Abstract

Female infertility is a heterogeneous disorder with a variety of complex causes, including inflammation and oxidative stress, which are also closely associated with the pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). As a new treatment for PCOS, berberine (BER), a natural compound from Berberis, has been clinically applied recently. However, the mechanisms underlying the association between BER and embryogenesis are still largely unknown. In this study, effects of BER on preimplantation development were evaluated under both normal and inflammatory culture conditions induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in mice. Our data first suggest that BER itself (25 nM) does not affect embryo quality or future developmental potency; however, it can effectively alleviate LPS-induced embryo damage by mitigating apoptosis via reactive oxygen species (ROS)-/caspase-3-dependent pathways and by suppressing proinflammatory cytokines via inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway during preimplantation embryonic development. In addition, skewed cell lineage specification in the inner cell mass (ICM) and primitive endoderm (PE) caused by LPS can also be successfully rescued with BER. In summary, these findings for the first time demonstrate the nontoxicity of low doses of BER and its antiapoptotic and antioxidative properties on embryonic cells during mammalian preimplantation development.

Keywords: blastocyst embryo, cell lineage specification, DNA damage, antiapoptotic, antiinflammatory, ROS

A low dose of berberine is nontoxic to embryos and can successfully alleviate LPS-induced damage by diminishing apoptosis and proinflammatory cytokines as well as correcting skewed cell lineages during preimplantation embryonic development.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, over 10% of women worldwide have infertility and subfertility, a problem that affects a significant proportion of humanity. Female infertility is a heterogenous disorder that results from a variety of complex reasons, such as endocrine conditions, infections, immunological disorders, genetic issues, and environmental factors [1]. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common causes of female infertility, and it is generally believed that inflammation and oxidative stress are two of the main driving factors in the pathophysiology of PCOS, leading to metabolic aberration and ovarian dysfunction [2–4]. PCOS is a complex disorder that is often diagnosed by the presence of ovarian cysts, hyperandrogenism, and metabolic abnormalities (such as hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance) [5]. Although lifestyle changes (such as behavioral, dietary, and exercise regimens) and therapeutic options (such as insulin sensitizers) are available and in wide use for the treatment of PCOS, the side effects of long-time treatments and the relatively low efficacy have triggered complementary and alternative treatments, such as the use of Chinese herbal medicines for PCOS [5–7].

Berberine (BER), a natural isoquinoline alkaloid compound from the herbal roots and other parts of Berberis, has been widely utilized in traditional Chinese medicine practices for a long time to treat diseases such as diarrhea, diabetes, and cancer [8–11]. A number of research studies have proved that BER possesses antibacterial and antiinflammatory properties as an antioxidant [12, 13]. Studies also proved that BER can inhibit the inflammation and oxidative stress through suppressing the nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B (NF-κB) cells and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, as well as decreasing TLR4-mediated inflammatory enzymes and cytokines in certain cell types of rodents and bovines [14–16]. Furthermore, recent studies confirm that BER displays beneficial effects in the treatment of diabetes and insulin resistance via stimulation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity [17, 18]. As insulin resistance is also tightly associated with PCOS as well as chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, BER was then tested for the treatment of PCOS and it showed a promising prospect in alleviating those metabolic and hormonal disorders [19, 20]. More importantly, BER has been clinically applied for those infertile women with PCOS undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles, and it showed that 3 months of BER treatment could increase the pregnancy rate with reduced ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. In addition, compared with metformin, BER exhibited a more pronounced therapeutic effect and achieved more live births with fewer gastrointestinal adverse events [20, 21]. Although it is suggested that BER is involved in the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) and MAPK pathways [22] as well as the suppression of androgen receptors [23] during the treatment of PCOS, the detailed mechanisms are still unclear and the effects of BER on early embryo development during IVF cycles of PCOS patients are also unknown.

Mammalian preimplantation embryo development begins with the zygote and concludes with the formation of a blastocyst [24]. To form a competent blastocyst embryo, three major transcriptional and morphogenetic events should take place concurrently: maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) [25, 26]; compaction and polarization [27, 28]; and cell fate allocation to form trophectoderm (TE) and inner cell mass (ICM), with the latter to further separate into the epiblast (EPI) and primitive endoderm (PE) [29–31]. Accumulating evidence suggests that both inflammation and oxidative stress can severely affect these cellular events and embryo quality [32–34]. Compared with other antioxidants, there are very few studies focusing on BER and early embryogenesis. Zhang and colleagues reported that BER can elevate miRNA-21 expression and Bcl-2 levels, leading to increased developmental rates and cell numbers of mouse blastocysts with decreased apoptotic cells [35]. Regulation of miRNAs and developmental enhancement via BER has also been confirmed in porcine in-vitro-matured oocytes [36] and IVF embryos [37] by the same team using the same concentration (0.1 μg/ml which equals 0.3 μM). Huang and colleagues tested different concentrations of BER (2.5, 5, 10 μM) and found that there are dose-dependent beneficial (2.5 μM) and harmful (5 and 10 μM) effects of BER on mouse oocyte maturation and fertilization and fetal development, which involve distinct caspase-3 activities and reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [38, 39]. It is noteworthy that the effect of BER at lower concentrations has not been studied or reported yet during early embryogenesis.

In the present study, for the first time, low concentrations of BER were added into either the regular culture medium, or medium supplemented with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that causes inflammation, embryo damage, and female infertility [40–44], all of which are also the characteristics detected in PCOS patients [2, 3, 45]. Our data first suggest that low concentration of BER (25 nM) during preimplantation culture is nontoxic and it will not affect future developmental potency after embryo transfer. Moreover, this low concentration can effectively alleviate LPS-induced apoptosis, oxidation, and skewed cell lineage specification during mouse preimplantation development.

