007. Genomics of IncP-1 antibiotic resistance plasmids isolated from wastewater treatment plants provides evidence for a widely accessible drug resistance gene pool. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31:449–477. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smillie C, Garcillan-Barcia MP, Francia MV, Rocha EP, de la Cruz F. 2010. Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 74:434–452. 10.1128/MMBR.00020-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2020. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 30th informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S30. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. 2017. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 13:e1005595. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanizawa Y, Fujisawa T, Nakamura Y. 2018. DFAST: a flexible prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline for faster genome publication. Bioinformatics 34:1037–1039. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seemann T. 2014. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30:2068–2069. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. 2008. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, Marvig RL, Jelsbak L, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. 2012. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 50:1355–1361. 10.1128/JCM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, Aarestrup FM, Larsen MV. 2012. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2640–2644. 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carattoli A, Zankari E, Garcia-Fernandez A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, Moller Aarestrup F, Hasman H. 2014. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3895–3903. 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barrios-Camacho H, Aguilar-Vera A, Beltran-Rojel M, Aguilar-Vera E, Duran-Bedolla J, Rodriguez-Medina N, Lozano-Aguirre L, Perez-Carrascal OM, Rojas J, Garza-Ramos U. 2019. Molecular epidemiology of Klebsiella variicola obtained from different sources. Sci Rep 9:10610. 10.1038/s41598-019-46998-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. 2006. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 34:D32–D36. 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X, Xie Y, Liu M, Tai C, Sun J, Deng Z, Ou HY. 2018. oriTfinder: a web-based tool for the identification of origin of transfers in DNA sequences of bacterial mobile genetic elements. Nucleic Acids Res 46:W229–W234. 10.1093/nar/gky352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alikhan NF, Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Beatson SA. 2011. BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons. BMC Genomics 12:402. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. 2011. EasyFig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27:1009–1010. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahazu S, Prah I, Ayibieke A, Sato W, Hayashi T, Suzuki T, Iwanaga S, Ablordey A, Saito R. 2021. Possible dissemination of Escherichia coli sequence type 410 closely related to B4/H24RxC in Ghana. Front Microbiol 12:770130. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.770130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu H, Wang X, Yu X, Zhang J, Guo L, Huang C, Jiang X, Li X, Feng Y, Zheng B. 2018. First detection and genomics analysis of KPC-2-producing Citrobacter isolates from river sediments. Environ Pollut 235:931–937. 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M, Wong VK, Reuter S, Holden MT, Fookes M, Falush D, Keane JA, Parkhill J. 2015. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 31:3691–3693. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. 2009. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 26:1641–1650. 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Letunic I, Bork P. 2007. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 23:127–128. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prah I, Ayibieke A, Mahazu S, Sassa CT, Hayashi T, Yamaoka S, Suzuki T, Iwanaga S, Ablordey A, Saito R. 2021. Emergence of oxacillinase-181 carbapenemase-producing diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Ghana. Emerg Microbes Infect 10:865–873. 10.1080/22221751.2021.1920342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dallenne C, Da Costa A, Decré D, Favier C, Arlet G. 2010. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother 65:490–495. 10.1093/jac/dkp498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1 to S4 and Fig. S1 to S5. Download aem.00019-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.5 MB (1.5MB, pdf)