Abstract

Background

The myths and conspiracy theories on the COVID-19 vaccine cause people to be hesitant and maleficent towards the vaccine.

Objectives

To assess COVID-19 vaccine-related awareness, attitude and acceptance and to assess reasons for refusing the vaccine among undergraduate Jimma University Institute of Health students.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 387 undergraduate students of Jimma University Institute of Health. Self-administered questionnaires were used to collect the data and summarized by descriptive statistics. A multivariable regression model was used to assess predictable variables for good awareness and positive attitude. A p value of < 0.05 was used to declare the statistical association.

Results

Only 41% of the students had a good awareness of the COVID-19 vaccine, and more than half, 224 (57.9%) of them had a positive attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccine. Age [(AOR: 95% CI) 1.18 (1.03, 1.35)] and having good awareness [(AOR: 95% CI) 2.39 (1.55, 3.68)] were associated with positive attitude of students towards the COVID-19 vaccine. However, only 27.1% of the students were willing to take the vaccine for COVID-19. Afraid of long term effects (49.1%), not being convinced of the safety standards (38.8%), lack of information about the vaccine (37.2%), and too short time for development (39.9%) was common reasons for refusing the COVID-19 vaccine.

Conclusions

According to the present study, the majority of the participants had a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine. However, only less than half of the participants had a good awareness of the vaccine. In addition, the acceptability of the vaccine is low. Afraid of long term effects, not being convinced of the safety profile, lack of information about the vaccine, and the time used for the development were the common reasons for refusing the vaccine. Therefore, all stakeholders are advised to increase awareness, positive attitude, and acceptance of the vaccine.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine, Novel coronavirus vaccine, Jimma

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. The first case of COVID-19 was reported from China Wuhan city on December 12, 2019 [2]. The virus is transmitted through large droplets generated during coughing or sneezing of symptomatic and asymptomatic patients [3]. During the outbreak, the only strategy was to reduce the spread. Wearing masks, alcohol-based hand sanitizer, social distancing, travel restrictions, school closures, and partial or complete lockdowns were used as the prevention strategy [4]. So far, they were able to slow the disease progression.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a pandemic [5]. Since its emergency, the pandemic has spread rapidly, resulting in a global health, social, economic, and political crisis [6]. Political scientists cannot eradicate the virus or cure the disease. However, the impact of COVID-19 will ultimately be determined by politics. Currently, there is well-developed scientific knowledge of crisis policy in specific areas, such as finance, energy, natural disasters and pandemics [7]. The interpretation and response of a pandemic have always been a political act as the decision to impose border control, quarantine the population, public information management, and take an attitude towards others is never freed from such things. Political and medical leaders of governments, national agencies, and international organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) manage data and figures to control the pandemic [8].

The virus has infected people in over 220 countries. More than 213,345,924 people were infected, and 4,454,131 deaths were reported on August 24, 2021.

Myths and conspiracies about the vaccination are proliferating, putting the community in a bind. Myths and conspiracies may create apprehension and malice toward the COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccine hesitancy was named one of the top ten worldwide dangers to public health by the World Health Organization [8, 9]. Three factors influence vaccine acceptance. These are confidence, convenience, and complacency [10]. Confidence is trust in the safety, efficacy, delivery system, and policymakers [11]. Many people doubt safety, and it is challenging for healthcare providers, policymakers, community leaders, and governments [12–14]. The relative ease of availability to the vaccine is vaccination convenience [15]. Vaccine complacency is a low recognized risk of vaccine-preventable illness and unfavorable attitudes about vaccines.

AP-NORC poll in the United States reported only 50% of Americans were willing to take the COVID-19 vaccination, 31% were unsure, and 20% refused the vaccine [16]. Another study found that around 58% were willing to take the vaccination, 32% were unsure, and 11% did not intend to be vaccinated [17]. The other study reported 67% of Americans were willing to accept the vaccine [18]. The study in selected Universities of Northeast Ethiopia revealed 69.3% of the participants were intended to be vaccinated as soon as the vaccine was available [19]. The other study conducted in China reported that 91.3% of the participants accepted the vaccine [20].

The COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) facility strives to deliver a minimum of 2 billion doses of the vaccine to concerned countries of the world in 2021, which includes at least 1.3 billion doses funded by donors to the 92 lower income countries. COVAX facility allocated 7,620,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccine for Ethiopia and about 2,184,000 doses imported by the time the study was conducted.

Ethiopia started vaccinations on March 20 and has only immunized a fraction of the population. As the Ministry of Health plans, 20% of the population in Ethiopia will be vaccinated by the end of 2021. However, it is critical to comprehend the awareness, attitude, and willingness to accept the vaccine. Therefore, assessing awareness, attitude, acceptance and the reasons for refusal will aid in developing and implementing an effective pandemic-control strategy [1]. Therefore, the study aimed to assess Jimma University undergraduate institute of health students awareness, attitudes, acceptance, and the reasons for refusing the vaccine.

Methods

Setting and period

The study was conducted at Jimma University. Jimma University is located in Jimma city 350 km Southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Jimma University is one of the largest and comprehensive public research Universities in Ethiopia. Jimma University Institute of Health has three faculties. These are Health Sciences, Medical science, and Public Health.

Study design

A cross-sectional study design was employed.

Sample size and sampling technique

The sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula: n = Z2P(1−P)/d2, where P = 0.5 (50%) and Z = 1.96 (95% CI), degree of error = 5% and non-respondent rate = 5%. Finally, after adding a 5% non-response rate (384 + 19), the total sample size was 403. Students were selected randomly.

Study population

Randomly selected undergraduate students of Jimma University Institute of Health were included in the study. Students who were unwilling to participate and unable to give the required information were excluded from the study.

Data collection tools and technique

A structured questionnaire was adopted from previous studies [17, 21]. The questionnaire was prepared in English. The questionnaire consists of the following parts.

Sociodemographic characteristics: age, sex, religion, department, year of study and area of origin.

Awareness towards COVID-19 vaccines: ever heard of about COVID-19 vaccine, where you get COVID-19 vaccine-related information, COVID-19 vaccines are effective, overdose of COVID-19 vaccines are dangerous, COVID-19 vaccines might cause allergic reaction and COVID-19 vaccines might increase autoimmune disease.

Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccines: I believe a vaccine can help control the spread of COVID-19, if I knew I had been infected with COVID-19 before, I will get the vaccine if it is available, when everyone else is vaccinated against COVID-19, then I do not have to get vaccinated, the COVID-19 vaccine is essential for us, the newly discovered COVID-19 vaccine is safe, I will take COVID-19 vaccine without any hesitation, I will also encourage my family/friends/relatives to get vaccinated, it is not possible to reduce the incidence of COVID-19 without vaccination, the COVID-19 vaccine should be distributed equally to all of us.

Willingness to take vaccine: do you take COVID-19 vaccine if freely available for students?

Reasons for refusing the vaccine: too short a time for development and testing, not convinced of the safety standards of vaccine, afraid of long-term effects, harmful substance in the vaccine, vaccine causing COVID-19, vaccine will not help, it is not effective, not safe with lower efficacy, I want to build my immunity/I prefer other ways of protection, do not trust system/ something that nobody knows about, vaccine not reliable, doubts about the vaccine due to short time for development, do not believe COVID-19 is a threat, COVID-19 is overrated, no vaccine is needed, It is biological weapon, I am not a guinea pig, I would not like to be like who first took it, do not have enough information about vaccine, political game, the vaccine is a money-making venture.

Outcome variable measurement

The measurement of awareness and attitude was adopted from previous researches [19, 20, 23]. Six yes/no items were included as awareness assessment tools. The correct response was recorded as 1 and 0 for incorrect. The maximum score was 6, and the minimum score was 0. The Awareness was categorized as good or poor. Participants scoring mean or more were categorized as they have good awareness and vice versa.