Materials and methods

The ethics

All animal related procedures and methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations. All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst (2017-0071).

Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals and media were purchased from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA, USA). Berberine (BER, B3251) was first dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as aliquots of 100 μM stock and stored at −20°C. Lipopolysaccharide (L4391) was first dissolved in water as aliquots of 5 mg/ml stock and stored at −20°C. During medium preparation, BER and LPS were then dissolved in KSOM culture medium (MR106D) at the indicated concentrations and cultured for 4 days (zygote to blastocyst). As the control (CTR) group, 0.1% DMSO and/or 0.32% water was added into KSOM.

Generation and culture of zygotes

Eight- to ten-week-old B6D2F1 females (stock number: 100006, The Jackson Laboratory) were superovulated by intraperitoneal injection of 10 IU pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG, BioVendor, Asheville, NC, USA), followed 48 h later by 10 IU human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Females were caged with B6D2F1 males right after hCG injection. The presence of a vaginal plug next day morning was defined as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). Plugged females were euthanized at 20 h post hCG injection. Zygotes were released from oviducts in M2 medium (MR015D), and cumulus cells were removed in hyaluronidase medium (MR051F) as described previously [46]. Zygotes were then cultured in KSOM with or without LPS [42] (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 μg/ml) and/or BER [38, 39] (0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 nM) at different concentrations at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 5% O2 balanced in N2.

Outgrowth assay

To test the blastocyst embryo quality [47], blastocysts were collected from the different groups (after 4 days of in vitro culture starting from one-cell zygote stage) and then cultured in DMEM (Lonza, Allendale, NJ, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA, USA) and 1× GlutaMAX (Thermo Fish Scientific). Blastocysts were cultured for hatching and outgrowth for 3 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 5% O2 balanced in N2, after which the outgrowth morphology was evaluated as described previously [48].

Immunofluorescence

After 4 days of in vitro culture starting from the one-cell zygote stage, those embryos that reached the blastocyst stage from different groups were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and briefly washed in PBS, followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min. Embryos were then blocked in blocking solution (PBS with 10% FBS and 0.1% Triton) for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. All primary antibodies were diluted 1:200 using the blocking solution containing goat anti-OCT4 (Abcam, ab27985); mouse anti-CDX2 (BioGenex, MU392A-UC); rabbit anti-NANOG (Abcam, ab80892); rabbit anti-caspase-3 (Proteintech, 19677–1-AP); and goat anti-SOX17 (R&D Systems, AF1924). After three washes, embryos were incubated with suitable secondary antibodies (1:500 dilution, Alexa Fluor, Thermo Fisher Scientific: donkey anti-Goat 488, A32814; donkey anti-Rabbit 546, A10040; donkey anti-Mouse 647, A31571) for 1 h at room temperature in dark. After two washes, DNA was stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) before final wash and mounting for imaging under a Nikon A1 spectral detector confocal with FLIM module. Z-stacks (20× objective, 8 μm sections) were collected, and maximum projection was applied.

TUNEL and EdU assays

The Click-iT Plus EdU cell proliferation kit (C10638, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for EdU (5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine) labeling. Briefly, blastocysts were incubated in KSOM containing 10 μM EdU for 30 min. Then, blastocysts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X 100 at room temperature for 20 min, followed by the cocktail reaction of the kit. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining was carried out using the in situ cell death detection kit (11684795910, Roche) according to the manual. Briefly, after the EdU staining, blastocysts were washed and labeled with TUNEL reaction mixture at 37°C for 30 min, protected from light. Last, embryos were stained with DAPI and imaged under the confocal microscope. The total cell number was counted based on DAPI staining and positive cells were defined by a fixed threshold across all images of the same batch as described previously [49, 50].

Detection of ROS and caspase-3

CellROX Green Reagent (C10444, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to detect the ROS level as previously described [51]. Briefly, blastocysts were incubated in KSOM supplemented with 5 μM CellROX Green Reagent at 37°C for 30 min. After this, embryos were fixed for later staining with caspase-3 antibody and DAPI as described in the Immunofluorescence section. The images were acquired under identical capture settings and the relative intensities were analyzed by the ImageJ software [52].

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from blastocyst embryos using the Roche High Pure RNA isolation kit (number: 11828665001), and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (number: 170-8891, Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA). All quantitative polymerase chain reactions (qPCR) were performed on the CFX96 Touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA) and the intron-spanning primers used for qPCRs are as follows: Tnf (also known as TNFα), 5′-CAAATGGCCTCCCTCTCAT and 5′-CACTTGGTGGTTTGCTACGA; Il6 (also known as Il-6), 5′-TACCACTTCACAAGTCGGAGGC and 5′-CTGCAAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTC; Myd88, 5′-ACCTGTGTCTGGTCCATTGCCA and 5′-GCTGAGTGCAAACTTGGTCTGG; Rela (also known as p65 NF-κB or Nfkb), 5′-TCCTGTTCGAGTCTCCATGCAG and 5′-GGTCTCATAGGTCCTTTTGCGC; Nfkbia (also known as IκBα or Ikba), 5′-TCGCTCTTGTTGAAATGTGGG and 5′-GTCTGCGTCAAGACTGCTACAC; and Gapdh, 5′-TCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCCA and 5′-ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATTCA. Transcripts of the examined genes were quantified in triplicate and calculated relative to the transcription of the housekeeping gene Gapdh. The specificity of qPCR reaction was confirmed by both single peaks in the melt curves and gel electrophoresis.

Embryo transfer and dissection of E7.5 embryos

Adult CD-1 female mice were caged with individual vasectomized CD-1 males overnight. Female mice with plugs next day morning (E0.5) were separated out for future use as the pseudopregnant recipients. Early blastocyst embryos which had been cultured in different media for 3 days were transferred into the E2.5 recipient females using nonsurgical embryo transfer (mNSET 60010, ParaTechs, USA). Recipient female mice were euthanized 5 days post embryo transfer and E7.5 embryos were dissected, positioned, and imaged as described previously [49].

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times. Percentage data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variances, and a value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. The number of embryos used in each experiment is listed either in the figure (Figure 1) or in the figure legends.

Figure 1.

Effects of BER and LPS on preimplantation development. (A) BER (from 12.5 to 100 nM) exhibited nontoxicity during preimplantation embryo culture based on blastocyst formation rates and outgrowth rates. (B) LPS at the concentration of 16 μg/ml significantly inhibited preimplantation embryo development, causing a decrease in both blastocyst formation rate and outgrowth rate. (C) BER starting from the concentration of 25 nM effectively alleviated LPS-induced embryonic damage. (D, E) BER at 25 nM showed nontoxicity and it effectively alleviated LPS-induced embryonic damage based on both blastocyst formation and outgrowth. Black arrows: embryos showing shrinkage; red arrowheads: embryos with severe fragmentations; white arrowheads: embryos that failed to hatch with blastomeres trapped in the zona pellucida during outgrowth culture. n (in the bar), the number of embryos used in the experiment. Scale bars, 100 μm. *, P < 0.05.

Results

BER at 25 nM shows nontoxicity and can effectively alleviate LPS-induced embryonic damage

Four different low concentrations of BER (12.5, 25, 50, and 100 nM) were added into KSOM culture medium and after 4 days of culture, none of them showed detrimental effects based on the blastocyst formation rates and outgrowth rates (Figure 1A). We then tested different concentrations of LPS (1, 2, 4, 8, 16 μg/ml) and as shown in Figure 1B, 16 μg/ml LPS in KSOM culture medium caused a significant decrease in both blastocyst formation rate and outgrowth rate (no embryos survived with 32 μg/ml LPS, data not shown). To see if BER could rescue this LPS-mediated embryonic damage, different concentrations of BER were added into KSOM medium supplemented with 16 μg/ml LPS. As shown in Figure 1C, 25 nM BER (and beyond) exhibited a significant rescue. Finally, we put these selected concentrations together and performed the last experiment, which reconfirmed that 25 nM BER is nontoxic and this low concentration can effectively alleviate LPS-induced embryonic damage (Figure 1D and E). In all the following experiments, BER was used at 25 nM and LPS was used at 16 μg/ml.

BER can ameliorate LPS-induced severe DNA breaks

To explore the mechanisms underlying the rescue of BER on LPS-treated embryos, fluorescent whole-mount TUNEL assay and EdU labeling were first performed to assess the DNA breaks and cell proliferation, respectively (Figure 2A). Although around half of the embryos under LPS treatment could still develop to blastocyst stage, these blastocysts displayed a notable decrease in total cell number (Figure 2B) and a significant increase in DNA breaks (Figure 2C), which phenotypes were successfully rescued by BER. Again, when only BER itself was added into the medium, no obvious difference could be detected between the control group and BER-only group (Figure 2B and C), suggesting the nontoxicity of BER on early embryogenesis. Regarding EdU labeling, all groups exhibited a similar rate of new DNA synthesis after incubation with EdU for 30 min (Figure 2D), suggesting that the retardation of LPS-treated embryos mainly occurred prior to blastocyst formation.

Figure 2.

Fluorescent whole-mount TUNEL assay and EdU labeling were applied to evaluate the DNA breaks and cell proliferation, respectively. (A) Representative images showing TUNEL assay and EdU labeling on different groups of blastocyst embryos. (B, C) A significant decrease of total cell number and a severe increase of DNA breaks were detected in LPS-treated embryos, and these phenotypes can be effectively rescued by BER. (D) Blastocyst embryos of each group showed a similar rate of new DNA synthesis during EdU labeling test. The number of embryos used in the experiment (CTR: 30, BER only: 33, LPS only: 41, LPS + BER: 39). Scale bar, 50 μm. *, P < 0.05.

BER can mitigate LPS-triggered excess ROS and caspase-3

We then tested the ROS and caspase-3 levels, which are well-recognized markers for oxidative stress/damage and cell apoptosis, respectively (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B, LPS triggered a significant elevation in the level of ROS. Moreover, LPS triggered a significant increase in caspase-3 activity, a crucial mediator of programmed cell death (Figure 3C). Notably, supplementation of BER successfully inhibited the excess of ROS and caspase-3 triggered by LPS (Figure 3B and C), indicating that BER treatment can inhibit apoptosis during preimplantation embryo development through ROS-dependent and caspase-3-dependent pathways. Once again, when only BER itself was added into the culture medium, no difference could be detected between the control and BER-only embryos, suggesting a low dose of BER (25 nM) does not affect those intrinsic redox homeostasis or apoptotic status during early embryogenesis (Figure 3B and C).

Figure 3.