The attitude section contains eight (8) yes/no items. The correct answer was recorded as 1, and 0 for the incorrect. The maximum score was 8, and the minimum was 0. In addition, the attitude was categorized as a positive and negative attitude similarly to awareness classification.

Data processing and analysis

The data were entered and cleaned using Epi Info 3.1 software and exported to SPSS version 26 for further analysis. Descriptive statistics were used for describing and summarizing the data and chi-square was used to pin out the association of the dependent variable with the independent variables. A multivariable logistic regression model was performed to determine factors associated with the awareness and attitude of participants towards the COVID-19 vaccine. A variable with a p value of less than 0.25 in binary logistic regression was eligible for multivariable logistic regression. p value < 0.05 was used to declare the significant association.

Ethical considerations

A permission letter was obtained from the School of Pharmacy, Jimma University. The work was done as the duty of workers to advise students. Verbal consent was obtained from the participants after the purpose and methods of the study had been explained in detail. All of their responses were kept confidential and anonymous.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

The response rate of the study was 96.03% (387/403). More than half, 252 (65.1%) of the participants were males, and the age (mean ± SD) was 21.97 ± 1.67. Around 39% of the participants were followers of the Orthodox religion. 108 (27.9%) of the participants were medicine students, and 41.1% were 2nd year students. The majority, 72.4% of them comes from urban parts of the country (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 21.97 ± 1.63 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 252 (65.1) | |

| Female | 135 (34.9) | |

| Religion | ||

| Muslims | 81 (20.9) | |

| Orthodox | 151 (39.0) | |

| Protestant | 132 (34.1) | |

| Others | 23 (5.9) | |

| Department | ||

| Medicine | 108 (27.9) | |

| Medical laboratory | 81 (20.9) | |

| Pharmacy | 70 (18.1) | |

| Health officer | 39 (10.1) | |

| Nursing | 31 (8.0) | |

| Anesthesia | 29 (7.5) | |

| Environmental health | 20 (5.2) | |

| Midwifery | 9 (2.3) | |

| Year of study | ||

| 2nd | 159 (41.1) | |

| 3rd | 89 (23.0) | |

| 4th | 102 (26.4) | |

| 5th | 26 (6.7) | |

| 6th | 11 (2.8) | |

| Residency | ||

| Urban | 280 (72.4) | |

| Rural | 107 (27.6) | |

Awareness of students about COVID-19 vaccine

The awareness score (mean ± SD) of the participants was 3.34 ± 1.30. One hundred and fifty-nine, 159 (41.1%) of participants had a good awareness of COVID-19 vaccines. Chi-square performed indicated the association of year of study with awareness towards the COVID-19 vaccine (Table 2).

Table 2.

COVID-19 vaccine awareness among Jimma University Institute of Health students

| Variables | Awareness status | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Good | Poor | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 98 | 154 | 0.230 |

| Female | 61 | 74 | |

| Department | |||

| Medicine | 43 | 65 | 0.481 |

| Medical laboratory | 30 | 51 | |

| Pharmacy | 33 | 37 | |

| Health officer | 16 | 23 | |

| Nursing | 13 | 18 | |

| Anesthesia | 13 | 16 | |

| Environmental health | 5 | 15 | |

| Midwifery | 6 | 13 | |

| Year of study | |||

| 2nd | 55 | 104 | 0.002 |

| 3rd | 28 | 61 | |

| 4th | 57 | 45 | |

| 5th | 14 | 12 | |

| 6th | 5 | 6 | |

| Place of residency | |||

| Urban | 120 | 160 | 0.252 |

| Rural | 39 | 68 | |

| Religion | |||

| Muslims | 36 | 45 | 0.447 |

| Orthodox | 67 | 84 | |

| Protestant | 48 | 84 | |

| Others | 8 | 15 | |

Attitude of students towards COVID-19 vaccine

The attitude score (mean ± SD) of the participants was 4.02 ± 2.47. Two hundred and twenty-four, 224 (57.9%) of the participants have a positive attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccines (Table 3).

Table 3.