Levels of ROS and caspase-3 were tested to assess the oxidative stress/damage and cell apoptosis, respectively. (A) Representative images showing ROS and caspase-3 activities in different groups of blastocyst embryos. (B, C) A significant increase in both ROS and caspase-3 activity was displayed in those LPS-treated embryos, which phenotypes can be effectively rescued by a low dose of 25 nM BER. The number of embryos used in the experiment (CTR: 21, BER only: 21, LPS only: 28, LPS + BER: 28). Scale bar, 50 μm. *, P < 0.05.

BER can rescue LPS-induced reduction of ICM specification

To gain more insight into the mechanisms underlying the rescue of BER on LPS-treated embryos, we also examined the first cell lineage specification, which is a key event during preimplantation embryonic development. As shown in Figure 4A, immunofluorescence of OCT4 (ICM marker) and CDX2 (TE marker) was performed in different groups of blastocysts. The data show that the percentage of OCT4 positive cells was significantly reduced in LPS-treated blastocysts (Figure 4B), which concordantly caused a notable increase in the percentage of CDX2 positive cells (Figure 4C), when compared with the control group. Strikingly, addition of BER successfully rescued this LPS-induced skewed ICM/TE cell lineages during blastocyst formation (Figure 4B and C). Same as in other assays, no difference could be detected between the control and BER-only embryos, suggesting low dose of BER (25 nM) does not affect those genes or pathways that are essential for cell differentiation and lineage specification during early embryogenesis (Figure 4B and C).

Figure 4.

IF of OCT4 (ICM marker) and CDX2 (TE marker) was performed in different groups of blastocysts. (A) Representative images showing the IF of OCT4 (ICM marker) and CDX2 (TE marker) in blastocysts. (B, C) LPS treatment caused a significant reduction in the percentage of OCT4-positive ICM cells and a notable increase in the percentage of CDX2-positive TE cells, and this altered ICM/TE cell lineages can be successfully rescued by a low dose of 25 nM BER. The number of embryos used in the experiment (CTR: 25, BER only: 27, LPS only: 34, LPS + BER: 26). Scale bar, 50 μm. *, P < 0.05.

BER can also rescue LPS-induced reduction of PE specification

We further investigated the fidelity of the second embryonic lineage specification in which ICM cells segregate into the PE and EPI. As shown in Figure 5A, the immunofluorescence of SOX17 (PE marker) and NANOG (EPI marker) was performed in different groups of blastocysts. The data show that it is the specification of PE lineage (Figure 5B) but not EPI (Figure 5C), that is more vulnerable to LPS treatment. Concordant with the decrease of the PE ratio, an increase of the CDX2-positive TE lineage was also detected in the LPS group (Figure 5D). Importantly, these altered cell lineage specifications were successfully corrected when BER was added to the embryos cultured under LPS treatment (Figure 5B and D), suggesting that BER can also rescue those genes and pathways that are required for the second cell lineage specification during blastocyst formation.

Figure 5.

IF of SOX17 (PE marker), NANOG (EPI marker) and CDX2 (TE marker) was performed in different groups of blastocysts. (A) Representative images showing the IF of SOX17 (PE marker), NANOG (EPI marker), and CDX2 (TE marker) in blastocysts. (B) The LPS-induced decreased percentage of SOX17-positive PE cells can be effectively recovered by BER rescue. (C) No significant difference was detected on the percentage of NANOG-positive EPI cells among all groups. (D) Concordant with the rescue of the PE lineage specification under LPS treatment, BER also amended those over-assigned CDX2-positive TE cells induced by LPS. The number of embryos used in the experiment (CTR: 19, BER only: 20, LPS only: 31, LPS + BER: 30). Scale bar, 50 μm. *, P < 0.05.

BER rescue during preimplantation safeguards postimplantation development

To further test the developmental potency of blastocyst embryos under different treatments, embryo transfer was performed and E7.5 embryo dissection was conducted accordingly (Figure 6A). As shown in Figure 6B, there was no significant difference among all groups with respect to the percentage of decidua, suggesting those transferred blastocysts from different groups possessed similar potency of implantation and decidualization (but note the decreasing tendency in the LPS group). After dissection, embryos were graded as normal or abnormal (degraded or empty decidua), and a significant reduction of normal embryos was found in the LPS group (Figure 6C), suggesting that LPS treatment during preimplantation period can cause carryover damage to embryos which are beyond implantation and decidualization stage. Strikingly, BER rescue during preimplantation successfully restored the developmental potency of those embryos under LPS treatment, exhibiting very similar ratios of postimplantation decidua/normal embryos as shown in the control (Figure 6B and C).

Figure 6.

Early blastocysts were transferred into recipient females and E7.5 embryo dissection was conducted later to further evaluate the developmental potency of preimplantation embryos under different treatments. (A) Representative images showing the morphology of E7.5 embryos derived from the blastocysts under different treatments. (B) Although no significant difference was detected among all groups, LPS-treated blastocysts showed a decreasing tendency on decidua rate (the number of embryos transferred into the pseudopregnant recipients was the denominator, and the number of deciduae was the numerator). (C) After dissection of all deciduae, embryos derived from LPS-treated blastocysts exhibited a significant reduction of normal embryos, which can be successfully rescued by addition of low dose of BER (25 nM) into LPS-containing medium during preimplantation culture (the number of embryos transferred into the recipients was the denominator, and the number of normal embryos detected was the numerator). The number of embryos used in the experiment (CTR: 89 embryos were transferred into 6 recipient females and 58 decidua were detected at E7.5, where 44 live embryos were found with 10 died embryos and 4 empty decidua; BER only: 144 embryos were transferred into 9 recipient females and 82 decidua were detected at E7.5, where 49 live embryos were found with 22 died embryos and 11 empty decidua; LPS only: 148 embryos were transferred into 9 recipient females and 67 decidua were detected at E7.5, where 28 live embryos were found with 25 died embryos and 14 empty decidua; LPS + BER: 108 embryos were transferred into 7 recipient females and 61 decidua were detected at E7.5, where 46 live embryos were found with 11 died embryos and 4 empty decidua). Scale bar, 100 μm. *, P < 0.05.