Attitude of participants towards the COVID-19 vaccine

| Variables | Attitude status | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 147 | 105 | 0.806 |

| Female | 77 | 58 | |

| Department | |||

| Medicine | 63 | 45 | |

| Medical laboratory | 54 | 27 | |

| Pharmacy | 32 | 38 | |

| Health officer | 20 | 19 | 0.196 |

| Nursing | 18 | 13 | |

| Anesthesia | 19 | 10 | |

| Environmental health | 11 | 9 | |

| Midwifery | 7 | 2 | |

| Year of study | |||

| 2nd | 83 | 76 | |

| 3rd | 51 | 38 | 0.157 |

| 4th | 68 | 34 | |

| 5th | 14 | 12 | |

| 6th | 8 | 3 | |

| Place of residency | |||

| Urban | 161 | 119 | 0.806 |

| Rural | 63 | 44 | |

| Religion | |||

| Muslims | 51 | 30 | |

| Orthodox | 86 | 65 | 0.60 |

| Protestant | 76 | 56 | |

| Others | 11 | 12 | |

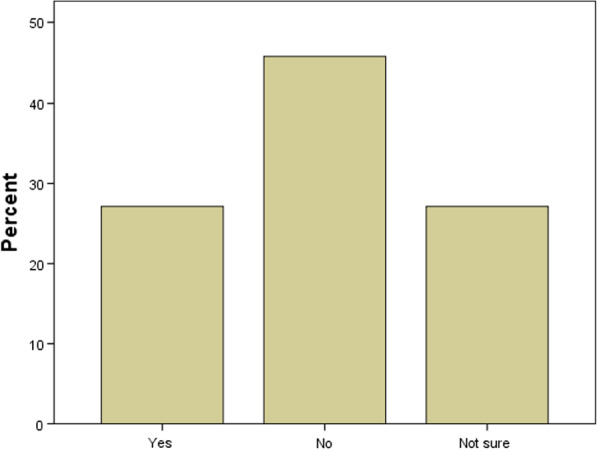

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among participants

Only 27.1% of participants have expressed their willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine, and 45.7% of students were unwilling to have the COVID-19 vaccine (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 Vaccine acceptance among participants

Reasons for refusing COVID-19 vaccine

The participants were listed different factors for refusing to take the COVID-19 vaccine. From these: afraid of long-term effects, not convinced of the safety standards of vaccine, do not have enough information about the vaccine and too short time for development were some of them (Table 3).

Factors associated with awareness and attitude of students towards the COVID-19 vaccine

No significant difference was observed among Jimma University Institute of Health students regarding their awareness of COVID-19 vaccines. However, there is a relationship between the age of students and attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccines (95% CI 1.03, 1.35) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with knowledge and attitude of participants towards COVID-19 vaccine

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Awareness | AOR (95% CI) | Attitude COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR (95% CI) | p-value | COR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1.05 (0.69, 1.61) | 0.806 | ||

| Female | 1.30 (0.85, 1.98) | 0.231 | 1.39 (0.90, 2.14) | 1 | ||

| Age | 1.11 (0.98, 1.26) | 0.099 | 1.10 (0.96, 1.27) | 1.20 (1.05, 1.37) | 0.007 | 1.18 (1.03, 1.35)* |

| Department | ||||||

| Health sciencesa | 1 | 1 | ||||

| othersb | 0.93 (0.59, 1.46) | 0.752 | 1.03 (0.65, 1.61) | 0.911 | ||

| Year of study | ||||||

| 1–4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| > 4 | 1.58 (0.80, 3.12) | 0.185 | 1.35 (0.64, 2.83) | 1.08 (0.54, 2.14) | 0.838 | |

| Religion | ||||||

| Christians | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Muslims | 1.19 (0.73, 1.95) | 0.49 | 1.31 (0.79, 2.16) | 0.298 | ||

| Place of residency | ||||||

| Urban | 1.31 (0.83, 2.07) | 0.252 | 1 | |||

| Rural | 1 | 1.06 (0.67, 1.66) | 0.806 | |||

| Awareness status | ||||||

| Good | 2.47 (1.61, 3.79) | < 0.001 | 2.39 (1.55, 3.68)* | |||

| Poor | 1 | 1 | ||||

aStudents of Pharmacy, medical laboratory, nursing, anesthesia, environmental health bDentistry, health officer and medicine students. *significance

Discussion

The availability and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccine are vital to control the pandemic. Policymakers and health authorities must ensure acceptance and trust from the community and healthcare workers, because hesitation and delay may result in vaccination refusal. These could lead to devastating effects on public health and hinder the healthcare system’s ability to accommodate the challenges of the pandemic. Community awareness, attitude and acceptance affect public health and the healthcare system to withstand the challenges of the pandemic [22]. Vaccination is an effective way of controlling infectious diseases. However, the success is challenged by individuals and groups who choose to delay or refuse vaccines. Vaccine hesitancy is one cause for decreasing vaccine coverage and increasing the risk of vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks and epidemics [23].

According to the present study, only less than half of participants had a good awareness of the COVID-19 vaccine. The result was comparable with the study conducted on the web in Ethiopia reporting 40.8% of the participants had a good awareness of the COVID-19 vaccine [25]. However, the finding was lower than the study conducted in Ethiopia on adult populations in which 74% of participants have good knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine [26]. The discrepancy might be due to differences in the study population and sample size. However, statistical analysis showed no association of sociodemographic characteristics with their respective awareness of the COVID-19 vaccine.

More than half, 58% of participants had a positive attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccine. The finding was comparable with the studies conducted in Ethiopia on health professionals in which around 42.3% of the participants had a positive attitude [24]. However, the finding was higher than the e-based survey conducted in Ethiopia in which only 24.2% of the participants had a positive attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccine [25]. The discrepancy might be due to the method of data collection in which the previous study used web-based data collection and differences in the study unit. Statistically, age and having good awareness about the COVID-19 vaccine was associated with attitude, and the study conducted in Ethiopia also reported the association of age with the attitude towards the COVID-19 vaccine [24, 26].

The number of participants who expressed their willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine was small. Only 27% of the participants were willing to take the vaccine. This figure was smaller than an institutional study conducted in Ethiopia, which reported that 61% of the participants had expressed their willingness to take vaccines whenever available [27]. The other study conducted in Ethiopia reported around 62.6% of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance [26]. The discrepancy might be due to sample size differences and differences in study participants.

The reasons for refusing the COVID-19 vaccine were: not convinced of the safety standards of the vaccine, Afraid of long-term effects, do not have enough information about the vaccine, too short time for development and Doubts about the vaccine due to short time of development were the most reported reasons (Tables 5).

Table 5.

Participants reasons for refusing the COVID-19 vaccine

| Reasons for refusing to take COVID-19 vaccine | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| To short time for development | 131 (33.9) |

| Not convinced of the safety standards of vaccine | 150 (38.8) |

| Afraid of long-term effects | 191 (49.1) |

| Harmful substance in vaccine | 104 (26.9) |

| Vaccine causing COVID-19 | 47 (12.1) |

| Vaccine will not help, it is not effective | 46 (11.9) |

| Not safe with lower efficacy | 57 (14.7) |

| I want to build my own immunity/I prefer other ways of protection | 89 (23) |

| Do not trust system/something that nobody knows about | 109 (28.2) |

| Vaccine not reliable | 71 (18.3) |

| Doubts about the vaccine, due to short time for development | 123 (31.8) |

| Do not believe COVID-19 is a threat | 35 (9.0) |

| COVID-19 is overrated, no vaccine is needed | 26 (6.7) |

| It is Biological weapon | 68 (16.8) |

| I am not a guinea pig | 47 (12.1) |

| I would not like to be like who first took it | 38 (9.8) |

| Do not have enough information about vaccine | 144 (37.2) |

| Political game | 118 (30.5) |

| Vaccine is a money-making venture | 49 (12.7 |

Conclusions

According to the present study, the majority of participants had a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine. However, only less than half of the participants had a good awareness of the vaccine. In addition, the acceptability of the vaccine is low. Afraid of long term effects, not being convinced of the safety profile, lack of information about the vaccine, and the time used for the development were the common reasons for refusing the vaccine. Therefore, all stakeholders are advised to increase awareness, positive attitude, and acceptance of the vaccine.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the data collectors and students participating in the study. The authors would also like to thank the Jimma University printing service office.