BER suppresses LPS-induced proinflammatory factors in embryos

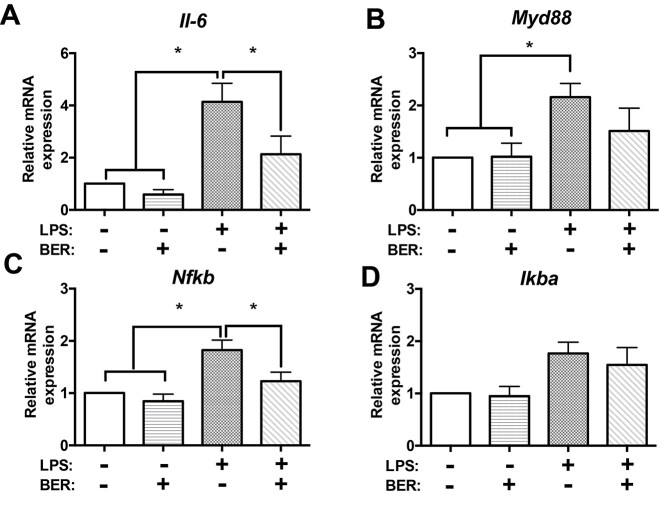

Given the previous finding in cultured cell lines which showed that BER can inhibit LPS-induced inflammatory response via downregulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [53], we also tested this pathway in our cultured blastocyst embryos. As the expression of the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα is not detectable during preimplantation development (data not shown), we only measured the other proinflammatory cytokine IL6. Quantitative qPCR showed that LPS triggered a severe elevation in Il-6 expression, which can be successfully inhibited by BER (Figure 7A). Similar results or trends were also found in other key members of this signaling pathway: the activator MyD88 (myeloid differentiation factor 88) (Figure 7B), and the transcription factor NF-κB (Figure 7C). Lastly, we examined the expression of IκBα, a major inhibitor of NF-κB proteins (IκBs). As shown in Figure 7D, no obvious difference was detected in all groups, although both LPS group and BER rescue group exhibited an increasing tendency. Taken together, these data suggest that LPS triggers the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, increasing proinflammatory factors (such as proinflammatory cytokine Il-6, the activator MyD88, and the transcription factor Nfkb) in preimplantation embryos, which can be efficiently reduced by BER treatment.

Figure 7.

BER suppresses LPS-triggered NF-κB signaling pathway and pro-inflammatory factors in preimplantation embryos. Quantitative qPCR data showed the mRNA expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine Il-6 (A), the activator Myd88 (B), and transcription factor Nfkb (C) were significantly elevated by LPS treatment, when compared with the control group and BER-only group. Notably, this elevated NF-κB signaling pathway with pro-inflammatory factors can be successfully or largely inhibited in those preimplantation embryos rescued with BER. (D) The expression level of IκBα, which encodes the main inhibitor of NF-κB proteins, was similar in all groups, although an increasing tendency was detected in both LPS group and BER rescue group. Transcripts of examined genes were quantified in triplicates with experiment repeated three times and 20 blastocyst embryos per group were processed in each replication. *, P < 0.05.

Discussion

Although the etiology of female infertility is highly heterogenous and patients may have different genetic predispositions and epigenetic modifications, it has been shown that high levels of inflammation and oxidative stress is a common sign for most women with PCOS and unexplained infertility [2, 3, 54]. Studies on early embryogenesis also revealed that excessive ROS can result in the disruption of early embryo development through the induction of apoptotic pathway and oxidation of molecules (lipids, proteins, and DNA etc.) [55–57]. Considering all of this, berberine (BER) becomes a promising candidate due to: (1) its anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory property [12, 13]; (2) long history in traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of diarrhea, infertility, and other diseases [20, 58]; (3) its promising prospect in correcting both metabolic and hormonal disorders accompanied with PCOS [19, 20]. It is noteworthy that even though BER has been applied during clinical trials for PCOS patients undergoing IVF cycles [21], detailed mechanisms underlying the improvement are still largely unknown. Also, whereas gastrointestinal side effects have been carefully evaluated during the trials, how much remaining BER was left in circulation and its effects on early embryogenesis was not investigated. In this study, instead of exploring the function of BER from the maternal side, we evaluated the outcome of BER on preimplantation embryo development. Our data suggest: (1) LPS addition can cause embryo damage with elevated oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory factors, mimicking the environment inside PCOS patients; (2) BER is powerful and just a low dose (25 nM) can successfully rescue those LPS-triggered embryo damages; (3) This low working concentration is safe for early embryogenesis.

It is also worth noting that, although BER has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory property in certain cell types and organisms [14–16], this function has not been evaluated in mammalian embryogenesis. By using preimplantation embryo in vitro culture system, our data indicate that BER can effectively inhibit LPS-triggered activation of NF-κB signaling pathway and pro-inflammatory factors (such as pro-inflammatory cytokine Il-6, the activator MyD88, and the transcription factor Nfkb) in preimplantation embryos. Given the fact that preimplantation embryos are sensitive to maternal systemic inflammation [42], our data may explain, why BER and metformin are similar on alleviating insulin resistance [20] but eventually BER showed a more pronounced therapeutic effect with more live births than metformin in PCOS patients undergoing IVF treatment [21]: BER also exerts its anti-inflammation function which protects not only maternal environment but also embryogenesis itself. Regarding BER’s antiapoptotic and antioxidative property, our study is consistent with previous reports on mammalian embryo development [35, 39]. However, compared with those reported concentrations applied in vitro (0.3 μM [35] and 2.5 μM [39]), our study clearly shows a much lower concentration (25 nM) can still successfully alleviate LPS-induced embryonic damage by mitigating apoptosis via ROS-/caspase-3-dependent pathways (although mouse strain and culture medium may alter the minimum effective concentration). Meanwhile, this low concentration (25 nM) also safeguards the safety of BER application on early embryo development based on our in vitro assays and in vivo embryo transfer experiment, supporting the suggestion that BER is safe and promising for those premenopausal women with PCOS who want to get pregnant [58]. It is important to clarify that PCOS is also known to alter ovarian function and ovulation and may have an impact on oocyte quality as well [5, 59], all of which could not be evaluated in our present study where in vitro cultured mouse preimplantation embryos were applied as the model (oocyte in vitro maturation system was not employed in this study due to its short period in mice and the complexity of maturation medium which normally contains hormones, serum, growth factor, and so on if high developmental competence is required). In addition, PCOS is not defined only by inflammation, but also by other symptoms, such as impaired insulin signaling and androgen elevation. Therefore, our in vitro LPS challenge model and the findings of this study could not translate exactly for PCOS patients. Nonetheless, more studies are still needed, regarding the dosage of BER in vitro versus in vivo (e.g., when it is applied for PCOS patients undergoing IVF cycles), short-term versus long-term (e.g., its long-lasting effects), and different animal models.

In addition to apoptosis and oxidation, we also detected skewed lineage specification in LPS-treated blastocysts, which is consistent with a previous report showing that maternal LPS challenge can cause reduced ICM in the embryo [42]. Although BER exerts rescue on ICM/TE lineage allocation under LPS challenge, detailed mechanism is not illustrated in the present study. We hypothesize that BER may regulate those target factors and/or pathways [50, 60, 61] critical for ICM specification via direct or indirect way; or it is due to the biased vulnerability of ICM to oxidation and proinflammatory factors that can be well rescued as long as antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties are applied. These possible scenarios may also explain the phenotype of altered PE lineage but not EPI lineage during the second cell fate determination under LPS challenge, providing a new perspective on embryo lineage differentiation. In order to fully understand the mechanism and potential function of BER on transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory processes, further study is needed to assess transcriptome wide effects and changes. Alternatively, embryonic stem cells and trophoblast stem cells may serve as good models to explore BER function in different cell lineages during embryogenesis.

In conclusion, by using preimplantation embryo culture system as well as embryo transfer assay, out data suggest that low dose of BER (25 nM) does not affect embryo quality or future developmental potency. Furthermore, this low dose of BER can successfully alleviate LPS-induced damage by diminishing ROS-/caspase-3-dependent apoptosis and NF-κB mediated proinflammatory factors during preimplantation embryo development. Last but not the least, BER can also successfully rescue the skewed cell lineage specification in ICM and PE under LPS challenge, safeguarding the formation of competent embryos for future development.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are either available in the article or will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

XM performed all experiments, analyzed the data, and helped with manuscript preparation; WC designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The confocal microscopy data were gathered in the Light Microscopy Facility and Nikon Center of Excellence at the Institute for Applied Life Sciences, UMass Amherst with support from the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center.

Footnotes

† Grant Support: This work was supported by faculty start-up fund and grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NIH/NICHD R21HD098686) and USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture/Hatch (NIFA/Hatch #1024792 to WC). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Contributor Information

Xiaosu Miao, Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA.

Wei Cui, Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA; Animal Models Core Facility, Institute for Applied Life Sciences (IALS), University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Reference