Authors’ contributions

FA is contributed to the conception, design and acquisition of data. BU contributed to the conception, analysis, preparation and revision of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data set used for analysis is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors disclose no conflict of interest. Both authors read and approve the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report, 82. 2020.

- 2.Imai N, Dorigatti I, Cori A, Donnelly C, Riley S, Ferguson N. Report 2: estimating the potential total number of novel Coronavirus cases in Wuhan City, China; 2020.

- 3.Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assessment RR. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the EU/EEA and the UK–ninth update. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm; 2020.

- 6.COVID C. Global Cases by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at 323 Johns Hopkins University (JHU). JHU COVID-19 Resource Center. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center; 2020.

- 7.Lipscy PY. COVID-19 and the politics of crisis. Int Organ. 2020;74(S1):E98–127. doi: 10.1017/S0020818320000375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodds K, Broto VC, Detterbeck K, Jones M, Mamadouh V, Ramutsindela M, Varsanyi M, Wachsmuth D, Woon CY. The COVID-19 pandemic: territorial, political and governance dimensions of the crisis. Territory Polit Governance. 2020;8(3):289–298. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2020.1771022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glanville D. COVID-19 vaccines: development, evaluation, approval and monitoring. European Medicines Agency; 2020.

- 10.Graffigna G, Palamenghi L, Boccia S, Barello S. Relationship between citizens’ health engagement and intention to take the covid-19 vaccine in italy: a mediation analysis. Vaccines. 2020;8(4):576. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8040576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a WebBased National Survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1657–1663. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S276771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.French J, Deshpande S, Evans W, Obregon R. Key guidelines in developing a pre-emptive COVID-19 vaccination uptake promotion strategy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5893. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coustasse A, Kimble C, Maxik K. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: a challenge the United States must overcome. J Ambul Care Manage. 2021;44(1):71. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoch-Spana M, Brunson EK, Long R, Ruth A, Ravi SJ, Trotochaud M, et al. The public’s role in COVID-19 vaccination: human-centered recommendations to enhance pandemic vaccine awareness, access, and acceptance in the United States. Vaccine. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neergaard L, Fingerhut H. AP-NORC poll: half of Americans would get a COVID-19 vaccine: Associated Press; May 28, 2020.

- 17.Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a survey of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:964. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100495. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taye BT, Amogne FK, Demisse TL, Zerihun MS, Kitaw TM, Tiguh AE, Mihret MS, Kebede AA. Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine acceptance and perceived barriers among university students in northeast Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Clinical Epidemiol Global Health. 2021;12:100848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Wang J, Jing R, Lai X, Zhang H, Lyu Y, Knoll MD, Fang H. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):482. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Mohaithef M, Padhi BK. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: a web-based national survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13(1657):1663. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S276771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elhadi M, Alsoufi A, Alhadi A, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:955. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10987-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zewude B, Habtegiorgis T. Willingness to take COVID-19 vaccine among people most at risk of exposure in southern Ethiopia. Pragmat Obs Res. 2021;12(37):47. doi: 10.2147/POR.S313991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alle YF, Oumer KE. Attitude and associated factors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among health professionals in Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, North Central Ethiopia; 2021: cross-sectional study. VirusDis. 2021;32:272–278. doi: 10.1007/s13337-021-00708-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mesesle M. Awareness and attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination and associated factors in Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:2193–2199. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S316461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abebe H, Shitu S, Mose A. Understanding of COVID-19 vaccine knowledge, attitude, acceptance, and determinates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adult population in Ethiopia. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:2015–2025. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S312116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mose A. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccine and its determinant factors among lactating mothers in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:4249. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S336486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data set used for analysis is available from the corresponding author upon request.