- 1. Senapati S. Infertility: a marker of future health risk in women? Fertil Steril 2018; 110:783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goodarzi MO, Dumesic DA, Chazenbalk G, Azziz R. Polycystic ovary syndrome: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnosis. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011; 7:219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gonzalez F. Inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: underpinning of insulin resistance and ovarian dysfunction. Steroids 2012; 77:300–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xie F, Zhang J, Zhai M, Liu Y, Hu H, Yu Z, Zhang J, Lin S, Liang D, Cao Y. Melatonin ameliorates ovarian dysfunction by regulating autophagy in PCOS via the PI3K-Akt pathway. Reproduction 2021; 162:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Velez LM, Seldin M, Motta AB. Inflammation and reproductive function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome dagger. Biol Reprod 2021; 104:1205–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moini Jazani A, Nasimi Doost Azgomi H, Nasimi Doost Azgomi A, Nasimi Doost Azgomi R. A comprehensive review of clinical studies with herbal medicine on polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Daru 2019; 27:863–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. of the Drug and Therapeutics Committee of the Pediatric Endocrine Society, Geller DH, Pacaud D, Gordon CM, Misra M. State of the art review: emerging therapies: the use of insulin sensitizers in the treatment of adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2011; 2011:9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21899727/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kong W, Wei J, Abidi P, Lin M, Inaba S, Li C, Wang Y, Wang Z, Si S, Pan H, Wang S, Wu J et al. Berberine is a novel cholesterol-lowering drug working through a unique mechanism distinct from statins. Nat Med 2004; 10:1344–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tang LQ, Ni WJ, Cai M, Ding HH, Liu S, Zhang ST. Renoprotective effects of berberine and its potential effect on the expression of beta-arrestins and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in streptozocin-diabetic nephropathy rats. J Diabetes 2016; 8:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen Y, Chen Y, Liang Y, Chen H, Ji X, Huang M. Berberine mitigates cognitive decline in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model by targeting both tau hyperphosphorylation and autophagic clearance. Biomed Pharmacother 2020; 121:109670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takahara M, Takaki A, Hiraoka S, Adachi T, Shimomura Y, Matsushita H, Nguyen TTT, Koike K, Ikeda A, Takashima S, Yamasaki Y, Inokuchi T et al. Berberine improved experimental chronic colitis by regulating interferon-γ- and IL-17A-producing lamina propria CD4+ T cells through AMPK activation. Sci Rep 2019; 9:11934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peng L, Kang S, Yin Z, Jia R, Song X, Li L, Li Z, Zou Y, Liang X, Li L, He C, Ye G et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of berberine against Streptococcus agalactiae. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015; 8:5217–5223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kwon OJ, Kim MY, Shin SH, Lee AR, Lee JY, Seo BI, Shin MR, Choi HG, Kim JA, Min BS, Kim GN, Noh JS et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Rhei Rhizoma and Coptidis Rhizoma mixture on reflux esophagitis in rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016; 2016:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang Q, Liu P, Wu X, Liu W, Shen X, Lan T, Xu S, Peng J, Xie X, Huang H. Berberine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced extracelluar matrix accumulation and inflammation in rat mesangial cells: involvement of NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2011; 331:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim DG, Choi JW, Jo IJ, Kim MJ, Lee HS, Hong SH, Song HJ, Bae GS, Park SJ. Berberine ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in mouse inner medullary collecting duct-3 cells by downregulation of NF-κB pathway. Mol Med Rep 2020; 21:258–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao C, Wang Y, Yuan X, Sun G, Shen B, Xu F, Fan G, Jin M, Li X, Liu G. Berberine inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of inflammatory cytokines by suppressing TLR4-mediated NF-kB and MAPK signaling pathways in rumen epithelial cells of Holstein calves. J Dairy Res 2019; 86:171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yin J, Hu R, Chen M, Tang J, Li F, Yang Y, Chen J. Effects of berberine on glucose metabolism in vitro. Metabolism 2002; 51:1439–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee YS, Kim WS, Kim KH, Yoon MJ, Cho HJ, Shen Y, Ye JM, Lee CH, Oh WK, Kim CT, Hohnen-Behrens C, Gosby A et al. Berberine, a natural plant product, activates AMP-activated protein kinase with beneficial metabolic effects in diabetic and insulin-resistant states. Diabetes 2006; 55:2256–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wei W, Zhao H, Wang A, Sui M, Liang K, Deng H, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Guan Y. A clinical study on the short-term effect of berberine in comparison to metformin on the metabolic characteristics of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol 2012; 166:99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li MF, Zhou XM, Li XL. The effect of Berberine on polycystic ovary syndrome patients with insulin resistance (PCOS-IR): a meta-analysis and systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018; 2018:2532935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. An Y, Sun Z, Zhang Y, Liu B, Guan Y, Lu M. The use of berberine for women with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing IVF treatment. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014; 80:425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang N, Liu X, Zhuang L, Liu X, Zhao H, Shan Y, Liu Z, Li F, Wang Y, Fang J. Berberine decreases insulin resistance in a PCOS rats by improving GLUT4: dual regulation of the PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2020; 110:104544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xiang D, Lu J, Wei C, Cai X, Wang Y, Liang Y, Xu M, Wang Z, Liu M, Wang M, Liang X, Li L et al. Berberine ameliorates prenatal dihydrotestosterone exposure-induced autism-like behavior by suppression of androgen receptor. Front Cell Neurosci 2020; 14:87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arny M, Nachtigall L, Quagliarello J. The effect of preimplantation culture conditions on murine embryo implantation and fetal development. Fertil Steril 1987; 48:861–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Latham KE, Solter D, Schultz RM. Activation of a two-cell stage-specific gene following transfer of heterologous nuclei into enucleated mouse embryos. Mol Reprod Dev 1991; 30:182–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schall PZ, Ruebel ML, Latham KE. A new role for SMCHD1 in life's master switch and beyond. Trends Genet 2019; 35:948–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sutherland AE, Calarco-Gillam PG. Analysis of compaction in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev Biol 1983; 100:328–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Houliston E, Maro B. Posttranslational modification of distinct microtubule subpopulations during cell polarization and differentiation in the mouse preimplantation embryo. J Cell Biol 1989; 108:543–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fleming TP. A quantitative analysis of cell allocation to trophectoderm and inner cell mass in the mouse blastocyst. Dev Biol 1987; 119:520–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marikawa Y, Alarcon VB. Establishment of trophectoderm and inner cell mass lineages in the mouse embryo. Mol Reprod Dev 2009; 76:1019–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Frum T, Ralston A. Cell signaling and transcription factors regulating cell fate during formation of the mouse blastocyst. Trends Genet 2015; 31:402–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Puscheck EE, Awonuga AO, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Rappolee DA. Molecular biology of the stress response in the early embryo and its stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015; 843:77–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guerin P, El Mouatassim S, Menezo Y. Oxidative stress and protection against reactive oxygen species in the pre-implantation embryo and its surroundings. Hum Reprod Update 2001; 7:175–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma R. Oxidative stress and its implications in female infertility - a clinician's perspective. Reprod Biomed Online 2005; 11:641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang C, Shi YR, Liu XR, Cao YC, Zhen D, Jia ZY, Jiang JQ, Tian JH, Gao JM. The anti-apoptotic role of Berberine in preimplantation embryo in vitro development through regulation of miRNA-21. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0129527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dai J, Huang X, Zhang C, Luo X, Cao S, Wang J, Liu B, Gao J. Berberine regulates lipid metabolism via miR-192 in porcine oocytes matured in vitro. Vet Med Sci 2021; 7:950–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang JL, Zhang C, Liu B, Huang XM, Dai JG, Tian JH, Gao JM. Function of berberine on porcine in vitro fertilization embryo development and differential expression analysis of microRNAs. Reprod Domest Anim 2019; 54:520–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Huang CH, Huang ZW, Ho FM, Chan WH. Berberine impairs embryonic development in vitro and in vivo through oxidative stress-mediated apoptotic processes. Environ Toxicol 2018; 33:280–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang CH, Wang FT, Chan WH. Dose-dependent beneficial and harmful effects of berberine on mouse oocyte maturation and fertilization and fetal development. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2020; 9:431–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dekel N, Gnainsky Y, Granot I, Racicot K, Mor G. The role of inflammation for a successful implantation. Am J Reprod Immunol 2014; 72:141–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Deb K, Chaturvedi MM, Jaiswal YK. A 'minimum dose' of lipopolysaccharide required for implantation failure: assessment of its effect on the maternal reproductive organs and interleukin-1alpha expression in the mouse. Reproduction 2004; 128:87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Williams CL, Teeling JL, Perry VH, Fleming TP. Mouse maternal systemic inflammation at the zygote stage causes blunted cytokine responsiveness in lipopolysaccharide-challenged adult offspring. BMC Biol 2011; 9:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Agrawal V, Jaiswal MK, Jaiswal YK. Gonadal and nongonadal FSHR and LHR dysfunction during lipopolysaccharide induced failure of blastocyst implantation in mouse. J Assist Reprod Genet 2012; 29:163–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jaiswal YK, Jaiswal MK, Agrawal V, Chaturvedi MM. Bacterial endotoxin (LPS)-induced DNA damage in preimplanting embryonic and uterine cells inhibits implantation. Fertil Steril 2009; 91:2095–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gonzalez F, Rote NS, Minium J, Kirwan JP. Increased activation of nuclear factor kappaB triggers inflammation and insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:1508–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cui W, Marcho C, Wang Y, Degani R, Golan M, Tremblay KD, Rivera-Perez JA, Mager J. MED20 is essential for early embryogenesis and regulates NANOG expression. Reproduction 2019; 157:215–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim J, Lee J, Jun JH. Advantages of the outgrowth model for evaluating the implantation competence of blastocysts. Clin Exp Reprod Med 2020; 47:85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cui W, Dai X, Marcho C, Han Z, Zhang K, Tremblay KD, Mager J. Towards functional annotation of the preimplantation transcriptome: An RNAi screen in mammalian embryos. Sci Rep 2016; 6:37396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cui W, Cheong A, Wang Y, Tsuchida Y, Liu Y, Tremblay KD, Mager J. MCRS1 is essential for epiblast development during early mouse embryogenesis. Reproduction 2020; 159:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Miao X, Sun T, Barletta H, Mager J, Cui W. Loss of RBBP4 results in defective inner cell mass, severe apoptosis, hyperacetylated histones and preimplantation lethality in micedagger. Biol Reprod 2020; 103:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Su J, Miao X, Archambault D, Mager J, Cui W. ZC3H4-a novel Cys-Cys-Cys-His-type zinc finger protein-is essential for early embryogenesis in micedagger. Biol Reprod 2021; 104:325–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 2012; 9:671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang H, Shan Y, Wu Y, Xu C, Yu X, Zhao J, Yan J, Shang W. Berberine suppresses LPS-induced inflammation through modulating Sirt1/NF-kappaB signaling pathway in RAW264.7 cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2017; 52:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weiss G, Goldsmith LT, Taylor RN, Bellet D, Taylor HS. Inflammation in reproductive disorders. Reprod Sci 2009; 16:216–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Agarwal A, Saleh RA, Bedaiwy MA. Role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of human reproduction. Fertil Steril 2003; 79:829–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jamil M, Debbarh H, Aboulmaouahib S, Aniq Filali O, Mounaji K, Zarqaoui M, Saadani B, Louanjli N, Cadi R. Reactive oxygen species in reproduction: harmful, essential or both? Zygote 2020; 28:255–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rizzo A, Roscino MT, Binetti F, Sciorsci RL. Roles of reactive oxygen species in female reproduction. Reprod Domest Anim 2012; 47:344–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rondanelli M, Infantino V, Riva A, Petrangolini G, Faliva MA, Peroni G, Naso M, Nichetti M, Spadaccini D, Gasparri C, Perna S. Polycystic ovary syndrome management: a review of the possible amazing role of berberine. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2020; 301:53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Palomba S, Daolio J, La Sala GB. Oocyte competence in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2017; 28:186–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Paul S, Knott JG. Epigenetic control of cell fate in mouse blastocysts: the role of covalent histone modifications and chromatin remodeling. Mol Reprod Dev 2014; 81:171–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cui W, Mager J. Transcriptional regulation and genes involved in first lineage specification during preimplantation development. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol 2018; 229:31–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are either available in the article or will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.